Advocacy in the Face of Adversity: Influence in the Relationship Between Racial Microaggressions and Social Justice Advocacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Discrimination and Coping

1.2. Coping with Discrimination and Social Justice Advocacy

1.3. Present Study

- Experiencing racial microaggressions will be significantly positively associated with the utilization of task-focused coping.

- Experiencing racial microaggressions will be significantly positively associated with engagement in social justice advocacy.

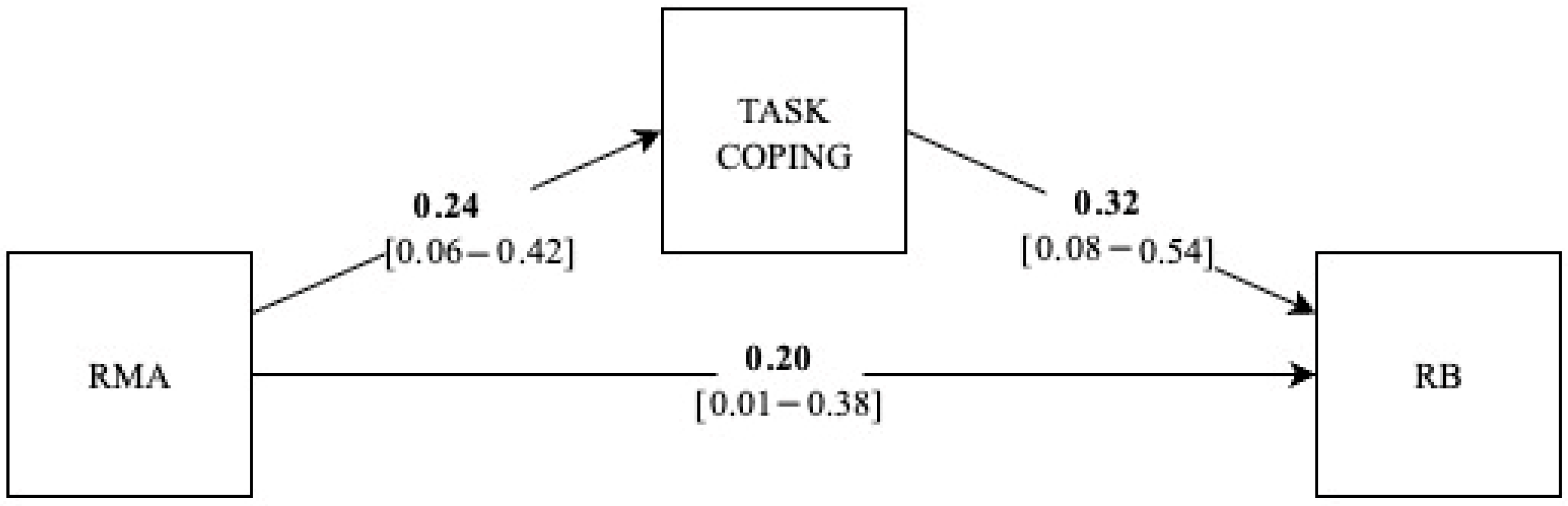

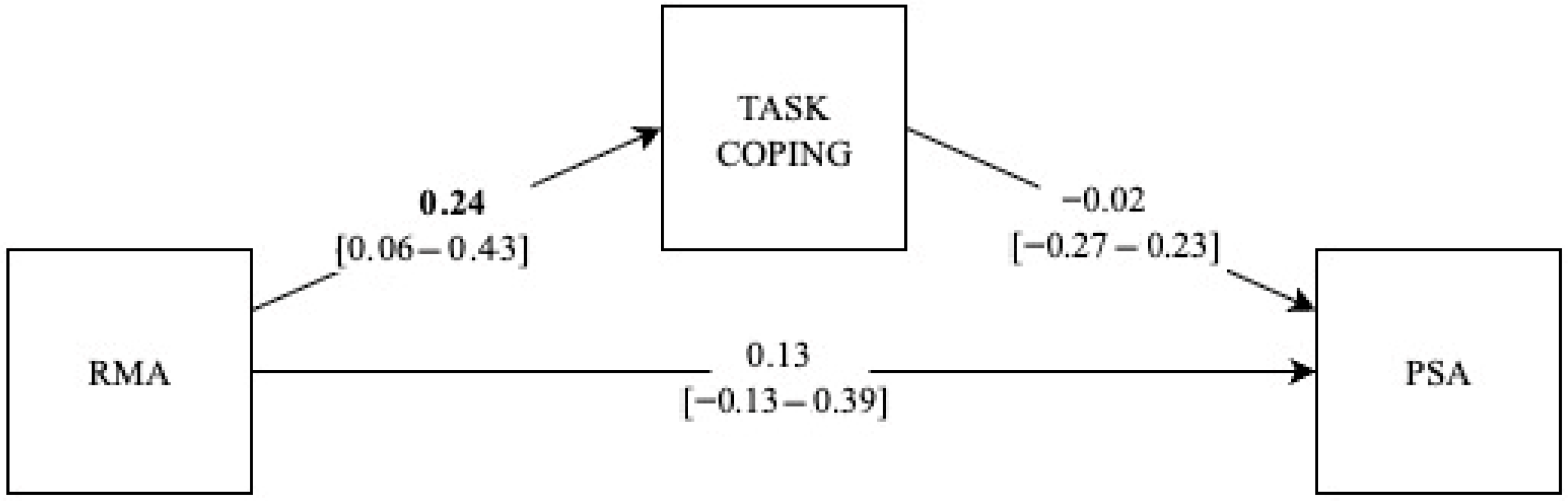

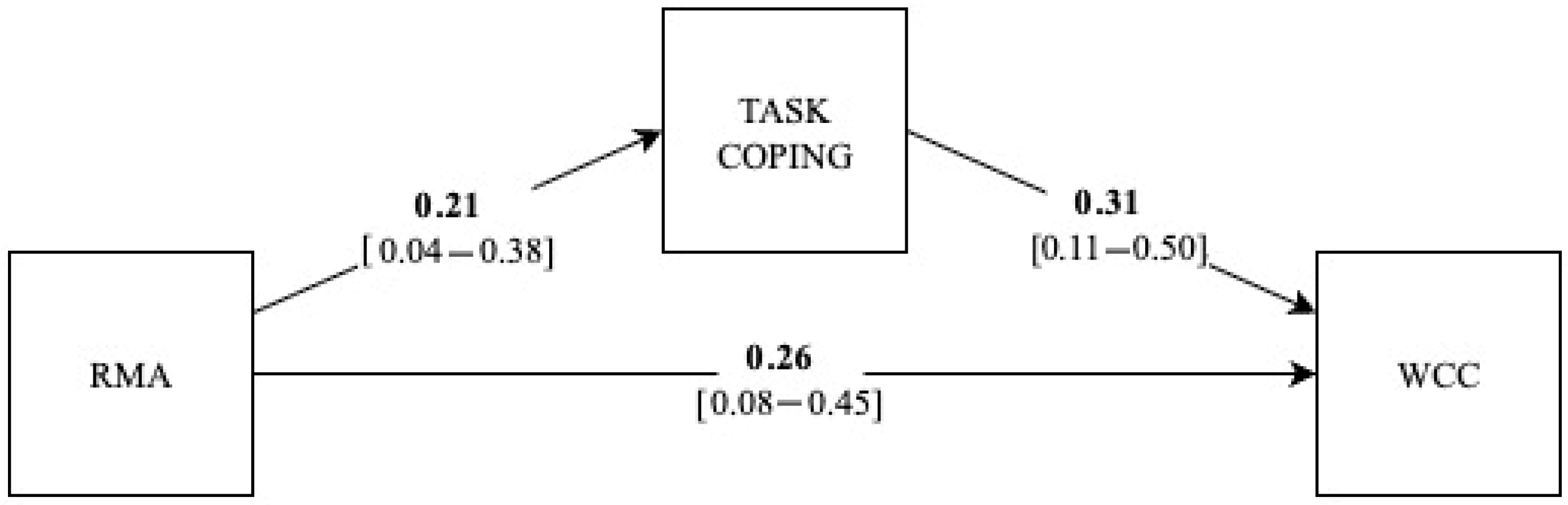

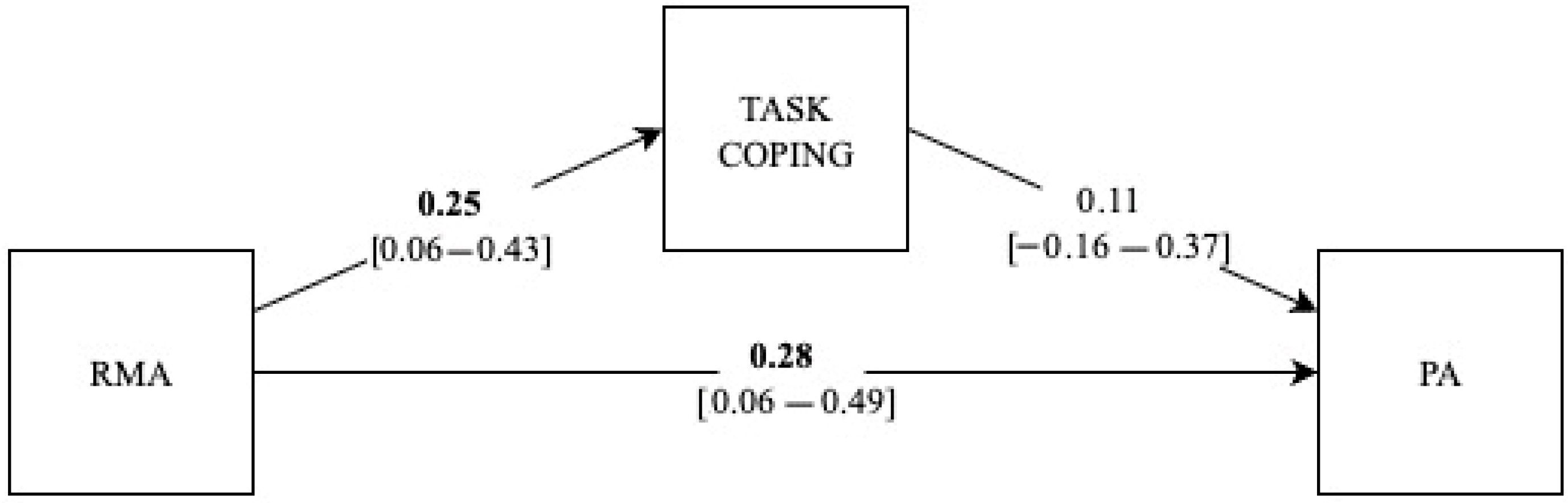

- Task-focused coping will significantly mediate the relationship between racial microaggressions and engagement with social justice advocacy, such that task-focused coping will significantly positively relate to engagement in social justice advocacy, as well as display significant indirect effect in the relationship between racial microaggressions and four different aspects of social justice advocacy (relationship building, political and social advocacy, willingness to confront and challenge, political awareness).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedures and Planned Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Primary Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PWI | Primarily White Institution |

| SJA | Social Justice Advocacy |

| RMAS | Racial Microaggressions Scale |

| SIAS-2 SF | Social Issues Awareness Scale-2 Short Form |

| CISS-SF | Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations-Short Form |

References

- Apugo, Danielle. L. 2017. “We All We Got”: Considering Peer Relationships as Multi-Purpose Sustainability Outlets Among Millennial Black Women Graduate Students Attending Majority White Urban Universities. The Urban Review 49: 347–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, Maria Isabel, and Dana Chalupa Young. 2022. Racial Microaggressions and Coping Mechanisms Among Latina/o College Students. Sociological Forum 37: 200–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Myrtle. P., Daphne Berry, Joy Leopold, and Stella Nkomo. 2021. Making Black Lives Matter in Academia: A Black Feminist Call for Collective Action Against Anti-Blackness in the Academy. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zur, Hasida. 2005. Coping, Distress, and Life Events in a Community Sample. International Journal of Stress Management 12: 188–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, Arthur W., Laura V. Lovato, Bryan N. Thyken, and Natasha Denny. 2012. The Relationship of Microaggressions with Alcohol Use and Anxiety Among Ethnic Minority College Students in a Historically White Institution. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 18: 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandow, Crystal L., and Margaret Swarbrick. 2022. Improving Black Mental Health: A Collective Call to Action. Psychiatric Services 73: 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burt, Brian. A., Alade McKen, Jordan Burkhart, Jennifer Hormell, and Alexander Knight. 2019. Black Men in Engineering Graduate Education: Experiencing Racial Microaggressions within the Advisor-Advisee Relationship. Journal of Negro Education 88: 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Wanda. M., Angelia M. Paschal, Jessica Jaiswal, James D. Leeper, and David A. Birch. 2024. Gendered Racial Microaggressions and Black College Women: A Cross-Sectional Study of Depression and Psychological Distress. Journal of American College Health 72: 2811–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, David. S., Lauren B. McInroy, Shelley L. Craig, Sarah Slates, and Shanna K. Kattari. 2020. Naming and Addressing Homophobic and Transphobic Microaggressions in Social Work Classrooms. Journal of Social Work Education 56: 484–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, German A., Eric Garcia, and Kelsey Autin. 2025. Social Justice Activism and Critical Agency Among Undocumented Students: Coping Mediators Between Discrimination and Depression. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 18: 123–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Olivia D., Kaitlin P. Ward, and Shawna J. Lee. 2024. Examining Coping Strategies and Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence for the Protective Role of Problem-Focused Coping. Health & Social Work 49: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohan, Sharon. L., Kerry L. Jang, and Murray B. Stein. 2006. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of a Short Form of the Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations. Journal of Clinical Psychology 62: 273–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, David. 2001. Advocacy: Its Many Faces and a Common Understanding. In Advocacy for Social Justice: A Global Action and Reflection Guide. Edited by D. Cohen, R. De la Vega and G. Watson. Boulder: Kumarian Press, pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Colgan, Courtney. A., Pratyusha Tummala-Narra, Tanvi N. Shah, Tooba Fatima, Sahar M. Sabet, and Gayatri M. Khosla. 2024. A Qualitative Exploration of Muslim American College Students’ Experiences of Discrimination and Coping. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 95: 535–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, Madonna G., Sally M. Hage, Mai M. Kindaichi, and Rhonda M. Bryant. 2007. Social Justice and Multicultural Issues: Implications for the Practice and Training of Counselors and Counseling Psychologists. Journal of Counseling & Development 85: 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endler, Norman S., and James D. A. Parker. 1994. Assessment of Multidimensional Coping: Task, Emotion, and Avoidance Strategies. Psychological Assessment 6: 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, Reya, Emma Wedell, Luke Herchenroeder, Cheryl L. Dickter, Matthew R. Pearson, and Adrian J. Bravo. 2021. Microaggressions and Psychological Health Among College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model of Rumination and Social Structure Beliefs. Journal of Racial Ethnic Health Disparities 8: 245–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, Susan. 2010. Stress, Coping, and Hope. Psycho-Oncology 19: 901–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, Susan, and Richard S. Lazarus. 1988. Coping as a Mediator of Emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 466–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, Myriam, Timothy Grigsby, Christopher Rogers, Jennifer Unger, Stephanie Alvarado, Bethany Rainisch, and Eunice Areba. 2022. Perceived Discrimination, Coping Styles, and Internalizing Symptoms Among a Community Sample of Hispanic and Somali Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 70: 488–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Louis, Claudia, Victor B. Sáenz, and Tonia Guida. 2023. How Community College Staff Inflict Pervasive Microaggressions: The Experiences of Latino Men attending Urban Community Colleges in Texas. Urban Education 58: 2378–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, Aisha N., Noelle M. Hurd, and Sadia B. Hussain. 2019. “I Didn’t Come to School for This”: A Qualitative Examination of Experiences with Race-Related Stressors and Coping Responses Among Black Students Attending a Predominantly White Institution. Journal of Adolescent Research 34: 115–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2022. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis, Third Edition: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Introduction-to-Mediation-Moderation-and-Conditional-Process-Analysis-Third-Edition-A-Regression-Based-Approach/Hayes/p/book/9781462549030 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Huynh, Kiet D., and Debbiesiu L. Lee. 2023. Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies as Mediators of the Discrimination–Mental Health Association Among LGB POC. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 10: 413–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanba, Sathya Baanu, Johanna E. Nilsson, and LaVerne Berkel. 2024. Discrimination, Traumatic Stress, and Coping Among Muslim International Students. Journal of College Student Mental Health, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelsma, Elizabeth, Shanting Chen, and Fatima Varner. 2022. Working Harder than Others to Prove Yourself: High-Effort Coping as a Buffer between Teacher-Perpetrated Racial Discrimination and Mental Health among Black American Adolescents. Journal of Youth & Adolescence 51: 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, Ibrahim, Siddrah Irfan, Hanaa Shuwiekh, and Mireille Bujold-Bugeaud. 2025. Coping with Continuous Traumatic Stressors (Gender Discrimination, Intersected Discrimination and COVID-19): The Will to Exist, Live, Fight, Resist and Survive. Current Psychology 44: 10713–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Ben C. H. 2011. Culture’s Consequences on Coping: Theories, Evidences, and Dimensionalities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42: 1084–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard. S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Eun-Kyoung “Othelia”, and Callan Barrett. 2007. Integrating Spirituality, Faith, and Social Justice in Social Work Practice and Education: A Pilot Study. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work 26: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnemeyer, Rachel M., Johanna E. Nilsson, Jacob M. Marszalek, and Marina Khan. 2018. Social Justice Advocacy Among Doctoral Students in Professional Psychology Programs. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 31: 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, Jordan A. 2006. The COPE Inventory: Dimensionality and Relationships with Approach- and Avoidance-Motives and Positive and Negative Traits. Personality & Individual Differences 41: 273–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Roderick J. A. 1988. A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. Journal of the American Statistical Association 83: 1198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, Linh P., and Arpana G. Inman. 2022. Social Justice Advocacy: The Role of Race and Gender Prejudice, Injustice, and Diversity Experiences. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 35: 652–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszalek, Jacob M., Carolyn Barber, and Johanna E. Nilsson. 2017. Development of the Social Issues Advocacy Scale-2 (SIAS-2). Social Justice Research 2: 117–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, Elana R., Katharine H. Zeiders, Antoinette M. Landor, and Selena Carbajal. 2022. Coping with Ethnic–racial Discrimination: Short-Term Longitudinal Relations Among Black and Latinx College Students. Journal of Research on Adolescence 32: 1530–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midgette, Allegra J., and Kelly Lynn Mulvey. 2021. Unpacking Young Adults’ Experiences of Race and Gender-Based Microaggressions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 38: 1350–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, Anahvia Taiyib, and Jioni A. Lewis. 2019. Gendered Racial Microaggressions and Traumatic Stress Symptoms Among Black Women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 43: 201–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, Calia A., Edwin N. Aroke, Janelle E. Letzen, Claudia M. Campbell, Anna M. Hood, Mary R. Janevic, Vani A. Mathur, Ericka N. Merriwether, Burel R. Goodin, Staja Q. Booker, and et al. 2022. Confronting Racism in Pain Research: A Call to Action. The Journal of Pain 23: 878–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, Della V., Helen A. Neville, Nayeli Y. Chavez-Dueñas, Hector Y. Adames, Jioni A. Lewis, and Bryana H. French. 2020. Radical Hope in Revolting Times: Proposing a Culturally Relevant Psychological Framework. Social & Personality Psychology Compass 14: e12512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neukrug, Hannah, G. Perusi Benson, Graham Buhrman, and Vanessa V. Volpe. 2022. Affect Reactivity and Lifetime Racial Discrimination Among Black College Students: The Role of Coping. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 92: 516–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, Johanna. E., Jacob M. Marszalek, Alissa Kim, Anum Khalid, Bethany Bierman, and Sophie Chabot. 2024. Development and Validation of Social Issues Advocacy Scale 2-Short Form. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddiri, Uchechi, Oriaku A. Kas-Osoka, and Stephanie L. White. 2023. Learning to Action: Finding Your Anti-Racism and Equity Lens. Pediatrics 152: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Anthony D., Anthony L. Burrow, Thomas E. Fuller-Rowell, Nicole M. Ja, and Derald Wing Sue. 2013. Racial Microaggressions and Daily Well-Being Among Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology 60: 188–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, Robert T., Dina C. Maramba, and Sharon L. Holmes. 2011. A Contemporary Examination of Factors Promoting the Academic Success of Minority Students at a Predominantly White University. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 13: 329–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelman, Mirella Flores, and Laurel B. Watson. 2023. The Relations Among Microaggressions, Collective Action, and Psychological Outcomes Among Sexual Minority Latinx People. Journal of Latinx Psychology 11: 240–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2024. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Computer Software]. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Riposa, Gerry. 2003. Urban Universities: Meeting the Needs of Students. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 585: 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, Naysha N., Tamara Nelson, and Esteban V. Cardemil. 2018. Lift Every Voice: Exploring the Stressors and Coping Mechanisms of Black College Women Attending Predominantly White Institutions. Journal of Black Psychology 44: 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Sanga, Simin Michelle Chen, and Hyejin Kim. 2025. Coping with Anti-Asian Sentiment: A Qualitative Study of Appraisals and Coping Strategies Against Discrimination. Asian American Journal of Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Justine, Faith Onyambu, Vernice Barrimond, and Christin Fort. 2025. Resistance and Resilience: The Black Church’s Response to Community Violence and Racism. Translational Issues in Psychological Science 11: 236–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, Derald Wing, Annie I. Lin, Gina C. Torino, Christina M. Capodilupo, and David P. Rivera. 2009. Racial Microaggressions and Difficult Dialogues on Race in the Classroom. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 15: 183–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, Derald Wing, Christina M. Capodilupo, Gina C. Torino, Jennifer M. Bucceri, Aisha M. B. Holder, Kevin L. Nadal, and Marta Esquilin. 2007. Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice. American Psychologist 62: 271–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukumaran, Niyatee, Johanna E. Nilsson, and Alissa Kim. 2025. Racial Microaggressions in Cross-Racial Supervision: Counseling and Multicultural Self-Efficacy, Supervisory Working Alliance, and Supervisor Multicultural Competency. The Clinical Supervisor, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Harding, Susan R., Alejandro L. Andrade, Jr., and Crist E. Romero Diaz. 2012. The Racial Microaggressions Scale (RMAS): A New Scale to Measure Experiences of Racial Microaggressions in People of Color. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 18: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsey, Sean O., Mark A. Bolden, Yzette Lanier, and Otis Williams, III. 2007. Examining the Role of Culture-Specific Coping as a Predictor of Resilient Outcomes in African Americans from High-Risk Urban Communities. Journal of Black Psychology 33: 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, Sylvanna M., Standly J. Huey, Jr., and Jeanne Miranda. 2020. A Critical Review of Current Evidence on Multiple Types of Discrimination and Mental Health. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 90: 374–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, Earlise C., Jacqueline C. Wiltshire, Michelle A. Detry, and Roger L. Brown. 2013. African American Men and Women’s Attitude Toward Mental Illness, Perceptions of Stigma, and Preferred Coping Behaviors. Nursing Research 62: 185–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, David R., and Selina A. Mohammed. 2009. Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32: 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, David R., Jourdyn A. Lawrence, and Brigette A. Davis. 2019. Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research. Annual Review of Public Health 40: 105–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Rose, and Terry Jones. 2018. Students’ Experiences of Microaggressions in an Urban MSW Program. Journal of Social Work Education 54: 679–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | |||||

| 0.28 ** | – | ||||

| 0.29 ** | 0.37 ** | – | |||

| 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.56 ** | – | ||

| 0.44 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.46 ** | – | |

| 0.32 ** | 0.22 * | 0.61 ** | 0.65 ** | 0.53 ** | – |

| M | 70.99 | 23.72 | 16.00 | 13.30 | 18.16 | 11.35 |

| SD | 22.03 | 4.51 | 4.50 | 5.08 | 4.23 | 3.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ternes, M.S.; Nilsson, J.E.; Khalid, A.; Siems, M.B. Advocacy in the Face of Adversity: Influence in the Relationship Between Racial Microaggressions and Social Justice Advocacy. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090564

Ternes MS, Nilsson JE, Khalid A, Siems MB. Advocacy in the Face of Adversity: Influence in the Relationship Between Racial Microaggressions and Social Justice Advocacy. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):564. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090564

Chicago/Turabian StyleTernes, Michael S., Johanna E. Nilsson, Anum Khalid, and Melànie B. Siems. 2025. "Advocacy in the Face of Adversity: Influence in the Relationship Between Racial Microaggressions and Social Justice Advocacy" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090564

APA StyleTernes, M. S., Nilsson, J. E., Khalid, A., & Siems, M. B. (2025). Advocacy in the Face of Adversity: Influence in the Relationship Between Racial Microaggressions and Social Justice Advocacy. Social Sciences, 14(9), 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090564