Abstract

Background: Individuals who are victimized and exploited by the heinous crimes of human trafficking (HT) access healthcare during their exploitation, yet gaps in education on HT content exist in prelicensure nursing programs. This study explored the impact of an HT simulation on nursing students’ preparedness in the identification of victims as well as their perceptions of the impact of this educational intervention on future practices. Methods: A quasi-experimental design with a qualitative component was used. A convenience sample of 120 nursing students were recruited. The participants completed a pretest survey, viewed a preparatory education video, and participated in the simulation followed by a debriefing, a 20-min video, and posttest survey. Results: More than 3/4 of the participants reported no previous exposure to this content. A paired sample t-test showed efficacy (p < 0.001) with a Cohen’s d > 0.8, illustrating an increase in knowledge gained. The qualitative data yielded four themes: eye-opening, educational and informative, increased awareness, and preparedness. Conclusions: Nurses are well-positioned to identify, treat, and respond to victims of HT. The findings underscore the critical need to incorporate comprehensive HT content into prelicensure nursing curricula. Through integration of an HT simulation, future nurses can be better prepared to address this pervasive issue, ultimately improving victim outcomes and ensuring progress towards UN Sustainable Development Goal 5 of Gender Equality and Goal 16 of Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions. In addition, addressing this topic in prelicensure nursing education ensures that future nurses are not only clinically competent but also morally and emotionally prepared to handle the complexities of HT in their professional roles.

1. Introduction

Human trafficking (HT) is a humanitarian crisis affecting millions of people worldwide (Bono-Neri 2024). It is an exploitation-based crime against an individual for commercial sex, labor, or services through force, fraud, or coercion (Trafficking Victims Protection Act 2000). Many trafficked individuals access healthcare during their exploitation (Jones Day 2022), exhibiting acute physical injuries, psychological concerns, and chronic health issues (Ernewein et al. 2023). Unfortunately, victims frequently go unrecognized by healthcare professionals (HCPs) due to an existing gap in HT education (Bono-Neri 2024; Bono-Neri and Toney-Butler 2023; Ernewein et al. 2023; Marcinkowski et al. 2022).

2. Background

The intersection of HT with healthcare is substantial, as retrospective studies show that approximately 70–90% of these victimized individuals are accessing the healthcare sector for diverse acute and chronic concerns (Bono-Neri and Toney-Butler 2023; Chisolm-Straker et al. 2016; Jones Day 2022; Lederer and Wetzel 2014). With this significant intersection occurring, the gap in HT education in nationwide prelicensure RN programs is concerning. One study was conducted which showed that 91.4% of students nationwide reported minimal to no HT content being taught in their academic preparation (Bono-Neri and Toney-Butler 2023). Nursing students are graduating ill-prepared to recognize and respond to these victims in healthcare settings. Nurses play a critical role in identifying, treating, responding to, and advocating for victims of HT (Bono-Neri and Toney-Butler 2023). As this population too often goes unrecognized and therefore untreated by HCPs, undergraduate nursing programs are uniquely positioned to close this gap by properly educating students on HT and anti-trafficking measures which can yield improved identification and appropriate care for this population.

Within nursing education, simulation is a widely recognized and utilized pedagogical method to prepare students for the transition into real-life clinical practice (Bryant et al. 2020). Simulation is effective in building skills of critical thinking, clinical decision-making, and problem-solving, thereby supporting the development of practice-ready professionals (Kim et al. 2016; Moloney et al. 2022). Simulation-based education is an integral component of nursing programs, complementing and sometimes replacing clinical rotations. The INACSL Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice® (INACSL Standards Committee et al. 2021) provide an evidence-based framework designed to support, guide, and advance the science of simulation. A simulation experience, with proper preparation, can serve as an effective and powerful educational tool (Gates and Youngberg-Campos 2020).

3. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study was to explore the impact of an HT simulation on prelicensure nursing students’ self-reported preparedness in identifying a victim of HT. Additionally, the study sought to explore nursing students’ perceptions of the impact of this educational intervention on future practice.

Theoretical Frameworks

The first theoretical framework that guided this research was Orlando’s Deliberative Nursing Process Theory (1990). According to the theory, it is the nurse’s responsibility to ensure that the client’s needs are met by being cognizant of verbal and nonverbal cues, utilizing observational skills and prior knowledge (Orlando 1990). This theory serves as an effective framework for research and for the education of nursing students on HT. Individuals who are trafficked often do not self-identify as victims nor disclose their victimization (Bono-Neri and Toney-Butler 2023; Toney-Butler et al. 2023). Therefore, it is essential for nurses to rely on both verbal and nonverbal cues to assess the clients’ needs, ensure safety, and provide assistance and support.

The second theoretical framework used was Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory (1984). This theory emphasizes learning through experience, for which simulation-based education is exemplified. Kolb (1984) described a four-stage learning cycle consisting of a concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Relating to the study, all the participants viewed and applied HT content from the preparatory module through the experience of deliberate practice, engaging in the nuances and complexities of performing a physical assessment and utilizing therapeutic communication with a portrayed HT standardized patient. Post-simulation, the students reflected on their experiences, observations, clinical judgment, and how their selected actions affected patient outcomes. Incorporating Experiential Learning Theory into this study provided the additional framework needed.

4. Research Design

4.1. Setting

Using the university’s simulation center, this study was conducted at a four-year, prelicensure baccalaureate RN program situated in the northeast United States which integrates simulation-based education into its curriculum.

4.2. Participants

Two cohorts of second-year nursing students were used (n = 120). The simulation and data collection occurred March–April 2023 (Cohort #1) and March-April 2024 (Cohort #2). After cleaning the data, n = 41 was obtained from Cohort #1 and n = 71 from Cohort #2, yielding a total of n = 112.

5. Methods

The simulation was integrated into the program’s Health Assessment course. It was strategically placed before the students’ first hospital-setting experience. This provided the participants an opportunity to practice history-taking and physical assessment skills as well as to increase their knowledge on the prevalence and signs of HT in the clinical setting.

HSSOBP® (2021) guided the design of the scenario and scripts (INACSL Standards Committee et al. 2021). Scenario content was based on a case study created by Nurses United Against Human Trafficking (2022), which is led by two HT subject matter nursing experts (one of whom is also a survivor). The simulation was developed by two academic nurse educators with formal professional development and expertise in simulation-based education. Due to the sensitive subject matter, the simulation was designed to be a timed unfolding case, using a simulated clinical immersion experience with a standardized patient. With attention to the HSSOBP® (2025) and ASPE Standards of Best Practice (ASPE 2020) guidelines, the script for the patient was written with verbal cues that allowed for consistent standardized dialog. To enhance realism, the standardized patient rehearsed ways to engage or withdraw by using cues, timing, and verbal and non-verbal behaviors. Additionally, a crown tattoo was created and moulage was used to create bruising patterns that covered different areas of the body; both tattoos and bruises are known to be signs of concern or red-flag indicators in victims (Nurses United Against Human Trafficking 2022).

The faculty sent preparatory materials to the students in advance of each scheduled simulation. Students viewed an NUAHT developed 1-h asynchronous education module which provided an HT overview, head-to-toe HT-related assessment, screening questions, and mandatory reporting guidelines when case-applicable. The simulation-based experience started with a prebriefing according to HSSOBP® guidelines (INACSL Standards Committee et al. 2025).

Facilitators trained in simulation pedagogy conducted the post-simulation debriefing, during which students were able to express feelings related to the experience and guided through the process of learning through self-reflection. Students viewed a 15-min NUAHT Targeted Healthcare Response to reinforce their learning. Lastly, debriefing concluded with a discussion after being shown a 5-min video message created by the lived-experience author who addressed feelings of sadness, anger, frustration, and guilt that participants may have encountered throughout and after the simulation.

5.1. Sample Size with Power

G*Power software version 3.1.9.7 was used to conduct a post-hoc power analysis. Calculated at two-tailed significance level of 0.05, an effect size of 0.3, and an n = 112, the power level noted was 0.88.

5.2. Instrument

Data were collected via an anonymous online survey using Qualtrics. The Human Trafficking Simulation Efficacy Evaluation Survey (HTSEES) utilized was developed by the researchers using and modifying the Bono-Neri and Toney-Butler (2023) Student Nurse Human Trafficking Education Assessment Tool (SNHTEAT, α = 0.828) with permission from its developers, who are HT subject matter experts. The pretest version (α = 0.885) had items that reflected a pre-simulation experience. Administered after the simulation experience, the posttest version (α = 0.820) had identical items, but wording was changed to reflect the post-simulation experience.

Comprised of two parts, the pretest HTSEES consisted of nine 5-point Likert-type scale questions on perceived HT awareness and knowledge and two Yes/No questions relating to prior exposure to HT content. The second part consisted of three questions used to collect data on participants’ personal characteristics.

The posttest HTSEES was also comprised of two parts. The first part had the identical nine questions as the pretest, but wording reflected the post-simulation experience. The second part consisted of two qualitative questions with open text fields for participants to provide their own words.

5.3. Data Analysis

SPSS version 29 for statistical data processing was used with inferential results interpreted at a two-tailed significance level of p ≤ 0.05. Descriptive statistical analyses and paired sample t-test analyses were performed on the quantitative data using HTSEES scores and measures. Theme analysis was conducted by the authors on the qualitative data collected from the posttest HTSEES. Inductive coding methodology was used, as coding was derived from the data, assisting in exploration of this simulation experience. Frequency of similar to same responses were counted, from which the various themes emerged. The use of inter-rater agreement was the strategy implemented to ensure reliability.

5.4. Ethical Considerations

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the university where the research was conducted. Prior to the simulation, participants were made aware of the importance of preserving psychological safety (Kolbe et al. 2020) due to the sensitive nature of the content. Participants were encouraged to approach faculty at any time during the simulation experience, if necessary.

Although incorporated into the Health Assessment course, students had the right to refuse participation in this research study. Additionally, assurance was provided that responses would not affect grades and the role of instructors was in no way coercive. All participants provided consent and participated on a voluntary basis, with the ability to withdraw at any time and for any reason. Anonymity was assured in the invitation and maintained, including in all data collected.

6. Results

The data were obtained electronically through Qualtrics using the HTSEES. Any participants with total or partial missing data points were excluded from the analyses. After the data were cleaned and both cohorts were combined into one dataset, the pretest sample yielded an n = 112 and the posttest sample an n = 104. The results are as follows.

6.1. Sample Characteristics

The study participants included a sample of two cohorts of second-year prelicensure baccalaureate RN students enrolled in a Health Assessment course in the Spring semesters of 2023 and 2024. The personal characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographics: Pretest personal characteristics.

6.2. Pretest Results

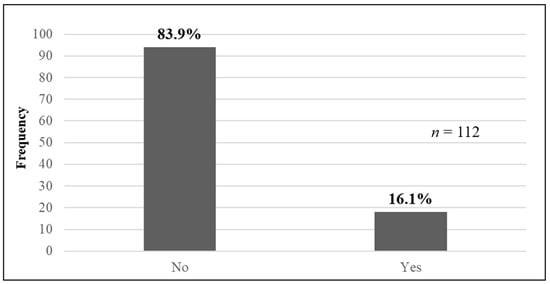

Prior Exposure to HT Content. The participants were asked two questions surrounding their prior exposure to HT content. Using an n = 112 with Yes = 1 and No = 0, the question, “Have you ever been taught Human Trafficking content in your undergraduate nursing program prior to this experience?” resulted in a mean score of 0.1607, SD = 0.3689, with 83.9% (n = 94) responding No and 16.1% (n = 18) responding Yes (Figure 1). The results for, “Have you ever had formal training on Human Trafficking outside of your undergraduate nursing program?” showed a mean score of 0.1071, SD = 0.3107, with 89.3% (n = 100) responding No and 10.7% (n = 12) responding Yes.

Figure 1.

Prior exposure to human trafficking content in RN curriculum.

Perceived HT Awareness and Knowledge. The participants were asked nine questions pertaining to their perceived HT awareness and knowledge. Using a 5-point Likert-style scale of 1 = Strongly disagree to 5 = Strongly agree, the results are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of students’ paired sample t-test on HT awareness and knowledge.

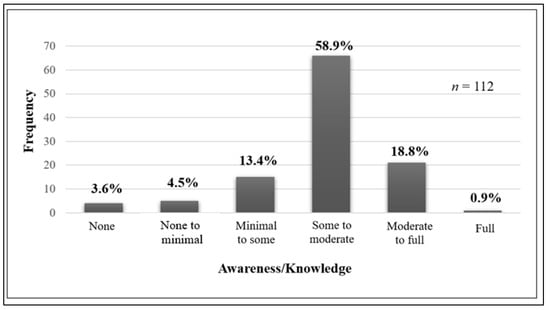

In addition, sum scores were calculated for all nine questions to ascertain a total Perceived HT awareness and knowledge sum score. The mean perceived awareness and knowledge sum score was 29.59 (range 9–45, SD = 7.299). The sum scores were then recoded into categories for further exploration using these categorical measurements. Figure 2 displays the categories and results of the recoded data.

Figure 2.

Pretest perceived HT awareness and knowledge sum scores.

6.3. Posttest Results

Post-Sim Perceived HT Awareness and Knowledge. The participants were asked the same nine questions pertaining to their perceived HT awareness and knowledge after the simulation experience. Using an n = 104 with the identical Likert-style scale, the results are displayed in Table 2.

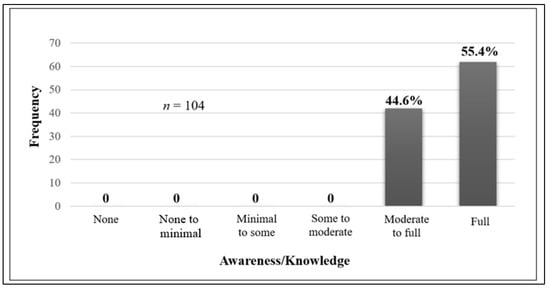

In addition, sum scores were calculated for all nine posttest questions to ascertain a total perceived HT awareness and knowledge sum score post-intervention. With an n = 104, the mean perceived awareness and knowledge sum score was 43.7 (range 9–45, SD = 2.085). The sum scores were then recoded in the same manner as the pretest categories (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Posttest perceived HT awareness and knowledge sum scores.

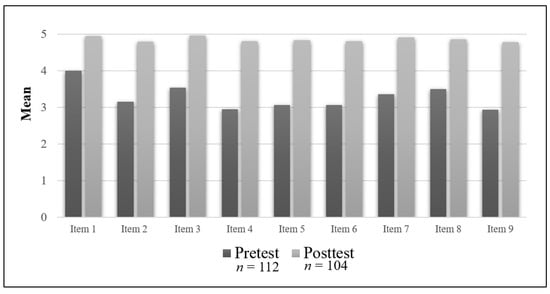

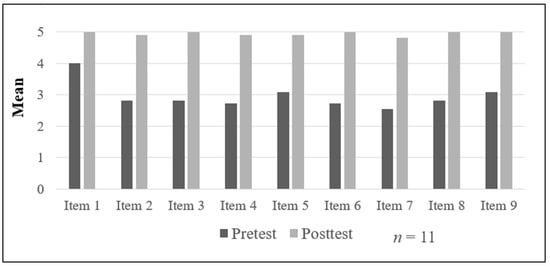

Efficacy of the HT Simulation Pretest–Posttest Comparisons. To measure its efficacy, paired sample t-tests were conducted. Using an n = 104, the researchers noted that all the pretest/posttest paired analyses yielded p < 0.001 with a Cohen’s d > 0.8, indicating a large effect and demonstrating a statistically significant increase in awareness and knowledge gained for all the items examined. The results are presented in Table 2, with an illustrated comparison of the means per variable in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Pretest–posttest comparison of means for HT awareness and knowledge.

6.4. Qualitative Data Results

Seeking to gain a deeper understanding, the participants were asked two open-ended questions. The first sought to ascertain where, if at all, the participants had learned about or became aware of HT. A total of n = 91 responded. After cleaning the data, as some responses were either missing or incoherent text was submitted, an n = 65 was used. With several respondents providing numerous answers in their respective open-text fields, 27.7% (n = 18) responded internet/online/social media, 18.4% (n = 12) responded TV shows or movie(s), 11.9% (n = 8) responded news outlets/newspaper article(s), 13.8% (n = 9) responded prior requirement (work-related), and 46.2% (n = 30) responded no prior exposure or awareness. The second question explored the impact the HT simulation had, if any, on their future nursing practice. A total of n = 89 responses were submitted. The following four themes emerged, with select participant responses shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Themes and representative quotes from participant feedback on HT-focused simulation.

Eye-opening. One of the themes that emerged was eye-opening. A majority of respondents reported that the HT simulation experience had opened their eyes to this hidden issue as it intersects with healthcare.

Educational and Informative. The second theme that emerged was educational and informative. Several respondents reported how educational and informative the simulation experience was for their future practice.

Increased Awareness. A third theme that emerged was an increased awareness of HT, its hidden nature, and its intersection in a healthcare setting.

Preparedness. The final theme that emerged from analyzing the qualitative data was preparedness. Several participants reported how they felt an increase in preparedness to identify and treat this population in a healthcare setting.

6.5. Faculty Outcomes of the HT Simulation Experience

In addition to exploring the outcomes of the experience of the students, the clinical faculty were asked to participate in the study as well as an additional exploratory component. The faculty members were surveyed post-simulation using a more applicable modified version of the HTSEES. Participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained prior to the distribution of the survey.

Sample Characteristics of Faculty. The faculty members who participated in the study included an n = 11 (n = 7 from Cohort #1, n = 4 from Cohort #2). The personal characteristics are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample demographics: Personal characteristics of faculty.

Prior Exposure of Faculty to HT Content. With an n = 11, and with Yes = 1, No = 0, and I don’t remember = 0, the faculty members were asked the following questions. “Were you ever taught on human trafficking during any of your nursing education (prelicensure RN degree or higher)?” showed 100% (n = 11) responding No. The results for the question, “Have you ever had any formal training on human trafficking?” showed a mean score of 0.1818 and SD = 0.4045, with 81.8% (n = 9) responding No and 18.2% (n = 2) responding Yes.

Prior Experience Teaching HT Content. The faculty members were then asked, “Have you ever taught human trafficking content in your role as a faculty member?” The results showed a mean score of 0.1818 and SD = 0.4045m with 81.8% (n = 9) responding No and 18.2% (n = 2) responding Yes.

Perceived HT Awareness and Knowledge of Faculty. The faculty were asked the identical nine HTSEES questions pertaining to their perceived HT awareness and knowledge pre- and post-simulation. Using an n = 11 with the identical Likert-style scale, the results are presented in Table 5 and Figure 5.

Table 5.

Results of faculty’s paired sample t-test on HT awareness and knowledge.

Figure 5.

Faculty pretest–posttest comparison of means for HT awareness and knowledge.

6.6. Qualitative Data Results of Faculty

Seeking to gain a deeper understanding, the faculty were asked, “In your own words, please add any comments or feedback regarding this experience and how it has impacted your nursing practice/knowledge, if at all.” With an n = 11, the following themes emerged, with select responses provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Themes and representative quotes from faculty feedback on HT-focused simulation.

Needed Content. One of the themes that emerged was needed content. Most of the respondents reported that this HT simulation experience needs to be a part of the prelicensure nursing curriculum.

Increased Knowledge and Understanding. The other theme that emerged was increased knowledge and understanding. Most of the respondents reported that the simulation increased identification skills, such as learning new words and phrases, and signs to look for, such as skin branding and behaviors.

7. Discussion

Although sensitive and potentially triggering (Nurses United Against Human Trafficking 2022), teaching HT content using simulation is crucial. The ANA Code of Ethics (ANA 2015) and the AACN Essentials (AACN 2021) outline the duties of nursing professionals to advocate for and protect vulnerable populations. Integrating HT content and an HT simulation into prelicensure nursing curricula underscores the ethical and professional obligations of nurses to provide optimal care to all patients, including this most vulnerable population. The findings of this study suggest that simulation is an effective strategy to prepare nursing students to recognize the red flag indicators of HT. It gave students a comprehensive, immersive experience, which helped them critically think, observe, recognize, and evaluate their patient more effectively. The students were able to build confidence in their abilities to assess, therapeutically communicate, and take appropriate actions, which may also decrease the likelihood of their feeling unequipped, overwhelmed, or powerless when encountering such cases in practice.

The simulation also fostered empathy and caring behaviors in the participants. The facilitators and faculty witnessed the students’ emotional engagement in each group. The students demonstrated therapeutic communication to convey empathy and compassion. The nursing profession stresses the significance of patient-centered care. Most of the participants recognized the standardized patient’s vulnerability and expressed concerns surrounding her safety, presentation, comments, and demeanor. Addressing this topic in prelicensure nursing education ensures that future nurses are not only clinically competent but also morally and emotionally prepared to handle the complexities of HT in their professional roles. Having an evidence-based understanding of this issue can be scaffolded, reinforced, and expanded upon as students progress through their education and into practice.

HT is often unrecognized and/or diagnostically overshadowed in healthcare settings (Bono-Neri 2024; Nurses United Against Human Trafficking 2022). Without proper education, nurses may miss key signs. Introducing HT content early in prelicensure nursing curricula will provide a strong foundation of the knowledge and essential critical thinking and assessment skills needed to identify and respond to potential victims, ultimately improving their health outcomes.

This topic has real-world relevance, as HT is a pervasive humanitarian crisis, and its victims intersect with HCPs during their exploitation (Bono-Neri 2024; Ernewein et al. 2023). On the frontlines, nurses may be among the first to encounter these victims. Educating the next generation of nurses on HT can be lifesaving, as evidenced by a powerful testimonial (edited for deidentification purposes) from a participant, written one year after the simulation-based experience:

“During my Med/Surg clinical, I was shocked to encounter a potential victim. The patient was a 30-year-old woman admitted for trauma. Two classmates and I entered the patient’s room to perform our assessment. I noticed dark circles surrounding her eyes. Contusions covered her face and upper torso with a hematoma located on her upper scalp. When questioned, she insisted it was due to a fall. She appeared dismissive and claimed she was fine, avoiding elaboration. Another notable finding was she wasn’t wearing her gown and didn’t seem interested in maintaining modesty. Being concerned, we helped put on her gown. She responded tearfully, ‘I don’t think anyone would be interested in looking at me.’ Afterwards, my classmates and I, in an empty room, discussed our findings. Alarmed for this patient, I chose to escalate and share these findings with the patient’s nurse. In retrospect, I realized that the choice to do so only occurred because she reminded me of the patient portrayed in the HT simulation during my sophomore year. One of the most important skills learned as a student nurse is the ability to ‘recognize cues.’ Having done this activity, I was able to recognize the cues. However, the sobering reality was these cues may not have been identified had this simulation been excluded from my education. Reflection on the simulation and that patient I encountered has given me a new perspective on the content delivered before entering clinical. The privilege of attending clinical rotations as students is the trust that we will do what is in the best interests of our patients. Our actions at the bedside have real world consequences. A missed opportunity can cost a patient’s life. Therefore, just as we learn CPR to save lives, so too should we learn to perform abuse and trafficking assessments. Just as cardiac arrest can kill, so too can violence. It is therefore vital that we learn assessment and intervention techniques to combat these problems before encountering our first patients as student nurses. To omit this information would be no different than omitting CPR. The HT simulation is crucial content, and its humbling message is to teach the student nurse to recognize cues.”

This testimonial illustrates the powerful effect and retention of the HT simulation, as well as the bridging of this experience to an actual clinical encounter. The student recognized a victim hidden in plain sight who may have otherwise gone unnoticed.

7.1. Limitations

One of the limitations of this study was the use of a convenience sample from a single university. This may have impacted the results and therefore its generalizability. In addition, the study’s focus on second-year nursing students may also restrict its applicability to nursing students at other stages of their education. Another limitation was that all the data were obtained through self-reporting, so response bias may have occurred (Glen 2021). Lastly, the Hawthorne effect may have existed, as this simulation placed the students in a situation that was observed by the faculty and their peers.

7.2. Future Research

Expanding this study to include geographically diverse institutions could provide a more comprehensive understanding of its effectiveness. Additionally, an exploration of the long-term retention of knowledge and awareness gained, as well as an investigation of the impact of such training on clinical practice and patient outcomes, can be studied in the future. Lastly, as this study strictly addressed sex trafficking, other forms of trafficking were not taught; therefore, future research may include other forms such as labor trafficking or organ trafficking.

8. Conclusions

HT is a humanitarian and global public health issue. The scope of nursing education and practice, which additionally addresses the social determinants of health that contribute to poor patient outcomes, is essential. The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, were adopted by the United Nations in 2015, serving as a universal call to action to ensure that, by 2030, all people enjoy peace and prosperity (United Nations Development Programme n.d.). Through the implementation of an HT simulation, this immersive experience will provide a response to HT which will ensure progress towards Goal 5, achieving gender equality, and Goal 16, reducing all forms of violence and promoting just, peaceful, and inclusive societies (United Nations 2024). Early detection and intervention are crucial steps to mitigate and improve these outcomes and directly impact these specific goals.

The early introduction of HT content can help normalize discussions about sensitive and complex issues within healthcare, creating a culture of openness and preparedness. In turn, it can have a lasting impact on nurses’ practice, influencing their approach to patient care, advocacy, and ethical decision-making and yielding a nursing workforce that is better equipped to address public health issues.

Teaching HT content using simulation at the undergraduate level can provide nursing students with consistent and standardized training, thus reducing the variability in knowledge and preparedness that occurs. Its integration can lead to more compassionate, equipped, and knowledgeable nursing professionals who are better prepared to identify and support victims. By engaging in realistic scenarios, students gain a deeper understanding of the physical and psychological trauma experienced by victims, which is essential for providing optimal care in a trauma-informed manner. With proper preparedness, nurses can help break the cycle of exploitation and victimization and provide critical support to these individuals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M., G.C. and F.B.-N.; methodology, D.M., G.C. and F.B.-N.; validation, F.B.-N.; formal analysis, F.B.-N.; data curation, D.M., G.C. and F.B.-N.; writing—original draft, D.M., G.C. and F.B.-N.; writing—review and editing, D.M., G.C. and F.B.-N.; supervision, G.C.; project administration, G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Long Island University, 24/04-040, on 12 March 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. 2021. The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. Available online: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Publications/Essentials-2021.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- American Nurses Association. 2015. Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements. Washington, DC: American Nurses Association. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Standardized Patient Educators. 2020. ASPE Standards of Best Practice (SOBP). Available online: https://www.aspeducators.org (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Bono-Neri, Francine. 2024. Human Trafficking: A Vulnerable Population That Is Seen, Yet Remains Invisible. In Policy and Politics for Nurses and Other Health Professionals: Advocacy and Action, 4th ed. Edited by Donna M. Nickitas, Donna J. Middaugh and Veronica D. Feeg. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning, pp. 107–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bono-Neri, Francine, and Tammy J. Toney-Butler. 2023. Nursing Students’ Knowledge of and Exposure to Human Trafficking Content in Undergraduate Curricula. Nurse Education Today 129: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Kelly, Michelle L. Aebersold, Pamela R. Jeffries, and Suzan Kardong-Edgren. 2020. Innovations in Simulation: Nursing Leaders’ Exchange of Best Practices. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 41: 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisolm-Straker, Makini, Sarah Baldwin, Benjamin Gaïgbé-Togbé, Nneka Ndukwe, Patrice N. Johnson, and Lynne D. Richardson. 2016. Health Care and Human Trafficking: We Are Seeing the Unseen. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 27: 1220–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernewein, Charrita, Francine Bono-Neri, Tammy J. Toney-Butler, and Toni Christopherson. 2023. Healthcare Response to Human Trafficking: Integrating the Social-Ecological Model. In Human Trafficking: A System-Wide Public Safety and Community Approach, 2nd ed. Edited by Jeffrey W. Goltz, Roberto Hugh Potter, Joseph A. Cocchiarella and Michael T. Gibson. Saint Paul: West Academic Publishing, pp. 385–426. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, Jennifer A., and Megan Youngberg-Campos. 2020. Will You Escape?: Validating Practice While Fostering Engagement through an Escape Room. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development 36: 271–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glen, Stephanie. 2021. Response Bias: Definition and Examples. Available online: https://www.statisticshowto.com/response-bias/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- INACSL Standards Committee, Laura Persico, Swathi Ramakrishnan, Barbara Wilson-Keates, Rosanne Catena, Michael Charnetski, Nicole Fogg, Mary C. Jones, Jennifer Ludlow, Heather MacLean, and et al. 2025. Healthcare Simulation Standard of Best Practice®: Prebriefing—Preparation and Briefing. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 105: 101777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INACSL Standards Committee, Pamela R. Watts, Deena S. McDermott, Gabriel Alinier, Michael Charnetski, Jennifer Ludlow, Elizabeth Horsley, Cynthia Meakim, and Pooja Nawathe. 2021. Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice™: Simulation Design. Clinical Simulation in Nursing 58: 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones Day. 2022. Human Trafficking and Health Care Providers: Legal Requirements for Reporting and Education. Available online: https://www.jonesday.com/en/insights/2021/09/human-trafficking-and-health-care-providers (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Kim, Jihee, Juh Hyun Park, and Sungyoung Shin. 2016. Effectiveness of Simulation-Based Nursing Education Depending on Fidelity: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Medical Education 16: 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, David. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, Michaela, Walter Eppich, Jenny Rudolph, Matthew Meguerdichian, Hanspeter Catena, Andrew Cripps, Victoria Grant, and Adam Cheng. 2020. Managing Psychological Safety in Debriefings: A Dynamic Balancing Act. BMJ Simulation & Technology Enhanced Learning 6: 164–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, Laura, and Christopher Wetzel. 2014. The Health Consequences of Sex Trafficking and Their Implications for Identifying Victims in Healthcare Facilities. Annals of Health Law and Life Sciences 23: 61–91. Available online: https://www.icmec.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Health-Consequences-of-Sex-Trafficking-and-Implications-for-Identifying-Victims-Lederer.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Marcinkowski, Brandon, Anthony Caggiula, Brandon N. Tran, Quynh K. Tran, and Amir Pourmand. 2022. Sex Trafficking Screening and Intervention in the Emergency Department: A Scoping Review. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moloney, Maura, Lorraine Murphy, Louise Kingston, Karen Markey, Thomas Hennessey, Pauline Meskell, Sarah Atkinson, and Owen Doody. 2022. Final Year Undergraduate Nursing and Midwifery Students’ Perspectives on Simulation-Based Education: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nursing 21: 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurses United Against Human Trafficking. 2022. The Intersections of Human Trafficking in Healthcare: Unified to Break the Chains [PowerPoint slides]. NUAHT. Available online: https://www.nursesunitedagainsthumantrafficking.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Orlando, Ida Jean. 1990. The Dynamic Nurse-Patient Relationship. New York: National League for Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Toney-Butler, Tammy J., Melissa Ladd, and Olivia Mittel. 2023. Human Trafficking. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430910/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Trafficking Victims Protection Act. 2000. 22 U.S.C.A. § 7102(4). Available online: https://www.congress.gov/106/plaws/publ386/PLAW-106publ386.htm (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- United Nations. 2024. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2024/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2024.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme. n.d.The SDGs in Action. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 20 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).