1. Introduction

In recent years, many social programs have adopted a gender lens to strengthen women’s autonomy and decision-making. This shift has made room for broader participation—in local economies, in community life, and at home—helping to reduce inequalities, improve living conditions, and foster social cohesion, local development, and gender equity (

O’Neil and Domingo 2016;

Sachs and McArthur 2021). Their effectiveness, however, still hinges on how well they engage the whole community.

Within this landscape, the Sembrando Vida Program (PSV) casts women as key actors of local development, with benefits that reach both their households and their communities. However, women’s participation unfolds amid a stubborn reality: rural women continue to shoulder most unpaid labor—care work, domestic tasks, and community support—that keeps households running and sustains social reproduction (

Benería 1999;

International Labour Organization [ILO] 2019). This labor is essential but remains undervalued—in budgets, in statistics, and often in everyday recognition—reinscribing gendered divisions and constraining women’s influence in private and public decision-making (

Folbre 2001).

PSV provides productive opportunities, but such openings do not automatically remove the structural constraints that bind women’s economic contributions to entrenched inequalities (

International Labour Organization [ILO] 2019). The overlap between program-related paid work and the invisible, unpaid workload frequently produces a “double shift,” limiting time, energy, and room for leadership. This tension underscores the urgent need to address the foundations of unpaid care work. It invites a central question: can initiatives like PSV genuinely transform gender relations in rural contexts, or do they risk reproducing inequalities by integrating women into productive roles while leaving the foundations of unpaid care work unaddressed? These potential risks highlight the need for careful consideration and planning in such initiatives.

Historically, development models shaped by androcentrism have deepened gender gaps, disproportionately impacting women in poverty. These models have tended to push women into paid labor without relieving them of domestic responsibilities, effectively doubling their workload and disregarding the vital contribution of unpaid care work to household and community economies (

Benería et al. 2015). While domestic labor sustains both social and economic reproduction, it has remained largely invisible, perpetuating inequalities in access to resources and in social recognition. This invisibility underscores the urgent need for recognition and acknowledgment of the vital role of unpaid care work (

Vega Montiel 2014;

Kabeer 2021).

The unequal distribution of unpaid work mirrors gendered divisions of time, with women assuming most caregiving responsibilities. These demands reinforce traditional stereotypes—women as caregivers and men as providers—and limit women’s bargaining power and influence in household decisions (

Arora 2015;

Bittman and Wajcman 2000;

Floro and Miles 2003). Even when they join the labor market, women often continue to shoulder the primary caregiving role, sacrificing personal time, rest, and self-care (

DANE 2011;

Tribín-Uribe et al. 2022).

This study starts from the hypothesis that Mexico’s PSV enhances rural women’s participation in both productive activities and the care economy. The theoretical framework is structured around four key dimensions: (1) women’s participation in PSV, (2) dynamics of the care economy, (3) historical and theoretical contextualization of domestic work, and (4) transformation of gender roles and community participation. The methodological design includes a detailed explanation of the study approach, followed by the presentation of results on gender-specific attributes of participants, women’s daily routines, perceived benefits of the program, viewpoints of both female and male participants, Content Analysis Test outcomes, emotion-coding results through Emojiology, and narrative production findings. The article closes with a discussion that integrates the empirical evidence with the theoretical framework and presents the main conclusions.

The debate on gender and development has progressively shifted from a welfare-oriented approach toward a more structural analysis of inequalities, a shift that is crucial in recognizing women as active agents of change rather than passive beneficiaries of policy (

Benería et al. 2015). From the perspective of feminist economics, economic development cannot be fully understood without integrating gender as a cross-cutting dimension since social norms and institutional frameworks profoundly shape the allocation of resources, opportunities, and decision-making power.

In rural settings, gender roles have historically been defined through the sexual division of labor, which assigns women to reproductive and care tasks and men to productive activities (

Boserup 1970;

Deere and León 2001). However, processes of globalization and rural transformation have altered these dynamics. As

Ruspini (

2019) notes, globalization has had ambivalent effects on women: while it has intensified vulnerabilities—particularly for rural women facing labor precarity—it has also opened new spaces for agency, collective organization, and participation in local and transnational networks, showcasing the resilience and adaptability of rural women. The transformation of gender roles in rural communities is closely linked to broader development strategies that address structural inequalities. It is crucial that these strategies integrate a gender perspective, as programs like Sembrando Vida do. This approach aims to expand women’s access to productive resources, strengthen their role in community decision-making, and enhance their visibility in local economies. Nevertheless, as

Benería et al. (

2015) argue, without addressing the systemic undervaluation of women’s unpaid contributions, these initiatives risk reproducing inequities in new forms.

1.1. Conceptual Framework

This section synthesizes the theoretical and empirical debates that support the analysis, focusing on the care economy, unpaid work such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare, gender equity, and transformations in social roles within rural contexts.

1.1.1. The Care Economy

The care economy, a web of tasks, relationships, and values that sustain life daily and ensure social reproduction, plays a crucial role in renewing the labor force and sustaining families. It includes both tangible elements—such as feeding, cleaning, organizing, and maintaining the home—and relational and symbolic dimensions that uphold well-being and human dignity (

Elson 2000). This is the sphere where activities like caring for children, supporting older adults or the sick, cooking, preserving the home, and managing the often invisible tasks without which daily life would not function (

Rodríguez Enríquez 2007) take place. Despite being indispensable, these activities have been historically absent from economic accounting and public policy priorities; recognizing and redistributing them is therefore not only a matter of justice but also a precondition for building fairer and more sustainable societies.

1.1.2. Conceptual Perspectives on the Care Economy

The care economy, a comprehensive term that includes goods, services, relationships, and values essential for human life and social reproduction, encompasses both paid and unpaid activities (

Elson 2000;

Folbre 2001). A key insight from feminist economics is the recognition of the vital role of unpaid care work—such as cooking, cleaning, child-rearing, elder care, and community support—in economic systems. It is crucial to note that despite its fundamental importance, this type of work is systematically excluded from conventional economic accounting (

Benería 1999;

Elson 2000), highlighting existing economic disparities.

In rural contexts, unpaid domestic and care work tends to be more intense due to limited access to public services, geographical isolation, and the persistence of gender norms that assign women the primary responsibility for household maintenance (

Deere and Doss 2006;

Pérez 2020). This situation creates a “double workload”, a term used to describe the additional burden women face when they participate in income-generating activities while continuing to shoulder most of the reproductive labor (

Esquivel 2014).

The undervaluation of unpaid care work is not just a statistical gap, but a structural issue that significantly shapes women’s economic opportunities, time allocation, and bargaining power (

Antonopoulos 2009). In the context of rural development programs, the lack of explicit mechanisms to recognize and redistribute unpaid care responsibilities can limit the transformative potential of gender-sensitive interventions. As

Benería et al. (

2015) underscore, it is imperative to integrate care economy considerations into program design—through time-use analysis, provision of care infrastructure, and policies that promote co-responsibility between genders. This will ensure that inclusion is not just a symbolic gesture, but a tangible reality.

From a feminist economics perspective, the care economy encompasses the whole system of activities, goods, and services that meet fundamental human needs—nutrition, health, education, and housing—while revealing how care is socially organized within households. It is central to the reproduction of the labor force and, importantly, it is a key creator of social value, making it essential for both sustainability and collective well-being.

1.2. Historical and Theoretical Context of Domestic Labor

As conceptualized by

Lagarde (

2005), work is a human activity that transforms raw materials for specific purposes, adapting as societal needs evolve. However, labor is inherently gendered, shaped by biological and social constructs. Marx and Engels referred to this as the sexual division of labor, a complex issue that intersects with class, ethnicity, and ideology to create layered systems of hierarchy and inequality.

1.2.1. Gender Equity and Rural Development

Gender equity, a pivotal goal in rural development, seeks to ensure parity between men and women by fostering empowerment and reducing machismo and gender-based violence. In the specific context of rural areas, where the vulnerability and underappreciation of women’s labor are more pronounced, scholars have highlighted the importance of interventions such as women’s cooperatives, educational initiatives, and community involvement. These strategies play a significant role in addressing systemic disparities (

FAO 2007;

Ureste 2016;

Altamirano-Jiménez 2004;

Ranaboldo and Leiva 2013;

Ávalos Aguilar et al. 2010;

TFCA 2016).

1.2.2. Gendered Perspectives on Development

Gender-sensitive development transcends mere resource accessibility; it necessitates fair management and decision-making authority. Androcentric approaches have exacerbated disparities, particularly for rural women who often grapple with a “triple workload” of paid labor, domestic chores, and care work (

Vega 2007). While entry into paid work can bolster women’s bargaining power, it typically augments their overall workload. The absence of indicators that gauge total workload—such as the Global Workload Measurement—and the lack of formal recognition of unpaid care work impede strides towards equity (

Pedrero 1977).

1.2.3. The Invisible Economy of Unpaid Labor

Unpaid labor, predominantly carried out by women, encompasses the production of goods and services for household consumption. This often overlooked yet crucial economic contribution is framed by feminist economics as reproductive labor, vital for family survival and community well-being (

Folbre 2020;

Pérez 2020). Rural women, in particular, play a significant role in reinforcing local economies as they juggle domestic responsibilities with subsistence agriculture (

Benería et al. 2015). In this context, the PSV represents a significant step forward by formally recognizing women’s roles in resource management and capacity building.

1.2.4. Transformation of Gender Roles and Community Participation

In recent years, women’s growing participation in productive activities has influenced gender roles in rural communities, generating changes both in households and in broader economic structures.

Connell and Pearse (

2018) highlight that the sexual division of labor is socially constructed and reproduced through cultural norms. Social programs that integrate a gender perspective promote equity by expanding women’s access to productive roles and leadership positions, thereby strengthening community decision-making processes. Land ownership for women has also enhanced their bargaining power, contributing to empowerment (

León 2008;

Chant and Sweetman 2012). The PSV has helped to extend these processes, although challenges remain in areas such as autonomy, access to services, and overcoming patriarchal barriers.

1.2.5. Gender as a Relational Process and “Tandem Negotiation”

From this perspective, it is worth shifting the focus from the “woman” as an isolated subject to the relational process of gender—understood as something that is enacted and negotiated daily within the family, the workplace, and the community (

West and Zimmerman 1987). In truth, women and men do not operate in separate spheres; rather, they co-manage the “work of gender”—who provides care, who makes decisions, who produces, and when—constantly readjusting rules and expectations according to the real possibilities of the household and the territory. This view resonates with the notion of “tandem negotiation”: couples and households renegotiate norms and hierarchies to make them workable, sometimes reaffirming them and sometimes eroding them (

Bartkowski 2001). Moreover, if we understand that interactions are “framed” by gender beliefs that organize positions and status, it becomes easier to see why certain inequalities persist even when the rhetoric changes (

Ridgeway 2011).

1.2.6. The (PSV) Program: A Key Initiative in Rural Development

The following section presents the main components, operational logic, and the significant gender perspective of the PSV, linking its structure to the analytical dimensions of this research.

1.2.7. Women’s Participation in PSV: A Crucial Aspect of the Program

The PSV, launched in 2019, is a program that is deeply committed to gender equality. It achieves this by establishing agroforestry systems, providing technical and social accompaniment, and fostering community organization through Peasant Learning Communities (Comunidades de Aprendizaje Campesino, CAC), community nurseries, and biofactories (

Secretaría de Bienestar 2025). Operating in 24 states and covering 1.139 million hectares, the program combines monetary support with inputs and training (

Programas para el Bienestar 2025). Eligibility criteria prioritize adults in rural localities with high social deprivation who have 2.5 hectares available for an agroforestry project (

Programas para el Bienestar 2025). The current monthly stipend amounts to MXN 6450, disbursed via Banco del Bienestar, in addition to technical and social assistance; historically, the scheme included a programmed savings component to strengthen household assets (

CIEP 2019;

Secretaría de Bienestar 2019;

DOF 2025). From its design, PSV incorporates a gender-equality approach in its objectives and operating rules; nevertheless, recent evaluations underscore the importance of examining how that perspective is translated into practice—decision-making capacity, available time in the face of unpaid care work, and effective participation in community structures—so as not to limit the program to nominal inclusion alone (

CONEVAL 2024;

DOF 2025). As of 2021, it had reached 433,860 registered beneficiaries (

Pedraza 2021). Unlike previous initiatives, the program integrates both social and technical agricultural advisors, encouraging sustainable land management while creating new job opportunities in rural communities and generating optimism about their future.

1.2.8. Gender-Inclusive Rural Development in PSV

The program seeks to advance food sovereignty through agroforestry, income generation, and capacity building with a gender perspective (

Cornwall 2016). Your role as a development practitioner, policymaker, researcher, or NGO involved in rural development is crucial in this endeavor. Rural development projects can profoundly affect gender relations, especially in contexts where geographic isolation, limited resources, and cultural norms restrict women’s participation (

Benería et al. 2015). Addressing these barriers through gender-sensitive strategies can, paradoxically, strengthen community organization (

Hernández López Luz and Renaud Orozco 2013). Research shows that gender-focused programs enhance women’s autonomy, decision-making power, and community resilience (

O’Neil and Domingo 2016;

Muñoz Gallego and Jiménez de las Heras 2023).

Despite progress, structural gaps persist. Women in Latin America, especially in rural areas, work longer total hours than men, much of it unpaid (

Peña and Uribe 2013). This is an urgent issue that requires our immediate attention. In Mexico, older women devote more time to care work due to shifts in family responsibilities, a disparity tied to insufficient public care services and budgetary limitations.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative-descriptive approach to examine the roles and perceptions of women participating in the (PSV), with a particular focus on its intersection with the care economy, community organization, and productive labor in rural contexts. Fieldwork was conducted at the Peasant Learning Community (Comunidad de Aprendizaje Campesino, CAC) “El Zapotal,” located in Cajón de Piedra, Santo Domingo Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. Established in 2019 through the implementation of PSV, this CAC comprises 27 active beneficiaries, consisting of 20 men (74%) and seven women (26%).

The low proportion of women in the analyzed CAC is not a methodological bias but rather a reflection of the eligible universe under the program’s access rules and, above all, of the historical gap in land tenure. PSV usually requires available land for agroforestry systems (commonly 2.5 hectares), a threshold that many women cannot meet due to inequalities in ownership and control of rural assets. National data are telling: according to the 2022 Agricultural Census, only 19% of production units are headed by women, and when they are, their average size is smaller than that of units managed by men, limiting their ability to meet requirements and sustain projects (

INEGI 2023,

2024). Furthermore, international standards (SDG 5.a.1) reveal a persistent gap in rights to agricultural land between women and men (

FAO n.d.). In this light, the fact that the sample includes few women not only reflects the reality of the CAC but also exposes the structural barriers that shape effective inclusion in programs such as PSV.

The group is primarily composed of adults between 30 and 60 years old; 78% have completed primary school, and 22% have completed secondary school. Regarding family matters, 63% identify as fathers, 26% as mothers, and the remaining 11% as single. Regarding religious beliefs, 59% stated they had no religious beliefs, while 37% identified themselves as Catholic and 4% as Christian. The sample was purposive and convenient, comprising the entire population, which was exclusively made up of active beneficiaries of the Zapotal CAC (Central Community Support Center) officially registered with the PSV (VSP). The methodological decision to work with the entire group was based on three fundamental reasons: (1) access to the program’s official registry was available, which made it possible to identify the universe of analysis; (2) the CAC represents a functional community unit, with specific territorial and operational boundaries, which facilitated access and monitoring; and (3) participants were entirely willing to engage in all phases of the research process, which strengthened the quality and depth of the information collected.

Although women’s narratives are analytically central, male participants were also interviewed/observed with parallel prompts to (i) evaluate women’s activities in productive, community, and care spheres; (ii) indicate whether they recognized gender inequality prior to any policy changes; and (iii) state their willingness to support women (e.g., task sharing, schedule adjustments, and childcare rotations). Their testimonies were transcribed and coded alongside women’s accounts to triangulate interpretations. Accordingly, the Results section includes a brief subsection (“Male participants’ views”) with clearly labeled, representative quotations from men acknowledging women’s double workload and leadership and expressing concrete commitments to support redistributing care work and women’s participation. To ensure methodological consistency, certain criteria were established (

Table 1).

Inclusion was cumulative: participants had to meet all mandatory conditions—(1) active roster status in the CAC “El Zapotal,” (2) age ≥ 18, (3) informed consent—and at least one participation mode (interview or workshop/focus group or observed productive/community activity). Exclusion applied if any mandatory condition was missing or if there was no participation in any mode; additionally, non-rostered individuals and minors were excluded by design. Application: all 27 active roster members were included (20 men, 7 women); no one meeting the criteria was excluded. There were no consent refusals or total absences among rostered members; the only exclusions were by design (non-rostered individuals) (

Table 2).

The methodological work was structured in three sequential phases, carried out between March and August 2024. In Phase 1, held on March 23, a participatory workshop focused on gender and the care economy was implemented. Three main techniques were employed: (a) a brainstorming session to distinguish between sex and gender from a community perspective; (b) the “A Typical Woman’s Day” dynamic (

Geilfus 2002), through which women reconstructed their daily routines, highlighting their domestic and productive workload; and (c) a brainstorming session structured around the benefits of PSV, under categories such as community participation, employment, production, and institutional support. This stage allowed for the development of an initial log of roles and perceptions, which served as input for the next phase.

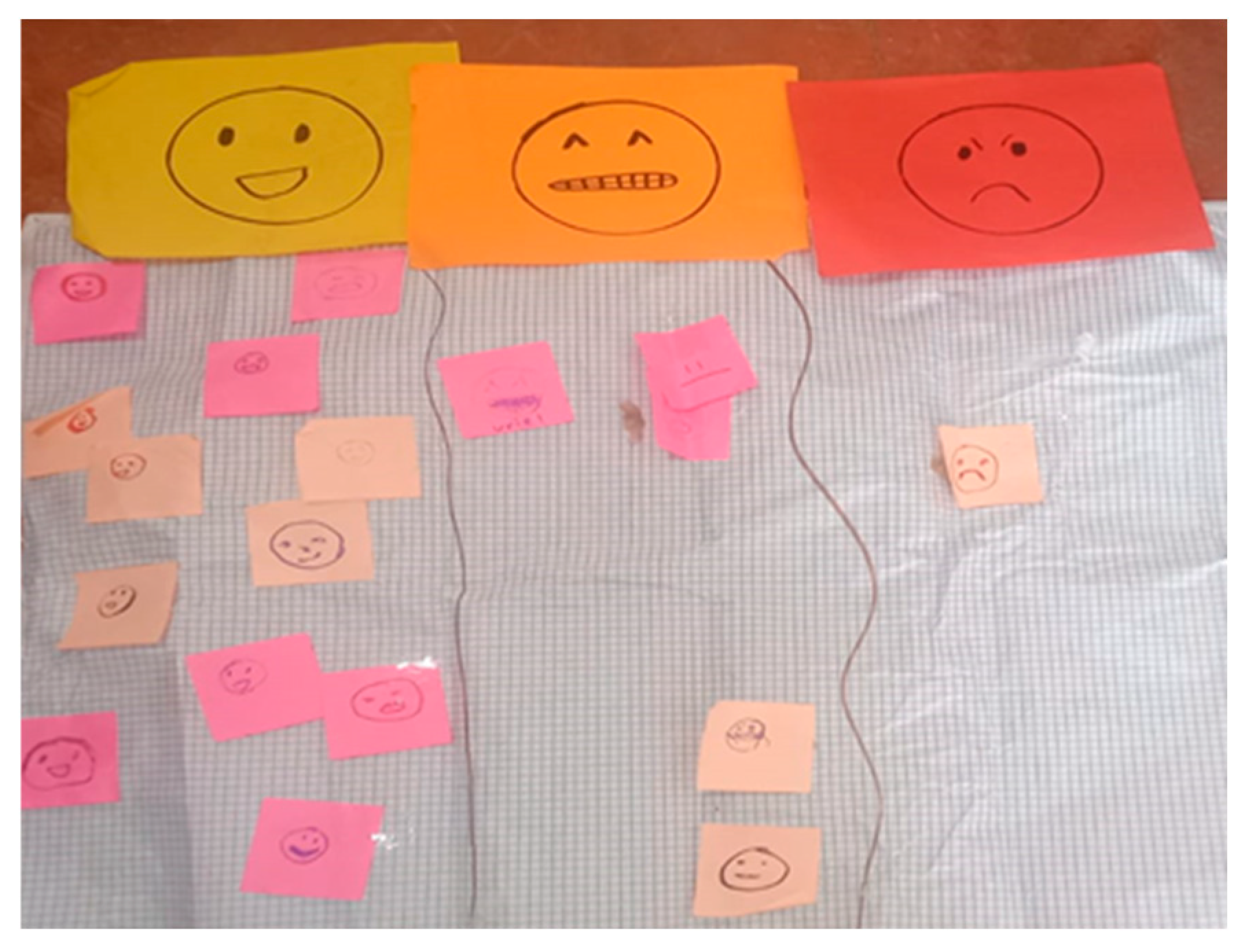

In Phase 2, held on April 23, we implemented the innovative participatory emojiology technique based on visual and affective approaches (

Yáñez-Urbina et al. 2022;

Groys 2012). Using emojis placed on sticky notes, participants represented their emotional experiences within the program. Subsequently, collective slogans and individual narratives were developed, and a listening space was created where community voices shared their experiences, tensions, and assessments (

Figure 1). This phase enabled the incorporation of symbolic and emotional dimensions that do not readily emerge through traditional techniques, sparking a new level of interest in the research process.

Phase 3, conducted on August 30, involved the systematization, analysis, and visualization of data generated in the previous phases. Three complementary tools were applied: (a) the Word Association Test (

Clark 1970), which allowed for the identification of spontaneous semantic associations with key stimuli such as “work,” “care,” or “woman”; (b) the classification of topics in order of perceived importance; and (c) content analysis, based on open and axial coding (

Lucas and Noboa 2014). To strengthen data processing, Python libraries (pandas, nltk, word cloud) were used, which facilitated the generation of frequency matrices, the visualization of lexical co-occurrences, and the creation of word clouds that supported the collective interpretation of discursive patterns.

3. Results

Farmers reported possessing distinct gender-based attributes shaped by community culture, family upbringing, and traditions passed down through generations.

Table 3 summarizes these attributes, as identified using the word association technique.

Participants highlighted differences between men and women but noted that, despite these contrasts, both genders have increasingly taken on similar roles in fieldwork in recent years.

3.1. A Typical Day for Women

Farmers (both male and female) described the daily activities within their family production units. The exercise, also referred to as “Time Use Mapping,” highlighted the multiple roles women fulfill—from household and childcare responsibilities to agricultural labor. While the PSV has facilitated women’s inclusion in productive activities, the burden of domestic work continues to fall disproportionately on them, constraining their personal development (see

Table 4).

PSV has positively influenced women’s perceived empowerment in both familial and community roles. Beneficiaries reported satisfaction with the economic support but highlighted persistent challenges, including excessive workloads and the pressing need for additional financial resources. Overall, women perceived that the program has enhanced their community standing, increasing their visibility in decision-making processes. However, critical gaps remain in infrastructure and resource management.

Francisca Villalobos, a 35-year-old participant, stated:

“Even though I work in the fields and contribute to the program, I still have to manage all household chores at the end of the day.” This sentiment was echoed by many women, highlighting the significant workload they bear despite their contributions to the community.

During workshop debriefings, women farmers (sembradoras) reflected on the time invested in self-care (minimal) and PSV’s measurable benefits for empowerment and decision-making agency.

Both women and men participants have started to reconsider domestic labor divisions, marking a significant step towards gender equality. While spouses, sons, and daughters do participate, their involvement varies significantly across households. Women consistently bear a disproportionate burden—one that remains socially invisible and economically undervalued. As noted during discussions, monetizing this unpaid labor would prove prohibitively expensive for families.

Table 5 summarizes the participants’ consensus on the benefits of PSV, highlighting these gender disparities.

The research employed a Word Association Test (WAT) methodology, revealing eight semantically clustered concepts as visualized in

Chart 1. This projective technique uncovered participants’ implicit cognitive frameworks regarding gender roles and agricultural participation.

The word woman is associated with terms such as strength, resilience, family, and sacrifice, evoking values like fortitude, perseverance, and commitment. Women farmers (sembradoras) particularly value their resilience in the face of challenges, as their responsibilities span both domestic and productive labor. The term family further suggests that women perceive themselves as pillars of unity and stability, underscoring their central role in the household—as captured in the statement: “Being a woman means working every day for the well-being of my children and my community” (María López, 27 years old).

The word “home” is tied to notions of responsibility, care, children, security, and protection, reflecting the perceived role of women within the family. The home is prioritized in their lives as a space of care and safety, aligning with the protective and central function they exercise within the family unit.

The word work (trabajo) is associated with strength, sacrifice, and necessity, suggesting constant effort and perseverance, essential for subsistence. The term “daily” underscores unwavering dedication, while “necessary” reflects the importance of familial and communal labor, as expressed by farmer Rosalinda Santiago (68 years old): “Work is what sustains us and gives us value, both at home and in the fields.” Beyond its practical function, work is also perceived as a means of self-fulfillment and a contribution to collective well-being.

The word program is linked to support, aid, and improvement, highlighting the significance of domestic labor for community sustainability. Responses tied to “program” were positive, associated with terms like support and mutual aid, which convey a sense of security and solidarity among beneficiaries. The connection between “program” and “improvement” or “hope” suggests that women farmers view the PSV as an opportunity to enhance their living conditions.

Regarding leadership, the most frequent associations were decision-making, trust, power, and visibility. These responses reflect perceptions of empowerment and self-confidence, with women farmers emphasizing control and influence by equating leadership with autonomy and authority. Such perceptions suggest that the PSV has enhanced women’s visibility in their communities, enabling them to assume active decision-making roles.

When we talk about collective solidarity, the term ‘community’ evokes ideas of support, growth, collaboration, mutual aid, and development. The values of ‘Collaboration and support’ underscore the importance of the community network, while ‘change and growth paint a picture of the community as a space for improvement and transformation. The concept of ‘support’ is closely tied to security, peace of mind, backup, and necessity. In this context, it is clear that women in the program value the support they receive. As Ms. Claudia Martínez highlighted, ‘The financial support they receive provides them with a sense of security and peace of mind that they did not have before, enabling them to focus on other activities and strengthen their role in the community.’

3.2. Content Analysis Test

This section presents the results of the content analysis test, structured into three main categories:

Women’s Empowerment and Revaluation of Domestic Roles.

Operational Challenges and Workload.

Transformation in Decision-Making and Community Participation.

The analysis drew on participants’ testimonies to identify recurring themes and keywords in their perceptions of their roles and the program’s impact. Notable terms such as support, role distribution, difficulties, and challenges emerged, reflecting how the program influences women’s recognition within their families and communities.

3.3. Women’s Empowerment and Revaluation of Domestic Roles

The term support (Apoyo) was frequently mentioned. The economic assistance provided by the program was highlighted in participatory workshops, with women expressing satisfaction as it bolstered their household income. Farmers (sembradoras) are no longer identified solely as caregivers but as active contributors to the family economy. As Claudia Martínez (50 years old) noted:

“The support we receive does not just help at home—it also lets us contribute to the community and share our knowledge with other producers.”

Another key finding was the identification of challenges related to resource and infrastructure management. Words like “drought,” “water scarcity,” and “field problems” pointed to constraints affecting both production and work–life balance. Water shortages and crop maintenance difficulties have increased the time and effort women must dedicate to productive activities, directly compounding their overall workload. Mayra Aguilar (28 years old) explained:

“Lack of water is one of the most serious issues; sometimes we must choose between tending the fields or our homes.”

Thus, the PSV should prioritize implementing irrigation systems and water catchment infrastructure to enhance the program’s long-term sustainability.

3.4. Emojiology and Narrative Production

The activity was structured into four main stages: (a) group preparation, (b) co-construction of guidelines, (c) emojiology and narrative production, and (d) listening space.

Below is a detailed description of each stage:

Stage 1: Group Preparation

Participants were given sticky notes (post-its) to place on a large sheet of paper (papel bond), selecting either a happy face (😊), neutral face (😐), or sad face (😞) to represent their level of satisfaction with their participation in the PSV.

Stage 2: Co-construction of Guidelines

In the emoticons activity, which assessed perceptions of the PSV, the results were as follows:

12 Beneficiaries chose a smiling face, indicating a positive perception.

5 beneficiaries selected a neutral face.

1 beneficiary chose a sad face, highlighting areas needing improvement.

Stage 3: Emojiology and Narrative Production

Based on the emoticon results, participatory dialogues were generated to explore experiences in greater depth.

Positive feedback centered on empowerment and inclusion in economic decision-making facilitated by the PSV.

Less favorable perceptions centered on infrastructure challenges and limited access to resources.

Farmers generally viewed the program as a support mechanism for their community work, though they also noted areas for improvement (see

Figure 2).

Stage 4: Listening Space

The fourth stage was a dynamic process of co-creating a participatory space. Here, farmers actively shared their perspectives with workshop facilitators and the Community Advisory Committee (CAC). This active participation was instrumental in validating the knowledge production methodology from the participants’ standpoint.

3.5. Word Cloud Analysis

The word cloud (

Figure 3) was generated through (1) semi-structured interviews, (2) participatory workshops, and (3) participant observation data PSV. This textual visualization mapped networks of perceptions, emotional responses, and value systems regarding women’s community roles and program participation. The computational analysis was conducted using Python’s 3.0 natural language processing libraries, with size–frequency relationships representing term prominence in participants’ discourse.

Keywords represent central themes in the lives and experiences of the participants. Key terms such as program, women, work, empowerment, and leadership stood out, reflecting the recognition of the role of planters in the home and community. The PSV has strengthened the participants’ self-esteem, giving them greater control over their decisions and visibility in community spaces. Work has been perceived as an obligation and a source of identity, with empowerment having economic and social effects. Words such as support, community, and participation not only highlight the value of solidarity but also the strength of the community and the support offered by the program. The women associate the success of the PSV with improvements in family and community well-being; the words resilience, need, care, and effort reflect women’s roles and the double workload they face. Finally, the word hope reflects optimism toward a more just future and the strengthening of their local economy at the community level.

The figure’s font size corresponds to the relative frequency of mentions in participants’ responses, which was derived from the coded corpus. In this visual representation, larger words indicate a higher frequency and salience in the participants’ responses, providing a clear and concise overview of the research findings.

4. Discussion

Women struggle against systemic barriers and internalized constraints to reclaim their dignity (

Fraisse 2003, p. 43). Their participation in the PSV aligns with empowerment theories, which posit that access to productive resources and involvement in development programs enhance women’s decision-making agency (

Gil Lacruz et al. 2008;

Kabeer 2021). The women farmers, referred to as ‘sembradoras’ in the local context, reported feeling more valued and empowered in both familial and economic spheres, suggesting that development initiatives—when designed inclusively—can foster not only economic independence but also stronger social networks within communities (

Cornwall 2016).

The revaluation of women’s domestic labor emerges as a key factor in sustainable rural development. To further the PSV’s impact, we recommend integrating participatory methodologies that center on the needs of rural women. As

Cornwall (

2016) argues, development programs must be inclusive, moving beyond economic empowerment to strengthen social ties and drive communal transformation. Active participation in the PSV has not only improved women’s economic standing but also elevated their role within rural social structures.

Similarly, this resonates with

López Rodríguez and Hernández Guevara’s (

2019) assertion that social change in rural contexts must stem from recognizing women not as passive beneficiaries but as active agents of change. Their narratives reflect a shift from marginalization to leadership—a transition underscored by terms like empowerment, community, and hope in our word cloud analysis. However, persistent challenges (e.g., resource scarcity, double burdens) highlight the need for structural interventions, such as irrigation infrastructure and care-work support, to sustain these gains. We therefore recommend implementing strategies to improve sustainability and reduce women’s total workload, enabling their full participation in productive and community activities without compromising personal time and well-being.

From this perspective, offering practical examples of how future lines of research can open real spaces for women’s participation and empowerment helps translate our findings into doable pathways. We propose small, participatory pilots within the CACS that (a) test care-co-responsibility labs, where women and men map household tasks using time-use diaries and agree on feasible redistributions; (b) build community leadership schools for women, mixing peer mentoring, intrahousehold negotiation, and project management; and (c) create care supports during assemblies and workdays (e.g., rotating community childcare), then track effects on attendance, voice, and decision-making. Given men’s roles in household dynamics, a short training track for men—focused on “caring masculinities,” conflict resolution, and shared financial responsibility—can be delivered by PSV’s social teams in brief synchronous sessions before or after agroforestry activities, so it does not add time pressure. Program integration can be straightforward: micro-modules with certificates, adjusted assembly schedules to accommodate care, and participation targets (e.g., at least one male household member attending co-responsibility sessions). Finally, we recommend evaluating outcomes with gender-sensitive indicators—time use, agency in household and CACS decisions, tenure in community roles, and access to inputs and land—to distinguish rhetorical change from substantive transformations. In sum, these steps move initiatives like PSV beyond nominal inclusion toward meaningful equality, while strengthening community cohesion and the long-term viability of rural development.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this study was achieved, which is to analyze women’s participation in the PSV in terms of community participation and the care economy in rural contexts. It was identified that social programs have had ambivalent impacts, having a positive impact on poverty reduction at the time of intervention, but have reproduced gender stereotypes and inequalities in social programs and households. The program has established mechanisms to include women in its beneficiary population, representing 7.6%. However, inclusion and effectiveness remain limited, especially on the issue of land ownership, which is a significant conditioning factor. In the communities, it was found that conditions of subordination and autonomy still exist, with which women struggle daily against stereotypes of submission that they must confront in social and cultural structures, raising questions about whether this is a change in discourse or a transformation at the social level. It is proposed that future lines of research, driven by the ongoing importance of academic inquiry in this field, continue to generate spaces for women’s participation and empowerment and analyze the conditions of traditional social policies.

From this perspective, the findings show that women’s participation in programs like PSV is not captured by simply counting how many names are on the roster, but by looking at how they participate and how deeply they are involved; put plainly, the quality of that experience matters as much as its reach. Lasting change takes more than formal access to benefits: it calls for redistributing resources, opening real spaces for decision-making, and fairly recognizing women’s contributions in both productive work and care. With this in mind, while structural anchors persist—land-tenure regimes, gender norms, and community hierarchies—public policy must move beyond symbolic inclusion toward concrete strategies that dismantle those barriers. The urgency for immediate action is clear, as doing so not only advances gender equity; it also strengthens the social fabric and sustains the viability of rural development over time.