Abstract

Recent theories of citizenship call into question the dominance of ancestry (jus sanguinis) and territory (jus soli) as the primary criteria for membership in a polity. Debates around postnationalism, cosmopolitanism, and transnationalism increasingly locate the legitimacy of citizenship in world-level models of rights that extend beyond the state. Yet national citizenship remains remarkably persistent, posing three interrelated puzzles for the sociology of citizenship: (1) How can rights-based and birth-based legitimations of citizenship be reconciled? (2) How can citizenship be conceptualized in non-national terms without eroding the state’s central role? (3) How can we account for the rise of multinational citizenship rights? Drawing on recent global shifts in nationality laws, this article offers a unified analytical framework to address these puzzles through the concept of modular citizenship, which inverts the conventional understanding: it is not the juridical category of citizenship that determines the scope of rights, but the enforceable rights themselves that determine the quantum of citizenship.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of a rapidly expanding world society, the notion of citizenship is increasingly conceptualized beyond the framework of the nation-state. From the nation-blind approach of cosmopolitanism (Habermas 2010; Brown and Held 2010; Benhabib 2008) to explorations of postnational membership (Soysal 1994; Jacobson 1996), transnational citizenship (Bauböck 1994), flexible citizenship (Ong 1999), or diasporic citizenship (Laguerre 1998), the language of citizenship appears to exceed the limits of national citizenship. In this rich scholarly landscape, however, a theoretical question remains elusive: if cosmopolitan, postnational, or transnational citizens must be citizens “of” something, what is that something? Do these newer forms of citizenship have a referent other than the nation? To reconcile the puzzling persistence of national citizenship with postnational, transnational, and cosmopolitan scholarship, I propose a framework for citizenship that does not refer, at its genesis, to the nation-state; it identifies the state as the sole enforcer of rights in a regime of what I call “modular citizenship.”

Modular citizenship refers to a reconceptualization of citizenship as a flexible and reconfigurable framework rather than a fixed status. It brings together two closely related dimensions. The first is modularity: the idea that citizenship is composed of distinct “modules” of rights or building blocks—such as civil rights, political rights, social benefits, and mobility rights—that can be added, removed, or restructured by the state without undermining the coherence of the whole system. Much like components in a modular design, these rights can be rearranged or substituted to fit different social, political, or economic contexts. In practice, this already is the case where some rights are added or removed by the states for different sets of population. The second dimension is modulation, which emphasizes the state’s active role in calibrating how these rights are distributed. Through modulation, the state can adjust not only the composition (which rights are included or excluded), but also the quality (the strength or robustness of rights, such as stronger versus weaker protections) and the quantity (the scope or number of rights available to an individual). In short, I theorize citizenship not as a system of national enclosures, but as one of floating controls and conditional inclusion.

But are the two not inherently connected? Does community membership not entail a certain collection of rights? We have long known that national citizenship contains within a blend of two principles: one rooted in identity and the other in rights. True, the membership model does offer us identity as well as rights, yet it has struggled to keep them together, plagued by contradictions and complexities since its inception. Internally, the politics of community membership has had difficulty unifying the increasing clamor of identities into a standardized national form. And at its borders, it has struggled against the forces of migration. The conundrums of the politics of membership have been well-articulated in citizenship scholarship (Brubaker 2010).

My discussion of modular citizenship, to be clear, is not a claim to novelty. Indeed, the literature on postnational or cosmopolitan citizenship, despite the language of membership, signals a novel understanding of citizenship that challenges the dichotomous—member/non-member—conception of citizenship. Given the growing communication complexity of world society, the key working distinction shifts from member-nonmember to eligible-ineligible claim or conduct (or access-denial), even though the politics of membership remains strong in all nation-states. Rather than thinking of citizenship in terms of “in or out,” it is more appropriate to capture it in terms of “more or less.” My approach is thus based on degrees of citizenship rather than the usual citizen–noncitizen framework. It is no longer useful, I explain, to think of citizenship in terms of one’s blanket membership in a national club; instead, citizenship has grown to be a measure of modulated access to a variety of rights, broadly conceived as social, political and civil rights in the wake of T. H. Marshall’s (1950) pivotal reconstruction of citizenship. While Marshall’s formulation took the form of a contract between the state and the citizen, my task in this article is to provide an alternative framework for citizenship as a context-dependent activation of differentiated rights in a stateless world society. The nation-state remains a referent of citizenship but not as a vessel containing members; rather, the cross-cutting authority of states is seen as implementing and distributing a highly differentiated set of rights across the world.

Modular citizenship captures two related ideas: modularity, where citizenship consists of distinct modules of rights that can be altered or replaced without disrupting the overall structure, and modulation, the state’s ability to adjust the composition, quality, and quantity of rights available to individuals within its jurisdiction. In short, I theorize citizenship not as a system of national enclosures, but as one of floating controls.

Before I analyze how modular citizenship may be conceptualized in theory and how it is being realized in practice, let me briefly describe the structure of this paper.1 I start by analyzing national citizenship as a form of strong, embedded, or fixed citizenship, identifying several paradoxes inherent in models of fixed citizenship. Three alternatives to national citizenship—cosmopolitan, postnational, and transnational frameworks—are then discussed. Later, I analyze how my thesis of citizenship as a variable basket of rights moves the debate forward, and how it resolves the tension inherent in fixed citizenship. Finally, I discuss some implications for future research.

2. National Citizenship and Its Paradoxes

Based primarily on inheritance, national citizenship is characterized by strong, illiberal norms of membership (e.g., Bauböck 1994; Carens 1987; Shachar 2009). Two primary criteria of membership in a modern nation-state are deeply ascriptive in nature, namely, jus soli (the law of the soil) and jus sanguinis (the law of blood). To be a citizen, one must either be born within a territory (jus soli) or be related to a citizen by blood (jus sanguinis). Deriving citizenship from the accident of birth, nations have for the most part succeeded in making one’s membership in a polity not a matter of decision but of fate, demanding exclusive allegiance based on fixed territory or ancestry.

Strong norms of national citizenship trace back to segmentary societies—small, densely knit agrarian or itinerant communities—where an individual’s position in the social order was fixed and not subject to change through performance (Luhmann 2012). Belonging in these communities was rooted in place, kinship, or both; members typically lived in close proximity and knew one another personally. Birth into a particular kinship network and/or place determined one’s status and identity. The significance of place in shaping durable constructions of identity, interaction, and memory is well documented across disciplines: in sociology (e.g., Simmel [1903] 1950; Gieryn 2000), anthropology (e.g., Augé 1995; Feld and Basso 1996), and philosophy (e.g., Heidegger 1971; Bachelard 1964; De Certeau 1984; Casey 1993). Likewise, the structuring role of kinship systems is extensively explored (e.g., Lévi-Strauss 1969; Radcliffe-Brown and Forde 1950). The strong law of blood (jus sanguinis) invoked in national citizenship appears to simulate kinship-based models, while the equally strong principle of the soil (jus soli) echoes place-based norms of village-like settlement.

It would be easier, Anderson (1991) argued, to think of nationalism in the manner of kinship and religion rather than liberalism or fascism. But no true kinship is possible at the scale of the nation-state. Anderson himself acknowledges that its members cannot personally know one another in any meaningful way. Nations arise not from interpersonal bonds but through systemic forces—print, media, mass education, transport, and industry (Anderson 1991; Gellner 1983). Thus, a nation becomes an “imagined community” not through collective will, but out of necessity—because at the geographic scale of the nation-state, imagination is the only means by which a sense of community can be invoked.

Two paradoxes emerge from imagining community at the national scale. First, the paradox of a “community of strangers” challenges the plausibility of extending place-based solidarity to an abstract population dispersed across a vast territory. This jus soli paradox raises the question of whether such a population can truly constitute a community—if, as Nisbet (1966) suggests, community entails relationships marked by personal familiarity, emotional depth, moral commitment, social cohesion, and temporal continuity. Indeed, attempts to transform this dispersed population into a unified community give rise to a second paradox.

The jus sanguinis paradox lies in the dual coding of member identity as both ascriptive and voluntary. Kinship-based inclusion, determined at birth, is inherently ascriptive, whereas national citizenship is conceived as voluntary membership in a democratic constitutional state—an idea rooted in the Kantian and Rousseauian tradition, where the addressees of the law are also conceived of as its authors (Bauböck 1994; Habermas 1998). This tension—between the particularism of a community defined by language, ethnicity, and history, and the universalism of an egalitarian legal order—marks both the achievement and the failure of the nation-state. It is an achievement in that the nation-state managed to scale up the model of social solidarity from small, intimate communities—where everyone knows one another—to a vast territorial entity, where strangers imagine themselves as part of a shared national identity. Yet it is also a failure: the kinship-like solidarity that sustains small communities is nearly impossible to replicate across millions within national borders. Ethnic difference often emerges as a problem to be solved in most nation-states (Appadurai 2006; Calhoun 1993).

The consequences of this paradoxical coding of citizenship—as both voluntary, formally equal membership and inherited, ascribed status—are far from academic. They have produced profound real-world effects. The combination of large territorial scale with the ideal of kinship-like cohesion inevitably generates “anomalous” populations—groups that do not conform to dominant frameworks of ethnicity, language, or religion. These minorities are neither enemies nor criminals, yet they are often subject to majoritarian hostility and scapegoated in times of political or economic crisis. The paradox becomes starkly visible when the legal equality of citizenship fails to protect minority groups from exclusion or violence. What modern states have enacted, then, is a paradoxical legalization of ancestral and territorial forms of belonging—a hallmark of segmentary, small-scale communities. Yet in large-scale modern societies, it is difficult to reduce citizenship to either territorial or kinship principles.

Naturalization policies, one could argue, evolved as a pragmatic attempt to sidestep the paradoxes of citizenship. They offer a domain in which states can open pathways for incorporating migrants as citizens (Bauböck 1994). Yet naturalization itself was initially shaped—and constrained—by the ethnic principle. The U.S. Naturalization Act of 1790, for example, explicitly grounded citizenship in racial terms: “Be it enacted … in Congress assembled, that any alien, being a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years, may be admitted to become a citizen thereof…” Although the racial prerequisite for naturalization was formally abolished in 1952, ambiguities surrounding membership have endured into the twenty-first century. Indeed, most modern institutions—education, health, law, the market, and the state—despite having little functional connection to race, ethnicity, or religion, still grapple with racial issues within their organizations.

Another response to the paradoxes of national citizenship, one can argue, includes the emergence of a post-war human rights regime in the wake of horrific consequences of nationalism. Unlike citizen rights, human rights by default include all of humanity, erasing the boundary between the citizen and the alien. This shift underpins much of the cosmopolitan, postnational, and transnational citizenship literature (Kant [1795] 1970; Habermas 2010; Archibugi 2004; Bianchi 1999; Camilleri and Falk 1992; Beetham 1999; Soysal 1994; Bauböck 1994, 2003). These frameworks expose the limits of ascriptive membership, both as a norm and practice, in the global age. Despite significant differences, these frameworks trace citizenship and the source of its legitimacy to world-level models of rights outside the contract between the state and citizen. They tend to resolve the paradox of inherited citizenship through the newer frameworks of rights-based membership, placing the nation-state as the mediator or enforcer of the rights emerging from world society.

A major criticism of cosmopolitan and postnational citizenship theories is their perceived neglect of the enduring strength of national citizenship. Portes et al. (1999) caution against overstating the language of universal rights or the reach of migrant transnationalism by framing it as a challenge to the nation-state system itself. Yet it would be a mistake to interpret postnationalism as oppositional to the nation-state. On the contrary, the phenomenological argument at the core of postnationalism views nation-states as actors within world society (Meyer 2010).

A more substantive critique of postnationalism challenges two of its foundational claims. First, Joppke (2001) disputes the notion that the expansion of rights for non-citizens stems primarily from the global human rights regime. Instead, he contends that domestic legal systems—particularly the principles applied by national courts—have been more decisive in extending rights to resident foreigners. Second, the claim that citizenship is shifting away from birthright toward a foundation in universal personhood and human rights remains, at best, premature. As Bosniak (2008) notes, exclusionary policies, deportations, and systemic human rights violations against those without birthright citizenship continue to undermine this ideal. Shachar (2009) similarly argues that while the aspiration toward universal personhood may one day be realized, it has not yet arrived.

The model of modular citizenship resolves the above debate through a clear theoretical solution. While citizenship practices in general cannot be shown to have switched from birthright to human rights, this model explains how the rights-based mutation has assimilated birthright itself as one and only one of the parameters of citizenship. For the rights-based framework to work, it is important to forgo the language of citizenship as an identity-based membership in a polity. A theory grounded in rights-based legitimacy does not need to be anchored in the early modern semantics of membership. Instead, I propose a non-normative model of citizenship as a modulated basket of rights that includes but goes beyond the human rights regime. Following Hegel, one can recover a more elemental development of rights from the arbitrary assertion of individual will (abstract right) to rights rooted in collective recognition and agreement (Hegel 2015). This shift allows us to conceive of citizenship not as a fixed identity but as a flexible, institutionalized configuration of rights.

3. From Membership to Modulation

Citizenship debates have long unfolded within the framework of membership in a sovereign polity. At the outset, it is worth noting that the national model of membership introduced a radically new conception of the social. No longer could one presume that citizens differed by estate, rural or urban origin, or the stratum into which they were born. They no longer differed in their status as citizens, only in what they made of that status. Within the boundaries of the nation-state, this model allowed for the erasure—or at least the formal disregard—of distinctions based on caste, class, race, or inherited privilege, while paradoxically preserving the immutable, birth-based logic of premodern social belonging.

By grounding membership in “nature”—whether through territory or ancestry—national citizenship presented itself as strong, predetermined, and non-contingent. In truth, however, it masked the contingency of a prior constitutional decision that linked modern institutional membership to naturalized forms of belonging. Pre-modern social formation was arguably more effective at concealing this contingency, locating birth-based affiliation outside the domain of human choice or political deliberation. In contrast, a modern democratic polity cannot avoid confronting the contingent nature of its foundations, for the role of the citizen presumes the capacity to participate in defining the very terms of belonging. No form of modern membership precedes the law. Throughout the twentieth century, however, significant efforts were made to obscure this contingency by tethering citizenship tightly to ancestral or territorial bonds within a single sovereign polity. The League of Nations (1930) Convention on Nationality exemplifies this drive for closure, asserting that “every person should have a nationality and one nationality only.”

However, the identity-based membership framework of modern citizenship begins to unravel on both internal and external fronts. Internally, it struggles to account for the ambiguous status of immigrants and permanent residents. As Soysal (1994) notes, non-citizens—whether immigrants or visa holders—do enjoy certain rights, however meager compared to those of citizens. Yet they remain outside the bounds of full membership. This raises a legitimate, though difficult, question: are they partial members—one-quarter, one-third, one-half—or non-members altogether due to their incomplete rights? Complicating matters further, even some formal citizens lack access to the full suite of rights. In many states in the U.S., for instance, felons are barred from voting even after serving their custodial sentences. The rights available to such citizens may, in fact, be fewer than those granted to permanent residents. If the membership model continues to exclude permanent residents as non-members, it must then explain how “non-members” can, in some cases, possess more rights than recognized members. Moreover, by excluding large populations—undocumented immigrants, visa holders, permanent residents, and others who live, work, and contribute to society—the membership model becomes increasingly out of step with political, civil, and social realities.

One may argue that citizenship is not a matter of rights alone; it is also of duties and responsibilities such as paying taxes or serving in the military. Regarding taxation, however, it is no longer accurate to suggest that formal citizens are the only tax-paying members supporting the infrastructure of a welfare state. In fact, it is estimated that the average tax rate for undocumented immigrants is higher than the rate paid by top earners in the United States2. Despite their participation in the tax regime, these individuals remain ineligible for political rights and often cannot access key economic benefits, such as Social Security.

Military service presents a similar paradox. Immigrants have a long history of military participation in the United States. Each year, the U.S. military enlists approximately 5000 non-citizens (National Immigration Forum 2016). Immigrants have been awarded more than 700 Congressional Medals of Honor (US Citizenship and Immigration Services 2020), roughly 20 percent of all recipients, yet federal law prohibits non-citizens from attaining officer rank.

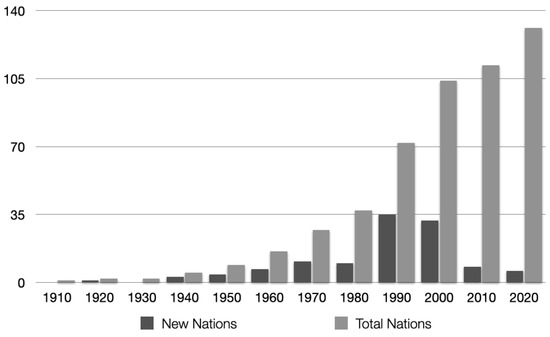

Beyond national borders, the membership model of citizenship fails to account for the growing disparity between individuals with citizenship in a single country and those who possess citizenship-like rights across multiple jurisdictions. The model, anchored in a singular sovereign framework, is ill-equipped to distinguish among classes of individuals whose global baskets of rights vary considerably. It cannot accommodate the rise in non-exclusive forms of belonging—such as dual and multiple citizenships, deterritorialized diasporic affiliations, class- and credential-based citizenships, or bilateral treaties that extend welfare rights to immigrants. While these factors carry different weight across contexts, the global trend is clear: the number of countries permitting such non-exclusive arrangements has increased dramatically, with my research showing that more than 131 nations now recognize some form of these statuses (see Figure 1). These developments signal a partial deterritorialization of citizenship, challenging the foundational assumption of a neat overlap between citizenship and territorial sovereignty.

Figure 1.

Progressive rise in the number of nations permitting dual and multiple citizenship.

The term dual citizenship is itself misleading. It conceals the fact that the rights conferred under such arrangements vary significantly across cases. The membership-based model underlying the language of dual citizenship obscures critical differences in both the quality and quantity of rights available in one context versus another. In some instances, it even prevents countries from acknowledging that they offer dual citizenship at all—as in India—or leads others, like the United States, to remain officially silent on the matter. India’s Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) status exemplifies this confusion. Despite its name, OCI is explicitly not considered citizenship under Indian law, as Article 9 of the Constitution prohibits dual nationality. Yet the very use of the term citizenship introduces ambiguity. This ambiguity arises largely from the limitations of the political membership framework, which cannot adequately capture OCI’s package of non-political rights. By contrast, the model I propose reconceives citizenship as a modulated basket of rights, enabling systematic comparison across cases. In an era marked by the continuous differentiation of mobility, residency, work, welfare, and property rights, so-called dual citizenships no longer offer a uniform status. Instead, they reflect diverse and context-specific configurations of access and protection—configurations the membership model is ill-equipped to grasp.

In practical terms, citizenship already functions as a state-modulated basket of rights, reflecting the availability of services and protections at specific times and places. It is less a fixed identity than a shifting configuration of access, contingent on jurisdiction and context. Citizenship is thus better understood not as membership in a sovereign mold, but as a function of governmental modulation: as individuals move across affiliative settings, their rights are selectively activated, suspended, or transformed according to the jurisdiction and the statuses it assigns—tourist, skilled worker, resident, and so on.

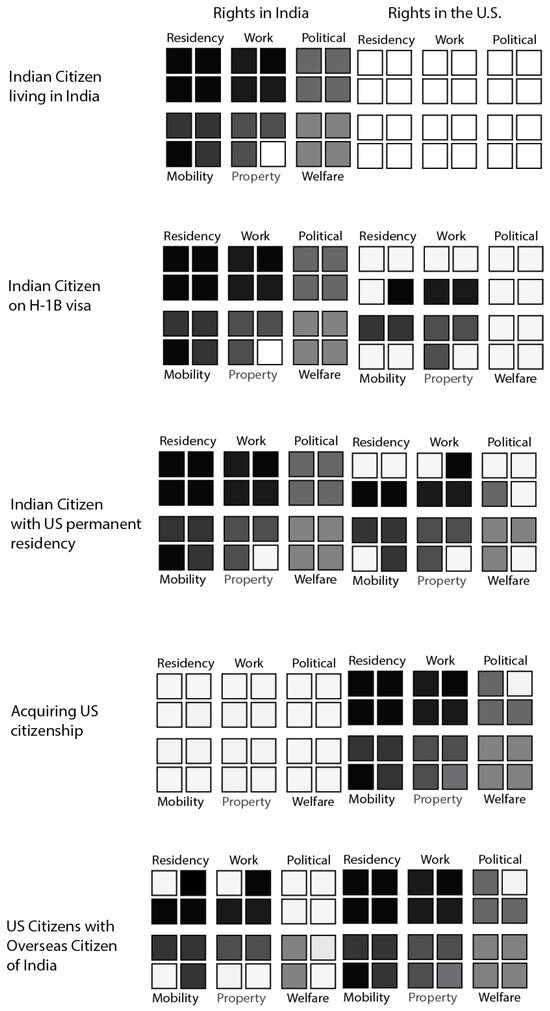

Let us illustrate the modularity of citizenship with a hypothetical case: an Indian citizen residing in the United States on a non-immigrant H-1B visa. As a temporary resident, this individual enjoys multiple rights, many of which overlap with those of citizens. To simplify, consider just one such right—the right to work. This is not a singular or uniform entitlement but a highly differentiated set of permissions. For the H-1B visa holder, these rights are narrowly defined in both spatial and temporal terms, unlike those granted to a resident alien. The H-1B visa does not confer the freedom to work “anywhere” or “anytime”; it is tied to a specific employer, role, and period. The right to work can be activated only on locations listed on the Labor Condition Application3 accompanying the visa. It is also temporally circumscribed by a maximum validity period of six years. Unlike a naturalized citizen, the H-1B holder cannot automatically extend this right to their spouse. The spouse must apply for a dependent H-4 visa, which permits return and re-entry for the same duration as the H-1B but does not confer the right to work4. However, on institutional sponsorship for permanent residency, the H-1B visa holder’s spouse also becomes eligible for permanent residency, aligning their basket of rights more closely with that of natural-born or naturalized citizens—albeit with some lingering restrictions. For instance, to maintain lawful permanent resident status, one must not remain outside the United States for more than six consecutive months. Yet beyond this, most spatial and temporal restrictions on the right to work are lifted. In practical terms, the resident alien can function much like a citizen, lacking only the right to vote or hold public office. Meanwhile, this immigrant, still being an Indian citizen, can access all political and economic rights in India during their stay in the United States.

If the individual above chooses to become a U.S. citizen, the configuration of rights shifts. They gain U.S. political rights—such as voting and eligibility for public office—but must relinquish Indian citizenship, and with it, most political and economic rights in India. However, by applying for Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI), they can recover many of the economic and mobility rights previously held, including the ability to buy and sell property, enroll in Indian educational institutions at local rates, and travel to and from India without a visa. Yet this recovery is partial. OCI status does not restore political rights in India—such as voting, holding public office, or government employment—highlighting the selective modulation of rights across jurisdictions. The trade-off illustrates how modern citizenship operates as a dynamic configuration of rights, activated and deactivated depending on legal status and transnational position.

I illustrate this modularity of rights—and the resulting forms of citizenship—across three legal contexts: H-1B, permanent residence, and full citizenship. In Figure 2, white squares represent the absence of rights, black squares a full set of rights, and grey squares partial rights. The figure as a whole offers a visual sense of how the strength of rights, and thus of citizenship, is distributed across categories and statuses. Because it is a stylized figure, it should not be interpreted mathematically by counting squares (though citizenship could be quantified in that way, it would make for a different paper). While stylized, this approach can be applied to all forms of citizenship, as the theory of modular citizenship seeks to account for every status.

Figure 2.

Citizenship as a basket of rights.

In short, the framework of the modular basket of rights captures the growing variation within global citizenship regimes, marking a shift away from the traditional mold of sovereign nationality toward a more modulated system of finely parsed rights—rights that can be bundled, unbundled, and reassembled across different contexts. I conceive of modular citizenship as a fork in the evolutionary path of citizenship: a move away from exclusive birthright entitlements toward privileges increasingly shaped by diasporic connections, wealth, educational credentials, inter-state agreements, and, still, birthright. More precisely, the transformation lies in the demotion of birthright—from the sole organizing principle of citizenship to just one among several emerging criteria for inclusion.

The theory of modular citizenship resolves the debate between those who argue that a shift from birth-based to right-based membership has already taken place (postnationalism) or ought to take place (cosmopolitanism) and those who argue that birth-based membership in a sovereign polity remains the primary mode of citizenship. With an ability to include birthright, jus sanguinis and jus soli, as components of modularity, modular citizenship integrates both sides of the debate within a single analytical framework. It accommodates the full spectrum of citizenship regimes—from the most liberal to the most restrictive. For instance, in Bahrain, Oman, Qatar, and the UAE, where foreigners constitute the majority of the population, birthright remains the central modulating parameter, so much so that non-native-born families living for multiple generations remain “impossible citizens,” lacking important sets of rights despite their significant impact on the region (Vora 2013). Modular citizenship thus provides the conceptual tools to understand both inclusive and exclusionary practices, mapping the differential allocation of rights across diverse political landscapes.

4. Modular Citizenship: The Statecraft of Access and Control

To develop the thesis of modular citizenship from within the ongoing transformation of citizenship practices, it is important to identify the handiwork of the state itself in weakening the territorial fixity of citizenship. Let us discuss the following key developments responsible for citizenship modulation: (1) policy shifts toward diasporic citizenship; (2) sale of citizenship rights to foreign nationals; and (3) the quantification of credentials for citizenship eligibility.

4.1. Diasporic Citizenship Rights

With large-scale migrations and the diasporic diffusion of populations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the transnational extension of rights to diasporas by an increasing number of states marks a break from territorially rooted citizenship formats and fixed baskets of rights. In some cases, new forms of citizenship have become accessible at a distance, particularly with the advent of information and communication technologies—extending economic rights and, in certain instances, even voting rights.

Indeed, one of the forces behind the growing acceptance of non-exclusive citizenship in many countries is the presence of an increasingly large diaspora living abroad. Diasporic citizenship offers a two-way solution: it allows members of the diaspora to reconnect—psychologically and socially—with their homeland by regaining citizenship rights, and it enables the state to engage its diaspora in local development efforts. Although diasporic citizenship is rooted in the principle of ancestry (jus sanguinis), it differs in a crucial way: these rights are extended to individuals no longer residing in the country, but living across other national territories.

What has accelerated this trend in recent years is the political economy of remittances, coupled with longstanding demands from former citizens abroad—particularly elite émigrés. A list of countries currently recognizing some form of diasporic citizenship is provided in Appendix A.4. The sheer number of countries (n = 131) adopting such policies highlights the bureaucratic, economic, and political appeal of enabling their diaspora to remain actively engaged in the affairs of their countries of origin.

Let us illustrate this dynamic through the case of India, a case I studied in depth. In 2000, the Government of India appointed a High Level Committee (HLC) to build “a mutually beneficial relationship” with the Indian diaspora, as outlined in its 2001 report. While the report cited the diaspora’s long-standing demand for dual nationality, its emphasis quickly shifted to the economic value of remittances—highlighting this as a key motive for offering overseas citizenship:

India has ambitious plans to increase investments in India from foreign sources by some USD 6 billion per year. An estimated 20 million Indians live outside of India. The law states that non-citizens cannot own property, among other things. So affluent ex-pats were unable to build hospitals, schools or corporations in India to help improve conditions and the economy…India will be allowing dual citizenship for those of its people living in the United States and several other affluent countries, in an effort to spur investments in Indian markets and put to rest a longstanding irritation among ethnic Indians.5

Evidently, the state’s perception of the overseas citizens’ demand for transnational rights went beyond diasporic solidarity to include potential capital flows that could address some of India’s welfare concerns.

In 2002 the Indian government started a Person of Indian Origin (PIO) card scheme for diasporic Indians and their foreign spouses living in select countries. This was followed in 2005 by the Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) scheme, which offered broader rights but excluded foreign spouses. In 2015, the two were merged, extending OCI benefits to foreign spouses and dropping the ancestry requirement for them. In effect, while ancestry still mattered, the new statecraft redefined its norms to suit evolving goals.

The question of why the Indian government did not allow overseas citizenship for five decades (1950–2005) is difficult to answer but neo-institutionalist insights may be of help here: the move toward diasporic citizenship scripts may be part of a world cultural development that the states have begun adopting at a greater number in recent decades. The script of diasporic citizenship is being proposed for African countries as well. A World Bank report estimated that migrant remittances to Africa exceeded USD 40 billion in 2010 but most of the African diaspora’s savings of USD 53 billion annually is invested outside Africa. These savings, it is suggested, could be mobilized for Africa via instruments such as bonds (Ratha et al. 2011). Appendix A.1 mentions the top ten countries with the highest inflow of remittances. All of them, except China, offer some form of diasporic citizenship.

While the diasporic principle of modulation may have implicit monetary and developmental concerns, there is an emerging trend to explicitly tap the purse of the non-diasporic wealthy global class through the sale of rights.

4.2. Sale of Citizenship Rights

The monetization of citizenship has drawn criticism for “undermining the very concept of political membership” (Shachar and Hirschl 2014, p. 248). Indeed, it does undermine the idea of membership as money becomes a novel modulating principle of citizenship rights allowing different states to establish different rates for citizenship rights. The rise of the transnational global elite (Robinson 2011; Sklair 2012) and the advent of investment-based citizenship available to wealthy foreign nationals (Shachar and Hirschl 2014) open up another front against the fixed basket of citizenship rights. An increasing number of countries offer modulated citizenship rights to individuals ready to pay for it.

The basket of rights gained through investment varies from country to country. States increasingly offer tiered access to rights based on payment—ranging from full citizenship to investor visas. In all these cases, money modulates access to a rights package whose price structure follows an algorithmic if-this–then-that logic. Though labeled differently—citizenship, residency, visa status—they are functionally produced by the same algorithmic logic underpinning modular citizenship.

4.2.1. Citizenship Function

Consider the classic case of Saint Kitts and Nevis, a small Caribbean nation, which was the innovator in offering citizenship rights back in 1983. Its algorithmic, if-this–then-that routine, can be captured in the following manner:

- if donation to the Sustainable Island State Contribution (SISC) ≥ USD 250,000:

- or, if investment in resort hotel shares ≥ USD 400,000 and held for ≥ 7 years:

- or, if investment in condos or private homes ≥ USD 800,000 and held for ≥ 7 years:

- return a full set of mobility, residency, work, voting, property, and welfare rights.

4.2.2. Residency Function

Now contrast this with the United States’ EB-5 investor program, an example of permanent residency by investment that has long operated on a similar algorithmic format:

- if investment in targeted employment areas ≥ USD 800,000:

- or if investment ≥ USD 1,050,000:

- return a set of mobility, residency, work, property, and welfare rights.

4.2.3. Visa Function

Lastly, let us look at the United Kingdom’s 40-month residency-by-investment visa program:

- if investment in UK share capital ≥ GBP 2 million and held for ≥ 5 years:

- or if investment in UK loan capital ≥ GBP 2 million and held for ≥ 5 years:

- return a set of mobility, residency, work, property, and welfare rights.

The transactional nature of class-based, investment-seeking state practices becomes clearer with an example like Bangladesh, which has baked into its laws the revocation of citizenship if the naturalized citizen-by-investment in Bangladesh removes the investment from the country. Citizenship in such cases seems to lose its permanent immutable character and appears more like a set of rights purchased at a price for a period of time (see Appendix A.2 for investment-based citizenships).

Vying with global diaspora and global investments is the modulating principle of global talent in the emerging statecraft of citizenship. Adding to the criteria of money and ethnic ties, the measure of merit further challenges the exclusivity of the birthright model.

4.3. Quantified Credentials for Immigration Rights

The emergence of a “points system” in immigration policies of many countries marks an additional basis for granting citizenship rights. In the case of Canada and Australia, in particular, one notices, selection criteria are heavily weighted in favor of skills, work experience, and educational qualifications, introducing new indices of risk in immigration (Walsh 2008, 2011). While national origin, race and ethnicity played dominant roles in immigrant selection in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, their scope has dramatically narrowed in liberal democracies (Joppke 2005). The comprehensive immigration policy in the European Union includes only three criteria and none of them pertain to ethnicity: prosperity—skills, economic need, and integration; solidarity—coordination inside and outside the EU; and security—border control. The growing importance of skills points to a structural change in liberal immigration policies from strong identities along fixed ethnic lines to pliable identities based on performance. In step with the world society perspective (Meyer et al. 1997; Meyer and Bromley 2013), therefore, I witness a gradual move in immigration policies from cultural nationalism to cultural rationalization.

Even as neonationalism threatens to unravel liberal societies, recent racially motivated discourses of denaturalization in the United States ironically seek to undo the constitutionally protected birthright principle of jus soli available to the children of undocumented parents while proposing to install a merit-based system.

Similar to the investment-generated rights package, the code of credentials modulates the outcome of immigrant eligibility and possibility of gaining rights under this development. Take, for example, Canada’s Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS), which assesses and scores an applicant’s profile and ranks it in the Express Entry pool by painstakingly assigning points and weights to credentials pertaining to education, language proficiency, work experience, and skill transferability. This mechanism is illustrated algorithmically in the pseudocode provided for reference in Appendix A.5. If an applicant scores a sufficient number of points, they become eligible for certain modules of rights in Canada, adding to their global basket of rights. The Canadian immigration and integration policy model has inspired the reform process in many countries, including Norway, Sweden and Denmark (Ugland 2018), as they look to fine-tune their machinery for screening outsiders. Appendix A.3 captures the implementation of merit-based citizenship rights enabling migratory flows.

5. Implications for Future Research

The emerging modularity of citizenship must not be seen as a sign of progress; its flexibility enables targeted discrimination and exclusion. Indeed, by conceptualizing rights as a measure or currency of citizenship, modular citizenship opens the door for future research into how rights are unevenly distributed—and how this shapes inequalities in citizenship.

The basket of rights framework clarifies the gap between formal and substantive citizenship. Traditional models assume equality through legal abstraction—individuals are rendered equal only through abstraction, and only for the limited purposes of political membership and legal standing. As Marx ([1844] 1996) observed, equality before the law functions by abstracting individuals from the power relations in which they are embedded, producing a disconnect between what Bauböck (1994) calls nominal and substantive citizenship. The modular framework of citizenship moves away from the model of formal equality through membership and instead emphasizes actually available rights. It allows us to ask, for example, whether a nonimmigrant software professional in the U.S. on an H-1B visa enjoys more substantive citizenship rights than a disenfranchised class of formal citizens. This framework also opens the door for future research to compute global citizenship by analyzing one’s global basket of rights—gained through diasporic networks, investments, or skill-based qualifications.

In essence, modular citizenship reveals three far-reaching implications: First, everyone is a citizen more or less—everyone holds some level of citizenship, the extent of which varies. Visa holders, permanent residents, and native-born citizens can be viewed as points along this continuum. Second, citizenship is modular, made up of interchangeable rights that can be added, removed, or adjusted based on legal context. Third, this modularity does not weaken state power. Rather, it enhances the state’s flexibility to manage rights and reinforces its authority to define eligibility for work, residency, and welfare through evolving criteria.

6. Conclusions

Citizenship has not shifted from birthright to human rights; rather, birthright has become one among several modulators of access. While its empirical weight remains, its theoretical primacy has diminished. Behind the apparent loosening of citizenship norms based on national exclusivity, I identify the evolution of citizenship toward modularity. The combination of historic forces such as large diasporas, globally mobile class formation, skilled migration, and bilateral treaties allows us to conceptualize citizenship in terms not of membership or the fixed basket of rights available within a country but of variable baskets within and across national jurisdictions.

This framework allows for the continuing differentiation of rights and acknowledges the inequality inherent in the varying bundles of rights available to different classes of individuals. I attempt to capture the complexity of this transformation through the concept of a fluctuating basket of rights across highly differentiated citizenship forms: non-resident citizens, permanent residents, non-immigrants, immigrants, guest workers, tourists, citizen felons, and others. Thus, I argue, it is more productive to recast citizenship as a regime of differential inclusions, shaped by varying interests and determined by access to different bundles of rights—contingent on factors such as country of origin and destination, ethnicity, legal status, duration of stay, family connections, financial resources, education, and inter-state agreements.

Modular citizenship proposes that citizenship be understood as an assemblage of substantive, actually available rights. This reframing enables us to account for inequalities of citizenship—where it is the rights basket, rather than formal membership, that can be evaluated. Citizenship, in this view, becomes something one can possess to varying degrees, depending on access to rights and resources. It emerges as a variable basket of rights, differing in quality, quantity, and complexity.

While the enforcement of rights—whether successful or not—remains within the domain of the state, the concept of citizenship itself is no longer confined to it. It becomes possible to conceive of certain citizens—such as felons—as possessing fewer rights than some noncitizens, and therefore enjoying less citizenship. In this model, the state or a state-backed institution—armed with the legitimate means of coercion—continues to serve as the ultimate guarantor, enforcer, and modulator of the available portfolio of citizenship rights within a regime of cross-cutting affiliations.

Funding

This research was supported by a nine-month fellowship from the Berggruen Institute in Los Angeles (2020–2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data collected by research assistant, Diana Illencik, is presented in the Appendix A.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Berggruen Institute in Los Angeles (USA) for its generous fellowship support during the conceptualization and writing of this paper. I am also grateful to the Center for 21st Century at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (USA) and to members of the audience at the American Sociological Association Annual Meetings for their immensely helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Special thanks go to my research assistant, Diana Illencik, for her excellent work in collecting data for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OCI | Overseas Citizenship of India |

| HLC | High Level Committee |

| LCA | Labor Condition Application |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Top Ten Countries Receiving the Highest Amounts of Remittances: 2007–2017

| Remittances (USD Million) | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

| India | 49,204 | 53,480 | 62,499 | 68,821 | 69,970 | 70,389 | 68,910 | 62,744 | 68,968 |

| China | 41,600 | 52,460 | 61,576 | 57,987 | 59,491 | 62,332 | 63,938 | 61,000 | 63,860 |

| Philippines | 19,960 | 21,557 | 23,054 | 24,610 | 26,717 | 28,691 | 29,799 | 31,145 | 32,808 |

| Mexico | 22,076 | 22,080 | 23,446 | 23,209 | 23,189 | 24,802 | 26,233 | 28,691 | 30,600 |

| France | 19,649 | 19,903 | 22,927 | 22,674 | 24,413 | 25,351 | 23,766 | 24,373 | 25,372 |

| Nigeria | 18,368 | 19,745 | 20,617 | 20,543 | 20,797 | 20,829 | 21,060 | 19,636 | 21,967 |

| Egypt | 7150 | 12,453 | 14,324 | 19,236 | 17,833 | 19,570 | 18,325 | 16,590 | 19,983 |

| Pakistan | 8717 | 9690 | 12,263 | 14,007 | 14,629 | 17,244 | 19,306 | 19,761 | 19,665 |

| Germany | 12,333 | 12,792 | 15,328 | 14,643 | 16,398 | 17,365 | 16,133 | 16,683 | 16,833 |

| Vietnam | 6020 | 8260 | 8600 | 10,000 | 11,000 | 12,000 | 13,200 | 11,880 | 13,781 |

| Source: World Bank staff calculation based on data from IMF Balance of Payments Statistics database and data releases from central banks, national statistical agencies, and World Bank country desks. (http://www.worldbank.org/migration, accessed on 23 January 2020). | |||||||||

Appendix A.2. Investment-Based Programs of Immigration and Citizenship

| Country Name | Start Year | Minimum Investment (USD) | Program |

| Andorra | 2012 | 53,940/434,880 | Residence without gainful activity |

| Anguilla | 2018 | 150 k/750 k | Anguilla Residency by Investment Programme (ARBI) |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 2013 | 100 k/400 k/1.5 m | Citizenship by Investment Program |

| Argentina | 2017 | 24,000 | Investor visa (Inversionista) |

| Australia | 2012 | 982,800/3.2 m/9.8 m | Business Innovation and Investment program |

| Austria | N/A | 3.3–1.1 m | No specific program (no dual nationality) |

| Bahamas | N/A | 500,000 | Immigrant Investor Program |

| Bangladesh | 500,000 | Citizenship | |

| Belgium | N/A | 380,940–544,200 | Investor Visa |

| Brazil | 2012 | 224,700 | Investor Visa for Brazil |

| Bulgaria | 2009 | 556,400 | Investor Program for Residence and Citizenship |

| Canada (Quebec) | Suspended 2019 | 262,815–901,080 | Quebec Immigrant Investor Program |

| Chile | N/A | N/A | Investor/Entrepreneur/Trader Visa (Inversionista/Empresario/Comerciante) |

| China (Hong Kong) | Suspended in 2015 | 1,283,000 | Capital Investment Entrant Scheme |

| Colombia | N/A | 26,984/94,445/175,399 (2019) | M-6/M-10 Visa (migrant visa)/R Visa (resident visa) |

| Costa Rica | N/A | 100,000/200,000 | Investor visa (Inversionista) |

| Cyprus | 2013 | 2,340,060 | Cyprus Citizenship by Investment Program |

| Dominica | 1993 | 100,000/200,000 | Economic Diversification Fund (EDF) |

| Dominican Republic | N/A | 200,000 | Residency by Investment program |

| Ecuador | 2013 | 25,000/30,000 | Visa 9-II/9-III |

| Estonia | N/A | 1,088,400 | Temporary Residence Visa |

| France | N/A | 10,884,000 | French Residence Permit Program |

| Georgia | 2019 | 300,000 | Investment Residence Permit |

| Germany | N/A | 269,700 | Three-year residence permit |

| Greece | 2013 | 272,100 | Law 4146/2013 |

| Grenada | 2013 | 50,000/350,000 | Citizenship by Investment Programme |

| Hungary | 326,520 | Residency Bond Prog; Suspended in 2017 | |

| India | 2016 | 1,372,000/3,430,000 | Make in India Programme |

| Iran | 2019 | 250,000 | Temporary Residency Permit |

| Ireland | 2012 | 1,088,400 | Immigrant Investor Programme |

| Italy | 2017 | 544,200/1.1 m/2.2 m | Investor Visa for Italy |

| Japan | N/A | 48,800 | Business Manager Visa |

| Latvia | 2010 | 272,100 (544,200) | Residency Visa |

| Lithuania | 2014 | 30,464 | Investment Visa |

| Luxembourg | 2017 | 544,200/3,265,200/21,768,000 | Investor Residence permit |

| Malaysia | 2002 | 35,475/70,950 | MM2 H |

| Malta | 2014 | 1,251,660 | Malta Individual Investor Programme |

| Mexico | N/A | 144,293.84 | Temporary Residence Visa |

| Moldova | 2018 | 108,840/272,100 | Moldova Citizenship-by-Investment (MCBI) program |

| Monaco | N/A | 544,200 | Residence by Investment |

| Montenegro | 2019 | 380,940 | Investment Immigration Program |

| Netherlands | 2013 | 1,360,500 | Golden Visa |

| New Zealand | N/A | 944,250–6,295,000 | Investor 1 and Investor 2 Category |

| Nicaragua | N/A | 30,000 | Investor Visa |

| Panama | N/A | 5000/80,000/160,000/300,000 | Friendly Nations Visa/Reforestation Investment Visa/Business Investor Visa/Self Economic Solvency Visa |

| Paraguay | 2013 | 3742.12/7620/22,860 | Sistema Unificado de Apertura y Cierre de Empresas |

| Peru | 2017 | 142,500 | Investor visa (Inversionista) |

| Philippines | 2006 | 75,000 | Special Investors Residence Visa |

| Portugal | 2012 | 544,200 | Residency Visa |

| Singapore | 2009 | 1,789,250 | Global Investor Programme |

| South Africa | 2014 | 328,700 | Business Visa |

| South Korea | N/A | 82,300 | D-8 Visa |

| Spain | 2013 | 544,200/1,088,400/2,176,800 | Residency Visa |

| St Kitts | 1984 | 150,000–200,000/400,000 | Citizenship by Investment Program |

| St Lucia | 2016 | 100,000/300,000 | Citizenship by Investment Program |

| Switzerland | N/A | 511,600 | Residency by Investment |

| Taiwan | N/A | 200,000 | Resident visa for investment |

| Thailand | 2014 | 313,900 | Investor visa |

| Turkey | 2016 | 250,000/500,000 | Citizenship by Investment Programme |

| United Arab Emirates | N/A | 272,200 | Property Investor Visa/Six-Month Residency Visa |

| United Kingdom | 2019 | 64,820 | UK Innovator Visa and Start-Up Visa (Change from the 1994 Tier 1 investment visa) |

| United States | 1990 | 1.8 million | E2/EB-5 (USD 500,000/USD 900,000 for Targeted Employment Area) |

| Vanuatu | 2017 | 130,000 | Citizenship by Investment Program |

| Source: Data collected from multiple sources by Diana Illencik, the author’s research assistant in 2020–2021. | |||

Appendix A.3. Merit-Based Programs

| Country | Start Date | Program | Validity |

| Albania | N/A | AL Blue Card; AL-C Blue Card | 2-year period (may be renewed for an additional 3-year period) |

| Australia | 1972, 1989 | Skilled Independent Visa (Subclass 189); Skilled Nominated Visa (Subclass 190); Skilled Regional (Provisional) visa (subclass 489); Skilled Work Regional (Provisional) visa (subclass 491) | N/A |

| Austria | 2011 | Red–White–Red Card for Very Highly Qualified Workers, Skilled Workers in Shortage Occupations, Other Key Workers, Graduates of Austrian Universities and Colleges of Higher Education, Self-employed Key Workers, Start-up Founders | Issued for a period of 24 months for fixed-term settlement and employment |

| 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) | |

| Belgium | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 13 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Bulgaria | 2011 | EU Blue Card | 12 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Canada | 1967 | Federal Skilled Worker | N/A |

| Croatia | 2013 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Cyprus | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 12 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Czech Republic | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Denmark | Greencard scheme repealed in 2016; other merit options available | Pay Limit scheme; Positive List; Researcher; Employed PhD; Special individual qualifications; ESS Scheme; Authorization as doctor, dentist, or nurse | N/A |

| Ecuador | N/A | 9-V Professional Visa | N/A |

| Estonia | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 27 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Finland | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| France | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 48 months |

| Germany | 2018 | Skilled Immigration Act | N/A |

| 2009 | EU Blue Card | 48 months | |

| Greece | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Hong Kong (China) | 2006 | Quality Migrant Admission Scheme | N/A |

| Hungary | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 48 months |

| Ireland | N/A | Employment Visa (Atypical Working Scheme) | Short-Term Visa |

| Italy | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Japan | 2012 | Highly Skilled Foreign Professional Visa; sub-categories—advanced academic research activities, advanced specialized/technical activities, advanced business management activities | N/A |

| Latvia | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 60 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Lithuania | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 36 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Luxembourg | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Malaysia | N/A | Permanent Residency Point Based System | N/A |

| N/A | Permanent Residency for Experts/Professionals | N/A | |

| Malta | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 12 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Netherlands | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 48 months maximum (based on work contract duration) |

| New Zealand | 1991 | Skilled Migrant Visa | N/A |

| Poland | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Portugal | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 12 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Romania | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Seychelles | N/A | Priority Workers | Citizenship |

| Singapore | N/A | Professionals/Technical Personnel and Skilled Worker scheme (“PTS scheme”) | Permanent Residency |

| Slovakia | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 48 months (unless work contract lasts shorter) |

| Slovenia | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| South Korea | 2010 | F-2-7 Visa | N/A |

| Spain | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 12 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Sweden | 2009 | EU Blue Card | 24 months (unless work contract lasts longer) |

| Turkmenistan | N/A | Residence Permit | Residence Permit |

| United Kingdom | In Progress (1 January 2021) | Global Talent Visa | N/A |

| United States | 1990 | H-1B program | Maximum 6 years |

| Source: Data collected from multiple sources by Diana Illencik, the author’s research assistant in 2020–2021. | |||

Appendix A.4. Multiple Citizenship

Some countries allow their diaspora to retain some or all of citizenship rights after moving abroad or reobtain citizenship due to legal changes in national citizenship codes. These changes can include legal acceptance of individuals simultaneously holding dual or multiple citizenships in various countries and/or the reoffering of modified citizenship statuses based on individual needs (e.g., the Indian OCI system). Countries that only offer dual citizenship statuses to minors until they reach legal adulthood are excluded from this list (n = 131):

Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, the Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belarus, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cambodia, Canada, the Central African Republic, Chad, Chile, Colombia, Comoros, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Fiji, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Grenada, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, India, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Jordan, Kenya, Republic of Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lebanon, Libya, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malawi, Maldives, Mali, Malta, the Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Mexico, the Republic of Moldova, Montenegro, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Nauru, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Niger, Nigeria, Niue, Norway, Pakistan, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, the Philippines, Portugal, Romania, the Russian Federation, Rwanda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, South Sudan, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Sweden, Switzerland, Syria, Tajikistan, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, the United Kingdom, United States, Uruguay, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

Source: Data collected from multiple sources by Diana Illencik, the author’s research assistant in 2020–2021.

Appendix A.5. Algorithmic Recipe for Canada’s Federal Skilled Worker Program (Express Entry)

This pseudocode aims to provide a structured approach to calculate the total score based on various factors such as language skills, education, work experience, age, arranged employment, and adaptability. The applicant’s eligibility is determined based on whether their total score meets or exceeds the threshold of 67 points.

Initialize total score to 0

- # Language skills

If first official_language_level ≥ CLB 9:

- Add 24 points to total_score

Else if first_official_language_level = CLB 8:

- Add 20 points to total_score

Else if first_official_language_level = CLB 7:

- Add 16 points to total_score

Else:

- Set total_score to 0 and exit (not eligible to apply)

If second_official_language_level ≥ CLB 5:

- Add 4 points to total_score

- # Education

If education_level meets Canadian standards (as per ECA report):

- Add up to 25 points to total_score based on the level of education

- # Work experience

If work_experience_years ≥ 6:

- Add 15 points to total_score

Else if work_experience_years is between 4 and 5:

- Add 13 points to total_score

Else if work_experience_years is between 2 and 3:

- Add 11 points to total_score

Else if work_experience_years = 1:

- Add 9 points to total_score

- # Age

If age is between 18 and 35:

- Add 12 points to total_score

Else if age is between 36 and 47:

- Subtract 1 point from 12 for each year over 35 and add to total_score

Else:

- Add 0 points to total_score

Notes

| 1 | Although this paper is a theoretical exegesis of the growing modularity of citizenship, it benefits from (1) large-scale, qualitative data on citizenship laws of more than a hundred countries collected for a larger project, and (2) an in-depth ethnographic study of a single case—India’s introduction of dual citizenship through field research in New Delhi. |

| 2 | Undocumented immigrants in the United States pay on average an estimated 8 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes while the top 1 percent of taxpayers pay an average nationwide effective tax rate of just 5.4 percent (Gee et al. 2016). The Internal Revenue Service estimates that undocumented immigrants, using the Individual Taxpayer Identification Number, or ITIN, pay over USD 9 billion in withheld payroll taxes annually. Undocumented immigrants help make the Social Security system more solvent, as they pay into the system but are ineligible to collect benefits upon retiring (Hallman 2018). |

| 3 | The Labor Condition Application, or LCA, is a prerequisite to H-1B approval. The LCA, U.S. Department of Labor Form-9035, contains basic information about the proposed H-1B employment such as rate of pay, period of employment, and work location. It also contains four standard attestations or promises that the employer must make: (a) It is paying (and will continue to pay) the H-1B employee wages which are at least the actual wages paid to others with similar experience and qualifications for the specific job, or the prevailing wage for the occupation in the area of employment is based on the best information available. (b) It will provide working conditions for the H-1B employee that will not adversely affect the working conditions of workers similarly employed in the area. Working conditions commonly refer to matters including hours, shifts, vacation periods, and fringe benefits. (c) There is no strike or labor dispute at the place of employment. (d) It has provided notice of this filing to the bargaining representative (if any), or if there is no such bargaining representative, it has posted notice of filing in at least two conspicuous locations at the place of employment for a period of 10 business days. |

| 4 | In 2015, the Obama Administration passed a rule that allowed some H-4 visa holders to work if their partner, the H-1B holder, was sufficiently far along in the green card process or had been residing in the US for more than six years. This rule is currently being debated in the Trump administration. |

| 5 | According to the International Migration Report 2019, India was the leading country of origin of international migrants, with 17.5 million persons living abroad. Migrants from Mexico constituted the second largest “diaspora” (11.8 million), followed by China (10.7 million), the Russian Federation (10.5 million) and the Syrian Arab Republic (8.2 million) (UN 2019). |

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities. New York: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2006. Fear of Small Numbers. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Archibugi, Daniele. 2004. Cosmopolitan Democracy and Its Critics: A Review. European Journal of International Relations 10: 437–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augé, Marc. 1995. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. New York: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1964. The Poetics of Space. New York: Orion Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauböck, Rainer. 1994. Transnational Citizenship: Membership and Rights in International Migration. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bauböck, Rainer. 2003. Towards a Political Theory of Migrant Transnationalism. International Migration Review 37: 700–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetham, David. 1999. Democracy and Human Rights. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benhabib, Seyla. 2008. Another Cosmopolitanism. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Andrea. 1999. Immunity Versus Human Rights: The Pinochet Case. European Journal of International Law 10: 237–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosniak, Linda. 2008. The Citizen and the Alien: Dilemmas of Contemporary Membership. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Garrett W., and David Held, eds. 2010. The Cosmopolitanism Reader. Malden: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2010. Introduction to Immigration and the Politics of Citizenship in Europe and North America. In Selected Studies in International Migration and Immigrant. Edited by Marco Martiniello and Jan Rath. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, Craig. 1993. Nationalism and Ethnicity. Annual Review of Sociology 19: 211–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, Joseph A., and Jim Falk. 1992. The End of Sovereignty: The Politics of a Shrinking and Fragmenting World. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Carens, Joseph H. 1987. Aliens and Citizens: The Case for Open Borders. The Review of Politics 49: 251–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, Edward S. 1993. Getting Back into Place: Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place-World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, Steven, and Keith H. Basso, eds. 1996. Senses of Place. Santa Fe: SAR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, Lisa C., Matthew Gardner, and Meg Wiehe. 2016. Undocumented Immigrants’ State & Local Tax Contributions. Washington, DC: The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Gieryn, Thomas F. 2000. A Space for Place in Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 463–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1998. The European Nation-State: On the Past and Future of Sovereignty and Citizenship. Public Culture 10: 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2010. A Political Constitution for the Pluralist World Society. In The Cosmopolitanism Reader. Edited by Garrett Wallace Brown and David Held. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 267–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman, Hunter. 2018. How do Undocumented Immigrants Pay Federal Taxes? An Explainer. Bipartisan Policy Center. March 28. Available online: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/how-do-undocumented-immigrants-pay-federal-taxes-an-explainer (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Hegel, Georg W. F. 2015. The Philosophy of Right. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971. Building Dwelling Thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought. New York: Harper & Row, pp. 145–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, David. 1996. Rights Across Borders: Immigration and the Decline of Citizenship. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Joppke, Christian. 2001. The legal-domestic sources of immigrant rights: The United States, Germany, and the European Union. Comparative Political Studies 34: 339–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppke, Christian. 2005. Selecting by Origin: Ethnic Migration in the Liberal State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 1970. Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. New York: Cambridge University Press, First publish 1795. [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre, Michel S. 1998. Diasporic Citizenship: Haitian Americans in Transnational America. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- League of Nations. 1930. Convention on Certain Questions Relating to the Conflict of Nationality Laws. The Hague: League of Nations, Treaty Series 179: 4137. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/legal/agreements/lon/1930/en/17955 (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1969. The Elementary Structures of Kinship. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, Niklas. 2012. Theory of Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, Thomas Humphrey. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class. Concord: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl. 1996. On the Jewish Question. In The Marx-Engels Reader edited by Robert Tucker. New York: W. W. Norton &. Company, p. 31. First published 1844. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, John W. 2010. World Society, Institutional Theories, and the Actor. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John W., and Patricia Bromley. 2013. The Worldwide Expandion of “Organization”. Sociological Theory 31: 366–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, John W., John Boli, George M. Thomas, and Francisco O. Ramirez. 1997. World Society and the Nation-State. American Journal of Sociology 103: 144–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Immigration Forum. 2016. New Americans in the U.S. Armed Forces Fact Sheet. November 22. Available online: https://immigrationforum.org/ (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Nisbet, Robert A. 1966. The Sociological Tradition. New York: Basic Book. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, Aihwa. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro, Luis E. Guarnizo, and Patricia Landolt. 1999. The Study of Transnationalism: Pitfalls and Promise of an Emergent Research Field. Ethnic and Racial Studies 22: 217–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe-Brown, Alfred R., and Daryll Forde. 1950. African Systems of Kinship and Marriage. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ratha, Dilip, Sanket Mohaptra, Caglar Ozden, Sonia Plaza, William Shaw, and Abebe Shimeles. 2011. Leveraging Migration for Africa: Remittances, Skills, and Investments. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, William I. 2011. Global Capitalism Theory and the Emergence of Transnational Elites. Critical Sociology 38: 349–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar, Ayelet. 2009. The Birthright Lottery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shachar, Ayelet, and Ran Hirschl. 2014. On Citizenship, States, and Markets. Journal of Political Philosophy 22: 231–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, Georg. 1950. The Metropolis and Mental Life. In The Sociology of Georg Zimmel. New York: Free Press, pp. 409–24. First published 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Sklair, Leslie. 2012. Transnational Capitalist Class. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Soysal, Yasemin. 1994. Limits of Citizenship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ugland, Trygve. 2018. Policy Learning from Canada: Reforming Scandinavian Immigration and Integration Policies. Buffalo: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 2019. International Migration 2019: Report. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- US Citizenship and Immigration Services. 2020. USCIS Facilities Dedicated to the Memory of Immigrant Medal of Honor Recipients. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/about-us/find-uscis-office/uscis-facilities-dedicated-memory-immigrant-medal-honor-recipients (accessed on 3 January 2020).

- Vora, Neha. 2013. Impossible Citizens: Dubai’s Indian Diaspora. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, James. 2008. Navigating Globalization: Immigration Policy in Canada and Australia, 1945–2007. Sociological Forum 23: 786–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, James. 2011. Quantifying citizens: Neoliberal restructuring and immigrant selection in Canada and Australia. Citizenship Studies 6–7: 861–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).