Abstract

The pattern of labour underutilisation is complex and multifaceted, but research has been focused on unemployment. To explore socio-economic demographics of other forms of labour underutilisation, this study investigates the concept of ‘hidden workers’ using the latest data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) study. Hidden workers are composed of three categories, namely those who are unemployed but actively seeking employment; working part-time but willing and able to work full-time; and not working but are willing and able to work under the right conditions. Analysis of HILDA data from 2022 reveals (i) a significant discrepancy in the incidence of unemployed and hidden workers across various socio-economic factors, and (ii) a pronounced age and gender differences among hidden workers, which is not easily discernible from standard unemployment descriptive statistics. Effective labour market policy depends on accurately identifying the different types of hidden workers and their social determinants. This study offers valuable insights to support more inclusive policies for hidden workers, who are often overlooked.

1. Introduction

Since the 1970s, it has been highlighted that some categories of unemployment are not captured in official statistics (Baum and Mitchell 2010; McKee-Ryan and Harvey 2011; Baert 2021). Even though the research landscape on labour underutilisation is dominated by the study of unemployment (Lee and Kang 2024), interest has increased in examining various forms of labour underutilisation, i.e., the long-term unemployed (Rudman and Aldrich 2017, 2021), discouraged workers (Heslin et al. 2012), and the underemployed (Li et al. 2015; Kler et al. 2018). Studies illustrate a systemic deprivation in all aspects of health and well-being among these groups (McKee-Ryan and Harvey 2011; Milner et al. 2017; Dinh et al. 2022). Hidden workers represent a significant loss of productive potential in the workforce (Fuller et al. 2021), and include a disproportionate share of poverty, health, education, and subjective well-being (Mitchell and Muysken 2010; Friedland and Price 2003; Kamerāde and Richardson 2018; Özerkek and Sönmez 2021). Understanding the full scope of these affected groups is challenging as, aside from the unemployed, data is not readily available in official government statistics.

The term “hidden” is used in different contexts, sometimes referring to workers not captured in commonly used statistics (Wilkins 2003), and at other times describing all forms of labour underutilization (Baum and Mitchell 2010). Baert (2021) proposed using the unemployment-to-population ratio and the inactivity-to-population ratio as complementary measures to better understand these hidden workers, referred to as the “iceberg metaphor” of the labour market. Prieto et al. (2022) introduced an alternative unemployment rate that incorporates job shortages to account for discouraged workers. Recent developments in labour market research increasingly focus on including various forms of underutilization, such as discouraged workers and underemployment (Suárez-Grimalt et al. 2022; Fuller et al. 2021). Fuller et al. (2021) introduced the term “hidden workers” to encompass the unemployed, underemployed, and discouraged workers. Three common forms of labour market underutilization include “missing hours,” referring to individuals working part-time but willing and able to work full-time; “missing from work,” describing those who are unemployed but actively seeking employment; and “missing from the workforce”. The current study uses the concept of “hidden workers” (Fuller et al. 2021) as an expanded indicator of unemployment.

A key issue in examining hidden workers is how to classify individuals who are not considered “unemployed.” Recent studies suggest these individuals represent two distinct labour force states, each with different population characteristics (Dinh et al. 2022; Fuller et al. 2021; Baum and Mitchell 2010). Hidden workers may differ considerably from those who are officially unemployed (Brandolini and Viviano 2016, 2018; Hornstein et al. 2014). This distinction carries significant implications for policy responses. Without targeted strategies to increase the visibility of hidden workers, the policy impact may fall short for the hard-to-reach population such as the long-term unemployed, youth unemployed, people with disabilities, and those living in rural, regional, or remote areas. Therefore, accurately identifying hidden workers is crucial, as these groups may require different policy approaches to support their needs. Understanding these distinctions will help in developing targeted, place-based, age-based, and group-based policies and addressing how labour market underutilization can contribute to broader issues of inequity and discrimination.

The following sections outline a context for explaining the distinction of hidden workers compared to the unemployed. The Methods section will outline a protocol for identifying hidden workers in the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) and the analytical methodology for this paper. The results provide descriptive statistics of the hidden worker population and examines the determinants and different subcategories followed by a discussion of these findings.

2. Australian Evidence on Hidden Workers

Standard unemployment rate reporting may limit the development of tailored policy responses and fail to address discrepancies arising from individual characteristics. In Australia, while the reported unemployment rate has generally declined (Treasury 2023), the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have reinforced pre-existing gender dynamics and exacerbated social and economic inequities (Foley and Cooper 2021; Risse 2023). Certain population groups, such as Indigenous Australians, mature-age groups, people with disabilities, single parents, and some migrant groups, have employment at rates significantly below the national average (King et al. 2006; Bowman et al. 2017; Loosemore et al. 2021; Maheen and King 2023). Additionally, mature-age workers, carers, and veterans face unique challenges that hinder their participation in the workforce (Biggs et al. 2016).

A recent Australian Government Treasury report identified that females are less inclined to participate in the labour market or work full-time compared to males, and more likely to engage in unpaid caregiving roles (Treasury 2023), females with children under 15 years of age, and for married people (Stricker and Sheehan 1981; Wooden 1996; Gray et al. 2002). Baum and Mitchell (2022) argued that unemployment and hidden unemployment should be regarded as distinct groups, each with different drivers affecting their labour market status. They found that hidden workers are more closely associated with “choice” factors rather than “constraint” factors. This finding aligns with earlier research (Foley and Cooper 2021; Risse 2023), which suggests that hidden unemployment is closely related to childcare responsibilities and influences female’s decisions about seeking employment.

Social capital is a critical factor in the context of unemployment and discouraged workers, as it encompasses networks of relationships and social connections that are essential for effective job searching. Individuals with robust social networks often gain access to job opportunities through referrals and recommendations, which can be more effective than traditional job search methods (McDonald and Elder 2006; Smith 2016). Access to information about job openings, industry trends, and potential employers is another benefit of strong social networks, offering crucial insights for those seeking to re-enter the labour market (Mouw 2003). Being part of a supportive community also motivates discouraged workers to persist in their job search and explore new career paths, reducing the risk of long-term unemployment (Lancee 2016). Furthermore, social capital can help mitigate labour market disparities by providing marginalized groups with access to networks and resources they might otherwise lack. Thus, social capital is a vital asset for hidden workers, and understanding the role of social capital can inform policy interventions aimed at reducing unemployment, such as programmes that promote community building, networking opportunities, and mentorship.

Other key individual characteristics influencing labour market access include ethnicity, citizenship status, and Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander identity (Wilkinson 2003). Australian-born individuals generally face fewer barriers to entering the labour market compared to those born overseas. Similarly, secondary and tertiary graduates encounter fewer obstacles compared to non-graduates. Employment history and the local labour market context also play significant roles in determining unemployment. Wilkinson (2003) found that underemployment is more prevalent in households with more dependent children, along with factors such as length of employment, type of contract, and the local unemployment rate.

The current Australian unemployment policy predominantly focuses on individuals receiving Jobseeker benefits, which largely overlooks hidden workers who may not be actively seeking work or identifying as unemployed. This study seeks to bridge this knowledge gap by providing an in-depth examination of hidden workers, including a comprehensive breakdown based on various socio-demographic factors. Additionally, it will investigate the disparities between hidden workers and the unemployed.

This study will answer the following research questions.

- What characteristics define hidden workers?

- What sociodemographic factors are associated with being a hidden worker?

- Are hidden workers similar or different to the unemployed?

- What makes them hidden workers and the unemployed?

- What role does gender play for hidden workers and unemployed?

- What are the policy implications for government in relation to hidden workers?

3. Methods

This study draws on data from the HILDA survey, a nationally representative household panel survey. The first wave, data from which is used in this study, was conducted in 2001, seeking information about all members of sampled households, and specifically seeking personal interviews with all household members who turned 15 years of age. The survey collected information on a wide range of personal and household characteristics, including income; sources of income; labour force and employment status; hours of employment; industry and occupation of employment; trade union membership status; tenure with current employer; employer characteristics; labour force history; educational attainment; family circumstances; health; country of birth; and, if born outside Australia, year of arrival in Australia.

HILDA has a series of questions related to social capital. All waves of the HILDA Survey have included items on social capital (contact with family and friends, membership of clubs, volunteering activity, trust,) and related constructs, such as social support and neighbourhood cohesion. In this study, we have created a variable, ‘SC index’ is calculated from based on 4 indicators of social capital ranging from 1 strongly disagree to 7 strongly agree where the higher SC index would mean low level of social capital. The mean of 4 indicators is added to create an index.

- I need help from other people, but I cannot get it.

- I don’t have anyone that I can confide in.

- I have no one to lean on in times of trouble.

- I cannot find someone when I need help.

Respondents were asked about caregiving responsibilities, if they are caring for children under 15, and if they have other care responsibilities for other reasons, such as disability or old age. Importantly for the purposes of this study, the data collected includes information on actual hours of paid work, information on preferred hours of work, making possible the construction of measures of underemployment.

As one of the first to use the concept, hidden workers—broadly defined to encompass individuals typically excluded from standard unemployment statistics—this paper seeks to clarify the distinction between hidden workers and the unemployed, utilizing the most recent HILDA data. This approach enables a comprehensive profiling of this group across various socio-economic dimensions which this paper will focus on.

The integration of both cross-sectional and longitudinal methodologies within a single study may potentially obscure the clarity of the findings, particularly as the policy implications derived from each perspective are likely to differ. Therefore this paper will employ cross-sectional descriptive and regression analysis to understand various categories of hidden workers within an Australian sample for tailored policy resonses for different groups of hidden workers.”

3.1. Definition and Estimation Strategy

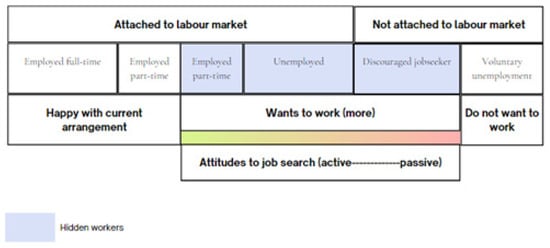

Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework of labour market activity which shows the three main categories of occupational status: underemployment, unemployment and discouraged workers. All three categories represent individuals who would like to work more hours with appropriate wage rates. The underemployed are distinguished from the unemployed as they hold at least some part time paid employment. Both the underemployed and unemployed are distinguished from the discouraged through evidence of engagement with the labour force—the unemployed are not in the labour force believing they are unlikely to successfully gain employment or face an opportunity cost of going out to work compared to staying at home (i.e., childcare costs).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of hidden workers.

The three groups of hidden workers are defined as

- People who normally undertake paid work less than 35 h per week who would prefer to work more hours (part-time underemployed);

- People who are not actively seeking work but would like to work (discouraged);

- People who are actively seeking work (unemployed).

3.2. Key Variables and Model Formulation

In our investigation of the factors associated with unemployment and hidden unemployment, we utilize various individual and household attributes as supply-side factors. At the personal level, we consider variables such as age (including its squared value), sex, marital status, educational attainment, command of English, ethnic background, and social capital. Although long-term health issues and caregiving responsibilities (both within and outside the home) are crucial determinants of one’s labour market position, a potential exists for reverse causality. As a mitigation strategy, we employ lagged variables for these variables from the 2021 survey. Regarding household characteristics, we incorporate the proportion of children under 15 years old (and its squared value), as well as the ratio of employed household members. At the structural level, we include the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), which captures socio-economic resources which may partially reflect spatial conditions.

Formally, to estimate whether an individual is classified as a hidden worker in 2022, based on a set of determining factors, Xi the following formula is proposed:

where Si = 1 if individual i is a hidden worker (or the unemployed) and Si = 0 otherwise. Similarly, the unemployment status in the job market is estimated using the same set of explanatory variables.

Table 1 provides definitions and summary statistics for the variables used in the analysis and all tables can be accessed in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Summary statistics.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Summary of Hidden Workers

4.1.1. Composition of Hidden Workers by Gender

Table 2 shows the composition of hidden workers by different types. In 2022, labour underutilization shows significant gender disparity, particularly in the composition of hidden workers. Overall, unemployment rates are similar between gender types, with males at 4.48% and females at 3.73%. However, hidden worker status differs markedly: 14.35% of males are classified as hidden workers, compared to 27.66% of females. Male hidden workers are primarily discouraged workers (55.19%) or unemployed individuals (28.77%). Among females, however, the majority are underemployed (50.8%), followed by discouraged (37.11%).

Table 2.

Distribution of hidden workers by gender.

Table 3 outlines the distribution of hidden workers by gender and childcare responsibilities, with care burden estimated by the ratio of children aged 15 or below to total household members. Amongst females without children in this age group, 17.96% are hidden workers. This is largely attributed to a higher proportion of older females. However, this figure rises significantly to 47.8% among females with children under 15, with the majority in this group classified as underemployed.

Table 3.

Distribution of hidden workers by gender and childcare responsibility.

4.1.2. Composition of Hidden Workers by Age

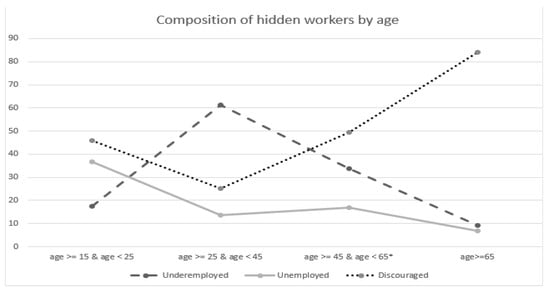

Table 4 presents the age distribution across the three categories of hidden workers. In the 15–25 age group, 17.52% are underemployed, 36.65% are unemployed, and 45.82% are discouraged workers. The 25–45 age group shows the highest proportion of underemployed individuals, with 61.38% underemployed, 13.51% unemployed, and 25.11% discouraged workers. Among the 45–65 age group, 33.66% are underemployed, 16.83% unemployed, and 49.50% discouraged workers. The over 65 age group has the highest percentage of discouraged workers, with 84.10%, while 9.21% are underemployed and 6.69% unemployed. Discouraged workers are predominantly from the over 65 age group, followed by the 45–65 age group. The age distribution of hidden workers is illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Distribution of hidden workers by age group.

Figure 2.

Composition of hidden workers by age group.

Three main findings arise from this descriptive analysis. First, it highlights the gendered nature of underemployment. Specifically, female hidden workers dominate the underemployed category, particularly within the 25–45 age group, reflecting the challenges for working-age females with childcare responsibilities. Second, the analysis shows that over 80% of the ageing population within the hidden workers are categorized as discouraged workers. Third, among the discouraged workers, there is a significant proportion of younger males with lower education levels. Specifically, 57% of younger discouraged workers are males with education below a high school certificate, compared to 35% of younger females in the discouraged group.

4.1.3. Composition of Hidden Workers by Education Level

Table 5 shows a clear pattern: among higher-skilled individuals (e.g., with a college degree), underemployment is the dominant hidden worker category, while among less-skilled individuals (e.g., with a Certificate III/IV or less than Year 12), discouraged workers are more prevalent.

Table 5.

Education levels of hidden workers.

Among individuals with education below Year 12, 62.92% are classified as hidden workers (see Table 5). The underemployment rates among those with postgraduate, graduate diploma, bachelor’s degrees, and certificate III/IV qualifications are 60.74%, 60.94%, 64.94%, and 52.11%, respectively. Notably, 30.37% of those with postgraduate qualifications are categorized as discouraged workers. Although this is a relatively small proportion within the discouraged group, it suggests the discouraged group is diverse and includes individuals with a broad range of education levels.

Examination of education levels and gender is shown in Table 6. While both male and female groups with education levels below Year 12 are likely to be discouraged, only males with relative high education attainments (Postgraduate, Graduate diploma) have a higher portion of being discouraged rather than underemployed or unemployed. Highly educated (Postgraduate, Graduate Diploma, BA) females are likely to be underemployed, comprising 60–70% of the respective education groups. The underemployed group is highly associated with education levels for both genders.

Table 6.

Gender breakdown of education levels.

4.1.4. Distribution of Hidden Workers by SEIFA

Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) assesses relative socio-economic disadvantage and advantage using indicators such as income, education, employment, occupation, housing, and family structure. Workers categorized as unemployed or hidden unemployment are predominantly concentrated within specific SEIFA deciles as indicated in Table 7. A detailed analysis of the underemployed group shows that the proportion of underemployed workers increases significantly with higher SEIFA deciles within the broader hidden worker population.

Table 7.

Distribution of hidden workers by SEIFA.

4.1.5. Main Difficulty in Getting a Job

Table 8 outlines the reasons for underemployment, i.e., workers working in part-time positions but would like to work more. The most frequent reason is caregiving responsibilities, with 72.50% needing to care for children and 6.68% for other care needs. Additionally, 16.89% of workers cites an inability to find full-time employment as their reason for remaining part-time.

Table 8.

Main reasons for underemployment.

For those actively seeking work, Table 9 highlights the primary difficulties in obtaining employment: 16.44% cited a lack of available jobs, 15.99% mentioned too many applicants for the positions, and 12.11% notes no jobs in their field. Over 25% of the difficulties are associated with individual characteristics, including health issues (20.57%), inadequate training or skills and insufficient work experience (13.52%), and unmet educational requirements (8.07%). Additionally, ageism or discrimination accounts for approximately 12.5% of reasons for not being able to secure a job.

Table 9.

Main difficulty in getting a job when unemployed.

The most frequently cited reason by unemployed individuals for not actively looking for work was having health problems. While responses from males and females are generally similar, a higher proportion of females report that unsuitable working hours are a barrier, whereas slightly more males report transportation issues are a concern for employees.

4.2. Regression Analysis on Chances of Being Hidden Workers Compared to Unemployed

The descriptive statistics indicate that the characteristics of hidden workers differ significantly from those of the unemployed. To explore how current labour policies might broaden their focus to include hidden workers, regression analysis has been conducted to highlight the differences in the determinants of hidden workers compared to those of unemployment.

Determinants of hidden workers

For hidden workers, the coefficient of age is negative and significant, whilst its squared term is positive and highly significant. The likelihood of an individual being classified as a hidden worker tends to diminish as their age increases. According to our data, the turning point was estimated at 46 years.

The positive and highly significant coefficient for females in the first column indicates that being female is associated with a higher likelihood of being classified as a hidden worker in comparison to being male. The effect of having children under 15 on an individual’s hidden status is particularly notable. For males, the negative and statistically significant coefficient for the proportion of children under 15, combined with the positive and significant coefficient for its square, suggests a U-shaped relationship. This implies that the probability of being a hidden worker decreases with a lower dependency burden. In contrast, for females the relationship is hump-shaped, indicating that a higher childcare burden increases the likelihood of being a hidden worker. This highlights that childcare responsibilities have the opposite effect for males and females.

For the educational level, completion of Year 12 or above was associated with a lower probability of being a hidden worker relative to those with a Year 11 or below education. For females, higher education levels tend to reduce the likelihood of being a hidden worker, indicating a greater sensitivity to educational attainment among female hidden workers.

Determinants of unemployment

For unemployment, a nonlinear relationship is observed between age and hidden status for both male and female, The second part of Table 10 shows that unemployment group has a similar association in females while the nonlinear effect of age disappears in males.

Table 10.

Determinants of being hidden workers and unemployment.

In addition to age, several independent variables also influence the likelihood of being unemployed, including gender and educational qualifications. The table suggests that a U-shaped relationship exists for males and females for unemployment, suggesting no gender-specific impact on an individual’s unemployment status. A number of higher educational qualification dummy variables such as having a postgraduate degree shows that males who acquire those qualifications are more likely to be employed compared to males with Year 11 or below. However, other than having a diploma or postgraduate degree, other education levels are not significantly associated with decreasing the risk of male unemployment. Educational attainment levels were not statistically significant for female who were unemployed; however, for hidden workers educational levels were highly significant. The child ratio coefficients in both male and female groups are positive, which illustrates that having a child impact both genders in similar way for the unemployed. This difference may potentially demonstrate a possibility that ‘intrahousehold care allocation’ element might have forced the females to be hidden workers, if they can rely on their male counterparts or other means. For females, the role of caregiving other than childcare did not show statistical significance on unemployment.

The common factor that affects both groups are long-term health condition and social capital. The number of household members in the labour force and long-term health conditions are relevant to unemployment and being a hidden worker. Social capital (such as lacking support networks) is inversely related to being classified as unemployed or hidden implying the importance of social capital for both groups. For low socio-economic areas (SEIFA), while a significant relationship is identified for male hidden workers, the relationship with unemployment was not significant for males or females.

4.3. Regression Analysis on Different Categories of Hidden Workers

A multinomial probit model was used to examine factors associated with the different categories of hidden workers. This type of model considers all possible outcomes together and accounts for how people might choose between them based on similar personal or household factors.

First, age shows a statistically significant U-shaped relationship with all three hidden categories, where the strongest association is found from discouraged status, implying that early and older age groups tend to face job vulnerability whilst midlife is the most stable phase of labour market status. Second, females are more likely to be underemployed compared to its counterpart, male, reflecting labour market segmentation. This is in line with the finding of Duncan et al. (2024) that female disproportionately occupy part-time and precarious positions in Australia. Third, educational qualification is especially relevant for job discouragement. Table 11 shows higher qualification tends to significantly lower the probabilities of becoming discouraged whilst its effects on underemployment or unemployment are not significant. Those with higher education are less likely to become discouraged and more likely to remain in stable employment. Fourth, the effect of child ratio on labour market status presents notable nonlinear patterns. The inverted U shape association with underemployment suggests childcare responsibilities is likely to push individuals into part-time job but excessive burden tends to reduce labour market participation. In contrast, the U-shape relationship found from unemployment and discouragement might imply that whilst individuals with lower childcare responsibilities are motivated in job search, they are likely to face the risk of joblessness or withdrawal from labour market as the responsibilities increases. Finally, the lack of social capital proxied by ‘SC index’ increases the risk of both unemployment and discouragement, suggesting that social isolation not only limits access to job opportunities, but also erodes motivation to stay active in job search. For underemployed, the coefficient estimate is statistically insignificant.

Table 11.

Multinomial probit model for different categories of hidden workers.

5. Discussion: Policy Measures for Unemployed or Hidden Workers?

This paper aims to understand the broad spectrum of labour underutilisation and is the first attempt in Australia to apply the definition of hidden workers and analyze different sociodemographic variables using 2022 HILDA data. The descriptive statistics reveal that various types of hidden workers are predominantly represented by specific age and gender groups. The study confirms that Australian women bear the greatest burden of unpaid domestic work, balancing paid employment with child-rearing and caregiving responsibilities. The analysis highlights significant gaps between hidden workers and the unemployed, suggesting areas needing policy intervention. Specifically, female hidden workers experience a notable reduction in their hidden status with higher levels of education. For these workers, whose hidden status is less influenced by labour market conditions, policies should focus on enhancing job mobility and providing better support for childcare.

A key direction for the Australian labour market (Treasury 2023) involves addressing gender barriers to work, with ongoing discussions around the National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality. The Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce has been established to advise the Australian Government on advancing women’s economic equality and achieving gender parity (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2023). However, despite these positive initiatives, the government has not fully leveraged its potential to drive meaningful change for hidden workers. The recent abolition of the ParentsNext programme, which aimed to support single mothers, has been criticized for entrenching inequalities and discrimination (Department of Employment and Workplace Relations 2022).

Given the significant impact of educational attainment on female hidden workers, implementing industry-led job placement programmes aligned with higher education could be highly effective in reducing the number of female hidden workers. Australia currently has in place, return-to-work programmes, however, systemic gender biases in hiring practices and the availability of flexible work arrangements, which are crucial for women balancing work and family duties (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2024). Moreover, Arun et al. (2004) examined the impact of career breaks on women’s wages and roles in Australia, finding that the reason for taking leave significantly affects wage penalties and career trajectories. Women who took short career breaks for reasons other than child-rearing faced smaller wage penalties (5%) compared to those who took parental leave, with short and long parental leaves resulting in 10% and 17% wage penalties, respectively. Additionally, women who took long periods of parental leave were more likely to return to work in different roles or organizations. Theunissen et al. (2011) further explored the effects of career breaks, noting that breaks due to family responsibilities or unemployment negatively impacted subsequent wages, whereas breaks for self-employment or education did not.

Additionally, whilst programmes may offer short-term training, they frequently lack long-term career development opportunities, which are crucial for sustainable employment and career advancement (Johnson 2024). To enhance their impact, more personalized support, address structural barriers in the labour market, and establish partnerships with industries to create clear pathways for women’s career progression may improve outcomes (Rees 2022).

The significant role of social capital for both hidden workers and the unemployed is a key finding. In Australia, numerous programmes offer services designed to build social capital, including work experience placements, skills development workshops, and opportunities for community engagement. Transition to Work focuses on connecting participants with community services, mentors, and peer networks, recognizing the importance of social capital in facilitating successful transitions into the workforce (Brotherhood of St Laurence 2020). Another significant initiative is the New Enterprise Incentive Scheme (NEIS), which supports unemployed individuals interested in starting their own businesses by fostering entrepreneurial skills and connecting participants with experienced business mentors (Department of Education, Skills and Employment 2021).

However, programmes such as these may not reach all eligible individuals, particularly those in remote or underserved areas. Geographic and logistical barriers can limit access to programme resources and networking opportunities, reducing the potential for building social capital (Rodríguez-Soler and Verd 2023). Many programmes are designed with short-term goals in mind, such as immediate job placement, rather than long-term social capital development. Quick outcomes maybe the focus rather than sustainable community and network building, which are essential for long-term employability and resilience (Borland and Tseng 2011). Therefore, it is essential to implement local-level, long-term, sustained social capital-focused interventions for hidden workers to increase visibility of hidden workers in the employment service sectors.

Furthermore, most unemployment interventions focus on employability, skills development, and job-search training (Hult et al. 2020). Nevertheless, social capital plays a vital role in sustaining health and well-being, and this research demonstrates that having low social capital is associated not only with unemployment but also with being part of the hidden workforce.

This study also highlights a segment of hidden workers comprising younger males with low education levels living in areas with low socio-economic resources. Addressing the needs of this hidden worker group requires tailored policies beyond those which are based on standard unemployment measures. Although, our findings did not identify significant socio-economic area effects for unemployment for either gender, this was not the case for male hidden workers. These individuals are affected by the resources and opportunities available in their local area. Enhancing local job opportunities and developing a robust job market ecosystem could a measure used to integrate male hidden workers into the labour market. Additionally, the lower statistical significance of education for male hidden workers compared to their female counterparts warrants further investigation. Exploration is required as to whether education is less utilized by males due to its perceived ineffectiveness or if other factors are of significance.

The visibility of discouraged workers in government programmes like Jobactive in Australia was a critical issue, as these individuals often fall through the cracks of traditional employment services. Jobactive, was the Australian Government employment service which ran from July 2015 to June 2022, designed to assist job seekers in finding employment, through job search support, training, and employer incentives. However, discouraged workers, who have ceased looking for work due to perceived lack of opportunities, may not actively engage with such programmes. This lack of engagement can result from various factors, including a mismatch between the services offered and the specific needs of discouraged workers, as well as psychological barriers such as low self-esteem and motivation (Borland and Tseng 2011). To improve visibility and engagement, Workforce Australia which replaced Jobactive, aims to reach out to underrepresented populations digitally, offering tailored support that addresses their unique challenges and barriers to re-entering the labour market.

In the European Union, the European Social Fund (ESF) supports projects that aim to increase labour market participation, especially the youth unemployment targeting NEETs (Young People not in Employment, Education or Training) who are often the most discouraged and difficult to reach (Eurofund 2012). However, the effectiveness of these programmes in reaching discouraged workers varies across member states (Bussi et al. 2019). To enhance visibility, it is important for government programmes to incorporate strategies that specifically identify and address the needs of discouraged workers, such as through community partnerships, enhanced data collection, and the integration of mental health and motivational support services. Thus, these programmes can better support discouraged workers in overcoming barriers and successfully re-entering the workforce.

6. Limitations & Future Research and Development

Direct comparisons between the determinants of hidden workers and those of unemployment should be approached with caution. The status of discouraged workers is shaped by their decision to refrain from seeking employment, whereas unemployment is often an outcome independent of the choice of an individual. The issue of discouragement as a personal decision or whether it is influenced by structural factors is not yet resolved. According to the definition of hidden workers, an individual’s willingness to be employed or to work more hours reflects their intention to participate in the labour market, even if their efforts are passive. Additionally, discouraged workers represent one subset within the broader category of hidden workers. When interpreting the results, it is important to consider these distinctions, and the specific definitions applied to each labour market status.

Generalisability of the findings to other countries should be performed with caution due to the different regulatory and policy environments in which employment arises. Childcare responsibilities frequently present substantial obstacles for women in the labour market across various nations, contributing to employment gaps, underemployment, and gender wage disparities. Different countries have implemented a range of policies to address these challenges, including subsidized childcare, parental leave, and flexible working arrangements. The effectiveness of these measures is context-dependent and may vary. Future opportunities for research may involve the investigation of how exogenous shocks, such as policy changes or economic disruptions, affect transitions across employment states for hidden workers.

Our evidence highlights the potential for more tailored policy responses to hidden workers in Australia. This study also supports the importance of refining and expanding the conceptualizations, theories, and operationalization of the hidden worker category. However, further investigation is needed into how various overlapping social identities impact work opportunities and constrained choices.

Future research should explore the diversity within the hidden worker group to understand both its heterogeneity and homogeneity. Assessing health and well-being outcomes within this group could help determine whether these characteristics are consistent. Additionally, examination of the dynamics of hidden workers—who transitions in or out of this status and how individuals move between its sub-groups—to identify the most effective pathways for upward mobility is required. Research using causal analysis could be beneficial to identify the factors that influence shifts between these groups. Lastly, collecting qualitative data from hidden workers could provide deeper insights into their lived experiences. These areas of research may offer promising avenues to enhance our understanding of the complexities and inequalities faced by hidden workers.

7. Conclusions

This paper begins by exploring those who are not accounted for in labour market statistics, analyzing their demographics, work patterns, and challenges to discern the key implications for policy responses. Consequently, this study aims to accurately identify hidden workers and compare this group with the unemployed, who represent the statistically visible segment of labour underutilization. The hidden group, which includes discouraged and underemployed individuals, reveals gendered labour market responses within households, with women being overrepresented due to childcare responsibilities. The discouraged population among younger males with low education levels warrants further attention. The association of these males with low SEIFAs highlights the inequity and discrimination tied to local resources, calling for government interventions. Income insecurity among the older population and broader labour market discrimination is another area requiring tailored policies, given the implications for the health and well-being of the elderly. This study provides a basis for understanding the diverse range of hidden workers and insights into potential policy interventions for both public and private services needed to more effectively address the needs of hidden workers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/dairy6020016/s1, Figure S1: Graphical representation of hidden workers; Figure S2: Composition of hidden workers by age group; Table S1: Summary statistics; Table S2: Distribution of hidden workers by gender; Table S3: Distribution of hidden workers by gender and childcare responsibility; Table S4: Distribution of hidden workers by age group; Table S5: Education levels of hidden workers; Table S6: Gender breakdown of education levels; Table S7: Distribution of hidden workers by SEIFA; Table S8: Main reasons for underemployment; Table S9: Main difficulty in getting a job for the unemployed; Table S10: Determinants of being hidden workers and unemployment; Table S11: Multinomial probit model for different categories of hidden workers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and W.K.; methodology, W.K.; software, S.L.; validation, S.L., W.K. and J.O.; formal analysis, S.L., W.K. and J.O.; investigation, S.L., W.K. and J.O.; resources, S.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and W.K.; writing—review and editing, S.L., W.K. and J.O.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, J.O.; project administration, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of La Trobe University (HEC23459 on 27 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arun, Shoba V., Thankom G. Arun, and Vani K. Borooah. 2004. The effect of career breaks on the working lives of women. Feminist Economics 10: 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, Stijn. 2021. The iceberg decomposition: A parsimonious way to map the health of labour markets. Economic Analysis and Policy 69: 350–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Scott, and William F. Mitchell. 2010. Labour underutilisation and gender: Unemployment versus hidden-unemployment. Population Research and Policy Review 29: 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Scott, and William Mitchell. 2022. Labor Underutilization in the years following the GFC: An Australian example. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies 8: 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, Simon, Dina Bowman, Helen Kimberley, and Michael McGann. 2016. Introduction: Policy responses to ageing and the extension of working lives. Social Policy and Society 15: 607–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, Jeff, and Yi-Ping Tseng. 2011. Does ‘Work for the Dole’ work? An Australian perspective on work experience programmes. Applied Economics 43: 4353–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Dina, Michael McGann, Helen Kimberley, and Simon Biggs. 2017. ‘Rusty, invisible and threatening’: Ageing, capital and employability. Work, Employment and Society 31: 465–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, Andrea, and Eliana Viviano. 2016. Behind and beyond the (head count) employment rate. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society 179: 657–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, Andrea, and Eliana Viviano. 2018. Should statistical criteria for measuring employment and unemployment be re-examined. IZA World of Labor: Evidence-Based Policy Making 445: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Brotherhood of St Laurence. 2020. Transition to Work Community of Practice. Available online: https://library.bsl.org.au/jspui/bitstream/1/11916/1/BSL_YouthAdvocacy_TtWCoP_Factsheet_May2020_01.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Bussi, Margherita, Bjørn Hvinden, and Mi Ah Schoyen. 2019. Has the European Social Fund been effective in supporting young people? In Youth Unemployment and Job Insecurity in Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 206–29. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. 2021. New Enterprise Incentive Scheme (NEIS). Available online: https://www.dewr.gov.au/new-business-assistance-neis/neis-training-support-and-payments (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Department of Employment and Workplace Relations. 2022. ParentsNext National Expansion 2018–2021: Evaluation Report. Canberra: Department of Employment and Workplace Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2023. Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce, Author, Issuing Body. A 10-Year Plan to Unleash the Full Capacity and Contribution of Women to the Australian Economy 23–33: Women’s Economic Equality. Available online: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-3244873331 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 2024. National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women/working-women-strategy-gender-equality (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Dinh, Huong, Lyndall Strazdins, Tinh Doan, Thuy Do, Amelia Yazidjoglou, and Cathy Banwell. 2022. Workforce participation, health and wealth inequality among older Australians between 2001 and 2015. Archives of Public Health 80: 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Alan, Silvia Salazar, and Lili Loan Vu. 2024. Gender Equity Insights 2024: The Changing Nature of Part-Time Work in Australia. Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre Report Series GE09. Bentley: Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre (BCEC), Curtin Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofund. 2012. NEETs—Young People not in Employment, Education or Training: Characteristics, Costs and Policy Responses in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Meraiah, and Rae Cooper. 2021. Workplace gender equality in the post-pandemic era: Where to next? Journal of Industrial Relations 63: 463–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, Daniel S., and Richard H. Price. 2003. Underemployment: Consequences for the health and well-being of workers. American Journal of Community Psychology 32: 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Joseph B., Manjari Raman, Eva Sage-Gavin, and Kristen Hines. 2021. Hidden Workers: Untapped Talent. Boston: Harvard Business School Project on Managing the Future of Work and Accenture. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Matthew, Alexandra Heath, and Boyd Hunter. 2002. An Exploration of Marginal Attachment to the Australian Labour Market. Sydney: Economic Research Department, Reserve Bank of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Heslin, Peter A., Myrtle P. Bell, and Pinar O. Fletcher. 2012. The devil without and within: A conceptual model of social cognitive processes whereby discrimination leads stigmatized minorities to become discouraged workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 33: 840–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornstein, Andreas, Marianna Kudlyak, and Fabian Lange. 2014. Measuring resource utilization in the labor market. FRB Economic Quarterly 100: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hult, Marja, Kirsi Lappalainen, Terhi K. Saaranen, Kimmo Räsänen, Christophe Vanroelen, and Alex Burdorf. 2020. Health-improving interventions for obtaining employment in unemployed job seekers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1: CD013152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Catrina. 2024. Impact of Educational Initiatives and Pathway Programs on Employment. In Employing Our Returning Citizens: An Employer-Centric View. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 257–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kamerāde, Daiga, and Helen Richardson. 2018. Gender segregation, underemployment and subjective well-being in the UK labour market. Human Relations 71: 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Robert, Geoffrey Waghorn, Chris Lloyd, Pat McLeod, Terene McMah, and Cliff Leong. 2006. Enhancing employment services for people with severe mental illness: The challenge of the Australian service environment. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40: 471–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kler, Parvinder, Azhar Hussain Potia, and Sriram Shankar. 2018. Underemployment in Australia: A panel investigation. Applied Economics Letters 25: 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancee, Bram. 2016. Job search methods and immigrant earnings: A longitudinal analysis of the role of bridging social capital. Ethnicities 16: 349–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sora, and Woojin Kang. 2024. Research Landscape on Hidden Workers in Aging Populations: Bibliometric Review. Social Sciences 13: 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jinjing, Alan Duncan, and Riyana Miranti. 2015. Underemployment among mature-age workers in Australia. Economic Record 91: 438–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loosemore, Martin, Suhair Zaid Alkilani, and Ahmed WA Hammad. 2021. The job-seeking experiences of migrants and refugees in the Australian construction industry. Building Research & Information 49: 912–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheen, Humaira, and Tania King. 2023. Employment-related mental health outcomes among Australian migrants: A 19-year longitudinal study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 57: 1475–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, Steve, and Glen H. Elder, Jr. 2006. When does social capital matter? Non-searching for jobs across the life course. Social Forces 85: 521–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee-Ryan, Frances M., and Jaron Harvey. 2011. “I have a job, but…”: A review of underemployment. Journal of Management 37: 962–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, Allison, Tania Louise King, Anthony D. LaMontagne, Zoe Aitken, Dennis Petrie, and Anne M. Kavanagh. 2017. Underemployment and its impacts on mental health among those with disabilities: Evidence from the HILDA cohort. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 71: 1198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, William, and Joan Muysken. 2010. Full employment abandoned: Shifting sands and policy failures. International Journal of Public Policy 5: 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, Ted. 2003. Social capital and finding a job: Do contacts matter? American Sociological Review 68: 868–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özerkek, Yasemin, and Fatma Didin Sönmez. 2021. Labor Underutilization in European Countries: Some Facts About Age and Gender. Yildiz Social Science Review 7: 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, Joaquín, Kirsten Sehnbruch, and Diego Vidal. 2022. A dynamic counting approach to measure multidimensional deprivations in jobs. Applied Economics Letters 31: 907–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, Teresa. 2022. Women and the Labour Market. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risse, Leonora. 2023. The economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: A closer look at gender gaps in employment, earnings and education. Australian Economic Review 56: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Soler, Joan, and Joan Miquel Verd. 2023. Informal social capital building in local employment services: Its role in the labour market integration of disadvantaged young people. Social Policy & Administration 57: 679–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, Debbie Laliberte, and Rebecca Aldrich. 2021. Producing precarity: The individualization of later life unemployment within employment support provision. Journal of Aging Studies 57: 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudman, Debbie Laliberte, and Rebecca M. Aldrich. 2017. Discerning the social in individual stories of occupation through critical narrative inquiry. Journal of Occupational Science 24: 470–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Sandra Susan. 2016. Job-finding among the poor. In The Oxford Handbook of the Social Science of Poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 438–61. [Google Scholar]

- Stricker, Peter, and Peter Sheehan. 1981. Hidden Unemployment: The Australian Experience. Melbourne: Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Grimalt, Laura, Andrés Coco-Prieto, and Montserrat Simó-Solsona. 2022. Double invisibility: The effects of hidden unemployment on vulnerable populations in southern European countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Revista Española de Sociología 31: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunissen, Gert, Marijke Verbruggen, Anneleen Forrier, and Luc Sels. 2011. Career sidestep, wage setback? The impact of different types of employment interruptions on wages. Gender, Work & Organization 18: e110–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasury. 2023. Working Future: The Australian Government’s White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities. Available online: https://treasury.gov.au/employment-whitepaper/final-report (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Wilkins, Nigel. 2003. Fractional Integration at a Seasonal Frequency with an Application to Quarterly Unemployment Rates. Sydney: Mimeo, School of Finance and Economics, UTS. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, David. 2003. New Deal for Young People: Evaluation of Unemployment Flows. PSI Research Discussion Series 15. London: Policy Studies Institute, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wooden, Mark. 1996. The Australian labour market March 1996. Australian Bulletin of Labour 22: 3–27. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).