The Convergence of Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in West Africa: Migration Pressure Factors and Criminal Actors

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Convergence of Human Trafficking and Smuggling in the Migration Process

2. About the Method

3. Results

3.1. Concomitant Factors in the Region: Context Analysis

3.1.1. (Mis)governance and Coups d’état

3.1.2. Economic Contradictions

3.1.3. Social Fragility

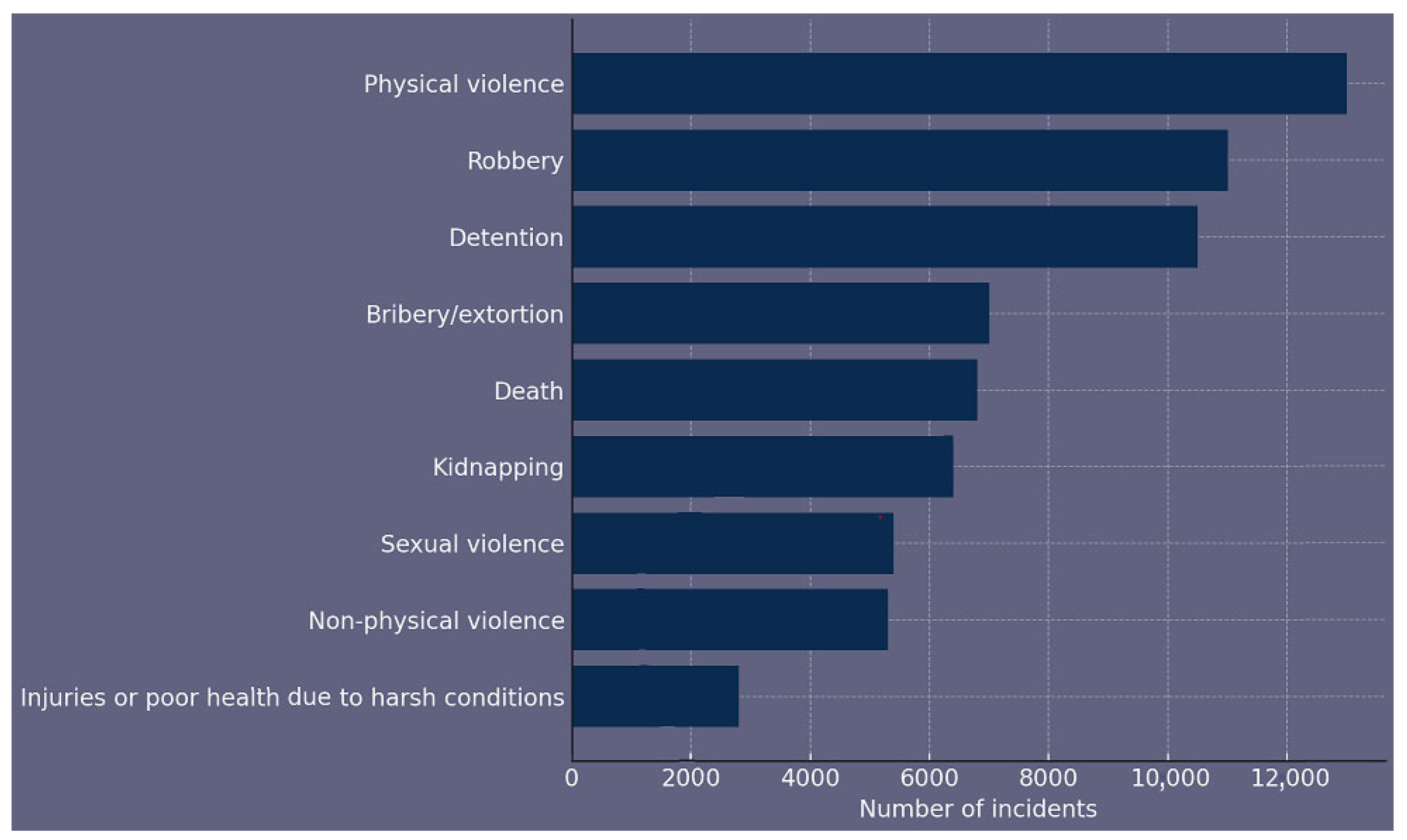

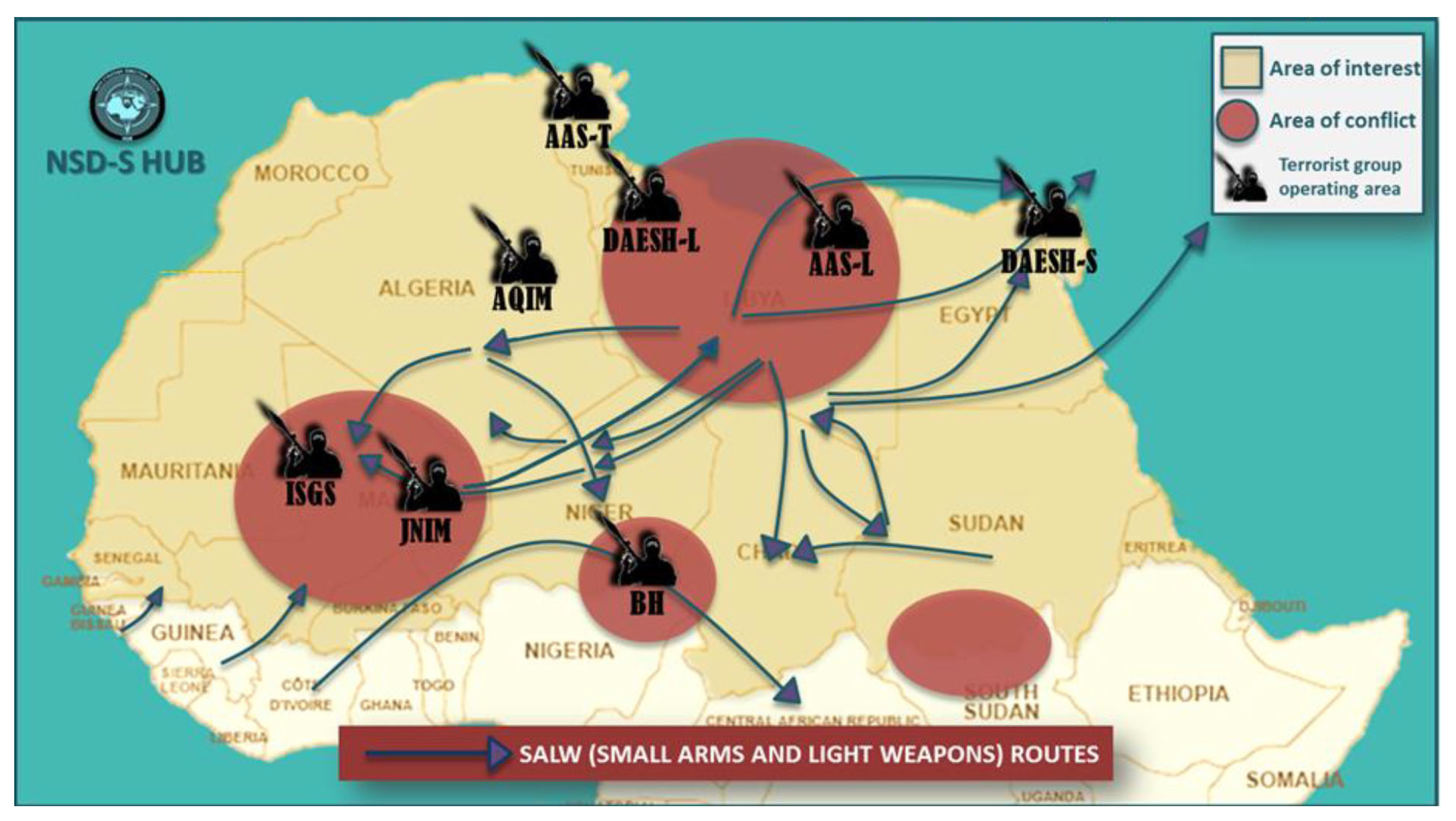

3.1.4. Violence and Insecurity

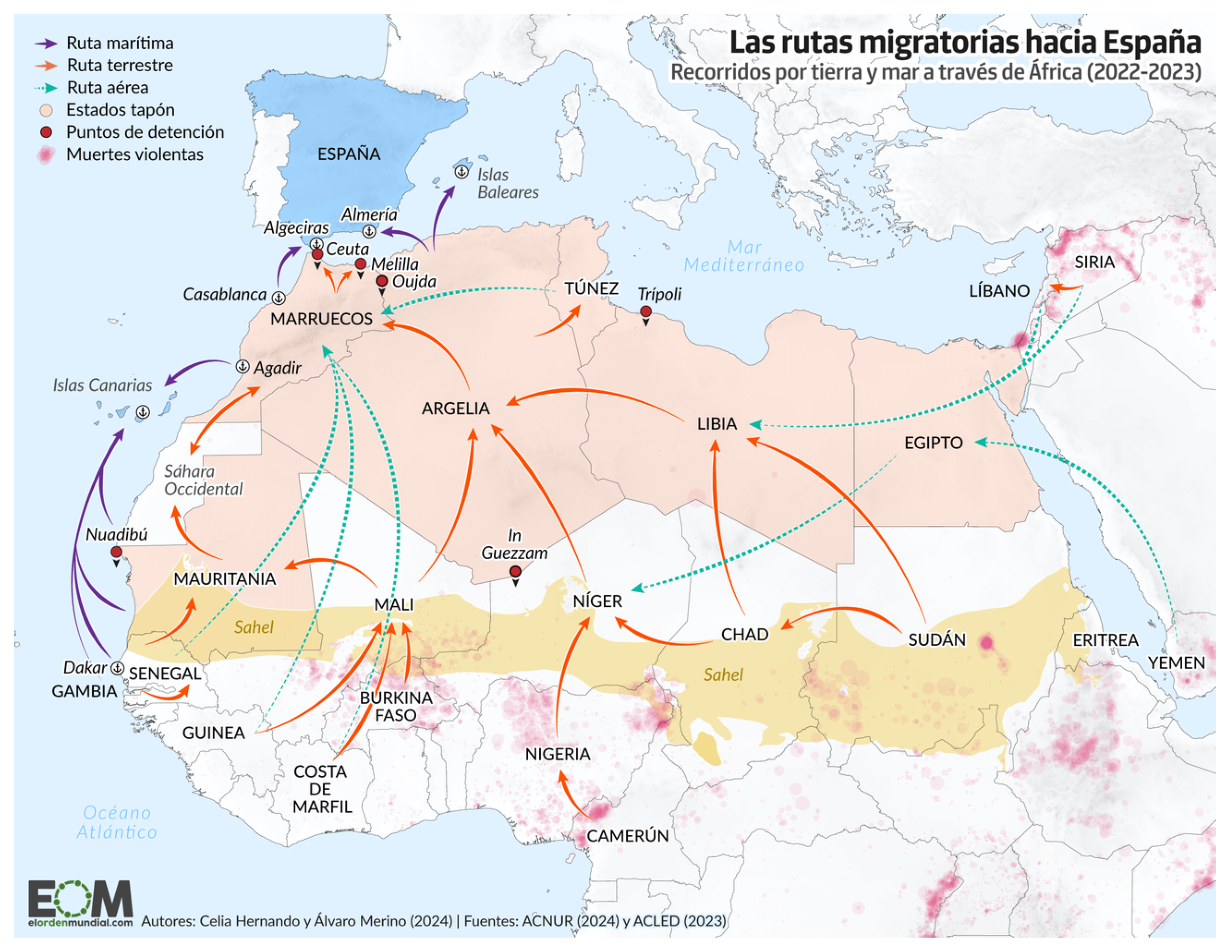

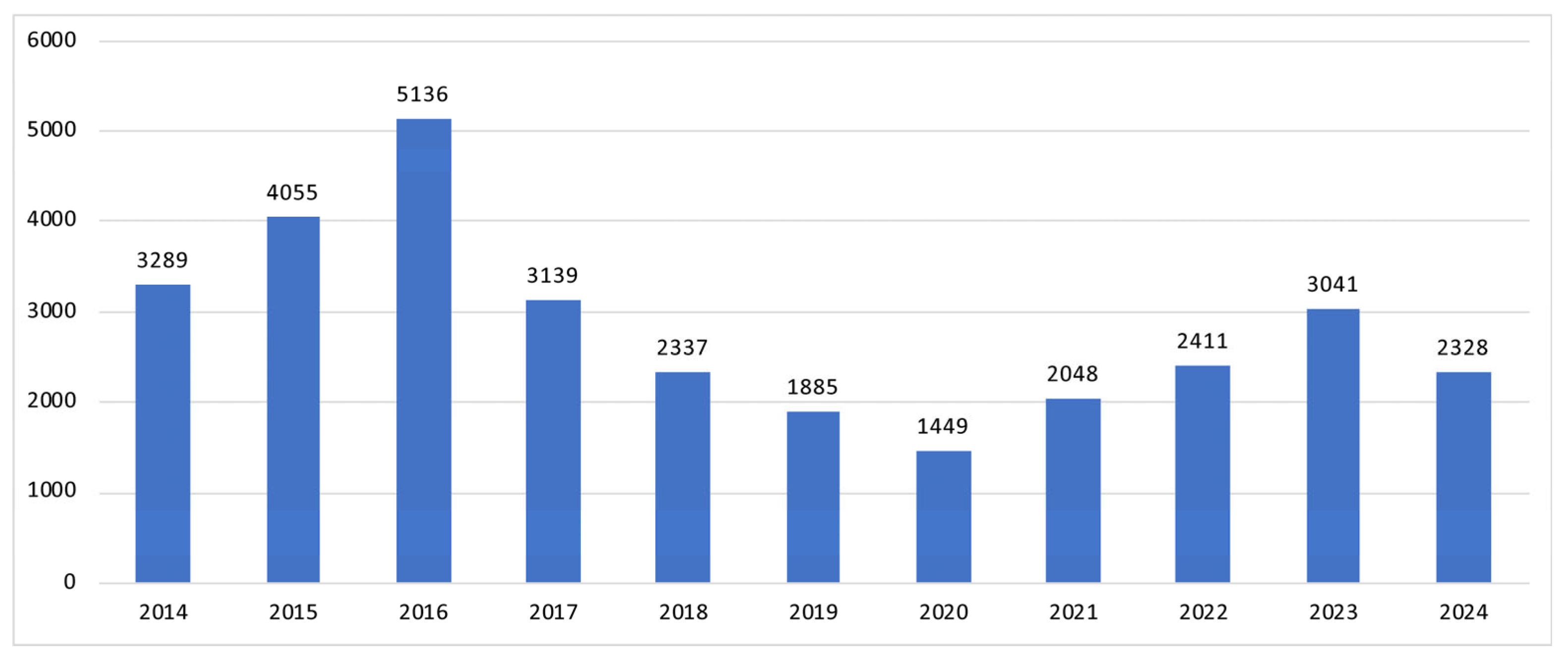

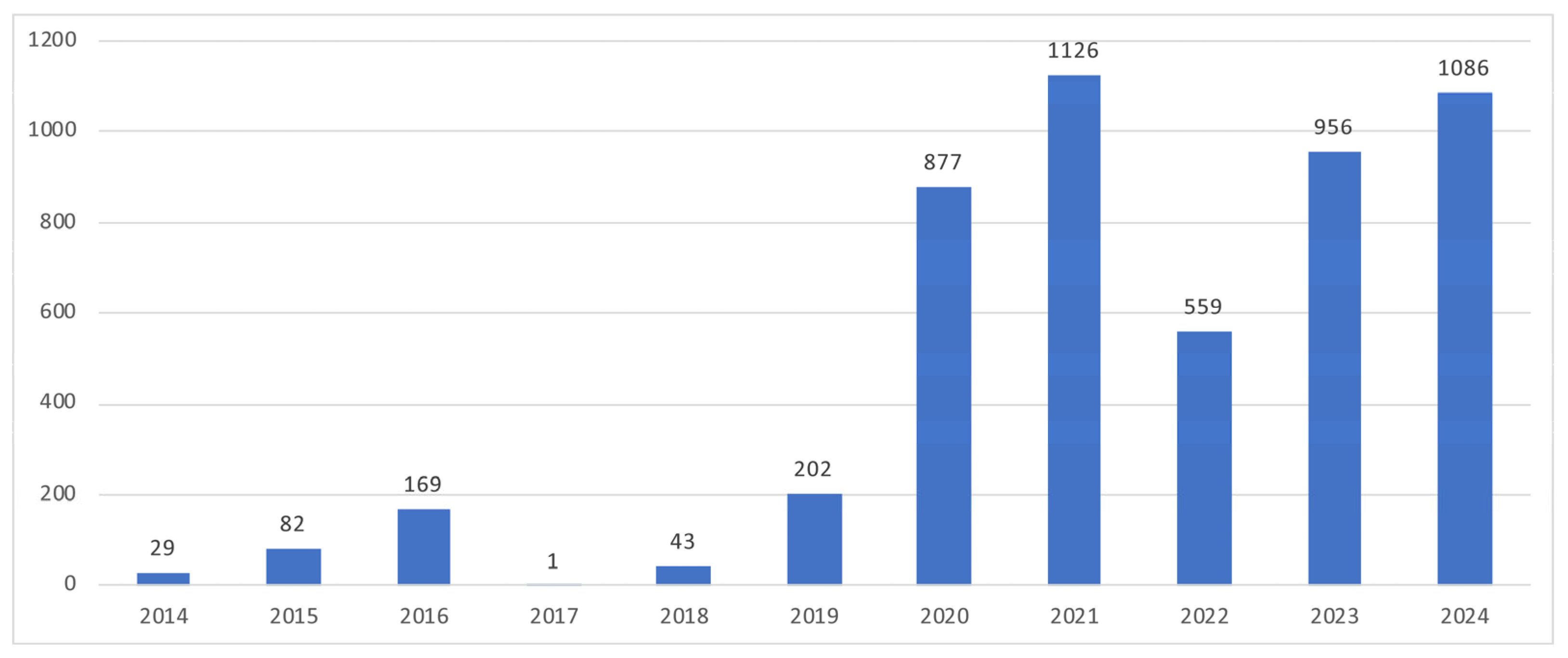

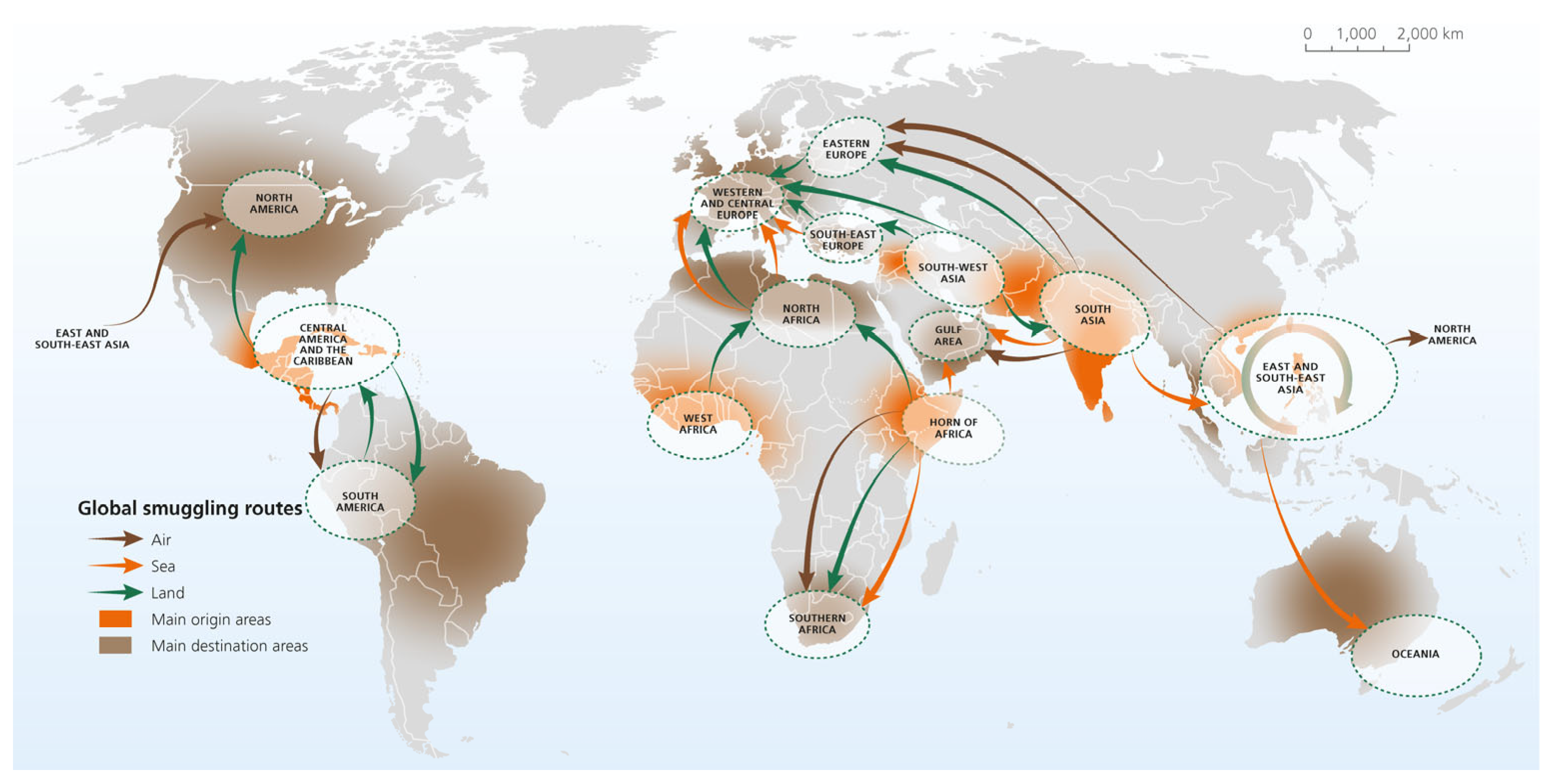

3.2. Migration in West Africa and Migratory Corridors

3.3. The Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling Connection: Criminal Actors on Migration Routes

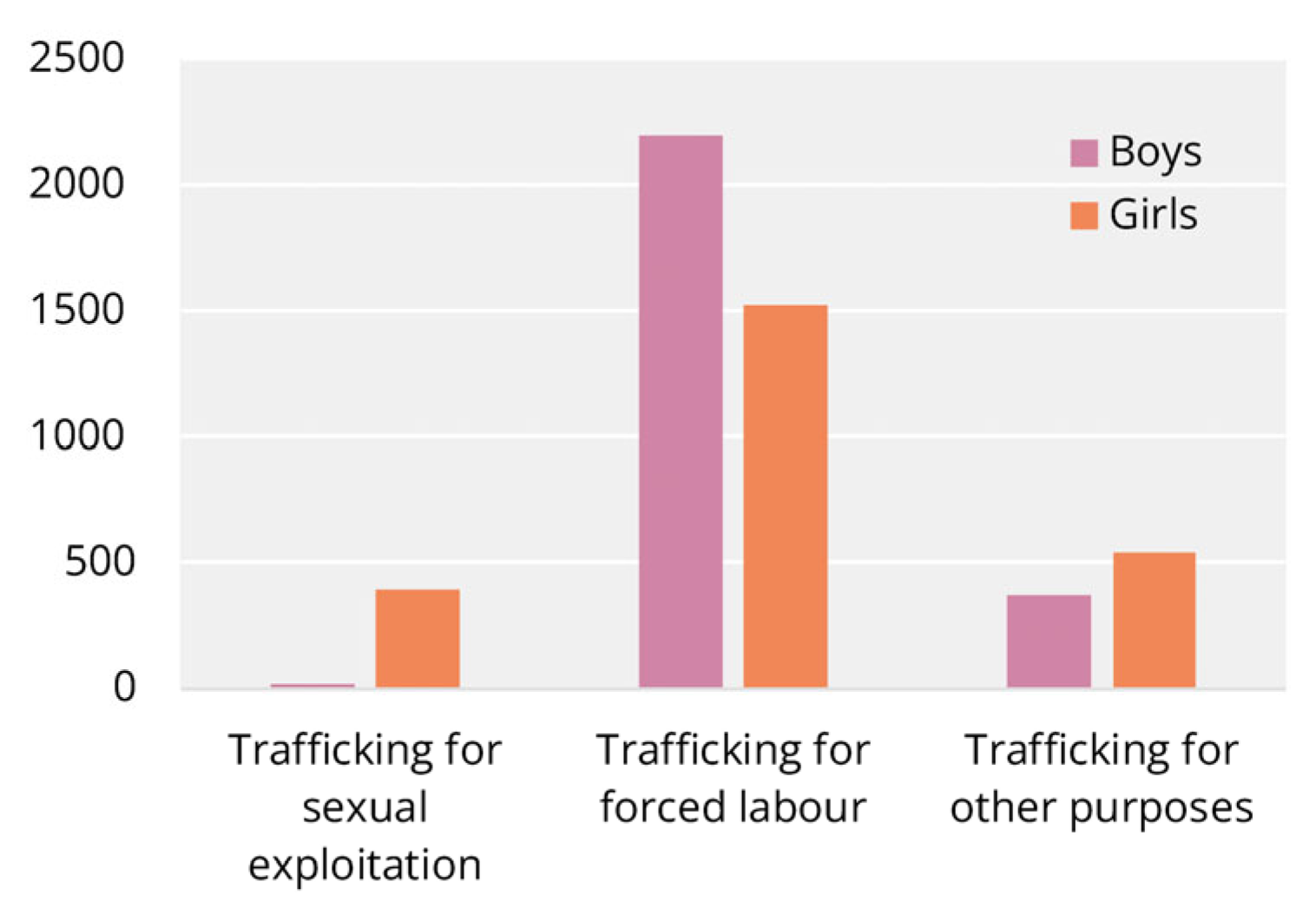

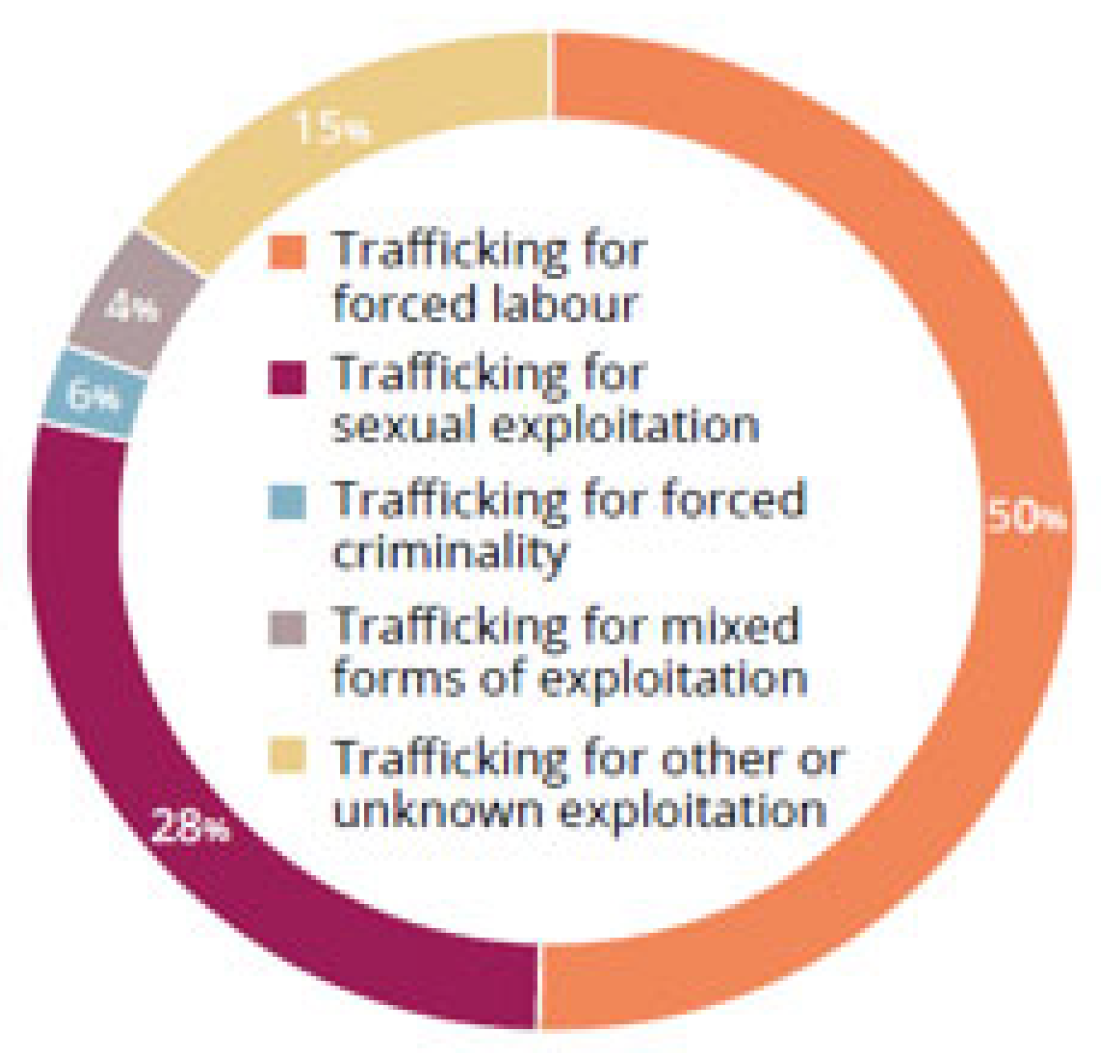

Human trafficking has negative economic and social effects, long-term repercussions on physical and mental health, and implications related to human rights. It is also highly gendered; women and girls are more vulnerable to trafficking for sexual exploitation, forced marriage, and domestic servitude, while men and boys are more exposed to trafficking for labor exploitation in sectors such as fishing and mining”

In the context of trafficking occurring along migration routes, the same actors involved in the smuggling industry may opportunistically collaborate with, or operate as, trafficking networks aiming at exploiting migrants. Research on the routes to North Africa or to the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council has shown how, in some cases, smuggler-traffickers seem to be part of a broader system that starts with an initial contact with migrants in their community of origin and concludes with exploitation in transit or at the destination. Also seen in this context are traffickers who, as opportunistic criminals or individuals, are able to exploit these vulnerable migrants en route.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

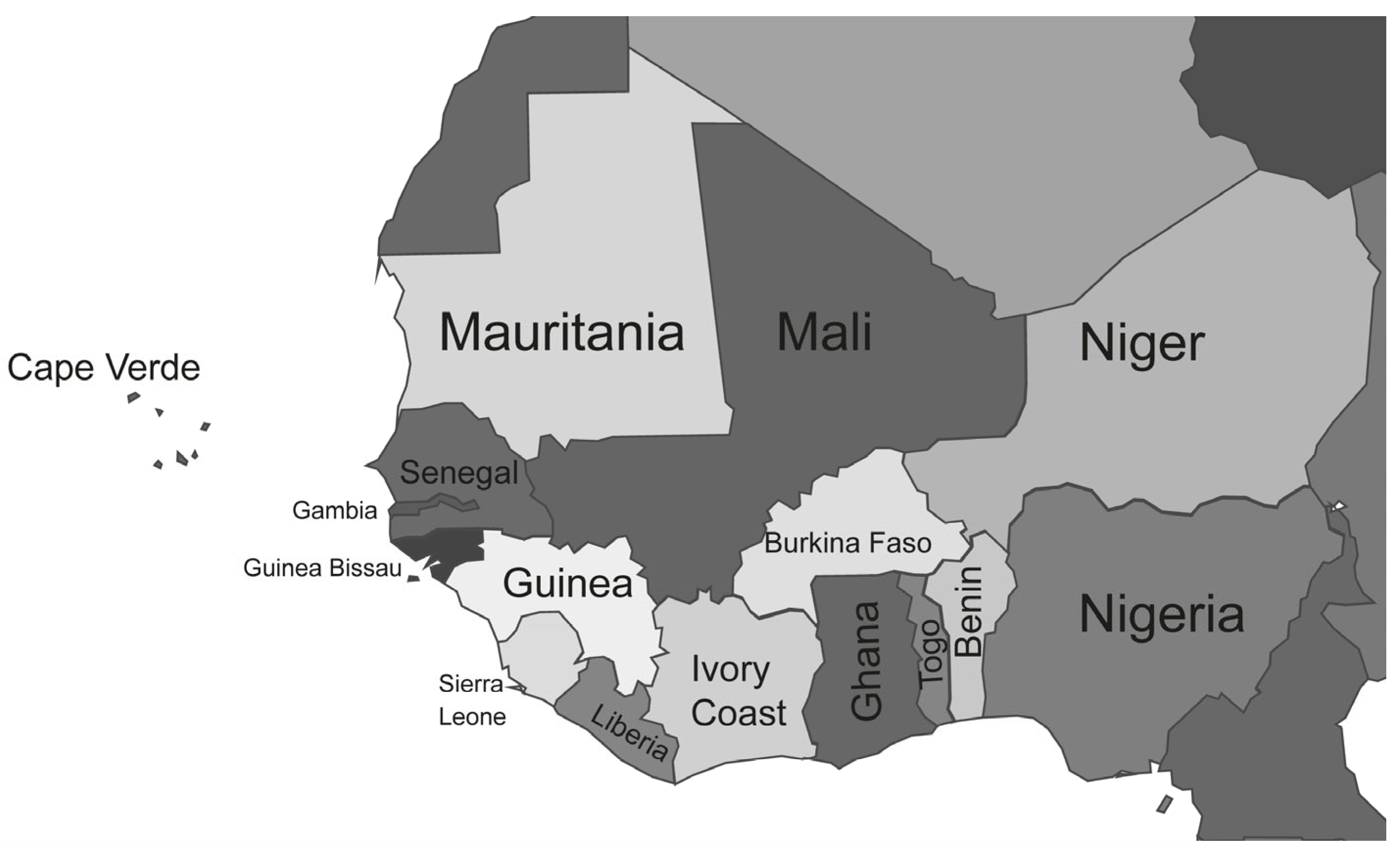

| 1 | West Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Gambia, and Togo, all of them, except Mauritania, are also part of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). |

| 2 | Fragility is generally considered in its economic, environmental, political, social, and security dimensions (OECD 2009). Of the 16 countries, 5 are ranked in the top 25 (The Fund for Peace 2024). |

| 3 | Central Africa: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Sao Tome and Principe. |

| 4 | In the last fifty years, its population has quadrupled. |

| 5 | A country’s score is the perceived level of public sector corruption on a scale of 0–100, where 0 means highly corrupt and 100 means very clean. A country’s rank is its position relative to the other countries in the index. Ranks can change merely if the number of countries included in the index changes. |

| 6 | Wagner Group leader, Evgeny Prigozhin, and his number two, Dmitri Utkin, died in a plane crash on 23 August 2024. |

| 7 | Of the countries that make up the region, Ghana and Senegal are relatively well ranked in the world peace index; however, this has not been reflected in the human development index, where they number among the lower-middle rankings, although above the other countries in the region. |

| 8 | JNIM was created in 2017 from the conjunction of five al Qaeda-following groups: AQIM’s Sahara Emirate, Ansar al Din, the Macina Liberation Front, and al Murabitoun and a fifth group, based in Burkina Faso, Ansar al Islam. |

| 9 | They are formed by the accumulation of migratory movements over time. |

References

- Abu, Mumuni, Samuel N. A. Codjoe, W. Neil Adger, Sonja Fransen, Dominique Jolivet, Ricardo Safra De Campos, Maria Franco Gavonel, Charles Agyei-Asabere, Anita H. Fábos, and Caroline Zickgraf. 2024. Micro-scale transformations in sustainability practices: Insights from new migrant populations in growing urban settlements. Global Environmental Change 84: 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acién González, Estefanía. 2024. Nigerian Migrant Women and Human Trafficking Narratives: Stereotypes, Stigma and Ethnographic Knowledge. Social Sciences 13: 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- African Union. 2013. Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. Available online: https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Agbeve, Kwami, and José Maroto Blanco. 2024. Historia de Togo. Madrid: La Catarata. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre Unceta, Rafael. 2021. Inseguridad Alimentaria en el Sahel: Una realidad persistente, pero evitable. CIDOB Notes Internacionals. vol. 252. junio. Available online: https://www.cidob.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/252_RAFAEL%20AGUIRRE%20UNCETA_CAST.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Alaminos Hervás, María Ángeles. 2021. Desarrollo político y económico en África: Sesenta años de transformación. Revista de Fomento Social 76: 249–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaminos Hervás, María Ángeles. 2022. El papel de China en el continente africano y su impacto global: Claves para comprender la «nueva era» de las relaciones sino-africanas. In China: El Desafío de la Nueva Potencia Global. Madrid: Cuadernos de Estrategia. Ministerio de Defensa, vol. 212, pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Alboan y Entreculturas. 2023. Invisibilizadas: Mujeres migrantes en el choque de fronteras. Available online: https://www.entreculturas.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/informe_invisibilizadas_-_entreculturas_y_alboan.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Aliaga-Sáez, Felipe, David Alberto García-Arango, Yvonne Riaño, Jovany Sepúlveda-Aguirre, and David Betancur-Betancur. 2025. Migrant Entrepreneurs Between Colombia and Germany: Return, Strategies, and Expectations. Social Sciences 14: 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita-Olmedo, Concepción. 2023. Gobernanza en el Sahel por actores armados no estatales: Un modelo teórico y aplicado. Revista Científica General José Maria de Covdova 21: 601–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita-Olmedo, Concepción, and Carolina Sampó. 2021. The case of migrant women from the Central American Northern Triangle: How to prevent exploitation and violence during the crossing. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 64: e005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asenjo, Rubén. 2024. Los datos de la pobreza extrema mundial. LISA News. October 18. Available online: https://www.lisanews.org/actualidad/los-datos-de-la-pobreza-extrema-mundial/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Asinde, Regina. 2018. Masivas protestas en Togo acorralan una dictadura de 50 años. El Salto. December 26. Available online: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/togo/masivas-protestas-togo-fin-50-anos-dictadura-faure-gnassingbe (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Aybar, Soraya. 2021. ¿Cuánto y qué emiten? El mapa de la energía en África. África Mundi. November 8. Available online: https://www.africamundi.es/p/la-energia-en-africa (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Bardin, Laurence. 1986. El Análisis de Contenido. Madrid: AKal. [Google Scholar]

- Bauloz, Céline, Marika Mcadam, and Joseph Teye. 2022. Trata de Personas en las Rutas Migratorias: Tendencias, Retos y Nuevas Formas de Cooperación. Informe sobre las Migraciones en el Mundo 2022. Ginebra: Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin, Cris, Marie-Laurence Flahaux, and Bruno Schoumaker. 2020. The sub-Saharan migration systems in times of policy restriction. Comparative Migration Studies 8: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelson, Bernard. 1952. Content Analysis in Communication Researches. III. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, Pablo. 2024. Migraciones en África. El caso de África Occidental y por qué no existe una “invasión” a Europa. Astrolabio Nueva Época 32: 158–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminando Fronteras. 2024. Derecho a la vida. Available online: https://observatoriodesigualdadandalucia.org/recursos/monitoreo-del-derecho-vida-2024 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Castel, Antoni. 2024. Unos datos acerca de las migraciones africanas. esÁfrica. November 13. Available online: https://www.esafrica.es/migraciones/unos-datos-acerca-de-las-migraciones-africanas/ (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Cengiz, Mahmut, and Demir Oguzhan Omer. 2022. How Hoteliers Act in the Form of Organized Crime in Human Trafficking: A Case Study from Turkey. Social Sciences 11: 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CESCE. 2020. Informe Riesgo País Liberia. Available online: https://www.cesce.es/documents/20122/352439/INFORME++LIBERIA+-+12+febrero+2020.pdf/1fac7246-2eb3-d422-a435-26052186de71?t=1606929630542 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- CESCE. 2024. Informe Riesgo País Costa de Marfil. Available online: https://www.cesce.es/es/w/riesgo-pais/riesgo-pais-costa-de-marfil (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Choi, Jieun, Mark Dutz, and Zainab Usman. 2020. The Future of Work in Africa: Harnessing the Potential of Digital Technologies for All. Africa Development Forum. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Noruego para Refugiados. 2023. La desatención es la nueva normalidad. Las crisis de desplazamiento más desatendidas de 2023. Available online: https://nrc.org.co/especiales/las-crisis-de-desplazamiento-mas-desatendidas-del-mundo-2023-2/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Dewey, Matías. 2017. La demanda de productos ilegales. Elementos para explicar los intercambios ilegales desde la perspectiva de la sociología económica. Papeles de Trabajo 11: 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Durez, Aymeric. 2020. El intervencionismo militar de Francia en África: Una europeización limitada (1960–2019). Foro Internacional 1: 5–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenga, Daniel, and Amandine Gnanguènon. 2024. Recalibrating Coastal West Africa’s Response to Violent Extremism. Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Africa Security Brief 43: 1–12. Available online: https://africacenter.org/publication/asb43en-recalibrating-multitiered-stabilization-strategy-coastal-west-africa-response-violent-extremism/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Emerson, Stephen, and Hussein Solomon. 2018. African Security in the Twenty-First Century: Challenges and Opportunities. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- EOM. 2024. Las rutas migratorias hacia España. Recorridos por tierra y mar a través de África (2022–2023). El Orden Mundial. Available online: https://elordenmundial.com/mapas-y-graficos/rutas-migratorias-espana/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- EUROPOL. 2024. Tackling threats, addressing challenges. Luxembourg: European Migrant Smuggling Centre. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. 2023. La inseguridad alimentaria y la malnutrición en África occidental y central se sitúan en su nivel más alto en 10 años a medida que la crisis se extiende a los Estados ribereños. FAO News. April 18. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/food-insecurity-and-malnutrition-in-west-and-central-africa-at-10-year-high-as-crisis-spreads-to-coastal-countries/es (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Finckenauer, James O. 2007. Mafia and Organized Crime, the Beginner’s Guide. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, Iole. 2024. The Great Amplifier? Climate Change, Irregular Migration. Social Sciences 13: 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FRONTEX. 2024. Annual Risk Analysis 2024/2025. European Border anda Coast Gurard Agency. Warsaw. Available online: https://www.frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annual_Risk_Analysis_2024-2025.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Fuente Cobo, Ignacio. 2025. Radiografía de la amenaza yihadista en el Sahel. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. Documento de Análisis. March 5. Available online: https://www.defensa.gob.es/documents/2073105/2392118/radiografia_de_la_amenaza_yihadista_en_el_sahel_2025_dieeea17.pdf/10ae0fa8-29b5-61b2-ee41-7bfb93f05138?t=1741090650026 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Fundación Alternativas. 2024. Informe África 2024: El pacto migratorio y de asilo europeo. Consecuencias para África. Available online: https://fundacionalternativas.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/DIGITAL_Informe_Africa_2024_V5.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Fundación Alternativas. 2025. Informe África 2025. África Occidental y Europa: Perspectivas. Available online: https://fundacionalternativas.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/WEB_Informe_Africa.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Garrido Guijarro, Óscar. 2024. Reinventando Wagner: Africa Corps llega al Sahel. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. Documento de Análisis, February nº 28. Available online: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_analisis/2024/DIEEEA14_2024_OSCGAR_Wagner.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Gericke, Kilian, Julia Kramer, and Celeste Roschuni. 2016. An exploratory study of the discovery and selection of design methods in practice. Journal of Mechanical Design 138: 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheyle, Niels, and Thomas Jacobs. 2017. Content Analysis: A short overview. Internal Research Note. Available online: https://spada.uns.ac.id/pluginfile.php/762754/mod_resource/content/2/20221031%20Niels%20Gheyle%20-%20T%20Jacobs%20-%20CONTENT%20ANALYSIS%20-%20A%20Short%20Overview.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. 2021. Índice Global del Crimen Organizado. Available online: https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/global-ocindex-report-spanish.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Gómez-Jordana Moya, Rafael. 2019. Entre dos orillas. Atalayar. Available online: https://www.atalayar.com/articulo/reportajes/africa-suicidio-demografico/20190912103903142334.html (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- González, Yoslán Silverio. 2016. Situación actual en Nigeria: Tendencias socioeconómicas y políticas más probables hacia el 2020. Contra Relatos desde el Sur 13: 109–26. Available online: https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/contra-relatos/article/view/15216 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- González Del Miño, Paloma, and Concepción Anguita-Olmedo. 2023. The (In)Coherence of European Migration Policy: Between Securitization and Protection. In Inmigrant Lives. Intersectionality, Transnationality, and Global Perspectives. Edited by Edward Shizha and Edward Makwarimba. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 228–47. [Google Scholar]

- Grupo del Banco Mundial. 2024. Conectando a millones de personas a la electricidad en África con la “Misión 300”. September 19. Available online: https://www.bancomundial.org/es/news/feature/2024/09/19/five-ways-the-world-bank-will-achieve-mission-300 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Hernando, Celia. 2024. Las rutas migratorias desde África hacia España. El Orden Mundial. September 4. Available online: https://elordenmundial.com/mapas-y-graficos/rutas-migratorias-espana/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Hirsch, Alan. 2024. Overcoming the North-South Divide in Global Migration Governance. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. November 20. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/11/international-migration-policy-global-north-south?lang=en (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- IEA, IRENA, UNSD, World Bank, and WHO. 2024. The Energy Progress Report. Tracking SDG 7. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- InAfrica. 2024. El crecimiento del sector minero en África. Available online: https://inafrica.es/crecimiento-sector-minero-africa/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Institute for Economics & Peace. 2025. Global Terrorism Index. Measuring The Impact of Terrorism. Available online: https://www.visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Global-Terrorism-Index-2025.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2023. Global Report on Internal Displacement 2023. Geneva: Norwegian Refugee Council. Available online: https://api.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/IDMC_GRID_2023_Global_Report_on_Internal_Displacement_LR.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2024. Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labour. Geneve: International Labour Organization (ILO). [Google Scholar]

- Interpol. 2022. África Occidental: Rescate de 56 menores víctimas de explotación. December 21. Available online: https://www.interpol.int/es/Noticias-y-acontecimientos/Noticias/2022/Africa-Occidental-rescate-de-56-menores-victimas-de-explotacion (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- IOM. 2023. New Regional Road Map to Strengthen Counter-Trafficking in West Africa. UN Migration News. May 4. Available online: https://www.iom.int/news/new-regional-road-map-strengthen-counter-trafficking-west-africa (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- IOM. 2024. World Migration Report. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. 2025. Missing Migrants Projetcs. Geneve: International Organization For Migration. [Google Scholar]

- Jaime González, Gabriel. 2024. La moneda, ¿reflejo de la reconfiguración geopolítica en África Occidental? Instituto de Estudios Estratégicos. Documento de Opinión. Marzo Nº 25. Available online: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_opinion/2024/DIEEEO25_2024_GABJAI_Africa.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Knott, Eleanor, Aliya Hamid Rao, Kate Summers, and Chana Teeger. 2022. Interviews in the social sciences. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorf, Klaus. 1968. Metodología de análisis de contenido. Teoría y práctica. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf, Klaus. 2019. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lazare Flan, Goualo. 2021. Movimientos sociales insurreccionales en África occidental: Una mirada retrospectiva a la rebelión armada en Costa de Marfil de 2002 a 2011. Oasis 35: 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Martínez, Alejandro. 2024. Mali, Níger y Burkina Faso: Redefiniendo alianzas en el panorama geopolítico de África Occidental. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. Documento de Opinión. Junio nº 68. Available online: https://www.ieee.es/Galerias/fichero/docs_opinion/2024/DIEEEO68_2024_ALELOP_Sahel.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- López Noguero, Fernando. 2002. El análisis de contenido como método de investigación. Editado por Universidad de Huelva. XXI Revista de Educación 4: 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mearsheimer, John J. 2001. The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Mesa, Beatriz. 2024. Migraciones y poder económico: Un análisis de actores y rutas. In Fundación Alternativas. Informe África 2024: El Pacto Migratorio y de Asilo Europeo. Consecuencias para África. Nº 5. pp. 37–55. Available online: https://fundacionalternativas.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/DIGITAL_Informe_Africa_2024_V5.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Mesa García, Beatriz. 2022. Los grupos armados del Sahel. Madrid: La Catarata. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan, Haradhan Kumar. 2020. Quantitative Research: A Successful Investigation in Natural and Social Sciences. Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People 9: 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosuro, Wuraola, Stefano De Cupis, Martín E. De Simone, Yevgeniya Savchenko, and Jason Weaver. 2021. Education as a Right for Children in Western and Central Africa. World Bank Blogs. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/education/education-right-children-western-and-central-africa (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Naciones Unidas. 2024. La carestía de alimentos azota África Occidental y Central. April 12. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2024/04/1529001 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Naciones Unidas. 2025. África sigue siendo el epicentro del terrorismo mundial. Noticias ONU. January 21. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2025/01/1535881 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- NATO. 2018. Illicit Trafficking in North Africa and Sahel (Quick Overview). Nato Strategic Direction South. Available online: https://humantraffickingsearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Illicit_trafficking_in_North_Africa_and_Sahel.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Nievas Bullejos, David, and Beatriz Mesa García. 2020. Los recursos naturales en el centro de la geopolítica en el Sahel. Editado por Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales de Puebla. TLA-MELAUA, Revista de Ciencias Sociales Nueva Época año 14: 295–314. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2009. Service Delivery in Fragile Situations: Key Concepts, Findings and Lessons. OECD Journal on Development 9.

- Page, Matthew T., and Abdul H. Wando. 2022. Halting the Kleptocratic Capture of Local Government in Nigeria. Working Paper. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online: https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/Page_Wando_NigeriaCorruption_final.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Pressenza IPA. 2025. Un réseau de trafiquants d’êtres humains a réduit en esclavage des dizaines de migrants en Afrique de l’Ouest en leur faisant de fausses promesses d’emploi au Canada. April 23. Available online: https://www.pressenza.com/fr/2025/04/un-reseau-de-trafiquants-detres-humains-a-reduit-en-esclavage-des-dizaines-de-migrants-en-afrique-de-louest-en-leur-faisant-de-fausses-promesses-demploi-au-canada/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Rana, Juwel, P. L. Luna Gutiérrez, and John Oldroyd. 2021. Quantitative Methods. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Edited by Ali Farazmad. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, Anne-Cécile. 2023. Las causas de la sucesión de golpes de Estado en África occidental. Malí, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Níger. Le Monde Diplomatique, September. [Google Scholar]

- Roulston, Kathryn, Kathleen deMarrais, and Jamie B. Lewis. 2003. Learning to Interview in the Social Sciences. Qualitative Inquiry 9: 643–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampó, Carolina. 2019. El tráfico de cocaína entre América Latina y África Occidental. URVIO: Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios de Seguridad 24: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Herráez, Pedro. 2025. El Sahel: ¿también epicentro de la reconfiguración global? In Panorama Geopolítico de los Conflictos 2024. Madrid: de Ministerio de Defensa, vol. 20, pp. 153–77. [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children. 2024. África Occidental y Central: Cerca de 10 millones de niñas y niños se quedan sin escuela por las inundaciones. October 15. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.es/actualidad/africa-occidental-y-central-cerca-de-10-millones-de-ninos-y-ninas-se-quedan-sin-escuelas (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Security Council Report. 2022. In Hindsight: The Security Council and Unconstitutional Changes of Government in Africa. Available online: https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/monthly-forecast/2022-07/in-hindsight-the-security-council-and-unconstitutional-changes-of-government-in-africa.php (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Segura Clavell, José. 2024. La brecha eléctrica de África. esÁfrica. July 10. Available online: https://www.esafrica.es/desarrollo/la-brecha-electrica-de-africa/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Setrana, Mary Boatemaa, Joseph K. Teye, Ebenezer G. A. Niloi, Edward Siedu, Charity Osei-Amponsah, and Emmanuel Yakass. 2025. Does Social Transformation Drive Out-Migration? Perceptions and Changes. Social Sciences 14: 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemag, Ben, and Mimi Mefo Takambou. 2023. Trata de personas, un peligro creciente en África. DW. July 28. Available online: https://www.dw.com/es/trata-de-personas-un-peligro-creciente-en-%C3%A1frica/a-66378330 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Skaperdas, Stergios. 2001. The political economy of organized crime: Providing protection when the state does not. Economics of Governance 2: 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbins, Robert A. 2001. Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences. Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc., vol. 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swissinfo.ch. 2024. Las economías africanas crecerán un 3.4% en 2024, pero no se reducirá la pobreza. April 8. Available online: https://www.swissinfo.ch/spa/las-econom%C3%ADas-africanas-crecer%C3%A1n-un-3%2C4-%25-en-2024%2C-pero-no-se-reducir%C3%A1-la-pobreza/75319604 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Tecnología Minera. 2021. El oro es el principal producto de exportación en 23 países de todo el mundo. Available online: https://tecnologiaminera.com/noticia/el-oro-es-el-principal-producto-de-exportacion-en-23-paises-de-todo-el-mundo-1606201979 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- The Fund for Peace. 2024. The Fragile States Index 2024: Annual Report—A World Adrift. Washington: The Fund for Peace. [Google Scholar]

- Tooze, Adam. 2024. La pobreza absoluta en África en la era de la policrisis. Sinpermiso. October 27. Available online: https://www.sinpermiso.info/textos/la-pobreza-absoluta-en-africa-en-la-era-de-la-policrisis (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Transparency International. 2024. Corruption Percepctions Index. Available online: https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/CPI2024_Report_Eng1.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- UN. 2023a. UN News. Global perspectives Human stories. Tráfico en el Sahel: Amordazar el comercio ilícito de armas. UN News. June 14. Available online: https://news.un.org/es/story/2023/06/1521867 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- UN. 2023b. Contrabando en el Sahel: La ruta de las armas, el gas y el oro. UN News. May 23. Available online: https://www.ungeneva.org/es/news-media/news/2023/05/81312/contrabando-en-el-sahel-la-ruta-de-las-armas-el-gas-y-el-oro (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- UN DESA. 2025. Data accessed via the Migration Data Portal. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- UNDP. 2025. Human Development Insights. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/country-insights#/ranks (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- UNHCR-ACNUR. 2024. Tendencias Globales. Desplazamiento Forzado en 2023. Copenhagen: UNHCR-ACNUR. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2024. International Migrant Stock. Population Division. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- United Nations Secretary-General. 2021. Press Conference at United Nations Headquarters. SG/SM/20993, 26 October 2021. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2021/sgsm20993.doc.htm (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- UNODC. 2018. Global Study on Smuggling of Migrants 2018. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. 2022. Smuggling of Migrants in the Sahel. TOCTA Sahel (Transnational Organized Crime Threat Assessment. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. 2024a. Impact of Transnational Organized Crime on Stability and Development in Sahel (Transnational Organized Crime Threat Assessment). Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. [Google Scholar]

- UNODC. 2024b. Global Report on Trafficking in Persons. Vienna: United Nations Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Muñoz, Alejandro, Paloma González-Gómez-del-Miño, and Nicolás Contreras-Barraza. 2025. The Determinants of Brain Drain and the Role of Citizenship in Skilled Migration. Social Sciences 14: 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WaterAid. 2021a. Regional State of hygiene—West Africa. Londres. Available online: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/es/publications/el-estado-de-higiene-en-africa-occidental (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- WaterAid. 2021b. Mission-critical: Invest in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for a Healthy and Green Economic Recovery. Available online: https://washmatters.wateraid.org/publications/mission-critical-invest-water-sanitation-hygiene-healthy-green-recovery (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Wolde, Sinafekesh, Paolo D’Odorico, and Maria Cristina Rulli. 2023. Environmental drivers of human migration in Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Sustainability 6: e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. 2024. The World Bank in Western and Central Africa. April 8. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/western-and-central-africa (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- World Bank Group. 2025a. Ores and Metals Exports (% of Merchandise Exports). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.MMTL.ZS.UN (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- World Bank Group. 2025b. World Bank Data. Available online: https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=ZH (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Yabi, Gilles O. 2024. Los desafíos entrelazados del Sahel. Fondo Monetario Internacional. September. Available online: https://www.imf.org/es/Publications/fandd/issues/2024/09/the-sahels-intertwined-challenges-yabi (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Zerpa de Kirby, Yubeira Beatriz. 2016. Lo cualitativo, sus métodos en las ciencias sociales. Sapienza Organizacional 3: 207–30. [Google Scholar]

| Country/Territory | ISO3 | Region | CPI 2024 Score | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cape Verde | CPV | SSA | 62 | 35 |

| Benin | BEN | SSA | 45 | 69 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | CIV | SSA | 45 | 69 |

| Senegal | SEN | SSA | 45 | 69 |

| Ghana | GHA | SSA | 42 | 80 |

| Burkina Faso | BFA | SSA | 41 | 82 |

| Gambia | GMB | SSA | 38 | 96 |

| Niger | NER | SSA | 34 | 107 |

| Sierra Leone | SLE | SSA | 33 | 114 |

| Togo | TGO | SSA | 32 | 121 |

| Mauritania | MRT | SSA | 30 | 130 |

| Guinea | GIN | SSA | 28 | 133 |

| Liberia | LBR | SSA | 27 | 135 |

| Mali | MLI | SSA | 27 | 135 |

| Nigeria | NGA | SSA | 26 | 140 |

| Guinea-Bissau | GNB | SSA | 21 | 158 |

| Country | Rank | HDI Value | Var. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cape Verde | 131 | 0.661 | −1 |

| Ghana | 145 | 0.602 | 1 |

| Nigeria | 161 | 0.548 | −1 |

| Togo | 163 | 0.547 | 3 |

| Mauritania | 164 | 0.54 | 0 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 166 | 0.534 | 0 |

| Senegal | 169 | 0.517 | −1 |

| Benin | 173 | 0.504 | 0 |

| Gambia | 174 | 0.495 | 0 |

| Liberia | 177 | 0.487 | 0 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 179 | 0.483 | 0 |

| Guinea | 181 | 0.471 | −1 |

| Sierra Leone | 184 | 0.458 | 0 |

| Burkina Faso | 185 | 0.438 | 0 |

| Mali | 188 | 0.41 | 0 |

| Niger | 189 | 0.394 | −1 |

| Nigeria | 161 | 0.548 | −1 |

| Countries | Population (millions) | Access to Electricity (%) | Basic Access to Hand Washing Facilities (%) | Basic Access to Drinking Water (%) | Open Defecation Practice (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | 13.35 | 57% | 11% | 66% | 54% |

| Burkina Faso | 22.67 | 19% | 12% | 48% | 47% |

| Cape Verde | 0.59 | 97% | Not available | 87% | 20% |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 22.70 | 69% | 19% | 73% | 26% |

| Gambia | 2.71 | 65% | 8% | 78% | 1% |

| Ghana | 33.48 | 85% | 41% | 81% | 18% |

| Guinea | 13.86 | 48% | 17% | 62% | 14% |

| Guinea-Bissau | 2.11 | 37% | Not available | 67% | 17% |

| Liberia | 5.3 | 32% | 1% | 73% | 40% |

| Mali | 22.59 | 53% | 52% | 78% | 7% |

| Mauritania | 4.74 | 49% | 43% | 71% | 32% |

| Niger | 26.21 | 20% | Not available | 50% | 68% |

| Nigeria | 218.54 | 61% | 42% | 71% | 20% |

| Senegal | 17.32 | 68% | 24% | 81% | 14% |

| Sierra Leone | 8.61 | 29% | 18% | 61% | 18% |

| Togo | 8.85 | 57% | 10% | 65% | 48% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anguita-Olmedo, C. The Convergence of Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in West Africa: Migration Pressure Factors and Criminal Actors. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080447

Anguita-Olmedo C. The Convergence of Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in West Africa: Migration Pressure Factors and Criminal Actors. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080447

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnguita-Olmedo, Concepción. 2025. "The Convergence of Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in West Africa: Migration Pressure Factors and Criminal Actors" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080447

APA StyleAnguita-Olmedo, C. (2025). The Convergence of Trafficking and Migrant Smuggling in West Africa: Migration Pressure Factors and Criminal Actors. Social Sciences, 14(8), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080447