Understanding Youth Violence Through a Socio-Ecological Lens

Abstract

1. Introduction

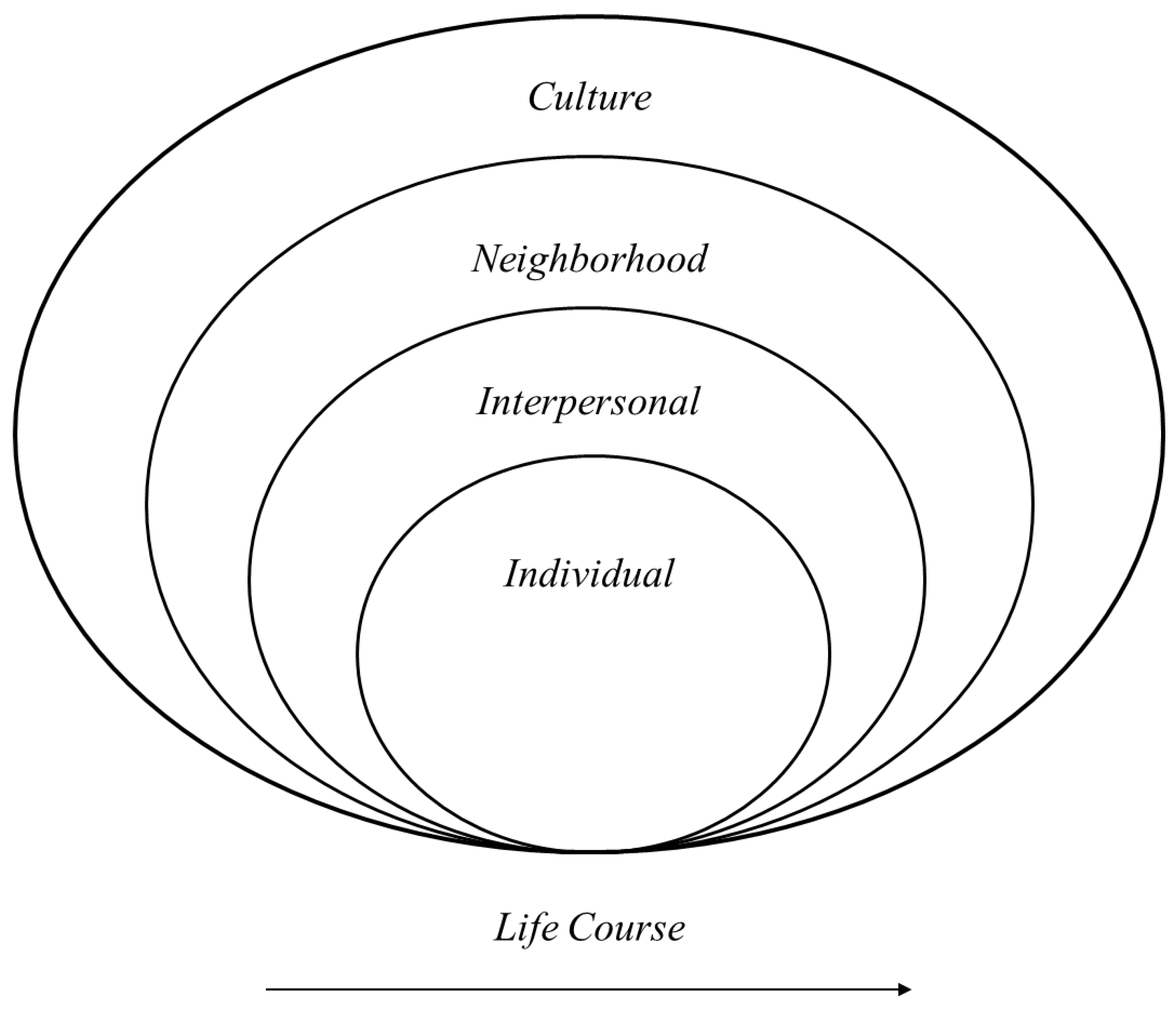

2. Socio-Ecological Approach

3. Individual

3.1. Adverse Childhood Experiences

3.2. Gender and Sex Differences

3.3. Psychopathology

3.4. Personality and Disposition

3.5. Biological Risks

4. Interpersonal

4.1. Family Socialization

4.2. Peers

4.3. Bullying

4.4. Gang Membership

4.5. Schools

5. Neighborhood

6. Culture

6.1. Radicalization

6.2. Media and Violence

7. Life Course

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aarten, Pauline G., and Marieke C. Liem. 2022. Homicide and mental disorder. In Clinical Forensic Psychology: Introductory Perspectives on Offending. Edited by Carlo Garofalo and Jelle J. Sijtsema. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 445–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, Robert. 1992. Foundation for a General Strain Theory of Crime and Delinquency. Criminology 30: 47–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Hafal (Haval). 2017. Youth De-Radicalization: A Canadian Framework. Journal for Deradicalization 12: 119–68. [Google Scholar]

- Aiello, Emilia, Lídia Puigvert, and Tinka Schubert. 2018. Preventing Violent Radicalization of Youth Through Dialogic Evidence-Based Policies. International Sociology 33: 435–53. [Google Scholar]

- Alleyne, Emma, and Jane L. Wood. 2010. Gang Involvement: Psychological and Behavioral Characteristics of Gang Members, Peripheral Youth, and Nongang Youth. Aggressive Behavior 36: 423–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Telma Catarina, Jorge Cardoso, Ana Francisca Matos, Ana Murça, and Olga Cunha. 2024. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Aggression in Adulthood: The Moderating Role of Positive Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect 154: 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, Paul R. 2001. Children of Divorce in the 1990s: An Update of the Amato and Keith (1991) Meta-Analysis. Journal of Family Psychology 15: 355–70. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017. Role Models and Children. Available online: https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-and-Role-Models-099.aspx (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Appelbaum, Paul S. 2013. Public Safety, Mental Disorders, and Guns. JAMA Psychiatry 70: 565–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astor, Ron Avi, Pedro Noguera, Edward Fergus, Vivian Gadsden, and Rami Benbenishty. 2021. A Call for the Conceptual Integration of Opportunity Structures Within School Safety Research. School Psychology Review 50: 172–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, Ronet, and Robert Peralta. 2002. The Relationship Between Drinking and Violence in an Adolescent Population: Does Gender Matter? Deviant Behavior 23: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivio, Michael T., and Nathan Epps. 2016. The Interrelatedness of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among High-Risk Juvenile Offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 14: 179–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidawi, Susan, Nina Papalia, and Rebecca Featherston. 2023. Gender Differences in the Maltreatment-Youth Offending Relationship: A Scoping Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24: 1140–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bastug, Mehmet F., Aziz Douai, and Davut Akca. 2020. Exploring the “Demand Side” of Online Radicalization: Evidence from the Canadian Context. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 43: 616–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugut, Philip, and Katharina Neumann. 2020. Online Propaganda Use During Islamist Radicalization. Information, Communication & Society 23: 1570–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Aranda, Nazaret, Lourdes Contreras, and M. Carmen Cano-Lozano. 2023. Exposure to Violence During Childhood and Child-To-Parent Violence: The Mediating Role of Moral Disengagement. Healthcare 11: 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellair, Paul E., and Thomas L. McNulty. 2009. Gang Membership, Drug Selling, and Violence in Neighborhood Context. Justice Quarterly 26: 644–69. [Google Scholar]

- Benarous, Xavier, Chloé Lefebvre, Jean-Marc Guilé, Angèle Consoli, Cora Cravero, David Cohen, and Hélène Lahaye. 2024. Effects of Neurodevelopmental Disorders on the Clinical Presentations and Therapeutic Outcomes of Children and Adolescents with Severe Mood Disorders: A Multicenter Observational Study. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbouriche, Massil, and Olivier Vanderstukken. 2019. Violence-supportive cognition and implicit theories in aggressive and violent behaviors: Implications for violent extremism. In Evidence-Based Work with Violent Extremists: International Implications of French Terrorist Attacks and Responses. Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, Karen L., and Rebecca A. Slotkin. 2023. The aggressive-disruptive child and school outcomes. In Handbook of Anger, Aggression, and Violence. Edited by Colin R. Martin, Victor R. Preedy and Vinood B. Patel. Cham: Springer, pp. 1301–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman-Grieve, Lorraine. 2009. Exploring “Stormfront”: A Virtual Community of the Radical Right. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 32: 989–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, Anthony A., Andrew V. Papachristos, and David M. Hureau. 2010. The Concentration and Stability of Gun Violence at Micro Places in Boston, 1980–2008. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 26: 33–53. [Google Scholar]

- Branas, Charles C., Eugenia South, Michelle C. Kondo, Bernadette C. Hohl, Philippe Bourgois, Douglas J. Wiebe, and John M. MacDonald. 2018. Citywide Cluster Randomized Trial to Restore Blighted Vacant Land and Its Effects on Violence, Crime, and Fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115: 2946–51. [Google Scholar]

- Brantingham, P. Jeffrey, George E. Tita, Martin B. Short, and Shannon E. Reid. 2012. The Ecology of Gang Territorial Boundaries. Criminology 50: 851–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, Charlotte Lyn, Paul Sacco, Karen M. Kolivoski, Laura M. Stapleton, Hyun-Jin Jun, and Darnell Morris-Compton. 2017. Gender Differences in Patterns of Substance Use and Delinquency: A Latent Transition Analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse 26: 162–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broidy, Lisa M., Anna L. Stewart, Carleen M. Thompson, April Chrzanowski, Troy Allard, and Susan M. Dennison. 2015. Life Course Offending Pathways Across Gender and Race/Ethnicity. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology 1: 118–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1977. Toward An Experimental Ecology of Human Development. American Psychologist 32: 513–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1986. Ecology of the Family as a Context for Human Development: Research Perspectives. Developmental Psychology 22: 723–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1994. Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Torsten Husén and Thomas Neville Postlethwaite. Oxford: Elsevier, vol. 3, pp. 1643–47. [Google Scholar]

- Buker, Hasan. 2011. Formation of Self-Control: Gottfredson and Hirschi’s General Theory of Crime and Beyond. Aggression and Violent Behavior 16: 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2023. Drug and Alcohol Use Reported by Youth in Juvenile Facilities, 2008–2018—Statistical Tables. Available online: https://bjs.ojp.gov/press-release/drug-and-alcohol-use-reported-youth-juvenile-facilities-2008-2018-statistical-tables (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Bursik, Robert J., Jr., and Harold G. Grasmick. 1993. Neighborhoods and Crime: The Dimensions of Effective Community Control. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, S. Alexandra. 2022. The Genetic, Environmental, and Cultural Forces Influencing Youth Antisocial Behavior are Tightly Intertwined. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 18: 155–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Alexandra, Ashlee R. Barnes, Matt McGue, and William G. Iacono. 2008. Parental Divorce and Adolescent Delinquency: Ruling Out the Impact of Common Genes. Developmental Psychology 44: 1668–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, Brad J., Katherine Newman, Sandra L. Calvert, Geraldine Downey, Mark Dredze, Michael Gottfredson, Nina G. Jablonski, Ann S. Masten, Calvin Morrill, Daniel B. Neill, Daniel Romer, and Daniel W. Webster. 2016. Youth Violence: What We Know and What We Need to Know. American Psychologist 71: 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, Amy L., and Stephen B. Manuck. 2014. MAOA, Childhood Maltreatment, and Antisocial Behavior: Meta-Analysis of a Gene-Environment Interaction. Biological Psychiatry 75: 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantuaria, Manuella Lech, Jørgen Brandt, and Victoria Blanes-Vidal. 2023. Exposure to Multiple Environmental Stressors, Emotional and Physical Well-Being, and Self-Rated Health: An Analysis of Relationships Using Latent Variable Structural Equation Modelling. Environmental Research 227: 115770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, Tara, and Bronwyn Myers. 2012. Effectiveness of Early Interventions for Substance-Using Adolescents: Findings from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 7: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, Sarah L., Kelly L. Klump, and S. Alexandra Burt. 2023. Understanding the Effects of Neighborhood Disadvantage on Youth Psychopathology. Psychological Medicine 53: 3036–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024a. About Youth Violence. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/youth-violence/about/index.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024b. About Violence Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violence-prevention/about/index.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024c. Key Findings: School-Associated Violent Death Study. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/youth-violence/data-research/school-associatedviolentdeathstudy/index.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Chen, Hsin-Yung, Ling-Fu Meng, Yawen Yu, Chen-Chi Chen, Li-Yu Hung, Shih-Che Lin, and Huang-Ju Chi. 2021. Developmental Traits of Impulse Control Behavior in School Children Under Controlled Attention, Motor Function, and Perception. Children 8: 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesney-Lind, Meda. 2006. Patriarchy, Crime, and Justice: Feminist Criminology in an Era of Backlash. Feminist Criminology 1: 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, Dante, and Fred A. Rogosch. 2012. Neuroendocrine Regulation and Emotional Adaptation in the Context of Child Maltreatment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 77: 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, Matteo, Gianmarco De Francisci Morales, Alessandro Galeazzi, Walter Quattrociocchi, and Michele Starnini. 2021. The Echo Chamber Effect on Social Media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118: e2023301118. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Lauren W., Timonthy J. Landrum, and Chris A. Sweigart. 2020. Extreme School Violence and Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: (How) Do They Intersect? Education and Treatment of Children 43: 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, Dewey, and Francis Huang. 2016. Authoritative School Climate and High School Student Risk Behavior: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Level Analysis of Student Self-Reports. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45: 2246–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, Dewey G., Matthew J. Mayer, and Michael L. Sulkowski. 2021. History and Future of School Safety Research. School Psychology Review 50: 143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, Emily, Paul Gill, and Oliver Mason. 2016. Mental Health Disorders and the Terrorist: A Research Note Probing Selection Effects and Disorder Prevalence. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39: 560–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daspe, Marie-Ève, Reout Arbel, Michelle C. Ramos, Lauren A. S. Shapiro, and Gayla Margolin. 2019. Deviant Peers and Adolescent Risky Behaviors: The Protective Effect of Nonverbal Display of Parental Warmth. Journal of Research on Adolescence 29: 863–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David-Ferdon, Corinne, Alana M. Vivolo-Kantor, Linda L. Dahlberg, Khiya J. Marshall, Neil Rainford, and Jefferey E. Hall. 2016. A Comprehensive Technical Package for the Prevention of Youth Violence and Associated Risk Behaviors. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Dechesne, Mark. 2011. Deradicalization: Not Soft, but Strategic. Crime, Law and Social Change 55: 287–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dembo, Richard, Julie M. Krupa, Jessica Faber, Ralph J. DiClemente, Jennifer Wareham, and James Schmeidler. 2021. An Examination of Gender Differences in Bullying Among Justice-Involved Adolescents. Deviant Behavior 42: 268–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devers, Lindsey. 2011. Desistance and Developmental Life Course Theories: Research Summary. Available online: https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/media/document/desistanceresearchsummary.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Diamond, Catherine, and Nicholas Freudenberg. 2016. Community Schools: A Public Health Opportunity to Reverse Urban Cycles of Disadvantage. Journal of Urban Health 93: 923–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierkhising, Carly B., Susan J. Ko, Briana Woods-Jaeger, Ernestine C. Briggs, Robert Lee, and Robert S. Pynoos. 2013. Trauma Histories Among Justice-Involved Youth: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 4: 20274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Beidi, and Marvin D. Krohn. 2016. Dual Trajectories of Gang Affiliation and Delinquent Peer Association During Adolescence: An Examination of Long-Term Offending Outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45: 746–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Yifei, and Meng Zhang. 2025. Longitudinal Reciprocal Relationship Between Media Violence Exposure and Aggression Among Junior High School Students in China: A Cross-Lagged Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1441738. [Google Scholar]

- Duah, Ebenezer. 2023. Bullying Victimization and Juvenile Delinquency in Ghanaian Schools: The Moderating Effect of Social Support. Adolescents 3: 228–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, Naomi N., Sandra L. Pettingell, Barbara J. McMorris, and Iris W. Borowsky. 2010. Adolescent Violence Perpetration: Associations with Multiple Types of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Pediatrics 125: e778–e786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, Joseph A., Roger P. Weissberg, Allison B. Dymnicki, Rebecca D. Taylor, and Kriston B. Schellinger. 2011. The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Development 82: 405–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duron, Jacquelynn F., Abigail Williams-Butler, Feng-Yi Y. Liu, Danielle Nesi, Kathleen Pirozzolo Fay, and Bo-Kyung Elizabeth Kim. 2021. The Influence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) on the Functional Impairment of Justice-Involved Adolescents: A Comparison of Baseline to Follow-Up Reports of Adversity. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 19: 384–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrmann, Samantha, Nina Hyland, and Charles Puzzanchera. 2019. Girls in the Juvenile Justice System. National Report Series Bulletin. Laurel: U.S. Department of Justice. Available online: https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/251486.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Ellison, Carlyn, Linda Struckmeyer, Mahshad Kazem-Zadeh, Nichole Campbell, Sherry Ahrentzen, and Sherrilene Classen. 2021. A Social-Ecological Approach to Identify Facilitators and Barriers of Home Modifications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 8720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaesser, Caitlin, Desmond Upton Patton, Emily Weinstein, Jacquelyn Santiago, Ayesha Clarke, and Rob Eschmann. 2021. Small Becomes Big, Fast: Adolescent Perceptions of How Social Media Features Escalate Online Conflict to Offline Violence. Children and Youth Services Review 122: 105898. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage, Dorothy L., Sabina Low, Joshua R. Polanin, and Eric C. Brown. 2013. The Impact of a Middle School Program to Reduce Aggression, Victimization, and Sexual Violence. The Journal of Adolescent Health 53: 180–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, Graeme, David J. Hawes, Paul J. Frick, William E. Copeland, Candice L. Odgers, Barbara Franke, Christine M. Freitag, and Stephane A. De Brito. 2019. Conduct Disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 5: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, Thomas W., Jill V. Hamm, Man-Chi Leung, Kerrylin Lambert, and Maggie Gravelle. 2011. Early Adolescent Peer Ecologies in Rural Communities: Bullying in Schools that Do and Do Not Have a Transition During the Middle Grades. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 40: 1106–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddes, Allard R., Liesbeth Mann, and Bertjan Doosje. 2015. Increasing Self-Esteem and Empathy to Prevent Violent Radicalization: A Longitudinal Quantitative Evaluation of a Resilience Training Focused on Adolescents with a Dual Identity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 45: 400–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fenta, Eneyew Talie, Misganaw Guadie Tiruneh, and Tadele Fentabil Anagaw. 2023. Exploring Enablers and Barriers of Healthy Dietary Behavior Based on the Socio-Ecological Model: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements 15: 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, David M., Frank Vitaro, Brigitte Wanner, and Mara Brendgen. 2007. Protective and Compensatory Factors Mitigating the Influence of Deviant Friends on Delinquent Behaviours During Early Adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 30: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Tiago, Marisa Matias, Helena Carvalho, and Paula Mena Matos. 2024. Parent-Partner and Parent-Child Attachment: Links to Children’s Emotion Regulation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 91: 101617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Bryanna Hahn, Nicholas Perez, Elizabeth Cass, Michael T. Baglivio, and Nathan Epps. 2015. Trauma Changes Everything: Examining the Relationship Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Serious, Violent, and Chronic Juvenile Offenders. Child Abuse & Neglect 46: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, Uberto, Richard E. Tremblay, Frank Vitaro, and Pierre McDuff. 2005. Youth Gangs, Delinquency and Drug Use: A Test of the Selection, Facilitation, and Enhancement Hypotheses. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46: 1178–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, Amanda, Irwin Garfinkel, Carey E. Cooper, and Ronald B. Mincy. 2009. Parental Incarceration and Child Wellbeing: Implications for Urban Families. Social Science Quarterly 90: 1186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, Amanda, Jeffrey Fagan, Tom Tyler, and Bruce G. Link. 2014. Aggressive Policing and the Mental Health of Young Urban Men. American Journal of Public Health 104: 2321–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, Douglas A., and Brad J. Bushman. 2012. Reassessing Media Violence Effects Using a Risk and Resilience Approach to Understanding Aggression. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 1: 138. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbner, George. 1998. Cultivation Analysis: An Overview. Mass Communication and Society 1: 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gereluk, Dianne. 2023. A Whole-School Approach to Address Youth Radicalization. Educational Theory 73: 434–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Paul, Caitlin Clemmow, Florian Hetzel, Bettina Rottweiler, Nadine Salman, Isabelle Van Der Vegt, Zoe Marchment, Sandy Schumann, Sanaz Zolghadriha, Norah Schulten, and et al. 2021. Systematic Review of Mental Health Problems and Violent Extremism. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 32: 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glackin, Erin, and Sarah A. O. Gray. 2016. Violence in Context: Embracing an Ecological Approach to Violent Media Exposure. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 16: 425–28. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Glowacz, Fabienne, Marie-Hélène Véronneau, Sylvie Boët, and Michel Born. 2013. Finding the Roots of Adolescent Aggressive Behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development 37: 319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, Paul J. 1985. The Drugs/Violence Nexus: A Tripartite Conceptual Framework. Journal of Drug Issues 15: 493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson, Dennis, Amanda Brown Cross, Denise Wilson, Melissa Rorie, and Nadine Connell. 2010. Effects of Participation in After-School Programs for Middle School Students: A Randomized Trial. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 3: 282–313. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson, Dennis C., Stephanie A. Gerstenblith, David A. Soulé, Shannon C. Womer, and Shaoli Lu. 2004. Do After School Programs Reduce Delinquency? Prevention Science 5: 253–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottfredson, Michael, and Travis Hirschi. 1990. A General Theory of Crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Anne, Dewey Cornell, Xitao Fan, Peter Sheras, Tse-Hua Shih, and Francis Huang. 2010. Authoritative School Discipline: High School Practices Associated with Lower Bullying and Victimization. Journal of Educational Psychology 102: 483–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, Syeda Tonima, and Meda Chesney-Lind. 2020. Female “deviance” and pathways to criminalization in different nations. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, Lindsay, Ron Tamborini, Sujay Prabhu, Clare Grall, Eric Novotny, and Brian Klebig. 2022. Narrative Media’s Emphasis on Distinct Moral Intuitions Alters Early Adolescents’ Judgments. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Application 34: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Kathryn, Oliver Perra, Julie-Ann Jordan, Tara O’Neill, and Mark McCann. 2020. School Bonding and Ethos in Trajectories of Offending: Results from the Belfast Youth Development Study. British Journal of Educational Psychology 90: 424–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, N. Zoe, Elke Ham, and Michelle M. Green. 2017. The Roles of Antisociality and Neurodevelopmental Problems in Criminal Violence and Clinical Outcomes Among Male Forensic Inpatients. Criminal Justice and Behavior 45: 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, Sameer, and Justin W. Patchin. 2009. Bullying Beyond the Schoolyard: Preventing and Responding to Cyberbullying. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnant, J. Benjamin, and Alissa B. Forman-Alberti. 2019. Deviant Peer Behavior and Adolescent Delinquency: Protective Effects of Inhibitory Control, Planning, or Decision Making? Journal of Research on Adolescence 29: 682–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, Travis. 1969. Causes of Delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve, Machteld, Judith Semon Dubas, Veroni I. Eichelsheim, Peter H. van der Laan, Wilma Smeenk, and Jan R. M. Gerris. 2009. The Relationship Between Parenting and Delinquency: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 37: 749–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmer, Georgia. 2013. Countering Violent Extremism: A Peacebuilding Perspective. Washington, DC: US Institute of Peace. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, James C. 2010. Gang Prevention: An Overview of Research and Programs. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/231116.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Huesmann, L. Rowell. 2007. The Impact of Electronic Media Violence: Scientific Theory and Research. Journal of Adolescent Health 41: S6–S13. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Jan N., and Myung H. Im. 2016. Teacher–Student Relationship and Peer Disliking and Liking Across Grades 1–4. Child Development 87: 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, Dia. 2021. Leveraging MTSS to Ensure Equitable Outcomes. Center on Multi-Tiered System of Supports at the American Institutes for Research. Available online: https://mtss4success.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/MTSS_Equity_Brief.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Jackson, Dylan B., Chantal Fahmy, Michael G. Vaughn, and Alexander Testa. 2019. Police Stops Among At-Risk Youth: Repercussions for Mental Health. Journal of Adolescent Health 65: 627–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Dylan B., Melissa S. Jones, Daniel C. Semenza, and Alexander Testa. 2023. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adolescent Delinquency: A Theoretically Informed Investigation of Mediators During Middle Childhood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, Bryant T. 2007. Understanding Immigration and Psychological Development. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 5: 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Se-Hoon, Hyunyi Cho, and Yoori Hwang. 2012. Media Literacy Interventions: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Communication 62: 454–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, Darrick, David P. Farrington, Alex R. Piquero, John F. MacLeod, and Steven van de Weijer. 2017. Prevalence of Life-Course-Persistent, Adolescence-Limited, and Late-Onset Offenders: A Systematic Review of Prospective Longitudinal Studies. Aggression and Violent Behavior 33: 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Melissa S., Cashen M. Boccio, Daniel C. Semenza, and Dylan B. Jackson. 2023. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adolescent Handgun Carrying. Journal of Criminal Justice 89: 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Florian, Dietrich Oberwittler, Heleen J. Janssen, and Lesa Hoffman. 2025. Exploring Heterogeneous Effects of Victimization on Changes in Fear of Crime: The Moderating Role of Neighborhood Conditions. Justice Quarterly 42: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, Jonathan, Jens F. Binder, and Christopher Baker-Beall. 2023. Online Radicalization: Profile and Risk Analysis of Individuals Convicted of Extremist Offences. Legal and Criminological Psychology 28: 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, Atika, Amy Bleakley, Morgan E. Ellithorpe, Michael Hennessy, Patrick E. Jamieson, and Ilana Weitz. 2019. Sensation Seeking and Impulsivity Can Increase Exposure to Risky Media and Moderate Its Effects on Adolescent Risk Behaviors. Prevention Science 20: 776–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilanowski, Jill F. 2017. Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model. Journal of Agromedicine 22: 295–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, Michael, and Donald M. Taylor. 2011. The Radicalization of Homegrown Jihadists: A Review of Theoretical Models and Social Psychological Evidence. Terrorism and Political Violence 23: 602–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolla, Nathan J., and Marco Bortolato. 2020. The Role of Monoamine Oxidase A in the Neurobiology of Aggressive, Antisocial, and Violent Behavior: A Tale of Mice and Men. Progress in Neurobiology 194: 101875. [Google Scholar]

- Laub, John H., and Robert J. Sampson. 1993. Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leban, Lindsay, and Delilah J. Delacruz. 2023. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Delinquency: Does Age of Assessment Matter? Journal of Criminal Justice 86: 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jungup, Mijin Choi, Margaret M. Holland, Melissa Radey, and Stephen J. Tripodi. 2022. Childhood Bullying Victimization, Substance Use, and Criminal Activity Among Adolescents: A Multi-level Growth Model Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippard, Elizabeth T. C., and Charles B. Nemeroff. 2020. The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry 177: 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwiller, Brett J., and Amy M. Brausch. 2013. Cyber Bullying and Physical Bullying in Adolescent Suicide: The Role of Violent Behavior and Substance Use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42: 675–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Jianghong, Gary Lewis, and Lois Evans. 2013. Understanding Aggressive Behaviour Across the Lifespan. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 20: 156–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, Friedrich, and David P. Farrington. 2012. Direct Protective and Buffering Protective Factors in the Development of Youth Violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 43: S8–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, Penny, Jonathan Gao, Bernard Tang, Chou Chuen Yu, Khalid Abdul Jabbar, James Alvin Low, and Pradeep Paul George. 2022. A Social Ecological Approach to Identify the Barriers and Facilitators to COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance: A Scoping Review. PLoS ONE 17: e0272642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupien, Sonia J., Robert-Paul Juster, Catherine Raymond, and Marie-France Marin. 2018. The Effects of Chronic Stress on the Human Brain: From Neurotoxicity, to Vulnerability, to Opportunity. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 49: 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, Alastair. 2018. Gangs and Adolescent Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 12: 411–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire-Jack, Kathryn, Susan Yoon, and Sunghyun Hong. 2022. Social Cohesion and Informal Social Control as Mediators Between Neighborhood Poverty and Child Maltreatment. Child Maltreatment 27: 334–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, Sara, Kelli A. Komro, Melvin D. Livingston, Otto Lenhart, and Alexander C. Wagenaar. 2017. Effects of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credit Laws in the US on Maternal Health Behaviors and Infant Health Outcomes. Social Science & Medicine 194: 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Escudero, Jose Antonio, Sonia Villarejo, Oscar F. Garcia, and Fernanda Garcia. 2020. Parental Socialization and Its Impact Across the Lifespan. Behavioral Sciences 10: 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matjasko, Jennifer L., Kristin M. Holland, Melissa K. Holt, Dorothy L. Espelage, and Brian W. Koenig. 2019. All Things in Moderation? Threshold Effects in Adolescent Extracurricular Participation Intensity and Behavioral Problems. Journal of School Health 89: 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Matthew J., Amanda B. Nickerson, and Shane R. Jimerson. 2021. Preventing School Violence and Promoting School Safety: Contemporary Scholarship Advancing Science, Practice, and Policy. School Psychology Review 50: 131–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, Brittany A., Kathleen J. Porter, Wen You, Maryam Yuhas, Annie L. Reid, Esther J. Thatcher, and Jamie M. Zoellner. 2021. Applying the Socio-Ecological Model to Understand Factors Associated with Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Behaviours Among Rural Appalachian Adolescents. Public Health Nutrition 24: 3242–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, Eamon, Stephanie A. De Brito, and Essi Viding. 2012. The Link Between Child Abuse and Psychopathology: A Review of Neurobiological and Genetic Research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 105: 151–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerschmidt, James W. 2005. Men, masculinities, and crime. In Handbook of Studies on Men & Masculinities. Edited by Michael Kimmel, Jeff Hearn and Robert W. Connel. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 196–212. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Allison D. 2018. Community Cohesion and Countering Violent Extremism: Interfaith Activism and Policing Methods in Metro Detroit. Journal for Deradicalization 15: 197–233. [Google Scholar]

- Milojevich, Helen M., and Mary E. Haskett. 2018. Longitudinal Associations Between Physically Abusive Parents’ Emotional Expressiveness and Children’s Self-Regulation. Child Abuse & Neglect 77: 144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, Terrie E. 1993. Adolescence-Limited and Life-Course-Persistent Antisocial Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy. Psychological Review 100: 674–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Sophie E., Rosana E. Norman, Shuichi Suetani, Hannah J. Thomas, Peter D. Sly, and James G. Scott. 2017. Consequences of Bullying Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry 7: 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, Amanda S., Michael M. Criss, Jennifer S. Silk, and Benjamin J. Houltberg. 2017. The Impact of Parenting on Emotion Regulation During Childhood and Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives 11: 233–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Joseph, and David P. Farrington. 2005. Parental Imprisonment: Effects on Boys’ Antisocial Behaviour and Delinquency Through the Life-Course. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46: 1269–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Threat Assessment Center. 2019. Protecting America’s Schools: A U.S. Secret Service Analysis of Targeted School Violence. Washington, DC: U.S. Secret Service, Department of Homeland Security. Available online: https://www.secretservice.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/Protecting_Americas_Schools.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Ohri-Vachaspati, Punam, Derek DeLia, Robin S. DeWeese, Noe C. Crespo, Michael Todd, and Michael J. Yedidia. 2015. The Relative Contribution of Layers of the Social Ecological Model to Childhood Obesity. Public Health Nutrition 18: 2055–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Yok-Fong. 2013. Working with Immigrant Children and Their Families: An Application of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 23: 954–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Zhongzhe, Derek A. Chapman, Terri N. Sullivan, Diane L. Bishop, and April D. Kimmel. 2024. Healthy Communities for Youth: A Cost Analysis of a Community-Level Program to Prevent Youth Violence. Prevention Science 25: 1133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulos, Nikolaos, and Maria Drossinou-Korea. 2020. Bronfenbrenner’s Theory and Teaching Intervention: The Case of a Student with Intellectual Disability. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies 16: 537–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Elizabeth M., Likang Xu, Ashley D’Inverno, Tadesse Haileyesus, and Cora Peterson. 2024. The Health and Economic Impact of Youth Violence by Injury Mechanism. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 66: 894–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patchin, Justin W., and Sameer Hinduja. 2011. Traditional and Nontraditional Bullying Among Youth: A Test of General Strain Theory. Youth & Society 43: 727–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Gerald R. 1982. Coercive Family Process. Eugene, OR: Castalia. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Hao, Yun Zhu, Eric Strachan, Emily Fowler, Tamara Bacus, Peter Roy-Byrne, Jack Goldberg, Viola Vaccarino, and Jinying Zhao. 2018. Childhood Trauma, DNA Methylation of Stress-Related Genes, and Depression: Findings from Two Monozygotic Twin Studies. Psychosomatic Medicine 80: 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, Robert L., and J. Michael Cruz. 2005. Conferring Meaning onto Alcohol-Related Violence: An Analysis of Alcohol Use and Gender in a Sample of College Youth. The Journal of Men’s Studies 14: 109–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perino, Michael T., Chad M. Sylvester, Cynthia E. Rogers, Joan L. Luby, and Deanna M. Barch. 2025. Neighborhood Resource Deprivation as a Predictor of Bullying Perpetration and Resource-Driven Conduct Symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 64: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchak, Nicolo P., and Raymond R. Swisher. 2022. Neighborhoods, Schools, and Adolescent Violence: Ecological Relative Deprivation, Disadvantage Saturation, or Cumulative Disadvantage? Journal of Youth and Adolescence 51: 261–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, Samantha L., Terrence Z. Huit, and David J. Hansen. 2016. Applying Ecological Systems Theory to Sexual Revictimization of Youth: A Review with Implications for Research and Practice. Aggression and Violent Behavior 26: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, Christopher J., and Karen L. Bierman. 2013. The Multifaceted Impact of Peer Relations on Aggressive–Disruptive Behavior in Early Elementary School. Developmental Psychology 49: 1174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, Salsa Della Guitara, Eko Priyo Purnomo, and Tiara Khairunissa. 2024. Echo Chambers and Algorithmic Bias: The Homogenization of Online Culture in a Smart Society. SHS Web of Conferences 202: 05001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raniti, Monika, Divyangana Rakesh, George C. Patton, and Susan M. Sawyer. 2022. The Role of School Connectedness in the Prevention of Youth Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review with Youth Consultation. BMC Public Health 22: 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengifo, Andres F. 2009. Social disorganization. In Oxford Bibliographies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Louis, and Ralph Scott. 2016. Digital Citizenship Cover—Demos. Available online: https://demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Digital-Citizenship-web-1.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Richard, Lucie, Lise Gauvin, and Kim Raine. 2011. Ecological Models Revisited: Their Uses and Evolution in Health Promotion Over Two Decades. Annual Review of Public Health 32: 307–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, Victor M., and Mario M. Galicia. 2013. Smoking Guns or Smoke & Mirrors? Schools and the Policing of Latino Boys. Association of Mexican American Educators Journal 7: 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Roorda, Debora L., Helma M. Y. Koomen, Jantine L. Spilt, and Frans J. Oort. 2011. The Influence of Affective Teacher–Student Relationships on Students’ School Engagement and Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Review of Educational Research 81: 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Wright, Christopher P., Jennifer M. Reingle Gonzalez, Michael G. Vaughn, Seth J. Schwartz, and Katelyn K. Jetelina. 2016. Age-Related Changes in the Relationship Between Alcohol Use and Violence from Early Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Addictive Behaviors Reports 4: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, Robert J., and John H. Laub. 2003. Life-Course Desisters? Trajectories of Crime Among Delinquent Boys Followed to Age 70. Criminology 41: 555–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, Robert J., Stephen W. Raudenbush, and Felton Earls. 1997. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. Science 277: 918–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, Samiullah. 2016. Influence of Parenting Style on Children’s Behaviour. Journal of Education and Educational Development 3. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2882540.

- Scharrer, Erica. 2005. Sixth Graders Take on Television: Media Literacy and Critical Attitudes of Television Violence. Communication Research Reports 22: 325–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, Christine S., and L. Thomas Winfree, Jr. 2010. Akers, Ronald L.: Social learning theory. In Encyclopedia of Criminological Theory. Edited by Francis T. Cullen and Pamela Wilcox. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., vol. 2, pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, Patrick, and Jacob W. Faber. 2014. Where, When, Why, and for Whom do Residential Contexts Matter? Moving Away from the Dichotomous Understanding of Neighborhood Effects. Annual Review of Sociology 40: 559–79. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Clifford R., and Henry D. McKay. 1942. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Clifford R., and Henry D. McKay. 1969. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas: A Study of Rates of Delinquency in Relation to Differential Characteristics of Local Communities in American Cities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Carla Sofia, and Maria Manuela Calheiros. 2020. Maltreatment Experiences and Psychopathology in Children and Adolescents: The Intervening Role of Domain-Specific Self-Representations Moderated by Age. Child Abuse & Neglect 99: 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitnick, Stephanie L., Daniel S. Shaw, Chelsea M. Weaver, Elizabeth C. Shelleby, Daniel E. Choe, Julia D. Reuben, Mary Gilliam, Emily B. Winslow, and Lindsay Taraban. 2017. Early Childhood Predictors of Severe Youth Violence in Low-Income Male Adolescents. Child Development 88: 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, James J., and Gerald R. Patterson. 1995. Individual Differences in Social Aggression: A Test of a Reinforcement Model of Socialization in the Natural Environment. Behavior Therapy 26: 371–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, Daniel. 1996. Translating Social Ecological Theory into Guidelines for Community Health Promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion 10: 282–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Teague, Rosie, Paul Mazerolle, Margot Legosz, and Jennifer Sanderson. 2008. Linking Childhood Exposure to Physical Abuse and Adult Offending: Examining Mediating Factors and Gendered Relationships. Justice Quarterly 25: 313–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terren, Ludovic, and Rosa Borge. 2021. Echo Chambers on Social Media: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Review of Communication Research 9: 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry, Terence P. 1987. Toward an Interactional Theory of Delinquency. Criminology 25: 863–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberry, Terence P., and Marvin D. Krohn. 2001. The development of delinquency: An interactional perspective. In Handbook of Youth and Justice. Edited by Susan O. White. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Peiru, and Irene Shidong An. 2024. Review of Studies Applying Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory in International and Intercultural Education Research. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1233925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Justice. 1996. Combating Violence and Delinquency: The National Juvenile Justice Action Plan (NCJ 157106). Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/library/publications/combating-violence-and-delinquency-national-juvenile-justice-action-plan-0 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- U.S. Department of Justice. 2024. Youth Violence. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/feature/youth-violence/overview (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- van der Merwe, Amelia, Andrew Dawes, and Catherine L. Ward. 2013. The development of youth violence: An ecological understanding. In Youth Violence: Sources and Solutions in South Africa. Edited by Andrew Dawes, Amelia Van Der Merwe and Catherine L. Ward. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, pp. 53–92. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dorn, Richard, Jan Volavka, and Norman Johnson. 2012. Mental Disorder and Violence: Is There a Relationship Beyond Substance Use? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 47: 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, Michael G., Christopher P. Salas-Wright, Matt DeLisi, and Brandy R. Maynard. 2014. Violence and Externalizing Behavior Among Youth in the United States. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 12: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, Dexter R., Lois Takahashi, David B. Miller, and Jun Sung Hong. 2023. Bullying Victimization and Perpetration: Some Answers and More Questions. Journal of Pediatrics 99: 309–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Behr, Ines, Anais Reding, Charlie Edwards, and Luke Gribbon. 2013. Radicalisation in the Digital Era: The Use of the Internet in 15 Cases of Terrorism and Extremism. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR453.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Walker, Meaghan, Stephanie Nixon, Jess Haines, and Amy C. McPherson. 2019. Examining Risk Factors for Overweight and Obesity in Children with Disabilities: A Commentary on Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Framework. Developmental Neurorehabilitation 22: 359–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, William H. 2012. Family systems. In Encyclopedia of Human Behavior, 2nd ed. Edited by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 184–93. [Google Scholar]

- Whipple, Christopher R., W. LaVome Robinson, and Leonard A. Jason. 2021. Expanding Collective Efficacy Theory to Reduce Violence Among African American Adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: NP8615–NP8642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittaker, Joe, Seán Looney, Alastair Reed, and Fabio Votta. 2021. Recommender Systems and the Amplification of Extremist Content. Internet Policy Review 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Kirk R., and Nancy G. Guerra. 2011. Perceptions of Collective Efficacy and Bullying Perpetration in Schools. Social Problems 58: 126–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, Taisto. 2020. “If I Cannot Have It, I Will Do Everything I Can to Destroy It.” The Canonization of Elliot Rodger: ‘Incel’ Masculinities, Secular Sainthood, and Justifications of Ideological Violence. Social Identities 26: 675–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2024. Youth Violence. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/youth-violence (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Yao, Xuening, Hongwei Zhang, and Ruohui Zhao. 2022. Does Trauma Exacerbate Criminal Behavior? An Exploratory Study of Child Maltreatment and Chronic Offending in a Sample of Chinese Juvenile Offenders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, Michelle L., Kimberly J. Mitchell, and Jay Koby Oppenheim. 2022. Violent Media in Childhood and Seriously Violent Behavior in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health 71: 285–92. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Susan, and Kelly Cocallis. 2022. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and offending. In Clinical Forensic Psychology: Introductory Perspectives on Offending. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 303–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Shaoling, Rongqin Yu, and Seena Fazel. 2020. Drug Use Disorders and Violence: Associations with Individual Drug Categories. Epidemiologic Reviews 42: 103–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Gregory M., and Steven F. Messner. 2010. Neighborhood Context and the Gender Gap in Adolescent Violent Crime. American Sociological Review 75: 958–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paat, Y.-F.; Yeager, K.H.; Cruz, E.M.; Cole, R.; Torres-Hostos, L.R. Understanding Youth Violence Through a Socio-Ecological Lens. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070424

Paat Y-F, Yeager KH, Cruz EM, Cole R, Torres-Hostos LR. Understanding Youth Violence Through a Socio-Ecological Lens. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(7):424. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070424

Chicago/Turabian StylePaat, Yok-Fong, Kristopher Hawk Yeager, Erik M. Cruz, Rebecca Cole, and Luis R. Torres-Hostos. 2025. "Understanding Youth Violence Through a Socio-Ecological Lens" Social Sciences 14, no. 7: 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070424

APA StylePaat, Y.-F., Yeager, K. H., Cruz, E. M., Cole, R., & Torres-Hostos, L. R. (2025). Understanding Youth Violence Through a Socio-Ecological Lens. Social Sciences, 14(7), 424. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070424