Abstract

The development and validation of the Ideological Radicalization Sensitivity Inventory (ISIR-14) in a Mexican sample is presented. A total of 537 participants were assessed. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses supported a five-factor structure that explained 53.7% of the variance, with excellent model fit indices (CFI = 0.985, TLI = 0.978, RMSEA = 0.033). Evidence of concurrent validity was suggested through significant correlations with the Emotional Response to Unfairness Scale (ERU) and the Exposure to Violent Extremism Scale (EXPO-12). Reliability analyses indicated good internal consistency (ω = 0.819) for the instrument. Additionally, temporal stability, analyzed in a second study with 171 participants, showed moderate stability (r = 0.601). The study aimed to test the hypothesis that sensitivity to ideological radicalization can be reliably measured through a multidimensional instrument aligned with theoretically derived psychological risk factors, namely, inclination to seek redress, perceived social disconnection, ideological superiority, exposure to extreme ideologies, and collective/group identity. The results suggest that the ISIR-14 is a reliable and valid tool for assessing sensitivity to ideological radicalization. The scale provides a foundation for future research and interventions aimed at identifying and addressing factors associated with radicalization processes.

1. Introduction

Political or religious radicalization can trigger significant social risks (Horgan 2008; Moghaddam 2005). Some of these can be lethal (Borum 2011; McCauley and Moskalenko 2011). For this reason, it is relevant to evaluate the psychological factors linked to radicalization. It is identified as the process by which a person or group adopts increasingly extreme ideals and aspirations that challenge the status quo or contemporary ideas of freedom of choice (Scarcella et al. 2016). The concept of radicalization is used to convey the idea of a process through which a person adopts an increasingly extremist set of beliefs and aspirations (Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos 2016).

Various variables have been associated with the radicalization process. There is evidence indicating that loss of significance—for example, due to economic hardship or social rejection—may be associated with extremism (Da Silva et al. 2024; Webber et al. 2018). That is, it is possible that the loss of significance helps explain ideological commitment and radicalism, as individuals seeking significance often desire to feel part of a greater cause (Kruglanski et al. 2017). In this regard, Significance Loss Theory posits that, given that group membership is a central component of social identity, personal humiliation, loss of status, or social marginalization can motivate individuals to seek meaning through extremist groups (Kruglanski and Orehek 2011). This is consistent with Significance Quest Theory (SQT), which asserts that the need for personal significance—the desire to matter, to “be someone,” and to have purpose in one’s life—is the dominant need underlying violent extremism (Kruglanski et al. 2018). It is important to clarify that SQT assumes the need for significance is universal, but the means to fulfill this need depend on the sociocultural context in which an individual’s values are embedded (Kruglanski et al. 2022a). The loss of personal significance constitutes a core factor that may trigger intense behaviors aimed at restoring the perceived value of the self. Accordingly, Significance Loss Theory (SLT) argues that the experience of significance loss can motivate adherence to extreme causes, including the acceptance of violence as a means to regain status, belonging, or purpose, whereas Significance Quest Theory (SQT) proposes that the quest for significance may be activated not only by loss, but also by the expectation or potential gain of significance, including prosocial goals (Dono et al. 2024). For instance, individuals may attempt to satisfy their need to feel meaningful and respected through peaceful but effortful behaviors, which is especially relevant for the process of deradicalization (Molinario et al. 2025). These theoretical perspectives align with models that distinguish between the psychological roots of radicalization and the behavioral pathways individuals may follow. For example, in the two pyramids model (McCauley and Moskalenko 2017), one pyramid explains action or participation, indicating that a person progresses through five levels—affiliation, socialization, commitment, facilitation, and ultimately action. Another pyramid is used to describe the process of gradually delegitimizing victims and the outside world. Similarly, another model widely cited in the literature, the ABC model, distinguishes between opinion and action in the radicalization process, establishing that extreme opinion does not necessarily lead to extreme action (McCauley 2022).

It has also been proposed that individual needs, narratives, and social support networks contribute to radicalization (Kruglanski et al. 2014). This proposal is known as the 3N model and has empirical support (Lobato et al. 2023). For example, in different cultural contexts, social alienation has been reported to increase support for political violence, which predicts the desire to join radical groups, with moral justification identified as the underlying mechanism (Bélanger et al. 2019).

There is abundant literature supporting both the two pyramids model (McCauley and Moskalenko 2017; Pavlović et al. 2024) and the 3N model (Kruglanski et al. 2022b; Lobato et al. 2021, 2023). These models can be useful for explaining the radicalization process. Even so, some psychological characteristics that might facilitate such a process remain to be identified. Although there are doubts about the existence of a common profile, it is possible that certain characteristics do identify radicalized individuals (McCauley and Moskalenko 2014).

In addition to identifying individual traits that may facilitate radicalization, it is important to consider both protective variables and digital contexts that can either mitigate or amplify extremist processes.

1.1. Protective Factors and Online Factors

Several studies on radicalization consistently report that individual, relational, and social factors work together to reduce extremist attitudes and behaviors. In a systematic review, it was found that certain psychosocial elements—similar to those used in violence prevention—decrease vulnerability to extremism: stable employment, positive parental support, and relationships with non-delinquent peers (Lösel et al. 2018). Conversely, cognitive and personality variables such as low self-control and impulsivity are significantly associated with a greater propensity toward radicalization, whereas their opposites—high self-control and low impulsivity—may function as protective factors (Wolfowicz et al. 2020). This is supported by reports indicating that individuals with a high trait of forgiveness, strong self-control abilities, and both critical and open thinking styles are less vulnerable to the adverse effects of group-based injustice on violent extremism (Rottweiler and Gill 2022). Socio-emotional variables also appear to play a relevant role in the radicalization processes. For instance, an intervention program aimed at enhancing personal self-esteem and empathy toward others found that these variables significantly reduced support for ideological violence and violent intentions (Feddes et al. 2015). However, some reports suggest that the effectiveness of protective factors may vary depending on the population and context (Eldor et al. 2022; Wolfowicz et al. 2021). Thus, the literature suggests that both individual and social factors play a crucial role. Accordingly, interventions that incorporate such protective factors may help prevent radicalization. In this regard, interventions promoting positive social bonds, critical thinking skills, and community support have been reported to significantly reduce extremist attitudes and hate-related behaviors (Jugl et al. 2020).

Digital ecosystems and social media play a significant role in radicalization by acting as facilitators and amplifiers of extremist ideologies. Reports indicate that they influence radicalization by fostering echo chambers that reinforce extremist narratives and shape key psychological processes (Mølmen and Ravndal 2023). Specifically, it has been reported that active and deliberate exposure to radical online content is directly associated with extremist attitudes as well as with an increased willingness to engage in violence (Schumann et al. 2024). Furthermore, in the process of manipulation and psychological abuse for radicalization, new technologies enable stricter and more remote control (Trujillo et al. 2018). Online communities, including those based on hate, can have tangible real-world consequences, as many perpetrators of offline extremist acts previously participated in virtual spaces, and the spread of hate speech on social networks has been linked to subsequent hate crimes (Oksanen et al. 2024). Additionally, specific platform features, such as Reddit’s upvoting system, can legitimize extremist messages and foster the formation of a collective identity based on hatred, solidifying users’ convictions (Gaudette et al. 2021). This is reinforced by other studies indicating that participation in ideologically homogeneous online communities is associated with fixation, toxicity, and anger (Habib et al. 2022). In this regard, it has been postulated that the internet functions as a multiplier that modulates other radicalization factors, with different platforms fulfilling distinct roles in the dissemination of propaganda and the consolidation of closed extremist communities (Conway 2017). Additionally, exposure to violence—such as that presented on internet platforms—may lead to desensitization to violence, resulting in decreased negative emotional reactions and less critical judgments toward violent acts (Galán Jiménez et al. 2022).

1.2. Sensitivity to Ideological Radicalization

Beyond protective and contextual influences, specific psychological and social characteristics may increase the likelihood of radicalization and are therefore central to the present study.

1.2.1. Ideological Superiority

The belief in ideological superiority can be significantly related to radicalization, as evidenced by various studies. In this regard, it has been emphasized that violent radicalization often emerges from perceptions of ideological and moral superiority that lead to the justification of extreme acts (Koehler 2023; Ozer and Bertelsen 2018). Furthermore, a study with Dutch youth reported how the perception of a superior ideology can foster a sense of belonging and moral justification for radical acts (Doosje et al. 2012).

It has also been suggested that the perception of collective superiority can initiate radicalization pathways by strengthening the belief in the justification of violence as a legitimate means to defend the ideology perceived as superior (Trip et al. 2019). Thus, one’s own group is idealized as pure, while the enemy is portrayed as malevolent (Beck 2002). This is coherent with integrated threat theory (Stephan and Stephan 2000), which would indicate that the norms, values, and beliefs of one’s own group are more correct than those of the outgroup and that therefore one’s own group is superior.

Moreover, the academic literature indicates that ideological superiority is often accompanied by affective polarization processes, in which hostility toward the outgroup intensifies and is justified in terms of defending principles perceived as universal or transcendent (Iyengar et al. 2012). This suggests that such psychological and social processes may contribute to radicalization by legitimizing exclusion, intolerance, and, in extreme cases, violence as necessary means to preserve the group’s integrity and its ideology.

1.2.2. Inclination to Seek Redress Against Injustice

Extreme beliefs and vigilante justice are not only related to the perception of injustice but also to neurocognitive mechanisms that reinforce these behaviors (Decety 2024). However, perceptions of personal and social injustice may lead to extreme behaviors (Beugré 2005; Kennedy et al. 2003; Khattak et al. 2019). In this regard, it has been reported that personal sensitivity to injustice, whether from direct or indirect experiences, may predispose individuals to develop radical attitudes and justify violence as a legitimate form of action (Jahnke et al. 2020). Along these lines, it has been identified that radicalization among young Muslims in the Netherlands is fueled by the perception of injustice and personal uncertainty, fostering a radical belief system that justifies violence as a means of correcting these perceived injustices (Doosje et al. 2013). This dynamic has been observed in studies showing that radicalization intensifies when people feel that their social group is unjustly treated, leading to a violent response that seeks to restore order and justice (Van Den Bos 2020). This is further supported by reports indicating that socialization processes in marginalized or exclusionary environments can strengthen ties with extremist groups, which offer a sense of community and purpose (McCauley and Moskalenko 2017). Likewise, the influence of charismatic leaders and exposure to polarizing narratives through social media amplify the internalization of radical ideas, facilitating the adoption of extreme behaviors, such as those observed in “lone wolf” attacks (Hamm and Spaaij 2017).

1.2.3. Perceived Social Disconnection

It has been argued that certain individual characteristics such as social exclusion can facilitate radicalization (Roberts-Ingleson and McCann 2023). For instance, both theoretical and empirical work has directly linked beliefs and behavioral orientations related to radicalization with social exclusion (Wesselmann et al. 2023). In fact, reducing social exclusion through social integration is one method for preventing radicalization (Del Pino-Brunet et al. 2021), which suggests that exclusion is a facilitating variable. Even psychological constructs that clearly involve social isolation, such as anomie, prove to be predictors of violent extremism and mediate radicalization (Troian et al. 2019).

Beyond social exclusion, emotional disconnection and the absence of meaningful bonds in one’s immediate environment also contribute significantly to ideological radicalization. Feelings of emotional emptiness and lack of affective support may lead individuals to seek meaning and belonging in radical groups that offer a clear identity and a shared purpose (Bjørgo 2006). This personal disconnection not only increases vulnerability to extremist messages but may also intensify feelings of alienation and resentment, facilitating the adoption of rigid and violent ideologies as a means of compensating for the lack of deep social connection (Horgan 2014).

1.2.4. Exposure to Extreme Ideologies

Extreme ideologies are often characterized by black-and-white, simplistic perceptions of the social world, leading to heightened confidence in one’s judgments and decreased tolerance of other groups and opinions (Van Prooijen and Krouwel 2019). Radical social contexts reinforce the search for meaning—particularly collective meaning—and support for political violence (Jasko et al. 2020). This is consistent with studies reporting that the presence of radicalized individuals in a person’s social networks increases the likelihood of using violence (Jasko et al. 2017). Even censorship of information on social media can increase certainty in radicalized beliefs by reducing exposure to dissenting information (Lane et al. 2021).

As previously noted, certain online ecosystems play a role in radicalization by functioning as echo chambers (Mølmen and Ravndal 2023). This not only reinforces simplistic and polarized worldviews, but also promotes the dehumanization of the “other” and justifies violence as a legitimate means of achieving ideological goals (Sunstein 2018). Furthermore, constant interaction with ideologically extreme environments can intensify radicalization and facilitate the adoption of violence as a legitimate strategy (Schuurman et al. 2019). In fact, evidence indicates that 78% of lone actors were exposed to external sources of justification or encouragement for the use of violence (Schuurman et al. 2019).

1.2.5. Collective/Group Identity

An acute sense of moral agency associated with the fusion of personal identity and the group compels not only aggression against outgroup members but also self-sacrifice for the broader ingroup (Swann et al. 2010). This may help explain reports indicating that radical contexts strengthen the link between the search for collective significance and support for political violence (Jasko et al. 2020). In this sense, the radicalization process often begins with the activation of a personal search for significance within the group’s collective ideology, which can lead to an increased sense of power and importance and heighten one’s predisposition to embrace and justify violence in the group’s name (Kruglanski et al. 2014). In turn, experiences of personal loss of meaning, such as social rejection or academic failure, may motivate people to resort to extreme means to restore their sense of significance (Jasko et al. 2017).

When individuals strongly identify with a group that promotes a rigid ideological worldview, this shared identity can reinforce extreme norms and values, potentially leading to violent behaviors aimed at defending or advancing the group (Besta et al. 2015; Henríquez Henríquez et al. 2020). Moreover, the construction of an exclusionary collective identity tends to polarize intergroup relations, intensifying perceived threats and justifying hostility toward “others,” thereby facilitating the adoption of radical positions and extremist actions (Rinella et al. 2020).

1.3. Psychometric Assessment of Radicalization Risk Factors

There are various psychometric approaches for assessing variables related to radicalization (Scarcella et al. 2016). However, despite their number, they tend to be weak or require better psychometric properties. For example, problems have been reported in reliability, including lack of evidence of temporal stability, lack of criterion validity, and inadequate cultural adaptations (Scarcella et al. 2016), or they are designed specifically for one culture, limiting their generalizability (Ehsan et al. 2021). Moreover, scales with adequate psychometric properties are unidimensional or bidimensional (Bhui et al. 2015; Ozer and Bertelsen 2018), or they measure an already established form of radicalization (González-Álvarez et al. 2024), which excludes variables that might contribute to explaining the construct. Identifying such variables is valuable because it would help distinguish individuals who may be more sensitive or vulnerable during a process of radicalization. Thus, the present work focuses on risk factors that likely make people more sensitive to ideological radicalization. In this regard, the evidence indicates that radicalization may be linked to a sense of ideological superiority (Doosje et al. 2012; Koehler 2023; Trip et al. 2019) as well as a favorable attitude toward carrying out reclaiming actions when perceiving unjust acts (Jahnke et al. 2020; Moghaddam 2005), perceived social disconnection (Gidron and Hall 2020; Pfundmair and Mahr 2023; Wesselmann et al. 2023), exposure to extreme ideologies (Jasko et al. 2020; Youngblood 2020), and collective/group identity (Brewer and Gardner 1996; Kruglanski et al. 2014; Rousseau et al. 2021). On this basis, the objective of the present work is to design and evaluate the psychometric properties of an inventory for assessing radicalization risk factors.

2. Study 1: Factorial Structure and Main Psychometric Properties

Study 1 examines the psychometric properties of the ISIR-14 by assessing the content validity ratio, exploring its factorial structure through exploratory factor analysis, evaluating its structural validity via confirmatory factor analysis, and determining its reliability. It is therefore postulated that sensitivity to ideological radicalization can be reliably measured through a multidimensional instrument aligned with psychological risk factors: inclination to seek redress, perceived social disconnection, ideological superiority, exposure to extreme ideologies, and collective/group identity. Consequently, it is hypothesized that there is a positive relationship between these factors. Additionally, for concurrent validity, it is hypothesized that there will be a positive relationship between the ISIR-14 and both the ERU and EXPO-12.

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants

Participants were selected through convenience sampling via an invitation posted on the authors’ social media platforms. The sample consisted of 537 participants, including 359 women (W) with a mean age of 42.4 (SD = 14.9) and 180 men (M) with a mean age of 40.7 (SD = 16.1). Educational levels were distributed as follows: 55.1% held a bachelor’s degree, 25.1% held a postgraduate degree, 18.1% completed high school, 1.3% held a technical degree, and 0.4% had completed K–12 education. The sample was randomly divided into two subsamples. One subsample (Sa) was used for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (N = 269), consisting of 171 women and 98 men. The second subsample (Sb) was used for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (N = 268), comprising 180 women and 79 men. Participants were treated following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2013) and provided informed consent.

2.1.2. Instruments

Inventory on Sensitivity to Ideological Radicalization (ISIR-14): This instrument consists of 14 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = completely disagree and 5 = completely agree.

Emotional Response to Unfairness Scale (ERU) (Bizer 2020): This scale measures feelings of unfairness using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = extremely uncharacteristic to 5 = extremely characteristic. Reported reliability is α = 0.76.

Exposure to Violent Extremism Scale (EXPO-12) (Clemmow et al. 2022): This instrument assesses exposure to violent extremism on a Likert scale ranging from 0 = never to 7 = always. Reported reliability is Active seeking (ω = 0.740), Active action (ω = 0.792), Passive online (ω = 0.794), and Passive offline (ω = 0.838), EXPO-12 overall score (ω = 0.859).

2.1.3. Procedure

Item Development

Items were developed using a logical or deductive partitioning method. This process involved a literature review and the assessment of indicators related to the construct being measured (Boateng et al. 2018). Based on this, items were created around five dimensions: ideological superiority (Crone 2016; Koehler 2023; Ozer and Bertelsen 2018; Trip et al. 2019), inclination to seek redress against injustice (Decety 2024; Jansma et al. 2022; Shafieioun and Haq 2023; Shah et al. 2019), perceived social disconnection (Emmelkamp et al. 2020; Roberts-Ingleson and McCann 2023; Wesselmann et al. 2023), exposure to extreme ideologies (Jasko et al. 2020; Mølmen and Ravndal 2023; Youngblood 2020), and collective/group identity (Emmelkamp et al. 2020; Jasko et al. 2017; Kruglanski et al. 2014). The initial item generation process was further supported by artificial intelligence using a prompt that instructed the creation of Likert-scale items, mandatory inclusion of references from the aforementioned authors, and mention of the specific dimensions. The researchers reviewed the proposed items, selecting the best options and subjecting them to content validity analysis.

Content Validity

To assess content validity, six experts served as judges. They were university professors whose lines of research or courses are related to the construct evaluated in this study. The judges evaluated the relevance of each item using a three-level criterion (Lawshe 1975): (a) the item is essential, (b) the item is useful but not essential, and (c) the item is not necessary. The content validity coefficient was determined based on the Tristán-López algorithm (Tristán-López 2008). The result of this analysis confirmed the viability of the constructed items.

Instrument Administration

The instruments were administered through an electronic form, which included the three instruments as well as the informed consent and a sociodemographic data survey. All items in the instrument were programmed to require mandatory responses, preventing participants from leaving any unanswered. This ensured there were no missing data.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS v.29 (SPSS Inc. 2021), AMOS v.29 (Arbuckle 2022) and Jamovi v.2.6.19 (The Jamovi Project 2024). For the exploratory factor analysis, principal axis factoring with PROMAX rotation was used, given that the factors were correlated. During factor extraction, the main criteria were an eigenvalue from parallel analysis greater than the randomly simulated values (Horn 1965) and factor loadings > 0.40. The confirmatory factor analysis was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Regarding the CFI and TLI, there is a general consensus for using a cutoff of 0.95 as an indicator of optimal fit and for using values below 0.06 for the RMSEA (Barrett 2007; Hu and Bentler 1999). Internal consistency was assessed using McDonald’s omega.

2.2. Results

2.2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

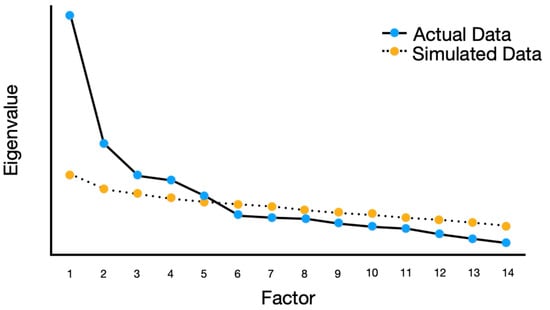

To determine the factor structure of the instrument, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. Prior to the EFA, a homogeneity analysis was performed. The results of this analysis yielded a mean of 0.436. Once homogeneity was confirmed, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test (KMO = 0.789) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2188 = 1618.288, p < 0.001), were carried out, indicating the suitability of proceeding with the EFA. The eigenvalue-based analysis, parallel analysis, and the scree plot (Figure 1) all supported the retaining of five factors (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Parallel analysis and scree plot used for factor retention.

Table 1.

Factor loadings of the ISIR-14.

The first factor (F1) had an eigenvalue of 4.824, explaining 27.508% of the total variance; the second factor (F2) obtained an eigenvalue of 2.003 and explains 10.180% of the total variance. In turn, the third factor (F3), with an eigenvalue of 1.607, explains 7.701% of the total variance, while the fourth factor (F4) had an eigenvalue of 1.255, accounting for 5.093% of the total variance. Finally, the fifth factor (F5) obtained an eigenvalue of 1.072, explaining 3.254% of the total variance. Altogether, the five factors explained 53.735% of the total variance. The minimum extracted communality was 0.257, and the maximum was 0.899.

The correlations between factors revealed a relationship between F1 and F5 (r = 0.481), F1 and F4 (r = 0.486), F1 and F3 (r = 0.321), and F1 and F2 (r = 0.161). Additionally, correlations were found between F2 and F5 (r = 0.134), F2 and F4 (r = 0.328), and F2 and F3 (r = 0.348). Further correlations showed relationships between F3 and F5 (r = 0.413) and between F3 and F4 (r = 0.397). Finally, a correlation of r = 0.542 was observed between F4 and F5.

Floor and ceiling effects were examined (Table 2) by calculating the percentage of participants who obtained the minimum and maximum possible scores on each ISIR-14 subscale as well as on the instrument’s global scale. For most scales, the proportion of extreme scores remained below the commonly accepted threshold of 15% (Terwee et al. 2007), indicating adequate sensitivity. However, subscales F3 (perceived social disconnection) and F4 (exposure to extreme ideologies) showed floor effects of 45.4% and 43.8%, respectively, suggesting that a substantial portion of respondents endorsed the lowest possible score on these dimensions. No significant ceiling effects were observed either in the global scale or in any subscale.

Table 2.

Floor and ceiling effects.

2.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

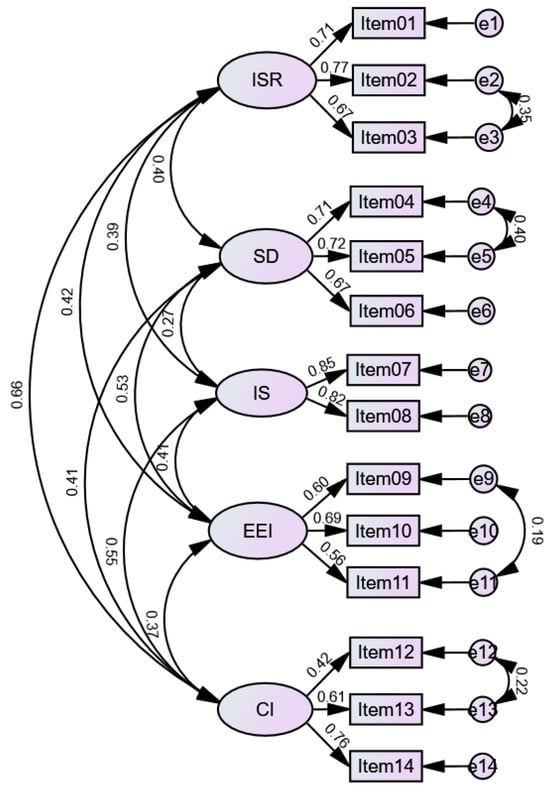

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the Sb subsample using the maximum likelihood estimation method (Figure 2). Prior to this, normality and linearity were analyzed. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test yielded a p-value greater than 0.05, providing no evidence to reject the assumption of normality. In addition, Q–Q plots showed a close alignment with the diagonal line, and residual scatterplots did not reveal any systematic patterns, suggesting linearity. The model fit indices indicated a good fit, χ2(63) = 80.9, p = 0.064 (χ2/df = 1.284), with optimal values for the Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.985), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.978), and Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.033; 90% CI [0.00, 0.052]). The goodness-of-fit index, parsimony indices, and standardized root-mean-square residual also showed acceptable levels (GFI = 0.958, AGFI = 0.930, PNFI = 0.647, PCFI = 0.682, SRMR = 0.034). Other indicators, which are reported less frequently in the literature, likewise demonstrated good fit and acceptable parsimony (NFI = 0.935, RFI = 0.906, PGFI = 0.575). A post hoc power analysis was conducted for the confirmatory factor analysis using RMSEA-based estimation (MacCallum et al. 1999). With 63 degrees of freedom, α = 0.05, a close-fit hypothesis RMSEA of 0.05, and a not-close-fit hypothesis RMSEA of 0.08, the estimated power for the CFA model with N = 268 was 0.94. This result indicates that the sample size was sufficient to detect model misfit with high sensitivity.

Figure 2.

Path diagram for the confirmatory factor analysis of ISIR-14.

2.2.3. Concurrent Validity Analysis

The relationship between the factors of the ISIR-14 and the ERU and EXPO-12 was analyzed. The results of the analysis are presented in Table 3. Effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals for all correlations are reported in the same table, based on 1000 bootstrap replicates, as recommended.

Table 3.

Relationships between instruments for concurrent validity and the ISIR-14 factors.

2.2.4. Discriminant Validity Analysis

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, comparing the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each factor with the correlations between factors. The results showed that the square root of the AVE for each factor (F1 = 0.715, F2 = 0.698, F3 = 0.834, F4 = 0.618, F5 = 0.608) was greater than the inter-factor correlations in all comparisons (Table 4). As observed, in each case, the square root of the AVE (diagonal) exceeded the corresponding inter-factor correlations, thus meeting the discriminant validity requirements according to the Fornell–Larcker criterion.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix by factor and square root of AVE for discriminant validity.

2.2.5. Internal Consistency Analysis

Internal consistency was evaluated using McDonald’s omega. The total ISIR-14 yielded ω = 0.819 and an Average Inter-Item Correlation (AIC) of 0.246. The sample for this analysis included the full Sa and Sb samples (N = 537). Factor F1 obtained ω = 0.839 and an AIC of 0.724; Factor F2, ω = 0.0820 and AIC = 0.597; Factor F3, ω = 0.824 and AIC = 0.552; Factor F4, ω = 0.705 and AIC = 0.445; and finally, Factor F5, ω = 0.623 and AIC = 0.355.

2.2.6. Descriptive Statistics by Gender

The descriptive data by gender are shown in Table 5. Because larger differences were observed in some factors, a t-test was conducted to analyze these differences. Factors 2 and 5 showed differences, with higher mean scores in women. For Factors 1, 3, and 4, which displayed higher mean scores in men than in women, no significant differences were found.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for each factor and for the total ISIR-14.

2.3. Discussion

The results of the Ideological Radicalization Sensitivity Inventory (ISIR-14) support the proposed factorial structure, consisting of five theoretical dimensions that capture key psychological factors relevant to the radicalization process. Both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses indicated an optimal model fit along with acceptable internal consistency indices. These findings align with previous research suggesting that variables such as inclination to seek redress (F1), social disconnection (F2), ideological superiority (F3), exposure to extreme ideologies (F4), and collective identity (F5) may play a central role in predisposing individuals to radicalization.

The inclination to seek redress (ISR) factor aligns with research linking the perception of inequity to the justification of violence as a restorative response (Jahnke et al. 2020; Van Den Bos 2020). Its significant relationship with the ERU reinforces the notion that perceived injustice can be associated with negative emotions that may motivate the pursuit of radical solutions. In this regard, it has been noted that the perception of being treated unfairly can increase the willingness to engage in activities aimed at correcting such inequalities (Penagos-Corzo et al. 2019), even when these actions involve social or personal risks (Chory-Assad and Paulsel 2004; Doosje et al. 2013).

Regarding the social disconnection factor, the results showed significant but low associations with concurrent measures. This suggests that this factor likely operates more as a facilitator than a direct predictor of radicalization, aligning with models such as the 3N model (Kruglanski et al. 2014). Perceived disconnection can create emotional vulnerabilities that lead individuals to adopt extreme beliefs as a means of finding cohesion and identity. In this sense, our findings align with previous research emphasizing the role of social exclusion in increasing support for radical ideologies. These results reinforce theoretical models like the 3N, which highlight the need for belonging and meaning as key drivers of radicalization (Bélanger et al. 2019).

The ideological superiority factor is consistent with previous studies highlighting how perceptions of moral superiority can justify extreme actions (Doosje et al. 2012; Koehler 2023). Its significant associations with ERU and EXPO-12 align with the previously cited studies that underscore the role of moral and intellectual superiority beliefs in predisposing individuals to radical stances. This dimension appears to function as a cognitive mechanism that legitimizes the disqualification of other groups, a process well-documented in Integrated Threat Theory (Stephan and Stephan 2000). Prior research has indicated that such beliefs can foster group divisions and facilitate adherence to extreme ideologies by providing a framework to validate actions directed against those perceived as different (Toner et al. 2013).

Meanwhile, Factors 4 and 5—exposure to extreme ideologies and collective identity—align with the existing literature indicating that exposure to radicalized social networks and strong group identification can amplify extremist attitudes (Jasko et al. 2017; Swann et al. 2010). Concurrent validity evidence with ERU and EXPO-12 revealed weak to moderate but significant associations. This may reflect the complexity of these constructs, which, as suggested by previously cited studies, tend to interact with other factors—such as past experiences of exclusion or the search for personal meaning—rather than operate independently. Our findings are consistent with research indicating that these factors act as catalysts in combination with other psychological variables (Jasko et al. 2020). Exposure to extreme ideologies may reinforce pre-existing beliefs, while collective identity can provide a framework to justify actions taken on behalf of the group.

3. Study 2. Temporal Stability

To analyze the temporal stability of the instrument, it was administered at two different time points.

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 171 participants, including 99 women and 72 men who agreed to participate. Participants were selected based on their acceptance of an invitation made by the researchers in classroom settings. The mean age for men was 20.4 (SD = 1.927), while for women it was 19.8 (SD = 2.121). All participants were university students. Informed consent was included at the beginning of the survey and was mandatory to proceed if accepted. Participants were treated in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2013).

3.1.2. Instruments

The Inventory on Sensitivity to Ideological Radicalization (ISIR-14) was administered in an electronic format. As reported in this study, the instrument consists of 14 items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree. The overall reliability of the instrument is ω = 0.819.

3.1.3. Procedure

Participants completed the ISIR-14 on two occasions separated by a 40-day interval. On each occasion, one of the researchers requested time during the classes in which the students were enrolled. The purpose of the study was explained, students were invited to participate, and all aspects related to informed consent were clarified. To ensure anonymity, each student was assigned a unique four-digit code, used solely to link data from the first and second assessments.

3.2. Results and Discussion

A correlation analysis revealed a relationship of r = 0.601, p < 0.001, for the total score of the inventory. Regarding the individual factors, all showed moderate and significant correlations: F1 (r = 0.546, p < 0.001), F2 (r = 0.601, p < 0.001), F3 (r = 0.574, p < 0.001), F4 (r = 0.435, p < 0.001), and F5 (r = 0.534, p < 0.001). These results indicate that responses to the ISIR-14 over the two different time points were moderately consistent. This level of consistency is expected, given that the constructs assessed involve sociopolitical attitudes and beliefs, which are susceptible to contextual changes. Radicalization is not a static trait, but rather, a dynamic process that can fluctuate over time in response to social events, political shifts, and personal changes (Borum 2011; Windsor 2020).

Notably, F4—exposure to extreme ideologies—showed moderate stability but the lowest correlation among the factors, suggesting a potential influence of temporary circumstances such as fluctuations in social media consumption or varying exposure to environments where radicalizing ideas or extreme ideologies are disseminated. Exposure is not always under individual control but can depend on the availability of information, social contacts, and other external factors.

It was also observed that scores from the second measurement were generally higher than those from the first (see Table 6). As a result, comparisons between the two assessments revealed significant differences in the test–retest comparison of F3 (t = 2.461, df = 170, p = 0.015) and in the total score of the instrument (t = 2.148, df = 170, p = 0.033). Although the values for F3—ideological superiority—increased, it is important to note that the temporal stability coefficient remained moderate and significant. This increase could indicate the influence of polarizing events on the radicalization process. Beliefs of ideological superiority may fluctuate if individuals encounter group reinforcement or events that justify more extreme views (Sibley et al. 2007). Data collection for this study coincided with a period of political unrest, which may have contributed to the elevated scores.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of the temporal stability of ISIR-14 in two measurements.

The overall increase in the total score can likely be attributed to the rise in F3 scores. Since the total score reflects the sum of all factors, fluctuations in F3 could have driven the overall increase. Lastly, while the 40-day interval between assessments is reasonable for evaluating temporal stability, there may have been memory effects or increased self-awareness that influenced responses in the second measurement. Future studies are encouraged to vary the time intervals to assess these potential effects and to include contextual variables that may impact the results.

4. General Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the importance of assessing psychological factors associated with ideological radicalization. The analyses indicated that the dimensions evaluated—inclination to seek redress, social disconnection, ideological superiority, exposure to extreme ideologies, and collective identity—explained more than fifty percent of the total variance, suggesting that these factors capture key constructs in the radicalization process.

An individual can undergo radicalization by adopting extreme ideologies (Scarcella et al. 2016), without necessarily developing favorable attitudes toward terrorism or religious fanaticism. However, this process can escalate and result in lethal behaviors (McCauley and Moskalenko 2017). Despite the potential danger posed by the adoption of extreme ideologies, the psychometric evaluation of individual risk factors—such as vulnerability or susceptibility to radicalization—has been insufficiently explored. This study contributes an instrument that focuses on these individual factors. Moreover, the nature of its items makes it suitable for societies not deeply immersed in highly radicalized religious or violent contexts, such as the Mexican culture in which the inventory was validated.

Our findings further support the idea that radicalization should not be approached as a unidimensional phenomenon tied solely to religious or political aspects. Instead, the process appears to be fueled by a combination of psychological and social factors that predispose or facilitate the adoption of extreme beliefs and behaviors. In particular, the results emphasize the interaction between cognitive elements such as ideological superiority, affective components such as the inclination to seek redress arising from perceived injustice, and contextual factors such as exposure to extreme ideologies and group support or collective identity. These findings provide additional evidence for theoretical models like the dual-pyramid model of radicalization (McCauley and Moskalenko 2017) and the 3N model (Kruglanski et al. 2014), both of which highlight the reciprocal influence between personal needs, group narratives, and social support networks.

A noteworthy aspect is how perceived social disconnection likely functions as a catalyst for extremist positions. When individuals experience exclusion, lack of recognition, or identity voids, their vulnerability to radical stances that offer belonging and a transcendent purpose tends to increase (Bélanger et al. 2019; Pfundmair and Mahr 2023). This catalytic role aligns with the literature linking social exclusion to greater adherence to extreme beliefs (Roberts-Ingleson and McCann 2023) and supports the notion that the search for meaning intensifies when individuals feel marginalized (Jasko et al. 2017).

Additionally, the observed increase in the ideological superiority factor between the two measurements highlights the fluid and malleable nature of these attitudes. This suggests that variations in radicalization occur along a continuum influenced by situational variables (Horgan 2008).

From a cross-cultural perspective, the validation of this scale in a Mexican population adds significant value, as most existing instruments have been developed in Western contexts (e.g., Europe or the United States) with a predominant focus on religious extremism or global terrorism (Ehsan et al. 2021). The ISIR-14 appears to be sensitive to forms of radicalization not necessarily tied to violent extremism or terrorist organizations, making it a versatile tool for measuring incipient or “soft” radicalization processes. This is particularly relevant in national contexts where, despite the absence of a history of terrorist violence, political or social polarization dynamics can still lead to disruptive or violent acts (Gidron and Hall 2020).

Consequently, this study contributes to the understanding of psychosocial factors that interact to shape predispositions toward radicalization. It provides an integrated framework that could aid in the early detection of extremist tendencies and guide timely interventions to mitigate the risk of radicalization.

5. Practical Implications

The validation of the Ideological Radicalization Sensitivity Inventory (ISIR-14) offers relevant practical implications for risk assessment, intervention design, and future research in the field of ideological radicalization.

Risk assessment. The ISIR-14 provides a psychometrically sound tool for identifying psychological dimensions that increase vulnerability to radicalization, such as ideological superiority, perceived injustice, social disconnection, exposure to extremist content, and collective identity fusion. Its multidimensional approach enables early detection of individuals with heightened sensitivity to radicalizing influences. This is especially relevant in contexts characterized by “soft radicalization,” or, in terms of the two-pyramids model (McCauley and Moskalenko 2017), radicalization of opinion rather than action. Even in the absence of violent behavior, such processes can erode social cohesion, and validated, multidimensional instruments to assess this phenomenon remain scarce.

Intervention design. Findings from this study suggest that effective prevention programs should go beyond counter-narratives and address the psychosocial mechanisms that predispose individuals to extremism. Interventions that foster social inclusion, address perceived injustice, and challenge ideological absolutism may reduce susceptibility to extremist worldviews (Shafieioun and Haq 2023). The ISIR-14 can serve as a diagnostic tool to tailor interventions, helping practitioners focus efforts on the most salient risk dimensions for each context or population.

Research and theory development. The ISIR-14 opens new avenues for empirical research on the psychological pathways of radicalization. Its application in longitudinal designs may help track the development of radical attitudes over time and evaluate intervention outcomes. Moreover, its validation in a Mexican sample underscores the importance of culturally grounded tools. Broader cross-cultural adaptations of the ISIR-14 could enrich theoretical models by integrating individual, social, and contextual variables into a more comprehensive understanding of radicalization dynamics.

6. Limitations

While the results of this study support the validity and reliability of the ISIR-14, some limitations should be considered. Two of the identified factors (F4 and F5) exhibited internal consistency indices below the recommended threshold, suggesting a need to review and potentially refine the associated items to strengthen their coherence.

Although this study primarily focused on the design and validation of the instrument, the significant increases observed in certain scores during the test–retest phase indicate that future studies should incorporate covariates that assess contextual factors (e.g., political climate, exposure to polarizing information, experiences of social exclusion) to better understand score variability over time.

The results of the floor and ceiling effect analysis may reflect either limited variability in the sampled population or the need to refine items to better capture intermediate levels of these constructs.

Future studies are encouraged to perform multigroup confirmatory factor analyses (MGCFAs) to examine the measurement invariance of the ISIR-14 across key demographic groups such as gender, educational level, and age. This would allow for the assessment of whether the factorial structure operates equivalently across these populations.

As with all self-report-based research, responses may be subject to social desirability bias—namely, a tendency to provide overly positive self-descriptions that interfere with the accuracy of responses to questionnaire items (Paulhus 2002). This bias is particularly relevant when dealing with sensitive topics such as ideological radicalization. For example, the observed association between sensitivity to injustice and radicalization tendencies may partially reflect socially desirable responding rather than genuine psychological dispositions. In sociopolitical environments characterized by high levels of insecurity or polarization, such as Mexico, participants may be more inclined to downplay socially disapproved attitudes or exaggerate socially valued ones. Future research should consider this potential limitation by including control items to detect response patterns indicative of desirability bias or by incorporating validated social desirability scales to assess and account for its relationship with ISIR-14 scores (Paulhus 2002). Additionally, it remains important—as in the present study—to ensure participant anonymity, which has been shown to reduce social desirability bias (Krumpal 2013).

Finally, this study also presents several methodological limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the use of convenience sampling may limit the representativeness of the sample and, consequently, the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study was conducted within a specific cultural context—Mexican society—which may shape how individuals perceive and respond to items related to ideological radicalization. Therefore, caution should be exercised when attempting to extrapolate the results to other cultural or national contexts. Third, the cross-sectional design precludes any causal inference regarding the relationships between variables. Although this limitation is common in psychometric validation studies, which prioritize measurement quality over causal analysis, future research could further explore the causal structure of the constructs measured by the ISIR-14 using longitudinal designs or structural equation modeling approaches.

7. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence supporting the validity and reliability of the ISIR-14 as a psychometric tool for evaluating risk factors associated with radicalization across diverse cultural contexts. It offers an original contribution by addressing non-violent radicalization, thereby expanding its utility to countries without a history of extremist violence.

Moreover, the ISIR-14 is distinct from other instruments as it evaluates radicalization through explanatory variables, rather than solely focusing on extremist attitudes or behaviors. The five-factor structure identified—inclination to seek redress, social disconnection, ideological superiority, exposure to extreme ideologies, and collective identity—captures constructs previously linked to radicalization processes.

Although some factors present opportunities for improvement regarding internal consistency, the overall model demonstrated robust fit indices and significant relationships with other measures, supporting its convergent and concurrent validity. These findings highlight the potential of the ISIR-14 for future research and applied contexts, contributing to a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics underlying ideological radicalization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; methodology, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; validation, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; formal analysis, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; investigation, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; resources, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; data curation, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; writing—review and editing, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; supervision, J.C.P.-C. and I.G.; project administration, J.C.P.-C. and I.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the corresponding author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review of Universidad de las Américas Puebla (LPA3092 23 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Isabella Martínez and Diego Aguilar for their work in the partial collection of the initial sample for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos. 2016. Informe Relativo a Las Mejores Prácticas y Lecciones Extraídas Sobre Cómo La Protección y La Promoción de Los Derechos Humanos Contribuyen a La Prevención y Erradicación Del Extremismo Violento. A/HRC/33/29. Naciones Unidas. Asamblea General. Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g16/162/58/pdf/g1616258.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Arbuckle, James. L. 2022. Amos (Version 29). Chicago: IBM SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Paul. 2007. Structural Equation Modelling: Adjudging Model Fit. Personality and Individual Differences 42: 815–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Aaron T. 2002. Prisoners of Hate. Behaviour Research and Therapy 40: 209–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélanger, Jocelyn J., Hayat Muhammad, Manuel Moyano, Marc-André K. Lafrenière, Lindsy Richardson, Karyne Framand, Patrick McCaffery, and Noëmie Nociti. 2019. Radicalization Leading to Violence: A Test of the 3N Model. Frontiers in Psychiatry 10: 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besta, Tomasz, Marcin Szulc, and Michał Jaśkiewicz. 2015. Political Extremism, Group Membership and Personality Traits: Who Accepts Violence?—Extremismo Político, Pertenencia al Grupo y Rasgos de Personalidad: ¿Quién Acepta La Violencia? International Journal of Social Psychology: Revista de Psicología Social 30: 563–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugré, Constant D. 2005. Understanding Injustice-Related Aggression in Organizations: A Cognitive Model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 16: 1120–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhui, Kamaldeep, Nasir Warfa, and Edgar Jones. 2015. Sympathies for Radicalisation Scale. Worcester: American Psychological Association (APA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizer, George Y. 2020. Who’s Bothered by an Unfair World? The Emotional Response to Unfairness Scale. Personality and Individual Differences 159: 109882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørgo, Tore, ed. 2006. Root Causes of Terrorism: Myths, Reality, and Ways Forward. Reprint. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, Godfred O., Edward A. Frongillo, Torsten B. Neilands, Hugo R. Melgar-Quiñonez, and Sera L. Young. 2018. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Frontiers in Public Health 6: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borum, Randy. 2011. Radicalization into Violent Extremism I: A Review of Social Science Theories. Journal of Strategic Security 4: 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Marilynn B., and Wendi Gardner. 1996. Who Is This ‘We’? Levels of Collective Identity and Self Representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chory-Assad, Rebecca M., and Michelle L. Paulsel. 2004. Classroom Justice: Student Aggression and Resistance as Reactions to Perceived Unfairness. Communication Education 53: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmow, Caitlin, Bettina Rottweiler, and Paul Gill. 2022. EXPO-12: Development and Validation of the Exposure to Violent Extremism Scale. Psychology of Violence 12: 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, Maura. 2017. Determining the Role of the Internet in Violent Extremism and Terrorism: Six Suggestions for Progressing Research. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40: 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, Manni. 2016. Radicalization Revisited: Violence, Politics and the Skills of the Body. International Affairs 92: 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, Caroline, Bruno Domingo, Nicolas Amadio, Rachel Sarg, and Massil Benbouriche. 2024. The Significance Quest Theory and the 3N Model: A Systematic Review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 65: 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, Jean. 2024. Pourquoi les convictions morales facilitent le dogmatisme, l’intolérance et la violence. L’Évolution Psychiatrique 89: 227–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pino-Brunet, Natalia, Isabel Hombrados-Mendieta, Luis Gómez-Jacinto, Alba García-Cid, and Mario Millán-Franco. 2021. Systematic Review of Integration and Radicalization Prevention Programs for Migrants in the US, Canada, and Europe. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 606147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dono, Marcos, Mónica Alzate, and José Manuel Sabucedo. 2024. Slicing the Gordian Knot of Political Extremism: Issues and Potential Solutions Regarding Its Conceptualization and Terminology. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 12: 140–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doosje, Bertjan, Annemarie Loseman, and Kees Van Den Bos. 2013. Determinants of Radicalization of Islamic Youth in the Netherlands: Personal Uncertainty, Perceived Injustice, and Perceived Group Threat. Journal of Social Issues 69: 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doosje, Bertjan, Annemarie Loseman, Kees Van Den Bos, Allard R. Feddes, and Liesbeth Mann. 2012. ‘My In-group Is Superior!’: Susceptibility for Radical Right-wing Attitudes and Behaviors in Dutch Youth. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 5: 253–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, Neelam, Tamkeen Saleem, Bushra Hassan, and Nazia Iqbal. 2021. Development and Validation of Risk Assessment Tool for Extremism (RATE) for Young People in Pakistan. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 27: 240–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldor, David S., Maria H. Chavez, Karine Lindholm, Sander Vassanyi, Michelle O. I. Badiane, Petter Frøysa, Christian A. P. Haugestad, Kemal Yaldizli, and Jonas R. Kunst. 2022. Resilience against Radicalization and Extremism in Schools: Development of a Psychometric Scale. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 980180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmelkamp, Julie, Jessica J. Asscher, Inge B. Wissink, and Geert Jan J. M. Stams. 2020. Risk Factors for (Violent) Radicalization in Juveniles: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior 55: 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddes, Allard R., Liesbeth Mann, and Bertjan Doosje. 2015. Increasing Self-esteem and Empathy to Prevent Violent Radicalization: A Longitudinal Quantitative Evaluation of a Resilience Training Focused on Adolescents with a Dual Identity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 45: 400–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán Jiménez, Jaime Sebastián, José Luis Calderón Mafud, Omar Sánchez-Armáss Cappello, and Mario Guzmán Sescosse. 2022. Exposición y Desensibilización a La Violencia En Jóvenes Mexicanos En Distintos Contextos Sociales. Acta de Investigación Psicológica 12: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudette, Tiana, Ryan Scrivens, Garth Davies, and Richard Frank. 2021. Upvoting Extremism: Collective Identity Formation and the Extreme Right on Reddit. New Media & Society 23: 3491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidron, Noam, and Peter A. Hall. 2020. Populism as a Problem of Social Integration. Comparative Political Studies 53: 1027–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, José Luis, Jorge Santos-Hermoso, Ángel Gómez, José Luis López-Novo, Sara Buquerín-Pascual, Florencia Pozuelo-Rubio, Carlos Fernández-Gómez, and Sandra Chiclana. 2024. Detection of Violent Radicalism of Jihadist Aetiology Tool-3. Worcester: American Psychological Association (APA). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Hussam, Padmini Srinivasan, and Rishab Nithyanand. 2022. Making a Radical Misogynist: How Online Social Engagement with the Manosphere Influences Traits of Radicalization. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 6: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, Mark S., and Ramón Fredrik Johan Spaaij. 2017. The Age of Lone Wolf Terrorism. Studies in Transgression. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henríquez Henríquez, Diego Tomás, Alfonso Urzúa Morales, and Wilson López López. 2020. Fusión de Identidad: Una Revisión Sistemática. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 23: 383–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, John. 2008. From Profiles to Pathways and Roots to Routes: Perspectives from Psychology on Radicalization into Terrorism. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 618: 80–94. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan, John G. 2014. The Psychology of Terrorism, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, John L. 1965. A Rationale and Test for the Number of Factors in Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 30: 179–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, Shanto, Gaurav Sood, and Yphtach Lelkes. 2012. Affect, Not Ideology. Public Opinion Quarterly 76: 405–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, Sara, Carl Philipp Schröder, Laura-Romina Goede, Lena Lehmann, Luisa Hauff, and Andreas Beelmann. 2020. Observer Sensitivity and Early Radicalization to Violence Among Young People in Germany. Social Justice Research 33: 308–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansma, Amarins, Kees Van Den Bos, and Beatrice A. De Graaf. 2022. Unfairness in Society and Over Time: Understanding Possible Radicalization of People Protesting on Matters of Climate Change. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 778894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasko, Katarzyna, David Webber, Arie W. Kruglanski, Michele Gelfand, Muh Taufiqurrohman, Malkanthi Hettiarachchi, and Rohan Gunaratna. 2020. Social Context Moderates the Effects of Quest for Significance on Violent Extremism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 118: 1165–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasko, Katarzyna, Gary LaFree, and Arie W. Kruglanski. 2017. Quest for Significance and Violent Extremism: The Case of Domestic Radicalization. Political Psychology 38: 815–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugl, Irina, Friedrich Lösel, Doris Bender, and Sonja King. 2020. Psychosocial Prevention Programs against Radicalization and Extremism: A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Evaluations. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context 13: 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Daniel B., Robert J. Homant, and Michael R. Homant. 2003. Perception of Injustice as a Predictor of Support for Workplace Aggression. Journal of Business and Psychology 18: 323–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Mohammad Nisar, Mohammad Bashir Khan, Tasneem Fatima, and Syed Zulfiqar Ali Shah. 2019. The Underlying Mechanism between Perceived Organizational Injustice and Deviant Workplace Behaviors: Moderating Role of Personality Traits. Asia Pacific Management Review 24: 201–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, Daniel. 2023. ‘The Fighting Made Me Feel Alive’: Women’s Motivations for Engaging in Left-Wing Terrorism: A Thematic Analysis. Terrorism and Political Violence 35: 553–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, Arie W., and Edward Orehek. 2011. The Role of the Quest for Personal Significance in Motivating Terrorism. In The Psychology of Social Conflict and Aggression. London: Psychology Press, pp. 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, Arie W., Erica Molinario, Katarzyna Jasko, David Webber, N. Pontus Leander, and Antonio Pierro. 2022a. Significance-Quest Theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science 17: 1050–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruglanski, Arie W., Erica Molinario, Molly Ellenberg, and Gabriele Di Cicco. 2022b. Terrorism and Conspiracy Theories: A View from the 3N Model of Radicalization. Current Opinion in Psychology 47: 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruglanski, Arie W., Katarzyna Jasko, David Webber, Marina Chernikova, and Erica Molinario. 2018. The Making of Violent Extremists. Review of General Psychology 22: 107–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, Arie W., Katarzyna Jasko, Marina Chernikova, Michelle Dugas, and David Webber. 2017. To the Fringe and Back: Violent Extremism and the Psychology of Deviance. American Psychologist 72: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruglanski, Arie W., Michele J. Gelfand, Jocelyn J. Bélanger, Anna Sheveland, Malkanthi Hetiarachchi, and Rohan Gunaratna. 2014. The Psychology of Radicalization and Deradicalization: How Significance Quest Impacts Violent Extremism. Political Psychology 35: 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpal, Ivar. 2013. Determinants of Social Desirability Bias in Sensitive Surveys: A Literature Review. Quality & Quantity 47: 2025–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Justin E., Kevin McCaffree, and F. LeRon Shults. 2021. Is Radicalization Reinforced by Social Media Censorship? arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, Charles H. 1975. A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity. Personnel Psychology 28: 563–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, Roberto M., Josep García-Coll, José María Martín-Criado, and Manuel Moyano. 2023. Impact of Psychological and Structural Factors on Radicalization Processes: A Multilevel Analysis from the 3N Model. Psychology of Violence 13: 479–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, Roberto M., Manuel Moyano, Jocelyn J. Bélanger, and Humberto M. Trujillo. 2021. The Role of Vulnerable Environments in Support for Homegrown Terrorism: Fieldwork Using the 3N Model. Aggressive Behavior 47: 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, Friedrich, Sonja King, Doris Bender, and Irina Jugl. 2018. Protective Factors Against Extremism and Violent Radicalization: A Systematic Review of Research. International Journal of Developmental Science: Biopsychosocial Mechanisms of Change, Human Development, and Psychopathology Perspectives from Psychology, Neuroscience, and Genetics 12: 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, Robert C., Keith F. Widaman, Shaobo Zhang, and Sehee Hong. 1999. Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods 4: 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, Clark. 2022. The ABC Model: Commentary from the Perspective of the Two Pyramids Model of Radicalization. Terrorism and Political Violence 34: 451–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, Clark, and Sophia Moskalenko. 2011. Friction: How Radicalization Happens to Them and Us. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, Clark, and Sophia Moskalenko. 2014. Toward a Profile of Lone Wolf Terrorists: What Moves an Individual from Radical Opinion to Radical Action. Terrorism and Political Violence 26: 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, Clark, and Sophia Moskalenko. 2017. Understanding Political Radicalization: The Two-Pyramids Model. American Psychologist 72: 205–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, Fathali M. 2005. The Staircase to Terrorism: A Psychological Exploration. American Psychologist 60: 161–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinario, Erica, Andrey Elster, Laura Prislei, and Arie W. Kruglanski. 2025. Quest for Significance as a Path to Peaceful Effortful Actions: The Moderating Role of Values. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 55: 551–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mølmen, Guri Nordtorp, and Jacob Aasland Ravndal. 2023. Mechanisms of Online Radicalisation: How the Internet Affects the Radicalisation of Extreme-Right Lone Actor Terrorists. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 15: 463–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, Atte, Magdalena Celuch, Reetta Oksa, and Iina Savolainen. 2024. Online Communities Come with Real-World Consequences for Individuals and Societies. Communications Psychology 2: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, Simon, and Preben Bertelsen. 2018. Capturing Violent Radicalization: Developing and Validating Scales Measuring Central Aspects of Radicalization. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 59: 653–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, Delroy L. 2002. Socially Desirable Responding: The Evolution of a Construct. In The Role of Constructs in Psychological and Educational Measurement. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlović, Tomislav, Sophia Moskalenko, and Clark McCauley. 2024. Two Classes of Political Activists: Evidence from Surveys of U.S. College Students and U.S. Prisoners. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 16: 227–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagos-Corzo, Julio C., Alejandra A. Antonio, Gabriel Dorantes-Argandar, and Raúl J. Alcázar-Olán. 2019. Psychometric Properties and Development of a Scale Designed to Evaluate the Potential of Predatory Violent Behavior. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfundmair, Michaela, and Luisa A. M. Mahr. 2023. How Group Processes Push Excluded People into a Radical Mindset: An Experimental Investigation. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 26: 1289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, Mark J., Sucharita Belavadi, and Michael A. Hogg. 2020. When Social Identity-Defining Groups Become Violent. In The Handbook of Collective Violence: Current Developments and Understanding. Edited by Carol A. Ireland, Michael S. Lewis, Anthony C. Lopez and Jane L. Ireland. Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Taylor Group, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts-Ingleson, Elise, and Wesley McCann. 2023. The Link between Misinformation and Radicalisation: Current Knowledge and Areas for Future Inquiry. Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism Studies 17: 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottweiler, Bettina, and Paul Gill. 2022. Individual Differences in Personality Moderate the Effects of Perceived Group Deprivation on Violent Extremism: Evidence from a United Kingdom Nationally Representative Survey. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 790770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, Cécile, Youssef Oulhote, Vanessa Lecompte, Abdelwahed Mekki-Berrada, Ghayda Hassan, and Habib El Hage. 2021. Collective Identity, Social Adversity and College Student Sympathy for Violent Radicalization. Transcultural Psychiatry 58: 654–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcella, Akimi, Ruairi Page, and Vivek Furtado. 2016. Terrorism, Radicalisation, Extremism, Authoritarianism and Fundamentalism: A Systematic Review of the Quality and Psychometric Properties of Assessments. Edited by Takeru Abe. PLoS ONE 11: e0166947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, Sandy, Caitlin Clemmow, Bettina Rottweiler, and Paul Gill. 2024. Distinct Patterns of Incidental Exposure to and Active Selection of Radicalizing Information Indicate Varying Levels of Support for Violent Extremism. Edited by Daniel W. Snook. PLoS ONE 19: e0293810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, Bart, Lasse Lindekilde, Stefan Malthaner, Francis O’Connor, Paul Gill, and Noémie Bouhana. 2019. End of the Lone Wolf: The Typology That Should Not Have Been. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 42: 771–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafieioun, Delaram, and Hina Haq. 2023. Radicalization from a Societal Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1197282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Ayaz Ali, Nelofar Ehsan, and Hina Malik. 2019. Jihad or Revenge: Theorizing Radicalization in Pashtun Tribal Belt along the Border of Afghanistan. Global Political Review IV: 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, Chris G., Marc S. Wilson, and John Duckitt. 2007. Effects of Dangerous and Competitive Worldviews on Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation over a Five-Month Period. Political Psychology 28: 357–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie White Stephan. 2000. An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice. In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, Cass R. 2018. #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, William B., Ángel Gómez, John F. Dovidio, Sonia Hart, and Jolanda Jetten. 2010. Dying and Killing for One’s Group: Identity Fusion Moderates Responses to Intergroup Versions of the Trolley Problem. Psychological Science 21: 1176–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, Caroline B., Sandra D. M. Bot, Michael R. De Boer, Daniëlle A. W. M. Van Der Windt, Dirk L. Knol, Joost Dekker, Lex M. Bouter, and Henrica C. W. De Vet. 2007. Quality Criteria Were Proposed for Measurement Properties of Health Status Questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 60: 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Jamovi Project. 2024. Jamovi. The Jamovi Project. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Toner, Kaitlin, Mark R. Leary, Michael W. Asher, and Katrina P. Jongman-Sereno. 2013. Feeling Superior Is a Bipartisan Issue: Extremity (Not Direction) of Political Views Predicts Perceived Belief Superiority. Psychological Science 24: 2454–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trip, Simona, Carmen Hortensia Bora, Mihai Marian, Angelica Halmajan, and Marius Ioan Drugas. 2019. Psychological Mechanisms Involved in Radicalization and Extremism. A Rational Emotive Behavioral Conceptualization. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristán-López, Agustín. 2008. Modificación al Modelo de Lawshe Para El Dictamen Cuantitativo de La Validez de Contenido de Un Instrumento Objetivo [Modification of Lawshe’s Model for Quantitative Judgement of the Content Validity of an Objective Instrument]. Avances En Medición 6: 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Troian, Jais, Ouissam Baidada, Thomas Arciszewski, Themistoklis Apostolidis, Elif Celebi, and Taylan Yurtbakan. 2019. Evidence for Indirect Loss of Significance Effects on Violent Extremism: The Potential Mediating Role of Anomia. Aggressive Behavior 45: 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, Humberto M., Ferrán Alonso, José Miguel Cuevas, and Manuel Moyano. 2018. Evidencias empíricas de manipulación y abuso psicológico en el proceso de adoctrinamiento y radicalización yihadista inducida. Revista de Estudios Sociales 1: 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bos, Kees. 2020. Unfairness and Radicalization. Annual Review of Psychology 71: 563–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, and André P. M. Krouwel. 2019. Psychological Features of Extreme Political Ideologies. Current Directions in Psychological Science 28: 159–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, David, Maxim Babush, Noa Schori-Eyal, Anna Vazeou-Nieuwenhuis, Malkanthi Hettiarachchi, Jocelyn J. Bélanger, Manuel Moyano, Humberto M. Trujillo, Rohan Gunaratna, Arie W. Kruglanski, and et al. 2018. The Road to Extremism: Field and Experimental Evidence That Significance Loss-Induced Need for Closure Fosters Radicalization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 114: 270–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesselmann, Eric D., Eboni Bradley, Rachel S. Taggart, and Kipling D. Williams. 2023. Exploring Social Exclusion: Where We Are and Where We’re Going. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 17: e12714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, Leah. 2020. The Language of Radicalization: Female Internet Recruitment to Participation in ISIS Activities. Terrorism and Political Violence 32: 506–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfowicz, Michael, David Weisburd, and Badi Hasisi. 2021. Does Context Matter? European-Specific Risk Factors for Radicalization. Monatsschrift Für Kriminologie Und Strafrechtsreform 104: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfowicz, Michael, Yael Litmanovitz, David Weisburd, and Badi Hasisi. 2020. A Field-Wide Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Putative Risk and Protective Factors for Radicalization Outcomes. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 36: 407–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. 2013. Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Ferney-Voltaire: World Medical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Youngblood, Mason. 2020. Extremist Ideology as a Complex Contagion: The Spread of Far-Right Radicalization in the United States between 2005 and 2017. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).