Exploring Barriers and Enablers for Women Entrepreneurs in Urban Ireland: A Qualitative Study of the Greater Dublin Area

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. An Overview of Women and Entrepreneurial Leadership

2.2. Women Entrepreneurial Leadership Dynamics in Early-Stage Companies

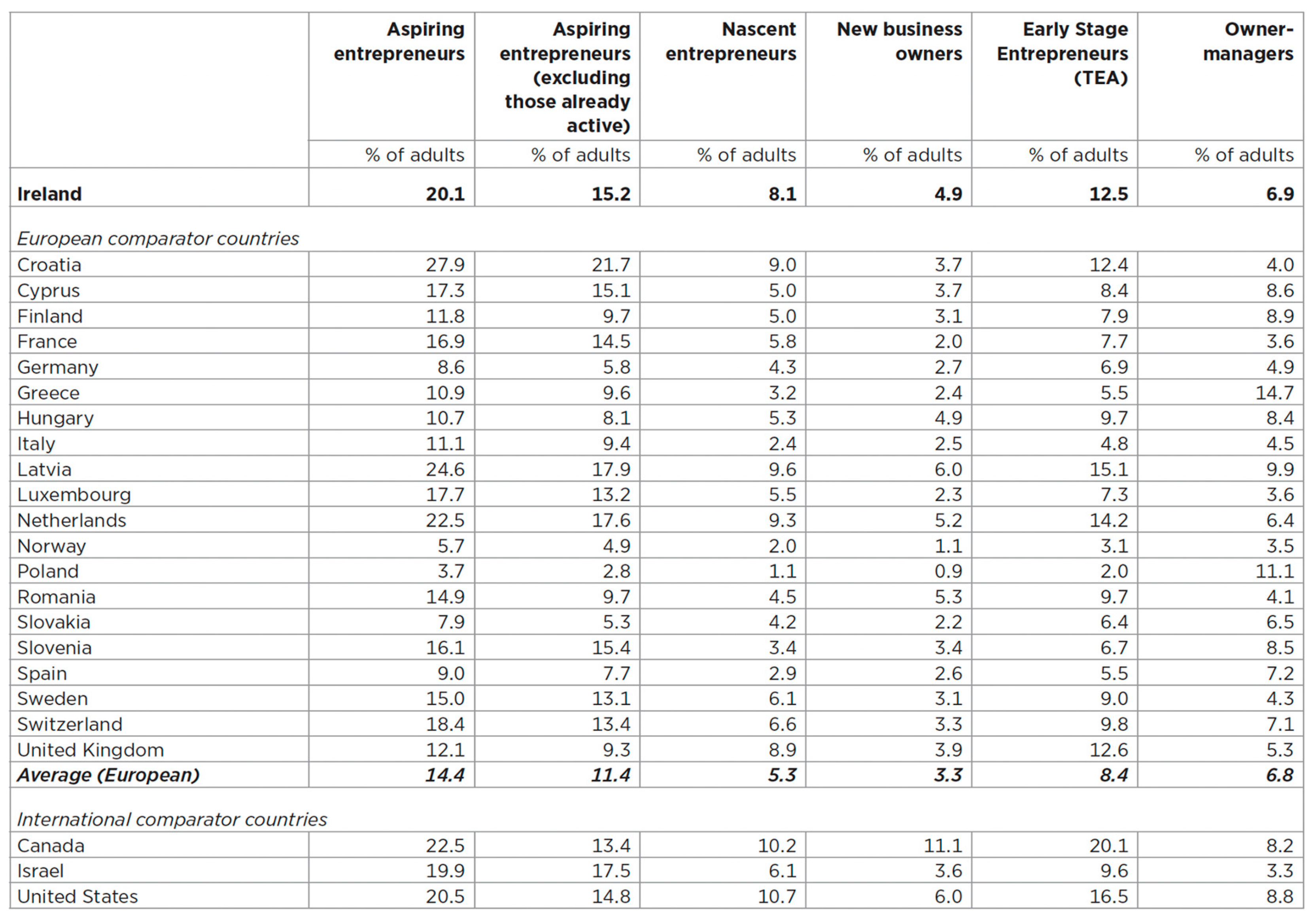

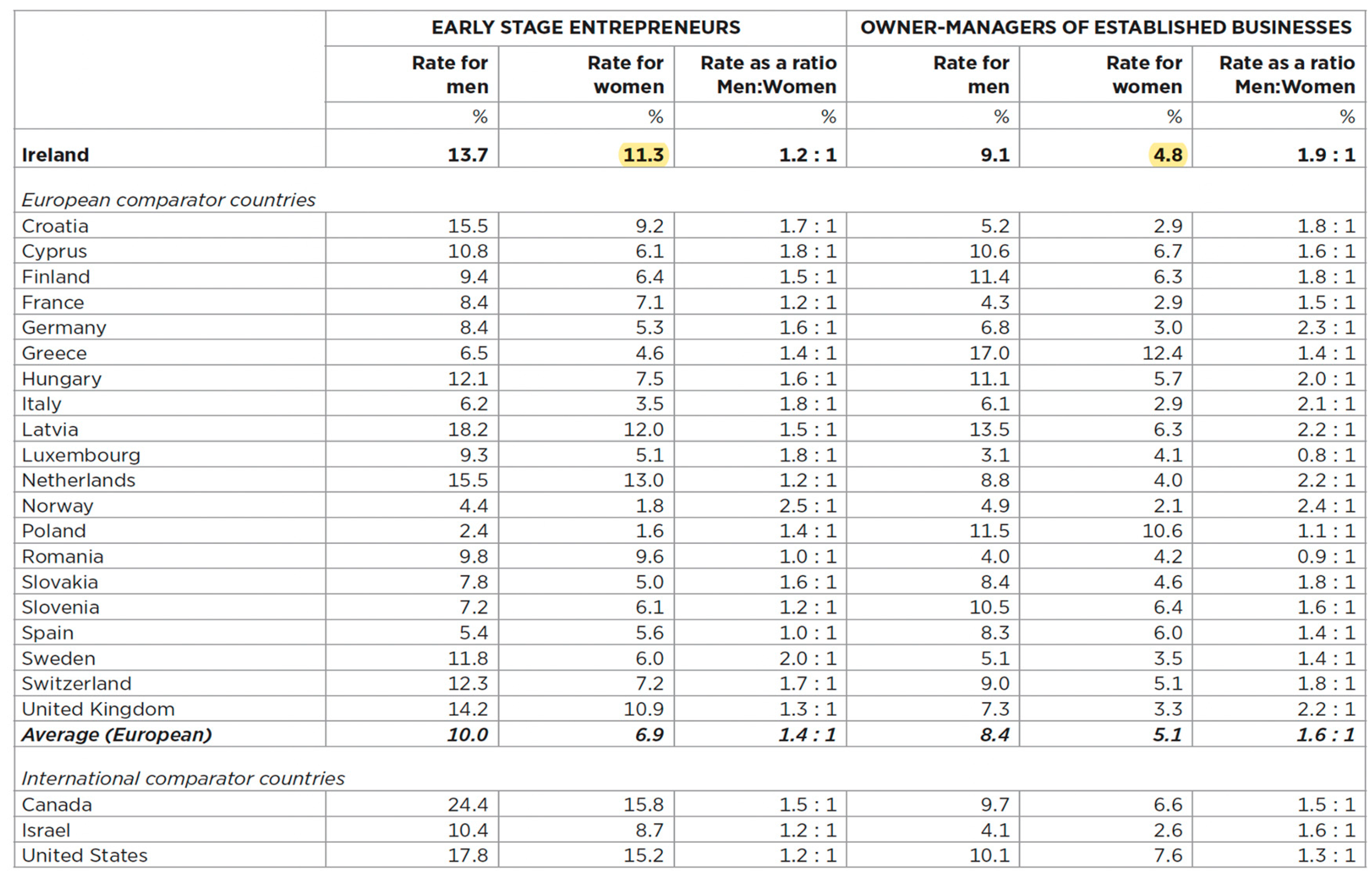

2.3. Contextualizing Women’s Entrepreneurship in Ireland

2.4. Stewart’s Role Demand–Constraint–Choice Model

2.5. Women-Led Entrepreneurism in Ireland

2.6. Challenges Faced by Irish Women Entrepreneurs

3. Research Methods and Approach

3.1. Research Criterium

3.2. Research Process

4. Research Findings and Analysis

4.1. Stewart’s DCC Framework Analysis

4.2. Analyzing Role Demands

I have set goals and ambitions that I constantly visit and revisit for my business. For as long as I’ve worked for myself, I have never managed to get all my clients online in line with my fitting into their goals and ambitions.(Interviewee 1)

Oh, for me, in the past, [goals and objectives] have been very customer-focused. We would work off what our customers wanted and get their feedback, which would also align with my values.(Interviewee 3)

There’s not a lot of financial support. We have what’s called a local Enterprise office, which will help you set up your [business] start up, your own business and your business plans and setting goals, getting funding if you need it, from banks and microloans and things like that. But there are good women in business groups here.(Interviewee 12)

I’m a mother of 3 kids. So that’s very demanding, you know. And so it’s been able to have the support of my husband. You know, there to be able to do a school pick up, or whenever I just can’t be there for the kids.(Interviewee 8)

So, I had acquired this business, and trying to grow it was actually a constant challenge because I was struggling to get access to it. This is way before nowadays, we all think. And the funny thing is that for my international recruitment agency, I’m the only one that lives in Ireland.(Interviewee 11)

… if you’re watching those numbers move up, how can you get completely engrossed in that and like challenge yourself to just keep growing the numbers based on the analytics?(Interviewee 14)

I’ve got lots of support. There’s nice support here. Now, because it’s seen as a service industry. There’s not a lot of financial support.(Interviewee 6)

… I remember having one particular; she reached the director level in another company that I owned, and I was fortunate enough to sell out a number of years back, which treated me well financially.(Interviewee 11)

There are people who thought there were people who had given up the security of a salary to take a risk and then hopefully take part in a reward, financial reward…But I didn’t actually think of that at all in those days. I had access to financing and funding if I wanted it. So, [being in business], it wasn’t about that.(Interviewee 12)

I think I’m very outcome-focused. So, if what I’m hearing sounds like the outcome sounds all right, even if it’s coming from somebody who might not have the business maturity to know how actually to do it.(Interviewee 3)

I don’t have a leadership role there yet. But I can see [its importance and] my entrepreneurial leadership spirit coming through because I’ve identified a new diversification [and inclusion] strategy for the company.(Interviewee 5)

… you do need support. And we’ve kind of ploughed in our own resources and money. But another very important thing is you [as a leader].(Interviewee 6)

I think this is where you have to see a range of what I call supporters, mentors that you can discuss the ways around.(Interviewee 5)

[I am] a great believer in having, you know, a support group, I think, for women particularly. It’s very important. and that you talk things through.(Interviewee 7)

I think resilience is really important, but I certainly found great support. People might not even think their supporters are mentors or whatever.(Interviewee 14)

And again, you know, I was always very lucky in that sense, and you know my husband’s very, very supportive, but my parents as well.(Interviewee 14)

My husband and kids were happy, but whether they were happy, they understood [and supported] us, and you know we were able to manage it. But it was a... It was a difficult time.(Interviewee 5)

Okay, so if you are a separated woman, you are in limbo because you couldn’t make it to the break. Women couldn’t really work, and there were certain jobs. There were marriage bars, all this type of stuff. So, a married woman had no support.(Interviewee 6)

We didn’t get changed from the eighties, so a married woman’s dumb as I was ever your husband was. So, if your husband went to the UK. You are now in the UK even though you weren’t physically there. And so what you had to do was declare yourself a deserted wife, and the stigma and all of the things that came with that.(Interviewee 7)

4.3. Role Constraints

Funding! [The] challenge for me is funding, trying to access either grants or investments and to, you know, move the business to the next stage of its development. So, I find that funding is difficult. Accessing that fund is difficult, and I haven’t. You know some people would... Well, there are statistics out saying that 30 percent [do get funded in Ireland.(Interviewee 7)

It’s difficult [for me to have] autonomy. So, [I am] not sure. I’m not sure I’m not sure how to answer. That wouldn’t be an honest thing at the minute.(Interviewee 8)

Well, we can actually choose to get stuck in that [choice between business and family], or we can realize that on one salary, [I am] feeding a family…(Interviewee 2)

[Regarding motivations] It was also like the drive and the values. The values of being there together as a family unit, and all that. So it’s the drive, but it’s also the values, in my estimation.(Interviewee 3)

We have a family business here, which I’m in the office of right now… …So I think my entrepreneurial spirit came from my family.(Interviewee 5)

4.4. Role Choices

Oh, yeah, [when it comes to choices] I’d say time plays a big part, but I also have to align it with my overall goal. So, my goal is definitely to grow my company. I have my own company, and I would like shares of my dad’s business that I’m currently working in.(Interviewee 13)

[When it comes to choices] It just comes down to the end goal and where you want to be.(Interviewee 4)

[Regarding choices] I would say, yeah, the safety of employees and our employees’ well-being [is my priority].(Interviewee 6)

[Making choices is complex because] I don’t have the finances behind me at the minute to do that. But so that’s okay. That is going to be something we’re gonna look at. But we’re doing it. We’re looking at a roadmap to get there.(Interviewee 8)

We’d grown it over five years and sold it for, I’m sorry, I sold my share for a lot of money in it for a very short space of time. So, I was feeling like the queen bee, which was completely ridiculous.(Interviewee 1)

Sharing my knowledge, I suppose, even sharing with the younger [ones]. You know, women. You know, instilling that confidence that you can do it if you have the passion and you really want it.(Interviewee 8)

I suppose, like knowledge is sometimes, it can sometimes [be] a constraint as well because I do need to do a lot of research for both and make sure to share it.(Interviewee 4)

5. Research Discussion, Limitations, Conclusions, and Recommendations

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Limitations and Further Research

5.3. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Access to Funding and Resources—Facilitate increased access to financial resources and funding for women entrepreneurs, addressing existing gender inequality and disparities in venture capital and traditional financing while implementing and promoting targeted financial programs and incentives to support women-led businesses (Stephens et al. 2022; Henry et al. 2022; Johnston et al. 2023).

- Educational and Networking Initiatives—Develop and expand educational programs that focus on entrepreneurship skills and business management, specifically for women, while fostering networking opportunities and mentorship programs to connect aspiring and established women entrepreneurs with experienced professionals (Kelly and McAdam 2023; Nziku and Bikorimana 2023).

- Community Engagement and Awareness—Foster community engagement to build a supportive ecosystem for women entrepreneurs while promoting awareness of the significance of gender equality, diversity, and inclusiveness in entrepreneurship and emphasizing success stories to inspire others (Henry and Lewis 2023).

- Corporate Partnerships—Foster collaborations between women entrepreneurs and established businesses while promoting corporate partnerships that offer mentorship, procurement opportunities, and access to larger markets (Johnston et al. 2023; Korinek and van Lieshout 2023).

- Cultural and Mindset Shifts—Work towards shifting societal attitudes and stereotypes regarding women in leadership and entrepreneurship while promoting a cultural environment that celebrates and values the contributions of women entrepreneurs (Hamouda et al. 2022; Hurtado Mercado 2023).

- Policy Advocacy and Support—Advocate for policies that promote gender equality and eliminate barriers for women in entrepreneurship while implementing supportive policies, such as flexible working arrangements and family-friendly measures, to enable a better work-life balance for women entrepreneurs (Henry et al. 2022).

- Promoting Digital Literacy—Enhance digital literacy programs to empower women entrepreneurs to leverage technology for business growth while promoting awareness and training on digital marketing and e-commerce strategies (Faugoo and Onaga 2022).

- Research and Data Collection—Invest in initiatives focusing on understanding the specific challenges faced by women entrepreneurs in Ireland while regularly collecting and analyzing gender-disaggregated data to inform evidence-based policymaking.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GEM | Global Entrepreneurship Monitor |

| DCC | Demand–Constraint–Choice (Framework) |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| VC | Venture Capital |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| MS | Microsoft (Teams) |

References

- Ababa, Adis. 2021. Social Assessment for The Women Entrepreneurship Development Project Additional Financing (Wedp Af). Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Abouzahr, Katie, Matt Krentz, John Harthorne, and Frances Brooks Taplett. 2018. Why Women-Owned Startups Are a Better Bet. Boston: Boston Consulting Group. [Google Scholar]

- Abrar ul Haq, Muhammad, Surjit Victor, and Farheen Akram. 2021. Exploring the motives and success factors behind female entrepreneurs in India. Quality & Quantity 55: 1105–32. [Google Scholar]

- Астанoва, C. Y. 2020. Current Situation and Prospects for the Development of Female Entrepreneurship in Kyrgyzstan. Наука, нoвые технoлoгии и иннoвации Кыргызстана 1: 82–5. [Google Scholar]

- Adewuyi, Oluwabukola. 2021. An Investigation into the Social and Cultural Impediments to Female Entrepreneurship in Ireland. Ph.D. dissertation, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Adikaram, Arosha, and Ruwaiha Razik. 2023. Femininity penalty: Challenges and barriers faced by STEM woman entrepreneurs in an emerging economy. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 15: 1113–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, Sucheta, Usha Lenka, Kanhaiya Singh, Vivek Agrawal, and Anand Mohan Agrawal. 2020. A qualitative approach towards crucial factors for sustainable development of women social entrepreneurship: Indian cases. Journal of Cleaner Production 274: 123135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağır, Seven. 2020. Nineteenth-Century female entrepreneurship in Turkey. In Female Entrepreneurs in the Long Nineteenth Century: A Global Perspective. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 405–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ahl, Helene, and Susan Marlow. 2021. Exploring the false promise of entrepreneurship through a postfeminist critique of the enterprise policy discourse in Sweden and the UK. Human Relations 74: 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmetaj, Bardhyl, Alba Demneri Kruja, and Eglantina Hysa. 2023. Women entrepreneurship: Challenges and perspectives of an emerging economy. Administrative Sciences 13: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Matroushi, Huda, Fauzia Jabeen, Ayesha Matloub, and Muhammad Tehsin. 2020. Push and pull model of women entrepreneurship: Empirical evidence from the UAE. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 11: 588–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alecchi, Beatrice Avolio. 2020. Toward realizing the potential of Latin America’s women entrepreneurs: An analysis of barriers and challenges. Latin American Research Review 55: 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kwifi, Osama Sam, Tran Tien Khoa, Viput Ongsakul, and Zafar U. Ahmed. 2020. Determinants of female entrepreneurship success across Saudi Arabia. Journal of Transnational Management 25: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamahery, A., and M. Qamruzzaman. 2022. Do access to finance, technical know-how, and financial literacy offer women em-powerment through women’s entrepreneurial development? Frontiers in Psychology 12: 776844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolevič, Jolanta. 2023. The economic empowerment of women as a factor contributing to the prevention of domestic violence. In Gender-Based Violence and the Law. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 150–67. [Google Scholar]

- Armie, Madalina. 2022. Change, Stasis and Celtic Tiger Ireland in the Short Stories of There Are Little Kingdoms (2007) by Kevin Barry. Estudios Irlandeses 17: 130–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, Muhammad, Mariam Farooq, Muhammad Atif, and Omer Farooq. 2021. A motivational theory perspective on entrepreneurial intentions: A gender comparative study. Gender in Management: An International Journal 36: 221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgary, Nader H., Emerson A. Maccari, Heloisa C. Hollnagel, and Ricardo L. P. Bueno. 2024. Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Sustainable Growth: Theory, Policy, and Practice. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Abbye. 2020. Borrowing Equality. Columbia Law Review 120: 1403–70. [Google Scholar]

- Aurangzeb, Wajeeha, M. N. S. Abbasi, and Sehrish Kashan. 2023. Unveiling the impact of gaslighting on female academic leadership: A qualitative phenomenological study. Contemporary Issues in Social Sciences and Management Practices 2: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotoye, Yemisi F., and Christopher E. Stevens. 2023. Gendered Perceptions of Spousal Support and Entrepreneurial Intention: Evidence from Nigeria. American Journal of Management 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ayentimi, Desmond Tutu. 2020. The 4IR and the challenges for developing economies. In Developing the Workforce in an Emerging Economy. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ayesha, Ivonne, Finny Redjeki, Acai Sudirman, Avid Leonardo Sari, and Diena Fanny Aslam. 2021. Behavior of Female Entrepreneurs in Tempe Small Micro Enterprises in Tasikmalaya Regency, West Java as Proof of Gender Equality Against AEC. Paper presented at 2nd Annual Conference on Blended Learning, Educational Technology and Innovation (ACBLETI 2020), Online, October 23–24; Dordrecht: Atlantis Press, pp. 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Azadnia, Amir Hossein, Simon Stephens, Pezhman Ghadimi, and George Onofrei. 2022. A comprehensive performance measurement framework for business incubation centres: Empirical evidence in an Irish context. Business Strategy and the Environment 31: 2437–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, Hasnan, V. Deepa, Hamzah Elrehail, Marc Poulin, and Faizan Ashraf Mir. 2023. Self-directed learning motivational drivers of working professionals: Confirmatory factor models. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 13: 625–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, Mark, and Justin W. Evans. 2023. Growing Entrepreneurial Communities. Journal of Business & Entrepreneurship 33: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bannò, Mariasole, Giorgia Maria D’Allura, Graziano Coller, and Celeste Varum. 2023. Men are from Mars, women are from Venus: On lenders’ stereotypical views and the implications for a firm’s debt. Journal of Management and Governance 27: 651–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramov, Vugar, Nigar Islamli, and Emin Mammadov. 2023. Assessment of Gender Equality & Women’s Empowerment in the Post-Soviet Space. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4323803 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Begum, Saira, Muhammad Ashfaq, Enjun Xia, and Usama Awan. 2022. Does green transformational leadership lead to green innovation? The role of green thinking and creative process engagement. Business Strategy and the Environment 31: 580–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, Muhammad, Shafaq Chaudhry, Hina Amber, Muhammad Shahid, Shoaib Aslam, and Khuram Shahzad. 2021. Entrepreneurial leadership and employees’ proactive behaviour: Fortifying self-determination theory. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7: 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birsan, Alina, Raluca Ghinea, and Lorian Vintila. 2022. Female entrepreneurship model, a sustainable solution for crisis resilience. European Journal of Sustainable Development 11: 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishu, Sebawit G., and Andrea M. Headley. 2020. Equal employment opportunity: Women bureaucrats in male-dominated professions. Public Administration Review 80: 1063–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Gonzalez-Tejero, Cristina, and Enrique Cano-Marin. 2023. Empowerment of women’s entrepreneurship in family business through Twitter. Journal of Family Business Management 13: 607–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston Consulting Group. 2018. Why Women-Owned Startups Are a Better Bet. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/why-women-owned-startups-are-better-bet (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Botti, Simona, Sheena S. Iyengar, and Ann L. McGill. 2023. Choice freedom. Journal of Consumer Psychology 33: 143–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozoğlu Batı, Gülgönül, and İsmail Hakkı Armutlulu. 2020. Work and family conflict analysis of female entrepreneurs in Turkey and classification with rough set theory. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley-Cole, Kim, Pam Denicolo, and Max Daniels. 2023. It’s the Way I Tell Them. A Personal Construct Psychology Method for Analysing Narratives. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 36: 467–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Patrice. 2022. Building Gender-Transformative Innovation Ecosystems Supporting Women’s Entrepreneurship. Grupo de Expertos y Expertas CSW-67: Innovación y cambio tecnológico, y educación en la era digital para lograr la igualdad de género y el empoderamiento de todas las mujeres y niñas. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/EP.4_Patrice%20Braun.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Brush, Candida G., Patricia G. Greene, and Friederike Welter. 2020. The Diana Project: A Legacy for Research on Gender in Entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 12: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiarto, Dimas S., Muhammad A. Prabowo, and Nurul B. Azman. 2023. Evaluating the Important Role of Women in Maintaining the Sustainability of SMEs. Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy 11: 180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, Amanda, Ulrike Guelich, Tatiana S. Manolova, and Leon Schjoedt. 2022. Women’s Entrepreneurship and Culture: Gender Role Expectations and Identities, Societal Culture, and the Entrepreneurial Environment. Small Business Economics 58: 985–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Borui, Yong Xiang, Longxiang Gao, He Zhang, Yunfeng Li, and Jianxin Li. 2022. Temporal knowledge graph completion: A survey. arXiv arXiv:2201.08236. [Google Scholar]

- Chancel, Lucas, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, eds. 2022. World Inequality Report 2022. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Ipshita, Dean A. Shepherd, and Joakim Wincent. 2022. Women’s Entrepreneurship and Well-Being at the Base of the Pyramid. Journal of Business Venturing 37: 106222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chereau, Pierre, and Pierre-Xavier Meschi. 2022. Deliberate Practice of Entrepreneurial Learning and Self-Efficacy: The Moderating Effect of Entrepreneurial Parental Environment as Role Modeling. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 29: 461–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Alberto, and Ivan Velez. 2020. Business Training for Women Entrepreneurs in the Kyrgyz Republic: Evidence from a Randomised Controlled Trial. Journal of Development Effectiveness 12: 151–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, Panagiotis A. 2023. How to Use Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research. Journal of Qualitative Research in Tourism 13: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Marilyn. 2020. Women Leaders in the Workplace: Perceptions of Career Barriers, Facilitators and Change. Irish Educational Studies 39: 233–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, Thomas M. 2022. Designing Public Policy to Support Entrepreneurial Activity within the Disabled Community in Ireland. In Research Handbook on Disability and Entrepreneurship. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 131–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costin, Yvonne, Jackie Igoe, Ann Flynn, Naomi Birdthistle, and Briga Hynes. 2021. Human Capabilities and Firm Growth: An Investigation of Women-Owned Established Micro and Small Firms in Ireland. Small Enterprise Research 28: 134–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crummy, Aisling, and Dympna Devine. 2023. ‘I’m Treading Water Here for My Generation’: Gendered and Generational Perspectives on Informal Knowledge Transmissions in Irish Coastal Communities. In Valuing the Past, Sustaining the Future? Exploring Coastal Societies, Childhood(s) and Local Knowledge in Times of Global Transition. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukier, Wendy, and Zahra Hassannezhad Chavoushi. 2020. Facilitating Women Entrepreneurship in Canada: The Case of WEKH. Gender in Management: An International Journal 35: 303–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daradkeh, Muath. 2023. Navigating the Complexity of Entrepreneurial Ethics: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 15: 11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Beauvoir, Simone. 2023. The Second Sex. In Social Theory Re-Wired. London: Routledge, pp. 346–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dewitt, Sarah, Vahid Jafari-Sadeghi, Anand Sukumar, Ramesh Aruvanahalli Nagaraju, Roya Sadraei, and Fang Li. 2022. Family Dynamics and Relationships in Women Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Study. Journal of Family Business Management 13: 626–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, Rachel. 2021. Investigating Gender Inequality and Entrepreneurship Within the Irish Hair and Beauty Sector. Ph.D. thesis, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Dublin City Council. 2023. Census Mapping: Dublin City Council. Central Statistics Office. September 21. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/csolatestnews/pressreleases/2023pressreleases/pressstatementcensus2022csolaunchesinteractivemapforcensus2022smallareas/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Ely, Robin J., and David A. Thomas. 2020. Getting serious about diversity. Harvard Business Review 98: 114–22. [Google Scholar]

- Enterprise Ireland. 2023. €27 Million Invested in Start-Ups in 2022. Available online: https://www.enterprise-ireland.com/en/News/PressReleases/2023-Press-Releases/%E2%82%AC27-Million-Invested-in-Start-Ups-in-2022.html (accessed on 28 April 2023).

- European Commission. 2019. 2019 SBA Fact Sheet, Ireland. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/38662/attachments/15/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- European Commission. (n.d.) Gender Equality. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/gender-equality_en (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Fackelmann, Stephanie, and Alessandra De Concini. 2020. Funding Women Entrepreneurs: How to Empower Growth. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Faugoo, Dharmendra, and Andrew Ikenna Onaga. 2022. Establishing a Resilient, Economically Prosperous and Inclusive World by Overcoming the Gender Digital Divide in the New Normal. In Responsible Management of Shifts in Work Modes–Values for a Post-Pandemic Future. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 1, pp. 115–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Diana P., Michele K. Ryan, and Christopher T. Begeny. 2023. Gender expectations, socioeconomic inequalities and definitions of career success: A qualitative study with university students. PLoS ONE 18: e0281967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrín, Mónica. 2023. Self-employed women in Europe: Lack of opportunity or forced by necessity? Work, Employment & Society 37: 625–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Domecq, Catalina, Adeline De Jong, and Allan M. Williams. 2020. Gender, tourism & entrepreneurship: A critical review. Annals of Tourism Research 84: 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Tobias, and Sim B. Sitkin. 2023. Leadership styles: A comprehensive assessment and way forward. Academy of Management Annals 17: 331–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, Eóin. 2021. Debt, guilt and form in (post-) Celtic Tiger Ireland. Textual Practice 35: 829–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldy, Erica Gabriel, and Sonia M. Ospina. 2023. ‘Contestation, negotiation, and resolution’: The relationship between power and collective leadership. International Journal of Management Reviews 25: 546–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, Sabrina, Jia Wu, Fabian Jintae Froese, and Zhao Xue Chan. 2022. Women entrepreneurship in Asia: A critical review and future directions. Asian Business & Management 21: 343–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Robin, and Kristina Svels. 2022. Women’s Empowerment in small-scale fisheries: The impact of fisheries local action groups. Marine Policy 136: 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Jing, and Ritesh Chugh. 2023. Chapter 12: Conducting qualitative research in education. In How to Conduct Qualitative Research in Social Science. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 204. [Google Scholar]

- Garavan, Thomas N., Sinead Heneghan, Fergal O’Brien, Claire Gubbins, Yanqing Lai, Ronan Carbery, James Duggan, Ronnie Lannon, Maura Sheehan, and Kirsteen Grant. 2020. L&D professionals in organisations: Much ambition, unfilled promise. European Journal of Training and Development 44: 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Giambartolomei, Giulia, Francesca Forno, and Colin Sage. 2021. How food policies emerge: The pivotal role of policy entrepreneurs as brokers and bridges of people and ideas. Food Policy 103: 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliga, Georgiana, and Natasha Evers. 2023. Marketing capability development through networking–An entrepreneurial marketing perspective. Journal of Business Research 156: 113472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2021/2022. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021/22 Women’s Entrepreneurship Report: From Crisis to Opportunity. London: GEM. [Google Scholar]

- Gompers, Paul, Vladimir Mukharlyamov, and Yuhai Xuan. 2020. Gender effects in venture capital investing. The Review of Financial Studies 34: 5331–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, Marcus. 2012. Learning Organizations: Turning Knowledge into Actions. New York: Business Expert Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, Marcus. 2013. Leadership styles: The power to influence others. International Journal of Business and Social Science 4: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves, Marcus. 2015a. Challenges of transforming bottom of the pyramid markets. Financial Nigeria Journal 7: 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves, Marcus. 2015b. Women are Africa’s largest untapped leverage. Financial Nigeria Journal 7: 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves, Marcus, and Esteban De La Vega Ahumada. 2025. A Bibliometric Analysis of Women Entrepreneurship: Current Trends and Challenges. Merits 5: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, Marcus, and Karol Gil Vasquez. 2024. ‘Leadership and entrepreneurial choices: Understanding the motivational dynamics of women entrepreneurs in Mexico’. International Journal of Export Marketing 6: 31–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, Marcus, Nolla Haidar, and Elif Celik. 2024. Navigating Challenges and Opportunities: A Qualitative Exploration of Women’s Entrepreneurship in Lebanon. In Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Technology: A Holistic Analysis of Growth Factors. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, Marcus, Sadaf Sartipi, and Gahazale Asadi Damavandi. 2025a. Leadership and Entrepreneurial Choices: Understanding the Motivational Dynamics of Women Entrepreneurs in Iran. Merits 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, Marcus, Suela Papagelis, and Daphne Nicolitsas. 2025b. Drivers for Women Entrepreneurship in Greece: A Case Analysis of Early-Stage Companies. Businesses 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, Aji S., and Annisa Cahayani. 2022. Do Demographic Variables Make a Difference in Entrepreneurial Leadership Style? Case Study Amongst Micro and Small in Creative Economy Entrepreneurs in Jakarta, Indonesia. International Journal of Asian Business and Information Management 13: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, Nur A., Veland Ramadani, Gati Anggadwita, Gita S. Maulida, Riko Zuferi, and Alain Maalaoui. 2023. Gender stereotype perception, perceived social support and self-efficacy in increasing women’s entrepreneurial intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 29: 1290–313. [Google Scholar]

- Hamouda, Amira, Kate Johnston, and Rachel Nevins. 2022. Chapter 19: Generation Y females in Ireland: An insight into this new entrepreneurial potential for value creation. In Research Handbook of Women’s Entrepreneurship and Value Creation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Chen, Li Zhang, Jian Liu, and Peng Zhang. 2023. Mediating role of teamwork in the influence of team role on team performance. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 16: 1057–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Audrey F. 2021. Irish Women in Business, 1850–1922: Navigating the Credit Economy. Ph.D. dissertation, Discipline of History, Trinity College Dublin, School of Histories & Humanities, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Shariatul H., Jehona Zeqiri, Veland Ramadani, Teoh Sian Zhen, Nurul H. N. Azman, and Ismi Mahmud. 2020. Individual factors, facilitating conditions and career success: Insights from Malaysian women entrepreneurs. Journal of Enterprising Culture 28: 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausberg, Johann P., and Sebastian Korreck. 2020. Business incubators and accelerators: A co-citation analysis-based, systematic literature review. Journal of Technology Transfer 40: 151–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Rachel, Arielle Bernhardt, Girija Borker, Anne Fitzpatrick, Anthony Keats, Madeline McKelway, Andreas Menzel, Teresa Molina, and Garima Sharma. 2024. Female labour force participation. VoxDevLit 11: 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Colette, and Kate V. Lewis. 2023. The art of dramatic construction: Enhancing the context dimension in women’s entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Research 155: 113440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Colette, Susan Coleman, Barbara Orser, and Lene Foss. 2022. Women’s entrepreneurship policy and access to financial capital in different countries: An institutional perspective. Entrepreneurship Research Journal 12: 227–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebl, Martin R. 2021. Sample selection in systematic literature reviews of management research. Organizational Research Methods 26: 229–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbins, Jennifer, Ellen Kristiansen, and Elisabeth Carlström. 2023. Women, leadership, and change–navigating between contradictory cultures. NORA Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 31: 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkatukia, Päivi, Mari Peltola, Tuula Aho, and Riikka Saukkonen. 2022. Between agency and uncertainty–Young women and men constructing citizenship through stories of sexual harassment. Journal of Social Issues 79: 1389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, AAfreen, Chee S. L. Tan, and Venkatesh Venugopal. 2020. How do women entrepreneurs strategize growth? An investigation using the social feminist theory lens. Journal of Small Business Management 58: 259–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, Hurtado, and Nery Karina. 2023. The Inherent Challenges in Creating a New Business in Ireland: The Experiences of Women Entrepreneurs Across the Last Five Years. Ph.D. dissertation, National College of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Hytti, Ulla, Päivi Karhunen, and M. Radu-Lefebvre. 2024. Entrepreneurial masculinity: A fatherhood perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 48: 246–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, Paul A., Kehinde Odunukan, Mahmudur Rahman, Dennis G. Rugara, and Charles Ochinanwata. 2020. How entrepreneurship ecosystem influences the development of frugal innovation and informal entrepreneurship. Thunderbird International Business Review 62: 475–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince-Yenilmez, Meltem. 2021. Women Entrepreneurship for Bridging Economic Gaps. In Engines of Economic Prosperity: Creating Innova-tion and Economic Opportunities Through Entrepreneurship. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 323–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, Claire, Adefolake H. Adenuga, Andrew Ashfield, and Claire Mullan. 2021. Understanding the drivers and motivations of farm diversification: Evidence from Northern Ireland using a mixed methods approach. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 22: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Sarah. 2021. Leaders Perceived Team Talent Development Capabilities: The Impact of Self-Efficacy, Role Clarity, and Role Overload. Master’s dissertation, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Donna K., and Sneha R. Patel. 2021. Role Demands and Constraints in Women Entrepreneurship: A Study of Ireland’s Business Landscape. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 18: 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Karen, Ekoua J. Danho, Emily Yarrow, Robert Cameron, Zoe Dann, Carol Ekinsmyth, Georgiana Busoi, and Amy Doyle. 2023. Governance and public policies: Support for women entrepreneurs in France and England? International Review of Administrative Sciences 89: 1097–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Carolyn, Simone Volet, and Daniela Pino-Pasternak. 2021. Observational research in face-to-face small groupwork: Capturing affect as socio-dynamic interpersonal phenomena. Small Group Research 52: 341–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. Lucero. 2023. Gender, Religion, and Employment: How LDS Working Women Navigate Familial Conflict Concerning Their Paid Work. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy 35: 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabadse, Nada, M. Karatas-Ozkan, N. Theodorakopoulos, Claire McGowan, and Katerina Nicolopoulou. 2020. Business incubator managers’ perceptions of their role and performance success: Role demands, constraints, and choices. European Management Review 17: 485–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamberidou, Irene. 2020. Distinguished women entrepreneurs in the digital economy and the multitasking whirlpool. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 9: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappal, Jasmeet M., and Shikha Rastogi. 2020. Investment behaviour of women entrepreneurs. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 12: 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karneli, Ozlem. 2023. The Role of Adhocratic Leadership in Facing the Changing Business Environment. Journal of Contemporary Administration and Management 1: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, C. 2020. Motivating factors for women to become agripreneurs. Madras Agricultural Journal 107: 333–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayanan, Catherine M. 2022. A critique of innovation districts: Entrepreneurial living and the burden of shouldering urban development. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 54: 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Grainne, and Maura McAdam. 2023. Women entrepreneurs negotiating identities in liminal digital spaces. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 47: 1942–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Naila. 2020. Critical Review of Sampling Techniques in the Research Process in the World. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3572336 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Khurana, Isha, Dutta K. Dutta, and Amit S. Ghura. 2022. SMEs and digital transformation during a crisis: The emergence of resilience as a second-order dynamic capability in an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Journal of Business Research 150: 623–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbu, Albert N., Adeline de Jong, I. Adam, M. A. Ribeiro, E. Afenyo-Agbe, O. Adeola, and C. Figueroa-Domecq. 2021. Recontextualising gender in entrepreneurial leadership. Annals of Tourism Research 88: 103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoppers, Annelies, Danielle de Haan, Lucie Norman, and Nicole LaVoi. 2022. Elite women coaches negotiating and resisting power in football. Gender, Work & Organization 29: 880–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Lea, Patricia Gorris, Cristina Prell, and Claudia Pahl-Wostl. 2023. Communication, trust and leadership in co-managing biodiversity: A network analysis to understand social drivers shaping a common narrative. Journal of Environmental Management 336: 117551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, Jane, and Eva van Lieshout. 2023. Women Entrepreneurs and International Trade. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/joining-forces-for-gender-equality_67d48024-en.html (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Kruse, Phillip, Daniel Wach, and Jürgen Wegge. 2021. What motivates social entrepreneurs? A meta-analysis on predictors of the intention to found a social enterprise. Journal of Small Business Management 59: 477–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, Daniel. 2023. Thinking Qualitatively: Paradigms and Design in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Research and Evaluation in Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19: 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Cai, S. F. Ashraf, F. Shahzad, I. Bashir, M. Murad, N. Syed, and M. Riaz. 2020. Influence of knowledge management practices on entrepreneurial and organizational performance: A mediated-moderation model. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 577106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Wayne M. 2025. What is qualitative research? An overview and guidelines. Australasian Marketing Journal 33: 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindvert, Monica, M. Breivik-Meyer, Gry A. Alsos, Dag Balkmar, Tea Bedenik, Ann-Charlott Callerstig, Debirah Delaney, Sigal Heilbrunn, Elisabet Ljunggren, Maura McAdam, and et al. 2023. A Cross-Cultural Examination of Investor Behaviour: The Influence of Gendered Understandings. Bodø: Nord University. [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa, Anil Kumar, and L. L. Rodrigues. 2023. Synthesis of necessity and opportunity motivation factors in women entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Sage Open 13: 21582440231159294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Brooke Fisher, Dan Shi, Jiyoon R. Lim, Kabir Islam, Autumn L. Edwards, and Matthew Seeger. 2022. When crises hit home: How US higher education leaders navigate values during uncertain times. Journal of Business Ethics 179: 353–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanagamage, Nadeesha, Christine Glavas, Tharaka Kodagoda, and Laura Schuster. 2023. Psychological capital and emotions on “surviving” or “thriving” during uncertainty: Evidence from women entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management 62: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llados-Masllorens, Jordi, and Jordi Ruiz-Dotras. 2021. Are women’s entrepreneurial intentions and motivations influenced by financial skills? International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 14: 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, Inessa, Boris Nikolaev, and Chirananda Dhakal. 2024. The well-being of women entrepreneurs: The role of gender inequality and gender roles. Small Business Economics 62: 325–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, Salma, Philip Eke, Tendai Mpofu, and Silke Machold. 2022. Women in Business Leadership in the Midlands. Wolverhampton: University of Wolverhampton. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Muhammad Fahad, Muhammad Ghaus Khwaja, Hafsa Hanif, and Saima Mahmood. 2023. The missing link in knowledge sharing: The crucial role of supervisor support-moderated mediated model. Leadership & Organization Development Journal 44: 771–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, Malin, Barbara Burkhard, Christina Sirén, Dean Shepherd, and Joakim Wincent. 2023. A meta-analysis of the impact of entrepreneurs’ gender on their access to bank finance. Journal of Business Ethics 192: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, Regina, and Christoph H. Antoni. 2022. Work Overload and Self-Endangering Work Behavior. Zeitschrift für Arbeits-und Organisa-tionspsychologie A&O 67. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Ashley E., and Michael L. Slepian. 2021. The primacy of gender: Gendered cognition underlies the big two dimensions of social cognition. Perspectives on Psychological Science 16: 1143–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseda, Amaia, Txomin Iturralde, Sharon Cooper, and Gonzalo Aparicio. 2022. Mapping women’s involvement in family firms: A review based on bibliographic coupling analysis. International Journal of Management Reviews 24: 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, Maura. 2022. Women’s Entrepreneurship. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, Claire, Lorna Bradley-McCauley, and Siobhán Stephens. 2022. Exploring entrepreneurs’ business-related social media typologies: A latent class analysis approach. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 28: 1245–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, Jason M. 2023. Stop the Burnout: Enhancing Support Practices for Principals. Ph.D. dissertation, Western University, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Matthew B., A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2020. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mmbaga, Noel A., Blake D. Mathias, David W. Williams, and Melissa S. Cardon. 2020. A review of and future agenda for research on identity in entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing 35: 106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, D., and H. Mohajan. 2022. Straussian Grounded Theory: An Evolved Variant in Qualitative Research. Studies in Social Science & Humanities 2: 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajan, Haradhan. 2022. An Overview on the Feminism and Its Categories. Research and Advances in Education 1: 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, Silvia. 2024. SDG 5. Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. In Identity, Territories, and Sustainability: Challenges and Opportunities for Achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Monaro, Silvia, Jenny Gullick, and Susan West. 2022. Qualitative data analysis for health research: A step-by-step example of phenomenological interpretation. The Qualitative Report 27: 1040–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulawarman, Lisa, Hamzah Hasan, and Siti M. Sharif. 2020. Motivations And Challenges of Women Entrepreneurs: The Indonesian Mum-preneur Perspective. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine 7: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyana, Agus, Mia Ridaryanthi, Siti Faridah, Fatma H. Umarella, and Eko Endri. 2022. Socio-emotional leadership style as implementation of situational leadership communication in the face of radical change. Management 11: 150–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupangwa, Talent. 2023. The feminisation of poverty: A study of Ndau women of Muchadziya village in Chimanimani Zimbabwe. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 79: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musenze, Innocent A., and Tom S. Mayende. 2023. Ethical leadership (EL) and innovative work behavior (IWB) in public universities: Examining the moderating role of perceived organizational support (POS). Management Research Review 46: 682–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, Md Nu N., Zhen Liu, and Nazmul Hasan. 2023. Investigating the effects of leaders’ stewardship behavior on radical innovation: A mediating role of knowledge management dynamic capability and moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Management Research Review 46: 173–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nate, Sanda, Vlad Grecu, Andriy Stavytskyy, and Ganna Kharlamova. 2022. Fostering entrepreneurial ecosystems through the stimulation and mentorship of new entrepreneurs. Sustainability 14: 7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, Joanne. 2021. Iterative categorisation (IC) (part 2): Interpreting qualitative data. Addiction 116: 668–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negra, Diane, and Áine P. McIntyre. 2020. Ireland Inc.: The corporatization of affective life in post-Celtic Tiger Ireland. International Journal of Cultural Studies 23: 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, Laura. 2020. Beyond ‘get big or get out’: Women farmers’ responses to the cost-price squeeze of Australian agriculture. Journal of Rural Studies 79: 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, Sobia, Fauziah M. Isa, and Amna Shafiq. 2022. Women’s entrepreneurial success models: A review of the literature. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 18: 137–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbø, Ingebjørg. 2022. Female entrepreneurs and path-dependency in rural tourism. Journal of Rural Studies 96: 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyanga, Tinashe, and Augustine Chindanya. 2021. From Risk Aversion to Risk Loving: Strategies to Increase Participation of Women Entrepreneurs in Masvingo Urban, Zimbabwe. Ushus Journal of Business Management 20: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nziku, Dativa M., and Claude Bikorimana. 2023. Forcibly displaced refugee women entrepreneurs in Glasgow-Scotland. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 18: 820–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obilor, Emmanuel I. 2023. Convenience and Purposive Sampling Techniques: Are they the Same? International Journal of Innovative Social & Science Education Research 11: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Eileen, and Thomas M. Cooney. 2024. Enhancing inclusive entrepreneurial activity through community engagement led by higher education institutions. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 19: 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Pat. 2020. Creating Gendered Change in Irish higher education: Is managerial leadership up to the task? Irish Educational Studies 39: 139–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, Paul, Mary Leger, Colm O’Gorman, and Eoin Clinton. 2024. Necessity entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals 18: 44–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ó Gráda, Cormace, and Kevin H. O’Rourke. 2022. The Irish economy during the century after partition. The Economic History Review 75: 336–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundana, Omotayo M., Alfreda Simba, Leo Paul Dana, and Eric Liguori. 2021. Women entrepreneurship in developing economies: A gender-based growth model. Journal of Small Business Management 59: S42–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunjemilusi, Kehinde D., Kathleen Johnston, and Barry Boyd. 2021. An exploration and critique of the entrepreneurship financial ecosystem facing female entrepreneurs in Northern Ireland. Paper presented at International Conference on Gender Research, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, June 21–22; pp. 365–69. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, Aoife, and Brendan O’Gorman. 2020. Considerations for scaling a social enterprise: Key factors and elements. The Irish Journal of Management 42: 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyusheva, Irina, and Nicola Meyer. 2020. The features of women entrepreneurship development in Ireland: An analytical survey. Polish Journal of Management Studies 21: 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, Clare, Laura Walsh, and Ziene Mottiar. 2023. Considerations for scaling a social enterprise: Key factors and elements. The Irish Journal of Management 42: 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkazanc-Pan, Banu, and Susan Coleman Muntean. 2021. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: A Gender Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Meléndez, Antonio, Ana Maria Ciruela-Lorenzo, A. R. Del-Aguila-Obra, and J. J. Plaza-Angulo. 2022. Understanding the entrepreneurial resilience of indigenous women entrepreneurs as a dynamic process. The case of Quechuas in Bolivia. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 34: 852–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliszkiewicz, Joanna, Jerzy Gołuchowski, and Ewa Skarzyńska. 2023. 6 The role of trust in leadership. In Communication, Leadership and Trust in Organizations. Oxford: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Prabawanti, Budi Eko, and Muhammad Syahril Rusli. 2022. The role of social support for women entrepreneurs in reducing conflict to increase business performance. Indonesian Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship 8: 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Saima, and Vanessa Ratten. 2020. A systematic literature review on women entrepreneurship in emerging economies while reflecting specifically on SAARC countries. In Entrepreneurship and Organizational Change: Managing Innovation and Creative Capabilities. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 37–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, Vanessa. 2023. Entrepreneurship: Definitions, opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 42: 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redín, Domingo M., Michael Meyer, and Arménio Rego. 2023. Positive leadership action framework: Simply doing good and doing well. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 977750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjith, Vino, Raji Yesodharan, Judith A. Noronha, Emily Ladd, and Anice George. 2021. Qualitative methods in health care research. International Journal of Preventive Medicine 12: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshi, Imtiyaz Ahmad, and Thallam Sudha. 2023. Economic Empowerment of Women: A Review of Current Research. International Journal of Educational Review, Law and Social Sciences 3: 601–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rigtering, Jeroen C., and Marion A. Behrens. 2021. The effect of corporate—Start-up collaborations on corporate entrepreneurship. Review of Managerial Science 15: 2427–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Jenny K., Erika A. Guenther, and Rifat Faiz. 2023. Feminist futures in gender-in-leadership research: Self-reflexive approximations to intersectional situatedness. Gender in Management: An International Journal 38: 230–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Martínez, Rocio, Karin Kuschel, and Inmaculada Pastor. 2021. A contextual approach to women’s entrepreneurship in Latin America: Impacting research and public policy. International Journal of Globalisation and Small Business 12: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, Saroj K., and Subhadeep S. Goswami. 2023. A comprehensive review of multiple criteria decision-making (MCDM) Methods: Advance-ments, applications, and future directions. Decision Making Advances 1: 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluja, Om B., P. Singh, and Himanshu Kumar. 2023. Barriers and interventions on the way to empower women through financial inclusion: A 2 decades systematic review (2000–2020). Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, Elisa, Franziska M. Belz, and Sophie Bacq. 2023. Informal entrepreneurship: An integrative review and future research agenda. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 47: 265–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samdanis, Manuel, and Mustafa Özbilgin. 2020. The duality of an atypical leader in diversity management: The legitimization and delegitimi-zation of diversity beliefs in organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews 22: 101–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaean, Fahad, and Khalid Ali. 2020. The mediation effect of TQM practices on the relationship between entrepreneurial leadership and organizational performance of SMEs in Kuwait. Management Science Letters 10: 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiuma, Giovanni, Elisabetta Schettini, Francesco Santarsiero, and Daniela Carlucci. 2022. The transformative leadership compass: Six competencies for digital transformation entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 28: 1273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra-Pons, Paula, Sofia Belarbi-Munoz, David Garzon, and Amparo Mas-Tur. 2022. Cross-country differences in drivers of female necessity entrepreneurship. Service Business 16: 971–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setini, Made, Ni Nyoman Kerti Yasa, I Wayan Gede Supartha, I Gusti Ayu Ketut Giantari, and Ismi Rajiani. 2020. The passway of women entrepreneurship: Starting from social capital with open innovation, through to knowledge sharing and innovative performance. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 6: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Wendy, and Dana L. Joseph. 2021. Gender and leadership: A criterion-focused review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review 31: 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirish, Anjali, Shirish C. Srivastava, and Natasha Panteli. 2023. Management and sustenance of digital transformations in the Irish microbusiness sector: Examining the key role of microbusiness owner-manager. European Journal of Information Systems 32: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoma, Chandan Das. 2019. Financing women entrepreneurs in cottage, micro, small, and medium enterprises: Evidence from the financial sector in Bangladesh 2010–2018. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 6: 397–416. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Daniel M., R. Joseph Rosario, Ivonne A. Hernandez, and Mesmin Destin. 2023. The ongoing development of strength-based approaches to people who hold systemically marginalized identities. Personality and Social Psychology Review 27: 255–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagulova, Gulnur, and Marcus Goncalves. 2023. Drivers for women entrepreneurship in Central Asia: A case analysis of Kazakhstani enterprises. Journal of Transnational Management 28: 249–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Matthew. 2024. Beyond the Norm: Dynamic Systems Theory and Adaptability in Maneuvering Complex Organizational Conflicts. Master’s thesis, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Wendy K., and & Miguel Pina E. Cunha. 2020. A paradoxical approach to hybridity: Integrating dynamic equilibrium and disequilibrium perspectives. In Organizational Hybridity: Perspectives, Processes, Promises. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Solanki, Neha, Ritesh Yadav, and Mahendra Yadav. 2023. Social capital and social entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Technology, Management and Business Evolving Perspectives 31: 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, Simon, Christopher McLaughlin, Leah Ryan, Manuel Catena, and Aisling Bonner. 2022. Entrepreneurial ecosystems: Multiple domains, dimensions and relationships. Journal of Business Venturing Insights 18: e00344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Rosemary. 1982. A model for understanding managerial jobs and behaviour. The Academy of Management Review 7: 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, Susan, Ines Rossano-Rivero, Stefano Rossano, Susan Davis, Ingrid Wakkee, Susan Stoker, and Ingrid Wakkee. 2021. Towards an understanding of inclusive ecosystems. In RENT XXXV. Turku: Inclusive Entrepreneurship. [Google Scholar]

- Sudha, Tharika, and Imtiyaz Ahmad Reshi. 2023. Unleashing The Power: Empowering Women for A Stronger Economy. International Journal of Educational Review, Law and Social Sciences 3: 826–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tashpulatova, Maftuna M. 2021. The Perspectives of Doing Business for Women Entrepreneurs in Uzbekistan. Мирoвая наука 4: 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, Maria Beatriz M., Letícia Lopes D. C. Galvão, Claudia Mota-Santos, and Lúcia J. O. Carmo. 2021. Women and work: Film analysis of Most Beautiful Thing. REGE Revista de Gestão 28: 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, Iván, Carolina Albornoz, and Karla Schneider. 2020. Learning analytics to explore dropout in online entrepreneurship education. Psychology 11: 268–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Trauth, Eileen, and Regina Connolly. 2021. Investigating the nature of change in factors affecting gender equity in the IT sector: A longitudinal study of women in Ireland. MIS Quarterly 45: 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubfal, Diego. 2024. What Works in Supporting Women-Led Businesses? Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/295973 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Ueno, Keisuke, Raul Dominguez, Sarah Bastow, and Jonathan V. D’amours. 2023. LGBTQ Identities and Career Plan Changes in Young Adulthood: Implications for Occupational Segregation and Disparities. Socius 9: 23780231231215682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. n.d. Sustainable Development Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Usman, Fatima O., Aisha J. Kess-Momoh, Chika V. Ibeh, Ayodele E. Elufioye, Valentina I. Ilojianya, and Olufunmilayo P. Oyeyemi. 2024. Entrepreneurial innovations and trends: A global review: Examining emerging trends, challenges, and opportunities in the field of entrepreneurship, with a focus on how technology and globalization are shaping new business ventures. International Journal of Science and Research Archive 11: 552–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhan, Jyotsna, Sunita Bohra, Abdullah Abdullah, K. Thennarasu, and S. K. Jagannathan. 2020. Push or pull motivation? A study of migrant women entrepreneurs in UAE. International Journal of Family Business and Regional Development 1: 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vārpiņa, Zane, Maija Krūmiņa, Kristof Fredheim, and A. Paalzow. 2023. Back for business: The link between foreign experience and entre-preneurship in Latvia. International Migration 61: 269–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseca, David, Javier Navío-Marco, and Raquel Gimeno. 2020. Money for female entrepreneurs does not grow on trees: Start-ups’ financing implications in times of COVID-19. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 13: 698–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vize, Richard. 2022. Ockenden report exposes failures in leadership, teamwork, and listening to patients. BMJ 376: o860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuchkovski, Dragan, Miha Zalaznik, Maciej Mitręga, and Gregor Pfajfar. 2023. A look at the future of work: The digital transformation of teams from conventional to virtual. Journal of Business Research 163: 113912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafeq, Manal, Omar Al Serhan, K. Catherine Gleason, S. W. S. B. Dasanayaka, Rania Houjeir, and & M. Al Sakka. 2019. Marketing management and optimism of Afghan female entrepreneurs. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 11: 436–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yafang, Yuanyuan Li, Jun Wu, Lian Ling, and Dongmei Long. 2022. Does digitalization sufficiently empower female entrepreneurs? Evidence from their online gender identities and crowdfunding performance. Small Business Economics 61: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Justin W., Theodore A. Khoury, and Michael A. Hitt. 2020. The influence of formal and informal institutional voids on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 44: 504–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, David, and David Dokter. 2023. The Researcher’s Toolkit: The Complete Guide to Practitioner Research. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Brittany M., Brenda Anderson Wadley, Lamesha C. Brown, and Qua’Aisa Williams. 2023a. “It’s a matter of not knowing”: Examining Black first-gen women administrators’ career socialization and preparation. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 18: 313–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Mark, Mahdieh Ghorbani, and Arturs Kalnins. 2023b. Moving to the big city: Temporal, demographic, and geographic Influences on the perceptions of gender-related business acumen among male and female migrant entrepreneurs in China. Academy of Management Discoveries 9: 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Shih-Ye, and Shu-Min Wang. 2023. Exploring the effects of gender grouping and the cognitive processing patterns of a Facebook-based online collaborative learning activity. Interactive Learning Environments 31: 576–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xheneti, Mirela, Sushma Tiwari Karki, and Amanda Madden. 2021. Negotiating business and family demands within a patriarchal society–the case of women entrepreneurs in the Nepalese context. In Understanding Women’s Entrepreneurship in a Gendered Context. London: Routledge, pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylisirniö, Katja. 2023. Emotional Intelligence Within Communication in Strategy Implementation, A Management. Master’s dissertation, University of Turku, Turku, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Sanghoon, Sung-Lin Kim, and Seonghee Yun. 2023. Supervisor knowledge sharing and creative behavior: The roles of employees’ self-efficacy and work–family conflict. Journal of Management & Organization 30: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoong, May, and Michelle Yoong. 2020. Neoliberal feminism and media discourses of employed motherhood. In Professional Discourses, Gender and Identity in Women’s Media. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Yimei, and Jing Lu. 2022. International students’ motivation to study abroad: An empirical study based on expectancy-value theory and self-determination theory. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 841122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, Azmat, Waqar Raza, Khalid Hayat, Junaid Raheel, and Nadia S. Kakakhel. 2021. The role of Informal networks in enhancing the performance of Women Entrepreneurs-A case study of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Indian Journal of Economics and Business 20: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhailaubayeva, Aigerim. 2021. The Effect of Organizational Culture to Female Career in Kazakhstan. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/f97b4333736389cb1e4f5d6a0bcbcf32/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2026366&diss=y (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Zhang, Guojun, Zhiguo Jia, and Shuwen Yan. 2022. Does gender matter? The relationship comparison of strategic leadership on organizational am-bidextrous behavior between male and female CEOs. Sustainability 14: 8559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Lin. 2020. An institutional approach to gender diversity and firm performance. Organization Science 31: 439–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żur, Anna. 2021. Entrepreneurial identity and social-business tensions–the experience of social entrepreneurs. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 12: 438–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Identifier | Age | Education | Leadership Role | Experience Yrs. | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewee 1 | 45 | University | Owner | 5 | Recruitment |

| Interviewee 2 | 30s | University | Owner | 3 | Philanthropy/ Partnerships |

| Interviewee 3 | 40s | University | Owner | 5 | Bookkeeping |

| Interviewee 4 | 40s | University | Co-Founder | 4 | Healthcare |

| Interviewee 5 | 50 | MBA | Owner | 25 | Business Consulting/ Author |

| Interviewee 6 | 30s | University | Owner | 4 | Children’s Educational Product |

| Interviewee 7 | 40s | University | Owner | 3 | Children’s Educational Product |

| Interviewee 8 | 50s | University | Owner | 10 | Finance |

| Interviewee 9 | 60 | University | CEO | 8 | Solar Energy |

| Interviewee 10 | 30 | MBA | Owner | 5 | Digital Marketing |

| Interviewee 11 | 50s | MBA | Owner | 15 | Cyber Security |

| Interviewee 12 | 50s | University | CEO/Founder | 22 | Digital Meetings/Female Entrepreneurship |

| Interviewee 13 | 30s | University | Self-Employed | 10 | Innovation Events |

| Interviewee 14 | 50s | University | CEO/Founder | 2 | Business Development Tech |

| Items Descriptors | Descriptors |

|---|---|

| Drivers | • Generating value for the business, its stakeholders, and society • Partnerships • Well-being, affluence, and contentment |

| Demands | • Outcomes for the business encompass both monetary and non-monetary aspects • Resilience, adaptability, and inclusion • Self-discovery and self-fulfillment |

| Constraints | • High workload • Inexperience and absence of established cognitive frameworks • Absence of common understanding • Marriage, offspring, familial responsibilities, and business obligations • Direct access to financial resources and programs (complex to understand/apply) • Conventional Irish norms for femininity, family roles, and societal expectations |

| Choice | • Mutual professional enhancement/advancement possibilities • Teamwork • Flexible and adaptive expectations and roles • Career progression or professional development |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goncalves, M.; Trainor, M.; Ursini, A. Exploring Barriers and Enablers for Women Entrepreneurs in Urban Ireland: A Qualitative Study of the Greater Dublin Area. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070412

Goncalves M, Trainor M, Ursini A. Exploring Barriers and Enablers for Women Entrepreneurs in Urban Ireland: A Qualitative Study of the Greater Dublin Area. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(7):412. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070412

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoncalves, Marcus, Megan Trainor, and Andreana Ursini. 2025. "Exploring Barriers and Enablers for Women Entrepreneurs in Urban Ireland: A Qualitative Study of the Greater Dublin Area" Social Sciences 14, no. 7: 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070412

APA StyleGoncalves, M., Trainor, M., & Ursini, A. (2025). Exploring Barriers and Enablers for Women Entrepreneurs in Urban Ireland: A Qualitative Study of the Greater Dublin Area. Social Sciences, 14(7), 412. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070412