1. Introduction

The rate of incarceration in the United States is six to ten times higher than in countries with similar living standards. There are currently more than 7 million Americans who are system-involved. As the rate of incarceration has increased, the risk of parental imprisonment has also dramatically increased. As of 2016, an estimated 1,473,700 minor children had a parent incarcerated in state or federal prison. In 2018, it was estimated that nearly 6 million children in the U.S. were experiencing or had experienced parental incarceration (

Annie E. Casey Foundation 2016). Additionally, the number of children with an imprisoned mother increased by 131% since 1991 (

Maruschak et al. 2021). Significant racial disparities exist, as Black children are seven times more likely to experience an incarcerated parent than White children (

Western 2010). Generations are being lost to the prison system, and as a result, children, families, and communities become more vulnerable, defenseless, and impoverished (

Geiger and Fischer 2005).

Connecticut incarcerates 170 individuals per 100,000 residents, with racial disparities of 9.4 for Black residents and 3.7 for Hispanic residents for every White resident (

The Sentencing Project 2023). In 2023, it is estimated that Connecticut children experience parental arrest more than 62,000 times annually (

CT Children with Incarcerated Parents Initiative 2023). At the end of 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Connecticut had 12,658 incarcerated individuals; following the global pandemic, those numbers dramatically decreased (9487) but have begun to rise again (10,555). It is estimated that more than half of the state prison population are parents (

CT DOC 2025), which means that in 2019, more than 6300 children in the state of Connecticut had an incarcerated parent. If adding system-involved parents (probation, parole, and/or supervised community program), the number increases to 8300 children (

https://portal.ct.gov/DOC accessed on 12 March 2025).

Adverse Childhood Experiences

International human rights advocates have called parental incarceration the greatest threat to child well-being in the United States (

Osborne Association 2017). Parental incarceration is recognized as an “adverse childhood experience” (ACE), and this stressful and traumatic experience is of the same magnitude as abuse, domestic violence, and divorce (

Annie E. Casey Foundation 2016;

Murphey and Cooper 2015;

Rhodes et al. 2023). However, the unique combination of trauma, shame, and stigma distinguishes it from other adverse experiences (

Hairston 2007). The intensity of vulnerability for children of color, especially Black and African American children, is amplified from the experiences of White children ten-fold (

Horton 2022). ACEs are consistently associated with a wide range of adverse outcomes, including increased risk of mental health problems in childhood and adulthood. When compared to children without an incarcerated parent (s), children with an incarcerated parent had increased odds of experiencing other ACEs, increased odds of having mental health problems, and fewer positive childhood experiences (

Rhodes et al. 2023).

Morgan-Mullane (

2018) found that parental incarceration became the source of PTSD symptoms in children, including depression, anger, aggression, self-isolation, and self-injury. This growing body of research highlights the urgent need for inclusive, community-driven approaches to understanding and addressing the impact of parental incarceration. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) and Photovoice offer powerful methodologies that amplify the voices of those directly affected, fostering advocacy and policy change through lived experiences and visual storytelling.

2. Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) and Photovoice

CBPR is a co-learning process between academic and community partners, resource sharing, and capacity building of unique skill sets and resources (

Minkler and Wallerstein 2008). Photovoice, a community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodology, is grounded in democratic ideals and informed by critical consciousness theory, feminist theory, and a community-based approach to documentary photography (

Wang and Burris 1997). This research method involves creating a research participant’s visual representation of their lived experiences on a particular topic. Photovoice research seeks to create a lasting impact on individuals and communities that extends beyond the completion of the study. Photovoice was developed as a research approach to empower marginalized populations (

Wang and Burris 1997) by providing under-resourced communities with a means of self-expression through photography.

The goals of Photovoice are to enable people to (1) record and represent their everyday realities, (2) promote critical dialog and awareness about personal and community strengths and concerns, and (3) offer a platform for presenting people’s lived experiences through their images and language to reach policymakers (

Wang 1999). Photovoice fosters self-advocacy by acknowledging participants’ experiences and facilitating a power-sharing dynamic between participants and facilitators. This engaging and interactive technique may empower and give voice to two overlooked groups: marginalized youths and adults. This approach will create opportunities for participation in mutual aid groups, as well as influence social policy and social change. The process of taking photos and discussing them with others who share this reality empowers individuals, and the power of the visual image acts as a form of communication (

Wang 1999). Through this community-driven process, critical consciousness can raise awareness of innovative methods to reduce barriers to community integration and enhance civic engagement for youths, adults, and their families. It is assumed that by raising critical consciousness, individuals will question the reality of their historical and social situations and thereby effect change (

Freire 2018). Understanding the changing social structures is crucial for grasping oppression and the hegemonic structure of dominant forces in society (

Freire 2018). This research project aimed to combine CBPR with Photovoice to better understand the perspective and experiences of children with incarcerated parents through photography and narratives.

3. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework guiding this study is

Du Bois’ (

[1903] 1994) seminal notion of double consciousness. Conceived initially to capture the psychosocial experience of Black Americans, double consciousness provides a lens for understanding the divided self-perceptions and worldviews that can arise for individuals occupying marginalized social positions and identities.

Du Bois (

[1903] 1994) famously characterized double consciousness as a “twoness” or “double life…two warring ideals in one dark body” (p. 2). As a result of structural inequality, double consciousness forces Black people to not only view themselves from their unique perspective but also to view themselves as they might be perceived by the outside (or White-dominated) world. The internalization of anti-Black sentiments from the outside world shapes the experiences of Black Americans, “looking at oneself through the eyes of others.” This form of “double-vision” requires dexterity in code-switching between two conflicting self-constructions and frames of reference.

As the following study examines the identity experiences of Black youth with lived experience of parental incarceration, double consciousness provides a critical framework for understanding participants’ potential psychosocial dualities in embodying and subscribing to multiple simultaneously existing cultural realities and self-understandings. Building on this framework, Comparative Conflict Theory further contextualizes these identity negotiations by examining how structural inequalities, power dynamics, and systemic conflicts shape the lived experiences of Black youth with incarcerated parents. This perspective deepens the analysis by highlighting the broader socio-political forces that contribute to their marginalization and resilience.

Comparative Conflict Theory (CCT) explains the variations between races in interpretations and perceptions of normative justice. CCT argues that the relationship between race/ethnicity and perceptions of injustice is best characterized in the context of a racial/ethnic divide and gradient, whereby African Americans perceive the most injustice, followed by Hispanics and then Whites (

Shedd and Hagen 2006). Significantly, CCT also suggests that the racial/ethnic gaps in perceived injustice are dynamic and not static, as prior contact with criminal justice can alter the existent gaps between racial and ethnic dyads (African Americans and Hispanics) because racial/ethnic groups are differentially sensitive to prior contact with the criminal justice system (

Shedd and Hagen 2006).

Race is a critical factor in attributing structural barriers to inequality (

Feagin 1975). In the United States, African Americans are more likely than Whites to identify structural racism and discrimination as barriers that negatively impact their opportunities and success (

Bonilla-Silva 2010). African Americans simultaneously believe that both individual-level factors and structural-level factors contribute to persistent racial inequality, resulting in double consciousness. Individuals who remain wedded to individualism rather than structuralism tend to be members of dominant racial and ethnic groups. However, African Americans simultaneously endorse both individualistic and structuralist beliefs, which have been labeled “dual consciousness” (

Bullock and Waugh 2005).

Hagan et al. (

2005) argue that African Americans and Hispanics experience more injustice than Whites because of their relative lack of social, political, economic, and cultural power. Moreover, harmful contact with the criminal justice system has been associated with increased perceptions of injustice (

Hagan et al. 2005). As the proportion of African American students within their school increases, these youth are more impacted by their perceptions of injustices than Hispanic youth. In summary, Comparative Conflict Theory provides a valuable lens for understanding the dynamics of power and inequality affecting youth with incarcerated parents. By examining the intersections of systemic oppression and social identity, this research project aims to illuminate the unique challenges faced by these youths.

The race-specific correlations described in Comparative Conflict Theory mirror, too, how the carceral state is related to the dual consciousness of Black Americans and, specifically, the feelings and concrete observations made by the youth who participated in this study. Their lived experiences describe in practice the cautions and implications cited by Du Bois and later by

Angela Davis (

2003) and, yet more recently, by Michelle Alexander (

Alexander [2010] 2020) in their seminal writing on the American carceral state and are central to an understanding of Abolitionist praxis in social work (

Brock-Petroshius 2022).

4. Methodology

The primary reason for conducting this Photovoice study was to understand how children and youth in Black and/or African American families experienced their fathers being incarcerated. This study does not try to differentiate between oppression and marginalization experienced by the children, youth, and mothers before or after the incarceration. This study was conducted over a six-month period in the spring and summer of 2019 in a large northeastern city. Before commencing this crucial work, the research team obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to engage with children, youth, and mothers. The research team included two co-researchers, community members who lived in the city, and ensured they had an equal voice and say in every step of the research process. Each mother provided consent for the project before the research team interacted with their children. It was essential for the research team that the mothers understood all aspects of the project and its various phases before signing the consent forms. After receiving the mothers’ consent, the research team explained the assent form (written at a third-grade reading level) to be used with each child and youth, providing this explanation in the presence of their mothers. The research team specifically instructed the mothers not to impart their feelings or beliefs about this work onto their children and to allow them to make their own assent decisions.

This Photovoice study followed the typical phases in the methodology: two phases of data collection and a third phase that aimed to present photographs in an exhibition and develop action steps to be shared as phase four. The methodological process included the vital components of any rigorous, credible qualitative study, including transparency, trustworthiness, and transferability (

Padgett 2008). Data collection methods included demographic sheets, focus groups, photographs, and narratives. Each focus group and photo discussion session was audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and inductively coded and organized for analysis using NVivo (version 10). Each of the youth received USD 20 for participating in each focus group of the study, and the research team provided food and beverages to the youth and their mothers. Additionally, focus groups were kept to a maximum of 50–60 min, based on the attention span of the youth at each meeting.

4.1. Sampling Plan

Convenience and purposive sampling strategies were utilized. With the support of two community members who were co-researchers, they engaged with community stakeholders and partners to recruit participants for this study. A co-researcher was CITI-trained and instrumental in accessing the population and implementing the research design. This study recruited participants between the ages of 9 and 17 (as this is a critical developmental stage in identity formation) who identified as Black and/or African American, spoke English, had a father currently incarcerated, and lived in the city where the study would take place. All of the participants had fathers who were incarcerated at the time of the study, except for one male youth. The man the youth identified as his father was actually his uncle, who was also incarcerated. This youth did not know who his biological father was and had never met him; his uncle stepped into that role and filled that family function. Membership in a stigmatized community during these formative years can potentially be harmful to the development of a positive sense of self. The final sample included eleven Black youth, five girls and six boys, aged 9–17, and each of their mothers.

4.2. Data Collection

Data collection occurred over four phases. Phase One included focus groups with children who have incarcerated fathers, helping to define and identify relevant concepts and experiences that would create a focus for the photovoice project. During this first focus group, youth were trained in digital photography with a camera (which they kept for participating in the study) and appropriate ethical photography. All participants received information highlighting the importance of protecting each other’s privacy, refraining from photographing inappropriate or illicit activities and being encouraged not to discuss the contents of each focus group. During Phase Two, youth participants engaged in community photography as a creative outlet to capture pictures that reflected the essence of the identified themes (128 final photos). Phase Three included photo discussion groups with the youth and a separate focus group with the mothers, offering further context to the data being collected. The SHOWeD technique guided the photo discussion in small groups. This Freirean-based critical dialog, often employed in conjunction with Photovoice methodology, involves a series of questions that guide the discussion from a personal level to a social analysis and then to action steps (

Wallerstein and Bernstein 1988). The SHOWeD questions include the following: What do you see here? What’s really happening here? How does this relate to our lives? Why does this situation, concern, or strength exist? What can we do about it? After the small groups, all the youth convened to share and discuss their small group photos and their voted favorites. The larger group then also voted on which photos they believed aligned most with the discussed themes. Phase Four was unable to be implemented, as the project was nearing completion when the COVID-19 pandemic began. Consequently, the final phase, which involved presenting the findings to the community and powerful elites, could not be implemented. When the research team reapproached the participants, too much time had passed for any meaningful implementation of the final phase, as the participants could no longer remember all the pictures or conversations.

4.3. Analysis

Upon completion of the photovoice in Phase Two, data analysis was conducted. Four researchers independently coded for themes and discussed them with their co-researchers from the community for agreement. At the end of this process, there were 12 identified thematic codes, including (1) unfair systems (fear of prison, race, and police brutality); (2) physical space (not livable, emptiness, and abandoned buildings); (3) lack of protection (police, school, and family); (4) interruption (missing link, hold on family); (5) family (connection, role model, and support); (6) community (emptiness, leadership, and engagement); (7) duality (contradictions); (8) redemption; (9) emotional responses; (10) poverty; (11) threat of prison (drinking, addiction, inevitability); and (12) addiction. The next phase involved each researcher reanalyzing the identified codes to synthesize and collapse them. Final codes included interruption of the whole, lack of protection, unfair systems, and duality.

5. Findings

This study used Photovoice to explore the lived experiences of eleven youths with incarcerated parents. The youths identified themes that impacted how they moved through the world, whether individually, within their community, or in broader society. Through thematic analysis of the photographs and accompanying narrative, three overarching themes emerged regarding the experiences of youth with incarcerated parents: personal identity, community identity, and societal identity. On the individual level, youths shared about the interruption of the whole, meaning family structure or family traditions. On the community level, photographs depicted disorganized communities, poverty, over-policing, and lack of protection, as they did not feel safe with police presence. On the societal level, participants identified unfair systems and duality, highlighting the persistent racial and economic inequalities that shape their experiences. Race and racial identity were key themes at all levels of identity. Race was a critical component in community policing, arrests and incarcerations, and media coverage of crime.

These race-specific components suggest the relevance of the existing carceral state to the dual consciousness expressed by the study participants. Their lived experiences exemplify in practice the implications stated by theorists about Black disenfranchisement in the prison system itself, and mirror as well the concerns of theorists on the direct and negative factors disproportionately suffered by Black children of incarcerated family members (

Maruschak et al. 2021).

5.1. Personal Identity

Participants shared the myriad ways that incarceration impacted them, their families, and their communities. The theme

interruption of the whole referred to the disruptions in families, family traditions, familial relationships, and the support the youth failed to receive because of this interruption. It became apparent while engaging with these children and youth that many of their family members had been or were incarcerated. One of the youths took a picture of flowers (

Figure 1) because it reminded him of his brother, who was also incarcerated. He stated that “It’s a memory of how my brother gives my mother flowers every year for Mother’s Day; most days we reminisce about how he impacted our family in a positive way; My brother is an important piece of our family and sadly he isn’t here; hope and pray for the best”. Two other male children experienced the basketball hoop photo (

Figure 2) very similarly. One saw his time playing basketball in his neighborhood as helping him “…replace a missing link in my life, one that’s my father”. A separate youth saw the basketball hoop from a strength perspective. He never met his biological father, and his uncle stepped into the role of a father figure to help support his family. He told the group that “…basketball fills in the missing link in his life…. So that basketball helps [me] stay on the right track and be positive”.

5.2. Community Identity

High-poverty neighborhoods lack affordable housing, access to jobs, good schools, and critical resources, all of which impact reentry for returning parents. Children of incarcerated parents are significantly less likely to live in neighborhoods that can be supportive of families (

Annie E. Casey Foundation 2016). Community identity for these youth is heavily influenced by their community experiences, urban trauma, and poverty. Participants highlighted the impact of surveillance and police presence in their community. The theme of

lack of protection emerged in multiple ways, including within the community, the police, and the school. At the community level, youth felt unsafe and fearful as a result of community divestment and disorganization. Many of the participants took photos of abandoned and boarded-up homes (

Figure 3). A female child talked about how their neighborhood was full of boarded-up and empty homes where children and adults caused trouble or, worse, that “someone died in the house”. Another male participant stated that they are abandoned because there are no employers in his community. He shared that “people can’t afford the rent because they can’t get good jobs”. An older youth added, “the house got closed down and people got evicted. They were evicted because they didn’t pay the rent because they were drinking. When people go to jail—people start to hurt. People have no house they are hurting—homeless. Drinking may have caused it. I feel scared when I see it. People in the neighborhood may throw rocks at it. Inside, kids may be shooting music videos”.

5.3. Social Identity

The social identity of youth with incarcerated parents is shaped by interactions with peers, family members, and the wider society. The theme of

unfair systems ran throughout the photos and narratives, as they frequently critiqued systems and societal structures that the photographers viewed as unjust. A common subject was the criminal justice system itself, with several photographs of jail facilities, courthouses, and police in their community (

Figure 4). One of the older female youths reacted very negatively to the several criminal justice photos. When asked by a researcher what her expression meant, she shared the following:

“The first picture is a police car, and we said that it was important because there are so many in our community. And they take away someone you love. And usually, they’re in communities where it’s a majority minority people and you won’t ever really see them in upper dominant White communities. Then it’s like you don’t see them in those communities but they come so quick when something happens, but then they don’t really come that quick when something happens here, but then they’ll take anybody who they see down. And I said that it’s upsetting because people, innocent people, are getting taken away to jail, but the guilty people are still running the streets”.

Similarly, a second female participant stated

“The problem with it is that they are always in majority minority communities. With so many being in our communities they want to take us down so quick so that we are always beneath them. In a White community they as quick (sic) as can be but are never in their communities. The whole system just makes me upset because they innocent people need justice and the guilty people are not always minorities.”

When two of the younger male children were asked to reflect on the photos, he said, “And I. When you see a police car, you shouldn’t have to feel scared, you should feel safe. But as people of color, in minorities, you feel afraid”. A separate older male child opened up about seeing an intoxicated man on his street, and someone called the police on him. The child said

“So say there’s a drunk guy outside. You don’t need to attack him and hurt him because he’s drunk. You get what I’m saying? You can come to him and you can calm him down or could be like we’re gonna take you in, just for some questions, just for you to relax. They act as if he just killed everybody in their family. And it’s never that serious. They take matters into their own hand. They probably feel like they don’t need to. And that’s not okay”.

5.4. Duality

The concept of duality emerged as a significant theme in how the youth navigated their lived experience of parental incarceration. This duality was evident on all levels: personal, community, and social identity. On an individual or personal level, the duality of the meaning of a locked prison door (

Figure 5) represented both painful separation and joyous reunions. A male child said, “This is the door that took my dad for a long time; Every time my dad went through those doors I was hurt”. A female child had similar sentiments to the photo, stating

“The prison door is important to me because it symbolizes a bitter and sweet time. It reminds me of when they took my dad from me but it also reminds me of when I was able to see and talk to my dad again. This was when his sentence was finished and when we went to visit him. Visiting helped me a little just seeing him was a blessing, but every time I left, I felt the reality of him still being locked up”.

Within their community, they often straddled the duality within their school environment, especially for those who attended Predominately White Institutions (PWIs) (

Figure 6). They often stated how it was a small group of Black children bussed into the suburbs from the city in an environment full of White staff, teachers, and other students. All the participants reflected on how uncomfortable and scary it was for them to be in these environments where they did not feel like they belonged. One of the male participants said

“[The Black students] don’t really talk about [our fathers being incarcerated], ‘cause I feel like they don’t wanna talk about it. I feel like the White people get hurt and they get upset. Well, we’re talking about it on our own with the kids, they’re always on the person who’s wrong -they’re always on their side. It upsets me because sometimes, they say racists things but they don’t think that they’re saying it”.

A female student started talking to support her peer by saying, “when you confront them on it, they wanna go and tell the Dean …. you get in trouble. But how are you getting in trouble when it’s them?” Another male student joined the conversation and said “that’s why I literally only talk to them in school because it’s like you’re walking around on eggshells around everybody. ‘Cause you can’t say certain things at my school. It’s hard.”

An older male student reflected on what it was like being in a PWI and having an incarcerated father. He stated that “none of their parents have been incarcerated before, so they might think that my parents are dangerous”. An older female participant expanded on this. She stated

“Yeah and at our school they talk about everything that happens in their family. Like this one girl, in one of my classes, she’s like, “Oh my dad’s in the FBI.” They talk about everything. So I feel like if their parents had been incarcerated they would have said it. But, the way they act, if they were you would never guess that. But they’ll look at… If their parents were incarcerated it like “Oh my god I feel bad for you.” But if I said that or she said that it’s like, “Oh you’re dangerous, your dad’s a bad person.” But that’s not the case, you can’t always just assume. It’s like… They’re always like, “Oh are you from the hood?” The stuff they say, it makes me so mad”.

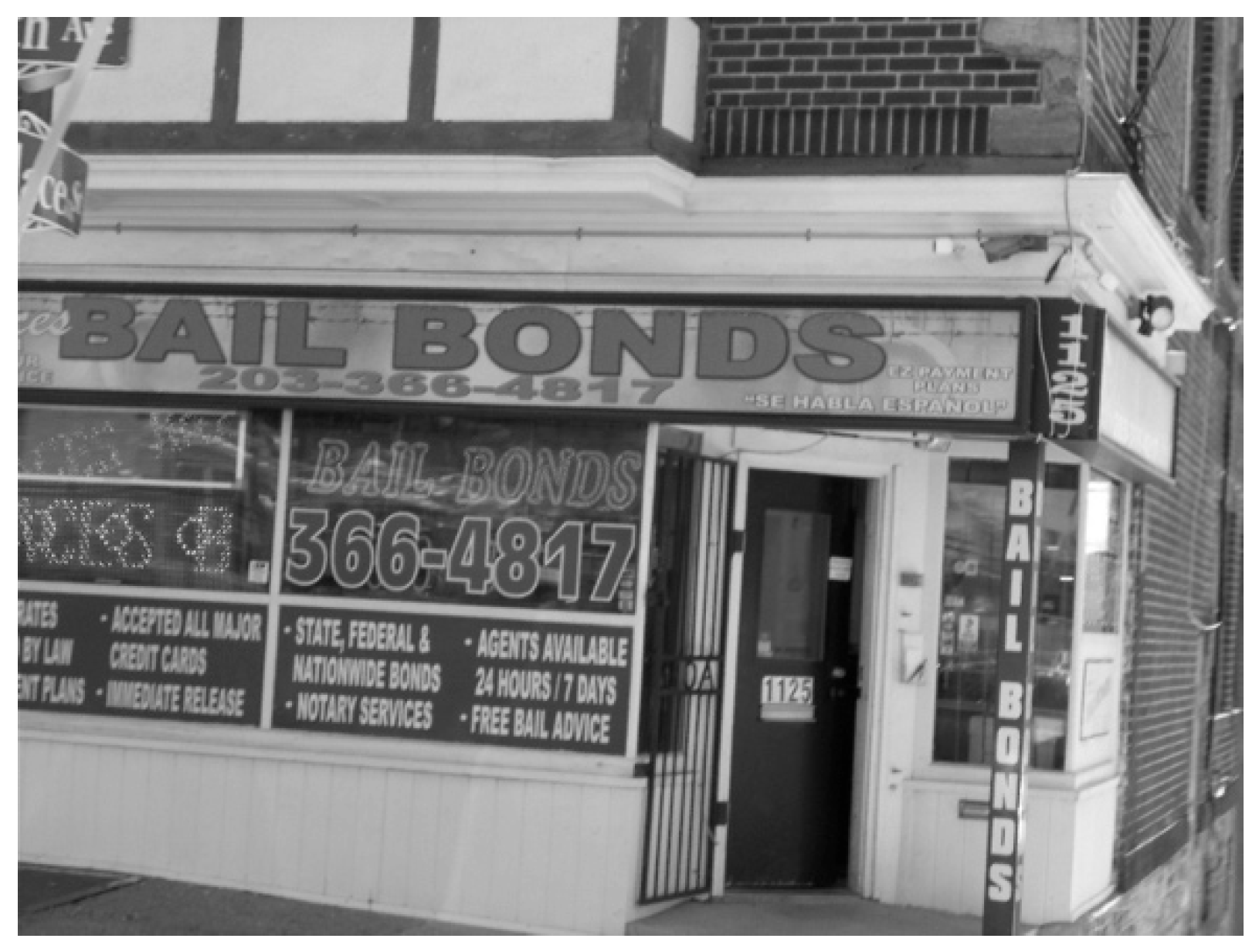

At the societal level, the duality is expressed by those who see poverty as the root of illegal activity and how society expects them to fail. One of the older male participants took a picture of one of the many bail bond shops (

Figure 7) in his community near his home. He said

“You see a bail bonds shop which are common around the community—we had to go there when my dad got encarcerated (sic); I think society expects us to fail which is why there are so many bail bond shops; Every time my dad gets locked up we have to go to a bail bond shops and it causes money problems in the household. I think the situation exists because of poverty and people want to make money reacting to illegal activities; Important jobs more open to people in poverty and who may have been encarcerated (sic) before”.

This duality highlights the youth’s layered, multifaceted identity negotiations, illuminating the resilience and adaptability required to reconcile these diverse and opposing identities within themselves and their environments. In summary, the findings give voice to the unique vulnerabilities faced by youth who have experienced parental incarceration. Their photographs and narratives poignantly depict environmental contexts marked by a lack of protection, fraught encounters with unfair systems and societal injustices, and marginalized communities depicted by poverty and over-policing. The youth perspectives elevate critical awareness of the compounded adversities this marginalized population navigates daily.

5.5. Mother’s Focus Group

A notable and affirming aspect of the project was the decision to convene a separate focus group with the mothers of the children involved in the Photovoice research. Initially present as transportation providers, the mothers began by sitting quietly as the youth and researchers collaborated. However, as they grew more comfortable, they started sharing their thoughts on the issues their children raised. To honor both the youth’s voices and the mothers’ perspectives, we organized a distinct focus group for the mothers, facilitated by one of the authors.

The insights gained from this discussion reinforced the concerns expressed by the youth. Once gathered in a formal setting, the mothers openly reflected on the themes their children had identified. Over approximately 70 min, they engaged in a candid discussion about the challenges they and their children faced due to a loved one’s incarceration. Many were struck by the depth of their children’s observations, particularly regarding the meaning behind the photographs they had chosen. One mother was especially moved by her son’s photo of a neighborhood liquor store, which he described as a place where “people get in trouble”. She had not previously realized how clearly her son connected substance availability in their community to his father’s incarceration. Another mother acknowledged her daughter’s description of feeling “like a prisoner herself” when visiting her father in jail, a perspective that led the mother to reflect on her own experiences of criminalization in those visits.

As the conversation unfolded, the mothers gained a deeper understanding of their children’s emotions, recognizing how incarceration affected the entire family. Several admitted to avoiding difficult discussions, unsure of how much to share or how to frame their experiences. A grandmother who had taken custody of her granddaughter reflected on her tendency to “only say nice things” about the child’s incarcerated mother, fearing that expressing her own anger might negatively affect her granddaughter. Other mothers resonated with this sentiment, acknowledging how their attempts to shield their children from pain had, in some cases, prevented open and honest conversations about incarceration’s emotional toll.

Prompted by shared reflections, the mothers began confronting their own avoidance and insecurities regarding their children’s relationships with their incarcerated parent. Many expressed feelings of sadness, anger, and shame—not only over their loved one’s incarceration but also over their own experiences of stigma. One mother admitted, “I didn’t think I should say anything bad about their dad”, before realizing that her lack of honesty confused her son, who sensed the omission. Others echoed this realization, describing how their children’s participation in the Photovoice project encouraged them to be more open about their own emotions.

One mother reflected that her confidence in parenting grew when she stopped suppressing her emotions and instead embraced open conversations. This shift improved her relationship with her son, as they began to share their feelings of sadness, embarrassment, anger, and hope. By broadening discussions beyond the simple label of “dad in jail”, she was able to acknowledge both positive and difficult aspects of their family’s past, allowing her son to process his emotions in a healthier way. This newfound openness also helped her convey to her son that he was not destined to repeat his father’s path, a message she emphasized by stating, “It let my son understand that he does not have to go to jail” like so many other Black teens in their neighborhood.

The mothers’ experiences paralleled the themes of trauma, stigma, and disempowerment that their children expressed in the Photovoice project. However, they also highlighted an additional layer of complexity—their struggle to balance protecting their children’s relationships with their incarcerated parent while shielding them from the societal shame they themselves endured. Many described a pervasive sense of rebuke in their social environments, particularly within their congregations and children’s schools, where they felt pitied or diminished due to their association with incarceration.

Ultimately, the mothers found that the insights their children shared during the Photovoice project alleviated some of their own shame and anxiety. By witnessing their children articulate complex emotions, they felt reassured that their children were processing these experiences in ways that did not necessarily lead to destructive outcomes. The group expressed a renewed sense of hope that, through honesty and open dialog, they could better support their children in navigating their circumstances. This process of reflection also fostered a sense of liberation from the constant vigilance they had previously felt—monitoring their children’s behavior to prevent them from “getting into trouble”. By embracing transparency and emotional openness, the mothers gained confidence in their children’s ability to make positive choices, reinforcing a vision of resilience and agency in the face of systemic challenges.

6. Action Steps

The goal of this research was to provide a platform for the youth to share their lived experience, challenges and hopes through photography and storytelling. By leveraging Photovoice, this project aimed to raise awareness, influence policy, and create a supportive dialog around the impact of parental incarceration on youth. Participants gathered to identify potential action steps to address the identified issues. Ideas that were raised included policy implications for the Department of Corrections, such as visitation, treatment of incarcerated individuals, and support for individuals upon release. Additionally, the youth identified disparities within education systems and media coverage related to race. At the time of this study, two Black girls were missing from a neighborhood city. One of the female participants was frustrated that the media was not aggressively trying to find her. She stated, “One of them, they just found dead, but they’re not even broadcasting about the other one. Like, they don’t even know where she’s at, and nobody cares. They talk about that lady [White woman from a suburban neighboring town] every minute of the day”. A separate male participant offered, “when you watch TV and they’ll show you witnesses. You ever see a black witness? They always show Caucasian witnesses”. Another male participant observed that

“when you look at news reports, they use mugshots of the black people to describe their crimes, even if they weren’t in the wrong. But when a White person does a horrible crime, they use a Snapchat filter or a picture off their phone that the family has given to the news, and I don’t feel like that’s right”.

An older female participant acknowledged feeling frustrated by how invisible she feels in society unless a Black person breaks the law. She reflected on how the media seldom highlight the negative things that White people do: “When [White people] do a crime, it’s like they don’t put it in [the news], but once one of them dies, it’s everywhere”. A female participant sitting next to her retorted, “Let’s say it’s a White person that shoots up a school, or if they do a thing that’s really extreme. We just gotta steal from a store and we’re all over the news”. Another male participant observed how the media portrays Black and White people and why they broke the law. He stated, “It’s framed as something is wrong with them. It’s not ‘Oh he’s sick.’ And it has to be something deeper. Why couldn’t it just be, he just did what he did and he gets charged?”

This level of critical thinking demonstrates critical consciousness raising, a vital step in social change. It is assumed that by raising critical consciousness, individuals will question the reality of their historical and social situations and thereby effect change (

Freire 2018). Transforming social structures requires a critical understanding of oppression and the hegemonic structure of dominant forces in society (

Freire 2018). Critical consciousness and the methodological framework of CBPR were interwoven to address the stigmatization and isolation experienced by children with incarcerated parents. Photography and narrative practices supported youth in telling their stories about the experience of parental incarceration to “externalize” issues of stigma and shame, intending to foster less oppressive discourse regarding the social reality of parental incarceration. Participants were allowed to meet other youth with similar experiences and give voice to their experiences with parental incarceration. Photovoice offers an opportunity to integrate visual documentation and narrative experiences, helping participants recognize their individual and collective power to create opportunities for meaningful social change and informed policymaking. Photovoice has the potential to effectively identify social work interventions at the individual, group, and community levels based on input from the youth most affected.

Likewise, the voices of African American children and their parents speaking through these pages offer powerful support to framing in theory and practice the lived experience of African American children whose lives are directly and negatively informed by the carceral practices of a largely racist white dominated American culture. Their voices provide candid examples of the need for abolition in order, at the very least, to create a body of theoretical and intervention roadmaps to understanding the course of Black American children’s lives lived with a parent lost to the carceral state. With a tremendous debt to this first-hand understanding from Black children in Bridgeport, CT, of the double consciousness described a century ago by W.E.B. Du Bois, it is the goal of this research to interpret and underline the significance Abolitionist frameworks for this and similar participatory research projects regarding U.S. policing and criminal justice.

7. Discussion and Implications

This research project demonstrates the value of using Photovoice and CBPR as a powerful way to highlight the perspectives of invisible youth and communities and promote individual and collective empowerment. The findings from this Photovoice study with youth who have experienced familial incarceration have several important implications for social work practice on micro, mezzo, and macro levels. At the micro level, the findings underscore the essential role of trauma-informed, family-centered social work interventions to address the mental health needs, academic supports, and family reunification services required by youth with incarcerated parents. Mezzo-level implications call for institutional reforms within schools and correctional facilities to cultivate more inclusive, empathetic environments that repair impacted communities’ fractured relationships and social fabric. From a macro perspective, this study aligns with and contributes to the growing “defund the police” movement, providing empirical evidence for reallocating resources away from punitive criminal justice approaches and toward community-based solutions. Participants’ double consciousness highlights the imperative for social workers to engage in Abolitionist organizing, policy advocacy, and collaborative research that centers on the leadership of directly impacted populations in developing alternatives to mass incarceration.

7.1. Trauma-Informed Approaches

The theme of lack of protection highlights how this population faces significant threats to their emotional and physical safety. The images and narratives convey ongoing exposure to trauma through unstable living environments as a result of poverty, dismantling family systems, and over-policing. Over-policing in marginalized communities is a traumatic experience that needs to be addressed. Social workers need to be trained in trauma-informed practices that account for the complex trauma histories of these youths and their neurological, emotional, and behavioral impacts. This may include screening for traumatic stress, teaching coping strategies, and providing referrals for trauma-focused therapeutic interventions.

The findings related to physical space demonstrate the detrimental effects that poverty and urban environments can have on youth development. Social workers should provide case management to secure safe, adequate, and permanent housing accommodations for families impacted by poverty and incarceration. At a broader level, social workers can push for policy reforms and initiatives to increase affordable housing access.

7.2. System Navigation

The unfair systems theme underscores how youth with incarcerated parents frequently face compounded oppression across multiple systems like policing, criminal legal systems, education, housing, and economic structures. Social workers can act as system navigators to help families access resources, advocate for rights, and negotiate complex institutional policies and practices that create undue burdens. Efforts should be made to increase collaboration and coordinate care across sectors serving this population.

7.3. Mezzo

The findings from this study also have significant implications at the mezzo level, underscoring the critical need for community-based resources and institutional reforms to support families impacted by incarceration. People with multiple arrests are disproportionately Black, low-income, less educated, and unemployed, with the vast majority of arrests for non-violent offenses (

Jones and Sawyer 2019). Rather than incarcerating individuals and contributing to further diminishing economic prospects, public investments in employment assistance, education and vocational training, and financial assistance are critical to mediate the conditions that lead marginalized individuals to police contact in the first place (

The Sentencing Project 2023).

As the “defund the police” movement has emphasized, overreliance on punitive criminal justice approaches has come at the expense of vital social services and family support systems (

Dettlaff et al. 2020;

Kaba 2021). During the incarceration of a family member, communities must be equipped with a range of resources to address the multifaceted challenges faced by impacted children, spouses, and caregivers. This includes accessible mental health counseling, support groups, childcare assistance, legal aid, and transitional housing (

Harrell 2024). By investing in these wraparound services, social workers and community partners can help mitigate the destabilizing effects of parental incarceration and promote family preservation and reunification.

Similarly, schools play a critical role at the mezzo level in supporting youth with incarcerated parents or family members. Trauma-informed curricula, grief counseling, and teacher training are essential for educators to understand these students’ unique social-emotional and academic needs (

Dettlaff et al. 2020;

Kim 2018). Fostering a culture of empathy, belonging, and academic support can help buffer against the stigma, anxiety, and disruption that youth often experience. Furthermore, correctional facilities themselves must be transformed to prioritize the well-being of incarcerated individuals and their families. This includes implementing visitation policies that are more accessible and family-centered, providing parenting classes and family therapy, and connecting those re-entering the community with robust reentry planning and support services (

Harrell 2024;

Kaba 2021). By addressing the intergenerational trauma caused by incarceration, these institutional reforms can begin to repair the fractured relationships and restore the social fabric of affected communities.

Overall, the findings of this study point to the need for a multi-pronged, community-based approach to supporting families impacted by the criminal legal system. Investing in such mezzo-level interventions represents a vital step in dismantling the cycles of poverty, violence, and mass incarceration that have devastated marginalized communities for generations.

7.4. Macro

The findings from this study have significant macro-level implications for social work practice, policy, and research, aligning with the growing “defund the police” movement. This movement calls for reallocating funding from traditional law enforcement toward more community-based, preventative, and restorative approaches (

Dettlaff et al. 2020;

Kaba 2021). Participants’ narratives underscore how overinvestment in punitive criminal justice systems and underinvestment in disadvantaged communities have entrenched cycles of marginalization, trauma, and violence in their communities.

Redirecting resources toward a community care model is vital in dismantling this systemic machinery of oppression (

Kim 2018). Funds could be reallocated to expand access to quality, affordable housing, vocational and educational training programs, comprehensive mental health and substance abuse treatment, and restorative justice initiatives that repair harm and rebuild relationships (

Harrell 2024). Such holistic, community-driven investments have demonstrated greater effectiveness in promoting long-term public safety, individual well-being, and collective healing than aggressive policing tactics (

DeVeaux 2013).

At the policy level, this study adds to the growing momentum for legislative reforms centered on racial and economic justice. Advocacy efforts should target the dismantling of “tough on crime” policies, sentencing enhancements, and resource allocations that have disproportionately impacted marginalized communities (

Dettlaff et al. 2020). Instead, policymakers must be compelled to prioritize community reinvestment, reparations, and the scaling up of evidence-based strategies shown to interrupt cycles of poverty, violence, and mass incarceration (

Kaba 2021).

Furthermore, research agendas within social work should increasingly center on the perspectives and leadership of directly impacted populations in developing and evaluating alternative public safety approaches (

Kim 2018). Participatory action research and community-based partnerships can amplify the voices of those with lived experiences to drive systemic transformation (

Harrell 2024). Expanding this praxis-oriented knowledge base will be crucial for translating the defund movement’s transformative vision into tangible, sustainable change.

7.5. Empowerment Approaches

The process of taking the photos and discussing them with others who share this reality is empowering to individuals, and the power of the visual image is a form of communication (

Wang 1999). Through Photovoice, these youth could artistically document and critically analyze the oppressive conditions shaping their realities. Social workers should similarly aim to uplift youth voices and take an empowerment-based approach that views them as experts on their own experiences. This could involve using additional arts-based methods, narrative practices, and participatory approaches that deconstruct power imbalances and reframe youths as agents of personal and social change.

Overall, the findings of this study call for a radical reimagining of the state’s role and the distribution of societal resources. By shifting towards an Abolition practice model, social workers can leverage macro-level interventions to address the root causes of social problems, repair fractured relationships, and begin the process of healing and justice for long-marginalized populations. Social work practice with this population necessitates a multi-level, ecological perspective that addresses individual and community trauma while also dismantling unjust systems and transforming the physical and societal contexts that produce adversity for youth impacted by parental incarceration.

8. Limitations

A hallmark of the CBPR approach is ensuring that study participants have access to study findings and opportunities to share their opinions (

Minkler and Wallerstein 2008). Phase Four of the project aimed to share the results with study participants and community stakeholders to develop plans for future areas of collaboration, policy implications, and future research with Connecticut State Representatives and other policymakers and create guidebooks and action steps with participants. However, due to the global pandemic in 2020, these final steps were never realized.

Participants ranged broadly in age (9–17) and different developmental stages, which impacted the youths’ insight and critical thinking abilities. The older teenaged females demonstrated a deeper understanding of the systemic issues within their community and school systems. The younger males’ thinking was slightly more concrete. However, the youth attentively listened to each other and built off each other’s insights very well.

Additionally, some of the youths had incarcerated family members, not necessarily parents or guardians, whom they were dependent on, which may have impacted the findings.

9. Conclusions

This community-based participatory research (CBPR) study, grounded in critical theories of double consciousness and comparative conflict, has illuminated the multifaceted lived experiences of Connecticut youth with incarcerated parents, and critical theories are reflected in Abolitionist practice paradigms that explain and reframe into anti-racist practice the post-emancipation practices that have literally and metaphorically maintained social inequality for Black Americans. Through the powerful medium of Photovoice, participants have documented the criminal legal system’s personal, relational, and systemic impacts, underscoring its devastating consequences for marginalized families and communities.

At the core of these findings is the development of a “double consciousness”—an ability of participants to see both the humanity and injustice inherent in their circumstances. This double awareness, born out of the stark contrast between their loved ones’ inherent worth and the dehumanizing realities of mass incarceration, has fueled a profound desire for systemic change that is plainly articulated in Abolitionist praxis. Participants’ narratives powerfully illustrate how the criminal legal system operates as a machinery of oppression, entrenching cycles of trauma, stigma, and disempowerment, and how that machinery might change to repatriate and value as full participants its disenfranchised citizens, including African Americans.

The implications of this study span the micro, mezzo, and macro levels of social work practice, research, and advocacy, and call as well for the intentional and immediate inclusion of Abolitionist social work practice as a standard social work practice platform. By reallocating resources away from punitive criminal justice approaches and towards the community-driven, preventative solutions espoused in Abolition practice, social workers can begin to dismantle the systemic machinery of oppression. Expanding research agendas to center the leadership and perspectives of directly impacted populations will be crucial in translating this transformative vision into tangible, sustainable change.

Ultimately, this CBPR project has powerfully amplified the voices of marginalized youth, illuminating how the criminal legal system violates the humanity and dignity of individuals, families, and communities. The implications compel social workers to radically reimagine their roles and responsibilities—to move beyond reform and towards creating more equitable, restorative, and healing-centered societies.