Abstract

There is scant literature on migrants with an entrepreneurial background and who return to their country of origin. Using a transnational theoretical approach, we seek to contribute to research in this field by analysing the return strategies and expectations of Colombian migrant entrepreneurs participating in the Programme Migration and Diaspora (PMD). This programme is implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH (German Society for International Cooperation, Eschborn, Germany) on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ, Berlin, Germany). To this end, a mixed-methods study was conducted. Likert scale questionnaires and semi-structured interviews were applied to twenty-seven entrepreneurs participating in the programme, analysing quantitative and qualitative variables. Migrants seek to contribute to Colombia’s development through entrepreneurship, looking for various commercial connections for which security and planning conditions are necessary. They see entrepreneurship as sustenance, which in most cases results in transnational links between Germany and Colombia. For that to happen, contacts and acquired experiences are fundamental, as well as tangible and intangible resources, amongst which the information and support for entrepreneurship granted by GIZ stand out. Generally, it is essential to continue strengthening differentiated and comprehensive support strategies for all types of migrant entrepreneurs in destination countries.

1. Introduction

Migration as a process implies multiple dimensions of mobility, including emigration, return, and circular mobility. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines return by including different types of returnees and their locations: “In a general sense, an act or process by which a person returns or is taken back to their starting point. A return may occur within the territorial boundaries of a country, as in the case of returning internally displaced persons and demobilised combatants; or between a country of destination or transit and a country of origin, as in the case of migrant workers, refugees or asylum seekers” (IOM 2019a, p. 206). In that sense, return can be viewed “as a continuous rather than a completed movement across the globe” (Riaño 2022, p. 5543).

The IOM considers different types of return: a voluntary return when a person wants to return, a spontaneous return, if it is carried out without any state support or national or international assistance, and a forced return when a person returns against her/his will by virtue of an administrative or judicial act or decision.

The literature on return migration highlights returnee entrepreneurship as a dual mechanism that facilitates both reintegration and local economic development (Batista et al. 2017). Recognising this potential, international actors have developed programmes to support returnees and prospective migrants in launching businesses, positioning entrepreneurship as a catalyst for sustainable growth.

A paradigmatic example is the Migration and Diaspora Programme (PMD), implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) under the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). Within this framework, the Business Ideas for Development (GfE) initiative targets Colombians residing in Germany, providing financial grants and mentorship through transnational incubators to promote enterprise creation in Colombia. Participants—classified as transnational entrepreneurs (TEs)—engage in an annual competitive selection process, during which proposals are assessed by bi-national juries. Finalists pitch their business ideas, and selected winners receive tailored support (GIZ 2023).

This initiative is part of the broader German–Colombian cooperation agenda, established through the General Agreement on Technical Cooperation (1998) and the Financial Cooperation Agreement (2012). These accords prioritise peacebuilding, transitional justice, environmental governance and sustainable development (GIZ 2024), in alignment with the BMZ 2030 strategy’s pillars of peace, sustainability and equity (BMZ 2020). Colombia’s status as a priority partner country reflects its regional influence, commitment to the 2030 Agenda (United Nations 2015) and climate policy goals articulated in its National Development Plan 2022–2026 (Departamento Nacional de Planeación [DNP] 2023). Ongoing intergovernmental dialogues ensure coordination of priorities and territorial interventions (OECD 2023).

Complementing PMD’s efforts, initiatives such as the Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) programme (Organización Internacional para las Migraciones [OIM] 2023) and the European Return and Reintegration Network (ERRIN) provide returnees from Europe and North America with vocational training, seed capital, and psychosocial support. At the national level, Colombia’s Programme Colombia Nos Une—supported by Law 1565 of 2012—offers entrepreneurship training and mentoring through partnerships with the National Learning Service (SENA), thereby enhancing returnee autonomy and fostering local economic resilience (Cancillería de Colombia 2023b, 2023c).

While other global programmes address migration for development—such as the joint IOM-UNDP Global Programme on Making Migration Work for Sustainable Development (2019–2023), funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, and the EU-funded Mainstreaming Migration into International Cooperation and Development (MMICD)—Colombia has not been among their target countries. In contrast, Colombia Nos Une focuses specifically on facilitating productive return through access to SENA’s Fondo Emprender, which promotes the creation of enterprises and the generation of employment in Colombia through reimbursable seed capital. However, it does not adopt a transnational approach, as only individuals who have returned to Colombia are eligible to participate.

Germany’s Migration and Diaspora Programme (PMD) currently operates in 24 countries, of which only 10 implement the Business Ideas for Development (BID) component focused on transnational entrepreneurship: Cameroon, Colombia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Nigeria, Serbia, Tunisia, and Vietnam. This study focuses on the Colombian case, given GIZ Colombia’s interest in generating deeper knowledge of foreign direct investment (FDI) trends to inform future policy interventions. While European cooperation has historically concentrated its efforts in Africa and Eastern Europe, this research seeks to address the gap in data concerning the role of Latin American migrants in development processes.

Between 2019 and 2023, the PMD has supported approximately 270 Colombians across its various components, including return for development, short-term expert missions from the diaspora, support for diaspora organisations, and transnational entrepreneurship. According to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE 2020), there are around 24,000 Colombians registered in Germany. This would represent 3.5% of the programme’s outreach. The Colombian counterpart, Colombia Nos Une, has helped promote awareness of these programmes and offers additional support through its “productive return” strategy in collaboration with SENA.

However, it remains difficult to assess the general level of awareness among Colombians in Germany regarding such initiatives, as this research specifically focuses on the characterisation of transnational entrepreneurs residing in that country and who have resorted to GIZ calls for migrant entrepreneurship.

Overall, these initiatives reflect a comprehensive approach that integrates migration policy with sustainable development goals. By positioning returnees and diaspora communities as agents of social cohesion and institutional strengthening, they go beyond simple reintegration and align diaspora engagement with broader objectives of inclusive growth and climate action (BMZ 2020; OECD 2023).

In principle, there is great potential for this type of programme since, according to DANE (2020), 5,499,220 Colombians live abroad, mainly in the Americas and Europe. However, studies on the reintegration of return migrants through entrepreneurial ventures are scarce. Further, the postulate that the entrepreneurship of returned migrants has great potential to help their reintegration while generating local employment lacks sufficient empirical support, as few studies investigate to what extent this claim is true, or not, and in what specific national contexts and circumstances it may take place. As Riaño (2022) shows, most scholars have been interested in the question of what factors influence the likelihood of a return migrant becoming an entrepreneur (Thomas and Inkpen 2013), pointing to schooling, foreign language proficiency, savings abroad (Piracha and Vadean 2010), length of stay abroad (McCormick and Wahba 2001), international work experience (Black and Castaldo 2009), and preparedness to return (Bolzani 2023) as key factors.

The idea of migrants generating impulses for development through entrepreneurship has been criticised by some scientists who argue for carefully considering the different conditions that exist between different contexts: “The geographical context—i.e., the places to which migrants return—is important because location affects the kinds of opportunity that returnee entrepreneurs can access” (Riaño 2022, p. 2). Indeed, the few studies that show a positive link between migrant entrepreneurship and the local economy are concentrated in countries that strongly promote the return of entrepreneurs active in the high-tech and IT&C sectors, such as China. Filatotchev et al. (2011), for example, conclude that returnee entrepreneurs active in Beijing contribute to the promotion of innovation within local companies active in the high-tech sector. For Kenney et al. (2013), some returnees from China, India, and Taiwan have played an important role in the further development of the ICT industry, but once local entrepreneurs had already set them up. In contrast, the study of the small business projects of Colombian returnees living on the Colombia–Venezuela border (Riaño and Aliaga Sáez 2024) shows the negative effects of a geopolitical context characterised by territorial struggles between illegal armed groups and lacking support from the Colombian state, which creates an extremely vulnerable environment for entrepreneurs.

On the other hand, entrepreneurship in any latitude requires special characteristics and conditions in the entrepreneur so that his/her business venture can be successful. According to Tovar et al. (2018), the probability for a person to become an entrepreneur “is associated with meeting other entrepreneurs, the perception you have about the opportunities offered by the country, self-confidence in the abilities you have to start a company, gender, age, educational level, having made savings and contacts while abroad, and the period (context) in which the return occurs” (Tovar et al. 2018, p. 188). For Tovar et al. (idem), it is more relevant “knowing someone who has started a company in the last two years, perceiving that they have the skills to start a company, having established contacts with people who could be partners or suppliers by having a company in Colombia and saving money while living abroad” (Tovar et al. 2018, p. 188). This statement is related to the resources that migrants have as social networks (Cassarino 2004).

Indeed, returnees face many challenges to their entrepreneurial projects. Returnees in Jiangxi Province, China, face a series of obstacles, such as lack of funding, a high level of bureaucracy in their steps to initiate a business, difficulties to protect their rights and interests, inefficient implementation of governmental policies, restrictions in land usage, high levels of taxation, and others (Ouyang et al. 2010). Local connections are mandatory for the initiation and expansion of entrepreneurial ventures in India (Pruthi 2014). The narrow view of government and bank policies also has a negative effect. Riaño (2022) shows that in Colombia, credit-support programmes by the government are only conceived for those with university training and businesses with innovative technologies. Additionally, many returnees are not supported by banks because after years of being abroad they lack a loan collateral. Moreover, a particular burden is placed on women, who juggle childcare and the struggle to succeed with their entrepreneurial ventures. In Ghana, a hasty departure from host countries, high levels of family dependence on returnees, weak governance, and the absence of reintegration policies are not only detrimental for business projects but also foster re-migration (Mensah 2016).

At present, we have limited knowledge about the experiences of Latin American migrants (Riaño 2013) who return to their countries of origin with an entrepreneurship project, particularly as concerns returned Colombians (Riaño 2022). Colombian entrepreneurs associated with the PMD programme have a double challenge, since they must not only have a holistic overview of the regulatory processes for both Germany and Colombia but must also look for financing strategies that allow them to further develop their businesses according to the stage of the venture in which they are. On the other hand, there are scant detailed studies that contrast the objectives of programmes, such as “Business ideas for development”, with an in-depth analysis of the experiences, strategies, and entrepreneurship expectations of returnees in South America. An exception is Riaño’s (2013) assessment on the impact of the Swiss government’s financial assistance and training programme for undocumented Ecuadorians to return to Ecuador and set up a small business. Riaño concludes that three key areas need to be addressed: (a) Insufficient economic assistance and lack of long-term perspective. The resources received are only sufficient for the first few months. Given the lack of support from the Ecuadorian government and the lack of access to bank credit in Ecuador, returnees are unable to continue with their micro-enterprises. (b) Insufficient training and lack of monitoring. Training received in Switzerland is insufficient to handle the complexity of running a business. (c) Lack of a family perspective. Returnees are not simply individuals but return with their families. The adaptation of their children and the gender role tensions with their partners in the new living context create health problems and difficulties in running their businesses.

We seek to contribute to advancing our understanding of return by addressing the research gaps in light of the role played by the individual characteristics of returnees and their return contexts for entrepreneurship. Further, although return is often seen in the research literature as a bidirectional phenomenon (IOM 2019b), we take a transnational theoretical perspective whereby mobility is seen as multidirectional and return as not definitive (cf. Riaño 2022), an issue that we will develop later. Therefore, our goal is to generate a fruitful discussion that allows us to improve the accompaniment and facilitate the management of the entrepreneurship initiatives of the returnees.

This article is structured into five sections: the introduction highlights the importance of engaging with migration, return, and entrepreneurship studies and examines specific conditions that may facilitate or hinder the economic reintegration of returning individuals; secondly, the methodology is described, employing mixed research methods. This includes a questionnaire featuring Likert-scale questions and semi-structured interviews, as well as quantitative and qualitative analyses of the experiences, strategies, and expectations of twenty-seven Colombian migrants participating in the Migration and Diaspora Programme (MDP); the third section presents the results from the interviews and questionnaire, outlining the key factors identified for entrepreneurship; the fourth section provides a discussion of the findings; and, finally, the conclusions are presented.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mixed Methods

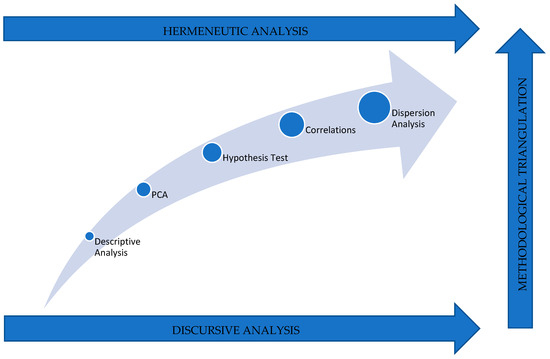

This study used a mixed-methods approach of a quantitative and qualitative nature. To approach the problem question, a questionnaire and semi-structured interviews were applied to twenty-seven entrepreneurs of the PMD. The methodological development of the research process can be visualised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological development of the research process. Source: own elaboration.

At the quantitative level, using SPSS statistical software v.26.0 (IBM Corp 2019), the methodological development began with a descriptive analysis of the data identifying frequencies to characterise the sample. In the second phase, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with direct, oblique rotation in which clusters of variables were identified according to their response orientation to the item with a KMO reliability greater than 0.5. The development of the clusters resulted in factors that, in turn, have regression values, which were identified and labelled.

Thirdly, a test analysis of mean difference hypotheses was applied by taking as a differentiating category the typology of migration; significant differences were identified in some of the relationships generated. Fourthly, correlations were applied between the factors obtained from the PCA, resulting in the consequent dispersion analysis that makes it possible to identify methodological tools and improves aspects of the programme.

The quantitative research design was cross-sectional, in which a survey composed of 102 descriptors was applied, mostly on a Likert scale, using a scale of 1 to 5 where 1 represents the lowest affinity with a statement and 5 represents the greatest affinity, as well as the crossing of elements of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor GEM 2020/2021 (Hill et al. 2022). Following the categories raised in the GEM, individual attitudes and perceptions towards entrepreneurship, motivational aspects, and characteristics of entrepreneurship were taken as a reference. Likewise, demographic data such as age, gender, and education and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic were included.

The influence of the framework conditions for entrepreneurship proposed by the GEM was considered: 1. access to finance for entrepreneurship; 2. government policy: support and relevance; 2.1. government policy: taxes and bureaucracy; 3. government entrepreneurship programmes; 4.1. entrepreneurial education at school; 4.2. post-school entrepreneurial education; 5. transfer of research and development; 6. commercial and professional infrastructure; 7.1. ease of entry: market dynamics; 7.2 ease of entry: market burdens and regulations; 8. physical infrastructure; and 9. social and cultural norms.

Within paragraphs 2 and 3 above, the set of Colombian laws were analysed, some already mentioned above and others in the framework of support for entrepreneurship, which directly or indirectly involve migrants or diaspora within their structure, with a review of their implementation or not within the strategies of articulation of the country with migrants and diaspora and in the context of TE in the case of the PMD.

The qualitative analysis was carried out from a series of variables, obtained mainly from the “sustainable reintegration in return” from the approach of the International Organization for Migration (IOM 2017).

The variables contemplated in the process from the individual level are age, sex, gender, competences, family situation, knowledge, social networks, motivation, self-identity, personal security, own and family financial situation, social position, experiences, beliefs and attitudes, and the emotional, psychological, and cognitive characteristics of the migrant. They also influence the migratory journey, that is, the circumstances of the return, the absence of the migrant, the conditions in the host country, the level of preparation for return, the resources mobilised or level of preparedness for return, and the vulnerabilities faced by the person in the process.

At the community level, the perception of return, stigmatisation towards the returnee, resentment of the assistance received by the returnee, and an enabling environment are influences. Reintegration is also affected by the structural factors of the external environment: prevailing political, institutional, economic, and social conditions at the local, national, and international levels; cooperation between the various government ministries at the local and national levels; policies and legal instruments for returning migrants; the private sector and diasporas; and access to employment and basic services (housing, education, health, psychosocial care, etc.). Discourse analysis of the interviews at the hermeneutic level was carried out through the qualitative software MAXQDA v. 20.0.3., and the main semantic fields were identified for each variable, organising the most relevant elements of the discourse through classification and hermeneutic interpretation (Schreirer 2014).

2.2. The Sample

The number of Colombians in Germany totals 24,000 (DANE 2020). Data from the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Relations (Cancillería de Colombia 2023a) show that from 2013 to 2023, a total of 56,432 Colombians returned as beneficiaries of Law 1565 of 2012, of whom only 193 returned from Germany. This situation creates barriers when measuring transnational entrepreneurship. These databases do not consider Colombians that have transnational businesses and are not in a returning condition. Taking this in account, the sample was composed of twenty-seven entrepreneurs (thirteen women and fourteen men) who correspond to 66% of a total of forty-one people who participated in the PMD un until 2020, and who are part of a typology of Colombians who have migrated abroad and who were classified into one of the following categories:

- Migrant at destination (MD) is the person who has changed his habitual residence. A short-term migration process is between three and twelve months, and a long-term one is more than one year (ten entrepreneurs in this category).

- Returned migrant (MR) is the person who voluntarily returns to his country of origin with the intention of settling and changing his habitual residence again, after having spent a short- or long-term migratory period in the country of destination (two entrepreneurs in this category).

- Intention of return (IR) is a person who has his habitual residence in a country of destination and who voluntarily intends to return to his country of origin, after having spent a short- or long-term migratory period in the country of destination (seven entrepreneurs).

- Re-graduated (RE) is a person who, after having returned to his country of origin and changed his habitual residence (for more than three months), decides to return again to what was his country of destination (an entrepreneur in this category).

- Circular mobility (CM) a form of migration in which people move repeatedly between two or more countries in one direction or the other (you may have a habitual residence in one or both countries) (seven entrepreneurs in this category).

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Interviews

In this section, we describe the results for seven qualitative variables: reasons for entrepreneurship, identity and attitude of the migrant entrepreneur, emotional aspects and vulnerability, the influence of the family and contacts, perception towards the entrepreneur, influence and support of the countries, and income and quality of life.

3.1.1. Reasons for Entrepreneurship

Circular migrants are primarily motivated by the desire to participate in and contribute to the market, utilising their acquired knowledge to develop business ideas, generate economic activity, and earn a living from it. This entrepreneurial spirit is driven by the recognition of investment potential in Colombia, attributed to the country’s qualified workforce and creative potential. The aim to make an impact is intertwined with seeing market opportunities in Colombia and applying lessons learned abroad, particularly in Germany, with a focus on economically viable ideas that also have a social impact. The advantages of entrepreneurship for returnees are linked to the connections established during circular migration and the diverse experiences in different countries. The motivation to become an entrepreneur often stems from witnessing and living through challenges such as violence or economic need in Colombia. Experiences from living in Germany, being exposed to various world cultures, and conceiving ways to conduct business between Colombia and Germany are highlighted as significant factors.

Entrepreneurs living in Germany benefit from new social interactions and a deeper understanding of different cultures, enabling them to develop synergies and position themselves distinctively in Colombia. The negative perceptions of Colombia, widely spread by the media, present an opportunity for entrepreneurs to challenge and change these views through their ventures. The experience of being in Germany is described as instrumental in forging an entrepreneurial spirit. Entrepreneurship is portrayed as a mix of intuition and improvisation, requiring a mindset open to learning and gaining experience. Knowledge about regulations and commercial processes between both countries is crucial, acknowledging a balance between preparation and the unpredictable nature of entrepreneurship.

Key aspects of successful entrepreneurship management include the willingness to promote entrepreneurship, sincerity and transparency in business, team strengthening, defining roles and objectives, customer engagement, trust-building, marketing, securing stable investments, and ensuring sustainability. Ideas promoting social inclusion, legal and tax advice, dedication, and belief in one’s venture are also vital. Understanding market dynamics is essential, emphasising the importance of knowing why a product will be sold in specific markets. Experienced professionals with a background in Colombia or Germany exhibit entrepreneurial tendencies, supported by initiatives like GIZ. Circular migrants leverage their understanding of business ecosystems in both countries to capitalise on emerging market trends. Networking plays a vital role in executing business plans in Colombia. German cooperation involves contributing to Colombia’s economic growth from abroad, with support to returnees driven by entrepreneurial objectives. However, challenges such as corruption, insecurity, and tax misuse in Colombia may deter entrepreneurs from investing and developing their business ideas in the country.

3.1.2. Identity and Attitude of Migrant Entrepreneurs

Migrants encounter challenges in choosing where to settle, leading to identity dilemmas. One entrepreneur grapples with feeling disconnected from their Colombian identity abroad and struggles to assimilate with locals, facing discomfort upon returning to Colombia due to social disparities. Cultural shock from Colombia to Germany complicates reintegration. The migration journey enhances self-awareness, confidence, and empathy, crucial for navigating risks and contexts, particularly in entrepreneurship. Skills like empathy and adaptability alleviate cultural disparities’ intimidation. Circular migrants prioritise adaptability and flexibility, recognising the differing paces of life in their respective countries. Being prepared to leave one’s comfort zone is essential, especially for those considering returning to Colombia, where the entrepreneurial landscape poses distinct challenges. This adaptability also involves a problem-solving approach shaped by familiarity with both cultures.

In Germany, migrant entrepreneurs emphasise the importance of business planning and long-term strategising, understanding the local culture, and adhering to principles of honesty and transparency. They believe in their potential for entrepreneurship while maintaining their Colombian work ethic, which is highly regarded in Germany. Integrating and accepting both German and Colombian cultures is deemed necessary for their business endeavours. Key qualities identified for successful migrant entrepreneurship include strategic thinking, discipline, perseverance, patience, resilience, and a commitment to social responsibility. Additionally, trust and sincerity with oneself are underscored as essential attributes, highlighting the complex interplay of personal and cultural identity in the entrepreneurial journey of migrants.

3.1.3. Emotional Aspects and Vulnerability

The emotional support from family, partners, or friends is crucial for entrepreneurs, acting as a pivotal source of strength and motivation. Staying connected with a supportive network helps maintain motivation in the face of new challenges. Resilience becomes especially significant when adapting to a new context, as migration involves confronting not just a new culture but also different ways of thinking. This highlights the vulnerability of entrepreneurs and their need for a supportive community.

Entrepreneurs considering a return are driven by emotion and readiness to tackle challenges, including doubt and failure. They acknowledge the insecurities of mobility and stress patience, work–life balance, willpower, self-confidence, perseverance, and humility. Being away from family is a challenge, but travel between Germany and Colombia can alleviate nostalgia, facilitating engagement in new roles and businesses. Nostalgia often motivates entrepreneurship in Colombia, despite its emotional weight. Interviewees identified various vulnerabilities, such as the stress caused by the pandemic, concerns about global inflation and rising material costs, lack of knowledge about visa or entrepreneurship processes in Germany, low wages in Colombia, and fears of financial instability upon returning. Returnees and those planning to return worry about Colombia’s complex political and social landscape and its impact on their ability to sustain their living standards amidst economic challenges and unforeseen changes. Entrepreneurs in Germany face barriers related to language proficiency and unfamiliarity with the local culture and bureaucratic system. Recognising the language as a key tool for adaptation, they acknowledge the time and effort required to overcome these challenges, emphasising that adapting to a new culture and language is a gradual process that can take several years.

3.1.4. Role of Family and Personal Contacts

Family plays a vital role in the entrepreneurial journey of Colombians engaged in circular mobility, providing support that spans work, travel, and business initiatives. Entrepreneurship often becomes a family endeavour, with relatives offering stability and capital. Despite physical distance, migrants in Germany rely on their Colombian families for support, including financial assistance. The decision to return to Colombia is strongly influenced by familial ties, with entrepreneurs acknowledging their family’s role in planning business projects. Additionally, friends and social circles in Germany contribute practically to entrepreneurship, assisting with tasks like logo creation and social media management at low costs.

Professional networks, including contacts with other entrepreneurs and involvement in programmes like Migration and Diaspora (PMD), are crucial for building international links between Colombia and Germany and for understanding business dynamics in Colombia. These networks are invaluable for advice on economic and legal aspects of running a business and for government support. Collaboration with the private sector and exchanges with other companies are highlighted as key for international market positioning. Contacts within the value chain are vital for innovation and development opportunities. Involvement in immigrant associations in Germany, which facilitate cultural and artistic exchanges, and volunteering in migrant organisations are also important for building connections and learning about supportive programmes.

3.1.5. Perceptions Towards the Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs, especially those involved in circular migration between Colombia and Germany, receive encouragement and support from family and peers. They are recognised for bringing expertise from Germany to Colombia. In Germany, they find openness and support from the local community once their capabilities are demonstrated, though they need to adapt to the direct communication style. Despite these positive experiences, challenges arise, including misconceptions about ties to German governmental agencies and managing operations while travelling frequently. Returnees to Colombia may face stigma due to heightened expectations stemming from their international experience, perceived as having had greater power and privilege.

Yet, the overall perception among Colombians in Germany is not one of stigmatisation. Their entrepreneurial ventures and educational background make them appear “interesting and exotic” to Germans, who are keen on entrepreneurship. However, some locals view them as privileged due to their opportunities to study abroad and learn new languages, occasionally leading to feelings of resentment. Entrepreneurship does not significantly alter most migrants’ status or social position. While owning a business may lead to misconceptions about wealth, it can also enhance one’s influence, improve customer relationships, and potentially better living conditions. Nevertheless, entrepreneurship is acknowledged as a double-edged sword, bringing satisfaction alongside considerable effort.

3.1.6. Influence and Support of the Country

The choice of location is pivotal for entrepreneurs, with some circular migrants moving to cities like Berlin for its conducive entrepreneurial environment, contrasting with their home cities in Colombia. Berlin is likened to Silicon Valley, celebrated for its openness to new ventures and support for innovative ideas. Germany, overall, is preferred for its higher purchasing power; stable political, economic, and social conditions; research and development opportunities; and industry connections, offering a more favourable setting for entrepreneurship compared to Colombia.

However, navigating administrative procedures in Germany, including interacting with immigration offices and visa issuance, presents challenges, especially with the risk of losing residence status affecting mobility between Germany and Colombia. In Colombia, while some governmental institutions are supportive of entrepreneurs, policy-related hurdles persist, yet there are still solid institutions providing certain guarantees for entrepreneurship, including potential subsidies or incentives.

Support for entrepreneurs varies, ranging from aid from both Colombia and Germany to none at all. The Colombian government’s support for returning entrepreneurs is perceived as lacking, particularly for technology-based ventures. Returnees prioritise relocating to Colombian cities with suitable infrastructure, connections, and investor presence, considering personal safety as well. Security concerns, including fears of violence, influence decisions to return. However, programmes like PMD offer reassurance by providing personal and professional security through contacts and alliances, indicating the presence of safe and supportive environments for entrepreneurial ventures in Colombia despite challenges.

3.1.7. Income and Quality of Life

Most interviewees describe their entrepreneurial ventures as being in a phase of experimentation and learning, acknowledging the early stages of development and viewing the initial years as an investment period. They often have to juggle other jobs to cover personal expenses, as their ventures are not yet profitable enough to sustain their living costs. Entrepreneurship is thus seen as a challenging journey, balancing the development of ideas with the practicality of financial sustainability. The aspiration to provide employment is common among the interviewees, yet actual hiring is limited due to resource constraints or the logistical complexities of managing a team across countries for circular migrants. The prospect of offering jobs is further complicated by stringent regulations in Germany, which necessitate a significant investment compared to Colombia.

Social impact is a notable aspect of many ventures, with entrepreneurs aiming to contribute positively through sustainability initiatives, job creation, support for local producers, fair pay, and donations from sales. However, the implementation of these social objectives is often contingent on the venture reaching a certain level of financial stability, indicating a pragmatic approach to blending entrepreneurship with social good.

3.2. Quantitative Analysis Results

The development of a principal component analysis (PCA) involves identifying variables that, grouped together, have a specific weight as a measure of similarity in the orientation to the sample item. In that sense, a component has the structure of Equation (1), as proposed by (Greenacre et al. 2022).

Ratio of weights per component in the variables

From Equation (1), the different weights or contributions of each variable to the explanation of the component are identified with . The weights vary from 0 to 1; in that sense, values of weights closer to 1 imply greater cohesion between the variables and will generate a better interpretation.

In this regard, each group of those that will be presented agglutinates some components, which in turn correspond to a set of variables. The labels of each component are represented in the form , where “” represents the number of the component within the group and “” represents the number of the group to which each factor is associated. In this sense, there are ten groups of variables.

Group 1 corresponds to questions related to the perception of the beneficiaries of the programme regarding the recruitment process and the key actors in that process. This group identifies enabling factors of the programme in terms of institutional support, networking, and dissemination of the programme in the different sectors of interest. The group 2 questions also bring together questions oriented towards the same indicators of group 1 but specifically consider a look at the process of orientation of the programme in terms of investment, sales, formulation, and execution of projects.

The questions of group 3 focus on temporal aspects, expectations, and demands of the programme, highlighting the existence of a factor where the importance of meeting other entrepreneurs is conceived in terms of networks or clusters of innovation. It is worth noting that these questions correspond only to the dimension of the actors’ view on the process and, more specifically, to the recruitment process. The questions in group 4 correspond mostly to the overall vision of the programme and its contribution. The interests in terms of optimisation of different types of resources, the need to increase sales and innovation, and the approach to different contacts as part of the support in the execution are highlighted. The questions of group 5 also correspond to the indicator associated with the overall vision of the programme and its contribution in terms of growth and consolidation of the company; this is a factor associated with the sustainability of the efforts of the programme in the different stages of the ventures.

The questions of group 6 conceive the life of the enterprise outside the programme, specifically in terms of sustainability presenting as factors associated with sustainability aspects such as management, technical assistance and working capital, penetration of new markets, and acquisitions of equipment. Group 7 presents its focus on the performance and survival of ventures and, more specifically, on how different threats are perceived in terms of lack of innovation, viability of the venture, and strength of the customer base.

Group 8 represents questions located in aspects of sales, export, and growth expectations. It is part of the view towards the sustainability component of the ventures. Regarding group 9, elements focused on the evolution of employment and innovative activity are identified as a key aspect in the sustainable performance of enterprises. It corresponds to participation in networks and how it contributes to innovation in marketing and processes. Group 10 considers economic variables of entrepreneurship and how you are developing with the times proposed in the programme. Key in this factor is what is proposed as a relationship between sales and costs.

Once the groups and their factors had been identified, we proceeded to determine the existence of differences in means between the different types of migration as stated by Nijenhuis et al. (2004). Tests of mean difference hypotheses with known deviation were developed, following what is presented in Equation (2).

Mean difference test

The hypotheses presented are the following:

H0:

The averages of the factors are not significantly different from each other.

H1:

The averages of the factors are significantly different from each other.

Within the framework of the above, it is intended to identify whether the behaviour of each factor is different depending on the type of migration. Table 1 identifies the migration typologies considered in this study and that were selected by virtue of their representativeness in the sample.

Table 1.

Migration typologies analysed.

For the consideration of the hypothesis values, a p-value of less than 0.05 was taken into account, thus obtaining those listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hypothesis test results for the identified factors.

According to Table 2, it is possible to identify that migrants with the intention of return value the Programme Migration and Diaspora (PMD) to a greater extent compared to those who are in circular migration, since the PMD contributes to access and optimisation of resources, both human and financial support. The latter, however, would recommend the use of the PMD more and value the growing expectations in sales, exports, and employability better than those currently in Germany. Those who intend to return recognise in the PMD the great contribution it makes to innovation and technological growth of their companies.

Another recognisable phenomenon is that migrants in circularity give higher importance to the management in the sustainability of their enterprises compared to returnees. However, the latter detect, in a clearer way, the existing threats in terms of viability and customer bases. Naturally, being rooted allows for a greater understanding of the market and its variabilities over time. Compared to returnees, circular migrants continue to place a higher value on growing expectations in sales, exports, and employability, as circularity allows a globalised view of the project.

If we compare the two groups found in Germany, those who remain there and those who intend to return, we find that those based in Germany have high expectations for overall business growth, while those who wish to return value more a prolongation of the support and the fact of participating in the PMD. Those who return require a greater sense of security because their life project will change in the near future. Entrepreneurs who remain in Germany place a higher value than returnees on expectations in sales, exports, employability, and overall growth.

The group of entrepreneurs with the intention of return have a high concern for investment orientation, management as a factor of sustainability, and growth expectations in general compared to those who are already based in Colombia, reinforcing the need to ensure the implementation and sustainability of the business.

At the level of correlations, it is identified that the perception regarding the support in the formulation of projects and formation of networks of entrepreneurs by the programme correlates directly with the perception in terms of orientation in formulation and execution of the project, as well as in the contribution of the programme in the access and optimisation of human resources.

By extracting the factors, it was possible to generate regression values with which bivariate correlation analyses are generated; for this purpose, the expression presented in Equation (3) is followed.

Bivariate correlation

From the pair of data sets compared, results are obtained with which it is possible to identify with a margin of error of 5% the level of significance that relates the change of one variable with respect to the other.

When analysing the results obtained, it is found that those beneficiaries who recommend the programme also see a positive contribution of the programme towards the development of sales and innovation in their businesses and in turn see the duration of the programme as adequate. On the other hand, those who best recommend the programme consider that more should be contributed to accessing and optimising human resources. The high direct correlation (0.717) between the recommendation of the programme (FAC2_1) and the implementation time (FAC2_10) implies that a more favorable recommendation aligns with perceptions of a more rigorous implementation process, potentially indicating greater engagement. Similarly, the robust direct relationship (0.629) between the guidance for concentrating on sales, visibility, and institutional support (FAC3_1) and sales guidance (FAC2_2) takes in account the important role of integrated marketing and sales strategies in enhancing the programme’s performance. Additionally, the direct correlation (0.613) between investment guidance (FAC1_2) and the programme’s contribution to access to contacts or execution support (FAC2_4) reinforces the notion that strong project formulation is linked to better networking and operational assistance. On the other hand, the strong inverse relationships—between sales guidance and the combined metric of sales and costs (FAC2_2 vs. FAC1_10, −0.651) and between the human resource optimisation contribution and implementation time (FAC3_4 vs. FAC2_10, −0.641)—indicate that as certain favourable factors increase, they may adversely impact cost efficiency and time management.

The training components of the programme contributed positively to the achievement of sales, investment, visibility, and support from other institutions. They also contribute to the structuring of entrepreneurship projects.

On the other hand, when identifying the perception regarding the contribution of the programme to the investment orientation, it is observed that the increase in this orientation is directly related to how the programme’s contribution is perceived in access to contacts or support in the execution. Additionally, an increase in investment support contributes to a better perception in terms of the programme’s contribution to innovation, programme monetary incentives, and technical assistance.

Those who consider that an increase in investment support is necessary consider the existence of threats in terms of lack of innovation and also perceive that the entrepreneurship environment is highly intense in terms of competitors. Additionally, those who perceived the need for increased investment support identify programme incentives, technical assistance, and working capital as key factors for sustainability. This correlates inversely with the balance between sales and costs. Additionally, the perception regarding the performance of the programme in terms of orientation in the formulation and execution of the project is directly correlated with the perception regarding the development times of the programme, the contribution of the programme to sales and innovation, and the perception of the level of contribution of the programme in the innovation and technological growth of the company.

Results in Relation to Networking

The analysis reveals a nuanced relationship between entrepreneurs’ engagement with peer networks and their perception of a support programme’s value in the creation, growth, and consolidation of their businesses. Specifically, entrepreneurs who prioritise strengthening connections with their peers tend to perceive the programme’s contributions as less significant. This suggests a need for the programme to facilitate networking opportunities among entrepreneurs, enhancing the training process and fostering alliances that support venture sustainability. It is important for the programme to integrate seamlessly with the entrepreneurial ecosystem, avoiding being viewed as merely an adjunct or the networks as an extension of the programme but rather as complementary components.

Beneficiaries acknowledge the programme’s significant role in various business development aspects, including employability and export potential. However, they also note the substantial time investment required to implement these components effectively. Furthermore, management practices related to sustainability show a positive correlation with growth expectations and an inverse correlation with perceived threats to viability and customer base. The importance of innovation in commercialisation is linked to the value placed on technical assistance and capital as sustainability factors, alongside expectations for operating as an independent or small business.

Equipment acquisitions and understanding regulations as sustainability factors are positively associated with the importance of network involvement. Conversely, the perception of threats to feasibility and customer base negatively correlates with the time spent on implementation and programme participation. These findings underscore the complex interplay between networking, programme participation, and entrepreneurial success factors, suggesting that fostering a cohesive and integrated approach can enhance the impact of support programmes on venture viability and growth.

4. Discussion

How should one understand return? As a failure experience, as part of a more dynamic process, or as a success of the migratory experience (Maldonado Valera et al. 2018)? According to the interviewees’ accounts, the idea of return is marked by the desire to contribute to Colombia through entrepreneurship. Return is thus understood as a dynamic process where migration experiences and the knowledge acquired in the different mobility phases intersect, thus allowing recognition of commercial opportunities, market trends, internationalisation, and network possibilities.

Regarding the transnational perspective to return studies, our analysis shows that the interviewees consider a diversity of destinations (cf. Maldonado Valera et al. 2018). There are those who think about returning with entrepreneurship to Colombia but to different cities depending on family ties or entrepreneurship possibilities. There is, therefore, no fixed point of return. There are others who hope to maintain the transnational link between Germany and Colombia without losing residence in Germany by maintaining a circular migration with sporadic returns. In other cases, there are also those who intend to establish commercial connections with different countries in Latin America, which can be considered a multilocal perspective (cf. Cavalcanti and Parella 2013).

Following the idea of the situations to which they return, they are crossed by family factors, adequate commercial relations, and, often, the country’s political, economic, and social conditions to establish their ventures. Thus, a process is outlined that requires planning and increasing both personal and entrepreneurial security before returning.

This process is reflected in the fact that some interviewees remain in a situation of permanent circularity or those who do return but do not rule out re-emigration. In this way, migration is polyhedral (cf. Cavalcanti and Parella 2013), that is, multidirectional. This connects with Riaño’s (2022) notion of “transmobilities”, which views return migration “as a continuous rather than a completed movement across the globe”. It also connects with Cassarino’s (2004) idea that the “migratory fact continues”. For none of the interviewees was return migration a completely definitive fact, i.e., intending to stay in Colombia, as the multiple experiences they acquired in the places they lived gave them differential capitals that benefitted their enterprises and facilitated their reintegration.

The relationships and exchanges established by Colombians in their migratory processes show that their “sense of belonging” with Colombia does not disappear (cf. Cassarino 2004). Most of them wish to give something back to Colombia through entrepreneurship. Beyond receiving support for development from the MDP, there is the intention to contribute to the country’s improvement. In this way, it is possible to affirm Cassarino’s idea that most entrepreneurs prepare “their own reintegration” or are in the process of permanent preparation. We can affirm that wishing to contribute to Colombia’s development is present among all entrepreneurs.

It is evident that some entrepreneurs recognise that knowing Germany’s culture and language and learning how institutions function are key elements of social integration. As such, they can manage and contrast different social and cultural environments, which relates to Cassarino’s (2004) idea of “dual identities”, that is, they seek adaptation in Germany and recognise their status as migrants but do not leave aside the experience of life in Colombia. Also, when they return, they do not abandon the experience acquired in Germany, including the experiences of transit in the case of circular migrants. The “taking advantage” of the experiences of dual identities is reflected in cases where having been or being in Germany can mean a quality stamp for business ventures. Being a migrant with an entrepreneurial vocation can be a favourable factor in Germany, as German society appreciates the intention to progress.

As a subjective perception of the homeland and self-identification with the place of origin, Colombia is seen as a country of opportunities where ideas can be undertaken and developed despite conflict situations. In most cases, the notion of being proud or ashamed of Colombia does not appear. Rather, it is perceived as a place where there is much to do and human capabilities are in place. There is an optimistic vision of the country, since almost all entrepreneurs have reaffirmed that grounding a business can be plausible either from Germany or as a reintegration strategy.

As for social networks, return migrants have “tangible and intangible resources” (Cassarino 2004). The interviewees state that most of their resources go to the “intention” of undertaking a business and returning or maintaining the link with Colombia or other destinations. This intention is something immaterial that connects multiple spatial contexts, as shown by Riaño (2022). It also corresponds to Brzozowski’s (2017) idea of entrepreneurship as a “desirable career”, which results from a series of attitudes, emotions, and ways of thinking that are typical of an entrepreneur. This gives him/her the capacity for persistence and adaptation. Other intangible resources, or social investments, go through the support of family or friends, which maintains the enthusiasm to undertake and return. This conclusion is in line with Riaño (2013, 2022), who finds in her studies on the reintegration of Ecuadorian returnees and Colombian returnees with basic education that the family is the most important capital they possess, a particularly valuable resource because they hardly receive any support from the Ecuadorian and Colombian governments.

Some of the most relevant intangible resources for entrepreneurs are information regarding regulations or programmes to support entrepreneurship and the permanent accompaniment of their ventures. Intangible resources are also the economic support received from the PMD, which allows them to advance in maturing initial ideas or their economic base, either through seed capital to acquire raw materials or technological equipment in Colombia. Thus, for the interviewees, the participation and development of networks of entrepreneurs is a key aspect of innovation.

Knowing various investment locations worldwide represents a valuable tangible resource for the interviewees. Various locations in Germany, Colombia, and other places in Latin America open up possibilities. As Riaño (2013, 2022) shows in her studies, geographic location is key to the success of entrepreneurship by returnees: while peripheral locations make entrepreneurship very difficult, central locations such as major cities offer many more possibilities, and it is often there that the few successful studied entrepreneurs live. This aspect has not been sufficiently considered in migrant reintegration studies and programmes.

Regarding interpersonal relationships, Cassarino (2004) argues that success in return depends on past migratory experiences or long-term relationships. The studied entrepreneurs reveal the great value of exchanging with networks of entrepreneurs as a learning process and as inspiration for their ventures. Links with colleagues in the same profession, friends in Colombia (including schoolmates), and family contribute to maturing their ideas and generating contacts, increasing their clientele. This is also connected with Brzozowski’s (2017) idea that strengthening entrepreneurship depends on the disposition of the communities of origin and destination.

Maintaining and strengthening networks is key to generating plans and work alliances, which allow for the creation of more robust commercial strategies. The interviewees have various social capitals, which in many cases complement each other, that can be typified from personal and professional contacts to institutional. Something that would strengthen the training aspects of the programme is the inclusion of training-based or collaborative networks where the entrepreneurs themselves are trainers.

We thus observe entrepreneurs as a “rational branched set” (Cassarino 2004), establishing relationships of support and solidarity with their families and friends on the one hand and among the entrepreneurs themselves on the other. This is supported by the PMD, where spaces for recognition and learning exist, as well as networks with suppliers or institutions that facilitate entrepreneurship and networks with specific associations or sectors, which sometimes have a transnational character (Riaño and Aliaga Sáez 2024). We also observe that the more actors involved in entrepreneurship, the less the returnees lose the spirit of continuing with their ventures.

As for the levels of preparedness for the pre- or post-return, we observe that the interviewees go through different phases, which could be classified as (a) those who are still in search of a livelihood in Germany and therefore cannot be autonomous but depend on a job contract; (b) those who have been able to achieve income through entrepreneurship, have returned, and have support in Colombia to launch their initiative; (c) those that still live in Germany but already generate enough resources to sustain themselves; and (d) those who do not yet have enough resources to start their venture fully and are in the process of planning. Overall, the fewer economic resources obtained from the venture, the greater the needs in Colombia, and thus the possibility of returning to settle in Colombia becomes unlikely.

Limited information about supportive laws or programmes for entrepreneurship hinders the possibility of returning to Colombia. Concerns about insecurity and uncertainty also affect the decision to return. However, connections with professional networks, potential customers, and suppliers, as well as establishing strategic alliances, increase perceptions of security among returnees. While all interviewees express a desire to return, readiness varies, especially for those already back in Colombia. They navigate economic changes, maintain relations with Germany, seek financing, and address personal security concerns. Despite the resilience, commitment, creativity, personal skills, and family support demonstrated by interviewed entrepreneurs, most encounter ongoing challenges, as noted by Riaño (2022).

Returnees’ objectives as potential development agents (Riaño 2022) depend on their ventures’ sustainability. This potential may be limited by conditions affecting the country, mainly at the government level and economic stability. However, whether they are away or back in the country, the permanent search for supporting their ventures is present. Present also are the challenges of how to transfer and implement technologies to Colombia, how to exchange knowledge with experts and other entrepreneurs, searching for places in Colombia where potential can be recognised, and seeking ways for the government to support the initiative and generate conditions that should be improved to increase the effectiveness of their projects (cf. Gubert and Nordman 2011). At this point, it is necessary to bring in Riaño’s idea that although sustainable reintegration depends on whether there is economic independence through entrepreneurship, which few of the interviewees have achieved, at the same time, it cannot solely be measured in economic terms. She proposes an integrated understanding of reintegration as “the process through which a returnee attains the necessary conditions in which to use their capacities and resources to ensure that their fundamental, existential, and security needs are met”.

Further, the group of interviewees does not represent a single “market niche” (Brzozowski 2017), which could be conceived with ethnic characteristics or related to a specific field, but has a wide range of ideas and different types of interconnections between Colombia and Germany. While it is true that most seek to generate profits, which allow autonomy and economic sustainability, it is also true that there is no clarity regarding the calculations of risk and ideal working conditions in the face of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is mainly understood as a form of employment that can create small or medium businesses and contribute to generating jobs. There is a projection in time that, sometimes, is organised in terms of the stages of meeting goals. However, there is talk about an ideal future where it is expected to achieve the objective of maturing the initiative.

In general, we can say that the Colombians interviewed seek to generate ventures anchored to different types of economies, but mainly two features are observed. Interviewees expect to generate customer networks with their co-nationals in Germany or Colombia and to develop business ideas inserted in international markets. In this sense, the intention is not to be included in marginal markets left by German nationals but rather to generate processes of innovation and technology transfer to Colombia. Hence, the contribution and responsibility of the PMD training includes several factors that are of special interest to the entrepreneurs participating: integral training based on collaborative networks, orientation and training in commercial aspects, contributions of the programme in terms of resources, contribution of the programme to sustainability, contribution of the programme to business growth, identification and treatment of threats to entrepreneurship, and, finally, recognition and expansion of growth expectations highly related to participation in networks as a key element of innovation.

5. Conclusions

The objective of this article has been to analyse, through a mixed-methods approach, the experiences, strategies, and expectations of twenty-seven Colombians who have returned, or intend to return, from Germany to Colombia and who have benefited from the logistical and financial support of the Programme Migration and Diaspora (PMD). This programme is implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). This study presents limitations regarding its generalisation to the Colombian diaspora in Germany, insofar as accessing a broader sample is hindered by the specific conditions of entrepreneurial ventures and their associated subregistrations. However, it is important to consider that the sample is representative and generalisable for the different programmes that support entrepreneurial ventures among Colombians migrating to Germany. It is necessary to conduct further research with a larger and significant sample of returning migrant entrepreneurs.

The hypothesis testing reveals that significant positive correlations are observed where circular mobility (MC) and migrant at destination (MD) typologies tend to experience favourable outcomes, such as enhanced programme recommendations, increased innovation, and growth in sales, exports, and employability. These positive associations are about how these groups benefit from adaptive strategies and opportunities for professional and technological growth. On the other hand, significant negative correlations predominantly appear in contexts related to re-emigrated individuals (RE) and those with a return intention (IR) in areas concerning management sustainability, investment guidance, and overall viability. This implies that while certain migration pathways foster advantageous experiences and outcomes, others may face challenges that could potentially undermine their long-term success, indicating a need for tailored interventions that address these specific vulnerabilities.

Together with Nedelkoska et al. (2021), we would like to give greater visibility to those Colombian entrepreneurs abroad, since it helps to better position their ventures and generates inspiration and empathy among the diaspora. The strategy developed by the government of Colombia was the implementation of Law 1999 of 2019 that declares 10th October as Colombian Migrant Day, with which recognition is granted to Colombian migrants, generating greater positioning of the government and its programmes among the population abroad and strengthening ties with members of the diaspora. However, there is a serious problem of under-registration of Colombians abroad, among other things, because consular registration is not mandatory.

The law is not explicit about incentivising the diaspora to invest in Colombia. No foreign direct investment regulation mentions nationals living abroad. In addition, a certain gap is perceived in the regulations in this regard, because although a member of the diaspora can be interpreted as a non-resident and there is the principle of equal treatment (article 2.17.2.2.1.1. of Decree 1068 of 2015, Presidencia de la República de Colombia 2015), the regulations of resources as an entrepreneurship fund (Agreement 10 of 2019) only contemplates “returnees” and promotes only productive projects of those who return to the country. This completely rules out the possibility of supporting proposals that are led by members of the diaspora with their own resources from abroad. We show that it is possible to articulate the Colombian diaspora in the development of business initiatives, the generation of employment, and an exchange of knowledge that impacts the productive environment.

A field to highlight as an important source of investment from the diaspora is the “potential that would have the creation of programmes that encourage the investment of remittances in truly productive programmes, generating jobs and added value for the nation” (Santamaría 2012, p. 148). This would represent a very powerful source of project financing from the diaspora and the possibility of creating funds from angel investors or venture with sources of non-resident nationals.

Government programmes can play a fundamental role in strengthening the entrepreneurship of returnees, those who intend to return, or those who remain in circular mobility. The important concept here is that transnational entrepreneurship pays off state investment when it results in creating jobs, generating reinvestment and greater economic dynamics.

It would be interesting to open calls for transnational entrepreneurship proposals that impact Colombia positively, and a first pilot project could be articulated with PMD. London is an interesting case (Ponce 2013), because there have been several working boards and committees for some time: business board and connection and opportunities board, all led by the Colombian diaspora. These boards are framed within the policy represented in Law 1465 of 2011 and Law 2136 of 2021. All the aspects that this new law opens are promising paths for the entrepreneurship of returnees and the diaspora, which, without a doubt, will require the accompaniment and observation of civil society and academia.

Colombia has a robust set of rules supporting the institutional system of entrepreneurship and offering concrete mechanisms to aid the productive projects of returning entrepreneurs. However, the lack of clarity and promotion of these mechanisms limits their benefits and excludes non-resident Colombians with significant investment potential. Many Colombians abroad are unaware of programmes, tax benefits, incentives, and trade agreements that could support their ventures (Procolombia 2020). Nevertheless, the interviewed Colombian entrepreneurs exhibit strong motivation for entrepreneurship, fuelled by belief in their creative processes and a commitment to expanding their networks and knowledge. This group of migrants holds valuable potential for Colombia, Germany, and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.-S., D.A.G.-A., Y.R. and D.B.-B.; methodology, F.A.-S., D.A.G.-A. and J.S.-A.; software, J.S.-A., D.A.G.-A. and F.A.-S.; validation, D.B.-B. and Y.R.; formal analysis, F.A.-S. and D.A.G.-A.; investigation, J.S.-A. and D.A.G.-A.; resources, D.B.-B.; data curation, F.A.-S., D.A.G.-A. and J.S.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.-S., D.A.G.-A. and Y.R.; writing—review and editing, Y.R., D.B.-B. and J.S.-A.; visualization, J.S.-A.; supervision, D.B.-B.; project administration, D.B.-B.; funding acquisition, D.B.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

German Cooperation; German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research has been approved by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH Ethics Committee through the Programme Migration & Diaspora 23.2163.6-019.00, with approval granted on 1 September 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Batista, Catia, Tara McIndoe-Calder, and Pedro C. Vicente. 2017. Return Migration, Self-selection and Entrepreneurship. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 79: 797–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Richard, and Adriana Castaldo. 2009. Return migration and entrepreneurship in Ghana and Côte D’Ivoire: The role of capital transfers. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 100: 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMZ (Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung). 2020. Entwicklungspolitik 2030: Neue Herausforderungen—Neue Antworten BMZ Strategiepapier (Development Policy 2030: New Challenges—New Answers). Available online: https://www.bmz.de/resource/blob/23562/a0cbe466baa3e606f55ac02affa53be4/strategiepapier455-06-2018-data.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Bolzani, Daniela. 2023. Assisted to Leave and Become Entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurial Investment by Assisted Returnee Migrants. Acaemy of Management Discoveries 9: 261–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, Jan. 2017. Immigrant Entrepreneurship and Economic Adaptation: A Critical Analysis. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review 5: 159–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancillería de Colombia. 2023a. Comisión Intersectorial para el Retorno Consolidado Estadístico 2023-11. Available online: https://www.colombianosune.com/sites/default/files/imce/RUR_Estad%C3%ADsticas2023.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Cancillería de Colombia. 2023b. Programa Colombia Nos Une Entrega Capital Semilla a 25 Colombianos que Retornaron de Venezuela; Bogota: Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores. Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/newsroom/news/programa-colombia-nos-une-entrega-capital-semilla-25-colombianos-retornaron-venezuela (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Cancillería de Colombia. 2023c. Programa Colombia Nos Une y Cancillería Certificó a Emprendedores, 35 Colombianos Retornados; Bogota: Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores. Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/newsroom/news/programa-colombia-nos-une-cancilleria-certifico-emprendedores-35-colombianos (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. 2004. Theorizing return migration: The conceptual approach to return Migrants revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies (IJMS) 6: 253–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti, Leonardo, and Sònia Parella. 2013. The return from a transnational perspective. REMHU Revista Interdisciplinar Da Mobilidade Humana 21: 9–20. Available online: https://remhu.csem.org.br/index.php/remhu/article/view/401 (accessed on 17 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [DANE]. 2020. Estudio de Caracterización de los Usuarios que Atiende Cada Uno de los Consulados de Colombia en el Exterior. Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/FOTOS2020/estudio_de_caracterizacion_de_los_usuarios_que_atiende_cada_uno_de_los_consulados_de_colombia_en_el_exterior._version_boton_de_transparencia_27nov20.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Departamento Nacional de Planeación [DNP]. 2023. Colombia, Potencia Mundial de la Vida. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2022–2026. Departamento Nacional de Planeación, Bogota, Colombia. Available online: https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Prensa/Publicaciones/plan-nacional-de-desarrollo-2022-2026-colombia-potencia-mundial-de-la-vida.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Filatotchev, Igor, Xiaohui Liu, Jiangyong Lu, and Mike Wright. 2011. Knowledge spillovers through human mobility across national borders: Evidence from Zhongguancun Science Park in China. Research Policy 40: 453–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Cooperation Agreement. 2012. Convenio Cooperación Financiera con Alemania: Suscrito por Ambas Partes el 19 de Julio del 2012. Colombia: Financial Cooperation Agreement. [Google Scholar]

- General Agreement on Technical Cooperation. 1998. Convenio General de Cooperación Técnica Suscrito el 26 de Mayo de 1998. Colombia: General Agreement on Technical Cooperation. [Google Scholar]

- GIZ. 2024. Alemania y Colombia comparten más de 50 años de cooperación. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/29848.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit). 2023. Combining Business and Development. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/workingwithgiz/25-years-developpp.html (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Greenacre, Michael, Patrick J. F. Groenen, Trevor Hastie, Alfonso Iodice d’Enza, Angelos Markos, and Elena Tuzhilina. 2022. Principal component analysis. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubert, Flore, and Christophe J. Nordman. 2011. Return Migration and Small Enterprise Development in the Maghreb. Diaspora for Development in Africa 3: 103–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Stephen, Aileen Ionescu-Somers, Alicia Coduras, Maribel Guerrero, Muhammad Azam Roomi, Niels Bosma, Sreevas Sahasranamam, and Jeffrey Shay. 2022. Global entrepreneurship monitor 2021/2022 global report: Opportunity amid disruption. Paper presented at Expo 2020 Dubai, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, October 1–March 31. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 26.0) [Software]. New York: IBM Corp. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Towards an Integrated Approach to Reintegration in the Context of Return. Available online: https://www.iom.int/es/resources/hacia-un-enfoque-integrado-de-la-reintegracion-en-el-contexto-del-retorno (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019a. IOM Glossary on Migration. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml-34-glossary-es.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019b. World Migration Report 2020. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/informe-sobre-las-migraciones-en-el-mundo-2020 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Kenney, Martin, Dan Breznitz, and Michael Murphree. 2013. Coming back home after the sun rises: Returnee entrepreneurs and growth of high tech industries. Research Policy 42: 319–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado Valera, Carlos, Jorge Martínez Pizarro, and Rodrigo Martínez. 2018. Social Protection and Migration. A Look from Vulnerabilities Throughout the Migration Cycle and People’s Lives. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/44021-proteccion-social-migracion-mirada-vulnerabilidades-lo-largo-ciclo-la-migracion (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- McCormick, Barry, and Jackline Wahba. 2001. Overseas work experience, savings and entrepreneurship amongst return migrants to LDCs. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 48: 164–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, Esi Akyere. 2016. Involuntary Return Migration and Reintegration. The Case of Ghanaian Migrant Workers from Lybia. Journal of International Migration and Integration 17: 303–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]