Abstract

Introduction: The aim of this study is to explore variables relating to teacher–student relationships, and their association with the detection of child maltreatment in secondary schools (12–18 age range), given that child and adolescent abuse is under revealed and underreported, and teachers play an important role in identifying and detecting it. Method: 662 teachers from secondary schools from different autonomous communities in Spain answered a self-administrated questionnaire. Results: This study revealed that while theoretical knowledge of the issue goes hand-in-hand with a higher self-reported ability to recognize cases among students, the same does not hold true of the teachers’ real detection capacity. Nonetheless, a relationship of trust with students and addressing child maltreatment in the classroom contributes to a better real detection capacity by teachers, relating this information to the possible existence of a teacher–student alliance. Discussion: We propose a trust-constructed relationship between both agents, named the teacher–student alliance. Prospective: These results point to the need for further research into the association and characteristics of teacher–student alliances on the identification in schools of cases of child maltreatment.

1. Introduction

Detecting and addressing child maltreatment in Spanish classrooms are a fundamental challenge for schools and for the protection of students (Benítez et al. 2005).

UNICEF (2024a) estimates that 6 in 10 children—400 million children all over the world—under 5 years of age regularly suffer physical punishment (330 million of them) and/or psychological violence at home by caregivers. In addition, 20% women (650 million) and 14% men report having been sexually abused during childhood (UNICEF 2024b). In Spain, 21,521 cases of child maltreatment were reported in 2021, with an observed increase in recent years (Fierro Monti 2021; Ministerio de Sanidad 2024). What is more, most child maltreatment cases go unreported, and they remain hidden (Finkelhor 1984). Nonetheless, approximately 25% of all minors in Spain suffer from maltreatment (cipher just considering maltreatment within the family), with fewer than 10% of these cases being reported (Del Moral Blasco 2019).

1.1. Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment is conceptualized in this study aligned with the following definition made by The World Health Organization:

Child maltreatment is the abuse and neglect that occurs to children under 18 years of age. It includes all types of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect, negligence and commercial or other exploitation, which results in actual or potential harm to the child’s health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power (WHO 2025).

Among the consequences of child maltreatment are disorders in affection and attachment relationships, poor academic performance, worse cognitive development, emotional problems… and, especially in adolescence, drug use, aggressive behavior problems, self-harming and suicidal behaviors, etc. (Cantón Duarte and Cortés Arboleda 2007; WHO 2022).

Usually, maltreated children are nurtured within a family style called neglectful–abuser, where insecure attachment styles are generated. For this reason, minors develop a strong insecurity when establishing relationships with other people, due to the harmful foundation they have had (Crittenden and Ainsworth 1989). Moreover, Finkelhor and Browne’s model, which serves as a framework for explaining the consequences of child abuse, shows that victims experience a sense of betrayal, leading to feelings of disillusionment and mistrust. Finkelhor and Browne’s (1985) Traumagenic Dynamics Model conceptualizes child abuse as a process that generates four primary trauma-related outcomes: traumatic sexualization, betrayal, powerlessness, and stigmatization. Traumatic sexualization refers to the shaping of a child’s sexuality in inappropriate ways; betrayal involves the child’s realization that someone on whom they depended on has caused them harm; powerlessness reflects the child’s sense of helplessness and loss of control; and stigmatization refers to the feelings of shame and guilt associated with the abuse. In this study, particular attention is paid to betrayal and powerlessness, as these dynamics are especially relevant for understanding the difficulties maltreated students may face in trusting and disclosing abuse to adults, including teachers. Furthermore, having been betrayed, generally by a reference figure, and on whom they are often dependent due to their age, generates a strong distrust of other people in subsequent situations. Added to this, the helplessness of which they are victims (as their volition and sense of efficacy are undermined) causes their social skills to greatly diminish (Finkelhor 1984; Finkelhor and Baron 1986). As a result, it is crucial to forge a relationship of trust with individuals in order to identify situations of abuse (Díaz-Aguado 2001; Fierro Monti 2021).

It is therefore shocking that 45% of the people to whom the minor finally manages to ask for help do nothing (López Sánchez and Campo Sánchez 2006), reinforcing this lack of trust in the persons of reference for the minor, and leading to deep pain, confusion, and hopelessness. Consequently, it is necessary to act against child maltreatment and lack of response; it is the responsibility of the entire society and especially of those closest to the minor, such as their teachers.

Given these data, it is essential to gain a better insight into the identification and notification of child maltreatment. Environments close to the victim and the people who form part of them—such as schools and teachers—play a particularly important role in the detection of signs of these abusive situations (Monjas 1998; WHO 2017).

1.2. The Importance of Teachers in the Child Maltreatment Detection Process

Teachers are key agents in the identification and detection of child maltreatment, given their educational role and direct contact with students and their families (Díaz-Aguado 2001; Monjas 1998). We propose that teachers, as professionals and adults, be able to understand and identify what is happening to the child/adolescent. Indeed, the negative school consequences of child maltreatment have been reported by numerous researchers (McGuire and Jackson 2018; Panlilio et al. 2018; Slade and Wissow 2017), being that many of these indicators are therefore symptoms that could be evident to teachers, unlike other signs that are more difficult to identify by other people (Mathews et al. 2016).

Nonetheless, teachers are far below reporting the child maltreatment levels that exist in the reality of their students, also in Spain (Vila et al. 2019). In countries such as the United States, teachers are considered “mandated reporters”-that is, professionals who are legally required to report suspected cases of child maltreatment, a mandate that has been in place since 1963 (McTavish et al. 2017). In this context, teachers have been identified as the social agents who reported the highest number of child maltreatment cases in 2005 (VanBergeijk and Sarmiento 2006). This legislation was expanded to other countries, and in Australia, the reported cases have multiplied by 3.7 since the entry into force of this legislation (Mathews et al. 2016), although improvements can be applied to the guide for teachers and other required reporters for its better functioning (VanBergeijk and Sarmiento 2006).

In Spain, this role is not legislated, but we wish to highlight the broad legal support that supports teachers, for their mandatory notification in case of suspicion: the Spanish Constitution, in its article 39, or Law 1/1996, on the Legal Protection of Minors. In addition, numerous technical and legal frameworks of notification systems and protocols can be found, developed by each Autonomous Community, with the aim of reforming and updating national provisions.

In any case, there are always multiple views regarding how teachers should report child maltreatment and how it relates to them (VanBergeijk and Sarmiento 2006).

Despite this fact, there is a substantial difference in the theoretical knowledge that teachers hold on the subject of child maltreatment, with a general deficiency in this regard (Prous Trigo 2021; Sainz et al. 2020; Vila et al. 2019). This shortcoming also extends to teachers’ knowledge of the procedures to follow when initial signs of child maltreatment are identified (Linares 2022). Both these circumstances have led to calls for more specific teacher training on how to deal with these situations, given its confirmed influence on the detection of maltreatment (Mathews et al. 2016).

At the same time, there are also differences in how tutors address the subject of child maltreatment with students. These differences range from the time dedicated to working on this issue to the way in which it is presented to students, with some efforts to approach the issue in a rigorous way in schools (Benítez et al. 2005; McGuire and Jackson 2018; Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad 2014).

In addition to the above, teachers’ perceptions of their own professional performance are an important factor in predicting their motivation and learning curve, serving as a mediator between thought and behaviors (Ministerio de Sanidad 2024). Hence, by analyzing these perceptions, an important insight can be gained into teachers’ visions of how to tackle certain situations in schools.

Thus, we believe that it is important to investigate the association of the above factors on child maltreatment detection in schools, paying particular attention to certain characteristics of teachers and the formation of a teacher–student alliance so that the findings can serve as a guide in providing adequate means for teachers to detect possible cases of child maltreatment.

1.3. Teacher–Student Alliance Proposed

In this context, teacher–student relationships are an essential factor in identifying and mitigating situations of maltreatment, when going through a decisive rapport that goes beyond the mere transmission of knowledge. Going on in this idea, we named it the “teacher–student alliance” (as therapeutic alliance used by psychologists), which is very influential in efficient results in psychotherapy (Safran and Muran 2000).

In this study, the teacher–student alliance is proposed as a space of trust, sensitivity, and commitment, where students feel safe enough to share their experiences and where teachers can contribute to the development of their students. In cases of child/adolescent maltreatment, teachers with a good teacher–student alliance could help to identify and notify the maltreatment of their students.

This research study delves into the intricate web of relationships that are formed in school environments, emphasizing the crucial importance of close ties between teachers and students as a determining factor in the early detection of signs of child maltreatment. As trusted figures and guides, teachers play a key role in creating an environment where students feel secure enough to express their concerns and experiences (Puerta Climent and Colinas Fernández 2007).

Due to the underreporting of child maltreatment, this kind of relationship must be reinforced in order to break the silence typical of these situations (Del Moral Blasco 2019).

Hence, it is crucial to explore which specific teacher characteristics influence the capacity to detect child maltreatment. An analysis of differences in how educators address the issue in the classroom, combined with more specific training to improve their theoretical knowledge, can also help substantially to improve procedural guidelines and interventions aimed at combatting such an important problem in a student’s development.

1.4. Context and Legislative Framework

This study is aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); specifically Goal 3, Good Health and Well-being, and Goal 4, Quality Education, as part of the 2030 Agenda (Instituto Nacional de Estadística n.d.). It addresses the role of certain school-related characteristics in improving the health and well-being of students in cases of child maltreatment.

It is also related to the child protection strategies developed by the European Commission (2024a, 2024b) that address the issue of child maltreatment, as a key factor for the healthy lives of children.

Different international organizations have also faced child maltreatment from different perspectives, proposing action protocols and standards that analyze situations of maltreatment from a global approach (Keeping Children Safe 2020; ONU 2006).

Furthermore, this study aligns with Article 19 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which requires States Parties to take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social, and educational measures to protect children from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s), or any other person who has the care of the child (UNICEF Comité Español 2006). In Spain, this obligation is reflected in Article 12 of Law 26/2015, which explicitly mandates that any person, and especially professionals in close contact with minors, must report suspected cases of child maltreatment to the competent authorities.

In relation to the territorial scope of the sample used in the present study, the 2020 Spanish Education Act (the LOMLOE according to its acronym) (European Commission 2024a), which amends Article 1(k) of the previous act, explicitly states that students must be assisted in “recognizing all forms of maltreatment, sexual abuse, violence, or discrimination and in reacting to it” (p. 14). This amendment highlights the relevance and gravity of the problem. In response to international demands and the requirements of current Spanish legislation in the field of education, this research study addresses child maltreatment from the perspective of schools, emphasizing the role of teachers as a key agent in detection and reporting processes.

In addition to the contributions of local and international entities, the studies carried out by specialists in this field also provide concreteness and a guide to confront child maltreatment (Solís de Ovando 2021).

2. Materials and Methods

This is a descriptive qualitative research study since it aims to identify the reality of a certain situation and to gain an understanding of the phenomenon in question. Teachers are used as the direct source of the analyzed data, identifying and describing, in qualitative terms, the different ways in which they experience, understand, and perceive the phenomenon of child maltreatment in their professional role. Thus, the underlying methodology is a phenomenographic one (Prous Trigo 2021).

To ensure the quality and accuracy of the results obtained, this study complies with established criteria governing the rigor of qualitative research methodologies. Associations between variables were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-square tests (α = 0.05) to determine statistical significance.

2.1. Sample

The target population consisted of teachers working in secondary schools (12–18 age range) in different autonomous communities in Spain (Europe). This study had a sample size of n = 662. Non-probability sampling was used, gathering all the school contact details from the official websites of various autonomous communities. Table 1 outlines the main characteristics of the schools in which the teachers who participated in this study work.

Table 1.

Schools’ characteristics regarding legal nature and location.

2.2. Instrument

A self-administered questionnaire was made available through Google Forms, distributed via e-mail to the entire state, private, and subsidized secondary schools in the autonomous communities of Madrid, Andalusia, Extremadura, Castilla y León, Catalonia, and the Canary Islands. All the results reported by the schools were considered for this study.

In addition, this questionnaire was validated by 5 university professors and 5 independent secondary teachers who appreciate a very clear and easy-to-understand questionnaire, and also considered appropriate questions according to the objective of this research.

The variables that are analyzed in this study include theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment, the capacity and preparedness of teachers to address the issue, and their opinion of teacher–student relations (teacher–student alliances) in the detection of child maltreatment. The questionnaire is divided into three sections of questions (18 questions in total): the first section focuses on sociodemographic aspects (questions 1 to 4); the second section centers on theoretical knowledge, and the reporting and detection of child maltreatment (questions 5 to 12); and the final section explores the capacity and preparedness of teachers to address the subject with students (questions 13 to 18).

Theoretical knowledge was addressed not by self-identification, but questioning about real data and documents used in its notification. Validated assessment tools were used in the development of the questions asked in the first part, such as RUMI (Unified Register of Suspected Cases of Child Maltreatment) developed by the Observatory of Childhood and the Spanish Ministry for Health, Consumer Affairs, and Social Welfare. The RUMI, established under Article 22 of Law 26/2015, serves as a unified information system shared by all Spanish autonomous communities, providing comprehensive data on reported cases of child maltreatment. In this study, RUMI was used as a validation tool by offering baseline figures for maltreatment notifications at the regional level, allowing for the assessment of teachers’ awareness of official reporting procedures and their familiarity with institutional mechanisms for child protection. This tool provides data on all maltreatment notifications (both confirmed and unconfirmed) that occur in Spain, and, for this study, the data have been used according to their distribution by autonomous communities. In addition to RUMI, several guides from different autonomous communities were also drawn upon with guidelines for action in suspected cases of child maltreatment detected in schools; i.e., from Madrid, Andalusia, Extremadura, Castilla y León, Catalonia, and the Canary Islands (Autonomous Community of Madrid 2021; Department of Employment and Social Affairs 2004; Panlilio et al. 2018; Prous Trigo 2021; Puerta Climent and Colinas Fernández 2007).

2.3. Data Analysis and Processing

To make the necessary calculations, the IBM statistical analysis program SPSS Statistics 25.0 was used. Pearson’s chi-square test (with a minimum significance level of 0.05) was used to determine the variables that displayed significant relationships.

3. Results

The data from the questionnaires submitted by the teachers were analyzed from four perspectives: the teachers’ theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment; whether they addressed the issue in the classroom; their self-reported capacity to detect child maltreatment and actual detection; and their perspectives of teacher–student alliances.

3.1. Teachers’ Theoretical Knowledge of Child Maltreatment

When the teachers were asked to identify the form in their autonomous community used to report suspected cases of child maltreatment detected in school, only 30% of them recognized it at the start of the questionnaire (Table 2). They were also asked whether they knew the number of child maltreatment cases registered in the child maltreatment reporting system for their autonomous community, also known as RUMI (Unified Register of Child Maltreatment Cases). It was observed that only 22% of the teachers could identify or were aware of this number (Table 2).

Table 2.

Teachers’ knowledge of the report form and reported suspected cases.

As for the age range at which child maltreatment typically occurs, only 29% of the teachers answered correctly (Table 3). The survey went on to ask about the classification given by the World Health Organization (WHO), which encompasses a wide range of typologies. A high percentage of teachers, close to 80%, know about this classification. The study also sought to investigate whether teachers considered bullying and cyberbullying to be early forms of child maltreatment, with 79% responding affirmatively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Teachers’ theoretical knowledge of aspects of child maltreatment.

Finally, it must be noted that only 4% (n = 22) of the teaching staff correctly answered all the questions regarding their theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment and the reporting of suspected cases (questions 6, 7, 8, and 9 of the questionnaire). It is not surprising that 74% of the teachers interviewed (490 teachers) believe that improvements must be made to boost their knowledge of the issue.

3.2. Addressing Child Maltreatment in the Classroom

From the answers to question 17, it was observed that only 29.9% of the interviewed teachers (n = 198) actively address the subject of child maltreatment in the classroom. This low percentage highlights the need to explore the reason why, as well as the potential implications for the well-being of students.

Upon closer analysis of the characteristics of those teachers who address the subject of CA in the classroom, a significant association with teacher–student trust was found (chi-square = 54.616, df = 6, p = 0.000; Table 4), showing that this group of teachers tends to have a higher relationship of trust with their students in comparison with teachers who do not tackle the issue.

Table 4.

The association between teacher–student trust and addressing child maltreatment in the classroom.

The main reasons put forward by the teachers for the low child maltreatment reporting rate were as follows: limited relations between teachers and students outside the classroom, lack of time, and the workload (this reason was reported too to constrain the interaction outside the classroom) (Table 5). An analysis was made to check for a difference in the reasons given by those teachers who address the subject of child maltreatment in the classroom and those who do not (Table 5). The chi-square tests point to significant associations (chi-square = 39.083, df = 10, p < 0.05), and means that there is a different explanation for the low reporting of maltreatment between those who address child maltreatment in the classroom and those who do not. It is worthy to note that some differences lay in the reasons “lack of interest in student issues” and “lack of time due to workload” given (in percentage) by more teachers who work on child maltreatment in the classroom than teachers who do not address this issue in the classroom. And even more, the lack of time due to workload is the most common reason in teachers who only sometimes work on the subject of child maltreatment in the classroom.

Table 5.

Reasons for the low reporting of child maltreatment by teachers who address in the classroom.

The main reason that was given for a lack of teacher–student relations from the teacher perspective was “lack of trust of the students” (reason given by 36% of the teachers). These reasons can also be tied in whether child maltreatment is addressed in the classroom or not (chi-square = 25.415, df = 6, p < 0.05, Table 6). Most teachers who tackle the issue attribute a lack of relations to “students’ fear of not being believed”, followed by “not wanting to interact with other adults and preferring to relate to their peers”. In contrast, “not wanting to relate to adults” is the primary reason put forward by those teachers who do not address child maltreatment in classroom.

Table 6.

Reasons for low student–teacher relations reported by teachers who address in the classroom.

The results highlight the need to tackle identified barriers like the lack of close teacher–student relations and the low reporting rate of CA by teachers in order to improve the effectiveness of interventions in schools.

3.3. Detection of Child Maltreatment by Teachers

The teachers were asked to self-report their ability to detect a possible case of child maltreatment through question 12 of the questionnaire (Table 7). This revealed that 49% (340 teachers) believed they could detect cases of child maltreatment. However, only 35% of the teaching staff have detected at least one case in their professional life, i.e., 227 teachers (question 11).

Table 7.

Self-reported ability to detect a possible case of child maltreatment.

Thus, a big discrepancy was observed between their perceived ability and their actual detection capacity (Table 8; chi-square = 16.181; sig. 0.003). Of the 49% who believed that they could detect a case (self-reported ability), only 20% had managed to identify one during their professional career. Hence, a total of 127 teachers reported that they had detected an actual case, while 191 considered themselves capable but had never detected one. These findings indicate that the teachers over-estimate their ability to detect child maltreatment when compared with the real number of detected cases.

Table 8.

Comparison of self-reported ability to detect child maltreatment and actual detection.

We also investigated whether theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment (questions 6–9) influenced the teachers’ self-reported ability to detect a potential case (question 12) and their actual detection of cases (question 11; Table 9). The results show that although 67% of the teachers with a basic theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment consider themselves to have a good detection capacity, 41% of the teachers without a basic theoretical grounding also regard themselves as being capable (chi-square = 43.203; p < 0.001). However, no differences were found in the real detection rate according to the teaching staff’s level of theoretical knowledge.

Table 9.

Relationship between the teachers’ theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment, their self-reported ability to detect a case, and their actual detection of cases.

Similarly, we also explored whether addressing child maltreatment in the classroom (question 17) leads to a higher self-reported and real detection capacity (Table 10). While 112 of the 211 teachers who actively deal with the subject of child maltreatment with their students have identified a potential case, only 117 of the 451 teachers who do not tackle the issue have managed to detect one (chi-square = 8070.049; sig. 0.000). However, no differences were observed in the two groups’ self-reported detection ability. These results highlight the importance of addressing the subject in class in the detection of cases.

Table 10.

The relationship between addressing child maltreatment in the classroom and teachers’ self-reported detection ability and actual detection of cases.

Finally, we analyzed whether a relationship of trust between teachers and their students influences the former’s self-reported detection ability and their real detection of child maltreatment (Table 11). It was observed that a higher relationship of trust goes hand in hand with a higher self-reported ability (chi-square = 48.262, df = 6, sig. = 0.000) and increased detection of child maltreatment (chi-square = 26.688, df = 6, sig. = 0.000).

Table 11.

The relationship between teacher–student trust and teachers’ self-reported detection ability and actual detection of cases.

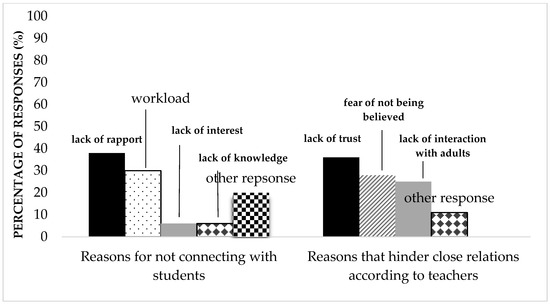

We also wished to gain an insight into the reasons for the underreporting of child maltreatment cases, as indicated by various studies. The teachers were asked why there was so little reporting of child maltreatment (question 10), with a lack of teacher–student relations accounting for 40% of the responses and a lack of time, due to the teachers’ workload, accounting for 27%, as shown in Figure 1 (left).

Figure 1.

Reasons for a lack of teacher–student relations (left) and perceptions of why students do not talk about personal problems, such as child maltreatment, to teachers (right).

3.4. Teacher–Student Alliances from the Teachers’ Perspective

Asked for the teachers’ perceptions of the relationship of trust that is forged with students in order to discuss child maltreatment or any other aspect of the students’ personal lives (question 16), the results reveal that only 25% of the teachers (n = 128 out of 662) believe they have built up sufficient trust to address these issues. In contrast, 31% of the teachers did not believe that enough trust existed and 32% replied that they did not know. In this way, 74% of the teachers believe that improvements must be made to strengthen communication links with their students, and only 17% do not see this as being necessary (question 14).

When the reasons why teachers believe that students do not share their problems with them were analyzed (question 13), 45% pointed to a lack of trust as the main reason, followed by fear (27%), and a preference for interacting with their peers rather than with adults (25%) (Figure 1, right).

Table 12 illustrates how building or not building a relationship of trust with students affects the teachers’ perceptions of why they assume students fail to interact much with their teacher. Teachers who forge a relationship of trust cite both fear and a lack of trust as reasons for a low rapport, while teachers who fail to build up trust do not consider fear to be a reason. The differences between both groups of teachers are statistically significant (Table 12; chi-square 23.237; sig. 0.006).

Table 12.

The relationship between teacher–student trust and the perceived reasons for a lack of teacher–student rapport.

Likewise, we explored whether addressing the issue of child maltreatment in the classroom was related to the amount of trust built up by the teacher with their students, finding that 42% of the teachers who deal explicitly with this issue in class believe that their students confide in them enough to make their problems known, as opposed to 19% who believe that they have a relationship of trust but do not address the subject with their students (Table 4).

4. Discussion

The results of this study offer insight into teachers’ perceptions and actions in schools with regard to the issue of child maltreatment. This allows conclusions to be drawn that can be used to help define plans of action to improve data on the prevention of child maltreatment and to facilitate the reporting of cases in schools.

The potential role of theoretical training in dealing with child maltreatment for teachers was analyzed as a specific variable that could relate to their capacity to detect possible cases. Our findings regarding teachers’ theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment, their perception of their awareness of the issue, and the training they had received coincide with the results of previous studies (Cantón Duarte and Cortés Arboleda 2007; Mathews et al. 2016; Ministerio de Sanidad 2024), according to which although theoretical knowledge improves a teacher’s perception of their ability to detect cases (Liébana Checa et al. 2015), surprisingly, it does not lead to an improvement in their actual detection capacity (Table 9). This highlights the need to review and improve the procedural guidelines of child maltreatment detection plans even after teachers have acquired basic theoretical knowledge. It is even possible that the theoretical knowledge they acquire might lead teachers to “let their guard down” since they over-confide in their perceived capacity to detect cases (Table 9).

As for factors related to the actual detection of child maltreatment by teachers, this research study reveals that actively addressing the issue in the classroom is associated with a 27% increase in the detection of cases (Table 10). Despite this, it does not guarantee successful detection as only 52% (112 of 211) of the teachers who tackle the subject in the classroom have detected at least one case.

The relationship of trust between teachers and their students is also related to an increase in the real detection capacity of child maltreatment cases. As seen in Table 12, 46.72% of the teachers who built up a relationship of this kind with their students have detected a case, compared to 33% of those teachers who did not manage to build up trust. In other words, a teacher–student relationship of trust boosts the capacity to detect cases of child maltreatment by approximately 14%.

A link was also found between the above two variables involved in the increased detection of child maltreatment: teacher–student trust and addressing child maltreatment in the classroom (Table 4). We hypothesize that there could be a common underlying factor to both variables (e.g., a concern for student issues) or it could be due to the personal characteristics of the teacher (close involvement in their work, a strong interest in people, extroversion, etc.).

The results therefore point to the need to strengthen teacher–student alliances to improve communication on sensitive issues such as child maltreatment, considering the perceptions and reasons cited by the teachers in this study. It would be interesting to predict which teacher’s characteristics are related to detection of child maltreatment.

These results are in line with the proposals of the Barnahus Model (Pereda 2021; Lind Haldorsson 2021; Consejo de Europa 2024), as well as the reports derived from its implementation in the different autonomous communities of Spain (Save the Children 2019; Save the Children and Fundació “la Caixa” 2020).

Teacher–Student Alliances

The teacher–student alliance proposed in this study is advocated as a key strategy in the improved detection of child maltreatment. Nowadays, our results show that 88% of 1160 students regard their teacher to be a reference figure (in press). However, a lack of trust of students (40%) and a heavy workload of teachers (30%) are seen as obstacles by teachers in building a deeper relationship with students. It must be noted that only 8% of them attribute this problem to a lack of interest in a teacher–student alliance.

Teacher–student alliances based on a relationship of trust, sensitivity, and commitment could facilitate the early detection and reporting of cases of child maltreatment. This could have a significant impact by putting an early stop to the harmful effects of child maltreatment and by providing crucial support to the sufferers (Monjas 1998; ONU 2006) through the figure of a teacher who is easily accessible to students. Furthermore, the teaching community has demonstrated a high interest in building this kind of alliance.

Study Limitations. This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences about the relationship between teacher–student alliances and detection capacity. Second, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias. Third, the sample, while substantial, is confined to Spain, which restricts generalizability to other cultural contexts. Finally, the qualitative questionnaire, though validated, did not capture longitudinal changes in teachers’ detection behaviors.

Future Research Additions. Future studies should (1) employ mixed-methods designs to triangulate self-reported data with observational measures of teacher–student interactions; (2) investigate institutional barriers (e.g., workload and administrative support) that hinder trust-building; (3) explore how cultural differences influence the formation of teacher–student alliances in multinational samples; and (4) develop and test training programs focused on practical skills for fostering trust and addressing maltreatment in classrooms.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis of teachers’ ability to detect cases of child maltreatment reveals a discrepancy between their perceived and real detection capacity. It also highlights the importance of actively addressing child maltreatment in the classroom and of building a teacher–student relationship of trust in the detection of cases, while no link was found between the teachers’ actual detection capacity and their theoretical knowledge of child maltreatment.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the importance of a relationship of trust between teachers and students as a key factor in the detection of child maltreatment. Establishing such trust requires intentional and sustained efforts on the part of educators. Effective strategies include demonstrating consistent emotional availability, engaging in non-judgmental and empathetic communication, and integrating trauma-informed practices into daily classroom interactions. Moreover, teachers can foster trust by establishing supportive classroom norms, clearly communicating their own trustworthiness, and showing respect and genuine care for students’ well-being. Institutional measures—such as reducing teacher–student ratios and providing specialized training in empathetic listening, child protection, and reporting procedures—can further facilitate the development of these trusting relationships.

Future research should prioritize identifying which specific teacher characteristics (e.g., communication styles, commitment, and professional credibility) and school policies most effectively foster trust-building in teacher–student alliances. Additionally, intervention studies are needed to evaluate whether training programs targeting these relational and trauma-informed practices improve detection rates and reporting behaviors among teachers.

This study provides actionable insights for the design of interventions and policies aimed at the prevention and early detection of child maltreatment in schools. By focusing on strengthening teacher–student alliances and addressing both individual and institutional barriers, educational systems can contribute to creating safer and more protective environments for children and adolescents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.-R.; methodology, M.T.V.-C., D.G.P., V.G.-A. and A.P.-R.; software, M.T.V.-C.; validation, M.T.V.-C., F.A.M.G., and V.G.-A.; formal analysis, M.T.V.-C. and A.P.-R.; investigation, M.T.V.-C.; resources, F.A.M.G., and V.G.-A.; data curation, M.T.V.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.V.-C., D.G.P., V.G.-A., and A.P.-R.; writing—review and editing, D.G.P., V.G.-A., F.A.M.G. and A.P.-R.; visualization, A.P.-R., M.T.V.-C., D.G.P. and V.G.-A.; supervision, A.P.-R.; project administration, A.P.-R. and V.G.-A.; funding acquisition, F.A.M.G. and V.G.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the data collection being conducted at a time when formal ethical approval was not mandatory for this type of research. However, the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study. The researchers ensured that participation was voluntary, and all data were collected and processed anonymously to protect participants’ privacy and confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical considerations, as the study was conducted at a time when formal ethical approval and data sharing agreements were not mandatory. All participants provided informed consent for data collection, but consent for public data sharing was not explicitly obtained. Researchers interested in the data may contact the corresponding author with their requests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the participants who voluntarily took part in this study and provided valuable data through their responses to our questionnaire. Their willingness to contribute their time and insights was crucial to the success of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Autonomous Community of Madrid. 2021. Protocolo de Actuación ante Situaciones de Desprotección Infantil y Maltrato Infantil en el ámbito Educativo. Madrid: Consejería de Educación y Juventud. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez, José Luis, María Fernández, and Ana G. Berbén. 2005. Conocimiento y actitud del maltrato entre alumnos (bullying) de los futuros docentes de educación infantil, primaria y secundaria. Revista de Enseñanza Universitaria 26: 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cantón Duarte, José, and María Rosario Cortés Arboleda. 2007. Malos Tratos y Abuso Sexual Infantil. Madrid: Siglo XXI de España Editores S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo de Europa. 2024. National and Regional Roadmaps for the Implementation of the Barnahus Model in Spain and its Regions: Executive Summaries. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden, Patricia M., and Mary. D. S. Ainsworth. 1989. Child maltreatment and attachment theory. In Child Maltreatment: Theory and Research on the Causes and Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect. Edited by D. Cicchetti and V. Carlson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 432–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral Blasco, Carmela. 2019. Más me Duele a mí. La Violencia que se Ejerce en Casa. Madrid: Save the Children España. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Employment and Social Affairs. 2004. Protocolo de Actuación en Casos de Maltrato Infantil en el ámbito Educativo. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Empleo y Asuntos Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Aguado, María José. 2001. El maltrato infantil. Revista de Educación. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, Monográfico Educación y Familia 325: 143–60. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2024a. Commission recommendation of 23.4.2024 on Developing and Strengthening Integrated Child Protection Systems in the Best Interests of the Child. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2024b. Putting Children’s Interests First: A Communication Accompanying the Commission Recommendation on Integrated Child Protection Systems. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro Monti, Claudia. 2021. Maltrato infantil. Odontología Sanmarquina 24: 393–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, David. 1984. Child Sexual Abuse: New Theory and Research. The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 77: 477–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, David, and Angela Browne. 1985. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 55: 530–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelhor, David, and Larry Baron. 1986. High Risk Children. In A Sourcebook on Child Sexual Abuse. Edited by David Finkelhor. Beverly Hills: Sage, pp. 60–88. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. n.d. Indicators of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/ODS/es/index.htm (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Keeping Children Safe. 2020. Los Estándares Internacionales de Protección Infantil Organizacional. London: Keeping Children Safe. [Google Scholar]

- Liébana Checa, José Antonio, María Isabel Deu del Olmo, and Santiago Real Martínez. 2015. Valoración del conocimiento sobre el maltrato infantil del profesorado ceutí. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía 26: 100–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, Alejandra Sánchez. 2022. Psicomotricidad: Una propuesta de intervención en el trabajo educativo docente para atender a alumnos que sufren maltrato infantil a nivel primaria: Psicomotricidad para docentes con niños con maltrato. Psicomotricidad Movimiento y Emoción 8: 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lind Haldorsson, Olivia. 2021. Barnahus Quality Standards: Guidance for Multidisciplinary and Interagency Response to Child Victims and Witnesses of Violence. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- López Sánchez, Félix, and Amaia Campo Sánchez. 2006. Evaluación de un programa de prevención de abusos sexuales a menores en Educación Primaria. Psicothema 18: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, Ben, Xing Ju Lee, and Rosana Norman. 2016. Impact of a new mandatory reporting law on reporting and identification of child sexual abuse: A seven year time trend and analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect 56: 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Austen, and Yo Jackson. 2018. A multilevel meta-analysis on academic achievement among maltreated youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 21: 450–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTavish, Jane R., Melissa Kimber, Karen Devries, Harriet L. Colombini, and Harriet L. MacMillan. 2017. Mandated reporters’ experiences with reporting child maltreatment: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 7: e013942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. 2024. Informe Anual de la Comisión Frente a la Violencia en los Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes 2022–2023. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. 2014. Protocolo Básico de Intervención Contra el Maltrato Infantil en el Ámbito Familiar Actualizado a la Intervención en los Supuestos de Menores de Edad Víctimas de Violencia de Género. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. [Google Scholar]

- Monjas, María Inés. 1998. Programa de Sensibilización en el Ámbito Escolar Contra el Maltrato Infantil. Valladolid: REA. [Google Scholar]

- ONU. 2006. Informe del Experto Independiente para el Estudio de la Violencia Contra los Niños. New York: Organización de las Naciones Unidas. [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio, Carlomagno, Brenda Jones Harden, and Jeffrey Harring. 2018. School readiness of maltreated preschoolers and later school achievement: The role of emotion regulation, language, and context. Child Abuse & Neglect 75: 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereda, Noemí (Coord.). 2021. Training and Education in the Barnahus Model: State of the Art. STEPS Project. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Prous Trigo, Paula Sofía. 2021. Aprendiendo sobre el abuso infantil: Un estudio piloto con docentes españoles. Investigación en la Escuela 105: 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta Climent, María Estrella, and Isabel Colinas Fernández. 2007. Detección y Prevención del Maltrato Infantil Desde el Centro Educativo. Guía para el Profesorado (Tercera Parte). Madrid: Defensor del Menor en la Comunidad de Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Safran, Jeremy D., and J. Christopher Muran. 2000. Negotiating the Therapeutic Alliance: A Relational Treatment Guide. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz, Vanesa, Marta González-Sánchez, and Carmen Ruiz-Alberdi. 2020. Knowledge of Child Abuse Among Trainee Teachers and Teachers in Service in Spain. Sustainability 12: 8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children. 2019. Bajo el Mismo Techo. Madrid: Save the Children España. [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children and Fundació “la Caixa”. 2020. Hacia la Barnahus. Madrid: Save the Children. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, Eric P., and Lawrence S. Wissow. 2017. The influence of childhood maltreatment on adolescents’ academic performance. Economics of Education Review 56: 604–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís de Ovando, Rodrigo. 2021. Nuevo Diccionario para el Análisis e Intervención Social con Infancia y Adolescencia. Bilbao: Dykinson-CIBES. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. 2024a. Nearly 400 Million Young Children Worldwide Regularly Experience Violent Discipline at Home. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. 2024b. Sexual Violence. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Comité Español. 2006. Convención Sobre los Derechos del Niño. Madrid: UNICEF Comité Español. Available online: https://www.un.org/es/events/childrenday/pdf/derechos.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- VanBergeijk, Ernst O., and Tracy L. Sarmiento. 2006. The consequences of reporting child maltreatment: Are school personnel at risk for secondary traumatic stress? Child and Youth Services Review 28: 1247–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, Ruth, Anabel Martina Greco, Ismael Loinaz, and Noemí Pereda. 2019. El profesorado español ante el maltrato infantil. Estudio piloto sobre variables que influyen en la detección de menores en riesgo. Revista Española de Investigación Criminológica 17: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2017. Global School Health Initiatives: Achieving Health and Education Outcomes. Report of a Meeting. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2022. Child Maltreatment. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2025. Child Maltreatment. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).