Mapping Collective Action: A Case Study of Identifying Assets and Actions During Community Mental Health Workshops to Address the Effects of Environmental Inequities

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Environmental Justice

1.2. Social Capital, Institutional Trust and Community Resilience

2. Methods

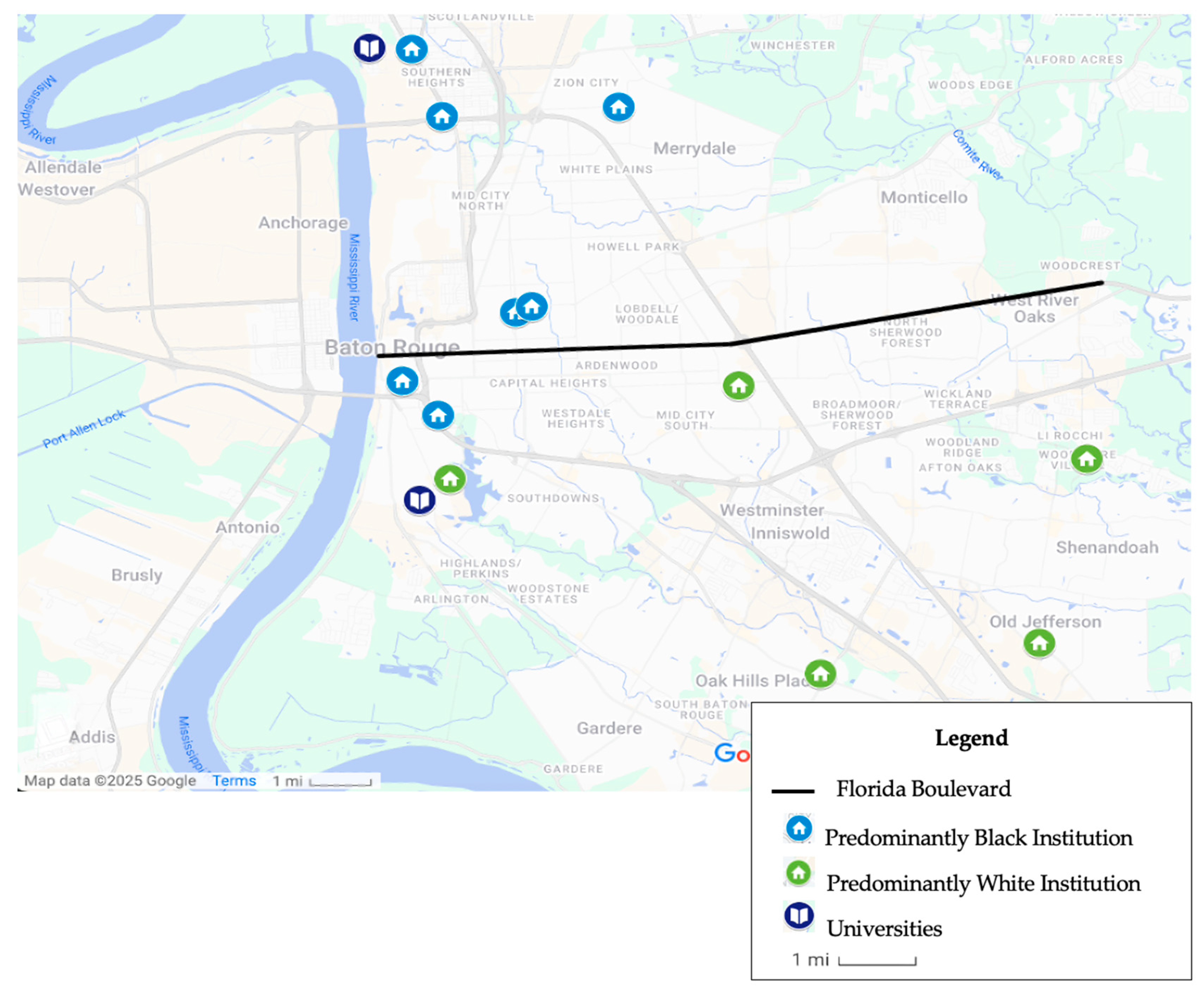

2.1. Setting

2.2. Community-Based Participatory Research and Asset Mapping

2.3. COPE (Communities Organizing for Power Through Empathy) Intervention

2.4. Sample and Recruitment

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. “Church Stepped Up”

3.2. Community Assets

3.3. Assets to Action

3.4. “We Got to Feed the People”

3.5. “There Should Be a List”

3.6. “Supporting Grandparents, Getting the Youth”

3.7. “Government’s Not Gonna Come to Our Rescue”

4. Discussion

4.1. Anchors and Social Cohesion

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, Carolyne, Christopher F. Karpowitz, and Chad Raphael. 2016. Affinity groups, enclave deliberation, and equity. Journal of Deliberative Democracy 12. Available online: https://delibdemjournal.org/article/id/530/download/pdf/ (accessed on 22 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Association of Religion Data Archives. 2020. East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana—County Membership Report (2020). Available online: https://www.thearda.com/us-religion/census/congregational-membership?y=2020&y2=0&t=0&c=22033 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Bailey, Zinzi D., Nancy Krieger, Madina Agénor, Jasmine Graves, Natalia Linos, and Mary T. Bassett. 2017. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. The Lancet 389: 1453–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakolis, Ioannis, Ryan Hammoud, Robert Stewart, Sean Beevers, David Dajnak, Shirlee MacCrimmon, Matthew Broadbent, Megan Pritchard, Narushige Shiode, Daniela Fecht, and et al. 2021. Mental health consequences of urban air pollution: Prospective population-based longitudinal survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 56: 1587–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barasa, Edwine, Rahab Mbau, and Lucy Gilson. 2018. What Is Resilience and How Can It Be Nurtured? A Systematic Review of Empirical Literature on Organizational Resilience. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7: 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiste, Johneisha. 2022. Being Black Causes Cancer: Cancer Alley and Environmental Racism. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolenza, Mia A., and LeaAnne DeRigne. 2019. The impact of climate change and natural disasters on vulnerable populations: A systematic review of literature. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 29: 266–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, Melanie, Ysanne Chapman, and Karen Francis. 2008. Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing 13: 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by J. G. Richardson. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, Isobel, Shuo Zhang, James B. Kirkbride, David P. J. Osborn, and Joseph F. Hayes. 2019. Air Pollution (Particulate Matter) Exposure and Associations with Depression, Anxiety, Bipolar, Psychosis and Suicide Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives 127: 126002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, Robert D. 1990. Dumping In Dixie: Race, Class, And Environmental Quality, 1st ed. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, Robert D. 1996. Environmental justice: It’s more than waste facility siting. Social Science Quarterly 77: 493–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, Robert D., Glenn S. Johnson, Sheri L. Smith, and Denae W. King. 2013. Living on the frontline of environmental assault: Lessons from the United States most vulerable communities. Revista de Educação, Ciências e Matemática 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bullard, Robert D., Paul Mohai, Robin Saha, and Beverly Wright. 2008. Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: Why Race Still Matters After All of These Years. Environmental Law 38: 371–411. [Google Scholar]

- Burris, Heather H., and Michele R. Hacker. 2017. Birth outcome racial disparities: A result of intersecting social and environmental factors. Seminars in Perinatology 41: 360–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, Paolo, Sophia Betrò, and Luigi Janiri. 2020. The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James S. 1988. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Timothy W., Sara E. Grineski, Jayajit Chakraborty, and Aaron B. Flores. 2019. Environmental injustice and Hurricane Harvey: A household-level study of socially disparate flood exposures in Greater Houston, Texas, USA. Environmental Research 179: 108772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Community Tool Box. n.d. Community Tool Box. Available online: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/identify-community-assets/main (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Creswell, J., and C. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design, 4th ed. New York: SAGE Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Deria, Anisha, Pedram Ghannad, and Yong-Cheol Lee. 2020. Evaluating implications of flood vulnerability factors with respect to income levels for building long-term disaster resilience of low-income communities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 48: 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Satu, and Helvi Kyngäs. 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Justice Resource Center. 1991. Principles of Environmental Justice. First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. Available online: https://www.ejnet.org/ej/principles.html (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Feagin, Joe. 2006. Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- First, Jennifer M., Kelsey Ellis, Mary Lehman Held, and Florence Glass. 2021. Identifying Risk and Resilience Factors Impacting Mental Health among Black and Latinx Adults following Nocturnal Tornadoes in the U.S. Southeast. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 8609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fos, Peter John, Peggy Ann Honore, and Russel L. Honore. 2021. Air Pollution and COVID-19: A Comparison of Europe and the United States. European Journal of Environment and Public Health 5: em0074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, Andrea, and Gordon Russell. 2016. Sobering Stats: 110,000 Homes Worth $20 B in Flood-Affected Areas in Baton Rouge Region, Analysis Says. The Advocate. Available online: http://www.theadvocate.com/louisiana_flood_2016/article_62b54a48-662a-11e6-aade-afd357ccc11f.html (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Gil-Rivas, Virginia, and Ryan P. Kilmer. 2016. Building Community Capacity and Fostering Disaster Resilience. Journal of Clinical Psychology 72: 1318–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakes, S., A. Hardison-Moody, S. Bowen, and J. Blevins. 2015. Engaging community change: The critical role of values in asset mapping. Community Development 46: 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keithly, Diane C., and Shirley Rombough. 2007. The Differential Social Impact of Hurricane Katrina on the African American Population of New Orleans. Race, Gender & Class 14: 142–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kruize, Hanneke, Mariël Droomers, Irene Van Kamp, and Annemarie Ruijsbroek. 2014. What Causes Environmental Inequalities and Related Health Effects? An Analysis of Evolving Concepts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11: 5807–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesen, A.E., C. Tucker, M. G. Olson, and R. J. Ferreira. 2019. ‘Come Back at Us’: Reflections on researcher-community partnerships during a post-oil spill gulf coast resilience study. Social Sciences 8: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ang, Mathew Toll, Erika Martino, Ilan Wiesel, Ferdi Botha, and Rebecca Bentley. 2023. Vulnerability and recovery: Long-term mental and physical health trajectories following climate-related disasters. Social Science & Medicine 320: 115681. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot, E., J. S. McCleary, and T. Lum. 2014. Asset mapping as a research tool for community-based participatory research in social work. Social Work Research 38: 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, Sarah R., Laura Sampson, Oliver Gruebner, and Sandro Galea. 2015. Psychological resilience after Hurricane Sandy: The influence of individual-and community-level factors on mental health after a large-scale natural disaster. PloS ONE 10: e0125761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y., N. Ruggiano, D. Bolt, J. P. Witt, M. Anderson, J. Gray, and Z. Jiang. 2023. Community asset mapping in public health: A review of applications and approaches. Social Work in Public Health 38: 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, Emily E., Lorraine Halinka Malcoe, Sarah E. Laurent, Jason Richardson, Bruce C. Mitchell, and Helen C. S. Meier. 2021. The legacy of structural racism: Associations between historic redlining, current mortgage lending, and health. SSM—Population Health 14: 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mix, Tamara L. 2011. Rally the people: Building local-environmental justice grassroots coalitions and enhancing social capital. Sociological Inquiry 81: 174–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. 2021. Mental Health in Louisiana State Fact Sheet. Arlington: National Alliance on Mental Illness. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. 2023. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Prado, C., Z. Bowmani, C. Raphael, and M. Matsuoka. 2024. Law, Policy, Regulation, and Public Participation. GROUND TRUTHS 133. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, Tara, Jennifer Scott, Paula Yuma, and Yuan Hsiao. 2022. Surviving the storm: A pragmatic non-randomised examination of a brief intervention for disaster-affected health and social care providers. Health & Social Care in the Community 30: e6217–e6227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, John D., Alexandra B. Nolen, Hilton Kelley, Ken Sexton, Stephen H. Linder, and John Sullivan. 2014. Social Determinants of Health in Environmental Justice Communities: Examining Cumulative Risk in Terms of Environmental Exposures and Social Determinants of Health. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 20: 980–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, Robert D. 1995. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. Journal of Democracy 6: 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillian, Lincoln, John J. Lee, and Brandon Honoré. 2020. Racial discrimination in the U.S. housing and mortgage lending markets: A quantitative review of trends, 1976–2016. Race and Social Problems 12: 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, Abdullah Mohammed Hassan, and Ahmed G. Ataallah. 2021. Are climate change and mental health correlated? General Psychiatry 34: e100648. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8578975/ (accessed on 22 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Reininger, Belinda M., Mohammad H. Rahbar, MinJae Lee, Zhongxue Chen, Sartaj R. Alam, Jennifer Pope, and Barbara Adams. 2013. Social capital and disaster preparedness among low income Mexican Americans in a disaster prone area. Social Science & Medicine 83: 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Brian K., and Laura Maninger. 2016. “We were all in the same boat”: An exploratory study of communal coping in disaster recovery. Southern Communication Journal 81: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, Jason David, and Ashley E. Nickels. 2014. Social capital, community resilience, and faith-based organizations in disaster recovery: A case study of Mary Queen of Vietnam Catholic Church. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 5: 178–211. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlman, D., S. Samon, S. Allan, M. Barton, H. Dixon, C. Ghetu, L. Tidwell, P. Hoffman, A. Oluyomi, E. Symanski, and et al. 2022. Designing equitable, transparent community-engaged disaster research. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 7: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, Richard. 2017. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Royer, L. A. 2022. Environmental and human health justice: A call to greater action. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 18: 303–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosberg, David, and Lisette B. Collins. 2014. From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 5: 359–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Jennifer L, Powell, Tara, and Together Baton Rouge. 2023. Communities Organizing for Power Through Empathy (COPE): A Psychoeducational Program for Communities Affected by Disaster & Beyond. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University. [Google Scholar]

- Sederer, Lloyd I. 2016. The Social Determinants of Mental Health. Psychiatric Services 67: 234–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, Patrick. 2007. Survival and Death in New Orleans: An Empirical Look at the Human Impact of Katrina. Journal of Black Studies 37: 482–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipper, Antonius D., Andrew H. Rose, Noel A. Card, Travis James Moore, Debra Lavender-Bratcher, and Cassandra Chaney. 2023. Relational sanctification, communal coping, and depression among African American couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 49: 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Genee S., E. Anjum, C. Francis, Lauren Deanes, and C. Acey. 2022. Climate change, environmental disasters, and health inequities: The underlying role of structural inequalities. Current Environmental Health Reports 9: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, Howard W., David R. Cross, Karyn B. Purvis, and Melissa J. Young. 2004. A Study of Church Members During Times of Crisis. Pastoral Psychology 52: 405–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoresen, Siri, Marianne S. Birkeland, Tore Wentzel-Larsen, and Ines Blix. 2018. Loss of trust may never heal. Institutional trust in disaster victims in a long-term perspective: Associations with social support and mental health. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toldson, Ivory A., Kilynda Ray, Schnavia Smith Hatcher, and Laura Straughn Louis. 2011. Examining the long-term racial disparities in health and economic conditions among Hurricane Katrina survivors: Policy implications for Gulf Coast recovery. Journal of Black Studies 42: 360–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, Antonio, Antonello Bellomo, Ilaria di Gioia, Dario Di Sabatino, Donato Favale, Domenico De Berardis, and Paolo Cianconi. 2021. Environmental pollution and mental health: A narrative review of literature. CNS Spectrums 26: 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software. 2024. MAXQDA 24 (Version 24.7.0) [Computer software]. VERBI Software. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Viswanathan, Meera, Alice Ammerman, Eugenia Eng, Gerald Garlehner, Kathleen N. Lohr, Derek Griffith, Scott Rhodes, Carmen Samuel-Hodge, Sioban Maty, Linda Lux, and et al. 2004. Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (Summary) 99: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Walinski, Annika, Julia Sander, Gabriel Gerlinger, Vera Clemens, Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg, and Andreas Heinz. 2023. The Effects of Climate Change on Mental Health. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 120: 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, Nina B., and Bonnie Duran. 2006. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to Address Health Disparities. Health Promotion Practice 7: 312–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Bradley, Eric Tate, and Christopher T. Emrich. 2021. Flood recovery outcomes and disaster assistance barriers for vulnerable populations. Frontiers in Water 3: 752307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, Anna, Nekane Basabe, Dario Páez, Carlos Reyes, Loreto Villagrán, Camilo Madariaga, Jorge Palacio, and Francisco Martínez. 2016. Communal coping and posttraumatic growth in a context of natural disasters in Spain, Chile, and Colombia. Cross-Cultural Research 50: 325–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2022. Mental Health and Climate Change: Policy Brief. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/354104/9789240045125-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Yang, Ye-Seul, and Sung-Man Bae. 2022. Association between resilience, social support, and institutional trust and post-traumatic stress disorder after natural disasters. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 37: 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Shuo, Isobel Braithwaite, Vishal Bhavsar, and Jayati Das-Munshi. 2021. Unequal effects of climate change and pre-existing inequalities on the mental health of global populations. BJPsych Bulletin 45: 230–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| North | South | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Institutions | 42% (5) | 58% (7) |

| Predominantly White | 0 | 71% (5) |

| Predominantly Black | 100% (5) | 29% (2) |

| Denomination: | ||

| Baptist | 40% (2) | 14% (1) |

| Catholic | 20% (1) | 14% (1) |

| Others | 40% (2) | 71% (5) |

| Number of Assets Identified | 214 | 209 |

| Number of Actions Discussed | 4 | 4 |

| Total Participants (n and %) | 47% (69) | 53% (79) |

| Individual | Network | Institutional | Physical | Economic | Cultural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What assets were identified? | ||||||

| What assets were anomalies? | ||||||

| What assets were absent? |

| Individual | Network | Institutional | Physical | Economic | Cultural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What assets were identified? | Pastors; Elected Officials | Sorority/ Fraternity; Neighborhood Association; High School Alumni Networks | Church; Schools; Community Center; Library | Parks; Lake; Bike Paths; Community Centers | Local Business; Banks; Credit Union; SU Small Business Association | Festivals; Parades; University Museums; University Football Teams and Tail Gate; Church Activities |

| What assets were anomalies? | Police; Meat Market | Mississippi River | High Tax Base | |||

| What assets were absent? | Skilled People | Directory of Church Members | Reliable Transportation; Grocery Store; Hospital | Sustainable Funding for Community Projects | Diversity | |

| Green = South Baton Rouge church(es); Blue = North Baton Rouge church(es) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee-Johnson, N.M.; Scott, J.L.; Powell, T. Mapping Collective Action: A Case Study of Identifying Assets and Actions During Community Mental Health Workshops to Address the Effects of Environmental Inequities. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050284

Lee-Johnson NM, Scott JL, Powell T. Mapping Collective Action: A Case Study of Identifying Assets and Actions During Community Mental Health Workshops to Address the Effects of Environmental Inequities. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(5):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050284

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee-Johnson, Natasha M., Jennifer L. Scott, and Tara Powell. 2025. "Mapping Collective Action: A Case Study of Identifying Assets and Actions During Community Mental Health Workshops to Address the Effects of Environmental Inequities" Social Sciences 14, no. 5: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050284

APA StyleLee-Johnson, N. M., Scott, J. L., & Powell, T. (2025). Mapping Collective Action: A Case Study of Identifying Assets and Actions During Community Mental Health Workshops to Address the Effects of Environmental Inequities. Social Sciences, 14(5), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050284