Abstract

In recent years, research has highlighted a concerning lack of commitment and motivation among students on a global scale, leading to persistently low levels of competence across various areas of study. This phenomenon and its social consequences reveal a growing unease and an urgent need for sustainable solutions. Within the educational context, social cognitive theory explores self-regulated learning processes as the ability to manage and master a set of crucial factors for high-quality learning and academic excellence. Managing volitional control strategies is also essential in achieving academic success. The study aimed to analyze, through structural equation modeling, how self-regulated learning processes influence students’ academic performance. It also investigated how the volitional control strategies adopted by students might mediate between self-regulated learning and academic performance. The sample included 647 students (Mage = 12.9) from the primary education cycle in Portuguese schools. The results showed that students with higher levels of self-regulated learning achieve better academic outcomes and more frequently employ volitional control strategies. Consequently, students who apply more volitional control strategies obtain superior academic performance, confirming the mediating role of these strategies. Some educational implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

Research into the need for students to acquire skills that keep pace with rapid developments in all areas of knowledge is essential in today’s world. The significance of improving academic performance was highlighted in the report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD 2023) which indicates a significant decline in students’ skills in key areas such as reading, mathematics, and science. These deficiencies, which go beyond the impact at school, have profound social implications, jeopardizing individual and collective development (Lourenço and Paiva 2024b). Also, data from the General Directorate of Education and Science Statistics (DGEEC) in Portugal for the 2022–23 school year also indicate that 3.8% of students did not advance to the next grade or complete basic education. In the case of secondary education, school failure was more significant, with around one in ten students (9.8%) failing or dropping out at this level. The data also indicate that retention or dropout rates increased at all levels of education in 2022/23 (EDUSTAT 2024).

In this context, the need to understand the factors that drive academic success has become a priority. These include self-regulation of learning (SRL) processes and volitional control strategies, which have been identified as key to promoting student commitment, motivation and autonomy (Vera 2022). Within this framework, Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory provides a valuable lens through which to understand the role of personal agency and self-regulation in academic success. These approaches allow students to develop essential skills to plan, monitor, and adjust their efforts, facing educational challenges more effectively. For Zimmerman (2002), SRL, as a pillar for student autonomy, combined with volitional control—crucial for managing distractions and staying focused on goals—has emerged as an indispensable field of study for understanding how students can achieve excellent school performance, even in adverse contexts.

These data are of singular importance, as they represent the first international assessment to capture student performance following the devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent school closures. This context partially explains the troubling results emerging from various nations. Within the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), approximately 690,000 students from participating countries were assessed in mathematics, reading, and science (OECD 2023). The results paint a bleak picture: a significant decline in the competencies of young people in OECD nations. The report also indicates that one in four 15-year-olds performs unsatisfactorily in the assessed areas, struggling with basic algorithms and interpreting simple texts (OECD 2023).

Addressing the persistent issue of low academic performance requires an approach that intertwines metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral strategies within the microcosm of the classroom. Such an approach empowers students to increase their engagement with learning, take an active role, and monitor the effectiveness of their study methods (Gutiérrez-Braojos 2015).

In this sense, SRL processes and volitional control strategies are fundamental to understanding and promoting school success. SRL mitigates the lack of future orientation and inadequate conceptions of learning, positively impacting self-efficacy beliefs, study effort, and academic performance (Lourenço and Nogueira 2014). As Zimmerman (2008) emphasizes, academic success should be seen as a dynamic system in which the interaction between motivational and volitional variables is essential to enriching the understanding of learning processes and improving pedagogical practices.

Understanding and improving academic performance has therefore become an essential priority, not only to raise educational standards but also to ensure a more promising and balanced future for coming generations.

This way, SRL takes center stage, acting as a fundamental pillar in promoting student autonomy (Schunk and Zimmerman 2023). This concept highlights the importance of students’ active involvement in cognitive, behavioral, and motivational domains (Alliprandini et al. 2023). Volitional control strategies play a crucial role in self-regulated learning, assisting students in overcoming distractions, maintaining focus on their objectives, and tackling intellectual challenges. The effective integration of these strategies not only enhances learning efficiency but also transforms it into a more meaningful process, directly reflecting on students’ academic success (Vera 2022).

In the field of SRL research, studies explore how students take proactive control of their educational process, guiding and modulating their cognition, motivation, and behavior towards their set goals. This approach advocates for developing an educational culture that elevates SRL to a primary objective within schools’ psycho-pedagogical projects (Parveen et al. 2023).

The literature acknowledges the importance of volitional control strategies within SRL as essential for superior academic performance. Vera (2022) describes volitional control as processes that shape effort, concentration, and performance. Volition becomes evident when a student, despite having potential, fails to engage adequately in tasks, thereby compromising their achievement. Vermeer et al. (2000) highlight that students’ perseverance in striving for excellence is directly linked to volitional control, while Boekaerts and Cascallar (2006) argue that these strategies help maintain task focus by isolating distractions related to well-being. Such strategies result in solid work habits, both inside and outside school (Fuentes et al. 2023; Lourenço and Nogueira 2014). Recent studies (Fuentes et al. 2023; Rodríguez-Guardado and Juárez-Díaz 2023; Vera 2022) emphasize how these variables are crucial for understanding educational success, influencing students’ academic performance.

Thus, this study investigates how SRL processes influence the selection of volitional control strategies and their impact on academic performance. Additionally, it explores the mediating role of volitional control in this relationship, an aspect still underexplored in the literature, thus contributing to a significant advancement in understanding the mechanisms underlying academic success.

2. Review of the Literature and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Self-Regulated Learning

In SRL research, the role of specific cognitive strategies—such as monitoring, goal setting, and time management—has been highlighted in promoting effective learning and improving academic performance (Schunk and Zimmerman 2012; Arcoverde et al. 2022).

For a student to be truly self-regulated, they need to actively and consciously engage in their learning process, both meta-cognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally (Zimmerman 2002). However, without an accurate assessment of what they know and what they still need to learn, students are unlikely to engage in advanced metacognitive activities, such as evaluating or monitoring their progress (Parveen et al. 2023). Therefore, it is essential to guide them in developing knowledge and skills to manage and regulate these learning processes, whether independently or collaboratively, promoting transformations applicable to various contexts (Hadwin et al. 2011).

Bandura’s (1986, 2002) social cognitive theory provides a fundamental approach that explores the interaction between personal, behavioral, and environmental factors in human behavior (Frison and Boruchovitch 2020). This theory stands out for its emphasis on the ability of individuals to self-regulate, interpret information, and perform behavior, recognizing their active role in the learning process, always with the goal of academic success in mind.

Bandura (2002) sees the human mind as productive and reflective, rather than merely reactive. The concept of human agency, central to his theory, encompasses abilities such as symbolizing, learning from others, planning, self-regulating, and self-reflecting, which allow individuals to adjust their behaviors and achieve positive outcomes. These skills are closely linked to SRL, with intentionality guiding efforts towards educational goals, forethought adjusting strategies when facing challenges, self-reactivity responding appropriately to obstacles, and self-reflection enabling continuous improvement (Bandura 2008; Zivich and Alliprandini 2023). These concepts are essential in studying academic success and the associated variables.

SRL thus emerges as a process in which students activate and maintain cognitions, emotions, and behaviors to achieve defined goals, fostering a virtuous cycle of motivation and continuous growth (Lourenço and Paiva 2024a, 2024b).

2.2. Volitional Control Strategies

Zimmerman (2002) defines SRL as a dynamic, cyclical process involving anticipation, volitional control, and self-reflection. Volition is key in managing psychological processes, sustaining concentration, and directing effort towards tasks. Feedback from previous actions guides future behavior, enabling students to regulate and align their actions with their goals. In this context, volitional control influences concentration and performance, as students who struggle to engage effectively often fail to reach their full potential (Vera 2022).

During the volitional control phase, Lourenço (2008) identifies two key processes: self-control and self-monitoring. Self-control involves self-instruction, mental imagery, and task-focused strategies, while self-monitoring requires tracking performance, environmental factors, and outcomes. These strategies help students execute their learning plans, apply appropriate techniques, and continuously assess their progress. Several authors highlight that accessing feedback and performance records allows students to evaluate their success and make necessary adjustments (Ganda and Boruchovitch 2019; Silva and Alliprandini 2020; Vieira et al. 2021; Frison et al. 2021; Silva and Bizerra 2022).

Lourenço (2008) suggests that strategies such as self-instructions, time management, continuous feedback, goal setting, and self-motivation enhance self-regulation, ensuring that effective learning efforts are directed toward academic success. Similarly, Vermeer et al. (2000) assert that perseverance and mastery in the face of difficulties depend on access to volitional control strategies, while Boekaerts and Cascallar (2006) emphasize that these strategies enable students to maintain focus, avoid distractions, and develop consistent work habits in and outside the school environment (Fuentes et al. 2023).

Beyond academic performance, volitional skills help students meet social expectations, such as demonstrating responsibility, collaborating in groups, and adhering to teachers’ standards (Boekaerts and Cascallar 2006). MacCann and Turner (2004) further argue that volitional control fosters greater self-engagement, self-regulation, and cognitive progress. Therefore, it is crucial to identify school environments that cultivate volitional control and recognize its role in various classroom activities. Although the literature on SRL is extensive and acknowledges its contribution to academic performance, gaps remain in understanding the interaction between its various dimensions, as well as the specific mechanisms underpinning this relationship in real educational contexts (Zimmerman 2002).

2.3. Academic Performance

Academic performance translates into the level of achievement students demonstrate in school activities and involves more than mere knowledge acquisition. It also reflects the practical application of learning, collaboration, time and resource management, and a proactive attitude. It thus results from the interaction between contextual factors, such as the school environment and family support, and individual characteristics, such as self-regulation, self-efficacy, and motivation, which directly influence how students engage and progress in their educational journey (Fernandes and Lemos 2020). It is commonly evaluated through tasks, tests, and exams, where students’ responses indicate their understanding of the material.

This performance is influenced by a complex interplay of individual and environmental factors (Fernandes and Lemos 2020). Effective self-regulated learning (Lourenço and Paiva 2016) and volitional strategies (Vera 2022) play a key role in shaping academic outcomes. Given that students are social beings shaped by their relationships and contexts, schools must develop strategies aligned with students’ goals, recognizing that motivation and future expectations, shaped by family, teachers, and peers, significantly impact performance (Ribeiro 2011).

Volitional control, which regulates behavior to sustain learning goals, remains less explored than cognitive and emotional regulation (Duckworth and Seligman 2005). Integrating volitional control within SRL research provides a broader understanding of how students manage cognitive processes, intentions, and actions throughout their educational journey. Additional studies may contribute to a deeper understanding of the interaction between SRL and volitional strategies in specific educational contexts, complementing the existing evidence on their general benefits (OECD 2023; Pintrich 2000). Investigating these mediating factors could lead to more effective, context-based pedagogical interventions.

In this study, academic performance was assessed based on students’ scores in Portuguese, Mathematics, English, and Natural Sciences—subjects that play a crucial role in cognitive skill development due to their challenges and final exams. These assessments provide an objective measure of student achievement and are closely linked to academic and professional success. According to the OECD (2023), they are essential for identifying learning gaps and ensuring students acquire fundamental competencies for adulthood.

A Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) approach was used to integrate these subject assessments into a single academic performance indicator, treating them as variables for a latent construct. This method offers a comprehensive measure of student achievement across different knowledge domains. In Portugal’s basic education system, grades are classified as follows: 1 and 2 (insufficient), 3 (sufficient), 4 (good), and 5 (very good).

2.4. Hypotheses

Based on the results of the aforementioned studies, as well as successive systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Richardson et al. 2012), which explore the interconnection between the variables under analysis, this study sets out to investigate how the SRL processes developed by students influence the choice of volitional control strategies and how these impact their academic performance. In addition, the aim is to understand whether volitional control strategies mediate the relationship between SRL and academic performance. With this in mind, the following hypotheses were formulated, and some of the reasons for their formulation were presented.

Students who develop advanced SRL skills tend to demonstrate higher intrinsic motivation, which leads them to become more actively involved in tasks, even those that are more challenging (Alliprandini et al. 2023). In addition, these students show a greater ability to manage their time efficiently and organize their study activities, which contributes to greater academic success (Callan et al. 2022). Another relevant aspect is resilience in the face of difficulties. Self-regulated students are more prepared to face academic challenges, staying focused on their goals and overcoming barriers that could hinder their learning. Thus, hypothesis 1 was set: H1—Students with higher levels of SRL achieve better academic performance.

Volitional control strategies help maintain concentration. For example, by eliminating distractions, students can maintain their focus over longer study periods, increasing the effectiveness of the time dedicated to learning (Vera 2022). In addition, volitional control strategies allow students to overcome difficulties such as procrastination or emotions that can interfere with academic progress, such as discouragement or lack of motivation. This set of strategies also allows for more efficient adaptation to the context or nature of the tasks, adjusting study methods to specific needs. Thus, hypothesis 2 was set: H2—Students who self-regulate their learning more effectively tend to employ more volitional control strategies.

Volitional strategies help students control negative emotions such as anxiety, enabling them to perform better in assessment tasks or exams. In addition, adopting volitional control strategies favors long-term persistence, which is essential for achieving more long-term goals, such as effectively preparing for final assessments (Silva and Bizerra 2022). It is also important to note that the effectiveness of volitional strategies can vary depending on the subject. For example, solving problems in mathematics may require different approaches compared to memorizing concepts in natural sciences. Thus, hypothesis 3 was set: H3—Students who choose more volitional control strategies attain better academic results.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

A non-probability sampling process was chosen, specifically convenience sampling, a method described by Lohr (2022) as suitable when there are no specific criteria for selecting participants. In this scenario, any member of the population may be included in the sample, which facilitates rapid and cost-effective data collection with fewer restrictions. However, a limitation is that there is no guarantee that the samples are free from bias. Of the 691 questionnaires initially distributed, 678 were collected, representing a return rate of 98.1%. Of these, 647 (95.4%) were deemed valid for analysis, as they were fully completed.

The study involved 647 basic education students (7th, 8th, and 9th grades) from Portuguese public schools, of whom 331 (51.2%) were female, aged between 12 and 15 years (M = 12.9; SD = 0.969). It was observed that 395 (61.1%) of the students were in the 7th grade, 145 (22.4%) in the 8th grade, and 107 (16.5%) in the 9th grade. Regarding the average grades obtained in the assessed subjects, the results were as follows: Portuguese (M = 2.84; SD = 0.782); Mathematics (M = 2.71; SD = 0.873); English (M = 3.02; SD = 1.021); and Natural Sciences (M = 3.05; SD = 0.824).

3.2. Instruments

To assess students’ self-regulated learning processes, the Self-Regulated Learning Processes Inventory (SRLPI; Rosário et al. 2010) was used. This questionnaire consists of 9 items, distributed across three dimensions: Planning (PL, α = 0.80; e.g., “I make a plan before starting a task. I think about what I am going to do and what is needed to complete it”); Execution (EX, α = 0.86; e.g., “During lessons or while studying at home, I think about specific aspects of my behavior to change and achieve my goals”); and Evaluation (EVA, α = 0.85; e.g., “When I receive a grade, I think about concrete things I need to do to improve”). Each dimension comprises three items, rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

To examine students’ volitional competence, the Volitional Control Strategies Questionnaire (VCSQ; Leite 2008) was applied. This instrument consists of a single-factor structure with 9 items (VC, α = 0.94; e.g., “Thinking that if I don’t get a good grade, it will be my responsibility”). Responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), measuring the frequency of strategy use. Some items were reverse-coded to ensure response consistency.

Additionally, the Personal and School Data Form was used to characterize the sample, gathering information on gender, age, educational level, and grades in Portuguese, Mathematics, English, and Natural Sciences. In the proposed model, only the academic grades were considered to calculate the endogenous variable of academic performance.

All instruments used in this study were validated for the Portuguese context, and the reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alphas) reported refer to the present sample.

3.3. Procedures

After obtaining the necessary authorization from the school cluster directors and the students’ guardians for administering the questionnaires, the distribution process began. In most schools, the questionnaires were left in the administrative office, awaiting later collection. In some institutions, the opportunity arose to administer the questionnaire directly, in the researcher’s presence, asking students to respond honestly and without omitting any questions. It is important to note that, regardless of the method of administration, equivalent conditions of confidentiality, anonymity, and instructions were ensured to guarantee the uniformity of procedures across all contexts.

The confidentiality of the responses was meticulously ensured, student participation was entirely voluntary, and the ethical principles stipulated by the schools were rigorously followed. This study was conducted following the Helsinki Declaration (2013) and the ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Association. The inclusion criterion for this study required participants to be students in the 3rd cycle (7th, 8th, and 9th grades) of public schools. Only fully completed questionnaires were considered valid for analysis.

3.4. Data Analysis

The instruments’ validity and reliability were analysed through the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity. These indices revealed the feasibility of principal component analysis and confirmed that the variables in question are interrelated. Given the Likert format of the items, internal consistency—the extent to which the items form a cohesive whole—was determined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α > 0.70; Marôco 2021).

In the preliminary phase of descriptive analysis of the items, stringent criteria were established to ensure normality, setting the skewness limits at <2 and kurtosis limits at <7, according to the Finney and Distefano (2013) approach. The evaluation of the SEM results was conducted using SPSS/AMOS 29 (Arbuckle 2022), focusing on two crucial aspects: the overall fit of the model and the significance of the calculated regression coefficients.

For this evaluation, we examined the model fit indices and the magnitude of the factor loadings, indicative of the constructs’ representativeness. The criteria used included χ2; χ2/df ratio; GFI ≥ 0.90 (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1983); AGFI ≥ 0.90 (Hu and Bentler 1999); CFI ≥ 0.95 (McDonald and Ho 2002); TLI ≥ 0.95 (Hair et al. 2019); RMSEA < 0.05 (Byrne 2016); and Critical N > 200 (Marôco 2021). Factor loadings ≥ 0.40 were considered significant, as indicated by Brown (2015).

Regarding the reliability of the scores, and considering the sample size (>300) and the number of items involved, the data demonstrated sufficient internal consistency and stability, supporting the robustness required for a thorough analysis.

Finally, to understand the intensity and direction of the relationships between the constructs, Pearson’s linear correlation (r) was applied. In this process, the values indicate the strength of the connections: when below 0.200, they represent a very weak, almost negligible association. Ranges between 0.200 and 0.399 reflect a weak relationship, suggesting tenuous links between the constructs, values between 0.400 and 0.699 indicate a moderate association, values between 0.700 and 0.899 indicate a high association, and values between 0.900 and 1 indicate a very high association (Hair et al. 2019).

4. Results: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics for the SRL variables, volitional control, and academic performance are presented in Table 1. The table includes means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis values. The results indicate that the data are reasonably normally distributed, with skewness and kurtosis values within the expected range, confirming the suitability of the data for subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the variables included in the model.

4.2. Model Fit and Hypotheses

The values obtained for the global fit indices of the proposed SEM reveal significant robustness [χ2(4) = 7.736; p = 0.102; χ2/df = 1.934; GFI = 0.995; AGFI = 0.982; TLI = 0.989; CFI = 0.996; RMSEA = 0.038 (90% CI: 0.000–0.078); Critical N (0.05/793–0.01/1109)], supporting the hypothesis that the proposed model adequately reflects the relationships between the variables in our empirical matrix. KMO values of 0.841 for SRL and 0.932 for volitional control strategies indicate excellent sample adequacy for factor analysis, since values above 0.80 are considered satisfactory. The results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity—with values of χ2(30) = 3126.836; p < 0.000 for SRL and χ2(36) = 4752.465; p < 0.000 for volitional control strategies—confirm the existence of significant correlations among the variables, justifying the application of factor analysis.

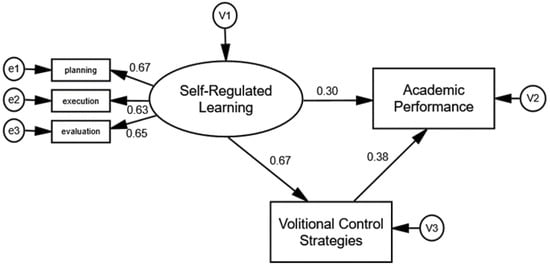

Analysis of Figure 1 and Table 2 confirms the hypotheses underlying the specifications, all of which are positive and statistically significant. It is observed that students with higher levels of SRL tend to achieve better academic performance (H1; β = 0.30; p < 0.001) and more frequently use volitional control strategies (H2; β = 0.67; p < 0.001). Additionally, it is noted that students who use more volitional control strategies have higher academic performance (H3; β = 0.38; p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

SEM model (n = 647).

Table 2.

Results of the hypothesised covariance structure for the sample.

The observation of the data reveals that the regression coefficients between the latent variables are statistically significant (p < 0.05), suggesting that the relationships posited in the model have a robust statistical foundation. Furthermore, the analysis of residuals and modification indices (MI) indicated the absence of significant discrepancies not explained by the model. The standardized residuals were small, and the modification suggestions did not indicate the omission of essential relationships, thus confirming the adequacy of the proposed model to the relationships outlined in the empirical matrix.

This description highlights that the supplementary analysis confirms the robustness and suitability of the model, reinforcing the validity of the relationships established between the variables. By meeting these criteria, we can confidently state that the proposed model accurately reflects the relationships among the variables in the empirical matrix, indicating a satisfactory fit of the model to the observed data.

From the constructed theoretical model, the multiple squared correlations indicate that academic performance is directly explained by SRL and indirectly by volitional control strategies, representing approximately 38% (η2 = 0.382). Volitional control strategies, in turn, are directly explained by SRL by about 45% (η2 = 0.445).

4.3. Correlations Between Variables

An additional analysis was carried out to measure the intensity and direction of the linear relationship between the variables under study (Table 3). Two variables are correlated when a change in one induces a change in the other, with this relationship being quantified by Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient (Hair et al. 2019).

Table 3.

Pearson correlations of the variables included in the model.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to analyze the relationships between SRL processes, volitional control strategies, and academic performance. The results revealed weak to moderate correlations (predominantly moderate) among the variables, reflecting significant interconnections that support the proposed theoretical model (Table 3).

A moderate positive correlation was found between academic performance and the planning dimension (r = 0.41; p < 0.01), as well as weaker positive associations with execution (r = 0.31; p < 0.01) and evaluation (r = 0.34; p < 0.01). Meanwhile, volitional control strategies showed a significant moderate positive correlation with academic performance (r = 0.58; p < 0.01), suggesting that students who frequently employ these strategies tend to achieve better academic results.

Additionally, a positive association was identified between SRL processes and volitional strategies, indicating that students who actively regulate their learning are more likely to rely on these mechanisms. Specifically, moderate correlations were observed between volitional control and planning (r = 0.46; p < 0.01), execution (r = 0.40; p < 0.01), and evaluation (r = 0.44; p < 0.01).

These findings highlight the importance of SRL and volitional control as key predictors of academic success. Students who effectively plan, implement, and monitor their learning tend to adopt more volitional strategies, which, in turn, positively influence their academic performance.

5. Discussion

This study investigated how SRL processes influence students’ academic performance and how volitional control strategies might mediate the relationship between SRL and academic achievement. The existing literature establishing relationships between these constructs is limited, and research employing SEM methodology is scarce. Therefore, given the educational relevance of this research, the intention is to broaden the analysis of the relationships between the studied variables using this analytical method, which allows for the simultaneous consideration of all direct and indirect effects. In this context, the study’s data validated the hypotheses proposed in the model by examining the interactions between the considered variables.

5.1. Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Performance (H1)

The results demonstrate that students with higher levels of SRL exhibit higher academic performance, confirming the findings of previous studies (Callan et al. 2022; Lourenço and Paiva 2024a). This result aligns with the statement by Ganda and Boruchovitch (2019), who emphasize that students who plan, control, and evaluate their cognitive, motivational, emotional, contextual, and behavioral processes—i.e., those who engage in SRL—tend to achieve higher performance. For academic performance to be realized, it is crucial to create learning environments that foster the processes underlying SRL. In these educational contexts, students and teachers must understand the interdependence of their roles and implement realistic self-regulatory models in the learning process (Parveen et al. 2023).

Thus, it is crucial to identify the variables that outline the framework of SRL, as this is a fundamental construct for explaining students’ academic performance. This premise is supported by the observation that students with self-regulatory skills demonstrate effective knowledge and application of learning strategies (Fuentes et al. 2023). These students not only reflect on their own learning process but also have strategies to monitor, control, and adjust their behavior to achieve desirable academic performance (Lourenço and Paiva 2016).

To enhance SRL skills, teachers must reflect on the teaching and learning processes, recognizing learning as a personal experience where the student must be actively engaged in an autonomous, informed, and dedicated manner (Zimmerman 2008). Thus, the primary role of teachers will be to help students take responsibility for their learning process.

Alliprandini et al. (2023) highlight the growing need to teach students how to use the vast amount of information available, empowering them for autonomous learning. Developing this skill is intrinsically linked to mastering SRL. In this context, students must plan, organize, monitor, and evaluate their learning processes to achieve their goals. The authors note that, along this path, students build a personalized learning system to set objectives, devise action plans, and optimize their development. With well-developed self-regulatory skills, students can strategically analyze, set appropriate goals, and manage their thoughts efficiently (Fuentes et al. 2023).

Thus, the research underscores the importance of SRL in goal setting, planning, and self-regulation, which are essential components for academic success (Schunk and Zimmerman 2023). Promoting and encouraging effective SRL processes not only improve students’ academic performance but also foster the development of vital skills for long-term success. This holistic perspective highlights the significance of self-directed learning in the academic and personal development of students.

5.2. Self-Regulated Learning and Volitional Control (H2)

Regarding hypothesis H2, the findings showed that students who exhibit more effective self-regulation in their learning tend to employ a greater number of volitional control strategies. This finding is consistent with the theoretical foundation present in the literature (Frison et al. 2021; Silva and Alliprandini 2020; Silva and Bizerra 2022; Vieira et al. 2021).

In general terms, it can be stated that a student who considers themselves self-regulated uses a greater number and variety of volitional control strategies. These correspond to the techniques and methods applied to guide and control their actions and behavior in line with their goals and intentions, even when faced with obstacles or distractions (Rodríguez-Guardado and Juárez-Díaz 2023). These strategies are crucial for self-discipline and persisting in challenging or long-duration tasks.

Therefore, students develop a greater ability to stay focused on their established goals when they have well-developed volitional strategies (Boekaerts and Cascallar 2006). These volitional skills are essential for meeting the social norms and expectations inherent to the role of a student, including responsibility, the ability to collaborate in groups, and alignment with the teacher’s expectations.

These strategies manifest in strong work habits, evident both in school activities and in those outside the academic environment, including personal commitments undertaken by students (Fuentes et al. 2023). In the present study, although item vcsq5—which questions “thinking that, even if I skip class, I won’t enjoy it because I won’t be doing what I should”—scored the lowest in the sample (see Table 1), it reveals a crucial attitude for students’ volitional control. This suggests that, even when faced with distractions, students can maintain focus and direct their effort towards the task, thereby facilitating learning processes (Vera 2022).

5.3. Volitional Control and Academic Performance (H3)

Concerning Hypothesis H3, it was confirmed that students who choose more volitional control strategies achieve better academic performance. Volitional control, as one of the three cyclical phases of SRL (Zimmerman 2002), is characterized by the execution of the task set by the student. In this phase, the student seeks to improve their performance through self-control, which involves using learning techniques and strategies, as well as self-observation, which entails recording and analyzing their progress and setbacks. Typically, at this stage, various strategies and techniques are applied, and performance feedback and records are accessed. This process allows the student to monitor their success and identify the need for adjustments to achieve their goals.

According to Leite (2008), volitional control strategies aim to evaluate the processes occurring during the actions a student undertakes to achieve their goals. These strategies can be divided into two distinct processes. The first involves self-instructions, mental imagery, attention focusing, and strategies applied during task execution, as well as supporting students to concentrate on activities and maximize their efforts. The second process focuses on the attention the student pays to specific aspects of their performance, the associated circumstances, and the results obtained. The ability of students to maintain their intentions and their level of competence when facing difficulties is strongly related to access to volitional strategies (Vermeer et al. 2000).

These observations highlight how volitional control strategies help students develop crucial skills that enhance academic performance and more effectively manage their educational responsibilities.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Although the current study presents interesting results and significant contributions, its implications should be considered cautiously due to several limitations. While the proposed model includes theoretically relevant variables for explaining students’ academic performance, it is essential for future research to diversify the sample type by considering a multilevel study.

Moreover, all data were obtained through self-report questionnaires, which may not be sufficient to capture real-time responses in teaching and learning contexts. In retrospective analyzes, responses may be influenced by the individual’s memory and various cognitive biases, as the process relies on their recollection of past events. Consequently, future research should explore academic performance using qualitative methodologies, such as interviews or focus groups, examining students with a history of sustained success over time and those with repeated failures to compare possible differences. Although the proposed model focused on the central theoretical relationships between self-regulated learning, volitional control, and academic performance, an important limitation is the exclusion of student characteristics, such as gender, socioeconomic status, and motivation, which could help control for confounding variables. Future studies could incorporate these variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing academic performance.

From the constructed theoretical model, it was possible to predict about 38% of the variance in academic performance, resulting in a partial representation of the investigated context. This is because the processes involving SRL and volitional control are quite complex, encompassing numerous factors that are not easily captured through a questionnaire. This significant unexplained variance in students’ academic performance suggests the possible existence of other important predictor variables that should be incorporated into future research. Although this study was conducted with a substantial sample (n = 647), it is not intended for this contribution to be generalizable to the entire school population at this educational level. The main aim is to contribute to a better understanding of the implications of the constructs analyzed across different school years and, above all, to stimulate further research on this topic.

6. Conclusions

The analysis of successive OECD (2023) reports reveals an urgent need to identify variables that can predict students’ academic performance. Studies in the educational field emphasize the importance of investigating factors that enhance student engagement across cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions (Callan et al. 2022). From the theoretical framework on academic performance, it is evident that the crucial difference between successful students and those who struggle lies in their ability to structure volitional control and the self-regulation processes they adopt.

Understanding our students deeply and adopting differentiated methodologies and strategies that address their needs is urgently necessary. To achieve this goal, it is essential to integrate SRL and volitional control processes into pedagogical practices. SRL enables students to actively participate in their learning process, developing essential skills to set goals, monitor progress, and adjust strategies as needed. On the other hand, volitional control strategies are crucial in helping students maintain focus and persist in the face of difficulties.

Ensuring that all students, regardless of their differences and difficulties, reach their full potential requires a deep understanding and effective application of these constructs in the classroom. By integrating these approaches, educators can foster a more personalized and effective learning environment. Such an environment not only addresses the individual needs of students but also prepares them for academic success.

In summary, it is acknowledged that educational institutions bear both the responsibility and the capacity to play a decisive role in promoting and enhancing their students’ education. To achieve this goal, a deep understanding of the factors that influence and shape the teaching and learning process is essential, with particular emphasis on motivational components, self-regulation processes, and volitional control, as these are fundamental dimensions for promoting the quality of learning and developing autonomous, self-regulated, and academically competent students. In this context, it is crucial that pedagogical practices are intentionally directed towards developing these competencies, creating learning environments that foster autonomy and active student engagement. Furthermore, educational policies and training initiatives should support teachers in effectively integrating these principles into everyday school practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L., M.O.P. and S.V.; methodology, A.L. and S.V.; software, A.L. and S.V.; validation, A.L., M.O.P. and S.V.; formal analysis, A.L., M.O.P. and S.V.; investigation, A.L., M.O.P. and S.V.; resources, A.L. and S.V.; data curation, A.L., M.O.P. and S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L., M.O.P. and S.V.; writing—review and editing, A.L., M.O.P. and S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the school directors, the participating students’ guardians and the students. As this study did not involve any physical or psychological intervention with the students, but only applied self-administered questionnaires that do not assess sensitive variables (violence, sexual behavior, substance use, etc.) likely to emotionally mobilize the students, it did not require the Institutional Review Board Statement.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alliprandini, Paula Mariza Zedu, Deivid Alex dos Santos, and Sueli Édi Rufini. 2023. Autorregulação da aprendizagem e da motivação em diferentes contextos educativos: Teoria, aprendizagem e intervenção. Londrina: EDUEL. Available online: https://www.eduel.com.br/autorregulac-o-da-aprendizagem-e-motivac-o-em-diferentes-contextos-teoria-pesquisa-e-intervenc-o.html (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Arbuckle, James L. 2022. IBM®, SPSS®, Amos™ 29 User’s Guide. Armonk: IBM. [Google Scholar]

- Arcoverde, Angela Regina dos Reis, Evely Boruchovitch, and Natália Moraes Góes. 2022. Programa de intervenção em autorregulação da aprendizagem: Impacto no conhecimento e nas percepções de estudantes de licenciatura. Revista de Educação Campinas 27: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1986. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 4: 359–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2002. Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology: An International Review 51: 269–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2008. An agentic perspective on positive psychology. In Positive Psychology: Exploring the Best in People (Vol. 1). Discovering Human Strengths. Edited by Shane J. Lopez. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 167–96. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-13953-009 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Boekaerts, Monique, and Eduardo Cascallar. 2006. How far have we moved toward the integration of theory and practice in self-regulation? Educational Psychology Review 18: 199–210. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-07687-001 (accessed on 18 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Brown, Timothy. 2015. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. Available online: https://www.guilford.com/books/Confirmatory-Factor-Analysis-for-Applied-Research/Timothy-Brown/9781462515363 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Byrne, Barbara. 2016. Structural Equation Modeling With AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; New York: Routledge. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315757421/structural-equation-modeling-amos-barbara-byrne (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Callan, Gregory L., Lisa DaVia Rubenstein, Tyler Barton, and Aliya Halterman. 2022. Enhancing motivation by developing cyclical self-regulated learning skills. Theory Into Practice 61: 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, Angela L., and Martin E. P. Seligman. 2005. Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychological Science 16: 939–44. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=cdbd0cb867de883fbc7af456a42b73b9423f4e51 (accessed on 27 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- EDUSTAT. 2024. Taxa de retenção ou desistência por nível de ensino; Porto: Fundação Belmiro de Azevedo. Available online: https://www.edustat.pt/detalhes-infostat?id=28 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Fernandes, Graziela Nunes Alfenas, and Stela Maris Aguiar Lemos. 2020. Motivação para aprender no ensino fundamental e a associação com aspectos individuais e contextuais. CoDAS 32: e20190247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, Sara, and Christine DiStefano. 2013. Nonnormal and categorical data in structural equation models. In A Second Course in Structural Equation Modeling. Edited by Gregory R. Hancock and Ralph O. Mueller. Charlotte: Information Age, pp. 439–92. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-01991-011 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Frison, Lourdes Maria Bragagnolo, Ana Margarida Veiga Simão, Paula da Costa Ferreira, and Paula Paulino. 2021. Percursos de estudantes da Educação Superior com trajetórias de insucesso. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação 29: 669–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frison, Lourdes Maria Bragagnolo, and Evely Boruchovitch. 2020. Autorregulação da aprendizagem: Modelos teóricos e reflexões para a prática pedagógica. In Autorregulação da aprendizagem: Cenários, desafios, perspectivas para o contexto educativo. Edited by Lourdes Maria Bragagnolo Frison and Evely Boruchovitch. Petrópolis: Vozes, pp. 17–30. Available online: https://www.fe.unicamp.br/noticias/lancamento-do-livro-autorregulacao-da-aprendizagem-cenarios-desafios-perspectivas-para-o (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Fuentes, Sonia, Pedro Rosário, Monona Valdés, Alejandro Delgado, and Carlos Rodríguez. 2023. Autorregulación del Aprendizaje: Desafío para el Aprendizaje Universitario Autónomo. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva 17: 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganda, Danielle Ribeiro, and Evely Boruchovitch. 2019. Intervenção em autorregulação da aprendizagem com alunos do ensino superior: Análise da produção científica. Estudos Interdisciplinares em Psicologia 10: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Braojos, Calixto. 2015. Future time orientation and learning conceptions: Effects on metacognitive strategies, self-efficacy beliefs, study effort and academic achievement. Educational Psychology 35: 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, Allyson Fiona, Sanna Järvelä, and Mariel Miller. 2011. Self-regulated, co-regulated, and socially shared regulation of learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance. Edited by Barry J. Zimmerman and Dale H. Schunk. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 65–84. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2011-12365-005 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2019. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed. Andover: Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781473756540. Available online: https://www.cengage.uk/c/multivariate-data-analysis-8e-hair-babin-anderson-black/9781473756540/?searchIsbn=9781473756540 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Helsinki Declaration. 2013. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310: 2191–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Li-Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cut off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, Karl Gustav, and Dag Sörbom. 1983. LISREL—6 User’s Reference Guide. Mooresville: Scientific Software. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, Rui. 2008. Estratégias de controlo volitivo e processos de auto-regulação em alunos do terceiro ciclo. Tese de Mestrado. Braga: Universidade do Minho. [Google Scholar]

- Lohr, Sharon L. 2022. Sampling: Design and Analysis; Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC. Available online: https://api.pageplace.de/preview/DT0400.9781000478235_A41909324/preview-9781000478235_A41909324.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Lourenço, Abílio Afonso, and Carla Maria Leite Nogueira. 2014. Perceções sobre as abordagens à aprendizagem: Estudo de variáveis psicológicas. Educação e Filosofia 28: 323–72. Available online: http://www.seer.ufu.br/index.php/EducacaoFilosofia/article/view/21649/15265 (accessed on 12 February 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lourenço, Abílio Afonso, and Maria Olímpia Almeida Paiva. 2016. Autorregulação da aprendizagem uma perspetiva holística. Ciências & Cognição 21: 33–51. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303766017_Autorregulacao_da_aprendizagem_uma_perspectiva_holistica (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Lourenço, Abílio Afonso, and Maria Olímpia Almeida Paiva. 2024a. Self-regulation in academic success: Exploring the impact of volitional control strategies, time management planning, and procrastination. International Journal of Changes in Education 1: 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, Abílio Afonso, and Maria Olímpia Paiva. 2024b. Academic performance of excellence: The impact of self-regulated learning and academic time management planning. Knowledge 4: 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, Abílio Afonso. 2008. Processos auto-regulatórios em alunos do 3.º Ciclo do Ensino Básico: Contributo da auto-eficácia e da instrumentalidade. Tese de doutoramento. Braga: Instituto de Educação e Psicologia da Universidade do Minho. [Google Scholar]

- MacCann, Erin J., and Turner Jeannine E. 2004. Increasing student learning though volitional control. Teachers College Record 106: 1695–1714. Available online: https://www.sfu.ca/~jcnesbit/EDUC220/ThinkPaper/MccannTurner2004.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Marôco, João. 2021. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics, 8th ed. Lisboa: Report Number Lda. Available online: https://www.bertrand.pt/livro/analise-estatistica-com-o-spss-statistics-joao-maroco/24699154 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- McDonald, Roderick P., and Moon-Ho Ringo Ho. 2002. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods 7: 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2023. Report of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA 2023); Paris: OECD. Available online: https://eco.sapo.pt/2023/12/05/pisa-o-estado-da-educacao-em-cinco-graficos/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Parveen, Amina, Shazia Jan, Insha Rasool, Raja Waseem, and Rameez Ahmad Bhat. 2023. Self-Regulated Learning. In Handbook of Research on Redesigning Teaching, Learning, and Assessment in the Digital Era. Edited by Eleni Meletiadou. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 388–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, Paul R. 2000. The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation. Edited by Monique Boekaerts, Paul Pintrich and Moses Zeidner. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 451–502. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780121098902500433 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Ribeiro, Filomena. 2011. Motivação e aprendizagem no contexto escolar. Profforma 1: 1–5. Available online: https://www.cefopna.edu.pt/revista/revista_03/pdf_03/es_05_03.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Richardson, Michelle, Charles Abraham, and Rod Bond. 2012. Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 138: 353–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Guardado, María, and Catalina Juárez-Díaz. 2023. Relación entre estilos de aprendizaje y estrategias volitivas en estudiantes universitarios de lenguas extranjeras. Revista Caribeña de Investigación Educativa 7: 123–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, Pedro, Abílio Lourenço, Maria Olímpia Paiva, Jose Carlos Núñez, Júlio González-Pienda, and António Valle. 2010. Avaliação Psicológica. Instrumentos validados para a população portuguesa. Inventário de processos de auto-regulação da aprendizagem (IPAA); Edited by Miguel Manuel Gonçalves, Mário Ricardo Simões, Leandro Silva Almeida and Carla Machado. Coimbra: Almedina, pp. 159–74. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260392168_Inventario_de_processos_de_auto-regulacao_da_aprendizagem_IPAA#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Schunk, Dale H., and Barry J. Zimmerman. 2012. Handbook of Psychology, 2nd ed. New Jersey: Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, Dale H., and Barry J. Zimmerman. 2023. Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance: Issues and Educational Applications; New York: Taylor & Francis. Available online: https://books.google.pt/books/about/Self_regulation_of_Learning_and_Performa.html?id=SLujEAAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Silva, Felipe Araújo, and Ayla Márcia Cordeiro Bizerra. 2022. Percepção de alunos sobre a autorregulação da aprendizagem no ensino médio profissionalizante. Revista Cocar 17: 1–20. Available online: https://periodicos.uepa.br/index.php/cocar/article/%20view/5447 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Silva, Priscilla Maria Marques, and Paula Mariza Zedu Alliprandini. 2020. Autorregulação da aprendizagem de alunos do ensino médio: Um estudo de caso. Revista Cocar 14: 1–18. Available online: https://periodicos.uepa.br/index.php/cocar/article/view/3329 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Vera, Angélica. 2022. Autorregulación en el aprendizaje de estudiantes y su relación con rendimiento académico. Revista Conhecimento Online 2: 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeer, Harriet J., Monique Boekaerts, and Gerard Seegers. 2000. Motivational and gender differences: Sixth-grade students’ mathematical problem-solving behavior. Journal of Educational Psychology 92: 308–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, Maria Do Socorro Tavares Cavalcante, Geida Maria Cavalcanti de Sousa, and José Roberto Andrade Do Nascimento Junior. 2021. Perfil metacognitivo de estudantes universitários e suas estratégias de autorregulação de aprendizagem. Revista de Psicologia: Periódico Multidisciplinar 15: 740–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Barry J. 2002. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory into Practice 4: 64–70. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2 (accessed on 23 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Barry J. 2008. Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal 45: 166–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivich, Beatriz Silva, and Paula Mariza Zedu Alliprandini. 2023. A autorregulação da aprendizagem de alunos do Ensino Fundamental no contexto do ensino remoto. Debates em Educação 15: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).