1. Introduction

Despite the proliferation of intersectionality discourse, few studies have operationalized this framework into research paradigms. Consequently, the literature remains mostly siloed between endeavors to understand social and emotional wellbeing among racial and ethnic minority youth and gender and sexual minority youth. While it is possible to find research on gender and sexuality-diverse Native people, gender or sexuality-diverse people, Indigenous youth, or gender and sexuality-diverse youth, there remains very little scientific understanding of queer, trans, or Two Spirit Native youth (

Soldatic et al. 2022). What is known presents a disturbing trend in health and wellbeing, as the results of the 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health found that the risk of attempting suicide for QT2S Native youth increased as other minority stressors increased, such as housing instability, discrimination, and lack of family acceptance (

Edwards et al. 2024). However, information surrounding these stressors, challenges, and strengths to support social and emotional wellbeing is largely unknown for QT2S Native youth. The present work presents the results of a scoping review surrounding the social and emotional wellbeing of queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth. A total of 27 articles were reviewed to illuminate (a) the current experiences of QT2S Native youth and (b) to provide recommendations for health and mental health providers to better support QT2S Native youth. An additional domain of data and research recommendations emerged during the analysis.

The present work follows the methodology of queer Mohawk scholar

Marie Laing (

2021) by using the amalgamation of several umbrella terms to create the uber umbrella phrase of “queer, trans, and Two-Spirit (QT2S)” to encompass and collectively delineate those underneath each corresponding umbrella. It is important to note that Indigeneity is not a monolith, with each Native Nation holding their own views, values, and practices surrounding gender and sexuality; however, the present work will utilize the terms Indigenous and Native interchangeably to refer to American Indian and Alaska Native Nations within the so-called United States whenever tribal affiliation is not readily apparent. Similarly, “Two-Spirit” is not a synonym for queer Native or trans Native; rather, Two Spirit is better conceptualized as a community role, spiritual identity, and a larger means for collective organizing (

BlackDeer 2025).

In the spirit of decolonization, I seek to begin this work in a good way. My name is Autumn BlackDeer and I am a sovereign member of the mighty Southern Cheyenne Nation, descendant of Chief Little Face and Sam B. Deer – a sacred arrow keeper, medicine man, and camp crier for our people. I am an Indigiqueer femme,

1 decolonial scholar activist, and ancestor-in-training. All too often, marginalized communities are only represented as participants and respondents in research; I write the present work from an Indigiqueer perspective, holding both my queerness and Indigeneity simultaneously as I navigate colonial academia. I humbly present this work for my Indigenous and queer kin and the future generations of QT2S folx.

2Nétónetomóhtahe? How is your health?

There are rich queer Indigenous traditions across Turtle Island

3 in which those with fluid gender roles were highly revered, holding ceremonial roles such as spiritual healers and helpers (

Ansloos et al. 2021). Similarly, Indigenous sexuality was not embedded within gender ideology. However, settler colonialism interrupted many of these traditional views of gender and sexuality among many Native Nations, resulting in suppression and erasure. Traditional acceptance and inclusion were replaced with Christian mandates of shame and condemnation (

Asher BlackDeer,

2024).

Today, QT2S Native folx often face a double bind, referred to as compound colonialism, and are left to choose between experiencing racism in queer spaces or homophobia/transphobia in Native spaces (

Asher BlackDeer,

2024). Queer, trans, and Two Spirit Indigenous folx are often forced to choose between honoring their ethnic identity or their gender/sexual identity. Further, Indigenous queer, trans, and Two Spirit youth face structural discrimination and marginalization as a result of their intersectional identities, from age, gender, sexuality, and Indigeneity (

Spurway et al. 2022). The question becomes, when do queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth ever get the chance to truly flourish?

1.1. Social and Emotional Wellbeing

Previous scholarship on global Indigenous LGBTQA+

4 youth has defined social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) as a holistic concept which integrates understandings of the importance of Indigenous strengths, communities, sovereignty, and cultures, as well as contending with the impact of intergenerational trauma, racism, and stigma (

Spurway et al. 2022). Similarly, a systematic review of wellbeing among Indigenous peoples from Canada, Aotearoa, and the United States found the most common aspects of wellbeing were identity, connection, balance, and self-determination (

Gall et al. 2021). Global Indigenous communities converge in holistic conceptions of health and wellbeing. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander scholars in Australia call for the recognition that health is a culturally bound phenomenon that should be at the center of health and wellbeing endeavors for Indigenous communities (

Biles et al. 2024).

Scholarly research on the social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous gender and sexuality-diverse youth is practically non-existent (

Soldatic et al. 2022). Studies focused on LGBTQA+ health rarely include Indigenous respondents, and studies focused on Indigenous health rarely measure sexual orientation or gender identity (

Thomas et al. 2022). Studies that do address these identities often fail to provide an analysis across these axes as they intersect—being Indigenous

and queer, trans, or Two Spirit

and young—with many studies only dealing with two of these dimensions (

Spurway et al. 2022, p. 140). Thus, the inclusion criteria for the present review require an analysis of all three.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

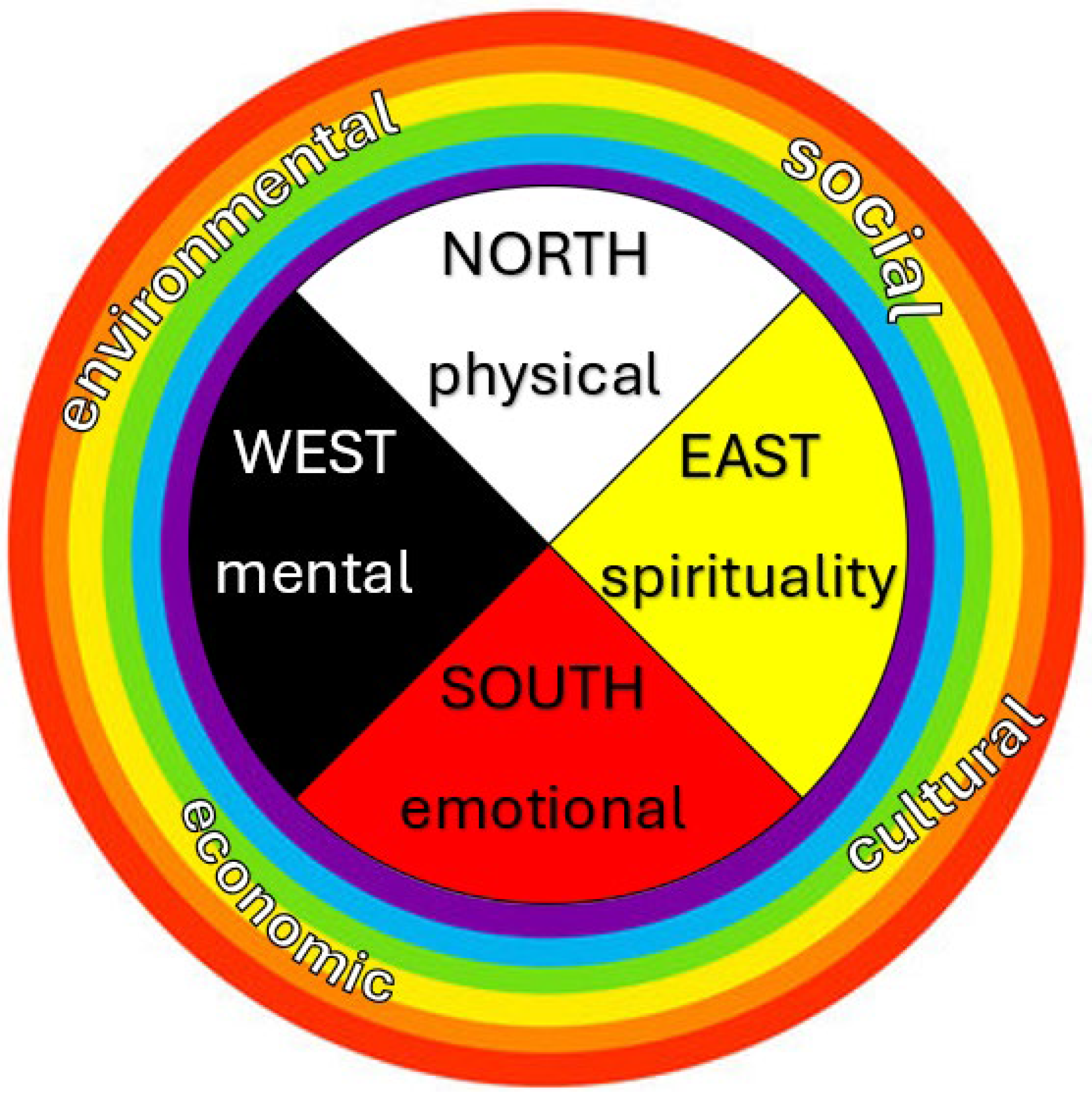

The present study is guided by an ecological medicine wheel framework (

Figure 1) informed by traditional teachings of the Southern Cheyenne Nation, systematic reviews of health risks for Native youth (

Burnette and Figley 2016) and protective (

Henson et al. 2017) factors, and global Indigenous LGBTQA+ scholarship on SEWB (

Thomas et al. 2022;

Spurway et al. 2022). Scholars note that much of the research focuses on poor mental health and tends to pathologize Indigenous and queer, trans, or Two Spirit people, placing the onus on an individual’s personal characteristics and identity rather than structural aspects of colonial society (

Spurway et al. 2022;

Fetter et al. 2025). To move beyond deficit-based scholarship, the present study will include a breadth of health and wellbeing concepts for QT2S Native youth in the search strategy.

In alignment with the traditional teachings of the present author, the Southern Cheyenne Nation medicine wheel begins in the East, the direction of the rising sun, represented by the color yellow. The East represents the spirituality domain of SEWB, including concepts such as balance, body, mind, spirit, and emotions. The South is the emotional realm, typically associated with summertime, a time of growth and maturity in life and relationships, and is symbolized by the color red. The South represents the emotional domain of SEWB including concepts such as relationships, and social and emotional wellbeing. The West is the mental domain, focusing on mental strength and reason. Represented by the color black, reminding us of the transition from light to dark, day to night, and life to death, the West includes domains associated with mental health, traditional knowledges, and ceremony. Finally, the North represents physical aspects of health such as health services. Represented by the color white, the Northern domain represents a place of healing, symbolized by snow in the wintertime. It is a time of renewal. Around the medicine wheel are domains of (a) environmental—such as the land, water, and obligations; (b) social—such as family and cultural wellbeing; (c) economic—including services, treatment, racism, stigma, and discrimination; and finally, (d) cultural—domains such as ceremony, tradition, knowledge, sovereignty, and language. These domains are each included in the search terms delineated below.

3. Results

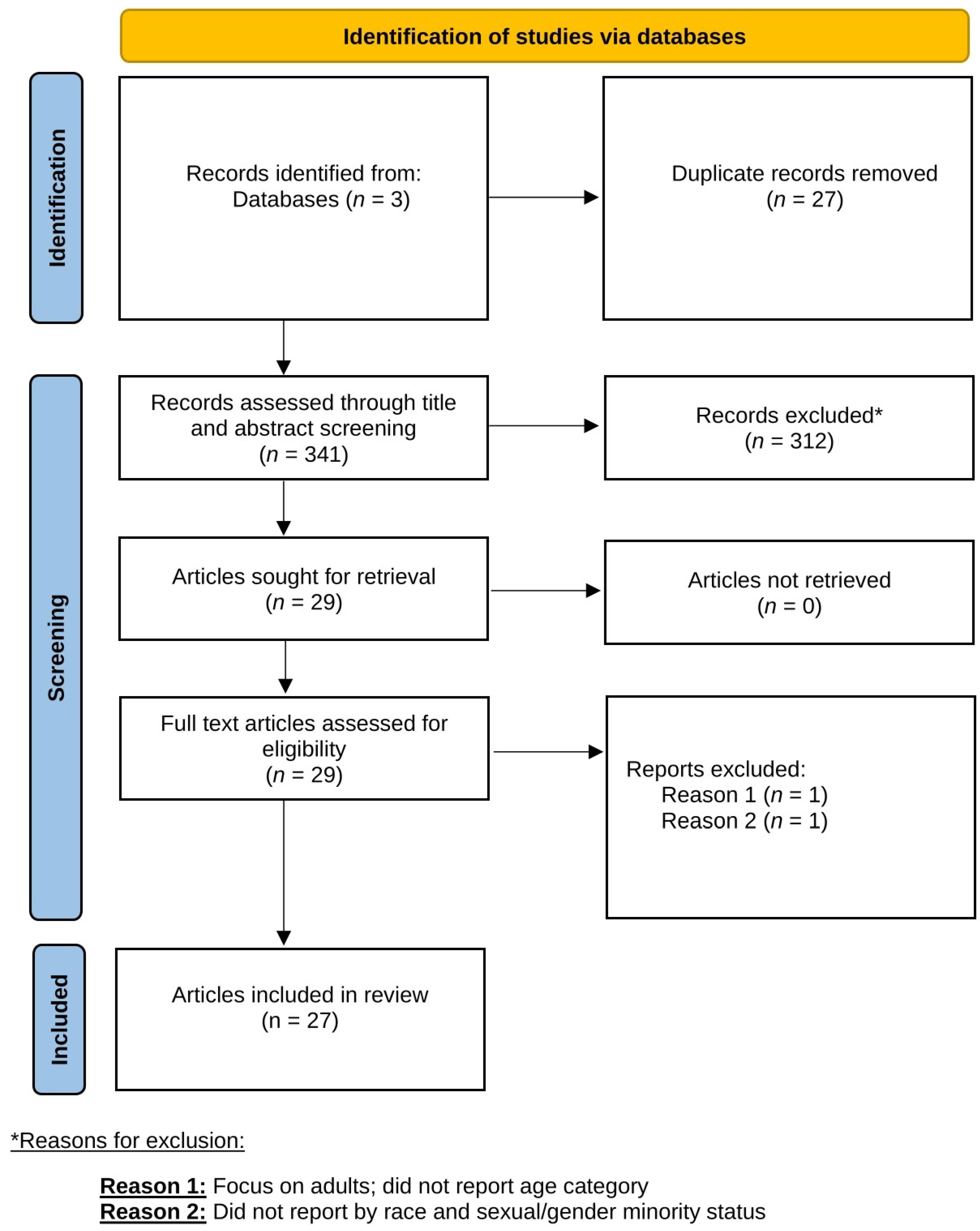

A total of 27 articles were included and reviewed: 22 empirical and 5 commentary, perspective, and policy statements. The majority of empirical articles were quantitative in nature (73%), with the remaining studies using qualitative and mixed methods; a full breakdown can be seen below in

Table 1. Several quantitative studies also utilized similar national datasets, with 18% using the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS;

Baiden et al. 2020;

Fix et al. 2022;

Schuler et al. 2023;

Bostwick et al. 2014), 9% using the SOGI-Q Health Study (

Mallory et al. 2021;

Mallory and Russell 2021), and others using familiar surveys such as the Healthy Minds Study (

Thulin et al. 2023) and the National Survey on Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People (

Hobaica et al. 2024). Qualitative methods included both in-depth (

Schmitz and Charak 2022) and semi-structured interviews (

Angelino et al. 2020b), focus group discussions (

Agénor et al. 2022;

Angelino et al. 2020b), and an arts-based expressive poetics method (

Beltrán et al. 2023). Of the five included non-empirical articles, three were commentaries (

Angelino and Bell 2023;

Benson 2020;

BlackDeer 2025), one was a policy statement to the American Academy of Pediatrics (

Bell et al. 2021), and one described toolkit development for trans and Two Spirit youth, relatives, and providers (

Angelino et al. 2020a).

3.1. Current Experiences

To answer the first research question, the following section delineates several axes of current knowledge surrounding the lived experience of queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth, including QT2S Native pride in their identity; health disparities and healthcare experiences; and the expression of QT2S Native youth’s desires.

While typically compared to white LGBTQ peers, three included studies found similarities in the quantitative comparisons of QT2S Native youth and their cishet Native counterparts (

Barney 2004;

Bostwick et al. 2014;

Skye et al. 2021). In their study of gay adolescent males, no statistically significant differences were found in drug and alcohol use and access to healthcare when compared to hetero Native male adolescents (

Barney 2004). Similarly, an analysis of the 2005 and 2007 YRBSS found that Indigenous youth fared worse than other racial and ethnic groups on several outcomes regardless of their sex or sexual minority status (

Bostwick et al. 2014). Further,

Skye et al. (

2021) found a similar prevalence of sexual health behaviors (such as vaginal and oral sex, condom use, and cigarette smoking) between heterosexual and QT2S Native youth. These results suggest that certain domains of social and emotional wellbeing such as drug and alcohol use, healthcare access, and sexual health may be similarly worse for all Indigenous youth regardless of gender or sexuality.

3.2. QT2S Native Pride

Both quantitative and qualitative scholarship illuminated heartening data surrounding QT2S Native youth pride in their identity as queer, trans, and Two Spirit. In a study of 119 2SLGBTQ+ Native youth, 98% of respondents stated they were proud to be Two Spirit, with 93.4% agreeing that being Two Spirit helped them do good things for their community (

Angelino et al. 2024). These results demonstrate the connection QT2S Native youth have to their Indigenous communities, Two Spirit communities, and traditional practices overall. Similarly,

Beltrán et al. (

2023) engaged five Native, Indigenous, and Indigenous Latinx

5 2SLGBTQ+

6 youth and young adults aged 14–23 in an expressive poetics research endeavor. Authors collaborated with participants to create a poem through poetic analysis from selected salient words and ideas, thus organizing QT2S qualitative data into poetry. Poem 3 below illuminates QT2S Native youth’s strength in identity:

- “I see myself strong

- Dyke. Two-Spirited. Gay.

- Lesbian. Queer. Masculine.

- Feminine. Whatever.

- So Native.

- It’s hard

- Putting a label on

- Intersections…”

Speaking to the intersection of their Indigenous and queer identity, one queer Two Spirit female participant stated, “Because I’m not

just Indigenous every day. Like [not]

only Indigenous. I’m also queer, I’m also Two Spirit, everything else; and so it plays into like everything that I do”. (

Beltrán et al. 2023, p. 9, emphasis original).

Several scholars noted the lack of positive research on strengths QT2S Native youth have, thus further marginalizing one of the most silenced and structurally minoritized groups in the US (

Angelino et al. 2024;

BlackDeer 2025;

Edwards et al. 2024). While few studies measured positive aspects of health, Edwards and colleagues measured several aspects of mattering and belonging. In their work with Lakota QT2S youth,

Edwards et al. (

2024) found that 88% of participants felt that they mattered to their communities and families, with an additional 82% reporting a sense of queer community belonging. While meant to capture both the risk and protective factors for suicide among sexual minority youth, less than 30 participants identified as QT2S Native youth, leading to a lack of significant results or the ability to run analyses altogether (

Mallory et al. 2021).

3.3. Health Disparities

Predictably, the vast majority of the included studies reported health disparities (n = 15). As part of their policy statement to the American Academy of Pediatrics,

Bell et al. (

2021) illuminated that QT2S Native youth experienced exponential increases in the risk of health disparities. Empirical studies further illuminated these experiences.

Reed et al. (

2022) found that non-sexual and gender minority Native youth reported better overall physical and mental health than SGM Native youth (

Reed et al. 2022). Even providers for QT2S Native youth health commented on the nature of these health disparities, citing an outdated medical system which perpetuates colonial norms as a key contributor to these health disparities and further barriers to health and healthcare (

Angelino et al. 2020b).

3.3.1. Mental Health

Several quantitative studies solely reported on health disparities, particularly mental health disparities, from as early as the 1980s through the present day (2020s). In their commentary on developing a scientific understanding of QT2S Native youth mental health,

BlackDeer (

2025) outlined mental health disparities across diagnoses of depression and anxiety, trauma and PTSD, and suicidality.

Schmitz and Charak’s (

2022) qualitative work with QT2S Native youth expanded on these trauma-related health disparities, finding that (1) respondents emphasized the enduring nature of trauma, (2) trauma served as a major turning point in QT2S Native youth’s lives, and (3) there is an intersectional and cumulative nature of trauma. In their qualitative work with QT2S Native youth health providers, one non-Native behavioral health provider stated: “When people say that you know, ‘Oh that was history, just get over it’, they don’t understand that the trauma is still walking around. That the trauma is still happening, and that the kids are now experiencing it just as much as their brothers or their fathers and grandfathers etc. in schools. The discrimination they’re facing is astronomical”. (

Angelino et al. 2020b, p. 634). These studies illuminate the ways in which both patients and providers recognize the impact of trauma and colonialism on QT2S Native youth’s health.

Several studies used the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) to analyze subsamples of QT2S Native youth. In the largest examination of YRBSS data,

Schuler et al.’s (

2023) pooled data from the 2005–2019 YRBSS administrations culminated in 3621 QT2S Native youth: the largest quantitative sample of QT2S Native youth in the entire review. The results of this combination found that bisexual Native youth had the highest prevalence of suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts compared to their heterosexual Native counterparts (

Schuler et al. 2023). In their analysis of the 2017 YRBSS of 13,697 adolescents aged 14–18,

Baiden et al. (

2020) found that of the 228 Native LGBTQ+ respondents, Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander bisexual adolescents had 2.44 higher odds of making a suicide attempt. Again,

Bostwick et al. (

2014) found similar patterns in 2005 and 2007 YRBSS analyses of 276 QT2S Native youth, noting that in comparison to their heterosexual peers, QT2S Native youth were statistically more likely to have planned or attempted suicide and self-harmed.

These patterns surrounding QT2S Native suicidality illuminated throughout YRBSS were also mirrored in Barney’s examination into gay male Native adolescents and

Thulin et al.’s (

2023) Healthy Minds Study. The results of the Indian Adolescent Health Survey, conducted from 1988 to 1990, found that 65 gay Native adolescent males were more likely to contemplate and attempt suicide than their heterosexual Native male peers (

Barney 2004). These gay Native male adolescents had lower life satisfaction and a greater history of being depressed and sad than their heterosexual peers (

Barney 2004). More recently, data from the 2017–2020 Healthy Minds Study found that trans and nonbinary Native young adults were three times more likely to report suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts (

Thulin et al. 2023).

3.3.2. Violence and Discrimination

In addition to mental health disparities,

Edwards et al. (

2021) found that among 68 queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth, sexual minority Native youth were more likely to experience interpersonal violence than their heterosexual Native peers. This measure of interpersonal violence included several concerning experiences such as sexual coercion, rape, incapacitated sex, homophobic teasing, and sexual harassment. Similarly, the results of the Gender Minority Youth Study found that Native gender minority youth experienced higher levels of gender minority prejudice than white gender minority youth (

Jardas et al. 2023). Additionally, compared to their cisgender Native peers, queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth had higher levels of psychosocial distress from experiences such as bullying, violence, family rejection, and homelessness (

Angelino et al. 2020a), while

Edwards et al. (

2024) found that of the 36 Lakota QT2S youth in their study, 51% experienced bullying victimization and 64% experienced teen dating violence. Finally,

Fix et al. (

2022) found similar patterns in teen dating violence, reporting that queer Native girls were 3.2 times more likely to be in a physical fight compared to 1.3 of heterosexual Native girls and 0.57 of the entire queer Native subsample. These five studies illuminate important areas for intervention to better support the social and emotional wellbeing of QT2S Native youth. Addressing these experiences of violence and discrimination can provide QT2S Native youth with the space and opportunity to thrive.

3.4. Healthcare Experiences

Angelino and colleagues offer a suite of publications that speak to the health and healthcare experiences of queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth, offering a total of four included studies in the present review (

Angelino and Bell 2023;

Angelino et al. 2020a;

Angelino et al. 2020b;

Angelino et al. 2024), and demonstrating the ways in which QT2S Native youth have higher rates of disease and substance use due to a lack of access to care and higher levels of discrimination (

Angelino et al. 2020a). Their commentary noted common barriers to care for QT2S youth such as socioeconomic obstacles, restrictive legislation, distance to healthcare facilities, and a lack of health insurance and family support (

Angelino and Bell 2023). Further, in their survey of 119 QT2S Native youth aged 15–25,

Angelino et al. (

2024) found that half of all participants identified as gender diverse. When asked about their healthcare experiences, 88% noted a scarcity of medical professionals overall, while 70% noted the insufficient amount of mental health providers for QT2S Native youth (

Angelino et al. 2024). One participant stated: “[We need] queer Indigenous health professionals, or those who are competent and enthusiastic to care for us”. (

Angelino et al. 2024, p. 542).

In their commentary on including Two Spirit and LGBTQ+ Native youth in pediatric care,

Angelino and Bell (

2023) spoke to the lack of provider understanding of Native cultures and perspectives, as well as an overall discomfort with gender-affirming care. These shortcomings in health provider competency and awareness were further highlighted in multiple studies both quantitatively and qualitatively within the present work (

Angelino and Bell 2023;

Agénor et al. 2022;

Angelino et al. 2020b).

Agénor et al. (

2022) conducted five focus groups with 19 Black, Latinx, Asian, Native, and other transmasculine (transmasc) young adults of color. Transmasc includes trans men (assigned female at birth) and gender diverse folx that identify with masculinity (nonbinary, gender fluid, gender nonconforming, genderqueer) (

Agénor et al. 2022). The qualitative results showed that one Black and Native agender participant spoke on their reluctance to seek gynecological care, stating, “Because they think about pregnancy. And I’m like, ‘There’s no way I’m getting pregnant at all.’ And just not thinking [about] the possibility that your clients are not straight”. (

Agénor et al. 2022, p. 124). Similarly, a Latinx and Native transmasculine participant explained they knew they were not pregnant and when asked why by the provider, the participant responded, “Well, that person had gotten her testicles removed, so she wasn’t a sperm producing person”. (

Agénor et al. 2022, p. 127). These results were likewise reported on the provider side of these healthcare interactions. In their work with QT2S Native youth health providers, including physicians, nurses, and behavioral health counselors,

Angelino et al. (

2020b) found that providers reported a limited understanding of gender and sexuality within the Indigenous context. Further, only seven providers received specific training on how to care for QT2S patients, and most were uncertain regarding the role they should play in a patient’s gender-affirming journey (

Angelino et al. 2020b).

3.5. QT2S Desires

Perhaps the most exciting illumination from the present work is what seminal decolonial scholar Eve Tuck (Unangax) describes as desire-based research (2009). As previously mentioned, there is a plethora of deficit-based scholarship, especially in regards to Native communities and queer youth. The following section demonstrates QT2S Native youth desires, broadly defined. When presented with a free response space,

Angelino et al. (

2024) reported that QT2S Native youth expressed a desire to create supportive spaces for themselves. These youth also expressed that in order to improve their connection, leadership opportunities should be developed for QT2S Native youth to better support visibility within the community (

Angelino et al. 2024). Similarly, queer, trans, and Two Spirit Indigenous and Indigenous Latinx youth also reported their desire for increased visibility to emphasize the importance of supportive communities and to increase a positive sense of self and a desire for leadership opportunities that recognize QT2S capacity to lead from within (

Beltrán et al. 2023). Finally, in their work with QT2S Lakota youth,

Edwards et al. (

2024) noted that these youth desired for others to stand up for them, again emphasizing the importance of community and belonging. Overall, QT2S Native youth desire supportive spaces in community, visibility, leadership opportunities, and community support and protection. These should be seen as goals for each of us to work towards together. In our sphere of influence, how are we creating safe and supportive spaces for QT2S Native youth? How can we create leadership opportunities in this community? In research? Elsewhere? And ultimately, how can we better support and protect QT2S Native youth? The following section seeks to provide an answer to the latter question in our roles as physicians and behavioral health providers.

3.6. Recommendations for Providers

Several studies provided recommendations for providers to better support queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth, such as (1) increasing provider knowledge of historical context and culturally informed resources, (2) awareness of the role of social support in medical interactions, and (3) participation in policy advocacy.

3.7. Learn Historical Context

Benson’s 2020 commentary about the juvenile justice system speaks to the compound colonialism faced by QT2S Native youth. The so-called justice system has dual goals of making Indigenous youth invisible and making trans youth normative (

Benson 2020). The resulting combination means that good intentions are not enough to help QT2S Native youth overcome these systemic goals in settler colonial justice systems (

Benson 2020).

Hobaica et al. (

2024) reported that QT2S Native youth have the highest rates of arrest and detainment compared to their fellow LGBTQA+ peers. In addition to learning the historic context surrounding Indigenous gender and sexuality perspectives, it is important for providers to stay abreast of intersecting systems of oppression that QT2S Native youth may find themselves in, such as the juvenile justice and child welfare systems.

Further system intersections arise in consideration of the typical Western medical healthcare system. Providers must know the histories of forced sterilizations and paternalistic medical care against Indigenous peoples, especially with contraceptive and sexual health decisions (

Angelino and Bell 2023). Providers for QT2S Native youth described the healthcare system as one that medicalizes and stigmatizes gender and gender identity, while also noting the gaps in cultural training related to Indigenous history, culture, and traditional medicine for physicians and behavioral health providers (

Angelino et al. 2020b). Providers for QT2S Native youth described the system that medicalizes and stigmatizes gender and gender identity (

Angelino et al. 2020b). Others noted the gaps in cultural training related to Indigenous history, culture, and traditional medicine for physicians and behavioral health providers (

Angelino et al. 2020b). Providers must be willing to self-educate and dedicate time to learning how to better care for QT2S Native youth as the medical system is unlikely to change fast enough to meet the needs of these communities (

Angelino et al. 2020b).

3.8. Learn About Culturally Informed Resources

Access to culturally relevant resources can help QT2S Native youth access needed support, help family members and providers offer this support, and improve their mental and physical health overall (

Angelino et al. 2020a). Culturally informed resources such as the Celebrating Our Magic Toolkit and the Paths (Re)membered Project were illuminated in several studies as a way to provide education for providers, patients, and family members, while also supporting QT2S Native youth’s social and emotional wellbeing (

Angelino and Bell 2023;

Reed et al. 2022). The Celebrating Our Magic Toolkit provides the five As for Healthcare Providers, which include the following: (1) acknowledge—assess one’s own biases in relation to Native communities and gender diversity; (2) ask—ask youth about their gender identity and pronouns; (3) affirm—discuss how to create safe spaces for QT2S Native youth in clinical environments; (4) advocate—center allyship and support for gender diverse Indigenous youth; and (5) address—provide resources and recommendations for Native youth and fellow providers (

Angelino and Bell 2023). The toolkit also addresses several gaps in gender-affirming care such as the lack of historic Indigenous perspectives on gender, confusion on definitions, and provider education on gender-affirming care, and provides Indigenous QT2S role models and stories from Native youth about their own gender-affirming journeys (

Angelino et al. 2020a). Overall, these studies emphasized the importance of culturally relevant holistic health resources for QT2S Native youth (

Reed et al. 2022).

3.9. Bring a Buddy

Research has demonstrated that QT2S Native youth with supportive family and healthcare providers had anxiety and depression levels similar to those of their cis siblings and peers and were less likely to experience depression, substance use, and suicidal ideation altogether (

Angelino et al. 2020a). Conversely, providers for QT2S Native health noted the challenges youth faced in fitting in at school or religious groups, difficulties finding support from elders and community members, and an overall inability to find a safe environment for their identities to develop (

Angelino et al. 2020b). One participant shared, “To find a place that feels safe, both gender-affirming and culturally affirming, there’s not like a list… there’s no website to go to…”. Similarly, a Black, Native, and multiracial nonbinary participant recommended bringing company with them to medical appointments, stating, “People act better when they know people are watching them. And so I tell people, ask your friends to go with you to the doctor. If you’re comfortable enough, having someone there with you gives you that confidence to stand up for what you know you need”. (

Agénor et al. 2022, p. 128). Ultimately, QT2S Native youth are more likely to have positive adult health outcomes when they have higher self-esteem, greater levels of social support, and better overall general health (

Angelino et al. 2020a); therefore, bringing trusted companions to medical appointments or other large system-level interactions can be a way to create safer spaces for QT2S Native youth.

3.10. Advocacy

Lastly, providers can participate in advocacy efforts to protect rights and access to care for gender diverse youth (

Angelino and Bell 2023). Building upon knowledge of the historic context, providers can also advocate in policy spaces to share the history of gender diversity to dispel myths related to the trendiness of gender diversity (

Angelino and Bell 2023). One Native physician caring for QT2S Native youth shared: “We should be fighting on a policy and advocacy level for equal rights and equitable rights for all people including youth who are gender non-conforming”. (

Angelino et al. 2020b). Overall, there is a need for systemic policy change to reduce justice involvement, especially among QT2S Native youth (

Hobaica et al. 2024), as well as reducing adverse system interactions altogether.

3.11. Data and Research

While not articulated as a key focus of the present scoping review, three key areas of data and research for QT2S Native youth emerged and are subsequently included here. Previous unsuccessful attempts to identify the literature on queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth have illuminated the need for a better understanding of the nature and type of evidence available (

Thomas et al. 2022). Further, in their commentary on creating a scientific understanding of QT2S Native youth mental health,

BlackDeer (

2025) noted several methodological issues and subsequent recommendations for researchers in regard to sampling, data, and evidence-based practice. Overall, Indigenous communities often face data erasure in health fields as Native health data are often not systemically collected and reported (

Fetter et al. 2025).

BlackDeer (

2025) stated that from a sheer volume perspective, there is an outstanding need for more research on QT2S Native youth’s health experiences. This lack of research hinders the ability to develop affirming, culturally grounded strengths-based initiatives (

Edwards et al. 2024).

Angelino and Bell (

2023) recommended that providers can create affirming environments and medical care while also promoting QT2S research.

3.12. Problems with Measurement

Sampling. Scholars consistently note an overrepresentation of white samples in LGBTQ research (

Thomas et al. 2022), as well as a lack of settler commitment to challenge racism and colonialism in LGBTQ studies at large (

BlackDeer 2025). To remedy this, the present work included scholarship that addressed all three axes of race, gender and sexuality, and youth status. Unfortunately, several included studies reported less than 100 QT2S Native youth respondents, as highlighted in red in the table below. Having less than 100 respondents in any multivariate statistical analysis is a violation of statistical assumptions, thus indicating that the results may not be valid or reliable. While the present author appreciates the illumination of QT2S Native youth prevalence in these included studies, it is readily apparent that greater data advocacy is needed.

Indigeneity. Several quantitative articles were included in the present review due to their inclusion of QT2S Native respondents but failed to meet the substantive sample size for the statistical analysis, as seen in

Table 2 (

Mallory and Russell 2021;

Mereish et al. 2022;

Turnamian and Liu 2023;

Zongrone et al. 2022).

Mereish et al. (

2022) evaluated data from the LGBTQ National Teen Survey with a specific subsample of sexual and gender minority youth of color; however, due to small sample numbers, regression models were not run for groups that did not meet the criteria. Similarly,

Mallory and Russell (

2021) conducted a longitudinal survey of sexual minority youth of color, reporting a total of 4% of respondents identifying as QT2S Native youth. Unfortunately, no statistically significant differences were found among this subsample, which can be attributed to several possibilities, such as the following: the sample size (n = 23); the reference category being Black LGBTQ+ youth, if QT2S Native youth had such similar experiences that not enough variation was detected; or those that were coded as multiracial could potentially be coded as Indigenous multiracial. Similar variations in measures of Indigeneity can be seen in those using YRBSS data, as both

Bostwick et al. (

2014) and

Baiden et al. (

2020) included American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander groups into one conglomerate Native racial group, likely to accommodate sample size shortcomings. In their qualitative study,

Beltrán et al. (

2023) demonstrated an inclusive approach to measuring Indigeneity for communities in which the border crossed them, including American Indian, Alaska Native, Indigenous, and Indigenous Latinx respondents in their scholarship. As Hispanic and Latinx communities are often discarded in conversations on Indigeneity, it is refreshing to see work that defies colonially imposed borders. Ultimately, quantitative coding decisions are seldom described in detail in-text, while qualitative endeavors seemingly welcome the opportunity to explore this representation in depth. Quant scholars could take note of these expansive representations of Indigeneity. Perhaps providing an agreed upon means to measure the intersection of Indigeneity and gender and sexuality could remedy these issues in sample disparities and variations.

Gender and Sexuality. Despite the broader inclusion of queer, trans, and Two Spirit relatives in the scoping review search terms in the present study, several included studies took unique approaches to measuring gender and sexuality, or the lack thereof (

Barney 2004;

Bostwick et al. 2014;

Fix et al. 2022;

Schuler et al. 2023). For example,

Barney (

2004) excluded bisexual males, citing bisexuality as a contested ideology, while

Bostwick et al. (

2014) utilized an omnibus measure of sexual orientation that included any self-reported non-heterosexual identity, any same sex behavior, and any same sex attraction. Some studies excluded trans and gender expansive gender identity altogether (

Fix et al. 2022;

Schuler et al. 2023). This is particularly alarming given what is currently known about Native trans and gender expansive kin, as the 2015 US Trans Health Survey found that 57% of Native trans youth had contemplated or attempted suicide compared to only 4.6% of the general US youth population and 33.7% of the trans youth population (

Bell et al. 2021). Despite the common conflation of gender and sexuality in research, a more disturbing trend is trans erasure in LGBTQA+ spaces, including research. The current federal government is decidedly anti-trans with great proliferation of both state and federal attacks on trans relatives since the 2024 election. As responsible relatives and providers for QT2S youth, we must stay vigilant in how we include trans and gender expansive relatives in research, particularly in measurement options and connecting to broader advocacy efforts whenever possible.

4. Discussion

Developing healthy coping strategies and skills in adolescence and young adulthood is critical for lifelong wellbeing (

Craig Rushing et al. 2021), as three-fourths of all mental health diagnoses have their first onset by one’s mid-20s (

Fetter et al. 2025). Young adulthood is a critical time to intervene. This review presented several recommendations for physicians and behavioral health professionals to better support and advocate for QT2S Native youth.

The results of the present review demonstrated an overall dearth of positive aspects of social and emotional wellbeing for queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth. The majority of studies utilized quantitative means to illuminate QT2S Native youth health disparities; however, several also failed to meet a substantive sample size to run quantitative analyses. This review also illuminated data disparities and issues with measurement for future work to critically consider. How will future research meaningfully include queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth?

Despite the broadened inclusion criteria of various domains relating to QT2S Native youth’s social and emotional wellbeing, the present work only included 27 articles for full screening. In their global search for research on the social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous gender and sexuality diverse youth,

Soldatic et al. (

2022) included 12 articles in their final evaluation. If the present work applied more stringent inclusion criteria such as reporting QT2S Native youth (n = 2), requiring a sample size of at least n = 100 for statistical analysis purposes (n = 9), and excluding non-empirical studies (n = 5), our study would be at n=11 included articles. Essentially, broadened inclusion criteria did not make a substantial difference, again showing the dearth of research surrounding positive aspects of queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth’s social and emotional wellbeing.

Returning to the question of when QT2S Native youth ever get the chance to truly flourish, the results of the present review suggest further research is needed to illuminate these positive aspects across all micro axes of the rainbow medicine wheel: physically, spiritually, mentally, and emotionally. Further, the surrounding domains were also largely missing, with only economic variables, such as treatment and services, being represented in the review. Future work should include macro-level domains of the medicine wheel, such as environmental domains like land and water, social domains such as family and cultural wellbeing, and cultural domains such as ceremony, traditions, and language to better illuminate social and emotional wellbeing for queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth. In the general population, queer youth with higher levels of LGBTQA+ pride have 20% lower odds of attempting suicide compared to those with less pride (

Hobaica et al. 2024); it remains to be seen how QT2S Native youth pride in either LGBTQA+ pride, Native pride, and/or Indigiqueer pride relate to their social and emotional wellbeing.

Limitations

This scoping review is not without its limitations. Despite the plethora of search terms aiming to cast a broad net, there still remains a possibility of not identifying certain articles if they were not identified utilizing the outlined search strategy. Similarly, the breadth of these search terms could potentially muddy the waters, so to speak, as studies that included Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders as part of their measure for American Indian and Alaska Native could further contribute to an idea of the conglomerate concept of Indigenous. The trade off for inclusivity is a resulting lack of cultural specificity.

Given the scoping nature of the present review, there was no evaluation or comparative analysis of the outcomes or methodological rigor of the included studies. Further, the present study included non-empirical studies to provide as holistic a view of social and emotional wellbeing as possible; thus, these articles had no results to compare. Despite not conducting comparative analyses, the present work did note methodological issues in sampling and measures to provide insight into QT2S Native youth’s social and emotional wellbeing and further the state of science. It is the hope of the present author that future researchers will build upon this work to empirically evaluate methodological rigor for various domains of social and emotional wellbeing.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the results of the present study found that queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth’s social and emotional wellbeing is largely shaped by their experiences interacting with systems such as school, the medical system, and juvenile justice; however, the majority of this scholarship continues to highlight health disparities and implicate axes of identity as risk factors rather than seeking to better understand and support these youth. There is a great need to conduct strengths-based culturally grounded research for QT2S Native youth.

We can take notes from our global Indigenous relatives such as those in Canada and Australia. In Canada,

Ansloos et al. (

2021) highlighted that rather than the Western concept of “coming out”, queer Indigenous scholars posit that QT2S Indigenous folx “come in” to be in places of cultures and histories and imagine radical futures. What a dramatic paradigm shift this work could look like in the US if scholarship was centered on QT2S Native youth coming in to their communities, cultures, and how they want to be in the world. Similarly, in Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander scholars have delineated an emerging concept of cultural health that seeks to understand how one’s connection to and practice of culture, cultural resources, and governance impact health and wellbeing (

Biles et al. 2024). There was an overwhelming dearth of culture-based social and emotional wellbeing domains in the present study. Indigenous cultures must be considered part of the solution, rather than the problem, in order to address and improve wellbeing (

Tsuji et al. 2023). Queer, trans, and Two Spirit Native youth deserve to thrive; the present work sought to illuminate axes of social and emotional wellbeing to better support this thriving both in research and in practice.