Abstract

This study examines adult migrant students’ and Finnish vocational teachers’ experiences of migrant students’ learning in workplaces as part of vocational education and training qualifications. Theoretically, this study draws on previous research on students’ work-based learning, including insights from the 3P model (presage–process–product factors), as well as the literature on learning and working in a new linguistic and cultural context. The data were collected through individual interviews (n = 11) and a group interview (n = 6) with migrant students and individual interviews with vocational teachers (n = 13). The analysis provides insights into learner-specific and workplace-specific presage factors of migrant students’ learning at workplaces. We propose that these insights should be recognised when searching for new pedagogical solutions aiming at enhancing understanding of migrants’ learning at workplaces. The findings highlight the need to develop the integration of school-based and work-based learning while recognising (1) the benefits of workplace learning for migrant students’ learning and their journeys toward becoming members of work communities, and (2) stereotypical views that may hinder migrants’ efforts to access the benefits of learning in the workplace.

1. Introduction

Previous research has shown that learning in the workplace combined with school-based education has benefits such as: (1) the variety of skills and knowledge gained (Virtanen et al. 2014), (2) the development of self-directed learning, the capacity to take on responsibility, and generic and leadership skills (Täks et al. 2014), (3) students’ professional identity construction (Heikkinen et al. 2011; Tynjälä et al. 2009), and (4) students’ motivation (Helle et al. 2007; Tynjälä et al. 2020). In parallel, extensive research on workplace learning has demonstrated that several factors contribute significantly to successful learning outcomes, a novice moving from peripheral tasks to more complicated ones (Lave and Wenger 1991), and becoming part of a “community of practice” (Wenger 1998). These factors include participation (e.g., Billett 2001; Fuller and Unwin 2004), interaction with more experienced workers (Tynjälä 2008; Billett 2004a), adequate guidance (Virtanen and Tynjälä 2008; Filliettaz 2011, 2013), and the overall atmosphere of the workplace (Pemberton et al. 2007). It has been observed that workplaces vary in their support for learning, particularly in terms of offering opportunities for participation (Fuller and Unwin 2004) and providing guidance (Filliettaz 2011, 2013). While Virtanen et al. (2014) have pointed to differences among various vocational fields concerning learning environments, and therefore opportunities to learn, Billett (2004a) has argued that apprentices must actively use these opportunities. However, research specifically focusing on migrant students’ work-based learning is only emerging.

Workplaces are also recognised as important arenas of migrant learning and journeys toward becoming members of work communities and society at large (Kärkkäinen 2017; Sandwall 2013; Strömmer 2017). Yet, research has shown that perceptions vary greatly of migrants in society, including perceptions of migrants in workplaces (Anderson 2024; Näre 2013; Näre and Maury 2024; Roberts 2012). Previous studies have recognised misconceptions that arise concerning migrants’ cultures and languages and the overemphasis on their cultural and linguistic differences in education (Dervin 2016) and workplaces (Lahti 2015). These assumptions sometimes lead to othering practices, where migrants or specific groups among migrants are regarded as significantly different and inferior workers (Kalonaityte 2010; Näre 2013). Similar results have been identified in the context of international students’ learning in workplaces as part of vocational education, pointing to experiences of deskilling and inequalities due to the students’ backgrounds (Wall et al. 2017).

Previous research has shown that facilitating learning in the workplace for migrants demands adaptation from the migrants, educators, and work supervisors, including adjusting practices (Kärkkäinen 2017), broadening educators’ competences (Lehtimaja and Kurhila 2018; Mustonen et al. 2020), and changing perspectives on migrant integration (Kärkkäinen and Tarnanen 2022). Overall, multidimensional conditions affect migrants’ daily lives (Vertovec 2007) and learning (Kärkkäinen 2017) in host societies. The ability to communicate in the host country’s language has been highlighted as key to migrant students’ learning (Dooley 2009; Paul 2023) and integration into working life (Delander et al. 2005; Tarnanen and Pöyhönen 2011). Moreover, safe and trustful learning environments have been found to encourage migrant students to ask questions and share different perspectives (Chavez and Longerbeam 2016), allowing the range of skills, knowledge, and experiences that migrants bring to the learning environment to become visible (Gutiérrez and Rogoff 2003; Hedegaard and Chaiklin 2005). Proper guidance has been acknowledged as important in the integration of migrants into work communities and learning in workplaces (Sandwall 2013).

Learning takes place in specific settings, with the wider social and cultural environment affecting migrants’ learning in the workplace. Studies in Europe show that not all migrants and asylum seekers are equally accepted by the local population. Migrants with good employment prospects and non-Muslims are more likely to be accepted (Bansak et al. 2016), while attitudes toward other groups are less positive. Similarly, migrants from non-Western backgrounds are often seen as difficult to guide and thus are expected to have poor prospects for successful learning and integration into Finnish work communities (Kärkkäinen 2017). Ongoing debates about the acceptance of migrants and asylum seekers in Europe (Gerhards et al. 2019) may influence the general mood in society and organisations. People from countries with a history of struggling for independence, such as Finland, may be more reserved towards newcomers (Gerhards et al. 2019).

Existing research in the context of migrant integration into the workforce has focused on language learning (Sandwall 2010; Strömmer 2017; Suni 2017), intercultural interactions (Lahti 2015), and obstacles to entering workplaces (Ndomo 2024). The role of vocational education and training (VET) in the integration of migrants into host societies and workplaces has also been considered in recent research, pointing to challenges in integrating migrants via VET and a need for more research in this area (Eliasson et al. 2022). Certain conceptual insights, such as Billett’s (2004a) ideas of active participation and learning affordances and Lave and Wenger’s (1991) concept of legitimate peripheral participation have been used to understand migrants’ journeys to becoming work community members (Strömmer 2017). Differences among various vocational fields in creating opportunities for migrants’ learning and integration have also been observed (Kärkkäinen 2017). However, research on migrants’ learning in workplaces lacks a holistic conceptual and theoretical approach that recognises the variety and complexity of factors related to migrants’ learning. Against that background, this study utilised the 3P model of workplace learning (presage–process–product factors) and insights from integrative pedagogy (IP) and the broader literature on adult migrants’ learning to gain a better understanding of migrant students’ learning in workplaces along their learning pathway. These theoretical choices allowed us to approach migrants’ learning holistically by taking into consideration the wider context (e.g., workplace atmosphere and culture).

Various terms have been used in research to depict workplace learning (Hills et al. 2003). In this article, we use the term workplace learning to refer to “formal work-based learning”, as the majority of learning occurs in real work environments in Finnish VET (Dehnbostel and Schröder 2017). We also acknowledge that, in the workplace, migrant students may unintentionally learn things that are not explicitly included in the qualification criteria (Kyndt and Baert 2013). Additionally, it is important to note that it can be challenging to distinguish between formal and informal aspects of learning in workplaces (Billett 2004b, 2002).

2. 3P Model of Workplace Learning and Integrative Pedagogy Principles

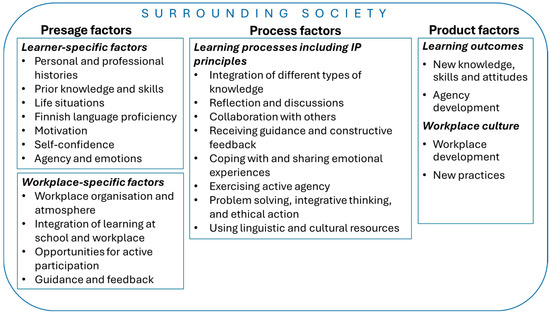

The 3P model of students’ workplace learning (Tynjälä et al. 2022a) was originally developed as a conceptual tool for understanding the diversity of factors affecting any student’s learning in the workplace. Integrative pedagogy, meanwhile, was designed for practical use for the development of teaching and learning, originally in a higher education context. The elements of both models and key insights from the literature on migrants’ learning and teaching are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall framework of migrant students’ work-based learning (modified for the migrant learning perspective from Tynjälä et al. 2022a, 2022b and supplemented by insights from Kärkkäinen 2017).

As illustrated in Figure 1, the aspects of students’ learning in workplaces are divided into presage, process, and product factors, following the original 3P model by Biggs (1999) and its modifications for the workplace context (Marsick et al. 2011; Tynjälä 2013; Tynjälä et al. 2022a). The presage factors comprise (1) learner-specific factors (e.g., motivation, agency, emotions) and (2) workplace-specific factors (e.g., atmosphere, opportunities, and guidance and feedback practices). The process factors include a variety of activities facilitating students’ learning in workplaces, such as reflection, problem-solving, critical thinking, collaboration with others, and manual work. Finally, the product factors refer to learning outcomes, varying from new knowledge, skills, and attitudes to identity and agency development, and in some cases, even to the development of new practices or artifacts. Although these expected learning outcomes are useful and positive, students may also learn some bad habits and practices in workplaces, which should be addressed during VET (Virtanen et al. 2014). The relationships among the different elements of learning are multidirectional. Presage factors, such as a student’s motivation, their life situation, or the atmosphere and opportunities of the workplace, impact learning processes and outcomes. In turn, positive outcomes of work-based learning may impact the learner’s motivation and self-confidence. The 3P model also recognises the wider context in which learning takes place, considering socio-cultural factors. For example, how communities at school and in the workplace, the education system, and the labour market operate in society may be reflected in microlevel practices during training and attitudes towards training students; in this case, migrant students in workplaces. Presage factors set a starting point for students’ learning in workplaces. In the case of migrant students, their specific circumstances as learners must be recognised, which are related to their personal, educational, and professional histories, life situations, and learning in a new linguistic environment (Kärkkäinen 2017; Vertovec 2007).

Studies of workplace learning have recognised that, although learning at work is practical in nature, the work activities and learning needed to become an expert require close integration of different forms of knowledge, that is: (1) theoretical, (2) practical, (3) self-regulative, and (4) socio-cultural (Bereiter and Scardamalia 1993; Tynjälä et al. 2022b). IP emphasises the need to make connections among different types of knowledge, and the first principle of IP for workplace learning is the following: Support students to integrate different forms of knowledge (Tynjälä et al. 2022b). Socio-cultural knowledge is embedded in the social practices of the workplace. These practices include explicit or implicit rules on how things are done, what kind of behaviour is acceptable, and the power relations between employees, for instance. This kind of knowledge can only be gained by participating in communities of practice (Cairns 2011; Wenger 1998; Wenger et al. 2002) and collaborating with co-workers. Therefore, it is important that students complete authentic work experience during their studies, which is the case in Finnish vocational education.

The integration of different forms of knowledge can be achieved with various pedagogical tools (e.g., discussions, collaborative tasks), which require students to apply theoretical knowledge in practice and explicate and reflect on their practical experiences with the help of conceptual knowledge or theoretical models. It is important to encourage, support, and guide students in these integrative learning processes and to give them timely and adequate feedback on their work and performance. Thus, the second principle of integrative pedagogy is as follows: Ensure that students receive guidance and constructive feedback (Tynjälä et al. 2022b).

As shown in Figure 1, emotions are included in the student-related presage factors of learning, highlighting these as impacting students’ learning. The role of students’ emotions in learning has been researched widely both in work and education contexts (Aarto-Pesonen and Tynjälä 2017; Eteläpelto et al. 2018; Hökkä et al. 2019; Ketonen et al. 2018; Talvio and Lonka 2021). In a study by Täks et al. (2014), it was found that managing students’ emotions is especially important in learning environments that are new to them and which require more active input from students than before. For example, during internships, students often experience anxiety because of low self-confidence (Billett 2015). Similar observations have been made in the migrant education context (Kärkkäinen 2017). Therefore, discussing possible challenges of internships or work-integrated projects in advance and afterwards, as well as organising support channels for students, has been recommended (Täks et al. 2014). Emotions are addressed in the third principle of integrative pedagogy: Discuss with students how to cope with emotions and arrange opportunities for them to share both positive and negative emotional experiences (Tynjälä et al. 2022b).

Student agency as a presage factor of learning has an important role in both educational and work environments (e.g., Billett 2008, 2011; Eteläpelto et al. 2013; Goller and Paloniemi 2017; Jääskelä et al. 2017, 2020a, 2020b). In higher education studies, agency is regarded as a combination of individual (e.g., self-efficacy), context-related (e.g., opportunities to influence), and relational factors (e.g., teacher and peer support) (Jääskelä et al. 2017, 2020a, 2020b). Student-centred teaching that encourages active learning has proven to predict student agency (Jääskelä et al. 2017, 2020a, 2020b) and the development of generic skills (Kember et al. 2007; Virtanen and Tynjälä 2019). In the context of VET, students’ active membership in the workplace correlated with students’ perceived learning during their work placement (Virtanen et al. 2014). Based on these findings, the fourth principle of IP is formulated as follows: Encourage students’ active agency. To that end, Tynjälä et al. (2022b) have suggested balancing self-regulated action by the student and guidance by the teacher or workplace supervisor. It has been noted that students often need more support at the beginning of their work-based learning.

Finally, the fifth principle of IP is the following: Assign students learning tasks that involve problem-solving, integrative thinking, and responsible ethical action. As occupational problem-solving often involves ethical challenges, teaching students to take responsible ethical action is an important part of integrative pedagogy.

Both the 3P and IP models have been used in previous studies with a variety of application purposes (e.g., Elvira et al. 2016; Ortoleva and Bétrancourt 2016; Tynjälä et al. 2016, 2022a), including use of the 3P model as an analytical tool for organising results regarding students’ learning in workplaces (Tynjälä et al. 2022a). Although the 3P and IP models have been extensively applied in previous research, neither has yet been examined in the migrant education context. In this study, we gained insights from both models when modified to suit the migration context (Figure 1). These models were applied to analyse and improve our understanding of specific features of migrant students’ learning in the workplace. In particular, we focused on learner- and workplace-specific presage factors, which form the basis for students’ learning processes and their journeys to becoming members of work communities.

3. Purpose and Context of This Study

This study explored migrant students’ learning in workplaces in the context of Finnish vocational education and training. During data collection, students were engaged in their work-based learning periods. While students inevitably also learn informally at workplaces (e.g., Kyndt and Baert 2013), in the present study we did not analytically separate formal and informal learning, but only focused on “learning”, whether it took place formally or informally at the workplace.

Recognising these features of work-based learning, the guiding research questions of this study were the following:

- (1)

- What experiences do adult migrant students and their teachers have of migrant students’ learning in workplaces?

- (2)

- What practices contribute to migrants’ learning in workplaces?

These questions were examined by focusing on the learner- and workplace-specific presage factors of migrant students’ work-based learning, as described in Figure 1.

4. Data and Methods

The data collection for this study consisted of semi-structured individual interviews with adult migrant students (n = 11) and vocational teachers (n = 13), as well as one group interview with six migrant students. Both groups of interviewees were asked about their experiences of migrant students’ learning and studying in Finland, how and where migrant students learn the best vocational knowledge and skills during their studies, and how and where they learn knowledge and skills that are helpful for their everyday life in Finland. The teaching staff was also asked about experiences of teaching migrant students. The backgrounds of student participants varied in terms of country of origin, education, age, reasons for migration, family situation, work experience, experience of living abroad, and length of stay in Finland before studying. While some students had limited education, others had a rich history of studying in their own countries and in Finland and were familiar with the idea of learning in the workplace. The students had moved to Finland in different phases of their lives and lived in Finland for 3–20 years. Some students had lived in a few other countries before moving to Finland. We learned that some students were re-educating themselves in their field, whereas most were new to the chosen field. The migrant participants were studying in programmes of health and social sciences, audiovisual communication, business administration, security, bakery/confectionary and catering services, wood processing, and cleaning services. In addition to the fields mentioned, two teachers were teaching construction and logistics. The work experience of teachers teaching in general and teaching migrant students in particular varied greatly, from little teaching experience to many years of teaching and working with migrants. In most cases, the teachers were teaching the interviewed migrants.

The data were analysed via theory-driven thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). The theoretical framework was based on learner- and workplace-specific (presage) factors of the 3P model supplemented with key insights from the literature on the specifics of learning and working in new linguistic and cultural contexts (Figure 1). This was utilised to structure, analyse, and interpret the data. It produced results that allowed for reflection in the Discussion Section on the process and product factors involved in migrant students’ work-based learning. The data were analysed in the original language, Finnish. The translations of excerpts provide the closest possible meaning. To ensure participants’ anonymity, we use pseudonyms.

5. Results

Learner-Specific Presage Factors Impacting Migrant Students’ Learning in the Workplace

The findings highlighted the differences in how migrants and teachers viewed migrants’ personal and professional histories, prior knowledge, skills, and experiences. Some teachers favoured Western backgrounds as better for successful learning. One teacher viewed a migrant student’s adherence to his professional position and working experience in his homeland as a cultural barrier in Finland. Among the student interviewees, meanwhile, some planned to use their entrepreneurial experiences to start businesses in Finland. Students usually saw their previous knowledge and experiences as a basis for learning in Finland, while some teachers considered those irrelevant and believed students should adopt Finnish ways of working. Similar disparities existed in views on linguistic skills. Students used their mother tongue and other languages (e.g., English, Latin) to prepare portfolios and find information. Although some teachers recognised the importance of the mother tongue for understanding vocational content, communication in a mother tongue was seen as a sign of not learning Finnish. Due to differences in their personal, educational, and professional histories and experiences from the norms in Finland, migrant students were usually confronted with new practices, feedback practices, communication styles, and expectations when studying in Finland. Some teachers noted that migrant students saw educators as authority figures and struggled to understand the concept of adult learning and competency-based testing. Students, including Anna, Pedro, and Aisha, also reflected on these trends but did not consider their impact on learning. Some students even considered teachers mother- or father-like authorities, giving advice how to act and interact in Finland in certain situations, and spoke of how they valued learning by doing, as in the following excerpt:

Tell me what I should do, and I will go and do that. (Anna, practical nursing student)

Both teachers and students discussed the impact of migrants’ life situations and Finnish language proficiency on learning in Finland. Migrant students faced challenges in settling into a new environment and navigating new social, legal, and linguistic contexts. Teachers noted frequent absences due to paperwork related to handling visas or family matters. Instances of students worrying about relatives in their homelands were also reported by students and teachers as affecting students’ ability to concentrate on study matters. The reason for moving to Finland and the length of stay also seemed to influence the learning experience. Students with Finnish partners had better social support, and those with refugee backgrounds relied more than others on teachers. As noted by Elena, a practical nursing student, and confirmed in some teacher interviews, students with refugee backgrounds were left more on their own due to the lack of a supportive network. Meanwhile, according to some teachers and students, longer stays in Finland helped students to understand its society, working life, and education system and to learn Finnish, which was beneficial for their learning:

And of course, the amount of time spent in Finland matters too. So you kind of need […] to understand the Finnish society, structures, and activities. And this probably affects the learning and having peace of mind (Matti, social sciences teacher).

Understanding complex issues and processes seemed to be particularly difficult without a good command of Finnish. Some teachers recognised that language barriers hindered students’ understanding of vocational concepts and nuances in the workplace. Sini, an audiovisual communication teacher, observed that students might understand single words but not the full context. This was confirmed by students who felt insecure about their understanding and ability to express themselves. Some students and teachers reported difficulties in communication related to workplace learning periods (e.g., not understanding messages), with language issues complicating interactions between students and employers (e.g., during a work placement interview). This was also evident in the following teacher reflection:

Though somebody is intelligent, educated, and competent, it is impossible to show all of it, if a person does not speak Finnish well (Ellu, business administration teacher).

Thinking this way may have undermined migrant students’ skills, knowledge, and experiences. From discussions with other teachers, it became clear that some students, especially of non-Western backgrounds, are considered difficult to guide, for example, if they do not know any recognisable (Western) language. Assessing second language learners’ knowledge and skills in workplaces was raised as an issue and highlighted as being difficult to accomplish, mainly by the interviewed teachers. Meanwhile, despite recognising the challenges of learning in Finnish and a new environment and being aware of unfavourable attitudes towards them as migrants, the students were motivated and optimistic about completing their studies. Learner’s motivation, emotions, self-confidence, and agency appeared as important moderators of migrants’ learning experience.

In general, learning in Finnish workplaces produced conflicting emotions for migrants (and also for teachers). Students usually appreciated their free education and the support of teachers, which was confirmed by some teachers. Studying led the students to feel hopeful, and they aspired to find a job and lead a good life in Finland. Not all students we talked to were enthusiastic about going back to school; however, they did seem aware that this was expected of them:

I am an adult person. I want to go to work. I just want now to study and get this certificate (Anna, practical nurse student).

Unanimously, the teachers were convinced that the possibility of “studying by doing” motivated adult students (even those who were not good learners), as was confirmed in some interviews with students.

The analysis of teachers’ and students’ interviews revealed negative emotions and a lack of self-confidence, which hindered students’ learning, agency, and motivation. Both teachers and students noted that learning in a new linguistic and cultural environment is tiring and creates insecurity and frustration. Some teachers mentioned students’ insecurity about communication and knowing what was expected of them, which was reflected in students describing feeling anxiety and a reluctance to ask for help. Concerns about how others would react to their questions and behaviour were raised in the student interviews. As mentioned earlier, there was an expectation among teachers (and in workplaces) that migrant students should unlearn their old ways of doing things and behaving. Although this was not explicitly stated, for the students, it may have led them to feel they were not accepted or appreciated. While some students could follow their desired educational path, others felt forced to retrain for a profession for which they were qualified in their home countries or for an educational path below their abilities. Some students questioned the purpose of this. Although the intention was good—to help migrants find a place in Finland—such practices led to the feeling that prior knowledge, skills, work history, and experience were undervalued. Experiencing success and being valued seemed crucial to students’ motivation and agency:

At first, I wanted to move back. I didn’t want to learn Finnish or anything. But then my mind has changed when I got my first job and I was appreciated there, […] The will to become a practical nurse and studying grew on me (Maria, practical nurse student).

In the same vein, some students and teachers described settling in as particularly difficult at the beginning because of difficulties in coping with everyday life; missing home, their old life, and relatives; loss of social status; and financial worries. Even students who had lived in Finland for a long time reported that they needed a lot of encouragement from teachers, family, and friends, did not always believe in their own abilities, and did not feel comfortable taking the initiative to ask for clarification or help. Some teachers linked this to migrants’ inflexibility in completing work tasks and a desire to do as they were told at school. This limited students’ agency and opportunities to learn by trying out and adapting their knowledge to a workplace context. Most of the teachers thought that the students did not adapt their actions because of their insufficient knowledge of Finnish, learning in a new environment, their cultural background, and the authority of the teacher. Some students told us that they were careful about what they said and how they behaved because they had bad experiences during their studies (including at work) of not being fully accepted. Students in the group interview expressed the will and ability to apply what they had learned at school in the workplace, but, as they had experienced, inadequate feedback limited their actions. Marcus stated that he wanted to take on more responsibility, but his agency was limited by the fact that he was a student.

Certainly, individual differences among students appeared concerning their capabilities to study and self-confidence, and as reflected by some students and teachers, these were mirrored in students’ study motivation and progress. Some students stressed that they were industrious learners and noted that they preferred certain modes of working, independent of the context; they shared experiences of asking questions and asking for help.

6. Workplace-Specific Presage Factors Impacting Migrant Students’ Learning in Workplaces

Some teachers pointed to differences between workplaces and vocational fields concerning the workplace organisation and atmosphere and how migrants were taken in. These differed depending on whether workplaces had experience with training migrants and based on the required level of Finnish in a certain field. According to some teachers, employers in certain fields (nursing, accounting) were more concerned about Finnish language skills than others. Moreover, the atmospheres in certain vocational fields and workplaces were reflected in migrants’ (positive and negative) experiences of interactions in those workplaces. Some teachers also raised the issue of employers’ lack of familiarity with the educational backgrounds and skills of migrants, leading employers to distrust their skills, especially those from non-Western backgrounds. Some teachers’ reflections clearly indicated there are stereotypical views of migrant workers in some fields:

[Workers from] Russia and other nearby areas, they are received rather well at construction sites. […] But then, for example, for a person from Africa, it’s almost impossible to work on a construction site. Maybe their cultural background and the background of doing anything with their hands is very different, and so is their success (Jouni, construction teacher).

One teacher described similar divisions also in society at large, predefining students’ experiences of learning in workplaces. From the perspective of some teachers, Finns and Finnish workplaces need time and experience to become used to migrants.

Linguistic and cultural matters were easily identified and used as a main point of reference when approaching migrant students in the workplace (and institute). Such views and discourses among colleagues and supervisors in workplaces (and teachers in the institute) undermined migrants’ previous skills and experiences. As mentioned by some teachers, Finnish language skills and a Finnish certificate were often perceived as a guarantee of adequate skills and the ability to carry out a job in the proper, Finnish way:

We also need language skills to be able to do a job in the right way; I mean to handle things according to the Finnish principles (Paula, practical nurse teacher).

Exactly how I said, they need to participate in education and to get a certificate, so that their own skills can be showcased with the help of such a certificate (Matti, social sciences teacher).

Flexibility in assessment practices and arrangements of learning in the workplaces were raised as important aspects of students’ learning. Interestingly, the topic of flexibly adjusting practices was discussed only by teachers. Allowing students to create more functional portfolios and extending periods of workplace learning were recognised as tools that support students in passing competence-based tests. Depending on the student and perceptions of migrant workers in some fields, adjustments were made concerning the optimal balance of learning in the school and workplaces. Unanimously, students and teachers reflected on the gap between theory and practice, with the gap considered problematic. However, there was no reflection in the interviews on pedagogical tools used (or that could be used) to help students combine different types of knowledge. Some teachers were convinced that theory in school should be taught first, but that the time spent at the institute should be adjusted according to how migrants are perceived as workers in different fields. This indicates that the atmospheres in different workplaces may shape pedagogical practices. It was clear that apprenticeship training was considered unanimously by teachers and students alike as a suitable option for migrant students, as it offers a path where learning takes place mainly in workplaces. Our analysis showed that much programme content, such as learning vocational skills and gaining vocational knowledge of the Finnish language, was learned mainly in workplaces. Therefore, students usually wished to be transferred to workplaces sooner.

Teachers and students unanimously recognised that other opportunities for learning and active participation exist in workplaces than those in the training institute. Workplaces naturally create possibilities for learning by doing, observing, modelling, and working together with co-workers or a supervisor. These practices were recognised as supporting students’ learning. Some students also gave examples of asking co-workers for help with school tasks or handling personal matters in Finland. As some teachers reflected, vocational fields where migrants worked with others provided more opportunities for participation and learning through interaction with their co-workers. However, these connections were not made in cases where co-workers were reserved around or anxious about entering into interactions with non-Finns. Perceptions of different groups of migrants in the workplace mattered, regardless of a non-Western or -European background. Some students (both in individual and group interviews) reported experiences of exclusion and hesitation to train them, limiting their opportunities to learn and actively participate, and consequently, also their agency:

I am asking, ‘So, what I could do with marzipan?’ And then she says, ‘I do not remember’. […] At least, I can say for myself, one hundred percent sure that they do not want to train me (Marta, bakery/confectionary student).

Similarly to Marta, Elena also shared experiences of exclusion. Both students associated such treatment with their migrant background, and it led these students to be overcareful in entering into interactions. Consequently, many opportunities to learn were unused. Examples of making divisions between “us” and “them”, which restricted interactions, were described in all interviews. These views were accompanied by the belief that migrants with a Western background had better prospects for participating in Finnish working life due to their familiar cultural and linguistic backgrounds, which created better opportunities to learn and participate for some migrants.

The views on migrants and their backgrounds were then also mirrored in guidance and feedback practices in some workplaces. Students usually noted inadequate feedback and guidance, bad experiences with asking questions, and the resulting difficulty of learning in workplaces:

I see it, they don’t speak directly, ‘Everything’s fine’ and they smile but then you don’t know what happens (Amara, cleaning services student).

Amara later expressed her annoyance with the need to be an initiator in the learning process, reaching out and asking for feedback, rather than workplace representatives taking the initiative. Meanwhile, a catering services student, Marta, described asking for feedback and guidance but not always then receiving those.

In the context of migrant students’ learning, language-aware guidance also seemed to matter. Such supportive, language-aware, practices were usually noted in the context of learning at school, but they are also important in the context of work-based learning. Some teachers identified it as good practice to take the time to ask if everything had been understood and if anything needed rephrasing, asking additional questions, discussing a matter in light of students’ experiences, and repeating and explaining unusual words. Moreover, some teachers noted the importance of paying attention to what and how they spoke, using simplified language materials, talking slowly, dropping all unnecessary words, giving examples, and holding eye contact. These teachers believed that practices such as these gave students time to process and contextualise the knowledge in a new linguistic and cultural context. Students in the group interview then brought up another practice that enhanced their understanding and learning, which was being guided by the same person in the workplace.

Unanimously, the teachers were convinced that migrant students need more guidance than their Finnish peers. This guidance is seldom limited to study matters. Some teachers and students reflected on how students receive guidance and advice from co-workers, including on matters related to everyday life in Finland. Teachers were aware that guiding migrants can be viewed as an extra burden for workplaces, and that migrant students seldom receive enough and timely guidance, which was reflected in some students’ experiences. It was continually stated by students that direct and precise feedback serves their learning the best:

It’s good if they say directly, ‘This isn’t good, this is right’ (Amara, cleaning services student).

Some teachers, on the other hand, thought that being paired up with a co-worker was a good way of guiding migrant students. Furthermore, given students’ different sets of experiences, they may have different guidance needs, which emerged in the reflection of Jouni, a teacher in the construction field:

Many of those coming from Russia have worked in construction there, so then it’s much easier for us to organise the work practice placement for them and we trust them more. We need to guide them less (Jouni, construction teacher).

Support from teachers, co-workers, family, and friends was identified by some teachers as important for students’ learning and most probably also their agency. Teachers gave examples of reassuring students that they, as migrant students, were good and wanted workers, and that they would train their migrant students well to manage in working life. Students usually appreciated teachers in Finland being supportive, which was not always the case in their home country. However, some students—namely, Elena and Marta—shared experiences of not receiving the necessary support from teachers and co-workers. Elena associated this with a teacher’s personality. In this regard, teachers seemed to be key actors in supporting their students to interact in Finnish workplaces and with employers, for example, in establishing a first contact with employers, convincing employers about migrant students’ knowledge and skills, and creating better prospects for their successful learning in workplaces. Teachers’ actions here also reduced the negative impacts of stereotypical views in workplaces of migrant students’ backgrounds and skills.

In addition, support from family and friends was identified as crucial for migrants’ learning. Some teachers and students mentioned students being helped by friends and family, for example, in preparing a portfolio. At the same time, there was the awareness that students with Finnish family members had a broader network and more possibilities to receive support:

I have many friends who are studying in Finland. They are saying the same, ‘If I didn’t have a Finnish wife, what would I do?’ That is really difficult (Marcus, wood processing student).

Both teachers and students generally thought that using students’ and teachers’ experiences supported migrant students’ learning. Nonetheless, some teachers saw some of their students’ experiences as an obstacle to learning and working in Finland, as they regarded these experiences as being different or irrelevant. Referring to these experiences by making cross-cultural comparisons was a questionable practice, sometimes creating tensions. In other instances, some students appreciated teachers who incorporated their practical experiences into their teaching.

7. Summary of Results

Table 1 provides a summary of teachers’ and students’ perspectives on learner- and workplace-specific presage factors involved in migrant students’ learning in workplaces.

Table 1.

Presage factors of migrant students’ learning in workplaces.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined the experiences of vocational teachers and adult migrant students regarding work-based learning as part of adult formal vocational education. The study adopted an innovative approach by incorporating elements from the 3P model of workplace learning (Tynjälä 2013; Tynjälä et al. 2022a) and augmenting it with insights on migrants’ learning processes (Kärkkäinen 2017; Paul 2023) to analyse learner- and workplace-specific precursors to migrant students’ learning in the workplace.

The present study makes three major contributions to the field. Firstly, the findings contribute to a more expansive conception of the presage factors of work-based learning of migrant students. The study underscored the significance of the work environment’s atmosphere for migrant students’ learning, a finding that is also salient for any student (Chan 2016; Mikkonen et al. 2017; Tynjälä et al. 2022a; Vila et al. 2012; Virtanen et al. 2022). However, this aspect and its impact on learning were even more noticeable in the context of migrant students’ learning, thereby contributing to understanding of the barriers to the inclusion of migrants in Finnish work communities.

The analysis demonstrated that distinct groups of migrants may possess varying degrees of recognition for their skills and learning in the workplace. Assumptions about migrants’ linguistic and cultural backgrounds were employed to predict who will and will not succeed in learning and work in a particular field. Furthermore, differences between workplaces and occupational fields were observed. The manner in which migrant learners are perceived in the workplace appears to reflect broader attitudes toward the admission of diverse groups of migrants as asylum seekers and workers (Bansak et al. 2016; Gerhards et al. 2019). This observation underscores the importance of comprehending the prevailing discourses on migrants in society, as a prerequisite to understanding the pre-conditions for migrants’ learning in the workplace. Furthermore, past experiences involving interactions with foreigners or migrants have been shown to positively influence workers’ openness to training migrants, thereby enhancing the opportunities for learning and engagement in the workplace. This notion has been previously emphasised in related studies, underscoring the significance of prior intercultural experiences in facilitating smooth interactions with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds (see Kim 2001; Lin and Shen 2020).

Secondly, the incorporation of multi-actor analysis, which included the viewpoints of migrant students and vocational teachers, enabled the formulation of conclusions concerning salient tensions related to migrant students’ learning in the workplace. While students reflected on their prior experiences as the basis for new learning, teachers viewed these experiences as impediments to learning in the workplace and advocated for their elimination. The demand to erase elements of students’ professional backgrounds that did not align with the Finnish context appeared to be intertwined with a lack of discussion on the richness and diversity of migrant students’ personal, educational, and professional histories in the workplace. This finding underlines the necessity to raise awareness among educators and employers of how migrants’ experiences and skills offer resources (Gutiérrez and Rogoff 2003; Hedegaard and Chaiklin 2005). Consequently, there is a compelling need to promote linguistically and culturally supportive pedagogies in vocational schools and workplaces (Paris 2012).

The findings regarding the unlearning of traditional ways of thinking and doing are somewhat contradictory. At times, the same educators emphasised the importance of referring to migrant students’ experiences. The implementation of these practices appeared to be contingent upon the individual teacher’s approach and were situationally dependent. Analogous contradictions were evident in relation to the agency of migrant students: students were expected to demonstrate autonomy and proactively seek guidance; however, the analysis also identified factors that can impede students’ autonomy. These include feelings of uncertainty stemming from studying and working in an unfamiliar environment and an unfavourable atmosphere and practices, as well as a perception that migrants lack the necessary skills for the workplace. These contradictions may indicate that educational institutions and workplaces are grappling with the challenges posed by the increasing presence of migrants and are seeking effective responses to the growing number of students and workers with a migrant background (Dervin 2016; Lahti 2015).

Thirdly, the study highlights the potential of using the 3P model (Tynjälä 2013; Tynjälä et al. 2022a) to comprehend migrant students’ workplace learning, along with the need for further research on process and product factors involved in workplace learning in migrant education. The 3P model offers significant opportunities to broaden understanding of migrant students’ learning; however, it must be adapted to this specific context. This adaptation involves acknowledging migrant students’ life situations, the particularities of learning in a new environment, and existing discourses about migrants and their competencies at organizational and societal levels.

In summary, the two groups of interviewees demonstrated a common awareness of the advantages associated with learning in the workplace. However, the results suggest that the practical nature of VET cannot be utilised without recognizing the specific needs of migrant learners, providing adequate guidance to migrant students, and changing perceptions of migrants and their skills. These conclusions are consistent with those drawn from prior research on second language learners in VET (Kärkkäinen 2017; Paul 2023). Acknowledging stereotypical views about migrants and their skills, as well as language and cultural aspects in the workplace, is imperative to understanding their impacts on workplace practices, students’ learning processes, and outcomes. In subsequent studies, it would be advantageous to engage in collaborative research with a diverse array of stakeholders, including employers and workplace supervisors, to obtain a comprehensive understanding of migrant students’ learning experiences in the workplace.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: P.T., K.K., M.H.V. and A.V.; methodology: K.K. and P.T.; formal analysis: K.K., P.T., M.H.V. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation: K.K. and P.T.; writing—review and editing: P.T., M.H.V., A.V. and K.K.; project administration: P.T., K.K. and M.H.V.; funding acquisition: P.T. and M.H.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by EU FEWL project (agreement number: 101079237).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data were gathered by the permission of the educational institution involved. The study followed the ethical guidelines by Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK) and no ethical review statement was needed (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK, 2023). Participants were informed in written and oral form about terms of participation, informed consent was obtained, and data were processed anonymously. Reference The Finnish code of conduct for research integrity and procedures for handling alleged violations of research integrity in Finland 2023 (tenk.fi).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aarto-Pesonen, Leena, and Päivi Tynjälä. 2017. The core of professional growth in work-related teacher education. The Qualitative Report 22: 3334–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Britget. 2024. Blurred boundaries: Fantasy citizenship, the worker citizen and mobility controls. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50: 2767–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansak, Kirk, Jens Hainmueller, and Dominik Hangartner. 2016. How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science 354: 217–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bereiter, Carl, and Marlene Scardamalia. 1993. Surpassing Ourselves: An Inquiry into the Nature and Implications of Expertise. Chicago: Open Court. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, John. 1999. Teaching for Quality Learning at University. What the Student Does. London: Society for Research into Higher Education. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, Stephen. 2001. Learning throughout working life: Interdependencies at work. Studies in Continuing Education 23: 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, Stephen. 2002. Critiquing workplace learning discourses: Participation and continuity at work. Studies in the Education of Adults 34: 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, Stephen. 2004a. Learning through work: Workplace participatory practices. In Workplace Learning in Context. Edited by Alison Fuller, Anne Munro and Helen Rainbird. London: Routledge, pp. 109–25. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, Stephen. 2004b. Workplace Participatory Practices: Conceptualising workplaces as learning environments. The Journal of Workplace Learning 16: 312–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, Stephen. 2008. Personal epistemologies, work, and learning. Educational Research Review 4: 210–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, Stephen. 2011. Subjectivity, self and personal agency in learning through and for work. In The SAGE Handbook of Workplace Learning. Edited by Margaret Malloch, Len Cairns, Karen Evans and Bridget N. O’Connor. London: SAGE, pp. 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, Stephen. 2015. Integrating Practice-Based Experiences into Higher Education. Professional and Practice-Based Learning. Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, Len. 2011. Learning in the workplace: Communities of practice and beyond. In The SAGE Handbook of Workplace learning. Edited by Margaret Malloch, Len Cairns, Karen Evans and Bridget N. O’Connor. London: SAGE, pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Selena. 2016. Belonging to a workplace: First-year apprentices’ perspectives on factors determining engagement and continuation through apprenticeship. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance 16: 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, Alicia Fedelina, and Susan Diana Longerbeam. 2016. Teaching Across Cultural Strengths: A Guide to Balancing Integrated and Individuated Cultural Frameworks in College Teaching. Sterling: Stylus Publishing, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Dehnbostel, Peter, and Thomas Schröder. 2017. Work-based and work-related learning—Models and learning concepts. TVET Online Asia 9: 1–16. Available online: www.tvet-online.asia (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Delander, Lennart, Mats Hammarstedt, Jonas Månsson, and Erik Nyberg. 2005. Integration of immigrants: The role of language proficiency and experience. Evaluation Review 29: 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervin, Fred. 2016. Interculturality in Education: A Theoretical and Metaphorical Toolbox. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, Karen. 2009. Language and inclusion in mainstream classrooms. In Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Classrooms: New Dilemmas for Teachers. Edited by J. Miller, A. Kostogriz and M. Gearon. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, Eva, Marianne Teräs, and Ali Osman. 2022. ‘Back to work’—Factors facilitating migrants’ re-entry into their previous vocations. Journal of Education and Work 35: 828–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvira, Quincy, Joroen Imants, Ben Dankbaar, and Mien Segers. 2016. Designing education for professional expertise development. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 61: 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eteläpelto, Anneli, Katja Vähäsantanen, Päivi Hökkä, and Susanna Paloniemi. 2013. What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review 10: 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eteläpelto, Anneli, Virpi-Liisa Kykyri, Markku Penttonen, Päivi Hökkä, S. Paloniemi, Katja Vähäsantanen, T. Eteläpelto, and V. Lappalainen. 2018. A multi-componential methodology for exploring emotions in learning: Using self-reports, behaviour registration, and physiological indicators as complementary data. Frontline Learning Research 6: 6–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filliettaz, Laurent. 2011. Collective Guidance at Work: A Resource for Apprentices? Journal of Vocational Education and Training 63: 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filliettaz, Laurent. 2013. Affording learning environments in workplace contexts: An interactional and multimodal perspective. International Journal of Lifelong Education 32: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Alison, and Lorna Unwin. 2004. Expansive learning environments: Integrating organizational and personal development. In Workplace Learning in Context. Edited by Alison Fuller, Anne Munro and Helen Rainbird. London: Routledge, pp. 126–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhards, Jürgen, Lukas Antoine, and Rasmus Ollroge. 2019. The Liberal Script on State Sovereignty and the Admission of Immigrants. Do Citizens Distinguish Between Voluntary and Forced Immigrants? [Scripts Working Paper no. 28]. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin. Available online: https://www.scripts-berlin.eu/publications/working-paper-series/Working-Paper-28-2023/SCRIPTS_Working_Paper_28_WEB.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Goller, Michael, and Susanna Paloniemi, eds. 2017. Agency at Work: An Agentic Perspective on Professional Learning and Development. Professional and Practice-Based Learning. Heidelberg: Springer, vol. 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, Kris D., and Barbara Rogoff. 2003. Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educational Researcher 32: 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, Mariane, and Seth Chaiklin. 2005. Radical-Local Teaching and Learning: A Cultural-Historical Approach. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen, Hannu L. T., Päivi Tynjälä, and Ulla Kiviniemi. 2011. Integrative pedagogy in practicum: Meeting the second order paradox of teacher education. In A Practicum Turn in Teacher Education. Edited by Matts Mattsson, Tor Vidar Eilertsen and Doreen Rorrison. Rotterdam: Sense, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, Laura, Päivi Tynjälä, Erkki Olkinuora, and Kirsti Lonka. 2007. ‘Ain’t nothin’ like the real thing’: Motivation and study processes on a work-based project course in information systems design. British Journal of Educational Psychology 77: 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, J. M., G. Robertson, R. Walker, M. A. Adey, and I. Nixon. 2003. Bridging the gap between degree programme curricula and employability through implementation of work-related learning. Teaching in Higher Education 8: 211–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hökkä, Päivi, Katja Vähäsantanen, Susanna Paloniemi, Sanna Herranen, and Anneli Eteläpelto. 2019. Emotions in leaders’ enactment of professional agency. Journal of Workplace Learning 31: 143–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskelä, Päivikki, Anna-Maija Poikkeus, Kati Vasalampi, Ulla Maija Valleala, and Helena Rasku-Puttonen. 2017. Assessing agency of university students: Validation of the AUS scale. Studies in Higher Education 42: 2061–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskelä, Päivikki, Anna-Maija Poikkeus, Päivi Häkkinen, Kati Vasalampi, Helena Rasku-Puttonen, and Asko Tolvanen. 2020a. Students’ agency profiles in relation to student-perceived teaching practices in university courses. International Journal of Educational Research 103: 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskelä, Päivikki, Ville Heilala, Tommi Kärkkäinen, and Päivi Häkkinen. 2020b. Student agency analytics: Learning analytics as a tool for analyzing student agency in higher education. Behaviour & Information Technology 40: 790–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalonaityte, Viktorija. 2010. The Case of vanishing borders: Theorizing diversity management as internal border control. Organization 17: 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärkkäinen, Katarzyna. 2017. Learning, Teaching and Integration of Adult Migrants in Finland. Jyväskylä Studies in Education, Psychology and Social Sciences 594. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. [Google Scholar]

- Kärkkäinen, Katarzyna, and Mirja Tarnanen. 2022. Teachers’ and adult migrant students’ perspectives on integration in the context of Finnish vocational education. In Migration and Inclusion in Worklife—The Role of VET. Edited by Lázaro Moreno Herrera, Marianne Teräs, Petros Gougoulakis and Janne Kontio. Emerging Issues in Research on Vocational Education and Training. Stockholm: Research Book Series of Stockholm University, vol. 7, pp. 373–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kember, David, Doris Y. P. Leung, and Rosa S. F. Ma. 2007. Characterizing learning environments capable of nurturing generic capabilities in higher education. Research in Higher Education 48: 609–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketonen, Elina E., Julia Dietrich, Julia Moeller, Katariina Salmela-Aro, and Kristi Lonka. 2018. The role of daily autonomous and controlled educational goals in students’ academic emotion states: An experience sampling method approach. Learning and Instruction 53: 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Young Yun. 2001. Becoming Intercultural: An Integrative Theory of Communication and Cross-Cultural Adaptation. New York: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt, Eva, and Herman Baert. 2013. Antecedents of Employees’ Involvement in Work-Related Learning: A Systematic Review. Review of Educational Research 83: 273–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, Malgorzata. 2015. Communicating Interculturality in the Workplace. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities 262. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Legitimate peripheral participation in communities of practice. In Supporting Lifelong Learning. Edited by Julia Clarke, Ann Hanson, Roger Harrison and Fiona Reeve. London: Routledge, vol. 1, pp. 121–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtimaja, Inkeri, and Salla Kurhila. 2018. Sairaanhoitajan ammatillisen kielitaidon kehittäminen työyhteisössä. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto, Soveltavan kielentutkimuksen keskus, Kielikoulutuspolitiikan verkosto. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Xue, and Geoffrey Q. P. Shen. 2020. How formal and informal intercultural contacts in universities influence students’ cultural intelligence? Asia Pacific Education Review 21: 245–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsick, Victoria, Karen Watkins, and Bridget N. O’Connor. 2011. Researching workplace learning in the United States. In The SAGE Handbook of Workplace Learning. Edited by Margaret Malloch, Len Cairns, Karen Evans and Bridget N. O’Connor. London: SAGE, pp. 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkonen, Susanna, Laura Pylväs, Heta Rintala, Petri Nokelainen, and Liisa Postareff. 2017. Guiding workplace learning in vocational education and training: A literature review. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training 9: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, Sanna, Pauliina Puranen, and Minna Suni. 2020. Maahanmuuttotaustaisten Opiskelijoiden Tasa-Arvoisen Osallisuuden Tukeminen Ammatillisessa Koulutuksessa. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto, Soveltavan kielentutkimuksen keskus, Kielikoulutuspolitiikan verkosto. [Google Scholar]

- Näre, Lena. 2013. Ideal workers and suspects: Employers’ Politics of Recognition and the Migrant Division of Care Labour in Finland. Nordic Journal of Migration Research 3: 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näre, Lena, and Olivia Maury. 2024. Multiple sources of precarity: Bureaucratic bordering of temporary migrants in a Nordic welfare state. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 50: 2729–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndomo, Quivine. 2024. The Working Underclass: Highly Educated Migrants on the Fringes of the Finnish Labour Market. JYU Dissertations 744. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-9906-3 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Ortoleva, Guilia, and Mireille Bétrancourt. 2016. Supporting productive collaboration in a computer-supported instructional activity: Peer-feedback on critical incidents in health care education. Journal of Vocational Education & Training 68: 178–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, Django. 2012. Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher 41: 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Enni. 2023. ‘The wrong’ kind of students or ‘Santa’s workshop’? Teaching practices for newly arrived migrant students in Swedish upper secondary VET. Vocations and Learning 16: 157–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, Jon, Sharon Mavin, and Brenda Stalker. 2007. Scratching beneath the surface of communities of practice. Learning Organization 14: 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Celia. 2012. Translating global experience into institutional models of competency: Linguistic inequalities in the job interview. Diversities 14: 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sandwall, Karin. 2010. “I Learn More at School”: A Critical Perspective on Workplace-Related Second Language Learning In and Out of School. TESOL Quarterly 44: 542–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandwall, Karin. 2013. Att hantera praktiken—Om sfi-studerandes möjligheter till interaktion och lärande på praktikplatser. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg. [Google Scholar]

- Strömmer, Maiju. 2017. Mahdollisuuksien rajoissa: Neksusanalyysi suomen kielen oppimisesta siivoustyössä. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities 336. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä. Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/56113 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Suni, Minna. 2017. Working and learning in a new niche: Ecological interpretations of work-related migration. In Negotiating Boundaries at Work: Talking and Transitions. Edited by Jo Angouri, Meredith Marra and Janet Holmes. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Talvio, Markus, and Kirsti Lonka. 2021. How to create a flourishing classroom? An intervention protocol for enhancing teachers’ social and emotional learning. In Positive Psychological Interventions: Theories, Methodologies and Applications Within Multicultural Contexts. Edited by Llewellyn Ellardus van Zyl and Sebastiaan Rothmann. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 315–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnanen, Mirja, and Sari Pöyhönen. 2011. Maahanmuuttajien suomen kielen taidon riittävyys ja työllistymisen mahdollisuudet. Puhe ja kieli 3: 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- Täks, Marge, Päivi Tynjälä, Martin Toding, Hasso Kukemelk, and Urve Venesaar. 2014. Engineering students’ experiences in studying entrepreneurship. Journal of Engineering Education 103: 573–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynjälä, Päivi. 2008. Perspectives into learning at the workplace. Educational Research Review 3: 130–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynjälä, Päivi. 2013. Toward a 3-P model of workplace learning: A Literature review. Vocations and Learning 6: 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tynjälä, Päivi, Anne Virtanen, Maarit H. Virolainen, and Hannu L. T. Heikkinen. 2022a. Learning at the interface of higher education and work: Experiences of students, teachers and workplace partners. In Developing Connectivity Between Education and Work: Principles and Practices. Edited by Eva Kyndt, Simon Beausaert and Ilya Zitter. London: Routledge, pp. 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynjälä, Päivi, Anne Virtanen, Ulla Klemola, Emm Kostiainen, and H. Rasku-Puttonen. 2016. Developing social competence and other generic skills in teacher education: Applying the model of integrative pedagogy. European Journal of Teacher Education 39: 368–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynjälä, Päivi, Hannu L. T. Heikkinen, and Eva K. Kallio. 2022b. Integrating Work and Learning in Higher Education and VET: Theoretical point of view. In The SAGE Handbook of Learning and Work. Edited by Margaret Malloch, Len Cairns, Karen Evans and Bridget N. O’Connor. New York: SAGE, pp. 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tynjälä, Päivi, Maarit Virolainen, Hannu L. T. Heikkinen, and Anne Virtanen. 2020. Promoting cooperation between educational institutions and workplaces. Models of Integrative Pedagogy and Connectivity revisited. In Connectivity and Integrative Competence Development in Vocational and Professional Education and Training (VET/PET). Edited by Carmela Aprea, Viviana Sappa and Ralf Tenberg. Zeitschrift für Berufspädagogik, Beiheft, 29. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tynjälä, Päivi, Maritta Pirhonen, Tero Vartiainen, and Laura Helle. 2009. Educating IT project managers through project-based learning: A working-life perspective. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 24: 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2007. Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30: 1024–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, Luis E., Pedro J. Perez, and Francisco G. Morillas. 2012. Higher education and the development of competencies for innovation in the workplace. Management Decision 50: 1634–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, Anne, and Päivi Tynjälä. 2008. Students’ experiences of workplace learning in Finnish VET. European Journal of Vocational Training 2: 199–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, Anne, and Päivi Tynjälä. 2019. Factors explaining the learning of generic skills: A study of university students’ experiences. Teaching in Higher Education 24: 880–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, Anne, Kirsti Lauritsalo, Tommi Mäkinen, Heikki Hurskainen, and Päivi Tynjälä. 2022. The role of positive atmosphere on learning generic skills in higher education—Experiences of physical education students. Frontiers in Education 7: 886139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, Anne, Päivi Tynjälä, and Anneli Eteläpelto. 2014. Factors promoting vocational students’ learning at work: Study on student experiences. Journal of Education and Work 27: 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, Tony, Ly Thi Tran, and Sri Soejatminah. 2017. Inequalities and agencies in workplace learning experiences: International student perspectives. Vocations and Learning 10: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, Etienne. 1998. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, Etienne, Richard McDermott, and William M. Snyder. 2002. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).