Protective Factors for Marijuana Use and Suicidal Behavior Among Black LGBQ U.S. High School Students

Abstract

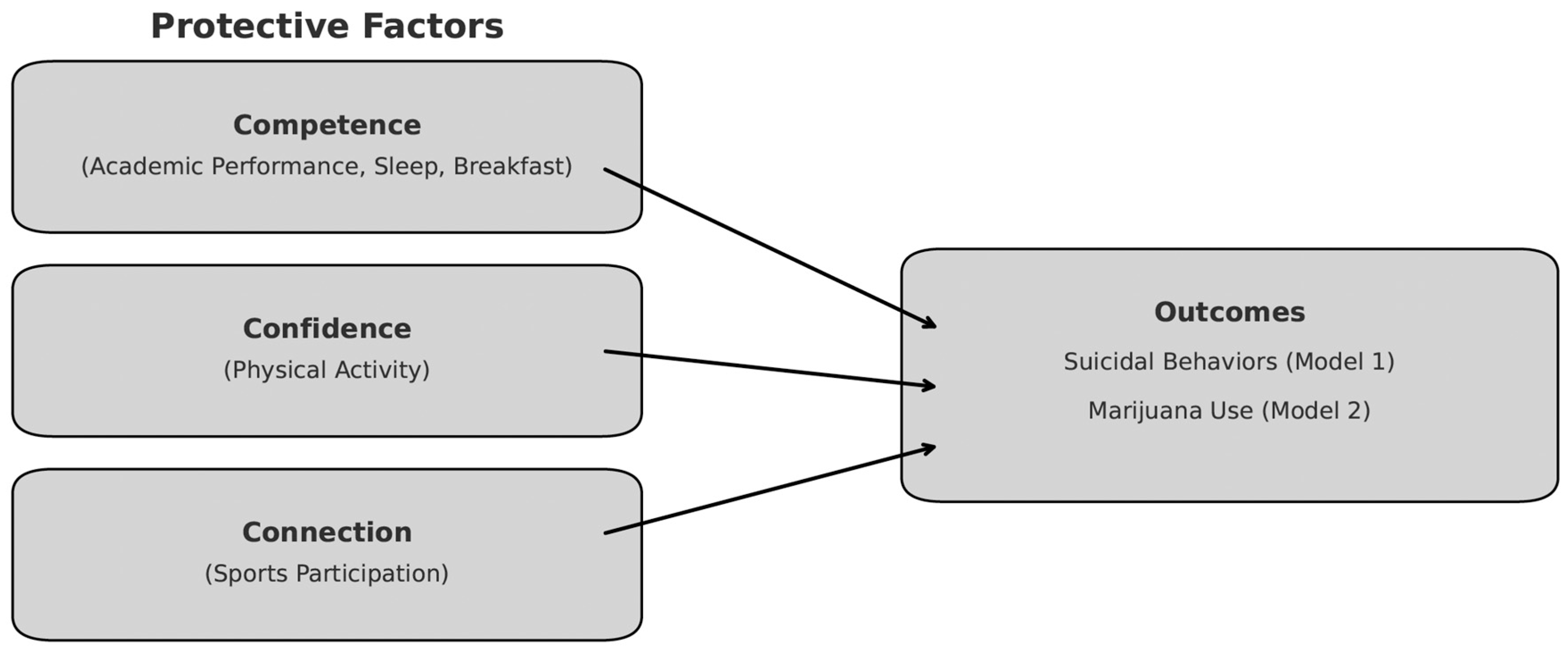

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Protective Factors for Suicide and Marijuana Use

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.3. The Current Study

3. Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Sample

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Dependent Variables

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

5.2. Implications for Policy, Practice, and Education

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almeida, Joanna, Renee M. Johnson, Heather L. Corliss, Beth E. Molnar, and Deborah Azrael. 2009. Emotional Distress among LGBT Youth: The Influence of Perceived Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 38: 1001–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranmolate, Rasaki, Danielle R. Bogan, Tiffany Hoard, and Anthony R. Mawson. 2017. Suicide risk factors among LGBTQ youth. JSM Schizophrenia 2: 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arensman, Ella, Vanda Scott, Diego De Leo, and Jane Pirkis. 2020. Suicide and Suicide Prevention from a Global Perspective. In Suicide and Suicide Prevention from a Global Perspective. Edited by Ella Arensman, Diego De Leo and Jane Pirkis. Göttingen: Hogrefe, pp. S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ati, Niken A. L., Mareta D. Paraswati, and Heni D. Windarwati. 2021. What Are the Risk Factors and Protective Factors of Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents? A Systematic Review. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 34: 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, Peter C., Ian R. White, Douglas S. Lee, and Stef van Buuren. 2021. Missing Data in Clinical Research: A Tutorial on Multiple Imputation. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 37: 1322–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiss, Lindsay A., and James E. Gangwisch. 2009. Sports Participation as a Protective Factor against Depression and Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents as Mediated by Self-Esteem and Social Support. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP 30: 376–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiden, Philip, Catherine A. LaBrenz, Yi Jin Kim, Jennifer J. Muehlenkamp, and Shawndaya Thrasher. 2023. Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts Among Black Adolescents Based on the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Black Psychology 49: 319–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiden, Philip, Savarra K. Tadeo, Betty C. Tonui, Jaylon D. Seastrunk, and Godfred O. Boateng. 2020. Association between Insufficient Sleep and Suicidal Ideation among Adolescents. Psychiatry Research 287: 112579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barksdale, Crystal L., Melissa Azur, and Philip J. Leaf. 2010. Differences in Mental Health Service Sector Utilization among African American and Caucasian Youth Entering Systems of Care Programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 37: 363–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Greta R. 2014. Incorporating Intersectionality Theory into Population Health Research Methodology: Challenges and the Potential to Advance Health Equity. Social Science & Medicine 110: 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkett, Michelle, Stephen T. Russell, and Heather L. Corliss. 2014. Sexual-Orientation Disparities in School: The Mediational Role of Indicators of Victimization in Achievement and Truancy Because of Feeling Unsafe. American Journal of Public Health 104: 1124–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, Edmond P., Steinunn Gestsdottir, and G. John Geldhof. 2011. Developmental Trajectories of Intentional Self Regulation in Adolescence: The Role of Parenting and Implications for Positive and Problematic Outcomes among Diverse Youth. Journal of Adolescence 34: 1193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowleg, Lisa. 2012. The Problem with the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—An Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health 102: 1267–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, Julia, Tobias Teismann, and Jürgen Margraf. 2018. Cyberbullying, Positive Mental Health and Suicide Ideation/Behavior. Psychiatry Research 267: 240–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, Nancy D., Laura Kann, Shari Shanklin, Steve Kinchen, Danice K. Eaton, Joseph Hawkins, and Katherine H. Flint. 2013. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System-2013. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 62: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, Jeffrey A., Lisa M. Horowitz, Cynthia A. Fontanella, Arielle H. Sheftall, Joel Greenhouse, Kelly J. Kelleher, and John V. Campo. 2018. Age-Related Racial Disparity in Suicide Rates among US Youths from 2001 through 2015. JAMA Pediatrics 172: 697–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caputi, Theodore L., Davey Smith, and John W. Ayers. 2017. Suicide Risk Behaviors Among Sexual Minority Adolescents in the United States, 2015. JAMA 318: 2349–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, James R., and Michael G. Kenward. 2012. Multiple Imputation and Its Application. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Mendes, Rubia P., Gideon P. Dunster, Horacio O. de la Iglesia, and Luiz Menna-Barreto. 2020. Afternoon School Start Times Are Associated with a Lack of Both Social Jetlag and Sleep Deprivation in Adolescents. Journal of Biological Rhythms 35: 377–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Data & Documentation. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/data.htm (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Clark, Caitlin M., and Joseph G. Kosciw. 2022. Engaged or Excluded: LGBTQ Youth’s Participation in School Sports and Their Relationship to Psychological Well-Being. Psychology in the Schools 59: 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudatos, Stephanie, Fiona C. Baker, and Brant P. Hasler. 2019. Relevance of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms to Adolescent Substance Use. Current Addiction Reports 6: 504–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Gender, Black Feminism, and Black Political Economy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 568: 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Benjamin Lê, Colleen L. Barry, and Susan H. Busch. 2013. Racial/Ethnic Disparity Trends in Children’s Mental Health Care Access and Expenditures from 2002 to 2007. Health Services Research 48: 129–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Timothy N., and S. Lee Ridner. 2018. Differences in Well-Being between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual College Students. Journal of LGBT Youth 15: 243–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Ronald E. 2004. Adolescent Brain Development: A Period of Vulnerabilities and Opportunities. Keynote Address. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1021: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defeyter, Margaret Anne, and Riccardo Russo. 2013. The Effect of Breakfast Cereal Consumption on Adolescents’ Cognitive Performance and Mood. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7: 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas, Jorge-Manuel, Matheus Fernández, and Fàbia Morales-Vives. 2020. What Is the Protective Role of Perceived Social Support and Religiosity in Suicidal Ideation in Young Adults? Journal of General Psychology 147: 432–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Marla E., Amy L. Gower, Ryan J. Watson, G. Nic Rider, De’Shay Thomas, and Stephen T. Russell. 2022. Substance Use Behaviors Among LGBTQ+ Youth of Color: Identification of the Populations Bearing the Greatest Burden in Three Large Samples. Journal of Adolescent Health 71: 317–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Marla E., and Michael D. Resnick. 2006. Suicidality among Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Youth: The Role of Protective Factors. Journal of Adolescent Health 39: 662–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitle, Tamela McNulty, and David J. Eitle. 2002. Race, Cultural Capital, and the Educational Effects of Participation in Sports. Sociology of Education 75: 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, Jessica N., Meg D. Bishop, and Stephen T. Russell. 2021. Developmental Differences in Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity–Related Substance Use Disparities: Findings from Population-Based Data. Journal of Adolescent Health 68: 1162–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricke, Julie, and Maria Sironi. 2017. Dimensions of Sexual Orientation and Sleep Disturbance among Young Adults. Preventive Medicine Reports 8: 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulginiti, Anthony, Harmony Rhoades, Mary Rose Mamey, Cary Klemmer, Ankur Srivastava, Garrett Weskamp, and Jeremy T. Goldbach. 2021. Sexual Minority Stress, Mental Health Symptoms, and Suicidality among LGBTQ Youth Accessing Crisis Services. Journal of Youth and Adolescence: A Multidisciplinary Research Publication 50: 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, Jayne A., Nancy E. Sherwood, Cheryl L. Perry, Dianne Neumark-Sztainer, and Mary Story. 2004. Depressive Symptoms and Adolescent Eating and Health Behaviors: A Multifaceted View in a Population-Based Sample. Preventive Medicine 38: 865–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, Adriana. 2020. The Need for Sleep in the Adolescent Brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 24: 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G. John, Jennifer A. Malin, Amy L. Johnson, Matthew J. Hilliard, Edmond P. Bowers, and Richard M. Lerner. 2015. Adolescent Thriving: The Role of Sparks, Relationships, and Empowerment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 44: 947–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Paul. 1989. Gay Male and Lesbian Youth Suicide. Report to the Secretary’s Task Force on Youth Suicide: Vol. 3. Prevention and Intervention in Youth Suicide; Edited by Marcia Feinleib. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, pp. 110–42.

- Golub, Andrew, Bruce D. Johnson, and Eloise Dunlap. 2005. The Growth in Marijuana Use Among American Youths During the 1990s and the Extent of Blunt Smoking. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 4: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, Marie, and Teena Willoughby. 2010. Evaluating the Direction of Effects in the Relationship between Religious versus Non-Religious Activities, Academic Success, and Substance Use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 40: 680–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Arnold H., Adam P. Haney, Perry Edwards, Edward J. Alessi, Maya Ardon, and Tamika Jarrett Howell. 2009. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth Talk about Experiencing and Coping with School Violence: A Qualitative Study. Journal of LGBT Youth 6: 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Lande, Jennifer A., Marla E. Eisenberg, and Sandra L. Christenson. 2007. Social Isolation, Psychological Health, and Protective Factors in Adolescence. Adolescence (San Diego): An International Quarterly Devoted to the Physiological, Psychological, Psychiatric, Sociological, and Educational Aspects of the Second Decade of Human Life 42: 265. [Google Scholar]

- Hatchel, Tyler, Dorothy Espelage, and Gabriel J. Merrin. 2019. Peer Victimization and Suicidality among LGBTQ Youth: The Roles of School Belonging, Self-Compassion, and Parental Support. Journal of LGBT Youth 16: 134–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatchel, Tyler, Joshua R. Polanin, and Dorothy L. Espelage. 2021. Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors among LGBTQ Youth: Meta-Analyses and a Systematic Review. Archives of Suicide Research 25: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, Mark L. 2011. The Social Environment and Suicide Attempts in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. Pediatrics 127: 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hextrum, Kirsten. 2020. Socializing Sport: How Academic Exclusion and Athletic Inclusion Draw Black Youth to Sport. Journal of Contemporary Athletics 14: 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hillard, Pamela, Lisa Love, Heather M. Franks, B. A. Laris, and Karin K. Coyle. 2014. ‘They Were Only Joking’: Efforts to Decrease LGBTQ Bullying and Harassment in Seattle Public Schools. Journal of School Health 84: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holman, Mikayla S., and Matt N. Williams. 2022. Suicide Risk and Protective Factors: A Network Approach. Archives of Suicide Research 26: 137–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Jun Sung, Alberto Valido, Matthew M. Koehl-Rivas, Ryan M. Wade, Dorothy L. Espelage, and Dexter R. Voisin. 2021. Bullying Victimization, Psychosocial Functioning, and Protective Factors: Comparing African American Heterosexual and Sexual Minority Adolescents in Chicago’s Southside. Journal of Community Psychology 49: 1358–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Jun Sung, Dorothy L. Espelage, and Michael J. Kral. 2011. Understanding Suicide among Sexual Minority Youth in America: An Ecological Systems Analysis. Journal of Adolescence 34: 885–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, Victoria A., Noah T. Kreski, and Katherine M. Keyes. 2023. Sleep Deprivation and Suicide Risk among Minoritized US Adolescents. BMC Psychiatry 23: 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Karim M., Angela M. Thompson, Steven N. Blair, James F. Sallis, Kenneth E. Powell, Fiona C. Bull, and Adrian E. Bauman. 2012. Sport and Exercise as Contributors to the Health of Nations. The Lancet 380: 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulick, Alex, Laura J. Wernick, Mario Alberto V. Espinoza, Tarkington J. Newman, and Adrienne B. Dessel. 2019. Three Strikes and You’re Out: Culture, Facilities, and Participation among LGBTQ Youth in Sports. Sport, Education and Society 24: 939–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latino, Francesca, Francesco Tafuri, Emma Saraiello, and Domenico Tafuri. 2023. Classroom-Based Physical Activity as a Means to Improve Self-Efficacy and Academic Achievement among Normal-Weight and Overweight Youth. Nutrients 15: 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Hae Jeong, Cheol Hong Kim, Intae Han, and Sung Hoon Kim. 2019. Emotional State According to Breakfast Consumption in 62276 South Korean Adolescents. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics 29: e92193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, Nathalia, Janaina Weissheimer, and Sidarta Ribeiro. 2014. Naps in School Can Enhance the Duration of Declarative Memories Learned by Adolescents. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 8: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, Richard M. 2009. The Positive Youth Development Perspective: Theoretical and Empirical Bases of a Strengths-Based Approach to Adolescent Development. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 148–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Richard M., Jacqueline V. Lerner, Erin Phelps, Colleen M. Bowers, Selva Lewin-Bizan, Audun Dahl, Jennifer S. Lerner, Pamela M. Weiner, Kristin DeSouza, and Alexander J. Smith. 2013. The Positive Development of Youth: Comprehensive Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Chevy Chase: National 4-H Council. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Richard M., Jacqueline V. Lerner, Jason B. Almerigi, Christina Theokas, Erin Phelps, Steinunn Gestsdottir, Sophie Naudeau, Helena Jelicic, Amy Alberts, Lang Ma, and et al. 2005. Positive Youth Development, Participation in Community Youth Development Programs, and Community Contributions of Fifth-Grade Adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence 25: 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Xun, Shi-Ting Xiang, and Jie Dong. 2022. The Concurrence of Sexual Violence and Physical Fighting among Adolescent Suicide Ideators and the Risk of Attempted Suicide. Scientific Reports 12: 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, Michael A., Arielle H. Sheftall, Yunyu Xiao, and Sean Joe. 2019. Trends of Suicidal Behaviors among High School Students in the United States: 1991–2017. Pediatrics 144: e20191187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Bermudez, Esther, Diego Gomez-Baya, Elena Planells, and Jorge Molina-Lopez. 2024. The Mediational Role of Positive Youth Development in the Relationship between Physical Activity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents from Urban and Rural Environments. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 29: 2354917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, Martina, Nicklas Ennab Vogel, and Lars-Åke Levin. 2019. Effects of Eating Breakfast on Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Potentially Relevant Outcomes in Economic Evaluations. Food & Nutrition Research 63: 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Frances L., Edward L. Peterson, Christine Y. Lu, Yong Hu, Rebecca C. Rossom, Beth E. Waitzfelder, Ashli A. Owen-Smith, Samuel Hubley, Deepak Prabhakar, L. Keoki Williams, and et al. 2020. Substance Use Disorders and Risk of Suicide in a General US Population: A Case Control Study. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 15: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal, Michael P., Laura J. Dietz, Mark S. Friedman, Ron Stall, Helen A. Smith, James McGinley, Brian C. Thoma, Pamela J. Murray, Anthony R. D’Augelli, and David A. Brent. 2011. Suicidality and Depression Disparities between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Adolescent Health 49: 115–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereish, Ethan H., Luis A. Parra, Ryan J. Watson, and Jessica N. Fish. 2022. Subtle and Intersectional Minority Stress and Depressive Symptoms Among Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents of Color: Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Sense of Mastery. Prevention Science: Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research 23: 142–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Ilan H. 2003. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin 129: 674–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, Ilan H., Jessica Dietrich, and Sharon Schwartz. 2008. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Suicide Attempts in Diverse Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations. American Journal of Public Health 98: 1004–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, Shannon L., Richard Lowry, Caitlin Merlo, Adina C. Cooper, Eric T. Hyde, and Richard McKeon. 2020. Physical Activity, Sedentary, and Dietary Behaviors Associated with Indicators of Mental Health and Suicide Risk. Preventive Medicine Reports 19: 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, LaTrice, and Dale Mantey. 2018. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Prevalence and Correlates of Blunt Smoking among Adolescents. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 50: 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, Raymond L., Tyrel J. Starks, Christian Grov, and Jeffrey T. Parsons. 2018. Internalized Homophobia and Drug Use in a National Cohort of Gay and Bisexual Men: Examining Depression, Sexual Anxiety, and Gay Community Attachment as Mediating Factors. Archives of Sexual Behavior: The Official Publication of the International Academy of Sex Research 47: 1133–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlock, Sherry Davis, Samantha Matlin, Crystal Barksdale, Rupa Puri, and Joseph Lyles. 2008. Developing Suicide Prevention Programs for African American Youth in African American Churches. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 38: 323–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, Anna S., Wesley James, Seth Abrutyn, and Martin L. Levin. 2015. Suicide ideation and bullying among US adolescents: Examining the intersections of sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity. American Journal of Public Health 105: 980–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnan, Judy, and James H. Price. 2004. The Role of Health Education in the Prevention of Youth Violence. American Journal of Health Studies 19: 114–21. [Google Scholar]

- Murry, Velma McBride, Craig Anne Heflinger, and Sarah V. Suiter. 2011. Examining Perceptions about Mental Health Care and Help-Seeking among Rural African American Families of Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 40: 1118–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, Belinda L., and Erika L. Austin. 2010. Sexual Orientation, Parental Support, and Health during the Transition to Young Adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39: 1189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, Emily O’Malley, Laura Kann, Alana Vivolo-Kantor, Steve Kinchen, and Tim McManus. 2014. School Violence and Bullying among Sexual Minority High School Students, 2009–2011. Journal of Adolescent Health 55: 432–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opara, Ijeoma, Sitara M. Weerakoon, Jasmin R. Brooks Stephens, Taylor Choe, John F. Gunn, 3rd, and Shawndaya S. Thrasher. 2025. Relationship between Suicide Ideation and Attempts, Bully Victimization, Dating Violence, and Depressive Symptoms among Black and Hispanic Youth. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 55: e13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira da Silva, Maynara Priscila, Evandro Morais Peixoto, Bartira Pereira Palma, and Marcos Alencar Abaide Balbinotti. 2024. Exploring the Networks of Relationships between the 5cs of Positive Youth Development through Sport. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 27: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Rodriguez, M. Mercedes, Enrique Baca-Garcia, Maria A. Oquendo, and Carlos Blanco. 2008. Ethnic Differences in Suicidal Ideation and Attempts. Primary Psychiatry 15: 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Michael R. 2010. Rethinking the Role of Mental Illness in Suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry 167: 731–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, James H., Joseph A. Dake, and Ruthie Kucharewski. 2001. Assets as Predictors of Suicide Attempts in African American Inner-City Youths. American Journal of Health Behavior 25: 367–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ream, Geoffrey L. 2019. What’s Unique About Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth and Young Adult Suicides? Findings From the National Violent Death Reporting System. Journal of Adolescent Health 64: 602–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverdito, Riller Silva, Sofia Fonseca, Antonio Lopes, Karyna Aires, Luciano Santos Alves, Leilane Alves de Lima, Mayara de Almeida Tavares, and Carlos Gonçalves. 2023. Sources of Sport Satisfaction and Perceived Self-Efficacy among Youth in a Competitive Environment. Perceptual and Motor Skills 130: 1221–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Robert E., and Hao T. Duong. 2015. Is There an Association between Adolescent Sleep Restriction and Obesity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 79: 651–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robin, Leah, Nancy D. Brener, Shaun F. Donahue, Tim Hack, Kelly Hale, and Carol Goodenow. 2002. Associations Between Health Risk Behaviors and Opposite-, Same-, and Both-Sex Sexual Partners in Representative Samples of Vermont and Massachusetts High School Students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 156: 349–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Joseph P., and Dorothy L. Espelage. 2011. Inequities in Educational and Psychological Outcomes Between LGBTQ and Straight Students in Middle and High School. Educational Researcher 40: 315–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Joseph P., and Dorothy L. Espelage. 2012. Bullying Explains Only Part of LGBTQ—Heterosexual Risk Disparities: Implications for Policy and Practice. Educational Researcher 41: 309–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Dooley, Vanessa. 2022. Beyond Moving the Ball in Youth Sports: Making the Case for Mental Health for Black Youth. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Donald B. 1987. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. In Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runcan, Remus. 2020. Adolescent Substance Use, Misuse, and Abuse. Agora Psycho-Pragmatica 14: 136–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Caitlin, Stephen T. Russell, David Huebner, Rafael Diaz, and Jorge Sanchez. 2010. Family Acceptance in Adolescence and the Health of LGBT Young Adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 23: 205–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, Joseph L. 1999. Multiple Imputation: A Primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 8: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, Gillian L., Heather B. Clayton, Rashid Njai, and Althea M. Grant. 2020. Adolescent Marijuana Use and Related Risk Behaviors, National Findings From 2015 to 2017. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 59: 714–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, Lawrence M., and Kenneth W. Griffin. 2021. Youth Marijuana Use: A Review of Causes and Consequences. Current Opinion in Psychology 38: 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, John P., Kelly Whitaker, Jill Glassman, Heather M. Franks, and Kelli Howard. 2012. Impact of Victimization on Risk of Suicide Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual High School Students in San Francisco. Journal of Adolescent Health 50: 418–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, Jonathan A. C., Ian R. White, John B. Carlin, Michael Spratt, Patrick Royston, Michael G. Kenward, Angela M. Wood, and James R. Carpenter. 2009. Multiple Imputation for Missing Data in Epidemiological and Clinical Research: Potential and Pitfalls. BMJ 338: b2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, Megan, and Paul B. Perrin. 2016. Discrimination, Mental Health, and Suicidal Ideation among LGBTQ People of Color. Journal of Counseling Psychology 63: 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Trevor Project. 2019. National Survey on LGBTQ Mental Health. New York: The Trevor Project. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, Kimberly A., Tracy K. Witte, and Kelly C. Cukrowicz. 2010. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychological Review 117: 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veliz, Philip, Quyen Epstein-Ngo, Jennifer Zdroik, Carol J. Boyd, and Sean Esteban McCabe. 2016. Substance Use Among Sexual Minority Collegiate Athletes: A National Study. Substance Use & Misuse 51: 517–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, Emmy E., and Ruth S. Smith. 2019. Overcoming the Odds: High Risk Children from Birth to Adulthood. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, Kelly, Valerie B. Shapiro, and John P. Shields. 2016. School-Based Protective Factors Related to Suicide for Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 58: 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodland, Malcolm H. 2008. Whatcha Doin’ after School? A Review of the Literature on the Influence of After-School Programs on Young Black Males. Urban Education 43: 537–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Yingwei. 2023. Suicide Attempt and Suicide Plan among U.S. Adolescents: The Role of Repeated and Co-Occurring Violence Experiences. Psychiatry Research 320: 115040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yockey, Robert Andrew, and Tracey E. Barnett. 2023. Past-Year Blunt Smoking among Youth: Differences by LGBT and Non-LGBT Identity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 244 | 24.6 | ||

| Female | 743 | 75.3 | ||

| Missing | 4 | 0.4 | ||

| Age | 16.06 | 1.28 | ||

| 12 years or less | 6 | 0.61 | ||

| 13 years | 3 | 0.3 | ||

| 14 years | 3 | 11.1 | ||

| 15 years | 110 | 23.31 | ||

| 16 years | 231 | 25.13 | ||

| 17 years | 249 | 24.42 | ||

| 18 year or more | 242 | 15.04 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 0.09 | ||

| Sexual identity | ||||

| Gay/Lesbian | 220 | 22.2 | ||

| Bisexual | 528 | 53.3 | ||

| Questioning | 243 | 24.5 |

| Variables | % | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Suicidal behavior [yes] | 31.60% | - | |||||||||

| 2. Marijuana use [yes] | 51.87% | 0.13 ** | |||||||||

| [0.07, 0.20] | |||||||||||

| 3. Academic performance [yes] | 62.93% | −0.13 *** | −0.10 ** | - | |||||||

| [−0.19, −0.07] | [−0.16, −0.04] | ||||||||||

| 4. Physically active [yes] | 25.71% | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.06 | - | ||||||

| [−0.10, 0.02] | [−0.06, 0.07] | [−0.01, 0.12] | |||||||||

| 5. Sleep [yes] | 20.92% | −0.09 * | −0.10 * | −0.01 | 0.03 | - | |||||

| [−0.15, −0.02] | [−0.16, −0.04] | [−0.07, 0.06] | [−0.04, 0.09] | ||||||||

| 6. Eating breakfast [yes] | 78.60% | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.12 ** | 0.02 | - | ||||

| [−0.14, −0.01] | [−0.07, 0.06] | [−0.01, 0.11] | [0.06, 0.18] | [−0.05, 0.08] | |||||||

| 7. Sports team [yes] | 46.43% | 0.02 | 0.08 * | 0.04 | 0.25 *** | 0.00 | 0.11 ** | - | |||

| [−0.04, 0.09] | [0.02, 0.14] | [−0.03, 0.10] | [0.19, 0.31] | [−0.06, 0.06] | [0.05, 0.17] | ||||||

| 8. Age | 16.06 | 1.28 | −0.04 | 0.13 *** | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.08 * | −0.03 | −0.05 | - | |

| [−0.10, 0.02] | [0.07, 0.19] | [−0.05, 0.07] | [−0.11, 0.01] | [−0.15, 0.02] | [−0.09, 0.03] | [−0.12, 0.01] | |||||

| 9. Sex [female] | 75.30% | 0.06 | 0.14 *** | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.04 | ||

| [0.01, 0.13] | [0.08, 0.20] | [−0.04, 0.08] | [−0.04, 0.08] | [−0.11, 0.02] | [−0.07, 0.05] | [−0.05, 0.08] | [−0.10, 0.02] |

| Model 1: Suicidal Behavior | Model 2: Lifetime Marijuana Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Academic performance | 0.57 (0.41–0.78) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.43–0.86) | 0.004 |

| Physically active | 0.82 (0.56–1.20) | 0.311 | 0.99 (0.69–1.42) | 0.970 |

| Hours of Sleep | 0.61 (0.41–0.92) | 0.018 | 0.64 (0.43–0.97) | 0.034 |

| Eating breakfast | 0.69 (0.44–1.09) | 0.107 | 0.99 (0.69–1.42) | 0.971 |

| Sports team | 1.21 (0.85–1.72) | 0.287 | 1.46 (1.10–1.95) | 0.010 |

| Sex | 1.38 (0.97–1.96) | 0.073 | 2.01 (1.45–2.80) | <0.001 |

| Age in years | 0.92 (0.81–1.06) | 0.252 | 0.26 (0.13–0.54) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Griffin, D.; Thrasher, S.S.; Watts, K.J.; Baiden, P.; Maccio, E.M.; Tate, M. Protective Factors for Marijuana Use and Suicidal Behavior Among Black LGBQ U.S. High School Students. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050267

Griffin D, Thrasher SS, Watts KJ, Baiden P, Maccio EM, Tate M. Protective Factors for Marijuana Use and Suicidal Behavior Among Black LGBQ U.S. High School Students. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(5):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050267

Chicago/Turabian StyleGriffin, DeKeitra, Shawndaya S. Thrasher, Keith J. Watts, Philip Baiden, Elaine M. Maccio, and Miya Tate. 2025. "Protective Factors for Marijuana Use and Suicidal Behavior Among Black LGBQ U.S. High School Students" Social Sciences 14, no. 5: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050267

APA StyleGriffin, D., Thrasher, S. S., Watts, K. J., Baiden, P., Maccio, E. M., & Tate, M. (2025). Protective Factors for Marijuana Use and Suicidal Behavior Among Black LGBQ U.S. High School Students. Social Sciences, 14(5), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050267