1. Introduction

Culture significantly influences individual cognition, emotion, and behavior, particularly in a diverse and ideologically polarized society like the United States. Understanding the structure of value systems is important, especially given the limitations of traditional cultural frameworks such as Schwartz’s value theory (

Schwartz 1992) and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (

Hofstede 2001), which often focus on national or group averages and overlook individual variability.

Social science faces challenges in measuring culture and values effectively, as traditional frameworks have been extensively used across various disciplines to clarify concepts like institutional trust and social cohesion (

Hofstede et al. 2010;

Schwartz 1992,

2012). However, these frameworks often assume cultural homogeneity at the national level, which can obscure significant intra-societal variations and lead to ecological fallacies (

Boer and Fischer 2013;

Taras et al. 2010). This reliance on national averages confounds theory testing and diminishes validity, masking critical individual-level differences. To overcome these challenges, person-centered methodologies like LPA have emerged, allowing researchers to identify subgroups with distinct value configurations (

Morin et al. 2016;

Spurk et al. 2020).

The current study seeks to integrate Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s cultural frameworks within the U.S. context, aiming to enhance quantitative theory testing by addressing the heterogeneity often overlooked by traditional cultural research methods (

Schwartz 1992,

2006,

2012;

Hofstede 1980). While both frameworks have significantly influenced cultural studies, their differing theoretical foundations and analytical levels have resulted in parallel research traditions that limit opportunities for integration. Most cultural studies focus on mean-level differences between nations, which can obscure the individual diversity in cultural orientations (

Fischer and Schwartz 2011). Cultural values play a crucial role in shaping individual behavior and social interactions (

Schwartz 1992,

2012). Although Schwartz and Hofstede have laid the groundwork for understanding systematic variations in motivational orientations, much of the existing research has relied on national averages, treating populations as homogeneous and neglecting individual-level variability, particularly in diverse societies like the U.S. (

Fischer and Schwartz 2011). The current study adopts a person-centered approach to investigate cultural values among U.S. individuals, revealing a range of value profiles within a single national context.

Furthermore, the evolution of the concept of “national character” into structured frameworks of cultural values has been essential for understanding cultural priorities. However, empirical research often emphasizes national averages, leading to ecological fallacies that misattribute group characteristics to individuals (

Fischer and Derham 2016;

Taras et al. 2010).

Yeganeh (

2024) presents a conceptual framework that elucidates the complexities of cultural change, highlighting the impacts of modernization, demographic transitions, and globalization on value systems. His analysis contests the notion of national cultural homogeneity, instead illustrating the fluidity of cultural orientations in a globalized context. This perspective aligns with the current study’s aim to explore value diversity using person-centered methods (

Yeganeh 2024). Furthermore, this approach may obscure significant intra-national variability, especially in multicultural contexts where demographic factors contribute to diverse value orientations (

De Mooij and Beniflah 2017). While national means can be useful for mapping broad cultural differences, they often fail to capture the nuanced and varied value systems present within a nation (

Fischer and Derham 2016;

Oyserman et al. 2002;

Schwartz and Bardi 2001;

Taras et al. 2012). Research indicates that cultural values often vary more within nations than between them, with up to 90% of value orientation variance occurring at the individual level (

Steel et al. 2018;

Fischer et al. 2010;

van Hoorn 2015). For instance, ethnic groups in the U.S. may share converging value systems while also displaying significant individual differences. This intra-national variability challenges the reliance on national aggregates and emphasizes the need for a more nuanced analysis of culture as it manifests in individual experiences (

De Mooij and Beniflah 2017;

Taras et al. 2016;

Fischer and Poortinga 2012;

Matsumoto and Yoo 2006).

Scholarship increasingly advocates for a person-centered approach to cultural values, recognizing that individuals internalize multiple, sometimes conflicting, cultural narratives (

Cooper et al. 2020;

Na et al. 2010;

Vignoles et al. 2016). While Hofstede’s dimensions of Individualism-Collectivism and Power Distance align with Schwartz’s concepts of Autonomy vs. Embeddedness and Hierarchy vs. Egalitarianism, Hofstede’s Uncertainty Avoidance and Long-Term Orientation lack direct equivalents in Schwartz’s framework (

Kaasa 2021;

Minkov and Kaasa 2024). This suggests that although both frameworks enhance the understanding of cultural differences, their infrequent combined application at the individual level limits insights into how individuals assimilate various cultural narratives (

Benet-Martínez and Haritatos 2005;

Spencer-Rodgers et al. 2007;

Na et al. 2010;

Vignoles et al. 2016). Consequently, cultural values are essential for understanding how individuals and groups navigate the social landscape, influencing decision-making, interpersonal relationships, and social frameworks (

Schwartz 1992).

While Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks have significantly contributed to defining cross-cultural differences, their predominant use at the national level often obscures the variability within nations, particularly in multicultural societies like the United States. There is a growing demand for methodologies that explore cultural values at the individual level, revealing the diversity that country-level analyses may overlook. This study aims to analyze the foundations of Schwartz’s and Hofstede’s frameworks, highlighting their contributions and limitations while contextualizing the current study within the literature on individual-level approaches to cultural values. In order to accomplish this, the study employs LPA to identify subgroups defined by unique combinations of cultural and personality traits, synthesizing Schwartz’s value orientations and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. This approach allows for a deeper understanding of individual cultural profiles in the U.S., moving beyond national averages to examine the interaction of values and personality at the individual level (

Taras et al. 2010;

Yoo et al. 2011). It addresses the limitations of national aggregates in cross-cultural research and the person-situation debate in personality psychology, revealing systematic variability often overlooked by variable-centered approaches (

Fleeson 2004;

Fleeson and Noftle 2008;

Stewart and Barrick 2004).

This research advances the understanding of cultural value by shifting from a variable-centered to a person-centered approach, which uncovers latent subgroups of individuals sharing similar value configurations within a specific national context. This methodological transition is particularly relevant in light of global migration, transnational labor movements, demographic diversification, and the rapid spread of cultural content across borders, which have fundamentally altered the internal cultural dynamics of many nations (

Hofstede et al. 2010;

Schwartz 2006). Traditional models that assume cultural uniformity at the national level are increasingly insufficient because they ignore the complexities introduced by these global phenomena that challenge the idea of cultural homogeneity. By employing a person-centered methodology, this study acknowledges that cultural values are not uniformly accepted; rather, they exist in overlapping and sometimes conflicting clusters within national boundaries. This theoretical contribution challenges rigid notions of cultural identity and offers practical tools for understanding value pluralism and its implications for social cohesion, policy development, and intercultural dialog. The research highlights significant heterogeneity in cultural and personality configurations within a U.S. sample, elucidating variability and demonstrating how cultural values function as psychological dispositions that influence personal priorities and behaviors.

This nuanced perspective recognizes the pluralistic value landscape of the United States while aligning with the emphasis on individual differences in personality science. By focusing on individual-level variability within a multicultural population, the study diverges from most research that aggregates responses to the national level. This focus is critical because cultural values, akin to personality traits, serve as psychological orientations that guide behavior and social interaction, yet they may not be evenly distributed across a nation. Through the analysis of cultural value profiles at the individual level, the research moves beyond stereotypes of national character and highlights the heterogeneity that more accurately reflects the lived experiences of individuals in diverse societies like the United States. This approach contributes to personality science by emphasizing individual differences in cultural orientations, and it provides a methodological bridge between cultural psychology and the study of personality processes.

The study poses research questions rather than formal hypotheses, reflecting the intricate nature of cultural dynamics. These questions include: What individual cultural profiles emerge from Schwartz’s seven value orientations? What cultural profiles arise from Hofstede’s individual-level six value dimensions? And what patterns can be observed when cross-tabulating Schwartz and Hofstede’s profiles? By addressing these questions, the study seeks to provide a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of cultural values as they manifest in individual behaviors and preferences.

The subsequent sections are organized as follows: first, a review of the relevant literature will outline the theoretical foundations underpinning the study. This is followed by a detailed account of the participant sample and research methods. The empirical findings are then presented and analyzed. Finally, the discussion addresses the theoretical and practical implications of the study, considers directions for future research, and concludes with key insights.

4. Results

LPA was used to identify subgroups within the sample based on patterns across Schwartz and Hofstede frameworks. The optimal number of latent profiles was calculated using model fit indices, entropy values, and profile interpretability. The findings show that cultural variation within the U.S. is patterned by latent profiles, not adequately represented by national averages. All latent profile analyses were performed on non-ipsatized data to preserve absolute variance across individuals, ensuring that the resulting profiles reflect meaningful differences in overall value endorsement rather than relative intra-individual rankings.

Table 3 (Schwartz) encapsulate the comparative fit statistics for the latent profile models. Despite the continued decline of AIC and BIC with an increasing number of classes, the BLRT results endorsed the retention of these solutions up to k = 7 and k = 6, respectively, beyond which the enhancement in fit was not statistically significant. The entropy values for the chosen models demonstrated satisfactory classification accuracy, and the profiles in both solutions were theoretically consistent and substantively distinct. The combined evidence supported the retention of the seven-class Schwartz solution and the six-class Hofstede solution.

RQ 1: What cultural profiles emerge from Schwartz’s seven value orientations?

LPAs were conducted and analyzed to determine the optimal number of profiles. The findings of these analyses, performed for profile models ranging from 2 to 9, are presented in

Table 1, which outlines the fit criteria for each profile model. The determination of the optimal number of profiles was based on a comparative assessment of the fit criteria, as outlined in the table. Statistical metrics including Log Likelihood, AIC, BIC, and entropy indicated that model fit enhanced with a greater number of profiles, peaking at the seven-profile solution, beyond which the fit decreased (

Lawrence and Zyphur 2011). This indicates that the seven-profile solution is optimal for adequately representing the data. Schwartz’s seven-profile solution not only provided the optimal fit but also offered clear conceptual distinctions among clusters of motivational values.

The analysis revealed that both the AIC and BIC values decreased consistently across models, indicating a better fit with an increasing number of profiles. High entropy values (0.82 to 0.92) confirmed strong classification accuracy, surpassing the acceptable threshold of 0.80 for distinguishing profiles. The BLRT showed significant results (

p = 0.010) for models with up to six profiles but was not significant for the seven-profile model (

p = 0.455), suggesting no substantial improvement in fit with the additional profile. Despite this, the seven-profile solution was chosen as the final model based on a comprehensive evaluation of statistical fit, entropy, interpretability, and theoretical coherence. The AIC (10.036.37) and BIC (10.308.47) reached their lowest values at this solution before stabilizing. The seventh profile added a unique and interpretable subgroup, enhancing the model’s conceptual framework without introducing minor or unstable profiles. This supports the recommendation of prioritizing parsimonious models that are theoretically interpretable over those with slightly superior fit but unstable higher-order solutions (

Nylund et al. 2007;

Morin et al. 2016). Model selection was informed by statistical metrics and interpretability standards, following established protocols (

Nylund et al. 2007;

Masyn 2013;

Morin et al. 2016).

The study identified seven distinct value orientation profiles based on participants’ responses across seven dimensions: Mastery, Affective Autonomy, Intellectual Autonomy, Egalitarianism, Harmony, Embeddedness, and Hierarchy, aligning with Schwartz’s universal human values (

Schwartz 1992). The profiles were categorized into three thematic groups: those supportive or indifferent to hierarchy (Profiles 3, 4, 5, and 7), those rejecting hierarchy (Profiles 1 and 2), and an apathetic profile (Profile 6). The identified profiles highlight the varying ways through which individuals give precedence to these values, suggesting a complex interplay between personal values and cultural context and revealing insights into how value priorities differ among individuals across cultures. Profiles supporting or indifferent to hierarchy exhibited varying degrees of endorsement for structured social roles. Profile 7 (n = 200; 33.6%) the predominant profile demonstrated uniformly elevated scores across all dimensions, including Hierarchy (M = 5.741), Egalitarianism (M = 6.116), and Intellectual Autonomy (M = 5.926). This pattern reflects a value orientation that harmonizes individual liberties with social order, aligning with a modern institutionalist perspective that advocates for autonomy within an organized society (). Profile 5 (n = 120; 20.2%) exhibited moderate scores across dimensions, with marginally lower endorsement of Affective Autonomy (M = 3.953) and Hierarchy (M = 4.814). These individuals may exhibit a moderately conforming orientation, appreciating structure and independence without a strong affiliation to either extreme (

Bilsky et al. 2011). Profile 4 (n = 88; 14.8%) exhibited comparatively low scores across all values, including Hierarchy (M = 3.874) and Mastery (M = 4.169). This indicates a low-value differentiation profile, potentially signifying value ambivalence, or normative conformity without robust internalization of either autonomy or tradition-based values (

Boer and Fischer 2013;

Spini and Doise 1998). Profile 3 (n = 59; 9.9%) achieved elevated scores in all dimensions, specifically Hierarchy (M = 6.409), Embeddedness (M = 6.571), and Intellectual Autonomy (M = 6.640). This profile seems to embody cultural integration with individuals who harmonize authority and personal freedom (

Roccas et al. 2002).

In contrast, Profiles 1 (n = 37; 6.2%) and 2 (n = 44; 7.4%) exhibited resistance to hierarchy, albeit with divergent motivational frameworks and value priorities. Profile 1 (n = 37; 6.2%) exhibited minimal endorsement of Hierarchy (M = 2.501) alongside elevated scores in Intellectual Autonomy (M = 6.339) and Embeddedness (M = 6.374). These individuals seem to prioritize self-direction in conjunction with robust social connections, reflecting the communitarian values observed in democratic egalitarian societies (

Inglehart and Welzel 2005). Profile 2 (n = 44; 7.4%) similarly rejected hierarchy (M = 1.883) but significantly differed from Profile 1 due to their low endorsement of Mastery (M = 3.160), Affective Autonomy (M = 2.963), and additional values. This profile may reflect a disengaged or alienated orientation, consistent with low civic engagement and a critical stance toward dominant cultural frameworks (

Schwartz 2006). Profile 6 (n = 47; 7.9%) exhibited persistently low mean scores across all dimensions, specifically Mastery (M = 2.858), Hierarchy (M = 2.778), and Intellectual Autonomy (M = 3.055). This profile indicates a weak identification with any value orientation and may signify value apathy, a condition linked to low motivation, detachment, or even anomie (

Srole 1956). This profile is significant in discussions regarding marginalization or cultural disorientation in transitional societies. Essentially, these findings stress the multifaceted character of value systems and their correspondence with social orientation. Some profiles (e.g., Profile 7) illustrate the coexistence of autonomy and hierarchy, while others (e.g., Profiles 1 and 2) exhibit differing levels of resistance to authority. The generalized disengagement of Profile 6 highlights the necessity of recognizing value apathy as a unique sociopsychological phenomenon. The findings substantiate theories of value pluralism (

Rohan 2000;

Hitlin and Piliavin 2004) and cultural hybridity (

Berry 1997), indicating that individuals do not conform to a singular axis of individualism or collectivism but rather develop intricate, context-dependent value identities shaped by structural, cultural, and experiential influences. The findings reveal that a significant majority of participants support hierarchy to differing extents, while a smaller segment opposes hierarchy, favoring egalitarian and autonomy principles. Additionally, there exists a minor group exhibiting low-intensity endorsements across the various value domains.

Table 4 reports the means and standard errors of each indicator variable for every latent profile, together with profile sizes and proportions. These values represent the response means and their standard errors, used to interpret the substantive meaning of each profile.

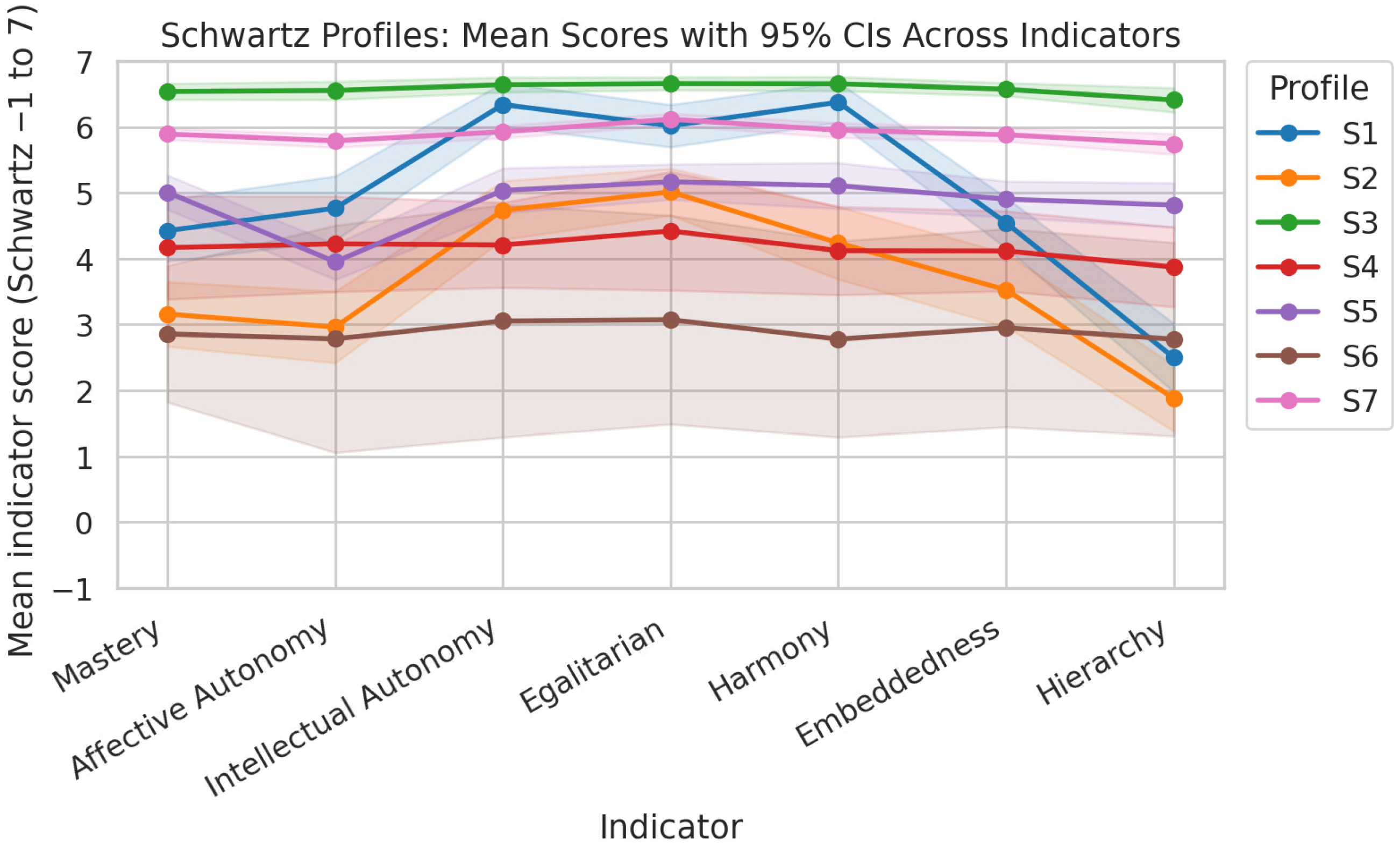

The analysis of Schwartz value profiles, as depicted in

Figure 1, reveals distinct patterns of value endorsement among the seven identified profiles (S1–S7) across various higher-order value indicators, including Mastery, Affective Autonomy, Intellectual Autonomy, Egalitarian, Harmony, Embeddedness, and Hierarchy. Each profile’s mean scores are represented with 95% confidence intervals, which not only provide a visual representation of the data but also enhance the transparency and reproducibility of the findings (

Masyn 2013;

Morin et al. 2016).

The profiles can be categorized based on their attitudes towards hierarchy. Profiles S1 and S2 are characterized as “profiles disliking hierarchy,” as they exhibit low scores on Hierarchy and Embeddedness while showing higher scores on Egalitarian; Harmony; and Autonomy indicators. This configuration suggests a strong preference for equality and personal freedom; with their confidence intervals indicating a clear divergence from more hierarchical profiles (S3; S4; S5; S7). In contrast; the “profiles neutral/favoring hierarchy” profiles (S3; S4; S5; and S7) display higher scores on Hierarchy and Embeddedness; often coupled with elevated Mastery scores; while their scores on Egalitarian and Autonomy are comparatively lower. This indicates a greater acceptance of traditional power structures and role obligations; distinguishing them from the egalitarian leanings of S1 and S2. Profile S6 stands out as an “apathetic profile,” characterized by relatively flat scores across the value indicators; clustering around the midpoint. The overlapping confidence intervals with other profiles suggest a lack of strong endorsement or rejection of any specific value dimension; indicating a less differentiated value structure. The findings as presented in

Figure 1 indicate that Schwartz values are organized into coherent constellations rather than existing as isolated dimensions.

RQ 2: What cultural profiles emerge from Hofstede’s individual-level six value dimensions?

The study utilized LPA based on

Hofstede’s (

2011) framework to investigate cultural profile differences related to individual variations in cultural dimensions. The analysis considered up to a nine-profile solution, with fit indices such as Log Likelihood, AIC, BIC, and entropy demonstrating improved model fit up to the sixth-profile solution, after which fit declined. Thus, the six-profile solution was identified as optimal for data representation (

Lawrence and Zyphur 2011). Fit statistics presented in

Table 3 indicated that AIC and BIC values decreased consistently with the addition of profiles, a common outcome in mixture modeling due to increased complexity. The final profile count was determined by balancing fit improvement and parsimony, with the six-profile solution offering a favorable balance of statistical fit (BIC = 8133.771, entropy = 0.846306) and interpretability. Higher-profile solutions resulted in redundant subgroups, supporting the preference for parsimonious models (

Nylund et al. 2007;

Morin et al. 2016).

Model selection conformed to optimal methodologies, integrating statistical fit indices with substantive interpretability (

Masyn 2013;

Morin et al. 2016;

Nylund et al. 2007). Across solutions, fit indices typically enhanced with the inclusion of additional profiles, while entropy values ranging from 0.76 to 0.85 signified satisfactory classification accuracy. The Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) was significant for the two- to five-profile solutions, demonstrating that models with up to five profiles exhibited a significantly superior fit compared to the models with one fewer profile. The BLRT comparing the six-profile solution to the five-profile solution was not significant, indicating no evident statistical benefit in incorporating a sixth profile. Despite the BLRT for the seven-profile model being significant, AIC and BIC values began to stabilize, and higher-order solutions yielded smaller, less stable classes with diminished entropy and restricted substantive interpretability. Given the declining enhancements in AIC/BIC, satisfactory entropy, the nonsignificant BLRT at six profiles, and the theoretical consistency of the profile structure, the six-profile solution was maintained as the most parsimonious and substantively meaningful representation of Hofstede’s cultural value data. The alignment of statistical and theoretical criteria endorses the six-profile model as the optimal solution.

Table 5 (Hofstede) encapsulate the comparative fit statistics for the latent profile models

The analysis identified six distinct cultural orientation profiles based on participant responses across six dimensions of

Hofstede’s (

2001) national culture framework: Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, Individualism-Collectivism, Masculinity-Femininity, Time Orientation, and Indulgence-Restraint. These profiles offer a person-centered viewpoint on how individuals organize cultural values, highlighting intra-cultural diversity and surpassing simplistic national aggregates (

Taras et al. 2009;

Fischer and Schwartz 2011). The total sample comprised 595 participants, unevenly allocated across profiles, with the largest cluster accounting for 27.6% and the smallest for 10.3% of the sample. Profiles were categorized into three principal orientations based on Power Distance: those neutral or favorable towards hierarchy (Profiles 3 and 6), (2), those opposed to power distance (Profiles 1, 2, and 5), and an apathetic profile (Profile 4) characterized by minimal endorsement across most dimensions (see

Table 6).

Profiles Favorable or Neutral Toward Power Distance. Profile 6 (n = 94; 15.8%) exhibited the highest Power Distance score (M = 4.016, SE = 0.072), indicating a strong endorsement of hierarchical relationships and authority. This group demonstrated high scores in Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 4.477) and Time Orientation (M = 4.397), reflecting a preference for predictability, long-term planning, and structured institutions. These patterns correspond with cultures that emphasize hierarchical status, social regulation, and continuity (

House and Javidan 2004;

Schwartz 2006). Profile 3 (n = 164; 27.6%), the largest subgroup, demonstrated moderate acceptance of Power Distance (M = 3.199), reflecting a flexible disposition toward authority. The scores for Masculinity-Femininity (M = 3.562) and Indulgence-Restraint (M = 3.429) were moderate, while Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 3.828) and Time Orientation (M = 3.785) were relatively high. This profile may denote conformist pragmatists; individuals who prioritize stability while acquiescing to moderate authority (

Hofstede 2001).

Profiles Disliking Power Distance. Profiles 1, 2, and 5 demonstrated low Power Distance scores (M = 1.811 to 1.973), signifying egalitarian inclinations and resistance to rigid authority hierarchies. However, their configurations differed across various dimensions, reflecting unique motivational frameworks and cultural priorities. Profile 2 (n = 111; 18.7%) demonstrated the lowest Power Distance (M = 1.811), alongside relatively high Collectivism (M = 3.891), and reduced Masculinity (M = 1.578). Participants demonstrated high scores in Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 4.441) and Time Orientation (M = 4.386). This group likely embodies cooperative, security-oriented egalitarians, associated with feminine collectivist cultures that emphasize caregiving, harmony, and group loyalty over competition (

Bilsky et al. 2011;

Hofstede 2001). Profile 1 (n = 92; 15.5%) similarly rejected Power Distance (hierarchical authority) (M = 1.925) while supporting reduced Individualism (M = 2.113) and moderate Masculinity (M = 2.090). The amalgamation signifies anti-authoritarian communitarians who emphasize group cohesion and humility while promoting egalitarian social structures characteristics commonly found in participatory or democratic collectivist settings (

Inglehart and Welzel 2005). Profile 5 (n = 73; 12.3%) demonstrated low Power Distance (M = 1.973), higher Individualism (M = 4.185), and high Masculinity (M = 3.971). This pattern suggests that individuals are achievement-oriented and prioritize autonomy, favoring independence and personal success over hierarchical frameworks. This group may align with liberal individualists who prioritize performance and control over outcomes while resisting centralized authority (

Triandis 1995).

Apathetic Profile. Profile 4 (n = 61; 10.3%) demonstrated consistently low scores across all dimensions, namely Power Distance (M = 2.515), Individualism (M = 2.822), and Masculinity (M = 2.666). Uncertainty Avoidance (M = 3.005) and Time Orientation (M = 3.147) exhibited moderate levels. This profile may suggest value apathy or disengagement, marked by individuals exhibiting minimal adherence to established social norms or guiding value systems. These profiles have been linked to anomic conditions, social marginalization, or ambivalence towards cultural norms (

Srole 1956;

Rohan 2000).

Essentially, these findings support the concept that cultural values operate at an individual level with multidimensional variability, rather than solely as national averages. Rather than adhering to simplistic dichotomies (e.g., collectivism versus individualism), individuals often integrate diverse cultural values in complex and occasionally contradictory ways (

Vignoles et al. 2016). The presence of an apathetic profile highlights the need to examine value disengagement as an independent social and psychological phenomenon. Such configurations may signify alienation, uncertainty, or cultural fragmentation, especially in transitional or multicultural contexts (

Berry 1997;

Schwartz 2006). The results underscore the efficacy of person-centered approaches in cultural psychology and sociology, offering a more profound comprehension of the diversity of cultural orientations among populations. Please see

Table 6 for the profiles.

Figure 2 illustrates these profiles through

mean scores with 95% confidence intervals,

providing a visual representation

of the

convergence and divergence among the different

cultural dimensions. The shaded bands around each line in the figure indicate the uncertainty of the estimated means, enhancing the

transparency and reproducibility of the findings (

Masyn 2013;

Morin et al. 2016).

The empirical categorization of profiles is segmented into three primary classifications: profiles that oppose Power Distance, profiles that are neutral or supportive of Power Distance, and an indifferent profile. Profiles 1, 2, and 5 exhibit a “dislike for Power Distance,” with mean scores ranging from 1.8 to 2.0, markedly below the scale’s midpoint. The confidence intervals for these profiles do not intersect with those of the higher Power Distance profiles, indicating a definitive rejection of pronounced hierarchies and significant status disparities. These profiles demonstrate elevated levels of Uncertainty Avoidance and Long-Term Orientation, indicating a preference for explicit regulations, predictability, and future-oriented planning. Conversely, Profiles 3 and 6 are classified as “neutral/favoring Power Distance.” The profiles exhibit mean scores at or above the midpoint for Power Distance, with confidence intervals clearly distinct from those of the disliking profiles. Individuals in these profiles typically endorse hierarchical relationships, often integrating this acceptance with a performance-driven and systematic approach. Furthermore, they exhibit heightened levels of Uncertainty Avoidance and Time Orientation, as well as increased scores in Individualism and Masculinity in certain instances. Finally, Profile 4 is designated as the “apathetic profile,” characterized by moderate and relatively uniform scores across the different dimensions.

Values are not isolated constructs; they constitute coherent constellations that mirror broader cultural profiles. This concept is corroborated by the data depicted in

Figure 2, which demonstrates the clustering of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions into discrete value profiles, with Power Distance serving as the primary dimension that differentiates groups, while Uncertainty Avoidance and Time Orientation are typically elevated across profiles.

RQ 3: What patterns emerge when crosstab Schwartz and Hofstede’s profiles?

The analysis of cultural profiles based on Hofstede’s and Schwartz’s frameworks reveals intricate relationships between individual preferences for power distance and hierarchical structures. The study identified six distinct profiles for Hofstede (labeled H1 to H6) and seven for Schwartz (labeled S1 to S7), and a cross-tabulation of these profiles was conducted to explore the distribution of participants among them. The results, as illustrated in

Table 7, highlight significant patterns in how individuals align with these profiles, indicating both congruence and divergence in cultural values.

Profiles H1 and H2, characterized by a rejection of power distance, show a relatively even distribution between Schwartz profiles S1, which also rejects hierarchy, and S7, which supports it, albeit with a slight preference for S7. Conversely, profiles H3 and H5, which endorse hierarchy, along with H6, the apathetic profile, exhibit notable clustering. Specifically, H3 is predominantly found in Schwartz profiles S4, S5, and S7, all of which favor hierarchical structures. H5, which opposes power distance, is almost exclusively associated with S7, while H6, which supports power distance, is primarily located within profiles S3, S5, and S7. The apathetic profile H4 is more evenly distributed but shows a significant presence in S6, its corresponding apathetic profile in Schwartz’s framework. This distribution suggests a partial alignment between the two sets of profiles, with certain Hofstede profiles closely mirroring specific Schwartz profiles, while others display a more hybrid relationship.

The analysis further identifies three principal themes concerning Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in relation to Schwartz’s value profiles. Profiles H3 and H6 demonstrate a positive inclination towards power distance, aligning with Schwartz profiles S3, S4, S5, and S7, which advocate for authority and social hierarchies. The findings indicate both concordance and discordance among the profiles, particularly highlighting the correlation between H6 and Schwartz profiles S3 and S4, suggesting shared behavioral traits. In contrast, profiles H1, H2, and H5, which exhibit low power distance preferences, align with Schwartz profiles S1 and S2, indicating a shared aversion to hierarchy and a preference for equality and decentralized authority. The neutral stance of H4 on power distance corresponds with Schwartz profile S6, indicating a lack of strong cultural coherence or guiding principles.

When considered collectively, the visual representations of Schwartz and Hofstede converge on a shared underlying structure. First, Schwartz profiles that reject hierarchy (S1, S2) align conceptually with Hofstede profiles that also reject power distance (H1, H2, H5). Both frameworks reflect a rejection of hierarchical relations while simultaneously valuing order and structure, as evidenced by related Schwartz dimensions and Hofstede’s high Uncertainty Avoidance and Time Orientation. Second, Schwartz profiles that are neutral or favor hierarchy (S3, S4, S5, S7) correspond to Hofstede profiles that are neutral or favor These groups: Accept or favor hierarchical distinctions (higher Schwartz hierarchy/embeddedness; higher Hofstede Power Distance). Combine hierarchy with strong appreciation for norms, planning, and sometimes performance (elevated mastery in Schwartz; elevated Uncertainty Avoidance, Time Orientation, and sometimes Masculinity and Individualism in Hofstede). Third, the Schwartz apathetic profile (S6) parallels the Hofstede apathetic profile (Profile 4), with both visuals depicting: Midrange, relatively flat scores across value dimensions. A less crystallized or lower-salience value configuration. The aligned results show that hierarchy vs. equality is the primary organizing dimension in both frameworks, while preferences for structure, predictability, and long-term orientation are relatively widespread, cutting across both hierarchy-accepting and hierarchy-rejecting groups.

The analysis of cultural dimensions through Hofstede’s and Schwartz’s profiles reveals intricate patterns of alignment and divergence among various participant profiles. The study identifies six distinct Hofstede profiles (H1 to H6) and seven Schwartz profiles (S1 to S7) and employs cross-tabulation to explore the distribution of individuals across these profiles. The findings, as presented in

Table 5, illustrate significant trends in how these profiles interact, particularly in relation to power distance and hierarchy. Profiles H1 and H2, characterized by a general aversion to power distance, show a relatively balanced distribution between Schwartz profiles S1, which rejects hierarchy, and S7, which supports it. This distribution indicates a nuanced relationship where individuals with low power distance preferences do not strictly conform to a single hierarchical stance. Conversely, profiles H3 and H5, which endorse hierarchy, alongside H6, the apathetic profile, exhibit a more pronounced clustering. Specifically, H3, which supports power distance, is predominantly associated with Schwartz profiles S4, S5, and S7, all of which favor hierarchical structures. H5, despite opposing power distance, is almost exclusively found in S7, suggesting a complex interplay between personal values and hierarchical acceptance. Meanwhile, H6, which also favors power distance, is primarily linked to profiles S3, S5, and S7, reinforcing the notion that individuals who endorse power distance tend to align with hierarchical values. The apathetic profile H4 presents a more varied distribution, though it is notably prevalent in S6, its corresponding apathetic Schwartz profile. This suggests that H4 may represent a distinct subgroup that lacks strong cultural coherence or guiding principles. The analysis further identifies three principal themes regarding Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in relation to Schwartz’s value profiles. Notably, profiles H3 and H6 demonstrate a positive inclination towards power distance, aligning with Schwartz profiles S3, S4, S5, and S7, which advocate for authority and social hierarchies. The findings reveal both concordance and discordance among the profiles, highlighting significant correlations between profile H6, which endorses power distance, and profiles S3 and S4, which advocate hierarchy, suggesting related behavioral traits. The apathetic profile H4 displays a varied distribution, indicating it may represent a distinct subgroup. Profiles H1, H2, and H5 display low power distance preferences, aligning with Schwartz profiles S1 and S2, indicating a dislike for hierarchy and a heightened inclination towards equality and decentralized authority. Ultimately, the neutral stance of H4 on power distance corresponds with Schwartz profile S6, the apathetic profile, signifying a deficiency in strong cultural coherence or guiding principles.

A chi-square test of independence indicated a significant association between Hofstede profiles and Schwartz profiles, χ

2(30, N = 595) = 354.17,

p < 0.001 (exact

p = 4.60 × 10

−57). The effect size was moderate, Cramer’s V = 0.345. Standardized residuals with significance stars highlighted specific profile pairings that were over- or under-represented relative to independence; see

Figure 1 for a residual heatmap annotated with significance. A parallel analysis using broader bands (Neutral/Favoring Power Distance vs. Disliking Power Distance vs. Apathetic crossed with Favoring Hierarchy vs. Disliking Hierarchy vs. Apathetic) also showed a significant association, χ

2(4, N = 595) = 63.82,

p < 0.001 (exact

p = 4.57 × 10

−13), with a small-to-moderate effect, Cramer’s V = 0.232. Significance-annotated standardized residuals are shown in

Figure 2, which clarifies which band pairings drive the overall relationship. The findings suggest that the structural relationships observed across profiles are unlikely to be mere statistical artifacts. The consistency of measurement across both frameworks enhances the interpretation of over- and under-represented dimensions as significant indicators of cross-theoretical alignment. To contextualize the variations in measurement quality, we observe that reliability for the dimensions remains consistently robust. For Schwartz, α varied from 0.780 to 0.922 and ωt from 0.782 to 0.924 (e.g., Embeddedness α = 0.922, 95% CI [0.909, 0.932], ωt = 0.924; Egalitarianism α = 0.865, [0.842, 0.886], ωt = 0.869; Hierarchy α = 0.783, [0.753, 0.806], ωt = 0.795). As to Hofstede’s dimensions, α values ranged from 0.773 to 0.913 and ωt values from 0.781 to 0.914 (e.g., Power Distance α = 0.862, [0.838, 0.880], ωt = 0.862; Individualism-Collectivism α = 0.904, [0.887, 0.918], ωt = 0.904; Indulgence-Restraint α = 0.913, [0.900, 0.924], ωt = 0.914). The internal consistency coefficients provide evidence for the reliability of the composite indicators across profiles, supporting the interpretive validity of observed patterns of over- and under-representation between Schwartz and Hofstede dimensions. For example, S7 was most closely associated with H5 and H6, while S3 aligned with H6, S4–S5 with H3, S1–S2 with H2, and S6 with H4. These consistent associations reinforce confidence in the stability and distinctiveness of the identified latent profiles, signifying meaningful cross-framework alignment rather than mere measurement noise.

The psychometric anchors demonstrate that the observed profile-level associations indicate theoretical alignment rather than measurement error. The hierarchy-oriented profile S7 is associated with Hofstede’s H5 and H6 dimensions. Both related value constructs are accurately assessed: Schwartz’s Hierarchy (α = 0.783; ωt = 0.795) and Hofstede’s Power Distance (α = 0.862; ωt = 0.862). Profile S3, consistent with H6 and distinct from H3, was predominantly linked to Schwartz’s Mastery (α = 0.850; ωt = 0.856) and Embeddedness (α = 0.922; ωt = 0.924), which was further corroborated by the stable Hofstede hierarchy measure. Conversely, profiles S4 and S5 exhibited a closer alignment with H3 than with H6, a distinction corroborated by robust autonomy and egalitarianism composites from Schwartz—Intellectual Autonomy (α = 0.780; ωt = 0.782), Affective Autonomy (α = 0.802; ωt = 0.808), and Egalitarianism (α = 0.865; ωt = 0.869)—as well as Hofstede dimensions that differentiate H3, including Individualism vs. Collectivism (α = 0.904; ωt = 0.904) and Masculinity vs. Femininity (α = 0.893; ωt = 0.894). Profiles that are less aligned with hierarchy, such as S1 and S2, exhibited a consistent overrepresentation of H2 and a tendency to avoid the S7-H5/H6 cluster. The profiles were characterized by values including Egalitarianism, Affective Autonomy, and Intellectual Autonomy, all assessed with high reliability, in conjunction with Hofstede’s dimensions of Individualism versus Collectivism and Uncertainty Avoidance (α = 0.845; ωt = 0.848). The disengaged or indifferent profile S6 was correlated with H4 and contrasted with H6, grounded in Schwartz’s Harmony (α = 0.832; ωt = 0.835) and Egalitarianism (α = 0.865; ωt = 0.869), and was evidenced by consistent Hofstede metrics along the H4/H6 axis, notably Power Distance. All Hofstede constructs in this comparison exhibited reliability coefficients of α ≥ 0.773 and ωt ≥ 0.781. Collectively, these findings suggest that the structural relationships observed across profiles are improbable to be mere statistical artifacts. The uniformity of measurement across both frameworks enhances the understanding of over- and under-represented dimensions as significant indicators of cross-theoretical alignment.