Survival to Dignity? The Precarious Livelihood of Street Food Vendors in South Mumbai and Their Path Toward Decent Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

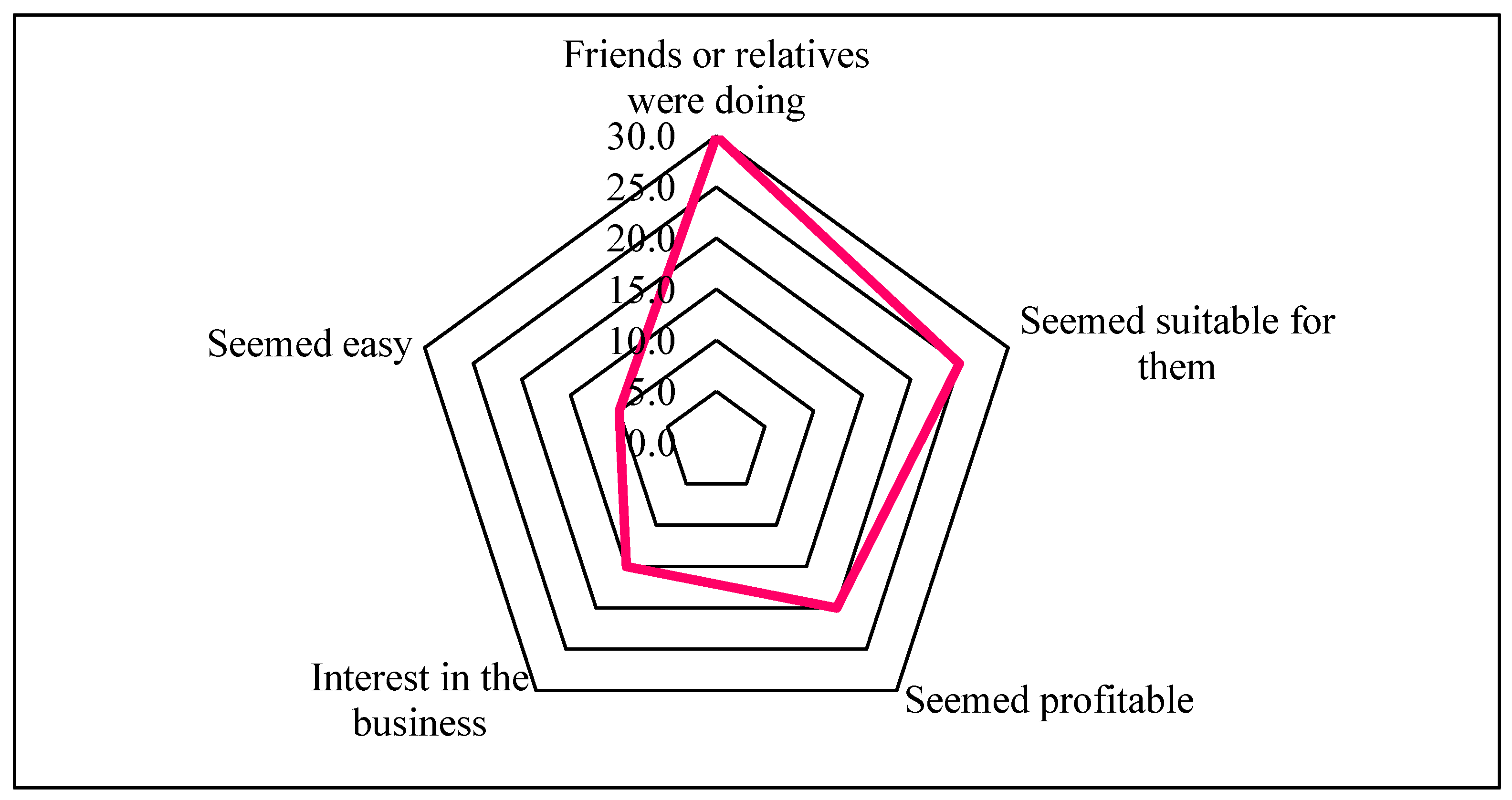

- What is the motivation behind street food vending?

- ii.

- What is the duration of their business, initial investment, daily expenditure, and daily earnings?

- iii.

- Do the duration of engagement, initial investment, daily number of customers, and average daily earnings have a significant association with street vendors’ daily expenditure?

- iv.

- What are the challenges faced by these vendors in their livelihood? Are they required to make miscellaneous payments and take credit from loan sharks?

- v.

- What strategies can expand their precarious livelihood strategies into more stable, dignified forms of decent work?

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Precarious Work in the Informal Sector

2.2. ILO’s Decent Work Agenda

2.3. Urban Informality, Governance, and Dignity of Work

2.4. Street Food Vending as an Urban Informal Activity

3. Research Design

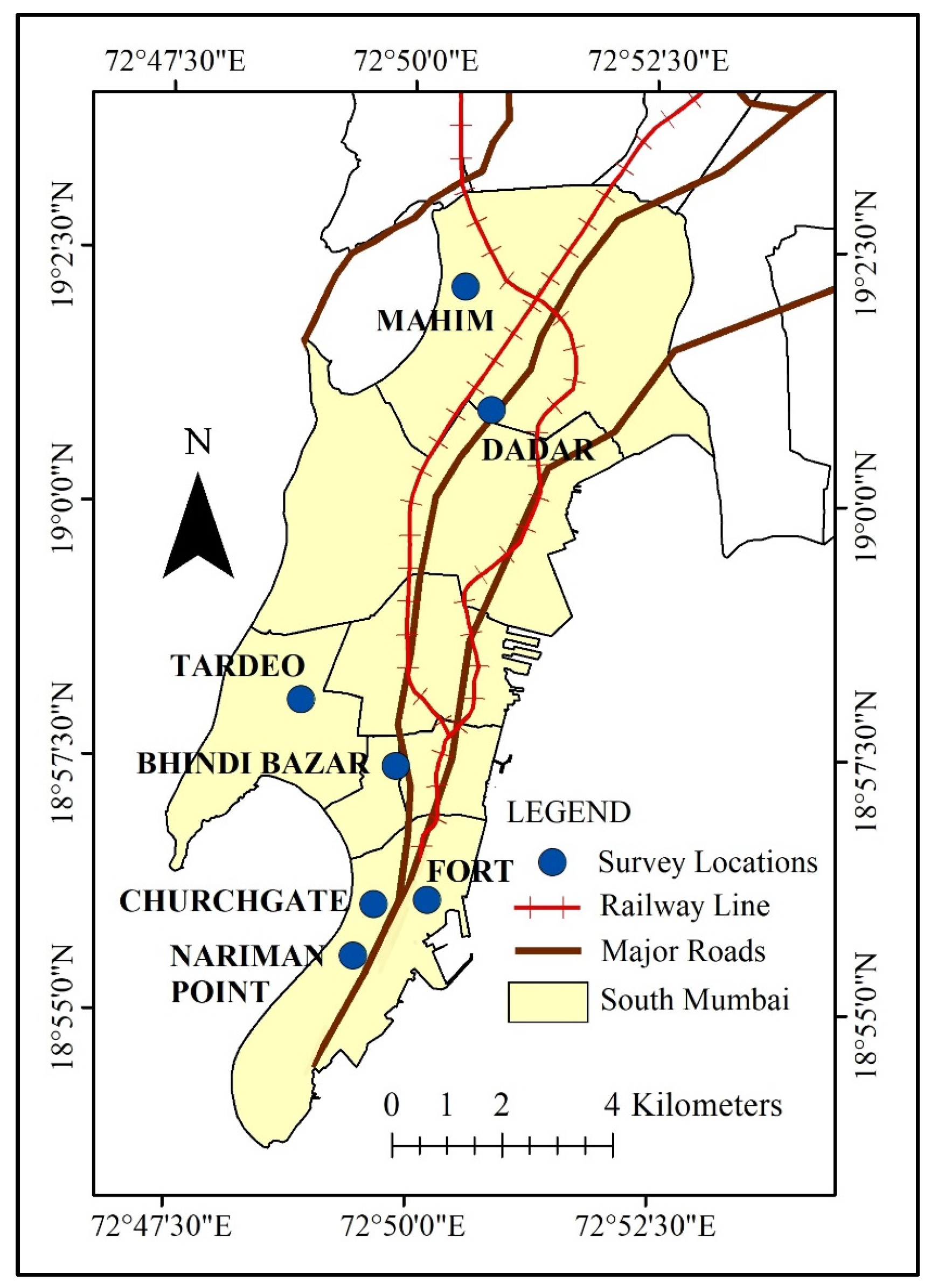

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Sampling Strategy and Justification

3.3. Methods of Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Profile of Vendors

4.2. Economic Dimensions of Precarity

4.3. Struggles, Vulnerabilities, Coping Strategies, and Resilience

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions, Policy Recommendation, and Future Research Direction

- (i)

- More effective implementation of the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014, is necessary, such as streamlining the licensing process and establishing the transparent allocation of vending zones to lessen harassment, extortion, and risk of eviction.

- (ii)

- City planners should develop inclusive vending zones with access to water, sanitation, waste disposal, and shelter if appropriate, to enhance their working environment. Introducing structured training programs could enhance vendors’ business capacities, improve food hygiene standards, and help build consumer trust, thereby making livelihoods more sustainable.

- (iii)

- Promoting the growth of local unions or cooperatives could allow vendors to collectively bargain, negotiate better with councils, and influence stronger enforcement of their entitlements.

- (iv)

- Connecting South Mumbai vendors with national federations could amplify their voices in policy processes and help solidify solidarity across urban spaces.

- (v)

- Developing a partnership with residential associations and NGOs could help to minimize conflict in public spaces and support vending as part of Mumbai’s urban fabric.

- (vi)

- Expanding affordable credit options through public finance and microfinancing options may help vendors to escape the hold of loan sharks, where much of their capital can be in the form of loan repayment, which can lead to over-indebtedness.

- (vii)

- Access to affordable health insurance, accident insurance, and pension schemes could support vendors against shocks that typically plunge vendors into even further precarity.

- (viii)

- Gender-sensitive items such as maternity leave, safe public spaces, and preferential financing would meaningfully strengthen the livelihoods of women vendors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adama, Onyanta. 2021. Criminalizing Informal Workers: The Case of Street Vendors in Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies 56: 533–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahoobim, Oren, Laura Goldman, and Shanti Mahajan. 2024. What Makes a ‘World-Class’ City? Stanford Social Innovation Review. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/what_makes_a_world_class_city (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Alimi, Buliyaminu Adegbemiro. 2016. Risk Factors in Street Food Practices in Developing Countries: A Review. Food Science and Human Wellness 5: 141–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, Bhuvana, Prashant Narang, Ritika Shah, and Vidushi Sabharwal. 2019. The Ease of Doing Business on the Streets of India. Association for Asian Studies. Available online: https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-ease-of-doing-business-on-the-streets-of-india/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Ashaley-Nikoi, Juliana, and Emmanuel Abbey. 2023. Determinants of the Level of Informality amongst Female Street Food Vendors in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Two Regions in Ghana. Cities 138: 104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Nicola, Melanie Lombard, and Diana Mitlin. 2020. Urban Informality as a Site of Critical Analysis. The Journal of Development Studies 56: 223–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthwal, Vaishnavi, Suresh Jain, Ayushi Babuta, Chubamenla Jamir, Arun Kumar Sharma, and Anant Mohan. 2022. Health Impact Assessment of Delhi’s Outdoor Workers Exposed to Air Pollution and Extreme Weather Events: An Integrated Epidemiology Approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 29: 44746–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrou, Jean-Philippe, and Claire Gondard-Delcroix. 2018. Dynamics of Social Networks of Urban Informal Entrepreneurs in an African Economy. Review of Social Economy 76: 167–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, Sujayita, and Madhuri Sharma. 2023. Polycentric Urbanism and the Growth of New Economic Hubs in Mumbai, India. In Urban Commons, Future Smart Cities and Sustainability. Edited by Uday Chatterjee, Nairwita Bandyopadhyay, Martiwi Diah Setiawati and Soma Sarkar. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, Jayanta, and Sarthak Aryan. 2020. Right to Livelihood for the Street Food Vendors in India. Indian Journal of Socio-Legal Analysis 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Marty. 2016. The Urban Informal Economy: Towards More Inclusive Cities. Urbanet. August 16. Available online: https://www.urbanet.info/urban-informal-economy/ (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Chowdhury, Mushtaque Raza, Ferdous Jahan, and Rehnuma Rahman. 2017. Developing Urban Space: The Changing Role of NGOs in Bangladesh. Development in Practice 27: 260–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, William Gemmell. 1977. Sampling Techniques. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dhingra, Swati. 2020. Protecting Informal Workers in Urban India: The Need for a Universal Job Guarantee. CEPR, May 2. Available online: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/protecting-informal-workers-urban-india-need-universal-job-guarantee (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Divya, A. 2020. Explained: Who Is a ‘Street Vendor’ in India? What Is the Street Vendors Act?|Explained News, The Indian Express. The Indian Express. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/street-vendor-act-pm-svanidhi-scheme-explained-6911120/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- European Union. 2024. Overview of Approaches to the Informal Economy. Capacity4dev. Available online: https://capacity4dev.europa.eu/groups/rnsf-mit/info/41-overview-approaches-informal-economy_en (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Florence, Bonnet, Joann Vanek, and Martha Alter Chen. 2019. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Brief|WIEGO and ILO. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/publications/women-and-men-informal-economy-statistical-brief (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Gautam, Ajay., and B. S. Waghmare. 2021. The Plight of Street Vendors in India. Economic and Political Weekly 56: 45–46. Available online: https://www.epw.in/journal/2021/45-46/special-articles/plight-street-vendors-india.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Grant, Richard, and Jan Nijman. 2002. Globalization and the Corporate Geography of Cities in the Less-Developed World. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 92: 320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarjärvi, Tuure, and Sari Laari-Salmela. 2022. Examining the Role of Dignity in the Experience of Meaningfulness: A Process-Relational View on Meaningful Work. Humanistic Management Journal 7: 417–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. 2002. From Precarious Work to Decent Work. Geneva: International Labour Organization. ISBN 978-92-2-126224-4. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2018. More than 60 per Cent of the World’s Employed Population Are in the Informal Economy. Press Release, April 30. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_627189/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Israel, Glenn. D. 1992. Determining Sample Size. Gainesville: University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, EDIS. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, Mueena, Morshedur Rahman, Mostafizur Rahman, Tajuddin Sikder, Rachael A. Uson-Lopez, Abu Sadeque Md Selim, Takeshi Saito, and Masaaki Kurasaki. 2018. Microbiological Safety of Street-Vended Foods in Bangladesh. Journal of Consumer Protection and Food Safety 13: 257–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambara, Channamma, and Indrajit Bairagya. 2021. Earnings and Investment Differentials Between Migrants and Natives: A Study of Female Street Vendors in Bengaluru City. Environment and Urbanization ASIA 12: 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwol, Victoria Stephen, Kayode Kolawole Eluwole, Turgay Avci, and Taiwo Temitope Lasisi. 2020. Another Look into the Knowledge Attitude Practice (KAP) Model for Food Control: An Investigation of the Mediating Role of Food Handlers’ Attitudes. Food Control 110: 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Byoung-Hoon, Sarah Swider, and Chris Tilly. 2020. Informality in Action: A Relational Look at Informal Work. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 61: 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahopo, Tjale Cloupas, Cebisa Noxolo Nesamvuni, Azwihangwisi Edward Nesamvuni, Melanie de Bryun, Johan van Niekerk, and Ramya Ambikapathi. 2022. Operational Characteristics of Women Street Food Vendors in Rural South Africa. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 849059. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.849059 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Malasan, Prananda Luffiansyah. 2019. The Untold Flavour of Street Food: Social Infrastructure as a Means of Everyday Politics for Street Vendors in Bandung, Indonesia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 60: 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, Manfredo. 2019. Urban Commons and the Right to the City. The Journal of Public Space 4: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matkailu, Samk. 2023. Street food is an element of cultural identity. Matkailun Blogi, February 14. Available online: https://matkailu.samk.fi/street-food/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- McKay, Fiona H., and Richard H. Osborne. 2022. Exploring the Daily Lives of Women Street Vendors in India. Development in Practice 32: 460–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, Arup. 2006. Labour Market Mobility of Low Income Households. Economic and Political Weekly 41: 2123–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, Arup. 2008. Social Capital, Livelihood and Upward Mobility. Habitat International 32: 261–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASVI. 2012. Defining Street Vendors. National Association of Street Vendors of India—NASVI. October 22. Available online: https://nasvinet.org/defining-street-vendors/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- NCEUS. 2009. The Challenge of Employment in India—An Informal Economy Perspective. National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector. Available online: https://dcmsme.gov.in/The_Challenge_of_employment_in_India.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Nicula, Virgil, Donatella Privitera, and Simona Spânu. 2018. Street Food and Street Vendors, a Culinary Heritage? In Innovative Business Development—A Global Perspective. Edited by Ramona Orăștean, Claudia Ogrean and Silvia Cristina Mărginean. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peimani, Nastaran, and Hesam Kamalipour. 2022. Informal Street Vending: A Systematic Review. Land 11: 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, Deepti, Tooran Alizadeh, and Robyn Dowling. 2024. Smart City Planning and the Challenges of Informality in India. Dialogues in Human Geography 14: 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, Kris. 2020. Future of Unemployment and the Informal Sector of India. ORF. Available online: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/future-of-unemployment-and-the-informal-sector-of-india-63190/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Raveendran, Govindan, and Joann Vanek. 2020. Informal Workers in India: A Statistical Profile. WIEGO Statistical Brief No. 24. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/WIEGO_Statistical_Brief_N24_India.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Recchi, Sara. 2020. Informal Street Vending: A Comparative Literature Review. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 41: 805–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roever, Sally. 2014. Informal Economy Monitoring Study Sector Report: Street Vendors. WIEGO. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/IEMS-Sector-Full-Report-Street-Vendors.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Roever, Sally, and Caroline Skinner. 2016. Street Vendors and Cities. Environment and Urbanization 28: 359–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukmini, S. 2014. 80% in Informal Employment Have No Written Contract. India. The Hindu, August 27. Available online: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/80-in-informal-employment-have-no-written-contract/article61764182.ece (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Saha, Debdulal. 2011. Working Life of Street Vendors in Mumbai. The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 54: 301–25. [Google Scholar]

- Salamandane, Acácio, Manuel Malfeito-Ferreira, and Luísa Brito. 2023. The Socioeconomic Factors of Street Food Vending in Developing Countries and Its Implications for Public Health: A Systematic Review. Foods 12: 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanlier, Nevin, Aybuke Ceyhun Sezgin, Gulsah Sahin, and Emine Yassibas. 2018. A Study about the Young Consumers’ Consumption Behaviors of Street Foods. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva 23: 1647–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, Oliver Tirtho, Md Abid Hasan, and Shantanu Kumar Saha. 2025. Resilience in the Informal Economy amidst the COVID-19 Crisis: The Experience of Street Vendors in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Urban, Planning and Transport Research 13: 2502001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, Seth. 2017. Beyond a State-Centric Approach to Urban Informality: Interactions between Delhi’s Middle Class and the Informal Service Sector. Current Sociology 65: 248–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhani, Richa, Deepanshu Mohan, and Sanjana Medipally. 2019. Street Vending in Urban ‘Informal’ Markets: Reflections from Case-Studies of Street Vendors in Delhi (India) and Phnom Penh City (Cambodia). Cities 89: 120–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Madhuri. 2017. Quality of Life of Labour Engaged in the Informal Economy in the National Capital Territory of Delhi, India. Khoj: An International Peer Reviewed Journal of Geography 4: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, Nishtha. 2020. Rights of Street Vendors in India. Brillopedia, December 5. Available online: https://www.brillopedia.net/post/rights-of-street-vendors-in-india (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Social Policy Association. 2020. COVID-19: A Shockwave for Street Vendors in India by Shah and Khadiya. Social Policy Association. Available online: https://social-policy.org.uk/spa-blog/covid-19-a-shockwave-for-street-vendors-in-india-by-shah-and-khadiya/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Soon, Jan Mei. 2019. Rapid Food Hygiene Inspection Tool (RFHiT) to Assess Hygiene Conformance Index (CI) of Street Food Vendors. LWT 113: 108304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, Nelia Patricia, Zandile Mchiza, Jillian Hill, Yul Derek Davids, Irma Venter, Enid Hinrichsen, Maretha Opperman, Julien Rumbelow, and Peter Jacobs. 2014. Nutritional Contribution of Street Foods to the Diet of People in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review. Public Health Nutrition 17: 1363–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhunter, Colin. 2025. Decentralised Local Food Systems and the Role of India’s Streetside Fruit & Veg Markets. Countercurrents, April 23. Available online: https://countercurrents.org/2025/04/decentralised-local-food-systems-and-the-role-of-indias-streetside-fruit-veg-markets/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Tucker, Jennifer L., and Manisha Anantharaman. 2020. Informal Work and Sustainable Cities: From Formalization to Reparation. One Earth 3: 290–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffour, Joseph Kwadwo, Michael Oppong, Joseph Gerald Tetteh Nyanyofio, Monney Forziatu Abukari, Mavis Narkwor Addo, and David Brako. 2022. Micro-Entrepreneurship: Examining the Factors Affecting the Success of Women Street Food Vendors. Global Business Review. 09721509211072380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan, Hita, B. Manjunatha, and Harini Nagendra. 2016. Contested Urban Commons: Mapping the Transition of a Lake to a Sports Stadium in Bangalore. International Journal of the Commons 10: 265–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwitije, Claudine. 2016. Contributions of Street Vending on Livelihood of Urban Low Income Households in the City of Kigali, Rwanda. University of Nairobi. Available online: https://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/97752/Uwitije_Contributions%20of%20Street%20Vending%20on%20Liveli-hood%20of%20Urban%20Low%20Income%20Households%20in%20the%20City%20of%20Kigali%2c%20Rwanda.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- van Eck, Emil, and Jan Rath. 2024. Stigmatizing Street Vendors and Market Traders: The Case of Amsterdam from a Historical Perspective. Journal of Urban History 50: 1338–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayarangakumar, Mridula. 2024. Study: Delhi Street Vendors Suffer Health Issues, Financial Losses Due to Heatwaves. Frontline, June 20. Available online: https://frontline.thehindu.com/environment/delhi-heatwave-street-vendors-affected-most-climate-crisis-greenpeace-india-national-hawkers-federation/article68311112.ece (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- WIEGO. n.d. Informal Workers and the Law. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/informal-economy/articles/informal-workers-and-law/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Winarno, F. G., and A. Allain. 1991. Street Foods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Asia. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/u3550t/u3550t08.htm (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zook, Sandy. 2017. Subsistence Urban Markets and In-Country Remittances: A Social Network Analysis of Urban Street Vendors in Ghana and the Transfer of Resources to Rural Villages. Ph.D. thesis, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 114 | 95.0 |

| Female | 6 | 5.0 | |

| Religious Composition | Hindus | 78 | 65.0 |

| Muslims | 42 | 35.0 | |

| Literacy Level | Literate | 84 | 70.0 |

| Illiterate | 36 | 30.0 | |

| Education Level of Literacy (n = 84) | Below 10th | 48 | 57.1 |

| 10th pass & above, but below 12th | 18 | 21.4 | |

| 12th pass & above, but no college degree | 18 | 21.4 | |

| Native State | Uttar Pradesh | 60 | 50.0 |

| Bihar | 24 | 20.0 | |

| Maharashtra | 18 | 15.0 | |

| Rajasthan | 12 | 10.0 | |

| Others | 6 | 5.0 | |

| Location of Business Operation | Churchgate | 28 | 23.3 |

| Dadar | 24 | 20.0 | |

| Tardeo | 18 | 15.0 | |

| Fort | 16 | 13.3 | |

| Mahim | 14 | 11.7 | |

| Bhindi Bazaar | 12 | 10.0 | |

| Nariman Point | 8 | 6.7 |

| Statistic | Duration of Engagement in Street Food Vending (in Years) | Initial Investment (in INR) | Average Daily Expenditure (in INR) | Average Earnings per Day (in INR) | Average Number of Daily Customers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 13.82 | 3775.00 | 1328.33 | 2553.33 | 530.17 |

| Median | 13.00 | 3000.00 | 600.00 | 1200.00 | 250.00 |

| Std. Deviation | 7.592 | 2759.306 | 1603.713 | 2637.119 | 706.216 |

| Minimum | 2 | 500 | 250 | 500 | 50 |

| Maximum | 34 | 10,000 | 7000 | 10,000 | 3000 |

| 25th Percentile | 8.00 | 2000.00 | 400.00 | 925.00 | 102.50 |

| 75th Percentile | 19.00 | 5000.00 | 1400.00 | 3625.00 | 575.00 |

| Dependent Variable: Daily Material Amount | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of engagement in street food vending (in Years) | −22.131 | 3.215 | −6.88 | 0.000 *** |

| Initial investment (in INR) | −0.0705 | 0.0068 | −10.43 | 0.000 *** |

| Average number of daily customers | 0.2569 | 0.083 | 3.09 | 0.002 *** |

| Average earnings per day (in INR) | 0.6933 | 0.0109 | 63.56 | 0.000 *** |

| Constant | 44475.07 | 6460.41 | 6.88 | 0.000 *** |

| Model Summary | ||||

| Number of observations: 120; F (4, 115) = 1260.88, p < 0.001; | ||||

| R-squared = 0.9777; Adjusted R-squared = 0.9769; Root MSE = 303.88 | ||||

| Theme | Description | Quotes from the Focus Group Discussion | Implications/Resilience Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Licensing Issues | Lack of legal recognition and fear of harassment from authorities. | “Those of us who do not have a license are troubled by the municipal authorities and cops frequently. This makes running our business smoothly difficult.” | Lack of licenses makes vendors vulnerable; some rely on unions/associations to collectively resist harassment. |

| Lack of knowledge | Insufficient awareness of procedures to obtain licenses. | “Many of us do not have a license. We also do not have much knowledge of the procedure for obtaining it.” | Information gaps perpetuate informality; need for awareness campaigns or simplified licensing processes. |

| Low and Inconsistent Income | Earnings are meager and fluctuate frequently. | “Our income is not high and not constant. So, we are often faced with monetary issues.” | Vendors rely on informal credit networks, flexible work hours, and family labor to manage financial instability. |

| Exploitation and Corruption | Biased treatment and illegal collection of protection money. | “We are sometimes fined in the name of street hawking and other times for not following the hygiene protocol. Some of us are also charged for the place where we operate our business. These are not fair practices and put a lot of monetary burden on us.” | Monetary exploitation adds pressure; solidarity within unions and associations provides bargaining power. |

| Resilience and Coping Mechanisms | Adaptive strategies in response to adversities. | “No matter what happens, we adjust. If business is slow, we work longer hours; if the police come, we shift places. Family members also help when needed. This is how we manage to survive in this work.” | Dependence on family labor- Informal credit networks- Collective solidarity (unions, associations)- Flexible work patterns to adapt to uncertainty. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhattacharjee, S.; Sattar, S.; Sharma, M. Survival to Dignity? The Precarious Livelihood of Street Food Vendors in South Mumbai and Their Path Toward Decent Work. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120692

Bhattacharjee S, Sattar S, Sharma M. Survival to Dignity? The Precarious Livelihood of Street Food Vendors in South Mumbai and Their Path Toward Decent Work. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(12):692. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120692

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhattacharjee, Sujayita, Sanjukta Sattar, and Madhuri Sharma. 2025. "Survival to Dignity? The Precarious Livelihood of Street Food Vendors in South Mumbai and Their Path Toward Decent Work" Social Sciences 14, no. 12: 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120692

APA StyleBhattacharjee, S., Sattar, S., & Sharma, M. (2025). Survival to Dignity? The Precarious Livelihood of Street Food Vendors in South Mumbai and Their Path Toward Decent Work. Social Sciences, 14(12), 692. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120692