Abstract

Financial literacy, defined as the set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that enable individuals to make informed economic decisions and manage resources efficiently, is fundamental for social inclusion and the reduction of inequalities. This study, through a systematic review of the scientific literature using the PRISMA methodology, selected 120 primary studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and presented a low risk of bias. These studies examined aspects related to financial literacy programs, the populations benefited, their effects, the challenges encountered, and the lessons that can guide the replication of these initiatives. The results show that the most frequent programs include training in basic financial concepts—savings, budgeting, access to banking services and microfinance—as well as workshops, seminars, and group training sessions. The populations most benefited were rural communities and women, although informal workers, migrants, and refugees could also significantly improve their financial inclusion and economic resilience. Among the positive effects, improvements were observed in income and expense management, increased savings, investment planning, preparation for emergencies and retirement, and the strengthening of economic empowerment and the sustainability of microenterprises and small enterprises. These findings highlight the importance of implementing financial literacy programs adapted to specific contexts to promote inclusion and economic well-being.

1. Introduction

Currently, particularly in developing countries, financial literacy has become essential due to the increase in bankruptcies, high levels of indebtedness, and low savings rates. A lack of understanding of complex financial products contributes to financial exclusion, especially among those without access to banking services, as unfamiliarity or lack of trust can limit effective use (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2020b). The 2024 Global Findex Database from the World Bank indicates that approximately 1.3 billion adults lack access to formal financial services, equivalent to nearly 16% of the global adult population, reflecting a relatively low level of financial expansion (World Bank 2025).

In urban societies, the prevalence of a consumerist culture that prioritizes spending over saving, combined with limited financial knowledge and rising prices, hinders adaptation to economic development and planning for a prosperous future. Therefore, financial knowledge is essential, particularly at the family level, as even abundant resources may be managed inefficiently without adequate financial education (Rizliyanto and Sirojuzilam 2017).

There are clear differences in financial development globally. More economically advanced countries lead financial literacy and inclusion programs, demonstrating higher levels of financial integration, whereas countries with uneven development show average performance in these areas (Al-shami et al. 2024). Financial knowledge, skills, and beliefs directly influence individuals’ attitudes and behaviors, fostering more responsible and sustainable long-term decisions and contributing to the economic well-being of the population (Asyik et al. 2022).

Financial literacy encompasses the ability to understand and use tools to manage personal finances, including budgeting, saving, investing, and proper debt management, as well as skills, competencies, attitudes, and beliefs related to financial decision-making, self-control, and risk management. Its development promotes financial stability, increases savings, enhances inclusion through effective access to products and services, improves decision-making, and facilitates strategic planning for education, assets, and retirement (Tulcanaza-Prieto et al. 2025).

Furthermore, financial education strengthens integration into the financial system by facilitating access to bank accounts, financial assistance, and investment opportunities, benefiting individuals with both low and high incomes, as well as micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises and small farmers, who still face financial exclusion and difficulties in accessing formal credit (Akande et al. 2023). Financial literacy is evaluated through the capacity to plan and manage resources, understand financial concepts and terminology, use technology, manage risks, and analyze financial statements to make informed and effective decisions (Listyaningsih et al. 2024).

Background

Financial literacy has its roots in the United States with the Smith-Lever Act of 1914, designed to equip the population with financial skills applicable to business activities. This initial approach gained greater relevance with the liberalization of the financial market in 1998, and later, the OECD promoted international campaigns to encourage financial literacy, emphasizing its role in improving personal economic management and inclusion in financial markets (Bojuwon et al. 2023). In this way, financial literacy has become a key component not only for acquiring knowledge but also for applying it effectively in daily life.

In this context, financial literacy is defined as the combination of knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors necessary to make sound financial decisions and achieve personal economic well-being. Unlike financial education, which focuses on teaching concepts, financial literacy involves practical application. Its focus varies according to access to financial services: while those with bank access require knowledge of taxes, insurance, and credit, the unbanked focus on saving, budgeting, and responsible borrowing (Mani 2022; Showkat et al. 2025). In this way, financial literacy becomes a tool for managing resources in an informed and planned manner, both in the present and the future.

To better understand it, the OECD structures financial literacy into three interrelated dimensions: financial knowledge, financial attitude, and financial behavior (Al-shami et al. 2024). Financial knowledge enables the management of income, expenses, and savings; financial attitude reflects the willingness to act favorably in economic decisions; and financial behavior translates these learnings into habits of saving, responsible spending, and investing. This perspective is complemented by the proposal of Masrizal et al. (2024), which identifies five fundamental aspects: understanding and explaining financial concepts, personal management skills, making sound financial decisions, and confidence in future planning. Thus, financial literacy extends beyond theoretical knowledge, materializing in effective and sustainable economic decisions.

The link between financial knowledge and behavior is explained by the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which posits that decisions regarding savings, budgeting, and the use of financial services depend on intention, influenced by attitude, perceived control, and social norms (Alqam and Hamshari 2024). Early socialization, through parental influence and communication about finances, shapes these perceptions from youth, strengthening positive attitudes, favorable social norms, and the ability to make informed decisions. This theoretical framework demonstrates that financial literacy not only increases knowledge but also transforms behaviors and strengthens financial inclusion.

Moreover, financial literacy is directly related to economic growth and financial inclusion. Studies show that active participation of individuals and households in financial systems promotes investment, innovation, and economic stability, yet inclusion alone does not guarantee efficiency if users lack financial education (Akpene Akakpo et al. 2022). Therefore, combining financial literacy and inclusion enhances economic development and improves individuals’ capacity to seize opportunities in formal markets, reducing dependence on informal alternatives (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2017a).

This relationship extends to entrepreneurship, where financial knowledge translates into adequate planning, savings and debt management, access to financing, and business sustainability (Popoola 2025; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2025). A lack of literacy leads to poor management of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), limiting growth and stability. Acquiring financial knowledge improves personal skills and strengthens business capacity and strategic decision-making, ensuring viability and expansion.

Previous studies support these findings. Çiğdem and Terence (2024) highlight that lifelong financial literacy contributes to economic security, especially for vulnerable groups such as women, rural populations, and low-income households. Complementarily, Das (2024) notes that despite advances in access to financial services, barriers related to knowledge, trust, and infrastructure persist, making contextually adapted financial education programs essential.

At the same time, financial technology (fintech) has transformed the management of economic resources, offering accessible digital platforms that facilitate secure and cost-effective transactions, particularly in areas with limited traditional banking, thus promoting financial inclusion (Amnas et al. 2024). Valencia et al. (2023), through a bibliometric study using the PRISMA methodology, show an increase in research on financial education and its relationship with inclusion, highlighting educational strategies, microcredits, and digital technologies aimed at vulnerable populations.

Kaur and Verma (2022), through a systematic literature review over the last two decades, emphasize that financial literacy is a determining factor for sustainable economic development, poverty reduction, and inclusion in financial systems. However, they note that the effectiveness of programs depends on method, quality, and duration, and recommend longitudinal studies to evaluate long-term impacts.

From a critical pedagogical perspective, Birochi and Pozzebon (2016) argue that financial training programs must be adapted to the local context, considering educational habits, financial practices, available technologies, and social interactions. Only by integrating financial education into broader economic and social development plans can autonomy, informed decision-making, and collective well-being be strengthened, promoting responsible and sustainable financial practices tailored to local realities.

International evidence reinforces the relevance of financial education as a mechanism to reduce economic inequality and promote social inclusion. Lusardi et al. (2017) demonstrated that financial education explains a substantial part of wealth inequality in the United States, while Gallo and Sconti (2024) found that improvements in financial knowledge are associated with a decrease in inequality in Italy. Similarly, Entorf and Hou (2018) argue that unequal access to financial markets constitutes one of the main causes of economic inequality and that financial education policies can help mitigate this structural gap.

In this regard, Oliver-Márquez et al. (2022) highlight that financial knowledge has redistributive effects: an increase in financial literacy reduces income inequality in contexts with low educational levels, although this effect may reverse beyond a certain threshold. The authors also emphasize the role of variables such as institutional quality and general education levels in shaping inequality. Likewise, Lo Prete (2013) observes that income inequality grows less in countries with higher economic literacy and that financial development only contributes to equity when accompanied by a solid foundation of economic knowledge. These findings support the idea that financial literacy enhances individual decision-making and constitutes a structural factor in reducing inequalities and promoting sustainable economic inclusion.

As evidenced by previous literature, financial literacy is an important component for fostering social inclusion and reducing economic inequalities. Despite advances in the expansion of financial services, millions of people worldwide still lack access to formal financial products and services, mainly due to limited or no financial knowledge. This situation reveals a significant gap in economic participation among certain population groups, including women, rural residents, and marginalized communities. Lack of financial literacy restricts individuals’ ability to manage resources, plan for the future, and face economic emergencies, while also perpetuating social and economic inequality across regions and demographic groups, limiting opportunities for sustainable growth and development.

In this context, it is important to analyze how financial literacy can serve as an effective tool to promote economic, social, and financial inclusion. Programs and strategies implemented in different countries and communities vary significantly in focus, coverage, and effectiveness, highlighting the need to identify and systematize best practices. A systematic literature review is proposed as a rigorous and reliable method to collect, evaluate, and synthesize existing evidence, allowing for the identification of success patterns, barriers, and challenges, as well as lessons applicable to diverse socio-economic and cultural contexts. Based on this approach, the study seeks to answer the following research questions:

- What financial literacy programs have been implemented in various social contexts?

- Which vulnerable populations have these financial literacy programs targeted?

- What effects does financial literacy have on individuals’ economic well-being?

- What is the influence of financial literacy on entrepreneurship?

- What challenges are encountered in the implementation of financial literacy programs?

- What lessons and recommendations can be derived to replicate these programs in other countries or communities?

This approach allows for the identification of key aspects related to the topic and existing literacy programs, providing valuable information for the design of future interventions adapted to the cultural, technological, and socio-economic needs of the most vulnerable groups, thereby contributing to financial inclusion, reduction of inequalities, and strengthening of population economic well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

To address the objectives of this research, a systematic literature review methodology was employed, following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. This approach allows for the identification, selection, and synthesis of available scientific evidence in a transparent and reproducible manner, minimizing bias throughout the review process. The PRISMA methodology emphasizes the establishment of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, systematic searches in academic databases, quality assessment of selected studies, and structured organization of findings (Page et al. 2021). Its application ensures that the results reflect the current state of knowledge on the topic, enabling the extraction of robust conclusions and well-founded recommendations for future interventions and public policies.

All project procedures, datasets, and related materials are archived and publicly available through the OSF Records and Supplementary Materials. Instructions for accessing these resources are included in the document’s Data Availability Statement, ensuring transparency and open access to project materials.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria and Information Sources

For evidence collection, internationally recognized and high-impact scientific databases were selected, specifically Scopus and Web of Science, due to their broad coverage, disciplinary diversity, and high-quality indexed studies. In the case of Web of Science, the Emerging Sources Citation Index was excluded because these publications are still consolidating and may not meet the required standards of visibility and methodological rigor.

Eligibility criteria included studies published in any language that contained only the key terms related to the research in the title, to maintain a focused scope on financial literacy, social inclusion, and inequality reduction. Including additional terms or sections often produced dispersed and less relevant results. The search was limited to studies published in the last ten years (2015–2025) and included scientific articles, conference papers, systematic reviews, and book chapters, ensuring that the data collected were recent, relevant, and of verified academic quality. This strategy guarantees that the systematic review captures reliable and representative evidence on trends, impacts, and approaches to financial literacy across different contexts.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy was initiated in the Scopus database, using two search blocks for the main variables of the study, financial literacy and inclusion. Preliminary results were analyzed using R Studio (version 4.4.2) with the biblioshiny tool, allowing the identification of additional relevant terms that may have been initially overlooked. The final search was executed on 28 August 2025, and repeated twice to ensure the inclusion of the most pertinent terms. Filters were applied in both databases based on the eligibility criteria, limiting results to titles and considering only studies published in the last decade. This methodology ensured the relevance, timeliness, and academic quality of the selected studies (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strings and results.

2.3. Study Selection Process

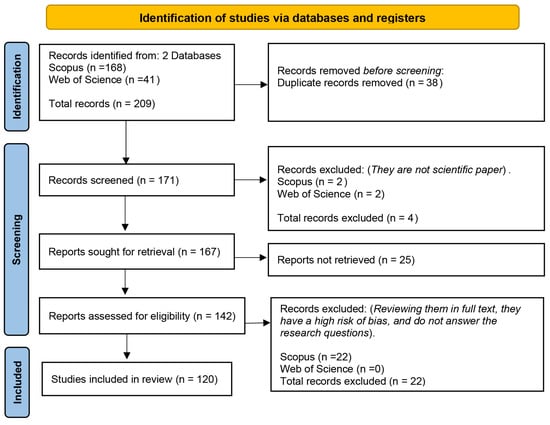

The study selection process began with a total of 209 records retrieved from the two selected databases. Of these, 38 duplicates were removed, leaving 171 studies for the initial review stage. During this phase, titles, abstracts, and keywords were analyzed to determine whether the studies primarily focused on the research topic and could provide relevant information to address any of the research questions. Since the initial search was limited to titles, all resulting studies were aligned with the topic, and only 4 studies were excluded for not meeting scientific rigor criteria, consisting mainly of slide-type presentations.

In the next stage, full texts were sought for the remaining 167 studies; however, 25 studies could not be retrieved, resulting in a total of 142 studies. These were subjected to a risk of bias analysis, evaluating methodological robustness and relevance to the research questions. As a result, 20 studies were excluded due to high risk of bias or because they did not address any of the research questions. Finally, 120 studies meeting the quality and relevance criteria were selected, forming the final basis for answering the research questions of this study (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

2.4. Bias Risk Assessment

The risk of bias was evaluated systematically throughout the entire review process, following clear inclusion and exclusion criteria that allowed the selection of the most relevant and reliable studies. Emerging journals in Web of Science were excluded, considering that their consolidation did not yet guarantee an adequate level of methodological rigor. The analysis was conducted collaboratively among the authors, reviewing titles, abstracts, and full texts, and resolving any discrepancies by consensus to ensure objectivity and transparency. Additionally, criteria from the Cochrane Collaboration were adapted to assess aspects such as randomization, blinding of participants and evaluators, data integrity, and risk of selective reporting, adjusting the criteria according to the methodology of each study. This process enabled the identification and exclusion of studies with high risk of bias, particularly those with unclear methodologies, incomplete data, or weak conclusions, thereby strengthening the validity and reliability of the studies included in the systematic review.

2.5. Synthesis Methods

To synthesize the results, the most relevant data from each study were extracted, focusing on characteristics, findings, and evidence directly related to the research questions. The collected information was organized in an Excel matrix, allowing for structured visualization and facilitating analysis. Given the variations in format and detail across studies, the data were classified and grouped into thematic categories, which enabled the organization of similar elements and the creation of a coherent framework that summarized the most significant findings clearly and concisely.

3. Results

This section presents a synthesized overview of the main findings derived from the literature review. It highlights the programs and themes implemented, the vulnerable populations most frequently targeted, the positive effects observed on participants’ economic and social well-being, the challenges associated with implementation, and the lessons and recommendations that could be replicated in other contexts. A notable aspect is that the majority of the analyzed studies are concentrated in Asia, particularly Indonesia, reflecting a higher interest and development of financial literacy initiatives in this region; however, isolated studies from other parts of the world were also identified, demonstrating global interest in the topic.

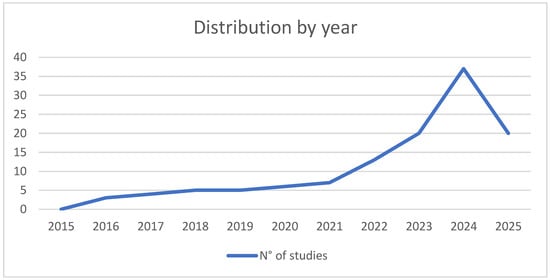

Regarding the distribution over time, there is a gradual increase from 2015 to 2020, followed by a sustained and accelerated growth from 2021, reaching a peak in 2024 (see Figure 2). This trend reflects a growing academic interest in financial literacy as a strategy for social inclusion and the reduction of inequalities. Although a noticeable decrease is observed in 2025, this is likely due to the year not yet being complete, and publication records may not yet be fully reported.

Figure 2.

Distribution of studies by year.

3.1. Financial Literacy Programs and Themes Identified in the Studies

This section describes the financial literacy programs and themes identified in the reviewed studies. Table 2 provides a synthesized overview of the main topics addressed, the types of programs implemented worldwide, and the studies reporting them. This organization allows for a clear visualization of the most common strategies, the pedagogical approaches employed, and the prioritized content, facilitating an understanding of how these programs have been structured and the objectives they aim to achieve across different social and cultural contexts.

Table 2.

Categories and financial literacy programs reported in the literature.

The reviewed studies show that financial literacy programs can be grouped into three main categories according to their focus and level of specialization. Basic training covers fundamental financial concepts, savings, budgeting, compound interest, inflation, risk diversification, access to banking services and microfinance, as well as education on financial terms, risk analysis, and investment evaluation. This training is delivered through workshops, seminars, business clinics, community talks, literacy campaigns, and local cooperatives or social structures to promote community participation.

Advanced and specialized training focuses on financial management, investment planning, credit, markets, business finance, and SMEs, including instruction in numeracy, financial calculations, liquidity, stocks, and bonds, as well as education on Islamic finance and Sharia-compliant financial products. Programs include workshops and sequential modules on savings, financial priorities, loan management, and long-term planning, along with approaches that integrate the social and environmental dimensions of financial decision-making. Digital platforms, gamified mobile applications, chatbots, online lectures, and MOOCs are employed to expand reach and facilitate financial inclusion.

Programs targeting specific groups focus on women, rural communities, and vulnerable populations. These include training in shelters for women victims of gender-based violence, workshops for women entrepreneurs and rural women, and initiatives promoting economic empowerment and the use of digital financial services in rural areas. These programs stand out for their context-specific adaptation and for combining financial education with the strengthening of social inclusion and economic autonomy among participants.

3.2. Vulnerable Populations

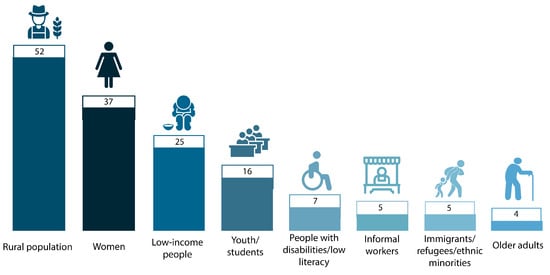

Identifying vulnerable populations is a central aspect of financial literacy research, as it helps understand which groups programs have targeted and which require priority attention to enhance economic and social inclusion. Recognizing these populations guides the development of more effective financial education strategies tailored to specific contexts, ensuring that resources and interventions reach those who need them most. Figure 3 presents the main vulnerable populations identified in the reviewed studies, along with the number of investigations addressing each group, providing a clear overview of the approaches adopted by financial literacy programs across diverse contexts.

Figure 3.

Number of studies that mention each vulnerable population.

The population groups most targeted by financial literacy programs in the reviewed studies are primarily rural communities, including families, farmers, women, and rural youth (Sam-Abugu et al. 2025; Desai et al. 2024; Rusliati et al. 2024; Suyanto 2024; Akande et al. 2023; Kumari and Azam 2019; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2016a). This category is prioritized due to the limited availability of formal financial services in remote areas, as well as cultural and educational barriers that hinder financial inclusion. Programs targeting these populations commonly combine community workshops, education in local institutions, and the use of materials adapted to participants’ realities, aiming to promote practical skills in savings, investment, and debt management (Akande et al. 2023; Schoofs 2022; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2016b).

Women are another key focus group, including rural women, entrepreneurs, homemakers, victims of violence, and those in socioeconomically vulnerable situations (Mishra and Sahoo 2025; Showkat et al. 2025; Zahid et al. 2024; Patnaik et al. 2024; Ordoñez et al. 2024; Miled and Landolsi 2024; Mishra et al. 2021; Warren et al. 2019). This emphasis reflects the importance of empowering women to make informed financial decisions, access banking services, and use digital tools safely.

Low-income or marginalized populations, including poor households, communities with structural financial barriers, and participants in social service programs, represent another target group. Financial literacy programs for this population focus on improving understanding of financial products and services, promoting responsible decision-making, and fostering inclusion in formal banking systems or alternative microfinance options (Çiğdem and Terence 2024; Bojuwon et al. 2023; Hasan et al. 2022; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2020a).

Youth and students, both in rural and urban communities, are also a central focus. Programs aim to enhance basic financial knowledge, planning skills, and the capacity for autonomous financial decision-making, often integrating school activities, university workshops, and digital learning platforms (Masrizal et al. 2024; Alqam and Hamshari 2024; Jamil et al. 2023; Gunawan et al. 2023; Medina-Vidal et al. 2023).

People with disabilities and individuals with limited education, including illiterate or low-literacy participants, are addressed in fewer programs. These interventions provide adapted financial education using simple materials and accessible methodologies (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2024; Singh and Misra 2024; Mpofu 2023; Khan et al. 2022; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2020a).

Older adults and informal workers are less frequently targeted but are included in some studies. Programs for older adults address financial security, pension planning, and managing fixed incomes. For informal workers, training focuses on payment management, savings, and access to financial services adapted to their employment conditions (Popoola 2025; García et al. 2024; Ortiz et al. 2024; Mpofu 2023; Rizliyanto and Sirojuzilam 2017).

Finally, immigrants, refugees, and marginalized ethnic groups, though less frequently studied, face additional barriers to financial access and comprehension. Programs targeting these populations aim to provide tools for financial inclusion, consumer rights education, and awareness of specific financial products, taking into account cultural diversity and socioeconomic challenges (Çiğdem and Terence 2024; Jalota et al. 2024; Khan et al. 2022; Lyons and Kass-Hanna 2021; Warren et al. 2019).

3.3. Effects of Financial Literacy on Individual Well-Being

Understanding the effects of financial literacy on individual well-being facilitates recognition of its impact on economic inclusion and quality of life. Analyzing these effects highlights how financial education programs contribute to more informed decision-making, increased savings, effective access to financial services, and strengthened economic resilience. Table 3 presents these effects and benefits in a categorized and synthesized manner, along with the studies reporting them, providing a clear overview of the observed impacts across different contexts and populations.

Table 3.

Benefits and impacts of financial literacy highlighted in the literature.

Financial education has a direct impact on individuals’ financial management and decision-making by equipping them with the knowledge and skills to plan income and expenses, create budgets, optimize savings, and make informed investment decisions. For instance, it enables individuals to determine when to take a loan, how to allocate household expenditures, plan retirement strategies, or evaluate insurance options. This contributes to reducing financial risks, avoiding unnecessary debt, and making responsible choices that strengthen economic resilience in the face of unforeseen events.

Increased savings and effective resource management are another central outcome of financial literacy. Individuals learn to build a solid credit history, maintain bank accounts, leverage mobile banking services, generate cash flow, control expenditures, and set aside emergency funds. Additionally, it encourages the use of formal financial products such as fund transfers, loans, microcredits, insurance, and investments, expanding access to resources and reinforcing financial inclusion, particularly for women and vulnerable groups.

Financial education also contributes to economic and social empowerment by increasing economic independence and long-term planning capacity. For example, it enhances women’s participation in the formal financial sector, promotes responsible debt management, regular savings, and strategic investment. These skills enable individuals and households to reduce inequality gaps, access employment opportunities, improve the performance of microenterprises and small enterprises, and develop sustainable livelihoods.

In the business domain, financial literacy strengthens the management and sustainability of MSMEs by providing skills in budgeting, capital planning, expense control, investment assessment, and efficient use of funds. Entrepreneurs can strategically use loans or credit lines, improve cash flow management, and make informed decisions regarding product diversification or insurance, thereby enhancing competitiveness and business sustainability.

Financial education also fosters overall well-being and economic stability by improving confidence in resource management, the capacity to cope with financial shocks, and responsible use of financial products. Examples include transitioning from informal to formal loans, increasing savings, reducing investment risks, utilizing insurance, and planning for retirement. Collectively, these practices reinforce financial inclusion, promote economic independence, and contribute to sustainable development and the holistic well-being of individuals and communities.

3.4. Influence of Financial Literacy on Entrepreneurship

Financial literacy serves as a crucial tool for fostering entrepreneurship, as it equips entrepreneurs with the skills and knowledge needed to effectively manage their business finances. When entrepreneurs understand key concepts such as capital management, budget planning, credit access and utilization, and smart investment, they are better positioned to make informed decisions, reduce risks, and enhance the sustainability of their ventures (Nihaya et al. 2024; Purwidianti et al. 2024; Mushtaq et al. 2024; Marla et al. 2023; Raza et al. 2023; Asyik et al. 2022; Agabalinda and Steel 2021).

The literature shows that training in financial competencies reduces information asymmetry, increases confidence in financial institutions, and decreases vulnerability to economic shocks (Fanta and Mutsonziwa 2021; Hong et al. 2022), factors that are essential in contexts where informality and limited financial education are prevalent. Moreover, studies indicate that training programs adapted to the sociocultural contexts of entrepreneurs foster knowledge appropriation, contribute to business formalization, and promote innovation in management strategies (Raza et al. 2023; Agabalinda and Steel 2021; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2016b).

Furthermore, participatory and multicultural approaches to the design and implementation of financial education programs (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2018; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2016b) have proven effective in addressing disparities and strengthening the social capital necessary for entrepreneurial development. Empirical evidence also suggests that integrating financial literacy into educational curricula can have intergenerational effects, fostering an entrepreneurial culture that transcends generations and promotes local economic growth (Warren et al. 2019; Grohmann et al. 2018).

Therefore, financial literacy represents a critical input for strengthening entrepreneurship, particularly in vulnerable or developing contexts where limited financial knowledge restricts informed decision-making and access to adequate financial resources. The implementation of adapted, inclusive, and sustainable educational programs that incorporate digital tools constitutes a key strategy to enhance entrepreneurship’s impact on local economies and to reduce social inequalities.

3.5. Challenges

The main challenges surrounding financial literacy are diverse and manifest at multiple levels. At the socio-cultural level, barriers arise from tradition, religion, and structural discrimination, particularly affecting women and vulnerable groups (Banna 2025; Peter et al. 2025; Hasan et al. 2022; Liu et al. 2021). Cultural resistance, distrust toward financial institutions, and limited perception of the importance of financial education hinder individuals from applying acquired knowledge (Masrizal et al. 2024; Raza et al. 2023; Hong et al. 2022). Additionally, the insufficiency of inclusive and personalized educational programs, combined with the lack of approaches tailored to diverse contexts, reduces the effectiveness of financial literacy initiatives and perpetuates socio-economic inequalities (Pandey et al. 2025; Widyastuti et al. 2024a; Raza et al. 2023; Shen et al. 2018).

From an educational and public policy perspective, program fragmentation, low coverage, and limited measurement of actual impact are observed (Wealth et al. 2023; Christiani and Kastowo 2022; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2016b). Many programs remain theoretical, with inadequate resources, minimal integration of digital skills, and unsustainable long-term approaches (Alqam and Hamshari 2024; Harahap et al. 2024; Miled and Landolsi 2024; Ristati et al. 2024; Widiyatmoko et al. 2024). The disconnect between educational offerings and local needs, absence of standardized curricula, lack of institutional support, and limited teacher training hinder the development of robust financial competencies (Al-shami et al. 2024; Wealth et al. 2023). These factors contribute to persistent financial exclusion, inequality in access to formal services, and difficulty in promoting sustainable financial behaviors (Zahid et al. 2024; Koomson et al. 2020; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2020a).

Limited infrastructure and low penetration of digital services, such as mobile money accounts—particularly in rural and low-resource contexts—also constitute significant barriers (Sam-Abugu et al. 2025; Mishra and Sahoo 2025; Tulcanaza-Prieto et al. 2025; Das 2024; Hasan et al. 2022; Shen et al. 2018). This technological gap combines with connectivity restrictions, low digital literacy, and gender inequalities, complicating access to financial products and active participation in the formal economy (Showkat et al. 2025; Jalota et al. 2024; Ortiz et al. 2024; Widyastuti et al. 2024a; Zaimovic et al. 2024). The lack of tailored financial services and the complexity of financial products also generate distrust and limit the adoption of digital tools (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2024; Andriamahery and Qamruzzaman 2022; Kartawinata et al. 2021).

3.6. Lessons Learned and Recommendations

Experiences in financial education indicate that technological infrastructure and internet access are essential to expand financial inclusion, particularly in rural areas (Sam-Abugu et al. 2025; Zaimovic et al. 2024; Song et al. 2024; Gunawan et al. 2023; Lyons and Kass-Hanna 2021). Improving connectivity and translating financial content into local languages (Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2025; Mpofu 2023) facilitates comprehension and program impact, allowing diverse communities to leverage financial services, mobile banking, transfers, and digital investment and savings platforms (Chetioui et al. 2025; Nutassey et al. 2024; Purwidianti et al. 2024). This democratized access contributes to reducing economic and social gaps by enabling traditionally excluded individuals to participate actively in the economy and improve their well-being.

Financial literacy programs should be tailored to the cultural, socioeconomic, and demographic needs of each community (Chetioui et al. 2025; Popoola 2025; Medina-Vidal et al. 2023). The involvement of local actors in program design, continuous training, and ongoing support are crucial to ensure that education is relevant and effective (Popoola 2025; Widiyatmoko et al. 2024; Schoofs 2022). Integrating content into school and university curricula, offering practical seminars, and promoting awareness campaigns consolidates skills such as budgeting, savings, debt management, and the use of financial technologies (Tulcanaza-Prieto et al. 2025; Rahayu et al. 2023; Ferrada and Montaña 2022; Adetunji and David-West 2019). Enhancing these competencies strengthens individual economic autonomy and promotes equal opportunities and inclusion of vulnerable groups, including women, youth, and rural populations.

Multisectoral collaboration is a key factor for the success of these initiatives. Governments, financial institutions, community organizations, and academics must work together to develop supportive policies, promote financial technologies, and foster trust in digital platforms (Sochimin 2025; Miled and Landolsi 2024; Majid et al. 2023; Mutamimah and Indriastuti 2023; Christiani and Kastowo 2022). This combined approach strengthens financial literacy, economically empowers women and vulnerable populations, and enhances the sustainability of microenterprises and small enterprises. By generating equitable economic capacities and access to financial resources, broader social inclusion is promoted, structural inequalities are reduced, and participation of all sectors in the formal economy is encouraged.

Integrating financial education with access to credit, markets, and practical services—combined with FinTech tools, management applications, and digital resources—is recommended (Sam-Abugu et al. 2025; Ortiz et al. 2024; Purwidianti et al. 2024; Song et al. 2024; Widiyatmoko et al. 2024; Desai et al. 2022; Kirana and Havidz 2020). Programs that include real entrepreneurial experiences, peer networks, and training in emerging technologies enhance economic autonomy and social inclusion, enabling individuals to develop productive projects and actively contribute to community development (Zouitini et al. 2024). Additionally, the use of local financial intermediaries and adapted educational materials (Schoofs 2022; Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. 2016a) ensures that programs reach the most vulnerable groups, reducing gender and social disparities, and promoting economic equity.

The lessons learned emphasize the need for coordinated policies, continuous evaluation, and context-specific approaches. Financial education must be comprehensive, culturally sensitive, up-to-date, and adapted to different life stages. Strengthening digital skills, protecting consumers, integrating content into formal education, and promoting community participation ensures that programs not only transmit knowledge but generate sustainable economic well-being, foster social inclusion, and contribute to reducing economic and gender inequalities, facilitating more equitable and just development for all communities.

4. Discussion

The results indicate that financial literacy programs implemented worldwide have adopted varied approaches, although some stand out for their frequency and coverage. As noted by Okello Candiya Bongomin et al. (2025) and Lyons and Kass-Hanna (2021), the most recurrent programs include training in basic financial concepts, covering savings, budgeting, compound interest, inflation, and risk diversification, as well as access to banking services and microfinance for the unbanked (Desai et al. 2022; Agabalinda and Steel 2021). These initiatives are complemented by practical strategies such as workshops, seminars, community talks, and group trainings designed to strengthen financial skills and foster active participation in the economy, aligning with findings by Popoola (2025) and Arsyianti and Kassim (2018).

An especially relevant aspect is the expansion of programs focused on Islamic finance and Sharia-compliant financial products, aimed at populations requiring instruments compatible with religious principles. As highlighted by Kamal et al. (2025) and Masrizal et al. (2024), these programs teach fundamental concepts of savings, investment, and financial planning in accordance with Sharia, avoiding interest and ensuring fairness in transactions. This educational approach aligns with Aisyah et al. (2024), who report that it promotes inclusion for communities that, due to cultural or religious reasons, might otherwise be excluded from conventional financial systems.

Regarding target populations, results show that financial literacy programs mainly focus on rural areas, where access to financial services is limited and economic exclusion is more pronounced. This trend is consistent with reports by Zaimovic et al. (2024), Sui and Niu (2018), and Atta-Aidoo et al. (2023), which indicate that urban residents have greater access to financial products such as payments, insurance, and credit, while rural populations face significant barriers to financial inclusion.

Women also constitute a priority group due to gender gaps, cultural or religious restrictions, and lower participation in formal financial systems, in line with findings by Klapper et al. (2016) and Hasan et al. (2022). Women’s participation in financial education programs strengthens their economic autonomy, resource management capabilities, and inclusion in financial markets.

Furthermore, less-attended populations such as informal workers, migrants, and refugees represent highly vulnerable groups. Including these populations in financial education initiatives can significantly improve access to formal financial services, enhance decision-making capabilities, encourage savings, and increase financial solvency. Therefore, it is essential to place greater attention and targeted efforts on these underserved groups to promote financial inclusion and reduce socioeconomic inequalities.

In terms of benefits and impacts on individuals, financial literacy strengthens economic well-being by improving income and expense management, savings, investment planning, preparedness for emergencies, and financial resilience. This aligns with Zahid et al. (2024), who emphasize economic empowerment and the ability to cope with unforeseen events. Similarly, Patnaik et al. (2024) highlight that programs adapted to different life stages and delivered through workshops, mentoring, or digital platforms facilitate financial inclusion and economic well-being for individuals and communities.

Acquiring financial knowledge allows individuals to make more informed decisions, manage debt, and plan budgets, increasing economic security. These findings also correspond with Das (2024), who note that financial literacy helps reduce inequalities, encourages sustainable financial habits, and strengthens economic autonomy and participation in formal financial systems.

The main challenges identified in implementing financial literacy programs include limited technological infrastructure, low internet access in rural areas, socio-cultural barriers, gender inequalities, and a lack of specialized training for vulnerable populations, consistent with reports by Das (2024) and Cohen and Nelson (2011). Additionally, limited program coverage, low participation from certain groups, and the absence of standardized methodologies to evaluate educational impact hinder the maximization of benefits, as noted by Kamble et al. (2024), who highlight methodological gaps, demand and supply barriers, and difficulties in reaching vulnerable populations with effective programs.

To overcome these challenges, the literature suggests several strategies. Multisectoral collaboration among governments, financial institutions, community organizations, and academics is key to expanding program reach and effectiveness, as emphasized by Patnaik et al. (2024) and Akande et al. (2023). Adapting content to specific cultural, socioeconomic, and linguistic contexts, including digital components, and leveraging FinTech technologies, as highlighted by Desai et al. (2022), are critical. Financial education should focus on increasing knowledge of financial services, promoting the use of FinTech technologies, and integrating financial education into school and university curricula to enhance participation and ensure meaningful learning (Tulcanaza-Prieto et al. 2025). Continuous training, local support, and systematic impact evaluation are also essential to ensure program sustainability and replicability across different countries or communities, thereby strengthening financial inclusion and contributing to the reduction of economic and social inequalities.

4.1. Practical Implications and Future Research

The findings of this review indicate that financial literacy significantly impacts economic inclusion, individual well-being, and the sustainability of microenterprises and small enterprises. Practically, financial education programs should be designed considering the cultural, social, and technological context of target populations, with particular attention to vulnerable groups such as women and rural communities. Furthermore, it is crucial to increase focus on informal workers, migrants, and refugees, who would significantly benefit from financial literacy to improve their economic well-being and quality of life.

These programs can combine in-person education, digital platforms, and mentorship, covering topics such as savings, budgeting, investment, and access to formal financial services, ensuring that participants acquire skills applicable to daily life. Implementing these interventions strengthens financial inclusion, increases economic resilience, reduces dependence on informal financing sources, and promotes more equitable participation in the economy. Additionally, the findings enable financial institutions, NGOs, and government authorities to prioritize resources, design inclusive policies, and establish monitoring and evaluation mechanisms that ensure sustainable and replicable impact across different communities.

Future research should explore the effectiveness of financial literacy programs in diverse contexts through longitudinal and comparative studies. It is necessary to assess the impact of FinTech technologies, digital platforms, and gamification methods on participation and financial learning. Research should also examine interventions for underrepresented groups, such as informal workers, migrants, and marginalized communities, to design more inclusive strategies. Finally, future studies could investigate how financial literacy contributes to reducing gender inequalities and its relationship with business sustainability and long-term economic stability.

4.2. Study Limitations

Key limitations of this study include the methodological heterogeneity of the reviewed studies, which complicated direct comparisons and the generalization of findings. Additionally, some studies could not be retrieved in full text, reducing the total number of analyzed articles. Although a risk-of-bias assessment was conducted, the diversity of approaches, contexts, and populations studied may influence the interpretation of effects and the applicability of financial literacy programs to other populations or regions.

5. Conclusions

Financial literacy programs developed globally exhibit diverse approaches, combining basic and advanced education to address heterogeneous needs. Among the most recurrent initiatives are training in essential financial concepts such as savings, budgeting, interest, inflation, and risk management; access to banking services and microfinance; and training delivered through workshops, seminars, and community talks. Additionally, there is increasing attention being paid towards specialized programs in Islamic finance and Sharia-compliant financial products, designed for populations requiring instruments compatible with religious principles. The diversity of strategies and modalities, including digital platforms and in-person programs, proves fundamental for effective learning and for fostering active participation in the economy.

Regarding target populations, results indicate that programs primarily focus on rural communities and women, groups that face structural, geographical, and cultural barriers limiting their access to formal financial services. Rural populations have lower availability of banking services, while women are affected by gender inequalities and cultural or religious norms. These findings highlight the need to design inclusive programs tailored to the specific realities of each group, aiming to close gaps in financial access and participation.

The effects of financial literacy on individual economic well-being are broad and profound. Programs enable the management of income and expenses, savings planning, investment, and preparation for emergencies or retirement, thereby strengthening the economic resilience of individuals and their communities. They also contribute to economic empowerment and financial inclusion by facilitating access to formal services, improving decision-making, and fostering autonomy. These benefits extend to the business sector, where financial literacy increases the sustainability, profitability, and performance of micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises, promoting equity and social cohesion, as well as reducing economic and social inequalities.

However, implementing these programs comes with multiple challenges: limited technological infrastructure, low internet penetration in rural areas, cultural and social barriers, gender inequality, the lack of adapted programs, and difficulties in evaluating program impacts hinder effectiveness. Moreover, the complexity of financial products and the low participation of certain groups underscore the need for inclusive, sustainable, and context-specific approaches that consider the diversity of social, economic, and cultural realities.

Key lessons and recommendations emerge from the reviewed experiences for future interventions. Multisectoral collaboration among governments, financial institutions, community organizations, and academic institutions, combined with the integration of financial education into formal education and the use of digital tools, expands program reach and effectiveness. Adapting content to specific cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic contexts, providing continuous training, offering local support, and systematically evaluating impacts are essential strategies to ensure sustainability and replicability. Implementing these approaches can enhance financial inclusion, empower individuals, and significantly contribute to reducing economic and social inequalities, providing a valuable framework for applying programs across different countries or communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14110658/s1, PRISMA_checklist; PRISMA_process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.d.l.Á.H.-M. and M.I.P.-R.; methodology, F.P.P.-S. and K.G.G.-A.; software, A.L.L.-N.; validation, M.d.l.Á.H.-M., M.I.P.-R., F.P.P.-S., and A.L.L.-N.; formal analysis, M.d.l.Á.H.-M. and M.I.P.-R.; investigation, M.d.l.Á.H.-M., M.I.P.-R., F.P.P.-S., K.G.G.-A., and A.L.L.-N.; resources, M.d.l.Á.H.-M.; data curation, M.I.P.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P.P.-S.; writing—review and editing, K.G.G.-A.; visualization, F.P.P.-S.; supervision, M.d.l.Á.H.-M.; project administration, M.I.P.-R.; funding acquisition, M.d.l.Á.H.-M., M.I.P.-R., F.P.P.-S., K.G.G.-A., and A.L.L.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All processes, data, and relevant information associated with this project are publicly accessible through OSF Registries at the following link: https://osf.io/cpvdq, accessed on 25 September 2025. This accessibility facilitates the verification and use of the data by other researchers, in an effort to promote transparency and scientific collaboration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank PhD Martha Romero, Director of Community Engagement at the Universidad Nacional de Chimborazo, for her valuable collaboration on the methodological aspects of the project “Financial Education and Economic Decision-Making among University Students,” of which this scientific article is a part.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbas, Ahmad, Neks Triani, Wa Ode Rayyani, and Muchriana Muchran. 2022. Earnings Growth, Marketability and the Role of Islamic Financial Literacy and Inclusion in Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 14: 1088–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, Olubanjo Michael, and Olayinka David-West. 2019. The Relative Impact of Income and Financial Literacy on Financial Inclusion in Nigeria. Journal of International Development 31: 312–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agabalinda, Colin, and William F. Steel. 2021. Training vs. Informal Financial Services for the Promotion of Financial Literacy and Inclusion in Uganda. Enterprise Development & Microfinance 32: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisyah, Esy Nur, Heri Pratikto, Cipto Wardoyo, and Nurika Restuningdiah. 2024. The Right Literacy on the Right Performance: Does Islamic Financial Literacy Affect Business Performance through Islamic Financial Inclusion? Journal of Social Economics Research 11: 275–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, Joseph, Yiseyon Hosu, Hlekani Kabiti, Simbarashe Ndhleve, and Rufaro Garidzirai. 2023. Financial Literacy and Inclusion for Rural Agrarian Change and Sustainable Livelihood in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Heliyon 9: e16330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpene Akakpo, Agnes, Mohammed Amidu, William Coffie, and Joshua Yindenaba Abor. 2022. Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion and Participation of Individual on the Ghana Stock Market. Cogent Economics & Finance 10: 2023955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqam, Mohammad Ahmad, and Yaser Mohd Hamshari. 2024. The Impact of Financial Literacy on Financial Inclusion for Financial Well-Being of Youth: Evidence from Jordan. Discover Sustainability 5: 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-shami, Samer Ali, Ratna Damayanti, Hayder Adil, Faycal Farhi, and Abdullah Al mamun. 2024. Financial and Digital Financial Literacy through Social Media Use towards Financial Inclusion among Batik Small Enterprises in Indonesia. Heliyon 10: e34902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnas, Muhammed Basid, Murugesan Selvam, and Satyanarayana Parayitam. 2024. FinTech and Financial Inclusion: Exploring the Mediating Role of Digital Financial Literacy and the Moderating Influence of Perceived Regulatory Support. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 17: 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamahery, Anselme, and Md Qamruzzaman. 2022. Do Access to Finance, Technical Know-How, and Financial Literacy Offer Women Empowerment Through Women’s Entrepreneurial Development? Frontiers in Psychology 12: 776844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariana, I. Made, I. Gusti Bagus Wiksuana, Ica Rika Candraningrat, and I. Gde Kajeng Baskara. 2024. The Effects of Financial Literacy and Digital Literacy on Financial Resilience: Serial Mediation Roles of Financial Inclusion and Financial Decisions. Uncertain Supply Chain Management 12: 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsyianti, Laily Dwi, and Salina Kassim. 2018. Financial Prudence Through Financial Education: A Conceptual Framework for Financial Inclusion. Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics 31: 151–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyik, Nur Fadjrih, Wahidahwati Wahidahwati, and Nur Laily. 2022. The Role Of Intellectual Capital In Intervening Financial Behavior and Financial Literacy on Financial Inclusion. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics 19: 805–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta-Aidoo, Jonathan, Saidi Bizoza, Abdulkarim Onah Saleh, and Ester Cosmas Matthew. 2023. Financial Inclusion Choices in Post-Conflict and Fragile States of Africa: The Case of Burundi. Cogent Social Sciences 9: 2216996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banna, Hasanul. 2025. Digital Financial Inclusion and Bank Stability in a Dual Banking System: Does Financial Literacy Matter? Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance 11: 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barus, Elida Elfi, Murah Syahrial, Evan Hamzah Muchtar, and Budi Trianto. 2024. Islamic Financial Literacy, Islamic Financial Inclusion and Micro-Business Performance. Revista Mexicana de Economía y Finanzas Nueva Época REMEF 19: 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskoro, Rahmat Aryo, Rensi Aulia, and Nur Aulia Rahmah. 2019. The Effect of Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion on Retirement Planning. APMBA (Asia Pacific Management and Business Application) 8: 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birochi, Renê, and Marlei Pozzebon. 2016. Improving Financial Inclusion: Towards A Critical Financial Education Framework. Revista de Administração de Empresas 56: 266–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojuwon, Mustapha, Banji Rildwan Olaleye, and Aderemi Abayomi Ojebode. 2023. Financial Inclusion and Financial Condition: The Mediating Effect of Financial Self-Efficacy and Financial Literacy. Vision 2023: 09722629231166200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetioui, Hajar, Hind Lebdaoui, Harit Satt, Youssef Chetioui, and Mohamed Makhtari. 2025. How Does Financial Literacy Contribute to Muslim Females’ Financial Inclusion: The Moderating Effect of Age and Education Using PLS-MGA. Journal of Islamic Marketing. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhatoi, Biswajit Prasad, Sharada Prasad Sahoo, and Durga Prasad Nayak. 2023. Academic Footprint of ‘Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion’: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Global Business and Economics Review 28: 447–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiani, Theresia Anita, and Chryssantus Kastowo. 2022. Increased Financial Literacy and Inclusion Indexes versus the Number of Unlicensed Financial Institutions in Indonesia. Foresight 25: 465–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Monique, and Candace Nelson. 2011. Financial Literacy: A Step for Clients towards Financial Inclusion. Paper presented at 2011 Global Microcredit Summer, Valladolid, Spain, November 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Çiğdem, Akbaş Müzeyyen, and Seedsman Terence. 2024. Financial Literacy as Part of Empowerment Education for Later Life: A Spectrum of Perspectives, Challenges and Implications for Individuals, Educators and Policymakers in the Modern Digital Economy. Economics—The Open-Access, Open-Assessment Journal 18: 20220097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, Sulagna. 2024. Financial Literacy and Education in Enhancing Financial Inclusion and Poverty Alleviation. In E-Financial Strategies for Advancing Sustainable Development: Fostering Financial Inclusion and Alleviating Poverty. Edited by Nadia Mansour, Sukanta Baral and Vikas Garg. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, Ashish Dattaram, Rudra Sensarma, and Ashok Thomas. 2024. Roles of Financial Literacy and Entrepreneurial Orientation in Economic Empowerment of Rural Women Entrepreneurs. Oxford Development Studies 52: 243–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, Kavitha, M. Umasankar, and S. Padmavathy. 2022. FinTech: Answer for Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion in India. ECS Transactions 107: 15317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekayani, Ni Nengah Seri, I. Wayan Kartana, I. Made Wianto Putra, Kadek Diviariesty, Dio Caisar Darma, and Made Setini. 2024. The Mediating Effect of Access to Capital in the Impact of Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion on SME Sustainability. Journal of Corporate Finance Research/Корпоративные Финансы 18: 136–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entorf, Horst, and Jia Hou. 2018. Financial Education for the Disadvantaged? A Review. SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3167709. Social Science Research Network. April 20. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3167709 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Fanta, Ashenafi, and Kingstone Mutsonziwa. 2021. Financial Literacy as a Driver of Financial Inclusion in Kenya and Tanzania. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febriana, Rachel Nevi, and Sylviana Maya Damayanti. 2017. The Relationship Between Demographic Factors Towards Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion Among Financially Educated Student in Institut Teknologi Bandung. Advanced Science Letters 23: 7204–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrada, Luz María, and Virginia Montaña. 2022. Inclusion and Financial Literacy: The Case of Higher Education Student Workers in Los Lagos, Chile. Estudios Gerenciales 38: 211–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, Giovanni, and Alessia Sconti. 2024. Could Financial Education Be a Universal Social Policy? A Simulation of Potential Influences on Inequality Levels. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 46: 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Luis Demetrio Gómez, Gloria María Zambrano Aranda, and Emerson Jesús Toledo Concha. 2024. Dataset on Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion, Informal Financial Business Practices, and Intentions towards Formalization of Female Small Vendors in Lima, Peru. Research Data Journal for the Humanities and Social Sciences 9: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, Antonia, Theres Klühs, and Lukas Menkhoff. 2018. Does Financial Literacy Improve Financial Inclusion? Cross Country Evidence. World Development 111: 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, Ade, Jufrizen, and Delyana Rahmawany Pulungan. 2023. Improving MSME Performance through Financial Literacy, Financial Technology, and Financial Inclusion. International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting 15: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, Zulkifli Ikhwan, Satia Negara Lubis, Erlina, and Evawany Yunita Aritonang. 2024. The Impact of Financial Literacy, Inclusion, and Access on Msme Growth and Welfare in North Sumatra: A Mediating Role of Business Growth. Journal of Ecohumanism 3: 3271–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, Zulkifli Ikhwan, Satia Negara Lubis, Erlina, and Evawany Yunita Aritonang. 2025. Impect of Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion to SMEs Growth and Welfaer in Indonesia. In Sustainable Data Management: Navigating Big Data, Communication Technology, and Business Digital Leadership. Edited by Reem Khamis Hamdan. Cham: Springer Nature, vol. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, Carolyn, and Armond R. Towns. 2019. Plastic Empowerment: Financial Literacy and Black Economic Life. American Quarterly 71: 969–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Rashedul, Muhammad Ashfaq, Tamiza Parveen, and Ardi Gunardi. 2022. Financial Inclusion—Does Digital Financial Literacy Matter for Women Entrepreneurs? International Journal of Social Economics 50: 1085–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Sergio, and Elena Moreno-García. 2025. Savings for emergencies, inclusion and financial education in Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Economia y Finanzas Nueva Epoca 20: e1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Philip Young P., Maria V. Wathen, Alanna J. Shin, Intae Yoon, and Jang Ho Park. 2022. Psychological Self-Sufficiency and Financial Literacy among Low-Income Participants: An Empowerment-Based Approach to Financial Capability. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 43: 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalota, Shikha, Swati Sharma, Mamta Barik, and Sudipa Chauhan. 2024. Financial Literacy and Education in Enhancing Financial Inclusion. In E-Financial Strategies for Advancing Sustainable Development: Fostering Financial Inclusion and Alleviating Poverty. Edited by Nadia Mansour, Sukanta Baral and Vikas Garg. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, Abd Rahim Md, Siong Hook Law, Mohamad Fazli Sabri, and Mohamad Khair Afham. 2023. Does Financial Literacy Improve Financial Inclusion in Developing Countries? A Nonlinearity and Quantile Regression Analysis. Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies 60: 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, Maulana, Meutia Fitri, Yossi Diantimala, and Dedek Saripah. 2025. Exploring the Role of Financial Literacy and Inclusion in Enhancing Islamic Financial Institutions Financing in Specially Regulated Environments. In Leveraging Advanced Technologies: Business Model Innovation and the Future. Edited by Bahaaeddin Alareeni and Allam Hamdan. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, Pawan Ashok, Atul Mehta, and Neelam Rani. 2024. Financial Inclusion and Digital Financial Literacy: Do They Matter for Financial Well-Being? Social Indicators Research 171: 777–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandari, Prashant, Uma Bahuguna, and Ajay Kumar Salgotra. 2021. Socio-Economic based differentiation in financial literacy and its association with financial inclusion in underdeveloped regions: A case study in India. Indian Journal of Economics and Business 20: 147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartawinata, Budi, Mahendra Fakhri, Mahir Pradana, Nouval Hanifan, and Aldi Akbar. 2021. The Role of Financial Self-Efficacy: Mediating Effects of Financial Literacy & Financial Inclusion of Students in West Java, Indonesia. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences 24: 1–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, Amanjot, and Rajit Verma. 2022. Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion: A Systematic Literature Review. ECS Transactions 107: 9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Falak, Muhammad Ayub Siddiqui, and Salma Imtiaz. 2022. Role of Financial Literacy in Achieving Financial Inclusion: A Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda. Cogent Business & Management 9: 2034236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, Anchal, Abhishek Vajjala, and Anirudh Tagat. 2025. Financial Literacy and Inclusion in India: Evidence from Household-Level Data after Demonetization. Journal of Emerging Market Finance 24: 331–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirana, Maria Yohana, and Shinta Amalina Hazrati Havidz. 2020. Financial Literacy and Mobile Payment Usage as Financial Inclusion Determinants. Paper presented at 2020 International Conference on Information Management and Technology (ICIMTech), Bandung, Indonesia, August 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, Leora, Mayada El-Zoghbi, and Jake Hess. 2016. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: The Role of Financial Inclusion. CGAP. [Google Scholar]

- Kodongo, Odongo. 2018. Financial Regulations, Financial Literacy, and Financial Inclusion: Insights from Kenya. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 54: 2851–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, Isaac, Renato A. Villano, and David Hadley. 2020. Intensifying Financial Inclusion through the Provision of Financial Literacy Training: A Gendered Perspective. Applied Economics 52: 375–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D. A. T., and S. M. Azam. 2019. The Mediating Effect of Financial Inclusion on Financial Literacy and Women’s Economic Empowerment: A Study among Rural Poor Women in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research 8: 719–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, Thakshila, and Iti Khalidah. 2020. Financial Literacy: As a Tool for Enhancing Financial Inclusion among Rural Population in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research 9: 2595–605. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Cheng-Wen, and Andrian Dolfriandra Huruta. 2022. Green Microfinance and Women’s Empowerment: Why Does Financial Literacy Matter? Sustainability 14: 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listyaningsih, Erna, Rahyono Rahyono, Apip Alansori, and Amirul Mukminin. 2024. Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion, and Financial Statements on MSMEs’ Performance and Sustainability with Business Length as a Moderating Variable. Ikonomicheski Izsledvania 33: 108–27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Siming, Leifu Gao, Khalid Latif, Ayesha Anees Dar, Muhammad Zia-UR-Rehman, and Sajjad Ahmad Baig. 2021. The Behavioral Role of Digital Economy Adaptation in Sustainable Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 742118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lontchi, Claude Bernard, Baochen Yang, and Yunpeng Su. 2022. The Mediating Effect of Financial Literacy and the Moderating Role of Social Capital in the Relationship between Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Development in Cameroon. Sustainability 14: 15093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Prete, Anna. 2013. Economic Literacy, Inequality, and Financial Development. Economics Letters 118: 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, Annamaria, Pierre-Carl Michaud, and Olivia S. Mitchell. 2017. Optimal Financial Knowledge and Wealth Inequality. Journal of Political Economy 125: 431–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Angela C., and Josephine Kass-Hanna. 2021. Financial Inclusion, Financial Literacy and Economically Vulnerable Populations in the Middle East and North Africa. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 57: 2699–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M. Shabri Abd., Hafasnuddin, Maulidar Agustina, Ridwan Nurdin, Muhammad Haris Riyaldi, and Nurma Sari. 2023. Promoting Financial Inclusion Through Financial Literacy, Socialization, and Commitment to the Implementation of Islamic Financial Institutions’ Law in Aceh, Indonesia. Paper presented at 2023 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Applications (DASA), Annaba, Algeria, September 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, Mukta. 2022. Financial Inclusion Through Financial Literacy: Evidence, Policies, and Practices. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD) 13: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marla, Putri Ghina, M. Shabri Abd. Majid, Said Musnadi, Maulidar Agustina, Faisal Faisal, and Ridwan Nurdin. 2023. Exploring the Nexus Between Digital Finance, Social Capital, Financial Literacy, and Islamic Financial Inclusion in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Paper presented at 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Islamic Business and Finance (SIBF), Manama, Bahrain, September 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masrizal, Raditya Sukmana, and Budi Trianto. 2024. The Effect of Islamic Financial Literacy on Business Performance with Emphasis on the Role of Islamic Financial Inclusion: Case Study in Indonesia. Journal of Islamic Marketing 16: 166–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Vidal, Adriana, Mariana Buenestado-Fernández, and José Martín Molina-Espinosa. 2023. Financial Literacy as a Key to Entrepreneurship Education: A Multi-Case Study Exploring Diversity and Inclusion. Social Sciences 12: 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miled, Kamel Bel Hadj, and Monia Landolsi. 2024. Nexus between Women’s Financial Empowerment, and Digital Financial Literacy: The Case of Green Microfinance in Tunisia. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 8: 279–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Dharmesh K., Sushant Malik, Asmita Chitnis, Dipen Paul, and Subham Sushobhan Dash. 2021. Factors Contributing to Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion among Women in Indian SHGs. Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance 9: 810–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Samanwita, and Chandan Kumar Sahoo. 2025. Impact of Sustainable Financial Literacy and Digital Financial Inclusion on Women’s Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 32: 4166–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Peter J., and Trinh Quang Long. 2020. Financial Literacy, Financial Inclusion, and Savings Behavior in Laos. Journal of Asian Economics 68: 101197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, Favourate Y. 2023. Digital Financial Inclusion and Digital Financial Literacy in Africa: The Challenges Connected with Digital Financial Inclusion in Africa. In Economic Inclusion in Post-Independence Africa: An Inclusive Approach to Economic Development. Edited by David Mhlanga and Emmanuel Ndhlovu. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujiatun, Siti, Budi Trianto, Eko Fajar Cahyono, and Rahmayati. 2023. The Impact of Marketing Communication and Islamic Financial Literacy on Islamic Financial Inclusion and MSMEs Performance: Evidence from Halal Tourism in Indonesia. Sustainability 15: 9868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, Rizwan, Ghulam Murtaza, Dorra Yahiaoui, Ishizaka Alessio, and Qurat-ul-ain Talpur. 2024. Impact of Financial Literacy on Financial Inclusion and Household Financial Decisions: Exploring the Role of ICTs. International Studies of Management & Organization 54: 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutamimah, Mutamimah, and Maya Indriastuti. 2023. Fintech, Financial Literacy, and Financial Inclusion in Indonesian SMEs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management 27: 137–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nihaya, Ina Uswatun, Nunik Dwi Kusumawati, Yuyun Isbanah, Trias Madanika Kusumaningrum, Harlina Meidiaswati, and Rasyidi Faiz Akbar. 2024. Unlocking Regulatory Technology on Fintech Use Among Indonesian Students: A Triad of Financial Literacy, Inclusion, and Risk Tolerance. Paper presented at 2024 12th International Conference on Cyber and IT Service Management (CITSM), Batam, Indonesia, October 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutassey, Victoria Abena, Siaw Frimpong, Samuel Kwaku Agyei, and Doris Amoako. 2024. Financial Literacy Induced Financial Well-Being in Ghana: Does Financial Inclusion Mediate? Thunderbird International Business Review 66: 325–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, Elie Chrysostome, Jean Marie Nkongolo-Bakenda, and Pierre Yourougou. 2025. Toward Increasing Financial Inclusion and Sustainability of Indigenous Microenterprises in Africa in the Presence of Financial Literacy. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, John C. Munene, and Pierre Yourougou. 2020a. Examining the Role of Financial Intermediaries in Promoting Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion among the Poor in Developing Countries: Lessons from Rural Uganda. Cogent Economics & Finance 8: 1761274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, John C. Munene, Joseph Mpeera Ntayi, and Charles Akol Malinga. 2017a. Financial Literacy in Emerging Economies: Do All Components Matter for Financial Inclusion of Poor Households in Rural Uganda? Managerial Finance 43: 1310–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, John C. Munene, Joseph Mpeera Ntayi, and Charles Akol Malinga. 2018. Nexus between Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion: Examining the Moderating Role of Cognition from a Developing Country Perspective. International Journal of Bank Marketing 36: 1190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, Joseph Mpeera Ntayi, and Charles Akol Malinga. 2020b. Analyzing the Relationship between Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion by Microfinance Banks in Developing Countries: Social Network Theoretical Approach. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 40: 1257–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, Joseph Mpeera Ntayi, and John C. Munene. 2017b. Institutional Framing and Financial Inclusion: Testing the Mediating Effect of Financial Literacy Using SEM Bootstrap Approach. International Journal of Social Economics 44: 1727–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, Joseph Mpeera Ntayi, John C. Munene, and Isaac Nkote Nabeta. 2016a. Financial Inclusion in Rural Uganda: Testing Interaction Effect of Financial Literacy and Networks. Journal of African Business 17: 106–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, George, Joseph Mpeera Ntayi, John C. Munene, and Isaac Nkote Nabeta. 2016b. Social Capital: Mediator of Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion in Rural Uganda. Review of International Business and Strategy 26: 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]