Wings or Handcuffs? The Dilemmas of Helicopter Parenting Based on a Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

3.2. Search Strategy

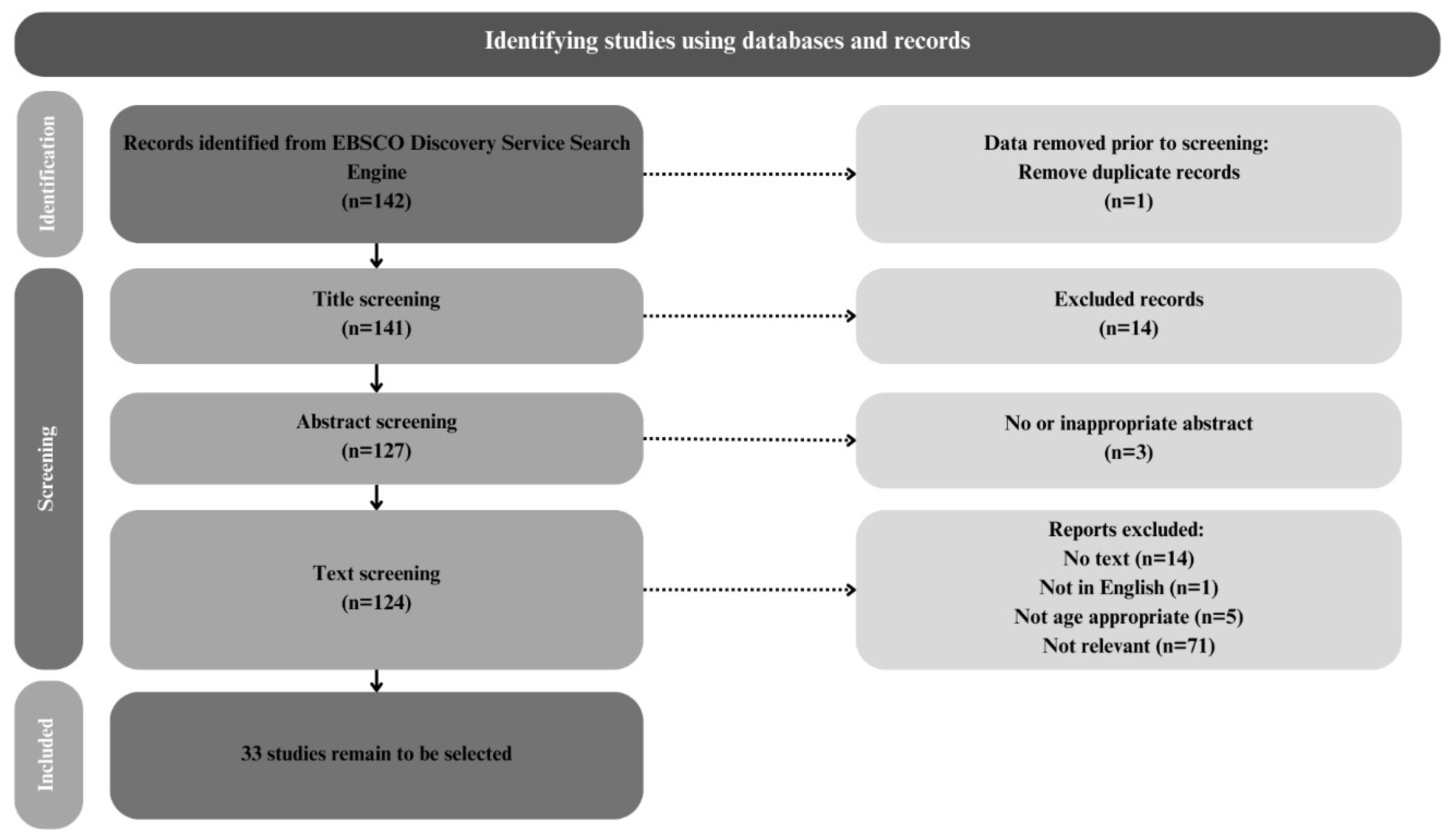

3.3. Selection

4. Results

4.1. Conceptual and Methodological Framework

4.2. Research on Higher Education Students

4.3. Research on Students in Public Education

4.4. Research Focusing on Parents

4.5. Measuring Instruments

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Databases Involved in Data Collection by EBSCO Discovery Service

- Accucoms - COVID-19 resources,

- ACM Digital Library

- Arts & Humanities (ProQuest)

- Bibliotheca Corviniana Digitalis

- Biological Abstracts 2000–2004

- Biomedical & Life Sciences Collection

- BMJ Journals

- Business Source Premier

- CAB Abstracts

- Cambridge Journals

- ChemSpider

- CNKI

- Cochrane

- COMPASS

- Congress.gov

- De Gruyter Journals

- Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ)

- Ebook (Springer)

- Ebook Collection (Ebsco)

- EbookCentral (ProQuest)

- EBSCOHost

- Elsevier

- Elsevier - SciVal

- ELTE Reader

- Emerald

- EMIS University – Central and South - East Europe

- EndNote

- ERIC

- European Parliament Legislative Observatory

- EUR-Lex

- Europeana Collections

- EUROSTAT

- FSTA (Food Science and Technology Abstracts)

- GALE Literary Sources (GLS)

- Gale Reference Complete

- Global Health and Human Rights Database

- Grove Music Online

- HUMANUS

- HUNGARICANA

- IJOTEN,

- Impact Factor (Journal Citation Reports)

- InCites

- International Human Rights Network

- Internet Archive

- JSTOR

- MATARKA

- MathSciNet

- MathSciNet (EBSCOhost)

- MEDLINE (EBSCOhost)

- MEDLINE (PubMed)

- Medscape

- Nature Journals

- NEJM Group - COVID-19 resources

- Nutrition and Food Sciences

- Oxford Handbooks Online (OHO) – Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Oxford Handbooks Online (OHO) – Law

- Oxford Scholarship Online (Law Collection)

- Oxford University Press (OUP) Journals

- Project Gutenberg

- BRITISH JOURNAL OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION Appendix A. Databases involved in data collection by EBSCO Discovery Service19

| 1 | See Hong et al. (2015): The items in the questionnaire were compiled based on previous research and definitions, and the statements were then verified following a panel discussion. (p. 141) |

References

- Bacskai, Katinka, Emese Alter, Beáta Andrea Dan, Krisztina Vályogos, and Gabriella Pusztai. 2024. Positive or Negative and General or Differentiated Effect? Correlation between Parental Involvement and Student Achievement. Education Sciences 14: 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Brian K., Joseph E. Olsen, and Shobha C. Shagle. 1994. Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development 65: 1120–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, Diana. 1993. The average expectable environment is not good enough: A response to Scarr. Child Development 64: 1299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley-Geist, Jill C., and Julie B. Olson-Buchanan. 2014. Helicopter parents: An examination of the correlates of over-parenting of college students. Education Training 56: 314–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, Tom, and Terri LeMoyne. 2020. Helicopter Parenting and the Moderating Impact of Gender for University Students with ADHD. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 67: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Tricia J., Chris Segrin, and Kristen L. Farris. 2018. Young Adult and Parent Perceptions of Facilitation: Associations with Overparenting, Family Functioning, and Student Adjustment. Journal of Family Communication 18: 233–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Viktoria M., Andrea P. Francis, and Mareike B. Wieth. 2021. The Relationship Between Helicopter Parenting and Fear of Negative Evaluation in College Students. Journal of Child and Family Studies 30: 1910–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Stephanie. 2018. Scoping Reviews and Systematic Reviews: Is It an Either/Or Question? Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 502–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, Bobby Ho-Hong, Yuan Hua Li, and Tiffany Ting Chen. 2023. Helicopter parenting contributes to school burnout via self-Control in late adolescence: A longitudinal study. Current Psychology 42: 29699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Amy. 2011. Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother. Johannesburg: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, Foster, and Jim Fay. 2020. Parenting with Love and Logic: Teaching Children Responsibility. Colorado Springs: NavPress Publishing Group. Available online: https://files.tyndale.com/thpdata/firstchapters/978-1-63146-906-0.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Csák, Zsolt. 2023. Types of Fathers’ Home–based and School–based Involvement in a Hungarian Interview Study. Central European Journal of Educational Research 5: 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csók, Cintia, and Gabriella Pusztai. 2022. Parents’ and Teachers’ Expectations of School Social Workers. Social Sciences 11: 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Ming, Peipei Hong, and Chengfei Jiao. 2022. Overparenting and Emerging Adult Development: A Systematic Review. Emerging Adulthood 10: 1076–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, Beáta Andrea, Tímea Szűcs, Regina Sávai-Átyin, Anett Hrabéczy, Karolina Eszter Kovács, Gabriella Ridzig, Dávid Kis, Katinka Bacskai, and Gabriella Pusztai. 2024. Narrowing the Inclusion Gap—Teachers and Parents around SEN Students. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, Nancy, and Laurence Steinberg. 1993. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin 113: 487–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlow, Veronica, Jill M. Norvilitis, and Pamela Schuetze. 2017. The Relationship between Helicopter Parenting and Adjustment to College. Journal of Child and Family Studies 26: 2291–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2000. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11: 227–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrance Hall, Elizabeth, Samantha J. Shebib, and Kristina M. Scharp. 2021. The Mediating Role of Helicopter Parenting in the Relationship between Family Communication Patterns and Resilience in First-semester College Students. Journal of Family Communication 21: 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerman, Karen L., Yen-Pi Cheng, Eric D. Wesselmann, Steven Zarit, Frank Fürstenberg, and Kira S. Birditt. 2012. Helicopter parents and landing pad kids: Intense parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family 74: 880–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Kathryn L., Eric E. Pierson, Kristie L. Speirs Neumeister, and William Holmes Finch. 2020. Overparenting and Perfectionistic Concerns Predict Academic Entitlement in Young Adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies 29: 348–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Wen, Yaxion Hou, Larry J. Nelson, Yongqi Xu, and Lingdan Meng. 2024. Helicopter Parenting and Chinese University Students’ Adjustment: The Mediation of Autonomy and Moderation of the Sense of Entitlement. Journal of Adult Development 32: 131–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garst, Barry A., Ryan J. Gagnon, and Garrett A. Stone. 2020. “The Credit Card or the Taxi”: A Qualitative Investigation of Parent Involvement in Indoor Competition Climbing. Leisure Sciences 42: 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, Kenneth R. 2015. Raising Kids to Thrive: Balancing Love with Expectations and Protection with Trust. Itasca: American Academy of Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Shelomi B., and Jacqueline K. Deuling. 2019. Family influence mediates the relation between helicopter-parenting and millennial work attitudes. Journal of Managerial Psychology 34: 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Ya-Jiuan, Jong-Chao Hong, Jian-Hong Ye, Po-Hsi Chen, Liang-Ping Ma, and Yu-Ju Chang Lee. 2022. Effects of Helicopter Parenting on Tutoring Engagement and Continued Attendance at Cram Schools. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 880894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Jon-Chao, Ming-Yueh Hwang, Jen-Chun Kuo, and Wei-Yeh Hsu. 2015. Parental monitoring and helicopter parenting relevant to vocational student’s procrastination and self-regulated learning. Learning and Individual Differences 42: 139–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Peipei, and Ming Cui. 2023. Discrepancies in Parent-Adolescent Educational and Career Expectations and Overparenting. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 41: 435–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Jackson M., Bonnie C. Nicholson, and Steven R. Chesnut. 2019. Relationships between positive parenting, overparenting, grit, and academic success. Journal of College Student Development 60: 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Woosang, and Eunjoo Jung. 2021. Parenting Practices, Parent–Child Relationship, and Perceived Academic Control in College Students. Journal of Adult Development 28: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Woosang, Eunjoo Jung, Narges Hadi, Maya Shaffer, and Kwangman Ko. 2024. Typologies of helicopter parenting and parental affection: Associations with emerging adults’ academic outcomes. Current Psychology 43: 19304–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Chengfei, Ming Cui, and Frank D. Fincham. 2024. Predicting Changes in Helicopter Parenting, Fear Of Missing Out (FOMO), and Social Anxiety in College Students. Journal of Adult Development 32: 120–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Jian, and Chris Segrin. 2023. Moderating the Association Between Overparenting and Mental Health: Open Family Communication and Emerging Adult Children’s Trait Autonomy. Journal of Child and Family Studies 32: 652–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Eunjoo, Woosang Hwang, Seonghee Kim, Hyelim Sin, Yue Zhang, and Zhenqiang Zhao. 2019. Relationships Among Helicopter Parenting, Self-Efficacy, and Academic Outcome in American and South Korean College Students. Journal of Family Issues 40: 2849–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, Zsófia, Valéria Markos, Elek Fazekas, Zsuzsanna Hajnalka Fényes, and Gabriella Pusztai. 2024. “Won’t be enough to invite parents to school events”: Results of a systematic literature review of parental volunteering. Ricerche Di Pedagogia E Didattica. Journal of Theories and Research in Education 19: 133–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kömürcü-Akik, Burcu, and Cansu Alsancak-Akbulut. 2023. Assessing the psychometric properties of mother and father forms of the helicopter parenting behaviors questionnaire in a Turkish sample. Current Psychology 42: 2980–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Kyong-Ah, Gyesook Yoo, and Jennie C. De Gagne. 2017. Does Culture Matter? A Qualitative Inquiry of Helicopter Parenting in Korean American College Students. Journal of Child and Family Studies 26: 1979–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, Joshua E., and Sean T. Lyons. 2022. Helicopter parenting during emerging adulthood: Consequences for career identity and adaptability. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 886979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMoyne, Terri, and Tom Buchanan. 2011. Does “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociological Spectrum 31: 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Lu, Xiangping Liu, Xin Ma, Zijian Yao, Linpu Feng, and Long Huang. 2024. The association between helicopter parenting and college freshmen’s depression: Insights from a cross-sectional study. Current Psychology 43: 19446–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Judith Y., David J. Kavanagh, and Marilyn A. Campbell. 2016. Overparenting and Homework: The Student’s Task, but Everyone’s Responsibility. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools 26: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, Judith Y., Marilyn A. Campbell, and David Kavanagh. 2012. Can a parent do too much for their child? An examination by parenting professionals of the concept of overparenting. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling 22: 249–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, Hayley, Ming Cui, Jeffery W. Allen, Frank D. Fincham, and Ross W. May. 2020. Helicopter parenting and female university students’ anxiety: Does parents’ gender matter? Family Relationships and Societies 9: 417–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Xiao Qing, and Shue Ling Chong. 2023. Helicopter Parenting and Resilience Among Malaysian Chinese University Students: The Mediating Role of Fear of Negative Evaluation. Journal of Adult Development 31: 316–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbe, Aaron M., Kathryn J. Mancini, Elizabeh J. Kiel, Brooke R. Spangler, Julie L. Semlak, and Lauren. M. Fussner. 2018. Dimensionality of Helicopter Parenting and Relations to Emotional, Decision-Making, and Academic Functioning in Emerging Adults. Assessment 25: 841–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukianoff, Greg, and Jonathan Haidt. 2018. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting up a Generation for Failure. New York: Penguin UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lythcott-Haims, Julie. 2015. The Four Cultural Shifts That Led to the Rise of the Helicopter Parent. Business Insider. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/the-rise-of-the-helicopter-parent-2015-7?r=USandIR=T (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- McGinley, Meredith, and Alexandra N. Davis. 2021. Helicopter Parenting and Drinking Outcomes Among College Students: The Moderating Role of Family Income. Journal of Adult Development 28: 221–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, Elizabeth A., and Eva M. Pomerantz. 2010. Ability mindsets influence the quality of mothers’ involvement in children’s learning: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology 46: 1354–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odenweller, Kelly G., Melanie Booth-Butterfield, and Keith Weber. 2014. Investigating Helicopter Parenting, Family Environments, and Relational Outcomes for Millennials. Communication Studies 65: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, Laura M., and Larry J. Nelson. 2012. Black hawk down?: Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence 35: 1177–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabella Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, and Cynthia D. Mulrow. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, Gabriella, Zsuzsanna Demeter-Karászi, Éva Csonka, Ádám Bencze, Enikő Major, Edit Szilágyi, and Katinka Bacskai. 2024. Patterns of parental involvement in schools of religious communities. A systematic review. British Journal of Religious Education 46: 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rote, Wendy M., Melanie Olmo, Lovia Feliscar, Marc M. Jambon, Courtney L. Ball, and Judith G. Smetana. 2020. Helicopter Parenting and Perceived Overcontrol by Emerging Adults: A Family-Level Profile Analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies 29: 3153–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Holly H., and Miriam Liss. 2017. The Effects of Helicopter Parenting on Academic Motivation. Journal of Child and Family Studies 26: 1472–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Holly H., Jennaveve C. Yost, Victoria Power, Emily R. Saldanha, and Erynn Sendrick. 2019. Examining the relationship between helicopter parenting and emerging adults’ mindsets using the consolidated helicopter parenting scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies 28: 1207–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffrin, Holly H., Miriam Liss, Haley Miles-Mclean, Katherine A. Gearly, Mindy J. Erchull, and Taryn Tashner. 2014. Helping or hovering? The effects of helicopter parenting on college students’ well-being. Journal of Child and Family Studies 23: 548–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, Chris, Alesia Woszidlo, Michelle Givertz, Amy Bauer, and Melissa T. Murphy. 2012. The association between overparenting, parent-child communication, and entitlement and adaptive traits in adult children. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies 61: 237–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, Chris, Michelle Givertz, Paulina Swaitkowski, and Neil Montgomery. 2015. Overparenting is associated with child problems and a critical family environment. Journal of Child and Family Studies 24: 470–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, Medhavi, and Tom Buchanan. 2024. Helicopter Parenting of Minor Teenagers in India: Scale Development and Consequences. Family Journal 32: 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Shu, Xi Lin, and Alyssa McElwain. 2023. Parenting, loneliness, and stress in Chinese international students: Do parents still matter from thousands of miles away? Journal of Family Studies 29: 255–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türker, Meltem, and Ferhat Bahçeci. 2024. New Generation Parenting Attitude: Helicopter Parenting. ALANYZIN: Eğitim Bilimleri Eleştriel Inceleme Dergisi 5: 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ingen, Daniel J., Linda L. Moore, Stacy. R. Freiheit, Jesse A. Steinfeldt, David J. Wimer, Adelle D. Knutt, Samantha Scapinello, and Amber Roberts. 2015. Helicopter parenting: The effect of an overbearing caregiving style on peer attachment and self-efficacy. Journal of College Counseling 18: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigdal, Julia Esperås, and Kolbjørn Kallesten Brønnick. 2022. A Systematic Review of “Helicopter Parenting” and Its Relationship with Anxiety and Depression. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 872981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Yixin. 2023. The Influence of Overparenting on College Students’ Career Indecision: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 16: 4569–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Yue, Skyler Thomas Hawk, and Susan Branje. 2023. Educational identity and maternal helicopter parenting: Moderation by the perceptions of environmental threat. Journal of Research on Adolescence 33: 1377–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, Brian J., Joshua N. Hersh, Laura M. Padilla-Walker, and Larry J. Nelson. 2015. “Back Off”! Helicopter Parenting and a Retreat From Marriage Among Emerging Adults. Journal of Family Issues 36: 669–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Wenjie, and Wei Bao. 2024. A study on the influences of parental involvement on the adaptation of college freshmen. Asia Pacific Education Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Wenqing, and Skyler T. Hawk. 2022. Evaluating the Structure and Correlates of Helicopter Parenting in Mainland China. Journal of Child and Family Studies 31: 2436–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2012 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| Journal | Classification by Field of Science | Classification | Number of Articles | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Psychology-Applied Psychology, Clinical Psychology | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Current Psychology | Psychology, Psychology (miscellaneous) | Q1 | 3 |

|

| Education and Training | Business, Management and Accounting-Business, Management and Accounting (miscellaneous). Social Sciences-Education, Life-span and Life-course Studies | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Learning and Individual Differences | Psychology, Developmental and Educational Psychology, Social Psychology. Social Sciences-Education | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Leisure Sciences | Business, Management and Accounting-Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management. Environmental Science-Environmental Science (miscellaneous). Social Sciences-Sociology and Political Science | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Journal of Adolescence | Medicine-Paediatrics, Perinatology and Child Health, Psychiatry and Mental Health. Psychology, Developmental and Educational Psychology, Social Psychology | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Journal of College Student Development | Social sciences-Education | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Journal of Family Communication | Psychology-Social Psychology. Social Sciences-Communication | Q1 | 2 |

|

| Journal of Family Issues | Social Sciences-Social Sciences (miscellaneous) | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Journal of Research on Adolescence | Neuroscience-Behavioural Neuroscience. Psychology, Developmental and Educational Psychology. Social Sciences-Cultural Studies, Social Sciences (miscellaneous) | Q1 | 1 |

|

| Journal of Social and Personal Relationships | Psychology:

| Q1 | 1 |

|

| Family Journal | Psychology:

| Q2 | 2 |

|

| Frontiers in Psychology | Psychology, Psychology (miscellaneous) | Q2 | 2 |

|

| Journal of Adult Development | Psychology, Developmental and Educational Psychology. Experimental and Cognitive Psychology. Social Sciences-Life-span and Life-course Studies | Q2 | 3 |

|

| Journal of Child and Family Studies | Psychology, Developmental and Educational Psychology. Social Sciences-Life-span and Life-course Studies | Q2 | 9 |

|

| Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools | Psychology-Developmental and Educational Psychology, Social Psychology. Social Sciences-Education | Q2 | 1 |

|

| Psychology Research and Behaviour Management | Medicine-Psychiatry and Mental Health. Psychology, Psychology (miscellaneous) | Q2 | 1 |

|

| Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling | - | - | 1 |

|

| Article | Methodological Background | Target Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interview | Questionnaire | Parent | Teacher | Student (Primary or Secondary School) | University Students | Others | |

| Ching et al. (2023) | N = 416 | X | |||||

| Ho et al. (2022) | N = 293 | X | |||||

| Hong et al. (2015) | N = 597 | X | |||||

| Sood and Buchanan (2024) | N = 425 | X | |||||

| Bradley-Geist and Olson-Buchanan (2014) | N = 482 | X | |||||

| Buchanan and LeMoyne (2020) | N = 247 | X | |||||

| Carr et al. (2021) | N = 86 | X | |||||

| Darlow et al. (2017) | N = 294 | X | |||||

| Dorrance Hall et al. (2021) | N = 2253 | X | |||||

| Fletcher et al. (2020) | N = 343 | X | |||||

| Gao et al. (2024) | N = 392 | X | |||||

| Howard et al. (2019) | N = 226 | X | |||||

| Hwang and Jung (2021) | N = 462 | X | |||||

| Hwang et al. (2024) | N = 859 | X | |||||

| Jiao and Segrin (2023) | N = 442 | X | |||||

| Jung et al. (2019) | NUSA = 200 NKorea = 143 | X | |||||

| Kömürcü-Akik and Alsancak-Akbulut (2023) | N = 324 | X | |||||

| Kwon et al. (2017) | N = 40 | X | |||||

| LeBlanc and Lyons (2022) | N = 491 | X | |||||

| Love et al. (2020) | N = 427 | X | |||||

| Low and Chong (2023) | N = 204 | X | |||||

| Luebbe et al. (2018) | N = 377 | X | |||||

| Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012) | N = 438 | X | |||||

| Rote et al. (2020) | N = 282 | X | |||||

| Wang (2023) | N = 743 | X | |||||

| Burke et al. (2018) | N = 302 | X | X | ||||

| Garst et al. (2020) | N = 160 | X | |||||

| Hong and Cui (2023) | Npair = 122 | X | X | ||||

| Locke et al. (2012) | N = 128 | X | X | X | |||

| Locke et al. (2016) | N = 866 | X | |||||

| Schiffrin and Liss (2017) | Nmother = 121 Nstudent = 192 | X | X | ||||

| Zong and Hawk (2022) | NT1 = 433 NT2 = 461 NT3mother = 248 NT3student = 408 | X | X | ||||

| Wang et al. (2023) | N = 349 | X | X | ||||

| Article | Topic |

|---|---|

| LeBlanc and Lyons (2022) | Career choice |

| Wang (2023) | |

| Hwang and Jung (2021) | Parent–child relationship |

| Rote et al. (2020) | |

| Dorrance Hall et al. (2021) | Communication |

| Jiao and Segrin (2023) | |

| Carr et al. (2021) | FNE-fear of negative evaluation |

| Low and Chong (2023) | |

| Buchanan and LeMoyne (2020) | Self-efficacy |

| Darlow et al. (2017) | |

| Jung et al. (2019) | Academic performance |

| Luebbe et al. (2018) | |

| Love et al. (2020) | |

| Hwang et al. (2024) | Academic achievement, self-efficacy |

| Fletcher et al. (2020) | Eligibility |

| Gao et al. (2024) | |

| Bradley-Geist and Olson-Buchanan (2014) | Demographic data |

| Kwon et al. (2017) | |

| Howard et al. (2019) | Courage, academic success |

| Kömürcü-Akik and Alsancak-Akbulut (2023) | Validation |

| Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012) | Parental control |

| Instrument | Article |

|---|---|

| Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012)—Helicopter Parenting Scale | Gao et al. (2024) |

| Hwang and Jung (2021) | |

| Hwang et al. (2024) | |

| Jung et al. (2019) | |

| Low and Chong (2023) | |

| Padilla-Walker and Nelson (2012) | |

| Rote et al. (2020) | |

| Odenweller et al. (2014)—Helicopter Parenting Instrument | Dorrance Hall et al. (2021) |

| Howard et al. (2019) | |

| LeBlanc and Lyons (2022) | |

| Bradley-Geist and Olson-Buchanan (2014)—5-item overparenting scale | Bradley-Geist and Olson-Buchanan (2014) |

| Love et al. (2020) | |

| Wang (2023) | |

| LeMoyne and Buchanan (2011)—HPS-Helicopter Parenting Scale | Buchanan and LeMoyne (2020) |

| Darlow et al. (2017) | |

| Schiffrin et al. (2014)—(HPBQ) Helicopter parenting behaviour questionnaire | Carr et al. (2021) |

| Kömürcü-Akik and Alsancak-Akbulut (2023) | |

| 10-item Hovering Parents Scale | Fletcher et al. (2020) |

| Schiffrin et al. (2019)—10-item Consolidated Helicopter Parenting Scale | Jiao and Segrin (2023) |

| Interview | Kwon et al. (2017) |

| Self-developed | Luebbe et al. (2018) |

| Instrument | Article |

|---|---|

| Segrin et al. (2012, 2015)—Overparenting Scale | Burke et al. (2018) |

| Interview | Garst et al. (2020) |

| Bradley-Geist and Olson-Buchanan (2014)—5-item Overparenting Scale | Hong and Cui (2023) |

| No specific measurement tool is mentioned. | Locke et al. (2012) |

| Locke et al. (2016)—Locke Parenting Scale | Locke et al. (2016) |

| Schiffrin et al. (2014)—Helicopter Parent Scale (9 item) | Schiffrin and Liss (2017) |

| Zong and Hawk (2022) | |

| Odenweller et al. (2014)—Helicopter Parenting Instrument | Wang et al. (2023) |

| Instrument | Article |

|---|---|

| Odenweller et al. (2014)—Helicopter Parenting Instrument | Ching et al. (2023) |

| Hong et al. (2015)—Helicopter parenting attitudes | Ho et al. (2022) |

| Adapted questionnaire 1 | Hong et al. (2015) |

| Own development, compared to LeMoyne and Buchanan’s (2011) HPS scale. | Sood and Buchanan (2024) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kocsis, Z.; Kas, D.; Pusztai, G. Wings or Handcuffs? The Dilemmas of Helicopter Parenting Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100621

Kocsis Z, Kas D, Pusztai G. Wings or Handcuffs? The Dilemmas of Helicopter Parenting Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):621. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100621

Chicago/Turabian StyleKocsis, Zsófia, Dorka Kas, and Gabriella Pusztai. 2025. "Wings or Handcuffs? The Dilemmas of Helicopter Parenting Based on a Systematic Literature Review" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100621

APA StyleKocsis, Z., Kas, D., & Pusztai, G. (2025). Wings or Handcuffs? The Dilemmas of Helicopter Parenting Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Social Sciences, 14(10), 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100621