1. Introduction

Underemployment has emerged as a critical dimension of labour market disadvantage in Australia, encompassing both insufficient working hours and the underutilisation of skills. Although precarious work and underemployment are conceptually distinct, they often overlap in practice. Many underemployed workers face precarious conditions (

Kalleberg 2009;

Lee et al. 2025). Underemployment is not only about hours. It also arises when workers’ skills do not match their job demands. These mismatches create both economic vulnerability and psychosocial stress (

Pratap et al. 2021).

The health impacts of underemployment are similar to those of precarious work more broadly. Recent studies show that underemployment is multidimensional and socially embedded, with major consequences for both mental health and equity. A recent systematic review found that employment insecurity harms workplace wellbeing, mental health, and overall health (

Jaydarifard et al. 2023). Employment insecurity, whether due to unstable contracts or insufficient hours, has been linked to poorer mental health, increased stress, and reduced overall wellbeing (

Quinlan and Rawling 2025).

Underemployment also undermines self-esteem and fuels feelings of career stagnation (

Reitz et al. 2022). These effects can worsen health and wellbeing, pointing to a two-way relationship between precarity and health disadvantage.

Allan et al. (

2024) identified three employment profiles: fully employed, stable underemployed, and precarious workers. Their study showed that precarious workers had the poorest mental health and job quality. This finding reinforces the need to move beyond simple employed/unemployed categories.

Churchill et al. (

2025) studied how different forms of underemployment—such as underpayment, status mismatch, and temporary work—affect psychological distress over time. They found that involuntary temporary work consistently predicted worsening mental health. The effects varied by gender, age, education, and social class. These findings show that underemployment is not just a temporary labour market issue. It is a social determinant of health. Addressing it requires gender-sensitive and equity-focused policies that link employment services with mental health care, caregiving support, and income security. Two dimensions—care burden and financial vulnerability—are particularly salient in shaping underemployment experiences. Many underemployed Australians, especially women, balance paid work with unpaid caregiving, leading to time stress, reduced job satisfaction, and elevated psychological distress. Standard labour force metrics often overlook these dynamics, masking the intersection of care responsibilities and employment precarity (

Lee and Kang 2024). Similarly, financial instability resulting from irregular hours and low income contributes to material deprivation and mediates the mental health effects of underemployment.

2. Hidden Groups Within the Underemployed Population

Recent studies have sought to unpack the hidden profiles within the underemployed population.

Allan et al. (

2024) used latent profile analysis to distinguish between fully employed, stable underemployed, and precarious workers, finding that precarious workers experienced the poorest mental health and job quality.

Churchill et al. (

2025) extended this work by conducting a longitudinal study of subjective underemployment constructs—including underpayment, status mismatch, involuntary temporary work, poverty-wage employment, and overqualification—revealing that involuntary temporary work was the only construct that consistently predicted worsening mental health over time. Their findings also highlighted group differences shaped by gender, age, education level, and subjective social class.

Despite this growing recognition of underemployment’s complexity, traditional labour force statistics continue to treat the underemployed as a single, homogenous category—typically defined as those wanting and available for more hours. This approach obscures the diversity of lived experiences and masks critical differences in the types and combinations of barriers individuals face. Disaggregating this group into differentiated, actionable subgroups is essential for designing effective policy responses.

To address this gap, our study employs latent class analysis (LCA) to uncover distinct subgroups within the underemployed population. LCA provides the methodological leverage to move beyond “one-size-fits-all” classifications and reveal subpopulations shaped by unique constellations of care responsibilities, financial stress, and health vulnerabilities (

Collins and Lanza 2009). This precision enables policymakers to target interventions not simply at “the underemployed,” but also at those most disadvantaged by the interaction of labour market structures and social determinants.

The

OECD (

2018) report on the Australian underemployed population provided an important foundation for understanding groups of people excluded from stable employment, identifying seven profiles characterised by overlapping disadvantages such as low education, skills mismatch, work history, poor health, and limited work experience. While the OECD study points to the diverse types and experiences of joblessness, our study builds on previous studies of class by examining more closely the nuanced social and health dimensions so that we can uncover critical but often hidden mechanisms that perpetuate Australian workforce exclusion.

Recognising underemployment as a dimension of precarious life has important policy implications. It calls for integrated, person-centred interventions that address not only employment barriers but also the social determinants that perpetuate exclusion. This includes mental health services, caregiving infrastructure, income support, and culturally responsive employment programs. By addressing the lived realities of precariousness, policy can move beyond narrow labour market metrics and toward more holistic, equitable solutions.

In particular, embedding financial vulnerability into the latent class model allows us to capture the everyday realities of underemployed Australians—struggling to cover rent, manage medical costs, or afford reliable transport. These experiences reveal how underemployment interacts with broader social determinants of health and wellbeing. The hardship of underemployment cannot be fully understood through labour market status alone; it is inseparable from the financial insecurity shaping daily life.

Similarly, care responsibilities—especially among women—emerge as a critical axis of underemployment. Many underemployed Australians balance paid work with unpaid caregiving, leading to time stress, reduced job satisfaction, and elevated psychological distress (

Lee and Kang 2024). Standard labour force metrics often overlook these dynamics, masking the intersection of care and employment precarity.

By centring precarious lives as indicators to understand diverse experiences of the underemployed population, this study suggests that policymakers design interventions that are more responsive, equitable, and grounded in the realities of those most affected. This approach aligns with broader movements toward participatory governance and social justice, reinforcing the principle that those closest to the problem should be closest to the solutions. Based on prior research, we hypothesised that (H1) care burden is a core latent dimension of underemployment, (H2) economic insecurity represents a second defining dimension, and (H3) a distinct subgroup characterised by mental health and social isolation exists.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

This study draws on data from the 2022 wave of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The survey gathers detailed information on a broad range of personal and household characteristics, including income and its sources, labour force and employment status, hours worked, industry and occupation, trade union membership, tenure with the current employer, employer characteristics, work history, educational attainment, family circumstances, health status, country of birth, and those born outside Australia. Because this study focuses on typological subgroup identification rather than population-level estimates, clustering, stratification, and weights were not applied in mixture estimation.

The analysis focused specifically on individuals identified as underemployed workers. ”Underemployed” was identified as people who normally undertake paid work of less than 35 h per week who would prefer to work more hours (

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2023;

Lee et al. 2025). After applying exclusion criteria and addressing missing data, the analytical sample comprised 989 observations of the underemployed. The final sample size used for latent class analysis (LCA) ranged from approximately 94 to 571 across subgroups, allowing for subgroup-specific modelling and robust identification of latent profiles.

3.2. Variables

This latent class analysis (LCA) was designed to capture the precarious lives of those experiencing underemployment that goes beyond conventional labour force statistics. Their inclusion ensures that the LCA identifies subgroups that reflect the lived realities of workers facing overlapping burdens of care, health, educational, cultural, and financial disadvantage. Each variable represents a latent construct that has been highlighted in literature as central to understanding Australian labour market disadvantage and health inequities. Lagged proxies for care burden was included from Wave 21 (2021) to reduce simultaneity bias when examining 2022 outcomes.

Care burden indicators used With child, and care_for21 measures other care responsibilities, reflecting how unpaid care constrains the availability and flexibility of paid employment.

Socioeconomic indicators encompassed educational attainment (Year 12 or below) and household income in the lowest 20% (pcinc_lower20). These variables represent accumulated structural disadvantages in education and income, which have well-established links to underemployment and vulnerability to precarious work.

Health-related indicators included self-rated physical and mental health below the population median (physical_d50 and mental_d50). These measures capture health barriers that limit employability and sustain underemployed status, while also reflecting the reciprocal effects of precarious work on wellbeing.

The social capital indicator was proxied by 4 items of social capital question (nohelp).

- -

I need help from other people but cannot get it.

- -

I do not have anyone that I can confide in.

- -

I have no one to lean on in times of trouble.

- -

I cannot find anyone when I need someone.

The mean score of the four items was calculated, and a binary variable (dummy) was created by categorising the lower half as indicating lower social capital. Internal consistency was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.84), supporting use of a composite social capital index.

Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Background were proxied by citizenship status and other language spoken at home (otherlang). CALD status has been associated with systemic disadvantages in accessing secure work, particularly due to discrimination and credential recognition issues.

Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA)

Income: Lowest 20% of per capita income.

The risk variable is a composite dummy variable, constructed from the above seven questions, coded 1 if respondents endorsed any item and 0 otherwise.

3.3. Analysis

This study draws on data from the 2022 wave of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey and employed latent class analysis (LCA) to identify distinct subgroups within the underemployed population in Australia. This is a finite mixture modelling study, estimated in Stata 17 using gsem mixture models with Bernoulli logit links for binary indicators and identity links for continuous indicators. For covariate comparisons, we implemented the bias-corrected three-step BCH approach, which corrects for classification error. To capture the multidimensional nature of underemployment, this study included a range of theoretically informed indicators as identified above—such educational attainment, caregiving responsibilities, financial stress, CALD identity, and access to social support—with particular attention to care responsibilities and financial insecurity, which are especially influential in shaping the lived experience of underemployment.

Model selection involved estimating a series of LCA models with increasing numbers of classes. Fit indices—including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and entropy—were used to determine the optimal number of classes, alongside theoretical interpretability and classification quality. While more parsimonious models with fewer classes were considered, the four-class solution was selected because it offered superior interpretability and captured meaningful groupings that would have been obscured in simpler specifications. Once the best-fitting model was identified, class membership probabilities were used to describe the defining characteristics of each subgroup.

3.3.1. Model Selection

Model selection was based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), sample size-adjusted BIC (SSA-BIC), entropy, class sizes, and average posterior probabilities (AvePPs). The four-class solution was selected as the best balance of statistical fit and substantive interpretability, despite one smaller class exhibiting lower classification certainty (AvePP = 0.52).

3.3.2. Covariate Associations (R3STEP Correction)

To examine predictors of class membership, we employed the bias-corrected three-step (R3STEP) approach (

Vermunt 2022). In this procedure, the latent class measurement model is estimated first, followed by multinomial logistic regression of class membership on covariates. Relative risk ratios (RRRs) and 95% confidence intervals were estimated with robust standard errors clustered at the individual level (

Supplementary Table S1).

3.3.3. Distal Outcomes (BCH Correction)

Distal continuous outcomes on

social functioning were compared across classes using the bias-corrected three-step (BCH) method (

Bolck et al. 2004). BCH generates class-specific weights that preserve the latent class measurement model and provide unbiased estimates of class differences. Class-specific means and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals were estimated, and Wald tests assessed pairwise differences between classes (

Supplementary Table S2).

3.3.4. Employment Conditions (ANOVA and F-Tests)

To characterise employment conditions across classes, both continuous and categorical outcomes were analysed. For continuous variables (wages), class means were compared using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise tests; F-statistics are reported. For categorical outcomes (paid holiday leave, paid sick leave), and contract types (permanent, fixed-term, casual) linear probability regressions were used. F-tests were used to evaluate overall between-class differences.

4. Results

We begin by presenting descriptive statistics for the full sample, followed by the latent class classification process. We then outline the resulting class profiles on socio-demographic and health indicators, before turning to differences in employment conditions.

4.1. Descriptive

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the underemployed sample. On average, individuals were 38.6 years old (SD = 10.6), with ages ranging from 17 to 75. The majority of respondents were female (88%), reflecting the gendered nature of underemployment in this sample.

In terms of education, approximately 24% had completed only up to Year 12 or below, while 7% were currently enrolled in an education or training program. Around 9% of respondents reported speaking a language other than English at home (CALD background), indicating a relatively small share of culturally and linguistically diverse participants.

Family and household characteristics show that a large proportion were married (81%), and the average child ratio (children under 15 per adult) was 0.36, suggesting that many households included dependent children. Roughly about 10% identified as caregivers within their household.

Social capital indicators reveal a mean score of 2.29 on the “nohelp” index (range: 1–7), suggesting moderate levels of perceived social support, with higher scores reflecting weaker social networks. The average SEIFA index score was 5.80 (SD = 2.80), close to the midpoint of the 1–10 scale, implying a spread of respondents across both advantaged and disadvantaged areas. The risk index indicates that roughly one in five participants reported high perceptions of risk in their employment situation.

4.2. Model Selection

Model selection involved estimating a series of LCA models with increasing numbers of classes. Fit indices, described in

Table 2—including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and entropy—were used to determine the optimal number of classes, alongside theoretical interpretability and classification quality. Once the best-fitting model was identified, class membership probabilities were used to describe the defining characteristics of each subgroup. Models with more than four classes were also explored. A five-class specification was estimated but did not converge to a stable solution despite multiple runs with 500 random starts and 50 final optimisations. The instability and poorly differentiated groups suggested overfitting with sparse cells. For these reasons, the four-class model was retained as the most appropriate balance between model fit, parsimony, and theoretical interpretability.

Model fit indices and substantive interpretability were both considered in selecting the final latent class solution. As shown in the model comparison table, the four-class model achieved the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC = 7622.8) among the tested solutions, indicating superior overall fit relative to the two- and three-class models. While the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was slightly higher for the four-class model (7833.4) compared to the three-class model (7794.7), this was expected given the BIC’s stronger penalty for model complexity. In this case, the modest increase in BIC was outweighed by the substantial reduction in AIC and the theoretical interpretability of the additional class.

Entropy, which reflects classification quality, was highest in the three-class solution (0.675). However, the four-class model still achieved moderate entropy (0.602), indicating reasonably distinct class separation. We acknowledge that this indicates some uncertainty in classification and interpret our findings cautiously. Importantly, the four-class model offered greater conceptual differentiation by identifying a subgroup characterised by high mental health risk, lack of social support, and financial vulnerability—dimensions not as clearly delineated in the three-class solution. This added granularity strengthens the policy relevance of the findings, as interventions can be better targeted to distinct at-risk groups. The average posterior probability of class assignment was 0.80, indicating adequate model fit.

4.2.1. Class Quality

The four-class solution produced a substantively interpretable structure but showed variation in classification precision (

Table 3). Classes 2 (57.8% of the sample) and 3 (16.8%) had strong average posterior probabilities (AvePP = 0.82 and 0.77, respectively), while Class 1 (15.8%) was moderate (AvePP = 0.68). Class 4 (9.6%) had weaker classification quality (AvePP = 0.52), suggesting a more diffuse subgroup.

4.2.2. Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the stability of the four-class solution, we compared it with a three-class model. The three-class model merged the subgroup represented in Class 4 into a broader class with mixed profiles, obscuring the distinct pattern of high disadvantages observed in the four-class model. Although Class 4 was the smallest group (9.6% of respondents) and had lower classification certainty (AvePP = 0.52), the substantive distinctiveness of this group justified its retention. Similar approaches are recommended in the literature, where retaining smaller classes is valuable for identifying at-risk or marginalised populations (

Nylund et al. 2007;

Collins and Lanza 2009).

Multinomial regression with the R3STEP correction was used to assess external covariate associations with class membership (

Supplementary Table S1). Distal outcomes were then examined using the bias-corrected three-step (BCH) approach, which adjusts for classification error while preserving the measurement model. Robust standard errors were clustered at the individual level. Full covariate estimates are presented in

Supplementary Table S2.

4.3. Classification

Latent class analysis identified a four-class solution that best captured the different groups among the underemployed, with class proportions of 15.8%, 57.8%, 16.8%, and 9.6%, respectively. Each class reflected distinctive patterns of disadvantage related to caregiving, education, financial vulnerability, mental health, and social support.

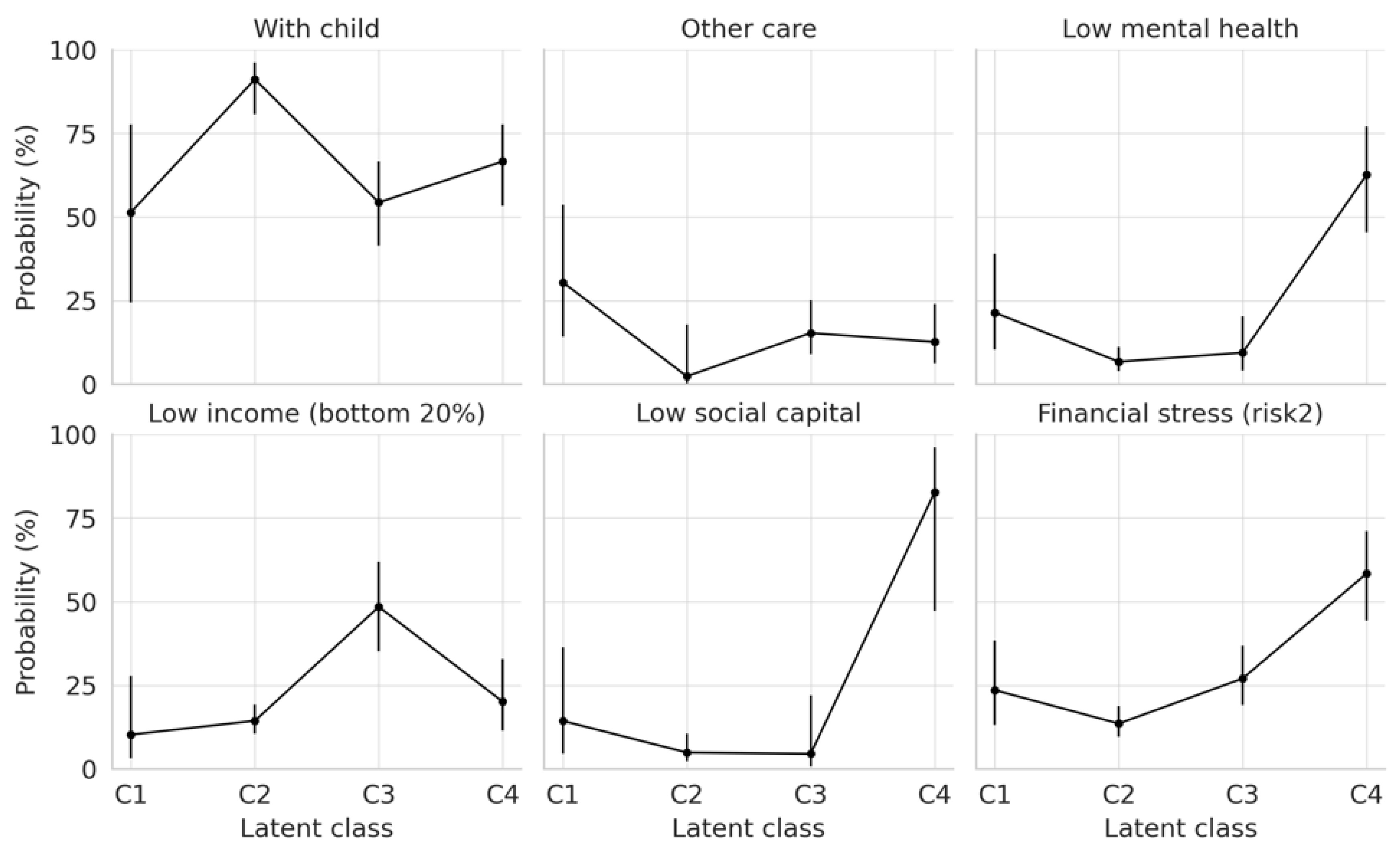

Table 4 and

Figure 1 show the item response probabilities for the four latent class analysis.

Panel A highlights the sharp contrasts across classes in education, care responsibilities, and social vulnerability. Notably, Class 3 has the highest concentration of households in the lowest 20% of per capita income (48%), while Class 4 has the highest prevalence of poor mental health (63%) and low social capital (83%). Panel B shows that financial stress is greatest in Class 4 (0.58) and lowest in Class 2 (0.14). This indicates that income poverty and financial stress are related but not identical: Class 3 is most income-poor, while Class 4 experiences the highest subjective/material financial stress.

Class 1: Dual-care burden carers with high CALD population (15.8%)

The first class is characterised by a moderate probability of having children (0.51) and substantial caregiving responsibilities (0.30). Members of this group are likely to have completed Year 12 (0.08) and display relatively poor mental health (0.21). They also report elevated risk exposure (0.24), highlighting the dual burden of family care responsibilities. This profile suggests a group of underemployed individuals juggling unpaid care duties with constrained opportunities for workforce re-entry.

Class 2: Parents with Children (57.8%)

The second and largest class, representing over half of the sample, is distinguished by very high rates of having children (0.91) and the heaviest childcare responsibilities across the classes. Educational attainment is high, with only 7% having attained up to Year 12 or below. Although financial vulnerability is somewhat lower than in Class 3, their caregiving burden restricts labour force participation and contributes to the underemployed status. This class exemplifies the “core” underemployed population, where childcare duties dominate life circumstances.

Class 3: Financially Strained Undereducated (16.8%)

The third class is the least educated group, with the lowest level of education attainment, as 87% of them had completed only up to Year 12 or below (0.87), yet is defined by acute economic insecurity, with nearly half falling below the lowest household income threshold. While caregiving demands are relatively lower, members of this group report elevated risk exposure (0.27), which indicates heightened vulnerability to downward social and economic mobility. This subgroup reflects undereducated and financially precarious underemployed individuals, underscoring the centrality of material deprivation in shaping exclusion.

Class 4: Socially Isolated, Poor Mental Health (9.6%)

The fourth and smallest class stands out as the most vulnerable group for its severe mental health disadvantage (0.63) and extreme lack of social support (0.83). More than half also report significant risk exposure (0.58). Unlike Classes 1 and 2, caregiving burdens are not as prominent, suggesting that their exclusion stems more from psychological distress, social isolation, and compounding vulnerabilities than from family care responsibilities. This group constitutes the most marginalised underemployed workers, pointing to urgent needs for mental health and community-based interventions.

Together, these findings highlight that even though Class 2 (“childcare burden”) reflects the dominant stereotype of female underemployment linked to caregiving, the female majority across all classes indicates that women’s underemployment extends well beyond childcare responsibilities alone. While caregiving is central for the majority (Classes 1 and 2), financial vulnerability (Class 3) and social isolation with poor mental health (Class 4) also emerge as distinctive drivers. These insights underscore the need for differentiated policy responses that account for the varied and intersecting disadvantages within the hidden workforce. These results provide empirical support for our hypotheses: H1—care burden is central (Classes 1 and 2), H2—economic insecurity is defining (Class 3), and H3—a distinct mental health/social isolation subgroup exists (Class 4).

4.4. Covariate Predictors of Class Membership (R3STEP)

In the R3STEP analysis, age, sex, marital status, and long-term health condition were included as external covariates. Compared to Class 2, membership in Class 3 was associated with slightly older age (RRR = 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.02). Class 4 was distinguished by a higher likelihood of having a long-term health condition (RRR = 1.75, 95% CI 1.26–2.43). No other associations were statistically significant. These findings suggest that the four-class solution captures latent profiles not reducible to demographics, while also aligning with known health inequalities, thereby supporting the interpretability and validity of the model.

4.5. Social Functioning Differences (BCH Test)

The distal outcome comparisons using the BCH method indicated clear and robust differences in mean social wellbeing across classes (

Supplementary Table S2). Relative to Class 1 (mean = 76.3), Class 2 (+10.6 points,

p < 0.001) and Class 3 (+7.8,

p = 0.012) reported significantly higher wellbeing. By contrast, Class 4 reported markedly lower wellbeing (–18.3,

p < 0.001). These findings suggest that Classes 2 and 3 are well-defined subgroups with more favourable wellbeing outcomes, while Class 4 represents a smaller but highly disadvantaged group. Although classification certainty was weaker for Class 4 (AvePP = 0.52), the size and robustness of the wellbeing deficit support its substantive validity as a distinct subgroup.

Supplementary Table S2 details class-specific means estimated using the bias-corrected three-step (BCH) method.

4.6. Employment Conditions Gradient

We next examined how these class profiles translate into employment conditions. Employment conditions across the four latent classes of underemployed Australians reveal a gradient of job quality, security, and compensation, shaped by intersecting care responsibilities and structural barriers.

Table 5 illustrates the item response probabilities for the four latent class analysis on employment conditions.

The average weekly wages differed significantly across classes (F(398, 5) = 24.65, p < 0.001). Class 2 reported the highest average wage (AUD 938.1), well above Class 1 (AUD 756.6), Class 3 (AUD 563.4), and Class 4 (AUD 576.7). This suggests that members of Class 2, despite being underemployed, retained stronger earnings capacity, whereas Classes 3 and 4 were markedly disadvantaged.

For entitlements, both paid holiday leave and paid sick leave varied significantly by class (F(398, 5) = 5.78, p < 0.001; F(398, 3) = 5.47, p < 0.001). Class 2 again stood out, with around two-thirds receiving holiday (66.0%) and sick leave (66.5%), compared with fewer than one-quarter of Class 3 members (22.4% and 23.1%, respectively). Classes 1 and 4 showed intermediate levels of entitlement access.

For contract type, permanent employment was most common in Class 2 (68.0%) and least common in Class 3 (27.9%), while casual contracts were concentrated in Class 3 (68.1%) and Class 4 (51.9%). In contrast, only 23.4% of Class 2 members were employed casually. Class 1 displayed a mixed profile (51.3% permanent; 41.3% casual). Fixed-term contracts were relatively rare and did not differ significantly across classes (F(384, 7) = 1.07, p = 0.363).

Together, these patterns underscore the variation in underemployment conditions: Class 2 members occupy a relatively advantaged position, with higher wages and secure contracts, while Class 3 is the most precarious, combining low wages, weak entitlements, and high casualisation. Class 4 also reflects disadvantage, particularly through limited entitlements and high casualisation, though less extreme than Class 3. These employment patterns align with our hypothesised latent dimensions, in which care responsibilities and financial stress operate as key drivers of underemployment and help to validate the distinct profiles observed in Classes 1–4.

5. Discussion

The gender composition of the sample, with nearly nine in ten participants being women, reinforces longstanding evidence that underemployment is a highly gendered labour market phenomenon. This means that underemployed Australians—particularly women—juggle paid work with unpaid caregiving, producing distinct patterns of time stress, reduced job satisfaction, and elevated psychological distress (

Lee et al. 2025). Standard labour force measures only capture the number of hours worked or desired. They miss the intensity and type of caregiving responsibilities that shape people’s daily lives. Recognising care work reveals how it intersects with employment precarity, creating hidden inequities in health and wellbeing. This makes care burden a powerful lens for uncovering subgroups whose employment outcomes cannot be explained by hours-based definitions alone.

Importantly, however, the class profiles show that female underemployment cannot be reduced to childcare burden alone: Women were also concentrated in groups marked by economic insecurity, poor health, and social isolation. These factors combine in different ways across individuals. The latent class analysis revealed four distinct groups of underemployed workers, each defined by unique configurations of care responsibilities, health status, education, social support, and financial vulnerability. Our three hypotheses were confirmed: H1—care burden shaped two of the four classes, H2—economic insecurity defined Class 3, and H3—a mental health/social isolation subgroup was identified (Class 4).

Class 1, comprising 15.8% of the sample, represents underemployed individuals with high probabilities of dual care burden. This group highlights the tension between paid work and family responsibilities. The higher representation of CALD backgrounds than other groups may imply that this group faces structural barriers to stable work and a higher risk of labour market marginalisation. Policies should focus on targeted vocational training, recognition of overseas qualifications, and culturally responsive employment services. The dual care burden of this group might be connected with the finding that the CALD population in Australia tends to start care duties for elder members of household earlier in life (

Hussain et al. 2024). Redesigning work to accommodate care within the labour force needs to be progressed further. The papers by

Fuller et al. (

2021) challenge the traditional separation between care and industry, proposing that care should be embedded into the design of work, workplaces, and economic systems. Many underemployed workers are not excluded due to low skills or motivation. Instead, they are constrained by inflexible work structures that ignore caregiving responsibilities. This has direct implications for Australian underemployment and workforce exclusion, particularly for those whose labour market participation is shaped by caregiving responsibilities.

Class 2 forms the majority, encompassing 57.8% of underemployed individuals. Members of this group are comparatively better off in terms of health burdens but still experiencing persistent underemployment. Evidence suggests that parental employment is strongly influenced by the availability of early childhood education and care services (

Wilkins 2006). Policies that promote flexible work arrangements and policy interventions for this class should prioritise family-friendly work arrangements, including subsidised childcare, flexible scheduling, and parental leave reform, and incentivising employer support for working alongside accessible re-skilling programs to parents could enhance labour market engagement for this group.

Class 3, representing 16.8% of the sample, is distinguished by low educational attainment and higher financial strain. Their primary challenge lies in job quality.

Baum and Mitchell (

2010) argue that employability is shaped not only by individual attributes but also by the broader economic context, including access to education and training. Low-income parents may lack the resources to afford educational expenses, face financial pressures requiring them to work, lack access to quality educational opportunities for their children, or struggle with the impacts of unstable living environments (

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2020). It is not surprising that nationally, students from disadvantaged backgrounds—including low SES and other equity groups—have lower university completion rates compared to the national average (

Edwards and McMillan 2015), not to mention health and social risk variables that significantly hinder tertiary completion (

Department of Education 2020). For this class, policy should focus on vocational education, apprenticeships, and wage subsidies that support transitions into more stable and better-paying roles. Career coaching and mentoring programs may also help individuals navigate complex labour markets and build sustainable employment trajectories. Policies that expand access to full-time or secure part-time roles, encourage employer commitments to predictable scheduling, and promote skills development would directly benefit this group by reducing income volatility and preventing future vulnerability.

Class 4, though the smallest, at 9.6%, is the most vulnerable subgroup. It is defined by high prevalence of poor mental health, lack of social support, and financial insecurity, making them particularly at risk of long-term exclusion. Further evidence from the Australian Council of Social Service (

Davidson et al. 2023) shows that single-parent families and people with disabilities are disproportionately affected by poverty (

Australian Council of Social Service 2024). Research has consistently shown that mental health is a critical determinant of employment outcomes, with poor mental health associated with reduced job retention and productivity (

de Oliveira et al. 2023). For this class, employment policy must be integrated with health and social policy, ensuring access to mental health services, disability accommodations, and community-based supports. Addressing transport barriers and strengthening social networks will also be critical to reducing isolation. Our findings delineate a subgroup of underemployed workers characterised by poor mental health and weak social support, and compounding financial stress shows that mental health and social isolation operate as hidden mechanisms that reproduce exclusion from the workforce. Integrated service models that combine mental health care with employment support are essential. Additionally, peer support networks and trauma-informed employment programs can foster resilience and reduce isolation, enabling more meaningful labour market participation.

This finding complicates prototype understandings of underemployment, which often equate it primarily with mothers managing childcare, and instead points to a broader spectrum of disadvantage experienced by women in mid-to-later life. This means a single policy solution will not be effective. Instead, interventions need to be intersectional and tailored to life stage, social context, and health needs. By doing so, policy can move beyond merely addressing job scarcity and go further in recognising caregiving demands and mental health vulnerabilities as central features of hidden worker exclusion.

A major contribution of this study is showing that financial vulnerability is a defining feature of underemployment. Previous frameworks (

OECD 2018) focused mainly on structural barriers such as contract type or skills mismatch. Our analysis shows that financial stress—such as arrears, unpaid bills, and material deprivation—is not just a result of underemployment but also a core part of how it is experienced.

This finding brings the lived experiences of underemployed workers into sharper relief and makes visible the hidden costs that traditional labour force surveys overlook. It also creates an actionable pathway for policy, suggesting that income stabilisation measures, targeted financial relief, and supports to reduce material hardship must be considered alongside employment interventions if the goal is to move people out of precarious work into secure, sustainable livelihoods.

Policies that only promote job search will not improve health if hours remain unstable or insufficient. Effective responses must integrate several levers: stable hours and contracts, financial relief for rent and utilities, access to healthcare and transport, and flexible, predictable work arrangements for carers, especially women. These align with AIHW’s determinants approach and with the Australian literature linking precarious work and job insecurity to health inequalities.

6. Limitation

This study has several limitations. First, although the HILDA survey is based on a clustered and stratified sample, our latent class analysis did not incorporate clustering, stratification, or population weights. This decision reflects our focus on identifying typological patterns of underemployment rather than producing population-representative prevalence estimates. Consequently, the class solution should be interpreted as descriptive of the analytic sample of underemployed respondents (n = 989), not as generalisable proportions for the broader population.

Second, the measure of social capital used in this study was necessarily limited. While it provides a useful proxy, it does not fully capture all dimensions of social capital, such as reciprocity, civic engagement, and collective efficacy. These constraints should be considered when interpreting the findings and their implications. Finally, from a substantive standpoint, the four-class model aligns with existing literature on underemployment and diversity among the underemployed, which highlights the co-existence of multiple disadvantage clusters (e.g., caregiving burden, educational disadvantage, poor health, financial strain). Furthermore, sensitivity analyses and diagnostic tests were conducted to validate the four-class LCA solution. However, the findings for Class 4 should be interpreted with caution due to its small size and only moderate classification certainty (AvePP = 0.52).

7. Conclusions

While traditional labour statistics often treat underemployment as a matter of insufficient working hours, our findings suggest that it is more accurately understood as a reflection of multidimensional vulnerabilities—marked by unstable income, caregiving burdens, mental health challenges, and limited access to support systems. Latent class analysis (LCA) offers a powerful lens through which to examine these complexities, revealing four distinct subgroups within the underemployed population.

The strongly gendered composition of the sample (88% female) underscores that underemployment in Australia is not only widespread among women but also shaped by diverse pathways of disadvantage. Although Class 2 (“childcare burden”) aligns with common assumptions linking women’s underemployment to caregiving, our results show that this is far from the full story. Women were also concentrated in Classes 1, 3, and 4, where economic insecurity, health difficulties, and social isolation were defining features. This demonstrates that female underemployment is not a singular phenomenon but rather spans multiple, overlapping vulnerabilities, with significant implications for equity, inclusion, and participation.

The policy implications are clear. Interventions must go beyond labour market mechanics to engage directly with the social determinants of underemployment. Reducing care burdens, tackling financial precarity, and supporting mental health are critical to enabling underemployed Australians to move into secure, meaningful work. By making visible these hidden dimensions, this study contributes a more complete evidence base to inform strategies that can both address Australia’s skills gap and promote equity in workforce participation.