Church-Led Social Capital and Public-Health Approaches to Youth Violence in Urban Zimbabwe: Perspectives from Church Leaders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Perspectives on Youth Violence

2.2. Regional Perspectives on Youth Violence

2.3. Youth Violence in Zimbabwe

2.4. Challenges in Leveraging Church Responses

3. Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

3.1. Social–Ecological Model (SEM)

3.2. Faith-Based Social Capital Theory (FBSCT)

3.3. Application to the Study

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Design

4.2. Study Location and Participant Sample

4.3. Interviews

4.4. Analysis

4.5. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

5. Results

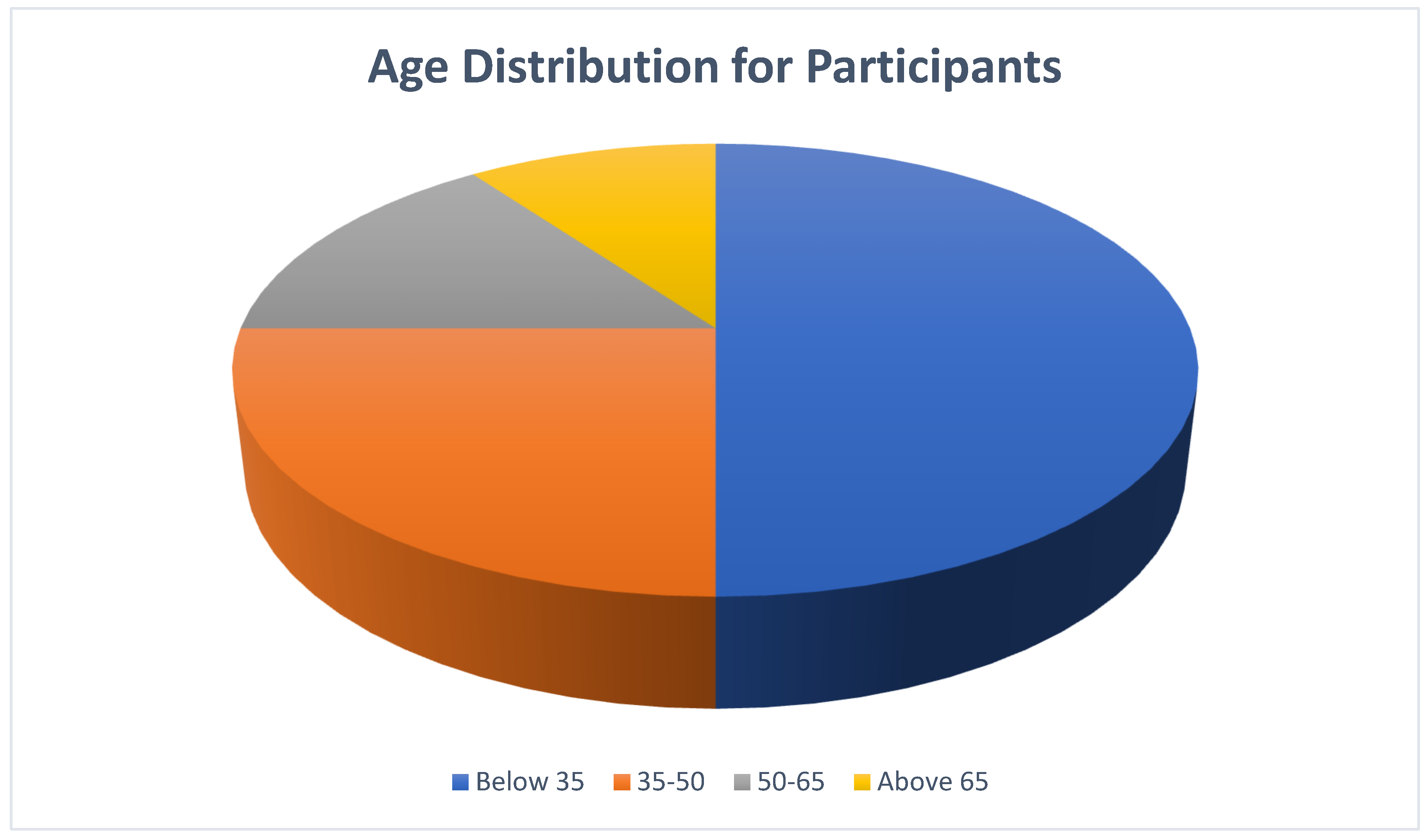

5.1. Participant Information. Theme 1: The Multi-Level Normalisation of Youth Violence

5.2. Theme 1: The Multi-Level Normalisation of Youth Violence

“You know our youths have not only been affected by political violence. There is violence everywhere. They engage in violence because of the drugs they abuse. Our township boys wake up expecting a fight the way others expect breakfast. Yesterday it was fists at the kombi rank; tomorrow it will be knives outside the bottle-store.”

“Nowadays for these young people in the streets, carrying a knife is now as normal as carrying a phone. You hear young people saying I need it for my protection and you ask yourself what has our society turned into.”(Participant 12)

“The reality is that our young people have become desensitized to violence. It’s now almost normal. They are exposed to violent behaviour on the streets, in their homes, in their schools even. So, most of them have grown up in environments where aggression and violence are a survival mechanism. You can imagine if you’ve seen your friend beaten up or even witnessing a family member being subject to violence, you are most likely going to resort to finding ways of protecting yourself and this is mostly violent as well. So, it becomes a cycle that feeds on itself, and it becomes even harder to break.”

“Violence has become so embedded in the daily lives of our young people. You know when they fall victim of violence, we see some of them attending church still with bruises and broken spirits, and they say, they have been involved in altercations, but it’s almost like they don’t see it as something out of the ordinary, just as another day in their world.”(Participant 5)

“From a pastoral standpoint, we’ve seen how exposure to constant violence shapes the mindset of our youth. They grow up in communities where violence is the expected outcome of most disputes. It is seen as a form of power and control. As a result, our youth have a distorted reality, and the politicians capitalise on this to incite political violence. That the challenge we are dealing with.”(Participant 18)

“I think the violence starts from the home environment in some cases. In some families, it’s the norm for young people to witness their parents or siblings engage in violent acts, whether it’s physical fighting or verbal abuse. This environment doesn’t teach love or peace; it teaches survival through dominance. In my experience, many of the youth we encounter in church come from these environments, so when they see violence being perpetuated elsewhere, for them it is almost as if it’s normal.”(Participant 11)

“It’s easy to blame drugs, gangs, and poverty for youth violence, but we must also consider the cultural erosion that has taken place in our communities. The moral fabric of society has been weakened. The respect for elders, the value of life, and the sanctity of human dignity—these are things that many of our youth no longer understand or appreciate. They live in a world where material success is prioritized over community well-being, and where violence is seen as the only means to assert power. The church’s role, therefore, is to teach not just moral principles, but to restore the dignity of the individual.”

“The violence we see today is not only physical but also emotional and psychological. Our young people are also victims of a society that has given up on them. Many of these youth carry scars of neglect, abandonment, and emotional trauma that fuel their anger. They lash out because they are in pain, not just because they have learned violence. It’s important to understand that the violence we witness is often a manifestation of deep-rooted hurt that has been ignored by both the state and community. Until we start addressing these emotional wounds, the violence will continue to escalate.”

“Some of the youth are caught in a cycle of violence because they don’t see any other option. We often forget that many of them have been abandoned by systems that should have supported them. When we talk about solutions, we must ask ourselves: what alternatives are we providing for these young people? The reality is that many of them have never been given a chance to experience peaceful conflict resolution, or positive models of leadership. They simply don’t know how to deal with problems without resorting to violence.”

5.3. Theme 2: Dealing with Spiritual and Structural Sources of Violence

“Violence whether domestic, gender-based, political or youth violence begins when the heart hosts an evil spirit; we cannot deal with it without addressing the state of the heart. That is why the church is critical in the fight against violence. We have to begin the fight spiritually and then do some programs physically to sustain the spiritual work. That’s the only way we can eradicate violence in our communities.”

“From a spiritual perspective, violence is deeply rooted in the hearts of individuals who are disconnected from God’s love.”

“While violence is evil, we cannot hide behind evil spirits. Some of the causes of this violence are man-made like poor governance, mismanagement of resources, corruption, lack of creation of jobs for the young people in particular. So yes we can cast evil spirits out, but if the unemployment remains, we are far from getting rid of violence. That is how I see it.

We must also address the structures that oppress our youth, such as poverty and lack of opportunities. The Bible speaks of justice and fair treatment for the poor, so as a church, we must actively engage in both spiritual and structural restoration. Prayer alone will not change the fact that many of our young people have no jobs or no hope for the future.”

“It’s simple, we need to pray and seek God. Remember, the bible says in Chronicles, if the people who are called by my name will humble themselves and pray and repent from their sins I will hear from heaven and will heal their land. Prayer is the answer. We need to pray and repent as a nation from all the violence and turn to God for help.”

“Interestingly, this should be our role (to prevent violence) because the bible says that the blessed are the peacemakers. We should make sure that we play a role in making our communities peaceful.”

“Violence is indeed a manifestation of deeper spiritual issues, but we cannot ignore the socio-economic pressures that lead young people to violence. While prayer and spiritual intervention are paramount.”

“While I understand the spiritual forces at play in violence, I do not believe that we can address violence only through prayer. Yes, prayer is essential, but we must also address the consequences of years of neglect and lack of support systems for our youth. For many, violence is an outlet for frustration, and if we only pray without offering concrete solutions—like jobs, education, and mental health support—we are not truly addressing the root causes of violence. It’s a cycle of despair that needs a holistic intervention, not just a spiritual one.”

“Violence may have its spiritual roots, but we must also recognize that some people have grown accustomed to living in an environment where violence is a way of life. It becomes ingrained in their behaviour, especially when no other alternatives are offered. We can pray all we want, but we must also give our youth hope—hope for a future where they are not trapped in a cycle of violence and poverty. Prayer and spiritual intervention alone cannot fill the void left by the lack of hope or opportunity. We must actively work to provide the youth with better options for their lives.”

“The real challenge with addressing violence lies not just in the spiritual domain but also in the societal structures that uphold injustice. The violence in our communities often arises from structural inequality, where the poor and marginalized are left with no recourse but to turn to aggression. The church has a duty to fight for social justice, to speak out against the systems that perpetuate violence—whether in the form of corrupt leadership or exploitation of the vulnerable. It’s not just about ‘casting out spirits’—it’s about dismantling the systems that enable violence to thrive in the first place.”

5.4. Theme 3: Building Safety Nets and Violence Prevention

“In this part of the world, it is very easy for church leaders to identify these spheres of violence, because it’s very obvious in this part of the world… It’s very obvious to identify… Young people are easy to read, they can barely hide their frustrations. If they are not happy with something they will voice it out, you will see by their actions that something is wrong.”

“You can see that sometimes young people don’t go to church. They don’t go to church, sometimes not because they don’t want to go to church but because there are certain obstacles—for example, there’s no money for transport…But if the trend is persistent, it could be because of dissatisfaction and frustration….”

“Our church has long-established peer networks within the youth group. These networks allow young people to monitor and influence each other’s behaviours in a way that is both supportive and corrective. If one member is going down a dangerous path, the rest of the group—often without much intervention from us—will address the issue. It’s these deep relational connections that help us prevent violence at a peer level. When the bond is strong, young people tend to help each other, and that’s a powerful resource. We just need to make sure we cultivate these networks effectively.”

“We’ve seen great success in collaborating with other faith-based organizations and local NGOs to provide our youth with alternative outlets. Whether it’s sporting events, creative workshops, or community outreach, these partnerships broaden the scope of what we can offer our youth. These projects give young people a sense of belonging outside of the violent environments they may be exposed to. We have a responsibility to bridge these gaps in their lives, not just through preaching but through tangible actions that give them hope and direction.”

“One of the most effective strategies we’ve adopted is our collaboration with local government agencies, especially those focused on youth development and employment. These partnerships enable us to provide resources, such as vocational training and health services, that directly address the root causes of violence—unemployment, lack of skills, and mental health issues. It’s crucial that the church acts as a connector, linking the youth with the resources and opportunities they need to thrive. This is where our work with state agencies becomes crucial in complementing what we do spiritually.”

“It is essential to have programs where youth can voice their concerns and frustrations in a safe space. These workshops, often done in partnership with local government and NGOs, not only help them articulate their struggles but also offer them a clear path for solutions. We encourage them to look for peaceful resolutions, but these programs also introduce them to social services that can assist in dealing with trauma, substance abuse, and joblessness. This gives them real alternatives to the violence they may encounter on the streets.”

“The number two way is having projects that we do with the government… then we come in as a church… it would be easier for us to identify that violence and to deal with it. The emphasis here is on the proactive, developmental role of the church. This includes conducting workshops, training programs, and leadership development courses. The church can also conduct workshops for its congregants, as much as the church does have workshops that address other subjects like HIV/AIDS, let the church have workshops that address matters of peace and reconciliation, political violence, or any other form of violence and not just narrow it down to violence and at the same time conscientize the congregants who in turn will understand their role in society. Sometimes we do have our congregants that engage in political violence when they get out there because they are not equipped. They lack conscientization.”

5.5. Theme 4: Gendered Nature of Youth Violence

“In 2008 I had a member in my church who was pregnant. And during the political violence, she was beaten to an extent that she even lost her pregnancy because of the internal injuries she had sustained. Even though we could pray for her and counsel her, it is a difficult process for her to completely heal from the whole experience. Emotionally she was broken. It is difficult for her to erase that picture, yes by grace she has forgiven them over the years but that experience lives with her forever. It’s very difficult for women (and girls) to cope with the aftereffects of violence.”(Participant 2)

“There are women who were raped in political violence… they cannot talk about it. Some were infected with diseases. Some were chased away from their homes by their husbands after that. Some even got pregnant and gave birth to children from these unfortunate events. The targeting of women is totally evil.”

“During conflict, young women and girls, especially in conflict zones, experience violence in ways that are not just physical but deeply psychological. The scars of sexual violence, emotional torment, and the stigma of being victims are not easily healed… The hardest part for them is the internal shame they feel, and it often leads to isolation. The church’s role is not only to provide spiritual healing but also to create safe spaces where women can express their pain without fear of judgment.”

“The gendered aspect of violence is something we often overlook in our communities. Young men, while victims in their own right, often perpetuate violence against women because they are socialized to view women as subordinate. In our church, we must actively address these gendered norms and teach our young men about respect, equality, and the dignity of women. We cannot build a peaceful society unless we challenge the patriarchal structures that allow this violence to continue.”

“I’ve seen young women in my congregation who were affected by political violence, and while their bodies may heal, the emotional damage lasts forever. These women are often left to deal with the trauma alone, without the support they need from their communities. The church has a responsibility not only to provide spiritual counsel but also to address the systemic silence that surrounds gendered violence. We must speak up for the women whose pain is ignored because of their gender. Until we address this silence, the cycle of violence will continue.”

“While men often suffer physical violence, women bear the brunt of violence in ways that affect their dignity. Rape, sexual harassment, and the constant fear of being targeted simply because of their gender are daily realities for many of our young women. What is even more heartbreaking is the reluctance of the community to support them in the aftermath. Women are often blamed, ostracized, or ignored, and this is where the church’s role becomes crucial. We must not only provide support to the victims but also educate the community to stop the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes.”

“Violence against women is not just a physical act; it is a means of asserting power and control. In the context of our youth, this power dynamic is perpetuated by both social and political forces. We must address this issue at its core by educating young people about gender equality, respect for women, and the role of women in our society. The church must teach these principles clearly, because if we don’t, the cycle of violence will only continue, and women will continue to be the primary victims.”

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FBSCT | Faith-Based Social Capital Theory |

| LMIC | Low and Middle Income Countries |

| FBO | Faith Based Organisation |

| SEM | Socio-Ecological Model |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- Almeida, Telma Catarina, Jorge Cardoso, Ana Francisca Matos, Ana Murça, and Olga Cunha. 2024. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Aggression in Adulthood: The Moderating Role of Positive Childhood Experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect 154: 106929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachan, Varushka, Molefe Itumeleng, and Davies Bronwen. 2022. Investigating blood alcohol concentrations in injury-related deaths before and during the COVID-19 national lockdown in Western Cape, South Africa: A cross-sectional retrospective review. South African Medical Journal 113: 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivio, Michael T., and Nathan Epps. 2016. The Interrelatedness of Adverse Childhood Experiences Among High-Risk Juvenile Offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 14: 179–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Christopher, and Greg Smith. 2010. Spiritual, religious and social capital—Exploring their dimensions and their relationship with faith-based motivation and participation in UK civil society. Paper presented at The BSA Sociology of Religion Group Conference, Edinburgh, UK, April 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, Yasmin, Davids Adlai, and London Leslie. 2020. Alcohol outlet density and deprivation in six towns in Bergrivier municipality before and after legislative restrictions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11: 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broidy, Lisa M., Anna L. Stewart, Carleen M. Thompson, April Chrzanowski, Troy Allard, and Susan M. Dennison. 2015. Life Course Offending Pathways Across Gender and Race/Ethnicity. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology 1: 118–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, Christopher, and Matthew Wood. 2012. Cultured responses: The production of social capital in faith-based organizations. Current Sociology 60: 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. Community Violence Prevention Resource for Action: A Compilation of the Best Available Evidence for Youth and Young Adults; Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violence-prevention/media/pdf/resources-for-action/CV-Prevention-Resource-for-Action_508.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Chemvumi, Tinashe. 2011. Can the Church Use Pastoral Care as a Method to Address Victims of Political Violence in Zimbabwe? Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [Google Scholar]

- Chidhawu, Tinotenda. 2024. A turning-point for transitional justice? Political violence in Zimbabwe, and transformative justice as a wayforward. Law, Democracy and Development 28: 129–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigiji, Handrick, Deborah Fry, Tinashe E. Mwadiwa, Aldo Elizalde, Noriko Izumi, Line Baago-Rasmussen, and Mary C. Maternowska. 2018. Risk factors and health consequences of physical and emotional violence against children in Zimbabwe: A nationally representative survey. BMJ Global Health 3: e000533. Available online: https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/3/e000533 (accessed on 13 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chipalo, Edson, and Haelim Jeong. 2023. The prevalence and association of adverse childhood experiences with suicide-risk behaviours among adolescents and youth in Zimbabwe. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 42: 163–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirambwi, Kudakwashe. 2016. Addressing the Healing of Youth Militia in Mashonaland East Province, Zimbabwe. In Building Peace via Action Research African Case Studies. Addis Ababa: University of Peace Africa Programme, pp. 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W., and Cheryl N. Poth. 2018. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dodo, Obediah. 2018. Containment Interventions for the Youth Post-Political Violence: Zimbabwe. Development and Society 47: 119–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dodo, Obediah. 2023. Apostolic Churches and Youth Response to Social Challenges Post-Violence in Zimbabwe. In The Palgrave Handbook of Religion, Peacebuilding, and Development in Africa. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 381–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dodo, Obediah, Mateko Definite, and Mpofu Blessmore. 2019. Youth violence and weapon mapping: A survey of youth violence in selected districts in Zimbabwe. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 29: 954–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodo, Obediah, Nsenduluka Everisto, and Kasanda Sichalwe. 2016. Political bases as the Epicenter of violence: Cases of Mazowe and Shamva, Zimbabwe. Journal of Applied Security Research 11: 208–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, Naomi N., Barbara J. McMorris, Sandra L. Pettingell, and Iris W. Borowsky. 2010. Adolescent Violence Perpetration: Associations with Multiple Types of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Pediatrics 125: e778–e786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldred, Emily, Turner Ellen, Fabbri Camilla, Bhatia Amiya, Lokot Michelle, Nhenga Tendai, Nherera Charles, Nangati Progress, Moyo Ratidzai, Mgugu Dorcas, and et al. 2025. Embedding violence prevention in existing religious and education systems: Initial learning from formative research in the Safe Schools Study in Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health 25: 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfversson, Emma, and Kristine Höglund. 2019. Violence in the city that belongs to no one: Urban distinctiveness and interconnected insecurities in Nairobi (Kenya). Conflict, Security & Development 19: 347–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfversson, Emma, Höglund Kristine, Mutahi Patrick, and Okasi Benard. 2024. Insecurity and Conflict Management in Urban Slums: Findings From a Household Survey in Kawangware and Korogocho, Nairobi. Nairobi: Centre for Human Rights and Policy Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwosu, Ifenyiwa L., and Benjamin S. C. Uzochukwu. 2025. Prevalence, risk factors and interventions to prevent violence against adolescents and youths in Sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. Reproductive Health 22: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farge, Emma. 2024. Nearly a quarter of adolescent girls suffer partner violence, WHO study finds. Reuters. July 29. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/nearly-quarter-adolescent-girls-suffer-partner-violence-who-study-finds-2024-07-29/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Fergusson, David M., Frank Vitaro, Brigitte Wanner, and Mara Brendgen. 2007. Protective and Compensatory Factors Mitigating the Influence of Deviant Friends on Delinquent Behaviours During Early Adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 30: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Greg, Emily E. Namey, and Marilyn L. Mitchell. 2020. Collecting Qualitative Data: A Field Manual for Applied Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Gukurume, Simbarashe. 2018. New Pentecostal Churches, Politics and the Everyday Life of University Students at the University of Zimbabwe. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Gukurume, Simbarashe. 2022. Youth and the temporalities of non-violent struggles in Zimbabwe: #ThisFlag Movement. African Security Review 31: 282–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth, Christine, and Sean Stitt. 2007. Social Capital & Faith-Based Organisations. The Heythrop Journal 48: 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leban, Lindsay, and Delilah J. Delacruz. 2023. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Delinquency: Does Age of Assessment Matter? Journal of Criminal Justice 86: 102033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maforo, Byron. 2020. The Role of the Church in Promoting Political Dialogue in a Polarized Society: The Case of Zimbabwe Council of Churches 2017–2020. Master’s dissertation, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe. [Google Scholar]

- Masengwe, Gift. 2024. The moral authority and prophetic zeal of the Christian Church in Zimbabwe. In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi 58: 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matjasko, Jennifer L., Alana M. Vivolo-Kantor, Greta M. Massetti, Kristin Holland, and Melissa K. Holt. 2012. A systematic meta review of evaluations of youth violence programs: Common and divergent findings from 25 years of meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Aggression and Violent Behavior 17: 540–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mugari, Ishamel. 2024. The emerging trends and response to drug and substance abuse among the youth in Zimbabwe. Social Sciences 13: 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muswerakuenda, Faustina F., Paddington T. Mundagowa, Clara Madziwa, and Fadzai Mukora-Mutseyekwa. 2023. Access to psychosocial support for church-going young people recovering from drug and substance abuse in Zimbabwe: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 23: 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndlovu, James. 2025. Gendered Political Violence and the Church in Africa: Perspectives from Church Leaders. Religions 16: 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, Sarah E., Oladoyin Okunoren, and Thomas M. Crea. 2023. Youth who have lived in alternative care in Nigeria, Zambia, and Zimbabwe: Mental health and violence outcomes in nationally representative data. JAACAP Open 1: 141–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojiemudia, Eromosele F., Samson Ajetomobi, Oluseun T. Womiloju, Ayodeji S. Adeusi, and Yusuf O. Adebayo. 2024. Understanding faith-based responses to gun violence and the moral and ethical challenges in religious communities. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 24: 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Yok-Fong, Kristopher H. Yeager, Erik M. Cruz, Rebecca Cole, and Luis R. Torres-Hostos. 2025. Understanding Youth Violence Through a Socio-Ecological Lens. Social Sciences 14: 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilossof, Rory, ed. 2021. Fending for Ourselves: Youth in Zimbabwe, 1980–2020. Oxford: African Books Collective. [Google Scholar]

- Pswarayi, Lloyd. 2020. Youth Resilience and Violence Prevention: Some Insight from Selected Locations in Zimbabwe. Politeia 39: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, Antônio. 2020. Urban Drivers of Political violence: Declining State Authority and Armed Groups in Mogadishu, Nairobi, Kabul and Karachi. London: International Institute for Strategic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Shoko, Evans, and Maheshavari Naidu. 2020. Mapping the role of health professionals in peace promotion within an urban complex emergency: The case of Chegutu, Zimbabwe. Medicine, Conflict and Survival 36: 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, Merrill, and Emily Mendenhall. 2022. Syndemics in Global Health. A Companion to Medical Anthropology. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 126–44. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Merrill, Nicola Bulled, Bayla Ostrach, and Ginzburg Shir Lerman. 2021. Syndemics: A cross-disciplinary approach to complex epidemic events like COVID-19. Annual Review of Anthropology 50: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarusarira, Joram. 2015. Christianity, resistance and conflict resolution in Zimbabwe. In Handbook of Global Contemporary Christianity. Edited by Stephen J. Hunt. New York: Brill, pp. 266–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tsingo, Constance, Mushoriwa Taruvinga, and Chinyoka Kudzai. 2023. Strategies Taken by Churches in Curbing Drug Abuse among School going Youth in the Lowveld in Zimbabwe. Journal of Popular Education in Africa 7: 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe, Amelia, Andrew Dawes, and Catherine L. Ward. 2013. The development of youth violence: An ecological understanding. In Youth Violence: Sources and Solutions in South Africa. Edited by Andrew Dawes, Amelia Van Der Merwe and Catherine L. Ward. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, pp. 53–92. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2024a. INSPIRE Technical Package: Seven Strategies for Ending Violence Against Children. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2024b. Youth Violence: Key Facts. Geneva: WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/youth-violence (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Zambara, W. M. 2014. Non-Violence in Practice: Enhancing the Churches’ Effectiveness in Building a Peaceful Zimbabwe Through Alternatives to Violence Project (AVP). Ph.D. dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Zengenene, Maybe, and Emy Susanti. 2019. Violence against women and girls in Harare, Zimbabwe. Journal of International Women’s Studies 20: 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zvaita, Gilbert T., and Sylvia B. Kaye. 2023. Peacebuilding agency among the youth in the high-density suburb of Mbare, Zimbabwe. African Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies 12: 7–25. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/10.31920/2634-3665/2023/v12n2a1 (accessed on 13 July 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ndlovu, J. Church-Led Social Capital and Public-Health Approaches to Youth Violence in Urban Zimbabwe: Perspectives from Church Leaders. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100602

Ndlovu J. Church-Led Social Capital and Public-Health Approaches to Youth Violence in Urban Zimbabwe: Perspectives from Church Leaders. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):602. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100602

Chicago/Turabian StyleNdlovu, James. 2025. "Church-Led Social Capital and Public-Health Approaches to Youth Violence in Urban Zimbabwe: Perspectives from Church Leaders" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100602

APA StyleNdlovu, J. (2025). Church-Led Social Capital and Public-Health Approaches to Youth Violence in Urban Zimbabwe: Perspectives from Church Leaders. Social Sciences, 14(10), 602. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100602