Intersecting Systems of Power Shaping Health and Wellbeing of Urban Waste Workers in the Context of COVID-19 in Vijayawada and Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“a person or groups of persons informally engaged in collection and recovery of reusable and recyclable solid waste from the source of waste generation: the streets, bins, material recovery facilities, processing and waste disposal facilities for sale to recyclers directly or through intermediaries to earn their livelihood.”(p. 55)

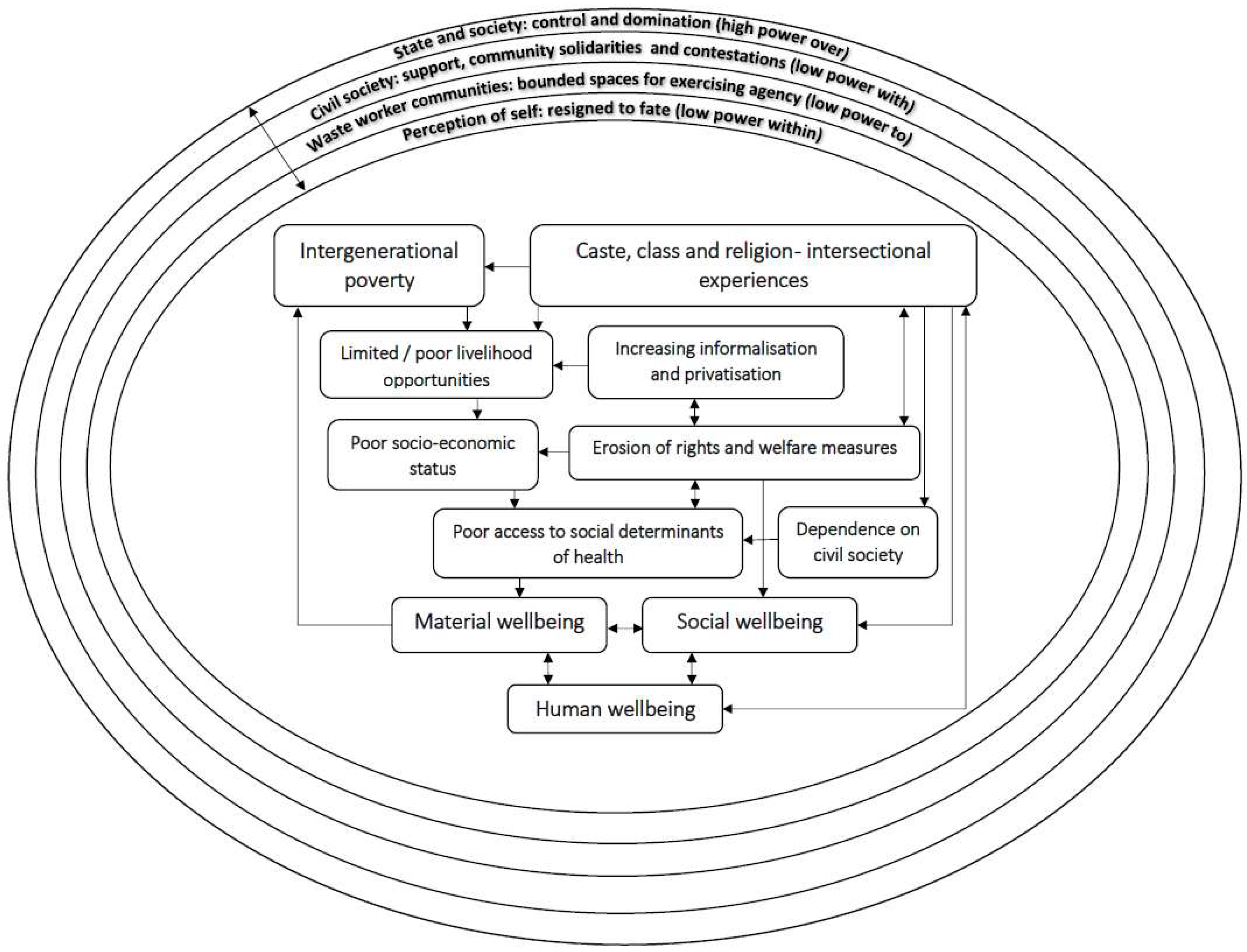

Conceptual Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Material Dimensions

3.1.1. Precarious Livelihoods, Exacerbated during COVID-19 Crisis

- -

- WW 3, Guntur, male, waste picker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- WW 2, Guntur, male, contractual waste worker

- -

- FGD 5, Vijayawada

- -

- WW 3, Guntur, male, waste picker

- -

- WW 2, Guntur, male, contractual waste worker

- -

- FGD 5, Vijayawada

3.1.2. Food Insecurity

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- FGD 5, Vijayawada

3.1.3. Access to Housing, Water, and Sanitation

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- WW 5, Vijayawada, male, waste picker

- -

- WW 2, Guntur, male, contractual waste worker

- -

- WW 2, Guntur, male, contractual waste worker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

3.2. Human Dimensions

3.2.1. Constrained Aspirations: Generational Transfer of a Precarious Occupation

- -

- WW 3, Guntur, male, waste picker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- FGD 5, Vijayawada

3.2.2. Assertion of Capacity, Capabilities, and Aspirations

- -

- WW 3, Guntur, male, waste picker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- WW 1, Guntur, female, contractual waste worker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- WW 1, Guntur, female, contractual waste worker

- -

- FGD 3, Guntur

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- FGD 3, Guntur

3.3. Social Relations

3.3.1. POWER OVER: Relations with the State in Daily Lives

- -

- WW 3, Guntur, male, waste picker

- -

- WW 5, Vijayawada, male, waste picker

- -

- WW 6, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- FGD 3, Guntur

- -

- WW 5, Vijayawada, male, waste picker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- FGD 4, Guntur

- -

- WW 6, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

3.3.2. POWER OVER: Discrimination and Disrespect in Societal Interactions

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- WW 6, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

- -

- WW 6, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

3.3.3. POWER WITH: Agency Limited to Coping Strategies

Community

- -

- WW 7, Vijayawada, male, waste picker

- -

- WW 1, Guntur, female, contractual waste worker

- -

- WW 4, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

- -

- WW 5, Vijayawada, male, waste picker

- -

- WW 6, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

- -

- WW 7, Vijayawada, male, waste picker

- -

- WW 6, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

Civil Society

- -

- WW 6, Vijayawada, female, waste picker

- -

- FGD 2, Vijayawada

- -

- KI 1, Guntur

- -

- KI 2, Guntur

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Interview Type | Participant Code | City | Gender | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WW * | WW 1 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker |

| WW 2 | Guntur | Male | Contractual waste worker | |

| WW 3 | Guntur | Male | Waste picker | |

| WW 4 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| WW 5 | Vijayawada | Male | Waste picker | |

| WW 6 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| WW 7 | Vijayawada | Male | Waste picker | |

| KII | KI 1 | Guntur | - | - |

| KI 2 | Guntur | - | NGO program coordinator | |

| FGD 1 | FGD 1-P1 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker |

| FGD 1-P2 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 1-P3 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 1-P4 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 1-P5 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 1-P6 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 1-P7 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 1-P8 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 2 | FGD 2-P1 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker |

| FGD 2-P2 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 2-P3 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 2-P4 | Vijayawada | Male | Waste picker | |

| FGD 2-P5 | Vijayawada | Male | Waste picker | |

| FGD 2-P6 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 2-P7 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 2-P8 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 3 | FGD 3-P1 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker |

| FGD 3-P2 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker | |

| FGD 3-P3 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker | |

| FGD 3-P4 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker | |

| FGD 3-P5 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker | |

| FGD 3-P6 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker | |

| FGD 3-P7 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker | |

| FGD 3-P8 | Guntur | Female | Contractual waste worker | |

| FGD 4 | FGD 4-P1 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker |

| FGD 4-P2 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 4-P3 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 4-P4 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 4-P5 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 4-P6 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 4-P7 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 4-P8 | Guntur | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5 | FGD 5-P1 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker |

| FGD 5-P2 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5-P3 | Vijayawada | Male | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5-P4 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5-P5 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5-P6 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5-P7 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5-P8 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker | |

| FGD 5-P9 | Vijayawada | Female | Waste picker |

References

- Bajaj, Jasbir Singh. 1995. Report of the High Power Committee Urban Solid Waste Management in India; New Delhi: Planning Commission, Government of India.

- Butt, Waqas H. 2019. Beyond the Abject: Caste and the Organization of Work in Pakistan’s Waste Economy. In International Labor and Working-Class History. Edited by Kate Brown, Marjoleine Kars and Marcel van der Linder. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 95, pp. 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty, Abhimanyu. 2020. Fighting from the Bottom, India’s Sanitation Workers Are also Frontline Workers Battling COVID. Indian Express. Available online: https://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-sanitation-workers-waste-pickers-coronavirus-pandemic-6414446/ (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. 2017. On Intersectionality: Essential Writings. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drydyk, Jay. 2013. Empowerment, Agency, and Power. Journal of Global Ethics 9: 249–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmatty, Francis J., and Vinay V. Panicker. 2019. Ergonomic Interventions among Waste Collection Workers: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics 72: 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garimella, Surekha, Shrutika Murthy, Lana Whittaker, and Rachel Tolhurst. 2021. Pandemic Policy Responses and Embodied Realities among ‘waste-Pickers’ in India. In Viral Loads: Anthropologies of Urgency in the Time of COVID-19. Edited by Lenore Manderson, Nancy Burke and Ayo Wahlberg. London: UCL Press, pp. 201–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gidwani, Vinay. 1992. Waste’ and the Permanent Settlement in Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly 27: 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gidwani, Vinay, and Amita Baviskar. 2011. Urban Commons. Economic and Political Weekly 46: 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gidwani, Vinay, and Julia Corwin. 2017. Governance of Waste. Economic & Political Weekly 52: 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gidwani, Vinay, and Anant Maringanti. 2016. The Waste-Value Dialectic: Lumpen Urbanization in Contemporary India. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 36: 112–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Kaveri. 2009. Of Poverty and Plastic: Scavenging and Scrap Trading Entrepreneurs in India’s Urban Informal Economy. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harriss-White, Barbara. 2017. Formality and Informality in an Indian Urban Waste Economy. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 37: 417–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harriss-White, Barbara. 2020. Waste, Social Order, and Physical Disorder in Small-Town India. The Journal of Development Studies 56: 239–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hasiru Dala. 2021. Help India’s Most Invisible Frontline Covid Workers—Waste Pickers. Ketto. Available online: https://www.ketto.org/fundraiser/HasiruDalaCovidRelief (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Joshi, Nupur. 2017. Low-Income Women’s Right to Sanitation Services in City Public Spaces: A Study of Waste Picker Women in Pune. Environment and Urbanization 30: 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josyula, K. Lakshmi, Shrutika Murthy, Himabindu Karampudi, and Surekha Garimella. 2022. Isolation in COVID, and COVID in Isolation—Exacerbated Shortfalls in Provision for Women’s Health and Well-Being among Marginalized Urban Communities in India. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health 2: 769292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornberg, Dana. 2019. From Balmikis to Bengalis: The ‘Casteification’ of Muslims in Delhi’s Informal Garbage Economy. Economic and Political Weekly 54: 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, Leslie. 2005. The Complexity of Intersectionality. Signs 30: 1771–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. 2013. National Urban Health Mission India. Available online: https://nhm.gov.in/index1.php?lang=1&level=1&sublinkid=970&lid=137 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. 2018. Empowering Marginalised Groups-Convergence between SBM and DAY-NULM. Available online: https://nulm.gov.in/PDF/NULM_Mission/SBM_NULM_Convergence_Guideline.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- National Commission on Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector. 2007. Reports on the Financing of Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector and Creation of a National Fund for the Unorganised Sector. New Delhi. Available online: http://dcmsme.gov.in/Report_on_NCEUS_NAFUS.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Puar, Jasbir. 2017. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raghunandan, Vaibhav. 2021. In Photos: Delhi’s Waste Pickers Reel Under Double Whammy of Pandemic, Privatisation. The Wire. Available online: https://thewire.in/labour/in-photos-delhis-waste-pickers-reel-under-double-whammy-of-pandemic-privatisation (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Reddy, Rajyashree N. 2017. The Urban under Erasure: Towards a Postcolonial Critique of Planetary Urbanization. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 36: 529–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Joanna, James Kizito, Nkoli Ezumah, Peter Mangesho, Elizabeth Allen, and Clare Chandler. 2011. Quality assurance of qualitative research: A review of the discourse. Health Research Policy and Systems 9: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rowlands, Jo. 1995. Empowerment Examined (‘Empowerment’ à l’examen/Exame Do Controle Do Poder/Examinando El Apoderamiento (Empowerment)). Development in Practice 5: 101–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salve, Pradeep, Praveen Chokhandre, and Dhananjay Bansod. 2017. Assessing Musculoskeletal Disorders among Municipal Waste Loaders of Mumbai, India. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health 30: 875–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salve, Pradeep, Praveen Chokhandre, and Dhananjay Bansod. 2019. Multiple Morbidities and Health Conditions of Waste-Loaders in Mumbai: A Study of the Burden of Disease and Health Expenditure. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health 75: 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Schenck, Catherina J., Phillip F. Blaauw, Jacoba Viljoen, and Elizabeth C. Swart. 2019. Exploring the Potential Health Risks Faced by Waste Pickers on Landfills in South Africa: A Socio-Ecological Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, Amartya. 1985. Well-Being, Agency and Freedom: The Dewey Lectures 1984. Journal of Philosophy 82: 169–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 1992. Inequality Reexamined. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 1993. Capability and Well-Being. In The Quality of Life. Edited by Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, V. Kalyan, and Rohini Sahni. 2017. The Inheritance of Precarious Labor: Three Generations in Waste Picking in an Indian City. WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 45: 245–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, Mahesh, Yarrow Dunham, Catherine M. Hicks, and David Barner. 2016. Do Attitudes toward Societal Structure Predict Beliefs about Free Will and Achievement? Evidence from the Indian Caste System. Developmental Science 19: 109–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- The Gazette of India. 2016. Solid Waste Management Rules. India. Available online: https://cpcb.nic.in/uploads/MSW/SWM_2016.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Varma, Ravindra. 2002. Report of the National Commission on Labour. New Delhi. Available online: https://indianculture.gov.in/report-national-commission-labour-0 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- VeneKlasen, Lisa, and Valerie Miller. 2002. Power and Empowerment. PLA Notes 43: 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- White, Sarah C. 2010. Analysing Wellbeing: A Framework for Development Practice. Development in Practice 20: 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmer, Josie. 2021. ‘We Live and We Do This Work’: Women Waste Pickers’ Experiences of Wellbeing in Ahmedabad, India. World Development 140: 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmer, Josie, Sharada Srinivasan, and Mubina Qureshi. 2020. Women Waste Pickers’ Lives during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Ahmedabad. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3885161 (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- World Health Organisation. 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kakar, I.S.; Mallya, A.; Whittaker, L.; Tolhurst, R.; Garimella, S. Intersecting Systems of Power Shaping Health and Wellbeing of Urban Waste Workers in the Context of COVID-19 in Vijayawada and Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080333

Kakar IS, Mallya A, Whittaker L, Tolhurst R, Garimella S. Intersecting Systems of Power Shaping Health and Wellbeing of Urban Waste Workers in the Context of COVID-19 in Vijayawada and Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(8):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080333

Chicago/Turabian StyleKakar, Inayat Singh, Apeksha Mallya, Lana Whittaker, Rachel Tolhurst, and Surekha Garimella. 2022. "Intersecting Systems of Power Shaping Health and Wellbeing of Urban Waste Workers in the Context of COVID-19 in Vijayawada and Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India" Social Sciences 11, no. 8: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080333

APA StyleKakar, I. S., Mallya, A., Whittaker, L., Tolhurst, R., & Garimella, S. (2022). Intersecting Systems of Power Shaping Health and Wellbeing of Urban Waste Workers in the Context of COVID-19 in Vijayawada and Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, India. Social Sciences, 11(8), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080333