1. Introduction

When researching the development process, the inequalities or asymmetries between regions are always emphasized. For

Baer (

2007, p. 30), the most important factor in overcoming inequalities between provinces is their development. Inequality is an intrinsic characteristic of the Angolan economy, which has registered inequalities or asymmetries in one province in relation to others since colonial times and in each economic cycle. Angola has experienced and continues to experience unprecedented and accentuated inequality between its regions. Despite the government’s public policy efforts, the nation remains a country of great inequalities in Africa and in the world.

The concentration of productive and specific activities, as well as urban activities, have been concentrated in the mega-province of Luanda (Litoral), thereby, expanding its industrial capacity and the rural–urban transition of the population. Thus, at the economic, financial, and technological levels, there is a great disparity between the provinces, with Luanda being the largest financial and business center. The great differences are perceived not with all the provinces but with Moxico, Bengo, Cunene, Huila, Kuando Kubango, Huambo, Bié, Cuanza Sul, Uíge, Zaire, and Cabinda. In these last three, despite the advantages of high oil production, from the regional point of view, they remain almost stagnant in time in a type of social dysfunction where the population lives on extractivism and artisanal fishing.

This mechanism accentuates the regional asymmetries (

Boisier 1989). For

Béné and Neiland (

2003), when extractivism and artisanal fisheries are delivered to the sectoral and productive approach, they are not able to promote the development of this activity and, concomitantly, the province. This can be seen in the

Multidimensional Poverty Report of the Municipalities of Angola (MPPN) 2019, which indicated that the municipalities belonging to the first quintile (Luanda), the poverty levels were low, as they varied from 0.365 to 0.029. In contrast, provinces in the fourth and fifth quintile (Uíge, Lunda Norte, Kuando Kubango, Huila) had a poverty index of 0.6.

Since 2002, a series of events have marked the Angolan economy when the State assumed a leading role in the fight for inequality and the competitive integration of the regions in the international sphere. Some significant changes can be observed, such as public investment in education, infrastructure, transport networks, communication, and computerization of activities. On the other hand, this spending has reduced inequalities due to the fact that the Angolan economy has a productive structure that is not very diversified and competitive and has low intersectoral indices.

As public and private investments have permanently improved the economy in the developed provinces to the detriment of the less developed ones, the country continues to register asymmetries between provinces in terms of access to health, education, electrification, drinking water, basic sanitation, the fight against illiteracy, and access to the internet.

As noted in the 2019 Human Development Report, Angola’s HDI is 0.574—placing the country in the medium human development category—ranking it 149 out of 189 countries and territories considered in the report. Angola’s HDI value is below the average of 0.634 for countries in the medium human development group. However, when the HDI value is discounted for inequality, it reduces to 0.392 (

PNUD 2022). The HDI is below the average, and the Gini coefficient has a score of 0.513%, which shows us that inequalities continue (

World Bank 2022).

The importance of investment is based mainly on gross fixed capital formation, and in national accounting terms, investment is the oxygen of the economy, without which it is impossible to ensure the pace of development and reduce inequality. Despite huge public investments and the influx of various private investments, these have not succeeded in reducing the huge disparities between provinces but rather have further accentuated them.

How are the asymmetries between the regions of Angola related? What historical factors have consolidated them? Is it necessary to look back in history to correct the existing segments of differences and bridge the asymmetries we have today? Luanda is growing with new buildings, schools, water systems, internet, etc., and other provinces of Angola are still far from this reality. To answer these questions and to be able to reflect on this issue, we require theories that address regional development and help to understand why these disparities exist. According to

Acemoglu and Robinson (

2012, p. 331), while in Luanda, a new construction emerges every day, in other provinces, such as Bengo, people struggle to dig “cacimbas”

1 to get water.

To measure inequalities and asymmetries, data, such as access to drinking water, computers, differences in per capita income, regions, etc., were used. To analyze the possible causes, our research focused on the two most important events in the contemporary regional history: the Portuguese occupation and its forms of exploitation and the civil war. To compose the field of investigation of what is happening, Anita Kon’s study on subject region and object region and Boisser’s study on regional inequalities in the national panorama contribute to a better understanding of the historical levels of asymmetries and inequalities in Angola.

2. Methodology

A theoretical-reflexive study was conducted based on the reading of books, articles, and previous research on the phenomenon studied. Considering the interpretation and analysis of the theoretical content obtained through the bibliographic research conducted; this theoretical construction approaches the qualitative approach.

2.1. Data Analysis

The methodology followed for the preparation of this article was a bibliographic study, through which an exploratory and systematic research of books, articles, manuals, theses, and dissertations was conducted in addition to official documents from the Angolan Ministry of Economy, the National Institute of Statistics, and documents in electronic format from different virtual libraries, such as Scielo and Redalyc.

The key words, in Portuguese and English, used for the search were: “regional development”, “asymmetries”, inequalities, subject, and object region. This search took place in Luanda, Bengo, Cuanza Sul, and Cuito (Angola), during the period 1 March 2019 and 31 June 2021.

For this research, only three (3) provinces were chosen from among all those with large asymmetries: Luanda, Benguela, and Kuanza Sul. This sample was selected on a non-probabilistic basis, due to their characteristics, these provinces are the most representative and those that frame the characteristics and variables analyzed in this research.

2.2. Variables

The variables used in the review are those related to the responses to the initial questionnaire on the asymmetries between the different provinces of Angola.

To construct the data presented, we chose the IBEP study of 2009 about the population of the chosen provinces, which uses, for the calculation of inequalities, the asymmetries between the rural and urban population, the income of the 40% of the poorest on a daily basis, the population with access to drinking water and sanitation, the illiteracy rate, and others. We also analyzed the United Nations 2030 Agenda, other indicators related to public investment levels, differences between provinces in some attributes, education in relation to the level of poverty in Angola, and inequalities in employment and unemployment from the National Institute of Statistics (INE), the Center for Catholic Studies and Research (CEIC), and the World Bank (WB).

Thus, the variables defined for the study were:

Portuguese form of operation—target region—subject region.

Construction of infrastructure in the target regions.

Occupation and exploitation of the coast.

Civil war.

Rural exodus.

Infrastructure of the provinces.

2.3. Indicators

The authors consider that the best indicator to analyze inequality is the Gini coefficient. However, due to the lack of information regarding this indicator for each of the provinces studied, the following indicators were chosen:

Historical data on the form of exploitation and indicators of current asymmetries, such as:

- ○

Access to infrastructure: basic sanitation, drinking water.

- ○

Access to housing: decent housing in view of the construction of one million houses nationwide.

- ○

Access to education: fight against illiteracy and primary education.

- ○

Access to goods: the internet and computers.

- ○

Productivity.

- ○

Employment.

- ○

Public investments.

Population growth in the target regions.

Infrastructure underway: construction of the historic port, creation of the Lobito corridor, construction of railway lines, etc.

History of population in the provinces.

Destruction of infrastructure: schools, railroad lines, roads, power lines, and hospitals.

Anita Kon’s theories on the subject and the target region and Boisier’s theories on local and regional development were taken as the main theoretical underpinnings of this work because of the lack of authors dealing with the subject.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Region as Object and Subject for the Understanding of Inequalities and Asymmetries between Angolan Provinces

The historical construction of the concept of region implies dynamics directly linked to the social, economic, and cultural aspects of each historical moment, which makes it possible to understand a diversity of forms of appropriation and restructuring of space by the different social and economic agents that make up the scenario of regional transformations.

According to

Kon (

1992, p. 26), the methods of dealing with the region can be divided into two approaches:

- (a)

The region as an object.

- (b)

The region as a subject.

The region as an object was intensively used during the Portuguese colonization throughout the process of exploitation of its former colonies. It is the so-called endogenous process of exploitation of raw materials and their transformation into viable products for export. This analysis of the region as an object guided the economic development during colonization.

The endogenous view of a region as an object makes absent the perception that the productive process does not have variables directed to the whole territory in a single economic aspect. From a historical point of view, this analysis is perfectly visible when we relate the inequality between the provinces of Angola.

The form of economic exploitation of the Portuguese colonial system, both in America and Africa, was idealized by looking at the region as an object. Thus, the occupation and exploitation of the coastline with the construction of ports of exploitation became evident in a quick and utilitarian way to drain the production of these territories (for example: the exploitation of sugar cane in Brazil, a product destined for export through the ports of the northeast, which created regional asymmetries, remained, for centuries, between the northeast and southeast).

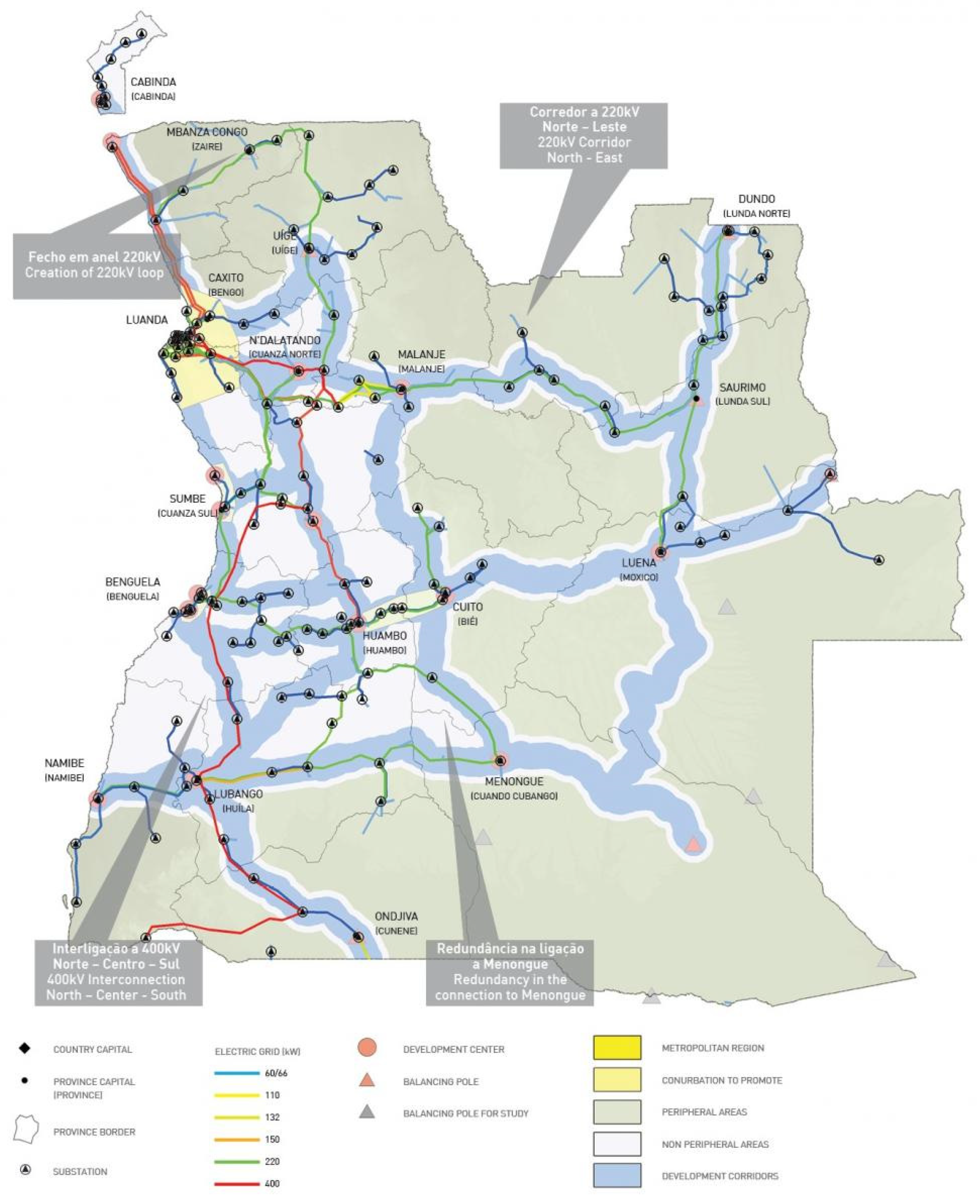

Another example, in the case of Angola, is the creation of the development of the Lobito corridor

Figure 1, which suffered two periods of sabotage: colonialism and civil war. It was created on the government of an object region without concern for the connection and economic development of other regions of Angola. The civil war was an element responsible for the poor performance of this region, and this had a devastating effect on infrastructure.

This caused a rupture in the productive process altered by the difficulties of the Benguela Railways to the productive area of Zambia, which made three provinces unequal: Luanda, Cuanza Sul, and Benguela, hindering the development in these areas and neighbors, such as the province of Huambo, Bié, and other central regions of Angola. The given interregionalism was interrupted and, consequently, lost its productive capacity, generating regional inequality between Luanda and Benguela and the other provinces interconnected in this process. Another example is the poor development of Cuanza Sul province.

According to (

Kon 1992, p. 26):

The first process is to recognize the social structure of the group that is part of this area, from there we have to identify the ethno-cultural elements in an anthropological vision, it is with scales at all levels (that is, local to global) without overlooking the evolution of the groups structured there, i.e., we cannot fail to identify the region as something legitimate and real, establishing the space as the place of the modes of living of the groups.

Another analysis of the province can be developed from the perspective of the region as the subject of its economic, political, and social history. This view of the region, as a subject, comprises two elements, the endogenous and the exogenous view, which implies the perception of the social and cultural variables within this territory. This view recognizes the social structure of the group that is part of this area. From there, it identifies the ethnic cultural elements in an anthropological vision and with scales at all levels, local and global, without ceasing to perceive the evolution of the groups structured there—that is, without ceasing to identify the region as something legitimate and real, establishing the space as the place of the modus vivendi of the groups.

According to (

Boisier 1989, p. 610):

[…] the process of separation between subject and object begins, which implies that the passage from the region-object to the region-subject, the region here must be seen at the same time as a geographical space and a social space.

That is to say, the matrix of social groups whose nexus of articulation is given by the collective consciousness of belonging to a common territory that will be part of a national territory, with sufficient specifications to differentiate themselves, and whose fractioned interests are structurally subordinated to a regional collective interest expressed in real, permanent, and transitory political projects.

Thus, when the subject function of the regions is recognized, it is the regional community that will exercise the right to be an actor. From this perspective, the development of a given region will be structured and analyzed on the basis of the regional actors themselves and will no longer be based on centralized planning. This structure will be achieved through a regional organization that will have as its main characteristic the broadening of the autonomous decision-making base of regional actors.

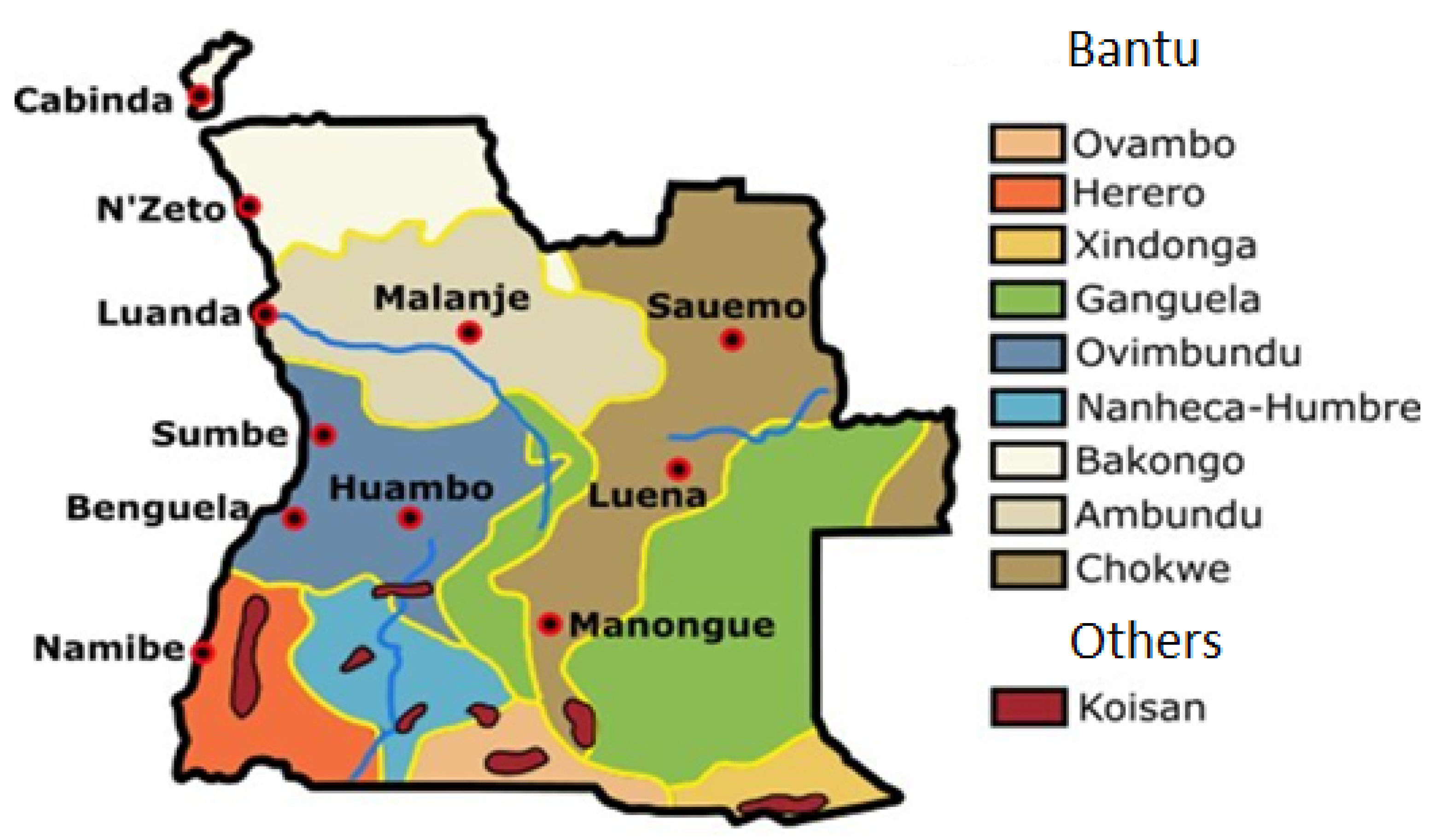

Combinations between people, culture, and traditions were not considered to constitute the region under study. Regions with the same ethnolinguistic origin (

Figure 2) but with variations perceived as different peoples, despite the degree of kinship and close identities, triggered huge disparities between producing and non-producing regions.

The region that includes the provinces of Luanda, Bengo, and Ndondo in Cuanza Norte as well as Ebo and Gabela in Cuanza Sul, reproduce close ethnolinguistic identities, i.e., in the same lineage; however, in the constitution of these regions as a subject, what was considered were the characteristics of the agrarian-exporting productive process. This resulted in the non-existence of the social history of these regions, which remained only as an object region, without considering the local, regional, national, and global scale.

In order to understand the region as an element of the territory, its space as a dimension of historical events cannot be neglected. Space must be understood as an a priori facet of the human experience and existence, and we are incapable of denying the flow of time associated with the fruit of its strategic alterations, which is the region. Considering the region only as an economic space or as an object makes it impossible to think globally and act locally.

3.2. Inequalities and Asymmetries. Its Evolution from the Colonial Era to the Beginning of the Civil War

The most important events in Angola’s contemporary regional history were the Portuguese occupation, which was Portuguese colonial rule over Angola (1890–1930), and the civil war, which was a struggle between Angolans for control of the country (1975–2002), in the consolidation of asymmetries between provinces.

If one looks back and analyzes the evolution of the Angolan economy in the colonial period, one can see that coffee is the main potential crop, with large-scale production in the province of Uíge, in the north of the country, along with cotton and rice in Malanje, and corn and sorghum in the southern provinces of Angola. The cultivation of coffee was, without a doubt, the great beginning of the Angolan economy, where it came to be considered one of the great coffee producers of the world, competing even with Brazil, Colombia, and other producers.

This was a period in which Angola as a colony was sustainable, especially in the agricultural sector, since its exports were centered not only in the cultivation of coffee but also in products, such as:

- (1)

Sisal (in the region of Benguela, in localities, such as Cubal, Nganda, Balombo, and Chongoroi).

- (2)

Tropical fruits in the Cavaco region of Benguela.

- (3)

Coffee in the Gabela region and agribusiness in the Waku-kungo region.

All these products would give the country the capacity to substitute imports, as they had comparative and competitive advantages in the international market, such as the northern region, specifically the province of Uíge, with advantages in the production and export of coffee. While large quantities of coffee were produced, unfortunately, the income from sales was not channeled to boost the region’s growth.

At that time, Angola was among the five largest producers of coffee in the world, in addition to other products (sisal and cotton). At that time, coffee accounted for more than 60% of exports. The strength of the agricultural sector coming from the north of the country drove the economic prosperity of Luanda, limiting the benefits and prosperity of the producing province (

Kanyenze et al. 2017, pp. 5–6). The benefits of all this prosperity were not transferred to the provinces from which they came, instead they were controlled by the Portuguese settlers residing in Luanda as well as in other cities and coastal provinces (Carvalho et al. 2011, named by

Kanyenze et al. 2017).

There was no investment in goods and services, technology parks, infrastructure, or research in the region to create value chains for this product. Currently, these provinces, especially Uíge, have a high poverty intensity index (a measure that reflects the severity of poverty, considering inequality among the poor), along with Lunda Sul, Huíla, and Moxico, between 7% and 9% (

INE 2020, p. 30). This type of farming did not bring development or quality of life to the communities involved because no thought was given to the future but only to income. Family farming during the colony existed only for domestic consumption and subsistence (

Garcia 2015, pp. 233–39). Angolan agriculture is strongly based on family farming.

According to data from the Agricultural Campaign Results Report (2018–2019) from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of the total cultivated in the country, Corporate Agriculture areas contributed only 9%, and family farms contributed 91% of the total. Family farming accounted for more than 17,500,000 tons of agricultural products in 2019. The development of family farming, in particular, is the decisive indicator for stabilizing the population in rural areas, combating hunger and reducing poverty. However, it does not always bring the expected development due to factors related to the current governments, public policies, subsidies to producers, etc. (

Garcia 2015, pp. 239–44).

Therefore, the profile of the agricultural sector based on family farming to understand the inequalities and asymmetries in the provinces is insufficient. Currently, Angolan agriculture is determined, on the one hand, by the urgency of public and private agricultural enterprises of various sizes and, on the other hand, by family farming, mainly intended for domestic consumption and its surpluses for the market. Clearly, the value derived from the production of surpluses by family farms, even under the best conditions (availability and location) in relation to the market, cannot be compared either in quantity or quality with the income produced by corporate agriculture.

Therefore, family farming runs a great risk of declining and ceasing to be a stabilizer of the rural population, thus, preventing the exodus to the cities, which would contribute to an increase in inequalities in those (

Garcia 2015, pp. 239–53). On the contrary, entrepreneurial agriculture (starting with coffee farming) results in being, in the authors’ opinion, a policy measure for the promotion and development of the provinces that depend on it and with tendencies to increase the areas dedicated to it. We see, therefore, that the provinces that remained on the routes or in the product exit zones benefited more, and the inequalities are smaller in comparison with the other less-developed provinces.

According to

Costa and Nijkamp (

2009), the fact that Luanda was an intermediary region for the export of agricultural products accentuated the disparities with the regions producing these products to the extent that export returns were invested and spent in the country’s capital, causing the development model to suffer a cutback and, consequently, the non-substitution of imports for exports.

The war contributed greatly to the paralysis of production which, in economic terms, weakened exports. Metropolis Portugal reacted by controlling the colony by sending a larger contingent of soldiers, hindering not only the economic processes but also the political and social ones. The Angolan population also became fragile, especially in terms of food security. In terms of regional development, this period saw the beginning of marked social inequality in areas where the confrontation had accelerated.

Regions, such as the north, west, and east of the country, which until then, had had little investment in the urban sector, remained almost stagnant—frozen in time. However, the central–south region, which had greater investment in the urban sector, maintained its structures almost intact in the areas where colonization had established its capital. Examples are cities, such as Huambo, Benguela, Huila, and even Sumbe. Luanda, as the capital, suffered greater impacts due to the displacement of the population from the places of conflict to the self-defense of the population groups.

The liberation war that ended with Angola’s independence in 1975 only confirmed, on the political level, a new relationship between the metropolis and the colony. Internally, Angola’s most difficult step towards definitively becoming a territory of Angolans began.

According to (

Manoel 2008, p. 216):

[…] both the first and the second internal civil wars were strongly reflected in the social conditions of the Angolan people. The population did not have time to celebrate its independence since power was transferred on November 11, 1975. Angola began to live in not only the reflection of the decolonization conditioned by the fall of Salazar but also the political and social disorganization for the stability of the future country since several parties claimed independence without the capacity of realization that, in the future, led to political, economic, and social instability, destabilizing the provinces.

The disagreement and contradiction between Angola’s liberation movements provoked the first internal civil war between 1979 and 1992. The cost of this conflict was the hyper-fragility of the economy, as part of the GDP was used to buy weapons. During this period, the economy was totally stagnant, and inflation reached 5000% in 1995. Urban and sanitary structures were destroyed, and the lack of water, energy, and basic sanitation made cities uninhabitable.

According to (

Vicente 1992, p. 82):

[…] the values of the losses with the first and second civil wars reached 40 billion dollars since the social destruction of several generations was not added to the accounting of the war. In addition, the destruction of the country’s infrastructure and sanitation resulted in the loss of a large built heritage and countless human lives due to the significant increase in mortality rates.

During the second civil war (1992–2002), it was possible to observe the dominance of the center–south regions in the economic sphere, particularly in small industry and agriculture in detriment of the absence of these basic sectors in the north and the center–west. In the national context, these differences led to the attraction of the population to the areas of the coastal strip, as the cities could not support the volume of these populations, causing difficulties in the field of health and environmental structures. From a structural point of view, the civil war deepened regional asymmetries, causing a large gap in Angola’s development. The industrial sector concentrated all its strength in the areas that received the basic infrastructure for a possible industrial start-up during the colonial period. Among them were Luanda and its surrounding cities (Viana and Cacuaco).

If we walk towards the south, the agro-industrial zone of Sumbe (Seles, Waku-kungo, and Conda) stands out, although the capital of Cuanza Sul has few industrial zones. Benguela, however, has received industrial investments that have begun to be rehabilitated today, such as the industrial complex of Catumbela. In turn, Novo Luango received some industries in the petrochemical sector, such as the new Lobito cement factory, and along the road to Catengue, new industrial zones are being extended. This has brought, to Benguela province, new investments in the education sector, such as the Katyvala Bwila (public), Piaget, Benguela, Lusíadas, and Catholic (private) universities.

The education sector allows learning new techniques, thereby, highlighting innovation and entrepreneurship itself, which is fundamental for economic development. From the above, there is the important factor that the asymmetries listed above are the result of a historical process, as some regions never received any investment to achieve greater development. In these areas, even in colonial times, urban structures received few initiatives, which aggravated the asymmetries (

Santos 2004).

However, in the war of liberation (both in the first and second civil wars), asymmetries and inequalities progressively deepened, provoking, in the most attractive areas, a permanent migration of populations from the areas where the civil war was strongly accentuated. The urban structures of some cities could not cope with such demographic demand, causing chaos in the urban environment.

3.3. Social Indicators for Understanding Inequalities and Asymmetries in the National Territory

After two periods of war that lasted more than 25 years with profound devastation, as mentioned above, the greatest employment and income opportunities as well as better living conditions were centered in the city of Luanda. As a result, Luanda was the city that attracted the most migration in the colonial era and before and after the war. As a consequence, an urban class different from the rural class was created (

Kanyenze et al. 2017, p. 13). Thus, while this province was marked by urban concentration, as already highlighted, and with adequate space for the development of activities, the possibility of communication, specialization, and complementarity of functions, the rest of the provinces were marked only by extension and dispersion. Therefore, the indicators that best explain the inequalities between provinces would be the urban-rural ones.

Since 1990, the Human Development Index (HDI) has been published annually by the Human Development Report (HDR). The HDI is a three-dimensional measure of development that encompasses long and healthy life expectancy (measured through life expectancy), education (measured through adult literacy, primary school enrollment, and primary and tertiary education attainment), and a decent standard of living measured through purchasing power, income, etc.

Although there is a national development plan that emphasizes the fight against inequalities and asymmetries between provinces, the HDI remains low at 0.574 (

PNUD 2022), ranking Angola 149th out of 189 countries.

According to the 2007/2008 UNDP report, Angola ranked 162nd in the human development table, and this position was due to GDP values and others, such as the infant mortality rate and the literacy rate, which showed modest values of 40.8% and 66.8%, respectively. In addition to these data, other indicators related to the demographic characteristics of the Angolan population in 2004 are worth mentioning, such as:

A high annual population growth rate, around 3%.

A high fertility rate: 7.2 children per woman.

Low investment in the population, with about 3.6% of the population over 60 years of age.

A high infant mortality rate: 140/1000 live births.

The above figures show and reveal the need for financial intervention by the state in various areas with greater emphasis on investment in social structures to reverse the negative picture. On the other hand, social indicators show a greater reluctance in the pre-peace period. The INE (National Institute of Statistics), through its specialized services of IBEP (Institute of Population Welfare) of 2010, conducted in the three provinces of Angola—Luanda, Benguela, and Cuanza Sul—highlights that more than 1.3% of the population lives below the poverty line, and in rural areas, reaching 58%, i.e., more than 1/3 of the Angolan population over 15 years of age cannot read or write.

Even so, according to

IBEP (

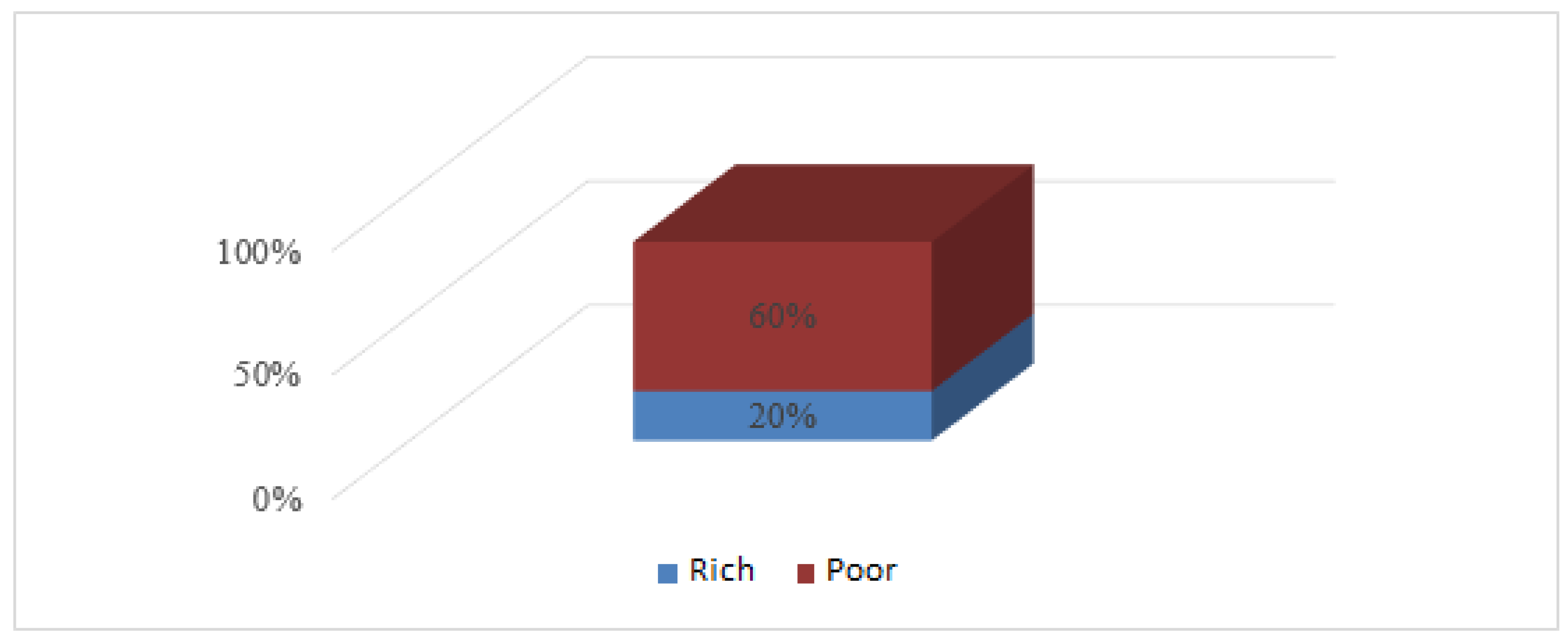

2010), if Angolan families are organized in terms of income, the income of the richest 20% of Angolan families is eight-times higher than the income of the poorest 60% of families

Figure 3.

With no margin for error, it can be stated that there is a poor distribution of income.

Figure 4 shows the concentration of income in Angola.

3.4. Asymmetries between the Rural and Urban Poor

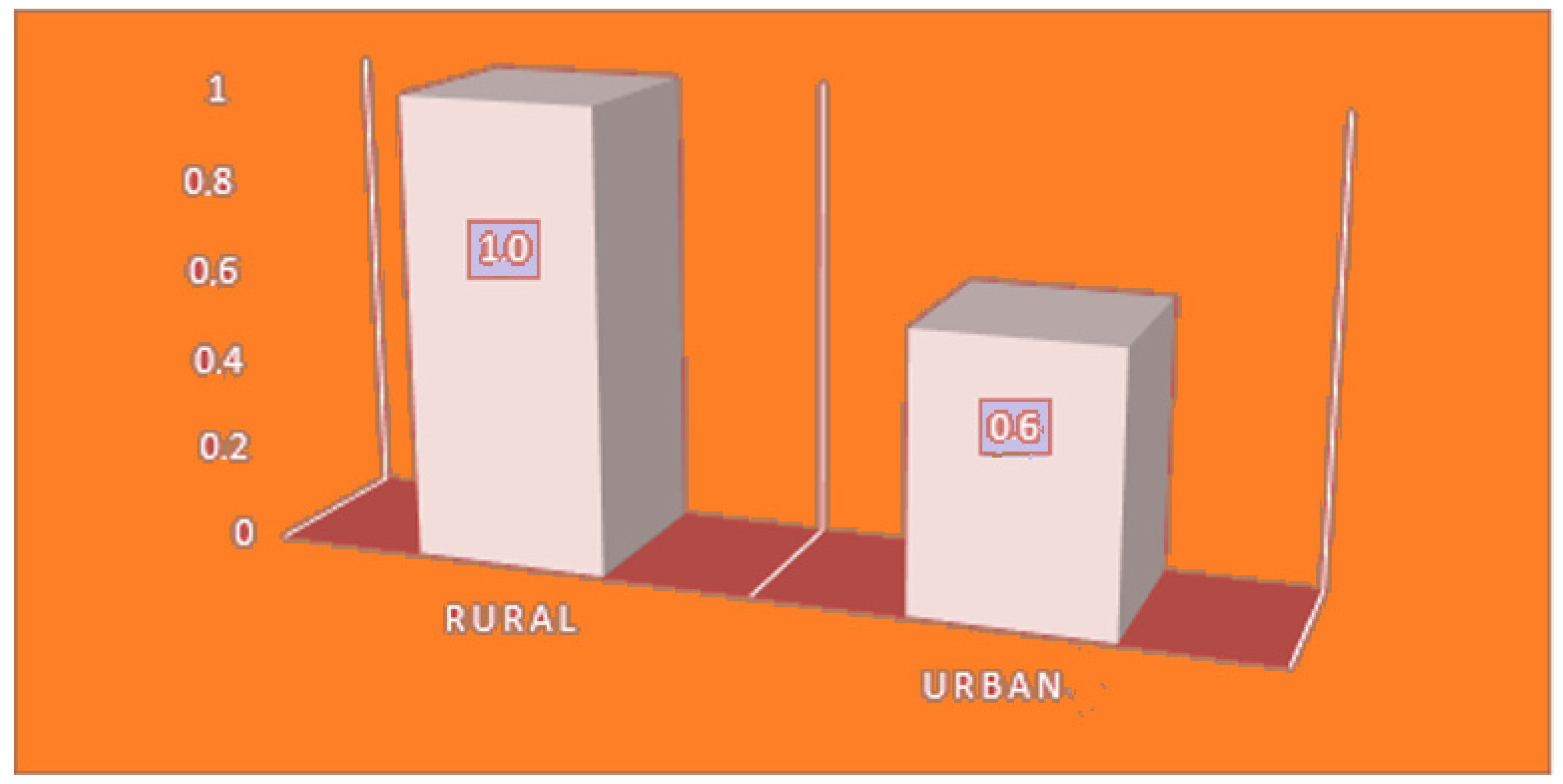

Despite the poor income distribution, it is important to note that, in Angola, the difference between the rural and urban poor in the same region is also abysmal.

Figure 5 shows that, among the Angolan population living on less than US

$1/day, those living in the countryside are the poorest, with an income of less than US

$0.6/day.

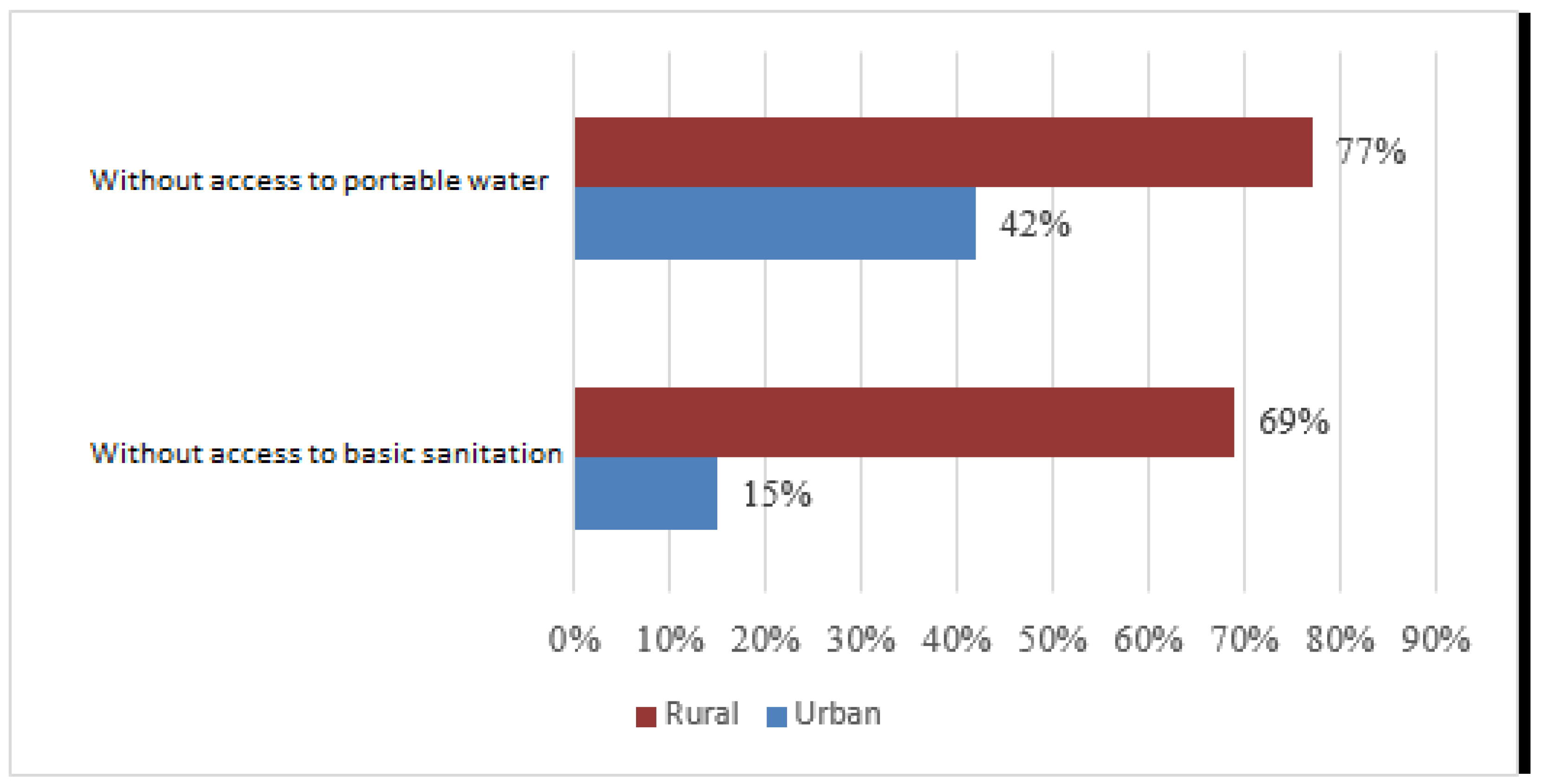

3.5. Inequality in Terms of Access to Basic Sanitation Services and Access to Drinking Water

Figure 6 clearly shows that inequality between rural and urban areas is relevant. A total of 15% of the urban population does not have access to basic sanitation, which implies that this population is more prone to diseases. On the other hand, more than 60% of the rural population does not have access to basic sanitation. The same can be seen in the fact that more than 70% of the rural population does not have access to drinking water, which is an indispensable good for human life. It can be said that less than half (23%) of the rural population has access to this precious commodity, while 58% of the urban population benefits from it, i.e., more than twice as much.

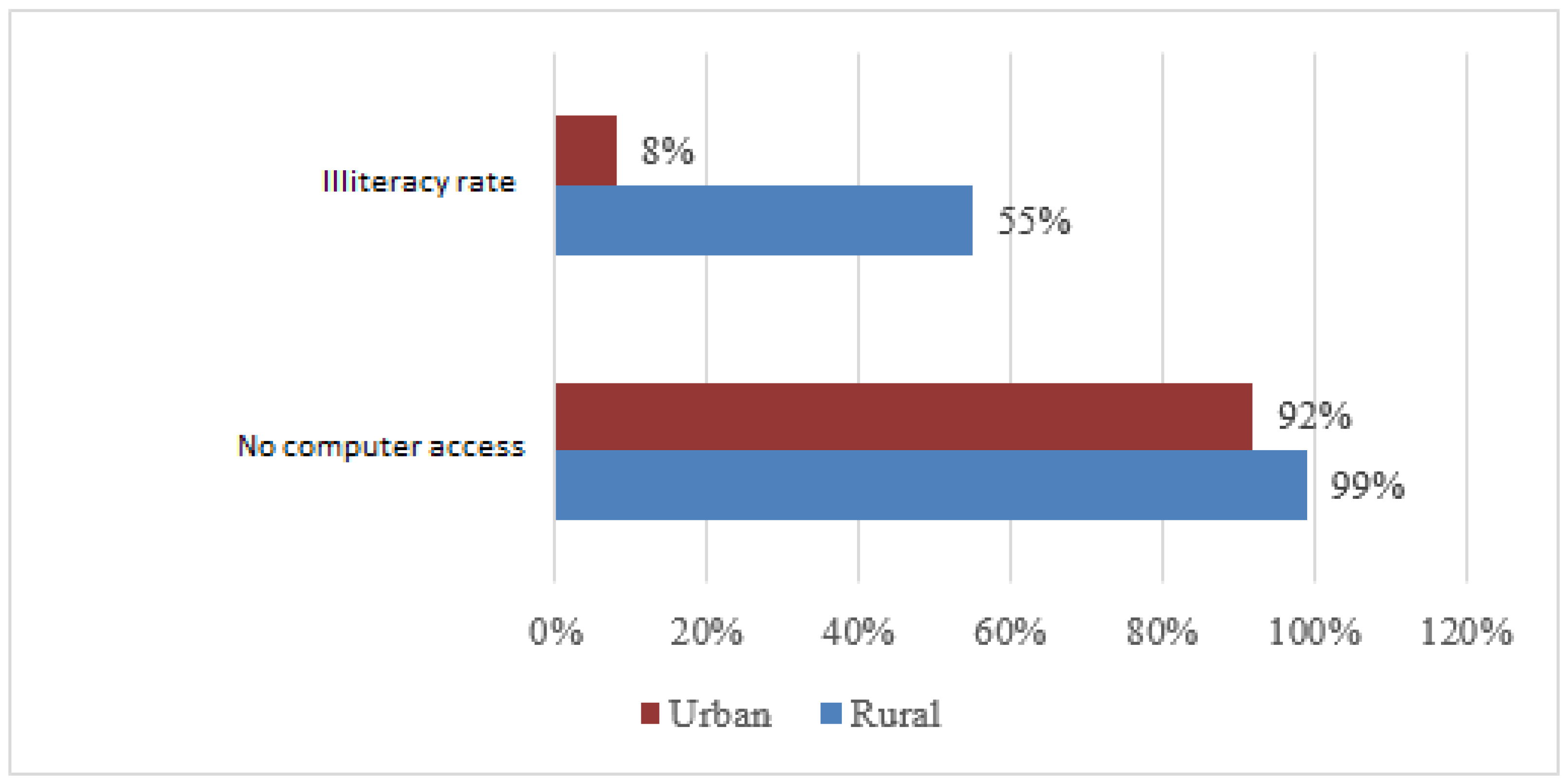

3.6. Inequality in Terms of Access to Computers and Illiteracy Rate

Figure 7 shows that the rural population has an illiteracy rate of 55%, which means that more than half do not have access to information technologies. The rural population also has a rate of no access to computers of 99%, which is practically the majority of the population, i.e., for every hundred people in rural areas, only one has access to a computer. On the other hand, in urban areas, the figures are not as bad, as 92% of the urban population is literate; however, there is a fairly high percentage of non-access to computers an important educational tool.

The figures presented above and the data seen through the INE website show and demonstrate the urgent need for the state to intervene to mitigate the effects of these social inequalities between the countryside and the city. Furthermore, it is observed that in provincial terms the inequality is equal or even greater. To reverse this situation, it is necessary that the State, through its General State Budget policies and public spending, use these means for the development of the countryside so that there is harmonious growth and development.

3.7. Public Investments in Angola

In the previous sub-theme on the determination of per capita income among regions, according to

Silva (

2005, pp. 89–92), it became clear that, in addition to factors, such as level of schooling, level of human capital, etc., investments play a preponderant role in the reduction of social asymmetries and inequalities. For this reason, the Angolan government has been investing in infrastructure throughout the country since 2002.

The importance of investments is illustrated through gross fixed capital formation. During the 2010 period, 30% of public investments went to Luanda, creating more employment and income opportunities in this province compared to provinces in the interior of the country (

Kanyenze et al. 2017, p. 14).

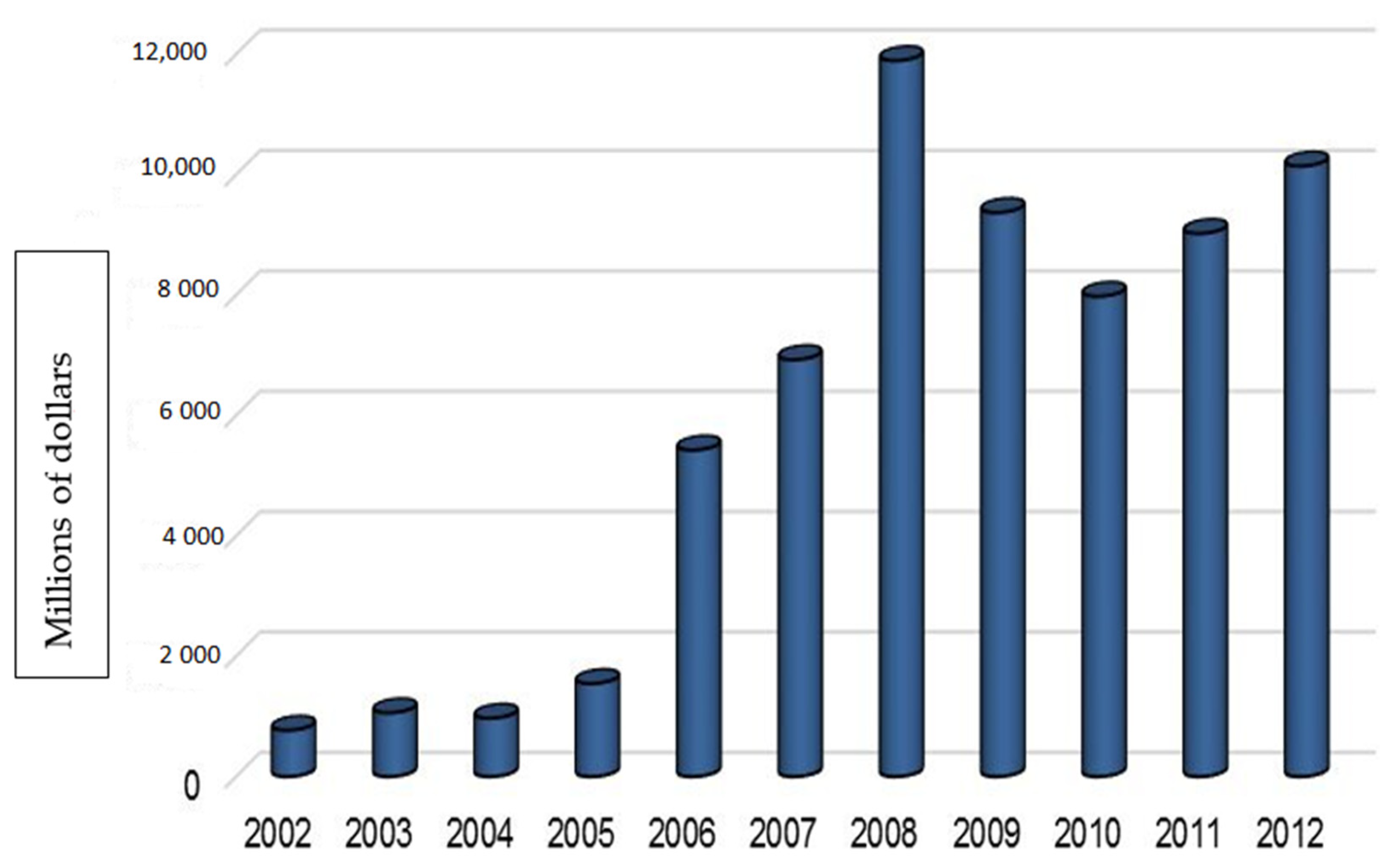

Between 2002 and 2012, the state invested about

$65.1 billion in public works in the country, distributed annually in each province according to its needs.

Figure 8 shows the amounts in millions of dollars disbursed by the Angolan government for the construction of public infrastructure ranging from schools, hospitals, basic sanitation networks, housing, etc. Despite the 2008 financial crisis, investment in public infrastructure remains high (

CEIC 2013).

One of the main challenges of the Angolan State, assumed during the 2008 electoral campaign, was the construction of one (1) million houses by the end of 2012 to cover the housing deficit in Angola and reduce housing asymmetries in comparison with its neighbors and in Africa as a whole. Although many houses have been built, the target is still far from being reached, both in the planned time frame and in the new mandate of the executive (

CEIC 2009).

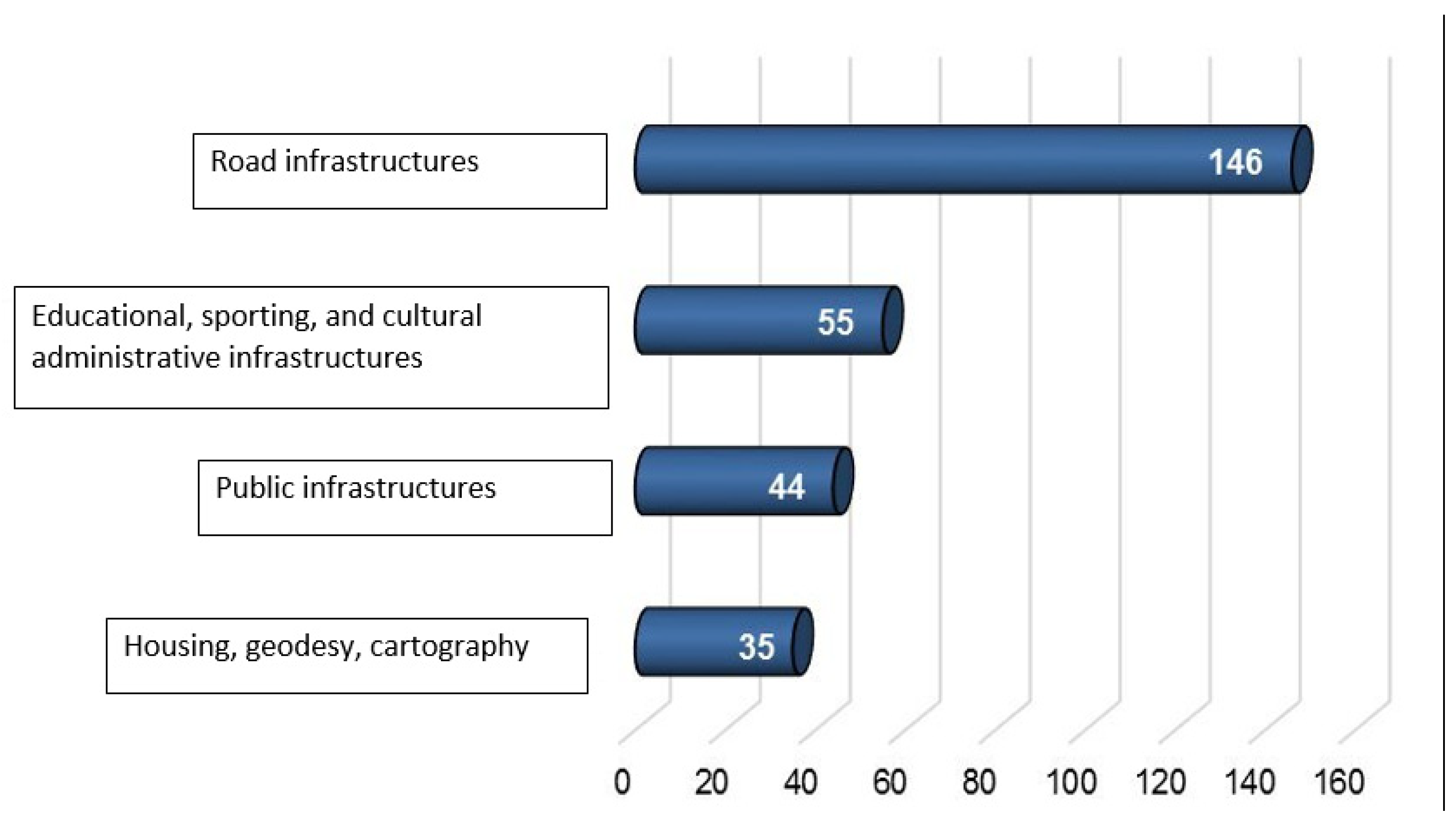

In the 2012 Public Investment Program (PIP)

Figure 9, the sector obtained a total of 280 projects, of which 146 refer to road infrastructure rehabilitation and construction projects (52.14%); 55 projects (19.64%) for the rehabilitation and construction of administrative, educational, sports, and cultural infrastructure; 44 projects (15.71%) for the rehabilitation and construction of public infrastructure; and the remaining 35 projects (12.50) for housing, geodesy and mapping, land management, urban planning, and other programs.

Thus, we can conclude that the importance of public investment, especially in the infrastructure sector, is a permanent driver of economies that have poorly diversified productive structures, are uncompetitive, and have low indexes of intersectoral density. Investment is the oxygen of economies, without which it will be difficult to ensure sustained rates of economic growth and the reduction of asymmetries and social inequalities, which in Angola are reflected more in income redistribution, access to the public education system, housing, etc. This causes many to leave their regions of origin to go to the capital in order to find better living conditions (

CEIC 2011).

3.8. Angolan Provincial Differences on Some Attributes

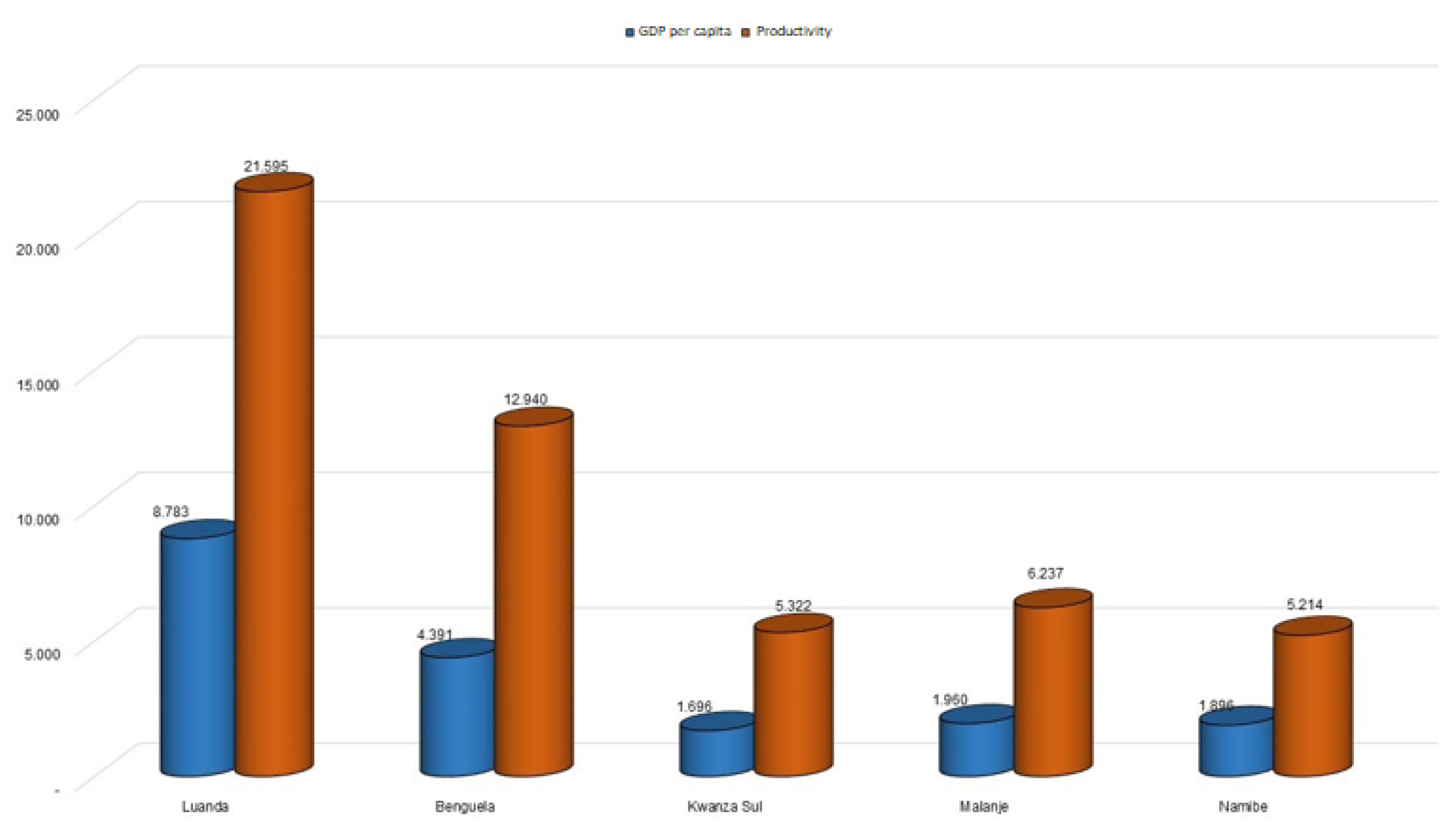

Through the data published by CEIC and INE, it was possible to verify the gigantic differences in some economic indicators in the respective provinces of Angola.

According to a field research visit conducted by students of the Faculty of Economics of the Agostinho Neto University in 2011, it was possible to verify the gigantic differences in some economic indicators in the respective provinces of Angola. Through the data published by CEIC, it was possible to verify these differences, confirming that there are areas completely removed from the benefits of development, attention, and attraction of private and public investors. For investors, return on capital is essential, and they avoid investing in areas where purchasing power is low, the level of final demand is low, productivity is low, and positive externalities are non-existent.

Figure 10 shows some provinces and their economic indicators. Of the small sample of 5 provinces, four are from the coastal zone of the country. Although these provinces, such as Huambo and Huila, are sought after by investors and others, it is indisputable that the greatest interest of investors is concentrated in Luanda and Benguela, and secondly in Cuanza Sul. The GDP per capita and productivity are higher in these cities as are the wages and purchasing power. Thus, the province of Cuanza Sul reveals a great surprise not only for its figures but also for the position it occupies in the country in the indicators collected, as the clear inequality is seen in the interior (

Rocha 2010).

The above graph shows once again the urgent need for the state to reduce inequalities and define a policy for the most remote and affected provinces, creating mechanisms to attract investments and improve the economy.

3.9. Education

In Angola, education is the area that has benefited most from peace, and its results are encouraging for countries in similar conditions. Some of the results are likely to differ due to gaps in statistics as well as regional (provincial) characterization of education. But both the UN Undersecretariat for Education and NGOs involved in education projects and financial institutions agree and praise the efforts made in education by the Angolan government.

According to data from the Ministry of Education, three years after the end of the civil war, in 2005, educational programs at different levels were launched in Angola. At that time, the capital, Luanda, registered the mark of 38 thousand literate people, in addition to children of reading and writing age, in a total population of 11 million inhabitants. The project’s partners were the NGO Alfalit-Angola and the Ministry of Education, with financial support from the United States Agency for International Development. The year 2005 was particularly significant for education in Angola, as the problem of illiteracy began to be tackled more forcefully.

As a result of the educational service development program of the same year, more than 190 schools were rehabilitated. Previously, in 2003, the enrollment rate increased considerably, and this was due to the hiring of 71,000 teachers.

At the secondary education level, the number of technical and professional schools was extended to all provinces and increased in those that already existed. New technical careers were also created and the academic level of the teachers who teach in these institutions was raised.

Higher education also saw positive results with the end of the civil war. Public universities reached several parts of the country and the number of private universities increased. In 2002, there were only four private universities, today there are more than 55; and according to the National Development Plan, the government has estimated that there will be more than 40, with the objective of supporting the accumulation of knowledge and internal competitiveness by increasing the number of public university campuses.

According to official government data, there were 9000 students enrolled in Angolan colleges in 2002. Statistics show that more than 100,000 people study higher education in a population of 32.8 million. For the Secretary of State for Science and Technology and former rector of Agostinho Neto University, Sebastião Teta, these results express well the country’s demand for qualified human resources. Therefore, it is believed that there is a trend to increase the number of university students. In 2020, there were already more than 300,000 people attending university in Angola.

The main problem of education in Angola is the quality of teaching, which is reflected in the school failure rate. To remedy this situation, the government has a program to install and equip 18 teacher training centers throughout the country (one in each province), which will improve the quality of teaching. In addition to these figures, seven schools have been created in the province of Luanda Norte, with a total of 30 classrooms spread over six municipalities; four schools in Lunda Sul, with a total of 17 classrooms spread over three municipalities; three schools in Moxico, with a total of eight classrooms spread over two municipalities; and two schools in Luanda, with 12 classrooms spread over two municipalities. All these schools were built in 2006 and are located in different parts of the country, which contributes to reducing the differences in education in Angola and reducing regional asymmetries. However, although the number of schools has increased in recent years, the supply still does not meet the growing demand.

3.10. Inequalities in Employment and Unemployment

The data show, once again, that the region that gained and benefited the most from peace is undoubtedly Luanda, which contributes little to harmony and national reconciliation. It is in this area and in many others that asymmetries are aggressive, unfair and unequal. Indeed, nearly 50% of the companies and establishments operating in Angola are located in Luanda, a figure that rises to more than 68.3% if the provinces of Benguela and Cuanza Sul are added.

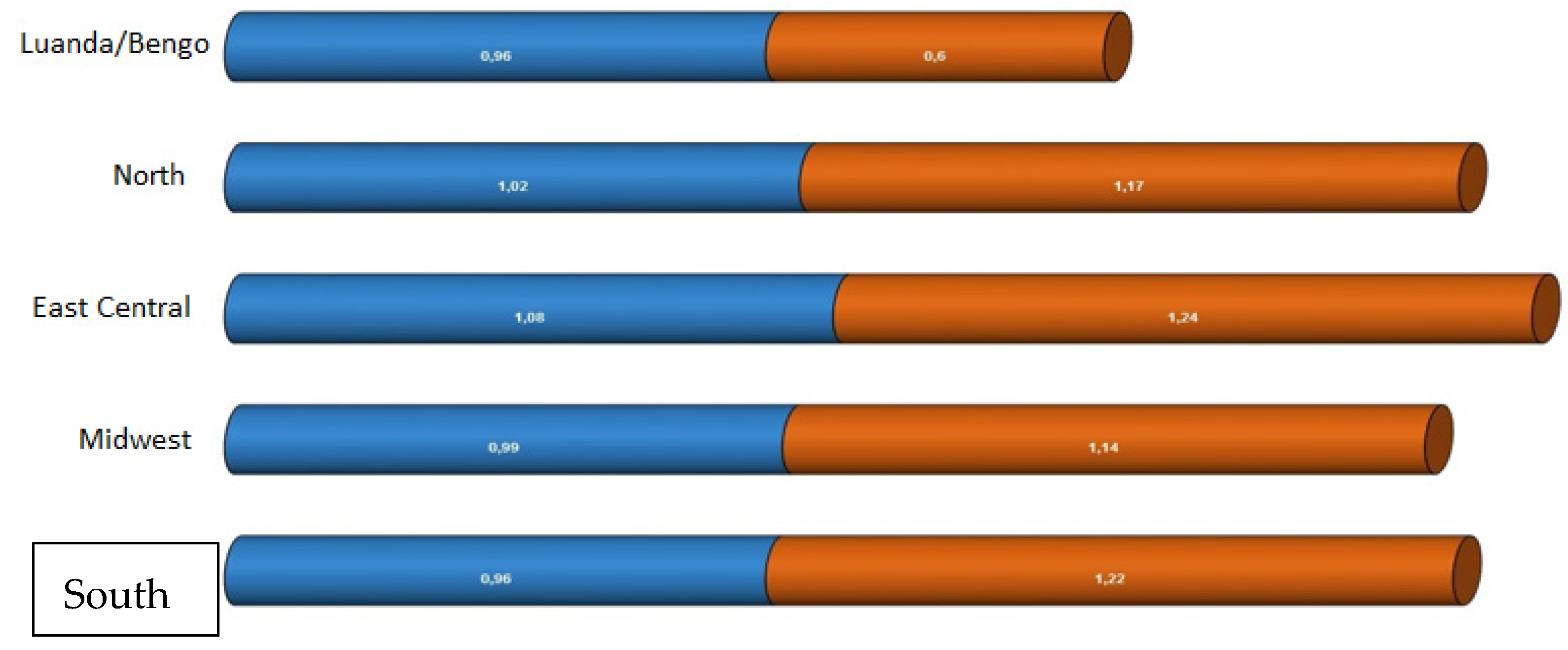

Although from 2007 onwards, the economy began to contract due to the Angolan crisis. Luanda/Bengo was the area or region that created the most employment opportunities due to its capacity to generate work and income, causing active people from other regions to leave their areas to emigrate in order to obtain better conditions of access to education, luxury apartments, etc.

From the point of view of unemployment, the situation is most worrisome, as it reveals that the economy is unable to provide an economic and profitable occupation with social dignity to almost 30% of the working age population. Only with the exception of Luanda/Bengo, all other regions are unable to create employment for the working population. In

Figure 11, the center–east region and the south region have the highest unemployment rates.

In comparison, it is clear that the eastern region, with rates of 1.08 and 1.24, in 2000 and 2007, in relative terms, presents itself as an area with greater problems in generating employment for the economically active population, which means that the unemployment rate in the eastern region can exceed the national unemployment rate. On the other hand, Luanda, which presents a much lower rate in 2000 and 2007, is explained by the emergence of several commercial, technological, and financial industries (

Rocha 2010).

4. Conclusions

After analyzing the theory and related statistics, all these observed asymmetries have been reinforced, generating an ever-deepening gap with less infrastructure, poor access to housing, less education, less work, less employment, less specialization, less productivity, and more migration to large centers, such as Luanda. The asymmetries observed through the variables studied show that the provinces that have been historically exploited and considered target regions have little production of goods and services, precarious security, different financial systems, and high economic and social risk. On the other hand, developed provinces, which have better production systems and lower risks, have fewer inequalities not because they are considered subject regions but because of their geopolitical strategy, and because they are centers of primary production flows.

Throughout the research, the influence of the historical process in the generation of these asymmetries between the provinces of Angola was noted, as, since colonial times, some received investments to achieve development and others did not due to an extremely agro-export vision defined by the colonial system itself, based on the exploitation of resources, cheap labor, and control by the metropolis.

Throughout this period, differences were accentuated, and some provinces focused on agriculture as their only means of subsistence, while others developed. As a result of this colonial dynamic, a disorganization of the social and economic system was observed, resulting in the exploitation of resources and the polarization of politics among various ethnic groups, thus, facilitating Portuguese domination and the accentuated exploitation of the regions as objects.

Reflecting on the theory of subject and object regions, it is clear that, in the constitution of the Angolan provinces, the region was not seen as a subject, and ethnolinguistic proximity was not considered, leading to occupation and a disorganized spatial distribution and leaving its characteristics unnoticed. Moreover, the view of the region as object and subject has overlooked the fact that Angola’s provinces are not mere geographical divisions but, essentially, territorial expressions formed by social groups with a history, consciousness, and political expressions. Another factor that contributed to the consolidation of asymmetries between the provinces of Angola was indeed the war of liberation (the first and the second).

These factors have deepened the inequalities over time, causing a permanent migration of the population to more attractive areas, the abandonment of rural structures, and chaos in the urban environment.

Currently, asymmetries in Angola are far from being reversed because, in order for there to be harmonious growth and development of the territory, human development and welfare, and improvement in the competitiveness of public finances, it is essential to reduce the differences. All this has a high price for the whole country, if we consider, for example, the migratory process between provinces, which can give citizens better living conditions.

Thus, the overpopulation of Luanda in the post-war period is one of the obstacles to the poor quality of life offered by the city to its inhabitants. These conditions could be reversed if the State were to consider planning new areas of investment, which could be channeled into basic infrastructure sectors, such as energy, housing, roads, ports, and airports in the short, medium, and long term. On the other hand, investments in the training of Angolan citizens, with quality formal and informal education, would have to be a priority among the public policies outlined by the government.

The key element in combating asymmetries and regional development is the social organization, i.e., the rupture and separation between subject and object. The region must be considered as a geographical and social space, and its development must be structured and analyzed in terms of the regional factors themselves and the people who live there, rather than through centralized planning.

The asymmetries in Angola are interrelated and generate a tendency for the gap to become increasingly deeper due to the historical factors mentioned above, which makes it difficult to reverse them and achieve sustainable development.