Abstract

Today, migration has become one of the main challenges for humanity. In the last ten years, the percentage of displaced people gradually increased, mainly from the southern hemisphere to the north, in search for better living conditions and, in many cases, forced by risks and instability in their countries of origin. The COVID-19 pandemic, far from minimizing migrations, further exacerbated these processes. In light of this situation, some states passed immigration laws that protect their citizens on one hand, but which violate the fundamental rights of migrants on the other. This article aims to determine the main reasons behind the alarming process of migrant dehumanization. We will verify how these national and supranational laws and decisions represent a move towards securitization through a strategic or adiaphoric process, and how ethics and morals are not at the core of these policies. With these decisions, the suffering and death of migrants generates attitudes of indifference among citizens, who often accept and normalize its occurrence. We suggest revising these public policies on migration from the framework of the ethics of Levinasian alterity and Kantian hospitality.

1. Introduction

Modern capitalism spreads thanks to the mobilization and supply of cheap and specialized labor. According to Sassen (2014), this capitalism is currently in a stage where modern economic austerity and environmental policies generate situations of extreme inequality. Global dynamics of extreme poverty, natural disasters, and armed conflicts created unseen levels of expulsion, especially in the global south, which threaten to displace a growing number of people worldwide. However, it is precisely this constant flow which represents one of the main threats towards the modern idea of nation states, which seeks to achieve full control of the borders. All in addition to the loss of state sovereignty resulting from the global economy imposed by the financial markets, which strictly limit state intervention in this realm.

In its initial stages, it seemed as though globalization created a context of deterritorialization, where the classic concept of borders disappeared along with the notion of a barrier against a foreign enemy. However, the connection between economic and demographic inequality and borders remains—and is even stronger. The clearest examples are the Mediterranean as a maritime border and the terrestrial border between the USA and Mexico (De Lucas 2016). In this sense, as noted by Orjuela et al. (2017), the financialization of the economy, the digitization of production, and the loss of state sovereignty negatively impacted the real economy, as they led to the loss of jobs and increased inequality in the distribution of wealth among countries. As a result, migration flows from countries with a low Human Development Index and GDP intensified towards northern countries, in addition to the forced displacement of refugees.

According to Bauman (2013), globalization is now the most prolific assembly line of human waste or ‘superfluous’ wasted lives. He says that these people are stripped of their heretofore sufficient ways and means of survival, and are considered unfit, unwelcome, or misplaced within an established order. An order that migrants and refugees are a part of, in this sense. As a result, sovereign modern states emerge as the main guardians against the external threat represented by this group of human waste. This paved the way for the process of securitization (Bauman 2016) in which the security industry, justified with exceptional border and migratory control measures that represent a termination of the legal system (Tabernero 2013), is now the key factor to get rid of waste.

However, according to Gutmann (2001), this creates a perverse effect known as the paradox of sovereignty, which says that certain northern states promote certain rights but breach them at the same time. When breaching them, they find a self-justified reason that absolves them from prosecution. In this line, countries that receive migration flows operate under exceptional legal mechanisms which use the law to “legitimise actions that damage and dilute the political and human rights of deterritorialised individuals” (Moreno 2014), allowing natives to preserve their privileged access to a series of social rewards and opportunities (Zanfrini 2007).

Despite these legal mechanisms associated with the migration securitization process, migratory movements have not stopped. In fact, they intensified in recent years as a result, for example, of armed conflicts like in Syria, or political and economic instability like in Venezuela. The emergency situation in which the EU is living since the spring of 2015 does not lie in the threat of invasion or a state of siege, but in the unquestionable risk for desperate people who attempt to obtain a better life, away from hunger, misery, wars, and prosecution in their countries. They put their lives on the line to achieve said goal, and some died (De Lucas 2016).

These deaths, which ultimately become statistics, are met with indifference and are made invisible under the legal umbrella or border control that accepts it as is, without conducting any type of moral assessment. According to Bauman (2016), this leads to one of the main dangers that threaten morals: “adiaphorization”, understood as the group of “stratagems of placing, intentionally or by default, certain acts and/or omitted acts regarding certain categories of humans outside the moral-immoral axis—that is, outside the ‘universe of moral obligations’ and outside the realm of phenomena subject to moral evaluation” (Bauman and Donskis 2015, p. 57). This indifference or moral blindness, as Bauman would call it, paves the way for the dehumanization of immigrants in order to exclude them from the category of legitimate human owners of rights, thus shifting the issue of migration from the field of ethics to the field of security and state of emergency or exception.

In this sense, this article examines the struggle between current politics connected to securitization and morality in the field of migrations, with the former dehumanizing them and the latter humanizing them. Therefore, we propose the inclusion of the ethical and moral dimensions, based on the ethics of alterity of Emmanuel Levinas, the hospitality of Immanuel Kant, the civic virtues of Victoria Camps, and the universal ethics of Adela Cortina, as perspectives for analysis when crafting migration and asylum policies.

2. The Securitization of Migrations, the Dehumanization of Migratory Policies

There is an obsession with security, coupled with a political and institutionalized discourse of fear, claiming the threat of an upcoming terrorist attack, the instability of the welfare state, or the possibility of becoming infected with imported terminal diseases. These are now valid items to legitimize state power and to impose the creation of a complex and sophisticated “security industry” (Bauman 2005). This industry turned natural borders into militarized and securitized spaces that separate useful products from waste. In other words, native people (those inside) from the threat of those who are outside.

In this sense, the term securitization, coined for the first time by Ole Waever in 1995, and more broadly developed by the Copenhagen School of Security Studies, refers to the process whereby a public issue acquires, through discourse, the status of a conventional threat. It thus becomes a security issue, which ultimately validates implementing certain measures (Buzan et al. 1998). This concept, according to Bauman (2016), intends to determine the frequency with which authorities increasingly classify issues and areas that were previously thought to belong to another category of phenomena, as examples of insecurity. After all, Bourbeau (2017) believes it is a process whereby institutional discourse integrates a given problem within the framework of security, which emphasizes police action.

Indeed, the attacks of 11 September 2001 increased hostile emotions, and the attitudes of both governments and their population towards immigration worsened. Meanwhile, the connection between migration and terrorism became stronger with warnings of the risks that this connection could entail for a country’s public and national security (Treviño 2016). In this sense, the American government did not hesitate to activate extraordinary measures (Emmers 2013)1, such as the approval of the USA Patriot Act in 2001, whose regulation addressed the priority of fighting against terrorism and turned migration into an issue of national security. It soon represented a global trend (Alarcón 2011) and was followed by the Law of National Security in 2002, and then by the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which in 2003 also assumed responsibility for the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Subsequently, the Secure Fence Act of 2006 and the Border Security Act of 2010 gave continuity to the securitization process, turning the border into an insurmountable wall. This caused in-transit migrants and refugees to be left at the mercy of violence, acts of harassment on behalf of border officials, and criminal organizations that use the same routes for illicitly trafficking with weapons, drugs, and people.

The election of Donald Trump and his electoral proposal to build a wall along the border with Mexico (there are currently close to 1100 km of wall built on the border between Mexico and the United States of the 3200 km that they share), led to the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) receiving funds to create a new border system. This new system will focus on improving pre-existing facilities and extending the wall by 819 km by late 2020. To do so, the Supreme Court gave the green light for the government of the U.S.A. to redirect a total $2.5 billion from the Pentagon and $3.6 billion more from the Department of Defense to build the wall. Its construction, however, as noted by García (2017), is not Trump’s idea. He is merely following the footsteps of his predecessors in the White House, specifically since the Clinton Administration approved its erection in 1994.

Likewise, the attacks on 11-S were also decisive for the European Commission to revise community legislation on immigration and asylum three months later2 (Arango 2011). In this line, both the European Council in Seville (2002) and the Hague Programme (2004), which replaced the Tampere Programme, ratified the position of common policy to continue fighting against illegal immigration.

In this framework, the securitization process of the EU, formalized with the European Agenda on Migration (2015) and created not only in response to the European refugee crisis, but as a project to manage migratory challenges in later years (De Lucas 2016), was established based on agreements with African countries: the Global Approach to Migration and Mobility, formalized in 2005, the Rabat Process, which began in 2006, and the Khartoum Process, which began in 2014. In this line, as noted by Avallone (2019), all these inter-institutional processes and agreements converge towards the same objectives and share the same political agenda: placing emphasis on closing borders and fighting against immigration defined as irregular. As an example, this led to the new powers acquired by the Frontex agency, whose role, among others, is to coordinate return operations. Frontex also received an increased budget, going from under €100 million in 2010 to €5.6 billion for the 2022–2029 period.

Another noteworthy aspect of the EU’s process of securitization is the strengthening of the external dimension of policies to protect the border and contain migration. This is reflected, for example, in the information provided by the report entitled “Migration Control Industry”, produced by Por Causa (2020). It says that “during the period 2015–2018, 57% (€12,500 million) of the total funding to respond to unexpected arrival of refugees in 2015/2016 was assigned to actions outside of the EU” (p. 4). In this sense, the externalization of borders is relegated mainly to the involvement of the governments of origin and transit in managing and controlling migration flows. According to Zapata and Ferrer (2012), this makes Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Tunisia, and Turkey the external border of the EU. This strategy, which was institutionalized in the Valletta Summit of 2015, conditioned bilateral, regional, and cross-border relations of cooperation between these countries and the EU. It did so by ensuring that these countries receive funds to undertake structural reforms and have preferential treatment when establishing commercial agreements and allocating development aid, in exchange for becoming migration bottleneck of migration containing countries. Morocco is a clear example of success for the EU on the issue of migratory cooperation and is also the country that receives the most development aid from the EU. The Commission granted this country €1.4 billion in aid for the 2014–2020 period through the European Neighbourhood Instrument, but according to the European Court of Auditors, this did not lead to the necessary reforms or to making progress with the expected challenges (Por Causa 2020). Furthermore, according to Avallone (2019), the clearest example of this policy is the agreement that the EU signed with Turkey on 18 March 2016. It was based on repatriating to Turkey irregular migrants and asylum seekers who reached the Greek islands. In exchange, the EU guaranteed, among other items, an economic fund with €6 billion (in two instalments). As a result, the number of arrivals through the Balkan route fell drastically.

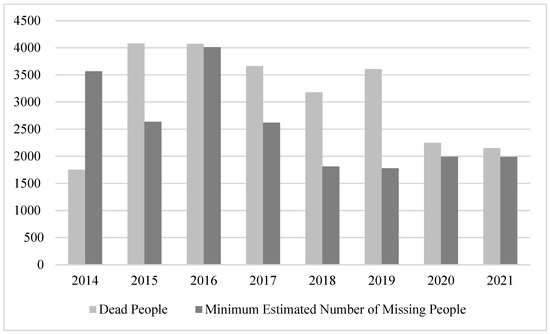

However, migration flows continue, despite an increased number of border controls backed by technological biopolitical mechanisms making migrating a high-risk and tough endeavor. After all, they are a component of the social system of consumer capitalism (Moreno 2014). Furthermore, the number of deaths and disappearances during migratory processes remain the same. In fact, according to data from the Missing Migrants Project (MMP) of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the central Mediterranean route is the deadliest of all. Of the 45,024 people who died or went missing since 2014 (Figure 1), 18,503 lost their lives on this route.

Figure 1.

Dead and missing people in the process of migration by year. Source: Own elaboration from MMP-IOM.

Therefore, it is on these migratory routes where human trafficking mafias operate and where there is a legal void that allows the bodies of people with no rights to continue to pile up. These people have been relegated, using the terminology of Agamben (2003), to the category of Homini sacri, meaning that they have been stripped of all significance and value. This is where the term “necropolitics” of Mbembe (2011) makes sense, when referring to the political model that, according to the author, normalizes the logic of politics of death. In this way, necropolitics sets the mechanisms that establish and maintain control over who can live and who cannot. In connection with migratory policy, the politics of death—or allowing people to die—can materialize as direct attacks towards migrants and refugees. This happened in the Tarajal tragedy in February 2014, where Guardia Civil officers shot rubber bullets at the immigrants in order to thwart their attempt. On the other hand, it can generate conditions in which their lives are threatened, as occurs with the furthering of policies aimed at punishing and criminalizing maritime rescue actions conducted by organizations in the Mediterranean (Moraes et al. 2019). Another very topical example was the events that occurred on the border between Poland and Belarus. Migrants were used by the Belarusian government as weapons of political pressure in response to the sanctions imposed by the EU in the face of repeated human rights violations and repression against the opposition.

3. Migratory Policies, between Politics and Morality

Immanuel Kant, in his essay entitled “Perpetual Peace”, noted the discrepancy between morality and politics, stressing that “taken objectively, morality is in itself practical, being the totality of unconditionally mandatory laws according to which we ought to act. It would obviously be absurd, after granting authority to the concept of duty, to pretend that we cannot do our duty (...). Consequently, there can be no conflict of politics, as a practical doctrine of right, with ethics, as a theoretical doctrine of right.” (Kant 2018, p. 45). In this sense, we find ourselves, as (Bauman 2016) says, in the field of rights and duties. These are related and connected to morality, which aspires to codify them.

Universal ethics and politics understood as a service to others are two key elements that must coexist and support each other in any structure of a democratic state, and especially when producing laws that govern the coexistence of the members of a community or society. Azcárate (1874) insisted on the need for politics to have the same objectives as ethics (theory) and morality (practice). In other words, the virtues of the governor, the legislator and the citizen must be the same, focusing on the idea that the purpose of the state must be the same as the purpose of ethics: human happiness. These are the qualities that these three figures must have: love towards the established regime, heightened expertise in the matters of their position, virtue and justice. However, Hegel and Weber base their thoughts on the opposite idea, considering politics and morality as two different normative systems which are not independent, as they complement each other. They place the political system above morality (Polo 2014).

When dealing with ethics, we must include human values as an axis and foundation of its significance. Failing to do so would entail the immediate appearance of attitudes and behaviors outside the common good. Comins (2015) warns us of the benefits of democratic systems where responsible participation, the pacific settlement of conflicts and the demand for policies in line with the level of responsibility expected from governments, should rely on human values for the sake of everyone. In other words, humanizing public policies from the framework of ethics to prevent the proliferation of attitudes of indifference towards other people’s suffering. Furthermore, if politics is understood to be outside the realm of ethics, this creates the ideal setting for the appearance of immorality, injustice and a clear commitment to the external or private good at the expense of the common good. In other words, necropolitics and dehumanization.

Freeman (1995) says that immigration policies in liberal democracies are characterized by an ongoing competition between liberal politics and the significantly more restrictive behaviors of the population. Democracy also makes it possible for those who do not feel morally obliged to respect these ethics, but do respect the rule of law, to not act ethically when making decisions.

In a society, moral deficiency does not help alleviate the legal voids that exist in the legislative framework of a democratic state. In all likelihood, if there was a positive morality—a complementary and solid combination of ethics and politics—legal voids would not be used for private purposes that evade justice and the common good. From this viewpoint, Victoria Camps, of the Rawlsian approach while also taking into account the tenets of philosopher-politician José Luis López Aranguren, talks about humans as social beings that are not isolated. She describes politics as a service towards others, achieving the desired ethics-politics pairing. Thus, “politics is a dimension of morality, as Aristotle observed. (...) If the purpose of politics is ethics, this means politics for democratic, socio-economic and cultural change, not to hold power or reach a specific position” (Camps 2007, p. 185). Aranguren (1995) says that upstanding politics must simultaneously be ethical and pragmatic. In other words, operational, feasible and achievable.

In line with this thought, Adela Cortina supports the idea that politics with a surplus of universal morality is a great human asset. Politics must focus on its human significance. If this is the path chosen, there would not be a need for so many laws to cover legal voids, because attacks on the common good would not be as frequent. Migratory politics deserve to be considered in this same way. Along with this universal morality, (Cortina 2000) advocates for civic ethics that promote social cohesion and integrate what she calls the ethics of maximum and minimum values along with the law, as these ethics act as a connector between the ethics of a person, of the different realms of social life, such as politics, and law. The combination of ethics, morality and politics is considered in these theoretical cases necessarily inherent to any public migratory policy whose goal is to humanize the process.

4. The Humanization of Migrations

As suggested above, the bases for legislation should rely on ethics and morality, as both entail a commitment to other people, to foreigners, through an empathic process derived from exercising personal civic virtues.

The issue of the dehumanization of migratory processes can have both moral and ethical factors. Both concepts rely on what we call, from a social point of view, a person’s values. From critical traditionalism rooted in communitarianism, Macintyre (1987) defines virtues as the qualities of a person that come to light in certain actions and are geared towards excellence. He says they are based on true and rational judgement, taking into account the context or social structure to which that person belongs. The person develops these qualities freely and they are closely connected to the values that nourish these qualities of excellence. Meanwhile, in Aristotelian philosophy, virtues are also identified as qualities that lead to good for mankind. In other words, an individual who has them will be able to achieve what Aristotle called eudaimonia.

He differentiates between two types of key virtues that are closely connected: the virtue of intellect and the virtue of character. In other words, intelligence and reason necessarily combined with the individual’s qualities of excellence. The former is learnt and the latter is forged, it becomes a habit, displaying it with our natural initial disposition in a specific context as the foundation. From this viewpoint, Aristóteles (2002) says that virtues can be dianoethical, such as intelligence and prudence, and ethical, such as liberality and self-control. The latter ones have a humanizing effect.

From this viewpoint, virtue can have a social component and, from the framework of ethics, become a civic virtue: a virtue subject to the laws of a specific society focused on promoting social justice (Tena Sánchez 2010). Knowledge of these laws, which has a certain connection to the virtue of intellect together with the individual’s virtue of character, both proposed by Aristotle, would allow us to link them to the ethics that regulate people’s behavior towards themselves and others. Thus, Camps (2007) connects virtues with ethics by saying that the idea of virtue was at the core of the first treaties on ethics, which were associated with a certain way of acting. Llano (1999) also touched on this connection between ethics and virtue, stressing their connection to justice towards others and oneself. The proposal of both Llano and Camps is aimed at promoting and conducting processes to humanize society through civic virtues in the framework of ethics.

The contrary entails the proliferation, in a society, of selfish interests at the expense of the common good (Cortina 1999). The absence of these ethics can entail a weakened presence of virtue in the decisions of the members of a society. This can, as Camps (2007) warned, lead to the creation of atomized and dehumanized societies, with no strong social connections, with great difficulties to build a common interest and with no concern for the suffering of others, as can happen with immigrants and refugees. This virtue-justice-ethics connection is especially close to alterity, understood as a reference to the other of two. Levinas (2015) defines it as the ethics of alterity, or ethics with regard to the human face of the other as shaped by oneself, thus allowing oneself to recognize the existence of the other as a human being that is vulnerable.

In this line, alterity represents an explanation of the links established between oneself and others, expressed through a biological and psychological interpretation of others, aid, interaction, the coexistence of oneself with another as an essential factor of human reality, the ethical imperative, justice, etc. (Ruiz 2013; Magendzo 2006). (Arnaiz 1999) makes use of these ethics of alterity, of the face, to perceive the figure of the immigrant and interculturality as a moral category. Pérez de la Fuente (2010) and Irizar (2018) go further by understanding the ethics of alterity as the result of developing civic virtues, seeing it as a certain moral standpoint that becomes clearly validated when learning how a person treats the other.

In this line, Emmanuel Levinas, one of the most noteworthy proponents of the philosophy of alterity, highlights the conceptualization of the term on different levels or planes. Specifically, on metaphysical, religious, individual, intersubjective and ethical planes. In this case, due to the characteristics of this paper, we will focus on the metaphysical, individual, intersubjective and ethical planes. Fernández (2015) says that Levinas, in the metaphysical plane, places alterity at a level that verifies the existence of a radical otherness that goes beyond one’s own identity, thus understanding one’s existence. On an individual plane, alterity is part of one’s own identity, of our personality, which is the result of diverse events and moments lived in a unique and non-transferable way.

Intersubjectivity is another essential plane, drawing from the idea that language and communication make it possible to open up to alterity, as the word we hear from the other requires an answer from oneself as an ethical imperative. The ethical plane of Levinas’ philosophy of alterity is the one we can more closely associate with the humanization of migratory processes. This is what the author calls the ethics of alterity. Drawing from the Levinasian principle, in this plane we perceive the other as an alterity that is not owned and cannot be owned, thus respecting its dissimilarity and specificity. Ethics emerge from confronting the face of the other and from the attitude when receiving the communication or message that the face sends us. These ethics of alterity interrelate all other planes, as “becoming aware of the alterity of the other, and of my own constituent alterity, initiates a new project of interpersonal relationship based on dialogue, respect, tolerance and accepting differences—not just similarities” (Fernández 2015, p. 424). Olmos (2018) explains through a study on alterity, migrations and virtual social networks, that there is a highly problematic representation of migrations, with an increasing amount of openly racist statements in public speeches, and with technology helping to spread them.

Meanwhile, from Kant’s approach (Kant 2018), virtue is understood as prioritizing the common good over the personal good, without taking into account what other people do. Thus, one prioritizes personal gain, with people using their participation to achieve the common good if everyone else does (cooperation), whereas the second prioritizes the common good over personal gain regardless of whether they do so or not (virtue). What stands out in this relationship between virtue and cooperation is that the latter can boost the former, or that altruism and solidarity can facilitate the same virtue. This relationship is closer to the Kantian approach, as we saw above. It entails that a person’s empathic capability is what allows the altruistic action, and thus individual virtuosity, which can be very beneficial when humanizing migratory processes and public policies.

From the Kantian viewpoint of hospitality, Immanuel Kant, in his book Perpetual Peace, presents hospitality as a right of the foreigner or migrant to not be treated in a hostile way by the members of the state they are entering. He frames it as a right of access of the migrant to be received in society as a human being, by virtue of being a co-owner of the world in which nobody initially has more rights over any given territory than anyone else (Kant 2018). The imminent transit of people between different states is founded on these observations, which implies that a foreigner or migrant who passes through a foreign territory generates a right to hospitality, which makes cosmopolitan coexistence possible (Guerra González and Matías 2018).

Resuming the viewpoint of civic virtues, this represents a personal attitude that takes place thanks to the social relationships that the person establishes with the context in which they live. These civic virtues do not only produce a personal benefit, but a common good that requires the commitment and ethical participation of a certain political community or society. They can also be optimized through civic and coordinated education between school and family, which motivates the person to implement them. From these premises, the concept of active citizenship can be framed as an element that promotes or favors these socially accepted individual attitudes or behaviors. Tena Sánchez (2010) establishes a comparison between virtue, altruism and selfishness as motivating factors to take a specific action. Thus, the author leans on Tocqueville, framing it within the idea that individual interest is attained by cooperating to achieve the common good if everyone else does. In other words, conditioned cooperation.

Our societies are currently immersed in a humanitarian and pedagogical crisis that leads to the proliferation of imbalances and contradictions as a result, mainly, of a tendency towards the disappearance of the moral and ethical ethos from people’s lives (Duch 2001). As a result of this situation, migrants who flee from misery and death are labelled as superfluous, and thus become a heavy load for the survival of the system. The immediate consequence is that citizens are instilled with a powerful logic whereby the suffering of the other is accepted and allowed as a natural occurrence of human nature. This is where the argument of compassion or responsible solidarity as an ethical requirement becomes necessary to prevent our societies from becoming ruthless (Mínguez Vallejos et al. 2018; Sachs 2012). This creates the need for humanism understood as ethical and democratic ideals that inspire people to fight injustice, to create solidarity from the national and ethnic borders and other social divisions. This inclusive aspect is reflected in the “no human is illegal” activist slogan that condemns all criminalization and dehumanization when dealing with refugees and migrants (Coene 2021).

The first thing we must know is the role of a citizen in a political community or a specific state. Cortina (2001) says that according to Hobbes, the state is not created in a natural way. Instead, it is created by contract, whereby a group of people coexist following agreements of mutual respect or policies whose purpose is to regulate their actions within this community. In other words, an agreement that prioritizes the common good. Arendt (2001) understands politics or the agreement as an unavoidable necessity for human life, from both an individual and social point of view. People are not autarchic; they depend on the existence of others, and everyone must be concerned for their well-being in order for there to be a better coexistence. This way, we could consider that this agreement for coexistence would imply an ethical commitment of all the members who comprise the state, with the goal of advancing towards continued social improvement with their actions. Actions which derive, in many cases, in the common good.

Weber (1984) says that social action takes place when there is a minimum connection between the actions of each person and those of others. Rawls (1996) says that the consequence of these actions could be framed within the concept of social cooperation, which is guided by publicly recognized rules and procedures related to equity. We could understand social cooperation as the actions of a member of the community that are governed by regulatory framework, such as the migratory laws of each state, agreed on from a viewpoint of equity, and with each member accepting the responsibility they have towards everyone else. However, while commitment and cooperation are necessary, so is addressing the need of morality from a set of dimensions that could be grouped, as Cortina (2001) says, in the ethical dimension.

It is worth recalling that migration is the movement of individuals or groups of humans from an issuing country, established as a state or nation, which defines their nationality, national identity, and legal identity. That houses them as their country of origin. This issuing country offers citizens to another country, which receives them as foreigners (Parra and Cantero 2021). This is where we could place the need for the members of a state to empathize with people who have had to leave their homes and countries to search for a dignified life, due to the possibilities of progress and/or for personal security. In other words, to humanize the migratory processes of human beings from an ethical commitment of the citizens. The dehumanization of the migratory process takes place when transit migrants face difficulties such as discriminatory practices and abuses by private individuals, by those who traffic with people, by organized crime groups, and even by government officials who can extort them (Cepeda et al. 2021).

In addition to the dehumanization, there is the inequality and stigmatization of migrants as obstacles that are hard to get rid of, which leads to them not being recognized as citizens (Santos Rego et al. 2017). Following the train of thought of Levinas, we could say that when we categorize the other, the migrant, as a security issue, we are taking away their face (Bauman 2011; Dussel 1999). After stripping them of their face, we take away their humanity. The migrant becomes a legitimate target of security measures, declared indifferent or neutral from an ethical perspective (Santos Rego et al. 2017). This is where the presence of the Levinasian ethics of alterity and Kantian hospitality, which arise from the very civic virtues of the citizens, become necessary. The best quality of a citizen, their virtues, placed at the service of the common good in the framework of a morality that recognizes the other (the migrant), is what would make it possible to humanize migration flows. In other words, transforming the commitment of citizens and state with migrants through the ethics of alterity, which is becoming increasingly urgent in the humanitarian intervention of migrations (Sager 2019; Collins 2021).

5. Conclusions

For decades, globalization has gradually turned into a process where respect for a person's idiosyncrasy becomes less and less important. This has entailed that, in some cases, migrants become human waste. They are considered trash, or even a threat for a state’s security. This caused the proliferation of public policies that tend to securitize the issue of immigration, where the value of immigrants is relegated to the background, and the indifference towards deaths caused by migratory processes is exempt from all moral evaluation.

The numerous laws and procedures implemented mainly since the terrorist attacks in 2001 in the United States and Europe, as Agier (2008) says, led to the consolidation of the distancing between two increasingly reified global categories: on one hand, a world that is visibly healthy and clean; and on the other, an invisible world full of waste. These policies exhibit a concerning lack of ethical and moral bases that has led, through adiaphorization, to a constant and alarming process of migrations. As De Lucas (2016) says, what is at stake is not to solve a humanitarian issue, but to respond to a breach of the legal duties relative to guaranteeing basic fundamental rights: the right to asylum and the right to live. In this sense, the deaths caused by the drama of migration cannot and must not simply be a statistical piece of data, an isolated number... they are people with names and surnames. The political and legal factors that are responsible for these losses of human lives must be investigated.

Borders are now insurmountable barriers whose immediate consequence has been to place migrants and refugees at the mercy of violence, acts of harassment on behalf of border officers and criminal organizations. Closing our eyes to what happens outside the borders while allocating funds, through development cooperation, to countries that issue migration flows and also staunchly defending human rights in the societies that receive said flows, makes us complacent with these events. These behaviors are contributing to the migratory processes losing their human nature and entering the dangerous process of dehumanization, where people lose all value. In this sense, Agier (2008) expresses it the following way: “It is even possible that, at the same time, any sense of bad conscience towards the condemned part of humanity would be lost: all that is needed for this is that the movement of bio-segregation already under way should continue, creating and freezing the identities sullied by war, violence and exodus, as well as by disease, poverty and illegality. The bearers of these stigmata could be kept decisively at a distance in the name of their lesser humanity, even a dehumanization that is both physical and moral” (pp. 60–61).

This analysis of behaviors and public policies encourages us to propose the ethics of alterity of Levinas and the hospitality of Kant, from the educational reinforcement of civic virtues, as essential axes to create and approve migratory public policies that enhance and humanize the significance and human treatment of migrants. Addressing migration processes from the framework of morals that humanize them, instead of turning to securitization and adiaphorization, entails rightfully perceiving migrants as human beings with dignity.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, A.C.-L. and C.N.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Católica de Valencia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Figure 1. Dead and missing people in the process of migration by year. Source: Own elaboration from MMP-IOM. Data source: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean, accessed on 11 February 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This change in how migrations were governed was not really a novelty, as in the 1990s there were already actions aimed at preventing mobility through deterrence by militarizing the border, such as the following operations: “Hold The Line” in Texas (1993), “Safeguard” in Arizona (1995) and “Gatekeeper” in California (1994). The latter, also known in Spanish as “Operación Muerte” (Operation Death), is believed to have led to the death of 8000 people from its implementation until 2013. |

| 2 | It is worth noting that the management and control of migration flows is a priority in the community’s political agenda since the beginning of the EU. This can be seen in the Maastricht Treaty (1992), where immigration was included in the third pillar, “Justice and Home Affairs” together with issues related to terrorism and delinquency, and especially in the conclusions of the Tampere Summit (1999), which laid the foundations for common policy on asylum and migration. |

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2003. Stato D’eccezione. Homo Sacer II. Torino: Bollati e Boringhieri. [Google Scholar]

- Agier, Michael. 2008. On the Margins of the Word. The Refugee Experience Today. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, Rafael. 2011. La política de inmigración de Estados Unidos y la movilidad de los mexicanos (1882–2005). Migraciones Internacionales 6: 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Arango, Joaquín. 2011. Diez años después del 11-S: La securitización de las migraciones internacionales. Vanguardia Dossier 41: 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 2001. ¿Qué es la Política? Barcelona: Pensamiento contemporáneo 49. Ediciones Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Aristóteles. 2002. Ética a Nicómaco. Translated by María Araujo y Julián Marías. Madrid: Clásicos Políticos. [Google Scholar]

- Arnaiz, Graciano R. 1999. Ética de la alteridad y extranjería. Reflexiones desde el multiculturalismo. Moralia 22: 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Avallone, Gennaro. 2019. La política europea de control de las migraciones. In Asilo y Refugio en Tiempos de Guerra Conta la Inmigración. Edited by Natalia Moraes and Héctor Romero. Madrid: Catarata, pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Azcárate, Patricio. 1874. Obras de Aristóteles: Política. Madrid: Medina y Navarro. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2005. Ética Posmoderna. México: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2011. Daños Colaterales. Desigualdades Sociales en la era Global. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2013. Vidas Desperdiciadas. La Modernidad y sus Parias. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2016. Extraños Llamando a la Puerta. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt, and Leonidas Donskis. 2015. Ceguera Moral. La Pérdida de Sensibilidad en la Modernidad Líquida. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Bourbeau, Philippe. 2017. Migration and Security: Key debates and research agenda. In Handbook on Migration and Security. Edited by Philippe Bourbeau. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Buzan, Barry, Ole Waever, and Jaap de Wilde. 1998. Security: A New Framework for Analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Camps, Victoria. 2007. Educar Para la Ciudadanía. Sevilla: Fundación ECOEM. [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda, Luis Rubén Díaz, Amy Reed-Sandoval, and Roberto Sánchez Benítez. 2021. Ética, Política y Migración. México: Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez. [Google Scholar]

- Coene, Gily. 2021. Towards a Radical Politics of the Human. In Migration, Equality & Racism. Edited by Ilke Adam, Tuné Adefio, Serena D’Agostino, Serena Schuermans and Florian Trauner. Brussels: ASP editions-Academic and Scientific Publishers, pp. 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Francis L. 2021. Migration ethics in pandemic times. Dialogues in Human Geography 11: 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comins, Irene. 2015. La ética del cuidado en sociedades globalizadas: Hacia una ciudadanía cosmopolita. THÉMATA 52: 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Adela. 1999. Ciudadanos del Mundo. Hacia una Teoría de la Ciudadanía. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, Adela. 2000. Ética y política: Moral cívica para una ciudadanía cosmopolita. ÉNDOXA: Series Filosóficas 12: 773–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Adela. 2001. Alianza y Contrato. Política, Ética y Religión. Madrid: TROTTA. [Google Scholar]

- De Lucas, Javier. 2016. Mediterráneo: El naufragio de Europa. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- Duch, Lluís. 2001. La Educación y la Crisis de la Modernidad. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique. 1999. Sensibility and Otherness in Emmanuel Levinas. Philosophy Today-Michigan 43: 126–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmers, Ralf. 2013. Securitization. In Contemporary Security Studies. Edited by Alan Collins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Olaya. 2015. Levinas y la alteridad: Cinco planos. Brocar. Cuadernos de Investigación Histórica 39: 423–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Gary P. 1995. Modes of Immigration Politics in Liberal Democratic States. International Migration Review 29: 881–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Jacobo. 2017. Al nuevo muro de la vergüenza le faltan 2000 kilómetros. El País. Available online: https://elpais.com/internacional/2017/01/25/mexico/1485378993_672715.html (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Guerra González, María del Rosario, and Maribel Sánchez Matías. 2018. ¿Es posible pensar la migración y el refugio desde la hospitalidad Kantiana? REMHU: Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana 26: 205–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann, Amy. 2001. Introduction. In Human Rights, as Politics and Idolatry. Edited by Amy Gutmann. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Irizar, Liliana B. 2018. Cuando se corrompe el carácter… sobre la crisis de la justicia y la necesidad de las virtudes cívicas. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Jurisprudencia 367: 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 2018. Hacia la paz Perpetua. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 2015. Ética e Infinito. Madrid: Antonio Machado Libros, vol. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Llano, Alejandro. 1999. Humanismo Cívico. Barcelona: Ariel Filosofía. [Google Scholar]

- López Aranguren, José L. 1995. Ética y Sociedad. Madrid: Trotta, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, Alasdair. 1987. Tras la Virtud. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Magendzo, Alasdair. 2006. El Ser del Otro: Un sustento ético-político para la educación. Polis. Revista Latinoamericana 15: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mbembe, Achille. 2011. Necropolítica. Madrid: Melusina. [Google Scholar]

- Mínguez Vallejos, Ramón Francisco Rosario, Baldomero Eduardo Romero Sánchez, and Marta Gutiérrez Sánchez. 2018. La alteridad como respuesta educativa frente a la exclusión social. Revista Complutense de Educación 29: 1237–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, Natalia, Elena Gadea, and Andrés Pedreño. 2019. Expulsiones, excepcionalidad y necropolítica. In Asilo y Refugio en Tiempos de Guerra Conta la Inmigración. Edited by Natalia Moraes and Héctor Romero. Madrid: Catarata, pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Hugo César. 2014. Desciudadanización y estado de excepción. Andamios 11: 125–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olmos, Antonia. 2018. Alteridad, migraciones y racismo en redes sociales virtuales: Un estudio de caso en Facebook. REMHU: Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana 26: 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Orjuela, Luis Javier, Fabrício H. Chagas-Bastos, and Jean-Marie Chenou. 2017. El incierto “efecto Trump” en el orden global. Revista de Estudios Sociales 61: 107–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, Roberto, and Víctor Cantero. 2021. Objeciones éticas al nacionalismo metodológico en las ciencias sociales y en política basadas en los derechos humanos. In Ética, Política y Migración. Edited by Luis R. Díaz, Amy Reed-Sandoval and Roberto Benítez. Ciudad Juárez: Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, pp. 17–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez de la Fuente, Óscar. 2010. Sobre las virtudes cívicas. El lenguaje moral del republicanismo. Derechos y Libertades 23: 145–81. [Google Scholar]

- Polo, Miguel A. 2014. Ética y Política. Hitos Históricos de una Relación. Cuadernos de Ética y Filosofía Política 3: 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Por Causa. 2020. Migration Control Industry. Available online: https://porcausa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Migration-Control-Industry-1-Who-are-the-paymasters.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Rawls, John. 1996. El Liberalismo Político. Madrid: CRÍTICA. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, Miriam. 2013. Un Cementerio de Muertos sin Nombre. ABC. November 25. Available online: https://www.abc.es/espana/20131025/abci-inmigrantes-muertos-tarifa-201310241408.html (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Sachs, Jeffrey. 2012. El Precio de la Civilización. Madrid: Círculo de Lectores. [Google Scholar]

- Sager, Alex. 2019. Ethics and Migration Crises. In The Oxford Handbook of Migration Crises. In Cecilia Menjívar. Edited by Marie Ruiz and Immanuel Ness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 589–602. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Rego, Miguel Á, Lluis Ballester Bagre, and Cristóbal Ruiz Román. 2017. Migraciones y Educación: Claves Para la Reconstrucción de la Ciudadanía. Murcia: Seminario presentado en la Universidad de Murcia. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, Saskia. 2014. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero, Carlos. 2013. Seguridad y Frontera. La externalización del confín y de la responsabilidad securitizadora. Paper presented at XI AECPA Conference, Sevilla, Spain, September 19. [Google Scholar]

- Tena Sánchez, Jordi. 2010. Hacia una definición de la virtud cívica. Convergencia, Revista de Ciencias Sociales 53: 311–37. [Google Scholar]

- Treviño, Javier. 2016. De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de la securitización de la migración internacional en México? Una crítica. Foro Internacional 56: 253–91. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1984. La Acción Social: Ensayos Metodológicos. Barcelona: Ediciones Península. [Google Scholar]

- Zanfrini, Laura. 2007. La Convivencia Interétnica. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata, Ricard, and Xavier Ferrer. 2012. Las fronteras en la época de la movilidad. In Fronteras en Movimiento. Edited by Ricard Zapata and Xavier Ferrer. Barcelona: Ediciones Bellaterra, pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).