Poverty Risks after Relationship Dissolution and the Role of Children: A Contemporary Longitudinal Analysis of Seven OECD Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background: Poverty, Relationship Dissolution, and Social Policy

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Dependent Variable

3.2. Independent Variables

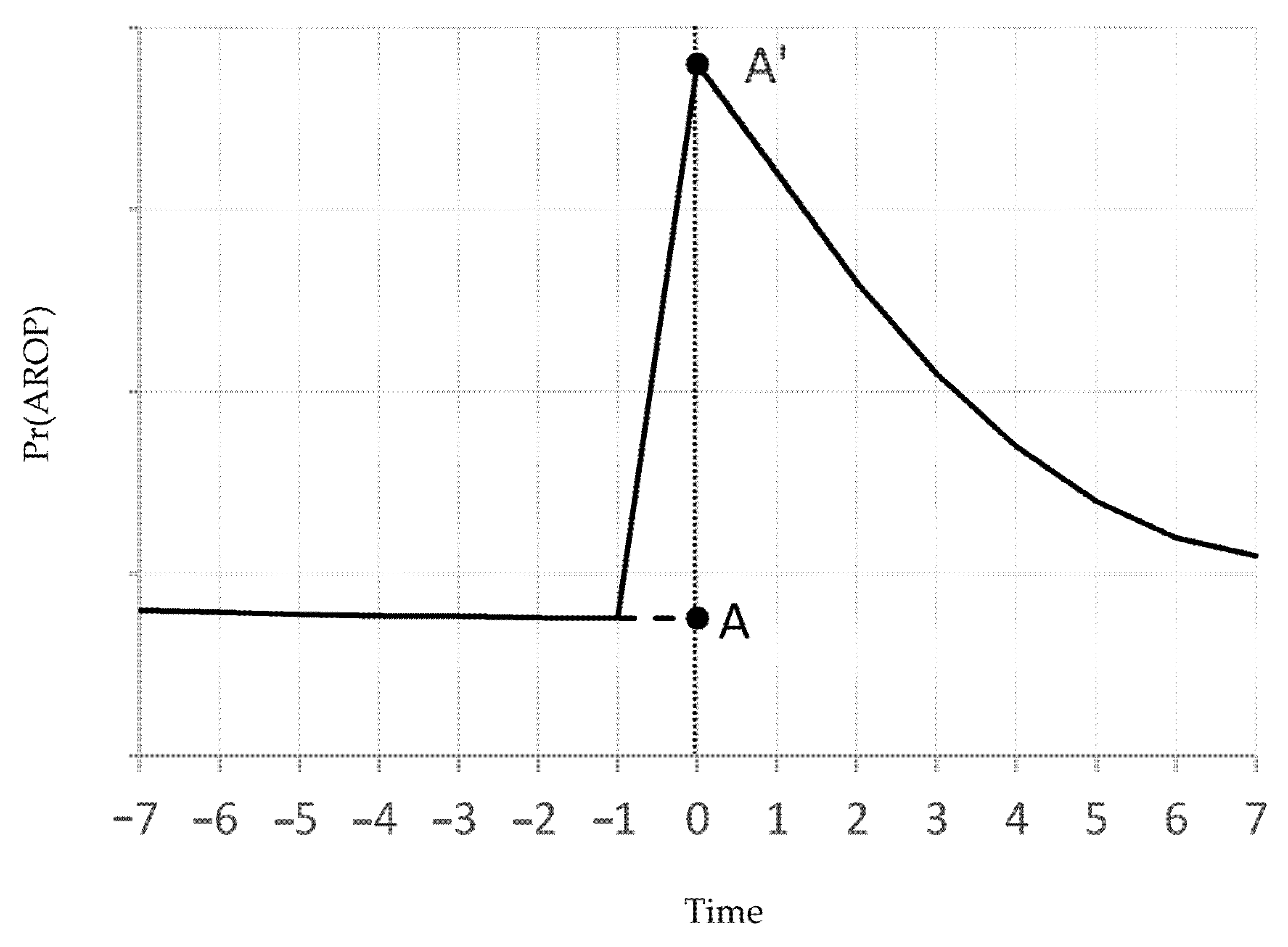

Time

3.3. Covariates

3.4. The Models

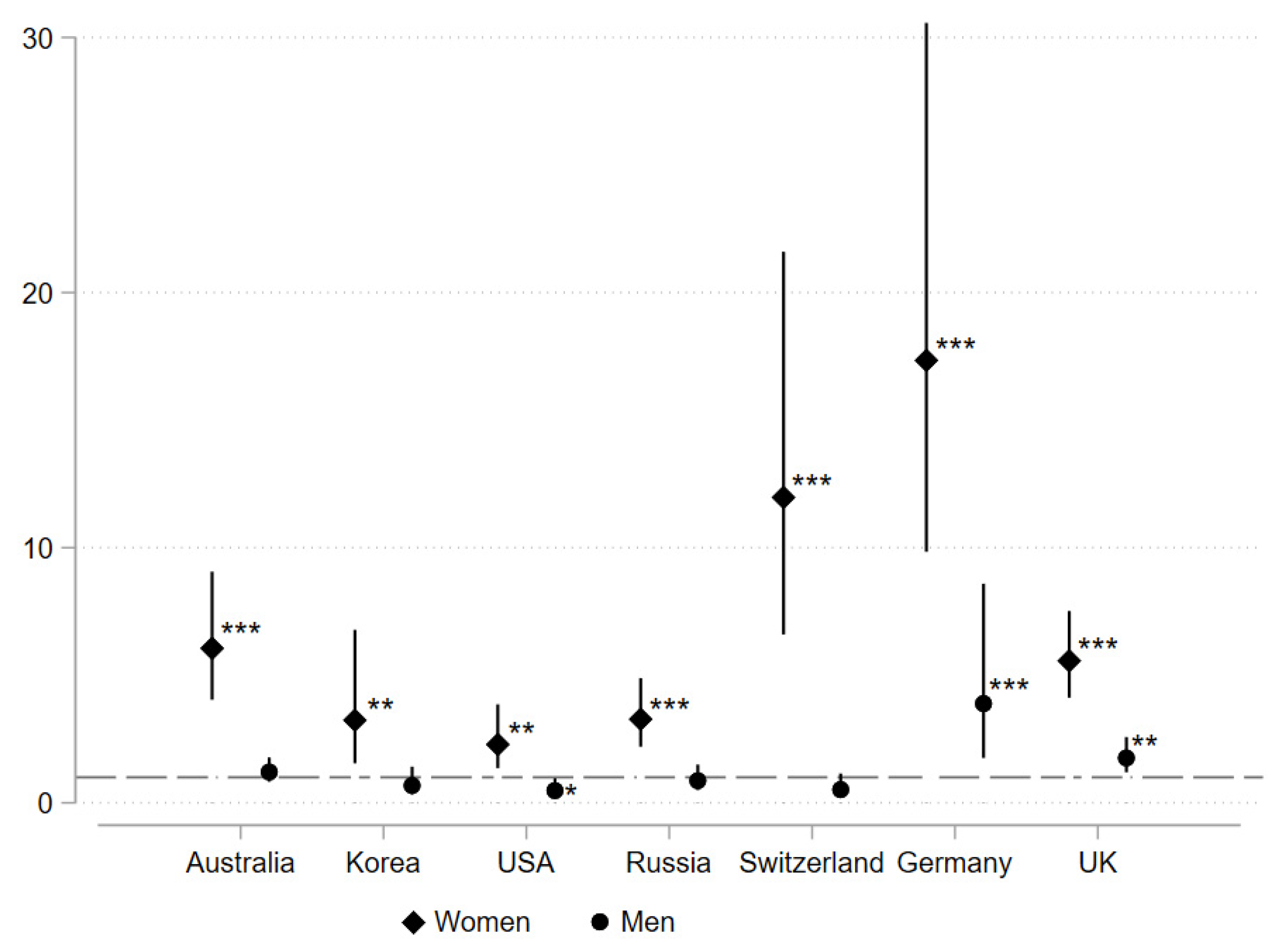

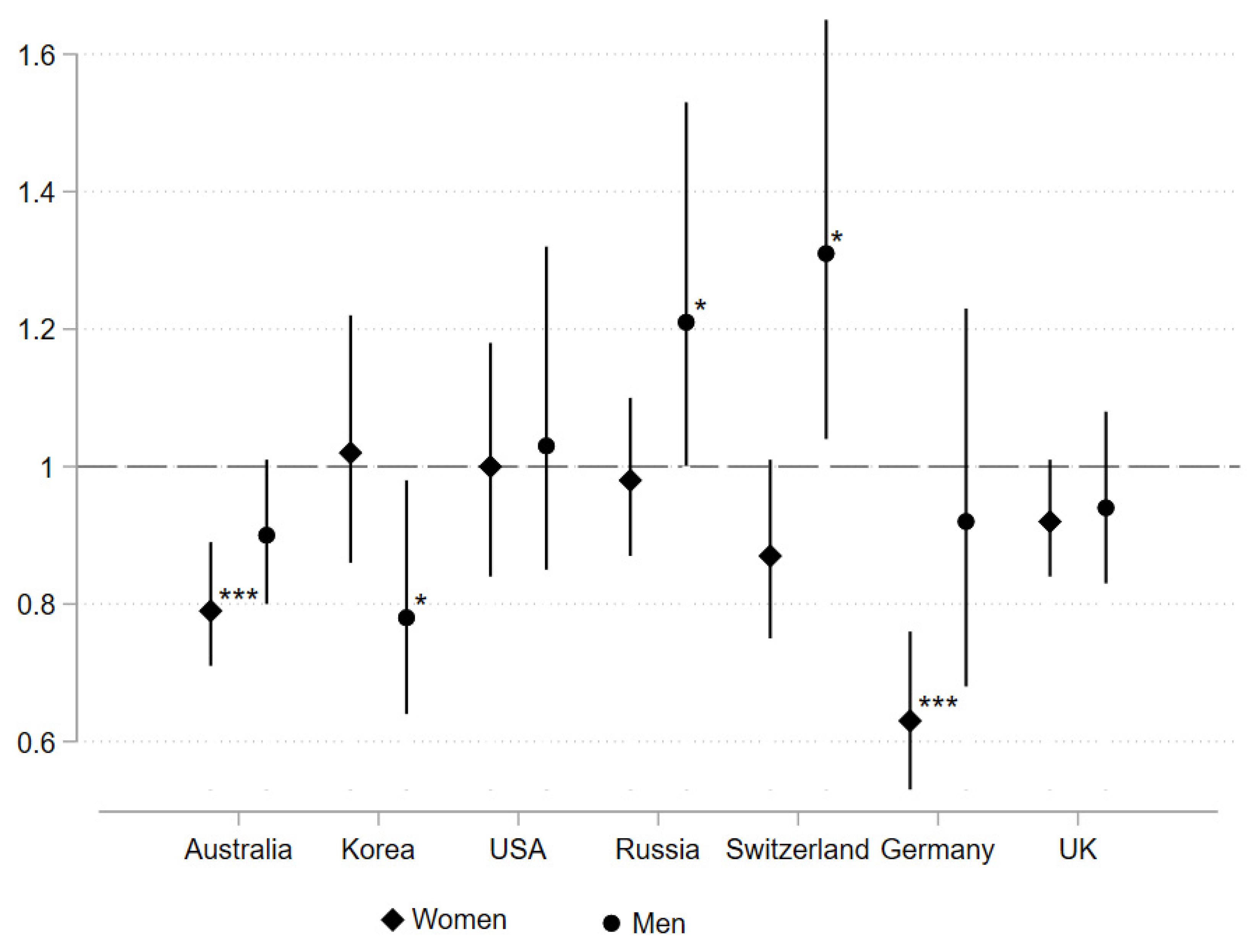

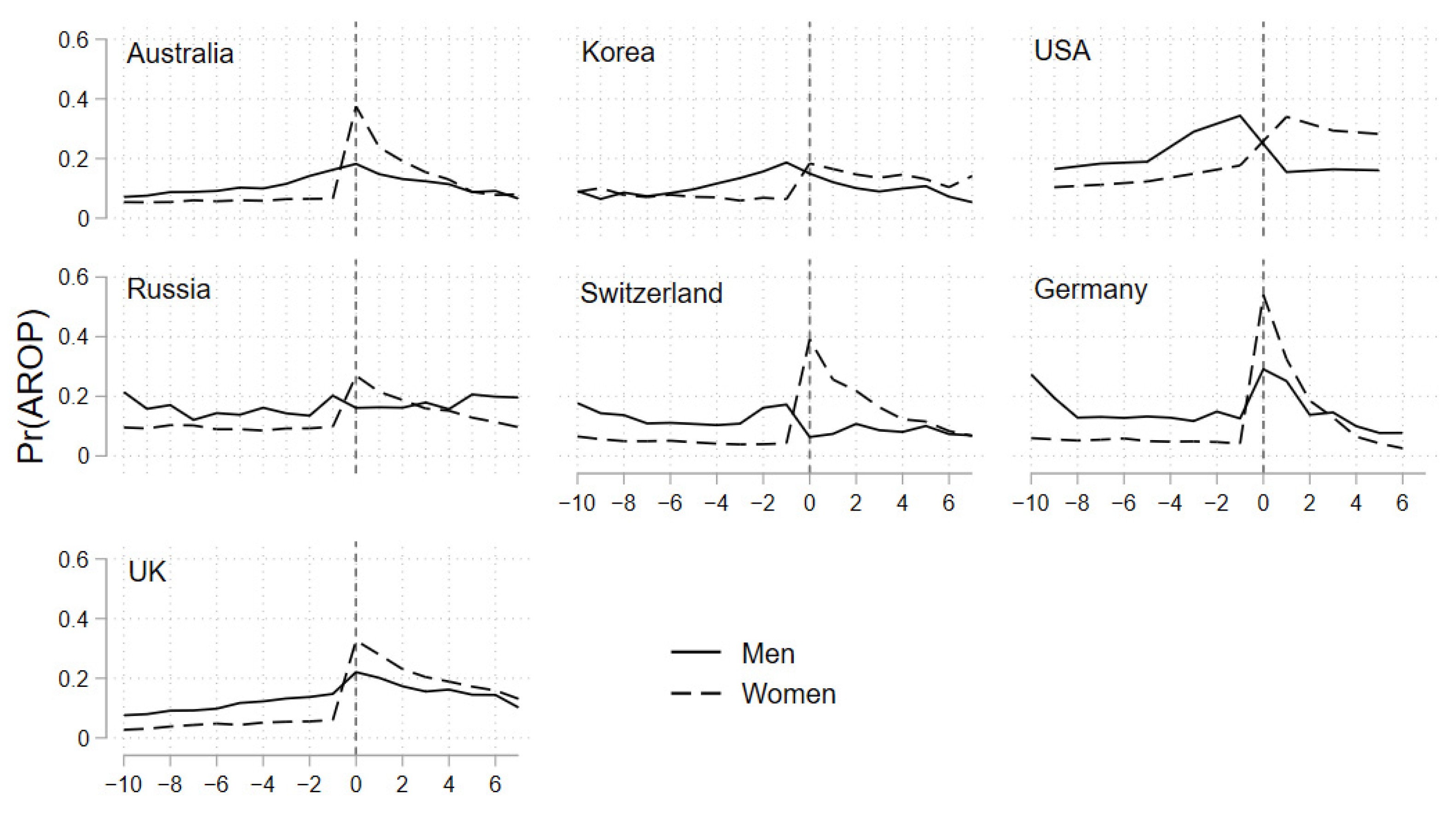

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled | Pooled | Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Prior to separation | ||||||

| Slope | 0.992 | 0.975 | 0.928 | 0.792 ** | 0.951 | 0.785 ** |

| (0.013) | (0.018) | (0.055) | (0.065) | (0.057) | (0.065) | |

| Slope x Women | 1.019 | |||||

| (0.023) | ||||||

| Slope x Country | ||||||

| Australia | 1.072 | 1.273 ** | 1.042 | 1.278 ** | ||

| (0.073) | (0.111) | (0.072) | (0.112) | |||

| Korea | 1.021 | 1.377 ** | 0.949 | 1.331 ** | ||

| (0.079) | (0.135) | (0.076) | (0.133) | |||

| USA | 1.125 | 1.274 * | 1.097 | 1.282 * | ||

| (0.081) | (0.122) | (0.080) | (0.124) | |||

| Russia | 1.017 | 1.175 | 0.989 | 1.190 | ||

| (0.070) | (0.112) | (0.070) | (0.114) | |||

| Switzerland | 1.045 | 1.092 | 0.999 | 1.117 | ||

| (0.079) | (0.105) | (0.078) | (0.110) | |||

| UK | 1.147 * | 1.285 ** | 1.123 | 1.301 ** | ||

| (0.076) | (0.115) | (0.076) | (0.117) | |||

| Children in HH | 0.219 ** | 1.484 | ||||

| (0.115) | (1.055) | |||||

| Children in HH x Country | ||||||

| Australia | 4.007 * | 0.836 | ||||

| (2.346) | (0.625) | |||||

| Korea | 2.103 | 0.409 | ||||

| (1.437) | (0.352) | |||||

| USA | 4.117 * | 1.264 | ||||

| (2.667) | (1.041) | |||||

| Russia | 4.942 ** | 1.118 | ||||

| (2.936) | (0.884) | |||||

| Switzerland | 3.993 * | 9.996 ** | ||||

| (2.617) | (8.878) | |||||

| UK | 5.659 ** | 1.552 | ||||

| (3.218) | (1.167) | |||||

| Postseparation | ||||||

| Intercept Change | 3.229 *** | 1.144 | 17.343 *** | 3.890 *** | 4.931 *** | 3.987 * |

| (0.205) | (0.118) | (5.016) | (1.571) | (2.250) | (2.751) | |

| Slope Change | 0.912 *** | 0.985 | 0.634 *** | 0.919 | 0.611 *** | 0.926 |

| (0.018) | (0.032) | (0.059) | (0.138) | (0.058) | (0.139) | |

| Intercept Change x Women | 5.069 *** | |||||

| (0.673) | ||||||

| Slope Change x Women | 0.900 ** | |||||

| (0.036) | ||||||

| Intercept Change x Country | ||||||

| Australia | 0.349 ** | 0.313 ** | 1.169 | 0.259 | ||

| (0.124) | (0.139) | (0.604) | (0.188) | |||

| Korea | 0.187 *** | 0.176 ** | 0.263 * | 0.133 * | ||

| (0.089) | (0.097) | (0.167) | (0.108) | |||

| USA | 0.132 *** | 0.125 *** | 0.345 | 0.111 ** | ||

| (0.052) | (0.066) | (0.207) | (0.093) | |||

| Russia | 0.189 *** | 0.224 ** | 0.525 | 0.260 | ||

| (0.067) | (0.111) | (0.282) | (0.200) | |||

| Switzerland | 0.690 | 0.133 *** | 1.342 | 0.287 | ||

| (0.288) | (0.076) | (0.759) | (0.246) | |||

| UK | 0.321 *** | 0.453 | 0.687 | 0.488 | ||

| (0.105) | (0.202) | (0.343) | (0.357) | |||

| Slope Change x Country | ||||||

| Australia | 1.251 * | 0.982 | 1.298 * | 0.990 | ||

| (0.137) | (0.158) | (0.143) | (0.160) | |||

| Korea | 1.611 *** | 0.860 | 1.818 *** | 0.878 | ||

| (0.209) | (0.160) | (0.243) | (0.164) | |||

| USA | 1.581 *** | 1.156 | 1.650 *** | 1.135 | ||

| (0.201) | (0.217) | (0.211) | (0.215) | |||

| Russia | 1.553 *** | 1.319 | 1.619 *** | 1.342 | ||

| (0.172) | (0.236) | (0.181) | (0.242) | |||

| Switzerland | 1.375 ** | 1.434 | 1.449 ** | 1.367 | ||

| (0.166) | (0.274) | (0.178) | (0.264) | |||

| UK | 1.457 *** | 1.034 | 1.528 *** | 1.018 | ||

| (0.151) | (0.170) | (0.160) | (0.167) | |||

| Intercept Change x | 4.532 *** | 0.842 | ||||

| Children in HH | (2.020) | (0.620) | ||||

| Intercept Change x Children in HH x Country | ||||||

| Australia | 0.242 ** | 1.305 | ||||

| (0.127) | (1.043) | |||||

| Korea | 1.783 | 1.965 | ||||

| (1.291) | (1.796) | |||||

| USA | 0.338 | 1.664 | ||||

| (0.199) | (1.518) | |||||

| Russia | 0.319 * | 0.782 | ||||

| (0.174) | (0.662) | |||||

| Switzerland | 0.892 | 0.730 | ||||

| (0.542) | (0.723) | |||||

| UK | 0.486 | 1.206 | ||||

| (0.240) | (0.981) | |||||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Education (ref. higher) | ||||||

| Lower | 1.421 | 1.432 | 1.379 | 1.008 | 1.265 | 0.987 |

| (0.272) | (0.279) | (0.349) | (0.360) | (0.321) | (0.356) | |

| Medium | 1.068 | 1.139 | 1.193 | 0.987 | 1.120 | 0.946 |

| (0.158) | (0.172) | (0.213) | (0.308) | (0.201) | (0.301) | |

| Weekly hours worked | 0.956 *** | 0.950 *** | 0.946 *** | 0.950 *** | 0.944 *** | 0.949 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.008) | (0.006) | (0.009) | |

| Weekly hours worked (sq) | 1.000 *** | 1.000 *** | 1.000 *** | 1.000 *** | 1.000 *** | 1.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Socioeconomic incex (ISEI08) | 0.987 *** | 0.987 *** | 0.991 ** | 0.980 *** | 0.991 ** | 0.981 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Age (ref. 18–25) | ||||||

| 26–35 | 0.701 *** | 0.734 ** | 0.754 * | 0.763 | 0.770 * | 0.745 |

| (0.068) | (0.073) | (0.100) | (0.122) | (0.102) | (0.120) | |

| 36–45 | 0.760 | 0.780 | 0.884 | 0.705 | 0.829 | 0.717 |

| (0.114) | (0.119) | (0.177) | (0.178) | (0.168) | (0.183) | |

| 46–55 | 0.947 | 0.925 | 0.875 | 1.100 | 0.788 | 1.109 |

| (0.193) | (0.191) | (0.233) | (0.373) | (0.212) | (0.381) | |

| 56–65 | 1.224 | 1.183 | 1.044 | 1.526 | 1.220 | 1.502 |

| (0.341) | (0.334) | (0.386) | (0.700) | (0.452) | (0.694) | |

| Children in HH | 2.019 *** | 1.558 *** | 1.367 ** | 1.843 *** | ||

| (0.138) | (0.110) | (0.140) | (0.191) | |||

| Observations | 16,456 | 16,456 | 10,422 | 6034 | 10,422 | 6034 |

| Number of respondents | 2493 | 2493 | 1595 | 898 | 1595 | 898 |

| LR chisq | 775 *** | 1073 *** | 1066 *** | 220 *** | 1130 *** | 255 *** |

| DF | 13 | 16 | 31 | 31 | 44 | 44 |

| Log likelihood | −5719 | −5570 | −3363 | −2099 | −3332 | −2082 |

| AIC | 11,464 | 11,172 | 6789 | 4261 | 6752 | 4252 |

| BIC | 11,564 | 11,295 | 7014 | 4469 | 7071 | 4547 |

References

- Allison, Paul D. 2009. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, Paul R. 2000. The Consequences of Divorce for Adults and Children. Journal of Marriage and Family 62: 1269–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, Paul R. 2001. Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology 15: 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, Paul R. 2014. The consequences of divorce for adults and children: An update. Društvena Istraživanja: Časopis za Opća Društvena Pitanja 23: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ambert, Anne-Marie. 2005. Divorce: Facts, Causes, and Consequences. Ottawa: Vanier Institute of the Family Ottawa, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, Sudhir, and Amartya Sen. 1994. Human Development Index: Methodology and Measurement. Occasional Paper 12, Human Development Report Office. New York: UNDP. [Google Scholar]

- Andreß, Hans-Jürgen, Barbara Borgloh, Miriam Bröckel, Marco Giesselmann, and Dina Hummelsheim. 2006. The Economic Consequences of Psartnership Dissolution—A Comparative Analysis of Panel Studies from Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, and Sweden. European Sociological Review 22: 533–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellar, Sarah, and Pamela J. Smock. 2005. The economic consequences of the dissolution of cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family 67: 315–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayaz-Ozturk, Gulgun, Richard V. Burkhauser, Kenneth A. Couch, and Richard Hauser. 2018. The effects of union dissolution on the economic resources of men and women: A comparative analysis of Germany and the United States, 1985–2013. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 680: 235–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellu, Lorenzo Giovanni, and Paolo Liberati. 2005. Impacts of Policies on Poverty: The Definition of Poverty. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Bessell, Sharon. 2015. The individual deprivation measure: Measuring poverty as if gender and inequality matter. Gender & Development 23: 223–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bredtmann, Julia, and Christina Vonnahme. 2017. Less Alimony After Divorce–Spouses’ Behavioral Response to the 2008 Alimony Reform in Germany. SOEP-Papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Date Research at DIW. Berlin: DIW. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, Richard. 2005. Foundations of a neo-Weberian class analysis. Approaches to Class Analysis, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashmore, Judy, Patrick Parkinson, Ruth Weston, Roger Patulny, Gerry Redmond, Lixia Qu, Jennifer Baxter, Marianne Rajkovic, Tomasz Sitek, and Ilan Katz. 2010. Shared Care Parenting Arrangements Since the 2006 Family Law Reforms. Sydney: University of New South Wales Social Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Yeonok, and Robert Emery. 2010. Early Adolescents and Divorce in South Korea: Risk, Resilience and Pain. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 41: 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Yiyoon, and Yeongmin Kim. 2019. How cultural and policy contexts interact with child support policy: A case study of child support receipt in Korea and the United States. Children and Youth Services Review 96: 237–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, Kenneth A., Christopher R. Tamborini, Gayle L. Reznik, and John W. R. Phillips. 2013. Divorce, women’s earnings, and retirement over the life course. Lifecycle Events and Their Consequences: Job Loss, Family Change, and Declines in Health, 133–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vaus, David, Matthew Gray, Lixia Qu, and David Stanton. 2017. The economic consequences of divorce in six OECD countries. Australian Journal of Social Issues 52: 180–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewilde, Caroline. 2003. A life—Course perspective on social exclusion and poverty. The British Journal of Sociology 54: 109–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPrete, Thomas A. 2002. Life course risks, mobility regimes, and mobility consequences: A comparison of Sweden, Germany, and the United States. American Journal of Sociology 108: 267–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, Glen H. 1995. The life course paradigm: Social change and individual development. In Examining Lives in Context: Perspectives on the Ecology of Human Development. Edited by Phyllis Moen, Glenn H. Elder Jr. and Kurt Lüscher. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 101–39. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fehlberg, Belinda. 2004. Spousal maintenance in Australia. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family 18: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadalla, Tahany M. 2008. Gender differences in poverty rates after marital dissolution: A longitudinal study. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage 49: 225–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom, Harry B. G. 2010. A new International Socio-Economic Index (ISEI) of occupational status for the International Standard Classification of Occupation 2008 (ISCO-08) constructed with data from the ISSP 2002–2007. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of International Social Survey Programme, Lisbon, Portugal, May 1. [Google Scholar]

- Grusky, David B., and Kim A. Weeden. 2013. Measuring poverty: The case for a sociological approach. In The Many Dimensions of Poverty. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars, Aldi, and Klaas De Vos. 1988. The definition and measurement of poverty. Journal of Human Resources, 211–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härkönen, Juho, and Jaap Dronkers. 2006. Stability and change in the educational gradient of divorce. A comparison of seventeen countries. European Sociological Review 22: 501–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hauser, Richard, Richard V. Burkhauser, Kenneth A. Couch, Gulgun Bayaz-Ozturk, and Cuny City Tech. 2018. Wife or Frau, women still do worse: A comparison of men and women in the United States and Germany after union dissolutions in the 1990s and 2000s. Innovation und Wissenstransfer in der Empirischen Sozial-und Verhaltensforschung, 167–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haux, Tina, Stephen McKay, and Ruth Cain. 2017. Shared care after separation in the United Kingdom: Limited data, limited practice? Family Court Review 55: 572–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogendoorn, Bram, Thomas Leopold, and Thijs Bol. 2020. Divorce and diverging poverty rates: A risk and vulnerability approach. Journal of Marriage and Family 82: 1089–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, Olli, and Joakim Palme. 2000. Does social policy matter? Poverty cycles in OECD countries. International Journal of Health Services 30: 335–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kauppinen, Timo M., Anna Angelin, Thomas Lorentzen, Olof Bäckman, Tapio Salonen, Pasi Moisio, and Espen Dahl. 2014. Social background and life-course risks as determinants of social assistance receipt among young adults in Sweden, Norway and Finland. Journal of European Social Policy 24: 273–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazova, Olga A. 2005. Allocation of parental rights and responsibilities after separation and divorce under Russian Law. Family Law Quarterly 39: 373–91. [Google Scholar]

- Korpi, Walter, and Joakim Palme. 1998. The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: Welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the Western countries. American Sociological Review 63: 661–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leopold, Thomas. 2018. Gender differences in the consequences of divorce: A study of multiple outcomes. Demography 55: 769–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maes, Margot, Gert Thielemans, and Ekaterina Tretyakova. 2020. Does Divorce Penalize Elderly Fathers in Receiving Help from Their Children? Evidence from Russia. In Divorce in Europe. Cham: Springer, pp. 167–82. [Google Scholar]

- Manting, Dorien, and Anne Marthe Bouman. 2006. Short-and long-term economic consequences of the dissolution of marital and consensual unions. The example of the Netherlands. European Sociological Review 22: 413–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, Neil, and Bob Baulch. 2000. Simulating the impact of policy upon chronic and transitory poverty in rural Pakistan. The Journal of Development Studies 36: 100–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, Patricia A., and Thomas A. DiPrete. 2001. Losers and winners: The financial consequences of separation and divorce for men. American Sociological Review 66: 246–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Daniel R., Maria Cancian, and Steven T. Cook. 2017. The growth in shared custody in the United States: Patterns and implications. Family Court Review 55: 500–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortelmans, Dimitri. 2020. Economic Consequences of Divorce: A Review. Parental Life Courses after Separation and Divorce in Europe, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2006. Poverty and human functioning: Capabilities as fundamental entitlements. Poverty and Inequality 1990: 47–75. [Google Scholar]

- Oris, Michel, Rainer Gabriel, Gilbert Ritschard, and Matthias Kliegel. 2017. Long lives and old age poverty: Social stratification and life-course institutionalization in Switzerland. Research in Human Development 14: 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Sangyoub. 2015. A silent revolution in the korean family. Contexts 14: 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogge, Thomas, and Scott Wisor. 2016. Measuring poverty: A proposal. The Oxford Handbook of Well-Being and Public Policy, 645–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, Daria, and Jekaterina Navicke. 2019. The probability of poverty for mothers after childbirth and divorce in Europe: The role of social stratification and tax-benefit policies. Social Science Research 78: 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodgers, Joan R., and John L. Rodgers. 1993. Chronic poverty in the United States. Journal of Human Resources 28: 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sagar, Ambuj D., and Adil Najam. 1998. The human development index: A critical review. Ecological Economics 25: 249–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, Amartya. 2006. Conceptualizing and measuring poverty. In Poverty and Inequality. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Shildrick, Tracy, and Jessica Rucell. 2015. Sociological Perspectives on Poverty. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Tach, Laura M., and Alicia Eads. 2015. Trends in the economic consequences of marital and cohabitation dissolution in the United States. Demography 52: 401–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, Peter. 1954. Measuring poverty. The British Journal of Sociology 5: 130–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, Konrad, Matthijs Kalmijn, and Thomas Leopold. 2020. Comparative Panel File: Household Panel Surveys from Seven Countries. Manual for CPF v. 1.0. OSF Preprints 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, Konrad, Matthijs Kalmijn, and Thomas Leopold. 2021. The Comparative Panel File: Harmonized Household Panel Surveys from Seven Countries. European Sociological Review 37: 505–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, Layla, and Dimitri Mortelmans. 2018. De Onzichtbare Scheidingsgolf: Een Analyse van Relatieontbinding van Samenwonenden en Gehuwden in België. Relaties en Nieuwe Gezinnen 8: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker, Wim, and Julie Vinck. 2019. The consequences of growing up poor. In Routledge International Handbook of Poverty. London: Routledge, pp. 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele, Leen. 2010a. Life Course Risks or Cumulative Disadvantage? The Structuring Effect of Social Stratification Determinants and Life Course Events on Poverty Transitions in Europe. European Sociological Review 27: 246–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandecasteele, Leen. 2010b. Poverty trajectories after risky life course events in different European welfare regimes. European Societies 12: 257–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vandecasteele, Leen. 2015. Social class, life events and poverty risks in comparative European perspective. International Review of Social Research 5: 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walper, Sabine, Christine Entleitner-Phleps, and Alexandra N. Langmeyer. 2021. Shared physical custody after parental separation: Evidence from Germany. Shared Physical Custody 25: 285. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, Christopher T., and Bertrand Maître. 2008. “New” and “Old” Social Risks: Life Cycle and Social Class Perspectives on Social Exclusion in Ireland. Economic & Social Review 39: 131–56. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Incidence | Grounds c | Determined by | Amount | Duration | Exists for Cohabitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Uncommon | Limited circumstances | Court | Minimal | Usually a short period of time | No |

| Korea | Non-existent | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| USA b | Common | Limited circumstances | Partners, Mediator, Court | Individually determined | Set date or certain life course events a | No |

| Russia | Uncommon | Limited circumstances | Court | Sufficient for living needs | Discretion of the court | No |

| Switzerland | Uncommon | Limited circumstances | Court | Sufficient for living needs | Usually limited duration | No |

| Germany | Common | Limited circumstances | Court | Individually determined | Individually determined | No |

| UK | Common | Limited circumstances | Court | Sufficient for living needs | Depends on marriage duration and events (remarriage) | Yes |

| Country | Involvement in the Determination of Child Maintenance | Responsibility for Determining Maintenance Payments | Rules for Determining the Amount of Payments | Enforcement of Payments | Different for Children of Unmarried Parents | Age at Which Support Ends | Advance on Maintenance Payments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Court | Agency | |||||||

| Australia | Yes—formal system if parents cannot agree | Yes (residual role) | Yes—CSA | Parents or CSA | Rules/rigid formula | CSA | No | 18 years or end of schooling | No |

| Korea | Yes—ratified by court | Yes | No | Parents or Court if parental disagreement | Mostly discretion, no fixed rules or methods | Court | No | Parental agreement or 20 years | No |

| USA | Yes—ratified by court | Yes | Yes—CSA (varies by state) | Court | Formal guidelines | Court and CSA | No | Varies across states (16–25) | No |

| Russia | Yes—formal system if parents cannot agree | Yes (residual role) | No | Parents or court if parental disagreement | Rules in case of disagreement | Court | No | 18 years | Yes |

| Switzerland | Yes—ratified by court | Yes | No | Parents with supervision of lawyers or court | Rules | Court | Yes | 18 years or end of education | Yes |

| Germany | Yes | Yes | No | Parents or court if parental disagreement | Mostly discretion, using “support tables” | Court | Yes | 18 years | Yes |

| UK | Yes—ratified by court | Yes (residual role) | Yes—CSA | Parents or CSA | Rules/rigid formula | Court and CSA | No | 16 years or 19 years if in full time education | Yes |

| Women (Obs. = 10,422; N = 1595) | Men (Obs. = 6034; N = 898) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| Time to/since factual separation | −1.32 | 3.94 | −10 | 7 | −0.99 | 3.88 | −10 | 7 |

| ISEI08 b | 40.37 | 14.76 | 10 | 89 | 39.66 | 13.96 | 10 | 89 |

| Weekly work hours | 31.80 | 14.61 | 0 | 120 | 42.15 | 14.04 | 0 | 119 |

| % | % | |||||||

| AROP c | 33% | 31% | ||||||

| Country | ||||||||

| Australia | 20% | 31% | ||||||

| Korea | 5% | 8% | ||||||

| USA | 8% | 9% | ||||||

| Russia | 14% | 11% | ||||||

| Switzerland | 10% | 8% | ||||||

| Germany | 10% | 7% | ||||||

| UK | 33% | 26% | ||||||

| Educational attainment | ||||||||

| Low | 16% | 21% | ||||||

| Medium | 54% | 58% | ||||||

| High | 30% | 21% | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–25 | 13% | 13% | ||||||

| 26–35 | 31% | 31% | ||||||

| 36–45 | 33% | 29% | ||||||

| 46–55 | 19% | 21% | ||||||

| 56–65 | 4% | 6% | ||||||

| Children living in the household a | 64% | 51% | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thielemans, G.; Mortelmans, D. Poverty Risks after Relationship Dissolution and the Role of Children: A Contemporary Longitudinal Analysis of Seven OECD Countries. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030138

Thielemans G, Mortelmans D. Poverty Risks after Relationship Dissolution and the Role of Children: A Contemporary Longitudinal Analysis of Seven OECD Countries. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(3):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030138

Chicago/Turabian StyleThielemans, Gert, and Dimitri Mortelmans. 2022. "Poverty Risks after Relationship Dissolution and the Role of Children: A Contemporary Longitudinal Analysis of Seven OECD Countries" Social Sciences 11, no. 3: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030138

APA StyleThielemans, G., & Mortelmans, D. (2022). Poverty Risks after Relationship Dissolution and the Role of Children: A Contemporary Longitudinal Analysis of Seven OECD Countries. Social Sciences, 11(3), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030138