Linking COVID-19-Related Awareness and Anxiety as Determinants of Coping Strategies’ Utilization among Senior High School Teachers in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Measurement of Variables

2.2.1. Anxiety

2.2.2. Awareness

2.2.3. Coping Strategies

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics on Study Variables

3.2. The Relationship between COVID-19 Awareness of Teachers and Their Anxiety Level

3.3. The Influence of COVID-19-Related Anxiety on Coping Mechanisms of Teachers

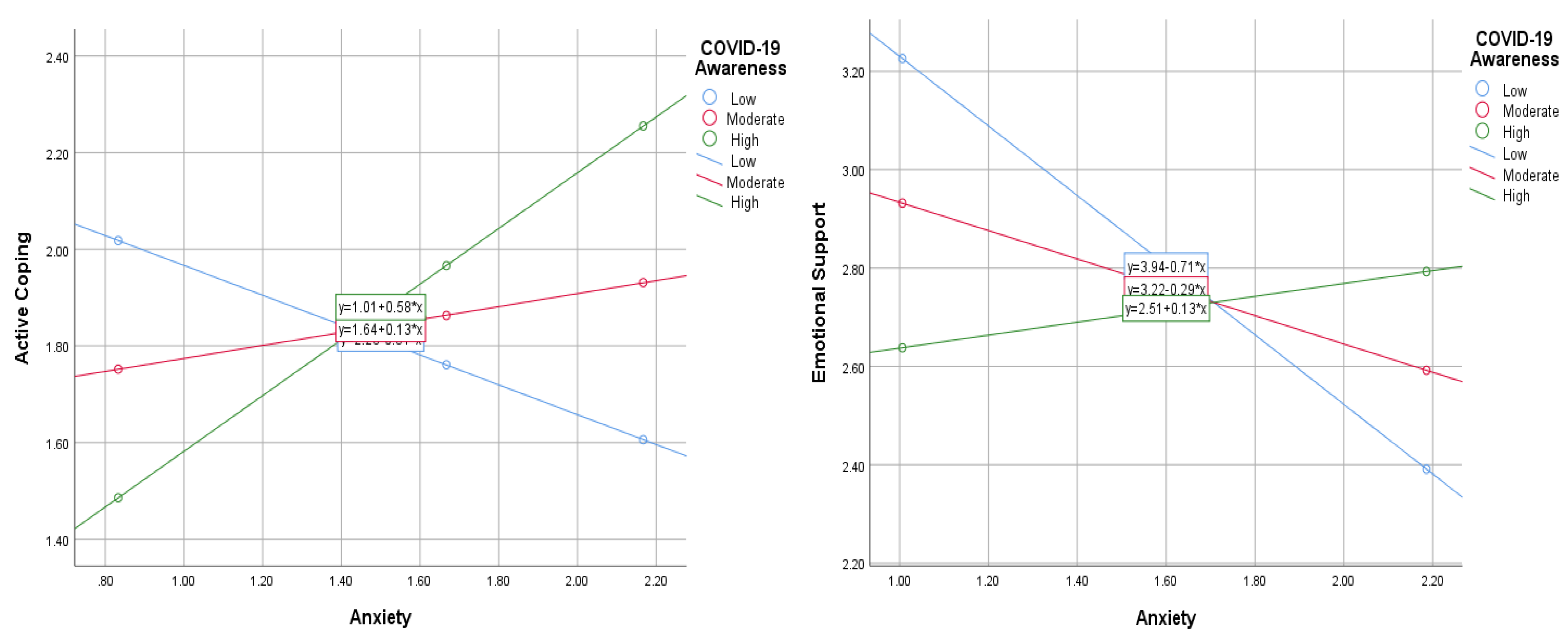

3.4. Moderating Role of COVID-19 Awareness of Teachers in the Relationship between Anxiety and Coping

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adarkwah, Michael Agyemang. 2020. “I’m not against online teaching, but what about us?”: ICT in Ghana post COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies 26: 1665–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, Sajida. 2021. Mental well-being and association of the four factors coping structure model: A perspective of people living in lockdown during COVID-19. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health 16: 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agormedah, Edmond Kwesi, Eugene Adu Henaku, Desire Mawuko Komla Ayite, and Enoch Apori Ansah. 2020. Online learning in higher education during COVID-19 pandemic: A case of Ghana. Journal of Educational Technology & Online Learning 3: 183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ahinkorah, Bright Opoku, Edward Kwabena Ameyaw, John Elvis Hagan Jr., Abdul-Aziz Seidu, and Thomas Schack. 2020. Rising above misinformation or fake news in Africa: Another strategy to control COVID-19 spread. Frontiers in Communication 5: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Wahab. 2020. Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Education Studies 10: 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Rebecca, John Jerrim, and Sam Sims. 2020. How did the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic affect teacher wellbeing. Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities (CEPEO) Working Paper 1: 20–15. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Lily, Abdulrahman Essa, Abdelrahim Fathy Ismail, Fathi Mohammed Abunasser, and Rafdan Hassan Alhajhoj Alqahtani. 2020. Distance education as a response to pandemics: Coronavirus and Arab culture. Technology in Society 63: 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansah, Joseph Kweku, Frank Quansah, and Regina Mawusi Nugba. 2020. ‘Mathematics Achievement in Crisis’: Modelling the Influence of Teacher Knowledge and Experience in Senior High Schools in Ghana. Open Education Studies 2: 265–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanga, Paschal Awingura, Isaac Bador Kamal Lettor, and Ramatu Akunvane. 2021. Practice of COVID-19 preventive measures and its associated factors among students in Ghana. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104: 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banji, George Tesilimi, Mabel Frempong, Stephen Okyere, and Abdul Sakibu Raji. 2021. University students’ readiness for e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: An assessment of the University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho in Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-Journal) 1: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Aaron T., Norman Epstein, Gary Brown, and Robert A. Steer. 1988. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 58: 893–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besser, Avi, Sari Lotem, and Virgil Zeigler-Hill. 2020. Psychological stress and vocal symptoms among university professors in Israel: Implications of the shift to online synchronous teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Voice, 1–8, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadu, Kankam. 2013. Teachers’ perception on the importance of teaching citizenship education to primary school children in Cape Coast, Ghana. Journal of Arts and Humanities 2: 137–47. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, Godfred O., David Teye Doku, Nancy Innocentia Ebu Enyan, Samuel Asiedu Owusu, Irene Korkoi Aboh, Ruby Victoria Kodom, Benard Ekumah, Reginald Quansah, Sheila A. Boamah, Dorcas Obiri-Yeboah, and et al. 2021. Prevalence and changes in boredom, anxiety and well-being among Ghanaians during the COVID-19 pandemic: A population-based study. BMC Public Health 21: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, Aras, and Ramesh C. Sharma. 2020. Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to coronavirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education 15: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Brouzos, Andreas, Stephanos P. Vassilopoulos, Antigone Vlachioti, and Vasiliki Baourda. 2020. A coping-oriented group intervention for students waiting to undergo secondary school transition: Effects on coping strategies, self-esteem, and social anxiety symptoms. Psychology in the Schools 57: 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bru, Edvin. 2019. Stress og mestring i skolen—en forståelsesmodell. In Stress og Mestring i Skolen (s. 19–46). Edited by Ian Eric Bru and Philip Roland. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Budimir, Sanja, Thomas Probst, and Christoph Pieh. 2021. Coping strategies and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Mental Health 30: 156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Simon, and Hans Henrik Sievertsen. 2020. Schools, Skills, and Learning: The Impact of COVID-19 on Education, CEPR Policy Portal. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- Cáceres-Muñoz, Jorge, Antonio Salvador Jiménez Hernández, and Miguel Martín-Sánchez. 2020. School closings and socio-educational inequality in times of COVID-19. An exploratory research in an international key. Revista Internacional de Educacion Para La Justicia Social 9: 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, Jude Mary, Rose Darly Dalexis, Mireille Guerrier, Pari-Gole Noorishad, Daniel Derivois, Jacqueline Bukaka, Jean-Pierre Birangui, Kouami Adansikou, Lewis Ampidu Clorméus, Cyrille Kossigan Kokou-Kpolou, and et al. 2021. Frequency and correlates of anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in low-and middle-income countries: A multinational study. Journal of Psychiatric Research 132: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Hoi Yan, and Sammy K. F. Hui. 2011. Teaching anxiety amongst Hong Kong and Shanghai in-service teachers: The impact of trait anxiety and self-esteem. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher 20: 395–409. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, Qian Hui, Ker Chiah Wei, Shawn Vasoo, Hong Choon Chua, and Kang Sim. 2020. Narrative synthesis of psychological and coping responses towards emerging infectious disease outbreaks in the general population: Practical considerations for the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore Medical Journal 61: 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, Christina, and Marc Brackett. 2020. Teachers Are Anxious and Overwhelmed. They Need SEL now more than Ever. EdSurge News. Available online: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2020-04-07- (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Crawford, Joseph, Kerryn Butler-Henderson, Jürgen Rudolph, Bashar Malkawi, Matt Glowatz, Rob Burton, Paulo Magni, and Sophia Lam. 2020. COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching 3: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, Roberto Moraes, Ricelli Endrigo Ruppel da Rocha, Solange Andreoni, and Andrea Duarte Pesca. 2020. Returning to work? Mental health indicators of the teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Polyphonía 31: 325–44. [Google Scholar]

- Demuyakor, John. 2021. COVID-19 pandemic and higher education: Leveraging on digital technologies and mobile applications for online learning in Ghana. International Journal of Education 9: 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouky, Dalia, and Heba Allam. 2017. Occupational stress, anxiety and depression among Egyptian teachers. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health 7: 191–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, Nicolas, Kalyani Kentheswaran, Aras Ahmadi, Johanne Teychené, Yolaine Bessière, Sandrine Alfenore, Stéphanie Laborie, Dominique Bastoul, Karine Loubière, Christelle Guigui, and et al. 2020. Attempts, successes, and failures of distance learning in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Chemical Education 97: 2448–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougall, Isla, Mario Weick, and Milica Vasiljevic. 2021. Inside UK Universities: Staff Mental Health and Wellbeing during the Coronavirus Pandemic. PsyArXiv. June 22. Available online: https://www.europepmc.org/article/ppr/ppr360395 (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- Dubik, Stephen Dajaan, Kingsley E. Amegah, and Alhassan S. Adam. 2021. Resumption of school amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid assessment of knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices among final-year senior high students at a technical institute in Ghana. Education Research International 2021: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endriyas, Misganu, Aknaw Kawza, Abraham Alano, Mamush Hussen, Emebet Mekonnen, Teka Samuel, Mekonnen Shiferaw, Sinafikish Ayele, Temesgen Kelaye, Tebeje Misganaw, and et al. 2021. Knowledge and attitude towards COVID-19 and its prevention in selected ten towns of SNNP Region, Ethiopia: Cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 16: e0255884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Yaqing, Panpan Liu, and Qisheng Gao. 2021. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice toward COVID-19 in China: An online cross-sectional survey. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 104: 1461–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cruz, Manuel Fernández, José Álvarez Rodríguez, Inmaculada Ávalos Ruiz, Mercedes Cuevas López, Claudia de Barros Camargo, Francisco Díaz Rosas, Esther González Castellón, Daniel González González, Antonio Hernández Fernández, Pilar Ibáñez Cubillas, and et al. 2020. Evaluation of the emotional and cognitive regulation of young people in a lockdown situation due to the Covid-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 565503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodjo, Joseph Nelson Siewe, Leonard Ngarka, Wepnyu Y. Njamnshi, Leonard N. Nfor, Michel K. Mengnjo, Edwige Laure Mendo, Samuel A. Angwafor, Jonas Guy Atchou Basseguin, Cyrille Nkouonlack, Edith N. Njit, and et al. 2021. Fear and depression during the COVID-19 outbreak in Cameroon: A nation-wide observational study. BMC Psychiatry 21: 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebretsadik, Daniel, Saba Gebremichael, and Melaku Ashagrie Belete. 2021. Knowledge, attitude and practice toward COVID-19 pandemic among population visiting Dessie Health Center for COVID-19 screening, Northeast Ethiopia. Infection and Drug Resistance 14: 905–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldsetzer, Pascal. 2020. Use of rapid online surveys to assess people’s perceptions during infectious disease outbreaks: A cross-sectional survey on COVID-19. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e18790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualano, Maria Rosaria, Giuseppina Lo Moro, Gianluca Voglino, Fabrizio Bert, and Roberta Siliquini. 2020. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyampoh, Alexander Obiri, Henry Kwao Ayitey, Charles Fosu-Ayarkwah, Seth Akyea Ntow, Joseph Akossah, Miracule Gavor, and Dimitrios Vlachopoulos. 2020. Tutor perception on personal and institutional preparedness for online teaching-learning during the COVID-19 crisis: The case of Ghanaian Colleges of Education. African Educational Research Journal 8: 511–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, Ola, and Yasmine Salah El-Din. 2021. Egyptian educators’ online teaching challenges and coping strategies during COVID-19. Arab World English Journal 12: 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henaku, Eugene Adu. 2020. COVID-19: Online Learning Experience of College Students: The case of Ghana. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Sciences and Advanced Technology 1: 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Cyrus SH, Cornelia Yi Chee, and Roger Cm Ho. 2020. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore 49: 155–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, Charles B., Stephanie Moore, Barbara B. Lockee, Torrey Trust, and Mark Aaron Bond. 2020. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review 27: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Yeen, and Ning Zhao. 2020. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research 288: 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddi, Samuel, Dorcas Obiri-Yeboah, Irene Korkoi Aboh, Reginald Quansah, Samuel Asiedu Owusu, Nancy Innocentia Ebu Enyan, Ruby Victoria Kodom, Epaphrodite Nsabimana, Stefan Jansen, Benard Ekumah, and et al. 2021. Coping strategies adapted by Ghanaians during the COVID-19 crisis and lockdown: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 16: e0253800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, Hülya. 2016. A qualitative study on foreign language teaching anxiety. Journal of Qualitative Research in Education 4: 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Sheena, Cary Cooper, Sue Cartwright, Ian Donald, Paul Taylor, and Clare Millet. 2005. The experience of work-related stress across occupations. Journal of Managerial Psychology 20: 178–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joy, Abilin, Alanta Eldhose, Alsa Lalu, Anjana Alias, Annmaria Philip, Anu Abraham, Anu S. Karimankulam, Ashly, Sara Joy, Betcy Benny, and et al. 2021. Assessment of Stress and Coping Strategies of Nursing Teachers due to Online Teaching During COVID-19. International Journal of Neurological Nursing 7: 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Klapproth, Florian, Lisa Federkeil, Franziska Heinschke, and Tanja Jungmann. 2020. Teachers’ experiences of stress and their coping strategies during COVID-19 induced distance teaching. Journal of Pedagogical Research 4: 444–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, Richard S. 2006. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, Richard S., and Susan Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Quanman, Yudong Miao, Xin Zeng, Clifford Silver Tarimo, Cuiping Wu, and Jian Wu. 2020a. Prevalence and factors for anxiety during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic among the teachers in China. Journal of Affective Disorders 277: 153–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Quanman, Clifford Silver Tarimo, Yudong Miao, Xin Zeng, Cuiping Wu, and Jian Wu. 2020b. Effects of mask wearing on anxiety of teachers affected by COVID-19: A large cross-sectional study in China. Journal of Affective Disorders 281: 574–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Meihua, and Bin Wu. 2021. Teaching anxiety and foreign language anxiety among Chinese college English teachers. SAGE Open, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yunyu, Pengfei Li, Yalan Lv, Xiaorong Hou, Qingmao Rao, Juntao Tan, Jun Gong, Chao Tan, Lifan Liao, and Weilu Cui. 2021. Public awareness and anxiety during COVID-19 epidemic in China: A cross-sectional study. Comprehensive Psychiatry 107: 152235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Juan Pedro, Inmaculada Méndez, Cecilia Ruiz-Esteban, Aitana Fernández-Sogorb, and José Manuel García-Fernández. 2020. Profiles of burnout, coping strategies and depressive symptomatology. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Ramón, Juan Pedro, and Francisco Manuel Morales Rodríguez. 2020. What if violent behavior was a coping strategy? Approaching a model based on artificial neural networks. Sustainability 12: 7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary-Krause, Murielle, Joel José Herranz Bustamante, Mégane Héron, Astrid Juhl Andersen, Tarik El Aarbaoui, and Maria Melchior. 2021. Impact of COVID-19-like symptoms on occurrence of anxiety/depression during lockdown among the French general population. PLoS ONE 16: e0255158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayordomo, Teresa, Paz Viguer, Alicia Sales, Encarnación Satorres, and Juan C. Meléndez. 2016. Resilience and coping as predictors of well-being in adults. The Journal of Psychology 150: 809–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, Evelyn Barron, Divya Singhal, Padmanabhan Vijayaraghavan, Shekhar Seshadri, Eleanor Smith, Pauline Dixon, Steve Humble, Jacqui Rodgers, and Aditya Narain Sharma. 2021. Health anxiety, coping mechanisms and COVID 19: An Indian community sample at week 1 of lockdown. PLoS ONE 16: e0250336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkos, Marlena L., and Nicholas W. Gelbar. 2021. Considerations for educators in supporting student learning in the midst of COVID-19. Psychology in the Schools 58: 416–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nketsia, William, Maxwell P. Opoku, Ahmed H. Mohamed, Emmanuel O. Kumi, Rosemary Twum, and Eunice A. Kyere. 2021. Preservice training amid a pandemic in Ghana: Predictors of online learning success among teachers. Frontiers in Education 6: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwagbara, Ugochinyere Ijeoma, Emmanuella Chinonso Osual, Rumbidzai Chireshe, Obasanjo Afolabi Bolarinwa, Balsam Qubais Saeed, Nelisiwe Khuzwayo, and Khumbulani W. Hlongwana. 2021. Knowledge, attitude, perception, and preventative practices towards COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 16: e0249853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, Anthony Amanfo, Joseph Osarfo, Evans Kofi Agbeno, Dominic Owusu Manu, and Elsie Amoah. 2021. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on health workers in Ghana: A multicentre, cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Medicine 9: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya, Ugorji I., Florence C. Awoniyi, and Mogalatjane E. Matabane. 2020. Move to online learning during COVID-19 lockdown: Pre-service teachers’ experiences in Ghana. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research 19: 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ominde, Shitandi Beryl, Jaiyeoba-Ojigho Jennifer Efe, and Igbigbi Patrick Sunday. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of Delta State University students, Nigeria. Acta Biomed 92: e2021316. [Google Scholar]

- Owhondaa, Golden, Omosivie Maduka, Ifeoma Nwadiuto, Charles Tobin-West, Esther Azi, Chibianotu Ojimah, Datonye Alasia, Ayo-Maria Olofinuka, Vetty Agala, John Nwolim Paul, and et al. 2021. Awareness, perception and the practice of COVID-19 prevention among residents of a state in the South-South region of Nigeria: Implications for public health control efforts. International Health 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Fordjour, Charles, Charles Kwesi Koomson, and David Hanson. 2020. The impact of covid-19 on learning: The perspective of the Ghanaian student. European Journal of Education Studies 7: 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Maria Dosil-Santamaria, Maitane Picaza-Gorrochategui, and Nahia Idoiaga-Mondragon. 2020a. Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the Northern Spain. Cadernos de Saude Publica 36: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Nahia Idoiaga Mondragon, María Dosil Santamaría, and Maitane Picaza Gorrotxategi. 2020b. Psychological symptoms during the two stages of lockdown in response to the COVID-19 outbreak: An investigation in a sample of citizens in Northern Spain. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Maria Dosil Santa María, Amaia Eiguren Munitis, and Maitane Picaza Gorrotxategi. 2020c. Reduction of COVID-19 anxiety levels through relaxation techniques: A study carried out in Northern Spain on a sample of young university students. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Nahia Idoiaga Mondragon, Juan Bueno-Notivol, María Pérez-Moreno, and Javier Santabárbara. 2021a. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Brain Sciences 11: 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Naiara Berasategi Santxo, Nahia Idoiaga Mondragon, and María Dosil Santamaría. 2021b. The psychological state of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis: The challenge of returning to face-to-face teaching. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 620718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Naiara, Maria Dosil Santa María, Idoiaga Mondragon Nahia, and Santxo Berasategi Naiara. 2021c. Emotional state of school and university teachers in northern Spain in the face of COVID-19. Revista Española de Salud Pública 95: e202102030. [Google Scholar]

- Özdin, Selçuk, and Şükriye Bayrak Özdin. 2020. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 66: 504–11. [Google Scholar]

- Prado-Gascó, Vicente, María T. Gómez-Domínguez, Ana Soto-Rubio, Luis Díaz-Rodríguez, and Diego Navarro-Mateu. 2020. Stay at home and teach: A comparative study of psychosocial risks between Spain and Mexico during the pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 566900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, Tim, Cheyeon Ha, and Emily Learn. 2021. Teacher stress and anxiety during COVID-19: An empirical study. School Psychology 36: 367–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, Frank. 2017. The use of Cronbach alpha reliability estimate in research among students in public universities in Ghana. Africa Journal of Teacher Education 6: 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quansah, Frank, John Elvis Hagan Jr., Francis Sambah, James Boadu Frimpong, Francis Ankomah, Medina Srem-Sai, Munkaila Seibu, Kwadwo Samuel Richard Abieraba, and Thomas Schack. 2022a. Perceived safety of learning environment and associated anxiety factors during COVID-19 in Ghana: Evidence from physical education practical-oriented program. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 12: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quansah, F., J. E. Hagan Jr., F. Ankomah, M. Srem-Sai, B. J. Frimpong, F. Sambah, and T. Schack. 2022b. Relationship between COVID-19 related knowledge and anxiety among university students: Exploring the moderating roles of school climate and coping strategies. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 820288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, Frank, Francis Ankomah, John Elvis Hagan Jr., Medina Srem-Sai, James Boadu Frimpong, Francis Sambah, and Thomas Schack. n.d. Development and validation of an inventory for stressful situations in university students involving coping mechanism: An interesting cultural-mix in Ghana. Psych, in press.

- Rabei, Samah Hamed, and Wafaa Osman Abd El Fatah. 2021. Assessing COVID19-related anxiety in an Egyptian sample and correlating it to knowledge and stigma about the virus. Middle East Current Psychiatry 28: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, Rine Christopher, Margaret M. A. Danladi, Dauda Akwai Saleh, and Patricia Ene Ejembi. 2021. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: An epidemiological survey in North-Central Nigeria. Journal of Community Health 46: 457–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rey, Rocío, Garrido-Hernansaiz Helena, and Collado Silvia. 2020. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Frontiers in psychology 11: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, María Dosil, Nahia Idoiaga Mondragon, Naiara Berasategi Santxo, and Naiara Ozamiz-Etxebarria. 2021. Teacher stress, anxiety and depression at the beginning of the academic year during the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Mental Health 8: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selya, Arielle, Jennifer Rose, Lisa Dierker, Donald Hedeker, and Robin Mermelstein. 2012. A practical guide to calculating Cohen’s f2, a measure of local effect size, from PROC MIXED. Frontiers in Psychology 3: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sokal, Laura, Jeff Babb, and Lesley Eblie Trudel. 2020. How to Prevent Teacher Burnout during the Coronavirus Pandemic. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/how-to-preventteacher-burnout-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic-139353 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Temiz, Zeynep. 2020. Nursing Students’ Anxiety Levels and Coping Strategies during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Archives of Nursing and Health Care 6: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, Cong Ling, Miao Li Chee, Kai Hui Koh, Rachel Marjorie Wei Wen Tseng, Shivani Majithia, Sahil Thakur, and Dinesh Visva Gunasekeran. 2021. COVID-19 awareness, knowledge and perception towards digital health in an urban multi-ethnic Asian population. Scientific Reports 11: 10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffour, Adu David, Sophia Efua Cobbinah, Brefo Benjamin, and Florence Otibua. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education sector in Ghana: Learner challenges and mitigations. Research Journal in Comparative Education 2: 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- van Lancker, Wim, and Zachary Parolin. 2020. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health 5: e243–e244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, Russell M., Simon J. Russell, Helen Croker, Jessica Packer, Joseph Ward, Claire Stansfield, Oliver Mytton, Chris Bonell, and Robert Booy. 2020. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 4: 397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Cuiyan, Riyu Pan, Xiaoyang Wan, Yilin Tan, Linkang Xu, Roger S. McIntyre, and Faith N. Choo. 2020. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 87: 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Yanqing, Quanman Li, Clifford Silver Tarimo, Cuiping Wu, Yudong Miao, and Jian Wu. 2021. Prevalence and risk factors of worry among teachers during the COVID-19 epidemic in Henan, China: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 11: e045386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinert, Stefanie, Anja Thronicke, Maximilian Hinse, Friedemann Schad, and Harald Matthes. 2021. School teachers’ self-reported fear and risk perception during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A nationwide survey in Germany. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 9218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolka, Eskinder, Zewde Zema, Melkamu Worku, Kassahun Tafesse, Antehun Alemayehu Anjulo, Kassahun Tekle Takiso, Hailu Chare, and Lolemo Kelbiso. 2020. Awareness towards coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and its prevention methods in selected sites in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia: A quick, exploratory, operational assessment. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 13: 2301–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Jiaqi, Orly Lipsitz, Flora Nasri, Leanna MW Lui, Hartej Gill, Lee Phan, David Chen-Li, Michelle Iacobucci, Roger Ho, Amna Majeed, and et al. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 277: 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Chun, Yiping Li, Pingsheng Chen, Min Pan, and Xiaodong Bu. 2020. A survey on the attitudes of Chinese medical students towards current pathology education. BMC Medical Education 20: 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakar, Burkay, Gamzecan Karakaya, Edibe Pirincci, Erha Onalan, Ramazan Fazil Akkoc, and Suleyman Aydin. 2021. Knowledge, behaviours and anxiety of eastern part of Turkey residents about the current COVID-19 outbreak. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 92: e2021179. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, Murat. 2019. Irrational Happiness Beliefs: Conceptualization, Measurement and Its Relationship with Wellbeing, Personality, Coping Strategies, and Arousal. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester, Leicester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, Murat, Ömer Akgül, and Ekmel Geçer. 2021. The effect of COVID-19 anxiety on general health: The role of COVID-19 coping. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Weixing, Xiangmei Ding, Lingping Xie, and Hongli Wang. 2021. Relationship between higher education teachers’ affect and their psychological adjustment to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: An application of latent profile analysis. Peer Journal 9: e12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 1.60 | 0.59 |

| Awareness | 4.82 | 1.03 |

| Active coping | 2.53 | 0.64 |

| Religious coping | 3.22 | 0.77 |

| Behavior disengagement | 1.76 | 0.73 |

| Emotional support | 2.68 | 0.68 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 6.288 | 1 | 6.288 | 19.937 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 57.404 | 182 | 0.315 | ||

| Total | 63.693 | 183 | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | t | p | |

| (Constant) | 2.464 | 0.199 | 12.401 | <0.001 | |

| Awareness | −0.180 | 0.040 | −0.314 | −4.465 | <0.001 |

| Criterion Variable | Parameter | B | SE | t | p | f2 | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Coping | Intercept | 2.165 | 0.134 | 16.197 | <0.001 | 0.047 | 1.901 | 2.428 |

| Anxiety | 0.231 | 0.079 | 2.944 | 0.004 * | 0.076 | 0.386 | ||

| Religious coping | Intercept | 2.974 | 0.163 | 18.235 | <0.001 | 0.014 | 2.652 | 3.296 |

| Anxiety | 0.154 | 0.096 | 1.608 | 0.110 | −0.035 | 0.343 | ||

| Behavior disengagement | Intercept | 1.571 | 0.155 | 10.157 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 1.266 | 1.876 |

| Anxiety | 0.117 | 0.091 | 1.282 | 0.202 | −0.063 | 0.296 | ||

| Emotional support | Intercept | 2.953 | 0.145 | 20.408 | <0.001 | 0.021 | 2.668 | 3.239 |

| Anxiety | −0.168 | 0.085 | −1.979 | 0.049 | −0.336 | 0.000 |

| Model | B | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI | R2 | F (df1, df2) | f2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constant | 2.346 | 0.716 | 3.277 | 0.933 | 3.758 | 0.084 | 5.52 (3, 180) | 0.092 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | −0.216 | 0.408 | −0.530 | −1.020 | 0.588 | |||||

| Awareness | −0.047 | 0.134 | −0.346 | −0.312 | 0.219 | |||||

| Int_1 | 0.101 | 0.079 | 1.277 | −0.055 | 0.257 | |||||

| 2 | Constant | 5.016 | 0.864 | 5.806 | 3.311 | 6.720 | 0.075 | 4.85 (3, 180) | 0.081 | 0.003 |

| Anxiety | −0.569 | 0.492 | −1.156 | −1.540 | 0.402 | |||||

| Awareness | −0.377 | 0.162 | −2.323 | −0.697 | −0.057 | |||||

| Int_1 | 0.124 | 0.095 | 1.296 | −0.065 | 0.312 | |||||

| 3 | Constant | 4.815 | 0.787 | 6.118 | 3.262 | 6.368 | 0.141 | 9.88 (3, 180) | 0.164 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | −2.080 | 0.448 | −4.640 | −2.964 | −1.195 | |||||

| Awareness | −0.635 | 0.148 | −4.295 | −0.927 | −0.343 | |||||

| Int_1 | 0.443 | 0.087 | 5.089 | 0.271 | 0.614 | |||||

| 4 | Constant | 6.575 | 0.740 | 8.884 | 5.115 | 8.036 | 0.144 | 10.07 (3, 180) | 0.168 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety | −2.253 | 0.421 | −5.345 | −3.084 | −1.421 | |||||

| Awareness | −0.696 | 0.139 | −5.008 | −0.971 | −0.422 | |||||

| Int_1 | 0.408 | 0.082 | 4.986 | 0.246 | 0.569 |

| Probing | Awareness | Effect | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3: Active Coping | 4.000 | −0.309 | 0.128 | −2.414 | −0.561 | −0.056 |

| 5.000 | 0.134 | 0.090 | 1.496 | −0.043 | 0.311 | |

| 6.000 | 0.577 | 0.122 | 4.726 | 0.336 | 0.818 | |

| Model 4: Emotional Support | 3.786 | −0.708 | 0.133 | −5.315 | −0.971 | −0.445 |

| 4.815 | −0.288 | 0.086 | −3.338 | −0.459 | −0.118 | |

| 5.844 | 0.131 | 0.107 | 1.232 | −0.079 | 0.342 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hagan, J.E., Jr.; Quansah, F.; Ankomah, F.; Agormedah, E.K.; Srem-Sai, M.; Frimpong, J.B.; Schack, T. Linking COVID-19-Related Awareness and Anxiety as Determinants of Coping Strategies’ Utilization among Senior High School Teachers in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030137

Hagan JE Jr., Quansah F, Ankomah F, Agormedah EK, Srem-Sai M, Frimpong JB, Schack T. Linking COVID-19-Related Awareness and Anxiety as Determinants of Coping Strategies’ Utilization among Senior High School Teachers in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(3):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030137

Chicago/Turabian StyleHagan, John Elvis, Jr., Frank Quansah, Francis Ankomah, Edmond Kwesi Agormedah, Medina Srem-Sai, James Boadu Frimpong, and Thomas Schack. 2022. "Linking COVID-19-Related Awareness and Anxiety as Determinants of Coping Strategies’ Utilization among Senior High School Teachers in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana" Social Sciences 11, no. 3: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030137

APA StyleHagan, J. E., Jr., Quansah, F., Ankomah, F., Agormedah, E. K., Srem-Sai, M., Frimpong, J. B., & Schack, T. (2022). Linking COVID-19-Related Awareness and Anxiety as Determinants of Coping Strategies’ Utilization among Senior High School Teachers in Cape Coast Metropolis, Ghana. Social Sciences, 11(3), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11030137