Performance Management and the Police Response to Women in India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Crimes against Women

2.2. Performance Management

2.3. Applying Performance Management to Crimes against Women

3. Methodology

3.1. Dependent Variable

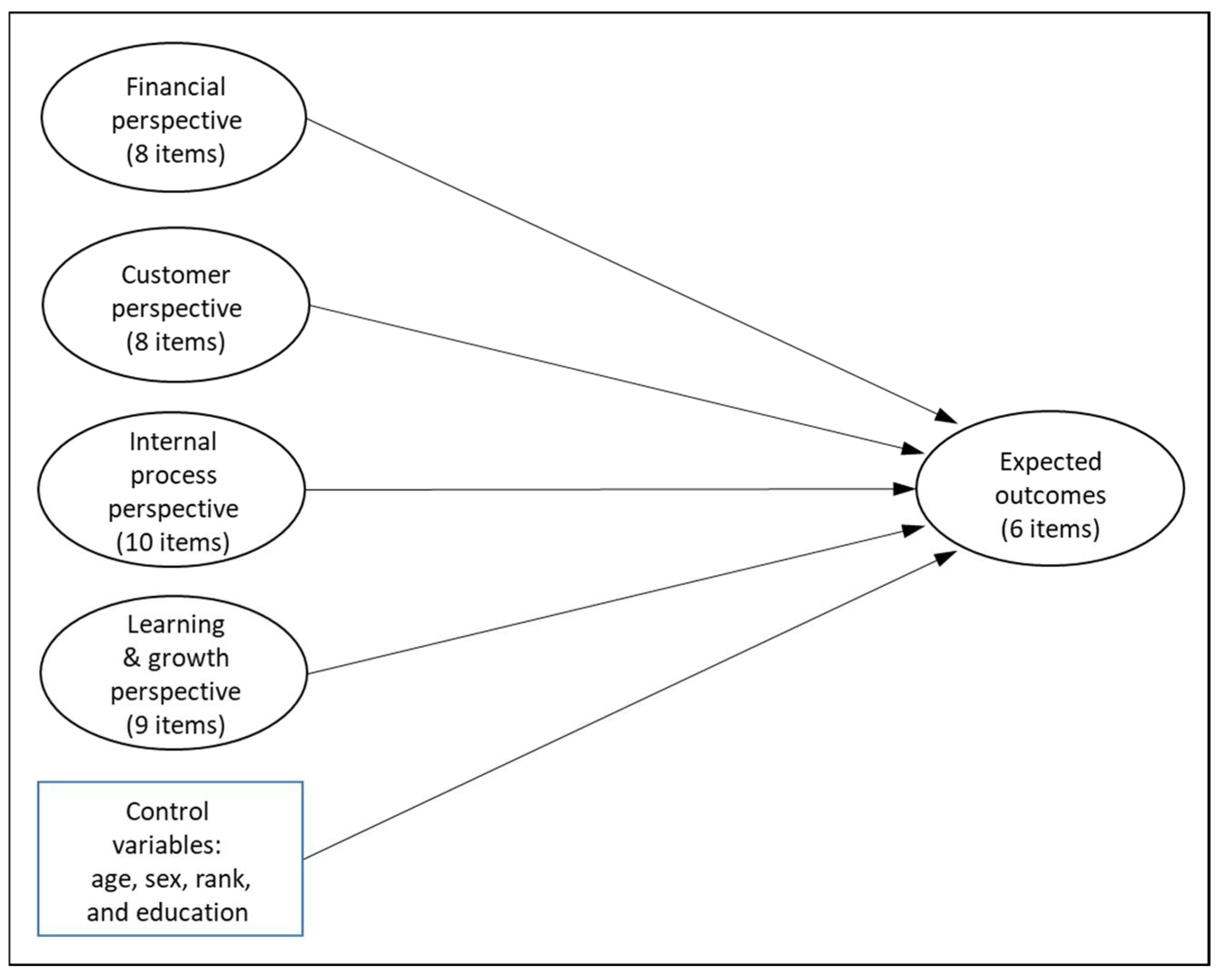

3.2. Independent Variables

4. Findings

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Expected Outcomes

Appendix B. Indicators of Four Balanced Scorecard Dimensions

| 1 | In the Indian Police Service, a gazetted officer is a manager or executive with a rank of Inspector or higher. Those with a rank of Assistant Inspector or below are nongazetted officers. |

| 2 | We treated the ordinal survey responses used to measure these latent variables as crudely categorized approximations of underlying continuous random variables. Although the indicators were categorical, the latent variables were assumed continuous. Many of the procedures used in conventional confirmatory factor analysis with continuous indicators need to be adapted for use with ordinal indicators (Brown 2015). |

| 3 | The model fit the data well according to four of the five fit statistics (CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and WRMR) but not χ2. Though researchers routinely report χ2 in structural equation models, its diagnostic value as a measure of fit has been questioned because it is often too strict (Bowen and Guo 2012). |

| 4 | The correlations between factors ranged from 0.41 to 0.78, with a mean of 0.57 and median of 0.56. Correlations of less than 0.8 between factors typically signify that discriminant validity is not problematic (Brown 2015). We used two additional methods to test for discriminant validity. The first is that the 95% confidence interval of the zero-order correlations between factors cannot include 1 (Bagozzi et al. 1991). The second is that each factor must account for more variance in its indicators than it shares with other factors within the model (Fornell and Larcker 1981). All tests revealed that discriminant validity was not problematic within the measurement model tested here. |

| 5 | As part of our model diagnostics, we computed variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all independent variables in the model. VIF values ranged from 1.1 to 2.6, with a mean of 1.5 and a median of 1.3. These values fall well below the commonly used threshold of 10 for inferring a problem with multicollinearity (Marquardt 1970). Therefore, we conclude that multicollinearity was not an issue in this study. |

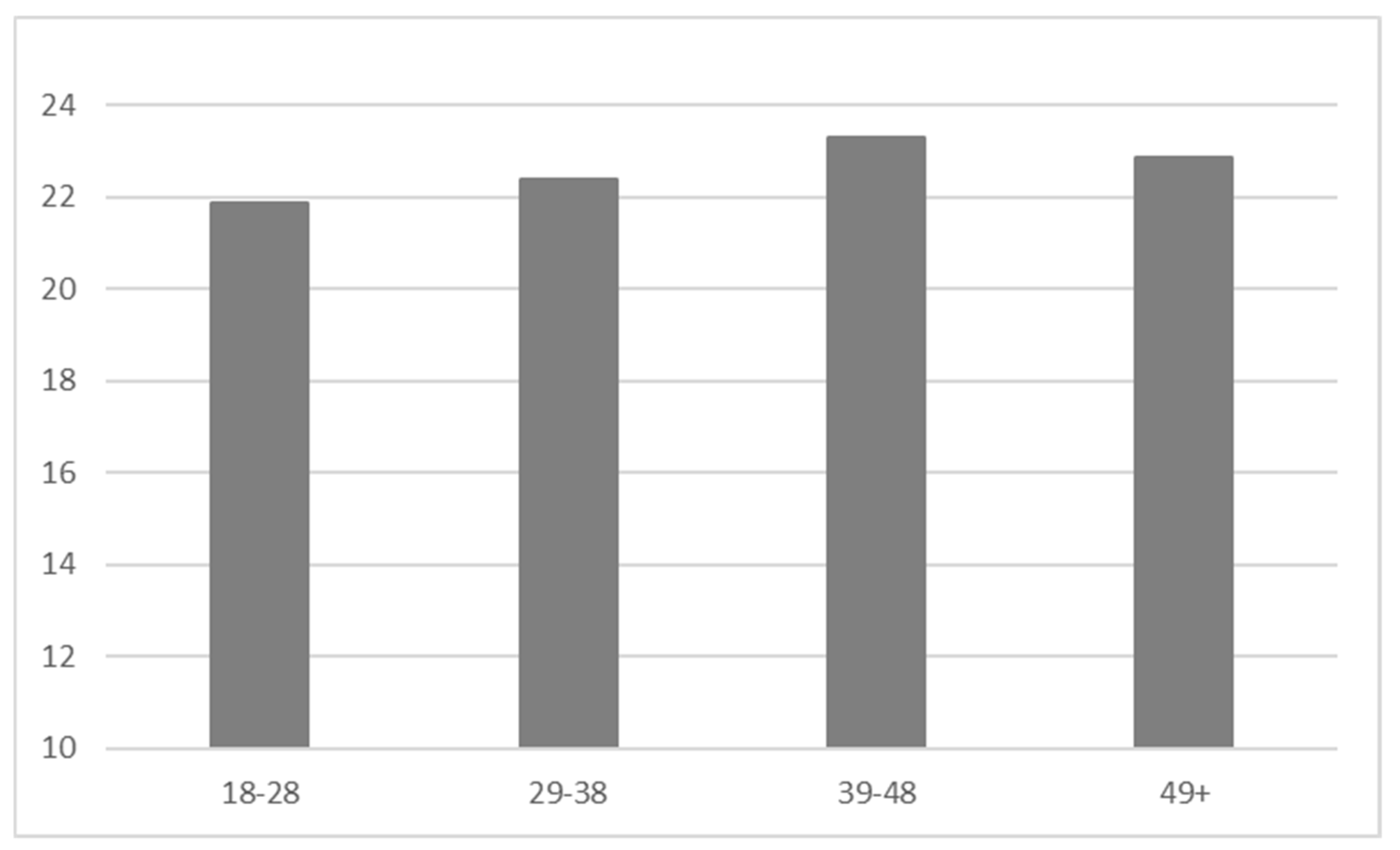

| 6 | We computed an additive index based on the six indicators of expected outcomes with regard to the police response to women. Each indicator ranged from one to five, with higher scores indicating higher expected performance outcomes. The overall index had a possible range of 6–30. Figure 3 shows the mean scores on the index for the four age categories (18–28, 29–38, 39–48, and 49+). The height of the bars in Figure 3 represents expected outcomes. Respondents in the 39–48 age bracket had the highest scores on the expected outcomes index, suggesting that they were the most optimistic about the ability of police to improve their response to crimes against women and the needs of female citizens. |

References

- Ahmad, Jaleel, M. E. Khan, Arupendra Mozumdar, and Deepthi S Varma. 2016. Gender-based violence in rural Uttar Pradesh, India: Prevalence and association with reproductive health behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 31: 3111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, Sofia, Sonia Bhalotra, and Nishith Prakash. 2021. Gender, Crime and Punishment: Evidence from Women Police Stations in India. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3827615 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Andersson, Thomas, and Stefan Tengblad. 2009. When complexity meets culture: New public management and the Swedish police. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 6: 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, Richard P., Youjae Yi, and Lynn W. Phillips. 1991. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly 36: 421–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Abhijit, Raghabendra Chattopadhyay, Esther Duflo, Daniel Keniston, and Nina Singh. 2021. Improving police performance in Rajasthan, India: Experimental evidence on incentives, managerial autonomy, and training. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13: 36–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, Micheal, and Roberb Ruh. 1976. Employee growth through performance management. Harvard Business Review 54: 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, Natasha K., and Shenyang Guo. 2012. Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bratton, William J., and Sean Malinowski. 2008. Police performance management in practice: Taking COMPSTAT to the next level. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2: 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Timothy A. 2015. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, Salvador, and Anders Grönlund. 2003. Measures vs. actions: The balanced scorecard in Swedish Law Enforcement. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 23: 1475–96. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, Roxanna. 1993. Violence against women: An obstacle to development. In Women’s Lives and Public Policy: The International Experience. Edited by Meredeth Turshen and Briavel Holcomb. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Shun-Hsing, Ching-Chow Yang, and Jiun-Yan Shiau. 2006. The application of balanced scorecard in the performance evaluation of higher education. The TQM Magazine 18: 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettiar, Anitha. 2015. Problems faced by hijras (male to female transgenders) in Mumbai with reference to their health and harassment by the police. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 5: 752–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chowdhury, Aparajita, and Manoj Manjari Patnaik. 2010. Empowering boys and men to achieve gender equality in India. Journal of Developing Societies 26: 455–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, Nancy A., and Ann W. Burgess, eds. 1996. Understanding Violence against Women. Washington, DC: National Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Léo-Paul. 2007. Asian Models of Entrepreneurship—From the Indian Union and the Kingdom of Nepal to the Japanese Archipelago: Context, Policy and Practice. Singapore: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, Léo-Paul. 2014. Asian Models of Entrepreneurship—From the Indian Union and Nepal to the Japanese Archipelago: Context, Policy and Practice, 2nd ed. Singapore: World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, James W., Jr., Pamela Brandes, and Ravi Dharwadkar. 1998. Organizational cynicism. The Academy of Management Review 23: 341–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKeseredy, Walter S., and Martin D. Schwartz. 2011. Theoretical and definitional issues in violence against women. In Sourcebook on Violence against Women, 2nd ed. Edited by Claire M. Renzetti, Jeffrey L. Edleson and Raquel Kennedy Bergen. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Den Hartog, Deanne N., Paul Boselie, and Jaap Paauwe. 2004. Performance management: A model and research agenda. Applied Psychology 53: 556–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, Panagiotis, Ioannis Kosmas, and Ioannis Douvis. 2017. Implementing the balanced scorecard in a local government sport organization. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 66: 362–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elefalk, Kjell. 2001. The balanced scorecard of the Swedish Police Service: 7000 officers in total quality management project. Total Quality Management 12: 958–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erausquin, Jennifer Toller, Elizabeth Reed, and Kim M. Blankenship. 2011. Police-related experiences and HIV risk among female sex workers in Andhra Pradesh, India. Journal of Infectious Diseases 204: S1223–S1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, David B., and Patrick J. Curran. 2004. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods 9: 466–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, Lisa Aronson, and Kathy A. McCloskey. 2011. Cultural issues in violence against women. In Sourcebook on Violence against Women, 2nd ed. Edited by Claire M. Renzetti, Jeffrey L. Edleson and Raquel Kennedy Bergen. Los Angeles: Sage, pp. 151–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Catherine, Stephen D. Mastrofski, Edward Maguire, and Michael D. Reisig. 2001. The Public Image of the Police. Alexandria: International Association of Chiefs of Police. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin, David A., Amy C. Edmondson, and Francesca Gino. 2008. Is yours a learning organization? Harvard Business Review 86: 109–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, Madhusudan. 2018. Gender equality, growth and human development in India. Journal of Poverty Alleviation and International Development 9: 68–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Patrícia, and Silvia M. Mendes. 2013. Performance measurement and management in Portuguese law enforcement. Public Money & Management 33: 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Greasley, Andrew. 2004. Process improvement within a HR division at a UK police force. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 24: 230–40. [Google Scholar]

- Greatbanks, Richard, and David Tapp. 2007. The impact of balanced scorecards in a public sector environment: Empirical evidence from Dunedin City Council, New Zealand. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 27: 846–73. [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, Gary A., and Victor Boutros. 2014. The Locust Effect: Why the End of Poverty Requires the End of Violence. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, Luciana E., Suchi Bansal, Soo Young Lee, Shirley Yan, Motolani Akinola, Márquez Rhyne, Alicia Menendez, and Melissa Gilliam. 2020. Understanding young women’s experiences of gender inequality in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh through story circles. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heise, Lori L., Alanagh Raikes, Charlotte H. Watts, and Anthony B. Zwi. 1994. Violence against women: A neglected public health issue in less developed countries. Social Science & Medicine 39: 1165–79. [Google Scholar]

- Himabindu, B. L., Radhika Arora, and Nuggehalli Srinivas Prashanth. 2014. Whose problem is it anyway? Crimes against women in India. Global Health Action 7: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, Tarah, Tullio Caputo, and Michael L. McIntyre. 2019. Beyond crime rates and community surveys: A new approach to police accountability and performance measurement. Crime Science 8: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, Carolyn, and Andrew Sanders. 2000. Police response to domestic violence. The British Journal of Criminology 40: 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Hyunseok, Larry T. Hoover, and Hee-Jong Joo. 2010. An evaluation of Compstat’s effect on crime: The Fort Worth experience. Police Quarterly 13: 387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassal, Nirvikar. 2020. Gender, law enforcement, and access to justice: Evidence from all-women police stations in India. American Political Science Review 114: 1035–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Robert, and Panupak Pongatichat. 2008. Managing the tension between performance measurement and strategy: Coping strategies. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 28: 941–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Robert. 2009. Conceptual foundations of the balanced scorecard. In Handbook of Management Accounting Research. Edited by Christopher S. Chapman, Anthony G. Hopwood and Michael D. Shields. Oxford: Elsevier, vol. 3, pp. 1253–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 1992. The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review 70: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 2001. Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management: Part 1. Accounting Horizons 15: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. 2004. The strategy map: Guide to aligning intangible assets. Strategy and Leadership 32: 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T. K. Vinod. 2017. Factors impacting job satisfaction among police personnel in India: A multidimensional analysis. International Criminal Justice Review 27: 126–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Eric G., Hanif Qureshi, Nancy L. Hogan, Charles Klahm, Brad Smith, and James Frank. 2015. The association of job variables with job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment among Indian police officers. International Criminal Justice Review 25: 194–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langworthy, Robert H. 1986. The Structure of Police Organizations. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Cheng-Hsien. 2016. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods 48: 936–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddox, Lucy, Deborah Lee, and Chris Barker. 2011. Police empathy and victim PTSD as potential factors in rape case attrition. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology 26: 112–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Edward R. 2003. Organizational Structure in American Police Agencies: Context, Complexity, and Control. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Edward R. 2004. Police Departments as Learning Laboratories; Washington, DC: The National Police Foundation. Available online: http://www.policefoundation.org/pdf/Ideas-Maguire.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Maguire, Edward R. 2005. Measuring the performance of law enforcement agencies. Law Enforcement Executive forum 5: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Edward R., and Devon Johnson. 2010. Measuring public perception of police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 33: 703–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, Shana L. 2008. “I have heard horrible stories...”: Rape victim advocates’ perceptions of the revictimization of rape victims by the police and medical system. Violence against Women 14: 786–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoli, R. N., and N. Ganapati Tarase. 2009. Crime against women: A statistical review. International Journal of Criminology and Sociological Theory 2: 292–302. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, Donald W. 1970. Generalized inverses, ridge regression, biased linear estimation, and nonlinear estimation. Technometrics 12: 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masal, Doris, and Rick Vogel. 2016. Leadership, use of performance information, and job Satisfaction: Evidence from police services. International Public Management Journal 19: 208–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, Judith, Lene Symes, Brenda K. Binder, J. Maddoux, and Rene Paulson. 2014. Maternal-child dyads of functioning: The intergenerational impact of violence against women on children. Maternal and Child Health Journal 18: 2236–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michau, Lori, Jessica Horn, Amy Bank, Mallika Dutt, and Cathy Zimmerman. 2015. Prevention of violence against women and girls: Lessons from practice. The Lancet 385: 1672–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogford, Elizabeth. 2011. When status hurts: Dimensions of women’s status and domestic abuse in rural northern India. Violence against Women 17: 835–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, Deepanshu, and Niharika Yadav. 2019. No State for Women? Why Crimes against Women Are Rising in UP. The Wire. Available online: https://thewire.in/women/crimes-against-women-violence-uttar-pradesh-unnao (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Moore, Mark Harrison. 2002. Recognizing Value in Policing: The Challenge of Measuring Police Performance. Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Mark Harrison. 2003. The “Bottom Line” of Policing: What Citizens Should Value (and Measure!) in Police Performance. Washington, DC: Police Executive Research Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Moullin, Max. 2017. Improving and evaluating performance with the public sector scorecard. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 66: 442–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, Chandan, Preet Rustagi, and N. Krishnaji. 2001. Crimes against women in India: Analysis of official statistics. Economic and Political Weekly 36: 4070–80. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, Bengt O., Stephen H. C. du Toit, and Damir Spisic. 1997. Robust Inference Using Weighted Least Squares and Quadratic Estimating Equations in Latent Variable Modeling with Categorical and Continuous Outcomes. Available online: http://gseis.ucla.edu/faculty/muthen/articles/Article_075.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- National Crime Records Bureau. 2019. Crime in India 2018; New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs.

- Neyroud, Peter. 2008. Past, present and future performance: Lessons and prospects for the measurement of police performance. Policing 2: 340–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcott, Deryl, and Necia France. 2005. The balanced scorecard in New Zealand health sector performance management: Dissemination to diffusion. Australian Accounting Review 15: 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcott, Deryl, and Tuivaiti Ma’amora Taulapapa. 2012. Using the balanced scorecard to manage performance in public sector organizations: Issues and challenges. International Journal of Public Sector Management 25: 166–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, Jean S., and Juana Flores. 2002. “Unpackaging” acculturation: Aspects of acculturation as predictors of traditional sex role attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 33: 320–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pico-Alfonso, Maria A., M. Isabel Garcia-Linares, Nuria Celda-Navarro, Concepción Blasco-Ros, Enrique Echeburúa, and Manuela Martinez. 2006. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women’s Health 15: 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, Shally. 1999. Medicolegal response to violence against women in India. Violence against Women 5: 478–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. 2015. Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. [Google Scholar]

- Ragavan, Maya, Kirti Iyengar, and Rebecca Wurtz. 2015. Perceptions of options available for victims of physical intimate partner violence in northern India. Violence against Women 21: 652–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichers, Arnon, John Wanous, and James Austin. 1997. Understanding and managing cynicism about organizational change. The Academy of Management Executive 11: 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollings, Kiah, and Natalie Taylor. 2008. Measuring police performance in domestic and family violence. Trends & Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice 367: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Rachel B. 2013. Implementation of a police organizational model for crime reduction. Policing: An International Journal 36: 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrico, Claudia S., Luís Miguel D. F. Ferreira, and Luís Filipe Cardoso Silva. 2013. POLQUAL—Measuring service quality in police traffic services. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences 5: 275–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtfeger, K. L., and B. S. N. Goff. 2007. Intergenerational transmission of trauma: Exploring mother–infant prenatal attachment. Journal of Traumatic Stress 20: 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, Jon M. 2010. Performance management in police agencies: A conceptual framework. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 33: 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, Lawrence W., Janell D. Schmidt, and Dennis P. Rogan. 1992. Policing Domestic Violence: Experiments and Dilemmas. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sibbet, David. 1997. 75 years of management ideas and practice 1922–1997. Harvard Business Review 75: 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Jay G., Sabrina C. Boyce, Nabamallika Dehingia, Namratha Rao, Dharmoo Chandurkar, Priya Nanda, Katherine Hay, Yamini Atmavilas, Niranjan Saggurti, and Anita Raj. 2019. Reproductive coercion in Uttar Pradesh, India: Prevalence and associations with partner violence and reproductive health. SSM Population Health 9: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, Margaret, and Jenny Morgan. 2018. Changing media coverage of violence against women. Journalism Studies 19: 1202–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Sanjay K. 2016. Heinous crimes against women in India. The Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies 41: 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Skogan, Wesley, and Kathleen Frydl. 2004. Fairness and Effectiveness in Policing: The Evidence. Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, Malcolm K. 2015. Measuring performance in a modern police organisation. In New Perspectives in Policing Bulletin. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Spohn, Cassia, and Katharine Tellis. 2015. Policing and prosecuting sexual assault: Assessing the pathways to justice. In Critical Issues in Violence against Women: International Perspectives and Promising Strategies. Edited by Holly Johnson, Bonnie S. Fisher and Veronique Jaquier. New York: Routledge, pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Srimai, Suwit, Nitirath Damsaman, and Sirilak Bangchokdee. 2011. Performance measurement, organizational learning and strategic alignment: An exploratory study in Thai public sector. Measuring Business Excellence 15: 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanko, Betsy A. 2007. From academia to policy making: Changing police responses to violence against women. Theoretical Criminology 11: 209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Murray B., and Colleen Kennedy. 2001. Major depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder comorbidity in female victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Affective Disorders 66: 133–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striteska, Michaela, and Marketa Spickova. 2012. Review and comparison of performance measurement systems. Journal of Organizational Management Studies 2012: 114900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, S., and Sharon Morrison. 2011. Marital violence and women’s reproductive health care in Uttar Pradesh, India. Women’s Health Issues 21: 214–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K. R., and N. J. Mathys. 2008. The aligned balanced scorecard: An improved tool for building high performance organizations. Organizational Dynamics 37: 378–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, Saumya. 2020. Patriarchal beliefs and perceptions towards women among Indian police officers: A study of Uttar Pradesh, India. International Journal of Police Science & Management 22: 232–41. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. 2018. Gender Inequality Index. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/GII (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Verma, Arvind, Hanif Qureshi, and Jee Yearn Kim. 2017. Exploring the trend of violence against women in India. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice 41: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Richard M., Fariborz Damanpour, and Carlos A. Devece. 2011. Management innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of performance management. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21: 367–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Shannon Drysdale. 2008. Engendering justice: Constructing institutions to address violence against women. Studies in Social Justice 2: 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Shannon Drysdale, and Cecilia Menjívar. 2016. Impunity and multisided violence in the lives of Latin American women: El Salvador in comparative perspective. Current Sociology 64: 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Shiyao, Jianguang Zhang, and Yunjia Sun. 2018. Armed police financial performance evaluation method design: A research perspective based on balanced scorecard. Advances in Social Science, Education, and Humanities Research 233: 987–92. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd, David L., Stephen D. Mastrofski, Ann Marie McNally, Rosann Greenspan, and James J. Willis. 2003. Reforming to preserve: COMPSTAT and strategic problem solving in American policing. Criminology and Public Policy 23: 421–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, James J., Stephen D. Mastrofski, and David Weisburd. 2007. Making sense of COMPSTAT: A theory-based analysis of organizational change in three police departments. Law & Society Review 41: 147–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski, Milk, and AlexDickson. 2001. Measuring performance in Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary with the balanced scorecard. Journal of the Operational Research Society 52: 1057–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2013. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihama, Mieko, Juliane Blazevski, and Deborah Bybee. 2014. Enculturation and attitudes toward intimate partner violence and gender roles in an Asian Indian population: Implications for community-based prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology 53: 432–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoellner, Lori A., Melanie L. Goodwin, and Edna B. Foa. 2000. PTSD severity and health perceptions in female victims of sexual assault. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13: 635–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Category | Number of Respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | Nongazetted | 265 | 85.5% |

| Gazetted | 45 | 14.5% | |

| Qualification | High School | 0 | 0.0% |

| Intermediate | 18 | 5.8% | |

| University graduate | 146 | 47.1% | |

| Postgraduate | 143 | 46.1% | |

| Doctoral | 3 | 1.0% | |

| Age (Years) | 18–28 | 99 | 31.9% |

| 29–38 | 60 | 19.4% | |

| 39–48 | 90 | 29.0% | |

| 49+ | 61 | 19.7% | |

| Gender | Male | 257 | 82.9% |

| Female | 53 | 17.1% | |

| Total | 310 | 100% |

| Independent Variables | β | S.E. | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Scorecard Dimensions | ||||

| Financial perspective | 0.321 | 0.056 | 5.70 | 0.000 |

| Customer perspective | 0.185 | 0.042 | 4.37 | 0.000 |

| Internal process perspective | 0.232 | 0.039 | 6.02 | 0.000 |

| Learning and growth perspective | 0.296 | 0.054 | 5.44 | 0.000 |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Age | 0.185 | 0.058 | 3.17 | 0.002 |

| Rank | −0.273 | 0.056 | −4.91 | 0.000 |

| Education | 0.149 | 0.058 | 2.56 | 0.011 |

| Male | −0.049 | 0.061 | −0.80 | 0.423 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kapuria, M.; Maguire, E.R. Performance Management and the Police Response to Women in India. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020058

Kapuria M, Maguire ER. Performance Management and the Police Response to Women in India. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(2):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020058

Chicago/Turabian StyleKapuria, Monica, and Edward R. Maguire. 2022. "Performance Management and the Police Response to Women in India" Social Sciences 11, no. 2: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020058

APA StyleKapuria, M., & Maguire, E. R. (2022). Performance Management and the Police Response to Women in India. Social Sciences, 11(2), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020058