COVID-19, Gender Housework Division and Municipality Size in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

3. Gender and Geography

4. Data, Methods and Hypotheses

4.1. Data

4.2. Methods

4.3. Hypotheses

5. Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

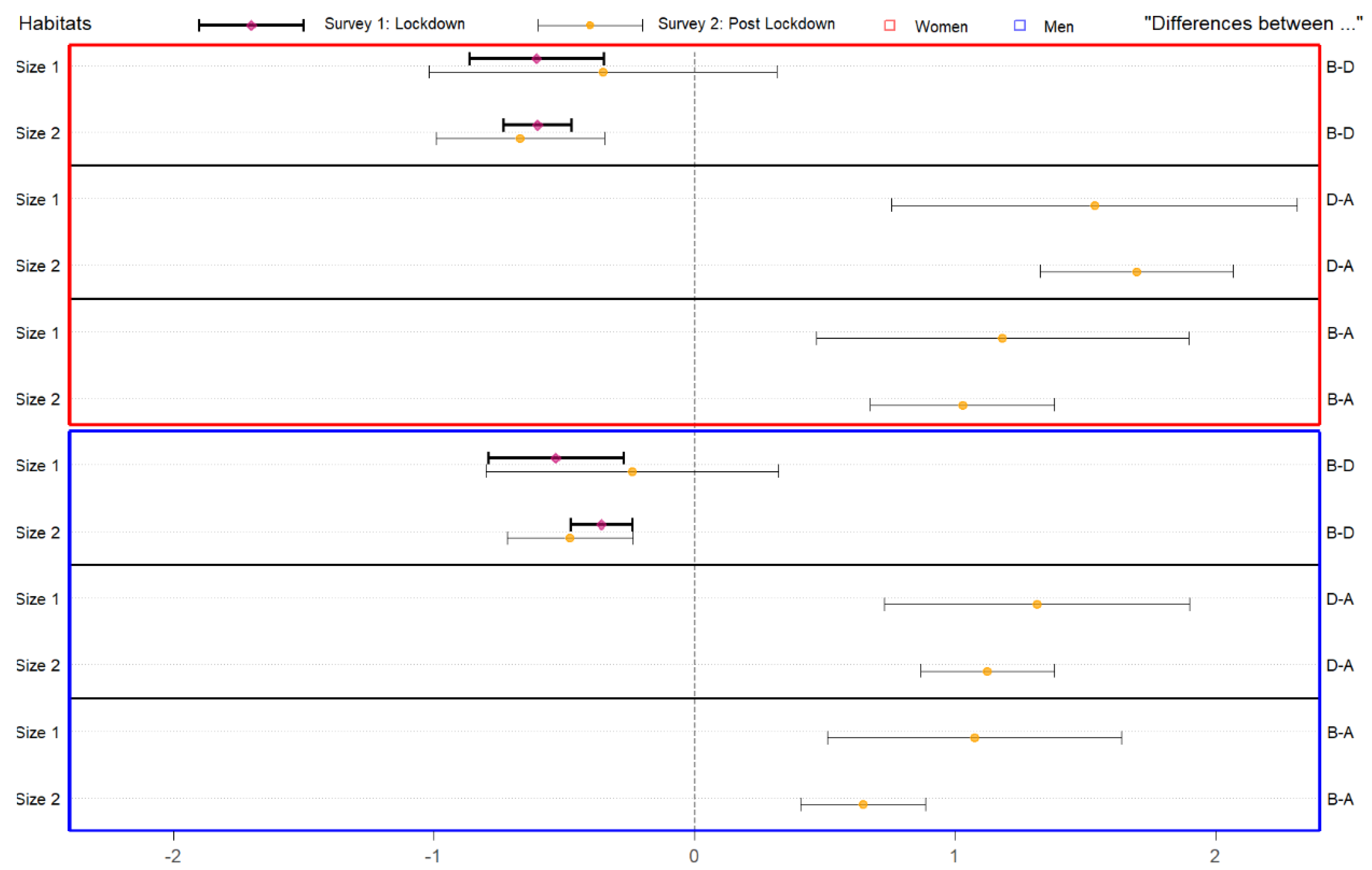

| Figure 2 Between Periods | Diff. | t | Interval | Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | p-Value | |||

| Before–During | |||||

| Su1Si1–Su1Si1 | −0.6056 | −4.5910 | −0.8643 | −0.3468 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si1–Su2Si1 | −0.3522 | −1.0405 | −1.0198 | 0.3154 | 0.2994 |

| Su1Si2–Su1Si2 | −0.6021 | −9.0807 | −0.7321 | −0.4721 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si2–Su2Si2 | −0.6682 | −4.0513 | −0.9920 | −0.3444 | <0.0001 |

| During–After | |||||

| Su2Si1–Su2Si1 | 1.5347 | 3.8861 | 0.7559 | 2.3134 | 0.0001 |

| Su2Si2–Su2Si2 | 1.6967 | 9.0172 | 1.3272 | 2.0660 | <0.0001 |

| Before–After | |||||

| Su2Si1–Su2Si1 | 1.1825 | 3.2612 | 0.4671 | 1.8979 | 0.0013 |

| Su2Si2–Su2Si2 | 1.0284 | 5.7187 | 0.6753 | 1.3815 | <0.0001 |

| Before–During | |||||

| Su1Si1–Su1Si1 | −0.5324 | −4.0222 | −0.7922 | −0.2723 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si1–Su2Si1 | −0.2397 | −0.8411 | −0.8013 | 0.3218 | 0.4012 |

| Su1Si2–Su1Si2 | −0.3570 | −5.9212 | −0.4753 | −0.2388 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si2–Su2Si2 | −0.4778 | −3.8887 | −0.7189 | −0.2367 | 0.0001 |

| During–After | |||||

| Su2Si1–Su2Si1 | 1.3148 | 4.4258 | 0.7295 | 1.9000 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si2–Su2Si2 | 1.1242 | 8.5839 | 0.8672 | 1.3812 | <0.0001 |

| Before–After | |||||

| Su2Si1–Su2Si1 | 1.0750 | 3.7616 | 0.5120 | 1.6381 | 0.0002 |

| Su2Si2–Su2Si2 | 0.6465 | 5.2751 | 0.4060 | 0.8870 | <0.0001 |

| Figure 3 Between Municipalities | Diff. | t | Interval | Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | p-Value | |||

| Before | |||||

| Su1–Su1 | 0.4336 | 4.0001 | 0.2292 | 0.6463 | <0.0001 |

| Su2–Su2 | 0.8741 | 3.6577 | 0.4021 | 1.3461 | 0.0004 |

| During | |||||

| Su1–Su1 | 0.4371 | 4.3609 | 0.2404 | 0.6337 | <0.0001 |

| Su2–Su2 | 0.5581 | 1.9181 | −0.0169 | 1.1331 | 0.0570 |

| After | |||||

| Su2–Su2 | 0.7201 | 2.2044 | 0.0747 | 1.3659 | 0.0290 |

| Before | |||||

| Su1Si1–Su1Si2 | −0.1718 | −1.6661 | −0.3743 | 0.0306 | 0.0961 |

| Su2Si1–Su2Si2 | 0.2114 | 1.0102 | −0.2019 | 0.6248 | 0.3139 |

| During | |||||

| Su1Si1–Su1Si2 | 0.0036 | 0.0349 | −0.1978 | 0.2050 | 0.9722 |

| Su2Si1–Su2Si2 | −0.0266 | −0.1161 | −0.4791 | 0.4258 | 0.9077 |

| After | |||||

| Su2Si1–Su2Si2 | −0.2171 | −0.9442 | −0.6712 | 0.2369 | 0.3465 |

| Before | |||||

| Su1Si1–Su1Si2 | 0.2395 | 3.0287 | 0.0844 | 0.3946 | 0.0025 |

| Su2Si1–Su2Si2 | 0.5595 | 3.3359 | 0.2295 | 0.8895 | 0.0010 |

| During | |||||

| Su1Si1–Su1Si2 | 0.3296 | 4.3553 | 0.1812 | 0.4780 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si1–Su2Si2 | 0.2936 | 1.5260 | −0.0850 | 0.6722 | 0.1280 |

| After | |||||

| Su2Si1–Su2Si2 | 0.2412 | 1.1987 | −0.1547 | 0.6370 | 0.2316 |

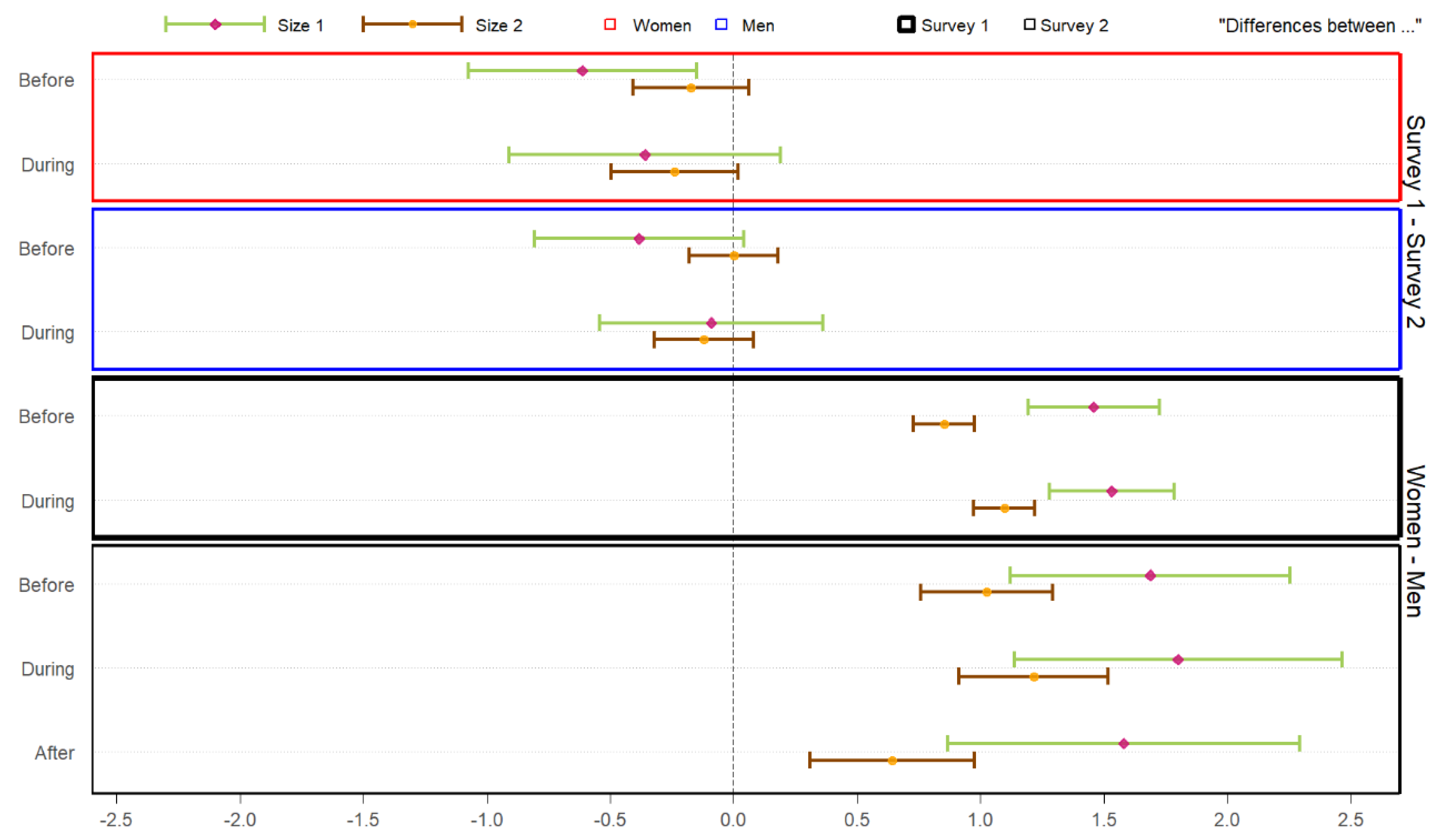

| Figure 4 Upper Between Surveys | Diff. | t | Interval | Adjusted | |

| Lower | Upper | p-Value | |||

| Before | |||||

| Si1W–Si1W | −0.6131 | −2.6250 | −1.0745 | −0.1515 | 0.0096 |

| Si2W–Si2W | −0.1725 | −1.4410 | −0.4077 | 0.0627 | 0.1502 |

| During | |||||

| Si1W–Si1W | −0.3596 | −1.2924 | −0.9104 | 0.1912 | 0.1986 |

| Si2W–Si2W | −0.2386 | −1.8155 | −0.4968 | 0.0196 | 0.0701 |

| Before | |||||

| Si1M–Si1M | −0.3830 | −1.7823 | −0.8071 | 0.0411 | 0.0764 |

| Si2M–Si2M | 0.0003 | 0.0031 | −0.1782 | 0.1788 | 0.9976 |

| During | |||||

| Si1M–Si1M | −0.0902 | −0.3937 | −0.5430 | 0.3624 | 0.6943 |

| Si2M–Si2M | −0.1205 | −1.1777 | −0.3212 | 0.0803 | 0.2393 |

| Figure 4 Lower Between Genders | Diff. | t | Interval | Adjusted | |

| Lower | Upper | p-value | |||

| Before | |||||

| Su1Si1 | 1.4576 | 10.764 | 1.192003 | 1.723347 | <0.0001 |

| Su1Si2 | 0.8522 | 13.393 | 0.7274779 | 0.9769836 | <0.0001 |

| During | |||||

| Su1Si1 | 1.5308 | 11.887 | 1.278141 | 1.783462 | <0.0001 |

| Su1Si2 | 1.0973 | 17.386 | 0.9735825 | 1.2210598 | <0.0001 |

| Before | |||||

| Su2Si1 | 1.6877 | 5.8803 | 1.1219 | 2.2535 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si2 | 1.0250 | 7.5256 | 0.7576 | 1.2924 | <0.0001 |

| During | |||||

| Su2Si1 | 1.8002 | 5.3451 | 1.1360 | 2.4643 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si2 | 1.2155 | 7.8873 | 0.9129 | 1.5180 | <0.0001 |

| After | |||||

| Su2Si1 | 1.5803 | 4.3698 | 0.8669 | 2.2937 | <0.0001 |

| Su2Si2 | 0.6431 | 3.7888 | 0.3098 | 0.9763 | 0.0002 |

References

- Adams-Prassl, Abigail, Teodora Boneva, Marta Golin, and Christopher Rauh. 2020. Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. IZA Discussion Papers 189: 104245. [Google Scholar]

- Adda, Jérôme, Christian Dustmann, and Katrien Stevens. 2017. The Career Costs of Children. Journal of Political Economy 12: 293–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemendinger, Jutta. 2020. Zurück in alte Rollen. Corona bedroht die Geschlechtergerechtigkeit. WZB Mitteilungen 168: 45–7. [Google Scholar]

- Alon, Titan, Matthias Doepke, Jane Olmstead-Rumsey, and Michèle Tertilt. 2020. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on gender equality. NEBER Working Paper 4: 62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Altintas, Evrim, and Oriel Sullivan. 2016. Fifty years of change updated: Cross-national gender convergence in housework. Demographic Research 35: 455–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altintas, Evrim, and Oriel Sullivan. 2017. Trends in fathers’ contribution to housework and childcare under different welfare policy regimes. Social Politics: International. Studies in Gender, State & Society 24: 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, Alison, Sarah Cattan, and Monica Costa Dias. 2020. How are mothers and fathers balancing work and family under lockdown. The Institute for Fiscal Studies, IFS Briefing Note BN290. [Google Scholar]

- Baylina, Mirea. 2019. Feminist Interventions: Southern Europe/Mediterranean. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies. Edited by Anthony M.Orum. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylina, Mireia, and Maria Rodó-de-Zárate. 2019. Mapping Feminist Geographies in Spain. Gender, Place & Culture 26: 1253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylina, Mireia. 2020. Dones i tornada al camp: Protagonistes de les noves dinàmiques rurals a Catalunya. Treballs de la Societat Catalana de Geografia 90: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck-Gernsheim, Elisabeth. 2006. Declining Birth Rates, and Gender Relations. Arxius de Ciències Socials 15: 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Suzanne M. 2000. Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography 37: 401–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, Suzanne M., Melissa A. Milkie, Liana C. Sayer, and John P. Robinson. 2000. Is Anyone Doing the Housework? Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor. Social Forces 79: 191–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, Alexander. 2015. The quantitative role of childcare for female labor force participation and fertility. Journal of the European Economic Association 14: 639–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blaskó, Zsuzsa, Eleni Papadimitriou, and Anna Rita Manca. 2020. How Will the COVID-19 Crisis Affect Existing Gender Divides in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, Francine D., Peter Brummund, and Albert Yung-Hsu Liu. 2012. Trends in Occupational Segregation by Gender 1970–2009: Adjusting for the Impact of Changes in the Occupational Coding System. Demography 50: 471–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blundell, Richard, Monica Costa Dias, Robert Joyce, and Xiaowei Xu. 2020. COVID-19 and inequalities. Fiscal Studies 41: 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, Sophie, Jo Foord, and Susan Mackenzie. 1982. Feminism and Geography. The Royal Geographical Society 14: 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, Sophie. 1989. Geografía feminista en Gran Bretaña: Una década de cambio. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 14: 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bruegel, Irene. 1973. Cities, women and social class: A comment. Antipode 5: 62–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, Pat. 1973. Social change, the status of women and models of city form and development. Antipode 5: 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Daniel L., Richard Petts, and Joanna R. Pepin. 2020. Changes in Parents’ Domestic Labor During the COVID-19 Pandemi. SocArXiv, May 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Heejung. 2020. Return of the 1950s Housewife? How to Stop Coronavirus Lockdown Reinforcing Sexist Gender Roles. The Conversation, March 30. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn-Schwartz, Ella, and Liat Ayalon. 2021. Societal Views of Older Adults as Vulnerable and a Burden to Society during the COVID-19 Outbreak: Results from an Israeli Nationally Representative Sample. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B 76: e313–e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Caitlyn, Leah Ruppanner, Liana C. Landivar, and William J. Scarboroug. 2021. The Gendered Consequences of a Weak Infrastructure of Care: School Reopening Plans and Parents’ Employment during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gender & Society 35: 180–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Caitlyn, Liana C. Landivar, Leah Ruppanner, and William J. Scarborough. 2020. COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work and Organization 28: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, Lyn, and Brendan Churchill. 2021. Unpaid Work and Care During COVID-19: Subjective Experiences of Same-Sex Couples and Single Mothers in Australia. Gender & Society 35: 233–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rocha, José María, and Luisa Fuster. 2006. Why Are Fertility Rates and Female Employment Ratios Positively Correlated across O.E.C.D. Countries? International Economic Review 47: 1187–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Boca, Daniela, Noemi Oggero, Paola Profeta, and Ma Cristina Rossi. 2020. Women’s and men’s work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Review of Economics of the Household 18: 1001–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, María Ángeles. 2019. La Riqueza Invisible del Cuidado. Valencia: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- England, Paula. 2010. The Gender Revolution: Uneven and Stalled. Gender & Society 24: 149–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farre, Lidia, Yarine Fawaz, Libertad Gonzalez, and Jennifer Graves. 2020. How the Covid-19 Lockdown Affected Gender Inequality in Paid and Unpaid Work in Spain. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3643198 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3643198 (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Forsberg, Gunnel, and Susanne Stenbacka. 2017. Creating and challenging gendered spatialities: How space affects gender contracts. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 99: 223–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, Liam, and Martin Heneghan. 2018. Pensions planning in the UK: A gendered challenge. Critical Social Policy 38: 345–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fraisse, Geneviève. 2003. Los dos Gobiernos, la Familia y la Ciudad. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, Sylvia, and Yue Qian. 2021. COVID-19 and the Gender Employment Gap among Parents of Young Children. Canadian Public Policy 35: 206–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuwa, Makiko. 2004. Macro-Level Gender Inequality and the Division of Household Labor in 22 Countries. American Sociological Review 69: 751–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Ballesteros, Aurora. 1982. El papel de la mujer en el desarrollo de la geografía. In Liberación y Utopía. Edited by M. Ángeles Durán. Madrid: Akal, pp. 119–41. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ramón, María Dolors. 1985. El Análisis de Género y la Geografía: Reflexiones en Torno a un Libro Reciente. Documents D’Analisi Geográfica 6: 133–43. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ramón, M. Dolors. 2005. Enfoques críticos y práctica de la geografía en España: Balance de tres décadas (1974–2004). Documents d’Anàlisi Geográfica 45: 139–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gershuny, Jonathan, and John P. Robinson. 1988. Historical changes in the household division of labor. Demography 25: 537–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerstel, Naomi. 2000. The Third Shift: Gender and Care Work Outside the Home. Qualitative Sociology 23: 467–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonalons-Pons, Pilar. 2015. Gender and Class Housework Inequalities in the Era of Outsourcing Hiring Domestic Work in Spain. Social Science Research 52: 208–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, Diana, Guillermina Miñón, and Hugo Ñopo. 2020. The Coronavirus and the challenges for women’s work in Latin America. UNDP LAC C19 PDS 18: 142. [Google Scholar]

- Hennekam, Sophie, and Yuliya Shymko. 2020. Coping with the COVID-19 crisis: Force majeure and gender performativity. Gender, Work & Organization 27: 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersch, Joni, and Leslie S. Stratton. 1994. Housework, Wages, and the Division of Housework Time for Employed Spouses. The American Economic Review 84: 120–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hersch, Joni, and Leslie S. Stratton. 2002. Housework and Wages. The Journal of Human Resources 37: 217–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, Lena, and Mareike Bünning. 2021. Parenthood as a driver of increased gender inequality during COVID-19? Exploratory evidence from Germany. European Societies 23: S658–S673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. 2021. ILO Monitor: Covid-19 and the World of Work, 7th ed. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Robert, and Christian Welzel. 2006. Modernización, Cambio Cultural y Democracia. Madrid: CIS. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Robert, and Pippa Norris. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change around the World. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, Robert. 1988. The Renaissance of Political Culture. American Political Science Association 82: 1203–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Regan M., Anwar Mohammed, and Clifton van der Linden. 2020. Evidence of Exacerbated Gender Inequality in Child Care Obligations in Canada and Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Politics & Gender 16: 1131–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Joan R., Javier García-Manglano, and Suzanne M. Bianchi. 2014. The motherhood penalty at midlife: Long-term effects of children on women’s careers. Journal of Marriage and Family 76: 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirchherr, Julian, and Katrina Charles. 2018. Enhancing the simple diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research Project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 13: e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreyenfeld, Michaela, and Sabine Zinn. 2021. Coronavirus & Care: How the Coronavirus Crisis Affected Fathers’ Involvement in Germany. Demographic Research 44: 99–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landivar, Liana Christin, Leah Ruppanner, William J. Scarborough, and Caitlyn Collins. 2020. Early Signs Indicate That COVID-19 Is Exacerbating Gender Inequality in the Labor Force. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 6: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraz, Beatriz, Jose M. Pavía, and Luis E. Vila. 2019. Beyond the gender pay gap. Convergencia 81: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraz, Beatriz, Rosa Roig, Cristina Aybar, and Jose M. Pavía. 2021. COVID-19 and the Gender Division of Housework, (Unpublished).

- Lewis, Jane. 1992. Gender and the Development of Welfare Regimes. Journal of European Social Policy 2: 159–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Jane. 1997. Gender and Welfare Regimes: Further Thoughts. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 4: 160–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Jane. 2001. The Decline of Male Breadwinner Model: Implications for Work and Care. Social Politics 8: 152–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Jo, and Ruth Panelli. 2003. Gender Research and Rural Geography. Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 10: 281–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Jo, Linda Peake, and Pat Richardson. 1988. Introduction: Geography and gender in the urban environment. In Women in Cities. Women in Society. Edited by Linda Peake Jo Little and Pat Richarson. London: Palgrave, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascherini, Massmiliano, and Martina Bisello. 2020. COVID-19 Fallout Takes Higher Toll on Women, Economically and Domestically. Dublin: Eurofound. [Google Scholar]

- McBrier, Debra Branch. 2003. Gender and Career Dynamics within a Segmented Professional Labor Market: The Case of Law Academia. Social Forces 81: 1201–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Helen J., Karen R. Wong, Kieu Nga Nguyen, and Komalee N.D. Mahamadachchi. 2020. Covid-19 and Women’s Triple Burden: Vignettes from Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Vietnam and Australia. Social Sciences 9: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraviglia, Cinzia, and Aurore Dudka. 2021. The gendered division of unpaid labor during the Covid-19 crisis: Did anything change? Evidence from Italy. International Journal of Sociology 51: 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, Janice, and M. Dolors García-Ramón. 1987. Geografía feminista: Una perspectiva internacional. Documents d’Anàlisi Geográfica 10: 147–57. [Google Scholar]

- Monk, Janice, and Susan Hanson. 1982. On not Excluding half of the Human in Human Geography. The Professional Geographer 34: 1, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Múñoz-Boudet, Ana M., Patti Petesch, Carolyn Turk, and Angélica Thumala. 2013. On Norms and Agency: Conversations about Gender Equality with Women and Men in 20 Countries. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications, p. 13818. [Google Scholar]

- Oláh, Livia S., Irena Kotowska, and Rudolf Richter. 2018. The New Roles of Men and Women and Implications for Families and Societies. In A Demographic Perspective on Gender, Family and Health in Europe. Edited by Gabriele Doblhammer and Jordi Gumà. Cham: Springer, pp. 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parsons, Talcott. 2002. The American Family: Its Relations to Personality and to the Social Structure. In Family: Socialization and Interaction Process. Edited by Talcott Parsons and Robert Freed Bales. London: Routledge, pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pavía, Jose M., Itziar Gil-Carceller, Alfredo Rubio-Mataix, Vicent Coll, José A. Alvarez-Jareño, Cristina Aybar, and Salvador Carrasco-Arroyo. 2019. The formation of aggregate expectations: Wisdom of the crowds or media influence? Contemporary Social Science 14: 132–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Virgilio, Cristina Aybar, and Jose M. Pavía. 2021. COVID-19 and Changes in Social Habits. Restaurant Terraces, a Booming Space in Cities. The Case of Madrid. Mathematics 9: 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Virgilio, Cristina Aybar, and Jose M. Pavía. 2022a. Dataset of the COVID-19 Lockdown Survey Conducted by GIPEyOP in Spain. Data in Brief 40: 107700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, Virgilio, Cristina Aybar, and Jose M. Pavía. 2022b. Dataset of the COVID-19 Post-Lockdown Survey Conducted by GIPEyOP in Spain. Data in Brief 40: 107763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, Richard J., Daniel L. Carlson, and Joanna R. Pepin. 2021. A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents’ employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 551–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Martin, Darren Smith, Hanna Brooking, and Mara Duer. 2020. Idyllic Ruralities, Displacement and Changing Forms of Gentrification in Rural Hertfordshire, England. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 66: 259–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, Kate. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16: 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, Herminia, and M. Dolors García Ramón. 2004. Female representation in academic geography in Spain: Towards a masculinization of the discipline? Journal of Geography and Higher Education 28: 135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, Malte, Kinga Makovi, and Anahit Sargsyan. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on gender inequality in the labor market and gender-role attitudes. European Societies 23: S228–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reskin, Barbara. 1993. Sex Segregation in the Workplace. Annual Review of Sociology 19: 241–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, Rosa. 2019. El déficit de cuidado. In Retos para el Estado Constitucional del Siglo XXI: Derechos, Ética y Políticas del Cuidado. Edited by Ana Marrades. Valencia: Tirant, pp. 161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld, Rachel A., and Gunn Elisabeth Birkelund. 1995. Women’s Part-Time Work: A Cross-National Comparison. European Sociological Review 11: 111–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, Jean Jacques. 1913. Emilio. Barcelona: Casa Editorial Maucci. [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté, Ana, and Antoni Tulla. 1992. Geografía y Género en España: Una aproximación a la Situación Actual. In La Geografía en España (1970–1990). Edited by Joaquín Bosque Maurel. Madrid: Fundación BBVA, pp. 277–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla, Almudena, and Sarah Smith. 2020. Baby Steps: The Gender Division of Childcare during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36: S169–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, N. Davis, and Theodore N. Greenstein. 2004. Interactive Effects of Gender Ideology and Age at First Marriage on Women’s Marital Disruption. Journal of Family Issues 25: 658–82. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, Beth Anne, and Daphne John. 1996. The Division of Household Labor. Annual Review of Sociology 22: 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Noguera, Carles, Andrea Hernández-Monleón, Juan Carbonell-Asins, and Salvador Méndez-Martínez. 2016. La brecha salarial. Propuesta de medida y análisis de la discriminación indirecta con la encuesta de estructura social. In Brecha Salarial y Brecha de Cuidados. Edited by Capitolina Díaz and Carles Simó. Valencia: Tirant, pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Skopek, Jan, and Thomas Leopold. 2019. Explaining Gender Convergence in Housework Time: Evidence from a Cohort-Sequence Design. Social Forces 98: 578–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, Haya, and Noah Lewin-Epstein. 2000. Women’s Part-Time Employment and Gender Inequality in the Family. Journal of Family Issues 21: 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidell. 2007. Experimental Designs Using ANOVA. Belmont: Thomson. [Google Scholar]

- Torns, Teresa, and Carolina Recio. 2012. Desigualdades de género en el mercado de trabajo: Entre la continuidad y la transformación. Revista de Economía Crítica 14: 178–202. [Google Scholar]

- Tzannatos, Zafiris. 1999. Women and Labor Market Changes in the Global Economy: Growth Helps, Inequalities Hurt and Public Policy Matters. World Development 27: 551–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Breeschoten, Leonie, and Marie Evertsson. 2019. When does part-time work relate to less work-life conflict for parents? Moderating influences of workplace support and gender in the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Community, Work and Family 22: 606–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Survey 1: Lockdown | Survey 2: Post Lockdown | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | Age groups | |||||||||

| 18–30 | 31–44 | 45–64 | >64 | 18–30 | 31–44 | 45–64 | >64 | |||

| Men | 10.3 | 21.4 | 48.5 | 19.8 | 45.7 | 11.1 | 21.9 | 45.0 | 22.0 | 54.7 |

| Women | 11.3 | 21.6 | 51.7 | 15.4 | 54.3 | 12.3 | 22.6 | 44.4 | 20.7 | 45.3 |

| 10.8 | 21.5 | 50.2 | 17.4 | 11.6 | 22.2 | 44.7 | 21.4 | |||

| Survey 1: Lockdown | Survey 2: Post Lockdown | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education groups | Education groups | |||||||

| Without | No Uni | Uni | Without | No Uni | Uni | |||

| Men | 1.2 | 36.2 | 62.6 | 45.9 | 5.0 | 36.1 | 58.9 | 54.6 |

| Women | 1.0 | 33.0 | 66.0 | 54.1 | 5.5 | 38.4 | 56.1 | 45.4 |

| 1.1 | 34.4 | 64.5 | 5.2 | 37.1 | 57.7 | |||

| Household Chores | |

|---|---|

| 1. Preparing the dinner | 8. Preparing midday meal |

| 2. Bathing dependent persons | 9. Dusting |

| 3. Playing with minors | 10. Cleaning the floor |

| 4. Leaving the house to look after other dependents | 11. Doing the washing |

| 5. Washing up after meals | 12. Ironing |

| 6. Helping with children’s homework | 13. Going out for grocery shopping |

| 7. Cleaning the bathroom | 14. Throwing out the rubbish |

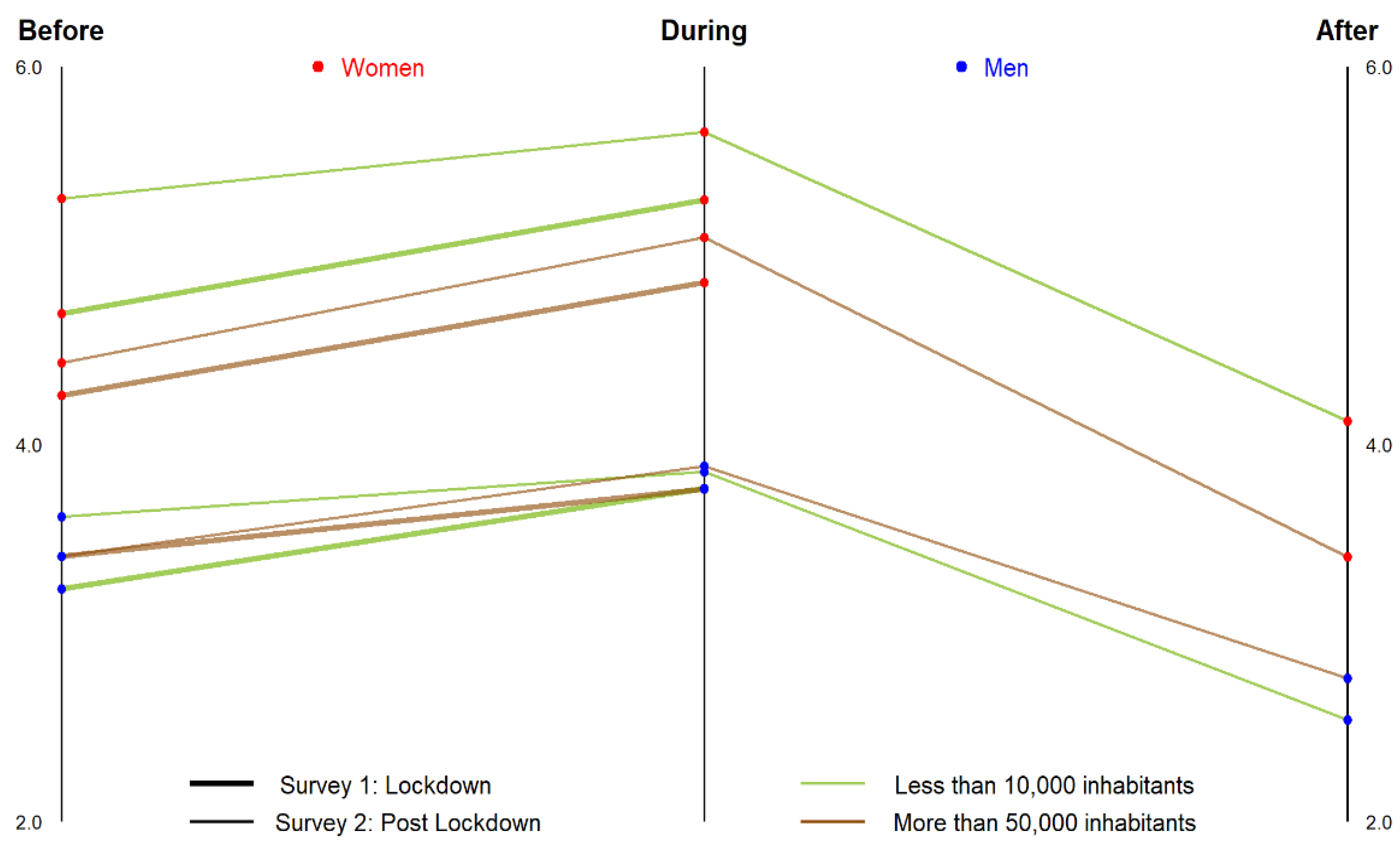

| Average Chores per Day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey 1: Lockdown | Survey 2: Post Lockdown | ||||

| Before | During | Before | During | After | |

| Minimum | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1st Quartile | 2.429 | 2.857 | 2.429 | 2.857 | 0.286 |

| Median | 3.857 | 4.286 | 3.857 | 4.571 | 3.000 |

| Mean | 3.958 | 4.446 | 4.024 | 4.537 | 3.081 |

| 3rd Quartile | 5.429 | 6.000 | 5.429 | 6.143 | 4.714 |

| Maximum | 13.429 | 13.000 | 11.857 | 11.571 | 11.714 |

| Sample size | 7540 | 1487 | |||

| # of women | 4106 | 641 | |||

| # of men | 3434 | 813 | |||

| Survey 1: Lockdown | Survey 2: Post Lockdown | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size 1 | Size 2 | Size 1 | Size 2 | |||

| Men | 524 | 1981 | 2505 | 118 | 514 | 632 |

| Women | 749 | 2178 | 2927 | 101 | 372 | 473 |

| 1273 | 4159 | 219 | 886 | |||

| Survey 1: Lockdown | Survey 2: Post Lockdown | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working Status | Working Status | |||||||

| Size 1 | Size 2 | Size 1 | Size 2 | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Men | 58.2 | 41.8 | 59.2 | 40.8 | 57.9 | 42.1 | 61.4 | 38.6 |

| Women | 55.0 | 45.0 | 57.9 | 42.1 | 57.0 | 43.0 | 65.2 | 34.8 |

| 56.3 | 43.7 | 58.5 | 41.5 | 57.5 | 42.5 | 63.0 | 37.0 | |

| Survey 1: Lockdown | Survey 2: Post Lockdown | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Dependents | Number of Dependents | |||||||

| Size 1 | Size 2 | Size 1 | Size 2 | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Men | 0.55 | 0.88 | 0.47 | 0.81 | 0.51 | 0.84 | 0.40 | 0.77 |

| Women | 0.70 | 0.94 | 0.52 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.98 | 0.51 | 0.83 |

| 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.49 | 0.81 | 0.58 | 0.91 | 0.45 | 0.79 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roig, R.; Aybar, C.; Pavía, J.M. COVID-19, Gender Housework Division and Municipality Size in Spain. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020037

Roig R, Aybar C, Pavía JM. COVID-19, Gender Housework Division and Municipality Size in Spain. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(2):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020037

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoig, Rosa, Cristina Aybar, and Jose M. Pavía. 2022. "COVID-19, Gender Housework Division and Municipality Size in Spain" Social Sciences 11, no. 2: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020037

APA StyleRoig, R., Aybar, C., & Pavía, J. M. (2022). COVID-19, Gender Housework Division and Municipality Size in Spain. Social Sciences, 11(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020037