1. Introduction

In US jurisprudence, the historical and continued intertwining of the psychiatric and penal systems raises philosophical questions of moral culpability and just legal procedure. As one example, the question of personal responsibility in the context of clinical pathology and human development plays out regularly in the death-penalty arena and is reflected in the so-called protected classes of defendants: people who were under the age 18 when the crime was allegedly commissioned (e.g.,

Roper v. Simmons (

2005)); people who sufficiently evidence intellectual disability, also referred to as intellectual developmental disorder (e.g.,

Atkins v. Virginia (

2002)); and people who are profoundly impaired by mental illness (e.g.,

Ford v. Wainwright (

1986)). The latter two classes illustrate the legalization—and criminalization—of clinical constructs. Despite overwhelming evidence that there is a tremendous overlap in people with serious mental illness (SMI) and people who are incarcerated in jail and prison, there remains some disagreement in the academic literature as to the nature of the overlap (e.g., causal, correlational, or spurious). Furthermore, the overlap may be greater than presently known, as the “criminal justice system woefully underidentifies and underreports the number of mental illnesses among the incarcerated” (

Scheyett and Crawford 2020, p. 159). The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic has magnified, complicated, and added to the myriad relationships between mental illness and incarceration in the United States.

Synthesizing the literature on COVID-19, incarceration in jails and/or prisons in the United States (hereafter referred to as US incarceration), and mental illness in a systematic fashion can contribute to knowledge-building and the future development of evidence-informed practices across community and institutional settings with people who experience mental illness. This body of scholarship may also be pertinent to raising legal challenges to the institutions themselves and rights violations that occur therein. In part, this article builds on the publication by

Johnson et al. (

2021) entitled

Scoping Review of Mental Health in Prisons through the COVID-19 Pandemic, which included all research articles across all countries addressing the mental health of imprisoned people or prison staff during COVID-19. The present review is intended to build on, and shade, that scoping review by (1) focusing on US healthcare and criminal legal systems and their conditions, logics, economic realities, and cultures; (2) including peer-reviewed commentary articles; (3) broadening the substantive scope to include COVID-19 and incarceration only, and COVID-19 and mental illness only, for the purpose of drawing inferences; and (4) providing analyses within each intersection. The purpose of this systematic literature review is to describe the current state of peer-reviewed publications (i.e., commentary and research articles) that address the impact of COVID-19 on mental illness, incarceration, and their intersection in the United States.

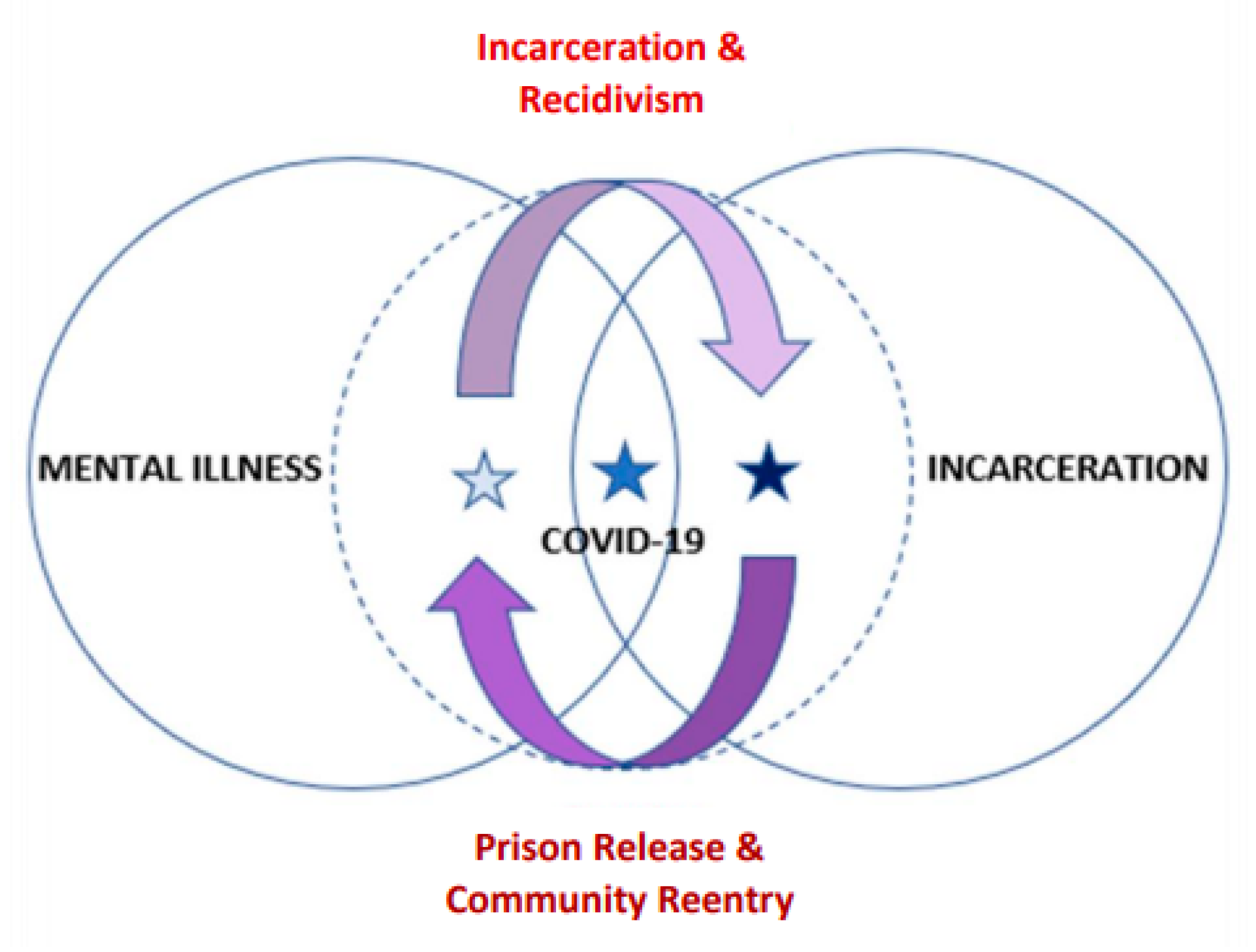

Figure 1 is a graphic representation of the conceptual relationships between COVID-19, mental illness, and incarceration in the United States.

2. Background: Overview of Mental Illness and Incarceration in the United States

Whereas the literature sample is inclusive of articles explicitly addressing COVID-19 (i.e., COVID-19 and mental illness; or COVID-19 and US incarceration; or COVID-19 and mental illness and US incarceration), the present background section provides an overview of the relationship between mental illness and incarceration in the United States. Issues of disparate sentencing, including death sentencing; overrepresentation in criminal legal systems; transinstitutionalization; and participation in diversionary programs, raise ethical concerns regarding the criminalization of mental illness itself and the recognition of rights for people with mental illness. These issues manifest as social exclusion, and an explanation of each one follows.

3. Serious/Mental Illness and the Carceral Setting

Mental illness is a highly complex construct and a term that is not without controversy. From the social model perspective, the term “illness” betrays the phenomenon as being too beholden to the medical, or disease, model. In this way, the term also arguably reifies “mental” as being biologically based, which in addition to committing a logical fallacy, is also reductionist. Mental illness is not homogenous, and not all so-called mental illnesses have a biological etiology, though some do. The social model is concerned with the process by which society constructs meanings around illness and disability, and the latent stigmas that reside within those demarcations, which are just as harmful as, and parasitic to, the overt mechanisms of exclusion that serve to demark the so-called deserving from the undeserving.

Though this article uses the broader term of “mental illness” to capture a greater sample of relevant literature that answers the research question at hand, it is important to note that a great deal of the literature focuses on the construct of serious mental illness (SMI). Clinically, serious mental illness entails a set of diagnoses that include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, dissociative disorder, major depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (

American Psychological Association 2014;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). Additionally, the National Institute of Mental Health defines SMI as follows: “a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities” (National Institute of Mental Health, Serious Mental Illness). People with SMI in the United States are at heightened risk for arrest, incarceration, and over-sentencing; lack of access to needed supports and services while incarcerated, and related rights denials; and, finally, they are more likely to receive the death penalty, despite the US Supreme Court decision in

Ford v. Wainwright (

1986) (

American Psychological Association 2014;

Bureau of Justice Statistics 2017;

Cloud and Davis 2013;

Lamb and Weinberger 2017;

Mental Health America 2016;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020).

3.1. Heightened Risk for Arrest, Incarceration, Over-Sentencing, and Death Sentencing

It has been estimated that over 55% of people in state prison and around 45% of people in federal prison are currently experiencing, or have recently experienced, mental health symptoms (

Bureau of Justice Statistics 2017;

Cloud and Davis 2013;

Lamb and Weinberger 2017;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). It is further estimated that the prevalence of SMI among individuals in jails and prisons is somewhere between 10 and 25%, which is significantly higher than the rate among the general US population (

American Psychological Association 2014;

Lamb and Weinberger 2017;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). In addition to being overrepresented in the carceral setting, people with SMI are at a higher risk for more severe sentencing and are more vulnerable to providing false confessions (

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). According to a study by

Lamb and Weinberger (

2017), risk factors for engaging in behavior that is considered to violate criminal code include the following: if the person does not believe they have mental illness; if the person is nonadherent to treatment, including pharmacological intervention; if the person has severe, acute psychotic symptoms and co-occurring substance use disorder; if the person has before become violent under stress; and if the person has shown a lack of desire for recovery (e.g., perhaps as a result of major depression).

With regard to death sentencing, the US Supreme Court’s 1986 decision in

Ford v Wainwright considered whether the state’s statutory scheme used for determining competency was constitutional or, rather, if it violated due process protections. The Supreme Court additionally considered whether a defendant, if found to be incompetent, could be constitutionally executed, or if such an execution violated protections from cruel and unusual punishment. In their decision, the US Supreme Court upheld, by a majority of five, that executing someone who is so mentally ill that they are not cognizant of the punishment they are about to suffer—and do not understand the rationale of that punishment—constituted cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment of the US Constitution (

Ford v. Wainwright 1986). The challenge of

Ford v. Wainwright (

1986) was that the Court did not define insanity, a legal construct that is rooted in a clinical professional paradigm. Despite constitutional prohibitions from execution,

Mental Health America (

2016) estimates that 20% of people on death row in the United States have SMI. This figure stands in contrast to the prevalence of 5.2% among adults in the general population (

National Institute of Mental Health 2019). Here again the complex, and often contradictory, connections between psychiatric and penal systems are manifest. Competency, insanity, psychosis, and mental illness are all separate constructs that emanate from different paradigms; however, they are conflated regularly, and this has fatal implications for defendants with disabilities in death-penalty cases.

3.2. Lack of Access to Supports and Services

There is broad consensus that jails and prisons are not equipped to appropriately address the comprehensive and intensive mental health needs of the people in their custody (

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). The issues are many: stressful conditions of the criminal legal system itself; mental health services and programs that are understaffed, underfunded, limited, inconsistent, and unpredictable; and the multiple related challenges to successful reentry into the community post-release (

Pope et al. 2013;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). As a result of these barriers, many incarcerated people with SMI will either not receive treatment or will receive treatment that is inappropriate and ineffective (

Cloud and Davis 2013;

Pope et al. 2013;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). Add to this that incarceration can be detrimental to the mental health of people without even a previous mental health diagnosis (i.e., measured increases in anxiety, depression, anger, cognitive disturbances, perceptual distortions, obsessive thoughts, paranoia, and psychosis), and it becomes easier to understand how devastating carceral conditions can be for someone with SMI (

Human Rights Watch 2009;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). According to Human Rights Watch, “This risk of harm is especially severe for prisoners who already have SMI, and this stress and lack of beneficial social contact and unstructured time can worsen and exacerbate symptoms of their mental illness” (2009, p. 3). Lack of supports and services is in violation of the

Americans with Disabilities Act (

1990) and, in this way, represents a civil rights violation (

Seltzer 2005).

4. Criminalization, Deinstitutionalization, and Transinstitutionalization

Lurigio (

2011a) defines the process of criminalization in the context of SMI as occurring when people with SMI are placed under arrest and incarcerated/detained, but while also lacking criminal intent. In other words, the so-called criminal behaviors are attributable to related clinical symptomology, as well as other relevant factors, and from a criminal jurisprudence perspective, resulting in a finding of

diminished moral culpability. Public-disorder charges are also referred to as nuisance offenses, and associated behaviors “can be unnerving, threatening, or even frightening to bystanders” (

Lurigio 2011a, p. 11). According to an article by

Seltzer (

2005), adults with mental illnesses are arrested at twice the rate of people without mental illnesses—for the same behaviors. This calls into question if the penological aim of public safety is met for people with mental illnesses, who are most often arrested for disorderly charges or other nuisance crimes: “Public safety is not protected when people who have mental illnesses are needlessly arrested for nuisance crimes or when the mental illness at the root of the criminal act is exacerbated by a system designed for punishment, not treatment” (

Seltzer 2005, p. 582). Not only are rights violated when people are denied treatment for mental illnesses while incarcerated, but the very same people who are likely candidates for these rights violations are also subjected to more frequent arrests and severe sentencing in the first place (

Seltzer 2005). In addition to rights violations, other collateral consequences include social stigmatization based on criminal status; the resulting challenges related to accessing housing, employment, and/or treatment services; and deportation (

Seltzer 2005).

The criminalization of mental illness, and SMI in particular, has been conceptually linked with the deinstitutionalization movement in the United States, and even more specifically with the resultant and grossly inadequate funding of community-based programming (

Lurigio 2011a). There is a consensus among scholars that the deinstitutionalization movement was stoked by the public’s increasing awareness via news media of the abuses and other atrocities occurring within the confined spaces of psychiatric hospitals: the creation of effective psychotropic medications that could be used, for example, to treat symptoms of schizophrenia; federal entitlement programs coupled with increasing reliance on the private sector; and the expansion of insurance to cover inpatient psychiatric care in general hospitals (

Lurigio 2011a). However, as a result of poor implementation, deinstitutionalization “never succeeded in providing adequate, appropriate, or well-coordinated outpatient treatment for large percentages of PSMI, above all those with the most severe and chronic mental disorders” (

Lurigio 2011a, p. 12).

Seltzer (

2005) noted the following:

Too often, the criminalization of defendants with mental illnesses begins with the failure of mental health programs to meet these individuals’ needs or to accept them into services because they have difficult problems (such as co-occurring substance abuse) or because they already have a criminal record….Ironically, community mental health programs often refuse to serve the very individuals who are most likely to benefit from their intervention and who are least appropriate for prosecution: those who have engaged in misdemeanors and who have low priority within mental health systems because they are not at risk of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization.

(pp. 580, 583)

The diminished ability of the mental health system to provide adequate, effective intermediate and long-term care for people with mental illnesses in the community has resulted in the overrepresentation of mental illness in US jails and prisons; this is the basic premise of the

transinstitutionalization argument (

Prins 2011). Scholars who are critical of this theory are so on the grounds that the relationship between deinstitutionalization and the overrepresentation of mental illness in US jails and prisons is not directly causal—and, importantly, there are other key variables at play. Lurigio, for example, contended that “harsh crime control policies and draconian drug laws, in particular, account for the apparently large numbers of PSMI who are arrested and incarcerated” (Abstract). The different views on transinstitutionalization presented here amount to how best to weight and position the variables.

5. Systemic Barriers and Procedural Challenges

There are a number of systemic barriers that place people with mental illness at risk for arrest and recidivism: poverty; homelessness and housing instability; unemployment; lack of access to meaningful treatment services; public misperceptions about mental illness, insanity, and future dangerousness; criminogenic environments; inconsistencies in access to pre-prison health services in the criminal justice system; and poor coordination of services across the criminal legal system following discharge, including the hospital and carceral settings (

American Bar Association 2006;

American Bar Association 2016;

Lurigio 2011a;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020;

Seltzer 2005;

Slade et al. 2016). Similarly, there are manifold procedural challenges that people with mental illnesses face once involved in the criminal legal system. For example, people with SMI may experience increased difficulty in providing meaningful assistance to their legal counsel; they may serve as poor witnesses owing to psychiatric- or communication-related issues; and depressive symptoms may result in such persons forgoing appeals or requesting a sentence of death (

Blume 2004;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). Additionally, people with SMI “stay incarcerated longer, are less likely to be approved for community supervision, are up to twice as likely to have their probation or parole revoked and return to jail or prison than others charged with similar offenses” (

Prins and Draper 2009, p. 717). Finally, while attorneys may use mental illness as a mitigating factor, it is just as often interpreted by decision-makers (i.e., judges and jurors) as an aggravating factor, owing to public misconceptions about mental illness and future dangerousness (

Mangels 2017;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). One approach to addressing the overrepresentation of SMI in the criminal legal system is through the use of diversionary programs, such as mental health courts.

6. Mental Health Courts as Controversial Treatment Models

Diversionary programs known as mental health courts bear mentioning when discussing mental illness in US jails and prisons. The rise of mental health courts occurred in response to the rising concern over the increasing presence of mental illness within the criminal justice system (

Seltzer 2005), with jails and prisons being noted as “the largest de facto treatment settings for the mentally ill” (

Lurigio 2011b, p. 75S). This brief section on mental health courts will offer a critical analysis of related challenges as presented by

Seltzer (

2005), who advocates for alternative, evidence-based programs that are able to avoid the same civil rights and policy issues the mental health court treatment model presents.

One fundamental philosophical flaw, according to

Seltzer (

2005), is that the presence of such courts signals an implicit acceptance of the rate at which people with SMI become involved with the criminal legal system in the first place. Additional issues that must be considered relate to voluntariness and informed consent:

Otherwise, singling out defendants with mental illnesses for separate and different treatment by the courts would violate the equal protection guarantee of the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment and would likely violate the 6th Amendment’s right to a trial by jury and the prohibition against discrimination by a state program found in the Americans with Disabilities Act…. Further complicating the voluntary election of mental health court involvement is the fact that such decisions are made when the defendant is likely to be under considerable stress.

To this end,

Seltzer (

2005) warned of the inherent coercive aspects of this treatment model.

7. Method

The current study represents an effort to systematically describe the available peer-reviewed scholarship, both commentary and research, on the topic of COVID-19, mental illness, and US incarceration. To this end, the authors posed the following research question: What is the current state of the peer-reviewed scholarship addressing the impact of COVID-19 on US incarceration, mental illness, and their intersection? To answer this question, the authors conducted a systematic review of the literature. According to Pati and Lorusso, in an article published in

Health Environments Research and Design Journal, a systematic literature review is a method of “collecting, critically evaluating, integrating, and presenting findings by adhering to standardized methodologies/guidelines in systematic searching, filtering, reviewing, critiquing, interpreting, synthesizing, and reporting of findings from multiple publications on a topic/domain of choice” (

Pati and Lorusso 2018, p. 15). In this vein, the remainder of the method section identifies the techniques and processes by which the authors conducted the review in order to enhance replicability and advance knowledge-building efforts.

8. Search Terms and Databases

The authors conducted a search of the academic literature separate from one another, using the same university online library system and the following search terms: “COVID-19 or coronavirus or pandemic” AND “mental health or mental illness or mental disorder or psychiatric illness” OR “prison or jail or incarceration or imprisonment or correction facilities or prisoners or inmates or criminals or offenders or incarcerated people”. To be considered for inclusion, articles needed to either be based in the United States or, if a global study, explicitly inclusive of the United States; address COVID-19 and mental illness, or COVID-19 and US incarceration, or COVID-19 and mental illness and US incarceration; and, finally, have been published or in press between December 2019 and October 2021 as either a peer-reviewed commentary or research article in an academic journal. The decision was made to include commentary articles in order to shade the research findings. The authors conducted their respective searches across the following databases in the university online library search system: APA PsychArticles, Criminal Justice, EBSCO, Proquest, Sage, and Social Work Abstracts. After searching the identified databases, the authors used the university online library system’s OneSearch function to cross-check the identified initial sample of the literature. A follow-up search was then conducted by using Google Scholar to ensure that as many eligible articles as possible were included in the final sample.

9. Final Sample Identification and Data Items Collected

The authors met weekly to compare and discuss their respective samples from the literature. Initially, the authors identified a combined sample of 38 articles by using the university online library search system and OneSearch function. Upon further review of the abstracts and later a line-for-line reading of the articles, the final agreed-upon sample was 20 articles. Multiple articles were removed, for example, because they were not based in the United States, or if global, they did not explicitly mention the United States. A second common reason for removal was for having a focus on HIV and/or substance use, as these articles fell beyond the scope of the present review—though it should be noted that such studies are intimately related to the project at hand and need to be included in a subsequent review for the significant insights they are likely to contribute. In order to ensure that as many eligible articles as possible were included in the final sample, the authors conducted a follow-up search, using Google Scholar, and this resulted in the identification of 18 additional articles. Of these additional articles, four were removed for being duplicative to the original sample. This resulted in a final sample of 34 peer-reviewed articles.

The authors collected the following data items, using Microsoft Excel: article number, article title, intersection, journal name, journal type, peer-review type, research type, name of commentary, substance of commentary, purpose, stated purpose, sample size, sample unit, method of data collection, and strength of evidence/limitations. Articles were organized and color coded according to intersection: Intersection #1 = COVID-19 and mental illness; Intersection #2 = COVID-19 and US incarceration; and Intersection #3 = COVID-19, mental illness, and US incarceration. Journal type was coded as follows: 1 = crime/criminology/criminal justice; 2 = medical; 3 = mental health; 4 = public health; 5 = public administration; and 6 = ethics. Peer-review type was coded as follows: 1 = commentary, and 2 = research. Research type was coded as follows: 1 = review/meta-analysis; 2 = program evaluation/needs assessment; 3 = conceptual analysis; 4 = statistical analysis; 5 = case study; and 6 = commentary/essay. As with the article-selection process, the authors met weekly and used the constant comparative method to discuss and come to consensus on article-data classification.

Table 1 presents the final sample of articles (

N = 34).

Table 2 presents the distribution of the peer-reviewed literature across intersection by journal and article type.

Table 3 presents the distribution of peer-reviewed literature across journal and research type.

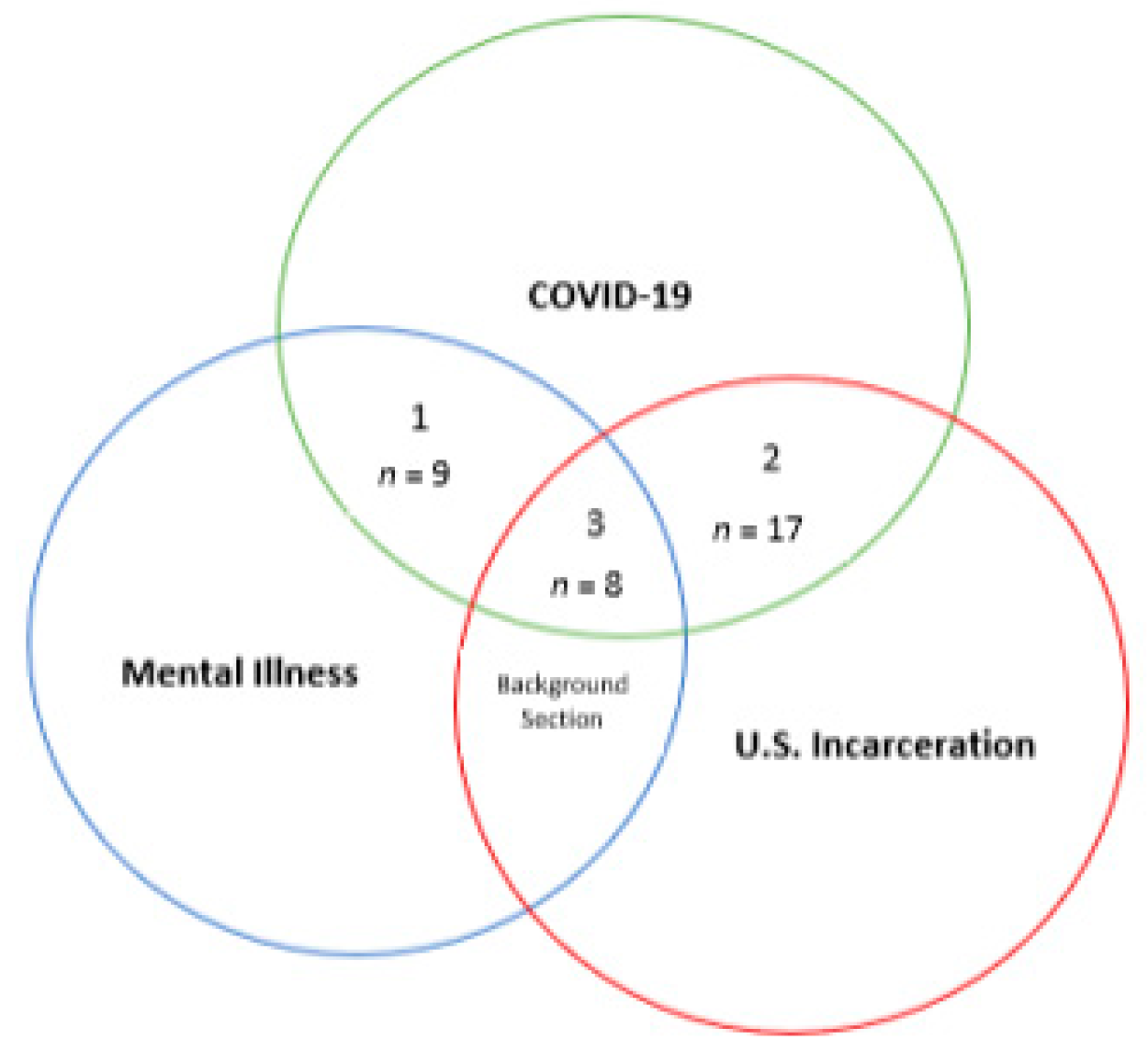

Figure 2 displays the distribution of the final literature sample by substantive intersection.

10. Sample Description

Most articles fell within Intersection #2: COVID-19 and US incarceration (n = 17; 50%). Most articles were published in mental health journals (n = 13), followed by medical journals (n = 8) and criminology/crime/criminal justice journals (n = 7). Intersection #1 presented the lowest ratio of research-to-commentary/editorial articles, with approximately 44% of the sample being commentary/editorial-based and 56% being research. The prevalence of commentary/editorial articles in Intersections #2 and #3 ranged from approximately 25% to 30%, with research articles comprising the remaining 70–75% of each intersection. Across the entire literature sample, research accounted for approximately two-thirds of articles. Most were categorized as conceptual analyses (n = 8) and case studies (n = 7). Two articles incorporated the emic perspective, with one article examining the perceptions of mental health professionals on the use of technology in clinical intervention and the other examining the perceptions of recently released persons regarding the use of technology in clinical intervention. The call for more inclusion of the emic understanding of people currently incarcerated and/or recently released was echoed across the literature sample and is supported by the findings of this systematic literature review. In order to develop the thematic findings that follow, the authors met weekly and as needed in iterative fashion until consensus was ultimately achieved.

11. Findings

11.1. Intersection #1: COVID-19 and Mental Illness

The authors identified the scholarly literature addressing COVID-19 and mental illness as Intersection #1. A total of nine peer-reviewed articles met the criteria for inclusion (n = 9). This sample of articles comprised 26.5% of the entire literature sample.

11.1.1. Theme # 1: Mental Illness and Risk of COVID-19 Infection Are Circular and Amplifying

COVID-19 has amplified stress and mental health conditions, with a disparately negative impact to populations with serious mental illness, intellectual/developmental disabilities, serious emotional disturbance, and substance use disorder (

Alavi et al. 2021;

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020;

Drake and Bond 2021;

Galea and Ettman 2021;

Riblet et al. 2021). One example of disparity for people with mental illness is that the median reduction in life expectancy is more than 10 years (

Galea and Ettman 2021). Mental disorders are classified as being psychotic, mood, or anxiety disorders (

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020). Psychotic disorders include schizophrenia, schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders, and brief psychotic disorders (

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020). Mood disorders include both episodes and disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder and manic episode) (

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020). Anxiety disorders include panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance related/addiction disorders, illness anxiety disorder, sleep disorders, and eating disorders (

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020). Populations susceptible to mental illness include older adults, professionals/healthcare professionals, children and teenagers, and people with past and family psychiatric history (

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020).

There is a myriad of links between mental illness and mortality. To this end, there are direct causal links between types of mental illness and mortality (e.g., mood–anxiety disorders and self-harm/suicide): people with severe depression are 2.2 times more likely to die by suicide than persons with mild depression (

Galea and Ettman 2021). There is also a link between the severity of mental illness and mortality: people with psychotic disorders have three-fold higher mortality rates than people without (

Galea and Ettman 2021). Stress exacerbates mental illness (

Alavi et al. 2021;

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020;

Bryan et al. 2020;

Drake and Bond 2021;

Galea and Ettman 2021;

Riblet et al. 2021). According to one study, primary COVID-19-related stressors included unexpected bills or expenses; the death of a close friend or family member; and a life-threatening illness or injury for a close friend or family member (

Bryan et al. 2020). The likelihood of past-month suicide ideation was significantly increased among people who reported ongoing strife with a spouse or partner, as well as serious legal problems (

Bryan et al. 2020). The likelihood of past-month suicide attempt was significantly increased among people endorsing stress about a life-threatening illness or injury of a close friend or family member (

Bryan et al. 2020). Among those who reported past-month suicide ideation, only stress about a life-threatening illness or injury of a close friend or family member was associated with significantly increased likelihood of past-month suicide attempt (

Bryan et al. 2020).

People with serious mental illness are both more likely to have premorbid health conditions, such as diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and are overrepresented in the carceral setting (

Cardenas et al. 2021). Furthermore, people with serious mental illness served by community mental health center outpatient and outreach teams experience chronically elevated risks of severe functional impairments; emergency department visits; psychiatric hospitalizations; harm behaviors; arrest and incarceration; food and water security; and homelessness (

Galea and Ettman 2021;

Kopelovich et al. 2021). In a circular way, people with serious mental illness are at a heightened risk of COVID-19 infection and poorer health outcomes, including disparities in access to healthcare (

Kopelovich et al. 2021). Gaps between federal guidelines and the needs and resources of the state and community manifest as barriers to virus-mitigation efforts—e.g., lack of psychiatric hospital beds and failure to maintain the quality of community-based care during community-based restrictions (

Alavi et al. 2021).

11.1.2. Theme #2: The Desire to Share Working Models for Community-Based Mental Health Intervention

A majority of articles in Intersection #1 were authored to share guidance and illustrate models of community-based psychiatry/clinical intervention during pandemic (

Alavi et al. 2021). Knowledge-building was often described as a desired outcome of the articles, and interdisciplinary collaboration was often showcased as a method for determining and implementing best (i.e., safe) practices during the more uncertain stages of COVID-19 (

Alavi et al. 2021). Over half of the literature in Intersection #1 (55.6%) was published in

Community Mental Health Journal, and the vast majority of articles emanated from the psychiatric professional paradigm.

This body of the literature offered criticism of the medical model, underlying assumptions, and implications for intervention. For example, the medicalization of social problems was expressly critiqued and linked with the “more is less paradox” in US healthcare spending—i.e., high fiscal expenditure with relatively poor outcomes (

Drake and Bond 2021, p. 1230). Proposed solutions included the adoption of a public-health/social-determinants lens to view and respond to social problems; using evidence-informed interventions; bolstering the continuum of care by adopting multiple service delivery models; implementation of preventative care strategies that requires transcending political barriers to secure public programs; tracking of hospitalization rates; clinician self-care; and asymptomatic screening of people coming from congregate living situations (e.g., hospitals/intensive care units, residential facilities, group homes, skilled nursing facilities, jails, prisons, and shelters) (

Bhattacharjee and Acharya 2020;

Cardenas et al. 2021;

Drake and Bond 2021;

Fetter 2021;

Kopelovich et al. 2021;

Riblet et al. 2021).

11.1.3. Theme # 3: Ambivalence toward Technology in Mental Health Intervention

Technology and its role in intervention were also highlighted with consistency and with tempered criticism. For example, technology was supported as being useful in the implementation of a triage schematic in which people with lesser impairment could meet with clinicians remotely (i.e., telehealth and tele-mental health) instead of in person (

Alavi et al. 2021;

Fetter 2021). One example raised was medication management (

Kopelovich et al. 2021). It was also noted that existing telehealth guidelines were insufficient to address the scope and range of pandemic-related needs (

Alavi et al. 2021). Furthermore, the use of technology may not be appropriate for people who present with cognitive disorganization or paranoia related to surveillance/technology and raises ethical issues related to privacy rights and patient access to care (

Kopelovich et al. 2021). In-person service provision was held as being optimal for initial patient assessment, rapport-building, performing in-depth mental status exams, assessing community functioning, determining the condition of clients’ homes, and general functional support (

Fetter 2021).

Technology was also noted as a facilitator for greater mental illness prevention. For example, as a mode of communication, technology can mitigate the harmful effects of social isolation and feelings of loneliness. In addition to the strengths of technology, associated limitations were noted. Access to technology was identified as a primary barrier to care and as one that could completely preclude the receipt of needed telehealth and tele-mental health services. Age was also an identified barrier, suggestive of both a generational learning curve and learning loss associated with incarceration (

Alavi et al. 2021;

Fetter 2021;

Kopelovich et al. 2021).

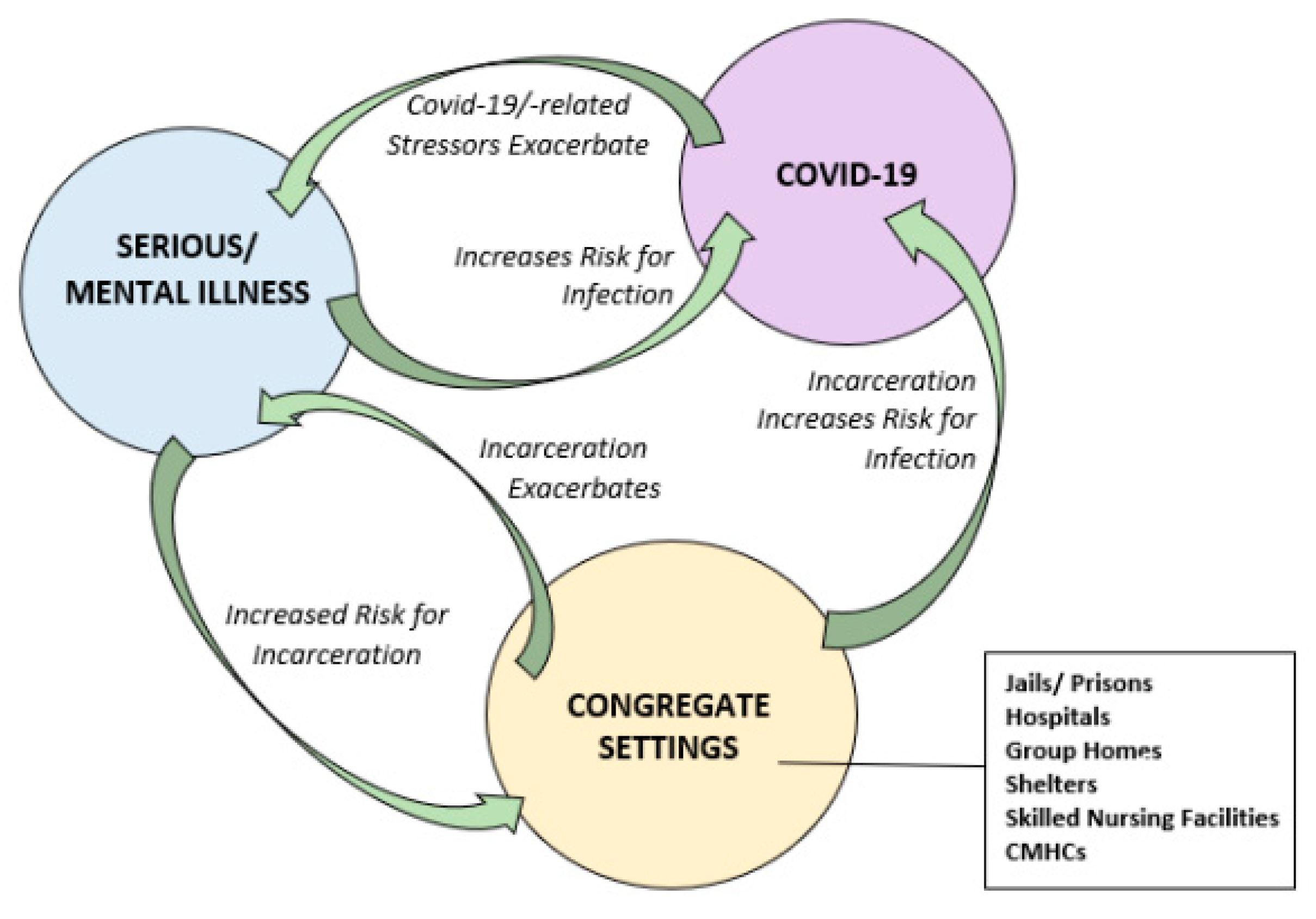

Figure 3 illustrates risk relationships from a community mental health perspective in Intersection #1: COVID-19 and mental illness.

11.2. Intersection #2: COVID-19 and US Incarceration

The authors identified the scholarly literature addressing COVID-19 and US incarceration as Intersection #2. A total of 17 peer-reviewed articles met the criteria for inclusion (n = 17). This sample of articles comprised 50% of the entire literature sample.

11.2.1. Theme # 1: Overlapping Populations Assume Heightened Risk for Incarceration and COVID-19 Infection, Amplifying Risk of Transmission

Articles in Intersection #2 acknowledged carceral settings as being major sites, hot spots, incubators, and conduits for COVID-19 (

Barnert et al. 2020;

Berkemeier Brelje and Pinals 2020;

Boucher et al. 2021;

Byrne et al. 2020;

Hummer 2020;

Lofaro and McCue 2020;

Novisky et al. 2020;

Reinhart and Chen 2020;

Vose et al. 2020). This was attributed to prisons and jails being congregate settings, as well as to mass incarceration and its correlates (

Barnert et al. 2020;

Berkemeier Brelje and Pinals 2020;

Boucher et al. 2021;

Byrne et al. 2020;

Clemenzi-Allen and Pratt 2021;

Desai et al. 2021;

Franco-Paredes et al. 2020;

Hummer 2020;

Lyons 2020;

Pyrooz et al. 2020;

Reinhart and Chen 2020). Given trends both in incarceration and in the demographics of the US population over the past four decades, the prison population is aging and disproportionately represented by people of color, people with various disabilities/co-morbidities, and people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (

Barnert et al. 2020;

Boucher et al. 2021;

Byrne et al. 2020;

Clemenzi-Allen and Pratt 2021;

Desai et al. 2021;

Franco-Paredes et al. 2020;

Hummer 2020;

Pyrooz et al. 2020;

Lyons 2020;

Novisky et al. 2020;

Pyrooz et al. 2020;

Reinhart and Chen 2020). This represents the same population who is at disparate risk for COVID-19 infection, illness, and death in the community (

Barnert et al. 2020;

Berkemeier Brelje and Pinals 2020;

Boucher et al. 2021;

Clemenzi-Allen and Pratt 2021;

Franco-Paredes et al. 2020;

Lyons 2020;

Novisky et al. 2020;

Reinhart and Chen 2020). The same populations are at an increased risk for criminal-legal-system involvement and, therefore, exposure to and adverse outcomes from COVID-19 (

Berkemeier Brelje and Pinals 2020;

Byrne et al. 2020;

Clemenzi-Allen and Pratt 2021;

Lyons 2020).

In addition to the disparate risks and burdens predicated on race and other demographic lines of difference, cycling between carceral and community settings (e.g., release and recidivism; staff and employee shift changes and turnover; and visitation) amplifies the risk of transmission (

Barnert et al. 2020;

Berkemeier Brelje and Pinals 2020;

Boucher et al. 2021;

Chan et al. 2021;

Franco-Paredes et al. 2020;

Hummer 2020;

Pyrooz et al. 2020;

Reinhart and Chen 2020). One study found that community cycling was the largest predictor of variance in infection rate and carried more predictive validity than race, income, public transit use, and population density (

Reinhart and Chen 2020). Efforts to curtail transmission, however, were seen as coming at the cost of rights and increasing the risk for negative health outcomes, thus perpetuating the cycle of public health disparities (

Boucher et al. 2021;

Clemenzi-Allen and Pratt 2021;

Lofaro and McCue 2020;

Lyons 2020;

Novisky et al. 2020;

Reinhart and Chen 2020).

Barnert et al. (

2020) pointed out the following: “Correctional health experts have called for limiting all nonessential movement while maintaining access to adequate legal and psychosocial support to the extent possible” (p. 964), suggesting that, where possible, policy must balance the concern for rights with that of safety (

Clemenzi-Allen and Pratt 2021;

Hummer 2020).

11.2.2. Theme #2: The Aging of the Prison Population Is Racialized and the Result of Unjust Policy

11.2.3. Theme # 3: Achieving Just Systems Requires Addressing the Social Determinates of Public Health Disparities

“The biological expression of these racial injustices include so-called deaths of despair (i.e., premature deaths due to suicide, drug overdose, and alcoholic liver disease) and having an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, accelerated aging, and acquisition of particular infections” (

Franco-Paredes et al. 2020, p. e10).

“Pandemic reality has brought humanity to an unprecedented collective realization of national and global interconnectedness in which the risks of vulnerability to disease for America’s incarcerated and the world’s poor, for example, threaten everyone, although clearly not equally” (

Reinhart and Chen 2020, p. 1417).

“Broadly speaking, the case of incarceration during COVID-19 offers an extreme example of how socially vulnerable people are especially burdened by disasters and crises. Correspondingly, the case invites us to radically rethink present policies. Reimagining the design of our criminal justice system is especially relevant in the context of ongoing demands for decarceration amidst mass #blacklivesmatter protests across the United States…” (

Lyons 2020, p. 292).

“Furthermore, social determinants of incarceration and poor chronic health are also risk factors for poor COVID-19-related outcomes outside prison. For example, poor black communities in the US have had disproportionately high rates of death from COVID-19” (

Berkemeier Brelje and Pinals 2020, p. 197).

“These barriers are compounded by disparities in vaccine rates for Black/African American patients, a population that has experienced a high burden of COVID-19 compared with White individuals” (

Clemenzi-Allen and Pratt 2021, p. 1322).

11.2.4. Theme # 4: The Inability to Socially Distance, Visitation, Shift Changes, Re/entry, & Recidivism Are Inherent Barriers to Lowering Transmission Risk and Indicate Needed Guidance on Release

These institutional policies were often combined with a call for a unified state and federal government policy response in the form of compassionate/early/targeted release (

Boucher et al. 2021;

Franco-Paredes et al. 2020;

Lyons 2020;

Novisky et al. 2020;

Vose et al. 2020), with one study pointing out the lack of evidence linking release with recidivism (

Byrne et al. 2020). Compassionate-release eligibility criteria were identified as follows: (1) chronic/serious medical conditions related to aging, (2) deteriorating mental or physical health that causes functional impairment in the correctional-facility setting, and (3) severity of symptoms such that conventional treatment options offer little likelihood for improvement (

Boucher et al. 2021). Release entails reentry, and effective reentry requires inter-systems communication, such as care coordination and case management; in this way, reentry programs are central to the discourse on prison release as a policy solution to viral transmission (

Desai et al. 2021).

Hummer (

2020) includes information from Pew Charitable Trust (2017) supporting the rapid influx of needed transition planning and services as a “strain on U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services, who are tasked with community supervision of federal offenders” (p. 1263).

When advocating for release on the grounds of public health concerns, authors appealed to data on the risk of recidivism among older adults, as such data supported a much lower risk, including for reoffence among older adults convicted of authoring a violent crime (

Boucher et al. 2021;

Franco-Paredes et al. 2020). Viable post-release settings were noted as follows: (1) skilled nursing facilities and nursing homes, (2) assisted living and adult foster homes, (3) informal care, such as through family- and community-based Medicaid Waiver programs, and (4) the public–private sector (

Boucher et al. 2021). Despite drawing these connections, homelessness was not explored as an outcome. Moreover, one article raised the criticism that release policies may allow public officials “to ‘cherry pick’ criminals with a more positive construction…while further perpetuating a negative view of those deemed too deviant to benefit…” (

Lofaro and McCue 2020, Abstract). In this way,

Lofaro and McCue (

2020) call attention to the normalizing forces and social hierarchies that are endemic to the release criteria that are predicated on type of offense and thereby mediated by moralizing judgments.

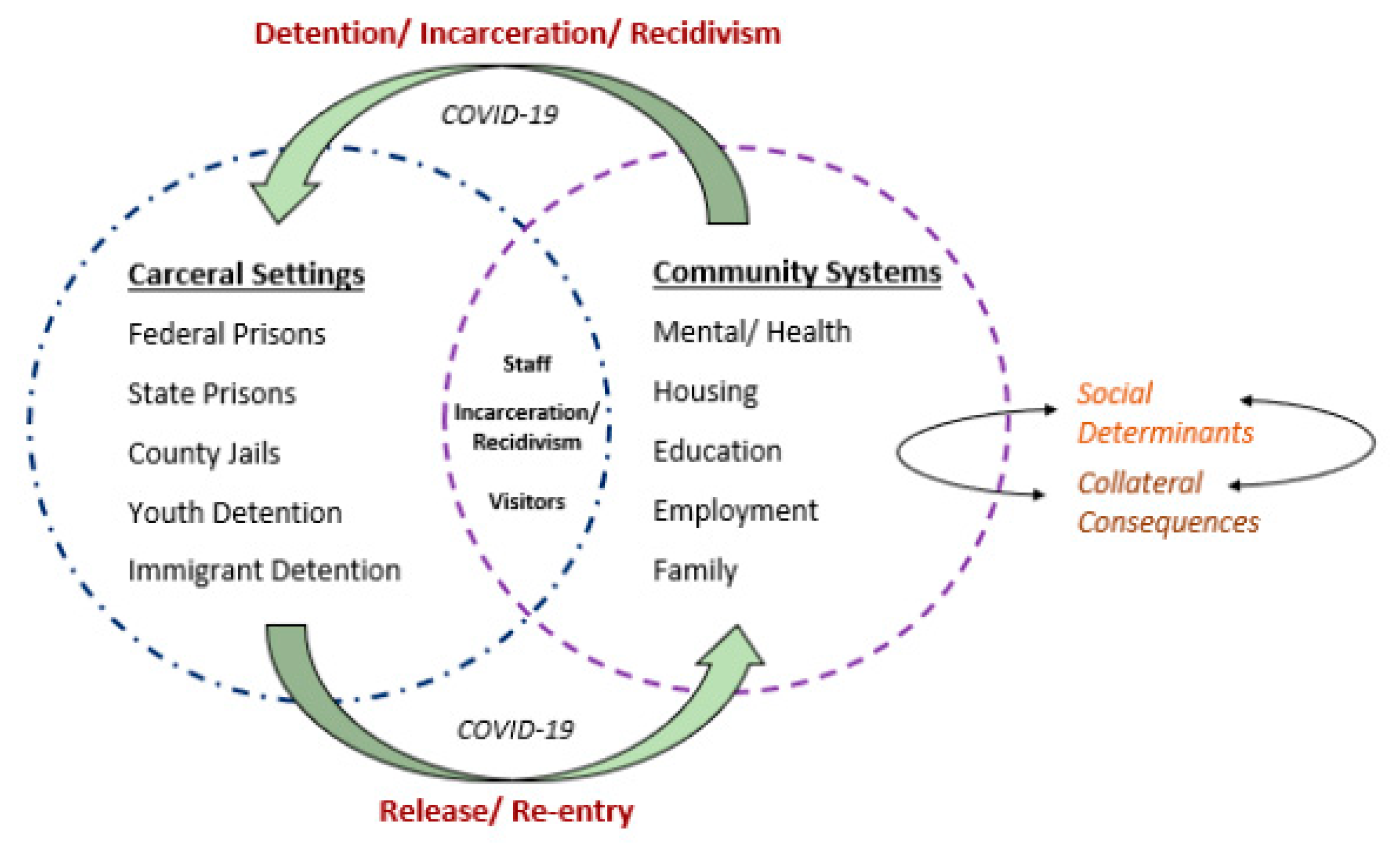

Figure 4 highlights the important role of social determinants in public-health disparities with regard to Intersection #2: COVID-19 and US incarceration.

11.3. Intersection #3: COVID-19, Mental Illness, and US Incarceration

The authors identified the scholarly literature addressing COVID-19, mental illness, and US incarceration as Intersection #3. A total of eight peer-reviewed articles met criteria for inclusion (n = 8). This intersection of articles represented 23.5% of the entire literature sample.

11.3.1. Theme #1: Serious/Mental Illness, Medical Disabilities, and People of Color Are Overrepresented across US Criminal Legal Systems

Articles in Intersection #1 examined the relationships between mental illness, race, and related disparities seen across carceral settings in the United States. It expanded upon

Theme #2: The Aging of the Prison Population is Racialized and the Result of Unjust Systems in Intersection #2, COVID-19 and US incarceration, by paying specific focus to issues of mental illness and other disabilities.

Krider and Parker (

2021) pointed to a 17% prevalence of serious mental illness symptom presentation among incarcerated populations. Articles noted the disparity in rate of mental illness and substance-use disorder between incarcerated populations and the general public (

Iturri et al. 2020;

Johnson et al. 2021;

Krider and Parker 2021;

Robinson et al. 2020;

Tadros et al. 2021).

Tadros et al. (

2021) widened the scope of impact to also include children and adolescents with incarcerated parents, whom they noted are more likely to experience depression, anger, and anxiety and exhibit more aggression, substance use, and school problems compared to their peers without incarcerated parents.

Mental illness is present in incarcerated individuals at an estimated rate of two to four times that found in the general population. According to

Robinson et al. (

2020), approximately one in seven incarcerated people had psychosis or major depressive disorder and one in five had substance-use disorder (

Robinson et al. 2020). Sometimes as the consequence of long-term antipsychotic medication, people with psychotic disorder also have higher rates of diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease—all of which are associated with higher rates of COVID-19 mortality (

Robinson et al. 2020). People with serious mental illness are more likely to experience negative COVID-19 medical outcomes, including death, and more likely to be incarcerated—where they are then exposed to

further increased risk for COVID-19 infection (

Iturri et al. 2020;

Mitchell et al. 2021). Compounding all of this is that people who are incarcerated are limited in their ability to seek and receive mental health services (

Iturri et al. 2020). Despite the prevalence of mental illness, many incarcerated individuals do not receive needed mental health treatment: one in six people in jail and one in three people in prison receive services (

Tadros et al. 2021).

Related to mental health treatment, articles were additionally concerned for the predicted negative impact of social distancing, visitation restrictions, and other COVID-19 measures on the mental health of incarcerated people (

Johnson et al. 2021). Primarily, articles were careful to draw out connections between social distancing and social isolation (

Iturri et al. 2020;

Mitchell et al. 2021).

Iturri et al. (

2020) drew parallels between social isolation and solitary confinement, and the deleterious effects on mental health even when no underlying condition is present. Social isolation was identified as a highly negative stressor and one that can lead to difficulty adjusting to incarceration, anxiety, depression, self-harm behavior, and suicidal ideation (

Iturri et al. 2020;

Robinson et al. 2020).

11.3.2. Theme # 2: COVID-19, Mental Illness, Incarceration, and Reentry Significantly Increase the Risk for Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors

In the United States, suicide is the 10th leading cause of death, and the rate has increased by 35% over the past decade (

Mitchell et al. 2021). People who are incarcerated in prisons are at an increased risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors, with suicide rates 3 to 9 times greater than in the general population across 24 countries (

Mitchell et al. 2021;

Robinson et al. 2020). The literature supported incarceration/confinement itself as a risk factor for suicide, noting that, even prior to COVID-19, correctional facilities did not provide adequate psychological care to people with mental health needs in their custody and were in short supply of psychiatrists across the nation (

Mitchell et al. 2021;

Robinson et al. 2020).

Reentry was identified as a time period of increased health risk, including suicide (

Barrenger and Bond 2021;

Mitchell et al. 2021). Individuals are at 13 times elevated risk for death due to homicide, cardiovascular disease, drug overdose, and suicide in the initial two weeks post-release from jails and prisons (

Barrenger and Bond 2021), with one article citing they are at a 14-times elevated risk for death due to suicide if released from prison (

Mitchell et al. 2021). Reentry was noted as a particularly stressful period of transition in which people have insufficient resources, lack social support, face unemployment challenges, and may be newly connected to mental health treatment; additionally, living conditions may pose additional health risks (

Barrenger and Bond 2021;

Mitchell et al. 2021).

Mitchell et al. (

2021) call for more research on COVID-19’s impact on suicidal thoughts and behaviors, hypothesizing that there is a perfect storm of conditions for increased suicide risk: economic impacts of COVID-19; other COVID-19 related losses, including the death of loved ones, friends, and community members; prevalence of preexisting mental illness in people who are incarcerated; lack of mental health services and other needed supports/resources; feelings of being a burden upon others; and visitation restrictions/social isolation.

Increased social isolation was linked to increased suicidal ideation and behavior among people incarcerated in prison (

Mitchell et al. 2021). People in prison with one or more psychiatric diagnoses were significantly more likely to report suicidal ideation and behavior; among people in prison with a history of attempted suicide, there were significantly greater reports of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, eating disorders, and psychoses than among people in prison without a history of suicide attempt (

Mitchell et al. 2021). Social supports were linked with decreased suicidal ideation among people in prison with major depressive disorder (

Mitchell et al. 2021).

11.3.3. Theme #3: Gaps in Systems of Care Increase the Risks of Adverse Outcomes

During the release and reentry process, there are disruptions in the care continuum that result in lack of medical care, mental health treatment, and housing and employment options (

Barrenger and Bond 2021;

Krider and Parker 2021;

Mitchell et al. 2021). Furthermore, the considered well-being of incarcerated people is not culturally prioritized (

Mitchell et al. 2021). According to

Barrenger and Bond (

2021), 75% of reentry programs either curtailed or outright cancelled their services as a result of COVID-19. In their same qualitative study utilizing emic perspective of the formerly incarcerated, telehealth services were problematic because participants did not have adequate resources (i.e., phones and internet) or were unfamiliar with how to operate the technology due to having been incarcerated over a period of years (

Barrenger and Bond 2021). In Krider and Parker’s study, however, interviewed professionals reported high levels of satisfaction with the virtual service options in both behavioral health and criminal justice settings (2021). The virtual delivery of behavioral and mental health services is the most common application of telehealth or telemedicine, which

Krider and Parker (

2021) note as holding promise for use in rural communities that experience low rates of mental health providers, geographic barriers, and heightened stigma around mental illness. To do so,

Krider and Parker (

2021) identified limited access to wireless internet, insufficient device capacity, and lack of stable internet coverage as barriers to access. They also note the promise of Medicaid expansion that occurred in response to COVID-19 (

Krider and Parker 2021).

Figure 5 brings into focus the heightened morality rate endemic to the COVID-19, mental illness, and incarceration feedback loop.

12. Discussion: Mental Health Treatment, Transinstitutionalization, and Risk of Death

Given the likelihood of another pandemic, it is imperative that US carceral systems and systems of care use this moment to better understand the cycling of injustice that COVID-19 has magnified. As Seltzer points out (

Seltzer 2005), the criminalization of defendants with mental illnesses is linked with the failure of mental health programs to meet mental health needs in the community and the exclusion of people from program participation due to the complexity of the mental health issue or due to an existing criminal record. These factors have bearing on transinstitutionalization in that people with SMI are at increased risk for arrest, being incarcerated longer, not being approved for community supervision, having their probation or parole revoked, and recidivism (

Prins and Draper 2009;

Seltzer 2005). People with SMI, who are overrepresented across US jails and prisons, also lack access to adequate supports and services while in penal custody (

Cloud and Davis 2013;

National Institute of Mental Health 2019;

Pope et al. 2013;

Scheyett and Crawford 2020). Finally, people with SMI are disproportionately represented on death row (

Mental Health America 2016;

National Institute of Mental Health 2019). A sentence of death is irreversible, represents extreme exclusion, and fulfills the intent of eugenics-based arguments regarding who in society should reproduce or not—arguments traditionally steeped in issues of disability, race, socioeconomic status, and criminality.

Though many articles identified release from the carceral setting as being an imperative policy solution, more research is needed to understand the corollary to release during pandemic—i.e., reentry during pandemic—and implications for the formerly incarcerated, their families, and communities. Such implications include adverse impacts to medical health and mental/behavioral health, including significant increased risk for death (e.g., suicide), when proper supports, resources, programs, and services are not in place. From a critical perspective, holding release as a penultimate goal without proper planning for next steps or proper funding is tantamount to calling for deinstitutionalization without investing in communities to make sure that such arrangements are feasible, sustainable, meaningful, and safe (

Lurigio 2011b). If early release is viewed as a policy solution to assumed risks of the incarcerated during pandemic, more scrutiny should be paid to diversionary programs, including the Mental Health Courts and the inherent coercive aspects of this treatment model that may result in rights violations (

Seltzer 2005).

From a public programming standpoint, the perspective of incarcerated people and people who have been released from incarceration must be included in this line of inquiry, especially with regard to perceptions of mental-health-service intervention modalities (e.g., tele-mental health). Including their voice inherently entails the inclusion of other historically and socially excluded voices in US society. People with mental illnesses, people with medical disabilities, and people of color are overlapping populations who are overrepresented across US criminal legal systems. These populations also assume the greatest risk of death, a risk that is further exacerbated by the overall aging of the incarcerated due to unjust policies—be the risk of death the result of COVID-19, suicide, or state and federal government sanctioned execution. The uneven distribution of risk of death among populations historically excluded from social, political, and economic participation in US society is antithetical to democratic principles of equality and justice.

From a mental-health-practitioner perspective, ethical engagement is not only the standard, but it is central to rapport building vis-à-vis demonstrated respect and trustworthiness. There may be very disparate perceptions regarding effectiveness and comfortability of internet-based treatment modalities between those providing the services and those receiving the services. Engagement without this consideration is not person-centered, and it is arguably paternalistic and unethical. With regard to insurance coverage and mental health intervention, Medicaid is the largest payer of services. Given the overlap between incarcerated populations and serious/mental illness, Medicaid plays a critical role in the covered care of people who are released from incarceration and who meet eligibility requirements in the United States. To this end, the authors recommend the expansion of Medicaid to all adults with incomes up to 138% or more of the federal poverty level; repeal of the “Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy”/the ability of the incarcerated to apply for Medicaid while in state penal custody as part of the reentry planning process; and additional funding for Medicaid Waiver programs. Moreover, a systematic needs assessment of reentry programs would help identify how to bolster such programming to meet the needs of individuals and communities during and after a pandemic and should incorporate the perspectives of program staff and individuals in receipt of reentry services.

Finally, the above suggestions are placeholders and placeholders are risky because they allow unjust systems to continue to operate without accountability. At its core, incarceration is an apparatus of social normalization and exclusion. People who are today most at risk for criminal-legal-system involvement and rights violations are the same people who have a history of institutionalization and rights violations in the United States—be it psychiatric (e.g., asylums) or economic (e.g., slavery). These are doubtless issues of social, racial, economic, and environmental justice. They are not issues that demand reform of the status quo in the form of more and varied placeholders; they are issues that demand a different approach altogether—an approach that reflects the humanistic and egalitarian values inherent to the logos and ethos of a modern democratic society where rights are distributed and recognized equally and without prejudice.

13. Conclusions

In 2019, the viral pandemic known as COVID-19 touched and indelibly impacted the global community, including the United States. Throughout this time, standard practices were constantly changing to protect the medical safety of the general population. The United States counted over 127 million COVID-19 infections and over 2.5 million deaths (

Johnson et al. 2021). The impact of COVID-19 was particularly onerous for the incarcerated. As the United States is the leading incarcerator of the world, and because the US carceral system represents the nation’s largest de facto mental-health-treatment setting (

Lurigio 2011b), this placed incarcerated people with serious/mental illness in the United States at a disparately high risk for adverse outcomes that included risk of COVID-19 infection and other medical illness, lack of access to mental health treatment and exacerbated symptomology/deterioration, and death by suicide and drug overdose. The purpose of this systematic literature review was to describe the current state of peer-reviewed publications (i.e., commentary and research articles) that addressed the impact of COVID-19 on mental illness, incarceration, and their intersection in the United States. The authors then used the constant comparative method to identify salient themes across three intersections. Themes in Intersection #1 (i.e., COVID-19 and mental illness) were identified as follows:

Mental illness and risk of COVID-19 infection are circular and amplifying;

The desire to share working models for community-based mental health intervention;

Ambivalence toward the role of technology in mental health intervention.

Themes in Intersection #2 (i.e., COVID-19 and US incarceration) were identified as follows:

Overlapping populations assume heightened risk for incarceration and COVID-19 infection, amplifying risk of transmission;

The aging of the prison population is racialized and the result of unjust policy;

Achieving just systems requires addressing the social determinates of public health disparities;

The inability to socially distance, visitation, shift changes, re/entry, and recidivism are inherent barriers to lowering transmission risk and indicate needed guidance on release.

Finally, themes in Intersection #3 (i.e., COVID-19, mental illness, and US incarceration) were identified as follows:

Serious/mental illness, medical disabilities, and people of color are overrepresented across US criminal legal systems;

The intersection of COVID-19, mental illness, incarceration, and reentry significantly increase the risk for suicidal ideation and behaviors;

Gaps in systems of care increase the risks for adverse outcomes.

For people with serious/mental illness, social exclusion manifests as overrepresentation in criminal legal systems; disparate sentencing, including death sentencing; non-voluntary participation in diversionary programs; lack of access to mental health programs and services; transinstitutionalization; and increased risk of mortality (e.g., suicide and COVID-19 infection). These issues raise ethical concerns regarding the criminalization of mental illness itself and the recognition of rights for people with mental illness, as well as how state and federal tax revenue is being allocated to care for the people of the United States—or not. Implications for respective US policies, programs, and systems were discussed, along with respective recommendations.