Abstract

This paper utilizes narrative inquiry to examine the effect of COVID-19 on political resistance, focusing on education as a key site. Based on survey and interview data the paper considers parents’ perspectives about the impacts of COVID-19 and racial inequalities in their children’s schooling. Two narrative types are constructed and analyzed: consensus narratives and parenting narratives that refute an overarching, manufactured political narrative in the United States of “divisiveness” about race and education, while also identifying the layers and complexities of individual parents’ everyday lives raising and educating children.

1. Introduction

2020 was a pivotal year of ruptures. The COVID-19 pandemic and global Black Lives Matter movement (BLM), together surfaced deeply rooted inequities and divisiveness, which have revitalized debates about schooling and its purpose. This paper draws on a project COVID-19 & Racial Justice in Urban Education: New York City (NYC) Parents Speak Out, which explores the experiences and perspectives of parents and guardians during the unprecedented school year of 2020–2021. The mixed method study of interactive survey and interview data asked three questions: How do NYC parents/guardians identify and understand the impacts of COVID-19 and racial inequalities on their children’s schooling? How do parents make sense of and respond to the challenges? What are their commonalities and differences?

This Special Issue explores the usefulness of narrative inquiry as an effective tool for examining political resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our paper contributes to this effort in two ways: first, by identifying education as a key site of resistance and focusing in on the twin impacts of COVID-19 and racial harm and violence on children’s schooling from parents’ perspectives; and second by introducing a unique mixed methodology that examines the relationship between two types of narratives—consensus narratives that we identified in the interactive survey results and parenting narratives constructed from the interview data.

Our discussion and analysis of the consensus narratives paint an important picture of parents’ desires for change in schools. We feature a parent alliance around teaching about race, racism and inclusion, which refutes an overarching, manufactured political narrative of “divisiveness” about race and education. We found that overall, parents support opening up, rather than closing down, school conversations about hard and uncomfortable histories and realities that children should learn. To flesh out and understand the complexities of this alliance, we analyze three parenting narratives, highlighting the concerns of individual parents as they pursue their desires for change about how their children learn about racism. Careful listening to these parents’ stories of everyday events demonstrates how they use identity building tools and position themselves in multiple ways to reflect on the goal of teaching racial justice. Together, these two narrative types are in dialogue, building toward, rather than away from, consensus, which in itself is a lever for change. In this paper we set the context, unpack the research methods and design (complete with statements, participant characteristics, and opinion groups), and share findings grounded in consensus narratives and narrative inquiry.

2. Setting the Context

In March 2020, when New York City (NYC) became an early epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic, the NYC Department of Education (DOE), the United States’ (U.S.) largest public school system with approximately 1.1 million students, along with charter, catholic, and other NYC schools, went fully remote as the city went into lockdown. In school systems all across the world, in the midst of uncertainty and anxiety, students and their families were forced to manage the challenges of the pandemic, including the trauma of sickness and death, while adapting to online learning along with their teachers and administrators. Many households had several children learning remotely alongside parents working remotely. For NYC parents and guardians who returned to work in person in fall 2020, finding childcare for their children during the school day became an urgent need.

People of color and those living in poverty were the most adversely impacted by the pandemic with higher rates of cases, mortality and a rapid rate of infection (Bambra et al. 2020). The impact of these disparities made decision-making all the more fraught with challenges as school districts struggled to meet the unique needs of families across regional, racial and economic lines. These disparities shaped parents’ decisions about sending children back to school for fear of putting family members at-risk. Racial differences about school safety and precautions became evident, especially in NYC, according to polling.1

Meanwhile, racist rhetoric about the cause of the pandemic was mobilized against Asian Americans. At the outset of the pandemic, then-President Trump referred to COVID-19 as “the Chinese virus” and “Kung Flu”, placing the blame for the virus on Chinese people. As a result, Asian-American communities began to see an uptick in racism, both online and in person (Gao and Sai 2021; Zhu 2020; Cheng and Conca-Cheng 2020) and Anti-Asian racism peaked in NYC. Then, on 25 May 2020, while the city and much of the country was still in lockdown, George Floyd—and unarmed Black man—was murdered after being handcuffed and pinned to the ground under the knee of a white police officer. The episode was captured on video and went viral, igniting protests that spread throughout the country and globally in the months that followed, leading to a racial justice movement not seen since the Civil Rights protests of the 1960s. More murders by police officers followed, including Brianna Taylor—a young unarmed Black woman—in Louisville, KY, who was mistakenly shot and killed by police officers, while they executed an unconstitutional search warrant in a failed raid with deadly consequences.

An important layer of resistance within the “pandemic story” and its racialized impact is that many schools did successfully add an increased emphasis on race, racism and racial justice—even during the challenges of COVID-19. This included a more expansive and multi-perspective history of slavery and recognizing and celebrating the contributions of people of color. By 2021, many U.S. school districts had adopted Culturally Responsive and Sustaining frameworks2 that acknowledge the importance of race and racism and its harms (roughly 900 districts that service about 35% of the U.S. student population) (See Pollock et al. (2022)). Furthermore, with an increased focus on racial inequity, long-standing discrepancies in discipline, surveillance and the punishment of Black and Brown students came under new scrutiny in districts across the nation (Annamma and Stovall 2020). In addition to schools adding an increased emphasis on race, racism and racial justice, Chris Malore reported on a 2020 OnePoll study that, “Aside from COVID-19, the biggest talking point for families is the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and race-related issues.” The survey found about seven in ten parents have talked to their children about BLM and racism in America. Two in three parents have also talked to their kids about police brutality (Melore 2020).

These efforts notwithstanding, what captured media attention and set new terms for public debate was the conservative backlash, and its narrative framed around a distortion of “Critical Race Theory” (CRT) and its incorporation in schools (a catch-all term for teaching about race, racism, diversity and inclusion) (Kaplan and Owings 2021). Anti-CRT campaigns mounted by some parents, conservative media outlets and state legislatures, stoked fears that schools are using BLM to “push an ideology through a curriculum” (Sitter 2021), and using CRT to racially divide the country and make white students feel bad about themselves. Such campaigns took cues from a Republican Texas state lawmaker’s proposal to ban a list of 850 books3 in schools and libraries that “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress because of their gender or race.” A report released by Pollock et al. (2022) “The Conflict Campaign” provides extensive research on anti-CRT efforts at the local district level, documenting bans, misrepresentations, distortions and threats, creating a hostile environment for discussions of race, racism and racial inequality and, more broadly, diversity and inclusion. In Florida and Texas, under the guise of “student religious freedoms,” an effort to ban discussion of Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) people or gender expansiveness in what are being dubbed “Don’t Say Gay” bills, have features which parallel the manufactured CRT conflict.

The U.S. was (and continues to be) not alone in these political debates. Similar anti-CRT discussions were taking place across Europe and in most postcolonial/decolonial contexts. For example, in the United Kingdom (U.K.) leaders threatened to deny funding for programs and museums if they removed problematic statues in Ireland. In England, the Department of Education prohibited schools from using “materials produced by anti-capitalist groups, or teaching “victim narratives that are harmful to British society” (Trilling 2020). BLM leaders were accused by U.K. parliamentarians of “having strayed beyond what should be a powerful yet simple and unifying message in opposition to the racism that still exists in our society, into cultural Marxism, the abolition of the nuclear family, defunding the police and overthrowing capitalism” (Trilling 2020). There is explicit mention of the continual existence of racism, yet programs, schools and other entities were prohibited from candidly addressing race and the manifestation of problematic histories.

3. The Research and Its Mixed-Methods Design

A team of researchers in the Urban Education Ph.D. program of the Graduate Center, City University of New York, gathered in the summer of 2020 to lift up parents’ perspectives which aretoo often neglected in school policy decision-making. Given all the uncertainty plaguing families with children in school, we designed a study to explore five main topics about parents’ views on: school access, operations and communication; curriculum and instruction (including remote and in-person instruction as well as teaching about race, racism and protest); family hardship and loss; and issues of educational equity, specifically racial equity. The team designed a two-stage study beginning with an on-line interactive web-based survey (n = 217) using Pol.is, an interactive survey tool, followed by individual and small-group interviews (n = 22). The survey was offered in English, Spanish and Chinese. Parents were recruited through a snowball technique of personal contacts, educational advocacy organizations, school sites, and social media, including Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. After completing the survey, parents had the option to participate in an interview to share their personal experiences and respond to survey data results.

3.1. Pol.is

Pol.is, an innovative, participatory and open-source survey tool gathers and analyses input from people “in their own words, enabled by advanced statistics and machine learning” as described by the designers http://pol.is/home (accessed on 8 May 2020). Participants respond (agree, disagree, or pass) to statements on the survey (i.e., “seed statements” entered by researchers). Participants can submit statements of their own, which are immediately added to the survey to which new participants respond. This feature makes it possible for people to change the direction of a conversation, adding topics that researchers may have missed. Our survey started with 25 statements and grew to 91 statements. These additional statements opened up a more robust and/or refined set of opinions that expanded the conversation. Comments submitted by participants can capture a majority (above 50%), or a supermajority (between 67% and 90%), or nearly everyone in the survey as having the same viewpoint.

3.2. Participant Characteristics

Pol.is surveys also include “meta-statements” to help discern certain characteristics of respondents. Our survey collected data on three main characteristics: household economic stability/precarity; school type (public, private, charter); and children’s age range (PreK-5th grade (ages 3–11) and 6th grade to 12th grade (ages 12–18).4 We learned that the participant pool was divided equally between parents with children of the two age groups; most had children attending public school. The vast majority of respondents were employed with access to health care, but some did report experiencing financial hardship because of COVID-19, which is discussed more in the next section.

3.3. Opinion Groups

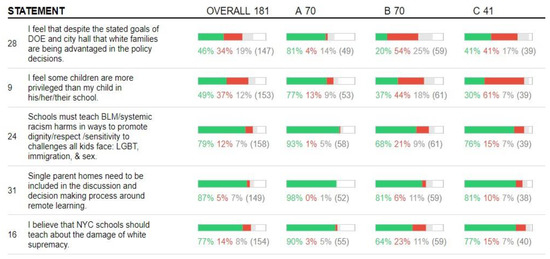

Pol.is uses a crowd sourcing mechanism and algorithm https://compdemocracy.org/algorithms/ (accessed on 8 May 2020) to find “opinion groups” and to surface what each opinion group has in common according to meta-statements. Our survey findings identified three opinion groups: Group A were those who were most concerned about racial inequality and its messaging in school; this group reported the most financial hardship (63%). Group B were those most in favor of in-person learning and schools remaining open; this group consisted of families with the youngest children. Within Group B, 92% agreed with the statement “Early learners need in-person school to learn to read and develop vital social skills. Remote learning is not developmentally appropriate”. Group C were most in favor of on-line learning (75% reported that remote learning should be a future option post COVID-19). This group consisted of families with children of mixed ages who attended more varied school types (but public school still predominated). Figure 1 below visually represents how Pol.is reports out survey findings, in this case illustrating how the three opinion groups responded to five different statements.

Figure 1.

Pol.is Survey Results.

Because our study aimed to make recommendations to policymakers and school leaders, we were most interested in the overall, aggregated survey data reporting the most agreed-upon statements as mandates for change (regardless of opinion groups). We reported these three mandates as recommendations for policymakers and school leaders to influence decision-making in the 2021 school year, also published on our website www.NYCparentSpeakOut.com (accessed on 9 September 2020).

4. Three Consensus Narratives: Mandates for Change

Acknowledging a broadening definition of what constitutes a narrative (Andrews et al. 2013; Riessman 2008; Phoenix 2020; Squire et al. 2014), we refer to a collection of the highest rated agreement statements as consensus narratives. We do this to capture the dynamic nature of participants’ responses, associations, and connections to the survey. Because participants added statements, we could track how they were framing these issues in their own words.

Parent engagement: Only 29% of respondents agreed with the seed statement, “I feel I was included in the planning for the re-opening of my child’s 2020–2021 school year.” Participants added statements that indicated feeling left out or ignored. For example, 87% agreed, “Single families need to be included in the discussion and decision-making around remote learning” and “Parents/guardians need to be a part of the conversation regarding school closures and alternatives relating to learning” (85%) and “Working families’ struggles are not being taken into account” (70%). “It is impossible for me to work full time and also assist my child with remote learning” (73%). There were also calls for more proactive Department of Education (DOE) solicitation of what “overworked caregivers need for respite” (87%). Parents wanted more input.

Social-emotional development and mental health needs: There was resounding agreement on mental health needs, a topic not originally included on the survey. A supermajority of parents agreed that “I feel there should be increased mental health supports (including non-traditional/group) for students due to social isolation from COVID” (91%). Whereas slightly more than half of respondents reported their children experiencing “significant learning loss” (a seed statement) many more parents expressed concern about their children’s social-emotional development and general well-being. For example, a parent added statement, “While my children have not suffered academically, they have lacked the engagement and socialization required for children to flourish” had a higher percentage of agreement (65%).

Addressing racism: The consensus narrative about racism and racial inequality was the most pronounced and elaborated through additional parent statements. 77% of participants agreed that “schools should teach about the damages of white supremacy” and that “NYC schools should teach about the “Black Lives Matter” movement” (both seed statements). More agreement developed around the parent added statement: “schools must teach BLM/systemic racism harms and promote dignity/respect/sensitivity to challenges all kids face” (79%). This addition broadened the emphasis on diversity and inclusion.

Parents indicated that discussions were taking place about civil unrest in their children’s schools; only 9% of parents said they had to “reached out to my child’s teacher after noticing the teacher was ignoring the issue”. Still, a third of parents expressed dissatisfaction with what was being covered: “My child’s teacher has not addressed race or civil rights in their teaching, not even around the Martin Luther King holiday” or their child’s teacher “was not implementing culturally responsive curriculum.” These, as well as other added statements, built out a desire for curricular change about how and what to teach children about racism.

Participants also added statements about equity—“Inequality in the school system is tied to wealth of the local neighborhood. It creates advantages for students in rich neighborhoods” (88%). Interestingly, less than half of respondents agreed with the seed statement, “some children are more privileged than my child in his/her/their school” (49%). Pointedly, a majority of participants agreed with the following sentiment and proposed solutions in a statement entered by one respondent: “NYC’s segregated system is disgusting. White parents, Stop hoarding high performing schools; use that privilege; fight for NYS equal funding” (64%).

Parents were evenly split about special education and the role of “gifted programs”5 in sustaining racial inequality. One parent statement pointed the finger at the NYC school system for fostering racial division: “NYC should stop pitting Asian Americans against African Americans and instead work to improve schools instead of dumbing them down” (51% agreed). Overall, there was a generative, if divided conversation about the sources and policy solutions to address racism. However, when it came to curricular demands about what children should be taught, there was more consensus than division.

This mandate for curricular change was striking, highlighting an intersection of the COVID-19 pandemic with its educational losses, anxieties and inequalities and the George Floyd/Black Lives Matter events that served as a collective reminder of systemic racism and what schools should do in response. These links become pronounced when analyzing individual parenting narratives to which we now turn. However, first, we offer a brief discussion of our approach to narrative theory and analysis as it relates specifically to interviews and social interactions.

5. Opening Up Counter-Storytelling, Multi-Positionality, and Race Talk

Narrative inquiry has been said to be especially important during times of rupture when lives are “interrupted” (Riessman 1993, 2008). Narrative theory assumes that speakers do more than describe particular facts about consequential events or experience. Speakers take their listeners inside, personal, and larger social worlds in order to make a point about themselves, their identities, relationships and values. Narrative analysis demands an attention to multi-positionality as interviewees shift from speaking to different audiences, including imagined audiences, who speakers might perceive as hostile, accepting and/or like-minded. In our interviews these shifts were important, as will become evident.

Counter-narratives are the “stories people tell and live [that] offer resistance, either implicitly or explicitly, to dominant cultural narratives” (Bamberg and Andrews 2004, p. 1). We have argued that the consensus narratives counteract the dominant discourse of political divisiveness about teaching about racism. Listening for counter-narratives in interviews is more dialogic and intersubjective, produced as part of how speakers position themselves in their social worlds and relationship to others, including the interviewer (Gee 2011). Paying attention to a speaker’s process of selection, connections, associations, sense of urgency, the use of first person, direct speech, and various grammatical devices are important for culling unspoken meanings about dynamics of power, subordination and resistance (Luttrell 2005). It is this selectivity that helps to highlight people’s multi-positionality, the moral points they wish to make, and how speakers take up, reject, and twist dominant discourses that are independent and apart from the events reported (Riessman 1993; White 1980; Polkinghorne 1988).

James Gee has emphasized the importance of paying attention to “identity building tools” that speakers use in their narrative meaning-making (Gee 2011, p. 119). We extend this by drawing on critical race theory and de/colonizing theory, including the insights of P.H. Collins (2002), Hall and Gilroy (2017), and Patricia Williams (1991). Speakers narrate their racial identification and affiliations in complex, contextual, fluid and strategic ways. As Patricia Williams (1991, p. 250), an early proponent of critical race theory wrote: “The complexity of role identification, the politics of sexuality, the inflections of professionalized discourse-all describe and impose boundary in our lives, even as they confound one another in unfolding spirals of confrontation, deflection, and dream”. It is within and outside of racialized boundaries that shape the way people narrate who they are and what they represent, while navigating the limitations imposed by the terms themselves.

Whiteness and “race-talk” studies also influenced our listening. Several scholars have written about how white speakers position themselves, as color-blind/color-mute, race-conscious, or race-avoidant (Frankenberg 1988; Pollock 2009), especially in conversations related to racism and its effects. Others have referred to dynamics of whiteness, white privilege and “white fragility” first coined by George Lipsitz (2006) in his classic book, Possessive Investment in Whiteness. His point is that the problem of white racism is not being white in and of itself. Rather, the problem is the historic investment in whiteness that has occurred as the result of the systems of slavery and segregation, as well as legacies of racialization at federal, state and local policies toward Native Americans, Mexicans, Asian Americans and all others groups designated by whites as “racially other,” which remains unchallenged.

Fighting against racism means more than having sympathy for someone else (i.e., those who are not white) but rather dismantling the systemic investment in whiteness. White fears and fragility about maintaining a societal and personal investment in whiteness have been popularized by Robin D’Angelo (2018) to refer to white people’s range of defensive reactions (guilt, anger, fear, silence, crying, etc.) when confronting the harms of racism. “Feeling white” (or the “emotionalities of whiteness”)—including shame, denial, sadness, dissonance, and discomfort are necessary to confront and overcome as a step for ensuring white accountability (Matias 2016). Meanwhile, white fragility is not only a problem for white people. It also affects “racially othered” people who must contend with the emotionalities of whiteness, which adds extra emotional labor to the experience of navigating white-dominant spaces and relationships with white people.

One striking feature of all the interviews was that in one way or another, all the interviewees positioned themselves as more “fortunate” or “privileged” than others they knew weathering the COVID-19 storm, whether related to loss, financial hardship, or limited resources (including inadequate access to technology and well-resourced schools). Even those who spoke about the death of family members and provided details of hardship couched their stories in terms of “it could have been worse”. The interviewees spoke as if they were in dialogue with an overarching awareness that COVID-19 served as a window into deepening social inequalities. These interviewees made sure to acknowledge their relative privilege within a larger story of COVID-19’s ravage and rupture.

6. Three Parenting Narrative Cases

We selected the following three parenting narrative cases because they exemplify inter-related themes about childhood innocence, navigating white spaces and norms, and racial accountability dynamics that resonated, albeit in different ways, across the interviews and in our Pol.is survey data.

Our interpretations are influenced by critical race and whiteness studies briefly explored above. We invite readers to enter a dialogue with the narratives, raising questions and making interpretations about how these parents are grappling with their shared goals and desires for schools to teach for and about racial justice. All interviewee names are pseudonyms.

6.1. Creating and Protecting Black Childhood Innocence: Malcolm

“It was a sobering moment for me because I realized, more so when that happened (the murder of George Floyd), that my kids are paying more attention than I even realized. I started like I was, you know, everybody was a really high emotional time and I kind of started going to like some of the protests and my family was concerned because you know that there are legal ramifications for me being on parole. I just felt like I had to go and next day after like I kind of argued with my family about it. I woke up in the morning and my younger daughter was like, ‘oh, I have to show you something.’ And she had like created this digital art thing on some platform. And it was a BLM centered thing and it was you know Black Lives Matter. And it was like a conversation that I hadn’t even had with her. And it just kind of like reinforced to me that I was doing the right thing and then that opened the door for me to start talking to my kids and I spoke to my older child about it and she expressed how she’s experienced racism before. So yeah, it was definitely an interesting time but I think it’s always been. For the most part I try to understand the two I guess because maybe schools are scared of being highly politicized. But for the most part it seems that it has been business as usual. And I think that even if it wasn’t something that was brought out in the classroom there should have been some kind of individual outreach maybe done for the kids.”

Malcolm was explicit in identifying the murder of George Floyd as a transformative event for himself. He opened his account setting an emotional and temporal stage to discuss his children’s racial awareness. He viewed the event as new, but also part of an enduring past. The event propelled him into action, participating in BLM protests and being engaged by his kids about racism. He quickly brings the interviewer into his personal circumstances of being on parole that he discussed with ease with the African American female interviewer (we wondered whether he would have done so with a white interviewer). Whereas the event “opened the door” for him to talk with his kids about racism, he is unsure about the role of schools in addressing racism and racial violence. Even if schools do not actively teach about racism in the classroom, he believes schools are responsible for attending to individual children’s feelings and well-being through “some kind of individual outreach.”

Malcolm expresses surprise that his young daughter was the initiator of a discussion about racism, rather than the other way around. Contrary to the widely reported family conversation about race that Black parents hold with their children, known as “the talk” (Anderson et al. 2022), Malcolm expresses conflict, repeatedly referring to what he “hates” about the realities of Black parenting:

“I’m only conflicted by it just because it’s I hate the thought of politicizing our children, but it’s a reality. Like, it is a reality. Growing up and realizing that I was taught a different history. For me it was mind boggling. I was like, ‘What do you mean Columbus isn’t a hero?’ Just thinking back on it, I kind of wish I would have been taught, you know, actual history, but just as a parent, as a protector, like I hate the idea that my children have to see all these troubles. Like I hate that they realized that BLM is a thing. I mean, younger ones, nine years old, I don’t like the world that my children are growing up in, and like I hate it. And just as a parent, as a protector, I hate that I would have to explain to them like this is what it is. And just how it will create riffs within people and dynamics and things like that. But I don’t think that’s an excuse to not do it. I’m just yeah I’m completely torn over it. But obviously, it’s the right thing. Ideally, it’s the right thing.”

We can hear Malcolm invoking the notion of childhood innocence and adult protection, wishing that his children could be shielded from uncomfortable truths about the past and “seeing all these troubles.” Malcolm specifies “the younger ones, nine years old” and laments that the world his children are growing up in puts him in a bind. Interestingly, especially in terms of the contested national debate about teaching the history of the U.S. and its systemic racism, racial violence, and settler colonialism, Malcolm underscores his wish that he had been taught “actual history” in his youth, but as a parent it gives him pause. He acknowledges the limitations of his own childhood mis-education (which boggles his mind, suggesting his shift of perspective) but also worries that learning actual or truthful history can be disturbing for his children.

Malcolm’s internal conflict and the way he registers his strong dislike of having to do the “right thing” expands on and complicates the survey findings in favor of teaching about BLM and white supremacy. For him, it is also a point of anguish evoking powerful feelings about wanting to insulate his Black children from the harsh realities of a racist world—to allow them childhood innocence.

At the same time, Malcolm registers surprise about his six-year-old son’s political savviness:

“My son, the things you hear him say about Trump, you would think you’re talking to a grown adult to formulate an opinion and he’ll back it up. He will defend his stance as to why Trump is not good. He said, ‘Trump is not for the people. He hates Spanish and Black people. He doesn’t like us. And he’s like, he’s not a good president, he’s not a good man.’ The first time he ever expressed it to me he was six years old and it was in a visiting room in Sing Sing. And I was blown away. He’s definitely not shy about expressing himself. He has no filter yet. I don’t even remember how we got into that when I was just like, ‘I don’t think anybody else comes up here talks politics.’ But it was definitely eye opening. Definitely cool to hear him have his own opinion and be able to articulate it.”

Malcolm’s narrative takes up and unsettles the canonical narrative of the unknowing, innocent child, and the all-knowing and developed adult, including assumptions about what children are capable of understanding and expressing about power, politics and racism. Malcolm seems in awe of his young son’s ability to articulate and defend his opinions. His son challenges what is typically discussed during family prison visits by talking politics. Malcolm’s narrative about his son seems filled with pride as well as hope.6 Malcolm’s eyes are opened, suggesting that his horizons are widened for his son’s future.

Listening to Malcom’s narrative complicates over simplistic notions of “childhood innocence” and what children can or should be exposed to. Childhood researchers and educators Bentley and Reppucci (2013) quote Gloria Boutte, known for her expertise on equity pedagogies, “While we are waiting for young children to be developmentally ready to consider these (complex and race-related) issues, they are already developing values and beliefs about them.”. Most important to note is that childhood innocence has a racialized history. In a society with a legacy of enslavement and institutional racism, Black children have not been granted the same protected status as “children” as have their white counterparts. Research indicates that people of all ages see Black children as older than they are, more adultlike, and more responsible for their actions than their white peers (Goff et al. 2014). Malcolm’s narrative begs the question: How can Black childhood innocence be created and protected while at the same time preparing them to thrive, survive, and actively struggle for racial justice? His narrative is also instructive for considering the unequal, racialized dynamics of whose childhood innocence gets acknowledged and protected.

6.2. Navigating White Space and Norms: Jamila

Jamila’s account is given in response to the interviewer’s question: “There was a question that came up in the survey that most parents agreed that their children’s school should teach children to be anti-racist. Can you tell me your thoughts on this?”

Jamila’s sequencing, selection, and cautious narration illustrates just how pointedly she is navigating the white space of schooling and relationships with school officials:

“I mean, it depends because it depends on, um, who’s teaching the children to be anti-racist sure. Um, I think that in, um, I think that for the most part in order, if you haven’t really lived in that type of, um, environment or know people, it’s really hard to understand to some what can be said, it can be considered, um, discrimination. Um, and I think it’s real easy for teachers and everybody else to fall into kind of just doing things that a little bit insensitive.There was a time two years ago when the teacher mentioned something about the way my daughter’s hair looked. At the time she was starting the dreading process, getting locks, um, relaxed. She had her hair, she was always changing it. So she had like a really messy bun on the top of her head. And the teacher said to her, um, ‘what is that on your head?’ And so she thought there was something on her head and she said, you know, she was like, ‘I don’t know.’ And the teacher handed her a mirror to look at it. And she was like, ‘Um, nothing is, you know, my hair is in the bun.’ The teacher said, ‘Oh, I don’t, I don’t think that that’s really a bun. You know, what I have on my head is a bun.’You know, so it was an interesting conversation afterward with the teacher and the principal. Um, but I don’t think that she really understood how that can make somebody feel, um, you know. When you’re talking about her, especially to a Black person, um, that can be pretty, you know, touchy, you know, for a young, Black person growing up, you know. We, they think about the hair a lot and, you know, try to deal with it and managing it and, you know, love it.I think that for the most part, if you haven’t really lived in that type of, um, environment or know people, it’s really hard to understand some of what can be said. It can be considered, um, discrimination. Um, and I think it’s real easy for teachers and everybody else to fall into kind of just doing things that are a little bit insensitive.”

Jamila conveys the centrality and significance of her daughter’s hair event by using direct reported speech, establishing the behavior and characteristics of the main characters: a teacher (who we can infer is white) and her Black daughter. Jamila positions herself as part of “we/they” who “think about hair a lot.” She is taking her white interviewer/listener, ever so gently, into the life experiences (including microaggressions) of Black girlhood/womanhood that are widely circulating (Gadson and Lewis 2022). Jamila considers the teacher unaware and is generous in her racial critique by taking account that if “you” (meaning White people and probably the interviewer) have not lived as a Black person in a white racist world (which Jamila calls “that type of environment”) or is not familiar with Black experience, then it can be “real easy” for (white) teachers and everybody else to “fall into” (as if accidentally) saying something “insensitive” (i.e., racist). Thinking about the identity building tools that Jamila is using to tell her story, we could say that she is making an effort to build a bridge across racial differences without pointing fingers or creating discomfort for this white listener. In contemporary discourse about tackling racism, Jamila’s approach is suggestive of the effects of “white fragility” that forces people of color to attend to how White people might react to issues of racism or discrimination. Jamila’s style of narration conveys the extra conversational and emotional work necessary to consider the comfort of a white audience. Jamila initiates a conversation with the school officials, which she describes as “interesting”—a non-committal phrase that covers over her own reactions. She also gives the benefit of doubt to white people and avoids sounding accusatory.

Jamila’s storytelling leaves out many details of what happened. How did her daughter report this incident to her mother? What were her daughter’s feelings about what the teacher had said? How did Jamila respond to her daughter’s feelings? Jamila does not convey her emotions about not being able to protect her child against racial harm or her innocence about a racist world. Instead, Jamila’s story is told with the emotionalities of whiteness in mind with a moral instruction about the need to educate a white school staff without causing a negative or discomforting reaction. By contrast, Malcolm’s story is told with a Black audience in mind; the moral point being the harmful conditions and pain associated with raising Black children in a racist society that does not acknowledge and protect their innocence and well-being.

Jamila’s account can also be read as a counter-narrative about white standards of beauty, emphasizing how Black women learn how to “deal with, manage” and most importantly “love” their hair. Her story calls for two racial harms to be repaired. First is that teachers and schools should refuse to uphold white standards (it is the white teacher’s bun that sets the standard). And second, schools and teachers must message love to Black children about themselves and their hair. In both cases, Jamila is concerned that the damages of whiteness and whether (white) teachers are up to the task of teaching anti-racism. She believes there is a need to be “teaching around it” and “caution” about “who we’re putting into place” to ensure that the right messages are relayed. Jamila’s narrative suggests some skepticism of the consensus call for schools to teach about racism and racial justice: “It depends on who’s teaching.”

6.3. Racial Accountability Dynamics: Eliana

Eliana tells her interviewer that she agreed to be interviewed because she is concerned about the issues. In doing so, she positions herself in multiple ways: as an educator, a mother of Black children, and the wife of a Black man who does not “trust the system as it is”. She identifies herself as an insider of the school system and opens the conversation up through dialogue with her husband as if he were speaking as well:

“I’m concerned of course, as an educator, as to like academics in general, but that’s more so because my children are Black and I, they’re, I perceive that they are already getting a less-than education. And so my concern is just that (referring to the pandemic and remote learning) would intensify in this environment. Not because I feel like they are missing out on learning everything they need to know in this year. Does that make sense? …. And my husband would say if he was here, that his concern has always been, not necessarily what the school teaches our children, because he believes that the majority of the learning (about racism) our kids will encounter will happen at home. He is a Black man and he doesn’t necessarily trust the system as it is, and I am in agreement. And so the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated what was already there.”

When asked to elaborate and says:

“Our resources as the city tend to go to those who already have the most resources, um, and those who need it more tend to not get it and that tends to be our Black and Brown children who make up the majority of DOE students. Without a doubt, I think that even before COVID-19 white families were, were profiting and, and, and being the recipient of more resources in the DOE and the city, I mean, it’s all tied together.”

Eliana talks about the COVID-19 pandemic “exacerbating” racial educational disparities already in place in New York City. She also makes a distinction between what her children are learning “academically” and what they learn about racism, which her husband believes will happen at home (and she agrees).

Eliana presents the racial impact of the pandemic as systemic (all tied together) more than individual. She uses “our children” as an identity and relationship builder, bringing her audience (and the white interviewer), into an embrace of Black and Brown children as the majority. Situating herself as an experienced teacher, Eliana makes a distinction between curriculum and pedagogy (“what you are doing with materials”) and speaks directly to teachers about what “you” need to be doing.

“It’s about teacher mindset. So like, as a teacher, I was a teacher for 16 years. I think it’s great to have anti-racist curriculum and materials, but again, if teachers aren’t believing it, if teachers aren’t seeing their students for who they are, I don’t know that that’s enough. And I can’t even believe that that’s a question that we have to ponder in 2021, but apparently we do.”

Eliana’s critique gets stronger as she speaks about “catching herself” in an actual dialogue with (presumably white) teachers, as if bringing them directly into the room:

“Listen, I have to catch myself. Right. Like I think people become exhausted. And so it’s really much easier to just say like, ‘You’re a racist, what you just said was racist. Like what you’re doing is racist.’ And move on and just say like, ‘That’s it, you need to fix that, whatever, I just called you that, and now you need to fix that.’ I think it’s way harder to consider somebody on a continuum of, of anti-racist or not anti-racist and think about what are the things you’re doing to get there… Because when we talk about anti-racism right, that can be very individualized. Like you, are you, you know, or am I, are we, where are we on that (continuum)?”

Eliana’s dialogic storytelling positions her as an expert, someone who wants to broker change. She is not explicit about her whiteness or white privilege. She acknowledges two different forms of intervention: the first is binary—you either are or are not a racist. While this approach might offer cognitive closure,7 it suggests that anti-racist thinking is fixed, not a learning process. The second form of intervention on the continuum is harder, it is more open, more evolving where individuals can meet each other at the same or different place.

Shifting between “you”/“I”/“we,” Eliana makes it hard to pinpoint her own positionality and personal experience as a white woman within the binary or along the continuum of being anti-racist. Unlike Malcolm and Jamila, Eliana shares no personal narrative of an everyday encounter she has had with a student, parent, teacher, principal, or on behalf of her own children. Instead, she addresses the issue of white fragility and emotionalities:

“I’m really tired of waiting for people to feel comfortable. I mean, we’ve been doing anti-bias training. This is not something new and I don’t know that they’ve been so effective. I mean, I participated in an anti-biased training and walked away like this, this wasn’t good… I just am really tired of thinking about how white people would react in that situation. And I’m really tired of coddling and catering to white people’s reactions, uh, because generations have been affected by that coddling.”

It is striking to compare and contrast Jamila’s efforts to not offend or discomfort the white school officials (and perhaps her white interviewer) with Eliana’s reaction, which is itself a form of privilege for Eliana to not have to worry about how she might discomfort her white colleagues. Eliana considers tending to white emotionalities (i.e., needing to be coddled and catered to) as being at the expense of generations of children.

Eliana speaks through the language of “accountability” to frame her desires for change:

“And so I’m hoping that what’s next after this anti-racist curriculum that we really start holding educators accountable for how they see our children, because that’s really at the crux of how they’re teaching our children, right? Like if they saw the children in front of them, as brilliant and with endless potential and coming with strengths and their families coming with strengths, then they would teach in that way. And so something has to shift, but I’m not willing to go backwards to get it at them. … Like how are you teaching? How is your teaching really harmful to the Black and Brown children in front of you? Did you use all white authors for this topic? Do you affirm who your children are when you’re talking to them, do you say their name correctly? Like all of these little things, right that really show beyond anti-racist curriculum, like just a CRE kind of vision,8cultural, responsive education vision, but like, why aren’t we holding people accountable in that lens?”

Eliana uses asset-based educational language, characterizing Black and Brown children as “brilliant” with “endless potential”, coming to school with personal and family “strengths” (Pollack 2012). Asset-based (rather than deficit-based) teaching is itself a counter-narrative that Eliana tells in a storied and dialogic way, bringing (white) teachers into the room instructing them to provide affirmation, say a child’s name correctly, make sure students are exposed to more than white authors, to name a few. There is urgency in Eliana’s sense that “something has to shift” and a refusal to “go backwards.” Left unsaid is whose responsibility it is, and begs the question of how to shift the dynamics of racial accountability.

7. Linked Narratives of Resistance

All three narratives suggest that in the white space of schooling, parents are differently positioned to demand change. There are multiple layers and intersections of concerns that parents bring to consensus and alliances. Eliana can reject the imperative of comforting white people and their feelings in a way that Jamila and Martin do not or cannot. Malcolm insists on recognizing and wanting to ensure a more protected childhood status, if not innocence, for his Black children. Jamila expects schools to do more than refuse damaging white norms and standards; she wants schools to teach her children to love themselves. As a school insider, Eliana is the least trusting or perhaps least hopeful that schools (particularly white teachers) can change, and yet, she has not given up.

These three parenting narratives are linked by the outlines of their resistance. They suggest the importance of racial, inter-generational, and multi-positional dialogue; how personal experiences are political and thus of public concern; and that embedded in change is a revised reflection on the past, present, and future horizons. The narratives highlight parental alarm, distress, and frustration, as well as hopes for changing the way Black children are educated.

8. Conclusions: How, Not If

Our paper demonstrates the usefulness of narrative inquiry and identifies education as a key site of resistance, focusing on the impacts of COVID-19, and racial inequalities on children’s schooling. The mixed method study, with its interactive survey and in-depth interviews, afford fresh insights into parents’ priorities during anxious and uncertain times. Parents are allied about demanding change: they want more input in school decision-making and they value their children’s social emotional development and mental-health, not as “add-ons” to school’s mission, but as a centerpiece. Given the CRT backlash and the manufactured political conflict in the U.S. about race and education, we have identified more consensus than division among parents. There is a counter-narrative of resistance that we lift up, amplify, and complicate. We have heard parents turning to and away from schools as places they trust to equip their Black children to live in a racist society. Still, within imperfect classrooms across the U.S., parents want to protect Black children’s innocence while also preparing them to survive and struggle in hostile environments. Parents want teachers (especially white teachers) to “see” their children for who they are, for their full potential, and abilities to thrive. Parents want a more comprehensive historical narrative, despite its emotional challenges. The consensus and parenting narratives highlight the layers and complexities for parents as they pursue their desires for their children in schools. Careful listening to how parents tell their stories of everyday events and challenges increase the capacity for building alliances and consensus, and potentially open up new forms of racial accountability. The task now is to create conditions that can ally children, parents, teachers, communities, schools, educational and social policies. This political imperative is an open question about how, not if.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. and M.E.; methodology, W.L.; software, J.J.; validation, W.L., M.E. and J.J.; formal analysis, W.L and M.E.; investigation, W.L., M.E. and J.J.; resources, W.L.; data curation, W.L. and M.E.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L.; writing—review and editing, W.L., M.E. and J.J.; visualization, J.J.; supervision, W.L.; project administration, W.L.; funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was was funded by a Professional Staff Council-City University New York (PSC-CUNY) award 64708-00-52.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York, (IRB File #2020-0769, 11/04/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by IRB Review Board at the Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York (IRB File #2020-0076).

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publically available due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their insightful and constructive feedback. We also want to thank the entire research team, including David Rosas, Whitney Hollins, Nga Than, Kelly Brady, and William Orellana.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For example, a parent survey conducted by Global Strategy Group and The Education Trust–New York found that NYC parents were the most racially divided across the state. 84% of white public-school parents in NYC said their child would attend school in-person, if possible, compared to 63% of Latinx parents and only 34% of Black parents. |

| 2 | As part of New York State’s Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Plan, equity and inclusion is an integral part of every facet of the work. The Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Education (CR-SE) Framework created by the New York State Education Department is a guideline that is recommended at the state, district, and school-level with four pillars to create: welcoming and affirming environments; inclusive curriculum and assessment; high expectations and rigorous instruction; and ongoing professional learning and support. The NYSED CRSE Framework is referenced here: http://www.nysed.gov/common/nysed/files/programs/crs/culturally-responsive-sustaining-education-framework.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021). |

| 3 | It should be noted that books written by authors of color are disproportionately represented on banned lists (Will 2021). |

| 4 | A limitation of Pol.is is discerning interesting and important demographic data of the participant pool, such as gender, class, racial, ethnic, or linguistic identifers, which this survey did not explicitly include. |

| 5 | Gifted & Talented programs offer accelerated instruction to eligible elementary school students in New York City. Students apply and take an assessment to become a part of the specialized program which critics say results in social inequity. |

| 6 | We thank one of the reviewers for drawing attention to expanding the metaphor of widened horizons. |

| 7 | Again, we thank one of the reviewers for naming this distinction. |

| 8 | CRE (culturally responsive education) is a U.S. educational discourse that promotes an approach to schooling centered on students’ knowledge, cultural backgrounds and everyday experiences that must three criteria: an ability to develop students academically, a willingness to nurture and support cultural competence, and the development of a sociopolitical or critical consciousness” (Ladson-Billings 1995, p. 483). |

References

- Anderson, Leslie A., Margaret O’Brien Caughy, and Margaret T. Owen. 2022. “The Talk” and parenting while Black in America: Centering race, resistance, and refuge. Journal of Black Psychology 48: 475–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Molly, Corinne Squire, and Maria Tamboukou. 2013. Narrative research. Qualitative Research Practice 97: 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Annamma, Subina, and David Stovall. 2020. Do# BlackLivesMatter in schools? Why the answer is “no”. The Washington Post, July 14. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, Michael, and Molly Andrews, eds. 2004. Considering Counter-Narratives: Narrating, Resisting, Making Sense. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bambra, Clare, Ryan Riordan, John Ford, and Fiona Matthews. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 74: 964–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, Dana, and Anthony Reppucci. 2013. “I Think They All Felt Distressed!” Talking About Complex Issues in Early Childhood. Childhood Education 89: 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Tina L., and Alison M. Conca-Cheng. 2020. The pandemics of racism and COVID-19: Danger and opportunity. Pediatrics 146: e2020024836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2002. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Robin. 2018. White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg, Ruth Alice Emma. 1988. White Women, Race Matters: The Social Construction of Whiteness. Santa Cruz: University of California, Santa Cruz. [Google Scholar]

- Gadson, Cecile A., and Jioni A. Lewis. 2022. Devalued, overdisciplined, and stereotyped: An exploration of gendered racial microaggressions among Black adolescent girls. Journal of Counseling Psychology 69: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Grace, and Linna Sai. 2021. Opposing the toxic apartheid: The painted veil of the COVID-19 pandemic, race and racism. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 183–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, James Paul. 2011. How to Do Discourse Analysis: A Toolkit. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, Phillip Atiba, Matthew Christian Jackson, Brooke Allison Lewis Di Leone, Carmen Marie Culotta, and Natalie Ann Di Tomasso. 2014. The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106: 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, Stuart, and Paul Gilroy. 2017. Uncut Funk: A Contemplative Dialogue. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Leslie S., and William A. Owings. 2021. Countering the furor around critical race theory. NASSP Bulletin 105: 200–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, Gloria. 1995. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal 32: 465–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, George. 2006. The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell, Wendy. 2005. “Good enough” methods for life-story analysis. In Finding Culture in Talk. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 243–68. [Google Scholar]

- Matias, Cheryl E. 2016. Feeling white: Whiteness, emotionality, and education. In Feeling White. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Melore, Chris. 2020. Most American Parents Are Talking about Politics, Racism, Civil Unrest with Their Children, 2020. July 21. Available online: https://www.studyfinds.org/parents-talking-politics-racism-civil-unrest-children/ (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Phoenix, Ann. 2020. Children’s Psychosocial Narratives in “Found Childhoods”. Narrative Works: Issues, Investigations, & Interventions 10: 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1988. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, Terry M. 2012. The miseducation of a beginning teacher: One educator’s critical reflections on the functions and power of deficit narratives. Multicultural Perspectives 14: 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, Mica JohnRogers, Alexander Kwako, Andrew Matschiner, Reed Kendall, Cisely Bingener, Erika Reece, Benjamin Kennedy, and Jaleel Howard. 2022. The conflict campaign: Exploring local experiences of the campaign to ban “critical race theory” in public K–12 education in the US, 2020–2021. Report for the Institute for Democracy, UCLA IDEA. Available online: https://idea.gseis.ucla.edu/publications/the-conflict-campaign/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Pollock, Mica. 2009. Colormute. In Colormute. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, Catherine Kohler. 1993. Narrative Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Riessman, Catherine Kohler. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sitter, Phillip. 2021. Ames equity director speaks about goals, some criticisms of Black Lives Matter at School week. Ames Tribune. January 30. Available online: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1DERDkM3J3XpzGqYvZqkyEy0sqhUnoYWI (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Squire, Corinne, Molly Andrews, and Mark Davis. 2014. What Is Narrative Research? London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Trilling, Daniel. 2020. Why is the UK government suddenly targeting ‘critical race theory’? The Guardian 23: 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- White, Hayden. 1980. The value of narrativity in the representation of reality. Critical Inquiry 7: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will, Madeline. 2021. Calls to ban books by black authors are increasing amid critical race theory debates. Education Week. February 27. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/calls-to-ban-books-by-black-authors-are-increasing-amid-critical-race-theory-debates/2021/09 (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Williams, Patricia J. 1991. The Alchemy of Race and Rights. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Hongqiang. 2020. Countering COVID-19-related anti-Chinese racism with translanguaged swearing on social media. Multilingua 39: 607–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).