Abstract

The article seeks to answer the question about the perceptions that teachers have in training and in practice on the didactics of the social sciences in Colombia. To this end, a method with an interpretative approach with a mixed design is used to integrate the quantitative and qualitative analysis of the data produced on these perceptions in the context of basic and secondary education. The results present from the perceptions of teachers some correlations between the didactics they claim to use and the way in which it is expressed in their pedagogical practice. The conclusions contribute to the design, implementation, and evaluation of educational policies in education, especially those aimed at improving the teaching and learning processes of the social sciences at different educational levels.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the perceptions of Colombian teachers of social sciences in primary and secondary education who are in training and in practice. The study contributes to strengthening the literature on social science didactics that has been growing in the last decades, especially in the lines of geographical (Castellar et al. 2021; Delgado 2003; Rodríguez et al. 2019) and historical thinking skills (Palacios 2021; Palacios et al. 2020). This study recognizes the relevance and importance of teachers’ perceptions for the design, implementation, and evaluation of educational policies in education, especially those policies aimed at improving teaching and learning processes in primary and secondary education. The analysis of the perceptions of social science teachers can make visible the clarity they have regarding why and for what purpose they must teach the discipline and the role of the activity they carry out in the classroom daily. The results of the article highlight the importance of collecting the perceptions of future teachers and those who are already practicing since we agree with the approaches of Gómez et al. (2018) and Martínez et al. (2006) who emphasize that inquiring into the perceptions of history teachers in training and practice can give us a perspective of what needs to be changed in the didactics of the discipline. The analysis of such perceptions also contributes to reflecting on the visions that teachers have about the influence of the weight of the disciplinary code of Geography and History and the numerous continuities that preside over the school day-to-day (Parra and Morote 2020; Parra et al. 2021).

1.1. The Perceptions of Social Science Teachers

The literature indicates that studies on perceptions are necessary because they analyze the meanings that people have constructed and the ways in which these meanings guide their attitudes and behaviors in everyday life (Schutz 1962; San Fabián 1988). If we take into account that studies on the quality of education (OECD 2009; Darling-Hammond 2017; World Bank 2017) have proposed that a fundamental axis for achieving this quality is teacher training, it is relevant to know the perceptions that both trainees and practicing teachers have about their pedagogical practice and the field of knowledge they teach (Palacios 2018). Research by (Rudduck and McIntyre 2007; Portela et al. 2014; Rudduck and Flutter 2000) consider students and teachers valuable witnesses of the teaching and learning processes that take shape in their educational institutions. Therefore, inquiring into their perceptions of school life and teaching and learning processes makes their knowledge and experience visible in order to analyze, reflect, understand, and make judgements about the education they receive and deliver, contributing to its improvement.

Research on perceptions is a priority in educational research in the social sciences (Evans 1993; Giménez et al. 2007; Pagès 1994; Thornton 1991) due to the central role historically played by recognizing what the actors involved in educational processes think and what they mean. According to (Rudduck 2006, 2007), the perceptions of teachers, students, and their families have valuable contributions and relevant information to share about what the school is and what it can become. For (San Fabián 1988), in the fields of psychology of learning and interpersonal relations, numerous studies have been developed on students’ and teachers’ perceptions of their schools. These studies are based on the theories of attribution, social climate, and motivation. (San Fabián 1988; Palacios 2018) highlight that those studies on the perception of subjects in general, and of educational actors in particular, have focused on describing and analyzing their behaviors, actions, expectations, pedagogical practices, classroom climate, teacher demands, and the relationship between the school and the state.

For Sánchez et al. (2020) and Palacios (2021), in the field of social sciences didactics, studies focused on the diagnosis of the forms of teaching in this field constitute a necessary line of research that is complemented by studies on learning outcomes, critical analysis of public policy, and school organization. According to these authors, the importance of such studies lies in the need to know how disciplines such as history, geography, and art history are taught in order to detect shortcomings and improve teacher training. In the same vein, (Zou 2020; Palacios and Reedy 2022; Nikolopoulou 2020); state that teachers’ perceptions of the implementation of these didactic innovations and their teaching practice are the basis of obtaining a better understanding of their interests, demands, and needs. Consequently, with the previous positions, (Muñoz 2006) points out that the need to be concerned about teachers’ conception of their profession is a fundamental task in all fields of knowledge. This is especially relevant in the field of social sciences, since the study of history and its teaching are closely related to the preparation of future citizens and, therefore, coexistence within society (Muñoz 2006).

The analysis of the perceptions of social science teachers can reveal the clarity they have regarding why and for what purpose they have to teach the discipline and the role of the activity they carry out on a daily basis (Pérez 2010; Díaz et al. 2015; Imbernón 2012). This reflection is necessary because the history and social sciences teacher lives in a continuous process of interaction with the society of which he or she is a part. Social science teachers’ perceptions of what, why, and how to teach are a reflection of their ethical and political commitment to their teaching work (Palacios 2021; Díaz et al. 2015; Sánchez et al. 2020). This perception is also related to the way in which their sense of belonging to a collective is made up of a set of values, beliefs, and socio-cultural norms that make up a collective imaginary that encompasses the most diverse levels of culture (Pérez 2010; Díaz et al. 2015).

Additionally, research by (Gómez et al. 2018; Lévesque and Zanazanian 2015; Martínez et al. 2006) concluded that inquiring into the perception of history teachers in training and practice can give us a perspective on what needs to be changed. (Parra and Morote 2020; Parra et al. 2021) also conclude that consulting future teachers reveals the weight of the disciplinary code of Geography and History and the numerous continuities that preside over day-to-day school life. The students (future teachers) are able to criticize the methodologies that characterized their classes, but they take into account several factors when evaluating their memories, among them the role of the teacher. Coinciding with the previous conclusion, a study by (Araya and De Sousa 2018) in which practicing geography teachers were consulted about their methodologies showed that strategies are guided by social conceptions and mediated by interactions between students and teachers. However, (Araya and De Sousa 2018) did not visualize any intentional long-term process for the development of spatial reasoning modalities that allow for the development of higher skills of geographic thinking. This long-term social and historical process transcends the objectives of this paper.

1.2. Trends in Social Science Didactics

The reflection on specific didactics began in the 1960s, dedicated to the analysis of the teaching and learning of particular contents and their relationship with teacher training. The didactics of a discipline are then considered a science that studies areas of particular knowledge, differentiated phenomena in teaching, and significant conditions of transmission of culture and the transmission of knowledge to an apprentice (Pagès 1994). Thus, their development depends on academic decisions that give priority to the pedagogical process on social, temporal, and spatial phenomena, whose teaching and learning are nourished by the conceptual repertoires of history, geography, politics, anthropology, economy, and sociology, among others, to provide, as (Benejam 2004) proposes, a theoretical-practical knowledge in didactics to respond to what, how, for what, to whom, and why to teach social sciences.

The purpose of the didactics of social sciences is located, according to (Quiroz and Díaz 2011), in the analysis of reality and teaching practices of history, geography, and other social sciences, which together with its contents, purposes, and methods allow one to identify and explain relevant social problems to act, transform, and improve their learning. Therefore, didactics is valid in the same field of teaching as, from the perspective of (Bronckart 1989), it has its center in the classroom where actions are produced that contribute to increasing didactic knowledge, concerned with the transformation of practice and its theorization; for which the recognition of the teaching nature of the social sciences identifies objectives and purposes compatible with the state of their teaching. For this, it is important to investigate ideas, theories, and purposes contained in the curriculum and the criteria used by teachers to implement them in practice.

Although the didactics of the social sciences are in a state of construction and little academic production has not achieved a significant level of maturity (Prats 2002; Aguilera and González 2009), it is advanced in discussions on conceptual problems, methodologically and epistemologically, that identify it. In this sense, its current conception differs (Quiroz and Díaz 2011) from specific didactics such as those of history or geography, when considering the didactics of the social sciences as an area of university knowledge supported by the teaching and learning of social knowledge in direct relation to the school context and the curriculum developed therein. Likewise, it recognizes the resolution of problems of social reality is interdisciplinary and involves knowledge linked to civic education.

The foregoing allows us to characterize this academic field as a place of disciplinary interactions that share objectives and methods with related disciplinary areas and as an area crossed by multiple dimensions that require research efforts to configure theoretical references, pedagogical and didactic, that clarify, as (Prats 1999) affirms, not only the contents and learning of historical-social knowledge but that establishes a relevant theoretical body on educational research. This is related to the approach of the social sciences in its epistemic diversity on social reality, distancing itself from a monodisciplinary view (Gutiérrez and Trujillo 2008), in which the problems cease to be specific to each social science, understood by each social science, or understood by each of its knowledge in complementarity with others.

For its part, the definitions of the nature of didactic knowledge consider three interpretations collected by (Aisenberg 1998) that can be extended to the didactics of the social sciences: Didactics as a non-scientific practical theory, specific didactics as scientific disciplines, and didactics as a set of reflections based on different sciences, without actually constituting itself as a scientific discipline. The first is considered part of a theory of education (Camilloni 1994); the second is based on empirical research on teaching as its own object, within the framework of a triallectic relationship between teachers, students, and contents of a specific field of knowledge (Chevallard 1997); and in the third, didactics does not become a scientific discipline because it does not have specific research or its own concepts (Coll 1996; Lerner 1996; Lenzi 1998).

The above shows the path of formalization that is developing in the didactics of social sciences with discussions about the nature of their teaching and learning, as well as the definition of the main problems and conceptual nuclei proper to work. This is a difficult but exciting task for the academic communities interested in the didactic knowledge of the social knowledge that is taught and learned, as well as for the teacher training in which these specific didactics require defining their scope of action, objectives, and methods, and developing the theoretical and practical knowledge necessary for social and civic education.

The relationship of didactics with the curriculum in social sciences is fundamental and derives another trend in its understanding presented by (Pagès 1994), in which the curriculum analysis prescribed or tacit, institutionalized or practical, and visible or hidden allows progress in teacher training in the knowledge they teach. In this sense, the didactics of the social sciences, as other specifics, are based on the curricular conceptions that each historical moment privileges, as the curriculum is a social construct reflecting specific educational practices from which problems of didactic interest emerge. In other words, as the same author refers, a historically situated curriculum provides a system in which decisions made about that part of the culture are concretized, which it is considered desirable to know and learn in school by the new generations to integrate into society.

The relationship between technical, practical, and critical prescribed curricula and social science didactics first emphasizes the objective consideration of knowledge based on positivism with behavioral learning to reproduce it and whose teaching is focused on the action of the teacher. Secondly, the knowledge is more subjective depending on the student, and the learning is based on cognitivism that proposes an internal development in interaction with the medium to contribute to the personal development of the apprentice, and the teaching places the teacher as the motivator in the investigation and discovery. Thirdly, knowledge is a social construct based on historical contextualization with an emancipatory purpose, learning is developed from constructivism starting from the previous notions of the student body, and teaching is approached by the teacher as a social praxis (Pagès 1994).

The above is expressed in the didactics of the social sciences with the following characteristics. Teacher training is based on the mastery of scientific knowledge and methods typical of history or geography, under the assumption that no didactic knowledge is required on what and how to teach. A curriculum that occurs in practice raises teaching of social sciences based on everyday life and real problems of students, whose teaching exercise emphasizes the formation of civic and patriotic awareness. Finally, teaching in the social sciences to think critically about reality is directed to the action and transformation of it, in which teachers understand the ideological character of the curriculum, and its practice is directed to the critical thinking of the student.

In the Colombian case where the study is carried out, research on the didactics of social sciences has been of interest since the 1960s for three reasons, as indicated by (Quiroz and Díaz 2011): The strength to professionalize the area of social sciences in the Faculties of Education, the rise of integrationist discourses of all sciences, and the consolidation of social sciences as a specific area, in line with the approaches of the Bucharest Declaration on Science and the Use of Scientific Knowledge (UNESCO 1999). Similarly, little development was seen before its institutionalization in universities, which took a turn with the realization of the National Congress of Pedagogy in 1987, which raised the discussion on the development of an interdisciplinary analysis to rescue the social sciences from the crisis that it was facing.

This initiative is assumed by the Pedagogical Movement as one of the actions of greater citizen and social mobilization for the transformation of education. Subsequently, the National Constituent Assembly and the Political Constitution of 1991 placed at the center of the national discussion the need to move toward a Social State of Law capable of transcending representative democracy to a participatory one. These processes, highlighted by (Quiroz and Díaz 2011), influenced the General Education Law (MEN 1994) to incorporate the changes required in the world and national agendas regarding education and teaching of the social sciences, which, although focused on disciplines of greater tradition, history, and geography, suggests a thematic expansion based on the integration of social sciences.

The research in didactics of the social sciences in Colombia was not initially located in the classrooms with the purpose of transmitting scientific contents or producing learnings about them, but rather encouraging the formation of national values and the development of a general culture that generates tensions in the search for a specific object and theoretical framework on the teaching of this discipline. Thus, it is evident that the evolution of these specific didactics as a field of knowledge has been favored by research on the school curriculum, school knowledge, teaching and learning of the society within and outside the classroom, the political significance of the school, and the need to promote processes of formation in citizenship.

2. Materials and Methods

This work is based on a mixed methodological design that integrates qualitative and quantitative data analysis from an interpretative approach that investigates natural situations trying to make sense of social phenomena according to the meaning given to them by the subjects (Vasilachis 2009). The collection of information was carried out with a questionnaire designed within the framework of the implementation of the project Educación y formación ciudadana del profesorado iberoamericano (Education and citizenship training of Ibero-American teachers). The form was designed with the purpose of collecting information on the perceptions of geographical and historical knowledge of Colombian teachers. The design of the form for data collection was based on the principle of the importance of knowing the perceptions of teachers in order to promote a critical school praxis in the field of Social Sciences (Geography and History) didactics and its teaching at basic levels (Pre-school, Primary, and Secondary Education). The variables analyzed in the questionnaire were the perceptions associated with social sciences, methodologies used to learn social sciences, perception of the usefulness of social sciences, willingness to work in teams, and satisfaction and motivation of teachers regarding their training in the field of social sciences didactics.

This data collection instrument was submitted to a process of validation by judges from whom instructions were received on its design and precision, which were integrated to refine its elaboration. Regarding the ethical considerations of the research, informed consent was integrated into the questionnaire, informing the participants of the academic use of the information, who accepted it together with the completion of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was filled out by 336 social science teachers who participate in social science didactics courses in four universities located in different regions of Colombia. The completion of the questionnaire lasted approximately 45 min. Of the total sample of 336 participants, 55% (185) were practicing teachers and 45% (151) were students or teachers in training. Participating practicing teachers teach from 6th to 11th grade in high school. The participants were selected by means of a simple random sample from a list that included all the participants in the social science didactics courses mentioned above. The sample included 47.9% men and 52.1% women between 18 and 45 years of age.

The systematization of quantitative data had several procedures: Word analysis, descriptive analysis, and correlation analysis. For the word analysis, general cleaning of the words included in the questionnaire was carried out (cleaning of capital letters and arrangement of accents) complemented with a frequency analysis of these words. With this information, frequency tables, averages of the assigned scores, and word clouds were made. The descriptive analysis presents the responses selected by the teachers surveyed by means of frequency histograms. This makes it possible to visualize trends in teachers’ preferences by identifying the most selected options (mode). Likewise, in the section for each question, specifications of the analysis are made given the configurations of the questionnaire for the interpretation of the responses.

To identify the correlations between the different variables captured by the questionnaire, indicators or dummy variables were created to capture the responses of the teachers surveyed. Thus, a dummy variable was created for each response option for each question. With the variables created, a new base was constructed in order to speed up the calculations and facilitate their handling. The Kolmogorov Smirnov test (with a variation of the Lilliefors test to increase robustness) was used to verify whether the available variables are normally distributed or not. It was decided to use this type of test since it is more effective than the Shapiro–Wilk test when working with samples of more than 50 observations. The result of this test for each of the variables shows that they are not normally distributed and, therefore, the correlations made between them should not be made under the parametric Pearson correlation model. Therefore, the correlations were calculated using the nonparametric Spearman rank correlation method with a confidence level of 99%.

3. Results

This section presents the main perceptions of Colombian teachers consulted on the didactics of the social sciences. First, the words teachers associate with these didactics are described. Second, it describes the methodologies that teachers have used to study social sciences. Thirdly, the correlations between the didactics that teachers say they use and the way these didactics contribute to their practice are presented. The revision of the words that teachers associate with the didactics of the social sciences indicated that teaching and learning are the most repeated followed by history, pedagogy, and thought. Table 1 below lists the 20 most frequent words that teachers named, with an average score assigned to them.

Table 1.

Words associated with the didactics of the social sciences.

To complement this frequency analysis, we reviewed the 20 words presented in the table in order to identify other associated factors that teachers relate to didactics in social sciences. The main results are presented below, except for the words that did not present complements in the registered answers (simple words):

- Teachers who wrote teaching relate it to teaching practices, necessary resources, and its link to learning.

- Teachers who wrote learning relate it to meaningful, autonomous, collaborative learning and its link to teaching.

- The teachers who wrote history express it as an area of knowledge in which they can use didactics.

- Teachers who wrote thought relate it to critical, historical, geographical, social, and spatial thinking.

- Teachers who wrote context relate it to the social, historical, and learning environment of students.

- Teachers who wrote knowledge relate it to the students’ prior knowledge, its relationship with the context, and spatial and scientific knowledge.

- The teachers who wrote reflection relate it to their own processes by questioning the content they teach, the critical reflections, the propositional attitude, and the recognition of different perspectives.

- The teachers who wrote space relate it to geography, the physical context of the educational community, the influence of society on the formation processes, and the relationship between time and space.

When teachers were consulted about the words that best identify their idea of didactics of the social sciences, 10 stood out, which are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Words that best relate to the idea of didactics in the social sciences.

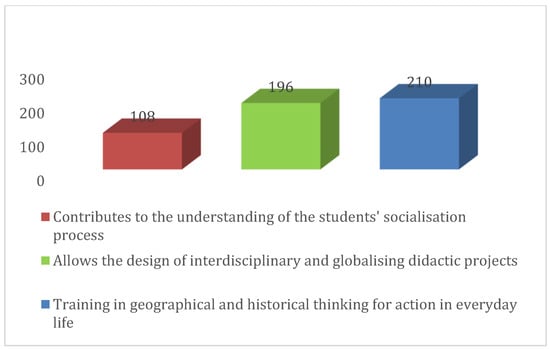

After the questions on the associations and identification of words with the didactics of the social sciences, teachers involved in the research were asked about their usefulness in such teaching. In this question, they could choose more than one option among the three presented, so adding the frequency in the bars of the graph gives a result higher than the 336 responses recorded. Thus, 209 teachers (62%) selected only one option, 76 teachers (23%) selected two options, and 51 teachers (15%) selected all three options.

Figure 1 shows that most teachers consider the didactics of social sciences to be useful for the formation of geographical and historical thought and acting in daily life. In terms of frequency, this option is followed by the alternative that allows the design of interdisciplinary and globalizing didactic projects and the option of contributing to understanding the socialization process of students.

Figure 1.

Usefulness of the social sciences.

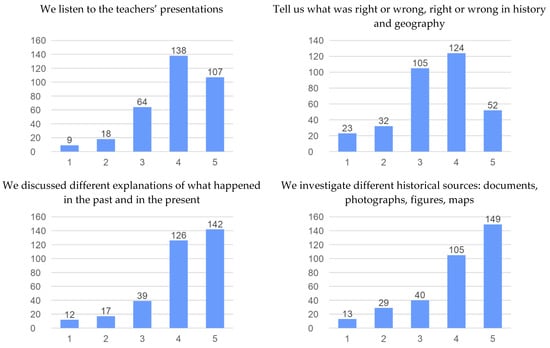

On the other hand, as shown in Figure 2, the teachers’ answers to the question about the methodologies they use most to study social sciences highlight the discussion about different explanations of what happened in the past and what happens in the present, together with the research of different historical sources and the exhibitions of the professors. Likewise, Figure 2 shows methodologies such as visits to museums, projects with the community, and the presentation of information about what was right or wrong in history and geography are not frequently used by the participating teachers.

Figure 2.

Methodologies used to learn social sciences. The data on the horizontal axis correspond to the five words that the participants associated with the didactics of social sciences.

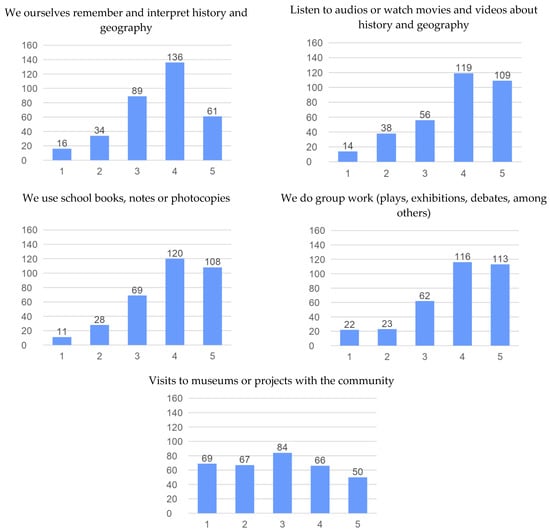

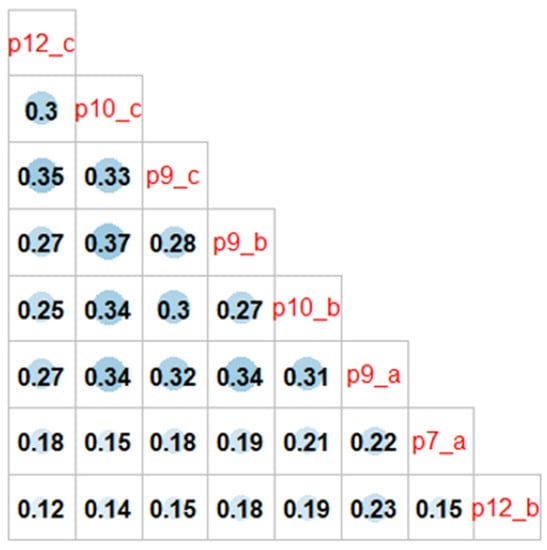

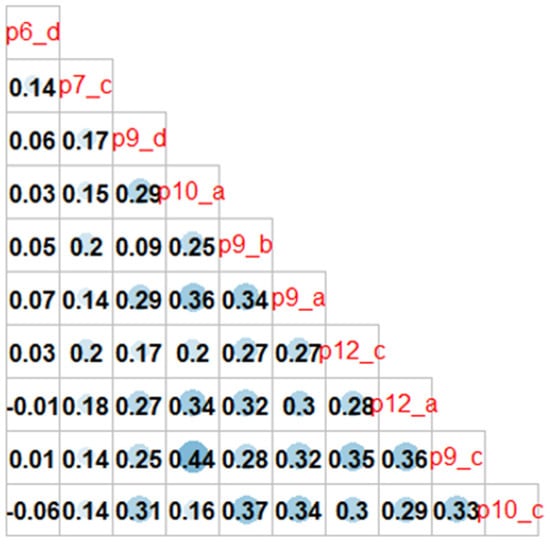

The results of the first correlation show the frequent use of all methodologies used to learn social sciences (Figure 3). However, the highest and statistically significant 99% correlations that stood out were the correlations between interpreting history and geography, investigating different historical sources, listening to audio or watching films about history and geography, discussing explanations about what happened in the past, and doing group work.

Figure 3.

Correlations between the methodologies used to learn social sciences.

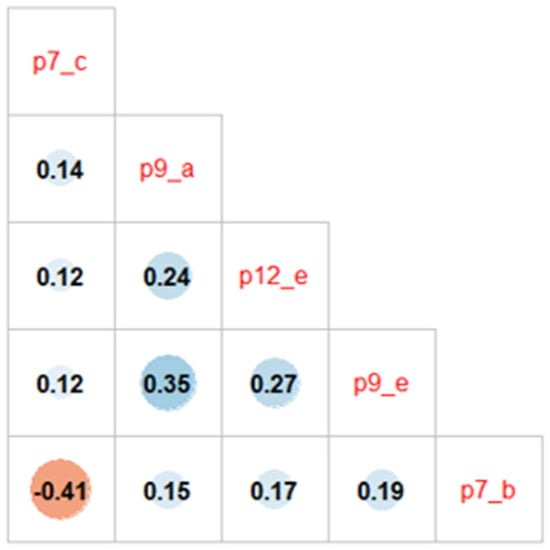

The correlation between the use of social sciences didactics to understand the socialization process of students (Figure 4) is statistically significant at 99%. This significance indicates that when teachers consider that the didactics of social sciences are useful to help understand the process of socialization of students, they tend to use best practices of teamwork, such as offering help to teammates, assessing other opinions, committing to assigned tasks, and promoting the fulfilment of the tasks assigned. In addition, they are provided with dialogue to resolve conflicts and reach agreements.

Figure 4.

Correlation on the use of social science didactics to understand the process of socialization of students.

The correlation between the didactics of social sciences and the design of interdisciplinary and globalizing didactic projects is significant at 99% (Figure 5). This indicates that teachers consider that the didactics of social sciences are useful because they allow them to design interdisciplinary and globalizing didactic, and they tend to think that this area is also useful for the formation of geographic and historical thinking to act in everyday life. They also offer help to their peers when they work as a team and trust the work of their peers.

Figure 5.

Correlations between the didactics of the social sciences and the design of interdisciplinary and globalizing didactic projects.

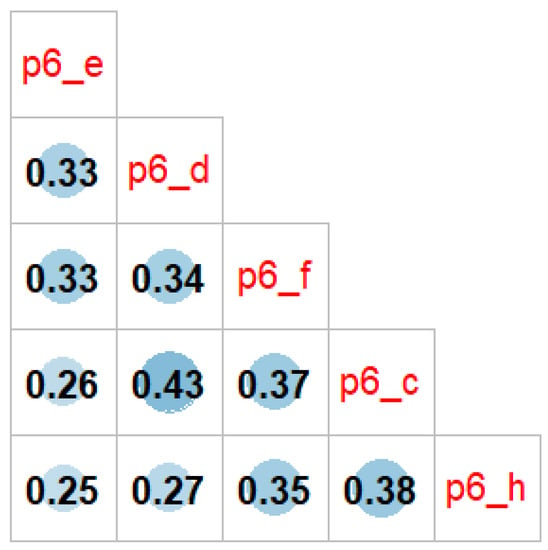

The correlation between the didactics of the social sciences and the formation oriented to geographical and historical thought is significant at 99% (Figure 6). This indicates that when teachers consider the didactics of the social sciences useful for the formation of geographic and historical thinking to act in daily life, they tend to use methodologies such as research in different historical sources such as documents, photographs, figures, and maps. Furthermore, in terms of teamwork, they claim to offer help to their peers, value the opinions of their peers, commit themselves to the assigned tasks, and promote the fulfillment of the tasks assigned. In this sense, communication in these teamwork spaces serves as a platform to clearly express their opinions and facilitate agreements when a conflict arises.

Figure 6.

Correlation between the didactics of the social sciences and the formation oriented to geographical and historical thought.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In general terms, teachers’ perceptions about the didactics of social sciences (Table 1 and Table 2) are related to how important and necessary they consider the learning of the area to be for students to understand the problems of the country and their immediate contexts. Other perceptions expressed by the participants highlight the importance of the role of social science teachers in the communication of a specific school knowledge and the development of social and thinking skills, as well as the orientation of actions that allow for valuing the cognitive, procedural, and value transformations of the students. From the teachers’ perspective, both teaching and learning processes are focused on the possibility that students can understand the social sciences in a comprehensive manner and apply this knowledge to solve problems in their educational practice. Consequently, according to the participating teachers, by teaching concepts and procedures from different social science disciplines such as history, geography, anthropology, politics, or economics, science teachers seek for their students to understand social reality from different points of view.

Thus, the purpose of forming subjects capable of making critical and argued analyses of phenomena of the contemporary world relates to expressions referred to as thought and context by teachers. These perceptions of teachers about the didactics of social sciences seem to be in close accordance with the proposal of the curricular guidelines (MEN 2002). In these guidelines, the Ministry of Education stresses the need to break with the tradition of teaching social sciences from an approach of isolated subjects that prioritizes the transmission of content and not the development of skills. Teachers’ perceptions also coincide with the curricular guidelines in emphasizing the importance of approaching social problems, starting from an integrative or transdisciplinary vision, to achieve a better understanding of the local, national, and global reality.

In this sense, the importance given by teachers to social problems, which in the Colombian case have to do with poverty, exclusion, illegal economy, and violence, pose an important challenge to propose didactics of social sciences from a multidisciplinary viewpoint with holistic and non-fragmented analyses. Consequently, the results of the correlation of social science didactics with the development of historical and geographical thinking (Figure 6) point toward a socio-educational perspective that advances a transdisciplinary and relational notion of social knowledge that transcends reductionist views (García 2014). As stated, such a perspective requires systemic teaching strategies that tend to be integrative for the teaching subject to holistically understand subjects and themes, adapting to the contemporary global context.

In their perceptions, teachers also express their intention to encourage social science didactics that also help them to reflect on social science curricular contents, subjects, and topics (Figure 3 and Figure 5), in order to promote the dissemination and linkage of educational research with the reality of the classroom (Puga 2009). The importance of reviewing curricular content lies in the fact that, from the teachers’ point of view, social science disciplines are often taken as general knowledge, and their formative value for students is not necessarily taken into account. However, as mentioned by Martínez and Quiroz (2012), teachers of these disciplines should try to incorporate updated practices aimed at improving teaching and learning processes that allow students to become agents of social transformation.

With the correlation between the didactics of social sciences and the socialization processes of the students, the idea of educating to understand the problems of our world and develop the necessary competences to intervene in relation to them becomes relevant. There is interest in focusing the teaching of social sciences on education for citizenship, giving special importance to the learning of citizen participation. Thus, for example, programs to promote the participation of students as citizens in the case of Ecoescuelas or Parlamento Joven and the difficulties in integrating proposals such as these into the school curriculum, to be assumed by teachers as part of their educational task (García and De Alba 2007), are the subject of analysis.

Regarding the methodologies that teachers said they used to learn social sciences and those they say they use in their didactics in social science class (Figure 4 and Figure 5), there are differences and that could be encouraging. The fact the teachers consulted had a large number of lectures and little interaction with field trips or visits to museums when they learned social sciences, but they point out that in their methodologies they prefer active pedagogies and more collaborative learning focused on the understanding of the characteristics of the environment and its problems is interesting, because learning that starts from the construction of knowledge in context and its problems not only promotes a higher level of involvement and interest of students in school, but also encourages students to link with the solution of everyday problems (Palacios 2018).

In coherence with the above, a critical issue in the field of social science didactics is the contrast between teachers’ perceptions, such as those shown in this paper, and their practices (Palacios 2018). Works carried out for Colombia in geography (Arias 2014; Palacios and Romero 2017) and in the field of history (Palacios et al. 2020; Palacios 2021), in history, have evidenced the prevalence of basic and insignificant learning activities that do not increase higher and complex cognitive, procedural, or attitudinal developments in students. From the perspective of Palacios et al. (2020) and Palacios and Romero (2017), part of the research in social sciences didactics has shown that students limit themselves to repeating content without reaching a minimum level of understanding. As the content is presented in the classroom, students’ tasks are reduced to basic mental operations (Sáiz and Gómez 2016), knowing how to locate and extract literal information from an academic text, a written source, a map, a graph, an axis, or an image. They only involve skills of reading, describing, locating, repeating, reproducing, or memorizing textual or iconic information at a basic level. Fewer activities are promoted that go beyond recalling phenomena or events and passing information back and forth with little or no comprehension.

The results of the article highlight the importance of collecting the perceptions of future teachers and those who are already practicing, since we agree with the approaches of Gómez et al. (2018) and Martínez et al. (2006) who emphasize that inquiring into the perceptions of history teachers in training and practice can give us a perspective of what needs to be changed in the didactics of the discipline. The analysis of such perceptions also contributes to the reflection on the visions that teachers have about the influence of the weight of the disciplinary code of Geography and History and the numerous continuities that preside over the school day-to-day (Parra and Morote 2020; Parra et al. 2021). It also helps to contrast the relationship between teachers’ perceptions and their practices because, as evidenced by Araya and De Sousa (2018) perceptions and practices do not always coincide, and although in the perceptions there is a rhetoric that poses a clear openness to innovation, in practice, it is not possible to identify any intentional long-term process for the development of spatial reasoning modalities that allow the development of higher skills of geographical thinking.

Consequently, Martínez et al. (2006) and Gómez et al. (2018) concluded that inquiring into the perception of history teachers in training and practice can give us a perspective of what needs to change. Parra and Morote (2020) and Parra et al. (2021) also conclude that consulting future teachers reveals the weight of the disciplinary code of Geography and History and the many continuities that preside over the school day-to-day. Students (future teachers) are able to criticize the methodologies that characterized their classes, but they take into account several factors when evaluating their memories, among them the role of the teaching staff. Coinciding with the previous conclusion, a study by Araya and De Sousa (2018) in which practicing geography teachers were consulted about their methodologies showed that strategies are guided by social conceptions and mediated by interactions between students and teachers. However, Araya and De Sousa (2018) did not visualize any intentional long-term process for the development of spatial reasoning modalities that allow the development of higher skills of geographic thinking. This long-term social and historical process transcends the objectives of this article.

We emphasize the relevance of this article on Colombian teachers’ perceptions of social science didactics because our findings are in accordance with those of researchers such as Guo et al. (2022), Smet (2022), and Avidov-Ungar et al. (2021), who pointed out that teachers’ motivation and aspirations about their teaching, as expressed in their perceptions, constitute an essential tool to help managers and decision makers analyze how they guide teachers’ training programs and professional development. Therefore, the perceptions of the participants in this study can be very useful in designing professional development programs and incentives that would correspond to the needs of social studies teachers in the country.

5. Limitations

A main limitation of the study was the difficulty of working with teachers from private schools of the same socioeconomic stratum as the participants and higher strata, since the invited teachers did not accept the invitation. It was also a limitation not to be able to work with a more heterogeneous spectrum of public schools, possibly because some schools considered that participating in a research process took time away from teachers and delayed their academic calendars. It is necessary to add that, due to the number of participating teachers and their characteristics, the findings of the study are not generalizable to other groups of Colombian teachers, such as those living in areas highly impacted by the armed conflict and in rural areas.

Author Contributions

The authors’ contributions were as follows: literature review N.P.M., L.P. and D.G.M., collection of empirical information N.P.M. and L.P., systematisation of empirical information N.P.M. and L.P., analysis of information D.G.M., preparation of the text of the manuscript N.P.M., L.P. and D.G.M., revisions of the final text N.P.M., L.P. and D.G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Innovation, Universities, Science and Digital Society of the Generalitat Valenciana within the framework of the project “Education and citizen training of Ibero-American teachers: knowing the representation of geographical and historical knowledge to promote critical school praxis” (GV/2021/068). This project is endorsed by the Faculty of Education of the Universidad de los Andes, Research The learning of social sciences and the development of competencies in primary and secondary school.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This project has been endorsed by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Education of the University of the University of the Andes by act number 009 of 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

In order to receive the endorsement of the Faculty of Education of the Universidad de los Andes, informed consents were provided to the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The empirical information is in digital and printed archives of the Faculty of Education of the Universidad de los Andes and will be available for the next 5 years.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aguilera, Alcira, and María González. 2009. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales para la Educación Infantil. Bogotá: Kimpres Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Aisenberg, Beatriz. 1998. Didáctica de las ciencias sociales: ¿desde qué teorías estudiamos la enseñanza? Revista de Teoría y Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales 3: 136–63. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/120721 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Araya, Fabian, and Lana De Sousa. 2018. Desarrollo del pensamiento geográfico: Un desafío para la formación docente en Geografía. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande 70: 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, Diego. 2014. La enseñanza de las ciencias sociales en Colombia: Lugar de las disciplinas y disputa por la hegemonía de un saber. Revista de Estudios Sociales 52: 120–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, Orit, Hayak Merav, and Sivan Cohen. 2021. Role Perceptions of Early Childhood Teachers Leading Professional Learning Communities Following a New Professional Development Policy. Leadership and Policy in Schools 20: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benejam, Pilar. 2004. De la teoría … a l’aula. Reflexions sobre fer de mestre. Llü;ó magistral. Paper presented at the III Simposium Sobre l’Ensenyament de les Cimcies Socials, Barcelona, Spain, October 2; pp. 3–11. Available online: https://jornades.uab.cat/dcs/sites/jornades.uab.cat.dcs/files/lli%C3%A7%C3%B3%20magistral%20Pilar%20Benejam.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Bronckart, Jean-Paul. 1989. Du statut des didactiques des matières scolaires. Langue Française 82: 53–66. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/lfr_0023-8368_1989_num_82_1_6381 (accessed on 26 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Camilloni, Alicia. 1994. Epistemología de la didáctica de las ciencias sociales. In Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Aportes y Reflexiones. Edited by Beatriz Aisenberg and Silvia Alderoqui. Buenos Aires: Paidós, pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Castellar, Sonia Maria Vanzella, Marcelo Garrido-Pereira, and Nubia Moreno Lache. 2021. Geographical Reasoning and Learning: Perspectives on Curriculum and Cartography from South America (International Perspectives on Geographical Education). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, Cesar. 1996. Piaget, el constructivismo y la educación escolar: ¿Dónde está el hilo conductor? Substratum III: 153–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chevallard, Yves. 1997. La Transposición Didáctica. Del Saber Sabio al Saber Enseñado. Buenos Aires: Aique. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, Linda. 2017. Empowered Educators: How High-Performing Systems Shape Teaching Quality around the World. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Ovidio. 2003. Debates Sobre el Espacio en la Geografía Contemporánea. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, Claudio, María I. Solar, Valentina Soto, and Marianela Conejeros. 2015. Las percepciones de los profesores respecto a la investigación e innovación en sus contextos profesionales. Revista Actualidades Investigativas en Educación 15: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Ronald. 1993. Ideology and the teaching of History: Purposes, practices and student beliefs. In Cases Studies of Teaching and Learning in Social Studies. Advances in Research on Teaching. Edited by Jere Brophy. Muncie: Ball Estate University, pp. 179–214. [Google Scholar]

- García, Francisco, and Nicolás De Alba. 2007. Educar en la participación como eje de la educación ciudadana. Reflexiones y experiencias. Didáctica Geográfica (Segunda Época) 9: 249–64. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2328933 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- García, Lewis. 2014. Aprendizaje y vida. Construcción, didáctica, evaluación y certificación de competencias en educación desde el enfoque socioformativo. Espiral Revista de Docencia e Investigación 4: 85–94. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282135359_APRENDIZAJE_Y_VIDA_CONsTRUCCION_DIDACTICA_EVALUACION_Y_CERTIFICACION_DE_COMPETENCIA_EN_EDUCACION_DESDE_EL_ENFOQUE_SOCIOFORMATIVO (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Giménez, Jesús, Rosa Ávila, and Rocío Ruíz. 2007. Concepciones sobre la enseñanza y difusión del patrimonio en las Instituciones Educativas y los Centros de Interpretación. Estudio Descriptivo. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 6: 75–94. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/EnsenanzaCS/article/view/126332/190680 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Gómez, Cosme, Raimundo Rodríguez, and Ana Mirete. 2018. Percepción de la enseñanza de la historia y concepciones epistemológicas. Una investigación con futuros maestros. Revista Complutense de Educación 29: 237–50. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/RCED/article/view/52233 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Guo, Liping, Mingming Huang, Shi Song, Jili Bi, Yaqin Wang, Jinlong Liang, Yujie Wang, and Aiqin Sun. 2022. Latent analysis of the relationship between burnout experienced by Chinese preschool teachers and their professional engagement and career development aspirations. Early Years, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, Sandra, and Milton Trujillo. 2008. Reflexiones sobre la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales: Aportes para los docentes que orientan la enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales en los niveles educativos básico y media. Pedagogía y Saberes 28: 93–104. Available online: https://revistas.pedagogica.edu.co/index.php/PYS/article/view/6881/5616 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Imbernón, Francisco. 2012. Un nuevo desarrollo profesional del profesorado para una nueva educación. Revista de Ciencias Humanas 12: 75–86. Available online: http://revistas.fw.uri.br/index.php/revistadech/article/view/343 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Lenzi, Alicia. 1998. Psicología y Didáctica: ¿Relaciones ‘peligrosas’ o interacción productiva?: Una investigación en sala de clase, sobre el cambio conceptual de la noción de gobierno. In Debates Constructivistas. Edited by Ricardo Baquero, Mario Carretero, Jose Castorina, Alicia Lenzi, Edith Litwin and Alicia Camilloni. Buenos Aires: Aique, pp. 69–114. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3790033 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Lerner, Delila. 1996. La enseñanza y el aprendizaje escolar. Alegato contra una falsa oposición. In Piaget-Vigotsky: Contribuciones para Replantear el Debate. Edited by José A. Castorina. Buenos Aires: Paidós Educador, pp. 69–118. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2054924 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Lévesque, Stéphane, and Paul Zanazanian. 2015. History Is a Verb: “We Learn It Best When We Are Doing It!”: French and English Canadian Prospective Teachers and History. Revista de Estudios Sociales 52: 32–51. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-885X2015000200004 (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Martínez, Iván, and Ruth Quiroz. 2012. ¿Otra manera de enseñar las Ciencias sociales? Tiempo de Educar 13: 85–109. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/311/31124808004.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Martínez, Nicolás, Xose Souto, and José Belrán. 2006. Los profesores de historia y la enseñanza de la historia en España. Una investigación a partir de los recuerdos de los alumnos. Enseñanza de las ciencias sociales: Revista de investigación 5: 55–71. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/EnsenanzaCS/article/view/126317 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia. 1994. Ley 115 de 1994. Congreso de la República de Colombia. Available online: https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-85906_archivo_pdf.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional de Colombia. 2002. Lineamientos Curriculares de Ciencias Sociales. Available online: http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/article-87874.html (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Muñoz, Carlos. 2006. Percepciones de los profesores de historia y ciencias sociales de su profesión. Un estudio fenomenológico. Horizontes Educacionales 11: 1–16. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3993021 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Nikolopoulou, Kleopatra. 2020. Secondary education teachers’ perceptions of mobile phone and tablet use in classrooms: Benefits, constraints and concerns. Journal of Computers in Education 7: 257–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2009. Evaluating and Rewarding the Quality of Teachers: International Practices. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Pagès, Joan. 1994. La didáctica de las ciencias sociales, el currículum y la formación del profesorado. Signos Teoría y Práctica de la Educación 5: 38–51. Available online: http://www.quadernsdigitals.net/datos_web/hemeroteca/r_3/nr_39/a_617/617.html (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Palacios, Nancy. 2018. Perceptions of Secondary School Students of the Social Science Class: A Study in Three Colombian Institutions. International Journal of Instruction 11: 353–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, Nancy. 2021. The Development of Historical Thinking in Colombian Students: A Review of the Official Curriculum and the Saber 11 Test. International Journal of Instruction 14: 121–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, Nancy, and Alison K. Reedy. 2022. Teaching practicums as an ideal setting for the development of teachers-in-training. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado: Continuación de la antigua Revista de Escuelas Normales 97: 243–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, Nancy, and Olga Romero. 2017. El espacio cercano y la enseñanza de las ciencias sociales en el primer ciclo de la escuela primaria. Anekumene 14: 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, Nancy, Luz Chaves, and William Martin. 2020. Desarrollo del pensamiento histórico. Análisis de exámenes de los estudiantes. Magis, Revista Internacional de Investigación en Educación 13: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, David, and Alvaro Morote. 2020. Memoria escolar y conocimientos didáctico-disciplinares en la representación de la educación geográfica e histórica del profesorado en formación. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado: Continuación de la antigua Revista de Escuelas Normales Continuación De La Antigua Revista De Escuelas Normales 95: 11–32. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7856914 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Parra, David, Xose M. Souto, and Nancy Palacios. 2021. The representation of geographical and historical education among teachers-in-training: An Ibero-American perspective. In Handbook of Research on Teacher Education in History and Geography. Edited by Cosme Gómez, Pedro Miralles and Ramón López-Facal. Berlin: Peter Lang Gmb, pp. 115–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, Ángel. 2010. Aprender a educar. Nuevos desafíos para la formación de docentes. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación de Profesorado 24: 37–60. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/274/27419198003.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Portela, Antonio, Nicolás Martínez, and María García. 2014. La voz de los alumnos como testimonio vivo. In La Historia de España en los Recuerdos Escolares. Análisis y Poder de Cambio de los Testimonios de Profesores y Alumnos. Edited by Nicolás Martínez. Valencia: Nau Llibres, pp. 101–27. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5382370 (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Prats, Joaquim. 1999. La enseñanza de la historia y el debate de las humanidades. Tarbiya: Revista de Investigación e Innovación Educativa 21: 57–76. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/histodidactica/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=80:la-ensenanza-de-la-historia-y-el-debate-de-las-humanidades&catid=24:articulos-cientificos&Itemid=118 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Prats, Joaquim. 2002. Hacia una definición de la investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 1: 81–89. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/EnsenanzaCS/article/view/126132 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Puga, Cristina. 2009. Ciencias sociales: Un nuevo momento. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 71: 105–31. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-25032009000500005&lng=es&tlng=es (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Quiroz, Ruth, and Ana Díaz. 2011. La investigación en el campo de la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales y su dinámica de articulación en un grupo de universidades públicas en Colombia. Uni-Pluri/Versidad 11: 10–25. Available online: https://revistas.udea.edu.co/index.php/unip/article/view/11075 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Rodríguez, Liliana, Nancy Palacios, and Xosé Souto. 2019. La Construcción Global de una Enseñanza de los Problemas Sociales Desde el Geoforo Iberoamericano. Barcelona: Geocrítica Textos Electrónicos. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/geoforo_ub_digital_2020.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Rudduck, Jean. 2006. The past, the papers and the project. Educational Review 58: 131–43. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00131910600583993 (accessed on 15 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Rudduck, Jean. 2007. Student voice, student engagement, and school reform. In International Handbook of Student Experience in Elementary and Secondary School. Edited by Dennis Thiessen and Alison Cook-Sather. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 587–610. [Google Scholar]

- Rudduck, Jean, and Donald McIntyre. 2007. Improving Learning through Consulting Pupils. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudduck, Jean, and Julia Flutter. 2000. Pupil participation and pupil perspective: ‘carving a new order of experience’. Cambridge Journal of Education 30: 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáiz, Jorge, and Cosme Gómez. 2016. Investigar el pensamiento histórico y narrativo en la formación del profesorado: Fundamentos teóricos y metodológicos. Revista Electrónica de Formación del Profesorado 19: 175–90. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5315542 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- San Fabián, José. 1988. Percepción de la Escolaridad por el Alumnado al Final de la E.G.B. Madrid: Centro de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia de España. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Raquel, José Campillo, and Catalina Guerrero. 2020. Percepciones del profesorado de primaria y secundaria sobre la enseñanza de la historia. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado: Continuación de la antigua Revista de Escuelas Normales 34: 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, Alfred. 1962. El Problema de la Realidad Social. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu. [Google Scholar]

- Smet, Mike. 2022. Professional Development and Teacher Job Satisfaction: Evidence from a Multilevel Model. Mathematics 10: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Sthepen. 1991. Teachers as Curricular- Instructional Gatekeeper in social Studies. In Handbook of Researches on Social Studies Teaching and Learning. A Project of National Council for the Social Studies. Edited by James Shaver. New York: MacMillan, pp. 237–48. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 1999. Declaración sobre la Ciencia y el Uso del Saber Científico y Programa en Pro de la Ciencia: Marco General de Acción. Conferencia General, 30th. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000116994_spa (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Vasilachis, Irene. 2009. Estrategias de Investigación Cualitativa. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial, S.A. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2017. World Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Di. 2020. Gamified flipped EFL classroom for primary education: Student and teacher perceptions. Journal of Computers in Education 7: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).