Abstract

The gender gap in voting for far-right parties is significant in many European countries. While most studies focus on how men and women differ in their nationalist and populist attitudes, it is unknown how the socio-economic and political promotion of women is associated with the gender gap in far-right political orientation. The following paper compares the effect of four different spheres of gender equality on this gender gap. By estimating multilevel logit models for more than 25 European countries and testing the mechanism via a socially conservative attitude toward gendered division of work, I find that the visible field of representation in particular—measured by the share of women in parliament and women on boards—is associated with a gender gap in far-right orientation. This paper contributes to the literature in two important ways: first, it combines policy feedback with cultural backlash theory, enlarging the scope of both theories; second, it demonstrates the importance of gender equality policies for the study of the far-right gender gap.

1. The Puzzle: The Gender Gap in Far-Right Voting

Sex is the main sociodemographic variable that is consistently relevant for describing far-right voters in almost all European countries (Donovan 2022; Givens 2004; Harteveld and Ivarsflaten 2016; Ralph-Morrow 2022). While the sex ratio regarding support for other parties is balanced, around two-thirds of far-right voters are male (Mudde 2007). Neither education, employment status, occupation type, nor attitudes towards immigration can sufficiently explain this gap (e.g., Harteveld et al. 2015; Spierings and Zaslove 2015). So, why do men vote more often for the far-right?

Although some studies have already investigated this, they have not been able to sufficiently explain variations between countries regarding the male over-representation among the far-right electorate.1 Based on the fact that men and women undergo different forms of socialization, these studies argue that men are more likely to have authoritarian, extremist, and populist attitudes, which, in turn, increase their attraction to extremism and their probability of voting for far-right parties (Harteveld et al. 2015; Immerzeel et al. 2015; Spierings and Zaslove 2017). This reasoning might lead one to expect larger gender gaps among far-right voters in countries with conservative gender roles than in countries with liberal gender roles where men and women do not differ much in their socialized attitudes (e.g., Eagly et al. 2004). However, this is not the case, either: as the European Election Study 2019 demonstrates, social-democratic, egalitarian countries are among those with the highest gender gap. Based on this logic of gendered socialization, one would also expect the variation in the gender gap to be related to varying extremist images of specific far-right parties (see Harteveld and Ivarsflaten 2016). Far-right parties with an extremist image in society should have a higher share of men as supporters than far-right parties that cultivate a moderate public image, which is, however, not the case. Similarly, far-right parties that become more radical over time should report an increase in male voters and decrease in female voters as women should be deterred by the programmatic change. However, this is not necessarily the case: following its transformation from a Eurosceptic to a radical-right party, for example, the gender gap in the voter profile of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) only increased by two percentage points and is not statistically significant (Arzheimer and Berning 2019). If extremist and authoritarian attitudes are more prevalent among men, one would expect men to a higher, and women to a lower degree to be attracted by the rising extremist image and programmatic profile of the AfD. In addition to the extremist image of far-right parties, other characteristics, such as their populist discourse style and self-portrayal as outsiders, do not vary with the cross-national gender gap (Immerzeel et al. 2015). Thus, the knowledge on the cross-national gender gap in far-right orientation is still low and not satisfactory. An exception is a new study from Donovan (2022) which exploratively tests different causes for the gender gap in multilevel models, finding that the number of Catholics in a country and the gender equality index plays a role. The present study takes Donovan’s as its departure point, further elaborating the so-called gender-equality ‘threat’ as a hypothesis with which to try to solve the puzzle of the varying gender gap in far-right voting between European countries.

In the present article, rather than focusing on socialized attitudes, I propose a theoretical mechanism based on cultural backlash theory (Norris and Inglehart 2019) and the relative deprivation of formerly privileged groups to explain the gender gap in far-right orientation. This might also improve our understanding of how policy feedback affects political orientation.

More precisely, this paper is based on the argument that increased “feelings of aggrieved entitlement” (Kimmel 2017) among formerly privileged groups due to various liberal policy adaptions, such as the promotion of women in the professional sphere, have created windows of opportunity for men to backlash against these liberal turns electorally (Norris and Inglehart 2019). In general, political parties in government are expected to enact social policies that protect and promote specific social groups with economic risks. While governing political parties placed the emphasis on old social risks during the time of effective male breadwinner income models, such as old age and unemployment, they shifted towards “capacitating fairness” (Dworkin 1981; Sen 1992) and new social risk in the 2000s. Among the new social policies developed were ones for integrating female labor capacities into the post-industrial economies (Hemerijck 2013; Morgan 2013), such as increased spending on childcare facilities, parental leave, tax incentives for dual earners, gender quotas, and the ratification of laws on equal pay. These changes took place when classical male policy protection and long-term unemployment benefits were decreasing (Fleckenstein 2010; Jaumotte 2003; Gauthier 2002; OECD 2019a). Scholars have argued that the focus of governments and employers on making work and family life compatible for women evoked feelings of neglect among some men toward mainstream parties. When “the era of unquestioned and unchallenged male entitlement [was] over" (Kimmel 2017, p. 12), some men turned away from established parties and toward far-right ones, which often hold socially conservative views on gender topics. These parties promise a return to old times, when inter alia men were breadwinners and women were predominantly housekeepers, as exemplified by Björn Höcke from the Alternative for Germany (AfD), who said that men have to “rediscover […] masculinity” (2015). In this article, I argue that the so-called silent postmaterialist revolution (see Norris and Inglehart 2019), also expressed in policies and labor opportunities for women, has reshaped the political playing field, compelling some men to orientate toward the far-right. To test these theoretical expectations, I pose the following two research questions: to what extent is the political and socio-economic promotion of women associated with the gender gap in far-right political orientation, and do attitudes toward gender equality moderate this gender gap? I answer the research questions by comparing the effect of four different spheres of gender equality on the gender gap in far-right political orientation.

The rest of this article unfolds as follows. First, I summarize the literature and set out the theoretical reasoning derived from cultural backlash theory and the approach of policy feedback. Then, I introduce the method of analysis, data, and variables, for which I used the European Values Study (EVS) in 2008 and 2017 and country-level data on (at least) 25 European countries from different datasets. Next, I present and discuss the findings of the mixed multilevel logit models, before drawing conclusions on the effects of the promotion of women on the gender gap in far-right political orientation.

2. Previous Explanations for the Gender Gap in Far-Right Voting/Political Orientation

The most prominent explanation for why women do not vote as much as men for far-right parties is “a certain resistance towards extremism” (Harteveld et al. 2015; Spierings and Zaslove 2017). The reasoning behind this is that the “extremist image” of far-right parties keeps women from voting for them, rather than the parties’ radical right ideology, or more precisely, their “conservative positions on gender issues” (Mudde 2007, p. 116). Harteveld et al. (2015) add that women are more strongly deterred by the political style of far-right parties, but do not differ from men regarding their authoritarian attitudes or (dis)satisfaction with democracy. This attributes the reason for the gender gap to the different socialization of men and women, as exemplified by the normative variance of ‘correct behavior’ between the sexes (Spierings and Zaslove 2017) and the varying motivation to control prejudice (Harteveld and Ivarsflaten 2016). However, as highlighted in the introduction, attitudes and personality traits relying on socialization cannot explain varying gender gaps between countries. The countries do not cluster along our expectations (countries with traditional gender socialization do not have smaller gaps than liberal ones). Thus, the socialization hypothesis might hold when comparing individuals, but not for countries. This first problem of the previous literature is, therefore, the lack of identifying variables at the country level to explain cross-national variation. The second problem of the “demand side” literature on far-right voting is that they largely rely on macro- and meso-level explanations, for example, socialization processes (Spierings and Zaslove 2017), but measure them at the micro-level by examining specific attitudes, such as interest in politics, political efficacy, religiosity, or extremism (an exception is Mierina and Koroleva 2015). Thus, the theoretical arguments require empirical support at the meso- and macro-levels; until then, it will remain unclear where these attitudes come from, and thus why men are more inclined than women to vote for far-right parties. A third problem of previous studies on the far-right gender gap is that there is hardly integration of gender research. The research mainly has its origins in the far-right literature, using their explanations, e.g., by comparing anti-immigration attitudes between sexes. The—unspoken—expectation is here that sexes differ by nature and socialization, e.g., men are more authoritarian. However, assuming that voters want to maximize their utility and assuming that the utility of policies differs between sexes, one might expect that men and women have different reasons for choosing/rejecting parties. Therefore, it is necessary to ask how gender specific attitudes and policies are related to the gender gap. An innovative approach is provided by Allen and Goodman (2021), who compare the voter profiles and motivation of men and women separately, finding that women employed in routine nonmanual work who have progressive chauvinist views (e.g., on same-sex marriage) favor far-right parties. More precisely, they find that attitudes in favor of gay equality are positively associated with women voting for the far right, while these attitudes are negatively related to far-right support among men. Thus, far-right parties are faced with a programmatic trade-off since their electorate diverges on core social issues. Even though the authors do not elaborate on this trade-off on the political party supply side, it shows that it might be worthwhile to look at the national status of different gender policies, as this is the playing field on which far-right parties position themselves on gender.

In the present article, I argue that the gender gap in far-right orientation is also the result of a backlash against the silent post-materialist revolution, which also includes the promotion of women in different political and socio-economic spheres. However, this strand of literature has only been considered to a very limited extent as explanatory for far-right voting (exceptions are Burgoon et al. 2019; Vlandas and Halikiopoulou 2018). The introduction and rejection of specific policies, as well as paradigm shifts, can explain a changing political orientation, expressed in the establishment of new parties (e.g., the Pirate parties, or the Brexit Party in the U.K.), the increasing support for certain political parties (the far-right, but also the Greens), or decreases in support for other parties. In the present article, I argue that the gender gap in far-right political orientation is also linked to the promotion of women in politics and the professional world. This theoretical macro–micro model of the relative deprivation of some men caused by the increased focus on promoting women politically and economically is tested by mixed logistic multilevel models with both individual characteristics and contextual level variables (Arzheimer 2009).

3. Cultural Backlash Theory and Policy Feedback Theory: Relative Male Deprivation

The theoretical framework for this study is based on cultural backlash theory (Norris and Inglehart 2019) embedded in policy feedback theory (Moynihan and Soss 2014). While the causal mechanism stems from the former, the set of independent variables derives from policy feedback theory.

The cultural backlash theory by Norris and Inglehart (2019) is grounded on the observation that a silent revolution toward post-materialist values has been taking place since the 1970s, when the conventional attitudes and norms of socially conservative individuals were challenged. Feeling threatened by the dominance of cultural issues in politics—for example, same-sex marriage and the integration of ethnic minorities—on which most parties had adopted liberal stances, this group of voters turned toward socially conservative and authoritarian values (Allen and Goodman 2021; Norris and Inglehart 2019). This is a mechanism of relative deprivation, as members of a particular social group changed their political behavior and attitudes due to subjective perceptions of other groups and former times. Recognizing that the cultural norms and values they believed in were no longer supported by either the majority of the population or most political representatives, they expressed their discontent by shifting toward the far-right (Ignazi 1992, 2003). Not only does competition with immigrants, a well-known motive for far-right support, produce a sense of declining status (Gest et al. 2018; Rydgren 2013), but female empowerment provokes feelings of (white) male neglect. In this instance, far-right orientation represents support for “redemptive politics” (Canovan 1999), as it communicates the desire to restore the focus of welfare policy on old social risks, men in leadership positions, and women in gender-stereotypical professions and/or as care worker at home. Looking at the supply side of the argument, far-right parties, despite their programmatic diversity, offer a political home for those individuals who want to maintain the gendered division of work and heteronormative patriarchal families and/or favor a femonationalism, where women need to be protected from immigrants (Santos and Roque 2021). Thus, far-right parties promote the reproductive function of traditional families and women’s role as caretakers, while simultaneously opposing the sexual rights of women alongside LGBTIQ+ rights (Köttig et al. 2017; Santos and Roque 2021).

Who are the socially conservative voters that have become more authoritarian in recent years? Norris and Inglehart (2019) argue that the post-materialist triumph especially threatens those who suffer from (cultural) grievances due to their age and/or education. College education is considered to play a key role in establishing socially liberal values, evidenced, inter alia, by the division of education in the Brexit referendum and the below-average level of education among Trump supporters (Ford and Goodwin 2017). Furthermore, while the interwar and baby boomer generations made up the electoral majority for several decades, newer generations were subject to a broad educational advancement, leading to the silent cultural revolution (Norris and Inglehart 2019). In fact, earlier generations are proven to have more conservative values (Tilley and Evans 2014), and the gender gap in political orientation is driven especially by a change among older generations (Dassonneville 2020).

But what structures influence attitudes about gender equality? I argue that cultural norms are also embedded and expressed in policies as socially progressive values, but also in corporate goals, against which some men backlash and feel relatively deprived. Assuming that “policies, once enacted, restructure subsequent political processes” (Skocpol 1992, p. 58), I expect, for example, social policies to regulate gender relations by defining female rights and pushing companies to engage in gender equality measures. Besides, policies inform the public about civic standing, group deservingness, and the nature of social problems (Schneider and Ingram 2005; Soss and Schram 2007). Thus, policies at the state and business level can actually give lessons on the social and political status of specific groups and adjust political preferences and attitudes (Soss 2005). I propose here a self-undermining, general, and long-term feedback effect (Busemeyer et al. 2019), meaning that different policies associated with increasing the representation and the resources of women have encouraged the population to reinterpret gender relations and that these reinterpretations differ between sexes and come into play after a certain time. For instance, the expansion of childcare provision and other dual-earner arrangements has led to a greater advocacy of an egalitarian division of work and family life (Neimanns 2020; Pedulla and Thébaud 2015), since the set-up and expansion of professional childcare led to a rethink about the ideal conditions for children to grow up in, as well as about the role mothers have in childcare, and passed these on as new cultural norms. In Norway, the establishment of a universal childcare system increased support for ‘childcare services only’ as the best form of care by about 30 percentage points (Ellingsæter et al. 2017). Similarly, gender quotas on boards and parliamentary representation communicate that women can do these jobs as well and are not slated to take care of family and home only. A number of social policies and corporate measures have been enacted in recent years in Europe, which can be considered as a very significant break from socially conservative norms regarding the obligations of motherhood.

In comparison to other policy studies that analyze feedback effects on targeted groups or the mass public, I expect (some) men as a non-targeted group to perceive the increased focus on gendered family policies as a threat to social entitlements associated with old risks (e.g., unemployment, inability, ageing). Thus, while the majority of studies analyze whether policies can intensify or alleviate the marginality of disadvantaged groups (Mettler and Soss 2004), this paper analyses whether social policies at the national and corporate level can also influence the relative deprivation of formerly advantaged groups that are not targeted with these policies. My precise argument is that if these policies are shown to be less for and about people like them, they might turn away from mainstream parties and classify themselves as far-right. Thus, the promotion of women in politics and professional life might create opposition not only to its continued provision, but also to “mainstream” parties supporting these policies and the associated turn in liberal values (see Busemeyer et al. (2019) ‘self-undermining direction of feedback’).

Which spheres of gender equality might drive men to favor the far-right? I take an elaborative stance here and test the effect of the promotion of women in the political and professional realms regarding their representation and resources. In Table 1, the four studied spheres of gender equality are presented in a 2 × 2 matrix.

Table 1.

Spheres of gender equality.

I selected these four measures of gender equality because of their relevance and importance in the European context, as they are either in the focus of public debate and/or have undergone changes in the last couple of years. For instance, to illustrate the relevance of these spheres, the Council of Europe, which defines gender equality as “equal visibility, empowerment and participation of both sexes in all spheres of public and private life […]” (Council of Europe 2016), highlights the gender wage gap and the unrepresentative number of women in parliament as key challenges. There are alternative policies to those studied here, such as parental leave, that are also heavily discussed in public discourse. However, while parental leave, for example, has changed in some countries (e.g., Germany), it is not subject to policy-making in others (e.g., Switzerland, U.K.), which makes it difficult to establish a valid argument for this gender equality measure. Furthermore, Akkerman (2015) shows that for the six electorally most successful far-right parties in Europe, labor market participation, political participation, and public childcare are among those most discussed gender policies in manifestos.

Since my argument hinges on an unspecific, diffuse group of women that are promoted in public—political and socio-economic—life, all four variables deal with gender equality in public life. This is also why indicators on private life (e.g., domestic abuse) would be unsuitable. Besides, health (e.g., maternal mortality) and education issues (e.g., female population with at least secondary education), which are part of the Gender Inequality Index (GII) of the United Nations Development Program, are not important for the countries studied here, as I do not expect inequality and large variation among them. Instead, I focus on the political and socio-economic spheres, as these are publicly visible and relevant to my thesis.

Representation is the most visible form of the promotion of women and equal rights are a prerequisite for it. Resources subsume the available opportunities women have to take part in public life, which is why I focus on this dimension next to representation. Female participation in paid work increases the well-being of women and is a cornerstone of today’s labor market policies in Europe. Having a paid job allows women to participate to their full potential in public life and demonstrates their ability as equal workers. Thus, seeing women on boards or knowing of a low wage gap might arouse feelings of aggrieved entitlement among some men who have considered the labor market as their exclusive playing field. Furthermore, as I focus on political orientation, looking at gender equality in the political sphere is a logical step. Gender equality in political institutions is considered key for good governance and the fairness of political processes and outputs. To see that the legislative body of a country is largely made up of women suggests that women hold powerful positions, too, and can decide on key issues. The representation of women on boards and in parliament is also often based on policies promoting gender quotas. This means that an examination of female representation among society’s top positions can serve as an indirect measurement of the policy feedback mechanism. Regarding resources, childcare expenditures are a crucial political instrument for empowering women’s participation in the labor market and is one of the few areas of increased expenditure across mature welfare states (Lauri et al. 2020). They stand for defamiliarization, meaning that traditional care obligations are assigned to public institutions and are not carried out in private by mothers. Thus, it is plausible that men with neo-traditional views on the gendered division of work reject generous childcare policies. Furthermore, the majority of European far-right parties reject public childcare expenditures and advocate for mothers to care for their children at home.

The measurement of these four indicators will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter. Since insufficient quantitative research exists on gender policies and far-right voting/orientation, the reasoning behind my variable selection is only based on these first explorative grounds. In general, I expect a larger representation of women and greater gender equality in the political and socio-economic areas to provoke a cultural backlash by men, leading to more men having a far-right orientation than women. Thus, policies of female empowerment (e.g., public childcare) especially provoke some of the non-targeted men to backlash against this cultural turn and to adopt a far-right orientation. Based on this argumentation, I formulate the following four hypotheses:

H1a.

The higher the female representation in the political sphere (here: women in parliament), the greater the gender gap in far-right orientation.

H1b.

The more equal the resources in the political sphere (here: childcare expenditures), the greater the gender gap in far-right orientation.

H2a.

The higher the female representation in the socio-economic sphere (here: women on boards), the greater the gender gap in far-right orientation.

H2b.

The more equal the resources in the socio-economic sphere (here: gender wage gap), the greater the gender gap in far-right orientation.

While these hypotheses are correlative in nature and focus on explaining the cross-country gender gap in far-right orientation, I also aim to test the cultural backlash mechanism by analyzing individual attitudes. The moderating factor of the theoretical framework are socially conservative attitudes that drive men rather than women toward a far-right orientation. Hence, I argue that the promotion of women in the political and socio-economic spheres strengthen a cultural backlash, as expressed in socially conservative gender attitudes that inter alia increase the likelihood of a far-right orientation. The argument, grounded on socially conservative attitudes, is empirically supported by Allen and Goodman (2021), who find that progressive attitudes toward gay equality are positively correlated with women voting for the far-right, but negatively correlated with men voting for the far-right. Thus, social conservativism—if measured on the basis of attitudes toward homosexuality—is associated with female far-right voters, but not with male far-right voters. I, therefore, argue that the effect of gender equality policies on the gender gap in far-right voting is moderated by socially conservative attitudes. Social conservatism represents, here, the silent revolution against the post-materialist turn; hence, the moderation effect is used to test the mechanism more robustly. Furthermore, far-right parties justify their family and gender policy proposals with socially conservative views on women’s role in society. While Hypotheses 1a to 2b especially test the framework of policy feedback, Hypothesis 3 explores the cultural backlash mechanism.

H3.

Socially conservative gender attitudes positively moderate the effect of the political and socio-economic promotion of women on the gender gap in far-right orientation; i.e., socially conservative attitudes strengthen the relationship between the promotion of women and the gender gap in far-right orientation.

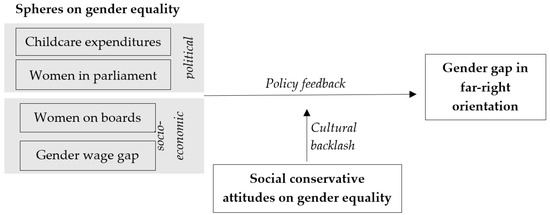

This paper therefore introduces two theoretical innovations for policy feedback theory by formulating hypotheses on the political orientation of groups not targeted by specific policies and by combining the theories of policy feedback and cultural backlash. The theoretical argument of the study is summarized in Figure 1. The four studied spheres of gender equality are displayed on the left-hand side, divided into a political and a socio-economic area. As explanatory variables, they are considered to have a positive relationship with the outcome variable: the gender gap in far-right orientation. The relationship here is a feedback mechanism, meaning that policies and corporate goals influence the preferences of both sexes differently. This connection at the macro-level is linked to a moderation effect at the individual level, meaning that socially conservative attitudes on gender equality influence the effect of policies on female promotion on the gender gap in far-right orientation. Next, I describe the empirical identification strategy that I use to test these hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

4. Empirical Strategy: Data and Methods

To explore the hypotheses about the gender gap in far-right orientation in European countries, I required data for a number of countries on: (1) attitudes toward gender equality; (2) individual-level covariates, such as education and political orientation; and (3) levels of the promotion of women in different fields. Such data must, therefore, capture people living in countries with different levels of gender-equality representation, different resources, and varying gender gaps in far-right orientation.

Since there is no single dataset that combines (1) to (3), the study relies on the European Values Studies (EVS) from 2017 and 2008 (EVS 2019, 2010), which has many items on attitudes toward gender equality. The individual-level survey data from the EVS are combined with the OECD Social Expenditure Aggregated Dataset on female seats on boards and the gender wage gap (OECD 2019b), the Comparative Welfare States Data Set on childcare expenditures (Brady et al. 2020), and the World Bank Gender Statistics for women in parliament for the respective years. Consequently, the combined dataset includes country-level data from three datasets and individual-level data from the EVS. While egalitarian attitudes and political orientation were measured in 2008 and 2017, respectively, the independent, macro-level variables are lagged by at least a year to produce a temporal sequence as a condition for causality. Since data availability is not sufficient for a single year, I look at some countries only in 2008, others only in 2017, and some countries for both years. The values for the latter countries (2008 and 2017) are combined to avoid overrepresentation. The studied 32 European countries are presented in Appendix A Table A1.

The empirical analysis is based on the dependent variable “gender gap in far-right political orientation” from the EVS. The outcome variable compares men and women with a far-right political orientation. Thus, men with a political orientation of eight to ten—on a scale from one to ten—are coded as one, while women with the same ideological self-placement are coded as zero (see also Pickard et al. 2022). I use far-right political orientation instead of far-right voting for the following reasons: first, far-right parties have a varying portfolio regarding gender and family issues (Akkerman 2015; De Lange and Mügge 2015), which could bias the results if used as the dependent variable. Even though far-right parties share a conservative gender agenda, some of them debate the status of women and gender equality in light of rising immigration (e.g., the Danish People’s Party (DF)), while others clearly promote women to be housekeepers and to stay away from the labor market (e.g., Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ)). This ideological heterogeneity, as well as endogenous factors, such as the popularity of party leaders, could be an invalid measuring instrument and dilute the theoretical concept behind it. Far-right political orientation, in contrast, is a broader item measuring the recent far-right ideological preferences of respondents. The left–right scale organizes the values and beliefs of individuals, and is thus a good aggregated indicator for measuring far-right ideology (Verkuyten et al. 2022). Second, cultural backlash is not only expressed by voting but by a shift in attitudes and values. Some individuals might not have voted, and their answers would become irrelevant if I had opted for voting behavior. Nevertheless, political orientation and voting behavior are strongly correlated. As Jou and Dalton (2017) find, the majority of voters can locate themselves on a left–right scale and link their voting decisions to it. Voters are able to identify political parties on a left–right scale and the political orientation on a left–right scale is an important guide for voting choices. In Appendix A Table A6, I estimated the models with far-right voting as the dependent variable, showing that the results do not differ crucially.

The key independent variables on the political and socio-economic promotion of women are presented in Table 1. Regarding the political sphere, I use the share of women in parliament for the category “representation”. Several studies have found that the number of female parliamentarians positively influences the public image of women as political leaders as well as diversifies the legislative agenda (e.g., O’Brien and Piscopo 2018). Moreover, a higher female representation in parliament increases the level of policymaking on women’s issues (Devlin and Elgie 2008). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) established a gender equality index in the 1990s with the representation of women in parliament as the key indicator for measuring the political opportunities of women. In general, this indicator is well-established in gender research as a measurement of the political representation, participation, and decision-making power of women (Plantenga et al. 2009), which is why I also use it here. Table A4 shows inter alia the distribution of this independent variable. While Ukraine has the highest gender gap regarding women in parliament, with only 8.2 percent in 2008, we find the lowest gender gap in Iceland, with 47.6 percent in 2017. The mean value is 26.9 percent; however, the share of women in parliament—averaged across all countries—increased by 11 percentage points from 2008 to 2017. Next, childcare expenditures are used for the category “resources” (policy outcomes). Childcare policies are at the front of the political promotion of women in order to increase female labor participation. Even former male breadwinner countries, such as Germany or Austria, have increased their childcare expenditures tremendously in the last years and even established a formal right to public childcare access. Since public childcare symbolizes a departure from mothers staying at home and doing care work, scholars regard it as a good indicator of defamiliarization and the cultural backlash. Lewis (2008) argues that family policies represent an area in which competing values concerning the social order of society are in focus, and childcare policies are critical to understanding the role of men and women in both societies and families (Fleckenstein 2010). I measure childcare expenditures as share of GDP, including early childhood education and care as well as formal day-care services and pre-primary education services. The average expenditure on childcare in the sample is 0.696 percent, with the lowest value in Latvia in 2008 (0.09 percent) and the highest value in Iceland in 2017 (1.8 percent). The average expenditure increased from 0.48 percent in 2008 to 0.81 percent in 2017. The third independent variable used in this analysis to measure the representation of women in professional life is the share of women on boards. Female board representation not only improves decision-making (Nielsen and Huse 2010) and the governance and effectiveness of organizations (Halliday et al. 2021), but it is also important for the broader public since it creates role models and increases the professional visibility of women. Studies found that in countries with greater gender equality, women enjoy more legitimacy on boards and suffer less sexism and gender bias (Glick et al. 2004; Santacreu-Vasut et al. 2014). For all these reasons, the inclusion of women on boards has gained public and scholarly interest, and several countries—for example, Norway, France, Belgium, Italy, and Germany—have introduced gender quotas with sanctions for non-compliance. Other countries have formulated policies without sanctions (e.g., the Netherlands or Iceland) or only quotas for state-owned companies (e.g., Austria, Poland, and Slovenia). I hypothesize that the varying representation of women on boards influences the cultural backlash of some men who turn to the far-right. In the present sample, an average of 20.63 percent of board members are female. The lowest percentage is found in Luxembourg, with 3.5 percent of women on boards in 2008. The highest share of women is found in Iceland, where 43.5 percent of board members are female. The average number of women has more than doubled between 2008 and 2017: while 12.84 percent of board members were women in 2008, the share increased to 27.85 percent in 2017. The last independent variable in the present analysis is the wage gap, which I use to measure resources in the socio-economic sphere. Even though the gender wage gap has decreased since the 1970s and female labor participation has increased, a wage gap persists in nearly every European country despite the enactment of anti-discrimination policies. Women in the EU earned, on average, 14.1 percent less per hour than men in 2019 (EU27 data). Reasons are the employment in different sectors, disrupted careers path due to family obligations, or the glass ceiling. The argument here is that the lower the wage gap, the more integrated are women in the labor market at different positions and sectors and the more they stand in direct competition with men. The latter might evoke feelings of aggrieved entitlement among men, which is why I use the gender wage gap as the fourth independent variable. In the present sample, the highest gender wage gap is in Cyprus in 2008 (30.27 percent) and the lowest—interestingly—is in Hungary in 2008 (2.2 percent). The average gender wage gap is 13.43 percent, a minor decrease from the 14.17 percent in 2008 to 13.13 percent in 2017. It is important to note that high values in this variable are associated with low gender equality, and the coding is, therefore, the other way round than for the other three variables.

To find out whether this silent revolution for female rights sparked authoritarian attitudes among social conservatives, I look at attitudes toward gender equality, focusing on the Eurobarometer item: “a man’s job is to earn money, a woman’s job is to look after the home and family”. The attitude is dichotomized into “agree” and “disagree”. This item represents normative ideas about the social role of women and is used in many surveys (e.g., ISSP, EVS), making it a valid and frequently used item for measuring socially conservative attitudes.

At the individual level, I control for economic deprivation, which is measured as the binary item of having experienced unemployment in the last 12 months. I expect unemployment to increase the likelihood of a far-right orientation, especially among men who expect themselves to be in employment according to their normative self-image. This variable also maps well onto the relative/positional deprivation some men feel when comparing themselves to immigrants or women in work (Burgoon et al. 2019). I also control for the attitude “immigrants take jobs away”, which is measured using a 10-point Likert scale, to include the most prominent explanation for far-right orientation (see also Arzheimer 2009). I also include education levels and age as controls, since Norris and Inglehart (2019) find (cultural) grievances due to the post-materialist revolution to be especially prevalent among the elderly and the low-educated.

The survey year is included in the model to capture time effects. Finally, I control for the size of the far-right parties in the respective countries to find out whether political parties’ extremist images and their discriminatory tendencies influence the relationship between X and Y. Since larger far-right parties need to appeal to a greater electorate, their positions should be more moderate in contrast to smaller far-right parties with specific grievances (empirical evidence is found in Donovan 2022). Thus, the argument here is that the smaller the party, the larger the gender gap. To consider the limited degrees of freedom, I insert no further variables at the country level, even though further explanations are theoretically plausible. Nevertheless, I report the results for a region dummy (Eastern vs. Western Europe) in Appendix A Table A5, as the history and programs of far-right parties differ between both regions. A possible result, therefore, is that the different spheres of gender equality have no effect on the gender gap in far-right orientation when controlling for regional differences. The description, data sources, measurements, and distribution of the variables can be found in Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3.

I estimate mixed-effects logit regressions to predict multilevel models for the binary outcome variable on political orientation. By combining fixed and random effects, I recognize correlations between respondents from countries included on two occasions (2008 and 2017). Since I am interested in why more men than women have a far-right orientation, logit regressions are the most appropriate. For predictions based on the regression, I report the fixed portion of the model only to facilitate interpretation.

5. Results

I structure the empirical analysis chronologically according to my hypotheses. To test Hypotheses 1a to 2b, that is, whether the political and socio-economic promotion of women influences the gender gap in far-right orientation, I estimate multilevel regressions for the four independent variables. With this first analysis, I aim to find out whether a silent revolution towards gender equality in politics and professional life has led men in particular to develop a far-right political orientation. Table 2 illustrates the findings of six models in a regression table. The results are based on 25 to 32 European countries depending on data availability.2 The number of observations ranges from 4194 to 5825, subsuming all respondents with a far-right political orientation. Model 1 is the baseline model with only individual-level variables. In Model 2, the size of the far-right party is included as a control. Model 3 reports the results for women in parliament (item for political representation), Model 4 the results for childcare expenditures (item for political resources), Model 5 the results for women on boards (item for socio-economic representation), and Model 6 the gender wage gap (item for socio-economic resources). Relying on Hypotheses 1a to 2b, which are based on the theory of relative male deprivation, I expect a higher degree of representation and more equality in resources to translate to a higher gender gap in far-right orientation.

Table 2.

Mixed effects logit regression to explain the gender gap in far-right orientation.

Starting with the individual-level controls, I find a negative statistically significant effect for age, which is robust in all six models. Thus, the younger the male respondent, the higher his likelihood of having a far-right orientation. This supports former findings in the literature that young men are more attracted to extreme views and political parties. Much far-right activism “is constructed as a masculine military-like activity” (Scrinzi 2014 in Blee 2020), which is why young men especially are attracted (Mierina and Koroleva 2015). Young women, in contrast, are among the most unlikely socio-demographic group voting for the far-right/having a far-right political orientation. Education is significant in all six models, meaning that a higher education level among men is associated with a far-right orientation, which is surprising considering that former studies have found men with a lower level of education to be likelier to favor the far-right (e.g., Givens 2004). I find negative significant results for unemployment experience. Here, experiences of unemployment in the last 12 months increases the likelihood among women of having a far-right political orientation. The last control variable at the individual level is the attitude “immigrants take jobs away”, for which I find no support. Thus, men and women who have a far-right political orientation do not differ in their xenophobic attitudes. This supports former research, finding that men and women do not have different attitudes on immigration issues (e.g., Harteveld et al. 2015). With regard to the size of the far-right party in the countries in question, I find no significant effect.

Model 3 tests Hypothesis 1a on the effect of women in parliament on the gender gap in far-right orientation. We find a positive significant effect for the share of women in parliament at the 0.1 percent level. Thus, a higher female political representation in a country is associated with men being more likely to have a far-right orientation. This supports my expectations, indicating that female politicians might symbolize a taking-over of a male sphere of influence. Model 4 shows the test results for Hypothesis 1b on whether childcare expenditure increases the gender gap in political orientation. The coefficient is significant and positive at the 1 percent level, meaning higher childcare expenditures are associated with a higher gender gap in far-right orientation ceteris paribus. Looking at the representation of women in the socio-economic sphere (Model 5), I find support for Hypothesis 2a. The coefficient for women on boards is positive and statistically significant, indicating that a higher female representation in leadership positions in professional life might lead to a cultural backlash by men who feel threatened by the fact that women are also able and entitled to hold such positions. Finally, Model 6 reports the test for Hypothesis 2b on the effect of the gender wage gap on the gender gap in far-right orientation, recalling that a low gender wage gap should be associated with more men having a far-right orientation. As expected, the coefficient is negative, but not significant. Thus, I must reject Hypothesis 2b. All in all, I find support for the representation-hypotheses and partly for the resources-hypotheses, based on the present data. This might indicate that a cultural backlash is primarily directed against “visible” actions in public life. The gender wage gap might require a certain political knowledge and might be too obscure to influence attitudes. The share of women in parliament and on boards, in contrast, is visible to everyone and threatening for some. I will discuss these mixed results in the discussion chapter.

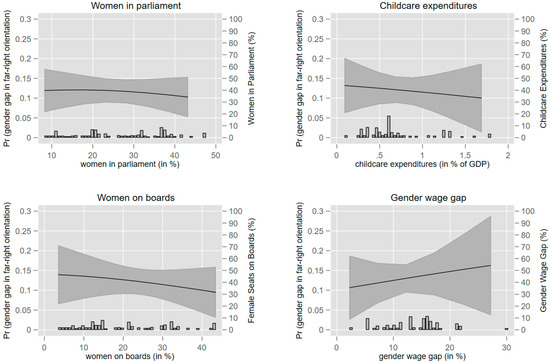

Next, I test the second research question on whether attitudes toward gender equality moderate the effect of the political and socio-economic promotion of women on the gender gap in far-right political orientation. For the associated Hypothesis 3, I present in Figure 2 average marginal effect plots for the effect of the different independent variables moderated by the attitude: “A man’s job is to earn money, a woman’s job is to look after the home and family”. Graphical analyses are more suited to interpreting the interaction term in nonlinear models than is looking at the coefficients of the interaction term in tables (Greene 2010). The distribution of the independent variables is displayed with bar charts.

Figure 2.

Average marginal effects of the gendered division of work on the gender gap in far-right orientation. Own illustration based on the European Values Study 2008 and 2017, the OECD Social Expenditure Aggregated Dataset, the Comparative Welfare States Data Set, and World Bank Gender Statistics. 95% confidence intervals, fixed portion only.

Figure 2 is divided into four panels that estimate the moderating effect of socially conservative attitudes on the relationship between the political and socio-economic promotion of women on the gender gap in far-right orientation. While the upper two panels show the political promotion of women (women in parliament and childcare expenditure), the lower two present the socio-economic promotion of women (women on boards and gender wage gap). I find a positive moderating effect for all four spheres of gender equality. Thus, the effect of women in parliament, women on boards, childcare expenditure, and the gender wage gap on the far-right gender gap is moderated by the attitude toward a gendered division of work. Nevertheless, the effect size is very low, which is partly due to the small sample size and multilevel modeling. The moderating effect of socially conservative attitudes becomes even smaller as the values for the promotion of women increase. An exception is the gender wage gap: the higher the gender wage gap, the more greatly socially conservative attitudes impact the gender gap in far-right orientation. This is contrary to my expectations. Even though socially conservative attitudes seem to be associated with the gender gap in far-right orientation, I find low support for the moderation hypothesis. To sum up, the cross-level interactions suggest that socially conservative attitudes are positively correlated with the relationship under investigation; but, due to the large confidence intervals, a very flat to negative slope, and small effect sizes, I am not able to confirm Hypothesis 3. In the next section, I discuss the results of this hypothesis and conduct robustness checks for alternative attitudes to gender.

6. Discussion

As this paper is an alternative, or at least complementary, explanation of previous studies, it is important to test them rigorously. In the following, I present additional results that are in the Appendix A and which complement the results presented so far.

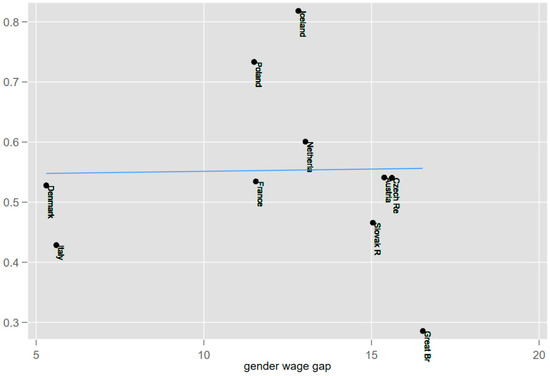

The first possible point of criticism of the present study is its conceptualization of the outcome variable, as I decided to use political orientation instead of voting behavior. To test the models with the gender gap in far-right voting, I report in Appendix A Table A5 the same estimation of a gender gap in far-right voting as a dependent variable. In addition, I present scatterplots to clarify the relationship between the four spheres of gender equality and far-right voting behavior, since the number of observations is small for Table A6. Figure A1 are based on the EVS 2017 and report surveyed gender gaps in the respective countries on far-right voting. Values above 0.5 imply that more men vote for far-right parties than women. The figure essentially supports the empirical results presented above on far-right orientation. I find a slightly positive, significant relationship for X, meaning that the gender gap in far-right voting increases with a higher share of women in parliament and on boards, and with higher childcare expenditure. I find no support for the gender wage gap. Regarding the multilevel model in Table A6, I find support for women in parliament and women on boards, but not for the resources—Hypotheses 1b and 2b. This might indicate that especially the representation of women in parliament and on boards has a policy-feedback effect, for it increases the relative deprivation of men regarding gender equality and provokes a cultural backlash expressed as a shift in political orientation. Sanbonmatsu (2008) expects this backlash to manifest itself in descriptive representation in the U.S.A., where officeholding is also often male-dominated and women leaders are seen to violate traditional female stereotypes. Even if the elected women do not pursue women’s policies or advocate for women in the company, their presence might symbolize that non-male interests and traits are gaining significance. Others (e.g., Haider-Markel 2007) assume that backlash also results from other social and political victories of women, not only descriptive representation. In this paper, I find more robust evidence for the former theory, which indicates that backlash mainly operates via abstract, subjective, and socially constructed mechanisms. The actual, “resources”-based (here: wage equality and childcare) promotion of women is only partly associated with a cultural backlash. Childcare expenditure is significant for the gender gap in far-right orientation, but not in voting, while the gender wage gap is insignificant for both dependent variables.

An alternative explanation for the relationship between gender equality measures and the gender gap in far-right orientation would be that there is a certain turning point in gender equality policies that is associated with an “enough is enough” mentality among some men. If such a turning point were to exist, the results would show an exponential function where the effect on the gender gap is low until a certain degree of gender equality is reached, at which point the relationship increases tremendously. Thus, the model would only be valid for countries at the upper end of the distribution. Such a relationship is rejected in light of the present data, which, in addition, can be seen in Figure A1.

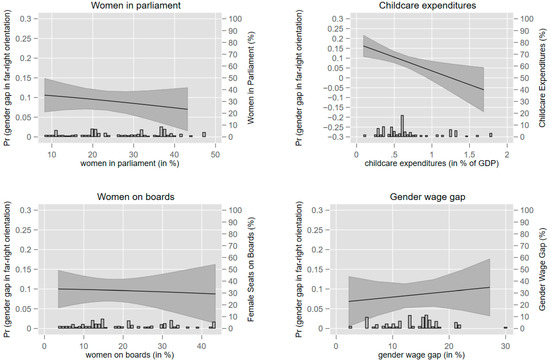

Another possible point of criticism is my choice of attitude toward gender equality, which might appear random. For this reason, I also calculated average marginal effects for another item on gender equality, more precisely, the item: “If jobs are scarce, men should be preferred.” The results in Figure A2 show a distribution comparable to the one for the gendered division of work (item: “A man’s job is to earn money, a woman’s job is to look after home and children”). I find a positive effect for all moderation effects, except for childcare expenditure. However, the slope is also very flat and/or negative for women in parliament, the gender wage gap, and women on boards. This socially conservative attitude also seems to be associated with the gender gap in far-right orientation, even though the moderation effect is not as large as expected. To summarize, the presented causal mechanism for the gendered division of work needs to be tested with additional data and methods (e.g., process-tracing or quasi-experimental), even though I find some evidence for how the cultural backlash operates.

7. Conclusions

“The Interwar generation of noncollege educated white men—until recently the politically and socially dominant group in Western cultures—has passed a tipping point at which their hegemonic status, power, and privilege are fading. Their value profile makes them potential supporters for parties promising to restore national sovereignty” (Norris and Inglehart 2019, p. 16).

This thesis on cultural backlash offers many points for conceptual and empirical investigations. While the so-called angry white men are a well-known concept in the U.S.—where a survey found that 53 percent of Republicans think men are punished just for being men and that 65 percent of Republicans think that society as a whole has become too soft and feminine (PRRI 2019)—this paper analyzes the phenomena in European countries. For this purpose, I combined cultural backlash theory with policy feedback to explain the tendency of men to be more attracted than women to a far-right political orientation. More precisely, I asked whether different spheres of gender equality are associated with the gender gap in far-right political orientation and whether attitudes toward gender equality moderate this relationship. To this end, I presented a new theoretical approach by bringing together self-undermining policy feedback effects with the relative deprivation of formerly privileged groups, reasoning that this combination results in cultural backlash. I argued that the strong policy focus on integrating mothers into the labor market, increasing the share of women in leadership positions, and aligning wages have led to an increase in the cultural relative deprivation of those men who long for the old benefits and privileges. I examined this relationship using mixed logistic multilevel regressions based on the European Values Study from 2008 and 2017 (EVS 2019, 2010) and various macro-level datasets for (at least) 25 European countries. I find a very robust effect for the representation of women, meaning that a higher share of women in parliament and on boards is associated with a higher gender gap in far-right orientation. Childcare expenditure is also related to this gender gap, but not to the gap in far-right voting. I had to reject my expectations regarding the gender wage gap, which is not significantly related to a varying support among men and women for the far-right. All in all, this demonstrates that the gender gap not necessarily results from a different socialization of men, as previous studies argued (e.g., Spierings and Zaslove 2017), but that a silent revolution toward gender equality also play a role here. Nevertheless, the causal mechanism grounded on socially conservative attitudes (see moderation effect in Hypothesis 3) is not supported empirically, so I invite further investigations into this relationship, including through the use of different methods as process tracing or structural equation modeling. The paper also gives some potential explanations for why the gender gap in far-right orientation is high in egalitarian Northern societies. The strong promotion of women here, especially via descriptive representation, might threaten (some) men who were formerly entitled to these positions. This is also supported by the additional regressions with regional dummies, as I found positive significant effects for Western Europe in all models. Future studies could explore this more deeply by not only distinguishing between Western and Eastern Europe, but also by looking at country-specific family policy patterns, and thus identifying context-specific influences. To sum up, the paper demonstrates the importance of gender equality policies on support for far-right parties, and more specifically on the gender gap in far-right orientation. It achieved this by analyzing “gender roles and family politics [that] are issues through which populist radical-right parties can ‘showcase the core elements of their ideology’” (Fangen and Lichtenberg 2021, p. 91).

Despite these theoretical and empirical innovations, there are some points for improvement and further research. First, as in similar studies, it was difficult to control for a social desirability bias that is especially strong for women, and it was not possible to control for prejudice. However, the EVS is a mixed-mode survey that combines web and face-to-face interviews and has a comparably low prevalence of social desirability (Holbrook et al. 2003; Kreuter et al. 2008). Future research should nevertheless find strategies to test the social desirability effect (Dalton and Ortegren 2011), which is, however, not plausible considering most of the prominent cross-national survey datasets. Besides, the empirical identification strategy here is based on cross-sectional data. Longitudinal data would be needed to test the policy feedback effect more robustly. Since quotas, childcare expenditure, and similar policies in the corporate realm have evolved over different timespans in the European countries, which often have a different redistributive profile, a longitudinal design could help to uncover the causal mechanism. Further studies should also examine policies on migration to compare the effect sizes of the promotion of different outgroups on the gender gap. It could be that the outgroup is secondary: as long as the pivotal interests of former privileged groups are not represented in politics, policies, and corporate goals, the promotion of disadvantaged groups—be they migrants or women—might evoke a cultural backlash among formerly advantaged groups. Another avenue for future research would be to use case studies that provide more precise evidence on the self-undermining feedback effect for formerly privileged groups that are not targeted with the policy. Furthermore, studies looking at the supply-side—thus, how far-right parties engage in legislative debates (see, for instance, Tosun and Debus 2021) on gender equality and how they vote on core issues concerning the promotion of women—could further improve the empirical evidence. The present study just suggests that this type of policy feedback might exist, but the data basis is not sufficient to prove it.

With the present article, I have shown that multilevel theorizing and modeling can be an effective approach to gaining a deeper understanding of the gender gap in far-right orientation. I have also expanded the theoretical uses of the policy feedback approach and cultural backlash theory by combining them to explain the gender gap in political orientation. I am aware that pessimistic policy conclusions can be drawn on the basis of this study. However, I would like to point out that the majority of men (in this sample 72 percent) supports gender equality.

Funding

For the article processing charges, I acknowledge financial support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft within the funding program “Open Access Publikationskosten“ as well as by Heidelberg University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Brady, David, Evelyne Huber, and John D. Stephens 2020. Comparative Welfare States Data Set, University of North Carolina and WZB Berlin Social Science Center. EVS. 2019. European Values Study 2017. GESIS Data Archive. Cologne, ZA7500 Version 2.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13314. EVS. 2010. European Values Study 2008. GESIS Data Archive. Cologne, ZA4800, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.10188, (OECD 2019b). Social Expenditure—Aggregated Data. Available at: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SOCX_AGG (accessed on 11 July 2022). World Bank (2020) Gender Stats—Database for Gender Statistics. 1960–2020. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=gender-statistics (accessed on 20 October 2020).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jale Tosun, participants of the ECPR 2019 conference, participants at the IPW colloquium and the two reviewers of the paper for their helpful and supportive comments. Another big thanks goes to Laurence Crumbie for peer reviewing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sample.

Table A1.

Sample.

| Country | 2008 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | x | x |

| Bulgaria | x | x |

| Croatia | x | x |

| Czech Republic | x | x |

| Georgia | x | x |

| Germany | x | x |

| Iceland | x | x |

| Netherlands | x | x |

| Poland | x | x |

| Slovak Republic | x | x |

| Slovenia | x | x |

| Spain | x | x |

| Estonia | x | x |

| France | x | x |

| Hungary | x | x |

| Italy | x | x |

| Lithuania | x | x |

| Sweden | x | x |

| Great Britain | x | x |

| Finland | x | x |

| Denmark | x | x |

| Switzerland | x | x |

| Norway | x | x |

| Belgium | x | |

| Cyprus | x | |

| Greece | x | |

| Ireland | x | |

| Latvia | x | |

| Luxembourg | x | |

| Montenegro | x | |

| Portugal | x | |

| Ukraine | x |

Table A2.

Variables.

Table A2.

Variables.

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Political orientation | Left-right orientation on a scale from 1–10, binary coding (1–7 = 0; 8–10 = 1) | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| Far-right voting | Voting behavior on a left-right scale for political parties, binary coding (1–7 = 0; 9–10 = 1) | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| Age | In years | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| Education level | Recoding of highest education level attained (basic, middle, high) | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| Unemployed | “During the last five years, have you experienced a continuous period of unemployment longer than 3 months?”, binary coding | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| “Immigrants take jobs away” | “Immigrants take jobs away from natives in a country”, 10-point Likert scale | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| “If jobs are scarce, men should be preferred” | “When jobs are scarce, men have more right to a job than women”, originally 5-point Likert scale, coded binary | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| Gendered division of work | “A man’s job is to earn money; a woman’s job is to look after the home and family”, originally 4-point Likert scale, coded binary | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| Size of the far-right party | In %, expert classification | Political Data Yearbook and Popul´List (2015–2018, depending on the year of parliamentary elections) |

| Women in parliament | Proportion of seats held by women in national parliaments (in %) | World Bank Gender Statistics (2016/17 and 2006) |

| Childcare expendi-ture | Public expenditure on day-care/home-help service provision, as a percentage of GDP (in %) | Comparative Welfare State Dataset/ OECD Family expenditures (2006/7 and 2015/6) |

| Women on boards | Female share of seats on boards of the largest publicly listed companies (in %) | OECD Statistics on Gender Equality (2010 and 2017) |

| Gender wage gap | Difference between median earnings (in %) | OECD Statistics on Gender Equality (2006/08 and 2017/2018) |

| Year | 2008 and 2017; binary coding | European Values Study (2017 and 2008) |

| Region | Western and Eastern Europe; binary coding. Eastern Europe contains CEE countries and Croatia, Georgia, Montenegro, and Ukraine. |

Table A3.

Descriptive Statistics.

Table A3.

Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable | Observations | Min. | Max. | Mean (Std. Dv.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender gap in far-right orientation (0 = female, 1 = male) | 13,363 | 0 | 1 | 0.50 (0.49) |

| Far right voting by sex (0 = female, 1 = male) | 5763 | 0 | 1 | 0.51 (0.49) |

| Age (in years) | 90,917 | 16 | 99 | 39.47 (17.94) |

| Education level (low, middle, high) | 90,405 | 1 | 3 | 2.04 (0.73) |

| Unemployed | 89,059 | 0 | 1 | 0.20 (0.40) |

| “Immigrants take jobs away” | 86,154 | 1 | 10 | 5.40 (2.93) |

| “If jobs scarce, men should be preferred” | 76,974 | 0 | 1 | 0.18 (0.38) |

| Gendered division of work (women care for home, men earn money) | 40,408 | 0 | 1 | 0.25 (0.43) |

| Size of far-right party | 84,624 | 0 | 65.7 | 12.29 (12.24) |

| Women in parliament | 91,341 | 8.2 | 47.6 | 26.91 (10.58) |

| Childcare expenditure (% of GDP) | 76,051 | 0.09 | 1.8 | 0.69 (0.39) |

| Women on boards | 76,279 | 3.5 | 43.5 | 20.63 (11.09) |

| Gender wage gap | 73,298 | 2.22 | 30.27 | 13.43 (5.14) |

Table A4.

Distribution of independent variables by country.

Table A4.

Distribution of independent variables by country.

| Women in Parliament | Female Seats in Boards | Childcare Expenditure | Wage Gap | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 32.8 (2008) 30.6 (2017) | 8.7 (2008) 19.2 (2017) | 0.31 (2008) 0.649 (2017) | 20.92 (2008) 15.38 (2017) |

| Bulgaria | 21.7 (2008) 20.4 (2017) | - - | - - | - - |

| Croatia | 20.9 (2008) 12.6 (2017) | - - | - - | - - |

| Czech Republic | 15.5 (2008) 20 (2017) | 12.2 (2008) 14.5 (2017) | 0.3 (2017) 0.44 (2017) | 17.87 (2008) 17.6 (2017) |

| Georgia | 9.4 (2008) 11.3 (2017) | - - | - - | - - |

| Germany | 31.6 (2008) 36.5 (2017) | 12.6 (2008) 31.9 (2017) | 0.37 (2008) 0.6 (2017) | 16.74 (2008) 16.19 (2017) |

| Iceland | 33.3 (2008) 47.6 (2017) | 15.8 (2008) 43.5 (2017) | 1.46 (2008) 1.8 (2017) | 21.72 (2008) 12.82 (2017) |

| Netherlands | 39.3 (2008) 37.3 (2017) | 14.9 (2008) 29.5 (2017) | 0.67 (2008) 0.6 (2017) | 16.01 (2008) 13.03 (2017) |

| Poland | 20.4 (2008) 27.4 (2017) | 11.6 (2008) 20.1 (2017) | 0.28 (2008) 0.61 (2017) | 12.99 (2008) 11.5 (2017) |

| Slovak Republic | 19.3 (2008) 20 (2017) | 21.6 (2008) 15.1 (2017) | 0.37 (2008) 0.5 (2017) | 16.44 (2008) 15.04 (2017) |

| Slovenia | 12.2 (2008) 36.7 (2017) | 9.8 (2008) 22.6 (2017) | 0.47 (2008) 0.49 (2017) | 7.13 (2008) - |

| Spain | 36.6 (2008) 39.1 (2017) | 9.5 (2008) 22 (2017) | 0.45 (2008) 0.5 (2017) | 13.53 (2008) - |

| Estonia | 20.8 (2008) 23.8 (2017) | 7 (2008) 7.4 (2017) | 0.26 (2008) 0.76 (2017) | - 17.32 (2017) |

| France | 18.2 (2008) 26.2 (2017) | 12.3 (2008) 43.4 (2017) | 1.06 (2008) 1.32 (2017) | 9.14 (2008) 11.55 (2017) |

| Hungary | 11.1 (2008) 10.1 (2017) | 13.6 (2008) 14.5 (2017) | 0.62 (2008) 0.73 (2017) | 2.22 (2008) 5.32 (2017) |

| Italy | 17.3 (2008) 31 (2017) | 4.5 (2008) 34 (2017) | 0.52 (2008) 0.56 (2017) | 10.19 (2008) 5.6 (2017) |

| Lithuania | 22.7 (2008) 21.3 (2017) | 13.1 (2008) 14.3 (2017) | 0.61 (2008) 0.79 (2017) | 15.95 (2008) - |

| Sweden | 47 (2008) 43.6 (2017) | 26.4 (2008) 36.3 (2017) | 1.32 (2008) 1.6 (2017) | 10.59 (2008) 7.35 (2017) |

| Great Britain | 19.5 (2008) 29.6 (2017) | 13.3 (2008) 27.2 (2017) | 0.73 (2008) 0.65 (2017) | 21.86 (2008) 16.53 (2017) |

| Finland | 41.5 (2008) 41.5 (2017) | 25.9 (2008) 32.8 (2017) | 0.87 (2008) 1.13 (2017) | 21.23 (2008) 17.72 (2017) |

| Denmark | 38 (2008) 37.4 (2017) | 17.7 (2008) 30.3 (2017) | 1.24 (2008) 1.23 (2017) | 10.18 (2008) 5.3 (2017) |

| Switzerland | 28.5 (2008) 32 (2017) | - 21.3 (2017) | 0.287 (2008) 0.454 (2017) | 21.3 (2008) 15.1 (2017) |

| Norway | 36.1 (2008) 40 (2017) | 38.9 (2008) 42.1 (2017) | 0.93 (2008) 1.33 (2017) | 9.57 (2008) 6.39 (2017) |

| Belgium | 35.3 (2008) | 10.5 (2008) | 0.61 (2008) | 8.92 (2008) |

| Cyprus | 14.3 (2008) | - | - | 30.27 (2008) |

| Greece | 14.7 (2008) | 6.2 (2008) | - | 17.73 (2008) |

| Ireland | 13.3 (2008) | 8.4 (2008) | 0.3 (2008) | 18.04 (2008) |

| Latvia | 20 (2008) | 23.5 (2008) | 0.09 (2008) | 10.99 (2008) |

| Luxembourg | 23.3 (2008) | 3.5 (2008) | 0.36 (2008) | 8.2 (2008) |

| Montenegro | 11.1 (2008) | - | - | - |

| Portugal | 28.3 (2008) | 5.4 (2008) | 0.37 (2008) | 12.81 (2008) |

| Ukraine | 8.2 (2008) | - | - | - |

Figure A1.

Scatterplot on the relationship of gender wage gap and the gender gap in far-right voting.

Table A5.

Mixed-effects logit regression to explain the gender gap in far-right orientation with region as control.

Table A5.

Mixed-effects logit regression to explain the gender gap in far-right orientation with region as control.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Gap in Far-Right Orientation | ||||||

| Age (in years) | −0.00588 *** | −0.00796 *** | −0.00696 *** | −0.00856 *** | −0.00876 *** | −0.00807 *** |

| (0.00107) | (0.00132) | (0.00124) | (0.00144) | (0.00142) | (0.00144) | |

| Education level (three categories) | 0.0510 * | 0.00606 | −0.00665 | −0.0192 | 0.00102 | 0.0129 |

| (0.0265) | (0.0323) | (0.0308) | (0.0348) | (0.0343) | (0.0352) | |

| Unemployment experience (yes = 1, no = 0) | −0.153 *** | −0.128 ** | −0.145 ** | −0.0997 | −0.102 | −0.103 |

| (0.0521) | (0.0648) | (0.0589) | (0.0725) | (0.0717) | (0.0735) | |

| “Immigrants take jobs away” (0–10) | 0.00505 | 0.00594 | 0.0103 | 0.00203 | 0.00245 | 0.00764 |

| (0.00640) | (0.00788) | (0.00731) | (0.00880) | (0.00862) | (0.00887) | |

| Size of the far-right party | −0.000171 | |||||

| (0.00232) | ||||||

| Region (0 = Eastern Europe, 1 = Western Europe) | 0.367 *** | 0.224 ** | 0.328 ** | 0.345 *** | 0.388 *** | |

| (0.125) | (0.113) | (0.136) | (0.132) | (0.146) | ||

| Women in parliament (in %) | 0.0117 *** | |||||

| (0.00417) | ||||||

| Childcare expenditure (in % of GDP) | 0.207 * | |||||

| (0.120) | ||||||

| Women on boards (in %) | 0.00527 * | |||||

| (0.00288) | ||||||

| Gender wage gap (in %) | −0.0128 | |||||

| (0.00834) | ||||||

| Constant | 0.160 | 0.113 | −0.151 | 0.127 | 0.106 | 0.255 |

| (0.107) | (0.155) | (0.149) | (0.170) | (0.168) | (0.194) | |

| Random intercept for country | −1.198 *** | −1.412 *** | −1.618 *** | −1.553 *** | −1.502 *** | −1.412 *** |

| (0.142) | (0.198) | (0.201) | (0.221) | (0.217) | (0.204) | |

| Observations | 12,430 | 8312 | 9281 | 6983 | 7232 | 7014 |

| Number of countries | 32 | 22 | 24 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

Source: own calculations based on the European Values Study 2008 and 2017, the OECD Social Expenditure Aggregated Dataset, the Comparative Welfare States Data Set, and World Bank Gender Statistics. Standard errors in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A6.

Mixed-effects logit regression to explain the gender gap in far-right voting.

Table A6.

Mixed-effects logit regression to explain the gender gap in far-right voting.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Gap in Far-Right Voting | ||||||

| Age (in years) | −0.00386 ** | −0.00406 ** | −0.00426 *** | −0.00408 ** | −0.00416 ** | −0.00395 ** |

| (0.00163) | (0.00164) | (0.00162) | (0.00166) | (0.00166) | (0.00170) | |

| Education level (three categories) | 0.0525 | 0.0581 | 0.0442 | 0.0440 | 0.0446 | 0.0543 |

| (0.0404) | (0.0408) | (0.0399) | (0.0412) | (0.0410) | (0.0420) | |

| Unemployment experience (yes = 1, no = 0) | −0.0866 | −0.0668 | −0.0627 | −0.0556 | −0.0519 | −0.0693 |

| (0.0769) | (0.0783) | (0.0767) | (0.0799) | (0.0799) | (0.0809) | |

| “Immigrants take jobs away” (0–10) | 0.000335 | 0.00324 | 0.00963 | 0.00341 | 0.00391 | 0.000840 |

| (0.0102) | (0.0103) | (0.0103) | (0.0106) | (0.0104) | (0.0107) | |

| Size of far-right party | −0.00651 * | |||||

| (0.00343) | ||||||

| Survey year | 0.0248 * | 0.0117 | 0.00699 | −0.0106 | 0.0177 | |

| (0.0128) | (0.0110) | (0.0140) | (0.0143) | (0.0139) | ||

| Women in parliament (in %) | 0.0188 *** | |||||

| (0.00306) | ||||||

| Childcare expenditure (in % of GDP) | 0.209 | |||||

| (0.129) | ||||||

| Women on boards (in %) | 0.0154 *** | |||||

| (0.00428) | ||||||

| Gender wage gap (in %) | −0.00292 | |||||

| (0.0119) | ||||||

| Constant | 0.104 | −49.77 * | −24.16 | −14.14 | 21.10 | −35.62 |

| (0.149) | (25.74) | (22.18) | (28.09) | (28.81) | (28.01) | |

| Random intercept for country | −1.639 *** | −1.670 *** | −2.893 *** | −1.693 *** | −1.994 *** | −1.761 *** |

| (0.241) | (0.254) | (0.857) | (0.253) | (0.289) | (0.272) | |

| Observations | 5421 | 5366 | 5421 | 5243 | 5224 | 5052 |

| Number of countries | 29 | 26 | 29 | 22 | 23 | 23 |

Source: own calculations based on the European Values Study 2008 and 2017, the OECD Social Expenditure Aggregated Dataset, the Comparative Welfare States Data Set, and World Bank Gender Statistics. Standard errors in parentheses, *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Figure A2.

Average marginal-effect plot of men’s preferred job selection on gender gap in far-right orientation.

Notes

| 1 | An important exception is Immerzeel et al. (2015), who attempted to explain cross-national variation through the far-right party characteristics of the outsider image and populist discourse style. However, they found no support for this theory. The present paper pursues another strategy to explain the gender gap by focusing on different spheres of gender equality. |

| 2 | I also run the analyses on the same 25 countries, finding comparable effects to the models with different sample sizes (not reported here). Since I would have lost several degrees of freedom by aligning the number of clusters across the models, I decided against using only the 25 countries as the main output table. |

References

- Akkerman, Tjitske. 2015. Gender and the radical right in Western Europe: A comparative analysis of policy agendas. Patterns of Prejudice 49: 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Trevor, and Sara W. Goodman. 2021. Individual and party-level determinants of far-right support among women in Western Europe. European Political Science Review 13: 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2009. Contextual factors and the extreme right vote in Western Europe, 1980–2002. American Journal of Political Science 53: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzheimer, Kai, and Carl Berning. 2019. How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Electoral Studies 60: 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blee, Kathleen. 2020. Where do we go from here? Positioning gender in studies of the far right. Politics, Religion& Ideology 21: 416–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, David, Evelyne Huber, and John D. Stephens. 2020. Comparative Welfare States Data Set. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina and WZB Berlin Social Science Center. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon, Brian, Sam van Noort, Matthijs Rooduijn, and Geoffrey Underhill. 2019. Positional deprivation and support for radical right and radical left parties. Economic Policy 34: 49–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busemeyer, Marius, Aurélien Abrassart, and Nezi Roula. 2019. Beyond positive and negative: New perspectives on feedback effects in public opinion on the welfare state. British Journal of Political Science 51: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovan, Margaret. 1999. Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies 47: 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2016. Gender Equality Glossary. London: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, Derek, and Marc Ortegren. 2011. Gender differences in ethics research: The importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. Journal of Business Ethics 103: 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassonneville, Ruth. 2020. Change and continuity in the ideological gender gap—A longitudinal analysis of left-right self-placement in OECD countries. European Journal of Political Research 60: 225–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lange, Sarah L., and Liza M. Mügge. 2015. Gender and right-wing populism in the Low Countries: Ideological variations across parties and time. Patterns of Prejudice 49: 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, Claire, and Robert Elgie. 2008. The effect of increased women’s representation in parliament: The case of Rwanda. Parliamentary Affairs 61: 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]