3.1. Legal Changes towards Gender Equality

After Franco’s death in 1975, a gradual process of rights recovery for the Spanish people began. This process is known as the Spanish transition to democracy. In this background, from the last decade of the 20th century to the present, different laws, aimed at achieving equal rights for women and men, have been approved. Two of these laws, which have been pioneering in the international arena, are the “Organic Law 1/2004, of December 28, of Comprehensive Protection Measures against Gender Violence” (Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de Diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género) and the “Law for the effective equality of women and men”, published on 23 March 2007. As its title indicates, Law 1/2004, of 28 December, is an organic law. In other words, it is a law that derives directly from the Spanish Constitution and serves for its better application. Both this law and the second of them, apart from promoting equality between men and women, try to alleviate and regulate the effects of gender inequality and, above all, in the case of the first of them, to prevent violence by men against women because of their feminine condition.

In this way, after the recovery of democracy in Spain, the change in the legal-social status of women has been especially significant. An example of this is the sizeable and permanent increase in the number of women enrolled in the generality of university degrees, as well as the noteworthy and continuous growth of the presence of women in the labor market, which was experienced in Spain from the first years of the arrival of democracy. So, by the end of the 1970s, 22% of adult Spanish women—still somewhat less than in Italy and Ireland—had entered the labor market. But, by 1984, this figure had risen to 33%, a level not unlike that of Italy or the Netherlands. However, women still accounted for less than a third of the whole workforce, and in some important sectors, such as banking, the figure was close to one-tenth.

Despite this, things were gradually evolving towards a better situation for in Spain. Thus, already in the mid-1970s, from the very beginning of the transition to democracy, there was a progressive spreading of feminist social attitudes and movements in this country. The discourses of these attitudes and movements tried to identify the causes of female exclusion and sought to create the bases to end it (

Fernández-Fraile 2008). All this happened in a setting that had been developing already in the last years of the Franco dictatorship, characterized by the increasing incorporation of women into the labor market, the gradual decrease in the birth rate, a boom in foreign tourism, the emigration abroad of many Spaniards, and educational and cultural expansion. As a result of all this, at the end of the 1970s, attitudes favorable to the incorporation, on an equal footing, of women into the generality of the areas of social and working life had become common in Spanish public opinion, particularly among the younger population. These Spanish social attitudes were at the same level as their equivalent in other countries of our European environment. In these circumstances, the main barrier for women to access a job was no longer public opinion but factors such as a high unemployment rate and a lack of part-time jobs.

At the educational level, women quickly reached parity with men, at least statistically. Thus, in 1983, approximately 46% of university enrollment in Spain was female, which meant that our country had the thirty-first percentage in this regard in the world, with levels of female university students similar to those of the majority of the other European countries (

Clark 1990).

Nevertheless, progress on gender equality has been slow in many ways. Thus, it took until 1987 for a ruling by the Supreme Court of Spain to consider that a rape victim did not have to prove that she had fought against her aggressor to defend herself, to verify the truth of her complaint. Until that date, when that important court case was resolved, it was generally accepted that a woman victim of rape, unlike victims of other crimes, had to show that she had put up a ‘heroic resistance’ to make it clear that she had not somehow tempted the rapist nor had otherwise encouraged him to attack her (

Clark 1990).

In any case, the progress made since the end of the Franco dictatorship in terms of equality between the sexes is evident. To a large extent, this has been possible since the beginning of the new democratic era due to the fact that the Spanish Constitution of 1978 itself establishes equality as a chief value in its article 1, paragraph 1, even affirming in article 14 that all people are equal before the law, which is why any type of discrimination based on place of birth, race, sex, religion, opinion or personal or social situation is forbidden.

The constitutional legislative framework, together with the democratization of social and political life that this has made possible, has created a very appropriate setting for Spain to have undergone key advances in terms of equality between men and women over the course of more than forty years since Franco passed away.

Although the principle of gender equality is included in national and regional plans, programs and policies that are being implemented in the democratic context, the fact is that its implementation in practice has been much more difficult (

European Institute for Gender Equality 2019). One of the events that slowed progress on gender equality was the 2008 economic crisis since, as a consequence of it, ‘austerity’ policies were implemented without a gender perspective. For instance, the budget cuts made during that crisis, in the interests of the proclaimed ‘austerity’ and cutback of public spending, affected care policies and resulted in the reabsorption of certain care tasks by families and, definitively, on the part of women.

The new government that came to power in June 2018 made it clear from the outset that gender equality policy was once again high on its agenda. In this way, the actions of this government have been characterized by a series of Spanish public policies aimed at promoting gender equality. Within the framework of these actions, plans and programs have been developed in our country that promote gender equality at the central, regional, and, to a certain extent, local levels. The main objectives of these plans have been to address gender equality in the workplace; empower women; and prevent and combat, at all levels, all forms of gender-based violence against women. Among these plans, we mention here two policies that are closely related to what we are dealing with in this paper. They are the “Royal Decree-Law 6/2019, of March 1, on urgent measures to guarantee equal treatment and opportunities between women and men in employment and occupation (

Real Decreto 2019), and the “Royal Decree 902/2020, of October 13, on equal pay between women and men (

Real Decreto 2020). Likewise, a Christmas campaign launched in December 2021 by the Spanish Ministry of Consumer Affairs can also be included within these policies aimed at achieving gender equality. Thus, with this campaign, the Ministry wants to raise awareness about the risk of reproducing sexist roles and stereotypes in childhood through the advertising of games and toys (

La Moncloa 2021b).

In addition to this, it is worth noting that, during the COVID-19 health crisis, the socialist government has launched campaigns and published different documents aimed at increasing the degree of social awareness about the situation of greater vulnerability of women. Thus, it has been pointed out that women are suffering doubly the consequences of the pandemic with an overload of health work, essential services and care (they continue to do most of the domestic work and care of dependents, paid and unpaid, also assuming a greater mental burden derived from these), greater job insecurity and poverty, and increased risk of suffering gender-based violence (

La Moncloa 2021a).

In this context, the spirit and impulse of previous laws aimed at achieving equality for women, promulgated during the socialist government of Rodríguez-Zapatero (2004–2011), have been retaken. This government promoted some of the most profound legal advances on gender equality in the post-Franco democratic period. One of the measures adopted by the Rodríguez-Zapatero administration, in line with promoting gender equality, is Order PRE/525/2005, of 7 March, approved by the Council of Ministers on 4 March of the same year. Thus, in this Order, measures to be adopted to favor gender equality were indicated, and actions were promoted to reduce inequality in the areas of employment, the company, the compatibility of work and family life, research, solidarity, sport and gender violence. Specifically, among other things, the Order promoted the hiring and promotion of women at the work level and spoke of the changes in the regulations necessary to tackle harassment and gender-based violence at work.

Within this same Council of Ministers, Order APU/526/2005, of 7 March, was also approved, which established the Plan for Gender Equality in the General State Administration. This Plan, in addition to the aforementioned, established gender parity in some administrative positions and quotas for the hiring of women in others. Likewise, in keeping with its name, the Plan aimed to study the situation of women in the General State Administration in relation to gender equality, with the aim of intervening to alleviate the inequalities that could be found.

However, the most important step towards gender equality was taken in Spain with the approval of Organic Law 3/2007 of 22 March, aimed at achieving effective equality between women and men (known as the Equality Law). This Law, which is applied at the national, regional and local levels, covers a wide range of issues, from paternity leave to a more balanced political gender representation, and establishes the duty, on the part of public bodies and companies with more than 250 employees, to develop equality plans in cooperation with workers’ representatives. The Equality Law also prescribed the creation of gender units in all ministries.

The promulgation of Organic Law 3/2007 entails the recognition that, despite full constitutional recognition of equality before the law, it has not been achieved in matters of gender. Thus, it is possible to observe a clear wage discrimination between men and women, as well as in pensions charged by both sexes and in pensions for widows. Furthermore, unemployment levels are higher among the female population, while the presence of women in positions of responsibility at all levels (political, economic, social and cultural) is lower. In addition, women are discriminated against in terms of reconciling work and family life, since most of them are the ones who assume responsibility for taking care of the home, while a significant number of men tend to ignore it. Taking this situation into account, a priority objective of the Law was to carry out normative action to combat discrimination against women based on their sex, which continued to prevail either directly or indirectly. To achieve this purpose, it was necessary to remove those obstacles and stereotypes that prevented attaining parity between men and women. In particular, the Law contemplated special consideration for the most vulnerable groups of women, namely, minorities, migrants and women with some kind of disability.

The major novelties of this Law are that it tries to prevent discriminatory behavior against women and that it plans to carry out active policies to achieve equality. Specifically, the Law envisaged intervening at all levels (state, regional and local) through public policies and the setting up of criteria for action by all public powers. Such actions would be established on educational, health, artistic and cultural policies, as well as in the areas of the information society, rural development, housing, sports, culture, and spatial planning or development cooperation, among others.

In order to encourage the achievement of all this, the Law intended to apply a Strategic Plan for Equal Opportunities by creating an Inter-Ministerial Equality Commission. This Commission is responsible for coordinating, monitoring and preparing gender impact reports, as well as making periodic evaluations on the effectiveness of the actions carried out and meeting at least twice a year. The rhythm of actions and activities of this Commission have been irregular since it was created. However, with the coming to power of the current government of Spain, after a motion of censure, a new impetus was given to equality policies. An example of this is that on 7 November 2018, the Inter-ministerial Commission for Equality between women and men met, which had not met since 2011 (

Reunión de la Comisión Interministerial 2018). Among other things, the Commission agreed to prepare the Royal Decree for the regulatory development of Equality Units and to improve the coordination of existing Units in all ministries. It also agreed to begin work aimed at the reformulation of a new Strategic Plan for Equal Opportunities between men and women. This Plan includes four fundamental pillars: incorporation of the gender perspective in a transversal way, new social pact, citizenship and violence against women (

Tablado 2021).

Regarding the compatibility of people’s work and family activity, Organic Law 3/2007 introduced an important novelty with respect to the law in force until then (Law 39/1999, of 5 December). Thus, a 13-day leave was now established for fathers that was not contemplated in the previous legislation, as well as the extension of two weeks of leave in the event that a child is born with a disability. These two weeks can be enjoyed indistinctly by a father or mother. Qualitatively, this entails crafting an adequate legislative framework to foster the greater participation of men in raising children than had previously been contemplated.

3.2. Facts and Figures on Gender Inequality in Spain

Having seen the progress on the legislative level, we consider that now is the time to analyze the existing data in this regard. All this with the purpose of assessing to what extent the formal equality between men and women considered in the aforementioned legislation has actually been reflected in everyday reality.

In the first place, there are two groups of data that we are going to take into consideration in this section, given their special usefulness to reflect how the gender equality that is being talked about here materializes in reality. On the one hand, we consider data on the activity rate and on the other the data on employment rates. We do all this in order to see the proportions of women who remain exclusively devoted to the traditional role assigned to them as caretakers of their homes and families, and to determine the proportion of those women who have entered the labor market.

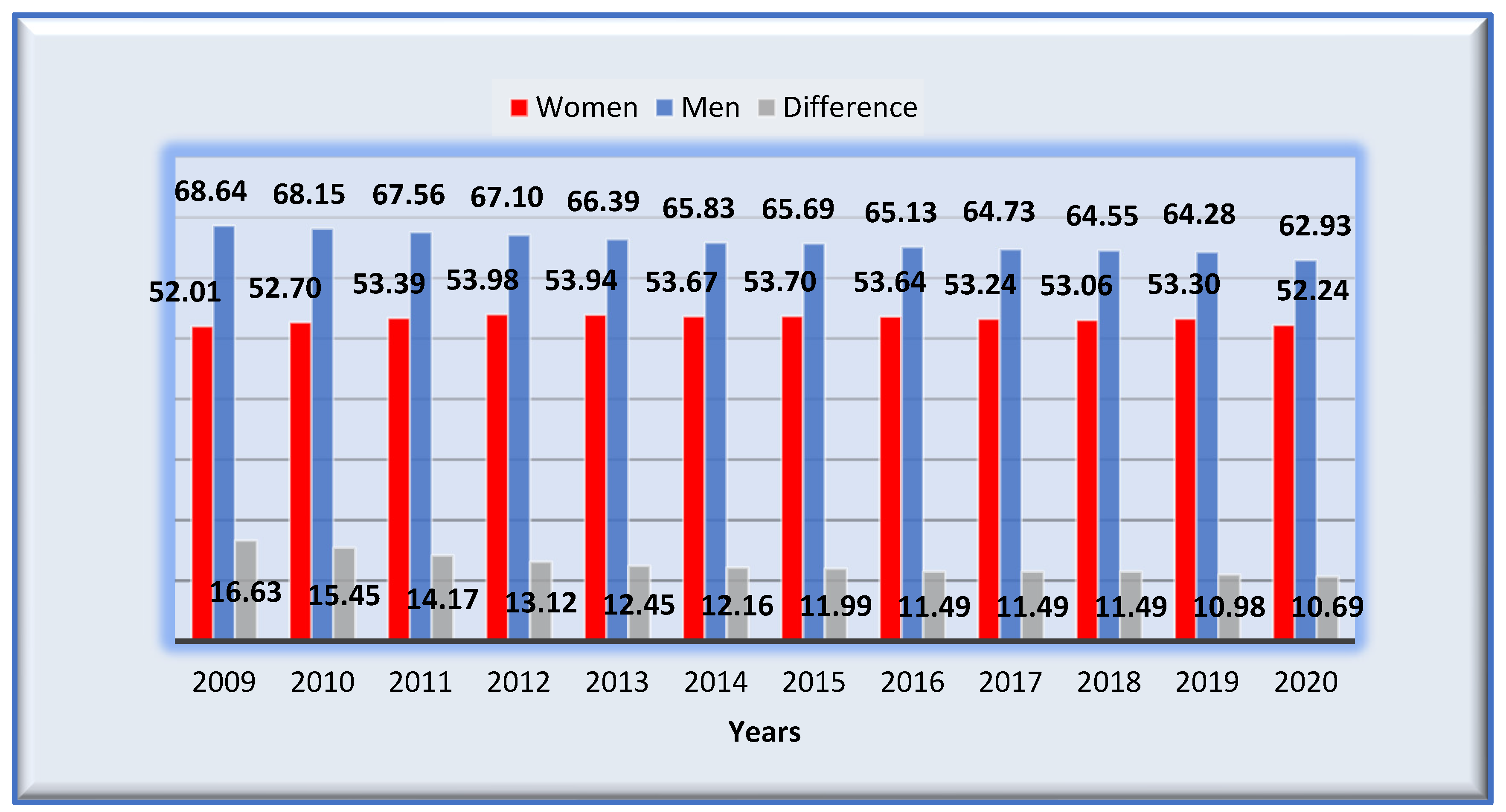

Regarding the activity rate, it measures, in percentage, the ratio between the active population (employed and unemployed) and the overall population over 16 years of age (all those of working age, even if they do not work or seek job). In this regard, as can be seen in

Figure 1, in Spain the activity rate of women remains below the activity rate of men. As can be seen in

Figure 2, the considerably higher inactivity rate in the female population is due to the fact that many women are dedicated to the care of adults with disabilities, to children and other family, or to personal motives. This fact is closely related to the fact that there are still a large number of women who are neither working nor looking for work outside the home since they are devoted to the social role that has traditionally been assigned to the female gender as housewives and/or mothers (

Glass and Fujimoto 1994;

Nandini et al. 2019).

In any case, the evolutionary trend in recent years has been towards a gradual decrease in the gender gap in terms of activity rates. Thus, in the time period referred to in the data on which

Figure 1 is based (2009–2020), the difference between the activity rates of men and the activity rates of women has decreased considerably, going from a difference of 16.63 points in 2009 to a difference of 10.69 points in 2020.

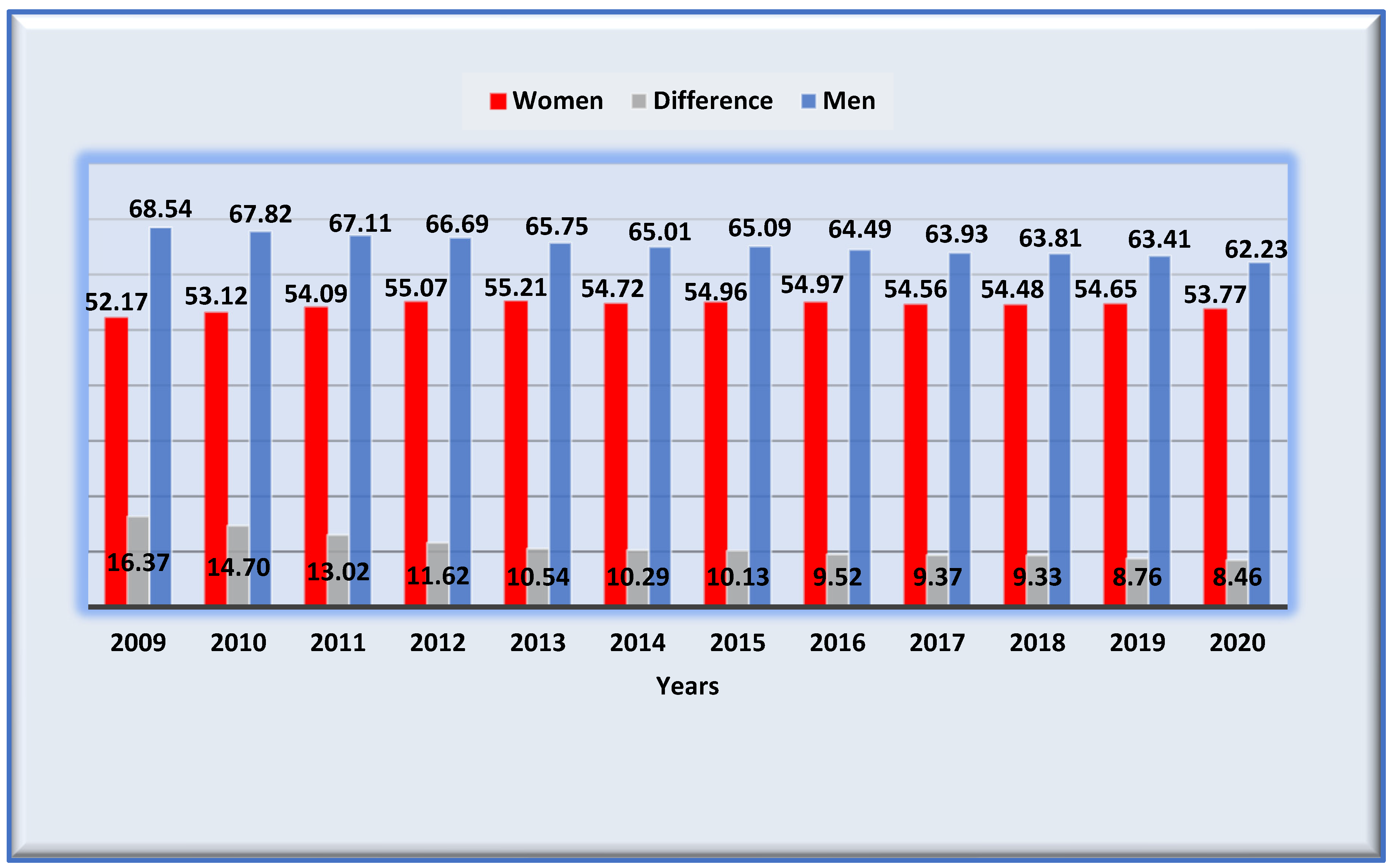

Regarding those people whose marital status is married (we do not have data on common-law couples who have not legally formalized their cohabitation situation), they show a trend similar to that mentioned above, as can be seen in

Figure 3. However, it is possible to observe a more pronounced decrease in the difference between the activity rates of men and those of married women, in such a way that, while in 2009 this difference was 16.37 points, by 2020 it had been reduced to 8.46 points. What is remarkable is that this happened despite the fact that many of the married women were combining their unpaid domestic work with their job outside the home (

Aguilar-Barceló and López-Pérez 2016;

Conejo-Pérez et al. 2021;

Fernández-Cordón and Tobío-Soler 2005). Therefore, we have here a proof of the great effort that these women made to integrate into the labor market. Anyway, despite the evident advances in gender equality that this data evolution shows, we should not forget that there is currently a noticeable gap in the activity rates of women compared to those of men. This is an indicator that there are still many women on the fringes of the labor market, who are often not looking for work and tend to be exclusively committed to caring for their family and homes.

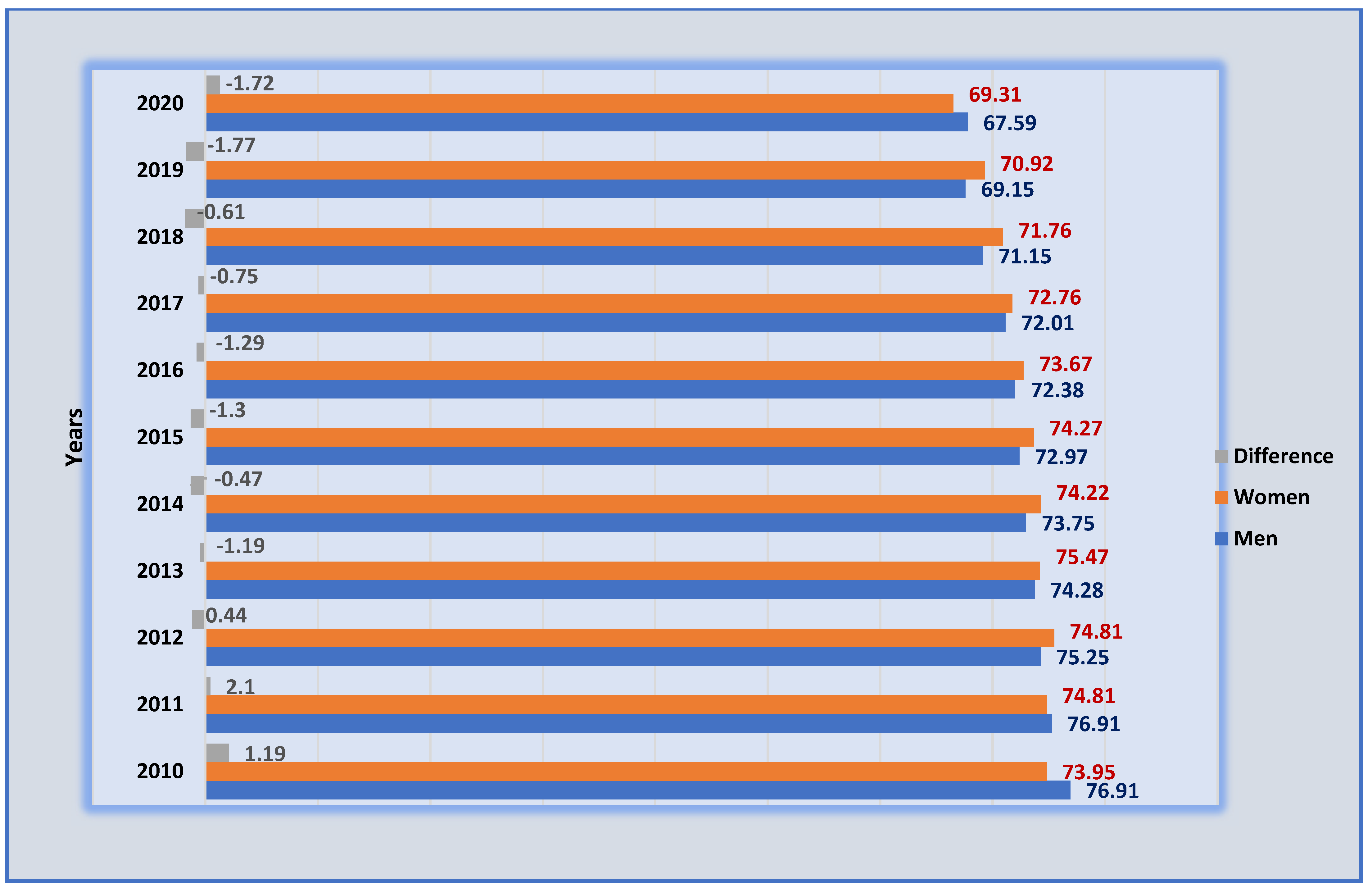

In contrast to the above, although as shown in

Figure 4 differences between male and female activity rates are still present, such differences are drastically reduced in the case of separated or divorced persons. Thus, in the period considered in this figure, it can be observed that the activity rates of divorced or separated men and women almost overlap. Furthermore, except for the years 2010, 2011 and 2020, the differences between male and female activity rates are negative; that is, in most years of the period studied, the percentage of divorced or separated women who work or look for work outside the home is higher.

Could this higher proportion of separated or divorced women who work or look for work be understood in the sense that these women are more pushed to look for an employment because they do not have the financial support of a partner? Or, could this situation reveal that there are a considerable number of women who, precisely because they choose to enter the labor market, renounce (or, rather, they are compelled to renounce due to circumstances) marriage? Or are only financially independent women ready to get out of an unhappy marriage while financially dependent women choose to stay in an unhappy marriage because they do not have an alternative? Regardless of the diverse and particular concrete answers that, to explain the case of each specific woman, may be given to the aforementioned questions, the truth is that, in general, the affirmative answers to such questions are in line with the reality of the situation of women in Spain, which, we reiterate, continues to show the existence of clear gender gaps despite the undoubted legislative advances produced in recent decades.

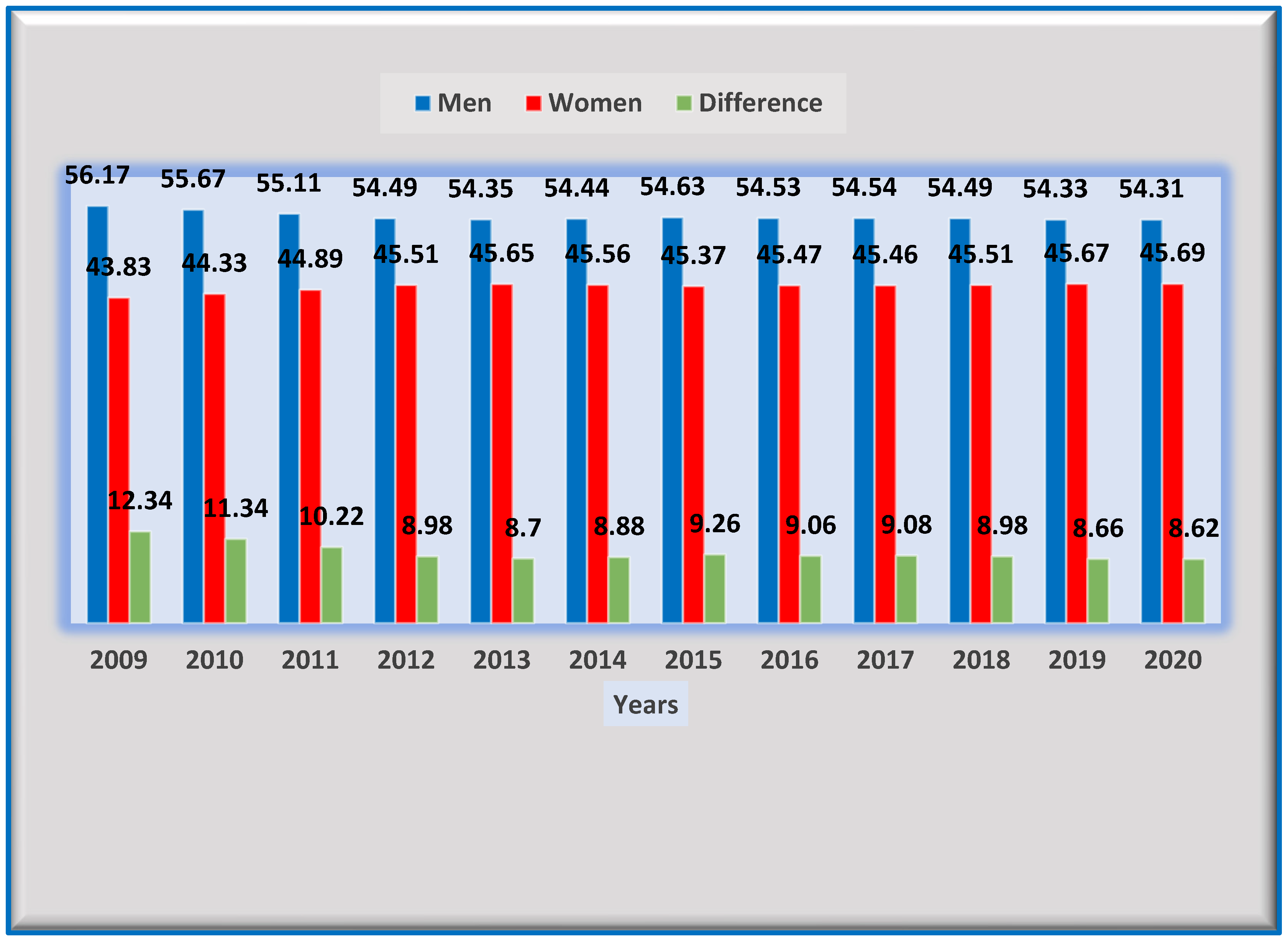

Apart from what has been argued before, we take into account the employment rate, which is the ratio between, on the one hand, the number of people employed included in the age range from 16 to 64 years, and, on the other, the whole population of the same age range, that is, the working-age population. In this regard, it should be noted that, as can be seen in

Figure 5, some progress is being made. Thus, despite the percentage of women employed being lower than those of men, it can be observed that the differences between the male and female employment percentages have been gradually reducing in the period referred to in this figure (2009–2020), in such a way that a gradual increase in the percentage of employed women has been experienced in this period, while at the same time there has been a trend towards a certain decrease in the percentage of employed men.

Regarding how male and female jobs are distributed by activity branches,

Figure 6 shows that there are activity branches in which male work predominates, activity branches in which female jobs predominate, and activity branches in which there is a certain gender parity. By activity branches with a predominance of male population, we understand those in which men working represent more than 60% of employment in that branch. Correlatively, the activity branches in which female population prevails are those in which more than 60% of their jobs are held by women. Finally, the activity branches in which it can be considered that there is gender parity are those that show a clear balance in the distribution of jobs between men and women.

Continuing with

Figure 6, we must explain to the reader that each of the activity branches included in it is divided into different categories of data, which we have omitted. The reason for this exclusion has been to prevent this figure from being larger and more detailed than it already is since that would have made it difficult to understand it. We make this clarification given that next, in addition to commenting on

Figure 6, we present a series of additional data and calculations that are not reflected in this figure; at the same time, we make several tables on that data.

First,

Figure 6 shows that the activity branches in which the majority of jobs are male are building, extractive industries, transport and storage, agriculture, cattle raising, forestry and fishing, manufacturing industry, and information and communications. In this regard, based on the information in this figure, we have calculated the distribution of jobs between men and women within each of these activity branches in which male jobs predominate over female ones. We detail the percentages of that distribution in

Table 1.

Secondly, also in

Figure 6, it is observed that the most feminized activity branches are household activities, real estate activities, health and social service activities, education, and other services. In this regard, based on the information in this figure, we have calculated the distribution of jobs between men and women within each of these activity branches in which female jobs preponderate over male ones. We detail the percentages of that distribution in

Table 2.

Third, the observation of

Figure 6 shows us that there are a series of activity branches in which there is a certain gender parity in the distribution of employment. These are the following ones: professional, scientific and technical activities; wholesale and retail trade, motor vehicle and motorcycle repair; hostelry; financial and insurance activities; administrative activities and auxiliary services; public administration and defense; mandatory social security; power supply (supply of electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning); and artistic, recreational and entertainment activities. In this regard, based on the information in this figure, we have calculated the percentage distribution of jobs between men and women within each of these activity branches. The percentage calculations carried out, which we present in

Table 3, show us that in these activity branches neither female nor male jobs exceed 60% in any case.

As we have mentioned previously, the professions included in the activity branches considered in

Figure 6 are very heterogeneous. Therefore, in addition to the aforementioned

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3, we now make a more detailed analysis of several of these branches, as well as in those cases in which the branch that we analyze in detail includes a number of categories of 3 or higher, where we create additional tables. All this is done in order to show how egalitarian the distribution of jobs really is within the different categories of activity that such activity branches include.

An activity branch that encompasses different categories within it is “Professional, scientific and technical activities”. Thus, in this branch, as can be seen in

Table 4, the following categories are contained: 1. legal and accounting activities; 2. central headquarters activities, business management consulting activities; 3. architectural and engineering technical services, technical testing and analysis; 4. research and development (R&D); 5. advertising and market research; 6. other professional, scientific and technical activities; and 7. veterinary activities. Among the aforementioned activities, only in that of “Architectural and engineering technical services; technical testing and analysis”, male jobs are the majority (65.22% of jobs), while in the rest of the activities female employment is the majority, especially highlighting the case of veterinary activities, in which women occupy 66.67% of jobs compared to men who hold 33.33% of them.

Another activity branch worth commenting on in more detail is “Wholesale and retail trade; repair of vehicles and motorcycles”. This branch includes the following categories of activities: 1. sale and repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; 2. wholesale trade and trade intermediaries, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles; and 3. retail trade, except of motor vehicles and motorcycles. As can be seen in

Table 5, both in category 1 and in category 2 employment is predominantly male. On the other hand, in category 3, female employment is the majority.

As for the hostelry branch, as we have pointed out before, it is a feminized activity branch when it comes to the distribution of employment. Thus, the following activities are integrated into this branch: 1. accommodation services (40.74% of male employment compared to 59.26% of female employment); and 2. food and beverage services (44.44% of male employment compared to 55.56% female employment).

Regarding the branch “Financial and insurance activities”, in

Table 6 we see that it is composed of the following activities: 1. financial services, except insurance and pension funds; 2. insurance, reinsurance and pension funds, except mandatory Social Security; and 3. auxiliary activities to financial services and insurance. In these three activities, female jobs are the majority but in none of them does the percentage of jobs held by women reach 60%, while male jobs exceed 41% in all three cases. In short, it could be stated that within this activity branch the distribution of jobs between men and women is relatively balanced.

With regard to “Administrative activities and auxiliary services”, these are made up of the activities listed in

Table 7. In this table, it can be seen that female employment is predominant in most categories, namely, in “employment-related activities”, “travel agencies activities”, “services to buildings and gardening activities” and “administrative office activities and other auxiliary activities to companies”. In contrast, male employment is only predominant in “rental activities” and in “security and investigation activities”.

Finally, with reference to “Real Estate Activities” and “Public Administration and defense; mandatory Social Security”, these activity branches do not include other activities within them. Therefore, we do not make any more comments about them here than we have previously made when we have discussed the data that is reflected in

Figure 6.

As is well known, there is usually a relationship between the educational level attained and the distribution of people employed by sex. In this respect,

Figure 7 shows that, except at superior education levels, where the number of employed women is markedly higher than that of men with the same educational level, as a general rule the number of employed men is greater than that of women employed at all educational levels. The smallest differences between men and women are found in upper secondary education levels (second stage of this education, either with general or professional orientation), while the greatest differences, as shown in the figure, are found at the level of the first stage of secondary education.

As can be seen in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, the relationship between the educational level attained and the distribution of employed persons by sex does not vary significantly when we distinguish between married employed persons and unmarried employed persons. In this way, similar to what

Figure 7 shows, in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 it is observed that the number of men employed in all educational levels is greater, except in the case of higher education, in which there are more women employees than men. Furthermore, with respect to the unmarried employees (

Figure 9), it is observed that the differences between employed men and women with the same educational levels are less than in the case of married employees, except for the cases of the second stage of secondary education (professional orientation) and especially in higher education, in which the number of unmarried women working is considerably higher. In sum, the analysis of the information provided by

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 seems to contribute to validating the thesis according to which, as people’s educational levels rise, gender parity increases in terms of job opportunities; moreover, such parity would tend to be higher among unmarried persons.

As can be seen in

Table 8, in the cases of three economic sectors of great weight in employment and GDP such as industry, building and services, the average annual earnings per worker for women was lower than the average annual earnings for men in 2019. So, in these three cases there was an evident pay gap for women compared to men. The notable decrease in this gap in the building sector could be understood in the sense that in this sector there are very few women who work and most of them have high educational levels.

The salary gap between men and women is also evident in

Figure 10 and

Table 9. Thus, based on the latest available data provided by the Annual Salary Structure Survey, we have prepared this figure and table, in which it can be observed that that gap unfortunately had remained quite high in recent years.

Nevertheless, in 2019 there was a certain improvement in this gap. Thus, according to the Annual Salary Structure Survey, the wage salary gap between women and men was 19.5% in that year; in other words, it had fallen 1.9 points with respect to the existing gap a year earlier. The slight improvement produced compared to 2018 was due to the fact that women’s wages increased more than those of men in 2019 (3.2% compared to 0.7%). However, the truth is that in 2019 women earned on average 5252 euros per year less than men. Given the fact that we have not worked with data for the years 2020 and 2021 (the COVID-19 period), we cannot be sure at this time if this trend towards the decrease in the wage gap for women has remained the same, has improved or has worsened.

In this regard, the current socialist government of Spain has applied measures aimed at preventing the destruction of employment and the drop in income of the population in these times of health crisis (

Papell 2020;

Ruesga-Benito and Viñas-Apaolaza 2021). Such measures, although they have proven to be effective, have not managed to avoid all the negative effects on employment of COVID-19 (

Araújo-Vila 2020;

Gómez and Montero 2020). Women are precisely the most negatively affected by this situation, given that compared to men their employment levels are lower and their unemployment rates higher. Therefore, policies that do not address the different realities of men and women will aggravate pre-existing gaps (

Salido-Cortés 2021;

Solanas 2020).

The gender pay gap is also evident when we focus our attention on the activity sectors. Thus, as

Table 10 shows, in 2019 the average annual salary of women was lower than that of men in all the occupations listed in that table.

Particularly with regard to the wage distribution, according to the

Annual Wage Structure Survey (

2019), 25.7% of women had in 2019 wages lower than or equal to the Minimum Wage (

Salario Mínimo Interprofesional), whose annual quantity amounted to 12,600 euros in that year. However, the proportion of men with the same payment level was then 11.1%. This situation of undoubted wage inequality for women was influenced by the highest percentage of women working part-time. If we focus our attention on those who received the highest remunerations, then the pay gap to the detriment of female population was still even more evident in 2019. Thus, while in that year 4.1% of men received wages five times higher than the Minimum Wage, in the case of women only 2.1% of them reached these income levels. However, gender pay inequality is also evident among low-earning workers; that is, those employees whose hourly payment is below 2/3 of the average income. Thus, the proportion of workers with that level of income in 2019 was 15.0%, of which 63.9% were women. One explanation for this lies in the fact that these low salary levels are usually more widespread among part-time workers, of which the majority tend to be women (

Annual Wage Structure Survey Year 2019).

In short, the information and data analyzed above show that, at present, there are still clear gender inequalities in Spain. However, the evolution towards greater equality between the sexes that has been taking place in recent decades is encouraging. Undoubtedly, this positive evolution became possible with the arrival of democracy, after the death of dictator Franco, created appropriate legal conditions for progress in this direction. In any case, this progress reflects the crushing slowness of the desirable changes and how much still needs to be done.

One of the challenges still pending in order to achieve gender parity is the creation of truly equal conditions in which men and women can be held jointly responsible for the tasks inherent in caring for their home and children, and that they can do that in a harmonized way with their work. All this applied if we really aspire for the adequate compatibility of work and family life to be shared by men and women on equal terms and not remain an almost exclusively female obligation as has happened, and will continue to happen too frequently.

In any case, the inequalities suffered by women in the workplace are not only due to the fact that they often earn lower wages than men. Thus, a part of these inequalities is due to the fact that there is still an excessive proportion of responsibility positions held by men in the workplace. Such positions, which men have more opportunities to access, involve great decision-making and organizational skills. This is mainly due to the fact that a social mentality or perception is still widespread according to which the duties of caring for children and the home are intrinsically feminine. Consequently, men are or may feel ‘liberated’ from these obligations and have all their time to devote to their professional careers. These circumstances or social customs mean that a high proportion of women cannot de facto choose (or, even, do not even consider opting) to occupy positions of high responsibility in which the top wages are charged. This is how what is called the glass ceiling is produced; that is to say, a de facto situation that makes it impossible for women to access certain job positions with a high socioeconomic level and an advanced job qualification requirement.

Weighty changes are still needed in order to achieve parity between men and women, not only at the level of social and labor rights (which are already egalitarian in our country) but also and above all at the level of the facts, that is, of the economic, educational and cultural circumstances that continue to maintain the gender gap and the reproduction of the social mentalities that sustain it. Particularly, an ingrained persistence of such mentalities was evident in the last Survey on Quality of Life at Work carried out in Spain in 2010 by the Ministry of Employment and Social Security. From the data of this Survey, we have made

Figure 11, which shows the opinion that the interviewees of different sexes had about the possibility of requesting or not a work leave to take care of their family. We can see in this figure how that opinion was different depending on whether the interviewees worked in the private sector or in the public sector.

Thus,

Figure 11 shows that more than half of the women interviewed (52.6% of them) who worked in the public sector thought that taking a leave of absence for family reasons would not affect their professional careers. In contrast, the proportion of women who worked in the private sector with the same opinion was reduced to 40.5% of those interviewed. Additionally, in the case of men, the majority of those interviewed who thought that it would not affect them to take a leave of absence for family reasons (48.5% of them) worked in the public sector, but among private sector employees the proportion of men who thought the same amounted to 41.6%. As can be seen, there are hardly any differences (1.1%) between the percentages of women and men working in the private sector who thought that taking a leave of absence would not affect their professional careers. Nor is the percentage difference (4.1%) between women and men in the public sector who expressed the same opinion very high. This fact, together with the fact that these percentages were clearly below their equivalents in the public sector, could be understood in the sense that both sexes shared a kind of ‘business culture’. According to this ‘culture’, it seems that asking for leave is not looked favorably upon by a noticeable quantity of people who tend to consider something like that exercising the right to take leave of absence entails losing work time.

In relation to the aforementioned, another noteworthy fact from

Figure 11 is that, both among public sector workers and those in the private sector, there were more women than men who perceived that taking a leave of absence to care for their family would negatively affect their professional career. Likewise, among both private and public sector workers, the proportion of men who thought it was inappropriate to take a leave of absence for caring for their family was higher than that of women who thought the same. In other words, a large part of these women, in some way, felt that their family responsibility impelled them to ask for that leave of absence. Finally, for both sexes, it is worth highlighting the fact that the proportion of those who considered it inappropriate to take a leave of absence for family reasons was higher among private sector workers than among those who worked in the public sector. Undoubtedly, apart from the above-mentioned ‘business culture’ reasons, this is closely related to the fact that, in the public sector, working conditions are generally more stable and less precarious than in the private sector, which facilitates a bigger perception of social protection and greater capacity to exercise labor rights among public sector workers than among those in the private sector.

As has been asserted before, the previous comments have been made based on data that were collected in 2010 through the last Survey on Quality of Life at Work carried out in that year. The sad thing is that, unfortunately, the circumstances have hardly improved since then, as far as overcoming female inequalities is concerned. Thus, as can be seen in

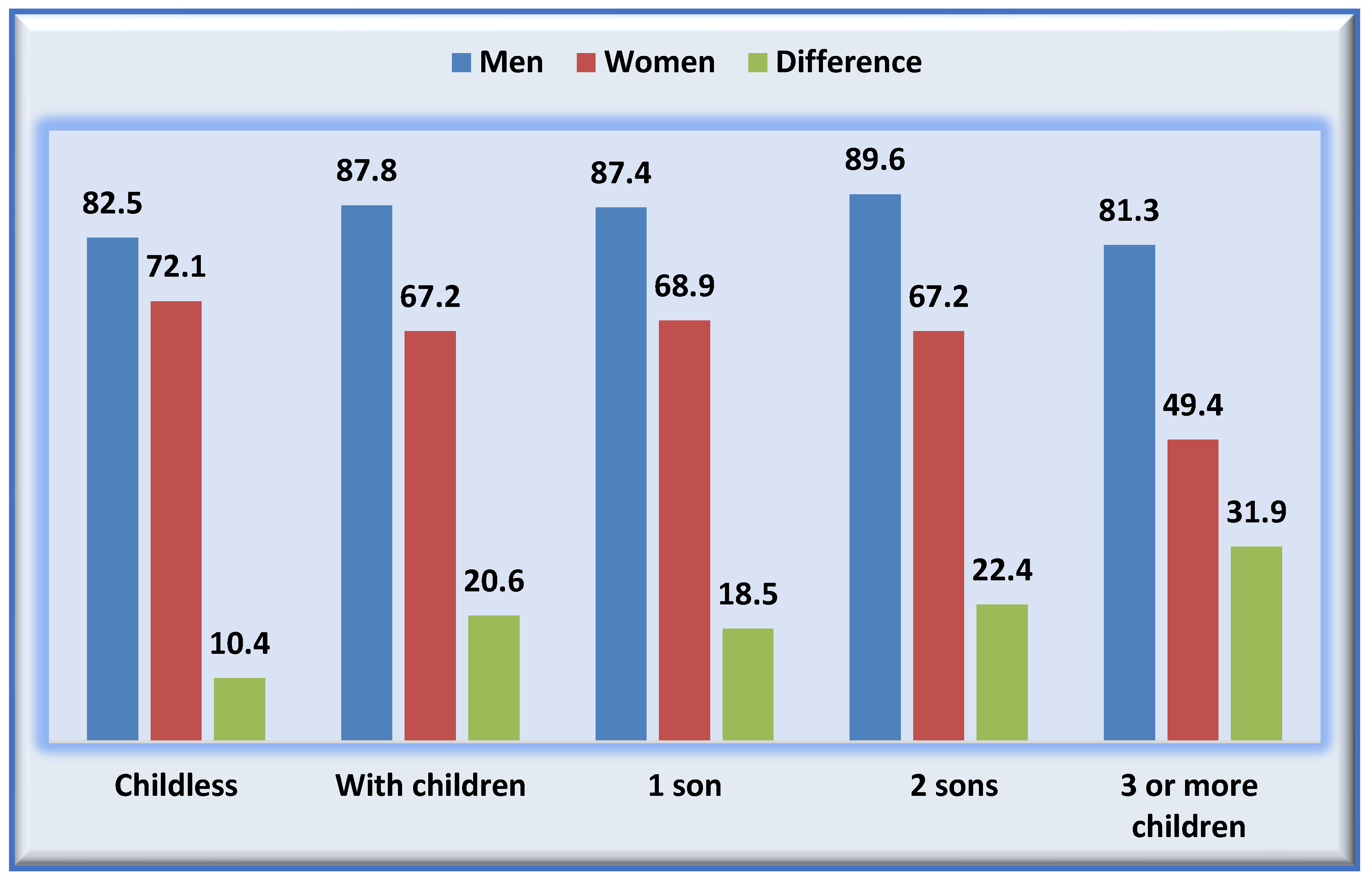

Figure 12, made with data from 2020, female employment rates, which are in all cases contemplated in this figure below male employment rates, are higher and are closer to the employment rates of men among women without children. In addition, employment rates are greatly reduced among women with children who due to their age have to be cared for (that is, under 12 years old), but this does not occur among men who have children of the same age. Furthermore, as the number of children of caregiving age increases, the proportion of women working decreases, while in the case of men, this proportion does not undergo significant changes.

Unfortunately, the situation reflected in

Figure 12 is not something that has only occurred in 2020 but is a highly rooted social phenomenon that makes many women dedicate themselves to caring for their children, and therefore they do not seek work outside from home or even leave that job if they have it. In this way, as can be seen in

Table 11, in the period 2011–2019 the lower percentages of employed women with children under 12 years old have been a constant in relation to men with children of the same age. What is more, as the number of children has increased, the percentages of female employment have become lower.

Thus, recent data available show that women continue to be primarily responsible for caregiving. In this regard, according to 2018 Labor Force Survey (EPA) data, 86.9% of men interrupted their work for a maximum period of six months to devote themselves to taking care of their family (

Mujeres en Cifras 2020). Nonetheless, in the case of women, the interruption periods for the same reason were more distributed and, in addition, for a significant part of them, they were longer. So, 49.9% of women interrupted their work for six months, 20.9% between six months and one year and 9.4% between one year and two. In addition, it should be noted that the percentage of women who interrupted their work for more than two years was 17.7%, compared to 2.8% of men.

To a large extent, this is due to the fact that there are still many women who have internalized, as their own and almost exclusive to their gender, the responsibilities of home caregivers. The internalization of this responsibilities by many women, the emotional pressure, and the health problems that this often entails for them are facts that the second author of this article has been able to verify in the interviews carried out on the occasion of his involvement in two previous qualitative studies (

Del Río-Lozano et al. 2013;

Entrena-Durán et al. 2021).