Abstract

In Japan, the term shūkatsu—referred as the planning for later life and for the afterlife—has gained popularity due to high amount of mass media exposure in recent years. This paper examines shūkatsu from the active aging framework, contending that shūkatsu is an important activity that contributes to active aging, as the process of conscientious planning encourages older Japanese people to remain active. Data for this study were obtained from qualitative interviews that were conducted with 40 older middle-class Japanese citizens residing in Nagoya. Explored through a life course perspective, the study examined how salient factors, such as personal history, experiences, roles, anxieties, life-changing events, and cultural practices, have influenced older Japanese people in their shūkatsu decision-making process. In the process of understanding how the Japanese respond to changing family relationships and sociocultural transformations, the emphasis on living a “good old age” for better social, psychological, and physical well-being strongly reflects the agency to age actively. In a super-aged Japan, shūkatsu may be a vital strategy that not only ensures a better quality of life for the older population and their children, but it also contributes to individual’s sense of usefulness and satisfaction, as they are actively involved in the planning and management of their own later and afterlife choices.

1. Introduction

Among the array of positive gerontological frameworks, active aging has been widely promoted by World Health Organization (2002) to address the challenges of global population aging. The active aging framework calls upon policymakers, organizations, and civil society to act and plan ahead so that the quality of life in old age can be enhanced through the optimization of health, participation, and security. In essence, it is a global early intervention strategy that aims to mitigate aging-related risks. Under this framework, aging is a process that takes place over the course of one’s life and requires both individual and collective responsibility (Walker 2002; World Health Organization 2002).

While active aging policies and programs are formulated with the aim of lightening the increased social and economic demands of aging societies, for the individuals, the concept advocates that they take personal responsibility in planning and preparing for older age. In the same vein, from the perspective of biopolitics, where a good life is influenced by political and cultural expectations, a responsible individual is one who strives for an active old age by staying healthy and refraining from welfare services if possible (Lassen and Andersen 2016). This paper focuses on active aging as an individual effort that is explored through the practice of shūkatsu in Japan.

In recent years, older members of the Japanese population have become more conscious in planning for later life and for the afterlife through shūkatsu,1 an act that can be broadly defined as the preparation for funeral and grave arrangements, inheritance matters, health and medical care, and other planning for later life (Kimura and Ando 2018). From a macroscopic perspective, the active aging framework addresses the risks of aging societies worldwide, but in the same vein, from a microscopic viewpoint, we propose that shūkatsu is a risk-avert practice that older Japanese citizens engage in as a response to demographic and socio-economic-cultural transitions in Japanese society. As such, shūkatsu could be perceived as contributing to active aging, where the process of conscientious later and after life planning encourages older Japanese citizens to remain active. In this study, we explore shūkatsu from a life course perspective and examine how salient factors, such as personal history, experiences, roles, anxieties, life-changing events, and cultural practices, have influenced older Japanese people in their shūkatsu decision-making process.

1.1. Shūkatsu and Individuals

While planning for later life and the afterlife is not new, the use of the term shūkatsu and research on the topic has been limited, as the term was only coined and popularized by the Japanese mass media in the 2000s. Shūkatsu was initially specifically related to matters of the afterlife when the term was first coined in Shukan Asahi (the Asahi weekly magazine) in 2009, when the magazine published a 19-week series of articles discussing afterlife-related and specifically matters pertaining to the preparation of funerals and graves. In Japan, mortuary tradition, funerals in particular, and the subsequent periodic rituals, are important rites of passage in the culture of aging (Tsuji 2011). They are also intently related to the Japanese family system; for instance, a family grave2 carries the collective identity of a family.

Created during the end of the nineteenth century of the Meiji period (1868–1939) and abolished in 1947 after the war, the Japanese family system, or the ie system, was guided by the ie ideology, which was based on the belief of safeguarding a household through reciprocal relations (Wada 1995). In the ie system, the eldest son was usually the heir to the family assets and was also the one who had to take care of the funeral and the family grave. In pre-war Japan, funeral preparations were community-based, and rituals were often conducted with assistance from relatives or neighbors (Ueno 2009). After the war and as a result of urbanization, children and relatives began living geographically apart, and funerals became commercialized (Suzuki 2002).

The 1990s were epochal years in which the Japanese began to have diverse views towards the choices of funerals and graves (Kawano 2003, 2004a, 2004b; Suzuki 1998). After mass migration from rural to urban areas in the 1950s and 1960s, community ties weakened, and it became necessary for the Japanese population that was living in urban cities to rely on professional funeral services (Kawano 2004a, 2004b). Nevertheless, while the funeral industry flourished, many Japanese people became increasingly dissatisfied with the lack of personal control over their loved ones’ funerals and the exorbitant prices they had to pay for funeral packages (Suzuki 2013). The long-established connections between funerals, memorial services, and the Buddhist temples were being questioned by citizen groups (Kawano 2004a, 2004b) The lack of space for graves in big cities also prompted the Japanese to reconsider the custom of the family grave system (Breen 2004). To have posthumous independence and freedom, women who did not get along with their husband or mother in-law explicitly declared that they did not want to be buried in the same grave (Tsuji 2018). By the mid-1990s, books and articles on funerals and graves were written to encourage older people to have better control, to plan in advance, and to reconsider their options in mortuary ceremonies.

In the 21st century, triggered by fast-paced demographic and sociocultural transitions, the older Japanese population become even more conscious of their end-of-life preparations. Japan had become widely known as long-living society by then, with the country’s average lifespan being the highest in the world, sitting at 81.41 years for men and 87.45 years for women in 2019 (Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications [MIC] 2021). In 2020, the segment of the population that is aged 65 and above accounts for 28.8% of the country’s population, while the total fertility rate continues to remain low at 1.34. As a “super-aged society”, the death rate (per 1000 population) has maintained an uptrend since 1988, reaching 11.1 in 2020 compared to around 6.3 in 1987 (ibid.). At the same time, couple-only and single-person households have increased from 36.3% in 1990 to 58.2% in 2016 (Cabinet Office Japan 2018). These factors have led to concerns regarding a lack of successors to take care of family graves and an increase in the fear of solitary death (Suzuki 2013). Nevertheless, apart from afterlife matters, with prolonged longevity, there have been realization that even if one were to retire at 65 years old, life after retirement could span another 25 years or longer. Healthy and active older Japanese citizens are given a lot more time to contemplate the way they want to live their later life as well as the many choices that they now can make with their extended lifespan; and one of the ways to manage this is through the engagement of shūkatsu.

1.2. Planning for Later Life and Shūkatsu

Old age is associated with risks. In later life, one is faced with the risks of inadequate income, social isolation, failing health, and the fear of losing independence (Denton et al. 2004). Beck’s (1992) theories of risk society highlighted other risks that are associated with old age; for instance, risks resulting from medical and technological advancements, the transformation of society, and changing traditions and customs caused by the increase in nuclear families. Despite these uncertainties, Beck argued that some risks are predictable and can be evaluated; hence, actions can be taken to reduce them. One can achieve the goal of living an independent and desirable later life through the reallocation of resources (Kornadt and Rothermund 2014). In other words, one takes actions ahead of time in order to avoid predicted problems from developing in the future when planning for old age (Jacobs-Lawson et al. 2004). In a similar vein, Giddens’s (1991) notion of reflexivity maintained that people are capable of critical self-reflection and are thus able to engage in reflexive planning to determine how they want to live their lives.

In modern states, growing old has shifted from a collective responsibility to an individual mastery, where people reflect and make choices regarding their current life situation (Phillipson and Powell 2004). Some people are motivated to plan because they believed that if they actively planned and prepared, they would have control over their lives and be “agents of change” (Denton et al. 2004, p. 79). Some people plan for psychological wellbeing. When people become conscious of a risk, they gather information, make relevant choices, and take actions (Pinquart and Sörensen 2002). When they are better prepared, they tend to be more satisfied with their later life. Planning is also for the wellbeing of the family, for instance, in making funeral arrangements (Samsi and Manthorpe 2011).

Conversely, thinking about future risks without any active planning may cause anxiety (Skarborn and Nicki 1996). While some people do not plan because they do not know how long they are going to live (Brown and Vickerstaff 2011), older women exhibit pragmatism, and they are found to be preparing themselves for long-term care actively, as they expect themselves to live a longer life (Black et al. 2008). Women tend to suffer from more than two chronic conditions compared to older men (Hooyman and Kiyak 2002). Hence, people might be more inclined to plan ahead for risks that they perceive to have a high probability of happening in the future, for instance, future care needs. In sum, people plan for different reasons and priorities, and their planning process are influenced by the interplay of multiple factors—financial resources, age, health, gender, perception of life, sense of urgency, or familial transitions—over the course of one’s life.

1.3. Planning in the Name of Shūkatsu

Although later life planning has been extensively examined by scholars, engagement in shūkatsu from the perspective of planning has not been sufficiently addressed, and most studies on shūkatsu are limited to online surveys. Consistent with Kimura and Ando’s (2018) study on the evolving meaning of shūkatsu, an online survey that was conducted by the Kumamoto Institute of Research (2017) also reported similar perceptions of shūkatsu. That is, issues such as long-term care, medical care, funerals, asset management, inheritance, or even the management of personal data on mobile phones and computer have remained the main concerns. The study also reported shūkatsu as a process of self-reflection, a stage in one’s life in which one begins planning for later life or to live a life where one is true to themself. Both genders became conscious of shūkatsu planning after the age of 60, but women were more proactive in shūkatsu than men. The main purpose of shūkatsu was to avoid burdening their loved ones, and more than half stated the importance of completing shūkatsu preparations before becoming ill or before needing to be taken care of. When writing an ending-note,3 in addition to listing down personal assets, wishes as they pertain to funeral and grave arrangements, and instructions on treatment if one became terminally ill are mentioned. Although many people seemed to know about the ending-note, only 3.7% (Kumamoto Institute of Research 2017) and 2.4% (Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting 2012) had written one. Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting (2012) reported that people, especially women, became more inclined to write an ending-note as they become older or after experiencing the illness or death of a loved one. It was also reported that only a small percentage of people had completed their shūkatsu, for instance, 5.4% from Kumamoto Institute of Research (2017) and 10% from a survey conducted by Nikkei Shinbun in 2017.4 Nevertheless, we argue that the definition of “completion” is subjective and vague. As one continues to age, one’s mindset may change, and reviews can be made even after completion. Instead, we suggest studying the rationale behind the decision-making process of why people plan and engage in shūkatsu in greater depth.

It should be noted that shūkatsu could be a controversial matter. Drawing from interviews with shūkatsu experts (e.g., shūkatsu planner and funeral business vendor) and with the general public, Mladenova (2020) investigated shūkatsu from the perspective of governmentality and subjectivation and criticized it as a “governmental program that encourages the transferal of government to the self” (p. 106). Although shūkatsu is not a creation of the state, with the shūkatsu experts encouraging individuals to be independent and to take matters into their own hands, she argued that shūkatsu might become another tool that the state uses to shape the conduct of the Japanese. In other words, shūkatsu would reduce state responsibility if individuals were to become responsible for their own lives. Nonetheless, the study underlined the importance of individual perceptions of shūkatsu, seeing the need for some planning as well as the need to make certain end-of-life decisions for the good of their children.

2. Data Collection

Data for this study were collected through the qualitative interview approach, an approach effective for gaining deep insights into the nature of how shūkatsu is perceived, understood, and performed by older adults in contemporary Japan. A total of 40 respondents (20 males and 20 females) who lived in Nagoya city were recruited for the study through a snowball sampling method. A heterogeneous group of respondents that was diversified by age (age 60–84), marital status, and living arrangements was recruited to ensure diversity in the voices of the respondents (see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). The respondents came from middle-class5 backgrounds, and with the exception of one, all of them owned their own house. Out of the 20 men, 4 were self-employed, and the other 16 belonged to the “salarymen” (a white-collar businessman) category. Among the women, half (10) had been full-time housewives since marriage. Fifteen of them were married to spouses who were salarymen. Apart from those who were still actively employed and had not reached the age required to collect their pension (age 63), pension and savings were the major sources of income for the majority of the respondents.

Table 1.

The respondents.

Table 2.

Marital status of respondents.

Table 3.

Living arrangements of respondents.

The interviews were conducted by the first author face-to-face in the respondents’ homes, offices, or at designated places (e.g., cafes, restaurants). Overall, the respondents were articulate, enthusiastic, and comfortable to share many of their thoughts. Probes for elaboration and clarification were used consistently throughout the interview to explore the content in more depth and to integrate more detail into the respondents’ answers (Creswell 2012). In addition to the questions that were asked, the respondents were also encouraged to narrate their personal stories and experiences and to give other general comments. The interviews were audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and then translated from Japanese into English. Thematic coding was conducted using the Atlas.ti software, and the findings were analysed through the lens of a life course perspective. The study was approved by the National University of Singapore’s ethics board.

3. Narratives and Discussion

This section presents and discusses the narratives of how shūkatsu is perceived and why shūkatsu is actively engaged in by the respondents from the five principles of the life course perspective, namely agency, linked lives, time and place, lifespan development, and timing.

3.1. What Comprises Shūkatsu?

Extended longevity has made old age an increasingly prominent life stage for most Japanese. Later life is planned differently, as individuals adjust to changing expectations that are related to changing roles and identities and to shifting relationships and obligations between family members (Ronald and Alexy 2011). Likewise, the respondents interpreted shūkatsu subjectively and prioritized different tasks.

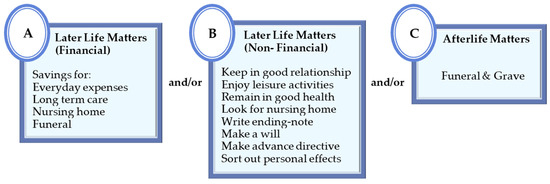

Among the respondents, shūkatsu was perceived broadly as comprehensive planning for aging (see Figure 1). Financial matters (A) were considered important but were mentioned the least often when compared to non-financial (B) and afterlife matters (C). Only 8 respondents perceived it as (A + B + C), 25 regarded it as (B + C), and 6 considered it to be afterlife-related matters.

Figure 1.

Shūkatsu in the Japanese context.

With the exception of one male respondent who declared that he did not see the need to do any particular planning for his later life, about half of the remaining 39 respondents had begun some shūkatsu activities, such as sorting out their belongings, writing an ending-note, and searching for a nursing home or a grave (see Table 4). Most of the 39 respondents, whether they had begun their shūkatsu or not, agreed unanimously that they bore the responsibility to complete at least some shūkatsu, especially in terms of sorting out of their own effects. Some of the participants felt that it was not time for them to begin shūkatsu yet because they were still in active employment, in very good health, or had surviving parents. Some disliked the word because it had a negative notion of admitting that one was old, approaching death, or giving up the things that one liked to do. Interestingly, talking about death was not a taboo for the respondents. When the first author raised the question on death, everyone talked about it rationally and intellectually. Many even told the author why they preferred certain funeral styles and how they wanted to be buried.

Table 4.

Number of respondents engaging in Shūkatsu.

Shūkatsu was perceived as a private matter to be discussed only with family members or very close friends. The respondents did not mind learning or collecting information on shūkatsu from the mass media, the Internet, or from friends, but they were not keen on attending any “shūkatsu festivals”6 nor on talking to an outsider, for instance, a shūkatsu councilor.7 Even if the local government offices8 were to organize shūkatsu workshops, none of them showed any interest in attending. Most viewed the shūkatsu festivals as business gimmicks that funeral business vendors used to target the elderly, and the respondents did not see the necessity of having a counselor nor the local government teach them how to plan their lives.

3.2. Agency: I Have to Be the One Taking Action

Agency is a choice-making process that takes place when an actor takes actions within conventional boundaries (Elder and Johnson 2003). With the exception of unanticipated circumstances, the respondents wished to live to old age even though extended longevity meant greater uncertainties. Shūkatsu was used as a strategy to cope with future anxieties. Faced with the likelihood of outliving their husbands and the aging of adult children, many of the female respondents, especially those that were widows, tended to visualize future risks and engaged themselves in various preparations. For instance, many raised the issue of getting themselves into a nursing home if they were to become senile or bed ridden. The following demonstrated how two respondents averted foreseeable risks by taking swift action before they became ill or frail:

Of course I’m living my daily life as before, but there are things I have to do before I die… even if I die, I want to make sure none of my daughters will be burdened… shūkatsu is for the sake of my two daughters… actually, I’m going to apply for a nursing home tomorrow, one that’s run by the city… I just can’t get in any time I want to, I have to wait… so if I apply now, I should be able to get in when I become 80.(Keiko, 76)

Recently, we talked about the 8050 problem (parents who are in their 80s and children in their 50s), when I heard that, it reflected on me; I’m 77, and my son is 55. He has a family, and his children are married, but when I thought of myself at the age of 90 and my son would be close to 70, when I think of that… that’s frightening… when my husband died, I had to handle and settle many things. I don’t want my children to go through the same process when I die. Can you imagine a 70-year-old man tending to a 90-year-old woman? I don’t want my son spending the rest of his life taking care of me… and now we are into an era of living up to 100 years old. When I think of that, becoming old and living a long life is not that easy, you know.(Kiyomi, 77)

Kiyomi had never thought about her shūkatsu until she realized that she would not remain in the same state of health. After she turned 70, she had a few operations for cataracts, her kneecaps, and thyroid glands. Even though she had recovered, she knew that she would experience other illnesses as she aged, and she realized that her son might have health issues too when he grew older. “Even if I have my daughter in-law living with me, I can’t make her do the dirty jobs”, said Kiyomi. Both Keiko and Kiyomi advocated shūkatsu. While Keiko had sorted out many of her belongings, Kiyomi had consolidated her bank accounts, told her son what she wanted for her funeral, and stated that she would write a will for her two sons soon.

Most of the female respondents who had begun shūkatsu demonstrated that they were not passive recipients of extended longevity. Agency is demonstrated by the different choices and decisions that one makes to resolve the uncertainties resulting from a longer life. The respondents also made these decisions to ensure that their children were able to live their lives independently.

3.3. Linked Lives: It Is about Keeping a Good Relationship

The principle of linked lives emphasizes that lives are closely interconnected with one’s family and shared relationships (Elder 1998). Some shūkatsu activities cannot be carried out without the support and collaboration of one’s family. The family, a micro-social unit within a macro-social context, is defined by Bengtson and Allen (2009) as “a collection of individuals with a shared history who interact within everchanging social contexts across ever-increasing time and space” (p. 470). When an individual ages, children play a pivotal role, from providing care to handling their parents’ afterlife matters, such as the funerals and mortuary rituals. Those who are single or who do not have any children usually rely on other social ties, for instance, siblings, nephews, nieces, or other close kin to handle such matters.

The respondents desired to not be a burden on their children, “It’s better not to think that your children will take care of you. When you become old, you have to keep yourself healthy, be independent, and not burden your children”. There were two types of burden that were mentioned the most frequently. The first kind was usually related to afterlife matters.

Make sure your children know what to do… and if you have things to give them, make sure they are properly divided… as long as those who are alive are in a good relationship, I think the dead one will be satisfied.(Miho, 61)

The death of a parent is probably one of the most difficult turning points for many adult children because it signifies an end to an emotionally bonded relationship with an individual that one has maintained over the course of their life (Moss and Moss 1984). Sibling relationships can be strained for many reasons, for instance, in providing care, the handling of funerals, the division of assets, and taking care of the grave. One of the female respondents mentioned that she had to make sure that her daughter understood why she was giving away some of her jewelry to her daughter in-law for taking care of her. With an increase in nuclear families and children living apart, many emphasized the importance of having one’s last wishes properly written down so that the children would not panic or end up having arguments over funeral matters. The purpose of shūkatsu, especially to many female respondents, was to make sure that the siblings maintained a good relationship after the death of their shared parent. In terms of taking care of the grave, the female respondents also shared similar sentiments.

Yes, my son will be the next one to look after the grave… if I go first, my husband will be the one to decide about the grave, but if I am the one left behind… it is not the grave that is important to me, but it is the ancestors, so I will do a haka-jimai9 and put the ash in a columbarium and do an eitai-kuyō10 so that the temple can take care of the rituals and the ancestors. It would be difficult for me to look after the grave when I become too old… we belong to a particular Buddhist sect, and there’s quite a lot of rituals we have to follow, and my sons, one lives in Tokyo and the other lives in Kyoto… it will be difficult for my eldest son to travel back and forth to do the rituals… Yes, I have already discussed about it with my husband… he was against it at first but then he said if he dies first, he will leave it up to me, I think that’s the best. It won’t become a burden to our sons. The columbarium will solve the problem of the grave.(Saori, 61)

The second kind of burden was related to caregiving. Elderly Japanese parents have been utilizing formal care services as an important strategy to exempt their middle-aged children from filial care duty (Asai and Kameoka 2005; Kawakami and Son 2015). The respondents did not want to burden their children with long-term care, but they were also aware of the fact that along the road, they would need someone to provide them with some assistance. In order to remain independent for as long as possible, they took great care of their health, but if they fell sick, they would first turn to their spouses and then to formal-care services. While many wished to age-in-place, they were most afraid of becoming demented or bed-ridden. If they became incapable of taking care of themselves, then decision of whether or not to enter a nursing home would become an important shūkatsu decision to make. While some men said that they would start engaging in shūkatsu after they made their decisions to enter a nursing home, the women advocated planning and acting ahead.

Many respondents were also concerned about maintaining a good relationship with their children and their children’s spouses during discussions about caregiving. While daughters have continued to be the preferred caregivers of elderly parents (Knight and Traphagan 2003; Schultz Lee 2010), some female respondents in this study provided a different perspective. Kumiko was one of them:

Some mothers prefer to have their daughters taking care of them… well, that might be true to a certain extent, but not all daughters get along well with their own parents, and they also have to have their husbands agree with that. I have heard cases where daughters are stuck in between their husbands and parents… at this point of time, I don’t want to burden my children… so I will try my best to remain healthy and not become senile.(Kumiko, 71)

Kumiko had a son and two daughters. She had maintained a very intimate relationship with her daughters and son in-laws. However, if she became sick, she would ask her husband to take care of her instead of her daughters. “Once your daughter is married off, she has her own family; you can’t ask too much”, Kumiko stated this while nodding affirmatively. When asked about her daughter in-law, she was surprised and said that the idea of asking her daughter in-law had never crossed her mind, “Not in today’s Japan, no way!”.

The male respondents with unmarried daughters also indicated that they were interested in other options. Takashi had a daughter who lived with him and his wife. She was in her 40s, and she had no intention to get married. When asked if he was happy about his daughter living with him, he showed ambivalence.

I am happy that she lives with me, but if we are talking about having her take care of us, then I don’t feel relieved at all… when I talk to my wife about our shūkatsu, we don’t want to be a burden to our children, especially my daughter.(Takashi, 70)

Kumiko and Takashi shared a common trait. Although they did not see the urgency of beginning their shūkatsu right away and even though they would try to stay healthy and be independent, they would “think of what to do” and would make plans when they experienced changes in their current lifestyle.

However, how about the sons? What if the sons wanted to take care of their parents? “Unless my daughter in-law wholeheartedly welcomes us”, or “unless my daughter in-law agrees to it”, were responses from the majority of them. Although the findings seemed to show that they did not want to take their daughter or daughter in-laws for granted, compared to men, the female respondents were more inclined to do as much shūkatsu as possible when necessary so that they could minimize the burden on their children. While the concept of not burdening one’s children illustrates a tacit interdependence between parents and children, engagement in shūkatsu reveals the efforts the respondents put in to making sure that a harmonious relationship can be maintained between the parents and their children/children’s spouses and among siblings.

3.4. Time and Place and Lifespan Development: Expectations from Children

The principle of historical time and place provides an explanation of how an individual’s lifespan development is shaped by sociohistorical context. In the study of aging, the ie ideology is one of the most important concepts that influences the norms of a Japanese family. The Japanese are caught between changing norms as Japan undergoes rapid demographic and sociocultural transformation. Some of the respondents were born and raised during the war, some were baby boomers, and the rest of them were raised during a time when Japan was enjoying high economic growth and success. Everyone lives a life with different depths and forms of social relationships, and they thus have different expectations towards their children. Japanese people who were born after the war have different beliefs from those of the prewar generation. Compared to the prewar generation, which stressed on being loyal to their families and to the state, the postwar generation was taught differently due to the revised postwar education philosophy (Traphagan 2000). Accordingly, the education reform has weakened the idea of filial piety because children are taught to take care of their parents within their physical and financial ability (Maeda 2004). Nevertheless, some of the male respondents continued to have strong beliefs in family values from their childhood experiences despite social transformations. Conversely, the female respondents, especially those who had enjoyed greater freedom in family lives, emphasized intergenerational independence and the values of privacy.

Regardless of the unanimous emphasis of not wanting to burden their children, more than half of the male respondents had not begun or thought about shūkatsu yet. Everyone had different reasons for not engaging in shūkatsu—some had not retired, while some insisted that they were still too healthy to talk about death. A common trait was clearly visible among those who were born the eldest son and those who were not but who had taken over the duties of the eldest son to take care of their parents. All of them seemed to have unspoken expectations towards their sons.

I didn’t tell my son what he has to do as the eldest son. When I was a child, I was often told by my parents and my relatives that I was the eldest son and the things I’m supposed to do. It wasn’t a nice feeling. I didn’t want my son to feel that way. That’s why I have never told him about things like that. But you see, I don’t have to purposely say it out because I can feel that he’s conscious of being the eldest son…(Osamu, 72)

No one told me what I should or should not do, but my father is the eldest son, and we lived with our grandparents… maybe it is the influence from my father; when I saw how my father had taken care of his parents, I thought I had to do the same. I try not to expect anything from my son, not in a conscious manner, but maybe, maybe I do expect something from him.(Kazuhiko, 61)

Both Osamu and Kazuhiko grew up in a traditional three generation family. They saw how their fathers had fulfilled their obligations as the eldest sons and how their mothers had provided care to their grandparents. When Osamu built his own house, he prepared a room for his parents. After his father passed on, his mother continued living with him until she went to live in a nursing home when she was 93 years old. Osamu visited his mother weekly until she passed on at the age of 101. As for Kazuhiko, his 90-year-old mother still lived by herself. Kazuhiko checked on her every Saturday. Both said that performing the duties of an eldest son came naturally to them. Whether or not the eldest sons were instilled with the thought of their duties or obligations, the narratives show that the abolished ie ideology has continued to inform family practices, norms, and probably the hope of a reciprocal relationship between parents and children.

While some of the male respondents adopted a wait-and-see approach for shūkatsu, the female respondents, on the other hand, believed that they should try not to impose any expectations on their children. An active and outspoken Akemi, who considered herself a proactive planner, was firm in her response.

I won’t discuss my old age with my children. You see, we are living apart and leading our own lives freely; there’s no reason to expect help when you become old… because most of us don’t live with our children… so even if we don’t want to go to a nursing home, we might have to go to one… you have to prepare a sum of money for that. You have to plan for it.(Akemi, 66)

Akemi’s husband was born the second son, and she had never lived with her in-laws. Nevertheless, Akemi had to bear the responsibility of taking care of her 88-year-old mother because her sister in-law left the family house immediately after the death of her husband, who was Akemi’s only brother. Akemi did not blame her sister in-law; her mother was a difficult person to get along with. “I have to look after my mother… there’s nothing I can do about it… I can’t dump her”. Akemi sighed deeply. She tried commuting to her mother’s house for a while, but it was difficult because her mother was becoming blind and needed special care. “I was so relieved after I found her a nursing home… you see, you have to start planning when you’re in good health or when you’re not too old… then you won’t burden your family”, she nodded over and over again.

3.5. Timing: The Shock from the Loss of a Spouse

The life course perspective acknowledges the significance of the timing of lives in terms of chronological age (Hutchison 2010). The thought of not wanting to burden one’s loved ones was repeatedly mentioned as being the main reason behind participating in shūkatsu, but the findings suggested that the thought itself does not necessarily provoke the act of shūkatsu. Over the course of one’s life, some unforeseen life events become turning points in one’s life and alter a person’s life path (Hareven and Masaoka 1988), for instance, catastrophes, the death of loved ones, and serious illness. Many of the respondents expected death to happen in chronological order. As lives are linked, the death of a person may cause a disruption or a discontinuity in the transition of another person’s life, such as a change in behavior or attitude. In terms of the death of loved ones, the demise of a spouse has been found to be the most stressful event in one’s life (Stroebe and Stroebe 1987). In our study, we observed that the death of a spouse was a major turning point, especially for men. Two widowers shared similar experiences that triggered their shūkatsu. Makato, whose wife died when he was 59, and Shoji, whose wife died when he was 74, made the following comments.

Men usually don’t think about their wives dying before them; we normally think men will die before their wives, and their afterlife matters will be done by their wives and children… men don’t even know where they have put their own things. In my case, my wife died first, so there will be no one to do many things for me, the most important person in my life died before me. That’s really very shocking… I have experienced death of three loved ones, my wife, and my parents. I have seen death, and I know death…. we all die, and if you know you will die, you have to be prepared for it. Now I am on my own, I began to think of my own shūkatsu, and how I should live the rest of my life.(Makoto, 67)

I first heard the term shūkatsu from TV, on NHK programs… but when my wife was alive, I didn’t really think about it. I thought it was too early to think about shūkatsu, but in reality, my wife has passed on, and therefore, I have to think about it because I am the one left behind. After my wife’s third death anniversary… I thought I have to get prepared… let me show you, this is just part of my ending-note, some are at home… I have to make it easy for my son to understand.(Shoji, 77)

The loss of a wife is an unforeseen life event for men, as a woman usually live about 7 years longer on average (Kumagai 2016). A majority of the male respondents expected their wives to live longer than them and to play the role as their primary caregivers. They also assumed that they had either their wives or children to sort out whatever they would leave behind after they passed on. They believed that their wives would take care of any unfinished family matters. On the other hand, although the impact of the loss of a spouse was similarly devastating when some widows talked about their husband’s passing, the death of husband was also seen by the female respondents as a transition to widowhood in later life, stating that “it’s something that can’t be helped” because many were prepared to live longer lives than their husbands. As the narratives showed, most men did not see the immediate need for shūkatsu as long as they had their wives taking care of the house.

4. Concluding Remarks

Through an exploration of shūkatsu from the life course perspective, this paper has shown that older Japanese citizens responded to changing demographic and sociocultural transitions through active planning and preparation. Consistent with the literature (Koyano 1996; Suzuki 2018), the respondents in our study represent a group of healthier and more active older Japanese people who are found to be more psychologically, functionally, socially, and economically more independent than previous generations. They prefer to be emotionally connected than physically dependent on their adult children (Long et al. 2009; Sodei 1995). Many of the respondents, especially the women, were happy that they were keeping a comfortable distance with their children. Some used the metaphor of sūpu no samenai kyori, a distance which does not allow the soup to get cold, to reflect upon their desire to maintain their independence yet closeness with their children through a distance of “togetherness and separation” (Kweon 1997, p. 372).

Social norms and experiences have an influence over how men and women plan for their later life. After working hard for decades to provide for their families, older men may want to relax and enjoy their lives, trusting that they can rely on their wives (Sone and Thang 2020). Nevertheless, our study shows that men become more conscious about not wanting to burden their children, triggering them to begin shūkatsu after the death of their spouses.

By actively contemplating their shūkatsu along with a strong concern to reduce the level of physical, emotional, and financial burden on their loved ones as much as possible, most respondents perceived good old age as being able to live healthy, remain active, have one’s personal matters sorted out if possible, and a quick death with minimal physical suffering at the end. Hence, we can similarly regard older Japanese who practice shūkatsu as practicing “active aging” when they try to maintain autonomy while making decisions, living independently, and striving to live a longer healthy life expectancy. In a super-aged Japan, shūkatsu may be a vital strategy that not only ensures a better quality of life for the older population and their children but one that also contributes to an individual’s sense of usefulness and satisfaction, as they are actively involved in the planning and management of their own later and afterlife choices.

Finally, the research has some limitations. While this paper unveiled the stories of many married couples and the collective decisions they made with their spouses or children, we did not have a large enough sample to make the experiences of single individuals living by themselves more visible. Additionally, as the data were generated from independent, cognitively, physically healthy and relatively financially stable older Japanese people, this study lacked voices from older adults who were less healthy and financially less well-off.

Future research can be extended to understand a broader group of older adults, for instance, to study single never-married or divorced individuals with different aging challenges and their priorities on shūkatsu. As the study only focuses on city dwellers, a larger sample that includes individuals from non-urban areas may reveal more diversified cultural practices and norms that could add more depth to the research In the study, a few respondents also mentioned the use of the Internet as a platform through which they could record their personal information and last wishes. It would be interesting to explore how information technology would impact shūkatsu in an increasingly digitalized Japanese society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.H.C. and L.L.T.; methodology: H.H.C.; formal analysis: H.H.C.; data curation: H.H.C.; writing—original draft preparation: H.H.C.; writing—review and editing: H.H.C. and L.L.T.; project administrator: H.H.C. and L.L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the NUS Institutional Review Board of National University of Singapore (NUS-IRB Ref No.: S-19-103, date of approval: 9 April 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The term shūkatsu, when translated literally, means “the activities” one engages in preparation of one’s final life stage. |

| 2 | “A family grave” refers to a grave which one inherits from the parents. The eldest son usually inherits the family grave. For those who are not born the eldest son, they do not own a grave and thus they need to purchase one. |

| 3 | The writing of an “ending-note” is also sometimes used interchangeably with the expression “shūkatsu”. Instead of a legally binding will, in this case, an “ending-note” is a book for jotting down whatever information and last wishes that an individual wishes to convey to the immediate families or to someone who will be in charge of settling the individual’s personal matters after his or her demise. |

| 4 | “Shūkatsu” ni iyoku 8 wari kosu dejitaru ihin no nayami mo: Dokusha ankēto [80% inclined towards doing shūkatsu, digital possession another source of worry: Survey from readers].” (Nikkei Style 2017), accessed 18 Decemmber 2021, https://style.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO20645800R00C17A9PPD000. |

| 5 | The respondents were classified as “middle class” based on their occupation. Out of the 40 respondents, about 78% were salarymen (16 male respondents and 15 female respondents’ spouses). The others included civil servants, lawyers, and small business owners. Gence, most of the respondents were considered middle-class, which is in line with the general middle-class model in the 1970s, where men who were in active employment as salarymen were classified as belonging to the middle-class (Chiavacci 2008). |

| 6 | An event organized annually by funeral business vendors in different parts of Japan, where workshops, information, and services related to before and afterlife matters are offered. |

| 7 | Shūkatsu councilors are trained by Shūkatsu Associations to provide consultation to the general public on matters such as the sorting out of personal affairs and effects, inheritance, and preparation of funerals. Most “Shūkatsu Associations” are General Incorporated Associations or NPOs. Recently, there have also been “Digital Shūkatsu Associations” that have been introduced that give advice on how to prepare shūkatsu online. |

| 8 | In 2019, there were six cities that offered shūkatsu services in Japan—Kita-Nagoya city in the Aichi Prefecture; Takasago city in the Hyogo Prefecture; Chiba city in the Chiba Prefecture; and Ayase city, Yamato city, and Yokosuka city in the Kanagawa Prefecture. They specifically provide support to older people who live alone or who have lost touch with their kin. In these cities, older people are encouraged to have their emergency contacts registered with the city offices. The city offices also provide personalized services such as recommending funeral homes to older people who want to make advance arrangements of their own afterlife matters. |

| 9 | Haka-jimai refers to the act of dismantling a grave. There are many reasons for doing this: when no one succeeds the grave or when the grave is too far away for family to visit or to perform the seasonal rituals. To do a haka-jimai, the ashes of those buried inside the grave will be removed, and the ashes will be moved to the columbarium. |

| 10 | Eitai-kuyōbo literally means eternally worshipped graves. Basically, there are two types of “eitai” (eternal) graves. A person can choose to either have their ashes buried in a grave or placed in an urn in a columbarium. These grave sites are usually run by temples, religious, or non-religious organizations. A person before death, or the family member of the deceased, pays the grave operator to take care of the grave and to perform the mortuary rituals for a designated period of time, most commonly, for 17, 33, or 50 years (Refer to Tsuji (2018, p. 19). In this study, when the respondents mentioned eitai-kuyō, they referred to having their ashes buried in an urn and to entrust the columbarium to provide posthumous care. |

References

- Asai, Masayuki O., and Velma A. Kameoka. 2005. The influence of Sekentei on family caregiving and underutilization of social services among Japanese caregivers. Social Work 50: 111–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson, Vern L., and Katherine R. Allen. 2009. The Life Course Perspective Applied to Families over Time. In Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods. Boston: Springer, pp. 469–504. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Kathy, Sandra L. Reynolds, and Hana Osman. 2008. Factors associated with advance care planning among older adults in southwest Florida. Journal of Applied Gerontology 27: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, John. 2004. Introduction: Death issues in 21st century Japan. Mortality 9: 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Patrick, and Sarah Vickerstaff. 2011. Health subjectivities and labor market participation: Pessimism and older workers’ attitudes and narratives around retirement in the United Kingdom. Research on Aging 33: 529–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office Japan. 2018. Annual Report on the Aging Society. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/2018/pdf/c1-1.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Chiavacci, David. 2008. From class struggle to general middle-class society to divided society: Societal models of inequality in postwar Japan. Social Science Japan Journal 11: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, John W. 2012. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, Margaret A., Candace L. Kemp, Susan French, Amiram Gafni, Anju Joshi, Carolyn J. Rosenthal, and Sharon Davies. 2004. Reflexive planning for later life. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement 23: S71–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, Glen H., Jr., and Monica Kirkpatrick Johnson. 2003. The life course and aging: Challenges, lessons, and new directions. In Invitation to the Life Course: Toward New Understandings of Later Life. Edited by Richard Settersten Jr. Amityville: Baywood, pp. 49–81. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, Glen. H. 1998. The Life Course as Developmental Theory. Child Development 69: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hareven, Tamara K., and Kanji Masaoka. 1988. Turning points and transitions: Perceptions of the life course. Journal of Family History 13: 271–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooyman, Nancy R., and H. Asuman Kiyak. 2002. Social Gerontology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, 6th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, Elizabeth D. 2010. A life course perspective. In Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course. Edited by Elizabeth D. Hutchison. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs-Lawson, Joy M., Douglas A. Hershey, and Kirstan A. Neukam. 2004. Gender differences in factors that influence time spent planning for retirement. Journal of Women & Aging 16: 55–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, Atsuko, and Juyeon Son. 2015. “I Don’t Want to be a Burden”: Japanese Immigrant Acculturation and Their Attitudes Toward Non-Family-Based Elder Care. Ageing International 40: 262–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Satsuki. 2003. Finding common ground: Family, gender, and burial in contemporary Japan. In Demographic Change and the Family in Japan’s Aging Society. Edited by John W. Traphagan and John Knight. Albany: SUNY Press, pp. 125–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kawano, Satsuki. 2004a. Pre-funerals in contemporary Japan: The making of a new ceremony of later life among aging Japanese. Ethnology 43: 155–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Satsuki. 2004b. Scattering ashes of the family dead: Memorial activity among the bereaved in contemporary Japan. Ethnology 43: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Yuka, and Takatoshi Ando. 2018. Masumedia ni okeru shūkatsu no toraekata to sono hensen [The view point of Japanese mass media for Shūkatsu]. Gijutsu Manejimento Kenkyū [The Technical Management Study] 17: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, John, and John W. Traphagan. 2003. The study of the family in Japan: Integrating anthropological and demographic approaches. In Demographic Change and the Family in Japan’s Aging Society. Edited by John W. Traphagan and John Knight. Albany: SUNY Press, pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kornadt, Anna E., and Klaus Rothermund. 2014. Preparation for old age in different life domains: Dimensions and age differences. International Journal of Behavioral Development 38: 228–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyano, Wataru. 1996. Filial Piety and Intergenerational Solidarity in Japan. Australian Journal on Ageing 15: 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, Fumie. 2016. Family Issues on Marriage, Divorce, and Older Adults in Japan. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto Institute of Research. 2017. Shūkatsu Nikansuru Ishiki Chosa [Attitude Survey on Shūkatsu]. Available online: https://dik.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/p_syukatsu_1.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Kweon, Sug-In. 1997. Sūpu no samenai kyori (A distance which does not allow the soup to get cold): The Search for an Ideal in the Care of the Elderly in Contemporary Japan. In Aging: Asian Concepts and Experiences Past and Present. Edited by Susanne Formanek and Sepp Linhart. Wien: Osterreichischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften, pp. 369–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lassen, Aske Juul, and Michael Christian Andersen. 2016. What enhancement techniques suggest about the good death. Culture Unbound 8: 104–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Susan O., Ruth Campbell, and Chie Nishimura. 2009. Does it matter who cares? A comparison of daughters versus daughters-in-law in Japanese elder care. Social Science Japan Journal 12: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Daisaku. 2004. Societal filial piety has made traditional individual filial piety much less important in contemporary Japan. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 4: S74–S76. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsubishi UFJ Research and Consulting. 2012. Anshin to Shinrai no aru “Raifuendingusutēji”no Sōshutsu ni Muketa Chōsa Kenkyū Jigyō Hōkokusho [A Report on Creating a Trusted and Reliable “Life-Ending Stage”]. Available online: https:www.meti.go.jp/meti_lib/report/2012fy/E002295.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Mladenova, Dorothea. 2020. Optimizing one’s own death: The Shūkatsu industry and the enterprising self in a hyper-aged society. Contemporary Japan 32: 103–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, Miriam S., and Sidney Z. Moss. 1984. The impact of parental death on middle aged children. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 14: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkei Style. 2017. Shūkatsu” ni iyoku 8 wari kosu dejitaru ihin no nayami mo: Dokusha ankēto [80% inclined towards doing shūkatsu, Digital Possession Another Source of Worry: Survey from Readers]. Available online: https://style.nikkei.com/article/DGXMZO20645800R00C17A9PPD000 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Phillipson, Chris, and Jason L. Powell. 2004. Risk, social welfare and old age. In Old Age and Agency. Edited by Emmanuelle Tulle. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, Martin, and Silvia Sörensen. 2002. Psychological outcomes of preparation for future care needs. Journal of Applied Gerontology 21: 452–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, Richard, and Allison Alexy. 2011. Continuity and change in Japanese homes and families. In Home and Family in Japan: Continuity and Transformation. Edited by Richard Ronald and Allison Alexy. London: Routledge, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Samsi, Kritika, and Jill Manthorpe. 2011. ‘I live for today’: A qualitative study investigating older people’s attitudes to advance planning. Health & Social Care in the Community 19: 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz Lee, Kristen. 2010. Gender, care work, and the complexity of family membership in Japan. Gender & Society 24: 647–71. [Google Scholar]

- Skarborn, Marianne, and Richard Nicki. 1996. Worry among Canadian seniors. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 43: 169–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodei, Takako. 1995. Care of the elderly: A women’s issue. In Japanese Women: New Feminist Perspectives on the Past, Present, and Future. Edited by Kumiko Fujimura-Fanselow and Atsuko Kameda. New York: The Feminist Press, pp. 213–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sone, Sachiko, and Leng Leng Thang. 2020. Staying till the End?: Japanese Later-Life Migrants and Belonging in Western Australia. Japanese Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications [MIC]. 2021. Statistical Handbook of Japan 2021. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/c0117.html (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Stroebe, Wolfgang, and Margaret S. Stroebe. 1987. Bereavement and Health: The Psychological and Physical Consequences of Partner Loss. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Hikaru. 1998. Japanese death rituals in transit: From household ancestors to beloved antecedents. Journal of Contemporary Religion 13: 171–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Hikaru. 2002. The Price of Death: The Funeral Industry in Contemporary Japan. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Hikaru. 2013. Death and Dying in Contemporary Japan. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Takao. 2018. Health status of older adults living in the community in Japan: Recent changes and significance in the super-aged society. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 18: 667–77. [Google Scholar]

- Traphagan, John W. 2000. Taming Oblivion: Aging Bodies and the Fear of Senility in Japan. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, Yohko. 2011. Rites of passage to death and afterlife in Japan. Generations 35: 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, Yohko. 2018. Evolving Mortuary Rituals in Contemporary Japan. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Death. Edited by Antonius C.G.M. Robben. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Chizuko. 2009. The Modern Family in Japan: Its Rise and Fall. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wada, Shuichi. 1995. The status and image of the elderly in Japan. In Images of Aging. Edited by Mike Featherstone and Andrew Wernick. London: Routledge, pp. 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Alan. 2002. A strategy for active ageing. International Social Security Review 55: 121–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2002. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Geneva: WHO Ageing and the Life Course Section. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).