Are Working Children in Developing Countries Hidden Victims of Pandemics?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rationale and Contribution of the Study

3. Definition of Child Labour

4. Studies on Child Labour and Previous Non-COVID-19 Pandemics in Developing Countries

5. Studies on COVID-19 and Child Labour in Developing Countries

6. Discussion and Suggestions

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Suggestions for Future Research

6.3. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abimanyi-Ochom, Julie, Brett Inder, Bruce Hollingsworth, and Paula Lorgelly. 2017. Invisible work: Child work in households with a person living with HIV/AIDS in Central Uganda. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance 14: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achdut, Netta, and Tehila Refaeli. 2020. Unemployment and Psychological Distress among Young People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Psychological Resources and Risk Factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admassie, Assefa. 2002. Exploring the High Incidence of Child Labor in Sub—Saharan Africa. Africa Development Review 14: 251–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, Abdul, Mitu Chowdhury, Yvonee Parry, and Eileen Willis. 2021. Urban child labor in Bangladesh: Determinants and its possible impacts on health and education. Social Sciences 10: 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, Abdul, Yvonne Parry, and Eileen Willis. 2020. Spillover trends of child labor during the Coronavirus crisis—An unnoticed wake-up call. Frontiers in Public Health 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Imam M., Shahina Amin, and Janet M. Rives. 2015. A Double-hurdle analysis of the Gender Earnings Gap for Working Children in Bangladesh. The Journal of Developing Areas 49: 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Zakiul M. 2021. Is population density a risk factor for communicable diseases like COVID-19? A case of Bangladesh. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health 6: 1010539521998858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Amjad, Mumtaz Ahmed, and Nazia Hassan. 2020. Socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from rural mountain community in Pakistan. Journal of Public Affairs 4: e2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneja, Ranjan, and Vaishali Ahuja. 2020. An assessment of socioeconomic impact of COVID-19 pandemic in India. Journal of Public Affairs 21: e2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, Richard, and Laura B. Nellums. 2020. COVID-19: Compounding the health—Related harms of human trafficking. EClinicalMedicine 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, Abay, and Joachim von Braun. 2004. Is consumption insured against illness? Evidence on vulnerability of households to health shocks in rural Ethiopia. Economic Development and Cultural Change 53: 115–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, Ragui, Deborah Levison, and Nadia Zibani. 2010. The effect of domestic work on girls’ schooling: Evidence from Egypt. Feminist Economics 16: 79–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataguba, Ochega A., and John E. Ataguba. 2020. Social determinants of health: The role of effective communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Global Health Action 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attanasio, Orazio, Emla Fitzsimons, Ana Gomez, Diana Lopez, Costas Meghir, and Alice Mesnard. 2010. Child education and work choices in the presence of a conditional cash transfer programme in rural Colombia. Economic Development and Cultural Change 58: 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, Saeed, Muazzam Nasrullah, and Kristin J. Cummings. 2010. Health hazards, injury problems and workplace conditions of carpet-weaving children in three districts of Punjab, Pakistan. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 16: 113–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamgboye, Ebun L., Jesutofunmi A. Omiye, Oluwasegun J. Afolaranmi, Mogamat Razeen Davids, Elliot Koranteng Tannor, Shoyab Wadee, Abdou Niang, Anthony Were, and Saraladevi Naicker. 2020. COVID-19 Pandemic: Is Africa different? Journal of the National Medical Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, Kaushik. 1999. Child labor: Causes, consequenses and cure, with remarks on International Labor Standards. Journal of Economic Literature 37: 1083–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, Kaushik. 2002. A Note on the Multiple General Equilibria with Child Labor. Economics Letters 74: 301–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, Kaushik, Sanghamitra Das, and Bhaskar Dutta. 2010. Child labor and household wealth: Theory and empirical evidence of an invented-U. Journal of Development Economics 91: 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beegle, Kathleen, Rajeev Dehejia, and Roberta Gatti. 2003. Child Labor, Income Shocks and Access to Credit. Policy Research Working Paper, No. 3075. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/18222/wps3075.pdf?sequence=1andisAllowed=y (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Beegle, Kathleen, Rajeev Dehejia, and Roberta Gatti. 2006. Child labor, crop shocks and credit constraints. Journal of Development Economics 81: 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beegle, Kathleen, Rajeev Dehejia, and Roberta Gatti. 2009. Why Should we Care about Child Labor? The Education, Labor Market and Health Consequences of Child Labor. The Journal of Human Resources 44: 871–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérenger, Valérie, and Audrey Verdier-Chouchane. 2016. Child Labour and Schooling in South Sudan and Sudan: Is there a Gender Preference? African Development Review 28: 177–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, Choon-Looi, Christopher Brasher, Edson Chikumba, Robert McDougall, Jannicke Mellin-Olsen, and Angela Enright. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic: Effects on low and middle-income countries. Anesthesia and Analgesia 131: 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonke, Jens. 2010. Children’s housework. Are girls more active than boys? International Journal of Time Use Research 7: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortz, Pablo, Gabriel Michelena, and Fernando Toledo. 2020. A gathering of storms: The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the balance of payments of emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). International Journal of Political Economy 49: 318–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Sebastian. 2006. Core Labour Standards and FDI: Friends or foes? The Case of Child Labour. Review of World Economics 142: 765–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Samantha M., Jenalee R. Doom, Stephanie Lechuga-Peña, Sarah Enos Watamura, and Tiffany Koppels. 2020. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse and Neglect 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brum, Matias, and Mauricio De Rosa. 2021. Too little but not too late: Nowcasting poverty and cash transfers’ incidents during COVID-19’ crisis. World Development 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, Matthias, and Sebastian Braun. 2004. Export structure, FDI and child labor. Journal of Economic Integration 19: 804–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Caesar-Leo, Michaela. 1999. Child labour: The most visible type of child abuse and neglect in India. Child Abuse Review 8: 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Sydney, Carlo Cicero Oneto, Manav Preet Singh Saini, Nona Attaran, Nora Makansi, Raissa Passos Dos Santos, Shilni Pukuma, and Franco A. Carnevale. 2021. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children: An ethical analysis with a global-child lens. Global Studies of Childhood 11: 105–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, Sudharshan, and Helena S. Nielsen. 2001. Child Labor in Africa: A Comparative Study. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 575: 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, Sarbajit. 2011. Labor Market Reform and Incidence of Child Labor in a Developing Economy. Economic Modelling 28: 1923–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, Sarbajit, and Jayanta K. Dwibedi. 2016. Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Child Labor. Review of Development Economics 21: 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, Geeta. 2020. Covid-19 disrupts India’s March towards making her children thrive and transform. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 10: 184–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwudeh, Okechukwu, and Akpovire Oduaran. 2021. Liminality and child labour: Experiences of school aged working children with implications for community education in Africa. Social Sciences 10: 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Gabriel W., André Carraro, Felipe. G. Ribeiro, and Mariane F. Borba. 2020. The Impact of Child Labor Eradication Programs in Brazil. The Journal of Developing Areas 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, Kenneth, Robert Fairlie, and Huanan Xu. 2020. Early evidence of the impacts of COVID-19 on minority unemployment. Journal of Public Economics 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, Angela, Alyson Hillis, Shubhendra Man Shrestha, and Babu Kaji Shrestha. 2020. Bricks in the wall: A review of the issues that affect children of in-country seasonal migrant workers in the bricks kilns of Nepal. Geography Compass 14: e12547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, Angela, Alyson Hillis, Shubhendra Man Shrestha, and Babu Kaji Shrestha. 2021. Breaking the child labour cycle through education: Issues and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children of in-country seasonal migrant workers in the brick kilns of Nepal. Children’s Geographies, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammert, Ana, and Jose Galdo. 2013. Child labor variation by type of respondent: Evidence from a large-scale study. World Development 51: 207–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matos, Dihogo Gama, Felipe J. Aidar, Paulo Francisco de Almeida-Neto, Osvaldo Costa Moreira, Raphael Fabrício de Souza, Anderson Carlos Marçal, Lucas Soares Marcucci-Barbosa, Francisco de Assis Martins Júnior, Lazaro Fernandes Lobo, Jymmys Lopes dos Santos, and et al. 2020. The impact of measures recommended by the government to limit the spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19) on physical activity levels, quality of life and mental health of Brazilians. Sustainability 12: 9072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, Sibnath. 2005. Child abuse and neglect in a metropolitan city: A qualitative study of migrant child labour in Soutrh Kolkata. Social Change 35: 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, Yacouba, Alex Etienne, and Farhad Mehran. 2013. Global Child Labour Trends 2008 to 2012, ILO, International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC). Available online: file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/Global_Child_Labour_Trends_2008-2012_EN_Web%20(1).pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Dillon, Andrew, Elena Bardasi, Kathleen Beegle, and Pieter Serneels. 2012. Explaining variation in child labor statistics. Journal of Development Economics 98: 136–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Pamela K., David B. Douglas, Daniel C. Harrigan, and Kathleen M. Douglas. 2009. Preparing for pandemic influenza and its aftermath: Mental health issues considered. International Journal of Emergence Mental Health 11: 137–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, Christelle. 2020. Productivity shocks and child labor: The role of credit and agricultural labor markets. Economic Development and Cultural Change 68: 763–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duryea, Suzanne, David Lam, and Deborah Levison. 2007. Effects of economic shocks in children’s employment and schooling in Brazil. Journal of Development Economics 84: 188–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, Eric V., and Maheshwor Shrestha. 2014. You get what you pay for: Schooling incentives and child labor. Journal of Development Economics 111: 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, Eric. V., and Nina Pavcnik. 2005. Child labor in the global economy. Journal of Economic Perspectives 19: 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Ruth. 2012. Sibling caringscapes: Time-space practices of caring within youth-headed households in Tanzania and Uganda. Geoforum 4: 824–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetuga, Bolanle. M., Fidelis O. Njokama, and Adebiyi O. Olowu. 2005. Prevalence, Types and Demographic Features of Child Labour among School Children in Nigeria. BMC International Health and Human Rights 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, Vanessa C., and Grace Iarocci. 2020. Child and family outcomes following pandemics: A systematic review and recommendation on COVID-19 policies. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 45: 1124–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, Debajyoti, Jonathan A. Bernstein, and Tesfaye Mersha. 2020a. COVID-19 pandemic: The African paradox. Journal of Global Health 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, Ritwik, Mahua J. Dubey, Subhankar Chatterjee, and Souvik Dubey. 2020b. Impact of COVID-19 on children: Special focus on the psychosocial aspect. Minerva Pediatrica 72: 226–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gicharu, Pauline, Bernard Mwaniki, Agnes Kubui, Loise Gichuhi, and Ruth W. Kahiga. 2015. Effect of HIV/AIDS on academic performance of preschool children in Kijabe location, Kiambu country, Kenya. International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology 2: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Philip S., Marinus H. van Ijzendoorn, and Edmund J. Sonuga-Barke. 2020. The implications of COVID-19 for the care of children living in residential institutions. Lancet Child Adolescent Health 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulas, Sofoklis, and Rigissa Megalokonomou. 2020. School attendance during a pandemic. Economic Letters 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, Jordan, and Nia Bodrick. 2017. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Section on International Child Health, Pediatrics 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, Jordan, Hanni Stoklosa, and Laura Murphy. 2020. The public health impact of coronavirus disease on human trafficking. Frontiers in Public Health 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, Beverly. 2004. Child labor and Africanist scholarship: A critical review. African Studies Review 47: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Sonia, and Manveen K. Jawanda. 2020. The impacts of COVID-19 on children. Acta Paediatrica 109: 2181–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson-Wright, Emily, Wendy Janssens, and Jacques van der Gaag. 2011. The inequitable impact oh health shocks on the uninsured in Namibia. Health Policy Plan 26: 142–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Romero, Roxana, and Mostak Ahamed. 2021. COVID-19 response needs to broaden financial inclusion to curb the rise in poverty. World Development 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haer, Roos. 2019. Children and armed conflict: Looking at the future and learning from the past. Third World Quarterly 40: 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, Andy, David Sanders, Uta Lehmann, Alexander K. Rowe, Joy E. Lawn, Steve Jan, Damian G. Walker, and Zulfiqar Bhutta. 2007. Achieving child survival goals: Potential contribution of community healthy workers. Lancet 369: 2121–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilson, Gavin. 2010. Child Labour in African Artisanal Mining Communities: Experiences from Northern Ghana. Development and Change 41: 445–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado, Daniel, Isidro Maya-Jariego, Ignacio Ramos, Jorge Palacio, Oscar Oviedo-Trespalacios, Vanessa Romero-Mendoza, and José Amar. 2014. Impact of Child Labor on Academic Performance: Evidence from the Program “Edúcame Primero Colombia”. International Journal of Educational Development 34: 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, Martin. 2017. The ghost of pandemics past: Revisiting two centuries of influenza in Sweden. Medical Humanities 43: 141–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, Janine, and Jeroen Smits. 2015. Keeping Children in School: Effects on Household and Context Characteristics on School Dropout in 363 Districts of 30 Developing Countries. SAGE Open 5: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. 1973. C138—Minimum Age Convention. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ilo_code:C138 (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- ILO. 2010. Study on the Reintegration of Children Formerly Associated with Armed Forces and Groups through Informal Apprenticeship. Case Studies of Korhogo (Ivory Coast) and Bunia (Democratic Republic of Congo). Available online: file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/Study_reintegration_children_associated_armed_forces_case_study_EN%20(1).pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- ILO. 2011. SCREAM: A Special Module on Child Labour and Armed Conflict. Available online: file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/SCREAM_Armed_Conflict_Module_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- ILO/IPEC. 2021. What Is Child Labor. Defining Child Labor. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ipec/facts/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- ILO/UNICEF. 2020. COVID-19 and Child Labour: A Time of Crisis, a Time to Act. Briefing Paper. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/70261/file/COVID-19-and-Child-labour-2020.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Islam, Asadul, and Pushkar Maitra. 2012. Health shocks and consumption smoothing in rural households: Does microcredit have a role to play? Journal of Development Economics 97: 232–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarey, Saqib, and Sajal Lahiri. 2002. Will Trade Sabctions Reduce Child Labour? The Role of Credit Markets. Journal of Development Economics 68: 137–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentsch, Birgit, and Brigitte Schnock. 2020. Child welfare in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic—Emerging evidence from Germany. Child Abuse and Neglect 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansiime, Monica K., Justice A. Tambo, Idah Mugambi, Mary Bundi, Augustine Kara, and Charles Owuor. 2021. COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Development 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Navpreet, and Roger W. Byard. 2021. Prevalence and potential consequences of child labour in India and the possible impact of COVID-19—A contemporary overview. Medicine Science and the Law. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kea, Pamela. 2007. Girl Farm Labour and Double-shift Schooling in The Gambia: The Paradox of Development Intervention. Canadian Journal of African Studies 41: 258–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kechagia, Polyxeni, and Theodore Metaxas. 2018. Sixty Years of FDI Empirical Research: Review, Comparison and Critique. The Journal of Developing Areas 52: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Chae-Young. 2009. Is Combining Child Labour and Schoold Education the Right Approach? Investigating the Cambodian Case. International Journal of Educational Development 29: 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluttz, Jenalee. 2015. Reevaluating the relationship between education and child labour using the capabilities approach: Policy and implications for inequality in Cambodia. Theory and Research in Education 13: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucera, David. 2002. Core Labour Standards and Foreign Direct Investment. International Labour Review 141: 31–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Alok, and Najmus Saqib. 2017. School Abseeintism and Child Labor in Rural Banghladesh. The Journal of Developing Areas 51: 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumate, Jesús, Jaime Sepulveda, and Gonzalo Gultierrez. 1998. Cholera epidemiology in Latin America and perspectives for eradication. Bulletin de l’ Institut Pasteur 94: 217–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larmar, Stephen, Merina Sunuwar, Helen Sherpa, Roopshree Joshi, and Lucy P. Jordan. 2020. Strengthening community engagement in Nepal during COVID-19: Community-Based training and development to reduce child labour. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development 31: 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Seoyeon. 2021. An exploratory study on COVID-19 and the Rights of Children based on Keyword Network Analysis. Research Square. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinberger-Jabari, Andrea, David L. Parket, and Charles Oberg. 2005. Chidl labor, gender, and health. Public Health Reports 120: 642–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levison, Deborah, and Karine Moe. 1998. Household work as a deterrent to schooling: An analysis of adolescent girls in Peru. The Journal of Developing Areas 32: 339–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lieten, Georges K. 2011. Hazardous Child Labour in Latin America. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugalla, Joe L., and Huruma L. Sigalla. 2010. Child labour in the Era of HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A case study of Tanzania. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 35: 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, John, Vidiya Sathananthan, Thomas Griffiths, Zahir Kanjee, Avi Kenny, Nicholas Gordon, Gaurab Basu, Dale Battistoli, Lorenzo Dorr, Breeanna Lorenzen, and et al. 2016. Facility-based delivery during the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in rural Liberia: Analysis from a cross-sectional, population-based household survey. PLoS Medicine 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maconachie, Roy, and Gavin Hilson. 2016. Re-thinking the Child Labor “problem” in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Sierra Leone’s Half Shovels. World Development 78: 136–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmod, Nik Ahmad Kamal Nik, Marhanum Che Mohd Salleh, Ashgar Ali Muhammad, and Azizah Mohd. 2016. A study on child labour as a form of child abuse in Malaysia. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity 6: 525–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoni, Munyaradzi. 2020. COVID-19 in Africa: Half a year later. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, Aberra, Michael W. Kifle, and Lemma Indrias. 2003. Child labor and associated problems in rural town in South West Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 17: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Garcia, Claudio A. 2018. Can benefits from Malaria eradication be increased? Evidence from Costa Rica. Economic Development and Cultural Change 66: 585–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Colonel J. 2010. A collaborative approach to meeting the psychosocial needs of children during an influenza pandemic. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing 15: 135–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naemabadi, Arezu, Heidar Sharafi, Paniz Shirmast, Hamidreza Karimi-Sari, Seyed Hoda Alavian, Farzaneh Padami, Mahdi Safiabadi, Seyed Ehsan Alavian, and Seyed Moayed Alavian. 2019. Prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV infections in working children of Afghan immigrants in two supporting centers in Thran and Alborz Provinces, Iran. Archives of Pediatric Infectious Diseasesm 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naufal, George, Michael Malcolm, and Vidya Diwakar. 2019. Armed conflict and child labor: Evidence from Iraq. Middle East Development Journal 11: 236–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngegba, Mohamed P., and David A. Mansaray. 2016. Perception of students on the impact of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) on the education system of Sierra Leone. International Journal of Advanced Biological Research 6: 119–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Huong T. T., Tham T. Nguyen, Vu A. T. Dam, Long H. Nguyen, Giang T. Vu, Huong L. T. Nguyen, Hien T. Nguyen, and Huong T. Le. 2020. COVID-19 employment crisis in Vietnam: Global issue, National solutions. Frontiers in Public Health 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, Maria, Zaid Alsafi, Catrin Sohrabi, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, Maliha Agha, and Riaz Agha. 2020. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery 78: 185–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyambedha, Eric O., Simiyu Wandibba, and Jens Aagaard-Hansen. 2003. Changing patterns of orphan care due to the HIV epidemic in western Kenya. Social Science and Medicine 57: 301–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, Lorretta D., and Kwabena Frimpong-Manso. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on children from poor families in Ghana and the role of welfare institutions. Journal of Children’s Services 15: 185–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, Anton, Oyelola A. Adegboye, Adeshina I. Adekunle, Kazi M. Rahman, Emma S. McBryde, and Damon P. Eisen. 2020. Economic Consequences of the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Need for Epidemic Preparedness. Frontiers in Public Health 8: 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattanaik, Ipsita P. 2021. Corona virus, child labour and imperfect market in India. EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Krijn. 2011. The crisis of youth in postwar Sierra Leone: Problem Solved? Africa Today 58: 128–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchoff, Jessie, Karen Austrian, Nandita Rajshekhar, Timothy Abuya, Beth Kangwana, Rhoune Ochako, James Benjamin Tidwell, Daniel Mwanga, Eva Muluve, Faith Mbushi, and et al. 2021. Gendered economic, social and health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation policies in Kenya: Evidence from a prospective cohort survey in Nairobi informal settlements. BMJ Open 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchoff, Jessie, Kim G. Santhya, Corinne White, Shilpi Rampal, Rajib Acharya, and Thoai D. Ngo. 2020. Gender specific differences in COVID-19 knowledge, behavior and health effects among adolescents and young adults in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India. PLoS ONE 15: e0244053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, Mathieu J., Ricardo Izurieta, Sharad S. Malavade, and Michael D. McDonald. 2012. Re-emergence of cholera in the Americas: Risks, susceptibility, and ecology. Journal of Global Infectious Diseases 4: 162–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Progga, Farhat T., Tanzil M. Shahria, Asma Arisha, and Minhaz Shanto. 2020. A deep learning based approach to child labour detection. Paper presented at 6th Information Technology International Seminar (ITIS), Surabaya, Indonesia, October 14–16; pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psacharopoulos, George. 1997. Child Labor versus Educational Attainment. Some evidence from Latin America. Journal of Population Economics 10: 377–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, Diane L., and Marc H. Bornstein. 2015. Is child labor a barrier to school enrollment in low- and middle-income countries? International Journal of Educational Development 41: 112–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnick, Diane L., and Marc H. Bornstein. 2016. Girls’ and boys’ labor and household chores in low- and middle-income countries. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 81: 104–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafferty, Yvonne. 2020. Promoting the welfare, protection and care of victims of child trafficking during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Journal of Children’s Services 15: 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, Shanti, Maria Harries, Rita Nathawad, Rosina Kyeremateng, Rajeev Seth, and Bob Lonne. 2020. Where do we go from here? A child rights-based response to COVID-19. BMJ Paediatrics Open 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaswamy, Sheila, and Shekhar Seshadri. 2020. Children on the brink: Risks for child protection, sexual abuse and related mental health problems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 62: S404–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravallion, Martin, and Quentin Wodon. 2000. Does child labour displace schooling? Evidence on behavioural responses to an enrollment subsidy. The Economic Journal 110: 158–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravens-Sieberer, Ulrike, Anne Kaman, Michael Erhart, Janine Devine, Robert Schlack, and Christiane Otto. 2021. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Ranjan. 2002. Determinants of Child Labour and Child Schooling in Ghana. Journal of African Economies 11: 561–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Ranjan, and Geoffrey Lancaster. 2005. The impact of children’s work on schooling: Multi-country evidence. International Labour Review 144: 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, Ravinder. 2009. The Child Labor in Developing Countries: A Challenge to Millennium Development Goals. Indus Journal of Management and Social Science 3: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rivarola Puntigliano, Andrés. 2020. Pandemics and multiple crises in Latin America. Latin America Policy 11: 313–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberton, Timothy, Emily D. Carter, Victoria B. Chou, Angela R. Stegmuller, Bianca D. Jackson, Yvonne Tam, Talata Sawadogo-Lewis, and Neff Walker. 2020. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. Lancet Global Health 8: 901–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, Christina M., Shawna J. Lee, Kaitlin P. Ward, and Doris F. Fu. 2021. The perfect storm: Hidden risk of child maltreatment during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Child Maltreatment 26: 139–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggero, Paola, Viviana Magiaterra, Flavia Bustreo, and Furio Rosati. 2007. The health impact of child labor in developing countries: Evidence from cross-country data. American Journal of Public Health 97: 271–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, Danilo Hernández A., Anna Oudin, Ulf Strömberg, Jan-Eric Karlsson, Hans Welinder, Gustavo Sequeira, Luís Blanco, Mario Jiménez, Félix Sánchez, and María Albin. 2010. Respiratory symptoms among waste-picking child laborers: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 16: 120–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Indhira V. 2010. The effects of earthquakes on children and human development in rural El Salvador. In Risk, Shocks and Human Development. Edited by Ricardo Fuenters-Nieva and Papa A. Seck. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, Amitabha, Guangqi Liu, Yinzi Jin, Zheng Xie, and Zhi-Jie Zheng. 2020. Public health preparedness and responses to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in South Asia: A situation and policy analysis. Global Health Journal 4: 121–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmal, Joydeb, and Jorge Guillen. 2015. Poverty, educational failure and the child-labour trap: The Indian experience. Global Business Review 16: 270–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children/UNICEF/World Vision/Plan International. 2015. Children’s Ebola Recovery Assessment: Sierra Leone. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.org/content/dam/global/reports/emergency-humanitarian-response/ebola-rec-sierraleone.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Scanlon, Thomas J., Vivien Prior, Maria Luiza N. Lamarao, and Margaret A. Lynch. 2002. Child Labour. BMJ 325: 401–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlick, Cornelia, Manuela Joachin, Leonardo Briceño, Daniel Moraga, and Katja Radon. 2014. Occupational Injuries among Children and Adolescents in Cusco Province: A Cross-sectional Study. BMC Public Health 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sedlacek, Guilherme, Suzanne Duryea, Nadeem Ilahi, and Masaru Sasaki. 2009. Child Labor, Schooling and Poverty in Latin America. In Child Labor and Education in Latin America. Edited by Peter F. Orazem, Guilherme Sedlacek and Tzannakos Zafiris. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiq, Najeeb M. 2007. Household Schooling and Child Labor Decisions in Rural Bangladesh. Journal of Asian Economics 18: 946–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfuddin, Syed. 2020. The world after COVID-19. The Round Table 109: 247–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley-Egan, Clare, and Jim Dratwa. 2019. Marginalization, Ebola and Health for All: From outbreak to lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shendell, Derek G., Saisattha Noomnual, Shumaila Chishti, MaryAnn Sorensen Allacci, and Jaime Madrigano. 2016. Exposures resulting in safety and health concerns for child laborers in less developed countries. Journal of Environmental and Public Health 2016: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Gisella Christina, Jorge Alberto Iriart, Sônia Christina Lima Chaves, and Erik Ashley Abade. 2019. Characteristics of research on child labor in Latin America. Cadernos de Saúde Publica 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, William C. 2020. Potential long-term consequences of school closures: Lessons from the 2013–2016 Ebola pandemic. Research Square. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorsa, Solomon, and Alemu Abera. 2016. A study on child labor in three major towns of southern Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 20: 136–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sserwanja, Quraish, Joseph Kawuki, and Jean Kim. 2021. Increased child abuse in Uganda amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 57: 188–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, Rupert. 2020. COVID-19 in South Asia: Mirror and catalyst. Asian Affaires 51: 542–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamarit, Alicia, Usue de la Barrera, Estefanía Mónaco, Konstanze Schoeps, and Inmaculada Montoya Castilla. 2020. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in Spanish adolescents: Risk and protective factors of emotional symptoms. Revista de Psicologia Clinica con Niňos y Adolescentes 7: 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- Taraphdar, Pranita, Rray T. Guha, Dibakar Haldar, Aniruddha Chatterjee, Adhiraj Dasgupta, Bikram K. Saha, and Sanku Mallik. 2011. Socioeconomic consequences of HIV/AIDS in the famility system. Nigerian Medical Journal: Journal of the Nigeria Medical Association 52: 250–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Group. 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33696/148198.pdf?sequence=4andisAllowed=y (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Tiwary, Rajnarayan, Asim Saha, and John Parikh. 2009. Respiratory mobilities among working children of gem polishing industries, India. Toxicology and Industrial Health 25: 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. 2007. Child Labour, Education and Policy Options. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/Child_Labor_Education_and_Policy_Options.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

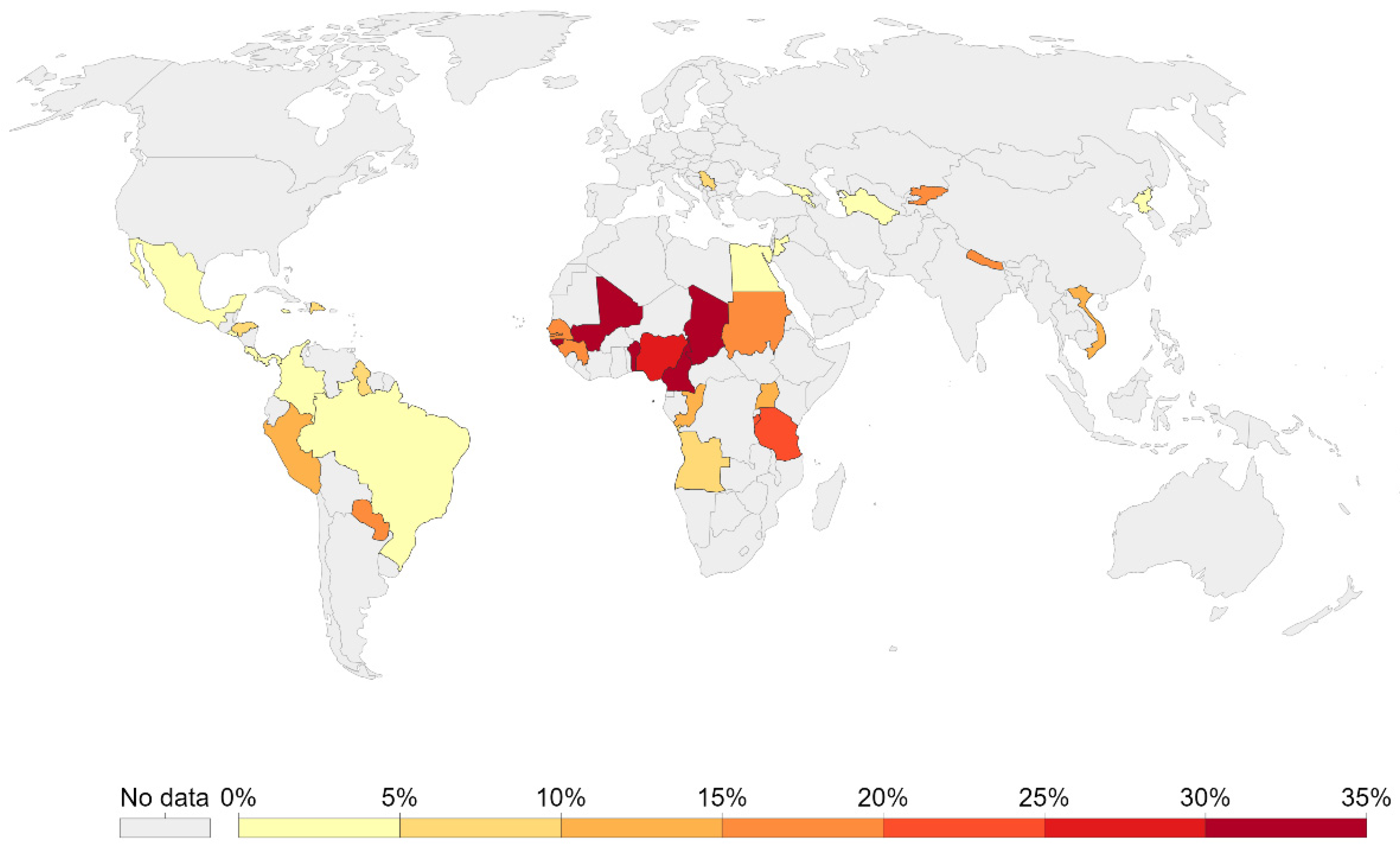

- UNICEF. 2019a. Percentage of Children Aged 5–17 Years Engaged in Child Labour (by Sex). Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-labour/ (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- UNICEF. 2019b. Guidelines to Strengthen the Social Service Workforce for Child Protection. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/Guidelines-to-strengthen-social-service-for-child-protection-2019.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- United Nations Statistics Division. 2021. Child Labor. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/child-labor (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- United Nations/DESA. 2020. Responses to the COVID-19 Catastrophe Could Turn the Tide on Inequality. Available online: https://olc.worldbank.org/system/files/PB-65.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Van Lancker, Wim, and Zachary Parolin. 2020. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. Lancet Public Health 5: 243–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, William, and Alok Bohara. 2010. Household shocks, child labor and child schooling: Evidence from Guatemala. Latin American Research Review 45: 165–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff, Adam. 2007. The economic consequences of health shocks: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Health Economics 26: 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webbink, Ellen, Jeroen Smits, and Eelke de Jong. 2012. Hidden child labor: Determinants of housework and family business work of children in 16 developing countries. World Development 40: 631–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workie, Endashaw, Joby Mackolil, Joan Nyika, and Sendhil Ramadas. 2020. Deciphering the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food security, agriculture and the livelihoods: A review of the evidence from developing countries. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Qi, and Yanfeng Xu. 2020. Parenting stress and risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: A family stress theory-informed perspective. Developmental Child Welfare 2: 180–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunsch, Kathrin, Carina Nigg, Claudia Niessner, Steffen C. E. Schmidt, Doris Oriwol, Anke Hanssen-Doose, Alexander Burchartz, Ana Eichsteller, Simon Kolb, Annette Wortrh, and et al. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on the interrelation of physical activity, screen time and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents in Germany: Results of the Motorik-Modul study. Children 8: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder-van den Brink, Hélène. 2019. Reflections on “Building Back Better” child and adolescent mental health care in a low-resource postemergency setting: The case of Sierra Leone. Frontiers in Psychiatry 10: 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahed, Ghazal, Newsha Chehrehrazi, and Abouzar Nouri Talemi. 2020. How does COVID-19 affect child labor? Archives of Pediatric Infectious Diseases 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, Daniela, Dante Contreras, and Diana Kruger. 2011. Child Labor and Schooling in Bolivia: Who’s Failing Behing? The Roles of Domestic Work, Gender and Ethnicity. World Development 39: 588–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keyword(s) | Synonym or Variations |

|---|---|

| Child labour | Child labor, minor employees, working children, child labor force, child labourer, child laborer, employment of children, labour of children |

| Pandemic | Epidemic, contagious diseases, Ebola, SARS, HIV/AIDS |

| Developing countries | Developing economies, low-and-middle income countries, emerging economies, emerging countries, developing nations, Third World |

| Author(s) | Case | Country/Countries | Methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyambedha et al. (2003) | HIV/AIDS | Kenya | A combination of qualitative and quantitative research, cross-sectional research, semi-structured interviews, questionnaire, in-depth interviews. | The HIV/AIDS epidemic in Kenya affected the care of orphans since the majority of orphans worked as servants. In addition, the pandemic led to demographic changes and affected food security in the country. |

| Roggero et al. (2007) | HIV/AIDS, malaria | 83 developing countries | Multiple regression between child labour and health indicators. | There is a positive association between child labour and the presence of infectious diseases, such as malaria and HIV/AIDS. |

| Lugalla and Sigalla (2010) | HIV/AIDS | United Republic of Tanzania | Ethnographic qualitative research, including in depth-interviews, observation etc. | Minors were forced into the labour force due to increased poverty rates and reduced household income. Poverty and HIV/AIDS were correlated, mainly for orphans. |

| Evans (2012) | HIV/AIDS | Tanzania and Uganda | Qualitative survey, semi-structured interviews, focus groups. | In both countries youths were pressured to work in order to sustain their family. The pandemic also affected the physical health and well-being of caregivers. |

| Gicharu et al. (2015) | HIV/AIDS | Kenya | Qualitative and quantitative research, interviews, questionnaire, observation. | The pandemic affected children’s lives and increased absenteeism from school, dropout rates and child labour. |

| Save the Children/UNICEF/World Vision/Plan International (2015) | Ebola virus disease (EVD) | Sierra Leone | Thematic content analysis. | The Ebola pandemic increased child labour and maltreatment, mainly due to school closures and reduced household income. |

| Ly et al. (2016) | EVD | Liberia | Cluster sampling during March–April 2015 in 941 households. | The pandemic led to higher poverty and child labour rates, leading to psychosocial problems and higher social vulnerability. |

| Ngegba and Mansaray (2016) | EVD | Sierra Leone | Questionnaires, interviews, observation and focus group discussion for the period September–November 2015. | The pandemic affected mainly the well-being of girls; most of them dropped out of school in order to engage in economic activity. |

| Sorsa and Abera (2016) | Malaria | Ethiopia | A combination of qualitative and quantitative research, including in depth interviews, focus groups discussions, observations and cross-sectional surveys. | The researchers studied child employment in three major Ethiopian towns and concluded that minor employees had a negative attitude towards education. Among them, the malaria epidemic was reported as the main health problem. The pandemic threatened their development and the family unit. |

| Abimanyi-Ochom et al. (2017) | HIV/AIDS | Uganda | Cross-sectional study carried out from October 2010 to January 2011 using questionnaires. | The pandemic increased the need for child labourers in households with a person living with the disease. The impact was greater for boys. |

| Mora-Garcia (2018) | Malaria | Costa Rica | Quantitative research, difference-in-difference method. | Malaria eradication programs increased schooling and reduced child labour. |

| Yoder-van den Brink (2019) | EVD | Sierra Leone | Dissemination and implementation research. | The Ebola pandemic affected everyday lives and well-being in the country. Child labour increased due to the school closures. |

| Smith (2020) | EVD | Sierra Leone and Guinea | Multiple survey (Demographic Health Surveys, Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys), pre and post period 2013–2016. | Dropout rates in the post-Ebola period increased and students were forced to work in order to face the economic crisis and to support their families. |

| Author(s) | Case | Sample | Methodology | Results and Suggestions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chopra (2020) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | Child protection services in the country are not fully functional. Children in the country, mainly street and abandoned children, receive limited support, which increases the risks of child abuse and labour. |

| Greenbaum et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | The recent pandemic could increase human trafficking and labour exploitation. Minors are more likely to engage in hazardous or illegal activities and work in unhealthy working conditions. |

| Larmar et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Nepal | Literature review | Recovery programs should be applied in the country in order to build capacity and strengthen cooperation among social workers, non-governmental organizations, health professionals and community-based organizations. |

| Owusu and Frimpong-Manso (2020) | COVID-19 | Ghana | Literature review | The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to have severe socioeconomic consequences, mainly for poor families. As a result, poor children are more likely to be left homeless and be forced to work. |

| Progga et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Bangladesh | Literature review | Child labour should be effectively detected and prevented. A dataset on child labour would be an effective solution in Bangladesh and in other countries of the region, including India, Nepal and Pakistan. |

| Nguyen et al. (2020) | COVID-19 | Vietnam | Literature review | It is estimated that the pandemic could lead to severe socioeconomic problems, including increased exploitation and child labour, higher dropout rates and malnutrition. |

| Ramaswamy and Seshadri (2020) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | Lockdown during the recent pandemic and the arising economic issues are expected to increase child abuse, trafficking and maltreatment, including child labour. The study concluded that attention should be paid to the likely psychosocial and mental health issues for children as a result of the pandemic. |

| ILO/UNICEF (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | The research concluded that the recent pandemic could affect child labour through reducing employment opportunities, living standards, remittances and migration and international aid flows. Additional channels that could influence child labour were increased informal child labour, reduced Foreign Direct Investment and school closures. |

| The World Bank Group (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | The COVID-19 pandemic will lead to a shock to education, resulting in higher dropout rates, which are linked to higher rates of child labour. |

| United Nations/DESA (2020) | COVID-19 | Not defined | Literature review | School closures as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with higher child labour rates and maltreatment. |

| Kaur and Byard (2021) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | The potential consequences of COVID-19 include an economic crisis, which would mainly affect children. India has severe gaps in the protection services and therefore minors are more vulnerable to child labour and exploitation. |

| Sserwanja et al. (2021) | COVID-19 | Uganda | Literature review | The pandemic had a significant negative impact on the children’s health status and food care. The country has insufficient social support systems which rendered children even more vulnerable to child abuse, including child labour and limited financial support. |

| Daly et al. (2021) | COVID-19 | Nepal | Literature review | Nepalese children are more vulnerable to poverty, poor health, including COVID-19 contamination and educational exclusion. |

| Pattanaik (2021) | COVID-19 | India | Literature review | The study concludes that the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to have a significant negative impact on the country’s economy and on the labour market imperfections, leading to higher child labour rates. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kechagia, P.; Metaxas, T. Are Working Children in Developing Countries Hidden Victims of Pandemics? Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10090321

Kechagia P, Metaxas T. Are Working Children in Developing Countries Hidden Victims of Pandemics? Social Sciences. 2021; 10(9):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10090321

Chicago/Turabian StyleKechagia, Polyxeni, and Theodore Metaxas. 2021. "Are Working Children in Developing Countries Hidden Victims of Pandemics?" Social Sciences 10, no. 9: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10090321

APA StyleKechagia, P., & Metaxas, T. (2021). Are Working Children in Developing Countries Hidden Victims of Pandemics? Social Sciences, 10(9), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10090321