Political Leaders in the APP Ecosystem

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Politainment and Spectacularization

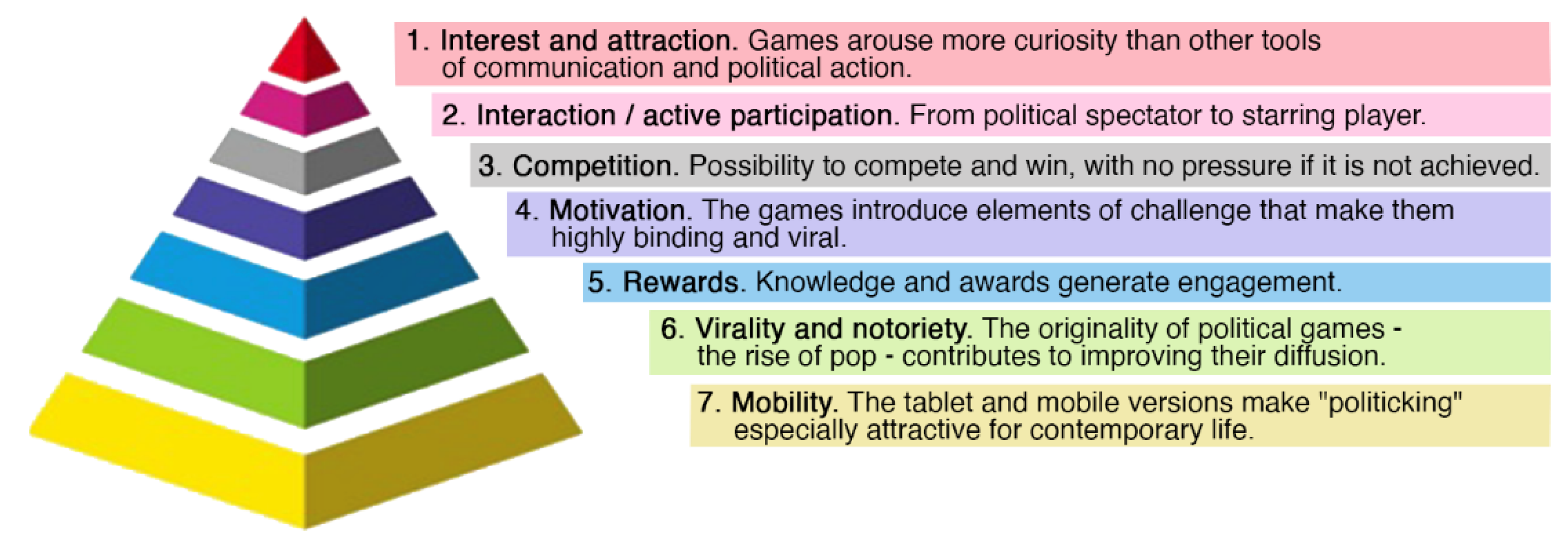

- Descriptive contributions based on app analysis and the gamification of politics (Gutiérrez-Rubí 2014; Vázquez-Sande 2016; Gómez-García et al. 2019; Gil-Torres et al. 2020).

- Work that aims to introduce concepts such as “gamocracy” or “politicking” into academia, which have so far found little acceptance (Gekker 2012, 2019; Navarro-Sierra and Quevedo-Redondo 2020; González-González and Navarro-Adelantado 2021). These concepts are inspired by the intention to promote political engagement through playful agency.

1.2. From Apps to Casual Politicking

2. Objectives

- Research Question 1. What discourse do the apps suggest in relation to the political leaders of the countries that make up the sample between 2013 and 2020?

- Research Question 2. How are these apps received and what is the likely effectiveness (or level of agreement) of their users with the main discourse?

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

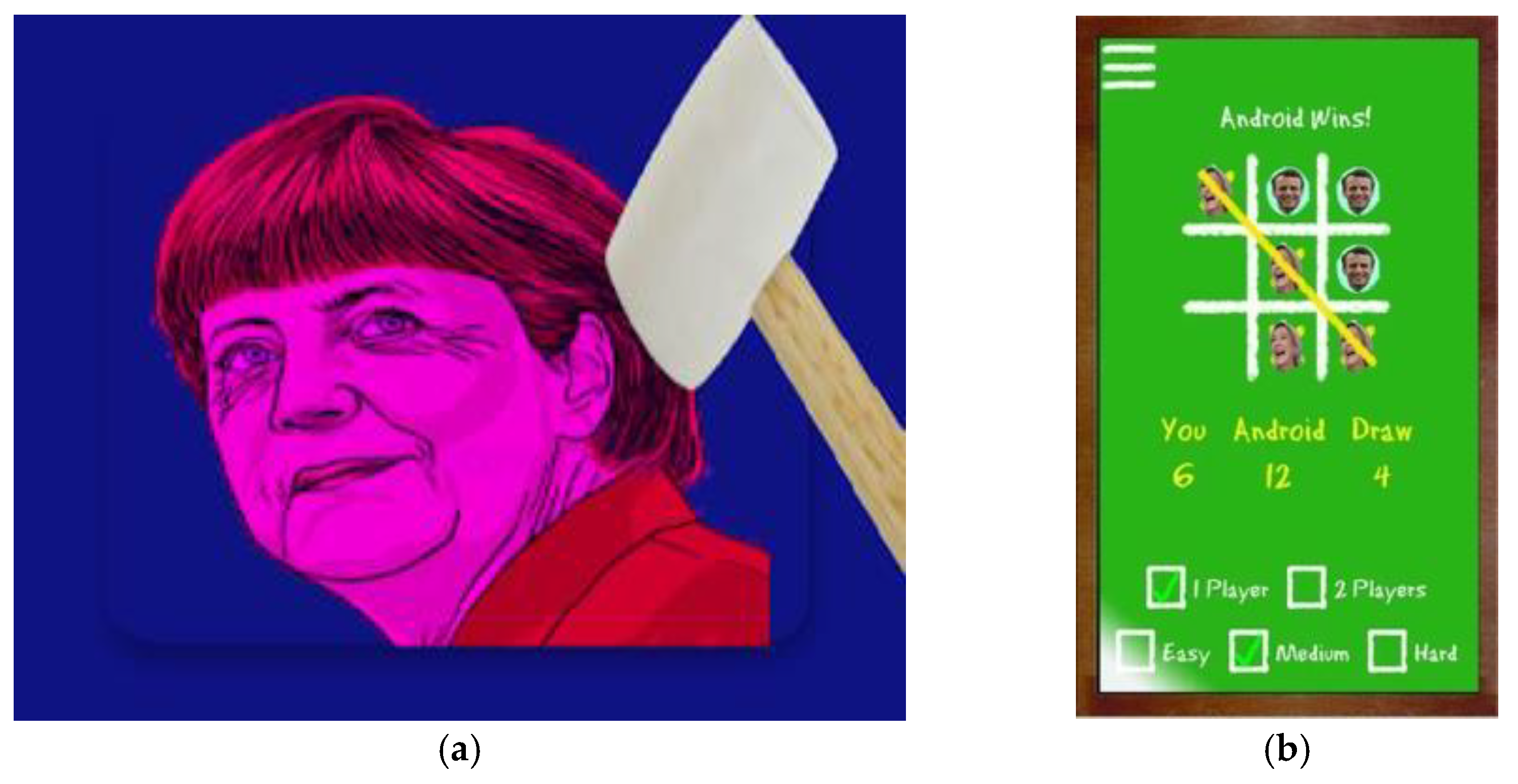

4.1. Political Popularity in Mobile Ecosystems

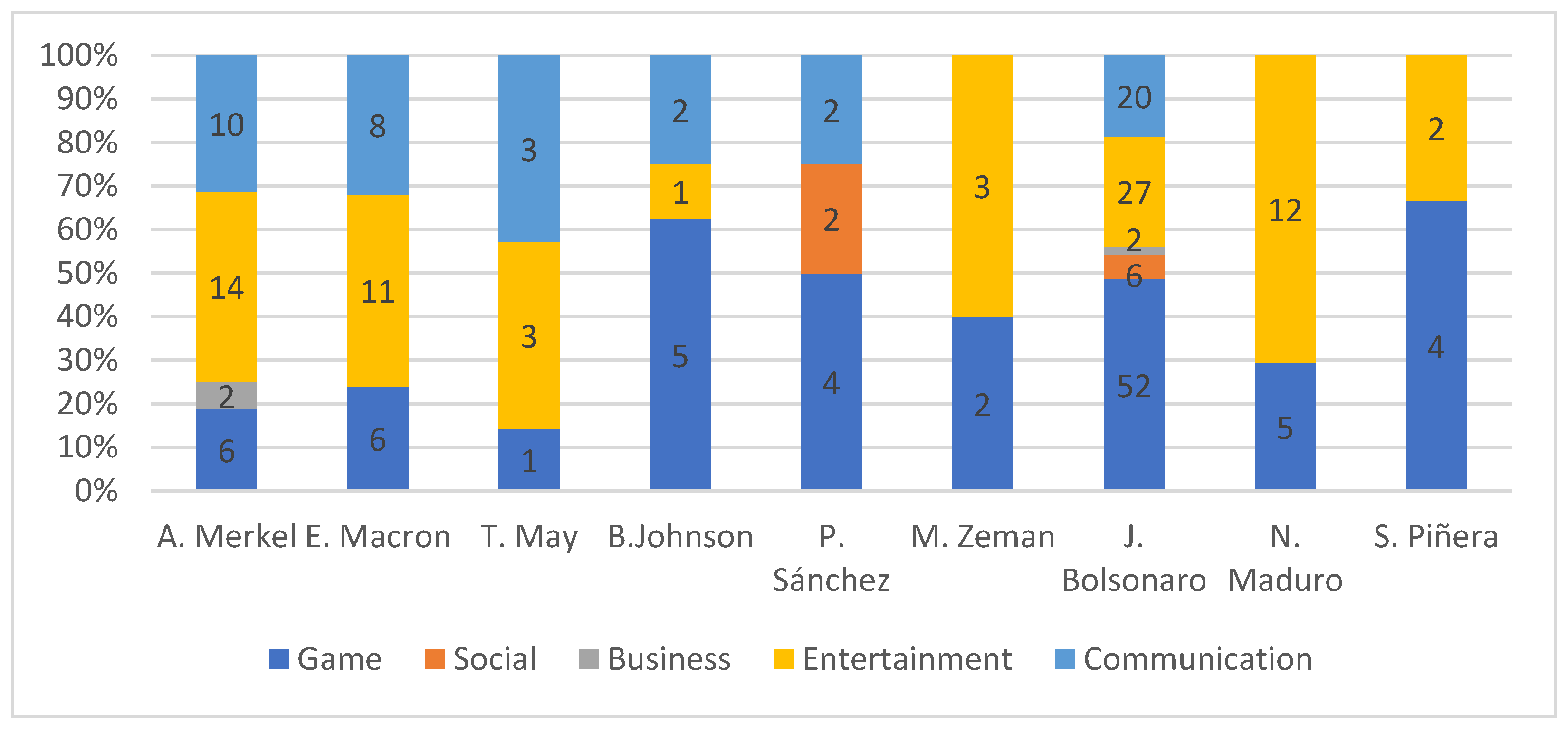

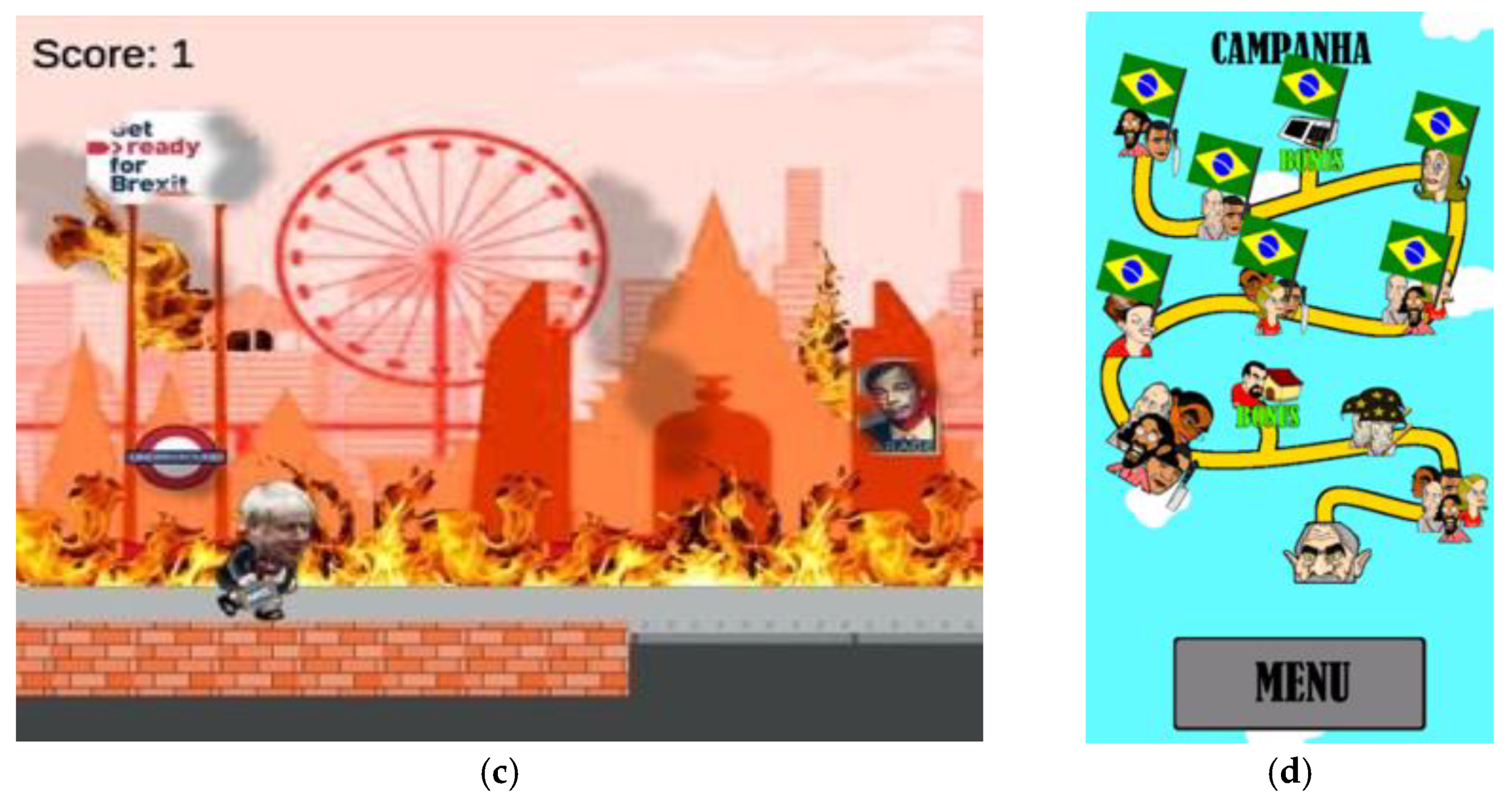

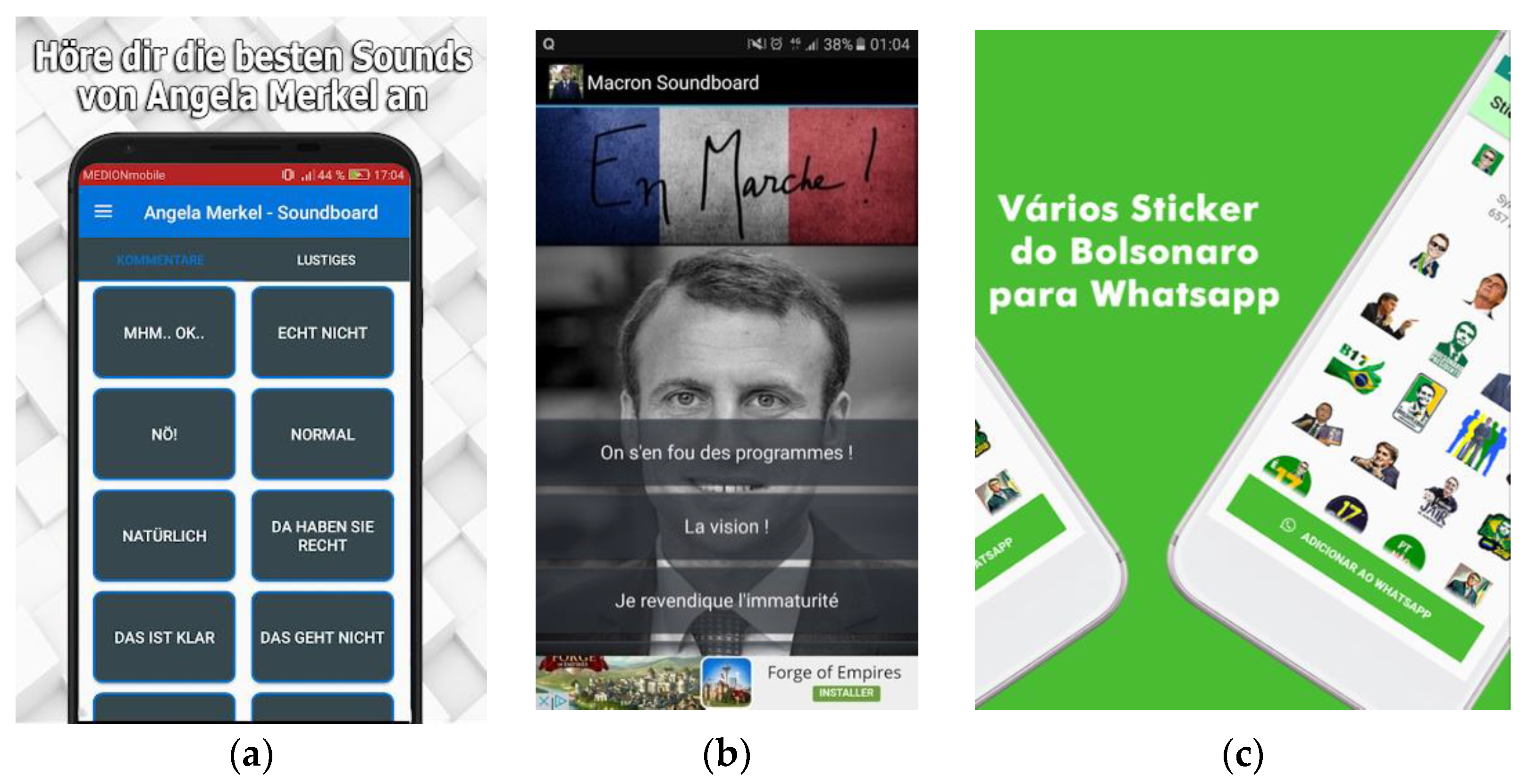

4.2. Political Personalization in the Mobile Ecosystem

4.3. Downloads Rule! (Quantity and Type of Message)

4.4. A Polarized Reception

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The rest of the leaders had a marginal presence, such as the case of Mark Rutte (Netherlands), Charles Michel (Belgium) Mauricio Macri (Argentina) and Sergio Matarella (Italy) with two apps. Another ten leaders of an executive branch only have one (V. Dancila, Romania; S. Löfven, Sweden; S. Niinistö, Finland; A. Tsipras, Greece; M.D. Higgings, Ireland; J. Muscat, Republic of Malta; A. Duda, Poland; M.R. de Sousa, Portugal; S. Kurz, Austria; B. Pahor, Slovenia). |

| 2 | The remaining leaders in the sample (those with fewer than five apps) did not have any outstanding dates. The most significant datum was the presence of the Greek president, Alexis Tsipras, and his only app Τσίπρας Jumper (Koplax Studio, 2015). This game consisted in the president collecting as many coins as possible to cope with the economic crisis. It was in the range of 100–500 downloads. |

References

- Ahonen, Tomi. 2008. Mobile as 7th of the Mass Media: Cellphone, Cameraphone, iPhone, Smartphone. Londres: FuturetexT. [Google Scholar]

- Aparici, Roberto, and Diego García-Marín. 2018. Prosumers and emirecs: Analysis of two confronted theories. Comunicar 55: 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballesteros-Herencia, Carlos A. 2020. Los marcos del compromiso: Framing y Engagement digital en la campaña electoral de España de 2015. Observatorio (OBS*) 14: 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Herencia, Carlos, and Salvador Gómez-García. 2020. Batalla de frames en la campaña electoral de abril de 2019. Engagement y promoción de mensajes de los partidos políticos en Facebook. Profesional De La Información 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmas, Meital, and Tamir Sheafer. 2013. Leaders first, countries after: Mediated political personalization in the international arena. Journal of Communication 63: 454–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Toni. 1986. The Politics of the Popular and Popular Culture. In Popular Culture and Social Relations. Edited by Tony Bennett, Colin Mercer and Janet Woollacott. Philadelphia: Open University Press, pp. 6–21. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal, Salomé. 2003. Personalización de la Política. In Comunicación Política en Televisión y Nuevos Medios. Edited by Salomé Berrocal. Barcelona: Ariel, pp. 55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Berrocal, Salomé. 2017. Politainment, la política espectáculo y su triunfo en los medios de comunicación. In Politainment. La Política Espectáculo en los Medios de Comunicación. Edited by Salomé Berrocal. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Scott W., and Nojin Kwak. 2011. Political involvement in ‘Mobilized’ society: The interactive relationships among mobile communication, network characteristics, and political participation. Journal of Communication 61: 1005–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, Laura, and Carles Marín-Lladó. 2021. What are political parties doing on TikTok? The Spanish case. Profesional De La Información 30: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, Steven H., Marilyn Jackson-Beeck, Jean Duvall, and Donna Wilson. 1977. Mass Communication in Political Socialization. In Handbook of Political Socialization. Edited by Stanley Allen Renshon. New York: Free Press, pp. 223–58. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Stephen. 2003. A tale of two houses: The House of Commons, the Big Brother House and the people at home. Parliamentary Affairs 56: 733–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Jonathan. 2017. Politicising fandom. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 19: 408–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Yingtong, Weijian Li, Zhirong Liu, Zhenhua Dong, Jiebo Luo, and Philip S. Yu. 2019. Uncovering Download Fraud Activities in Mobile App Markets. Paper presented at 2019 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), Vancouver, BC, Canada, August 27–30; pp. 671–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durántez-Stolle, Patricia, and Raquel Martínez-Sanz. 2019. El politainment en la construcción transmediática de la imagen del personaje político. Communication & Society 32: 111–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EuroNews. 2018. Theresa May Viaja a África para Encontrar Nuevas Oportunidades para el Comercio Británico. Euronews. Available online: https://es.euronews.com/2018/08/28/theresa-may-viaja-a-africa-para-encontrar-nuevas-oportunidades-para-el-comercio-britanico (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Gekker, Alex. 2012. Gamocracy: Political Communication in the Age of Play. Master’s thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Gekker, Alex. 2019. Playing with Power: Casual politicking as a new frame for political analysis. In The Playful Citizen: Civic Engagement in a Mediatized Culture. Edited by René Glas, Sybille Lammes, Michiel de Lange, Joost Raessens and Imar de Vries. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 387–419. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Torres, Alicia, Juan Martín-Quevedo, Salvador Gómez-García, and Cristina San José-De la Rosa. 2020. The Coronavirus in the mobile device ecosystem: Developers, discourses and reception. Revista Latina Comunicación Social 78: 329–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glas, René, Sybille Lammes, Michiel de Lange, Joost Raessens, and Imar de Vries. 2019. The playful citizen: An introduction. In The Playful Citizen: Civic Engagement in a Mediatized Culture. Edited by René Glas, Sybille Lammes, Michiel de Lange, Joost Raessens and Imar de Vries. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-García, Salvador, Alicia Gil-Torres, José Agustín Carrillo-Vera, and Nuria Navarro-Sierra. 2019. Constructing Donald Trump: Mobile apps in the political discourse about the President of the United States. Comunicar 59: 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, Salvador, María Antonia Paz-Rebollo, and José Cabeza-San-Deogracias. 2021. Newsgames against hate speech in the refugee crisis. Comunicar 67: 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Tinoco, Alicia. 2010. El Mobile Marketing como estrategia de comunicación. Icono 8: 238–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González-González, Carina, and Vicente Navarro-Adelantado. 2021. The limits of gamification. Convergence 27: 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindstaff, Laura. 2008. Culture and Popular Culture: A Case for Sociology. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 619: 206–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Rubí, Antoni. 2014. Tecnopolítica. El uso y la Concepción de las Nuevas Herramientas Tecnológicas Para la Comunicación, la Organización y la Acción Política Colectivas. Barcelona. Available online: www.gutierrez-rubi.es (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Gutiérrez-Rubí, Antoni. 2015. La generación Millennials y la Nueva política. Revista de Estudios de Juventud 108: 161–69. Available online: https://bit.ly/3h2Dh5d (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Haigh, Michel M., and Aaron Heresco. 2010. Late-night Iraq: Monologue joke content and tone from 2003 to 2007. Mass Communication & Society 13: 157–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highfield, Tim, Stephen Harrington, and Axel Bruns. 2013. Twitter as a technology for audiencing and fandom: The #Eurovision phenomenon. Information, Communication & Society 16: 315–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Juul, Jesper. 2010. A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and Their Players. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenski, Kate, Bruce W. Hardy, and Kathleen Hall Jamieson. 2010. The Obama Victory. How Media, Money, and Message Shaped the 2008 Election. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yonghwan, Hsuan-Ting Chen, and Yuan Wang. 2016. Living in the smartphone age: Examining the conditional indirect effects of mobile phone use on political participation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 60: 694–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleina, Nilton Cesar Monastier. 2020. De herói de jogos a adesivo no WhatsApp: Da imagem de Jair Bolsonaro retratada em aplicativos para celular. Revista Mediação 22: 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger, Ulrike, and Jakob Svensson. 2015. The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach. New Media & Society 17: 1241–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Light, Ben, Jean Burgess, and Stefanie Duguay. 2016. The walkthrough method: An approach to the study of apps. New Media & Society 20: 881–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López Vidales, Nereida, and Leire Gómez Rubio. 2021. Tendencias de cambio en el comportamiento juvenil antes los media: Millenials vs. Generación Z. Estudios Sobre el Mensaje Periodístico 27: 543–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-DeAnda, Magdalena, and Miguel Cedeño-Navarro. 2014. El videojuego político en México como género editorializado para la exhibición, burla y toma de postura del quehacer de los políticos. Caleidoscopio 30: 73–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Meri, Amparo, Silvia Marcos-García, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2020. Estrategias comunicativas en Facebook: Personalización y construcción de comunidad en las elecciones de 2016 en España. Doxa Comunicación 30: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luskin, Robert C. 1990. Explaining political sophistication. Political Behavior 12: 331–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, Fréderic. 2011. Cultura Mainstream. Cómo Nacen los Fenómenos de Masas. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Quevedo, Juan, Erika Fernández-Gómez, and Francisco Segado-Boj. 2019. How to Engage with Younger Users on Instagram: A Comparative Analysis of HBO and Netflix in the Spanish and US Markets. International Journal on Media Management 21: 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, Pere, Jaume Suau, and Carlos Ruiz-Caballero. 2020. Percepciones sobre medios de comunicación y desinformación: Ideología y polarización en el sistema mediático español. Profesional De La Información 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, Gianpietro, and Anna Sfardini. 2009. Politica pop. Da “Porta a Porta” a “L’isola dei famosi”. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, Carlos, Martín Echeverría, Alejandra Rodríguez-Estrada, and Oniel Francisco Díaz-Jiménez. 2018. Los hábitos comunicativos y su influencia en la sofisticación política ciudadana. Convergencia 25: 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Navarro-Sierra, Nuria, and Raquel Quevedo-Redondo. 2020. El liderazgo político de la Unión Europea a través del ecosistema de aplicaciones móviles. Revista Prisma Social 30: 1–21. Available online: https://bit.ly/3qyIVz4 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Nye, Joseph S. 1990. Soft Power. Foreign Policy 80: 153–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, Joel. 2017. The Citizen Marketer: Promoting Political Opinion in the Social Media Age. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prada Espinel, Oscar, and Luis Miguel Romero Rodríguez. 2018. Polarización y demonización en la campaña presidencial de Colombia de 2018: Análisis del comportamiento comunicacional en Twitter de Gustavo Petro e Iván Duque. Revista Humanidades 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, Markus. 2006. Post-Broadcast Democracy: How Media Choice Increases Inequality in Political Involvement and Polarizes Elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quevedo-Redondo, Raquel, and Marta Portalés-Oliva. 2017. Imagen y comunicación política en Instagram. Celebrificación de los candidatos a la presidencia del Gobierno. El Profesional de la Información 26: 916–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raessens, Joost. 2014. The ludification of culture. In Rethinking Gamification. Edited by Mathias Fuchs, Sonia Fizek, Paolo Ruffino and Niklas Schrape. Lüneburg: Meson Press, pp. 91–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rebolledo, Marta. 2017. La personalización de la política: Una propuesta de definición para su estudio sistemático. Revista de Comunicación 16: 147–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riffe, Daniel, Stephen Lacy, Brendan R. Watson, and Frederick Fico. 2014. Analyzing Media Messages. Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Hernando, and Eulalia Puig-i-Abril. 2009. Mobilizers Mobilized: Information, Expression, Mobilization and Participation in the Digital Age. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14: 902–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romero-Rodríguez, Luis Miguel, Santiago Tejedor, and María Victoria Pabón Montealegre. 2021. Actitudes populistas y percepciones de la opinión pública y los medios de comunicación: Estudio correlacional comparado entre España y Colombia. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social 79: 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Almazán, Rodrigo, Luis Luna-Reyes, Yaneileth Rojas-Romero, José Ramón Gil-Garcia, and Dolores Luna. 2012. Open Government 2.0: Citizen Empowerment through Open Data, Web and Mobile Apps. Paper presented at International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Albany, NY, USA, October 22–25; pp. 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, Chelsea. 2016. Civic engagement in a digital age. Canadian Parliamentary Review 39: 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Segado-Boj, Francisco, Jesús Díaz-Campo, and María Soria. 2015. La viralidad de las noticias en Facebook: Factores determinantes. Telos 100: 153–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shankland, Stephen. 2008. Obama Releases iPhone Recruiting, Campaign Tool. [Blog Post]. Available online: https://cnet.co/2NL9IY6 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Street, John. 1997. Politics and Popular Culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Street, John. 2004. Celebrity politicians. Popular culture and political representation. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations 6: 435–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tau, Byron. 2012. Obama Campaign Launches Mobile App. [Blog Post]. Available online: https://politi.co/2p6bTaD (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Vázquez-Sande, Pablo. 2016. Políticapp: Hacia una categorización de las apps móviles de comunicación política. Fonseca Journal of Communication 12: 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wan, Xuqi, and Yucheng Shao. 2019. Innovative Research on the Interactive Communication of Political News in the Convergence Media Era by Taking the Newsgames Products of Mainstream Media for Example. The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology 7: 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Hai, Zhe Liu, Yao Guo, Chen Xiangqun, Zhang Miao, Xu Guoai, and Hong Jason. 2017. An Explorative Study of the Mobile App Ecosystem from App Developers’ Perspective. International World Wide Web Conference Committee, 163–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, Mark. 2013. Celebrity Politics: Image and Identity in Contemporary Political Communication. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Raymond. 1993. Culture is Ordinary. In Studying Culture: An Introductory Reader. Edited by Ann Gray and Jim McGuigan. London: Arnold, pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Jason. 2011. Playing with politics: Political fans and Twitter faking in post-broadcast democracy. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 17: 445–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Masahiro, Matthew J. Kushin, and Francis Dalisay. 2018. How Informed Are Messaging App Users about Politics? A Linkage of Messaging App Use and Political Knowledge and Participation. Telematics & Informatics 35: 2376–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Sally. 2010. How Australia Decides: Election Reporting and the Media. Port Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zamora-Medina, Rocío, José Carlos Losada-Díaz, and Pablo Vázquez-Sande. 2020. A taxonomy design for mobile applications in the Spanish political communication context. El Profesional de la Información 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora Medina, Rocío, Salvador Gómez García, and Helena Martínez Martínez. 2021. Los memes políticos como recurso persuasivo online. Análisis de su repercusión durante los debates electorales de 2019 en España. Opinião Publica 27: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

| Casual Gaming | Casual Politicking |

|---|---|

| Key priority for developers/Juiciness: visual and auditory gratification is prioritized based on the simplification of tasks and a clear definition of the objectives of the game. | Key priority for developers/Intuitive interfaces: design patterns help increase the usability of the product with solutions known to users who find the app reliable and attractive for immediate interaction. |

| Prevalence of simplicity/Low interruptibility: simple gameplay is offered in short bursts to avoid saving games. | No prevalence of simplicity/Issue-centered: action focused on the theme of the game instead of ideology, thus achieving an engagement supported by entertainment on the political aspect. |

| Without penalty/Indulgence: apps designed for gamers to avoid going too far back in the gaming experience if they make mistakes. | Penalty/Low penalty: fast recovery in case of failure in the game to increase the number of possible players. |

| Social impetus: tendency to foster social connections within the game, either by making the game multiplayer, creating leader boards or offering bonuses/points for inviting friends. | Social impetus: the bonds that are created are an important part of the participatory experience, which underlines fun over ideology. |

| Identification Data | |

| App’s name | [Name] |

| Platform/OS | Android/iOS/both |

| Launch date | [Day/Month/Year] |

| Developer’s country | [Name] |

| Downloads (estimated) | [Number] |

| Most popular country | [Name] |

| Price | Free/Ads/In-app purchases/xx € |

| Genre | Game/Social/Business/Entertainment/Communication |

| Discourse type | Escapist/Circumstantial/Informative/Intentional/Satirical |

| Description | App description from store page |

| Main character | [If any: Name] |

| Adversaries | [If any: Name] |

| Ideological positioning | Positive/Neutral/Negative |

| Development Characteristics | |

| Developer | [Name] |

| Total apps launched | [Number] |

| Profile | Professional/Commercial/Casual/Ideological |

| User’s Feedback | |

| Number of votes | [Number] |

| Rating | [Votes in each position, scale 1 to 5] |

| Number reviews | [Number] |

| Reviews | [Text from store page] |

| Others | [Free text] |

| Country | Leader | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | J. Bolsonaro | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 27 | 66 | 5 | 0 | 107 |

| Germany | A. Merkel | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 32 |

| France | E. Macron | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 25 |

| Venezuela | N. Maduro | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 17 |

| The United Kingdom | T. May | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| B. Johnson | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 8 | ||

| Spain | P. Sánchez | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| Chile | S. Piñera | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Czech R. | M. Zeman | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Most Popular App(s) | Download Range | Type of App | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stickers do Bolsonaro | 500,000–1,000,000 | Stickers | Jair Bolsonaro |

| A. Merkel Soundboard | 100,000–500,000 | Soundboard | Angela Merkel |

| Bolsonaro Voador | 100,000–500,000 | Game | |

| Bolsonaro-Áudios | 100,000–500,000 | Soundboard | |

| Bolsonaro vs. Petralhada | 100,000–500,000 | Game | |

| Bolsonaro Terror do PT | 100,000–500,000 | Game | |

| Brazilian Trump | 100,000–500,000 | Meme stickers | |

| Bolsonaro no WhatsApp | 100,000–500,000 | Stickers | |

| Maduro Mango Attack | 100,000–500,000 | Game | Nicolás Maduro |

| Miloš Zeman—HRA | 50,000–100,000 | Game | Miloš Zeman |

| Miloš Zeman—Quotes | 50,000–100,000 | Soundboard | Miloš Zeman |

| Piñera Stickers WhatsApp | 10,000–50,000 | Stickers | Sebastián Piñera |

| Macron Soundboard | 5000–10,000 | Soundboard | Emmanuel Macron |

| Pedro Sánchez Simulator | 5000–10,000 | Game | Pedro Sánchez |

| Boris Johnson Speaks! | 1000–5000 | Soundboard | Boris Johnson |

| Theresa May News | 50–100 | Informative | Theresa May |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quevedo-Redondo, R.; Navarro-Sierra, N.; Berrocal-Gonzalo, S.; Gómez-García, S. Political Leaders in the APP Ecosystem. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080307

Quevedo-Redondo R, Navarro-Sierra N, Berrocal-Gonzalo S, Gómez-García S. Political Leaders in the APP Ecosystem. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(8):307. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080307

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuevedo-Redondo, Raquel, Nuria Navarro-Sierra, Salome Berrocal-Gonzalo, and Salvador Gómez-García. 2021. "Political Leaders in the APP Ecosystem" Social Sciences 10, no. 8: 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080307

APA StyleQuevedo-Redondo, R., Navarro-Sierra, N., Berrocal-Gonzalo, S., & Gómez-García, S. (2021). Political Leaders in the APP Ecosystem. Social Sciences, 10(8), 307. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10080307