The Influence of the Negative Campaign on Facebook: The Role of Political Actors and Citizens in the Use of Criticism and Political Attack in the 2016 Spanish General Elections

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Negativity in the Electoral Campaign: From Television to Social Media

2.2. The Impact of Criticism on Facebook Users

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measures and Procedure

4. Results

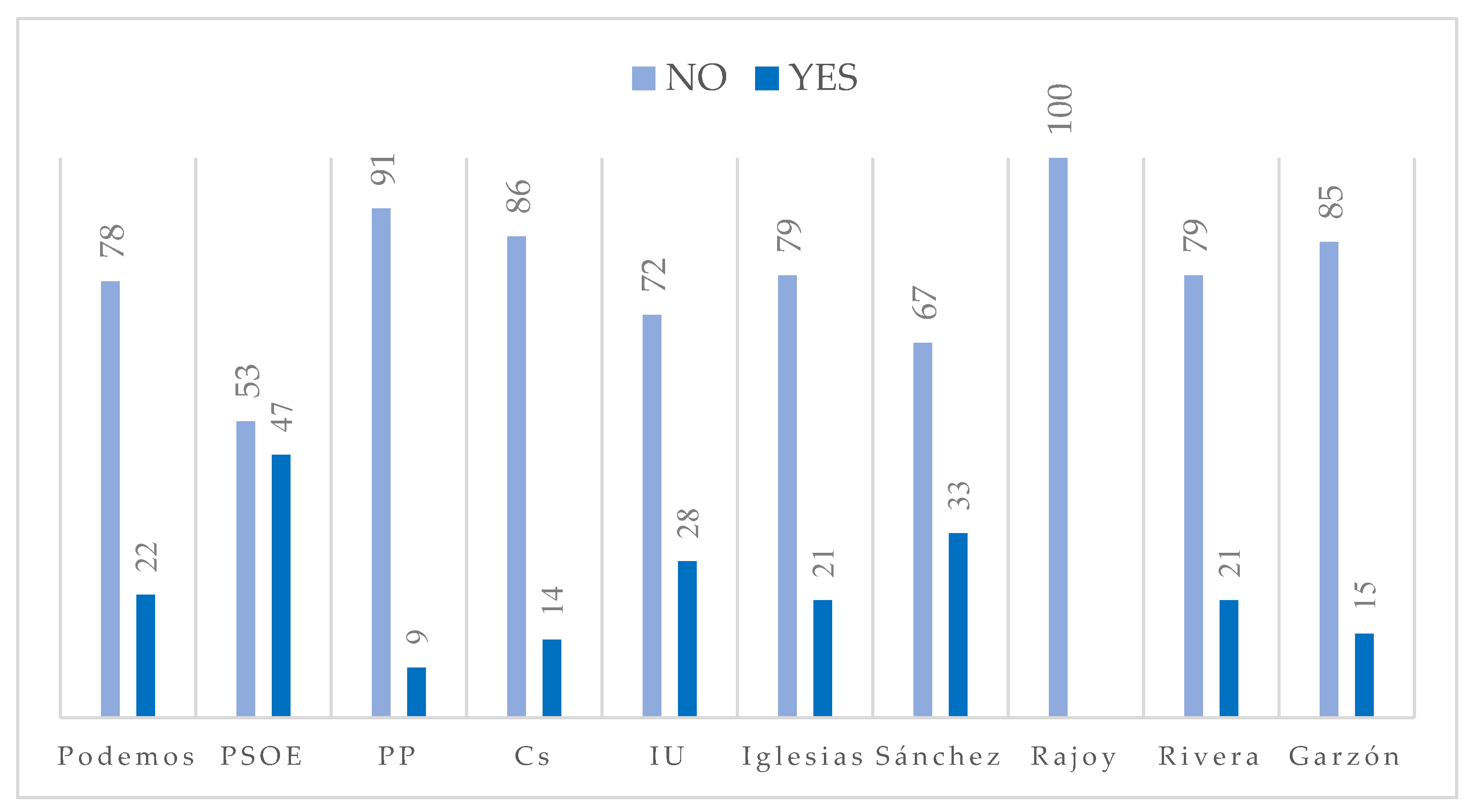

4.1. Level of Use and Recipients of Criticism by Political Actors on Facebook

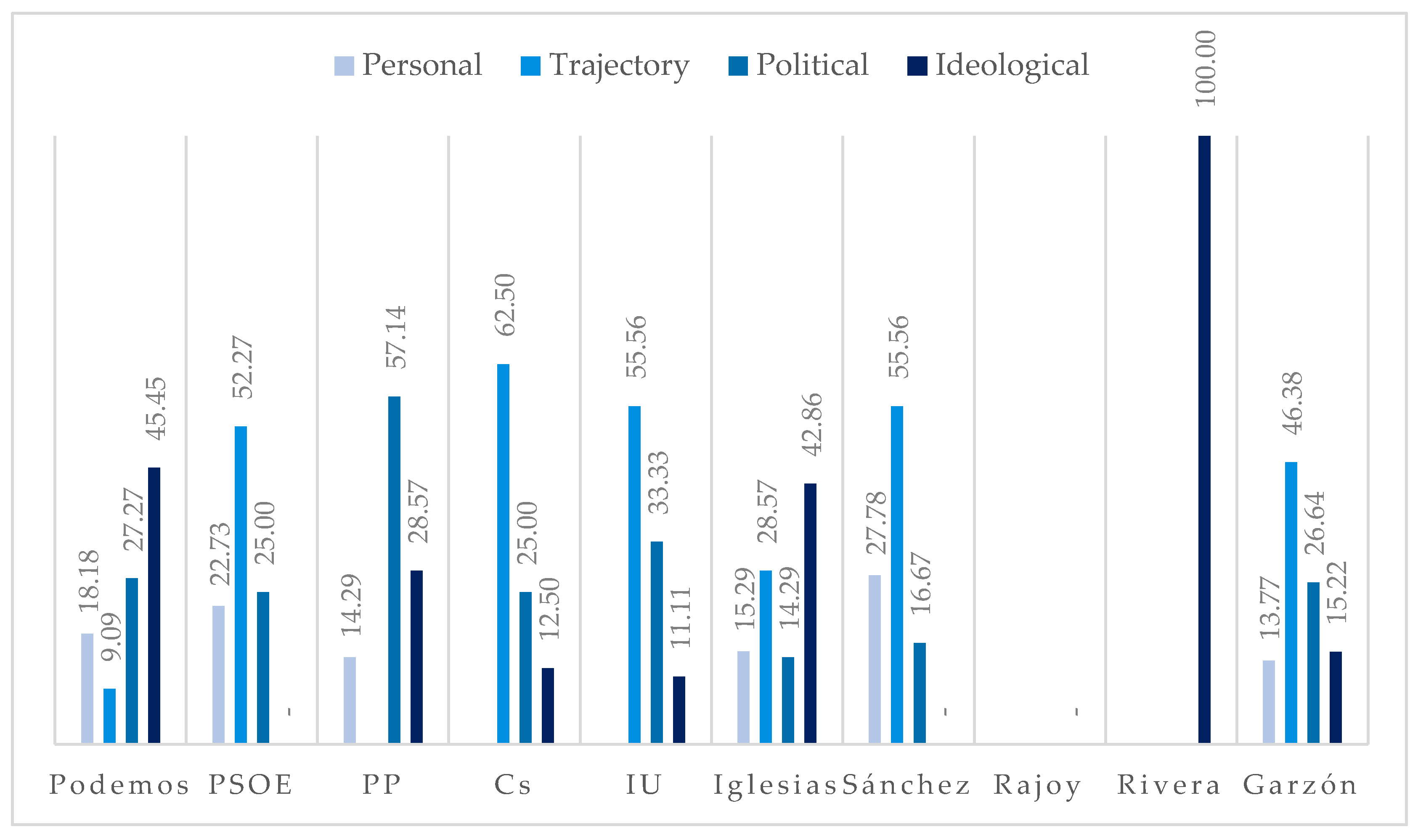

4.2. Typology of Criticism Issued by Political Actors on Facebook

4.3. The Reaction of Users on Facebook to the Criticism Issued by Political Actors

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abejón-Mendoza, Paloma, and Javier Mayoral-Sánchez. 2017. Persuasión a través de Facebook de los candidatos en las elecciones generales de 2016 en España. Profesional de la Información 26: 928–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Muñoz, Laura, Susana Miquel-Segarra, and Nadia Viounnikoff-Benet. 2021. The construction of the political agenda on Twitter and Facebook during the 2016 Spanish elections: Issues, frame and users’ interest. The Journal of International Communication 27: 215–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Muñoz, Laura, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2018. Communication of European populist leaders on Twitter: Agenda setting and the ‘more is less’ effect”. El Profesional de la Información 27: 1193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Muñoz, Laura, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2017. Transparency and political monitoring in the digital environment. Towards a typology of citizen-driven platforms. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 72: 1351–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros-Herencia, Carlos A., and Salvador Gómez-García. 2020. Batalla de encuadres durante la campaña electoral de abril de 2019: Participación y promoción de los mensajes de los partidos políticos en Facebook. Profesional de la Información 29: e290629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberà, Òscar, Astrid Barrio, and Juan Rodríguez-Teruel. 2019. New parties’ linkages with external groups and civil society in Spain: A preliminary assessment. Mediterranean Politics 24: 646–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkler, Yochai. 2007. The Wealth of Networks. How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, W. Lance. 2012. The personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 644: 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berganza-Conde, María Rosa. 2008. Medios de comunicación, “espiral del cinismo” y desconfianza política. Estudio de caso de la cobertura mediática de los comicios electorales europeos. ZER-Revista de Estudios de Comunicación 13: 121–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cabo Isasi, Álex, and Anna García Juanatey. 2016. El discurso del odio en las redes sociales: Un estado de la cuestión. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. Available online: http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/bcnvsodi/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Informe_discurso-del-odio_ES.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Cammaerts, Bart, Alice Mattoni, and Patrick Mccurdy. 2013. Mediation and Protest Movements. Chicago: Intellect Books. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 2012. Networks of Outrage and Hope. Social Movements in the Internet Age. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 2009. Comunicación y poder. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Ceron, Andrea, and Giovanna d’Adda. 2016. E-campaigning on Twitter: The effectiveness of distribute promises and negative campaign in the 2013 Italian election. New Media & Society 18: 1935–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-Montero, Alfonso, Walter Federico Gadea-Aiello, and José Ignacio Aguaded-Gómez. 2017. La comunicación política en las redes sociales durante la campaña electoral de 2015 en España: Uso, efectividad y alcance. Perspectivas de la Comunicación 10: 55–83. [Google Scholar]

- Coromina, Òscar, Emili Prado, and Adrián Padilla. 2018. The grammatization of emotions on Facebook in the elections to the Parliament of Catalonia 2017. Profesional de la Informacion 27: 1004–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, Orlando, and Virginia García Beaudox. 2016. Comunicación Política: Narración de historias, construcción de relatos políticos y persuasión. Comunicación y Hombre 12: 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dahlberg, Lincoln. 2007. The Internet, deliberative democracy, and power: Radicalizing the public sphere. International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 3: 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dang-Xuan, Lihn, Stefan Stieglitz, Jennifer Wladarsch, and Christoph Neuberger. 2013. An investigation of influentials and the role of sentiment in political communication on Twitter during election periods. Information, Communication & Society 16: 795–825. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Report. 2021. Digital Report 2021: El informe sobre las tendencias digitales, redes sociales y mobile. We are Social and Hootsuite. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/digital-2021 (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Elmer, Greg. 2013. Live research: Twittering an election debate. New Media and Society 15: 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enli, Gunn. 2017. Twitter as arena for the authentic outsider: Exploring the social media campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US presidential election. European Journal of Communication 32: 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoll, Vicente, and Lorena Cano-Orón. 2017. Citizen Engagement on Spanish Political Parties Facebook Pages: Analysis of the 2015 Electoral Campaign Comments. Communication & Society 30: 131–48. [Google Scholar]

- García Beaudoux, Virginia. 2014. El papel de las emociones en la comunicación política actual. Storytelling y estrategia de campaña negativa. Andamios 11: 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- García Beaudoux, Virginia, and Orlando D’Adamo. 2013. Propuesta de una matriz de codificación para el análisis de las campañas negativas. Revista Opera 13: 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Geer, John G. 2006. In Defense of Negativity. Attack Ads in Presidential Campaigns. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, Jennifer, and Mark LaPointe. 2004. Cyber-Campaigning Grows Up. A Comparative Content Analysis of Websites for US Senate and Gubernatorial Races, 1998–2000. In Electronic Democracy: Mobilisation, Organisation and Participation via new ICTs. Edited by Rachel Gibson, Andrea Römmele and Steven Ward. London: Routledge, pp. 132–48. [Google Scholar]

- Haro-de-Rosario, Arturo, Alejandro Sáez-Martin, and María del Carmen Caba-Pérez. 2016. Using Social to Enhance Citizen Engagement with Local Government: Twitter or Facebook? New Media & Society 20: 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jungherr, Andreas. 2016. Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 13: 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, Robert. 2004. The Politics of Internet Communication. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Richard R., and Gerald M. Pomper. 2004. Negative Campaigning: An Analysis of US Senate Elections. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- López-Meri, Amparo, Silvia Marcos-García, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2017. What do politicians do on Twitter? Functions and communication strategies in the Spanish electoral campaign of 2016. Profesional de la Información 26: 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Meri, Amparo, Silvia Marcos-García, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2020. Communicative strategies on Facebook: Personalisation and community building in the 2016 elections in Spain. Doxa Comunicación 30: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maarek, Philippe J. 2009. Marketing Político y Comunicación. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Jürge, and Alessandro Nai. 2021. Mapping the drivers of negative campaigning: Insights from a candidate survey. International Political Science Review, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Robert. 2011. Daisy Petals and Mushroom Clouds. LBJ, Barry Goldwater, and the Ad That Changed American Politics. Louisiana: LSU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos-García, Silvia, Laura Alonso-Muñoz, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2017. Usos ciudadanos de Twitter en eventos políticos relevantes. La #SesiónDeInvestidura de Pedro Sánchez. Comunicación y Hombre 13: 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos-García, Silvia, Nadia Viounnikoff-Benet, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2020. What is There in a ‘Like’?: Political Content in Facebook and Instagram in The 2019 Valencian Regional Election. Debats 5: 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, David. 2015. The continued relevance of reception analysis in the age of social media. Tripodos 36: 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, Gianpietro. 2010. La Comunicación Política. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Nai, Alessandro, and Pascal Sciarini. 2018. Why “Going Negative?” Strategic and situational determinants of personal attacks in Swiss direct democratic votes. Journal of Political Marketing 17: 382–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orriols, Lluís, and Guillermo Cordero. 2016. The breakdown of the Spanish two-party system: The upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 general election. South European Society and Politics 21: 469–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Thomas E. 1993. Out of Order. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Shirky, Clay. 2011. The political power of social media: Technology, the public sphere, and political change. Foreign Affairs 90: 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stromer-Galley, Jennifer. 2014. Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, Eva. 2010. Global patterns of Virtual Mudslinging? The Use of Attacks on German Party Websites in State, National and European Parliamentary Elections. German Politics 19: 200–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Daniel. 2012. Tone versus information: Explaining the impact of negative political advertising. Journal of Political Marketing 11: 322–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twiplomacy. 2020. Twiplomacy Study 2020. Twiplomacy. Available online: https://twiplomacy.com/blog/twiplomacy-study-2020/ (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Valera-Ordaz, Lidia, and Guillermo López-García. 2014. Agenda y marcos en las webs de PP y PSOE en la cibercampaña de 2011. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 69: 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Valli, Chiara, and Alessandro Nai. 2020. Attack politics from Albania to Zimbabwe: A large-scale comparative study on the drivers of negative campaigning. International Political Science Review, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, Maurice, Liesbeth Hermans, and Steven Sams. 2013. Online social networks and microblogging in political campaigning: The exploration of a new campaign tool and a new campaign style. Party Politics 19: 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Stine, and Svein Magnussen. 2007. Long term memory for 400 pictures on a common theme. Experimental Psychology 54: 298–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Political Actor | Number of Messages on | |

|---|---|---|

| Parties | Partido Popular (PP) | 76 |

| Partido Socialista (PSOE) | 93 | |

| Podemos | 50 | |

| Ciudadanos (Cs) | 59 | |

| Izquierda Unida (IU) | 95 | |

| Candidates | Mariano Rajoy | 38 |

| Pedro Sánchez | 55 | |

| Pablo Iglesias | 33 | |

| Albert Rivera | 14 | |

| Alberto Garzón | 88 | |

| Total | 601 |

| Use of Criticism | |

| Yes | The publication contains a critique or attack. |

| No | The publication does not contain a critique or attack. |

| Recipient: to Whom the Criticism is Directed | |

| Political Party | Criticism is directed at a certain political party. |

| Male or FemalePolitician | Criticism is directed at a certain politician. |

| Media or journalist | Criticism is directed at a specific media, program, or journalist. |

| Institution or publicorganization | Criticism is directed at a specific institution or public organization. |

| Entrepreneur orcompany | Criticism is directed at a specific businessman or company. |

| Others | Criticism is directed at another actor, not mentioned in the previous categories. |

| Typology of the Attack | |

| Personal | Criticism or attack is directed at the personal traits or qualities of a certain actor. |

| Trajectory | Criticism or attack is directed at the functions or positions previously held by a certain actor. |

| Political | Criticism or attack is directed at the proposals or positions of a certain actor regarding a topic or question. |

| Ideological | Criticism or attack focuses on the ideology and values of a certain actor. |

| Intensity of the Attack | |

| Direct | Messages in which a certain actor is directly criticized. |

| Collateral | Messages where a certain actor is criticized while the attack remains in the background. Therefore, the main function of the message is not to criticize. |

| Structure of the Attack | |

| Simple | Messages in which only a certain actor is criticized. |

| Comparative | Messages in which a certain actor is criticized while emphasizing and highlighting positive aspects or merits of oneself. |

| Reason of the Attack | |

| Based on data | The criticism or attack is based on data or information, as well as on the statements that the attacked actor has previously made. |

| Emotional | The criticism or attack is based on language that evokes negative emotions or feelings such as fear, outrage, anger, or disappointment. |

| Ethical | Criticisms or attacks question the credibility of a proposal or action carried out by a certain actor. |

| Humorous | The criticism or attack is made from a humorous perspective, to ridicule one or more actors. |

| PP | PSOE | Podemos | IU | C’s | Rajoy | Sánchez | Iglesias | Garzón | Rivera | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSOE | 14.29 | - | 7.69 | 8.33 | 27.27 | - | - | 30 | - | 20 |

| PP | - | 13.75 | 38.46 | 63.89 | 36.36 | - | 20 | 50 | 50 | 20 |

| C’s | - | - | - | 8.33 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Podemos | 14.29 | 10 | - | - | 18.18 | - | 8.57 | - | - | 20 |

| Other political parties | - | 6.25 | - | 2.78 | 18.18 | - | 8.57 | - | 7.14 | 20 |

| Sánchez | - | - | 7.69 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Rajoy | - | 36.25 | 7.69 | - | - | - | 31.43 | - | 7.14 | - |

| Rivera | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Iglesias | 42.86 | 27.50 | - | - | - | - | 28.57 | - | - | - |

| Other politicians | - | 6.25 | 15.38 | 8.33 | - | - | 2.86 | - | 14.29 | - |

| Media/Journalists | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Public organizations | - | - | 7.69 | 2.78 | - | - | - | 10 | 21.43 | - |

| Entrepreneur/Company | - | - | - | 2.78 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Other actors | 28.57 | - | 15.38 | 2.78 | - | - | - | 10 | - | 20 |

| TOTAL | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PP | PSOE | Podemos | IU | C’s | Rajoy | Sánchez | Iglesias | Garzón | Rivera | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | |||||||||||

| Direct | 14.29 | 22.73 | 72.73 | 37.04 | 25 | - | 50 | 28.57 | 61.54 | 66.67 | 37.68 |

| Collateral | 85.71 | 77.27 | 27.27 | 62.96 | 75 | - | 50 | 71.43 | 38.46 | 33.33 | 62.32 |

| Structure of the attack | |||||||||||

| Simple | 57.14 | 22.73 | 45.45 | 66.67 | 12.5 | - | 11.11 | 14.29 | 76.92 | - | 36.96 |

| Comparative | 42.86 | 77.27 | 54.55 | 33.33 | 87.5 | - | 88.89 | 85.71 | 23.08 | 100 | 63.04 |

| Reason of the attack | |||||||||||

| Based on data | 14.29 | 22.73 | 27.27 | 22.22 | 37.5 | - | 11.11 | 28.57 | 15.38 | - | 21.01 |

| Emotional | 85.71 | 27.27 | 54.55 | 55.56 | 25 | - | 44.44 | 71.43 | 38.46 | 100 | 44.93 |

| Ethical | - | 45.45 | 18.18 | 3.7 | 37.5 | - | 33.33 | - | 46.15 | - | 27.54 |

| Humorous | - | 4.55 | - | 18.52 | - | - | 11.11 | - | - | - | 6.52 |

| Critics | Commentaries | Shares | Like | Love | Surprise | Laugh | Sad | Angry | Total Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 601.16 | 2681.64 | 3653.67 | 334.38 | 6.77 | 56.10 | 33.40 | 74.81 | 4159.14 |

| No | 571.60 | 1980.91 | 3762.10 | 447.41 | 7.86 | 58.80 | 18.46 | 26.42 | 4321.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marcos-García, S.; Alonso-Muñoz, L.; Casero-Ripollés, A. The Influence of the Negative Campaign on Facebook: The Role of Political Actors and Citizens in the Use of Criticism and Political Attack in the 2016 Spanish General Elections. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100356

Marcos-García S, Alonso-Muñoz L, Casero-Ripollés A. The Influence of the Negative Campaign on Facebook: The Role of Political Actors and Citizens in the Use of Criticism and Political Attack in the 2016 Spanish General Elections. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(10):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100356

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcos-García, Silvia, Laura Alonso-Muñoz, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2021. "The Influence of the Negative Campaign on Facebook: The Role of Political Actors and Citizens in the Use of Criticism and Political Attack in the 2016 Spanish General Elections" Social Sciences 10, no. 10: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100356

APA StyleMarcos-García, S., Alonso-Muñoz, L., & Casero-Ripollés, A. (2021). The Influence of the Negative Campaign on Facebook: The Role of Political Actors and Citizens in the Use of Criticism and Political Attack in the 2016 Spanish General Elections. Social Sciences, 10(10), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100356