1. Introduction

Emerging adulthood is a period when individuals between 18 and 25 years old evolve and acquire commitments that structure their adult lives, such as long-term couple relationships, parenting, and stable work (

Arnett 2014). A challenge that couples face is the need to be aware of the interdependence between individual aspirations and commitment in long-term couple relationships (

Shulman and Connolly 2013;

Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2014). Going from a more casual to a more committed relationship implies learning to know the other more deeply and how to address and resolve disagreements (

Tuval-Mashiach and Shulman 2006). Studies have confirmed that adults confront challenges like fear of rejection and abandonment by their partners (anxiety) as well as negative representations of others and the tendency to feel uncomfortable with intimacy (avoidance) (

Mikulincer et al. 2002). These two factors are associated with greater levels of psychological anguish (

Davila and Bradbury 2001).

Studies have shown that levels of mindfulness are associated with other psychosocial tendencies like empathetic awareness and taking perspectives that strongly predict satisfactory relationships (

Kimmes et al. 2020;

Quinn-Nilas 2020) and diminish the risk of breakups (

Saavedra et al. 2010). The functioning and wellbeing of close ties with others also depend on the willingness and capacity to forgive, sacrifice, and refrain from acting during conflict, as well as accepting the other (

Karremans et al. 2017). Consequently, understanding the role of mindfulness can bring order and parsimony to the current state of multiple interventions as well as clarify the connections between the provided treatment and the various results (

Kazdin 2007), making it necessary to investigate other mechanisms of potential change in mindfulness in other areas of life, considering that little is known about its role in intimate relationships (anxiety and avoidance) and psychological wellbeing.

1.1. Anxiety and Avoidance in Intimate Relationships

Hazan and Shaver (

1987) conceptualized romantic love as an attachment process similar to the parent–child attachment process. The main propositions about this similarity were as follows. 1. The emotional and behavioral dynamics are governed by the same biological system; for example, adults feel safer when their partner is close, accessible, and receptive, that is, it becomes a safe base from which they can explore the environment around them. 2. In romantic relationships, the main attachment patterns, which can be considered as loving styles (for example: anxious and avoidant), are also observed. 3. Early caregiving experiences act as points of reference and influence, at least in part, for how people behave in their adult romantic relationships. 4. Romantic love implies the interaction of attachment, care, and sex (

Fraley and Shaver 2000).

Research has shown that individual differences in adult attachment in the framework of intimate relationships can be understood through two dimensions: anxiety and avoidance (

Brennan et al. 1998;

Guzmán-González et al. 2019). Anxiety refers to worrying about rejection, the fear of abandonment, and doubt about one’s personal worth due to a negative self-image (

Mikulincer et al. 2002). In terms of adaptability, anxiety seeks not only to maintain proximity with the attachment figure but also to be watchful of one’s surroundings to detect any threat and show anguish to obtain protection. This hyperactivation can be the result of an inconsistent bond or overprotection by the attachment figure (

Díaz-Cutraro et al. 2020;

Hepper and Carnelley 2012).

Avoidance refers to how individuals avoid closeness and intimacy. The individual has a negative construction of the other, reducing the importance of the relationship and consequently seeking not to depend on him or her. It is an adaptation mechanism to maintain distance from the attachment figure, without showing anguish. It serves to process signs of rejection and represents a tendency towards compulsive self-sufficiency (

Hepper and Carnelley 2012). In contrast to the hyperactivation observed with anxiety, systems of attachment deactivate with avoidance, which is the result of rejection or coldness on the part of the attachment figure (

Mikulincer et al. 2003). Both anxiety and avoidance can be measured with self-registered scales (

Brennan et al. 1998).

To understand how both anxiety and avoidance can affect the construction of satisfying romantic relationships, we must understand how the bond is built in the couple.

Zeifman and Hazan (

1997) describe the bond formation stages in adult romantic relationships, indicating that there are several parallels between this process and both mother–child and children’s responses to separation and loss. They point out that there are three phases in bond building. (1) The first is preattachment, where there is an initial attraction, flirting, and courtship; individuals evaluate and allow each other to evaluate.

Kirkpatrick (

1998) adds that they are specifically evaluated with respect to their suitability as a long-term partner and their potential as a father or mother, rather than as a potential attachment figure. (2) The second is attachment-in-the-making, which is where “falling in love” arises, the emotional bond is established, there is a higher level of self-disclosure as a test of commitment, and sexual behavior constitutes a factor that promotes the development of the emotional bond. Furthermore, at this stage, people want their partners to be motivated to stay in a relationship out of love and not out of consideration for an exchange of favors (

Kirkpatrick 1998). (3) The third is clear-cut attachment; it is the final phase, and it reflects that the emotional bond and the commitment of the long-term relationship have been established; it includes the functions of safe haven and safe base, some of the characteristics of an attachment figure are assumed, such as providing comfort and support in difficult times, and there is mutual trust and a reciprocal alliance. Therefore, both anxiety and avoidance can interfere with this process, reducing the possibility of moving towards the third phase.

1.2. Mindfulness and Psychological Wellbeing

In psychology, mindfulness is a capacity inherent to human awareness that allows individuals to deal with events in the moment without judging and accepting them as they emerge in their consciousness (

Baer et al. 2004). Mindfulness has been adopted in contemporary psychology as a focus to increase awareness and respond skillfully to mental processes that contribute to mental anguish and maladjusted behavior (

Bishop et al. 2004;

Chiodelli et al. 2018). Mindfulness has also been defined as a state that is reached by means of a set of techniques that can be acquired through training. Acceptance therapy indicates that all human beings can cultivate a state of mindfulness through the practice of different techniques (

Cebolla et al. 2012).

Studies have shown the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) to improve psychological wellbeing (

Baer et al. 2008;

Fumero et al. 2020;

Hasselberg and Rönnlund 2020). Research has been directed at mediators and mechanisms of attention that favor change (

Baer 2009;

Baer et al. 2012;

Charters 2013). One study has provided evidence that increased attention and self-compassion through mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) mediated changes in depressive symptoms after a 15-month follow-up (

Kuyken et al. 2010). As well as its effects in psychotherapy, mindfulness can contribute, in general, to improving daily life and adaptive functioning, alleviating suffering, and helping to manage and cope with stress and crisis (

Kazdin 2007).

To assess mindfulness as a process, the Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) is available (

Baer et al. 2006). The FFMQ serves to identify the most important abilities to predict the reduction of symptoms and increase wellbeing. It also describes the mechanisms through which these beneficial effects are produced (

Cebolla et al. 2012;

Chien et al. 2020;

Pelham et al. 2019). In accordance with its operationalization in five facets, mindfulness is the capacity to (a) observe, (b) describe (ability to put into words what one is experiencing), (c) act with awareness (ability to direct attention to the present moment and one’s actions here and now, which is the opposite of acting automatically), (d) not judge (the ability to not judge internal experiences), and (e) not react (the ability to allow and accept the onset and flow of emotional or mental reactions without avoiding them or being overwhelmed by them) (

Cash and Whittingham 2010;

Meda et al. 2015). A better understanding of the relationship between specific facets of mindfulness and the dimensions of anxiety and avoidance in intimate relationships can improve the development of psychological wellbeing.

1.3. Research Questions

The objectives of this study are (1) to identify if determined levels of dispositional mindfulness act as protector factor between psychological wellbeing and anxiety, and avoidance experienced in intimate relationships in emerging adulthood, and to (2) identify the specific facets of mindfulness that have the most significant protector effect between psychological wellbeing and anxiety and intimacy avoidance experienced in intimate relationships in emerging adulthood.

2. Method

2.1. Research Paradigm

This study is conducted from the perspective of postpositivist critical realism. It assumes an objective reality that can only be understood imperfectly and probabilistically (

Guba and Lincoln 1994). This research has a quantitative focus, with a crosscutting correlational and observational design (

Hernández et al. 2010). This design was chosen to observe and register variables without intervening in the natural course of events. As well, the measurements are unique and register variables quantitatively (

Manterola and Otzen 2014).

2.2. Participants

The study was conducted in the city of Quito, Ecuador. Participants were undergraduate university students who were recruited by snowball sampling. People were invited to participate voluntarily by advertising the study through social media, visits to higher education institutions, posters, and flyers. The sample was composed of 391 university students between 18 and 25 years old, all residents of the city of Quito, 136 men (mean age = 20.93 years old), of which 44 were in intimate relationships. There were 255 women (mean age = 21.05 years old), of which 137 were in intimate relationships. Regarding the marital status of the participants, 377 were single (96.2%), five were married (1.3%), five were divorced (1.3%), and four were in a common union (1%). Regarding their nationality, 387 were Ecuadorians and 4 were foreigners.

The sampling was done by convenience. Inclusion criteria included being aged between 18 and 25 years, having or having had some type of relationship, and not having any experience in mindfulness or meditation. Exclusion criteria were being followed by a psychologist or psychiatrist for any mental health problems, having recently experienced any important losses, and having a physical condition that may influence the subject’s commitment to participating in the research.

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were invited to a face-to-face meeting where the purpose of the study was explained to them. Those who agreed to participate in the study signed informed consent forms, and the data were collected through the pen-and-paper technique, where questionnaires were printed and handed to them so they could complete them. The instruction to answer the couple questionnaire was to think of a current or the most recent relationship.

2.3. Measures and Procedure

A sociodemographic data file was designed for this study and the Experiences in Close Relationships, Five-Facet Mindfulness, and Ryff’s Psychological Wellbeing questionnaires were used. Given that the questionnaires were not adapted to the Ecuadorian population, confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) was carried with the sample of this study on the structure of factors described. The chi-square test (

X2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) were considered in valuing the adjustment of the model. CFI and TLI values equal to or higher than 0.90 and SRMR and RMSEA values of less than 0.08 were considered indicators of adequate adjustment (

Hu and Bentler 1999).

Sociodemographic data file: A register was prepared to gather sociodemographic information on the participants in the study, such as sex, age, neighborhood of residence, and years of schooling.

Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (

FFMQ, Baer et al. 2006). This questionnaire measures the tendency to have a mindful approach. It is composed of 39 items. A Spanish version that had been adapted to the Chilean population was used (

Schmidt and Vinet 2015). The scale was a Likert-type that went from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). The minimum score is 39 points, and the maximum is 195. The items are grouped into five factors: observation, description, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reactivity. The indices obtained in the CFA indicate a good adjustment: (

X2 = 158.95; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.06; RMSEA = 0.05). The Cronbach alpha values obtained with this sample were observation—0.79, description—0.84, acting with awareness—0.86, non-judging—0.84, and non-reactivity—0.60.

Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR,

Brennan et al. 1998). This scale evaluated two dimensions: anxiety about abandonment (anxiety) and intimacy avoidance (avoidance). Each subscale consisted of 18 items that were measured by a Likert-type scale with 7 points, where 1 was “totally disagree”, 4 was “neither agree nor disagree”, and 7 was “totally agree”. A higher score indicates a higher level of anxiety and/or avoidance. The CFA showed a good adjustment of the model to the data (

X2 = 152.019; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.93; SRMR = 0.07; RMSEA = 0.07). Both avoidance (α = 0.85) and anxiety (α = 0.89) presented good levels of reliability.

Psychological Wellbeing Scale (PWS,

Ryff 1989). This scale evaluates positive attributes of psychological wellbeing. The 39-item scale (

Van Dierendonck 2005) was adapted to Spanish and reduced to 29 items (

Díaz et al. 2006) and scored by a Likert-type scale that goes from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally disagree). The scale contains six subscales: self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, and purpose in life. These scales are combined to obtain a global score for wellbeing. The values obtained with the CFA show that the model presents a moderately acceptable level of adjustment (

X2 = 115.581; CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.89; SRMR = 0.07; RMSEA = 0.08). The global Cronbach alpha score was 0.91, with 0.80 for self-acceptance, 0.70 for positive relationships, 0.70 for autonomy, 0.60 for environmental mastery, 0.54 for personal growth, and 0.80 for purpose in life. There was a low level of reliability for the dimensions of environmental mastery and personal growth.

2.4. Data Analysis

The possible protector effects of the five facets of mindfulness: observation, description, acting with awareness, non-judging, and non-reactivity on the negative aspects (avoidance and anxiety) and dimensions of wellbeing (self-acceptance, positive relationships, purpose in life, etc.) were identified using linear regressions (

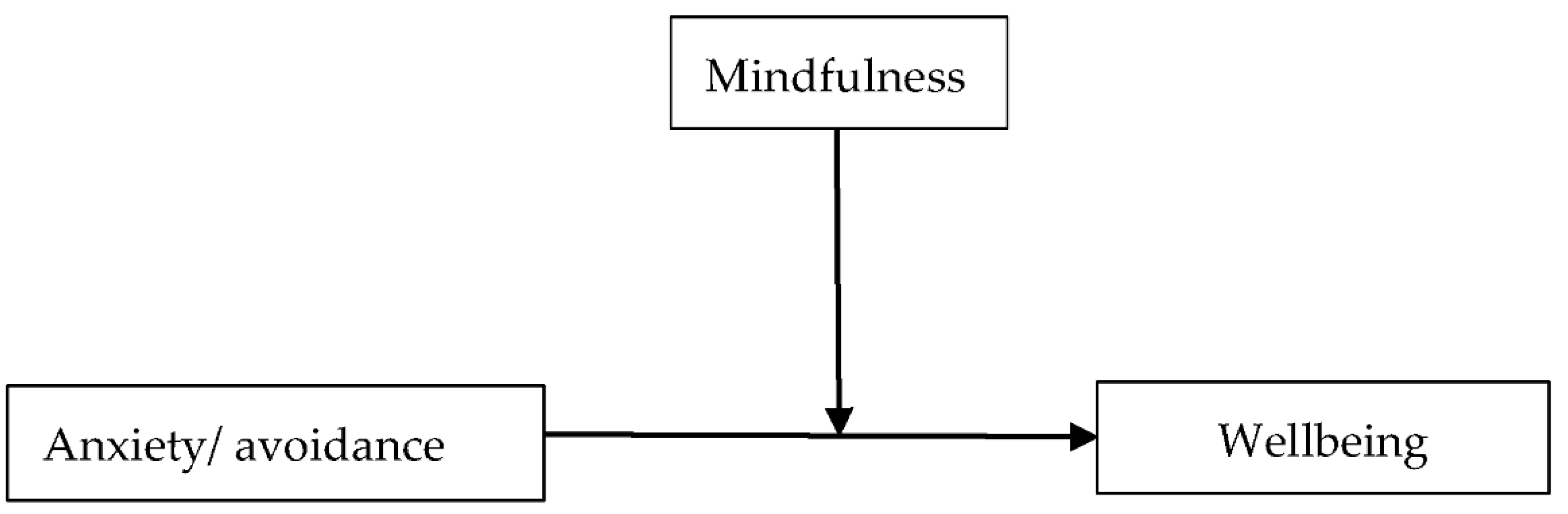

Hayes 2013) between negative aspects as independent variables and the dimensions of wellbeing as dependent variables, firstly testing if mindfulness moderates the relationship between the negative dimensions and wellbeing, as represented in

Figure 1.

Bootstrap intervals were obtained to verify the significance of the mediating effects at a level of significance of 5%. PROCESS macro in SPSS software, version 22 (

Hayes 2014) was used.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Sub-Committee on Ethical Investigation into Human Beings of the Central University of Ecuador (SEISH-UCE), 27 February 2018, Code 0006-FCP-D-2017. Informed consent, regarding objectives and data publication, was obtained from all participants included in the study.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the results of the descriptive analysis of the study variables in this sample. As shown in the table, the facet of acting with awareness had the highest score and non-judging had the lowest. The highest mean index of psychological wellbeing was autonomy, and the lowest was positive relationships.

Our first hypothesis is that the variables of avoidance and anxiety are related to mindfulness and psychological wellbeing. To determine if this relationship exists, we carried out Pearson-type correlation analyses.

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients and levels of significance.

The results of the correlation test show that anxiety and avoidance are negatively and significantly related to mindfulness and psychological wellbeing. The correlations are low and moderate, and all are significant, with the exception of avoidance with anxiety. The analysis showed that mindfulness and wellbeing are positively and significantly related, the correlations between them being high, as shown in

Table 2.

Based on the correlations, we hypothesize that mindfulness plays a protector role in avoidance and anxiety experienced in intimate relationships, as well as in psychological wellbeing.

To test whether mindfulness moderates the relationship between anxiety and wellbeing and/or avoidance and wellbeing, each analysis is performed separately according to the model represented in

Figure 1, controlling for age and sex.

The results, as seen in

Table 3 and

Table 4, show that there is no moderation, as the interaction effects are not significant in either of the two models, either for the independent variable that corresponds to avoidance (β

interac = 0.00,

p = 0.87) or the one that encompasses anxiety (β

interac = 0.00,

p = 0.66).

Moreover, when reviewing the effect that each negative dimension has on wellbeing, it is seen that it is still significant (

Table 5).

However, to examine in more detail the influence that mindfulness skills have on the relationship between negative dimensions and wellbeing, subjects were categorized into those with low and high levels of mindfulness; this was determined by dividing the observed range of values of the variable into two groups and then categorizing each subject depending on whether their mindfulness score was within the lowest or highest half of the values. It was first checked whether, in the presence of negative dimensions, the mindfulness category is significant for predicting wellbeing, using a regression model that includes these three variables and controlling for sex and age variables. According to this model, which results can be seen in

Table 6, the variables avoidance (β = −0.487,

p < 0.001), anxiety (β = −0.461,

p < 0.001), and categorized level of mindfulness (β = 20.835,

p < 0.001) were significant.

Hence, to better explore the differences in the influence that avoidance and anxiety have on wellbeing, regression models were applied for each level of mindfulness group separately (high and low levels). The difference between this approach and the one of moderation is mainly to consider regression models where both variables (anxiety and avoidance) are covered jointly and to explore how they are related to wellbeing in both groups. The results of these models can be seen in

Table 7 and

Table 8.

It is seen that in both models, both avoidance and anxiety are significant in predicting the level of wellbeing (p < 0.001); however, by comparing the magnitude of the relationship between each negative dimension and wellbeing (expressed as sensitivity through beta coefficients), it is seen that this is descriptively lower for the group of subjects with high levels of mindfulness, both for avoidance and anxiety. This would suggest that although both dimensions are still significant for wellbeing, their impact would be lower in subjects with high levels of mindfulness. This is also suggested by the correlations between anxiety and wellbeing, obtained by each group. While the correlation between avoidance and wellbeing is almost the same in both groups (r = −0.27, p < 0.001), on the other hand, its magnitude is higher between anxiety and wellbeing in subjects with lower mindfulness levels (r = −0.46, p < 0.001) than in subjects with higher mindfulness levels (r = −0.2, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

This study examined the importance of mindfulness as a protective factor in intimate relationships that experience anxiety or avoidance and as a factor that promotes psychological wellbeing in a nonclinical sample composed of emerging adults.

Although mindfulness does not moderate the relationship that anxiety and avoidance have with wellbeing, the fact of observing this descriptive difference in the beta coefficients and correlations invites us to continue carrying out research in this regard. This analysis can be replicated in other samples, for example, with subjects with a certain experience in the practice of meditation, to see if the fact of having trained mindfulness skills (dimensions) ends up showing a different relationship between negative dimensions and wellbeing compared to subjects who have no experience of this type of practice.

The results of this study agree with others in which mindfulness is associated with higher levels of happiness and less stress in relationships and effectiveness in coping with stress (

Carson et al. 2004), as well as higher levels of satisfaction with relationships, greater ability to respond constructively to relationship stress, positive change in the perception of the relationship, and higher quality of communication during interactions (

Barnes et al. 2007;

Quinn-Nilas 2020).

Insecure attachments (anxiety or avoidance) are associated with hostility, lower quality, and less stability in relationships, high levels of depression and anxiety, unhealthy behavior, less productive career choices, and lower performance in work (

Shaver and Mikulincer 2007). Insecure attachment is operationally defined by high scores in two dimensions: anxiety and avoidance. Anxiety is characterized by fear of rejection and the absence of love, anger because of the threat of separation, and a need for approval and love. Avoidance is characterized by discomfort with closeness and interdependence, preference for emotional distancing, distrust in the relationship, and extreme self-sufficiency (

Shaver et al. 2007). Consequently, influencing these facets contributes to reducing levels of anxiety and avoidance and promotes more satisfying couple relationships and psychological wellbeing.

Although it was not possible to identify which of the mindfulness facets has the most impact as a protective factor, there are studies in which relevant information has been found in this regard. For example, it was found that in situations of infidelity, lower levels of the facets acting with awareness and non-judging the internal experience were related to higher levels of unforgiveness (

Johns et al. 2015).

Another study found that the facet of observation in relation to psychological adjustment varies according to the level of meditation that is practiced (

Baer et al. 2008), which is associated negatively with psychological health (

Bodenlos et al. 2015). This suggests that observing is more associated with cognitive or emotional fusion behavior if not accompanied by description, which implies distancing one’s self and forming a perspective of the situation. It has also been found that, effectively, the subscales of non-judging and non-reactivity have a stronger mediating effect among individuals who participate in mindfulness-based programs and perceived stress, depressive symptoms and positive states (

Lönnberg et al. 2020), as well as the symptomology of individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (

Mitchell et al. 2019) and that were significantly and positively associated with emotional wellbeing (

Bodenlos et al. 2015).

At a theoretical level, deepening the study of avoidance and anxiety in intimate relationships broadens our understanding of the Theory of Attachment and allows the interpretation of attachment as a complex and dynamic process, as well as the heterogeneity in experiences of attachment (

Galán 2016). Mindfulness can be a mechanism of change to redefine our understanding of relationships with caregivers during childhood and act with awareness here and now to favor psychological wellbeing.

As limitations of our study, we had to use only self-registered measurements, which could be combined with more objective methods such as physiological measurements and neurobiological and behavioral assessments to provide a multimodal system of evaluation of the levels of mindfulness (

Chien et al. 2020). The transversal design does not allow for determining causal relationships among the variables. As the sample was composed of nonclinical subjects, limited generalizations can be made of the findings. Another limitation of this study is that other latent variables were not considered for analysis. There are several confounding factors such as relationship status, socio-economic status, health behaviors (e.g., alcohol consumption), and health status, including morbidities. They were not considered necessary for the model we were trying to test; however, we consider them relevant for future analysis. Future studies could use longitudinal designs that consider the practice of mindfulness in couple relationships to determine if the conclusions of this study are supported.

5. Conclusions and Implications

Future studies should consider other factors of intimate relationships besides anxiety and avoidance, factors that improve conjugal intimacy and favor the construction of more satisfying, stable, and functional relationships (

Kamali et al. 2020). In addition, it would also be interesting to evaluate whether mindfulness can be a key component for intervention in codependent relationships (

Aristizábal 2020) as well as for reducing violent relationships (

Di Napoli et al. 2019;

World Health Organization 2012).

According to these findings, evaluating mindfulness in relationships allows for investigating its role in intimate relationships and developing and refining training programs to develop more conscious relationships and to train therapists to optimize therapeutic change with more strategies to trigger processes of critical change, identify facets on which efficacy of a determined treatment can depend, and finally understand the processes through which treatment operates (

Chien et al. 2020;

Kazdin 2007).

Deepening our knowledge of possible active principles of mindfulness would allow us to identify practices that increase the capacity for mindfulness and determine how these practices affect the physical and psychological wellbeing of individuals (

Baer 2009;

Grossman 2019) and their relationships.

To arrive at more definitive conclusions about the facets of mindfulness and their relationship to the variables of anxiety and avoidance and those of psychological wellbeing requires replications of this type of study to confirm or deny the findings. This requires using samples with meditators from the general community, including same-sex partners and couples in which there have been violent interactions.