Economic Poverty: Does the Break-Up of Families Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction and Literature Review

2. Discussion of the Socio-Economic Framework

2.1. Social Changes in Europe

2.2. Trend in Household’s Structure and Poverty

3. Methods and Results

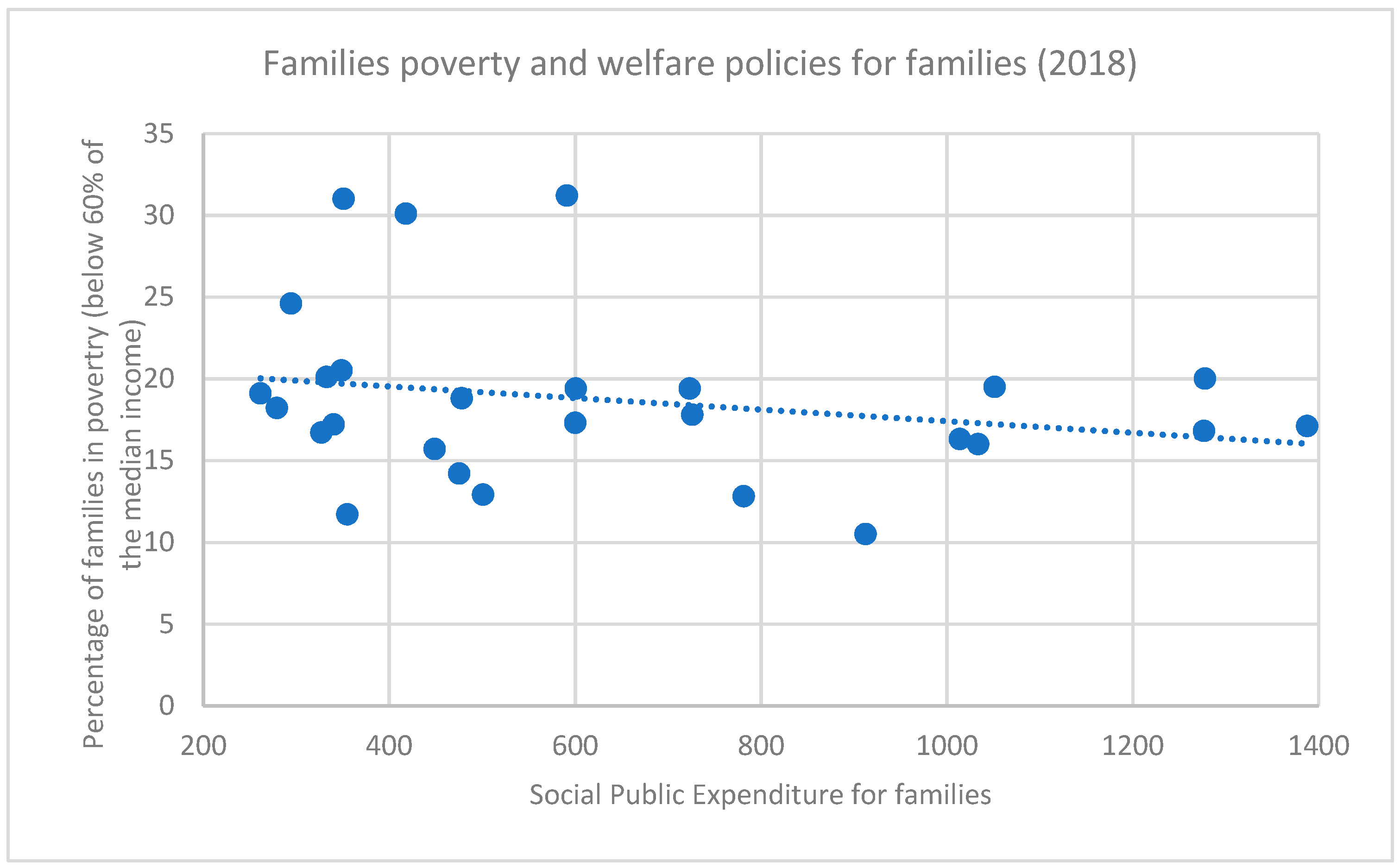

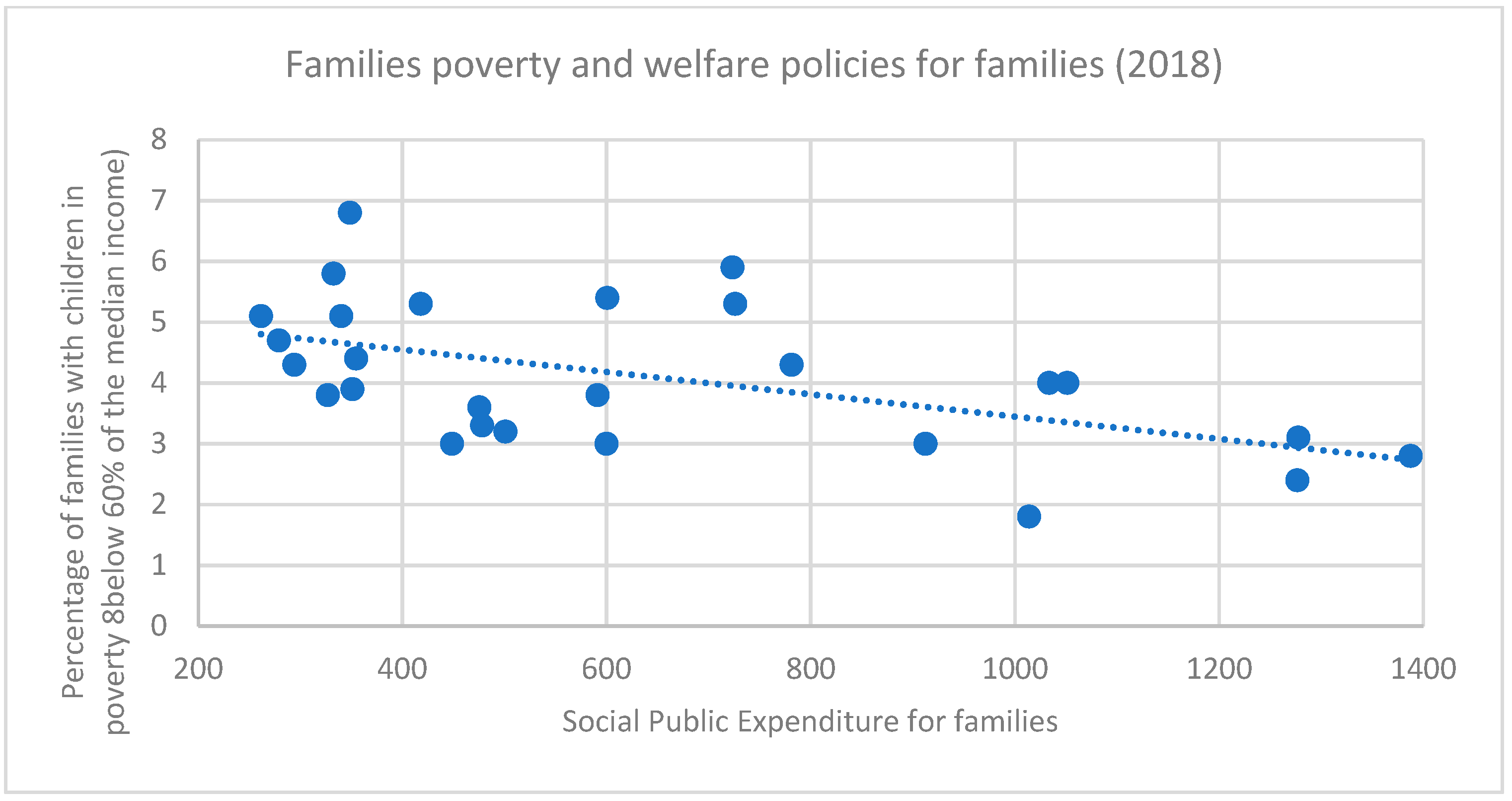

3.1. Poverty and Families

3.2. Econometric Analysis: Method and Results

- Per capita GDP: several studies show that, as average income rises, the number of people in poverty decreases (for a recent empirical analysis, see Dollar et al. 2016); an alternative variable, highly correlated with GDP, is unemployment (Saunders 2002). We also consider female unemployment because of its role especially for single mother families (Cancian and Haskins 2014). The level of per capita GDP is also highly correlated with social expenditure—social public expenditures for families included—which affects individual poverty through its effects on household poverty.

- The Gini index, that summarizes the concentration of income: not only the level of average income, but also the concentration of GDP affects poverty (Karagiannaki 2017). The relationship found in the literature is a negative one. In our analysis, we use the Gini index of disposable income.

- The female unemployment rate.

- Social cash and in-kind benefits for families.

- Education attainments are believed and found to be inversely correlated to poverty (Barham et al. 1995; Hofmarcher 2019). We use the share of people with at least a secondary education degree.

- In addition to the socioeconomic variables used to explain individual poverty, we use variables related to the household structure, as usually implemented when analyzing poverty at the family level (see Table A2).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Data and Materials

| Data Description and Reference Years | Sources | Links |

|---|---|---|

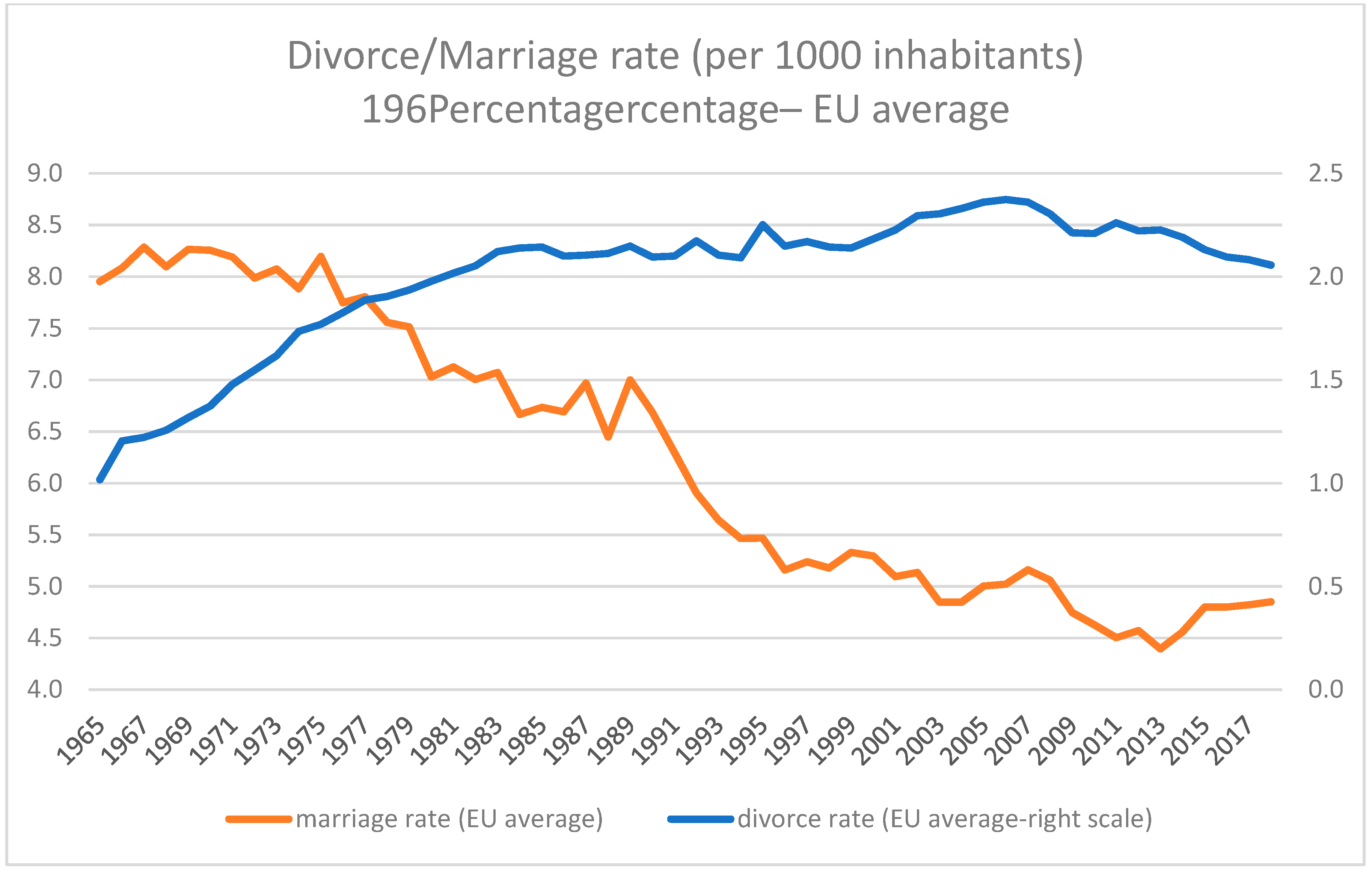

| Divorces (crude divorce rate) = ratio of the number of divorces during the year to the average population in that year (data expressed per 1000 persons). 1965–2018 | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=demo_ndivind&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Marriages (crude marriage rate) = ratio of the number of marriages during the year to the average population in that year (data expressed per 1000 persons). 1965–2018 | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

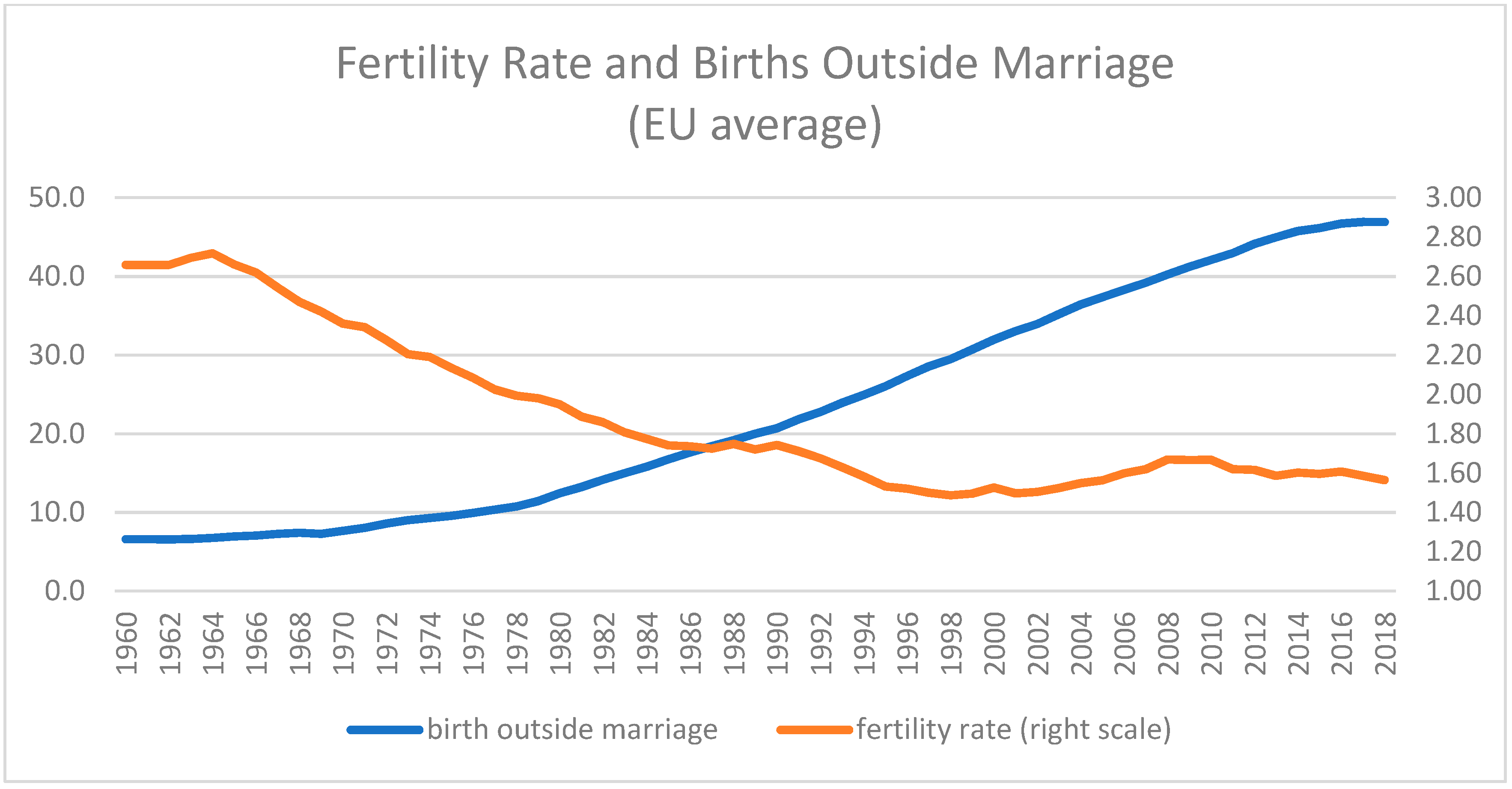

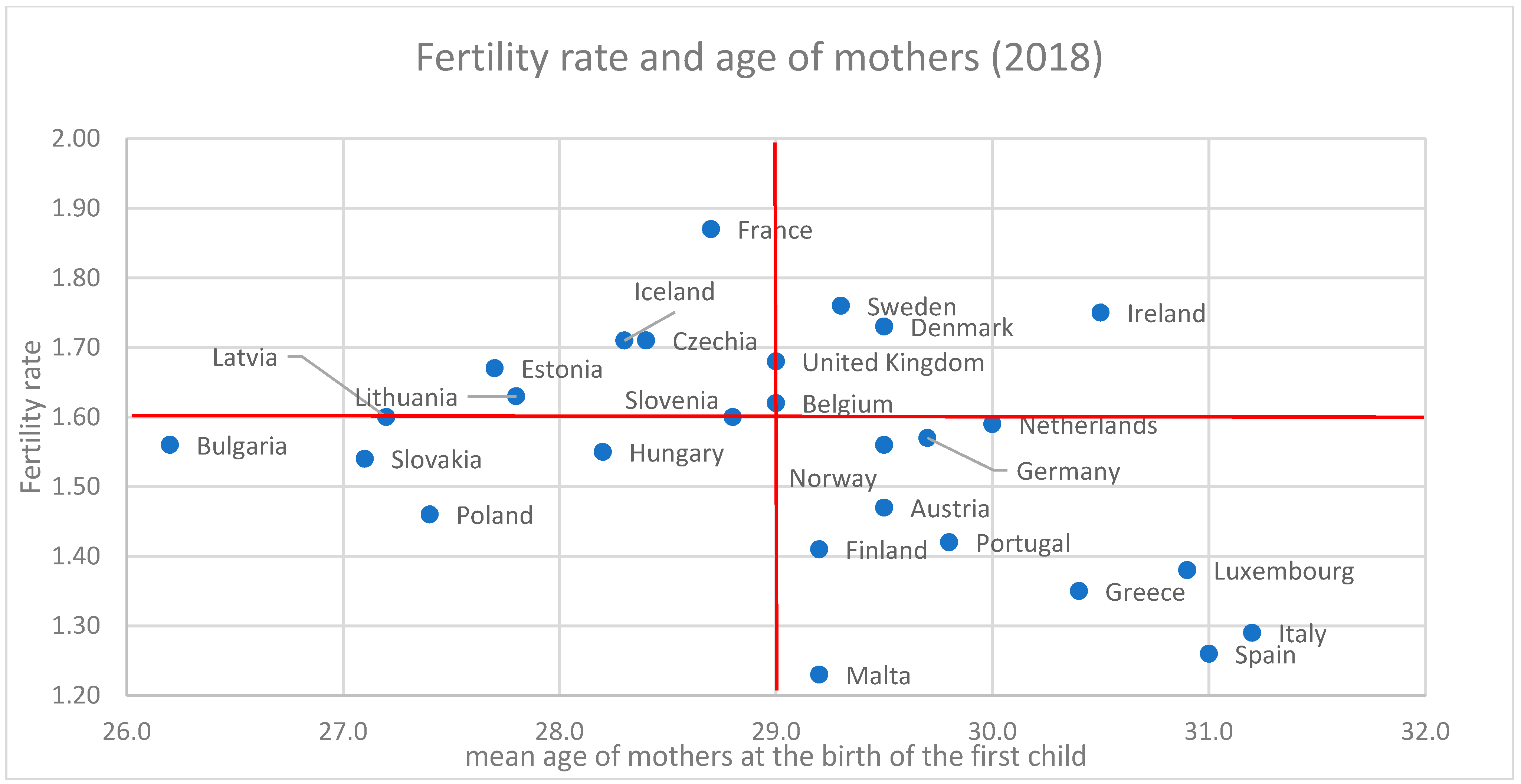

| Fertility rate = average number of children born per woman over a lifetime. 1960–2018 | OECD- Family Database | https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Births outside marriage (percentage value) | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Distribution of births by birth order = percentage of births that are first, second, third or higher. 1980 and 2018 | OECD-Family Database | https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Age of mothers = average age of mothers at the birth of the first child. 1980 and 2018 | OECD-Family Database | https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

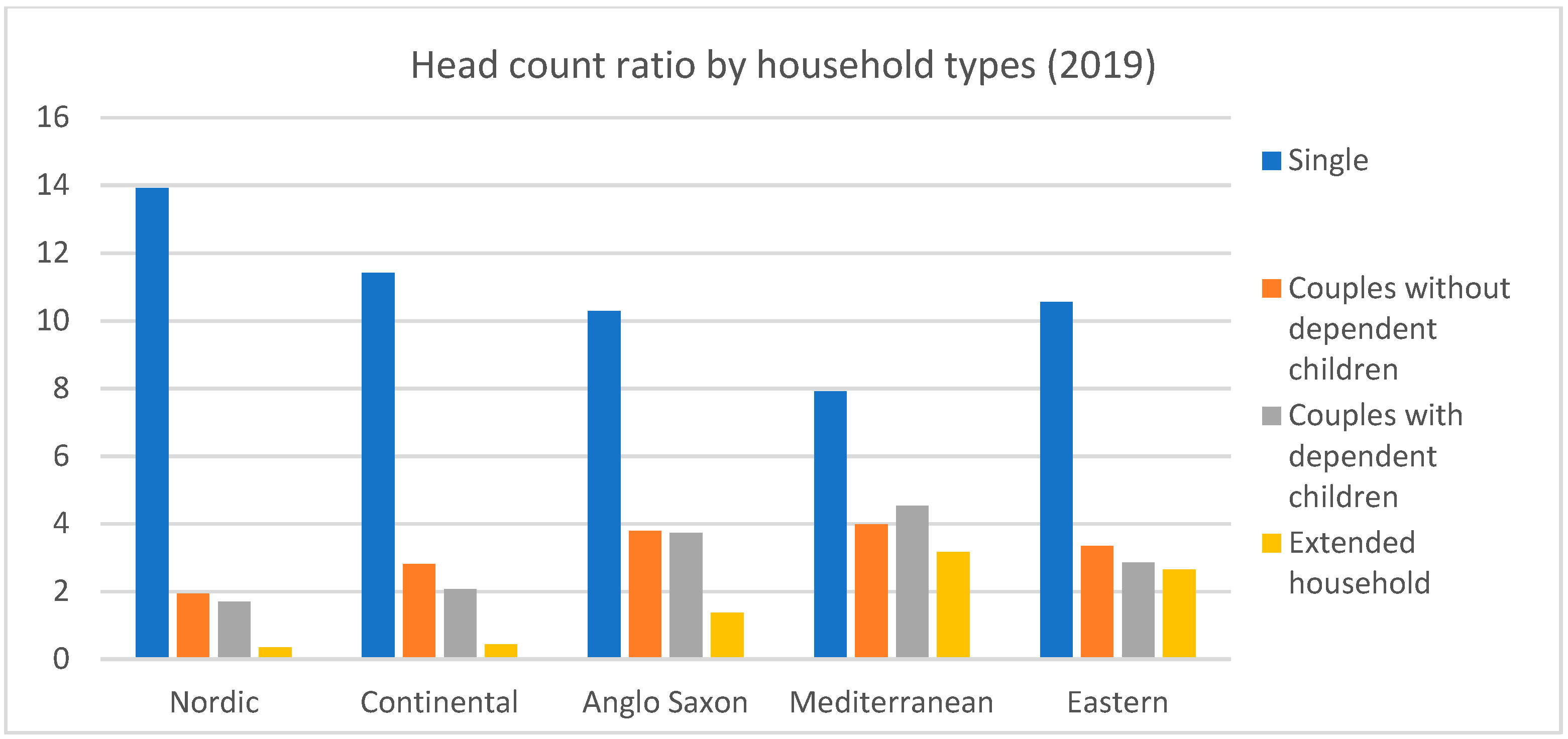

| Household composition: percentage of couples with/without children percentage of singles with/without children percentage of households composed by three or more adults (extended households) with/without children. 1994, 2005, 2015, 2018, 2019 | Eurostat (years 2018 and 2019) | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_lvph02&lang=en%20(for%20years%201994,%202005%20and%202015) (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Eurostat (years 1994, 2005 and 2015) | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=hbs_car_t313&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). | |

| Head count ratio (AROP) = percentage of persons with equivalised disposable income below the 60% of median income. 2010 and 2019 | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_li02&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Distribution of households by household type and income level (percentage of households with disposable income below 60% of median income = H CR household) 2010, 2018 and 2019 | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_lvph04&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Gross Domestic Product | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=nama_10_pc&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Education = percentage of persons (18–74 years) with secondary and upper secondary (no tertiary) education 2018, 2019 | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=edat_lfs_9903&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Social Public Expenditure (cash and in kind) for families | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=spr_exp_ffa&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Gini Index after tax and transfers | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_di12&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Unemployment rate = percentage of unemployed persons 15–74 years with respect to the 15–74 years active population (labour force) | Eurostat | https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=une_rt_a&lang=en (accessed on 9 June 2021). |

| Countries | Single without Dependent Children | Single with Dependent Children | Couples without Dependent Children | Couples with 1 Dependent Children | Couples with 2 Dependent Children | Couples with 3 or More Dependent children | Extended Family (3 or More Adults) without Dependent Children | Extended Family (3 or More Adults) with Dependent Children | Families without Children | Families with Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | 34.7 | 6.2 | 28.8 | 8.1 | 9.6 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 3.5 | 68.1 | 31.9 |

| Bulgaria | 34.3 | 2.9 | 25.1 | 8.9 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 69.5 | 30.5 |

| Czech Republic | 29.8 | 4.2 | 29.4 | 10.6 | 11.6 | 2.4 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 67.2 | 32.8 |

| Denmark | 43.9 | 5.5 | 29.3 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 75.6 | 24.4 |

| Germany | 42.0 | 4.3 | 30.7 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 76.3 | 23.7 |

| Estonia | 41.8 | 4.1 | 25.2 | 8.8 | 8.1 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 4.0 | 72.2 | 27.8 |

| Ireland | 25.8 | 7.2 | 25.6 | 8.3 | 11.6 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 6.4 | 59.8 | 40.2 |

| Greece | 25.7 | 1.3 | 28.7 | 9.1 | 9.8 | 4.0 | 15.1 | 6.3 | 69.6 | 30.4 |

| Spain | 25.7 | 3.3 | 28.3 | 10.1 | 10.9 | 2.3 | 13.2 | 6.3 | 67.2 | 32.8 |

| France | 38.6 | 5.9 | 28.9 | 8.2 | 10.4 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 70.4 | 29.6 |

| Italy | 33.0 | 4.0 | 25.7 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 1.9 | 11.9 | 4.7 | 70.5 | 29.5 |

| Cyprus | 20.8 | 3.2 | 32.7 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 5.3 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 62.9 | 37.1 |

| Latvia | 35.4 | 4.9 | 27.3 | 9.5 | 7.0 | 2.7 | 7.6 | 5.6 | 70.2 | 29.8 |

| Lithuania | 38.3 | 6.2 | 25.8 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 1.8 | 6.7 | 4.4 | 70.8 | 29.2 |

| Luxembourg | 33.1 | 4.4 | 29.2 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 2.9 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 67.4 | 32.6 |

| Hungary | 33.0 | 4.4 | 29.3 | 8.9 | 7.6 | 3.3 | 8.1 | 5.4 | 70.4 | 29.6 |

| Malta | 27.3 | 3.6 | 29.6 | 11.1 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 10.2 | 8.2 | 67.1 | 32.9 |

| Netherlands | 38.5 | 3.5 | 31.0 | 7.8 | 9.7 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 72.8 | 27.2 |

| Austria | 37.4 | 2.5 | 28.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 3.4 | 7.9 | 4.3 | 74.1 | 25.9 |

| Poland | 25.2 | 1.6 | 25.9 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 2.4 | 14.3 | 12.8 | 65.4 | 34.6 |

| Portugal | 22.8 | 4.8 | 31.1 | 13.2 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 11.6 | 6.0 | 65.5 | 34.5 |

| Slovenia | 29.6 | 3.7 | 25.6 | 9.9 | 12.6 | 3.3 | 10.4 | 4.9 | 65.7 | 34.3 |

| Slovak Republic | 18.3 | 2.0 | 27.8 | 8.6 | 11.5 | 2.5 | 16.1 | 13.0 | 62.3 | 37.7 |

| Finland | 44.7 | 3.9 | 30.2 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 77.0 | 23.0 |

| Sweden | 46.6 | 5.7 | 25.9 | 6.7 | 8.1 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 74.4 | 25.6 |

| Iceland | 36 | 6.1 | 24.7 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 5.5 | 5 | 4.9 | 65.9 | 34.4 |

| Norway | 45.6 | 5.7 | 26.5 | 6.8 | 8.4 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 73.9 | 26.1 |

| United Kingdom | 30.5 | 5.6 | 31.4 | 9 | 9.5 | 3.4 | 7 | 3.7 | 68.9 | 31.1 |

| 1 | In this paper we use indifferently the terms household and family overcoming the following technical definitions. A household is defined by Eurostat as a social unit having common arrangements; sharing household expenses or daily needs in a shared common residence. A household includes either one person living alone or a group of people, not necessarily related as in the family. |

| 2 | The data only refer to “private households” excluding collective or institutional households” such as: hospitals, old people’s homes, residential homes, prisons, military barracks, religious institutions, boarding houses and workers’ hostels, etc. As specified above (see note 1), we refer to the Eurostat definition using indifferently the terms household and family. |

| 3 | In the Eurostat database dependent children are defined as individuals aged 0–17 years and 18–24 years if inactive and living with at least one parent. In this paper we use the term “children” or dependent children indifferently. |

| 4 | The equivalized disposable income is the total income of a household, after tax and other deductions, that is available for spending or saving, divided by the number of household members converted into equalized adults; household members are equalized or made equivalent by weighting each according to their age, using the so-called modified OECD equivalence scale giving 1 point to the first adult, 0.5 to the second and each subsequent person aged 14 and over, 0.3 to each child aged under 14. |

| 5 | The European Social Protection Committee uses the AROP, the SMD and the WI indicators. |

| 6 | Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Norway, United Kingdom. |

| 7 | Analogous results are obtained using the overall unemployment rate. |

References

- Aassve, Arnstein, Franceso C. Billari, Stefano Mazzucco, and Fausta Ongaro. 2002. Leaving home: A comparative analysis of ECHP data. Journal of European Social Policy 12: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aassve, Arnstein, Maria A. Davia, and Maria Iacovou. 2005. Does Leaving Home Make You Poor? Evidence from 13 European Countries. ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2005-24; Colchester: University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER). [Google Scholar]

- Aassve, Arnstein, Maria A. Davia, Maria Iacovou, and Stefano Mazzucco. 2007. Does Leaving Home Make You Poor? Evidence from 13 European Countries. European Journal of Population 23: 315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aassve, Arnstein, Maria Iacovou, and Letizia Mencarini. 2006. Youth poverty and transition to adulthood in Europe. Demographic Research 15: 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizer, Anna, Shari Eli, Joseph Ferrie, and Adriana Lleras-Muney. 2016. The Long-Run Impact of Cash Transfers to Poor Families. American Economic Review 106: 935–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarante, Veronica, and Martin Brun. 2018. Cash transfers in Latin America: Effects on poverty and redistribution. Economia 19: 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Åslund, Olof, and Hans Grönqvistet. 2010. Family size and child outcomes: Is there really no trade-off? Labour Economics 17: 130–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 1992. Measuring Poverty and Differences in family Composition. Economica 59: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barham, Vicky, Robin Boadway, and Maurice Marchand. 1995. Education and the poverty trap. European Economic Review 39: 1257–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, Anders, Donna K. Ginther, and Marianne Sundström. 2007. Family structure and child outcomes in the USA and Sweden. Journal of Population Economics 20: 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Richard, Monica Costa Dias, Robert Joyce, and Xiaowei Xu. 2020. COVID-19 and Inequalities. Fiscal Studies 41: 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, Bruce, and Markus Jäntti. 1999. Child Poverty Across Industrialized Nations. Innocenti Occasional Papers, Economic and Social Policy Series, No. 71; Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Burtless, Gary. 1999. Effects of growing wage disparities and changing family composition on the U.S. Income distribution. European Economic Review 43: 853–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, Kristin F. 2017. Assessing the Long-Run Benefits of Transfers to Low-Income Families. Hutchins Center Working Paper, No. 26. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/wp26_butcher_transfers_final.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Cancian, Maria, and Deborah Reed. 2008. Family Structure, Childbearing, and Parental Employment: Implications for the Level and Trend in Poverty. Institute for Research on Poverty Discussion Paper No. 1346-08. Available online: https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus/pdfs/foc262d.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Cancian, Maria, and Ron Haskins. 2014. Changes in Family Composition: Implications for Income, Poverty, and Public Policy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 654: 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellari, Lorenzo, and Stephen P. Jenkins. 2002. Who Stays Poor? Who Becomes Poor? Evidence from the British Household Panel Survey. The Economic Journal 112: 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Stacey, YenChien Chen, and Jin Tan Liu. 2019. The Impact of Family Composition on Educational Achievement. Human Resources 4: 122–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollar, David, Tatjana Kleineberg, and Aart Kraay. 2016. Growth still is good for the poor. European Economic Review 81: 68–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Maire. 2015. Sole Parents in Poverty-it’s time to update the policy paradigm. Policy Quarterly 11: 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, F. H. G., P. G. Leite, and M. Ravallion. 2010. Poverty reduction without economic growth? Explaining Brazil’s poverty dynamics, 1985–2004. Journal of Development Economics 93: 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudie, A., and P. Ladd. 1999. Economic growth, poverty and inequality. Journal of International Development 11: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmarcher, T. 2019. The Effect of Education on Poverty: A European Perspective. Working Papers. Lund: Lund University, Department of Economics, Vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Iacovou, M. 2001. Family Composition and Children’s Educational Outcomes. ISER Working Paper Series, No. 2001-12; Colchester: University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER). Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ese/iserwp/2001-12.html (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Iacovou, M. 2013. Household Composition, Poverty and Hardship Across Europe. Eurostat Statistical Working Paper. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/publications/statistical-working-papers (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Iacovou, M., and A. J. Skew. 2011. Household composition across the new Europe: Where do the new Member States fit in? Demographic Research 25: 465–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejczak, A., and D. Pekasiewicz. 2020. Changes in Income Distribution for Different Family Types in Poland. International Advances in Economic Research 26: 135–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, Nanak. 1993. Poverty and economic growth with application to Côte d’Ivoire. Review of Income and Wealth 39: 121–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannaki, Eleni. 2017. The Empirical Relationship between Income Poverty and Income Inequality in Rich and Middle-income Countries. LSE Research Online Documents on Economics 86917. London: LSE. Available online: https://sticerd.lse.ac.uk/dps/case/cp/casepaper206.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- LaFave, Daniel, and Duncan Thomas. 2017. Extended families and child well-being. Journal of Development Economics 126: 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Dohoon, and Sara McLanahan. 2015. Family Structure Transitions and Child Development: Instability, Selection, and Population Heterogeneity. American Sociological Review 80: 738–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, Robert I. 1996. The impact of the Changing US Family Structure on Child Poverty and Income Inequality. Economica 63: 119–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, Ross. 2005. The impact of family structure and family change on child outcomes: A personal reading of the research literature. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand 24: 111–33. [Google Scholar]

- Meenakshi, J. V., and Ranjan Ray. 2002. Impact of household size and family composition on poverty in rural India. Journal of Policy Modeling 24: 539–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menaghan, Elizabeth G. 2009. Family Composition, Family Interaction, and Children’s Academic and Behavior Problems: Interpreting the Data. In Family-School Links. How Do They Affect Educational Outcomes? Edited by Alan Booth and Judith F. Dunn. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Monti, Maria Giovanna, Simone Pellegrino, and Achille Vernizzi. 2015. On measuring inequity in taxation among groups of income units. Review of Income and Wealth 61: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussida, Chiara, and Maria Laura Parisi. 2020. Risk of Poverty in Southern Europe. Metroeconomica 71: 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, Rense. 2020. The Situation of Single Parents in the EU, European Parliament. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- OECD. 2011. Families Are Changing. Doing Better for Families 1: 17–53. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/social/soc/doingbetterforfamilies.htm (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Penne, Tess, Tine Hufkens, Tim Goedemé, and Bérénice Storms. 2018. To What Extent Do Welfare States Compensate for the Cost of Children? A Hypothetical Household Approach to Policy Evaluations. JRC Working Papers on Taxation and Structural Reforms No 08/2018. Seville: European Commission, Joint Research Centre, JRC114168. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, Bernadette D., and Joseph Dalaker. 2002. Poverty in the United States: 2001; U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-219. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2003/demo/p60-222.html (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Saunders, Peter. 2002. The direct and indirect effects of unemployment on poverty. Australian Journal of Labour Economics 5: 507–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen, Robert, Nancy S. Landale, and Kimberly Daniels. 2007. Family transitions in young adulthood. Demography 44: 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, Abhijit. 1996. Economic reforms, employment and poverty: Trends and options. Economic and Political Weekly 31: 2459–77. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Amartya. 1976. Poverty: An ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrica 44: 219–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, James P. 2004. Poverty and the family. EconWPA, Labor and Demography. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/23746651_Poverty_and_the_Family (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Snyder, Anastasia R., Diane K. McLaughlin, and Jill Findeis. 2006. Household Composition and Poverty among Female Headed Households with Children: Differences by Race and Residence. Rural Sociology 71: 597–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Mark J. 1993. Poverty and Family Composition since 1940. In The "Underclass Debate": Views from History. Edited by Michael B. Katz. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 220–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thévenon, Olivier, Thomas Manfredi, Yajina Govind, and Ilya Klauzner. 2018. Child Poverty in the OECD: Trends, Determinants and Policies to Tackle It. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 218. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, Elizabeth, Thomas L. Hanson, and Sara S. McLanahan. 1994. Family Structure and Child Well-Being: Economic Resources vs. Parental Behaviors. Social Forces 73: 221–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Arland, and Thomas E. Fricke. 1987. Social Change and the Family: Comparative Perspectives from the West, China, and South Asia. Sociological Forum 2: 746–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zill, Nicholas. 2009. Family Change and Student Achievement. In Family-School Links. How Do They Affect Educational Outcomes? Edited by Alan Booth and Judith F. Dunn. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zinn, Maxine Baca. 1989. Family, Race and Poverty in the Eighties. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 14: 856–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | First Births | Second Births | Third or HIGHER Births | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 2018 | 1980 | 2018 | 1980 | 2018 | |

| Austria | 41.2 | 47.1 | 35.7 | 35.3 | 23.1 | 17.6 |

| Belgium | 47.9 | 42.9 | 32.9 | 34.5 | 19.2 | 22.6 |

| Bulgaria | 47.8 | 50.3 | 37.9 | 37.2 | 14.3 | 12.5 |

| Czech Republic | 42.0 | 48.0 | 39.8 | 37.2 | 18.2 | 14.7 |

| Denmark | 45.8 | 46.3 | 37.1 | 36.9 | 17.1 | 16.8 |

| Finland | 47.0 | 40.7 | 35.5 | 34.2 | 17.5 | 25.1 |

| Greece | 44.9 | 47.0 | 37.4 | 36.6 | 17.7 | 14.4 |

| Hungary | 45.5 | 46.4 | 38.8 | 32.9 | 15.6 | 20.7 |

| Iceland | 37.3 | 44.7 | 30.7 | 33.2 | 32.0 | 22.1 |

| Ireland | 29.2 | 38.4 | 24.4 | 34.8 | 46.4 | 26.8 |

| Italy | 46.7 | 46.6 | 34.3 | 38.5 | 19.0 | 15.0 |

| Latvia | 52.8 | 39.5 | 33.4 | 37.8 | 13.8 | 22.6 |

| Netherlands | 43.1 | 44.8 | 37.1 | 36.6 | 19.8 | 18.5 |

| Norway | 50.3 | 43.0 | 32.3 | 38.2 | 17.3 | 18.9 |

| Slovak Republic | 40.1 | 45.7 | 35.3 | 35.0 | 24.6 | 19.3 |

| Slovenia | 48.5 | 45.5 | 38.7 | 39.2 | 12.8 | 15.4 |

| Spain | 42.8 | 49.1 | 31.1 | 38.0 | 26.1 | 12.9 |

| average | 44.3 | 45.1 | 34.8 | 36.2 | 20.9 | 18.6 |

| HCR 2019 | HCR 2010 | VAR % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordic | Households | 17.8950 | 17.4249 | 2.70 |

| Individuals | 14.3684 | 13.8034 | 4.09 | |

| Continental | Households | 16.7240 | 16.1606 | 3.49 |

| Individuals | 13.6821 | 13.8432 | −1.16 | |

| Anglo-Saxon | Households | 19.1902 | 18.3766 | 4.43 |

| Individuals | 18.0014 | 16.7030 | 7.77 | |

| Mediterranean | Households | 19.5878 | 19.813 | −1.14 |

| Individuals | 19.6927 | 19.4195 | 1.41 | |

| Eastern | Households | 19.4161 | 17.2460 | 12.58 |

| Individuals | 16.6373 | 16.9772 | −2.00 |

| WLS (Weighted Least Squares) Dependent Variable: Head Count Ratio (the Share of Persons with an Equivalised Disposable Income below the Risk-of-Poverty Threshold, Which Is Set at 60 % of the National Median Equivalised Disposable Income (After Social Transfers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Moldel 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Per capita GDP, PPP Euro, average 2015-2019 | −8.17229e-05 (2.95157e-05) ** | −5.37576e-05 (2.03873e-05) ** | −3.60961e-05 (0.820246) *** | |||

| Social cash benefits and social in kind benefits for families (2019) | −1.93272 (0.864591) ** | |||||

| Female unemployment | 0.0465247 (0.0231323) * | 0.106260 (0.03668) *** | ||||

| INEQ | 0.727745 (0.0538034) *** | 0.648487 (0.0428954) *** | 0.637258 (0.0411488) *** | 0.665617 (0.0252386) *** | 0.770575 (0.0535229) *** | 0.742492 (0.0600072) *** |

| Share of persons with secondary education 2018 | −0.0640751 (0.0246600) ** | −0.0524619 (0.0212443) ** | −0.0696824 (0.0241048) *** | −0.0675370 (0.00890504) *** | −0.0400034 (0.0163647) ** | −0.0391403 (0.0188492) * |

| Single with dependent children | 0.479674 (0.225447) ** | 0.275074 (0.148516) * | ||||

| Extended family with children | 0.226457 (0.0458668) *** | 0.174426 (0.0765417) ** | 0.140286 (0.0557374) ** | |||

| Indicator of replacement for couples calculated as marriages minus divorces (2018) | −0.817638 (0.203494) *** | −0.730639 (0.138023) *** | ||||

| Couples without dependent children | −0.141050 (0.0724928) * | −0.177072 (0.0979028) * | ||||

| Couples with dependent children | −0.143487 (0.0337882) *** | |||||

| Crude divorce rate (2018) | 1.26908 (0.423558) *** | |||||

| Obs | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

| Uncentered R squared | 0.772148 | 0.821398 | 0.874619 | 0.95729 | 0.995021 | 0.974048 |

| Centered R squared | 0.791422 | 0.862458 | 0.995406 | 0.992045 | 0.999624 | 0.999043 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antonelli, M.A.; De Bonis, V. Economic Poverty: Does the Break-Up of Families Matter? Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060224

Antonelli MA, De Bonis V. Economic Poverty: Does the Break-Up of Families Matter? Social Sciences. 2021; 10(6):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060224

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntonelli, Maria Alessandra, and Valeria De Bonis. 2021. "Economic Poverty: Does the Break-Up of Families Matter?" Social Sciences 10, no. 6: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060224

APA StyleAntonelli, M. A., & De Bonis, V. (2021). Economic Poverty: Does the Break-Up of Families Matter? Social Sciences, 10(6), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060224