Abstract

Spanish healthcare workers’ professional identity is intricately associated with the idea of vocation, among others values. This attitude has become even more marked during the current COVID-19 pandemic—during which these professionals have endured a gruelling workload that has tested the limits of their physical and mental strength. The objective of this study is to open a debate on the symbolic dimensions of identity and culture among healthcare professionals (mainly doctors and nurses), analysing the factors that, on the one hand, might reinforce this symbolic system or, on the other, might question it or cause it to be restructured. The study follows an anthropological perspective, with the thematic content analysis of twenty-two in-depth interviews with primary healthcare professionals. The results show the need to dissect the symbolic and structural factors underpinning anxiety and fear in medical professional performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. These have a significant impact on the current model of medical practice and its most visible and worrying consequence, continuous occupational distress. The conclusions suggest that these models need to be reviewed since there is a notorious dissonance between their strengths and weaknesses.

1. Introduction

Healthcare professionals have dealt with previous episodes of pandemic in the recent past. Therefore, they are used to working in complex situations, as well as anticipating a variety of scenarios in order to improve their responsiveness in crisis situations—such as the one created by the current COVID-19 pandemic. In the Spanish context, in the past the importance of improving collaboration and coordination among different healthcare services and professionals (Álvarez Pasquín et al. 2005) has become apparent, as well as the importance of preparedness and advance planning to help decision-making in uncertain or crisis situations, during which ethical aspects should not be neglected (Arias Bohigas 2009). The experience acquired during previous, recent pandemics—such as SARS or H1N1—has helped develop preparedness plans to reinforce healthcare workers’ resilience, including improved training in emotional wellbeing (Aiello et al. 2011), as well as placing a greater emphasis on the provision of psychological support for them (Álvarez Pasquín et al. 2005). A pointed example of the plans developed to manage the psychological impact among healthcare workers is the Anticipate, Plan and Deter Responder Risk and Resilience Model (APD) (Schreiber et al. 2019), which was developed for disaster and terrorism events and was first implemented during West Africa’s Ebola epidemic.

However, we agree with Kelman’s assertion (Kelman 2020a, 2020b) that so-called “natural” disasters rarely occur. On the contrary, it is crucial to recognise that natural disasters test and expose historical patterns of vulnerability within societies—as has been the case during the current pandemic. The infrastructural and material factors underlying and driving epidemics are diverse—and are not only due to interactions among species, but also social issues (Hoffman and Oliver-Smith 2002; Le Coq 2019; Lynteris and Keck 2018; Caduff 2020). For this reason, Horton (Horton 2020) has suggested the term “syndemic” be used instead. As Revet (Revet 2020) points out, social sciences have long proved that disasters occur when a society that has been made vulnerable because of political decisions, economic choices, or forms of social organisation is struck by a phenomenon, be it natural or technological in origin. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus, has laid bare the vulnerability of health systems, including that of Spain—despite it usually being ranked as one of the best and most robust globally (Björnberg and Phang 2019). As Gellner (Gellner 2020) has suggested, it is in moments of crisis that underlying power structures and unspoken truths are revealed. Napier (Napier 2020), on the other hand, notes that a crisis can also create new, unexpected vulnerabilities by “pushing previously less vulnerable groups across capability and opportunity thresholds”—as has happened to healthcare workers during the current health emergency. Exposed to risks beyond those inherent to their regular professional practice, Spanish health professionals have expressed their opinion that they have been institutionally neglected, and have failed to receive the protection and structural reinforcements needed to cope with the ongoing pandemic. This underlines our opinion that this pandemic is not only an epidemiologic problem, but also a social, economic, and structural one. At the same time, paying attention to the healthcare workers’ collective social representations during a crisis situation is a crucial issue, since it provides an insight into their practices and mental perceptions, and how they understand and interpret the world.

Different authors (Pfeiffer and Nichter 2008; Closser and Finley 2016) have pointed out the importance of applying an anthropological (informed, socially situated) approach to global health research—using the potential of this methodology, attuned to identifying nuances in the different contexts analysed, to achieve positive changes. As social scientists, anthropologists are particularly well-suited to questioning and exploring cultural change—which sometimes can take place at an overwhelmingly rapid speed, as we are currently experiencing—and how these elicit different and creative responses among the population.

The main aim of this article is to explore the symbolic dimension of the identity and culture of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

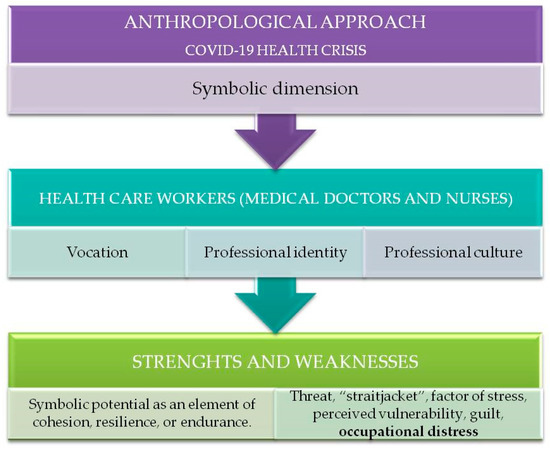

Our main purpose was to examine and analyse the elements underpinning these sociocultural constructions, both from an individual and a collective viewpoint. In so doing, we have dissected and brought to light the symbolic and structural factors behind the anxiety and fear experienced by healthcare professionals during the current pandemic (Vázquez Peñas 2019; Gómez Esteban 2004)—in particular among those working in primary healthcare settings. Hospital-based professionals’ opinions have also been considered, since these symbolic constructions have a profound effect at all levels within the current organisational model of medical practice—and its most concerning and visible consequence, occupational distress. Figure 1 describes the main focus, agents, and key concepts at the core of this article. It also includes the healthcare professionals’ most relevant strengths and weaknesses, which are essential for understanding the situation that many of them are experiencing, as well as their emotional response.

Figure 1.

Conceptual map and main concepts.

The examination of different narratives has allowed us to identify elements that might, on the one hand, reinforce those cultural constructs; and, on the other, might subject them to questioning or even reassessment of those constructs—indicating that they are active agents in terms of social and power dynamics.

Different researchers have theorised about the processes of transmission of professional identity among nurses, and their social perception (Errasti-Ibarrondo et al. 2012; Salazar and Morcillo 2013; Mena Tudela et al. 2018; Nazon et al. 2019; Franco Coffré 2020). These studies point to a dissonance between the ideal, aspirational model learnt during training and the reality experienced during daily clinical practice.

The nurses’ professional identity is created through the internalisation of an ideology—a combination of symbols and meanings encompassing beliefs, values (including moral values), attitudes, and knowledge of the discipline. This is transmitted and learnt during a process of training and socialising as a group, particularly while at university (Arreciado Marañón and Pera 2015; Merino Castillo 2017). It is also frequent in the Spanish context that part of this ideology predates professional socialisation, being passed down as part of a family tradition or within a particular social environment.

The fact that a large part of society lacks a realistic understanding of their professional profile is a constant source of frustration for nurses. Old-fashioned moral parameters remain embedded in the collective imagination. For instance, the routine association with values such as altruism or vicarious vocation denies or “invisibilises” their professional and intellectual qualities (Marañón 2013; Mena Tudela et al. 2018; Franco Coffré 2020).

This makes it necessary to reassess the concepts of “vocation” and “altruism”, since these are rooted in historical, sociological, theological, and other cultural sources (Nightingale 1969; Rapport and Maggs 2002). The relevance of such re-examination has been expressed anew as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has turned them into critical categories of analysis.

Medical doctors’ professional identity is similar to that of nurses in that among their core values are a vocation for service, a science-based approach, and a position of power immanent to their role (Peña Pentón 2014). Their cultural corpus is based on a series of highly symbolic elements such as altruism, dedication, commitment, compassion, and professional competence (Shanafelt et al. 2019). However, nowadays, these values are not exclusive and have become commingled with others, such as the social status and financial appeal or security that it provides (Perales et al. 2013). The main difference between these identities is the hierarchical relationship, still pervasive in clinical environments, between medical doctors and residents (Sinclair 1997) and between doctors and nurses with the latter in a subordinate or stigmatised position, as pointed out in a number of studies (Errasti-Ibarrondo et al. 2012; Franco Coffré 2020; Carrillo-Ávila 2017). For many years there have been voices pushing towards a shift in this ideological paradigm, leaving this alienating vision behind—a vision in which the history of the discipline itself is seen as a restrictive “straitjacket” (Franco Coffré 2020). For this change to take place, nurses must create a more robust concept of their self, enhancing their autonomy and profile. This is the goal advocated by the campaign “Nursing Now”, promoted by the World Health Organisation and the International Council of Nurses (Crisp and Iro 2018). Lunardi, Peter and Gastaldo (Lunardi et al. 2002) made an interesting suggestion regarding the existing restrictions on nurses’ agency, which they conceptualised as “power anorexia”—where stereotypes, feelings of inadequacy, and low self-esteem stifle their desire to exercise power. Since this is not a minor issue, we must take into account that nursing is predominantly a female-dominated profession (Pimentel et al. 2011).

Shanafelt et al. (2019) argue that “cultures change when there is a stimulus that upsets the equilibrium” (p. 1559). Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic is acting as a catalyst that has altered our understanding of the world in many different ways. Our study focuses on these symbolic aspects of the healthcare culture to understand the shifting views prevalent among medical doctors and nurses in the Spanish context during the most critical months of the pandemic and the subsequent easing of restrictions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study has followed a qualitative research approach using the thematic content analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006) of in-depth, semi-structured interviews (Creswell 2013). This approach helps explore the meaning attributed to the content expressed within its particular social context. Instead of a thematic content analysis based on predetermined categories, we have conducted an inductive content analysis—identifying emerging categories from the analysis of the content expressed during the interviews (Aberláez and Goñi 2016).

This methodological approach allows the description of similarities in the participants’ meanings attributed to their experience of a phenomenon (Moustakas 1994). Therefore, it is in line with the primary goal of our study—understanding the experiences of health professionals in primary healthcare and hospital settings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The interviews aimed to provide an understanding of the participants’ lives, experiences, and situations from their own point of view, and in their own words (Taylor et al. 2015; Olabuénaga 2012).

2.2. Research Team

The study was carried out by four researchers. All are experienced in qualitative designs, and all are university lecturers, and do not undertake clinical practice.

2.3. Research Background

The study was carried out in primary healthcare settings in Spain. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these services played a crucial role in the early detection of cases, contact tracing, and self-isolation of positive cases and their close contacts. They contributed to the knowledge of the evolution of the disease and the protection of those who looked after people affected (Collado Hernández and Rugarcía 2015; Almuedo-Riera and Muñoz 2020). Therefore, it is crucial to describe how the shared culture among primary healthcare workers affected their experience of the pandemic—how this cultural group worked and experienced the events from an emic viewpoint.

2.4. Participants

Participants were selected through a non-probability sampling of healthcare workers who indicated their availability in a previous online questionnaire hosted on the website of the University of Castilla-La Mancha (UCLM, Spain) using the LimeSurvey platform. The questionnaire was sent to all users of the UCLM email service and was also advertised in posters at primary healthcare settings in the region, with the knowledge and authorisation of the regional health board. Access to the questionnaire was through a QR code created for that purpose.

The online questionnaire collected general demographic data and the respondents’ professional profile, as well as information on the pandemic’s impact both at a personal and a professional level. It also invited them to participate in further structured interviews.

The study took place between 1 July and 30 October 2020. To obtain a wider variability within the participants’ accounts, the sample included professionals with different demographics (gender and age), training (university degree/master/doctorate), professional situation (zero-hours/temporary/permanent contract), and years of professional experience. Criteria for inclusion were as follows: (a) Healthcare professionals; (b) Working in a primary healthcare setting when the study started; (c) At least one year of work experience in primary healthcare; (d) Able to communicate clearly; and (e) Having completed the online questionnaire (corresponding to the first stage of the study). All participants had to comply with the criteria for inclusion defined above.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Fieldwork and data collection were based on in-depth interviews (Kvale and Brinkmann 2015; Denzin and Lincoln 2012) guided by a series of semi-structured questions—subject to the participants’ prior informed consent. The interviews were conceived as a starting point to explore several themes that emerged from the data collected from the first-stage questionnaire, enabling us to refine the questions asked in subsequent interviews as the research process progressed.

The interviews were carried out by three members of the research team, experienced in qualitative methodology, following a standard protocol that included the data collection method and a series of guided questions. Interviews were undertaken in a place previously agreed-upon with the participants—neutral, comfortable, quiet, and guarantying privacy and confidentiality.

The interviews gathered information on the experiences of primary healthcare professionals (medical doctors and nurses) during the period of lockdown and the subsequent easing of restrictions in the health board area of Talavera de la Reina (Autonomous Community of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain). To obtain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon studied and for feasibility reasons due to the epidemiologic situation, a convenience sampling was used to select different healthcare professionals working during the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 22 in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted (Table 1), the participants being selected from the larger simple of 252 healthcare professionals who completed the questionnaire (data from the questionnaires is not included in this article).

Table 1.

Participants’ profiles.

Researchers contacted the participants and their healthcare setting coordinators to facilitate access to the study’s social and cultural context (Carpenter and Suto 2008). They also explained the aims and design of the interviews. All interviews were recorded (Table 1). The recruitment of new participants stopped when the information gathered from the interviews started to produce repeated results—when the participants were not providing any new analytic concepts, repeating information and confirming data already noted (Carpenter and Suto 2008).

Qualitative data analysis was based on the principles of the constant comparison method (Carrera 2014) and the coding process (Gómez 2016). Each interview was transcribed in full and verbatim, as were the researchers’ observations and field notes. Transcripts were collated for qualitative analysis (Taylor et al. 2015; Miles et al. 2014; Zarco et al. 2019). Data analysis was triangulated across four members of the researcher team, all of whom had experience in qualitative methodology. Each researcher independently analysed the data, comparing the results, analysing divergences and coincidences, and finally discussing the results as a group—agreeing on codes, categories, subcategories, and emerging themes. Contrasting different viewpoints on the same study subject enhances data quality and validity and minimises research bias (Aguilar Gavira and Osuna 2015).

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethical Committee of the Talavera de la Reina Integrated Management Area (CEIm del AGI de Talavera de la Reina in Spain, Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado, ref: 23/2020). Participants’ personal data were anonymised in line with current data protection laws (Jefatura del Estado 2018). The research followed the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. Collected data were treated in accordance with the guidelines on the ethical implications of research, and were used with the utmost confidentiality and remain protected under Law 15/1999, of 13 December, on Protection of Personal Data (Jefatura del Estado 1999).

Only members of the research team had access to the data gathered through the online questionnaire, and the UCLM guaranteed the security of their server.

3. Results

Three main themes emerged from the analysis of the interviews regarding the personal and professional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare professionals: (1) The symbolic role of vocation and work-pride among healthcare professionals; (2) Primary healthcare remains subordinate to hospital-based medical care; and (3) Occupational distress and self-neglect.

3.1. The Symbolic Role of Vocation and Work-Pride among Healthcare Professionals

Participants repeatedly mentioned their professional vocation as a highly significant symbolic artefact, which enabled their attitude and behaviour regarding the excessive workload endured during the most critical period of the pandemic—even when this had detrimental consequences on themselves.

The interviews shed light on those most subjective aspects of an individual’s perception of their own role, and reflected an emotionally charged rhetoric, based on values of humanism and empathy, that drives them to strive to help others.

[...] without this drive to work, drive to do it and do it right, and getting involved, and really, really getting to know the inside of the families, and knowing... I do not conceive working if you are not really passionate; for me it is all about passion. I am very passionate [...] it is my vocation.(N5)

Most of the accounts analysed expressed the kind of empathy/altruism that cause a person to act through a personal identification, either with their own self or with those of their kin.

To me, this vocation is to put yourself in the place of others, I really enjoy listening to them. And well, for me that is part of being a nurse, listening, putting yourself in the patient’s place...(N3)

However, we have also observed attitudes in which altruism can be considered induced—with the donors’ actions not taking place in a context of balance and reciprocity, and sometimes being indeed detrimental, since other people’s needs are prioritised over their own.

[…] this feeling is what makes you enjoy your work. And, despite the problems, the hardships, and the poor work conditions, at the end of the day you are satisfied with what you are doing. And, although we had to give it our all—because it is true, we had to stay late or—always checking our mobiles, talking to—I’ve had to talk to people even on weekends […](N8)

The key symbolic element underpinning the professionals’ resilience lies in a very intimate sphere and is reinforced through an instilled submissiveness to the authorities in charge.

For me, vocation is something that you want, that makes you happy, that makes you feel good when you do it, that makes you happy at the end of the day, and also makes you a better person. I do not think there can be a medical doctor without vocation, otherwise you could not take this, without vocation nobody could endure it—you would take sick leave, you would go away or something like that—but you would not endure it, you would not stay...(M13)

Likewise, their professional identity acts as an element of collective cohesion, creating the category of “healthcare work-pride”—which, in turn, reinforces the classic symbolic qualities of vocation.

I feel proud of being a nurse, not because of the COVID and all the clapping, but because I strive every day to do my best at work—although sometimes you need your efforts to be recognised, yes, of course, we all like to see that our work is appreciated and sometimes being told “Hey, look, you are doing great”, we all like that. Not that we need to be told every day, because what we do, we do because we want to, and because it comes from within.(N2)

3.2. Primary Healthcare Remains Subordinate to Hospital-Based Medical Care

Some of the primary healthcare professionals interviewed did not see themselves as heroes—saving this role for those working in hospitals, emergency services, or intensive care units. This stigmatised vision of their own self-worth must be assessed in the context of healthcare professionals’ collective imagination, acquired and internalised during their training but also through their life experiences, their family, and their social and cultural background. The fact that primary healthcare professionals do not see themselves as heroes, but they think the “other”, hospital-based workers are, is a telling indicator of a general lack of appreciation for the primary level of healthcare. Some of our participants had, in fact, been working in intensive care, either as volunteers or having been posted there, as they understood it was a priority.

...we need to promote primary healthcare a bit; I think the service is not just about measuring blood pressure again and again, mechanically; my appreciation is that the image of primary healthcare is, well, very different from that of hospitals, at a managerial level and so, but also for the users and the professionals; I would even say it has been forgotten a bit, left behind... They have not been taken into account.(N3)

The speed at which events have been taking place, the “pandemic fatigue” among the population, and the effects of the virus’ second wave have left primary healthcare services struggling to cope and led to a resurgence of problems such as conflicts between patients and healthcare workers (Abad González et al. 2008). Those same professionals being praised in March as “heroes”, (N1, 1/07/2020; N5, 3/08/2020; N12, 10/09/2020), were only a few months later the target of criticism, insults, and attacks (N12, 10/09/2020; N17, 15 October 2020). The main reason for this shift in perception was the implementation of remote consultations—telemedicine—in response to new medical guidelines for medical assistance—with phone or video calls instead of face-to-face appointments—which many patients perceived as a dereliction of duty.

In the 1980s, Spain started developing family and community healthcare services following the guidelines and new healthcare models agreed in 1978 in the Alma Ata Conference (Gómez Esteban 2004). Since then, there have been many achievements, but the overburdening of primary healthcare has never been alleviated. In the long term, specific problems affecting professionals working in the busier settings remained unchanged or even worsened—these include struggles to cope with their workload, unsatisfactory doctor/patient relationships, and lack of social support. The praise and clapping at the start of the pandemic were soon seen as an illusion that, after the initial shock, elicited instead attitudes of resistance—being perceived as ephemeral, unrelated to their efforts.

That the clapping would soon turn to stoning is something we all knew. All healthcare workers knew, and we did say, “Listen, no, we do not want this.” Perhaps the first time it was moving, but afterwards it turned into a carnival—the time of the day everyone went out into their balconies to have a good time. But as soon as this is finished, we are going to be abused. In particular, primary healthcare workers. Those working in hospitals have been respected.(M11)

3.3. Occupational Distress and Self-Neglect

One of the clearest signs of occupational stress is the workers’ inability to switch off at the end of the day, something that some participants justified as “it shows we care” but is in fact a clear symptom of burnout syndrome. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a source of daily stress and suffering for many workers, healthcare professionals included. However, healthcare workers as a collective have been twice as vulnerable, since their sense of self-sacrifice and responsibility has often made them neglect their own care, while also invisibilising their suffering.

I have been coming to work almost every day of the week, just to see how things were... Even if it was not my shift, I was giving my 200% even on my days off. It was, I don’t know, like a need—I felt like coming in to give a hand; many of us have been doing this...(N2)

The participants in our study mentioned repeatedly their difficulties to establish a clear separation between their profesional and personal lives during the first months of the pandemic. This appears to be a recurring, intersubjective strategy:

They are still in my head—I think about the patients I have seen, their circumstances, and I keep brooding, thinking whether I could have done something better.(N2)

This failure to detach themselves from their work was a cause of constant suffering, which manifested itself in a variety of ways, such as insomnia—a physical expression of the constant tension between two conflicting emotions, exhaustion and the fulfillment they find in their work:

[…] You asked before whether we could switch off from work, and I will tell you—around 60% of the time we cannot, perhaps 40% of the time we can, but many, many times—I tell you, never in my life I’ve had to take pills like I do now, because the stress at work was too much to bear, and lately if it wasn’t for the pills I would not have been able to sleep—and we need our rest so much!(N19)

4. Discussion

Crises and other emergency situations, such as that caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, underline the role of vocation as a pillar, but also a distorting factor, of the healthcare workers’ professional identity. This identity is assimilated both as part of the cultural baggage defined by the collective imagination and during their professional training—where it is institutionally constructed and internalised as part of their professional culture.

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised healthcare professionals’ profile and their work during the most critical stages of the crisis and afterwards, and they have been the subject of different social representations. Social and political events have determined this process. The shift in social perceptions during the lockdown—shaped, in turn, by medial channels, stereotypes, and the situation of crisis—turned healthcare workers into heroes, who were responsible for “our health and our freedom”. Their heroification stems largely from society’s trust of the healthcare system and professionals, with their wellbeing. At the same time, the crisis laid bare the vulnerabilities of the healthcare system, confirming negative forecasts about its sustainability that were noted years ago (Bernal-Delgado and Ortún-Rubio 2010).

Canals (Canals 2020) suggests that the social appetite for “heroes” is a new form of Sahlins’ concept of mytho-praxis—a mechanism through which societies dealing with unexpected situations create narratives that include previous mythological models and heroic figures to make sense of their uncertainty. At the same time, it is important to bear in mind that the popular perception of healthcare in Spain is often hospital-centred (Comelles 2020). As noted by some of our participants, during this pandemic it was “the others” [hospital-based professionals] who were seen as heroes—primary healthcare workers, despite their continued effort, were constantly undervalued.

The analysis of the subjective perceptions of the healthcare workers interviewed has hightlighted an alternative dimension of empathy—morals—that is intricately associated with their professional culture and might explain why altruism is such a strong motivation for their actions (Badcock [1946] 1986; Perales et al. 2013; Vázquez Peñas 2019; Ayuso-Murillo et al. 2020). Talego Vázquez (2014, p. 192) equates this attitude with a form of asceticism in which “every single act in their life is turned into an offering to their sacred nature, although driven by an intimate and loving enthusiasm […] that turns him into a virtuoso, ahead of his time, a hero...”. He also suggests that vocation, like asceticism, is an attitude involving selflessness and enthusiastic abnegation—and both are inextricably related to religious practice. However, the religious aspects of the profession were eliminated from the Spanish healthcare system many years ago. Nowadays, if these attitudes survive, they do not follow a discourse or logic—their motivation is purely affective. Still, this attitude reflects the survival of some enduring, traditional values, despite our historic and cultural evolution.

At the same time, it is important to recognise that heroism is one of the values on which the classic symbolic framework of the medical identity is grounded—a vocation of service to others; a call to surrender your personal desires to a greater goal, the patient’s welfare, as Wheeler (Wheeler 1990) argued. In situations of crisis such as pandemics, this dedication is sometimes taken to extreme lengths, leading to deaths among healthcare professionals, as Peña (Peña Pentón 2014) has noted. Sadly, this has been the case in Spain, where more than 63 healthcare workers have died since the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Indeed, seven of the first ten deceased were primary healthcare workers (Castro 2020). The deaths that took place in rural, primary healthcare settings might explain the dynamics underpinning behaviours that could otherwise be seen as “extreme”. According to Batson and Shaw (1991), instances of pure altruism are rare and generally associated with small or kinship groups—which might perhaps justify the attitude of self-sacrifice among healthcare professionals, grounded in their symbolic position as family doctors, and taken to the final consequences. For them, this position is meaningful and more than a label. This could also be related to what Frayne has defined as the “moral imperative” to work as a cause of occupational distress (Frayne 2017).

This heroification, based upon the support of both society (clapping) and media, is also intrinsically linked to a militarised political discourse—a rhetoric that, by describing healthcare professionals as working “on the frontline”, establishes a direct relation between medical practice and war/militarism (Varma 2020). This rhetoric also underlines the main vulnerability to which healthcare workers (both doctors and nurses) have been exposed—namely, the acceptance of extreme working conditions. During the first wave of the pandemic, there was a lack of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), human resources, and efficient work organisation models.

Most healthcare workers rejected from the start their categorisation as “heroes”, arguing that they were just doing their job, which was their “vocation”. Media channels and social media, i.e., Twitter, responded to the gaps and vulnerabilities in their working conditions by creating the analogy of healthcare workers as “martyrs”. Many headlines and tweets exhibited and made viral images of the lesions caused by wearing masks and PPE for hours on end, describing them as badges of honour or sacrificial marks (Scully 2020).

General practices, the flagship of primary healthcare and the first port of access for much of the population, remained partially closed—with the implementation of telemedicine and remote consultations following new guidelines. A sector of society felt those closed doors and lack of face-to-face appointments was disloyal, a dereliction of duty—particularly as it came after months of lockdown in which access to primary healthcare services was limited. This created a shift in public opinion, with healthcare workers turning into villains that were sometimes abused and even attacked (Zuil 2020), with shouts of “I pay your wages, this is not fair”. The loyal, selfless soldier was now a deserter. This shift laid bare the vulnerabilities of the Spanish healthcare system, which pre-date the COVID-19 pandemic—such as the fragile healthcare worker/patient relationships within a strained system with deep structural weaknesses, among other sociocultural factors that have contributed to de-sacralise their relations (Abad González et al. 2008). At the same time, this crisis has revealed the healthcare professionals’ discontent with strategies of concealment of a reality characterised by deep structural weaknesses, and where their “subjective levers” have been tested to the limit in order to gain their acquiescence (Vázquez Peñas 2019).

The verbal accounts collated during this study reveal weaknesses in the working conditions and work organisation models. Despite this, healthcare workers blamed themselves for their limitations, their perception mediated by their internalised professional identity as a subjective restraint. At the same time, they described a variety of experiences of distress and fear. Dejours (2009a) argues that these feelings are the result of an intersubjective consciousness associated with roles learnt and internalised, which cause guilt among the professionals—even while these workers are aware that their vulnerability is structurally induced. Their “experience of fear” is a symbolic mechanism that turns mental stress into a moral duty. Healthcare professionals fear for themselves, for their patients, for their close relatives, and for having to return to work every day in inadequate, unacceptable conditions. As Madrid has suggested (Madrid 2010), this is a relational distress, based on their perceived vulnerability due to a lack of protective equipment amid a pandemic, the knowledge that they could infect their loved ones when they return home, and their role as the only supporters of those patients in extremely severe conditions, who are sometimes facing a lonely death.

These symbolic constructions, reinforced by media and politicians, mask, trivialise, and normalise relations of dominance and social injustice at work (Vázquez Peñas 2019; Evangelidou et al. 2020). Doctors and nurses work in a healthcare system whose structural fragilities and vulnerabilities have been brutally exposed (Caduff 2020). According to Antonio Madrid (Madrid 2010) we must bear in mind that work organisation models do not only act as obligations imposed by others; instead, they mediate through processes of subjectivisation that suggest to individuals their own courses of action, acting as power mechanisms. Thus, healthcare workers normalise their distress, assuming that “it is what they have to do”, what is expected of them. To cope with their pain, they resort to what Buytendijk called “passive heroism” (Madrid 2010) in the name of a higher interest—a sacrifice suited to the context of a pandemic which media and politicians have equated with a war.

Another element at play is the so-called ideology of shame (Dejours 2009a, 2009b)—healthcare workers assume they have to cope with their distress for the sake of their colleagues and patients, ignoring their own wellbeing (Acuña and Sanfuentes 2018). Ambivalent feelings of fear and anxiety on the one hand, and increased feeling of responsibility and empathy towards others on the other, are frequent – as also has been noted in other contexts (Johnson et al. 2020).

Despite all the negative aspects to this study’s results, it has also brought to light some kinder, more hopeful notes. As Llorens García (2020) also notes, the current crisis has activated the resilience as a collective of healthcare workers, re-establishing social synapses that had become dormant. However, it is important to understand that their occupational ill treatment predates the COVID-19 crisis. To give only one example, hospital nurses can work with contracts for a day, a third of a shift, or a month; and since they can be sent to a different setting every day, they are unable to familiarise themselves with their working environment or to establish meaningful relationships with their patients.

5. Conclusions

Our study aimed to explore the symbolic aspects underpinning Spanish healthcare workers’ identity and culture and how these affected their attitudes, behaviour, and experiences during the most critical months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The thematic content analysis and phenomenological approach suggested that the role played by their professional identity was ambivalent.

Among the professionals interviewed, there were significant mentions and references to their vocation. During the pandemic, society and media played a decisive role in the reinforcement of this classic stereotype. Vocation is considered a fundamental aspect of medical doctors’ and nurses’ resilience, together with feelings such as an awareness and sense of pride in their work, the feelings of cohesion and solidarity within teams, and the reinforcement of intragroup synapses and equity.

On the other hand, their vocation is also used to mask and symbolically legitimise their tolerance of occupational distress—which is accepted as part of a role that has been learnt and internalised. These attitudes, however, are increasingly questioned and contested. Indeed, many of the study participants highlighted the structural weaknesses of their work conditions and organisational models.

In light of the themes that have emerged in this study, it is possible to suggest that the process of socialisation and enculturation within healthcare disciplines must, in the Spanish context, follow a more balanced approach to the discourse on vocation and identity—so that it is not used to promote and normalise distress in their working environments. It is also necessary to reinforce the problems of understaffing and underresourcing in primary healthcare services, together with their social perception. Finally, it is relevant to emphasise the importance of balancing the current medical organisational model, which prioritises large hospitals over family and community healthcare settings—whether this is within the context of a pandemic or less difficult times.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, and formal analysis, L.A.G., M.P.-F., J.A.F.-M., C.C.-C.; investigation, L.A.G., M.P.-F., J.A.F.-M., C.C.-C.; resources, L.A.G., M.P.-F., J.A.F.-M., C.C.-C.; writing – original draft preparation, L.A.G.; writing – review and editing, L.A.G., M.P.-F., J.A.F.-M., C.C.-C.; visualisation, L.A.G., M.P.-F., J.A.F.-M., C.C.-C.; supervision, validation L.A.G., M.P.-F., J.A.F.-M., C.C.-C.; project administration, L.A.G., M.P.-F.; funding acquisition, L.A.G., M.P.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication has been co-financed by the University of Castilla la Mancha and the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) and Group Research Grants. The authors belong to the Group of Ethnography and Applied Social Studies (GEESA).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Funding bodies had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Abad González, Luisa, Margarita Garrido Abejar, Rosa Fuentes Chacón, and Inmaculada García. 2008. Etnografía de Los Centros Sanitarios En La Provincia de Cuenca. Análisis Del Continuum Confianza-Conflicto. In Etnografías en Castilla la Mancha: Adhesiones y Transformación. Juan Antonio Flores Martos (Coord.). Toledo: Almud Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Aberláez Gómez, Marta, and Javier Onrubia Goñi. 2016. Análisis bibliométrico y de contenido. Dos metodologías complementarias para el análisis de la revista colombiana Educación y Cultura. Revista de Investigaciones UCM 14: 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña Aguirre, Enrique, and Matías Sanfuentes. 2018. Institutional Abuse: Caught between Professional Vocation and System’s Efficiency. In The Reflective Citizen Organizational and Social Dynamics. London: Routledge, pp. 111–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar Gavira, Sonia, and Julio Manuel Barroso Osuna. 2015. La triangulación de datos como estrategia en investigación educativa. Píxel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación 47: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, Andria, Young Khayeri, Michelle Raja, Shreyshre Peladeau, Nathalie Romano, Donna Leszcz, Molyn Maunder, Robert Rose, Marci Adam, Mary Anne, and et al. 2011. Resilience Training for Hospital Workers in Anticipation of an Influenza Pandemic. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 31: 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuedo-Riera, Alejandro, and José Muñoz. 2020. Los Próximos Meses de La Epidemia de COVID-19. Enfermedades Emergentes 19: 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez Pasquín, M.J., M.A. Mayer Pujadas, and C. Llor Vilá. 2005. ¿Qué Papel Desempeña La Atención Primaria En El Abordaje y El Control de Nuevas Enfermedades? Gripe Aviar, Síndrome Respiratorio Agudo Grave, Bioterrorismo y Otras. Atencion Primaria 35: 204–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arias Bohigas, Pedro. 2009. La Ética Durante Las Crisis Sanitarias: A Propósito de La Pandemia Por El Virus H1N1. Revista Española de Salud Pública 83: 489–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arreciado Marañón, Antonia, and Ma Pilar Isla Pera. 2015. Theory and Practice in the Construction of Professional Identity in Nursing Students: A Qualitative Study. Nurse Education Today 35: 859–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso-Murillo, Diego, Ana Colomer-Sánchez, Carlos Romero Santiago-Magdalena, Alejandro Lendínez-Mesa, Elvira Benítez De Gracia, Antonio López-Peláez, and Iván Herrera-Peco. 2020. Effect of Anxiety on Empathy: An Observational Study Among Nurses. Healthcare 8: 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, Christopher R. 1986. The Problem of Altruism: Freudian-Darwinian Solutions. New York: Basil Blackwell. First published 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, Daniel, and Laura Shaw. 1991. Encouraging Words Concerning the Evidence for Altruism. Psychological Inquiry 2: 159–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Delgado, Enrique, and Vicente Ortún-Rubio. 2010. La Calidad Del Sistema Nacional de Salud: Base de Su Deseabilidad y Sostenibilidad. Gaceta Sanitaria 24: 254–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnberg, Arne, and Ann Yung Phang. 2019. Measuring Universal Health Coverage Based on an Index of Effective Coverage of Health Services in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caduff, Carlo. 2020. What Went Wrong: Corona and the World after the Full Stop. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canals, Roger. 2020. Dealing with the Unexpected: New Forms of Mytho-praxis in the Age of COVID-19. Social Anthropology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, Christine M., and M. Suto. 2008. Qualitative Research for Occupational and Physical Therapists: A Practical Guide. New York: Wiley. Available online: https://pureportal.coventry.ac.uk/en/publications/qualitative-research-for-occupational-and-physical-therapists-a-p-2 (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Carrera, Rafael M. Hernández. 2014. La investigación cualitativa a través de entrevistas: Su análisis mediante la teoría fundamentada. Cuestiones Pedagógicas. Revista de Ciencias de la Educación 23: 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Ávila, Eva-María. 2017. Relación Médico/a-enfermera/o en el Área Quirúrgica: Un Estudio Cualitativo. June. Available online: http://tauja.ujaen.es/jspui/handle/10953.1/6190 (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Castro, C. 2020. Siete de los 10 primeros médicos fallecidos por COVID-19 eran de Atención Primaria. El Independiente. June 2. Available online: https://www.elindependiente.com/vida-sana/salud/2020/06/03/siete-de-los-10-primeros-medicos-fallecidos-por-covid-19-eran-de-atencion-primaria/ (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Closser, Svea, and Erin P. Finley. 2016. A New Reflexivity: Why Anthropology Matters in Contemporary Health Research and Practice, and How to Make It Matter More. American Anthropologist 118: 385–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado Hernández, Belén, and Yolanda Torre Rugarcía. 2015. Actitudes Hacia La Prevención de Riesgos Laborales En Profesionales Sanitarios En Situaciones de Alerta Epidemiológica. Medicina y Seguridad Del Trabajo 61: 233–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Comelles, Josep M. 2020. Resistir. In En Reset. Reflexiones Antropológicas Ante La Pandemia de Covid-19. Tarragona: Publicacions de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, Nigel, and Elizabeth Iro. 2018. Nursing Now Campaign: Raising the Status of Nurses. The Lancet 391: 920–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejours, Christophe. 2009a. El Desgaste Mental en el Trabajo. Madrid: Modus Laborandis. [Google Scholar]

- Dejours, Christophe. 2009b. Trabajo y Sufrimiento. Madrid: Modus Laborandis. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 2012. El Campo de la Investigación Cualitativa: Manual de Investigación Cualitativa. Madrid: Editorial GEDISA, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- del Estado, Jefatura. 1999. Ley Orgánica 15/1999, de 13 de Diciembre, de Protección de Datos de Carácter Personal. Boletin Oficial del Estado. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-1999-23750 (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- del Estado, Jefatura. 2018. Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de Diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y Garantía de Los Derechos Digitales. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2018-16673 (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Errasti-Ibarrondo, B., M. Arantzamendi-Solabarrieta, and N. Canga-Armayor. 2012. La Imagen Social de La Enfermería: Una Profesión a Conocer. Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra 35: 269–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Evangelidou, Stella, Ángel Martínez-Hernáez, Vicente Rabanaque, Teresa Moreno Rubio, and María y Rabanaque Mallén Gloria. 2020. Ni Todo Es Covid-19 Ni Toda La Autopercepción Sanitaria Es Heróica. In Reset. Reflexiones Antropológicas Ante la Pandemia de Covid-19. Tarragona: Publicacions de la Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Franco Coffré, Anabel. 2020. Percepción social de la profesión de enfermería. Enfermería Actual de Costa Rica 38: 272–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayne, David. 2017. El Rechazo del Trabajo: Teoría y Práctica de la Resistencia al Trabajo. Madrid: Ediciones AKAL. [Google Scholar]

- Gellner, David N. 2020. The Nation-state, Class, Digital Divides and Social Anthropology. Social Anthropology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Esteban, Rosa. 2004. El Estrés Laboral Del Médico: Burnout y Trabajo En Equipo. Revista de la Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría 90: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Paula Andrea Urbano. 2016. Análisis de datos cualitativos. Fedumar Pedagogí-a y Educación 3. Available online: http://editorial.umariana.edu.co/revistas/index.php/fedumar/article/view/1122 (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Hoffman, Susanna M., and Anthony Oliver-Smith, eds. 2002. Catastrophe & Culture: The Anthropology of Disaster, 1st ed. School of American Research Advanced Seminar Series; Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, Richard. 2020. Offline: COVID-19 Is Not a Pandemic. The Lancet 396: 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, María Cecilia, Lorena Saletti-Cuesta, Natalia Tumas, María Cecilia Johnson, Lorena Saletti-Cuesta, and Natalia Tumas. 2020. Emotions, Concerns and Reflections Regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic in Argentina. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 25: 2447–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, Ilan. 2020a. Disaster by Choice: How Our Actions Turn Natural Hazards into Catastrophes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, Ilan. 2020b. COVID-19: What Is the Disaster? Social Anthropology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2015. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Le Coq, Rubis. 2019. Ann H. Kelly, Frédéric Keck, Christos Lynteris (dir.), The Anthropology of epidemics. Lectures. November. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/lectures/39030 (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Llorens García, Albert. 2020. Aportación Etnográfica a La Crisis Sanitaria de La Covid-19. In Reset. Reflexiones Antropológicas Ante La Pandemia de Covid-19. Tarragona: Publicacions Universitat Rovira i Virgili, pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lunardi, Valeria Lerch, Elizabeth Peter, and Denise Gastaldo. 2002. Are Submissive Nurses Ethical?: Reflecting on Power Anorexia. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 55: 183–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynteris, Christos, and Frédéric Keck. 2018. Zoonosis. Medicine Anthropology Theory 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, Antonio. 2010. La Política y la Justicia del Sufrimiento. Madrid: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Marañón, Antonia Arreciado. 2013. Identidad Profesional Enfermera: Construcción y Desarrollo en los Estudiantes Durante su Formación Universitaria. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=83331 (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Mena Tudela, Desirée, Víctor Manuel González Chordá, Desirée Mena Tudela, and Víctor Manuel González Chordá. 2018. Imagen Social de La Enfermería, ¿estamos Donde Queremos? Index de Enfermería 27: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Merino Castillo, José. 2017. La Práctica Profesional En Estudiantes Del Grado En Enfermería En Murcia. Saberes, Poderes y Subjetividades Desde Un Modelo Integrador. Murcia: Universidad Católica Murcia. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Matthew, A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, Clark. 1994. Phenomenological Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, A. David. 2020. Rethinking Vulnerability through Covid-19. Anthropology Today 36: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazon, Evy, Amelie Peron, and Thomas Foth. 2019. Rethinking the Social Role of Nursing through the Work of Donzelot and Foucault. Witness: The Canadian Journal of Critical Nursing Discourse 1: 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, Florence. 1969. Notes on Nursing. New York: Dover. [Google Scholar]

- Olabuénaga, José Ignacio Ruiz. 2012. Metodología de la Investigación Cualitativa. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Pentón, Damodar. 2014. El arte de la medicina: ética, vocación y poder. Panorama Cuba y Salud 9: 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Perales, Alberto, Alfonso Mendoza, and Elard Sánchez. 2013. Vocación Médica: Necesidad de Su Estudio Científico. Anales de la Facultad de Medicina 74: 133–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, James, and Mark Nichter. 2008. What Can Critical Medical Anthropology Contribute to Global Health? A Health Systems Perspective. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 22: 410–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, Maria Helena, Fernando Augusto Pereira, and Maria Augusta Pereira da Mata. 2011. La construcción de la identidad social y profesional de una profesión femenina: Enfermería. Prisma Social: Revista de Investigación Social 7: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Rapport, F. L., and C. J. Maggs. 2002. Titmuss and the Gift Relationship: Altruism Revisited. Journal of Advanced Nursing 40: 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revet, Sandrine. 2020. ¿Puede la crisis de Covid-19 considerarse un desastre natural?¿. Actualité. April 27. Available online: http://sciencespo.fr/ceri/fr/content/puede-la-crisis-de-covid-19-considerarse-un-desastre-natural (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Salazar, Serafín Fernández, and Antonio Jesús Ramos Morcillo. 2013. Comunicación, imagen social y visibilidad de los Cuidados de Enfermería. Revista ene de Enfermería. 7. Available online: http://ene-enfermeria.org/ojs/index.php/ENE/article/view/256 (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Schreiber, Merritt, David S. Cates, Stephen Formanski, and Michael King. 2019. Maximizing the Resilience of Healthcare Workers in Multi-Hazard Events: Lessons from the 2014-2015 Ebola Response in Africa. Military Medicine 184 Suppl. 1: 114–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, Emmer. 2020. Medics Show the Plasters and Bandages They Wear to Protect Themselves from Injuries Caused by Ill-Fitting Coronavirus Masks as They Save Lives in South Korea. March 13. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8108215/Nurses-bruises-marks-suffered-wearing-coronavirus-masks-South-Korea.html (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Shanafelt, Tait D., Edgar Schein, Lloyd B. Minor, Mickey Trockel, Peter Schein, and Darrell Kirch. 2019. Healing the Professional Culture of Medicine. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 94: 1556–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, Simon. 1997. Making Doctors: An Institutional Apprenticeship. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Talego Vázquez, F. 2014. Introducción a La Antropología de Las Formas de Dominación. Sevilla: Aconcagua Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Marjorie DeVault. 2015. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, Saiba. 2020. A Pandemic Is Not a War: COVID-19 Urgent Anthropological Reflections. Social Anthropology 28: 376–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Peñas, Aaron. 2019. Trabajo, sufrimiento e ideología en la sociedad neoliberal. OXÍMORA Revista Internacional de Ética y Política 15: 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, Brownell H. 1990. Shattuck Lecture—Healing and Heroism. The New England Journal of Medicine 322: 1540–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarco, Juan, Ramasco Gutiérrez Milagros, Milagros Pedraz, and Ana Palmar. 2019. Investigación Cualitativa en Salud. Madrid: CIS. [Google Scholar]

- Zuil, María. 2020. De Los Aplausos a Los Insultos: Aumentan Las Agresiones a Sanitarios En La Segunda Ola. October 4. Available online: https://www.elconfidencial.com/amp/espana/2020-10-04/pandemia-agresiones-sanitarios-aumentan-segunda-ola_2773220/?utm_source=upday&utm_medium=referral (accessed on 25 November 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).