Abstract

This paper addresses the question of how service delivery (SD) affects state legitimacy (SL) and conflict (C) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, drawing particularly on frameworks that move beyond a state-centric approach. Focusing on the majority-Arab countries of MENA, the paper aims to: (1) offer a preliminary explanation of the distinctiveness of this region in light of some of the main findings of the introductory paper by the lead guest editor Timo Kivimäki and (2) explore the potential of a social policy perspective in explaining the relationship between SD, SL and C. This is achieved by combining research insights acquired through extensive qualitative social policy research in the MENA region with a re-reading of the existing literature on SD, SL and C. To support a comprehensive re-examination of the issues at hand, the paper also draws on the 5th Wave of the Arab Barometer micro-level survey (ABS) on Arab citizen perceptions of socio-economic conditions in their countries and macro-level social welfare expenditure data from the World Bank World Development Indicators (WDI). By bringing insights from the social policy literature on the MENA region into conversation with broader research on the relationship between SD, SL and C, we identify several distinctive features of service delivery in the MENA context and examine their implications for state legitimacy and conflict.

1. Introduction

Research on state legitimacy and conflict has become increasingly focused on the role of service delivery. At the same time, global and national peace-building strategies have paid growing attention to the importance of service delivery as a key “arena of conflict” (Baird 2010; World Bank 2018, p. 25). Policy experts and academic observers now recognise the intrinsic connection between a lack of access to social protection services and societal grievances that may undermine state legitimacy or even contribute to violent conflict. This is exemplified in countries experiencing conflict such as Syria, Yemen, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Colombia (Baird 2010; World Bank 2018). Although recent literature has shown that the relationship between service delivery and armed conflict is non-linear (Mcloughlin 2015), there is convincing evidence that service delivery does shape state legitimacy and authority because of the key role that citizen perceptions of fairness, accountability and rule of law in services such as education, health, sanitation and even jobs can play in political stability (Brinkerhoff et al. 2012; Stel and Ndayiragije 2014). As such, service delivery is considered a marker of “risk” (World Bank 2018, p. 25) to conflict because it reflects a wider process of political inclusion and wealth redistribution in society.

Kivimaki’s (2021) starting point in the introductory article to the Special Issue is that the relationship between political legitimacy, grievances and armed conflict seems different in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region compared with other world regions.1 He hypothesises that this link is different in the MENA region due to a range of factors including: (1) the region’s dependence on oil, (2) the relative importance of external intervention in the region, (3) the disproportionate role of “political factionalism” in the explanation of conflict grievance and violence in the MENA region2 and (4) the link between the fragility of human development and conflict is weaker in MENA than in other regions. Our paper engages with these issues by exploring the underlying social and political mechanisms in MENA that may explain these links. In so doing, we first contextualise State Legitimacy (SL), Service Delivery (SD) and Conflict (C) in a discussion of MENA states; and second we then bring to bear data on the social policy context of these states to better situate the role of public services and service delivery. This allows for a deeper level discussion of the connections between state legitimacy, public services and conflict. This paper brings together insights from the social policy literature to present a re-reading of existing debates around the relationship between service delivery, state legitimacy and conflict. The purpose of the paper is to reexamine the state of knowledge in a new light in order to identify pertinent lines of enquiry for the study of C, SD and SL in MENA.

Service delivery is understood in this paper as a concept at the heart of social policy and reflects the wider political organisation of a society in terms of how citizens access key services and participation in decision-making. Effective service delivery has historically been viewed as an important tool for building citizen trust in government and in turn enhancing state legitimacy (Brinkerhoff et al. 2012; Van de Walle and Scott 2011). Although the idea of a “virtuous circle”—where improvements to service delivery can build state legitimacy—has underpinned state-building policy, this approach has been widely criticised in the more recent literature, as we discuss below (Mcloughlin 2018). Social policy is defined broadly to encompass a system of public service delivery that includes social insurance, social safety nets, health, housing and education services, and a political settlement reflecting the social rights of citizens and residents. Related to social policy is the more recent concept of social protection. As defined by Devereux and Sabates-Wheeler (2004, p. 10), “social protection describes all public and private initiatives that provide income or consumption transfers to the poor, protect the vulnerable against livelihood risks, and enhance the social status and rights of the marginalised; with the overall objective of reducing the economic and social vulnerability of poor, vulnerable and marginalised groups”. Together, global, national and local providers of social services form the social policy landscape of a country.

The paper is based on countries in the Arab sub-region primarily because the research conducted focuses on Arab countries affected by conflict. These countries share similar social and political challenges such as informality, low social protection coverage and government budget deficits. Quantitative data is drawn mainly from the Arab Barometer3 Survey (ABS) data for the following countries: Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen. The ABS data allows us to explore broad patterns of micro-level social grievances in relation to state functions. These have been identified by other key scholars as necessary to provide deeper understanding of conflict (Cammett and Salti 2018).

The paper brings together three novel perspectives in order to examine the linkages between SL, SD and conflict in MENA: first, it adds new empirical insights from the Arab countries where the study of service delivery in relation to state legitimacy research is narrowly dominated by two models of welfare based on the role of Islamic movements and the Rentier state; second it brings to bear a social policy perspective whose core focus is, after all, the equitable provision of social and public services, although empirically this has historically focused on high-income Western countries (Barrientos 2013); third, it critically reviews the literature on service delivery, state legitimacy and conflict in relation to the Arab region, which has received little academic attention so far. In so doing, the paper’s point of departure is a growing body of multi-disciplinary literature on state legitimacy, which argues that the analysis of state legitimacy, service delivery and conflict should start with discussion about the nature of the state in the local context and an analysis of local normative perceptions (Mcloughlin 2015; Stel and Ndayiragije 2014). As noted earlier, we emphasise the importance of looking beyond the state by considering non-state providers of service-delivery as well as community and international level actors. Our analysis incorporates micro-level Arab Barometer survey data as well as insights from fieldwork conducted with social policy makers and service-users in a range of Arab countries (funded by various grants including the UK Economic and Social Research Council and the Carnegie Corporation of New York) in order to highlight Arab citizen perceptions of state services and legitimacy. This approach supports more critical schools of thought in the literature that seek to re-frame the study of the state in low- and middle-income countries (Pitcher et al. 2009; Nay 2013).

Two key arguments are made, one empirical, relating to the distinctiveness of the MENA region, and the second more conceptual in relation to the study of the relationship between service delivery, state legitimacy and conflict. First, we argue that sub-national forms of identity (such as religion, tribe or sect) are especially important drivers of service delivery in MENA countries, a feature that helps to explain why the connection between poor service delivery and state legitimacy or conflict is weaker in the region. Second, we argue that the social and political analysis of service delivery is required to better understand these relationships, hence the usefulness of a social policy perspective which highlights that the form of political participation is an important determinant of the link between service delivery and conflict, and that service delivery may need to support the expansion of social welfare if it is to be effective. A related point is the finding reported in this paper that Arab citizens attribute greater importance to the state of the economy and access to jobs than they do to the delivery of public services. We conclude, therefore, that to better understand state legitimacy and service delivery in MENA, further research on how different forms of political participation address social rights and equality is needed.

It is worth noting here what the analytical benefits of a social policy perspective in the study of state legitimacy are: (i) the social policy lens draws attention to the issues of membership, allocation and entitlement (Jawad et al. 2019), which reveal how citizens are socially and politically organised in a society and how they access key services and social benefits. This helps to reinforce the notion of the political embeddedness of service delivery and, therefore, how social ties can be formed or broken, leading to the possible risk of conflict; (ii) the social policy lens de-emphasises the value of service delivery as purely a political tool for state legitimacy in favour of emphasising its welfare function and contribution to social cohesion and wealth redistribution—these being important constituents of peace-building processes (Midgley and Piachaud 2013). This raises the issue of considering how service delivery actually contributes to social welfare, rather than just enhancing trust in the state or political leaders. This links to a wider issue pointed out by Sedgwick (2019) about legitimacy being deserved or not; (iii) in social policy, service delivery is a relatively newer function of the modern nation state, which is especially characteristic of the European welfare states after the Second World War. Social rights are the rights related to services and social benefits. They do not automatically flow from the political right to vote so political participation in elections is not enough to understand how state legitimacy may be enhanced. Arab states, similar to other developing countries, are grappling with a range of structural pressures, from low political participation and low trust in government for all citizens to ensuring law and order over their territory to providing accessible health and education services to their populations.

The paper is based on both qualitative and quantitative data. For the qualitative data, we draw on document analysis of social protection expenditures and first-hand interviews with policy makers and non-governmental organisations and policy labs funded by various UK and international research projects (including ESRC and the Carnegie Corporation of New York) to understand the normative underpinnings of social policy in the Arab countries. This data is not presented here, as the purpose of this paper is to reexamine the state of knowledge in a new light in order to begin to identify pertinent lines of enquiry for the study of C, SD and SL in MENA. The quantitative data covers state social welfare spending on health and education that is based on World Bank World Development Indicators (WDI) data, with the larger proportion of data discussed in the paper drawn from the ABS. The latter provides opinion data of Arab citizens about a range of political and social issues in their countries. ABS data cover issues of trust in political leaders as well as concerns about the key challenges facing Arab populations. It is a face-to-face, high-quality survey, offering a unique opportunity for the comparison of public opinion in the Arab region. Given the absence of recent census data in many Arab countries, the sampling frame for this survey is constructed using maps paired with the latest population estimates from the statistics authorities in the respective country covering all citizens ages 18 and above. We use the most recent available dataset: wave five conducted in 2018–2019, covering 12 countries, namely Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen4. The number of respondents was around 2400 respondents in most countries, as illustrated in Table A1 in the Appendix A. Before moving further, a brief note is necessary to explain our use of the key concepts that guide our analysis (the concept of service delivery has already been defined above):

(1) State Legitimacy comprises two forms of legitimacy: one normative and one explanatory or empirical (Sedgwick 2019). The normative understanding asks what forms government should take and, drawing on Western political philosophy, concludes that democratic forms of government are the gold standard of state legitimacy. On the other hand, the explanatory understanding emphasises “what forms of government are obeyed in practice”, and therefore focuses on the perceptions of citizens and key stakeholders. This links to Max Weber’s ([1922] 1978, p. 213) original concept of “the belief in legitimacy” (Legitimitätsglaube) (cited in Sedgwick 2019). A significant body of literature has emerged in support of this view and this paper follows this school of thought in highlighting micro-level data on citizen perceptions of Arab state legitimacy as well as disaggregated or more contextual understandings of the state in MENA. To this end, Schwarz (2008, p. 600) has noted that “focusing on a functional understanding of statehood allows to highlight where Arab states are strong (security function and in times of oil booms, welfare function) and where they are weak (representation function, and in times of fiscal crisis, welfare function)”.

(2) Conflict, according to Kivimaki’s (2021) paper, is measured in relation to the number of fatalities that stem from organized violence, based on Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) measures. According to the UCDP, organized violence covers state-based conflict (the use of armed force where one of the parties is the state or government), non-state conflict (armed force between two organised groups which are not the state), and “one-sided” violence (where the state uses force against civilians). Whilst acknowledging that conflict can be understood more broadly as a situation where structural, direct or cultural violence are manifest (Galtung 1969), our discussion of conflict will focus on situations where there is organized violence present. Since our study is based primarily on qualitative data, we will not limit our analysis to those situations where 25 battle deaths or fatalities are recorded in a given year, as per UCDP definitions.5

The paper is organised as follows: the next section examines the current state of literature on service delivery and state legitimacy; Section 3 sets out the main characteristics of the Arab state and identifies the gaps in the theoretical literature. To set the scene for the social policy analysis, it reviews data on key government health and education spending and examines the overarching socio-economic trends across conflict- and non-conflict-affected Arab countries. Section 4 moves on to the micro-level setting by presenting the ABS data and the results of the statistical analysis on citizen perceptions of their political leaders and socio-economic challenges in their countries. This provides scope to understand the demand side of social services. Section 5 engages more deeply with the social policy perspective by offering two institutional models of service delivery in Arab countries based on qualitative research. These are denoted as a state-based distributive model and a non-state (mainly religious) model. Section 6 synthesises the paper’s findings to offer explanations of the relationship between SL, SD and C in MENA as well as highlighting new lines of enquiry that emerge from the data analysed. The paper then concludes by reflecting on the main hypotheses set out by Kivimaki (2021) for this Special Issue.

2. The Relationship between Service Delivery, State Legitimacy and Conflict

Before moving to an analysis of the MENA region, this section takes stock of recent theoretical and conceptual literature on the relationship between service delivery, state legitimacy and conflict. It concludes by highlighting some implications of this recent literature for our understanding of the MENA region.

2.1. Service Delivery, State Legitimacy and Conflict

There is a long-held assumption in the state-building literature that improving service delivery leads in a straightforward way to improvements in state legitimacy (a “virtuous circle”), but several recent studies have found that this relationship is non-linear. Mcloughlin (2015, p. 341) argues that the relationship between state legitimacy and service delivery is “conditioned by expectations of what the state should provide, subjective assessments of impartiality and distributive justice, the relational aspects of provision, how easy it is to attribute (credit or blame) performance to the state, and the characteristics of the service”.

The case of Sri Lanka (for example in Mcloughlin (2018) shows that where there is a lack of trust in the state’s motivations, service provision can promote feelings of unfairness, and actually erode state legitimacy with certain groups, when it is perceived to have been distributed unevenly. This finding has been reflected in the flagship World Bank’s (2018) Pathways for Peace report, which stresses that the uneven delivery of services can undermine state legitimacy, especially when it feeds into pre-existing narratives or the experience of exclusion. It is often the perception of whether services are delivered fairly that is more important than the reality. A long-running research study into service delivery and state legitimacy based on research in DRC, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal and Uganda (the Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium) generated four key findings (McCullough et al. 2020). First, state legitimacy is co-constructed, not transactional. In other words, legitimacy is not simply a reflection of people’s experience of the state but rather based on a complex interaction between people’s beliefs about how the state acts and their experience of it.

Second, the study finds that “services become salient in the construction of legitimacy if they (re)produce contested distribution arrangements” (McCullough et al. 2020, p. iv). The project found some instances where state legitimacy was boosted by improvements in service delivery and found that these instances occurred when services were “connected to meta-narratives that delegitimise an authority” such as narratives about “disputed distribution arrangements, particularly between elite groups and excluded groups” (McCullough et al. 2020, p. iv). The third finding was that basic services do not necessarily “break or make the state” but that they may provide “teachable moments” (McCullough et al. 2020, p. v). Services can help contribute to a gradual process of shifting people’s expectations of the state—either by improving it or by reinforcing a wider delegitimising narrative. Whether these narratives connect will depend a lot on the person’s group identity and other factors.

The fourth finding was that the state “may not need to legitimate its power to all citizens in order to maintain its power” (McCullough et al. 2020, p. v). States will often shift between strategies of control and legitimation over time. In contexts where the state’s approach to certain groups is repressive, “increased investment in basic services in areas where these groups are the majority is unlikely to have an impact on perceptions of state legitimacy” (McCullough et al. 2020). According to the Democracy Index, the MENA region has the highest level of repressive governance in the world, so this finding seems particularly relevant and is worthy of further exploration.

Most existing literature on state legitimacy has failed to account for subnational variation or how and why state legitimacy is generated and maintained for different groups or regions. As Gunasekera et al. (2019) show in their study of Sri Lankan state legitimacy, legitimacy is rooted in narratives that vary sharply across groups and regions. Specific services are connected to different ideologies and narratives, and different groups are interpolated with these in different ways. Furthermore, the state itself does not manifest itself in a uniform way to all groups and is more complex and elusive than is normally depicted in the existing literature on state legitimacy. In Fragile-conflict-affected countries (FCC), the state’s authority and legitimacy is typically patchy and contested amongst a range of state and non-state institutions. This contestation is particularly acute in borderland or frontier regions (Plonski and Walton 2018). As Cheng et al. (2018) have argued, “[i]n such contexts, stability may be dependent less on how well formal government institutions perform and more on the “bargaining equilibrium” that emerges between elites to ensure that they cooperate and engage with each other rather than attempt to pursue their interests through the use of violence”.

To understand the connection between conflict and state legitimacy, therefore, it is important to (1) disaggregate the state and to examine the role of both state and non-state actors, (2) to look beyond the state level and try to understand sub-national variation and how narratives about the state and services are different across groups (e.g., for some, agriculture is the key factor, and the state’s image and legitimacy is rooted in its support for this sector. This is particularly important in consociational systems (such as in Lebanon) or countries where political order depends on patronage-based legitimacy (Mourad and Piron 2016). Looking beyond the level of the state also implies (3) paying more attention to regional and international actors. These themes will be developed further below.

2.2. The Political Marketplace

Some more recent work has sought to reconceptualise legitimacy and authority in “fragile and conflict-affected countries” (FCC). Moving away from a western state-building approach, which is based on normative Weberian ideas of what a legitimate state looks like6, recent international relations and political science literature have sought to develop a more nuanced and varied depiction of what local legitimacy looks like.7 De Waal’s “political marketplace” framework (De Waal 2009, 2018) is critical of Weberian approaches to understanding state legitimacy, which assume a relatively straightforward connection between state capacity, legitimacy and peace. The political marketplace framework highlights four key factors, which De Waal and others have argued are particularly salient both in Africa and in the “Greater Middle East” region: (1) politics is regulated less by formal and institutional rules and more by interpersonal relationships and financial transactions to buy loyalty of key elites, (2) political finance is derived mostly from externally derived rents rather than domestic sources, (3) control over the means of violence is distributed among elites rather than concentrated in the hands of a single ruler, (4) the terms of the political marketplace are regionally and internationally integrated. By highlighting the extent to which international actors are heavily implicated in the political marketplaces, the political marketplace framework (and other political economy frameworks such as North et al.’s 2009 “Limited Access Order” approach or Khan’s 2010 notion of “political settlements”, which it builds on) highlights that while western states may be rhetorically committed to promoting liberal states and liberal peace in the MENA region, in reality their policies are more designed to maintain the established order (see, for example, Turner (2015) on the Occupied Palestinian Territories). One criticism of the early political marketplace literature is that it underplays the role of identity (see Tschunkert and Mac Ginty 2020). More recent work by Kaldor and De Waal 2020) has sought to address this gap. Hadaya (2020), for example, explores how existing sectarian cleavages in Syria were instrumentalised by the Assad regime and contributed to the descent into entrenched armed conflict.

This brief review of existing literature generates two key insights for our questions about fragility, grievances and conflict in the MENA region and why the link between state legitimacy and conflict seems weaker in the MENA region than elsewhere. First, the general literature on state legitimacy and service delivery shows that the link between the two is non-linear, and to understand the connections, we need to adopt a locally-rooted approach which is alert to the ideologies and narratives that frame service provision in any given context (including the analysis of sub-national variation). Second, existing approaches have tended to neglect the way in which states in sub-Saharan Africa and the Greater Middle East are often structured not according to liberal norms (as assumed by western donors) but rather according to the rules of the political marketplace. De Waal’s political marketplace framework highlights factors that support directly Kivimaki’s general findings about the importance of political factionalism (high levels of competition between elites, often structured along ethnic or sectarian lines, which are monetised and central to the maintenance of political order), the importance of oil revenues (and other external rents) and the importance of external intervention (or high levels of external penetration) for explaining the MENA region’s exceptionalism.

3. Understanding the Arab State

This section contextualizes service delivery and legitimacy through a discussion of the key characteristics of Arab states and brings to bear descriptive data that explains the social policy background of the issues discussed in this paper. Schwarz (2008) explains that in the Middle East, generally, state formation was, as in other colonised regions of the world, driven by international geo-politics and the interests of Western powers. First, it is important to recognise the diversity of state structures in Arab countries which vary from the consociational democracy of Lebanon to the one-state rule of Syria and Egypt to the monarchies of the Arab Gulf, Jordan and Morocco. However, it also fair to argue that oil rents (and later political rents) made possible the development of a centralised state apparatus which, today, remains more of a “façade of statehood” that is dominated by military, tribal, sectarian or patronage-based affiliations.

Hinnebusch and Gani (2019) explain that the Middle East (of which Arab states form the largest country grouping) is the only world region where traditional monarchic rule is still evident even where countries regard themselves as republics. The dominant political model across the region is neo-patrimonialism, which is a “a hybrid that combines practices from the region’s pre-modern state-building inheritance with bureaucratic structures partly imported from the West….the neo-patrimonial state is usually considered “weak” in the sense of the ability to implement policies …. and especially foster economic development, but, at the same time, it is quite robust in its combination of different kinds (personal and bureaucratic) of authority” (Hinnebusch and Gani 2019, p. 4).

In his seminal work Beblawi (1990) noted that it was the combination of colonial rule and the fixing of an economic value to oil which helped to form more stable Arab states in the post-war era. The population groups seeking rule for themselves under the colonial powers took on the functions and role of the modern nation-states without fully resolving disputes over national territory or identity. Hence, the Arab nation-states that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s were primarily focused on law and order and maintaining security with minimal financial and administrative state capacity. It was later in the 20th century that the idea of a social contract and an obligation to provide public services emerged.

According to Springborg (2020), the limited access order framework (first developed by North et al. 2009) explains the dominance of clientelism in the MENA region as the model by which rulers control society and provide services. This occurs in both the mainstream public space and in the non-state sector where religious, especially Islamic political movements and other kinship-based entities, substitute state presence. Limited access to resources goes hand in hand with a lack of “political entrepreneurship” in MENA (Springborg 2020, p. 66). In connection with this, institutions of the “deep state” are key to understanding how MENA bureaucracies and official state institutions operate (Springborg 2020, p. 69). Originating in Turkey, the deep state concept (derin devlet) (Springborg 2020, p. 68) refers to a “network of individuals in different branches of government with links to retired generals and organized crime, that existed without the knowledge of high-ranking military officers and politicians”.

Focusing on the influence of oil on state formation in the region, Schwarz (2008) has argued that the existence of a Rentier state serves as a strong impediment to democratic rule and helps to conserve socio-political norms in Arab societies and polities, such as the patrimonial nature of social interactions and primordial loyalties based on allocation patterns. The presence of an allocation state, not based on extraction contracts, thus explains why the process of state formation in the Middle East has not followed a path of economic development, sustained reform and democratization.

Schlumberger (2010) pulls together some of these strands by arguing that there are several factors which have helped non-democratic Arab regimes “maintain power since the 1970s: (1) religion; (2) tradition; (3) ideology; and (4) the provision of welfare benefits to their populations”. He argues that in many MENA states, the importance of religion in underpinning power is low or in decline and suggests that traditional and material forms of legitimacy remain more important. Emphasising the production base of a nation-state, Delacroix (1980) argues that the capitalist world economy is diverse and certain modes of production do not foster the development of class identity, and as such states emerging under these conditions are influenced by political drivers other than class. This is the case of Asian, African and Arab countries.

Using the example of African state scholarship, Pitcher et al. (2009) argue that analysis of state legitimacy has been too narrowly focused on formal bureaucratic structures and small territorial spaces. This theoretical orientation is influenced by political bias in the mainstream literature against personalized relations in the public realm and a focus on explaining why liberal democracies have not taken root outside of Europe. In the authors’ words, “rather than questioning the supposed exclusion or neutralization of personal ties in rational legal bureaucracies, these analysts have seen such relationships as either impossible to institutionalize or as “polluting” the public sector” (Pitcher et al. 2009, p. 138). To this end, the authors argue that there is a misinterpretation of Weber’s work whereby the rational-legal model of authority is considered the gold standard, leading to a neglect of Weber’s original argument that patrimonial linkages are a natural form of reciprocity in all societies and support valid state formation. Patrimonialism is a “voluntary form of compliance of subjects” (Pitcher et al. 2009, p. 138), and to a certain extent we find evidence of this through qualitative research in the Arab countries (as discussed in this paper). Bellin (2012) specifically identifies patrimonial influence in the MENA countries’ military bodies. She argues that in the Middle East, extensive access to rent and international support, coupled with the patrimonial political structures of Arab countries, has fostered a capacity for repressive politics.

Hinnebusch (2020) has further expounded the importance of the local populace in state formation through the categorisation of MENA countries as authoritarian-populist. Using the example of Syria to illustrate the complex interaction between state legitimacy and a social contract based on populism, the author shows how that the Ba’th regime’s political roots and support base was in the Syrian villages that it had managed to incorporate through land reform and party organization. Hafiz al-Asad wooed peasant producers with subsidized inputs and good state prices for crops which were later undone by the neo-liberal reforms of his son and successor Bashar al-Asad’s in the 2000s. Combined with the impact of a harsh drought, these reforms led to the rise of the Islamic rebellion and the Syrian civil war. Hinnebusch (2020) argues that flour and bread subsidies have remained a symbol of the populist social contract in Syria and were maintained even at the height of the conflict both by the Bath’ist state and its Islamic opponents who had emerged from the disgruntled villages of Eastern Syria. Sobhy’s (2021) analysis of education and the social contract in Egypt argues that the protection dimension (relating to security, rule of law and protecting territorial integrity) is more important at underpinning state legitimacy than provision (delivering services) or participation (doing this in an inclusive and democratic way), a finding that could reasonably be extrapolated across the region based on our analysis of the ABS survey data below. She argues that before the uprisings, Arab regimes sought to compensate for a decline in provision by improving participation. However, she argues that any approach at boosting state legitimacy and the social contract should not neglect the protection dimension as well.8

A key argument proposed in the social contract literature is that boosting service provision may not be enough to reverse declines in state legitimacy in the region—protection and participation are also important (Loewe et al. 2020). These arguments lend important credence to the social policy perspective incorporated in this paper, and this issue is explored further in the next sections of the paper. From here, it is possible to draw linkages with Sedgwick (2019, p. 99), who notes that from an explanatory perspective of legitimacy, the Arab state may have a claim to legitimacy, but whether this is “deserved” is another matter. Perceived legitimacy is central to explaining both authoritarian resilience and state collapse and recent history, especially following the Arab uprisings of 2011, which show that state collapse seems to be the only viable alternative to authoritarianism in Arab countries. Sedgwick (2019) distinguishes between authoritarian politics, where the terms of reference for analysis are general structures such as “regime” or “state,” in contrast to democratic politics, where a more dynamic distinction is made between “government or leadership on the one hand and state institutions on the other hand, and between both of these and the political system or constitution” (Sedgwick 2019). In this view, democratic politics is legitimate whereas authoritarian politics is not. The degree of legitimacy different institutions enjoy may vary, whilst in an authoritarian system, and leadership may change even if the authoritarian system persists. According to this approach, Sedgwick (2019) notes that the key form of legitimacy that Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states demonstrate is output legitimacy as reflected in the broad range of social and welfare services they provide to their populations. In another categorisation by Schwarz (2008), GCC states also figure prominently as providers of welfare, hence we see that there is recognition of the role of welfare services in contributing to state legitimacy in the Arab countries, albeit with limited theoretical development and comparison to other non-Arab countries.

To further this argument, it is worth considering the patterns of social expenditure in Arab countries. These form the first step in integrating a social policy analysis and providing a contextual policy background for service delivery in this paper. Here we provide a descriptive overview in order to begin to identify more important lines of enquiry in relation to conflict and state legitimacy. First, it is noted that the already significant levels of poverty in the Arab countries have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as can be seen in the graph below.

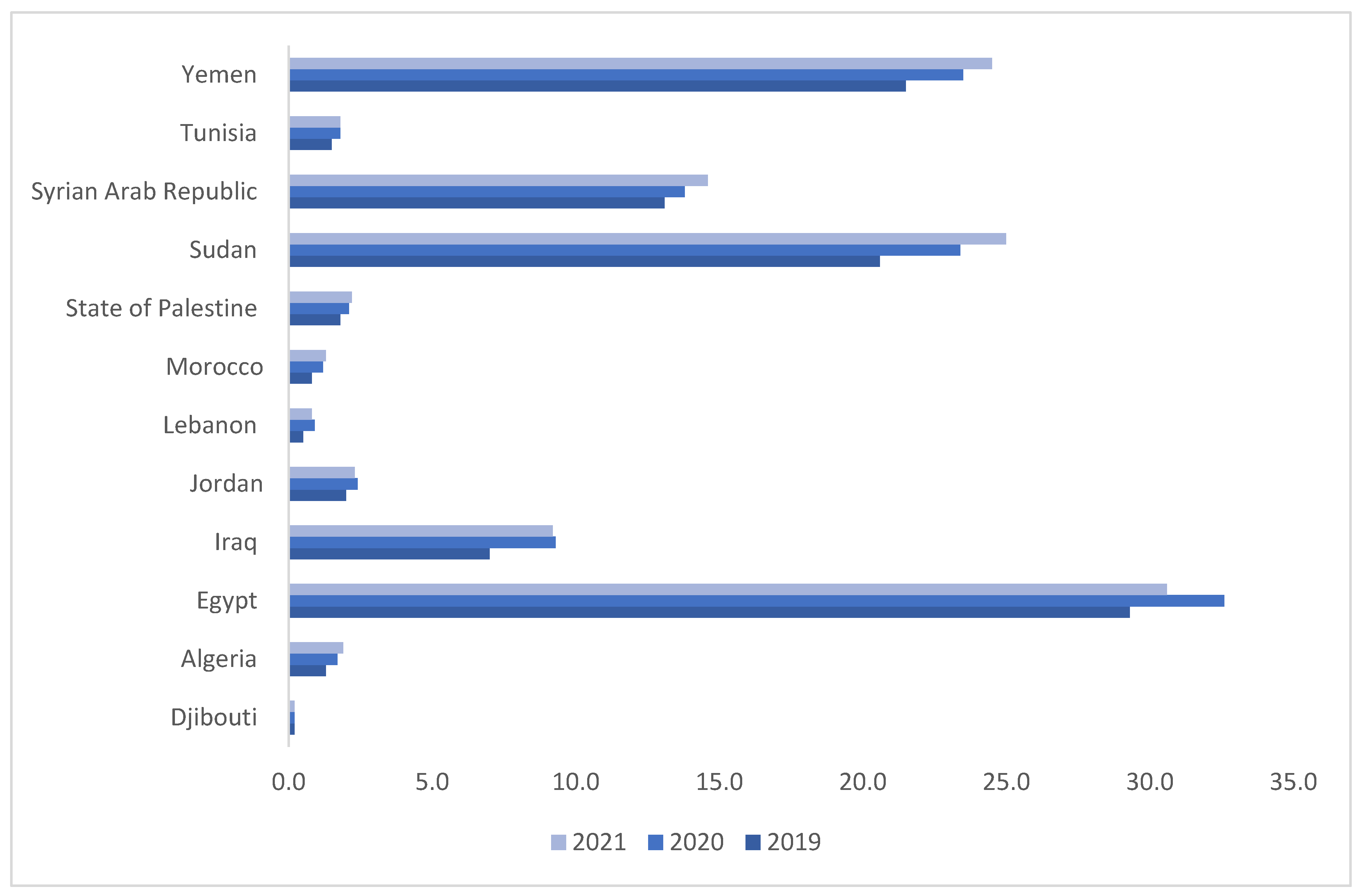

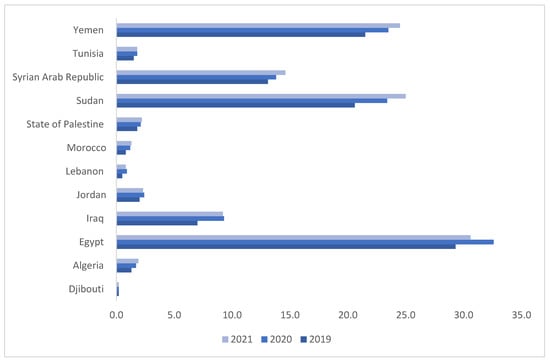

As shown in the Figure 1 below, the poverty headcount is significantly higher in crisis-affected Arabic countries such as Yemen, Syria, Sudan and Iraq. While poverty rates are likely to increase in almost all Arab countries because of the pandemic9, the magnitude of this increase is likely to be higher in conflict-affected countries. Indeed, between 2019 and 2021, the poverty headcount ratio increased by around 1 percentage point in countries such as Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Sudan. Indeed, conflict has had a negative impact on social institutions and infrastructures, which explains the high poverty in the affected countries (Abu-Ismail 2020). The expectation, therefore, would be that state legitimacy would fall in these circumstances thereby drawing attention to the role of social services such as health and education in supporting peace. We take a cursory look here at government spending in the Arab region.

Figure 1.

Headcount poverty ratios (%) using national poverty lines. Source: (UN-ESCWA 2020). Note: The results are the output of the projected scenario; for more details about the results of other scenarios, please see UN-ESCWA (2020).

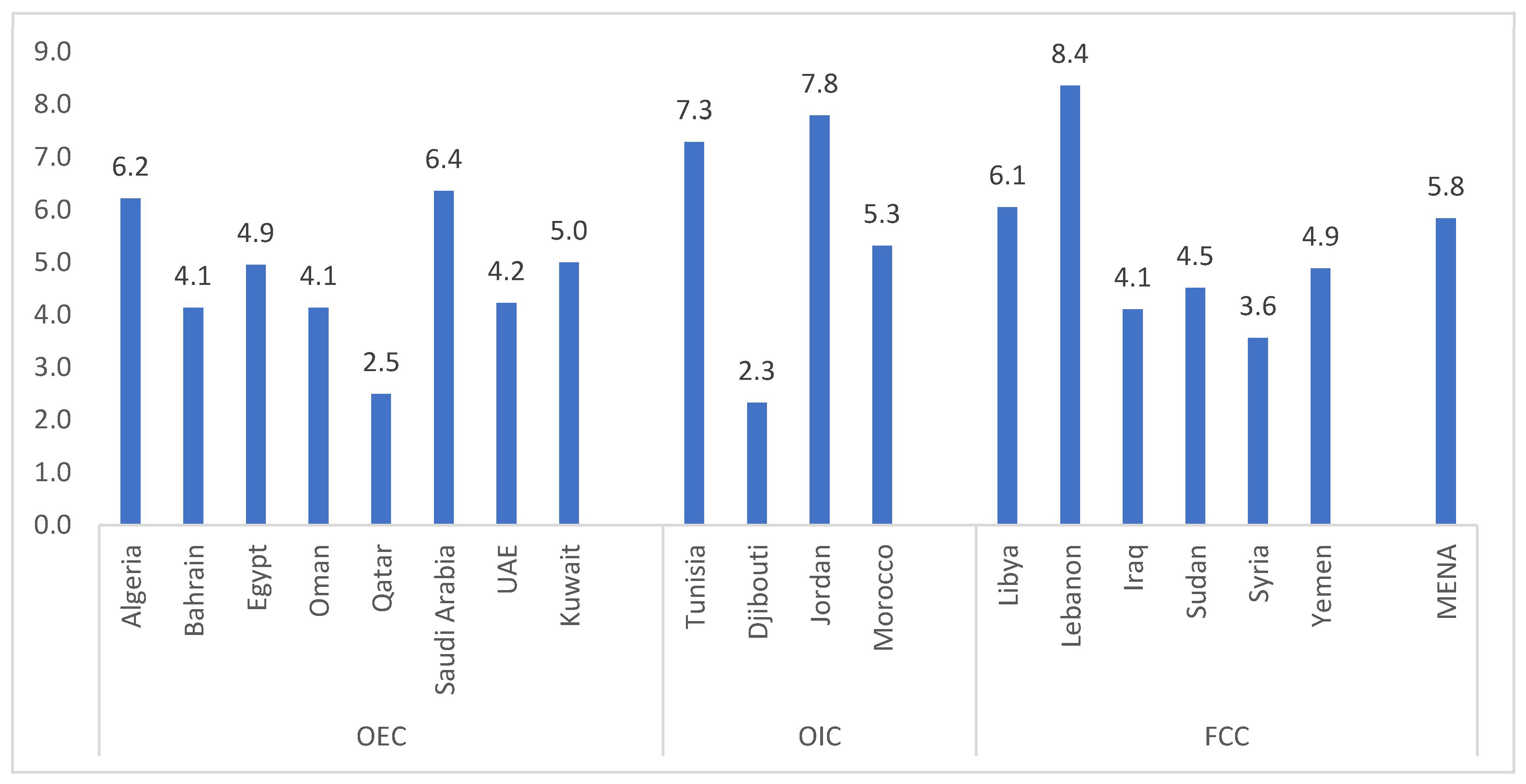

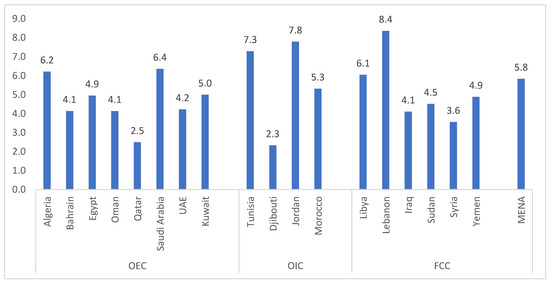

How does this snapshot of poverty reflect against the general trends in social spending in the Arab countries? It is well known that Arab countries have spent more on the military than on social welfare such as health and education (El-Ghonemy 1990). Figure 2 and Figure 3 below show health and education expenditure spending data that is drawn from the World Bank WDI survey. As can be seen, most fragile and conflict-affected countries spend less than the MENA average health expenditures.10 Lebanon has the highest share of current health expenditures in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (8.4%), while Djibouti has the lowest share of health expenditures in GDP (2.3%). The level of health expenditures are low overall in MENA countries11 (5.8%) compared to the world average (9.89%) and other regions such as North America (16.42%), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (12.46%), Europe (10.14%) and East Asia and the Pacific (6.67%), as the share of GDP.12 In sub-Saharan Africa, the share of current health expenditure in GDP was slightly lower, at 5.09% in 2018. Furthermore, Figure 2 does not show a clear difference in health expenditures between conflict- and non-conflict-affected countries.

Figure 2.

Current health expenditure in 2018 (% of GDP). Source: World Development Indicators. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2021). Note: FCC: Fragile Crisis affected Countries, OEC: Oil Exporting Countries, and OIC: Oil Importing Countries.

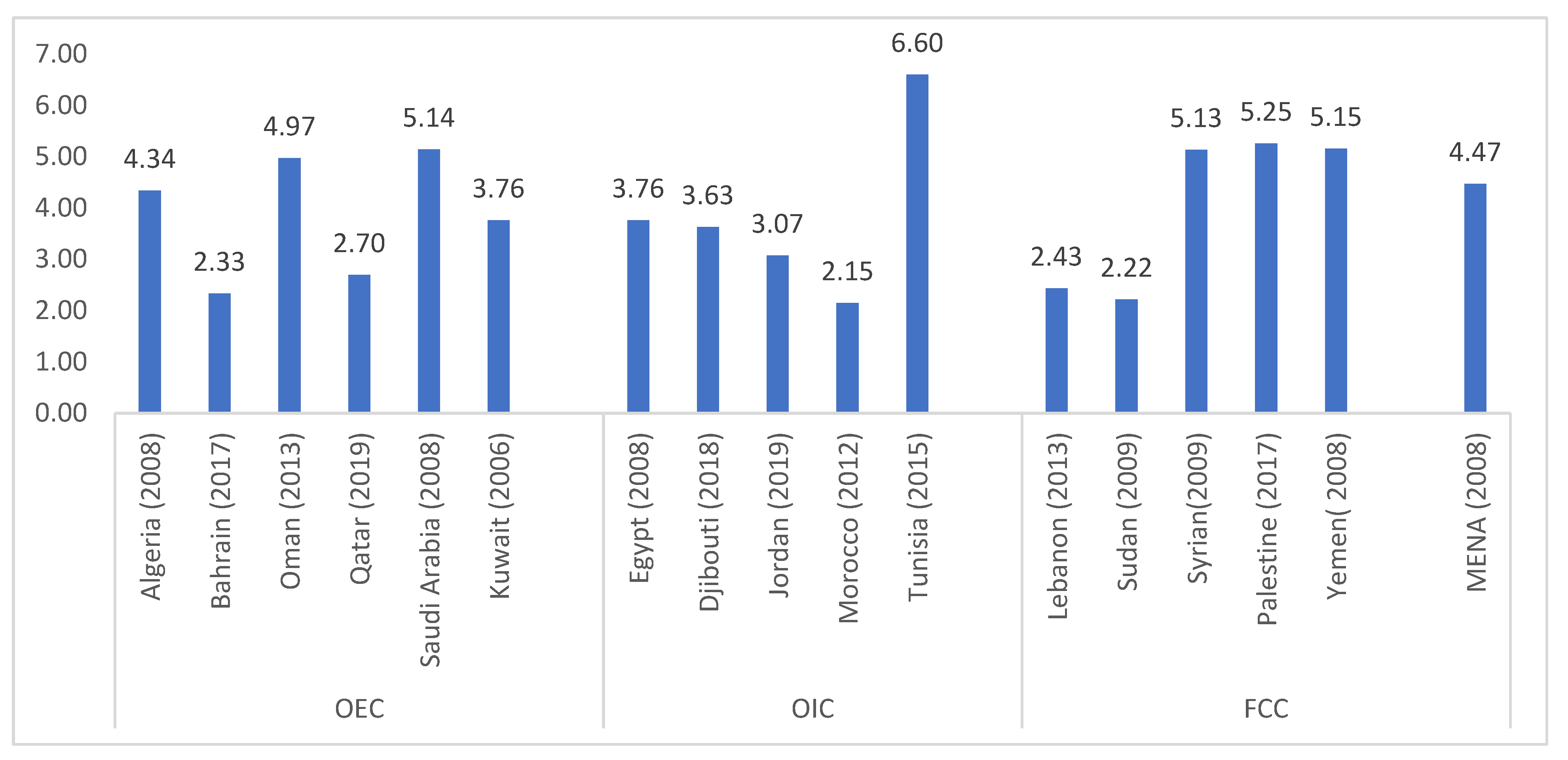

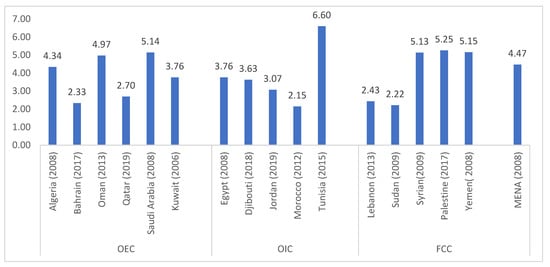

Figure 3.

Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP). Source: World Development Indicators. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2021). Note: FCC: Fragile Crisis affected Countries, OEC: Oil Exporting Countries, and OIC: Oil Importing Countries.

There are similar findings for education expenditure, as seen in the Figure 3 below. As shown, the highest expenditures on education were made in Tunisia (6.6% in 2015) and the lowest in Sudan (2.22% in 2009). However, low values could also reflect that the private sector and/or households have a large share in total funding for education, which is the case of the GCC. To compare with other world regions, the average government expenditure on education in the MENA region is 4.47% of GDP, which is close to the world average (4.5%), but lower than in OECD countries (5.01% in 2017)13, and slightly higher than East Asia & Pacific (4.15% in 2017) and sub-Saharan Africa (4.3% in 2018) 14.

Education and Health expenditures are generally low in both conflict and non-conflict countries in the Arab region, compared to other world regions. Hence, it is not possible to confirm the relationship of health and education expenditures on conflict by relying on social services spending alone, although this matter is worth exploring in further depth. Low social expenditures could be viewed as a lack of access to social services for the poor population.15 However, policies should be evaluated by their outcome rather than the amount allocated; also, attention should be paid to the demand for social services from the poor rather than only focusing on the supply (Morrisson 2002). To complement this macro-level perspective, the paper now turns to the key results from an analysis of ABS data of citizen perceptions regarding the socioeconomic situation in their respective countries and the level of trust in their governments and political leaders. Barometer survey data have been used in the analysis of conflict and state legitimacy issues and, given the lack of data availability, they serve as suitable proxy indicators for state legitimacy. One limitation of these indicators is that they are derived from cross-sectional data and only provide a snapshot of public opinion and therefore are not able to capture changes in peoples’ views or priorities over time, which may be important for developing a more nuanced understanding of how SD, SL and conflict are related.

4. Citizen Perceptions of State Institutions and Political Leaders in Arab Countries

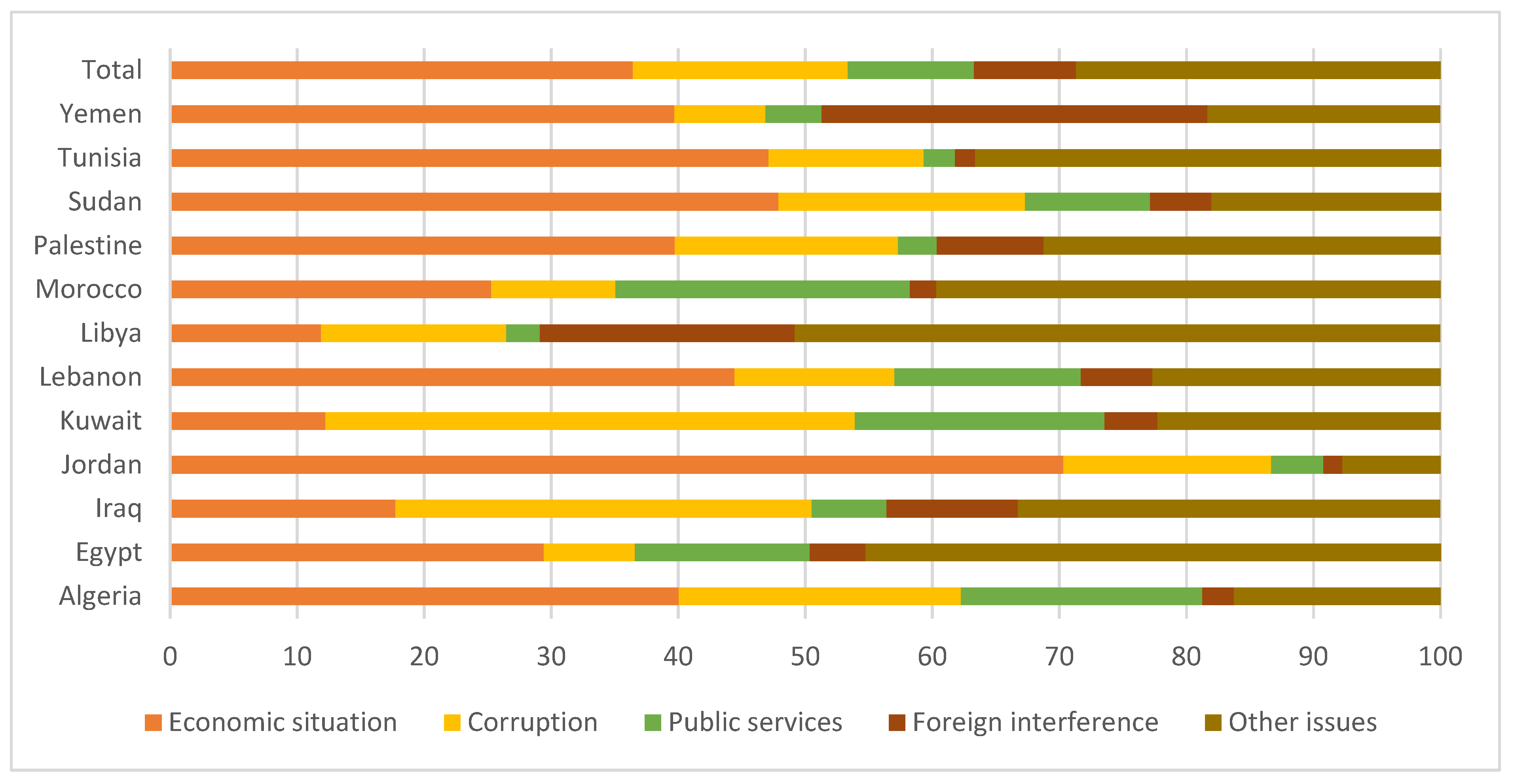

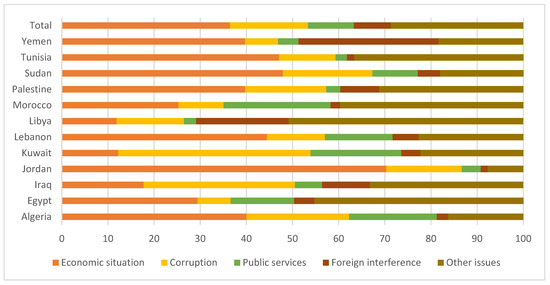

The ABS asks respondents about the important challenges facing their countries and the results, reported below, show that three stand out: the economic situation, corruption and public services are among the most important challenges facing the countries, as illustrated in Figure 4. A noteworthy finding is that international interference appears to be less important than domestic issues.

Figure 4.

Most important challenges in Arab countries. Source: Arab Barometer Survey Fifth wave (2018–2019). Available online: https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-downloads/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

Figure 4 shows that the most important issue facing Arab citizens is the economic situation (poverty, unemployment and inflation). This result is valid for almost all the countries except Kuwait and Iraq, where 41% and 32% of respondents reported that the most important challenge facing their countries is corruption. In Libya, the most important challenge would be foreign interference, according to 20% of respondents. Furthermore, financial and administrative corruption is also a concern for Arab citizens; 16.91% of all respondents in Arab countries report that it is the most important challenge. The cross-country comparison shows that in almost all countries, this challenge comes in the second position. For instance, in Algeria and Tunisia, 22.21% and 12.21% of respondents, respectively, report that corruption is the most important challenge facing the country. As will be discussed later in this paper, the higher importance attributed by Arab citizens to these matters in comparison to the delivery of services is an important marker of the relationship between SL, SD and C in MENA and deserves further research.

Poor public services, such as health and education, is identified as another important challenge in many countries. Nearly 10% of total respondents report that public services are the most important challenge in Arab countries; the cross-country comparison shows that 23% of Moroccans report that public services are the most important challenge. These compare with 19% in Algeria and Kuwait and around 14% in Egypt and Lebanon. This finding raises important new questions about the relative importance of services for the risk of conflict in Arab countries. It would be worth mentioning that the above analysis looks at relative rather than absolute concerns; indeed, the question asks respondent to pick 1 among 10 alternatives of answers16, which may have affected responses and makes it unclear how the conflict is related to social services and the economic situation. To address this issue, the following paragraphs will analyse questions asking about opinions on health and education separately. The ABS also asks respondents about their trust in government, parliament, political parties and religious leaders. The level of trust in these entities is illustrated in the following figure.

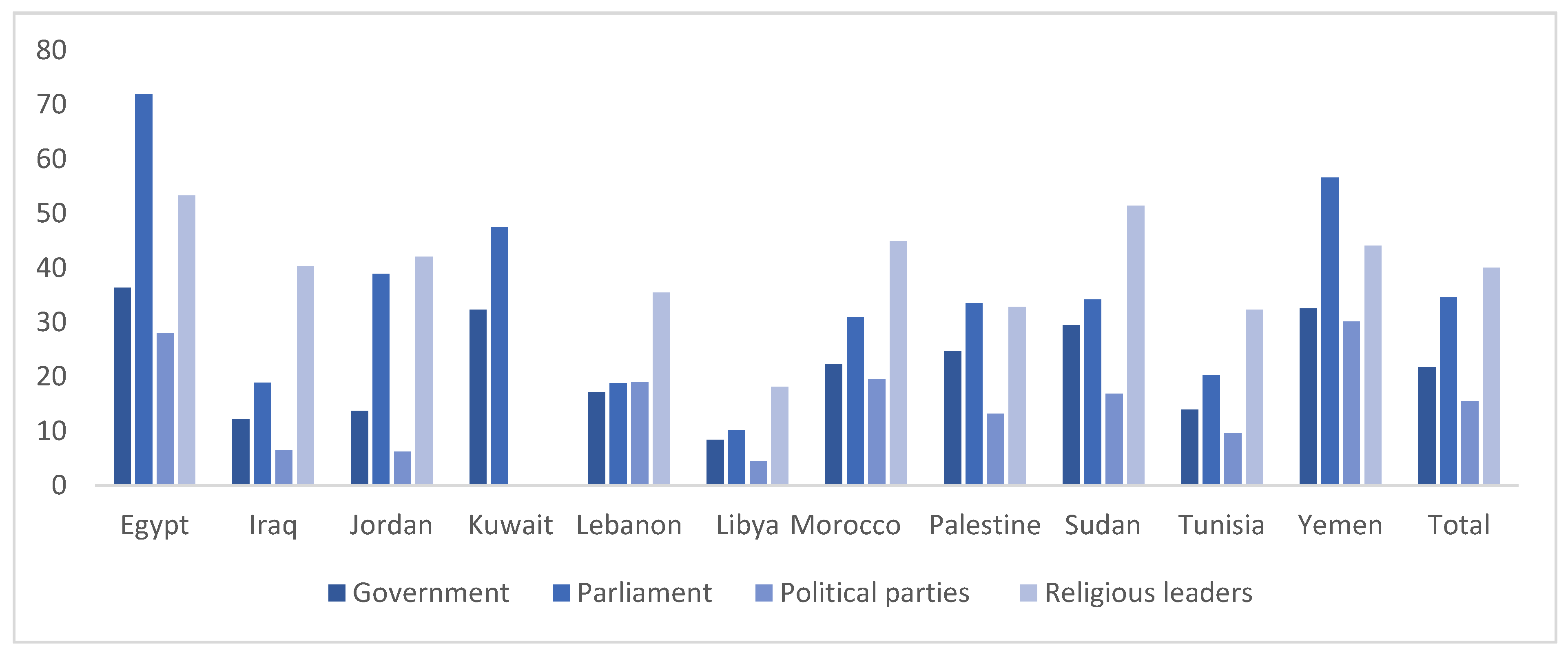

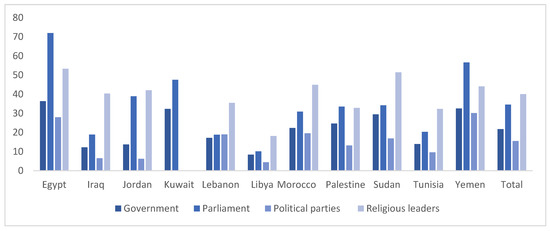

Figure 5 shows that the populations of the Arab countries are more likely to trust religious leaders and less likely to trust government and political parties. Indeed, the level of trust in government is low; an average of 21% of respondents declare trusting their government, which can be interpreted as state illegitimacy. The lowest trust in government has been observed in Libya (8.41%), Iraq (12.23%) and Jordan (12,75%), while the highest values of state legitimacy have been observed for Egypt (36.38%), Yemen (32.54%) and Kuwait (32.31%). Furthermore, on average, only 34,58% of respondents have reported that they trust parliament. The highest levels of trust are observed in Egypt (72%) and the lowest in Libya (10.15%). In addition, Arab populations do not seem to trust political parties, with only 15% expressing trust. The highest value is observed in Yemen (30.17%) and the lowest value is observed in Libya (4.42%). Finally, 40% of Arab populations population report they trust religious leaders, which is higher than the share of the population trusting the government. This result is valid for all countries. In Egypt more than half (53%) of the population report they trust religious leaders, but this percentage is lowest in Libya, at 18.11%. This data confirms existing knowledge in the literature.

Figure 5.

Percentage of people trusting government, parliament, political parties and religious leaders.Source: Arab Barometer Survey Fifth wave (2018–2019). Available online: https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-downloads/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

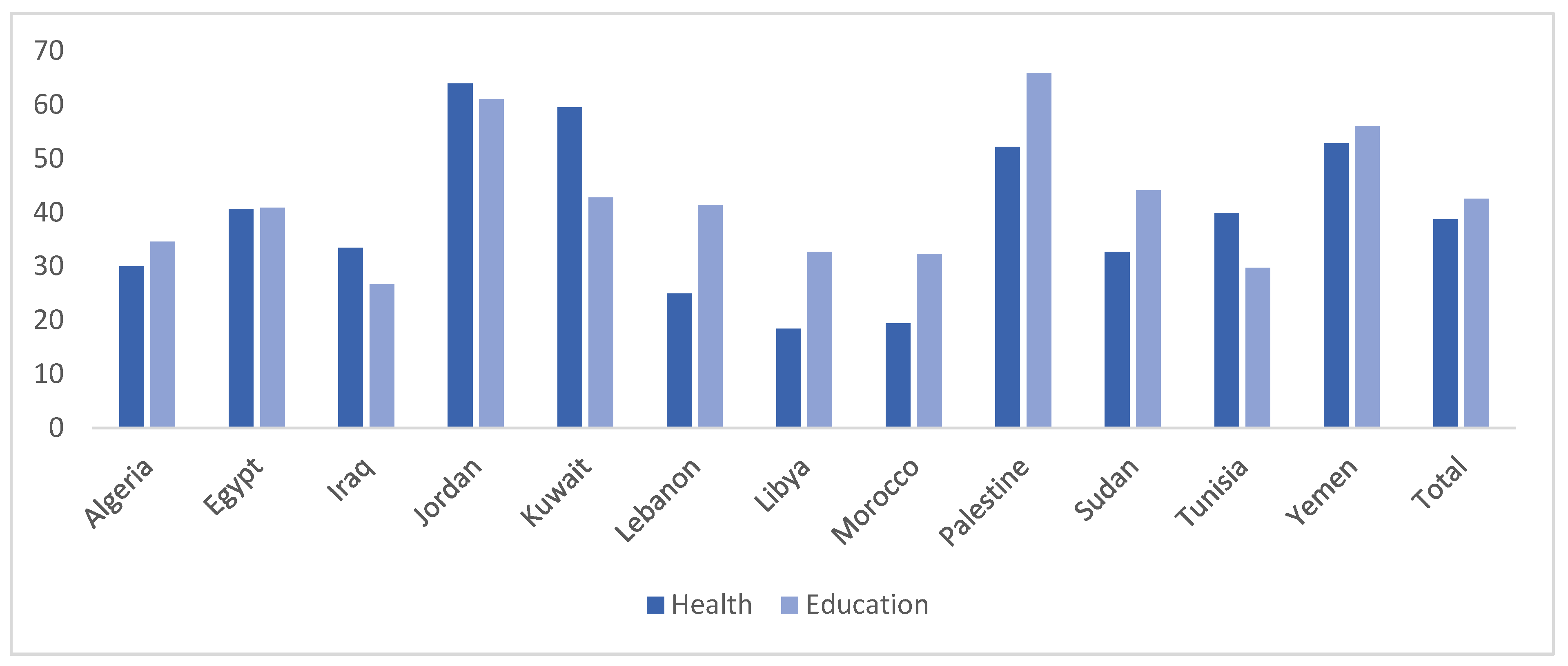

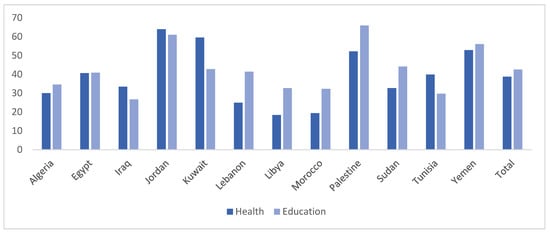

In terms of satisfaction with health and education systems17 in their countries, the results are shown below:

Health and education are two key aspects of the social policy system. The ABS data is limited in its coverage of services; hence, we use these two policy areas as the closest indicators to social policy expectations among citizens. Figure 6 shows that the percentages of people satisfied with health and education systems in Arab countries are 38.74% and 42.51%, respectively. This low satisfaction level may reflect the low quality of health and education services, which might not be in line with the population’s needs and expectations. The data shows that the highest level of satisfaction with health system is observed in Jordan, where more than 63% of the population report that they are satisfied, while the lowest level of satisfaction is observed in Libya, where only 18% of respondent declare they are satisfied. With regard to education, Palestine has the highest level of population satisfaction (65.9%), while the lowest level of satisfaction is observed in Iraq (26.65%). Indeed, conflict in Iraq and Libya has devastated many health and education infrastructures, which has made the quality and access to those services very low /restricted. Again, these data need further exploration; for example, Palestine is one of the countries most affected by conflict in the Arab countries, and yet it has a relatively high level of citizen satisfaction with the education system.

Figure 6.

Percentage of people satisfied with health and education systems. Source: Arab Barometer Survey Fifth wave (2018–2019). Available online: https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-downloads/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

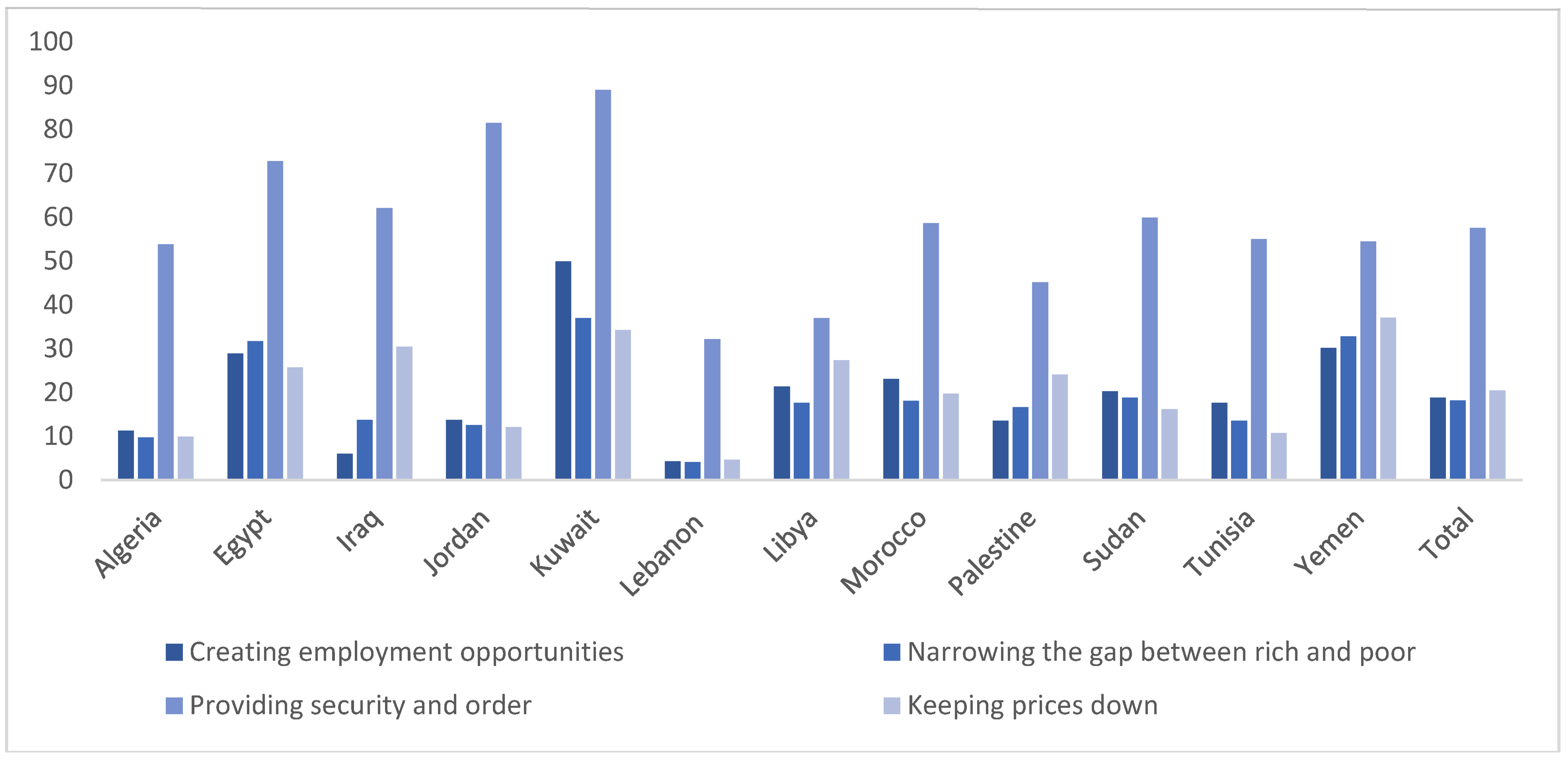

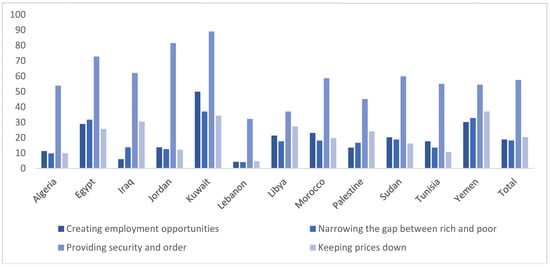

The ABS asks for opinions about a range of other policy areas that are relevant for a social policy perspective. These questions relate to government efficiency in many areas such as creating employment, providing security, reducing inequalities and controlling inflation. The results of these questions are summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Percentage of people reporting that the government efficiency is good by area. Source: Arab Barometer Survey Fifth wave (2018–2019). Available online: https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-downloads/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

Figure 7 shows that in all countries, the local population is more likely to report that government efficiency is good in providing security and order (57.55%). The lowest levels of satisfaction are in relation to employment and gaps between rich and poor. This is noteworthy, as these are critical areas of study in social policy although it is not possible to see a clear trend in the graph. Only 18.79% of Arab populations report that government efficiency is good at creating employment. This percentage is 18.18% in relation to narrowing gaps between rich and poor and 20.24% in relation to keeping prices down. The cross-country comparison shows that Kuwait is doing best according to their citizens except in keeping prices down. On the other hand, Lebanese citizens express the lowest satisfaction in all four areas.

These regional findings are supported by case study literature on Lebanon. A study on municipal service delivery by Mourad and Piron (2016), for example, argues that Lebanese citizens have very low expectations of the state, and that central and local government “do not derive ‘performance-based’ legitimacy from delivering services for all, and provide few opportunities for ‘process-based’ legitimacy, such as through participation mechanisms”. They do point out, however, that civil society protests in 2015–6 regarding waste disposal started to challenge state performance on specific service delivery issues, highlighting that the dynamics of the social contract are liable to shift over time.

Tschunkert and Mac Ginty (2020), in another study of state legitimacy in Lebanon, argue that most people are fairly ambivalent about the state, and that wasta (a system of family connections and networks that shapes the distribution of resources) is more important for most people. Tschunkert and Mac Ginty’s (2020) account of legitimacy in Lebanon highlights a profound lack of trust in government—the state is hollow, or a husk—and legitimacy is often invested in other institutions such as wasta or organisations such as Hezbollah, which sit largely outside of the state structures. Lebanon is also a society highly penetrated by international actors who shape the political marketplace profoundly.

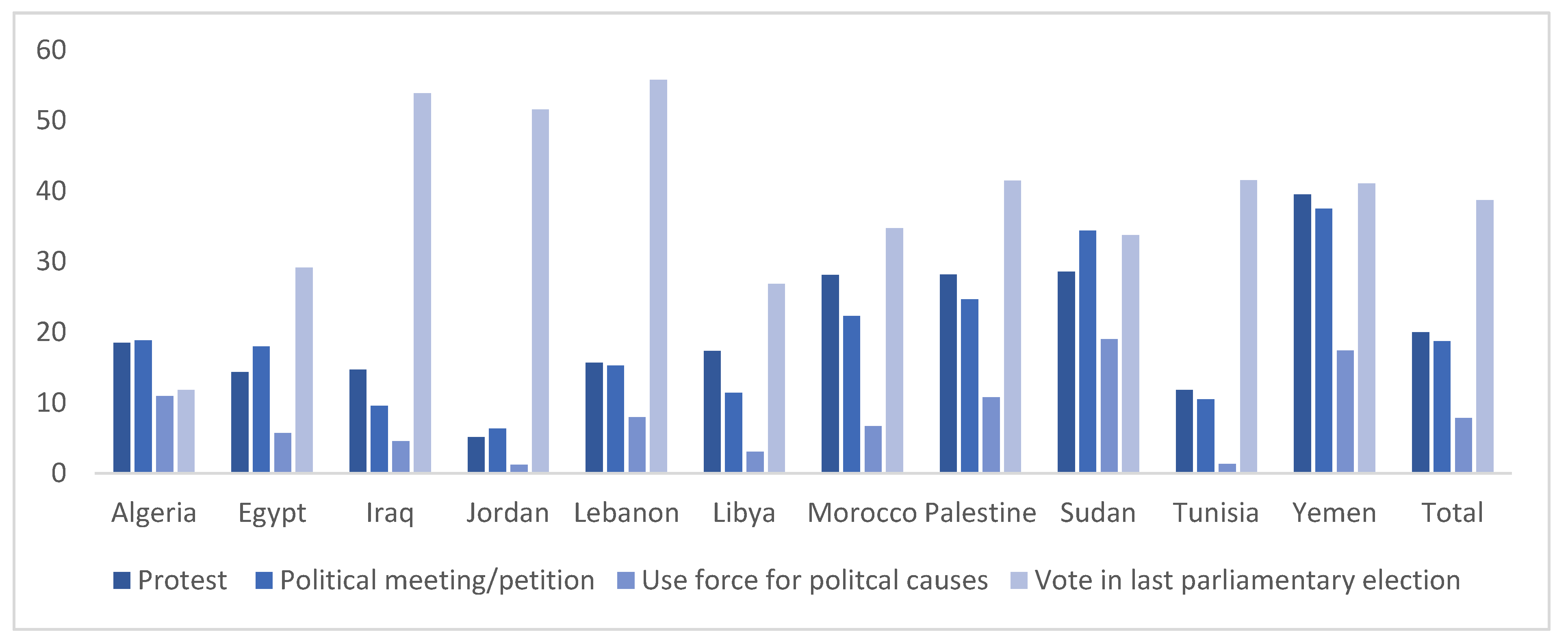

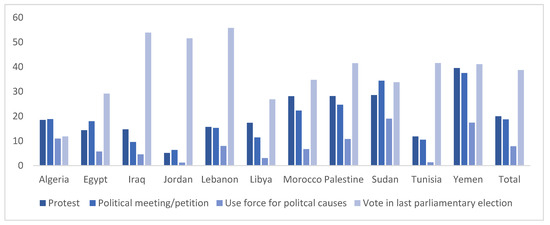

The low quality or lack of access to social services may lead Arab populations to riot or enter into conflict with the state (Kivimaki 2021; Merouani et al. 2021), although the general robustness of this relationship is questioned in the wider literature, as has been convincingly argued by Mcloughlin (2015). The ABS also provide data on participation in formal and informal political activities during the last three years (2015–2018/2019). The results are illustrated in the following figure.

As seen in Figure 8 below, formal political participation (voting in election) is on average higher than informal political participation (protest, political meeting petition, and the use of force for political causes). However, informal political participation is still relatively high in Arab countries compared to other regions18, and it is even higher than formal political participation in some countries, such as Algeria. In Yemen the participation rate in protest (39.51%) is nearly equal to participation in voting (41.1%). Furthermore, participation in protest is higher in conflict-affected countries such as Yemen (39.51%), Sudan (28.56%) and Palestine (28.17%) compared to other countries. There are also relatively high levels of participation in protests in Morocco (28.13%), which is similar to the rate observed in conflict-affected countries. How political participation translates into access to services requires further investigation that can help better explain the linkages between SD, SL and C.

Figure 8.

Percentage of people having participated in politics during 2015-2018/2019. Source: Arab Barometer Survey Fifth wave (2018–2019). Available online: https://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-downloads/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

Cammett and Salti (2018) also discuss micro-level data based on opinion surveys to highlight how social groups in Arab societies experienced social grievances differently and how this impacted on their participation in the Arab uprisings of 2011. In line with other observers, the authors argue that rather than social grievances being of a homogenous nature across the Arab world, and hence population mobilization on the basis of similar frustrations (such as lack of jobs), the logic of diffusion provides a better explanation for why citizens were led to the street. There are macro-level concerns that commonly affect all Arab countries, such as government failure to provide key services and job opportunities, especially since the late 1970s, and the rampant corruption and clientelism which was especially felt among the Arab middle classes. Such perspectives highlight the need for further qualitative research to understand the underlying mechanisms of conflict.

Diwan (2013) notes that the “middle class” was a key constituent of the Arab Spring uprisings and in fact the main counterpart protagonist to the youth population who are also considered leading mobilisers of the Arab Spring. According to Diwan (2013), the secular Arab middle classes had been historically co-opted into the “political settlements” since the 1950s because Arab rulers saw interest in keeping them on side. The middle classes either had posts in government or were allowed to form political oppositions, in both cases adding legitimacy to the authoritarian regimes that emerged in MENA post-independence. Again, further research is needed to explore the direct relationship among these factors.

To summarise, this quantitative overview offers only a preliminary picture of the situation and raises further questions. It has shown that levels of expenditure on key public services are generally lower than other world regions and that levels of satisfaction with public services are low, both in MENA countries affected by conflict and those that are not. What is also evident is that MENA populations are especially dissatisfied with their government’s performance in addressing unemployment and inequalities between rich and poor. These are issues of relevance to social policy and may act as compounding factors of conflict when they interact with identity-based drivers (Stewart 2008). Overall, the data appear to echo findings from case studies on countries such as Lebanon that poor standards of public service are to some extent expected by the population who generally have low levels of trust in government. The flipside of these low expectations of government is the wide array of public authority that exists in the MENA region, and in particular the high degree of trust in religious leaders. Finally, this quantitative analysis highlights the varied forms of political participation that exist in the MENA region, demonstrating that the importance of formal political participation (voting) is less than in other world regions. One important implication here is whether further research should explore forms of political participation that directly connect with service delivery, such as alternative forms of inclusion and decision-making that citizens are affiliated to MENA. The next two sections develop this argument further.

5. Explaining the Main Mechanisms of Service Delivery in Arab States

This section takes a deeper look at the social and political processes which underpin service delivery in the Arab countries by incorporating insights from qualitative research based on fieldwork in Arab countries exploring state and citizen perceptions and experiences of social welfare and social policy, providing necessary institutional analyses of the issues at hand (see Jawad 2009; and Jawad et al. 2019). We identify two dominant models of service delivery which shape social and political identities profoundly in the Arab countries, thereby taking the discussion of legitimacy, service delivery and conflict outside of the state. The two models help to explain the perceptions of Arab citizens in relation to the importance of service delivery and low expectations of the state. As such, this section enhances the ABS data discussion already provided and supports the re-examination of the literature based on a social policy perspective. For example, citizens may be less concerned about state service delivery because they are already receiving services through sub-national providers such as religious or patronage networks. This section therefore provides an explanation for the non-linear relationship between service delivery and state legitimacy.

First is a distributive model of state welfare characterising not only the Rentier states of the Gulf but also the patrimonial systems of leadership followed by most Arab countries and, second, a model based on the influential role of non-state approaches of religious groups is highlighted. Within these two models, there are two rationales deployed by political leaders for delivering services to citizens: the distributive model is based on the rationale of reducing “dissent” and the risk of protest as seen in the 2011 Arab uprisings. The non-state approach is based on a communal identity akin to the notion of a “right” as seen in the discourses of brotherhood and community among religious organisations (Jawad 2009; AlJabiri and Jawad 2019). This takes on populist notions of appealing to the downtrodden populations neglected by the state.

Although political actors providing services in Arab countries use welfare strategically to leverage political gain, they also call upon historical social bonds in the form of religion, tribal, ethnic or sectarian identities. As such, the arguments about repression and lack of legitimacy are accurate only insofar as they exclude segments of the Arab populations that do not have this sense of “patrimonial compliance” (Pitcher et al. 2009). There is therefore, a complex array of social relations and norms that produce the required political stability and social cohesion to keep these systems in place. The ABS data presented in the paper also confirms the important role of religion in MENA more generally.

5.1. The Distributive Model and the Logic of Dissent

Alshalfan (2013) analyses the effectiveness of the distributive state model based on the case of Kuwait, which is generally regarded in the literature as the model example of an Arab Gulf state using oil revenues to provide generous social welfare benefits to its population. As noted elsewhere in the literature, distributive states contrast with the Western model of welfare states in the way they finance welfare services, this being based on rent revenue rather than the extraction of surplus revenue through taxation. Hence, bureaucracies do not develop in such states to become accountable in the delivery of essential public service (Alshalfan 2013). Rather, they serve the state’s primary role as the employer and purveyor of welfare benefits. This type of state subsidises a range of goods and services and also provides essential services such as education, employment and free housing. The adverse effect of this is that states dependent on this mode of finance, such as the Arab Gulf states, are vulnerable to oil revenues and in recent years, they have grown concerned by the welfare dependency of their populations. The distributive welfare approach also means that governments brush over the inequalities within their local populations. For example, merchant families remain the most affluent members of Kuwaiti and other Arab Gulf populations (Alshalfan 2013).

It has been widely argued that Rentier states tend to be weak states because a high dependence on oil revenue hinders the development of accountability mechanisms between state and society that would otherwise develop through a taxation system and corresponding need for democratic representation (Schwarz 2008). On the other hand, these states use social welfare benefits to gain societal acquiescence. Mazaheri (2017) provides an interesting analysis of the Muslim Shi’a population uprisings in the oil-fertile Eastern province of Saudi Arabia to show how marginalised populations in oil-rich economies use rioting and “dissent” (Mazaheri 2017) to access better services such as water and sanitation. Th Arab Spring events also set in motion similar responses by Arab governments who used handouts, cash assistance or increased public sector pay to abate social dissent.

Beyond the Arab Gulf states, analysts also agree that the detrimental effect of oil on the political development of Arab states is felt across the Arab world. This is because oil-rich Gulf states use oil revenues to fund development assistance and aid to lower income Arab countries such as Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan. In turn, non-oil Arab countries have a long history of relying on migrant workers and foreign remittances from their oil-rich neighbours. This feeds into a “rentier mentality” (Beblawi 1990), which is described as a break in the intrinsic link between work and reward. Beblawi (1990) argues that Rentier ethics are in juxtaposition with the ethics of production, and Arab societies have come to expect wealth and resources to be circulated though other mechanisms, such as clientelism and favouritism, due to the loss of the link with economic production.

5.2. Non-State Actors and the Logic of “Right”

The second model covers the role of religious actors in the provision of services, specifically Islamic political movements and welfare organisations. Since most people in the MENA region work in the informal sector (68.6%) and most of this group rely on non-state service provision, this appears to be an important theme in the MENA literature. A literature review by Ismail (2018), for example, found that local service delivery in Egypt was being undermined by a crackdown on religious organisations and civil society groups. Some studies examine how non-state armed groups such as Hezbollah or various groups in Syria have used the delivery of basic services as a means of bolstering their standing with local communities.19 An interesting feature of the region, is that many important non-state political movements, such as the Muslim Brotherhood or Hezbollah, have a regional or transborder dimension (Schlumberger 2010).

Two notable cases in the literature are Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon, who have acquired formal political status in their respective polities (Heger and Jung 2017; Jawad 2009). There are various strands of literature in relation to service provision by religious organisations. Heger and Jung (2017) note that service provision in conflict zones can take a variety of forms: to provide welfare, food, medical services, education, and/or religious services. Qualitative research has shown that social welfare is an important element of the political and social identity of these religious organisations (Jawad 2009; Jawad et al. 2019; Jawad and Eseed 2021) in that they not only provide the local infrastructure of education, health and sanitation services but also help to consolidate community support for the religious movement or organisation that is providing these services and effectively representing the interests of the community in the national polity. In the case of Hezbollah, welfare services are separated between the support given to military personnel and those offered to the wider community as part of a network of charities. The Emdad committee is one such example of a charitable organisation politically affiliated to and staffed by Hezbollah but serving communities in need mainly in the southern suburb of Beirut and in the South of Lebanon, where the majority of the Shi’a population of Lebanon resides (Jawad 2009).

Hamas’ service provision role is also quite well-developed and, similar to Hezbollah’s, took root before the organisation formally launched itself as a political organisation. For example, the grassroots involvement in elections in universities, workplaces and trade unions was often one way in which Hamas developed a support based in the local population. Hamas took on the social welfare role previously covered by the Muslim brotherhood, sometimes also operating out of unofficial community centres that are used both to distribute goods and services but also as party headquarters (Heger and Jung 2017).

According to Heger and Jung (2017), the earlier literature on rebel organisations in conflict zones argued that such groups provided social welfare services when state institutions were absent or insufficient. This in turn helped rebel groups gain power and legitimacy among the populations they supported. More recent work has examined in more depth how the social services provided by religious organisations link with their political activity and claims to power. For example, one set of studies link service provision to particular forms of violence such as suicide bombing, attacks on civilians and lethal attacks (Heger and Jung 2017, p. 1207). Key conclusions that emerge from this literature are that (1) service-providing groups tend to have a larger support base since service provision facilitates recruitment and the legitimacy of the rebel group, especially where the state is perceived as weak or corrupt; (2) involvement in service provision also means that an organisation has a complex structure distinguishing between a range of functions and therefore may have a greater capacity to negotiate in peace deals as well as a greater aptitude to fight; (3) such groups are more likely to be involved in more severe forms of violence and high risk tactics such as suicide attacks or violence against civilians (Heger and Jung 2017, p. 1207).

6. New Lines of Enquiry about MENA Emerging from the Arab Context

This section synthesises the discussion so far by making linkages with the existing literature and proposing possible new lines of enquiry that deserve further research. First, a brief review of the data presented in this paper is worth noting. Service delivery is a key focus of this Special Issue, and it is also a core topic in the social policy literature. Hence this paper has engaged with a social policy perspective by conducting a preliminary review of data on social expenditure and considering levels of citizen satisfaction in relation to social policy areas such as the gap between rich and poor, access to jobs and services, and satisfaction with health and education. Conceptually, the point of departure both in this paper and the Special Issue is that SD and SL are not directly correlated, a relationship which is even more problematic in the MENA region. However, the ABS data also show populations are most concerned about economic and social issues in their countries. The paper has therefore brought to bear qualitative data that proposes two dominant forms of service delivery: one state and one non-state. Both rely on types of political affiliation that are not based on citizen rights but rather on ascribed identity, such as religion or patronage.

An interesting indicator to highlight is the gap between rich and poor, as shown in Figure 7. Satisfaction with this policy area is higher in countries where there are more large social assistance systems, such as Egypt and Kuwait. This raises the question of whether there might be further investigation needed of the social and political context of service delivery processes to better understand the linkages between SD, SL and C. Since concern with jobs and the economic situation are also of key concern, as highlighted earlier, these data may imply that Arab citizens connect their welfare with economic considerations more than with state interventions to improve their lives through services. As such, service delivery may have relatively little impact on state legitimacy in MENA countries, especially when current literature such as on Lebanon (cited above) refers to low expectations of government. The data presented already show that Arab populations are politically active in the formal and informal spheres, but what we know less about is the extent to which this form of political participation has any influence on services such as through citizen voice in local government. As pointed out by Pitcher et al. (2009), we also propose here that deeper qualitative investigation is required to understand whether political forms of participation which enhance social rights and equality may play a role in strengthening state legitimacy and service delivery in MENA. These would need to also account for religious non-state actors who pose a political challenge for the state in many MENA countries, especially where these groups have mobilised against the state and provided services.

Service delivery focuses on the performative functions of the state. Hence, the findings of this paper support a growing body of literature that emphasises the social and political processes underpinning how services are delivered and citizen perceptions of their fairness rather than whether they are simply present or absent (Stel and Ndayiragije 2014).

The social policy perspective applied in this paper to further examine the relationship between SL, SD and C in MENA thus leads to the following key conclusion: it is important to further research Arab citizen perceptions of the role of the state and the extent to which state delivery is considered a fundamental part of this. This is because the ABS data discussed here suggests that finding jobs is a more important concern for Arab citizens at a time when many already take part in formal elections, such as by voting. The qualitative data regarding the two types of models of service delivery in MENA also provides some background context to the social and political processes that are in operation in Arab countries. Where the state provides services as part of clientelist structures, citizen distrust in the state may be muted. Where non-state and especially religious actors provide services, citizens benefiting may already have low expectations of the state or may already be in conflict with state agencies due to having alternative political/religious affiliations. These issues deserve further investigation. In this respect, we acknowledge the inherent limitation in the ABS data, which is that it is not possible to make a direct association between the trends identified in this paper with actual citizen perceptions of state legitimacy in MENA. Further analysis and qualitative research would be required. The paper has, however, made the worthwhile contribution of identifying the key trends that are essential for more rigorous study of SL, SD and C in MENA.

The above argument supports existing research on social contracts in MENA countries that are characterised by an “autocratic bargain”—basic services in exchange for “limited political and civil liberties” (Jawad 2020), with benefits mainly flowing to the urban middle classes, especially those working in the formal sector. These issues are compounded by the high level of dependence on oil revenues, which has led to jobless growth in some states. The private sector plays an important role in health and education provision, and, as such, the connection between state legitimacy and service delivery is already weak. To this end, Loewe et al. (2020) view the Arab uprisings in 2010–2011 as “an expression of discontent with a situation in which governments provided neither political participation nor social benefits, like employment”. Loewe et al. (2020) suggest that improved service provision could be one way to rebuild social contracts in the region, but little detail is provided on this point. They argue that the current challenges facing MENA states are multifaceted, and that MENA states often fail in all three core state functions (protection, participation and provision). This implies that improving provision alone may not be enough, a view that is confirmed in this paper as well by the wider literature on service delivery, state legitimacy and conflict viewed above.

One final issue is how the COVID-19 pandemic is magnifying social inequality and forcing drastic reconfiguration of state social spending across the world, including in MENA. A forthcoming UN-ESCWA report (UN-ESCWA 2021) argues that the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that social protection systems in the Arab region have not been resilient to crisis. This is especially the case for education, health care and water and sanitation systems. COVID-19 has amplified fragilities and inequalities across digital, gender, social and educational lines, especially in regions already affected by conflict. In conflict-affected countries (e.g., Palestine and Syria), COVID-19 responses were led by expanding or building on existing humanitarian relief programmes and platforms rather than on social protection systems, as in other countries. For example, Iraq introduced an Emergency Grant for unemployed people, Palestine added thousands of families to the “National Cash Transfer Programme” and in Syria, unemployed, daily and seasonal workers, self-employed, older persons and persons with disability were allowed to register online for COVID-19 cash support, food and health baskets. According to Daw (2021), conflict-affected countries such as Yemen, Syria and Libya have very low vaccination coverage of their populations since the war effort inevitably disrupts resource flows, adequate function of health services and access to key services such as water and sanitation.

In sum, two key arguments emerge based on the data discussed here: (1) non-state forms of identity (such as religion, tribalism and clientelism) are especially important drivers of service delivery in MENA countries, a feature that helps to explain why the relationship between SD, SL and conflict may be weaker in this region and (2) further analysis of the political and social processes by which citizens form political allegiances and access services is required. This is how a social policy analysis can complement existing research on SD, SL and C. Hence, the paper proposes that it is not just any form of political participation that matters, but one which can expand social welfare among Arab citizens. A key challenge remains, however, in that Arab citizens appear to value access to jobs more than access to services. This raises the issue of whether service delivery is the main determinant of state legitimacy in the first place.

7. Conclusions

Recent findings from the literature on state legitimacy and conflict have found that the link between SL, SD and conflict is non-linear, and that liberal frameworks focused on formal politics are of limited use to understand state legitimacy in MENA. Research on the political marketplace has emphasised the importance of external revenues as well as regional and international interventions in explaining the relationship between SL and conflict, factors that are particularly salient in the MENA context.

In view of the above, the aim of this paper was to re-examine the main literatures and trends in service delivery, expenditure and citizen perceptions in order to understand the MENA context and identify relevant lines of enquiry in relation to the relationship between SL, SD and C. The paper focused on the Arab sub-region and has undertaken two inter-related tasks: (1) it has offered a preliminary explanation of the distinctiveness of the MENA region in light of some of the main findings of the introductory paper by Kivimaki (2021) and (2) it explored the potential of a social policy perspective in explaining the relationship between SD, SL and C.

A broad review of the quantitative data shows that MENA populations are generally unsatisfied with government services and many governments in the region appear to be more effective in delivering security than services. The data also raise questions about the relative importance of social welfare services such as education and health, for although the ABS opinion survey identifies public services as one of the major challenges faced by Arab publics, the brief review of trends of social expenditures across conflict and non-conflict settings in MENA does not show a clear pattern of linkages with conflict. We have also highlighted how informal political participation (through protests) is relatively high in the MENA region compared to other world regions, and what is increasingly clear is that it seems to co-exist with the authoritarian and patrimonial systems that are dominant in the Arab countries.