Abstract

Social contracts and state fragility represent two sides of one coin. The former concept highlights that governments need to deliver three “Ps”—protection, provision, and political participation—to be acceptable for societies, whereas the latter argues that states can fail due to lack of authority (inhibiting protection), capacity (inhibiting provision), or legitimacy. Defunct social contracts often lead to popular unrest. Using empirical evidence from the Middle East and North Africa, we demonstrate how different notions of state fragility lead to different kinds of grievances and how they can be remedied by measures of social protection. Social protection is always a key element of government provision and hence a cornerstone of all social contracts. It can most easily counteract grievances that were triggered by decreasing provision (e.g., after subsidy reforms in Iran and Morocco) but also partially substitute for deficient protection (e.g., by the Palestinian National Authority, in pre-2011 Yemen) or participation (information campaign accompanying Moroccan subsidy cut; participatory set-ups for cash-for-work programmes in Jordan). It can even help maintain a minimum of state–society relations in states defunct in all three Ps (e.g., Yemen). Hence, social protection can be a powerful instrument to reduce state fragility and mend social contracts. Yet, to be effective, it needs to address grievances in an inclusive, rule-based, and non-discriminatory way. In addition, to gain legitimacy, governments should assume responsibility over social protection instead of outsourcing it to foreign donors.

1. Introduction

Throughout history, states and their governments could only emerge (and endure) with at least some consent by society. All governments depend on a minimum degree of legitimacy and, in turn, state legitimacy depends on the existence—and fulfilment—of a social contract on rights and obligations of the state and societal groups towards each other. More concretely, social contracts say that society should recognise a government as legitimate if it satisfies the expectations of citizens in terms of delivering protection (individual and collective security) and provision (of economic and social services) and granting some participation (in political decision-making).

Social protection is typically a key element of social contracts. Rich members of societies wish to have a state that protects their wealth against robbery by the poor—and by strangers—whereas the poor accept such a state only under the condition that the rich pay for it and for its delivery on the protection of citizens and, in addition, share a bit of their income with the poor through social protection schemes. Every now and again, state and society reconsider and, if necessary, renegotiate the deal—and if no agreement is reached, that is, if grievances continue, societal groups start to push, by force, for a new social contract, and conflict arises.

Our article has two aims: First, to explain the link between social contracts and different conditions of state fragility and to propose the concept of the social contract as a further way to systemise the “fragility–grievances–conflict triangle in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)” and beyond, as discussed in the Social Sciences special issue of this title that our article forms part of, and second, to discuss, using empirical evidence from the MENA region, how different notions of state fragility lead to different kinds of grievances and how these can—more or less easily—be remedied by measures of social protection.

Methodologically, we based our analysis on a systematic review of publicly available literature on social contracts and social protection in MENA1 countries, which we have been following and reviewing for the last 25 years. From among all the MENA countries, we selected the most telling country cases in regard to (i) their governments’ ability or failure to deliver the three Ps—protection, provision, and political participation (see also diagram 1 further below)—and (ii) their efforts to reform social protection in different ways. Specifically, we provide evidence from Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen and triangulate them with the results of research on some fragile sub-Saharan African countries (Chad, DR Congo, Mali, Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Uganda).

We proceed as follows: Section 2 presents a non-normative concept of social contracts and links it with the most up-to-date conceptualisations of state fragility, while paying attention to possible triggers of popular grievances. Section 3 elaborates on the development of social contracts in MENA countries since World War II and the respective role of social protection. Section 4 provides examples from outside and inside MENA where social protection has helped (or not) to address signs of state fragility and cures for the most essential deficits in social contracts with regards to protection, provision, and participation. Section 5 concludes the article.

2. Linking Social Contracts, Different Conditions of State Fragility, and Popular Grievances

At a glance, the relationship between social contracts and state fragility might seem self-explanatory: States with a well-functioning social contract are less fragile. Yet, what counts as a well-functioning social contract? That is, what are the criteria to assess whether a social contract contributes to the stability of a state or, on the contrary, makes it more fragile? In this section, we dissect different elements of social contracts (Loewe et al. 2021) and state fragility (Grävingholt et al. 2015) and relate them to each other. By doing so, we also point to different categories of popular grievances.

The term “social contract” has a long history of thought and, across different traditions, usually carries a positive connotation. In Europe, liberal state philosophers Hugo Grotius (1625), Thomas Hobbes ([1651] 1985), John Locke ([1689] 2003), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762) used it to contrast a state-controlled setting that includes property rights, some degree of security, and possibly distributive justice with the “natural state of anarchy”. In this way, the existence of a social contract is something positive in itself. The social contract is, however, not a purely European idea. In the MENA region, contractarian thought goes back to the Qur’ān itself, which establishes a contract (caqd) between God and the believers who submit to the former, thereby defining rights and duties for the muslimīn and their leader, the imām. These duties explicitly include the responsibility of the wealthy to care about the poor.2 Similarly, 15th-century thinker Ibn Khaldun proposed a reciprocal concept of communal solidarity between individuals, the so-called casabīyya, which falls under the patronage of a šarīca-abiding ruler (Krieg 2017).

Only more recently, a debate3 has evolved differentiating “good” and “bad” social contracts, implying that not the mere existence—which may be better than anarchy but can be taken for granted today by the large majority of countries—but the specific design of a social contract needs to be taken into account. The crucial point is the question of whether there are objective criteria allowing the judgment of when a social contract is good (or at least better than others). If the answer is yes, it is possible to make proclamations on which reforms are due to “improve” social contracts, as some authors do. Quite often, however, such proclamations have been in line with a quite liberal agenda of Western democracy, human rights, and free market economy (e.g., Devarajan and Mottaghi 2015; Larbi 2016; Razzaz 2013; Shafik 2021; World Bank 2004).

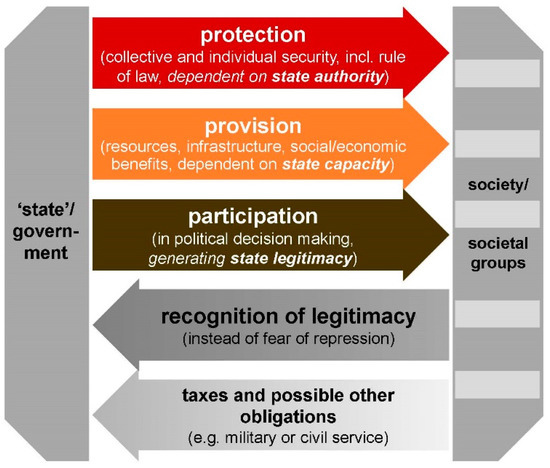

Social contracts can be conceptualised in a purely analytical way as “the entirety of explicit or implicit agreements between all relevant societal groups and the sovereign (i.e., the government or any other actor in power), defining their rights and obligations towards each other” (Loewe et al. 2021). The possible obligations of the government can be categorised by three Ps (Figure 1). As will be illustrated below, the state is supposed to deliver three Ps corresponding to the three core functions of a state as conceptualised by comparative politics literature: authority, capacity, and legitimacy (Grävingholt et al. 2015):

Figure 1.

Deliverables in a social contract. Source: Loewe et al. (2019). Available online: https://www.die-gdi.de/briefing-paper/article/the-social-contract-an-analytical-tool-for-countries-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-mena-and-beyond/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Protection, including collective security against external threats and individual security against possible damage caused by criminal or politically motivated attacks;

- Provision of social and economic services such as access to land ware and other resources, infrastructure education, health, social protection, a good business climate, government procurement, and others; and

- Participation, that is, granting citizens a voice in political decision-making at different levels.

In exchange, citizens are expected to

- accept the ruling authority of the government; and

- pay taxes or fulfil any other obligations (e.g., military service) in accordance with their ability to do so.

These deliverables vary substantially across countries (e.g., OECD—Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2009) subject to an iterative process where society has expectations of the state and the government makes an offer of what it is willing (and able) to give. Whether society accepts the offer depends on the readiness and ability of citizens to claim for anything better. The shape of social contracts depends thus on the relative strength of society and the government. To a certain degree, governments can also defend their rule and insist on their preferred social contract by the use of repression. Yet, in the long run, they hardly ever succeed without at least some legitimacy emanating from a social contract.

The fact that societal preferences (i.e., values, norms, or expectations) play such an important role explains why assessing the quality of social contracts by objective criteria is hardly feasible. Outsiders typically have only limited knowledge on these preferences because they may be quite different from those of people elsewhere. The Universal Human Rights Declaration and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda certainly establish some generally accepted criteria, yet people in different countries would certainly disagree on how to prioritise the numerous, sometimes conflicting goals mentioned in the agendas.

Therefore, we suggest assessing social contracts only by a system-immanent logic: their functionality. Their key purpose is to improve the predictability of outcomes in iterated state–society interactions and, hence, to relieve the contracting parties of renegotiating their mutual obligations time after time. From this point of view, social contracts are good if they are sustainable, i.e., if their conditions are acceptable to all contracting parties over a longer period (Muggah et al. 2012). As long as governments provide all three Ps mentioned above, society is likely to fulfil its deliverables, too, and social contracts are likely to be stable. This does not mean that they do not change at all. Quite the contrary: They often evolve quite considerably but smoothly with the effect that it is sometimes difficult to say whether a social contract has changed substantially or been replaced by a new one. In particular, the third P—participation—guarantees that the contracting parties renegotiate the social contract regularly and adapt it unanimously.

Hence, only the contracting parties themselves can say whether their social contract is good. The flaw of such an approach is that we realise that a social contract is dysfunctional only when people revolt against it.

This is where the concept of state fragility comes in. If a government fails to deliver one or more of the three Ps sufficiently, that deficiency likely sparks popular grievances and political instability known as state fragility (Grävingholt et al. 2015; Kivimäki 2021).4 State fragility looks rather different depending on which deliverable is missing:

- Some governments fail in the delivery of protection (most often with respect to the individual security of citizens) because of a lack of authority (examples include El Salvador and Sri Lanka but no MENA countries);

- Some governments fail in the delivery of provision (e.g., infrastructure, laws to safeguard fair competition on markets or social protection) because of a lack of capacity (examples include Zambia and Burkina Faso but no MENA countries);

- Some governments fail in the delivery of participation (which holds for China but also for most MENA countries, such as Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia); and

- Some governments fail in the delivery of all three Ps. They lack authority, capacity, and legitimacy (examples in MENA are Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen). As a result, the countries suffer from frequent armed conflicts or even civil wars.

In all four cases, the populace’s grievances can be considerable. Yet, the first three categories of states still have social contracts, even though they may be truncated and hence unstable—and become ever more unstable with any cutbacks in the remaining two Ps. Countries in the fourth category, failing in all three deliverables, do not have a nationwide social contract any more but at utmost fragmented, sometimes competing, local social contracts, maintained by their former government or other actors such as we currently see in Syria, Yemen, and Libya (Muggah et al. 2012).

All forms of state fragility can give rise to serious popular grievances. If we take a closer look at how grievances arise and to what degree they affect people, we find that some are more profound and urgent than others. Maslow’s by now famous pyramid chart presents such a hierarchy of needs. Only if individuals’ most basic physiological needs (food, water, warmth, rest) and safety needs are satisfied will they be motivated to seek fulfilment of their higher-order psychological and self-fulfilment needs (Maslow 1943). Since 1990, the UNDP’s Human Development Index, measuring and comparing gross national income per capita, educational attainment, and life expectancy between all countries, has provided a standardised measure of the degree to which these basic needs or developmental grievances are being met (Kivimäki 2021).

From this angle, deficiencies in social contracts pertaining to one of the first two Ps, protection or provision, may be more urgent and more likely lead to protests—whereas citizens can grudgingly put up with a lack of participation, at least for some time, they cannot survive without basic nutrition, hygiene, and shelter. Thus, governments failing in the delivery of protection or provision may find themselves at risk of major popular unrest and actual breakdown sooner than governments not granting participation, whose chronic lack of legitimacy destabilises them in the long run.

In any case, social contracts differ, of course, not only in their substance but also in their scope (the contracting sides and their respective spatial range of rule or influence) and temporal dimension (beginning, duration, and end) (Loewe et al. 2021).

As regards the scope, it is important to consider that neither government nor society are homogeneous actors. First, both the government and society can be internally quite divided in terms of interest.5 Second, the government is not necessarily the executive of a nation state. Instead, it can be any body enjoying executive force in a territory, even one with shifting boundaries. This includes supra-national powers such as the European Union just as much as transnational powers (e.g., the so-called Islamic State that controlled large parts of Iraq and Syria for several years, see Revkin and Ahram (2020)) and sub-national units of power (such as the organised confessional communities (ţawā’if) in Lebanon, Kurdish minorities in Iraq and Syria, and tribal actors, for instance in Yemen) (see Ayoob 1995). All of these can establish their own, sometimes overlapping6 social contracts. Such competition over social contracts can, in turn, influence citizens’ priorities so that participation gains relative importance vis-à-vis the other 2 Ps.

Finally, in their temporal dimension, social contracts differ with regards to the when and how long: How long are they respected and when do contracting parties demand renegotiation or decide to cancel a social contract in hope of striking a better deal?

3. The Erosion of the Provisionist Social Contracts in the MENA Region after 1985

When MENA countries achieved full independence after World War II, they established strikingly similar “populist-authoritarian social contracts” (Hinnebusch 2020). Almost all had powerful states with much authority to deliver protection, in terms of both individual and collective security. In addition, the republics started delivering provision, the second P, quite extensively in order to implement their ideologically motivated plans of transforming societies but also to legitimise their rule. At the same time, they were not (yet) ready to allow for the third P, meaningful political participation. The region’s monarchies followed this strategy somewhat later even though they never had a plan to transform societies. They were even less ready to allow for political participation but still felt the need to legitimise their rule at least in material terms, i.e., extended provision—in particular because their citizens started to compare the performance of governments such as those of the Syrian republic and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan or the Algerian republic and the Moroccan monarchy (Loewe et al. 2021). As a consequence, authoritarianism has long been much more persistent and wide-spread in MENA than in any other world region (with the possible exception of Central Asia), whereas spending on social protection and other elements of provision have always been at least on average levels (Loewe 2010b).

Improvements in social protection for all groups of society were at the core of governments’ efforts to expand their delivery on provision. During the 1950s and 1960s, MENA governments established energy and food subsidies, social housing schemes, and free public health care systems in order to reduce the costs of essential commodities for people with low income as well as others. They established social assistance programmes to support households with particularly low incomes, especially if they had no male members of working age. Somewhat later, MENA governments also extended the coverage of public social insurance schemes—most often inherited from former colonial powers—to additional groups of the population in order to prevent them from falling into poverty because of illness, work-disability, old age, unemployment, or the death of the main breadwinner in the family. They created thousands of jobs in the public sector to help people with low- and middle-income backgrounds climb up the societal ladder (and to co-opt them). Finally, they redistributed land and property owned by large landlords to landless workers and nationalised companies, in particular in finance and heavy industry, in order to transform societies towards better social justice (Loewe and Jawad 2018).

State capacity to deliver such provision was based on the fact that all MENA countries benefitted, until the mid-1980s, from substantial external rent income. Some countries had sources of direct rent income (e.g., from natural resources like oil, gas, gold or phosphate, remittances, and other sources such as the Suez Canal rents in the case of Egypt), whereas others befitted more indirectly (from politically motivated budget transfers by the Gulf countries or as a consequence of Cold War alliances). During the 1990s, at the latest, this very capacity started to weaken, however, because all external incomes declined, most significantly because of a drop in oil price and the end of the bipolar world order. In addition, governments distributed their provision over an ever-growing population, reducing the per-capita benefit bit by bit (Hinnebusch 2020).

All MENA governments therefore decided at some point in time to reduce provision and focus it more on strategically important societal groups: the economic and political elite and the politically active urban middle classes. Concretely, they saved in their spending on social assistance, public health and education programmes, and large-scale provision of public-sector jobs. Energy subsidies, social insurance, and small enterprise promotion programmes—which all benefit the urban middle class substantially more than the poor—were also expanded (Loewe and Jawad 2018).

One could say that governments altered the stipulations of the social contracts, thereby discriminating between the terms for more and less powerful groups. They intensified their care for societal groups such as entrepreneurs, the intelligentsia, and organised, formally employed workers—groups who fully enjoy all three options of Hirschman’s exit/voice/loyalty schema (Hirschman 1970). Meanwhile, they saved on their spending on societal groups who largely lack both “voice” and “exit” because of a lack of resources and organisational capacities.

We argue that the uprisings dubbed the “Arab Spring,” which rocked most MENA countries from 2010 onwards—first Tunisia; then Egypt; then Bahrain, Libya, Syria, and Yemen; and some years later Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Sudan—should be interpreted as a grievance about their deficient or “unsocial” social contracts (El-Haddad 2020). Protesters pointed to the fact that governments continued to deny citizens any tangible participation, the third P, while cutting down on the delivery and fairness of provision, the second P.

It is difficult to say which grievances pushed Arab people onto the streets in protest. Some authors see material factors—inappropriateness of provision—as the main reason (e.g., Devarajan and Mottaghi 2015; Luciani 2016; Winckler 2013), whereas others emphasise the lack of political participation (e.g., Kivimäki 2021; Barakat and Fakih 2021; Moghadam 2013; Saidin 2018). Most likely, it was a combination of factors—those who went to the streets criticised governments’ delivery of participation and provision as well as the way how state representatives treated citizens without respect or dignity. In Egypt, they all shouted for “Bread! Freedom! Social justice!” yet different groups of protesters (young liberal intelligentsia, Muslim Brothers, trade unions, etc.) likely each focussed on a different claim.

In the aftermath of the 2011 uprisings, and in line with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we do know that the citizens of Egypt, Lebanon, and Tunisia today have a clear preference for provision. In a representative survey conducted on behalf of the German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), more than 1000 nationals in each country were asked to select the two most important duties of the state from a list of six options, where two options represented each of the three Ps.7 A total of 89% selected at least one that represented provision (93% of Tunisians, 86% of Lebanese nationals, 85% of Egyptians), whereas just 54% selected one that represented protection (63% of Egyptians, 52% of Tunisians, 49% of Lebanese nationals) and as little as 19% opted for an aspect of participation (28% of Lebanese nationals, 14% of Tunisians, 13% of Egyptians) (Loewe and Albrecht 2021).

However, where a trans- or subnational group questions the scope and general characteristics of a social contract, participation gains relative importance. Such is the case if radical and violent extremists mobilise their followers (e.g., Alkhayer 2021).

Although after the uprisings, the social contracts of MENA countries developed in quite different directions, it is fair to say that none of them are fully stable, that is, sufficiently address both the government’s and society’s demands for a long-term new social contract:

- Tunisia, commonly regarded as the only successful case of the Arab uprisings, has continued to strengthen the third P, participation—at least until summer 2021—yet reforms in terms of reprioritising the delivery of provision have stagnated so far (El-Haddad 2020; Mahmoud and Súilleabháin 2020). Economic difficulties have marred political achievements to a great degree (Chomiak 2021; Gallien and Werenfels 2019), thus leading to renewed protests.

- Jordan, Morocco, Iran, and the Gulf monarchies seem to be trying to preserve as much as possible of their old social contracts (Kinninmont 2017; Nazer 2005; Luciani 2017; Thompson 2018; Vidican Auktor and Loewe 2021). However, it is not yet clear whether “old” means the original populist–patrimonial social contracts of the 1950s–1970s, the dismantled unsocial social contracts of the 2000s, or a mix of both, such as in Jordan’s “tribal-state compact” (Yom 2020). In any case, protection ranges high on the agenda of these countries, whereas meaningful participation plays no role at all. The question is thus mainly what kind of provision the state is going to deliver in the future and to whom.

- Egypt has moved towards a protectionist contract where provision plays almost as little a role for government legitimisation as participation (Rutherford 2018). President Sisi portrays himself as the saviour of the country and the only alternative to the instability and chaos that countries such as Syria, Libya, and Yemen are witnessing and any other relevant political force, mainly the Muslim Brothers, would bring to Egypt as well. In this dictum, the delivery of protection is enough for a government to legitimise itself with the effect that the well-being of low-income households in Egypt continues to deteriorate (Ibrahim 2020; Sobhy 2021).

- Syria, Yemen, and Libya have descended into civil wars. Their governments have lost control over large parts of the territory with the effect that there is no nation-wide social contract and large parts of the population are not enjoying any of the three Ps anymore. In addition, the relations between the different (regional, religious, ethnic, socioeconomic) parts of society—which are the very important horizontal elements of any social contract—have been poisoned by mistrust and need to be restored in order to rebuild a new social contract (Furness and Trautner 2020). Thus, a new government needs to arbitrate in a fair manner between the former conflicting parties to promote its legitimacy. Social reconstruction will be more important than reconstruction of destroyed physical infrastructure (World Bank 2020).

These developments show that most MENA governments face a dilemma: They are not ready to grant more participation but are also unable to return to former provision levels. The grievances of citizens are thus growing, and the unsatisfactory management of the COVID-19-pandemic—both in terms of provision (health care and poorly targeted social assistance) and participation (citizen information and consultation) (Abouzzohour 2021; Krafft et al. 2021; Younis et al. 2021)—tends to exacerbate the trend. Widespread dissent from the existing social contracts may lead to increasing numbers of people choosing the “exit” option (Hirschman 1970) and trying to “enter” another social contract by migrating to Europe. In the long term, however, many more might choose the “voice” option again—this time, however, perhaps less peacefully than in 2011. Additional MENA countries might then implode and millions more would flee from their home countries.

All actors—governments, citizens, and the outside world—therefore have an interest in the reinforcement of the social contracts in the MENA region. To pre-empt revolt and brain drain, governments must take a first step here, and—given the fact that the existing autocratic leaders will not be willing to allow much participation—they should at least target measures that improve the well-being and security of citizens (provision and protection).

Better social protection is an ideal instrument in this regard, as it is an effective kit to improve the relations between state and society. Of course, lack of participation is by far the main flaw of MENA social contracts, but better provision could still act as a remedy because MENA citizens may now see their basic needs as endangered, too. In particular, the growing relative deprivation of citizens in MENA countries—defined as “a situation where there is a gap between the expected and observed receipt of welfare, income, wealth, political power, or something else” (Kivimäki 2021)—requires a stronger focus on social protection.

4. Social Protection as a Cornerstone in Social Contracts

Social protection may look like one out of many items of provision in social contracts today. This impression is due to the fact that modern states provide a large array of services to citizens: infrastructure, enterprise development, market information, public education and training, health services, labour-market policies, and many more. Most of these services, however, fulfil citizens’ higher-order and not their most basic physiological needs at the base of Maslow’s pyramid. Thus, the most fundamental government service has always been social protection, which is the “entirety of policies and programmes that protect people against poverty and risks to their livelihoods and well-being” (Loewe and Schüring 2021). Social protection thus includes measures that (i) protect people with low income against the most serious manifestations of poverty, (ii) prevent people from significant declines in well-being caused by risks, (iii) promote people with low incomes to escape from poverty, or (iv) transform societies towards better social equality, inclusion, social mobility, and sustainable livelihoods (Devereux and Sabbates-Wheeler 2004; Guhan 1994; Loewe and Schüring 2021).

The oldest and most rudimentary social contracts may not have been acceptable to low-income parts of the population if they had not provided for social protection: some redistribution of harvests, some poverty relief, some sharing of public goods, some mutual support in case of adverse events such as work-disability or death of the main breadwinner of a family. For more affluent households, of course, protection has always been more important: security from external threats (attacks from outside), internal threats (theft and violence), and political/ legal threats (disappropriation of the rich by the government, the judiciary, or armed gangs) (Harari 2011).

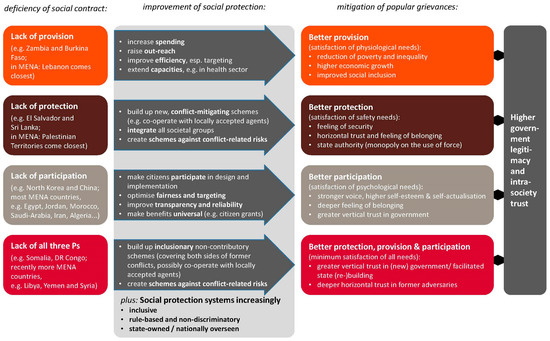

Effective social protection is thus a powerful instrument for strengthening the acceptability of existing as well as for rebuilding new social contracts. Of course, it can be particularly helpful for the repair of social contracts that suffer from poor state performance in the domain of provision. Yet, social protection can also support social contracts suffering from deficits in terms of protection or participation—where it helps to fulfil citizens’ higher-order needs—or all three Ps, as Figure 2 illustrates and will be explained next.

Figure 2.

Social protection as a remedy of popular grievances within deficient social contracts. Source: authors.

4.1. States Failing on the Delivery of Provision

At first glance, it appears trivial to state that social protection can contribute effectively to the repair of social contracts suffering from weak government performance in provision. Social protection is at the core of provision, addressing citizens’ most basic needs, and that is the reason why we can expect any increase in social protection spending to make citizens more satisfied with the social contract that exists in their country and more willing to accept the rule of their respective government. Several empirical studies have, in fact, found evidence of a negative correlation between social protection spending and grievances of citizens (Burgoon 2006; Ogharanduku 2017; Raavad 2013; Taydas and Peksen 2012; Valli et al. 2019). Conditional cash transfer schemes can even contribute significantly to the trust of households in political leaders, as Evans et al. (2019) showed for Tanzania. This can be due to three effects: first, citizens’ appreciation of government commitment to social welfare; and second, a reduction in poverty and inequality; and third, social protection spending that can foster growth and thereby reduce the opportunity costs of being part of an armed group (Babajanian 2012; Burchi et al. 2020; Koehler 2021; Mallet and Slater 2013; Reeg 2017; van Ginneken 2005).

Likewise, social protection has the potential to strengthen the trust between individual citizens, either within the same societal groups or from different ones. Therefore, it can solidify the horizontal intra-societal dimension of social contracts. Several studies have confirmed this assumption, showing that social insurance and assistance schemes can contribute to horizontal trust (Adato 2000; Pavanello et al. 2016) and that social protection schemes have a positive impact on the willingness of people to co-operate with others (Attanasio et al. 2009, 2015; FAO 2014).

However, these positive effects should not be taken for granted, as they are conditional on proper programme design and implementation. In particular, lack of fairness or transparency in benefit targeting can create feelings of resentment, enfold negative effects on both state–society and intra-societal trust, or even spark social conflict (Brigg 2008; Molyneux et al. 2016). Especially problematic are social protection programmes that differentiate substantially between different groups of society. For instance, social insurance programmes in many MENA countries distinguish by groups of employees, and often the benefits for high-income groups are more generous than those for the poor. Tunisia has 13 different social health insurance schemes, thereby mirroring and intensifying the existing stratification of society (Loewe 2019). Lastly, social protection benefits need to effectively address the needs of beneficiaries and be acceptable in socio-cultural terms (Mallet and Slater 2013). Several empirical studies confirm that if social protection programmes are not designed in an inclusive and needs-oriented way, they cannot effectively counteract societal grievances but can even have negative—or at least mixed—effects on societal perceptions of government (Adato 2000; Adato and Roopnaraine 2004; Aytaç 2014; Browne 2013; Bruhn 1996; Carpenter et al. 2012; Guo 2009; Idris 2016).

In addition, social protection programmes can only contribute to government legitimacy if they have been set up by the state (Gehrke and Hartwig 2018; Zepeda and Alarcón 2010). Many cash-for-work programmes in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and Iraq, in contrast, are not only fully funded but also initiated and designed by foreign donor agencies and hence foster appreciation for those agencies rather than national governments (Bastagli and Samuels forthcoming; Loewe et al. 2020; Zintl and Loewe forthcoming). Likewise, social protection programmes can also undermine the reputation and legitimacy of the government if they are organised by non-state actors—especially if those actors are competing or even opposing the ruling government. The Muslim Brothers in Egypt, for example, ran quite effective health, social aid, and education programmes during the 1990s and 2000s, which probably contributed to the popularity of the Muslim Brothers just as much as their religious teaching and preaching (Batley and Mcloughlin 2010; El-Hedeny 2021).

There are manifold examples of poor implementation and targeting in the MENA region, which help explain why many social policies of governments do not sufficiently achieve positive effects on social contracts. MENA countries spend much more on social protection, health, and education than countries in other world regions, with the exception of Central Asia and the Caucasus (and, of course, OECD countries), so hardly any of them are an example for the category of states failing mainly in terms of provision—these are more likely to be found in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Liberia, Angola, Kenya) and South Asia (e.g., Pakistan, Nepal). It is rather the inefficiency and ill-targeting of many programmes to above-average income earners that provide ample evidence of why costly provision has not led to meaningful legitimacy.

- Commodity subsidies on energy, food, and water account for a high share of social policy spending in most MENA countries even though they primarily help the rich and not the poor. Many low-income earners cannot afford to purchase large amounts of subsidised commodities, even at the reduced prices (Loewe 2019). They own no cars or central heating (and hence do not buy petrol or heating oil), live in smaller homes than the rich, and have no swimming pools and often no showers (and hence consume less electricity and water). In 2010, MENA countries spent on average 6% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on subsidies, but the effects on poverty and inequality rates were negligible.8 Since then, most MENA countries have reduced subsidies but still spend substantial sums on them (Vidican Auktor and Loewe 2021).

- Direct social assistance schemes suffer from substantial administration costs—accounting for up to 86% of their total budgets (Loewe 2010a)—and from targeting errors as well. Hardly any of those programmes reach out to more than a third of the households belonging to the poorest income quintile of the population, whereas a majority of the beneficiaries (58% in Jordan, 60% in Egypt, 68% in Iraq) are not effectively poor. Therefore, these programmes reduce national poverty head-count rates by just 4% on average and the GINI coefficient by a mere one percentage point (Silva et al. 2012).

- Health costs and benefits are also unequally distributed across income groups. Most MENA governments allocate substantial shares of GDP on health (3% on average) but private households still pay large sums out of pocket—in 2017, on average 34% of all national health care costs.9 Low-income people thus often have difficulties accessing adequate health care.10 Differences in health care utilisation and achievement become obvious when comparing figures for citizens belonging to the lowest and the highest wealth quintile—for instance, under-5 mortality in Egypt (42 versus 19%), babies born in a health care facility in Sudan (9 versus 71%), 2-year-old children vaccinated against measles in Iraq (58 versus 88%), or professional medical attention to children under 5 with acute respiratory infections in Sudan (27 versus 63%) (Loewe forthcoming).

Shortcomings in social protection often correlate with generally poor government delivery of provision. Where state capacity cannot guarantee basic public infrastructure and services, economic crises deepen, popular grievances are on the rise, and more people rely on social protection. For instance, Lebanese authorities proved unable to provide sufficient energy, road infrastructure, and functioning water and sewage systems (Garrote Sanchez 2018), which was exacerbated by an acute banking and currency crisis and the Beirut harbour blasts in 2020; poverty levels in Lebanon are now rising.

As a result, the citizens of most MENA countries are dissatisfied with the current performance of their governments in terms of provision, the second P of social contracts—even though most MENA governments are still investing substantially in health, education, and social protection policies and perform much worse in respect to the third P, political participation. In a recent survey, large shares of interviewees said that they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the public health system in their country (27% in Egypt, 61% in Lebanon, and 69% in Tunisia), the education system (36%, 39%, and 73%), the public social protection system (23%, 59%, and 68%), and the government’s performance in fighting poverty and inequality (35%, 83%, and 85%) (Loewe and Albrecht 2021).11

Divergent experiences with subsidy reforms in Iran and Morocco in recent years demonstrate possibly sensitive points when renegotiating service provision within social contracts. Iran’s subsidy reforms show how MENA governments could improve their performance in terms of provision, even though these positive effects did not endure for long. When the Iranian government decided to reduce energy subsidy spending in 2010, it realised that it lacked the microdata needed to compensate low- and medium-income earners with targeted social assistance. Instead, it introduced payments to all Iranians, marketing this step as an expression of citizens’ rights rather than government paternalism (Vidican Auktor and Loewe 2021). Of course, the stabilisation of the political order may in fact have been the main motive for the reforms. Unfortunately, there are no data on people’s satisfaction with the new scheme, but figures suggest that it did indeed reduce poverty and inequality. The share of households living below the international poverty line of USD 4 in PPP went down from 23% in 2009 to 11% in 2013 (Salehi-Isfahani et al. 2015), and food consumption increased by 8% per year despite significant food price increases (IMF 2014). However, by 2020, large parts of these positive effects were rendered ineffective by inflation. Some observers hypothesised that the inflationary pressures have been caused by the generous cash transfer scheme itself, but more likely the main reason was renewed international sanctions leading to a steep depreciation of the Iranian currency (Mostafavi-Dehzooei et al. 2020).

Morocco provides an example for subsidy reforms with mixed effects, showing the government’s will to cushion negative effects onto citizens who were dissatisfied with the reforms. Morocco decided in 2012 to reduce most subsidies until 2021 and to compensate low-income households by extending the outreach of two social policy schemes: Tayssir (“facilitation”), a targeted direct cash transfer programme, raised the number of its beneficiaries from 1 to 7% of the population between 2009 and 2014, and RAMED, the Régime d’Assistance Médicale pour les Économiquement Démunis, raised the overall coverage of social protection against health risks from 23% of the total population in 2012 to 63% in 2018 (MMoH 2018). It offers free membership in Morocco’s social health insurance scheme to households below the national poverty line and at generously subsidised contribution rates to households with an income only little above the poverty line (Machado et al. 2018). Nevertheless, however good the intentions of the Moroccan government may have been, the satisfaction of citizens with the health care system decreased during the reforms. In the 2006 Arab Barometer survey, 64% of Moroccan respondents found government efforts to improve basic health care services bad or very bad, but the share of people who were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied was even higher (80%) in the poll round of 2018 (Arab Barometer 2021). This finding alleges that Moroccans consider that the opening of a health system for large additional population groups does not automatically improve health care provision. Without the allocation of additional funds to the health system to raise the quantity and quality of its services, not even the newly covered population groups benefit substantially from extended access to health care provision.

Yemen provides perhaps the most telling example within the MENA region for government failure in provision. Since its reunification in 1990, the country has been suffering continuously from competing claims on government authority (independence movements in the former South; Houthis in the far North; tribes cooperating with Islamist factions). When public protests in 2011 in the capital Sanaa called for more effective measures against corruption, poverty, and inequality, the police tried first to clamp down on them. Due to international pressure, president Ali Abdallah Saleh stepped down and the transitional government of national unity under former vice-president Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi organised a national dialogue on conflict settlement and state reform. Yemen enjoyed a moment of relatively high participation even though the transitional government was not elected and the dialogue was not sufficiently connected to the local level. However, the attempt to negotiate a new social contract failed, and this was due to unequal provision. The old political elite misused state structures and government programmes for the delivery of provision mainly to their own clientele rather than the entire population. Social protection programmes focussed thus on specific regions and socio-economic groups. As a result, opposition parties withdrew one after the other from the national dialogue process. The country descended quickly into a civil war that has lasted until today, pushing Yemen to the last ranks globally in terms of human development and state fragility (McCandless forthcoming).

4.2. States Failing on the Delivery of Protection

Social protection can also help to stabilise or even repair social contracts that suffer mainly from the government’s capacity to deliver protection. At first glance, this may be surprising: Why should social protection, which is first and foremost an element of provision, also cure deficits in protection and help meet citizens’ security needs?

A first answer is that the three Ps are to some degree—depending on the country—imperfect substitutes. Governments that suffer from low legitimacy because of failure in the delivery of protection or participation can still improve their reputation somewhat by expanding their delivery on provision. Admittedly, they may have to do twice as much as governments performing at least moderately with regards to all three Ps.

Second, social protection, as the term itself says, also has an important protection function. It can be crucial for the individual security of people who, for lack of any income source over a long period of time, risk starvation. Other typical instruments of provision, such as health services or access to improved water, have a similar protection function. This second function is sometimes overlooked as other social protection instruments cover shocks such as unemployment or work-disability, which are less likely to threaten life as such.

Third, the need for social protection is much higher where governments fail in delivering sufficient protection. Here, people are much more likely than in other countries to be killed or injured, lose their possessions (house, savings, machinery, cattle, etc.), get dispelled, or lose their income source. Social protection includes measures to prevent such events or help people mitigate or at least cope with the shocks. Distinctive social protection instruments can economically support surviving family members; provide medical treatment to the injured; compensate families who lost their homes, savings, machinery, or cattle; and provide new jobs and income to those who lost their income source (Cherrier 2021). Therefore, social protection can break a vicious circle that exists between vulnerability to threats and different forms of poverty (Ovadiya et al. 2015). In other words, effective social protection systems render communities more resilient against external shocks and disasters, which are less likely to precipitate a crisis (Levine and Sharp 2015).

At the same time, public social protection programmes can restore the acceptability of the government in power, improve people’s trust in it, strengthen their feeling of belonging, and thereby contribute to the rebuilding of the social contract between the government and the citizens (De Regt et al. 2013). Nobody relies on or believes in a state that fails to deliver at least on the protection of citizens. Citizens ask themselves why they should accept such a state, let alone defend a government that is apparently unable to safeguard even the sheer existence of people. If, however, the same government starts efforts to provide social protection against at least some of the effects of life-cycle, economic, political, or societal risks, citizens may acknowledge the goodwill of the government and appreciate that it is still better to have at least some form of government. Some may even stop opposing the government and perhaps support it, understanding that it could deliver services much better if it were better supported by society.

Unfortunately, there is hardly any empirical evidence on the effects of social protection in countries suffering mainly from limited delivery of protection by the state—other than the fact that in such low-protection contexts the delivery of provision is limited as well. Ovadiya et al. (2015) found that low-authority countries most often (i) have social transfers rather than contributory forms of social protection, (ii) suffer from low coverage/high leakage in their social protection schemes, and (iii) struggle with inefficient social protection scheme administration.

Empirical evidence on the issue is particularly rare in the MENA region—which is the reason why we first present some findings from sub-Saharan Africa:

- The results of a DIE research project conducted in 2015–2016 on cash transfer schemes in five fragile countries (Sierra Leone, Chad, DR Congo, Uganda, and Somalia) confirm that lack of state authority constitutes a challenge for the construction of efficient social protection schemes just as much as lack of state capacity. In Uganda, outbreaks of violence repeatedly challenged the operations of the cash transfer scheme under research, and in Chad, the state had to make additional efforts to safeguard security during the pay-out of benefits (Strupat et al. 2018). In Somalia, cash transfer projects co-operated therefore with local leaders and hawala agents (European Commission 2019).

- At the same time, the project found that social protection schemes have some, if limited, potential to strengthen state authority and thereby contribute to the delivery of protection. In Chad in particular, cash transfers have helped to reduce tensions between different societal groups and thereby have strengthened vertical trust in the government (ibid.).

- The government of Mali concentrated its efforts on building up a national cash transfer scheme in the southern part of the country, where it enjoyed higher authority. International non-governmental organisations (NGOs) therefore decided to set up local cash transfer schemes in the norther pat of the country. Over time, they adjusted the benefits and targeting criteria to those applied by the government in the South, resulting in the emergence of an effectively uniform, nation-wide programme (European Commission 2019).

None of the MENA countries are a prime example of the category of states that fail mainly in terms of protection. Several MENA states are affected by armed opposition or even civil war. The governments of Syria, Yemen, and Libya in particular are questioned in terms of their authority and cannot provide full protection to their citizens, but they fail with regard to the other two Ps as well. They thus belong to the fourth category of failed states discussed further below. Only the governments of Iraq, the Palestinian Territories, and Yemen before 2011 have perhaps less authority than capacity and fail therefore in terms of protection more than the governments of other MENA countries.

The Palestinian Territories are a particularly interesting case in this regard, as its government, the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), falls short in terms of authority mainly because of its lack of sovereignty and dependence on Israeli control. Large parts of its budget are financed by donor aid (30%), lending (7%), and the transfer of import duties that Israel collects on behalf of the PA. (More than 80% of Palestinian exports are to Israel and almost all the rest passes through Israel.) This triple dependency causes regular severe liquidity problems for the PNA, which has not yet been able to deliver considerably on provision: Recently, it spent about 16% of GDP on public employment, 5% on education, 5% on the public health system, 3% on public pensions, 2% on energy subsidies, and 1% on a large array of direct social transfer programmes (World Bank 2016). One of the latter, the West Bank and Gaza Cash Transfer Programme, has been built up only recently and is perhaps one of the most efficient ones of its kind in the MENA region, as it uses a sophisticated management information system (Ovadiya et al. 2015). It reaches out to more than half of the bottom income quintile of the population (14% of the entire population) and has reduced absolute poverty incidence by about 17 percentage points and income inequality as measured by the GINI coefficient by almost 8 percentage points, which is all far above regional averages (Silva et al. 2012). So far, the PNA has resisted all the numerous claims voiced by the international donor community to reduce social protection spending in order to consolidate its budget. The PNA is well aware that its acceptance by citizens depends highly on the delivery of provision in a context where its delivery on protection (economic, human, and collective security) is imperfect.

Another telling case is Yemen before 2011, where the government was also failing predominantly in the delivery of participation but also in terms of protection. It had lost authority in large parts of the country: The South and the far North were under the control of secessionist armies, and other regions were threatened by Islamist gangs and commercial kidnappers. However, the government used polarising identity politics and the provision of social protection to regain legitimacy from larger parts of the population. It increased energy and food subsidy spending to more than 15% of GDP for some years—which is, to our knowledge, more than any other country has ever spent on it. In addition, Yemen’s government paid 1.3% for public health, 0.5% for public pensions, and at least 0.4% for direct social transfers (including, among others, school meals, social aid, and public works programmes) (Loewe 2019). In the end, social protection was the last channel for the government to demonstrate to Yemenis in some regions that it was still in place.

4.3. States Failing on the Delivery of Participation

Failure on the delivery of participation is, in a way, the standard category of MENA states. Almost all MENA countries fall chronically short in terms of participation. Even the populist–authoritarian social contracts of the 1950s and 1960s in almost all MENA countries were good for the poor in economic but not in political terms. Admittedly, social protection cannot—and from a liberal Western normative angle, should not—fully cure the deficit. Yet, generous social protection benefits can create material conditions that make citizens reluctant to rebel against the state.

Political participation is good for citizens for two reasons: First, it is a good in itself, as humans hold psychological desires for belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation (Maslow 1943). Second, it makes sure that policies are shaped according to the interest of citizens. The second reason, however, becomes less important if the government serves at least the social and economic interests of large parts of the population even without their political participation. The main challenge for autocratic governments relying on material legitimisation is thus to identify the level of benefits that they have to give to each group of the population to sufficiently satisfy its needs and thus make a rebellion against the government risky due to the fact that all population groups have something to lose if the rebellion fails. Therefore, the government assures that most citizens still prefer to tolerate the rule of the government even without political participation (loyalty) rather than to migrate (exit) or rebel (voice).

Pay raises in the public sector and the sudden emergence of new, respective extensions of existing social transfer schemes the 2010–2011 uprisings in many Arab countries can be seen as a good testimony that provision partially substitutes participation in the legitimation of governments. Egypt, for example, slightly increased its spending on health care and unemployment benefits, raised the share of subsidies in the 2011–2012 budget by almost 25% and salaries in the public sector by 15%, and extended unlimited-term working contracts to 450,000 workers who had been working for the state so far on the basis of temporary contracts. Jordan created 21,000 new public-sector jobs, almost a third of them in the police apparatus; raised minimum and public-sector wages, unemployment benefits, and maternity pay; increased spending on social assistance and food and energy subsidies; and extended social insurance to parts of the informal sector. Morocco increased food subsidies by almost 90%, as well as minimum wage, public-sector salaries, and pensions; furthermore, it created thousands of public-sector positions. Iraq promised to provide each household with 1000 KWh electricity for free monthly. Oman, in addition to creating 50,000 new public sector jobs, increased housing and student allowances, food and energy subsidies, minimum wage, unemployment benefits, and pension payments, and decreased pension contribution rates (ESCWA 2017). Two thirds of Arab countries reduced the price of food and energy, and almost all of them provided higher salaries, half of them new jobs in the public sector (Matzke 2012). Many of the increases were reverted later (after 2015) or were eaten up by inflation when governments thought that the acute threat of further grievances had declined (ESCWA 2017).

MENA governments are conscious that substantial reductions in social protection spending endangers their legitimacy. When a larger number of them started to cut down on energy (and some also food) subsidies, they used different strategies to prevent grievances.

- The government of Iran continued to rely on provision but with a more egalitarian touch (see above).

- Morocco embarked a bit on participation. Reinvesting only parts of what it saved with subsidy reform to extend social health insurance coverage and social assistance spending, the government made huge efforts to (i) explain via extensive awareness campaigns why subsidy reform was inevitable, (ii) discuss with a large range of national NGOs how the reform could be shaped to harm the different groups of Moroccan society as little as possible, and (iii) inform the entire publication as early as possible of the results of the consultation process and the steps to be done over the years to come. However, these new ways of participation were not extended to other policy fields.In this and other instances, the main risk to real reform is that participatory opportunities concern only firmly circumscribed, often purely technical fields, or that sophisticated plans elaborated by commissions simply disappear into drawers (e.g., Zintl 2013, p. 202).

- Finally, Egypt has been relying more and more on the delivery of protection as the last and only remaining source of government legitimacy. The government cut down heavily on subsidy spending but used just a bit of what it saved for the extension of direct social transfer spending. It tightened repression much more and has been propagating the argument of being the only government able to effectively defend the individual and collective security of citizens. As warning examples, it points to Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq, where governments lost their authority to armed opposition or rebel groups and no longer were able to provide full protection to the population (Vidican Auktor and Loewe 2021).

These examples show that MENA states, chronically short in granting participation, have found ways to make up for provision cuts without stepping up participation in a meaningful way—with the exception of Tunisia, who by and large managed to safeguard their authoritarian core. Interestingly, the process that has taken place in Egypt under the rule of President Al-Sisi has not just led to the substitution of large parts of provision by increased emphasis on protection. In addition, even the little bit of participation that existed in Egypt prior to 2011 has disappeared in the meantime. The history of government initiatives to reform social health insurance in Egypt provides convincing evidence for this trend. Before 2011, the government of Egypt had made several attempts in the field but failed each time because opponents were able to organise resistance against the reform with the support of NGOs, the media, and trade unions. The government did not succeed in persuading buoyant urban middle classes of the necessity of reform, effectively repressing the opposition, or offering adequate compensation to the losers of the reform. This shows that there was still some element of participation in Egypt’s social contract under President Mubarak, which has widely vanished under President Al-Sisi, who finally pushed through the social health insurance reform by ignoring all voices arguing against it and again pointing to the fact that his government is the only guarantor of protection for Egyptians (Loewe and Westemeier 2018).

In extremely un-participatory social contracts, sector governance may provide an opportunity to still strengthen state–society interaction or even trust. In this sense, social protection programmes can also make a very relevant contribution to social contracts with a weak element of participation if the programmes have a participatory element themselves, such as involving potential beneficiaries in the design and implementation. Some donor-funded cash-for-work programmes in Jordan, for example, based their activities on intensive, systematic local consultation processes meant to achieve a broad-based consensus on the public goods to be produced by the activities (a park, a road, a community centre, a safer way to school, etc.) (for further details, see Loewe et al. 2020). Governments implementing social protection measures benefit from higher legitimacy and stability if they use more participatory setups.

4.4. States Failing on the Delivery of All Three Ps

The delivery of social protection is definitely most crucial but also the most difficult for governments failing in terms of all three Ps. Their countries typically have no nation-wide social contract anymore because large parts of the population do not recognise its legitimacy any longer. A new social contract, fulfilling citizens’ needs at least to a minimum, must therefore be built if long-term stability and security is meant to be achieved. The alternative is perpetual civil war.

Rebuilding social contracts in such contexts is an extremely challenging task because the government is short on authority, capacity, and legitimacy. Still, some governments of war-affected countries have managed to set up at least small social protection schemes and thereby lay the nucleus of a new social contract. For instance, Sierra Leone and Nepal invested in social protection after the end of the civil wars in 2002 and 2006, respectively. Nepal drastically extended the outreach of its social protection programmes (social aid, school feeding, and cash-for-work) and spending on these programmes from 0.5 to 2.5% of GDP by 2012 (Ovadiya et al. 2015). Sierra Leone’s cash-for-work programme provided a perspective for former militia fighters and was successful due to low administrative costs and the intense co-operation between the central government and local actors in designing and running the programme (Reeg 2017). Similarly, social cash assistance and a food voucher programme set up in 2011 and 2013, respectively, in the DR Congo’s conflict-affected eastern part of the country were successful due to local village chiefs’ support as well as high flexibility in the processing of benefit payments (Strupat et al. 2018).

Although social protection programmes can be run by quite different actors and achieve positive effects on human development, their possible positive effects on rebuilding social contracts and political stability depend on the government assuming responsibility for them. For instance, the above-mentioned cash-for-work programmes in Jordan (Loewe et al. 2020) and in DR Congo (Strupat et al. 2018) have had hardly any positive effect on state–society relations, as funding came from foreign donors and henceforth had no major impact on reinforcing the legitimacy of the central government. The government of Somalia, in contrast, apparently understood this lesson. Departing from a UN-run unconditional cash and voucher transfer scheme that had been installed after a terrible famine in 2010–2012, in 2016, Somalia’s new federal government developed a national development plan with the construction of a national social protection system at its core (unconditional cash assistance, cash for work, and free basic health services) (EU 2017).

All efforts to form a new social contract will fail unless most citizens understand that a new social contract is better for them than their current situation of anarchy. Often, the problem is that citizens across the former state territory are likely to realise the necessity of a new social contract at different points in time and with different willingness to compromise on actors and contents of such a new deal. Thus, a fragmentation of the territory with competing miniature social contracts is rather likely. A case in point is Syria, where different actors—al-Asad, the Kurdish-dominated Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), the Turkish-dominated Syrian Interim Government in Northern Syria, and the Syrian Salvation Government led by former al-Qaeda affiliate Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in the North-West region of Idlib—all seek to reaffirm their authority, capacity, and legitimacy vis-à-vis their competitors.

Since 2011, the Syrian al-Asad regime has not only been withdrawing state protection of large parts of the population but also targeting and exposing them to armed conflict. It quelled the initially peaceful protests by brute force—participation had never been high on al-Asad’s and his predecessors’ agenda—and applied a shoot-to-kill policy even at funeral marches. In later stages of the civil war, it targeted insurgent neighbourhoods by shelling, barrel bombs, and—as was later confirmed by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)—chemical weapons. Furthermore, al-Asad stopped the provision of basic public services and actively destroyed large parts of public infrastructure. In late 2018, about 40% of schools and a quarter of public hospitals were destroyed, whereas another quarter of hospitals were severely damaged and thus operable only in a limited way (UN-ESCWA and University of St. Andrews 2020). About half of the population has been either internally displaced or taken refuge abroad, and over 90% of the population lives in poverty and depend on humanitarian assistance. Although al-Asad declared to have won the conflict, his inability to provide for even the most basic needs of Syrian citizens—in summer 2020, inflation and a growing budget deficit forced it to reduce food subsidies—further undermines its legitimacy. Syria’s per capita budget spending has plummeted to USD 227 and thus 70% below the level of 2010, though only half as many citizens live in its territory (Christou and Shaar 2020).

The government of Yemen, in contrast, did all it could to save at least parts of its social protection system, even during times of very intense fighting, in order to uphold its claims, underline its feeling of responsibility, and preserve its popularity in large parts of the country.12 Most of the pre-war social protection system collapsed after 2015, but the Social Fund for Development (SFD) continued to operate. With funding from external donors, it provided financial support to some 300,000 people in 2017, mainly through cash-for-work projects. The SFD was not drawn into the conflict between the government and rebel armies because it is backed by the government but co-operates firmly in the design and implementation of all its activities with the local communities, who have a better understanding of the concrete needs in place (European Commission 2019).

5. Conclusions

The fragility–grievances–conflict triangle continues to threaten the stability of several MENA states. MENA citizens feel their grievances are not sufficiently addressed by governments in power. Unfulfilled demands for better protection and provision and for political participation fuel discontent and conflict. As we have shown, the very nature of these grievances points to three distinct weaknesses of social contracts, which are closely intertwined with particular shapes of state fragility.

We have provided theoretical arguments and some empirical evidence showing that social protection can be a powerful instrument to reduce state fragility and build or repair social contracts, which can be good for all involved parties: A focus on social protection benefits the well-being of citizens and contributes to a more active and inclusive way to run government affairs, and governments need to change only how they rule, but not the fact that they retain their power. A more responsive social contract promotes the stability and security of the affected countries themselves and of other countries in the same region or elsewhere.

Yet, the exact policy measures need to be calibrated with regard to the exact nature of the state fragility and the state deliverables missing from the social contract in question. Where social contracts suffer mainly in terms of protection, social protection programmes should, first of all, cover risks emanating from external or internal threats to security (e.g., terrorism, natural disasters, environmental degradation, policy failure, robbery). Where social contracts suffer mainly in terms of provision, social protection programmes should be extended in terms of scope and scale and their effectiveness, efficiency, fairness, and distributional effects should be improved. Where social contracts suffer mainly in terms of participation, social protection programmes should predominantly help citizens to participate in political decision-making processes and become more participatory themselves in their design, implementation, and administration. The most challenging setting is, of course, where social contracts fail in terms of all three Ps: protection, provision, and participation. Here, the government lacks the necessary authority, capacity, and legitimacy to set up new social protection programmes, which can potentially be at the beginning of new social contracts. However, donors can help to bridge the gap in terms of capacity, whereas increased co-operation with local actors can help to bridge the gap in terms of authority and even contribute to the reconciliation between former adversaries in fighting.

As illustrated by the empirical evidence discussed, some general rules apply for all scenarios in order to maximise the positive effects of social protection programmes on social contracts. (i) Governments do not need to run all social protection programmes themselves, but must assume overall responsibility so that the overall social protection system covers all parts of the population against their most salient risks and against poverty. (ii) All programmes should be as universal as possible, i.e., provide benefits to people because they are citizens, i.e., contracting parties, rather than out of a patrimonial feeling. (iii) If, however, benefits have to be targeted to specific sub-groups of the population, the benefits should still be based on transparent, individual rights rather than by arbitrariness or allegiance. (iv) The benefits should be fully reliable and predictable in advance in order to maximise beneficiaries’ feeling of security. (v) The governance of the social protection programmes themselves should be transparent, rule-based, and as participatory as possible. (vi) The different programmes in one country should be well co-ordinated and harmonised in order to ease the exchange of data, avoid duplication in efforts and gaps in coverage, and produce synergies and coherence (Loewe and Schüring 2021).

MENA social contracts remain loopholed, predominantly by lack of participation. MENA leaders are not inclined to concede more participation, but through social protection—especially if delivered through more participatory schemes—they could reduce citizens’ grievances and thus state fragility. If MENA autocrats prove willing to negotiate social contracts in regard to fairer and more inclusive social protection schemes (something that is rather costly to them), they could renew trust, legitimacy, and, ultimately, their rule (something that should be very dear to them). To do so, they would have to earmark public expenditure for better social protection. Redirecting expenditure is difficult because of high public debts and the need to cut back on entrenched clientelist prerogatives (i.e., the need to re-negotiate cronies’ selective participation). Yet, in light of the instable social contracts and unpredictable fragility–grievances–conflict dynamics, this is still likely to be a good investment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and T.Z.; methodology, M.L. and T.Z.; validation, M.L. and T.Z.; formal analysis, M.L. and T.Z.; investigation, M.L. and T.Z.; resources, M.L. and T.Z.; data curation, M.L. and T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L. and T.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.L. and T.Z.; visualization, M.L. and T.Z.; supervision, M.L. and T.Z.; project administration, M.L. and T.Z.; funding acquisition, M.L. and T.Z. Both authors wrote all parts of the article jointly. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Both authors work in the research project ‘‘Stability and Development in the Middle East and North Africa” funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Co-operation and Development (BMZ). The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the position of the BMZ.

Data Availability Statement

The quoted empirical data was collected for a different research project and will be made available on the server of the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) at a later point in time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | We use the term “Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region” in accordance with the widely-used definition by the World Bank, covering Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Malta, Morocco, Oman, the Palestinian Occupied Territories, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen, as well as—though rather implicitly—West Sahara. Some organisations would also include Mauritania, Somalia, Sudan, and/or Turkey. |

| 2 | Islamic governments are accountable for the provision of social aid to those in need, including non-Muslims. Social justice (cadāla iğtimāciyya) is a central goal of Islamic policy. This does not mean the complete leveling of income and wealth differences (equity of outcome), nor pure equity of opportunity. Islamic governments provide for social protection among others by imposing zakāt (a levy mainly on wealth) or through the awqāf (voluntary religious endowments). For these and other Islamic instruments of social protection, see Jawad and Eseed (2021); Loewe (2010a, pp. 68, 82); Tajmazinani and Mazinani (2021, pp. 28–31). |

| 3 | e.g., for the MENA region, Heydemann (2007); Kinninmont (2017); UNDP—United Nations Development Programme and AFESD—United Nations Development Programme and Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (2002); Yousef (2004). |

| 4 | Grävingholt et al. (2015, p. 1284) defined state fragility also as “fragile statehood”, as it “is not so much the fragility of the state as such in a legal or even ontological sense as it is the state’s [lacking] ability to fulfil its basic functions.” |

| 5 | Egypt, for example, long had different power poles inside the government: the army, the president, the minister of finance, and the minister of labour. Likewise, society can be quite divided into social classes, ethnic groups, tribes and clans, religious communities, tribal groups, and other interest groups. |

| 6 | For instance, for some years several social contracts have existed in different parts of Syria (Furness and Trautner 2020). |

| 7 | “Guarantee safety of citizens” and “defend country against neighbouring countries” represented protection; “provide education, health and sanitation to all” and “create employment opportunities” represented provision; and “enable citizens to participate in political decisions” and “allow citizens to elect the government” represented participation. |

| 8 | Food subsidies in Egypt, for example, reduced income poverty rates by just a third in 2009, whereas energy subsidies reduced income poverty rates by less than a fifth in 2004, even though both programmes together consumed 8% of GDP at that time (Silva et al. 2012). |

| 9 | In 2017, private household contributions to total national health care spending amounted to 72% in Sudan, 58% in Iraq, 56% in Egypt, 54% in Morocco, and about 30% in Jordan, Bahrain, Lebanon, and Algeria (Loewe forthcoming). |

| 10 | For example, 46 and 45% of the women interviewed in Jordan (2018) and Egypt (2008), respectively, declared that they had difficulties financing urgently needed health care. The shares were even higher in the bottom wealth quintile (64% and 70%, respectively) (cited in Loewe forthcoming). |

| 11 | A comparatively low share of Egyptian respondents admitted to being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the al-Sisi government’s 3P delivery. We assume that this is partly due to a bias introduced by respondents’ mistrust and fear of government repression and does not mirror the de facto quality of government services. At the same time, Egyptians seem to be less critical and more loyal to the government in general even if they have no trust in it—something that Loewe and Albrecht (2021) call a “rallying behind the flag”-effect. |

| 12 | According to Arab Barometer (2021) data, the share of Yemenites with great or medium trust in the government (cabinet) increased from 41% (2013) to 57% (2019). |

References