“Why Can’t We?” Disinformation and Right to Self-Determination. The Catalan Conflict on Twitter

Abstract

:1. Introduction

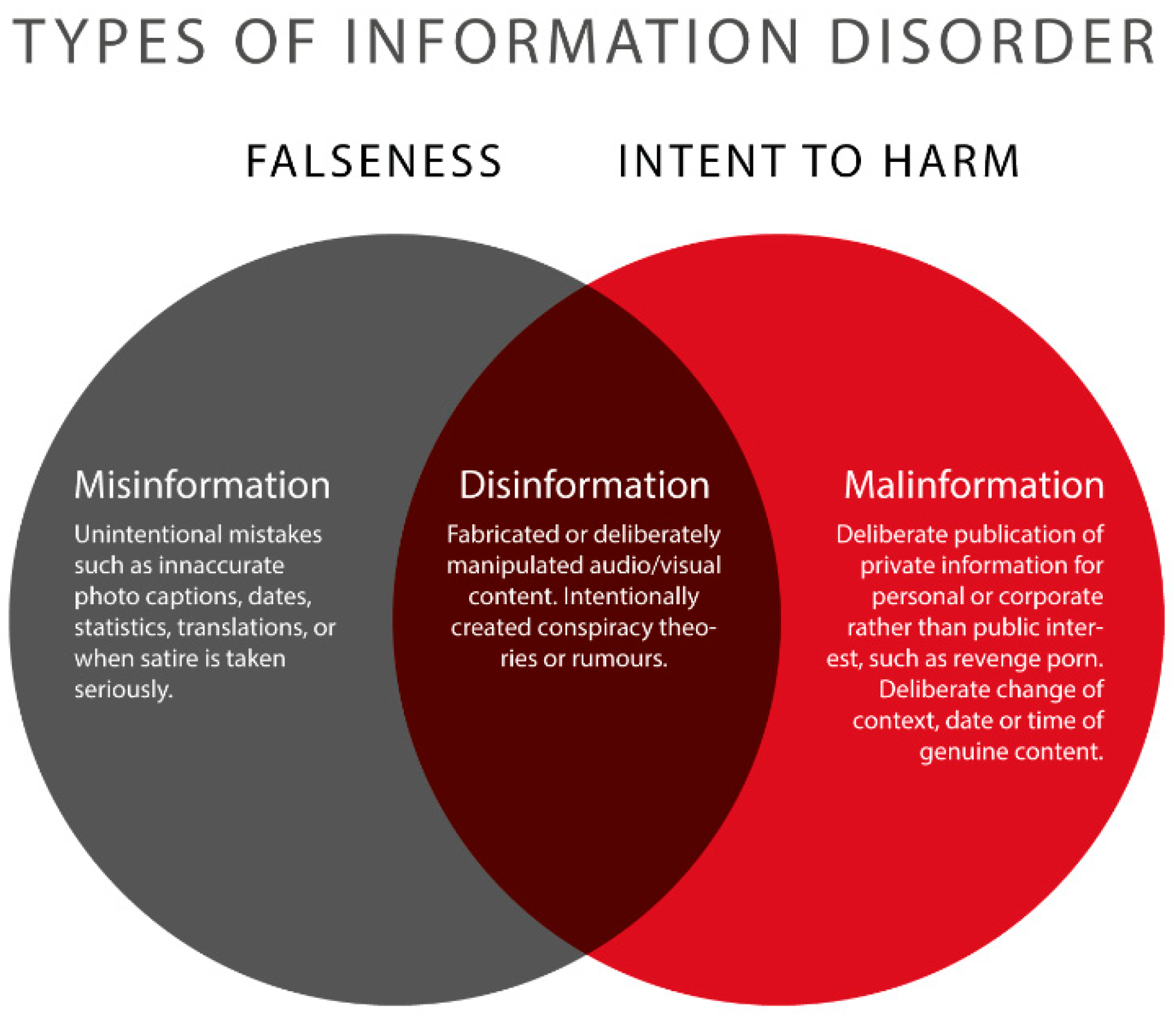

1.1. Disinformation, Misinformation, Malinformation

1.2. Case Study: Peoples’ Right of Self-Determination and the Case of Catalonia

1.3. The Right of Self-Determination

“All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.”

1.4. Twitter as a Stage for Virtual Politics

1.5. Text Mining to Analyse Twitter

1.6. Hypothesis and Research Questions

- Q1 What sort of disinformation exists around the concept of self-determination according to experts?

- Q2 How can this disinformation be identified on Twitter and described within the context of the Catalan independence conflict?

- Q3 What emotions become visible when the right of self-determination is mentioned in the case study?

2. Materials and Methods

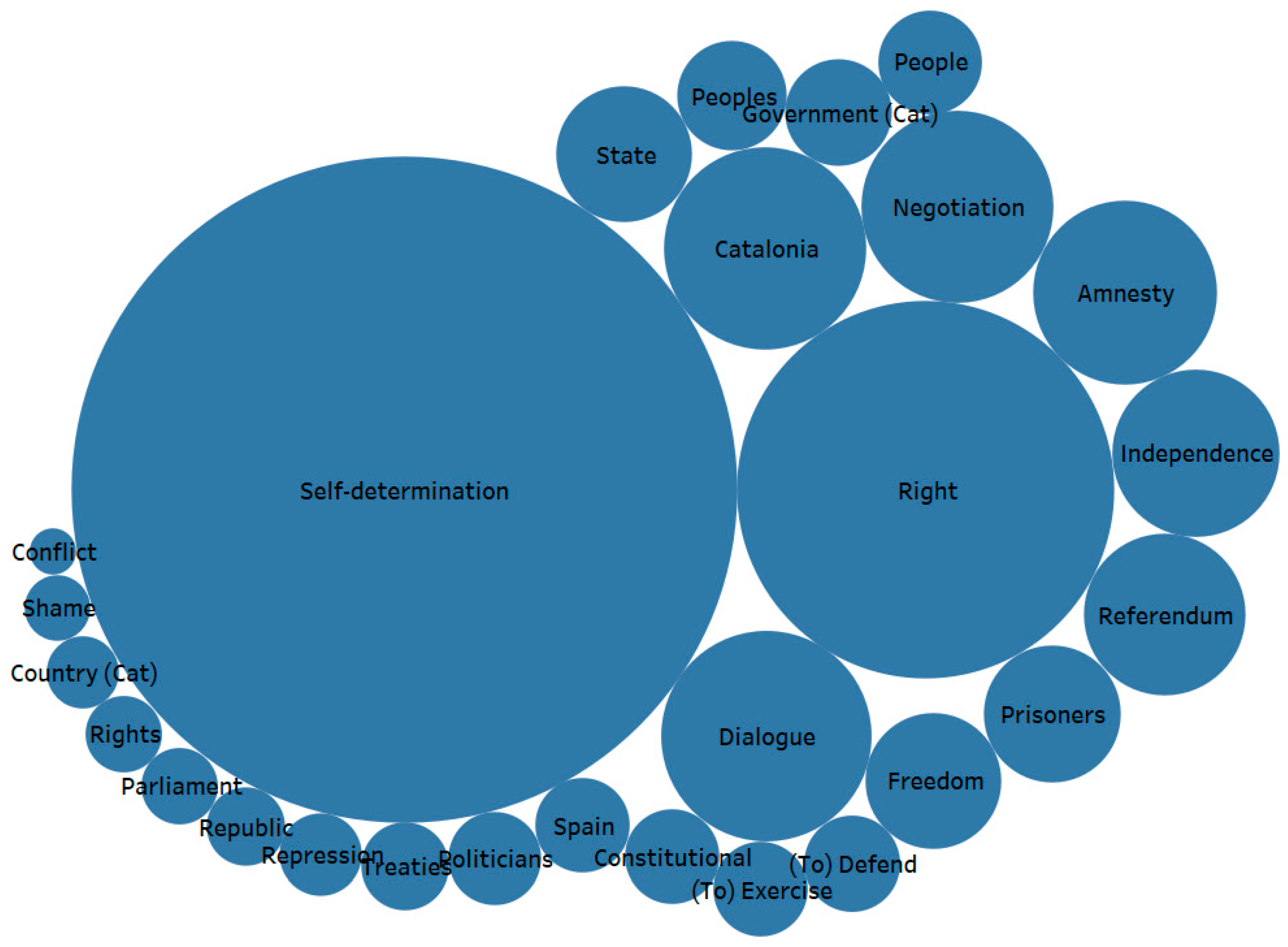

3. Results

“We have the right of self-determination because we are a nation even though we do not have a State and Spain has the obligation to authorise one self-determination referendum if we request it, since that is our right recognised in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (UN 1966) ratified by Spain”

“Self-determination is a right envisaged in signed, ratified and published international treaties as foreseen in the Spanish Constitution which was incidentally drafted and approved after these treaties.”“Precisely self-determination is constitutional. The law and the constitution are used to protect one’s own interests; it is distorted, manipulated and utilised according to what is convenient for your “mother-country-saving” discourse.”“The Spanish State has signed the international treaties and therefore they have come to form part of the Spanish legal framework and self-determination is a right! Scatterbrain!”

“Peoples’ self-determination is constitutional. Hope you have some time to read it (the Spanish Constitution). As always, the españolistos (a derogatory blend of españolito [little Spaniard] and listos [clever]) deceiving the people.”“[Are you saying] that no Constitution recognises the right of self-determination?? … what do you think (articles) 154–160 of the SPANISH Constitution are? Does the ReiÑo23 (sic) respect the international treaties that it has assimilated?? The right of self-determination is a fundamental principle in public international law.”

“Isolated cases? The right of self-determination is a recognised right and it internationally protects ALL the peoples (nations) and Catalonia is actually a much older nation than Spain (I did not say Castile, I said Spain, because Castile is indeed a nation with years of history).”

“It is no OPINION, these are FACTS. If you cannot distinguish it, you have a problem, and I am not trying to avoid the issue: I mean that the Right of Self-Determination CANNOT be applied as a Right to Secession to a region of a democratic country which has never been a colony.”“Neither Veneto nor Bavaria or Texas or Brittany or Ulster or California … nor many others. Perhaps the “Right of Self-Determination” is NOT what you have been told about a supposed “Right to Secession”.

“Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948. Right of self-determination of peoples: Part I Article I of the economic, social and cultural rights. Spare me the mantra of “for the colonies”.

“Self-determination is a right envisaged by the UN. Whether you like it or not. The 1978 constitution is a Francoist one. Catalonia lives in the 21st century, while Spain remains anchored in the terrible 20th century.”

“How funny it will be if amnesty is achieved, the prisoners go out and they themselves remind you that, if they have been in prison, it was for defending the right of self-determination”25“We all would like a dialogue table. But the Spanish State will never talk about self-determination. Never”26“don’t worry, Spain will soon come and forbid it”27“That the General State (National) Budget should include an entry to carry out a legally binding self-determination referendum in Catalonia. Can you tell your boss? Thanks”

“But how do we want to negotiate self-determination with a state like FachaÑa (blend meaning “Fascist Spain”)?? Have we lost our senses? We already voted and earned the right to be the Catalan Republic at the referendum of 1 October 2017 and independence was declared, bollocks! Enforce it or you can all bugger off!”“Self-determination is a right. And you are nobody to prevent us from exercising a right. It is also constitutional and thus legal. You fascists shall not pass!”“It is disgusting. And it is even more so that, with international rights such as that of self-determination, a country can OBLIGE us to form part (of it) forever and forcibly, denying us the right to BE free."“Every country has enjoyed self-determination sooner or later. Why CAN’T we?”

“When you say compatriots, do you mean those who deny us the language, those who hate us ‘cos we are Catalans, those who oblige us to belong to their state, refusing to accept a referendum and our self-determination? Those who sing “Go get them!”? Who are the “compatriots”?’.”“Cos this is the real basic problem that has been dragging on for 3 years: Even though the CAT nation has the right of self-determination recognised by international law, the oppressive regime will never admit political actors that can threaten its totalitarian integrity”

4. Conclusions

- Q1. What sort of disinformation exists around the concept of self-determination, according to experts?A1: The external and internal dimensions of the right of self-determination are ignored; this right is confused with that of secession and, furthermore, the political dimension (wanting independence) is confused with the legal one (having the right to independence).

- Q2. How can this disinformation be identified on Twitter and described within the context of the Catalan independence conflict?A2: By combining social science methods, artificial intelligence, and data mining, we verified that disinformation is present in every segment of the sample, made up of 30 micro-forums extracted from a corpus of 102,634 tweets. They all reflect disinformation to a greater or lesser extent. Conversations show how deeply concepts are merged, with the result of individuals claiming their right to secession based on the UN articles, a right that they have as “the people”. Consequently, the Spanish State is accused of being fascist or undemocratic for violating what they consider to be a basic and internationally recognized human right—the right to secession.

- Q3. What emotions become visible when the right of self-determination is mentioned in the case study?A3: Very clearly negative ones, including contempt, hatred, anger, and fear, and an extensive use of irony. Negativity is directed to the Spanish State, the ideological opponents—the unionists—, and also towards their own politicians for their “weakness” in fighting against the former two. Only 3.5% of the emotions detected were positive.

5. Discussion and Proposals for New Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This is the expression used to refer to the institutional and social crisis which is taking place in Spain as a result of the so-called Catalan independence process (the Procés), which pursues to achieve Catalonia’s independence. |

| 2 | Resolution 1/XI of the Parliament of Catalonia dated on 9 November 2015. |

| 3 | A/RES/1514(XV); A/RES(1541(XV); A/RES/2625(XXV). |

| 4 | It is not relevant for this work to choose among the various definitions of “people” within the context of studies on nationalism, hence our decision to assume the broadest concept, according to which “people” is a group of individuals who see themselves as a people, without any further requirements. |

| 5 | Even though experts were not directly asked about their ideological views, they were asked to include among their recommendations other experts whose position was known to be different from theirs. |

| 6 | Defined in its internal and external dimension in a previous section. |

| 7 | According to this, the mere existence of pro-independence parties in Spain would show that the political principle of self-determination is respected. |

| 8 | Experts place emphasis on the non-existence of this right in any country around the world, with the exceptions of Liechtenstein, Ethiopia, and Saint Kitts and Nevis. |

| 9 | Or national legal frameworks, regardless of whether they have a constitution or not. |

| 10 | The Spanish State. |

| 11 | The selection was limited to tweets published in the Catalan language so that we could be sure that they referred to the case study and in order to dodge the abundant contents in Spanish related to other forms of self-determination, such as those of other human groups (indigenous peoples, the Sahara, etc.,) or in other fields such as gender or euthanasia. |

| 12 | Sets of terms which are semantically relevant in a text. |

| 13 | Logically, the micro-forum may have been extracted from a larger conversation (forum) in which not all tweets include “self-determination”, but a decision was made to keep only those which contained that term so that we could focus on them and avoid possible drifts in the conversation. Therefore, each micro-forum is in itself a sample of a bigger forum. |

| 14 | The strategy utilised prevented potential biases in the construction of micro-forums, since it was carried out iteratively in two steps: We first built the hot-words (frequent words), which are the words with a high level of appearance in every tweet and whose extraction is based on their frequency of appearance range in the entire corpus. All stop-words, built from a group of 614 words, were filtered during this stage (Yzaguirre n.d.). In a second step, we identified within the set of dialogues (micro-forums) which of those words could be regarded as keywords and to what extent. Or, expressed differently, we considered the entire corpus to identify the keywords in micro-forums. In our work, this technique was combined with other metrics, such as the Inverse Document Frequency (IDF*TF), which make it easier to understand the text and the discourse. Several programs in Python language were likewise developed for the extraction and transformation of tweets, their metadata, as well as to detect emotions in tweets. With the aim of building a training corpus and reducing the dimensionality of the problem, deep networks were used to classify content by means of the Keras/Tensorflow library. Twitter’s Premium API provides plenty of data, which makes it possible to cross them and to construct a more elaborate text from possible conversations which are generated from the replies (in_reply_to) and the aforesaid retweeting (quoted_tweet). |

| 15 | LSI is successfully used in Information Systems for semantic search from heuristic methods based on the singular value decomposition (SVD) with matrix factorisation. |

| 16 | Geneva Affect Label Coder. |

| 17 | These are usual derogatory expressions referred to Spaniards uttered within the pro-independence context. |

| 18 | Terms and stems used to identify each category of emotion are in Catalan. |

| 19 | Although some of the terms in Table 2 do appear in the messages, their semantic relevance is not sufficiently significant to appear in the topic. |

| 20 | The experts consulted agree that Spain is objectively a full democracy. However, they also point out, subjectively and according to their respective political ideology, that its level of democracy could be improved to a greater or lesser extent. For this reason, we do not consider a tweet as disinformation when it says that Spain is not a democracy, but when that statement is grounded on the supposed lack of compliance with the UN covenants or the actual Spanish Constitution. |

| 21 | Candidate for Mayor of Barcelona by the political party Ciudadanos/Ciutadans in 2019. |

| 22 | He reacts to a demonstration in Barcelona where that right was requested for Catalonia. |

| 23 | The Spanish word REINO “kingdom” deliberately written with Ñ in a derogatory sense. |

| 24 | Imprisonment of 12 politicians and representatives of civil society for events related to the illegal referendum of 1 October 2017. |

| 25 | The term in the original tweet is“divertit”, matching “divert*” in Table 3, Amusement/Pleasure/Enjoyment category. |

| 26 | In the original tweet, “agradaria”, matching “agrad*” in Table 3, Satisfaction/Happiness/Joy category. |

| 27 | In the original tweet, “tranquil”, matching “tranquil*” in Table 3, Relaxation/Serenity/Relief category. |

| 28 | The average number of followers per user in the corpus analysed was 2841. |

| 29 | Calculated on an average of 30 viewings per reached user. |

References

- Asociación Española de Profesores de Derecho Internacional y Relaciones Internacionales (AEPDIRI). 2017. Declaración Sobre la Falta de Fundamentación en el Derecho Internacional del Referéndum de Independencia que se Pretende Celebrar en Cataluña. Available online: https://web6341.wixsite.com/independencia-cat (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Alonso-Muñoz, Laura, Susana Miquel-Segarra, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2016. Un potencial comunicativo desaprovechado. Twitter como mecanismo generador de diálogo en campaña electoral. Obra Digital: Revista de Comunicación 11: 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparici, Roberto, David García-Marín, and Laura Rincón-Manzano. 2019. Noticias falsas, bulos y trending topics. Anatomía y estrategias de la desinformación en el conflicto catalán. Profesional De La Información 28: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbós, Xavier. 2020. Legalidad y Legitimidad en el ‘Procés’. Idees. Available online: https://revistaidees.cat/es/legalidad-y-legitimidad-en-el-proces/#notes-group-00 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Arce García, Sergio, Tatiana Cuervo Carabel, and Natalia Orviz Martínez. 2020. #ElDilemaSalvados, análisis de las reacciones en Twitter al programa de Jordi Évole sobre Cataluña. Revista Prisma Social 28: 1–19. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/3312 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Atienza, Manuel. 2020. Sobre un derecho inexistente. A propósito de «Democracia y derecho a decidir» de Josep M. Vilajosana. Eunomía. Revista en Cultura de la Legalidad 19: 422–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, Yates, and Neto Ribeiro. 1999. Modern Information Retrieval. New York: ACM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Jonah, and Katherine L. Milkman. 2012. What Makes Online Content Viral? Journal of Marketing Research 49: 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergmann, Eiríkur. 2020. Populism and the politics of misinformation. Safundi 21: 251–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Alfonso, Ignacio. 2018. Creencias, posverdad y política. Doxa Comunicación 27: 421–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, Kai. 2019. The People Know Best: Situating the Counterexpertise of Populist Pipeline Opposition Movements. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109: 581–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovi, Claudio, Luca Telesca, and Roberto Navigli. 2015. Large-scale information extraction from textual definitions through deep syntactic and semantic analysis. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 3: 523–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, Allen. 2017. Secession. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco Polaino, Rafael, Ernesto Villar Cirujano, and Laura Tejedor Fuentes. 2018. Twitter como herramienta de comunicación política en el contexto del referéndum independentista catalán: Asociaciones ciudadanas frente a instituciones públicas. Icono 14 16: 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió (CEO). 2021. Encuesta Sobre Contexto Político en Cataluña. Available online: https://ceo.gencat.cat/ca/barometre/detall/index.html?id=7988 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Deerwester, Scott, Susan T. Dumais, George W. Furnas, Thomas K. Landauer, and Richard Harshman. 1990. Indexing by Latent Semantic Analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 41: 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denia, Elena. 2020. The impact of science communication on Twitter: The case of Neil deGrasse Tyson. Comunicar: Revista Científica Iberoamericana de Comunicación y Educación 28: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFranzo, Dominic, and Kristine Gloria-Garcia. 2017. Filter bubbles and fake news. XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students 23: 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2020. Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Tackling COVID-19 Disinformation—Getting the Facts Right. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020JC0008&from=ES (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Ferreres, Víctor. 2019. Cataluña y el derecho a decidir. Teoría y Realidad Constitucional 37: 461–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gandomi, Amir, and Murtaza Haider. 2015. Beyond the hype: Big data concepts, methods, and analytics. International Journal of Information Management 35: 137–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García, Mario, and Liliana Alejandra Chicaíza. 2018. Brexit, paz y Trump: Enseñanzas para los economistas. Revista de Economía Institucional 20: 129–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hameleers, Michael. 2020. Populist Disinformation: Exploring Intersections between Online Populism and Disinformation in the US and the Netherlands. Politics and Governance 8: 146–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hernández-Santaolalla, Víctor, and Salomé Sola-Morales. 2019. Postverdad y discurso intimidatorio en Twitter durante el referéndum catalán del 1-O. Observatorio 13: 102–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ireton, Cherilyn, and Julie Posetti, eds. 2018. Journalism, ‘Fake News’ and Disinformation: Handbook for Journalism Education and Training. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Kruikemeier, Sanne. 2014. How political candidates use Twitter and the impact on votes. Computers in Human Behavior 34: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, Ullrich K. H. Ecker, and John Cook. 2017. Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 6: 353–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Llorca-Asensi, Elena, Maria-Elena Fabregat-Cabrera, and Raúl Ruiz-Callado. 2021. Desinformación Populista en Redes Sociales: La Tuitosfera del Juicio del Procés. OBS*Observatorio 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Christopher D., Prabhakar Raghavan, and Hinrich Schütze. 2008. Introduction to Information Retrieval. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos García, Silvia. 2018. Las Redes Sociales como Herramienta de la Comunicación Política. Usos Políticos y Ciudadanos de Twitter e Instagram. Castellón: Programa de Doctorat en Ciències de la Comunicació, Universitat Jaume I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, Jörg, and Matthias Kohring. 2008. The Content Analysis of Media Frames: Toward Improving Reliability and Validity. Journal of Communication 58: 258–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, Maria. 2016. David Núñez: “Es infundado decir que hay sesgo político en Twitter”. Expansión. Available online: https://www.expansion.com/economia/politica/elecciones-generales/2016/06/22/5769008f468aeb0f188b4570.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Moreso, Josep. 2020. Los shibolets del procés: Vilajosana sobre el derecho a decidir. Eunomía. Revista en Cultura de la Legalidad 19: 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreso, Josep. 2021. De secessione. The Hideouts of The Catalan Way. Las Torres de Lucca. International Journal of Political Philosophy 10: 47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Orriols, Lluís, and Sandra León. 2021. Looking for Affective Polarisation in Spain: PSOE and Podemos from Conflict to Coalition. South European Society and Politics 25: 351–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmunden, Mathias, Alexander Bor, Peter Bjerregaard Vahlstrup, Anja Bechmann, and Michael Bang Petersen. 2021. Partisan Polarization Is the Primary Psychological Motivation behind Political Fake News Sharing on Twitter. American Political Science Review 115: 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariser, Eli. 2011. The Filter Bubble: How the New Personalized Web Is Changing What We Read and How We Think. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Parmelee, John H., and Shannon Bichard. 2011. Politics and the Twitter Revolution: How Tweets Influence the Relationship between Political Leaders and the Public. Plymouth: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Payero López, Lucía. 2016. El derecho de autodeterminación en España: Breve explicación para extranjeros estupefactos y nacionales incautos. Revista D’estudis Autonòmics federals 23: 46–79. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Curiel, Concha, and Mar García-Gordillo. 2018. Política de influencia y tendencia fake en Twitter. Efectos postelectorales (21D) en el marco del Procés en Cataluña. Profesional De La Información 27: 1030–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Real Academia Española (RAE). n.d. Definición de Autodeterminación. Diccionario Panhispánico de Español Jurídico. Available online: https://dpej.rae.es/lema/autodeterminaci%C3%B3n (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Rodón, Toni, Francesc Martori, and Jordi Cuadros. 2018. Twitter activism in the face of nationalist mobilisation: The case of the 2016 Catalan Diada. Revista D’Internet, Dret i Política 26: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Jonathan. 2017. Brexit, Trump, and Post-Truth Politics. Public Integrity 19: 555–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Miguel, Carlos. 2019. Sobre la insostenible pretensión de la existencia de un «derecho de autodeterminación» para separarse de España al amparo del Pacto Internacional de los Derechos Civiles y Políticos. Anuario Español de Derecho Internacional 35: 103–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, Klaus R. 2005. What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information 44: 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srijan, Kumar, and Neil Shah. 2018. False Information on Web and Social Media: A Survey. arXiv arXiv:1804.08559. [Google Scholar]

- Tumasjan, Andranik, Timm Sprenger, Philipp Sandner, and Isabell Welpe. 2010. Predicting Elections with Twitter: What 140 Characters Reveal about Political Sentiment. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 4: 178–85. [Google Scholar]

- Vilajosana, Josep. 2020. Democracia y derecho a decidir. Eunomía. Revista en Cultura de la Legalidad 18: 375–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wardle, Claire. 2017. Fake news. It’s Complicated. First Draftl. Available online: https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/fake-news-complicated/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. One Year on, We’re Still Not Recognizing the Complexity of Information Disorder Online. First Draftl. Available online: https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/coe_infodisorder/ (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Weissenborn, Dirk, Leonhard Hennig, Feiyu Xu, and Hans Uszkoreit. 2015. Multi-objective optimization for the joint disambiguation of nouns and named entities. Paper presented at 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Beijing, China, July 27. [Google Scholar]

- Wihbey, John P. 2014. The Challenges of Democratizing News and Information: Examining Data on Social Media, Viral Patterns and Digital Influence. Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series, #D-85; Cambridge: Harvard Kennedy School. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, Samuel C., and Philip N. Howard. 2016. Political Communication, Computational Propaganda, and Autonomous Agents. International Journal of Communication 10: 4882–90. [Google Scholar]

- Yzaguirre, Lluís. n.d. Catalan Stop Words. Available online: http://latel.upf.edu/morgana/altres/pub/ca_stop.htm (accessed on 3 May 2021).

| 1. That (right of) self-determination and (right to) secession or independence are synonymous |

| 2. That International Law recognises the right to secession of any people |

| 3. That Catalonia has a right to secession according to International Law |

| 4. That Catalonia’s right to secession stems from the UN covenants |

| 5. That Spain10 infringes International Law by not permitting Catalonia’s secession |

| 6. That Spain is violating its own Constitution by not allowing Catalonia’s secession |

| 7. That the Spanish State does not recognise peoples’ right of self-determination |

| 8. That Catalonia does not have/enjoy a right of self-determination |

| covenants | In plural, they refer to ICCPR and ICESCR |

| treaties | |

| UN | The United Nations Organization within which such treaties are produced |

| peoples | In plural form, it alludes to the literal wording of Article 1 of the covenants |

| constitution | It refers to the Spanish Constitution and denotes an allusion to the legal framework which permits—or does not permit—to fit certain claims |

| legal | They suggest that this is a debate on legality within the framework of the right of self-determination |

| right | |

| recognition | It is an expression used to demand that the existence of a right (to decide or to secession) be admitted |

| (to) exercise | This is the verb utilised to express that Catalonia has a recognised right and to denounce the Spanish State for preventing its exercise |

| human | They link the non-acceptance of the right of self-determination with a violation of Human Rights and fundamental rights. |

| fundamental |

| Admiration/Awe/Surprise | ador* | sorpres* | atordit* | enlluernad* | embadali* | captiva* | fascina* | meravell* | enart* | venera* |

| adoració* | esbalaï* | bocabada* | sobresalt* | desconcertat* | atònit* | (adorn*) | ||||

| Amusement/Pleasure/Enjoyment | divert* | humor* | riall* | jugan* | jogass* | somri* | diversió | gaudi* | encant* | resplend* |

| (amenaç*) | (amenac*) | amen* | ||||||||

| Being touched (Emotion)/Sympathy | emocio* | compade* | compass* | empatía | empàtic* | |||||

| Satisfaction/Happiness/Joy | content* | satisf* | alegr* | benaura* | delicios* | encanta* | agrad* | plaent* | feliç* | content* |

| exultant | eufor* | exalt* | estimula* | exult* | gaubança | joio* | alegr* | encantad* | gaub* | |

| Feeling(s)/Gratitude | afecte | cariny* | amist* | tendresa* | gràcies | agraï* | ||||

| Hope | fidel* | esperança* | optimis* | |||||||

| Interest/Enthusiasm | despert* | apassiona* | atent* | curi* | ansio* | fascina* | abstret* | entusiasta* | fervent* | interes* |

| fervor* | il.lus* | |||||||||

| Longing | somni | deler* | fantasi* | fris* | rememorar | nostàlgia | enyor* | nostalg* | penedi* | desitj* |

| anhel* | somiar | |||||||||

| Pride | orgull* | supèrb* | ||||||||

| Relaxation/Serenity/Relief | calma* | desenfadat* | indiferent* | desapassiona* | equanim* | afable* | Despreocupat | placid* | equilibr* | relax* |

| alleuj* | seren* | tranquil* | ||||||||

| Anger | enfad* | ràbio* | enrab* | Furiós | fúria | enfurism* | fregi* | rabi* | còler* | embog* |

| ressent* | temperament | disgust* | ences* | |||||||

| Anxiety | ansie* | aprehensi* | reticent* | Cangueli | nervi* | turbac* | recel* | previngut | preocupat | problem* |

| Boredom/Disgust | fastig* | indifer* | tedi* | Desgast | aversi* | detest* | disgust* | desagrad* | aversió | desassaborir |

| fàstic* | indispo* | repugn* | repuls* | reprova* | abomina* | |||||

| Desperation/Despair/Disappointment | perdu* | decaigu* | desconsola* | desepera* | abat* | decebu* | desconten* | desencis* | desil·lusiona* | frustra* |

| resigna* | amarg* | boicotej* | ||||||||

| Dissatisfaction/Sadness | infeli* | disgust* | abat* | Dolor | taciturn* | desespera* | melanco* | aflig* | trist* | llagrim* |

| plor* | llàstima | |||||||||

| Fear | esglai* | alarma* | Por | esfereid* | horror* | aterr* | terror* | amenac* | amenaç* | (por ellos) |

| Guilt/Shame | avergony* | desgracia* | humilia* | ruboritza* | culpa* | Contrició | culpabl* | remordiment* | penedi* | |

| Contempt/Hatred | denigr* | desaprov* | burlet* | desprecia* | arrogant | botifler* | ñordo* | nyordo* | *Ñ* | charneg* |

| amarga* | odi* | rencor* | l’odi | facha | fasci* | |||||

| Tension/Stress/Irritation | malestar | estres* | cansa* | tensio* | rigid* | molest* | exaspera* | malhumora* | indigna* | irrita* |

| enfada* | crispa* | |||||||||

| Lies (Lying) (Deceit) | mentider* | fals* | mentida* | Mendacitat | fal·làcia | falsedat* | Bola | conte | engany | embolic* |

| Ficción | Calúmnia | Fake |

| Mf | N | Terms |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 95 | constitutional, right, peoples, treaties, international (pl), crime, constitution, legal, referendum, democracy, Barcelona, Spain, Spanish (m), referendum/plebiscite, Spanish (f), rights |

| 2 | 55 | dialogue, right, table (Cat), independence, (to) speak, years, referendum, PSOE (Spanish (Worker’s) Socialist Party), conflict, (it) exercises, political/politician, no, proclamation, negotiation |

| 3 | 45 | motion, right, (to) vote, solutions, people, axis, (I) trust, PSOE, Catalonia, central, (to) negotiate, policies, therefore, fully, thanks, prisoners, Madrid |

| 4 | 46 | right, referendum, Catalonia, dialogue, social (pl), rights, shame, prisoners, repression, agreement, politicians, progress |

| 5 | 51 | comuns (members of the party En Comú Podem), (they) defend, (they) want, moment, Catalonia, Entesa (agreement of centre-left and left-wing political parties in Catalonia), only, part, right, (to) search, (we) defend, (you) say, people, |

| 6 | 47 | right, referendum, dialogue, amnesty, prisoners, freedom, negotiation, nothing, recognition, table (Sp), table (Cat), no, independence, politicians |

| 7 | 44 | right, budget, (to) speak, (to) accept, population, error, politicians, govern (Cat), trial, partisan, social (pl), historic(al), prison, right, arms, interests, (to) approve |

| 8 | 88 | citizens, issue, important, right, (that should) resolve, (to) decide, democracy, (to) resolve, people, ciutadans (political party)/citizens, no, referendum, |

| 9 | 40 | right, unilateralism, referendum, rights, country, (to) leave, human (pl), Spain, no, peoples, (to) vote, unilateral, against, Catalonia |

| 10 | 40 | amnesty, right, independence, referendum, freedom, this, prisoners, shame, dialogue, agreement, referendum, exiles |

| 11 | 39 | table (Cat), (to) defend, negotiation, nothing, independence, right, less, defence, forgotten, |

| 12 | 51 | change, motion, (to) withdraw, all, right, botiflers (derogatory expression towards Spanish people), to agree on/negotiate, senators, parliament, (to) relinquish |

| 13 | 25 | right, peoples, prisoners, fight, politicians, Catalonia, people, against, freedom, justice, Catalan, safe/sure, independence |

| 14 | 24 | right, independence, referendum, freedom, prisoners, politicians, exiles, dialogue, peoples, president, democracy, prisoners |

| 15 | 25 | right, Catalan(s), welfare, interests, all, progress, president, Catalonia, politicians, pathetic, government (Cat), people, nothing |

| 16 | 29 | motion, change, right, (to) withdraw, parliament, (to) agree on/negotiate, no, afterwards, unity, senators, part, (to) oblige |

| 17 | 20 | dialogue, amnesty, right, change, (to) speak, investiture, referendum/plebiscite, people, prisoners, treason, situation, seems, agreement |

| 18 | 38 | (to) negotiate, negotiates, Brussel(s), right, independence, enough, president, Europe, Catalan(s), (to) deceive, (it) exercises, dialogue, table (Cat), declaration |

| 19 | 22 | dialogue, right, prisoners, (to) speak, freedom, amnesty, referendum |

| 20 | 20 | amnesty, all, possible, exercise, right, press, position, no, (to) speak, out(side), (to) leave/divide, Catalan (f), enough |

| 21 | 38 | right, favourable (pl), (to) save, Catalonia, majority, very, against, voters |

| 22 | 22 | exercise, Republicanism, that, State, fronts, barn, broad (pl), Catalonia, (to) convert, majorities |

| 23 | 25 | freedom, you (pl), Catalan (f), Republic |

| 24 | 19 | referendum, table (Cat), dialogue, pro-independence demonstrations, amnesty, negotiation, repression, right |

| 25 | 20 | supporters of sovereignty, government (Cat), comuns (members of the party En Comú Podem), amnesty, broad (m), centre, front, seriousness, broad (f), (they) vote, right-wing parties |

| 26 | 20 | consensuses, against, Catalonia, consensus, independence, (to) want, democratic (pl), broad (pl), (to) articulate, congress |

| 27 | 20 | independence, freedom, republic, acquittal, without, path, less, (to) vote |

| 28 | 20 | table, right, Catalonia, government (Sp), time(s), dialogue, side, repression, debate, (to) defend, sectarian (m) |

| 29 | 21 | (to) negotiate, State, motion, right, Catalonia, negotiation, parliament, independence, power, Spanish (m) |

| 30 | 15 | right, (to) speak, table (Cat), table (Sp), Statute, achieved, (to) negotiate, prisoners, negotiation, change, determined, (to) exercise, referendum, Catalan(s) |

| MICRO-FORUMS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 1* | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 2* | 30 | |

| Admiration (Awe)/Amazement | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amusement (Fun)/Pleasure/Enjoyment | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Being touched (Emotion)/Sympathy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Satisfaction/Happiness/Joy | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Feeling(s)/Gratitude | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hope | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interest/Enthusiasm | 1 | 1 | −1 | 2 | 2 | −1 | 4 | 1 | 2 −1 | −1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Longing | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pride | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relaxation/Serenity/Relief | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anger | −1 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety | 1 | 1 −1 | 1 | −1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | −1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boredom/Disgust | −1 | 2 | 2 | 2 −1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Desperation (Despair)/Disappointment | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dissatisfaction/Sadness | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fear | 1 −1 | 1 −1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Guilt/Shame | 1 | 1 | 1 −1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contempt/Hatred | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 8 −1 | 2 −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Tension/Stress/Irritation | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lie/Deceit | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 65.5% negative | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31% irony | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3.5% positive | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llorca-Asensi, E.; Sánchez Díaz, A.; Fabregat-Cabrera, M.-E.; Ruiz-Callado, R. “Why Can’t We?” Disinformation and Right to Self-Determination. The Catalan Conflict on Twitter. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100383

Llorca-Asensi E, Sánchez Díaz A, Fabregat-Cabrera M-E, Ruiz-Callado R. “Why Can’t We?” Disinformation and Right to Self-Determination. The Catalan Conflict on Twitter. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(10):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100383

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlorca-Asensi, Elena, Alexander Sánchez Díaz, Maria-Elena Fabregat-Cabrera, and Raúl Ruiz-Callado. 2021. "“Why Can’t We?” Disinformation and Right to Self-Determination. The Catalan Conflict on Twitter" Social Sciences 10, no. 10: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100383

APA StyleLlorca-Asensi, E., Sánchez Díaz, A., Fabregat-Cabrera, M.-E., & Ruiz-Callado, R. (2021). “Why Can’t We?” Disinformation and Right to Self-Determination. The Catalan Conflict on Twitter. Social Sciences, 10(10), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10100383