Abstract

This essay reconsiders the photomontages that Martha Rosler began making in the late 1960s to protest the war in Vietnam. Typically understood as a means of protest against the spatial mechanics of domination—against the mediated production of the difference between the home front and the war front or the “here” and “there” that drives modern warfare—the photomontages, this essay argues, also engage the temporal politics of protest. The problem of how to be “in time,” “to be present,” the problem that frames street photography and its critical history, is at the center of this essay and, it contends, Rosler’s protest. By drawing out this critical framework, this essay addresses the still-urgent questions that Rosler’s photomontages pose: When is the time of protest? Does protest happen now? Is there still time for protest?

We are the words of others.Jean-Luc Godard, La Chinoise, 1967

1. In the Street

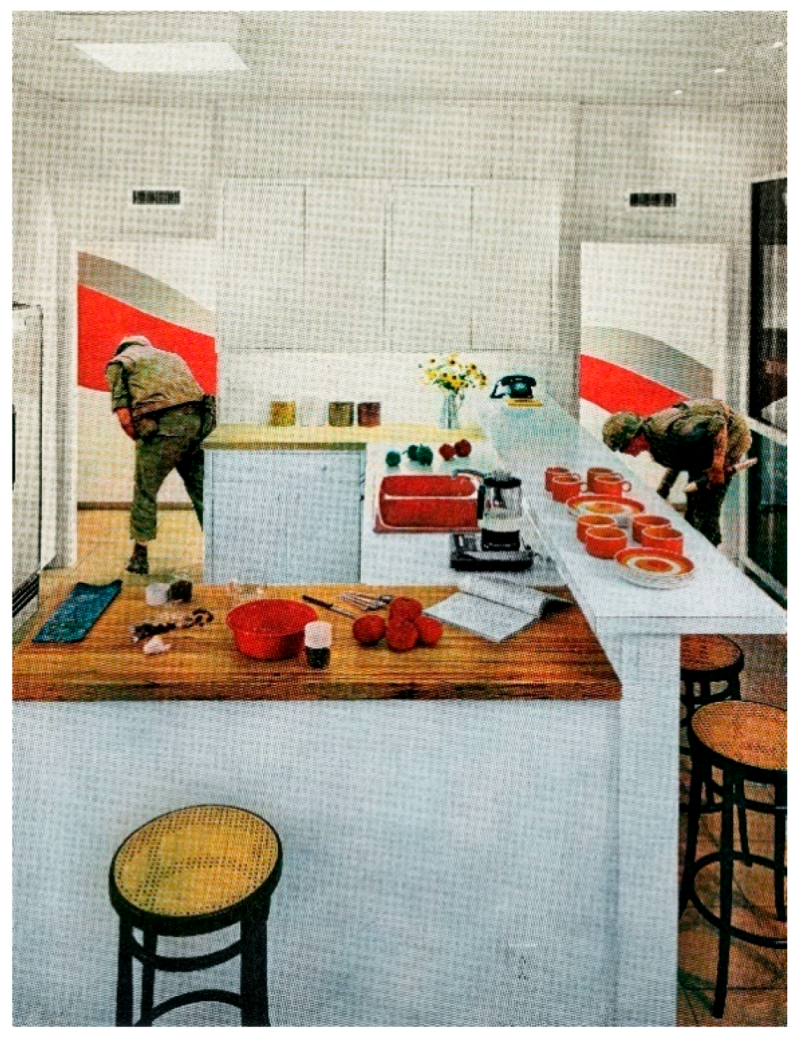

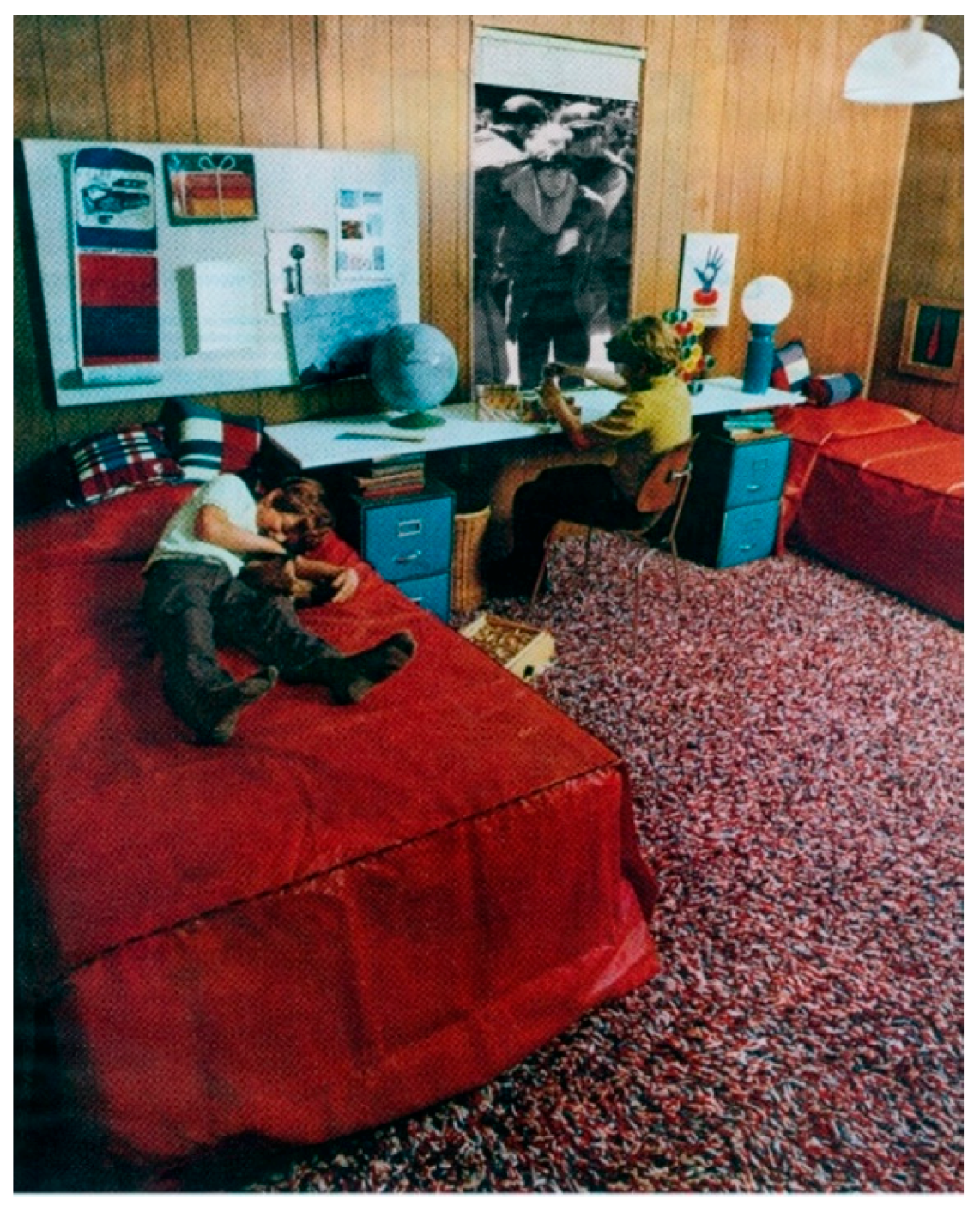

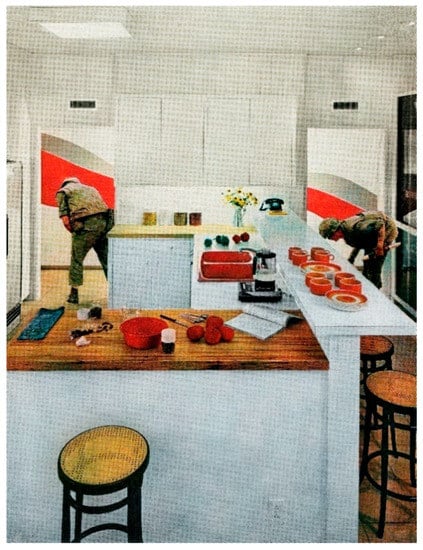

I want to end this special issue in the street. To do so, I turn to a set of images that seem to be far removed from the genre of street photography: the photomontages Martha Rosler began making in the late 1960s to protest the war in Vietnam. Working at home, Rosler cut glossy images of the figures of war—soldiers, civilians and protesters—from back issues of Life magazine and pasted them into scenes of domestic comfort that had been culled from contemporary design magazines, such as House Beautiful. In one, two American soldiers lurk and load guns in a bright, white kitchen; in another, a spectacled protester peers into (or blocks the view from) a boys’ bedroom (Figure 1 and Figure 2). With this simple act of cutting and pasting the news, Rosler reframed the way in which the war in Vietnam was being framed.1 “I was trying to show,” she later explained, “that the ’here’ and the ‘there’ of our world picture, defined by our naturalized accounts as separate or even opposite, were one” (Rosler [1994] 2004, p. 355). The war in Vietnam, Rosler insisted, was also taking place “here”—at home. It belongs to that frame.

Figure 1.

Martha Rosler, Red Stripe Kitchen, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c. 1967–1972. Photomontage. © Martha Rosler/Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

Figure 2.

Martha Rosler, Boys Room, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c. 1967–1972. Photomontage. © Martha Rosler/Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

Now known as the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–1972), Rosler’s photomontages were conceived of as protest flyers.2 Neither dated nor signed, they were xeroxed, piled up and carried into the street (Rosler 2019, p. 352). Mobile and mobilized, they were moved between hands. Presumably, they were crumpled up and folded as well as shoved into pockets. They were also, most likely, dropped and stepped on, swept up and away by the movements of bodies marching and working together to produce another image of war—of dissent and solidarity. It is this image or, to be more exact, the desire for it that I want to consider in the closing pages of this issue. With Rosler’s photomontages “in hand,” I ask: How is the social made to appear in the street? And, importantly, why has it been made to disappear from most accounts of the House Beautiful series? The figural space of the home, not the social space of the street, sits at the center of most studies of Rosler’s photomontages.3 My answers to these questions do not, as might be expected, hinge on the need to differentiate between art and activism. In fact, in what follows, I will insist that the institution of art is the frame through which Rosler’s protest is made legible—made to read as a protest. My concern, in other words, is not with being in the street. It is with how “being in the street” has come to be framed, photographically or otherwise, as being “there” or present—as being “unframed.” How, I ask, has this frame been made to go unseen, and, accordingly, how can we be made to see it? If I ask these questions now, as the streets have, once again, become a site of active protest, as protests against anti-Black violence come to make up the social space of the street, it is because it is necessary to recognize that the frames through which we see and write cannot be swept away, refused.4 They are and must be repeated. This is the work of Rosler’s photomontages. It is also the process through which the social is made. It is made collaboratively and with the resources at hand. “Bring the war home,” after all, is not Rosler’s refrain.5 It was in the news. It was heard in the streets. It was said in order to be shared and repeated. The need or compulsion to repeat sits at the center of this essay and, I will argue, Rosler’s protest.

2. In the Frame

1967, the year that Rosler began making her flyers, was also the year that she claims to have stopped painting. “When I understood what it meant to say that the war in Vietnam was not ‘an accident,’ I virtually stopped painting and started doing agitational works” is how Rosler put it in the mid-1990s (Rosler [1994] 2004, p. 353). Rosler did not stop painting. She continued to paint large abstract canvases until the early 1970s. In 1971, she applied to the MFA program at the University of California, San Diego as a painter.6 Rosler’s origin story is important, though not because it seeks to situate the photomontages as something other than art—as activism or propaganda. It is important because it does not. With her statement, Rosler gives her decision to protest a very specific institutional frame: the apotheosis of American formalism. Like many of her contemporaries, Rosler “stopped” painting at the very moment that painting was being championed by a cadre of critics and art institutions seeking to shore up a waning belief in art’s autonomy.7 In 1964, after all, Clement Greenberg had coined the term Post Painterly Abstraction to describe a way of working with paint that seemed to—was marketed to—fulfill his claim that “visual art should confine itself exclusively to what is given in visual experience, and make no reference to anything given in any other order of experience” (Greenberg [1960] 1995, p. 91). Now or finally, the canvas appeared to be nothing more, nothing less, than what it was: a flat repository for the staining or soaking of pure color.8

Of course, it was not painting as such that mattered. It was an allegiance to the immediacy of seeing, to the “all-at-onceness” of a picture. Michael Fried conveniently canonized modern art in these terms the same year that Rosler claimed to have virtually stopped painting. Readers of the summer 1967 issue of Artforum learned that “Presentness is grace” (Fried [1967] 1998, p. 168). The closing line of Fried’s now-seminal critique of minimalism, “Art and Objecthood,” these three words frame his insistence that art—or, to be more exact, “good” art—should not take time. Its apprehension must be immediate—present. With the work of the sculptor Anthony Caro in mind, Fried put it thus:

“Good” art, according to Fried, is grasped, like a picture, all at once, instantaneously and as a whole.9 It was not painting but the picture that mattered; what mattered, in other words, was the desire for seamlessness—for art’s “perpetual creation of itself.” “[M]y ambivalence about the matter of the telos of art persists,” Rosler explains in her recounting of her decision to virtually stop painting. “The question,” she continues, “was to what degree art was required to pose another space of understanding as opposed to exposing another, truer narrative of social-political reality” (Rosler [1994] 2004, p. 353). Agitational work activates and recognizes what calls for presentness necessarily repress: bodies moving in space, in the gallery as well as the street—bodies becoming and being social.It is this continuous and entire presentness, amounting, as it were, to the perpetual creation of itself, that one experiences as a kind of instantaneousness, as though if only one were infinitely more acute, a single infinitely brief instant would be long enough to see everything, to experience the work in all its depth and fullness, to be forever convinced by it.(Fried [1967] 1998, p. 167; emphasis in the original)

The telos of art, too, persisted—and spread. 1967 was also the year that John Szarkowski applied it to photography. I am referring to the New Documents exhibition, which opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) that year. Showcasing the work of the two photographers who would come to define the genre of street photography, Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, as well as the work of Diane Arbus, the exhibition promptly confirmed the supposition that “good” art should dispense with the social and the experiential. To quote from the now much quoted wall text that introduced the exhibition,

New Documents certainly privileged the personal and private over the social. Or, as Rosler argues in an essay she penned in 1975 on Friedlander’s work and the histories of modernism that the work was being made to frame, the exhibition celebrated photography that is “disinterested” (Rosler [1975] 2004, p. 114).10 Surely a reference to Immanuel Kant’s aesthetics or to the neo-Kantianism propping up Greenberg’s strident and celebrated critique of bodily presence, Rosler sums up her account, which was also published in the pages of Artforum, as follows: Friedlander is present in his photography, but his photographs do not take time. “Art making here,” she writes,In the past decade a new generation of photographers has redirected the documentary approach toward more personal ends. Their aim has been not to reform life, but to know it. Their work betrays a sympathy—almost an affection—for the imperfections and frailties of society. They like the real world, in spite of its terrors, as the source of all wonder and fascination and value—no less precious for being irrational.(Szarkowski 2017, n.p.)

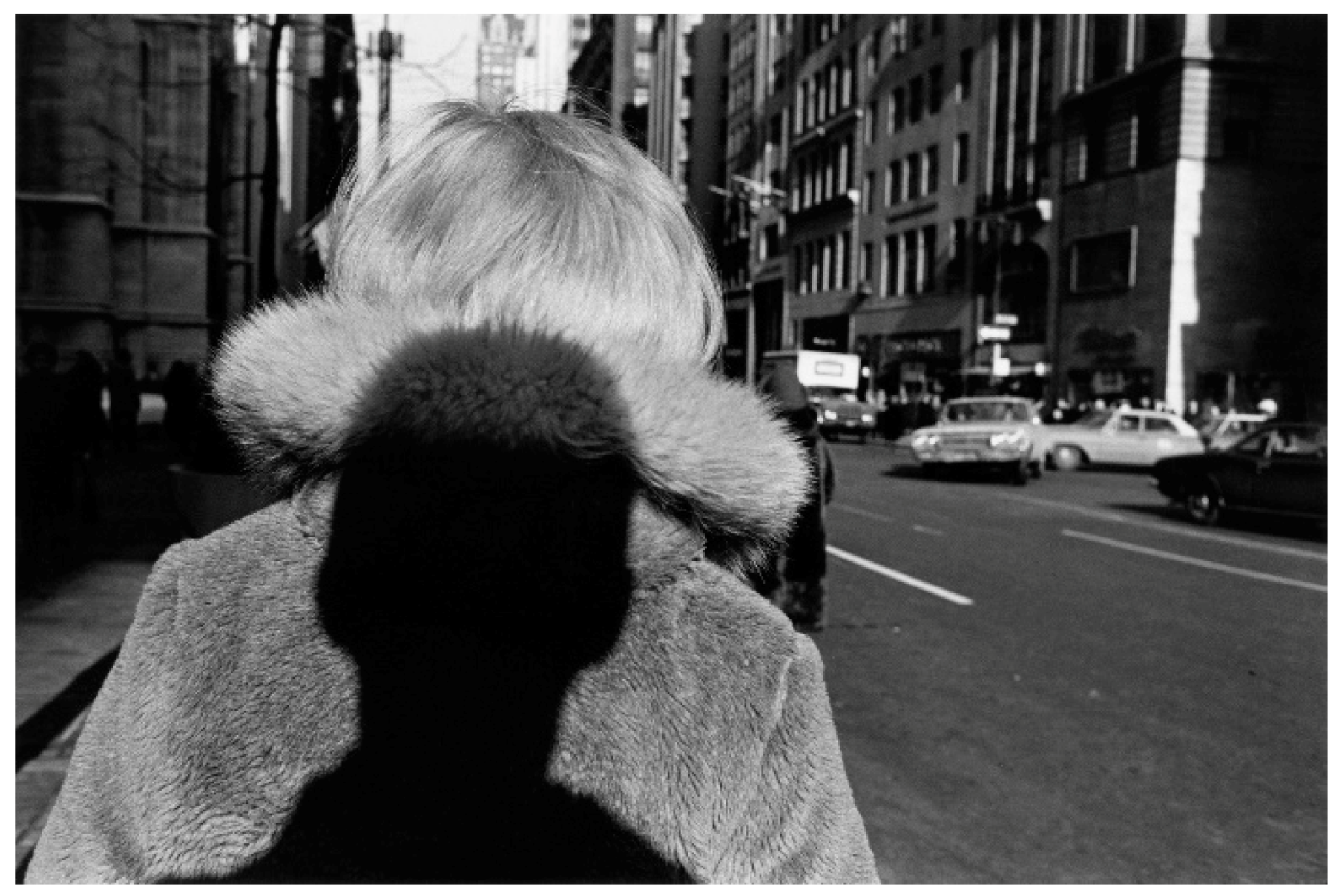

In Friedlander’s work, Rosler contends, there is nothing but a relay of frames: mirrors and windows, reflections and shadows and so forth (Figure 3). Photography’s double is doubled. This, Rosler suggests, is an example of modernism’s self-reflectivity, its grasping for autonomy, perversely canonized through the most social of art forms: photography.entails a removal from temporal events, even though the act of recording requires a physical presence, often duly noted. Friedlander records himself passing through in a car, standing with eye to camera, and so on, in widely separated locations, always a nonparticipant.(Rosler [1975] 2004, p. 118)

Figure 3.

Lee Friedlander, New York City, 1966. © Lee Friedlander/Courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Luhring Augustine, New York.

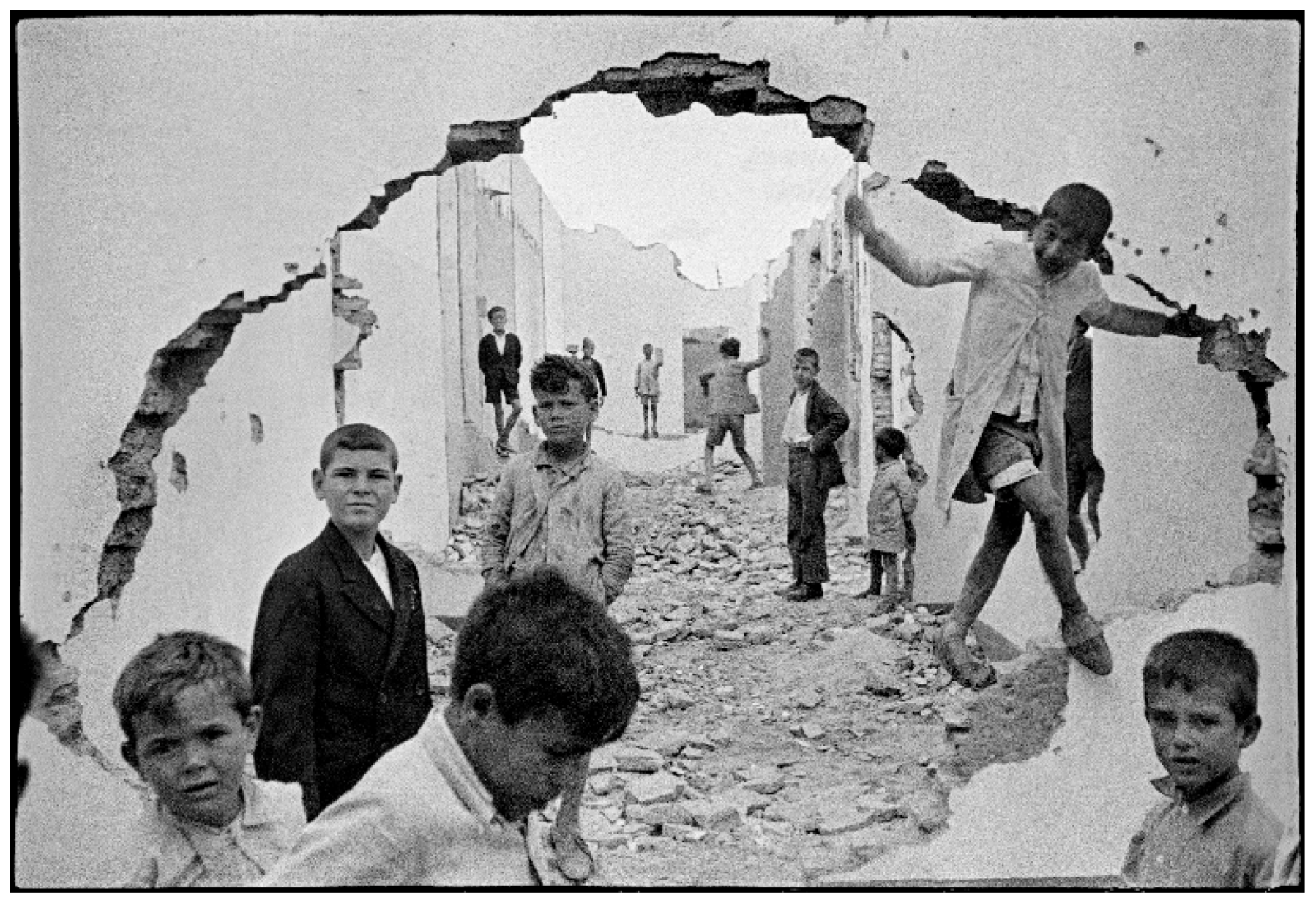

If I draw out this history of American formalism, it is not so that I can take a side. I am not interested in championing the “political” work that Rosler and her contemporaries were doing “with” photography in the wake of the New Documents exhibition over or against the street photography of Friedlander and Winogrand—or even the much-dismissed voyeurism of Arbus.11 Rather, I am interested in how this binary represses the history of photography written in its name. In other words, if Rosler’s critique of Friedlander is important, it is not because it confirms the so-called (political) limits of his work. It is because it recognizes the limits of the frame to which the work has been subject. In the late 1960s, Szarkowski not only or merely applied formalism to photography. He championed photography as a means, perhaps even the means, of shoring up a steadily waning modernism. Significantly, Szarkowski’s source of inspiration was not Greenberg’s much-touted criticism—or not solely.12 It was the work and writings of Henri Cartier-Bresson (Figure 4). In the early 1960s, Szarkowski celebrated the French photographer’s call to “distill” the essence of photography—to, as it were, capture the “decisive moment” (Cartier-Bresson 1952, n.p.). To quote the now-famous lines from Cartier-Bresson’s introduction to the much-celebrated eponymous volume, The Decisive Moment (1952), “photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression” (Cartier-Bresson 1952, n.p.). Photography is seamless; it is an act of “perpetual creation.” Or, at least, this is how Szarkowski imagined it. “The thing that happens at the decisive moment,” Szarkowski argues in an attempt to correct for what he took to be a misunderstanding of the phrase, “is not a dramatic climax but a visual one.” “The result,” he concludes, “is not a story but a picture” (Szarkowski 1966, n.p.).

Figure 4.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Spain, Seville, 1933. © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos.

It could easily be argued that Szarkowski, too, got it wrong. Cartier-Bresson was a reporter; he made stories for Life and numerous other illustrated weeklies.13 However, this correction neutralizes the importance and timeliness of Szarkowski’s (and, perhaps, Cartier-Bresson’s) charge. It neutralizes its political work. In the work and writing of Cartier-Bresson, Szarkowski discovered a way to knit photography into the story of modern art’s ban on taking or telling time.14 More to the point, he discovered a way to situate street photography, not abstraction, as the apotheosis of modernism. Working in the street, “on the run” or “on the sly,” à la sauvette, to borrow the phrase used in the title of the French edition of The Decisive Moment, was also deemed unmediated.15 “Above all, I craved to seize, in the confines of one single photograph, the whole essence of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes” was how Cartier-Bresson described his work as well as his desire to create a seamless and solitary image (Cartier-Bresson 1952, n.p.; emphasis added). “I believe that, through the act of living, the discovery of oneself is made concurrently with the discovery of the world around us,” he concluded, adding, “A balance must be established between these two worlds—the one inside us and the one outside us” (Cartier-Bresson 1952, n.p.).16 Thus, if I draw out this history of American formalism, it is not so that I can take a side between “good” and “bad” politics. Nor, following Abigail Solomon-Godeau, is it to recognize that there would be no street photography without the institution of art (Solomon-Godeau 2017). Rather, it is to insist that the institution of art invented street photography as a practice that could strip photography of the social. This, I am suggesting, is where Rosler began her agitational work. She did not begin in the street. She began with the history of photography. Or, to be more exact, she began with the refusal of photographers and historians of photography to acknowledge that photography had one.

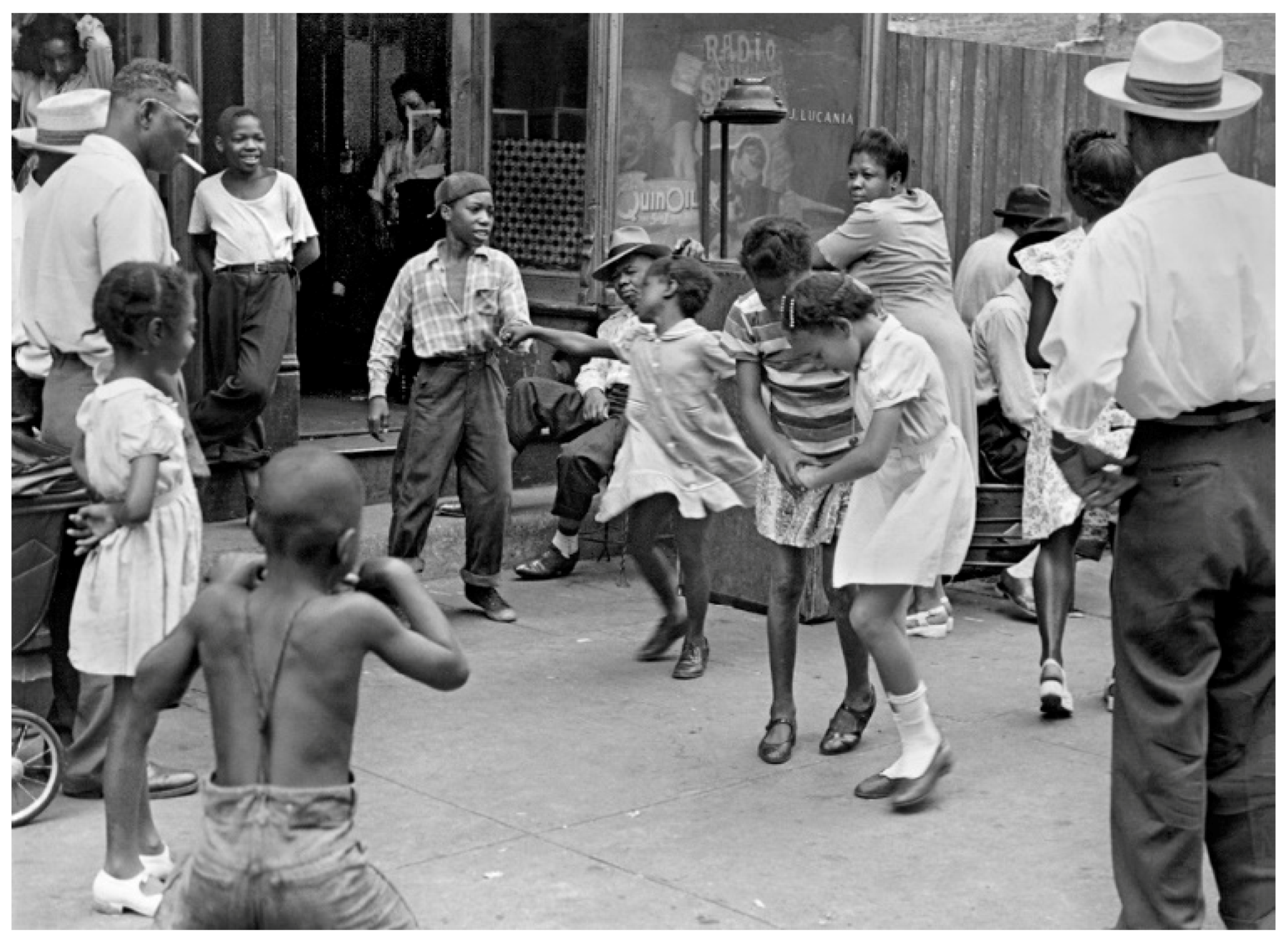

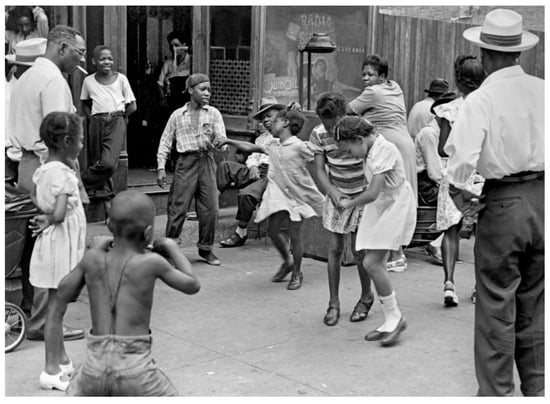

Attending to this refusal is exactly what Rosler did in the early 1960s, before she “stopped” painting and began making the flyers. In 1964, while studying at Brooklyn College, Rosler began documenting the streets of her native Brooklyn and New York’s Lower East Side with a camera (Figure 5). Notably, she used the darkroom run by the students of Walter Rosenblum, one of the founding members of the Photo League, a school and exhibition space opened in 1936 to train young and predominately left-leaning photographers (Buchloh 1998, p. 24). Rosler’s early photographs, including those of children playing in the street, recall the social documents of that school—and do not. This is because unlike many League photographers, such as Helen Levitt and Morris Engel, Rosler did not work in the street (Figure 6). She drove by. Rosler shot her early street photographs from the window of a car. “The mediation of the vehicle,” she notes, “represents my presence, the walker in the city, in this case, the rider” (Nesbit and Obrist 2005, p. 14). Rosler was not there. Her presence is represented. It is mediated through another frame or another technology for framing, in addition, that is, to the camera.17 In her early photographic work, Rosler did not return to “the past” in order to recover what Szarkowski was working so hard to repress—namely, documentary. Hers is not a project of reclamation. Staying in time, she worked on the institutional frame: on photography and the writing of its history.

Figure 5.

Martha Rosler, Untitled, from the Downtown Series, c. 1964. Gelatin silver print, 20.3 by 25.4 cm. © Martha Rosler/Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

Figure 6.

Helen Levitt, New York, c. 1940. © Helen Levitt Film Documents LLC. All rights reserved. Courtesy of Thomas Zander Gallery.

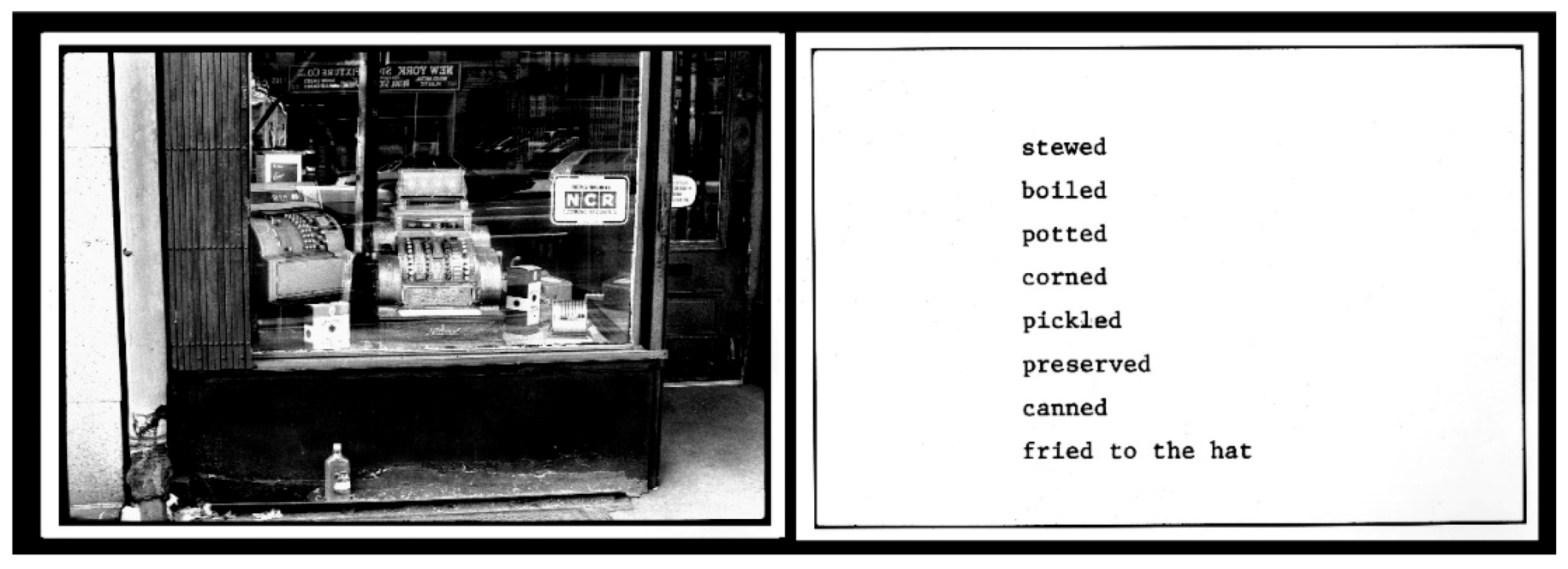

Rosler, in fact, never began her work in the street, not even when she walked down the Bowery in New York City taking photographs of the storefronts and sidewalks littered with empty bottles and other urban detritus. These photographs, twenty-one of which make up the twenty-four panels composing The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974–1975), are not of the places they represent (Figure 7). Though Rosler did work in the street, she once again mediated her presence. The photographs of the storefronts and sidewalks are, to borrow Rosler’s word, “quotes” (Rosler [1981] 2006, p. 88). They are remakes. It is often assumed that Rosler’s photographs quote those of Walker Evans, the planar shots of storefronts and shop windows that Evans made in the mid-1930s, at the height of the Great Depression. These photographs had recently been on view at MoMA. In 1971, Szarkowski curated an Evans retrospective, Photographs by Walker Evans, and canonized him as an artist with an “unconventional” style (Szarkowski 1971, pp. 11–13). However, Rosler’s photographs confound the search for a source—or origin. They are made to eschew teleology. This is because the so-called father of American documentary, Evans, was also quoting. In the 1930s, he was remaking the photographs that Eugène Atget had made of the streets of Paris at the turn of the twentieth century. Rosler, as she puts it, was quoting “a mode of address” (Nesbit and Obrist 2005, p. 24). She was quoting the very refusal to be present, which, Evans made plain, is the origin of documentary.18 Atget, after all, famously refused to give his photographs his name, to take credit for his work (Nesbit 1994, pp. 1–3). In his frames, nothing, as Szarkowski had imagined it, could be or was personal.19

Figure 7.

Martha Rosler, from The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, 1974–1975. Two of forty-five gelatin silver prints on board; each diptych panel measures 25.4 cm × 55.9 cm. © Martha Rosler/Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

Likewise, nothing is personal in The Bowery. Rosler did not work with her photographs, nor, for that matter, did she work with her words. With The Bowery, Rosler did not settle on a photograph or even several of them to represent that site as a social space and a representation. She took photographs in the street, photographs that are purposely devoid of those men known as the Bowery “bums,” and she collated a series of words that had come to describe their social standing—their status as drunks. “Stewed,” “boiled,” “potted,” “corned,” “pickled,” “preserved,” “canned,” and “fried to the hat” are some of the adjectives and phrases that fill the frames making up The Bowery. These words are vernacular. They are found and common. The Bowery, as Steve Edwards argues in his extended study of the work, is “blank” (Edwards 2012, pp. 15–18). It is just a frame. Like the photographer, the traditional subject of street photography—“the bum,” the “unemployed” and so forth—is also not present. Instead of “life caught unaware,” The Bowery offers viewers the frame that promises to catch life unaware: street photography. To quote Rosler once more, “I wanted to highlight the idea that lived experience and social relationships transcend the categories that frame them, including art. These frames therefore must always call attention to themselves as frames” (Nesbit and Obrist 2005, p. 20). In short, The Bowery represents what is missing from much of the work that has come to be characterized as street photography: the street. This is not because it is not there—either in the background or figured as the ground of representation, as in, for example, Friedlander’s New York City (see Figure 3). It is because it had not been accounted for as a social space mired in representation. The real world, “in spite of its terrors,” as Szarkowski put it, is approached immediately, personally and as “the source of wonder and fascination and value.”

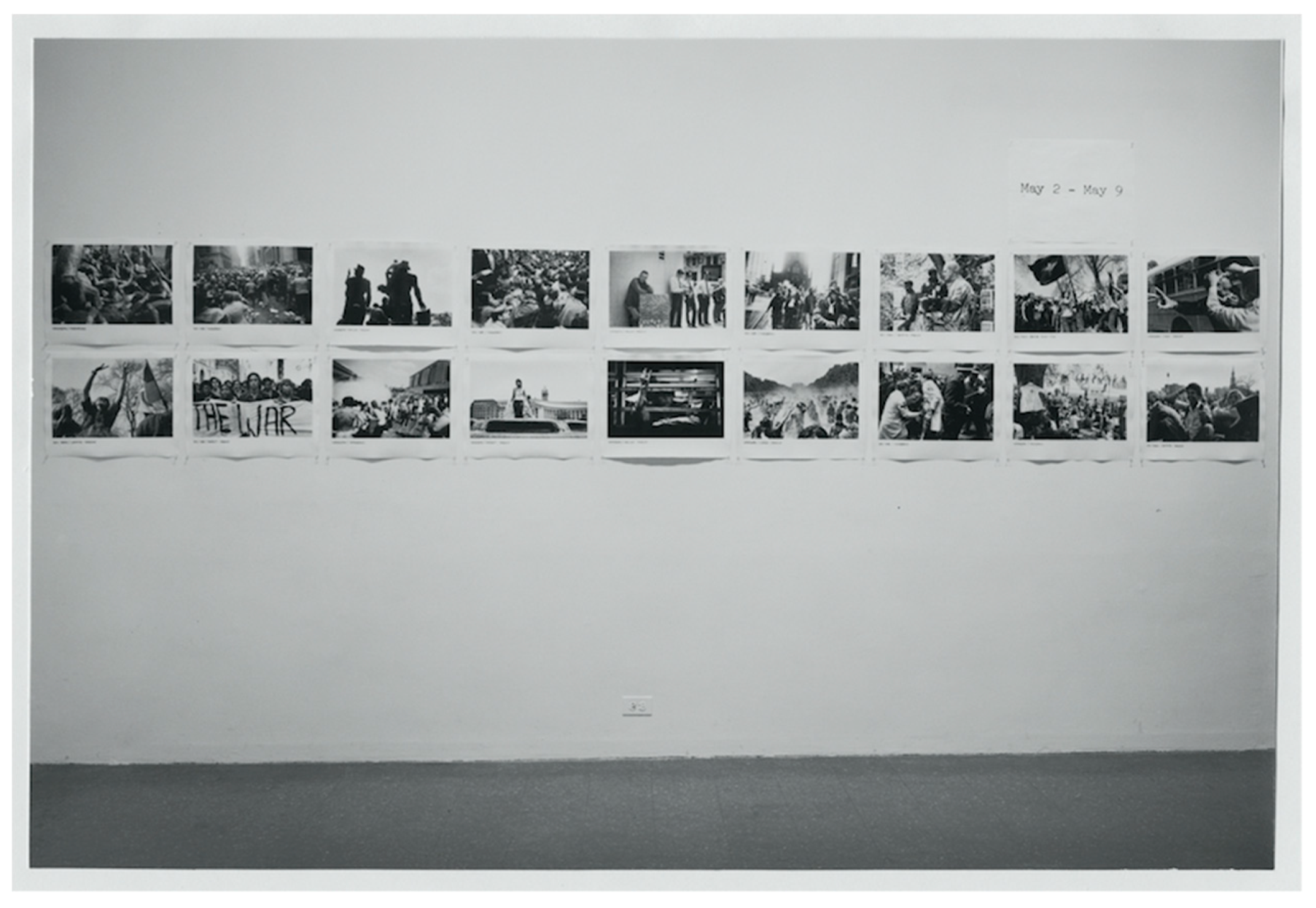

The world’s terrors, however, were hardly ignored. In fact, it could easily be argued that they were simply repressed. Like the street, they were simultaneously present and absent in the frame. A case in point is Szarkowski’s lesser-known—and hurried—exhibition Protest Photographs (Figure 8). Opening on May 23, 1970, within weeks of President Richard Nixon’s decision to extend the terror in Vietnam to Cambodia and the eruption of protests across university campuses, from Kent to Jackson State, the exhibition lasted twelve days. The logic of the exhibition’s short run was borne out in its program: the fifty-seven photographs on view were records of protests that had taken place two weeks earlier, between May 2 and May 9. This was protest now. John Filo’s photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio kneeling before the body of Jeffery Miller during the May 4 antiwar demonstration at Kent State found a place on the wall, as did several photographs that Winogrand had made of protests against that violence, including Kent State Demonstration, Washington, D.C. (1970).20 Szarkowski’s bid for immediacy, notably, exceeded the fact that the protests on record had just happened or were, perhaps, still happening. The day before the exhibition opened, many New York-based artists had called an Art Strike Against Racism, War and Repression.21 Unmounted and unframed, the photographs were push-pinned to the wall, as if or because they were meant to be read as “hot off the press,” as news (Phillips 1982, p. 60).

Figure 8.

Installation view of Protest Photographs, Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 23 to June 2, 1970. Gelatin silver print, 15.9 cm × 24.1 cm. Photographer: James Mathews. © The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Object Number: IN929.1. New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). © 2020. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

Protest Photographs was timely. It was also wholly out of time. It made protest legible formally, as a picture. This is not simply because each photograph was printed at 16 × 20 inches with a one-inch border, the conventions typical of the exhibition print, as Simon Constantine notes in his contribution to this special issue (Constantine 2019, p. 6). It is because despite this convention, the photographs remained unframed. They were stripped of their pages, or, as was the case with the Winogrand photographs, they were never meant to have them. Protest Photographs neatly and purposefully defused the relay of information, the delay that makes news, news and social. It defused the possible or potential stories.22 The lesson of Protest Photographs is that protest—or life in the street—is happening, must happen, in the now. This is also the endgame of assigning art a telos. It kills time by refusing to acknowledge time’s construction. Time simply is. History simply happens. With her photomontages, Rosler protested against this frame. She stopped making pictures—paintings or photographs—once she “understood what it meant to say that the war in Vietnam was not ’an accident.’” She protested by attending to time’s construction on the page or as the news—as accidental or inevitable. This is the work of photomontage. The cutting and pasting of readymade images into a second order of representation makes time and kills the picture. Simultaneously undoing and redoing the means by which the news is made, photomontage defuses photographic presence and the present.23

3. On the Screen

I insist on the centrality of the legacy of American formalism to Rosler’s protest for several reasons, not the least of which is to acknowledge what Rosler recently called its “death grip.”24 This brand of formalism persisted or, as I am suggesting, still lingers, especially with respect to the writing of the history of photography. As many of the essays in this issue argue, photography’s history still remains largely unmediated. However, my concern is not simply to acknowledge the persistence of formalism’s telos for and through our histories of photography. It is to recognize that failing to do so unwittingly reproduces it. Stated differently, being “in” time does not require being “there”—being in the street or in the crowd. It requires recognizing that the categorization of time as presence is simply another frame, another mediation. Courting time, in short, is never enough. Calls for presence or being “in” time do not, cannot, debunk the claims or convictions of presentness or timelessness. They simply produce another frame: one in which protest is made to appear as if it is already happening, as if now is necessarily or evidently “the time of protest.” It is also necessary to protest against this construction of time, against a construction of time that forestalls the need to historicize. By this, I do not mean the need to account for the specificity or urgency of a given protest. Rather, I mean the need to acknowledge the ways in which specificity and urgency are produced in order to make it seem as if history is bound to happen or is inevitable. If this is true, protest is not only unnecessary or futile; it is both criminalized and normalized.25

With this frame in mind, I turn to another origin story—to another of Rosler’s accounts of why she began making agitational work. Written in 2019, this story begins at home, in bed, a site figured in three of the twenty photomontages that make up the House Beautiful series (see Figure 2). Rosler begins:

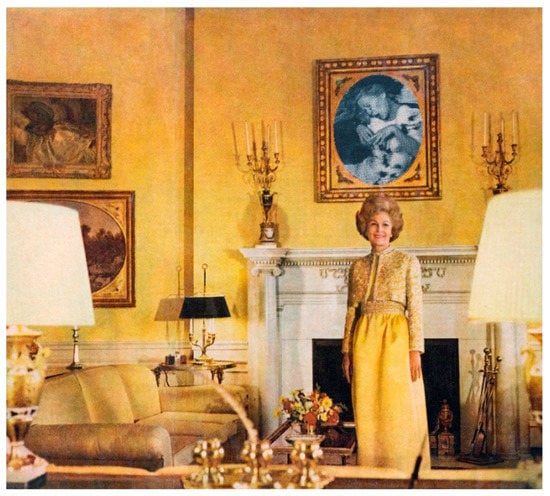

The war in Vietnam, Rosler notes, was not only lived with at home—flipped through in the pages of magazines and seen on the television screen. It was slotted into the rhythms of the working day, into the temporal routines of those not physically on the front. Media or mediation, in other words, not only made the war appear as if it was taking place far away, in an unfamiliar place. It made it easy to consume, day after day after day. As the British media theorist Stuart Hall argues in his now-influential discussion of the organization, dissemination and production of the news as news, news photographs are not designed to provide new knowledge. They are designed to provide readers of the news with the means to recognize the world as they “have already learned to appropriate it” (Hall 1972, p. 82). The news is printed so that it can be slotted into place, so that it can corroborate those narratives that, as Rosler puts it, made the war in Vietnam—or any war, for that matter—seem “accidental.” After all, the “image of war” sutured into a gilded frame in the photomontage now known as First Lady (Pat Nixon) is not in fact a photograph from the front (Figure 9). Pulled from the pages of a Life exposé on Arthur Penn’s much-heralded gangster film Bonnie and Clyde (1967), it simply reads as such. In this frame, the bullet-ridden body of Bonnie Parker, played by Faye Dunaway, appears to be—comes to represent—a Vietnamese woman.26I remember dawdling in bed one morning and hearing the news that General Westmoreland wanted to increase troop strength in Vietnam to five hundred thousand men. “That’s a half million men! A real invasion!” I said out loud. I was startled even to imagine it. By then the war was not only being discussed on the radio and television news; the war, complete with battlefield film, was also broadcast on TV at dinner hour. Critics began to refer to the war as the first “living-room war,” though to me it was the dinnertime war.(Rosler 2019, p. 349)

Figure 9.

Martha Rosler, First Lady (Pat Nixon), from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c. 1967–1972. Photomontage. © Martha Rosler/Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

In her photomontages, Rosler “brings the war home” by repeating the codes of mediation that make the news “news,” that produce presence. The flyers, in other words, also quote “a mode of address.” This quoting, the redoubling of the rabbit hole of reference that is the news, is, perhaps, most perverse or disturbing when it comes to the representation of war. Jean-Luc Godard suggested as much in the many films he made about how the desire to go to war is produced through the dissemination of photographic images, including Les Carabiniers (The Riflemen) (1963). The tale of Michel-Ange and Ulysse, two peasants conscripted to war by a letter from the king, the film plays the deprivations of reality against the riches of representation. At war, the king’s representatives tell the duo, anything goes. Anything or anyone, for that matter, is up for grabs—is there and theirs for the taking. Lands, herds, houses, palaces, cities, cars, movies, dime stores, airports, and “ladies of the world” are available, the representatives announce in a scene that seems to go on for far too long and is played out on the screen. Coming to the end of this very long list of war’s potential prizes, one envoy pulls a photograph of a pinup model from his jacket pocket. This body, or, to be more exact, a body just like this one, will be available to these men (to men) not despite but because it is a representation. Michel-Ange, in fact, cannot, has not learned how to, tell the difference between reality and image. At the cinema, he jumps up from his seat and rushes to the screen. He starts to grope the projection of the woman bathing on it. He tries, desperately, repeatedly, to jump or join in.

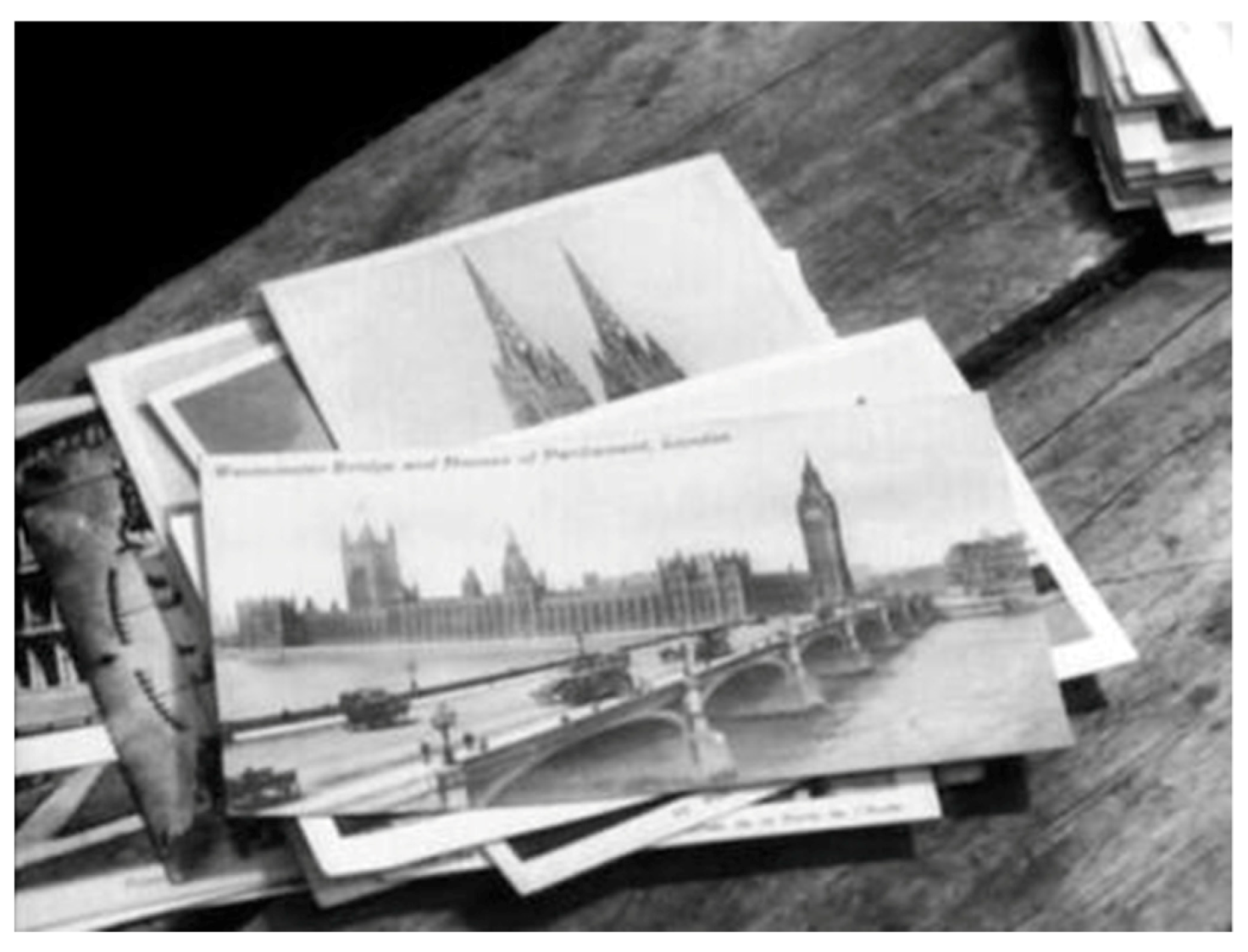

Les Carabiniers was heavily criticized when it was released. The film makes a mockery of war, several reviewers argued, and not simply because of the buffoonery of the film’s protagonists. It is because it generalizes warfare (Patenberg 2015, pp. 181–82). This is simply war. The film offers no timeline; it provides no specificities about where the war represented on the screen is taking place. The use of found footage from unnamed “past” wars compounds as much as confirms Godard’s desire to generalize. Simply put, in Les Carabiniers, Godard refuses reference. This war, fought for “the king,” takes place anywhere and at any time. These generalizations are pushed to the extreme in the film’s closing scenes, when Michel-Ange and Ulysse return from the front with their riches: a suitcase full of postcards (Figure 10). These riches are not empty signs—evidence of the world or war becoming image.27 They are a means, a “method,” as Michel-Ange and Ulysse tell Cléopâtre and Vénus, the two women who stayed at home, waiting for the men to return with war’s prizes. Neatly organized into discrete categories, including monuments, transportation, and animals, the postcards are the means of possession. They are the means by which history has been and can be written, has been and can be made to unfold in time. After all, as Michel-Ange and Ulysse flip through the cards, they repeat the organization of time as history, as the movement or development from antiquity to modernity. The monuments of Greece precede those of Rome, to be followed by the monuments of modernity and so forth. The time of war is played out through representation and on the screen. The beat of military drums syncopates this scene. It is not the sound of war but of war films. In Les Carabiniers, war is neither “here” nor “there” nor now. As in the First Lady (Pat Nixon), the war in Vietnam is only represented.28

Figure 10.

Still from Les Carabiniers, dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1963.

Godard’s films, as Steve Edwards notes, functioned as a “lodestone” for many American artists working through and against the institutionalization of American modernism in the 1960s (Edwards 2012, p. 94). The French filmmaker’s interrogation of the relationship between reality and representation, of their imbrication, Edwards explains, made plain that work “on the image” was an urgent ideological task. Key here is Godard’s commitment to montage, his commitment to acknowledging that his films—that all films—are made. “There was an emphasis on seams-out film-making rather than an obfuscatory bourgeois seamlessness” is how Rosler puts it in her discussion of the place or role of Godard’s films in her formation as an artist in the 1960s (Ribalta 2015, p. 81). Like the joins in her photomontages, which are visible, the “seams” in Godard’s films disrupt their easy consumption.29 Godard’s films acknowledge their construction as films. They also, Rosler notes, acknowledge that acknowledgement (Ribalta 2015, p. 80). Gilles Deleuze offers the best account of this double work in his analysis of the invention of what he calls the “time-image” in postwar cinema. “Godard’s strength,” Deleuze explains, “is not just in using this mode of construction in all of his work (constructivism) but in making it as a method which cinema must ponder at the same time as it uses it” (Deleuze [1985] 1997, p. 179). There is no “out-of-field” in Godard’s films, Deleuze argues (Deleuze [1985] 1997, pp. 180–81). There is nothing outside of the frame, or, as I am suggesting is the case with Rosler’s photomontages, nothing is out-of-time. As in the media, time—the time of war, the time of peace, the time of protest—is what is being made.

There is no better example of the metacritical work of montage than Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere) (1976), a film about its own making. As Godard announces in the film’s opening sequence, the making of Ici et ailleurs began in 1970, when al-Fatah, the largest faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, commissioned the Dziga Vertov Group, a collective formed by Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin, to make a film about their struggle to reclaim land occupied by Israel in 1967.30 Shot in the refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon and Syria, Jusqu’à la victoire (Until Victory), as the film was to be called, was never finished. Production was halted with two-thirds of the film complete following the Black September massacres of 1970. As Godard states in Ici et ailleurs, the terror carried out by King Hussein’s troops killed many of the film’s actors. In 1974, Godard collaborated with Anne-Marie Miéville to make a film about the difficulties of making a film about a revolution taking place “elsewhere”: Ici et ailleurs. In this film, footage of refugees conducting drills, reciting slogans and planning maneuvers is combined with scenes of a French working-class family working at home, eating dinner and watching television. The image of armed struggle “elsewhere” can only be seen, Ici et ailleurs suggests, through an acknowledgement of the mediation of that struggle “here”—in France. It is “too simple and too easy to simply divide the world into two,” the film announces as found footage of US President Nixon and photographs of the victims of the many wars taking place “elsewhere,” including in Vietnam, are stitched together on screen. A film about a failure to make a film about a revolution “elsewhere,” Ici et ailleurs doubles as an indictment of the assumption that the so-called Third World revolutions do not also—or necessarily—take place “here.”

Acknowledging the mediation of mediation is also the work of Rosler’s flyers. As I quoted Rosler in the first page of this essay, “I was trying to show that the ‘here’ and the ‘there’ of our world picture, defined by our naturalized accounts as separate or even opposite, were one.” The similarity between the flyers and Ici et ailleurs is important.31 It registers the perverse temporality of mediation and influence. This is not simply because Rosler’s photomontages came “first.” It is because Godard was both a model and a copy for Rosler. His films, she notes, “reawakened” her interest in agitprop traditions. “I didn’t know Dziga Vertov’s work, which Godard took as his model by the early seventies, but I certainly saw what [Sergei] Eisenstein was interested in and that montage constituted the work,” she explains, adding, “By the end of the sixties, nothing was more important than film for what I and many other people were doing” (Buchloh 1998, p. 31). And, as I have been arguing in these pages, what she and other people, including Allan Sekula and Fred Lonidier, were doing was establishing a critical history of photography. There was none in the 1960s. In Rosler’s words,

My point here is not—or not simply—that a critical history of photography emerges out of or through the film screen. Walter Benjamin argues this in the early 1930s, with his nod to the generalizations at work in the films of Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin (Benjamin [1931] 1979, pp. 251–52). My point is that this origin story has yet to be written into photography’s history, despite, in fact, the many nods to Benjamin’s call for a “little history” of photography in the writing of photography’s history since the 1980s.32 Benjamin’s writing has been used to kill American modernism, not, as was the goal of the work of Rosler and her contemporaries, to “dismantle” it (Sekula [1978] 1984).33 This is the protest: work on history. Do not simply debunk it. A critical history of photography must acknowledge photography’s role in the writing of history, in the telling of stories of origins and accidents. Even Szarkowski understood that the story was everything.Photography was, the art world told us a lesser order, mired in temporality, as opposed to the transcendent world of painting. So you could deal with it as a practice less mediated, more immediate, than the one the art world has mulled over so intensively. It was accessible and vernacular, and it was low key…as far as I knew then, photography had no critical history.(Buchloh 1998, p. 24)

This is also the work of Ici et ailleurs, and like the flyers, the film is wholly didactic in its charge. It offers viewers a method. It suggests how to work “on the image” and how to collaborate. Take one of the most discussed segments of the film: the scene in which five of the film’s actors each hold up one still photograph documenting the Palestinian liberation struggle in front of a movie camera (Figure 11). Moved steadily before the lens (on the screen and as the screen) one after the other, as in a film, the still photographs are said to—are made to—represent the movement of the struggle through five predetermined stages: “The People’s Will,” “Armed Struggle,” “Political Work,” “The Prolonged War,” and “Until Victory.” As we hear Godard explain with reference to the film that he had hoped to make with Gorin, “The people’s will plus the armed struggle equals the people’s war. Plus, the political work equals the people’s education. Plus, the people’s logic equals the popular war extended. Extended until the victory of the Palestinian people.” “We,” he continues, “organized it that way. All the sounds, all the images in that order.” The still photographs pass before the movie camera in order to demonstrate how film is made as much as how film makes this order. The ordering of the still photographs in time, as time, is what film makes.34 “All and all, time,” Godard states at the close this scene, “has replaced space and speaks for it.”

Figure 11.

Still from Ici et ailleurs, dir. Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, 1976.

This lesson here, it should be clear, is not that the order is false. Ici et ailleurs is a film about the failure to make a film about a revolution taking place “elsewhere,” but it is not a condemnation of documentary. It does not announce or confirm the “unrepresentability” of the “Other.”35 This critique of representation is the liberal fallacy that the film condemns. Excavating the means by which representation takes place—on screen, through ordering—Godard and Miéville insist on the need to order images differently. This is the basis of solidarity. A film about how films are made, about how films make history, Ici et ailleurs orders already-familiar images—such as Eddie Adams’s Saigon Execution (1968) and by then iconic photographs of prisoners in Nazi concentration camps—into “new chains.” Or, to be more exact, the film demonstrates both or simultaneously how this is done and how to do this. This is the double work of montage and a critical history of photography. It undoes reference by redoubling the fact that it has already been undone in the media and through photography. As Godard reminds viewers in the final seconds of Ici et ailleurs, “the others are the elsewhere to our here.” Or, as stated in the opening sequence of his La Chinoise (1967), a film about a group of young (wannabe) Maoists in Paris learning how to be revolutionaries, “We are the words of others.” Montage does not collapse difference—undo the media’s work of making it seem that “we” are not one. Rather, like the televisual and print media through which and against which it writes and overwrites history, it allows difference to proliferate. It, too, that is, proliferates difference. History, Godard and Rosler insist, cannot operate any other way. Neither can photography. Understood critically, this is its work: to make and unmake history, to acknowledge that history is made. The seams must be out, and the words must already have been said. “I can’t say, I can only repeat” is Rosler’s protest chant, her mantra (Rosler [1981] 2006, p. 88).

4. Against Time

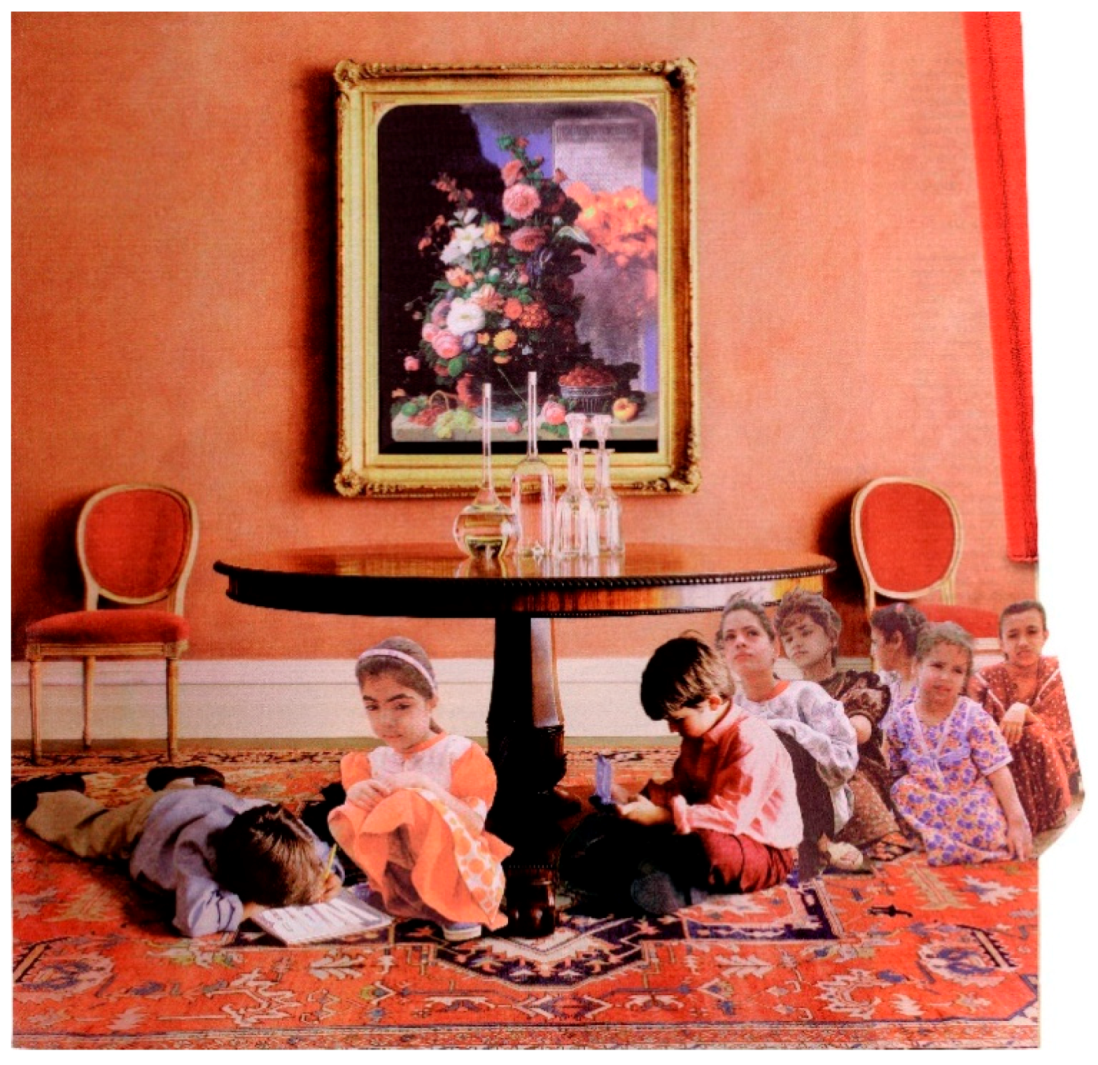

In 2004, in the wake of the US decision to go to war in Iraq, Rosler made a new series of photomontages. House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series, as Rosler titled this work, updates the “old.” Happy-go-lucky coeds cheer and chat for and through war’s newest technologies: cellular phones. Children sit or crouch under a table in a new vanitas (Figure 12). In this genre scene, small bodies, not bones, pile up, like paper doll cutouts, and exceed the frame. Technology and décor are updated, but the work of cutting and pasting the news remains the same.36 “Old” genres and forms are remade. Rosler has been repeatedly asked to address her decision to make a new series.37 Why repeat yourself? Why remake old work? The question is necessary and wholly misplaced. Repetition is the logic of Rosler’s protest. Since the 1960s, she has been protesting by repeating—by quoting a mode of address, by insisting that “we” are the words of others. She has been working through and on the telos of art and war, working through and on the way in which art and war are made to read as new and the news. And, like the war against which it protests, the new series is only nominally new. In fact, it is late. Rosler had already remade the photomontages in the early 1990s. She had already given them a new frame.

Figure 12.

Martha Rosler, Vanitas, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series, 2004. Photomontage. © Martha Rosler/Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

In 1991, Rosler exhibited the photomontages as color photographs at the Simon Watson Gallery in New York (Wallis 1992, p. 105). Her decision to remake the flyers as art, to frame them and hang them on the wall, had as much to do with the changes taking place in the art market in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when the administration under President Ronald Reagan stripped away the financial means by which artists could make art public, as it did with the next administration’s new wars (Rosler [1994] 2004, p. 356).38 The year 1991, after all, marked the so-called end of the First Gulf War. Or, to be more exact, it marked the “end” of “the war in Vietnam.” “The specter of Vietnam had been buried forever in the desert sands of the Arabian Peninsula” was how President George Bush put it in 1991 when he announced the swift conclusion to the new old war (Gardner and Young 2007, p. 1). In order to protest a “new” war in the Gulf, Rosler protested the “old” war that was still being fought at home. It had to be this way. It still is this way. Specters, as Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argue, will—are invented in order to—rise again and, again, be killed off (Marx and Engels 1848). They are invented by those in charge of writing history.39 Now, in turn, is not, can never be, the time of protest. This is simply the slogan making headlines in the news. Rosler’s protest takes place against this time. The photomontages both or simultaneously ape and mime it. They make history of the riots that will come.

Funding

This research received support from the Art Writers Grant Program, which is funded by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and administered by Creative Capital.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Simon Constantine and Larne Abse Gogarty for their feedback on this essay. I also want to thank the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful responses and helpful suggestions. Thanks as well to Alexandra Symons Sutcliff for her assistance in the Museum of Modern Art Archives. Finally, I owe much to my colleagues in the History of Art Department at UCL who organized the Teach-Out “Art Histories of Protest” during the March 2018 higher education strike for fair pensions, where an early version of this essay was first presented.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alberro, Alex. 1998. The Dialectics of Everyday Life: Martha Rosler and the Strategy of the Decoy. In Martha Rosler: Positions in the Life World. Edited by Catherine M. de Zegher. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 72–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bair, Nadya. 2016. The Decisive Network: Producing Henri Cartier-Bresson at Mid-Century. History of Photography 40: 146–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1979. A Small History of Photography. In One-Way Street and Other Writings. Translated by Edmund Jephcott, and Kingsley Shorter. London: Verso, pp. 240–57. First published in 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Bois, Yve-Alain. 1990. Painting as Model. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan-Wilson, Julia. 2009. Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam Era. Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Buchloh, Benjamin H. D. 1998. A Conversation with Martha Rosler. In Martha Rosler: Positions in the Life World. Edited by Catherine M. de Zegher. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 23–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bussard, Katherine. 2014. Unfamiliar Streets: The Photographs of Richard Avedon, Charles Moore, Martha Rosler, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cartier-Bresson, Henri. 1952. The Decisive Moment. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Chéroux, Clément. 2014a. A Bible for Photographers. In Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment. Göttingen: Steidl, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chéroux, Clément. 2014b. Henri Cartier-Bresson: Here and Now. Translated by David H. Wilson, and Ruth Sharman. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Catherine. 2015. A Decisive Moment, France, 1932. In Getting the Picture: The Visual Culture of the News. Edited by Jason E. Hill and Vanessa R. Schwartz. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Clover, Joshua. 2016. Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprising. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, Simon. 2019. From the Museum to the Street: Garry Winogrand’s Public Relations and the Actuality of Protest. Arts 8: 59. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/8/2/59/htm (accessed on 3 May 2019). [CrossRef]

- Cottingham, Laura. 1993. Crossing Borders: Martha Rosler. Frieze 13. Available online: https://frieze.com/article/crossing-borders/ (accessed on 13 February 2018).

- Davis, August. 2013. Star Wars: Return of the Sixties; Or, Martha Rosler versus Empire Strikes Back. Third Text 27: 565–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawsey, Jill. 2016. The Uses of Photography: An Introduction. In The Uses of Photography: Art, Politics, and the Reinvention of a Medium. Edited by Jill Dawsey. La Jolla: Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego, pp. 14–79. [Google Scholar]

- De Zegher, M. Catherine, ed. 2005. Persistent Vestiges: Drawing from the American-Vietnam War. New York: Drawing Center. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1997. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson, and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. First published in 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche, Rosalyn. 2018. Unrest. In Martha Rosler: Irrespective. New York: Yale University Press, pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Drabinski, John. 2008. Separation, Difference, and Time in Godard’s Ici et ailleurs. SubStance 37: 148–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Edwards, Steve. 2004. Vernacular Modernism. In Varieties of Modernism. Edited by Paul Wood. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 241–68. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Steve. 2012. Martha Rosler: The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems. London: Afterall. [Google Scholar]

- Emmelhainz, Irmgard. 2009. From Third Worldism to Empire: Jean-Luc Godard and the Palestinian Question. Third Text 23: 649–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franscina, Francis, ed. 1985. Pollock and After: The Critical Debate. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, Michael. 1998. Art and Objecthood. In Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 148–72. First published in 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Lloyd, and Marilyn Young, eds. 2007. Iraq and the Lessons of Vietnam, Or How Not to Learn from the Past. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Alan, ed. 2009. Martha Rosler: La Casa, La Calle, La Cocina/Martha Rosler: The House, the Street, the Kitchen. Ian MacCandless, and Juan Santana, trans. Granada: Centro José Guerrero. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1986. Towards a Newer Laocoon. In Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism: Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 1, pp. 23–38. First published in 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1995. Modernist Painting. In Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957–1969. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 4, pp. 85–94. First published in 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1995. Post Painterly Abstraction. In Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957–1969. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 4, pp. 192–97. First published in 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 1972. The Determination of News Photographs. Cultural Studies 3: 53–87. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Olivia. 2017. Consuming Palestine: Anticapitalism and Anticolonialism in Jean Luc-Godard’s Ici et ailleurs. Studies in French Cinema 18: 178–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, Rosalind. 1993. The Optical Unconscious. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kriebel, Sabine. 2014. Revolutionary Beauty: The Radical Photomontages of John Heartfield. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Pamela. 2004. Chronophobia: One Time in the Art of the 1960s. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. 1848. The Communist Manifesto. Available online: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Manifesto.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Moos, David, ed. 2005. The Shape of Colour: Excursions in Colour Field Art, 1950–2005. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- Museum of Modern Art. 1965. The Photo-Essay. Available online: https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_326378.pdf?_ga=2.203576088.983103398.1598342804-248679962.1567846310 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Museum of Modern Art. 1969. Atget. Available online: https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_326657.pdf?_ga=2.174936874.983103398.1598342804-248679962.1567846310 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Nesbit, Molly. 1994. Atget’s Seven Albums. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbit, Molly, and Hans Ulrich Obrist. 2005. Martha Rosler in Conversation with Molly Nesbit and Hans Ulrich Obrist. In Martha Rosler: Passionate Signals. Edited by Inka Schube. Ostfildren-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, pp. 6–63. [Google Scholar]

- Niessen, Niels. 2013. Access Denied: Godard Palestine Representation. Cinema Journal 52: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patenberg, Volker. 2015. Farocki/Godard: Film as Theory. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Christopher. 1982. The Judgment Seat of Photography. October 22: 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribalta, Jorge, ed. 2015. The San Diego Group: With Fred Lonidier and Martha Rosler. In Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, pp. 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2004. Lee Friedlander, An Exemplary Modern Photographer. In Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 113–31. First published in 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2006. 3 Works. Halifax: The Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, pp. 61–93. First published in 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2004. Theses on Defunding. In Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 321–34. First published in 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2004. The Suppression Agenda for Art. In Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 335–47. First published in 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2004. Place, Position, Power, Politics. In Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 349–78. First published in 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 1994. War in My Work. Camera Austria 47/48: 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2004. The Figure of the Artist, The Figure of the Woman. In Decoys and Disruptions: Selected Writings, 1975–2001. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler, Martha. 2019. Vietnam Story. In Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War. Edited by Melissa Ho. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, pp. 349–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Stephanie. 2020. Walker Evans: No Politics. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 1984. Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation). In Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works, 1973–1983. Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, pp. 53–75. First published in 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2017. Harry Callahan: Gender, Genre, and Street Photography. In Abigail Solomon-Godeau: Photography After Photography: Gender, Genre and History. Edited by Sarah Parsons. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 2002. On Photography. London: Penguin. First published in 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Sally. 1981. The Composite Photograph and the Composition of Consumer Ideology. Art Journal 41: 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stimson, Blake. 2008. A Photograph is Never Alone. In The Meaning of Photography. Edited by Robin Kelsey and Blake Stimson. New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 105–17. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 1966. The Photographer’s Eye. New York: Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 1971. Walker Evans. New York: Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 1973. From the Picture Press. New York: Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 2017. New Documents: Wall Label. In Arbus, Friedlander, Winogrand: New Documents. Edited by Sarah Hermanson Meister. New York: Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Keenanga-Yamahtta. 2016. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation. Chicago: Haymarket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tomba, Massimiliano. 2012. Marx’s Temporalities. Translated by Peter D. Thomas, and Sara Farris. Chicago: Haymarket. [Google Scholar]

- Varon, Jeremy. 2004. Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Volpato, Elena. 2019. As If. In Martha Rosler: Irrespective. New York: Yale University Press, pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, Brian. 1992. The Living Room War. Art in America 80: 104–7. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, Michael. 1999. On Gilles Deleuze on Jean-Luc Godard: An Interrogation of “la méthode du ENTRE”. Australian Journal of French Studies 36: 110–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In her writing and interviews, Rosler often makes note of the simplicity of her montage technique. In her words, “By using collage as simple as that taught in grade school, I wanted to suggest to the viewer that this was all well within their reach and that maybe they ought to make some work like this themselves” (Rosler 2019, p. 352). See as well Rosler’s discussion of this aspect of her work in (Buchloh 1998, p. 31, 54–55). See also (Volpato 2019). |

| 2 | In Rosler’s words, “At the time, in the 1960s, it seemed imperative not to show these works … in an art context. To show anti-war agitation in such a setting verged on obscene, for the site seemed properly the ‘street’ or the underground press, where such material could help marshal the troops, and that is where they appeared” (Rosler [1994] 2004, p. 355). For reproductions of the twenty photomontages making up the House Beautiful series, see (Gilbert 2009, pp. 49–72). |

| 3 | This is not to suggest that the circulation of the photomontages as flyers and in underground feminist journals such as Goodbye to All That! A Newspaper for Women has been ignored. See, for example, (de Zegher 2005, p. 71; Dawsey 2016, pp. 21–25). |

| 4 | This essay was completed in the summer of 2020, in the midst of the waves of protests that erupted in numerous cities across the US and around the world in response to the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25, 2020. |

| 5 | The phrase was coined by John Jacobs, a member of the Weatherman faction of Students for a Democratic Society. A pithy condensation of Lenin’s thesis on imperialism, it was eventually adopted as a protest chant or slogan in the late 1960s, during the “Days of Rage.” On the phrase and its history, see (Varon 2004). |

| 6 | Conversation with the author, December 17, 2019. See (Alberro 1998, p. 75) for a brief discussion of Rosler’s paintings. |

| 7 | For a study of American modernism shaped by and through critiques of formalism as well as the war in Vietnam, see (Bryan-Wilson 2009). See as well Rosler’s feminist critique of American formalism in (Rosler 2004). Though not the focus of the argument I am making here, the feminism of Rosler’s photomontage and her protest cannot be ignored. Importantly, it is evidenced not only by her attention to the media’s framing of domestic spaces as gendered but also by the heterodoxy of the work. There is, as she puts it, little sense of “mastery” in the “simple” act of montage. Rosler discusses her feminism along these lines in (Buchloh 1998, pp. 51–54). For a feminist reading of the photomontages, see (Deutsche 2018). |

| 8 | On the retrospective invention of Post Painterly Abstraction to describe as much as institutionalize the work of Morris Louis and Jules Olitski as well as Jack Bush and Helen Frankenthaler, see (Moos 2005). See also (Greenberg [1964] 1995). |

| 9 | The literature on Fried’s thesis is vast. It builds in conjunction with studies of the rise (and fall) of American formalism and the late writings of Clement Greenberg, including, most notably, his 1960 essay “Modernist Painting.” See (Greenberg [1960] 1995) and the studies of those writing histories of American modernism through and against Greenberg’s formalism, including (Franscina 1985; Bois 1990; Krauss 1993). See also Pamela Lee’s study of American formalism as a problem of time in (Lee 2004). |

| 10 | As is noted in several of the contributions to this special issue, Rosler’s critique of Szarkowski’s modernism also persisted. It frames much of her writing about photography in the 1980s and 1990s, including her seminal critique of the ways in which documentary had been poorly historicized since the 1960s: “In, around and afterthoughts (on documentary photography).” See (Rosler [1981] 2006, pp. 61–93). On Rosler’s critique of Szarkowski and street photography, in particular, see (Bussard 2014, pp. 99–137). |

| 11 | Rosler’s contemporaries include Allan Sekula, Fred Lonidier, and Phel Steinmetz. On this history, see (Dawsey 2016). See also Sekula’s response to the New Documents exhibition in (Sekula [1978] 1984, pp. 53–75). |

| 12 | On Szarkowski’s attention to the terms of Greenberg’s modernism, see (Phillips 1982, pp. 53–56; Edwards 2004, pp. 252–53). |

| 13 | For a historical account of The Decisive Moment and Cartier-Bresson’s work as reportage, see (Chéroux 2014b; Clark 2015; Bair 2016). |

| 14 | For Greenberg’s contribution to the story modernism’s need to shed narrative or the “dominance of literarature,” see (Greenberg [1940] 1986, p. 28). |

| 15 | Images à la sauvette and The Decisive Moment were published simultaneously in 1952. On the publication history, see (Chéroux 2014a). |

| 16 | For a reading of “the decisive moment” in these terms and in the context of the shoring up of modernism in the 1950s, see (Stimson 2008). |

| 17 | The dialogue with Friedlander is apparent. He, too, as Rosler notes in the above-quoted essay, shot his photographs through a car window. However, according to Rosler, for Friedlander, the window served as a means to track or record himself, to confirm his presence, albeit as a shadow or a reflection, not as a further means of mediation. |

| 18 | For this history, see (Schwartz 2020). |

| 19 | See the Press Release for Atget (Museum of Modern Art 1969, p. 2). Szarkowski is quoted for hailing Atgets’s work as a record of his “interior life.” |

| 20 | See “Checklist,” Protest Photographs [MoMA Exh. #929, May 23–June 2, 1970], Department of Photography Records, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Eighteen of the fifty-seven photographs included in the exhibition were by Winogrand, and the majority were by photographers working for Magnum, including Burk Uzzle and Charles Harbutt. Notably, Filo’s photograph was privileged. It was displayed alone, separated from the other double rows of photographs lining the gallery walls and as the culmination of the exhibition. The exhibition—and protest—crescendoed in death and outrage repackaged as a singular, iconic shot. |

| 21 | As part of the strike, several museums closed for the day; others offered free entry. On the Art Strike and related protests, see (Bryan-Wilson 2009, pp. 112–21). |

| 22 | This was also the curatorial conceit of Szarkowski’s 1973 exhibition From the Picture Press. Produced with the assistance of Diane Arbus and Carole Kismaric, the photo editor of Time-Life Books, as well as editors of the New York Daily News, this exhibition pulled photographs from their pages, stripped them of editorial and historical context, and presented them as representative of “enduring human issues.” All of the photographs were exhibited without captions. See (Szarkowski 1973). See as well the curatorial statement for an earlier exhibition of news photographs, The Photo Essay (1965). Though in this exhibition, Szarkowski kept the pages intact, displaying the photographs as they had appeared on the page, albeit on a much larger scale, the exhibition was designed with the following statement in mind: “Today … some essay photographers are questioning the premise of the picture story and suggesting that perhaps the picture should be judged for its intrinsic meaning and not just as one element in a unified statement” (Museum of Modern Art 1965, p. 2). |

| 23 | The literature on photomontage is extensive. Much of it attends to claims for the truth or fallacy of photography and the news. For an overview of these debates, see (Kriebel 2014). My concerns are otherwise. I am interested in the making of the news as well as in Rosler’s engagement with how the news is made. For one seminal account of the American formation of photomontage and its attention to codes of mediation, see (Stein 1981). |

| 24 | Conversation with the author, December 18, 2019. |

| 25 | See, for example, Joshua Clover’s consideration of the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 as part of a long history of the riot as a social form in (Clover 2016). See as well (Taylor 2016) on the difference between accounting for Black Lives Matter as a moment and a movement. |

| 26 | As Rosler notes with regard to First Lady (Pat Nixon), “Most viewers see this [the photograph] as a Vietnamese woman, but it is the actress Faye Dunaway in Arthur Penn’s fad movie of the era Bonnie and Clyde” (Rosler 1994, p. 69). |

| 27 | See, for example, Susan Sontag’s reading of the film in the opening pages of On Photography (Sontag [1971] 2002, p. 3). |

| 28 | In his account of Godard’s war films, Niels Niessen insists that the exclusion of images from the war in Vietnam makes Les Carabiniers “all the more a film about Vietnam” (Niessen 2013, p. 16). |

| 29 | Rosler’s discussion of the seams or joins is worth quoting in full. She writes, “I wanted tableaux more than action shots. Some aren’t all that rational as space, while other have no military subjects. But still, they stitch together those figures and grounds into one visual field, although the joins are often visible—not to mention the lettering peeking through from the backs of the magazine pages. I aimed to undercut any suggestion that the scenes were meant to seem ‘real,’ to show clearly that no high-handed moves were going on here” (Rosler 2019, p. 352). |

| 30 | On the making of Ici et ailleurs, see (Emmelhainz 2009; Harrison 2017). |

| 31 | Laura Cottingham makes note of the similarity in her important essay on Rosler’s photomontages and their attention to the spatial codes of mediation. See (Cottingham 1993, n.p.). |

| 32 | In the 1980s, Benjamin’s writing on photography helped to establish the framework for postmodernism’s critique of modernism: of its claims for originality, authenticity, and mastery. See (Phillips 1982). In this context, photography, I am suggesting, found its history through and against a modernist theory of art, not Benjamin’s historical materialism. |

| 33 | Though Sekula authored this essay, it was a collaborative work. Speaking of her time in San Diego, working with Sekula, Lonidier, and Steinmetz as well as David and Eleanor Antin, Rosler notes, “‘Dismantling Modernism’ was one of our oft-stated intentions. I even went so far as to assign my students short questionnaires on what modernism was and on their relationship to it” (Ribalta 2015, p. 80). |

| 34 | In addition to Deleuze’s extended study of the time of Godard’s montage, see (Witt 1999; Drabinski 2008). |

| 35 | This is assumed in much of the writing on Ici et ailleurs. See (Emmelhainz 2009; Niessen 2013, p. 2; Harrison 2017, p. 2). |

| 36 | This includes the technologies of capture and making. Though made by hand, by cutting and pasting the print news, the photomontages making up the New Series were printed digitally. In 2008, as Rosler continued to work on the series, she began using Photoshop to “cut” and “paste.” “I went,” she explains, “for a somewhat slicker image, to fit better with improved magazine and newspaper printing techniques, as well as the glossier people and their props” (Gilbert 2009, p. 200). |

| 37 | See, in particular, (Gilbert 2009, pp. 197–200; Davis 2013). |

| 38 | Though not discussed explicitly with regard to her decision to exhibit the photomontages, Rosler is alluding to the Reagan administration’s attack on the National Endowment for the Arts and the “culture wars” that followed. Rosler writes about these wars extensively in two essays: “Theses on Defunding” and “The Suppression Agenda for Art.” See (Rosler [1982] 2004; Rosler [1990] 2004), respectively. |

| 39 | On this corrective to the canonical reading of the first line of The Communist Manifesto, see (Tomba 2012, pp. 35–59). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).