“Cemetery=Civilization”: Circus Wols, World War II, and the Collapse of Humanism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

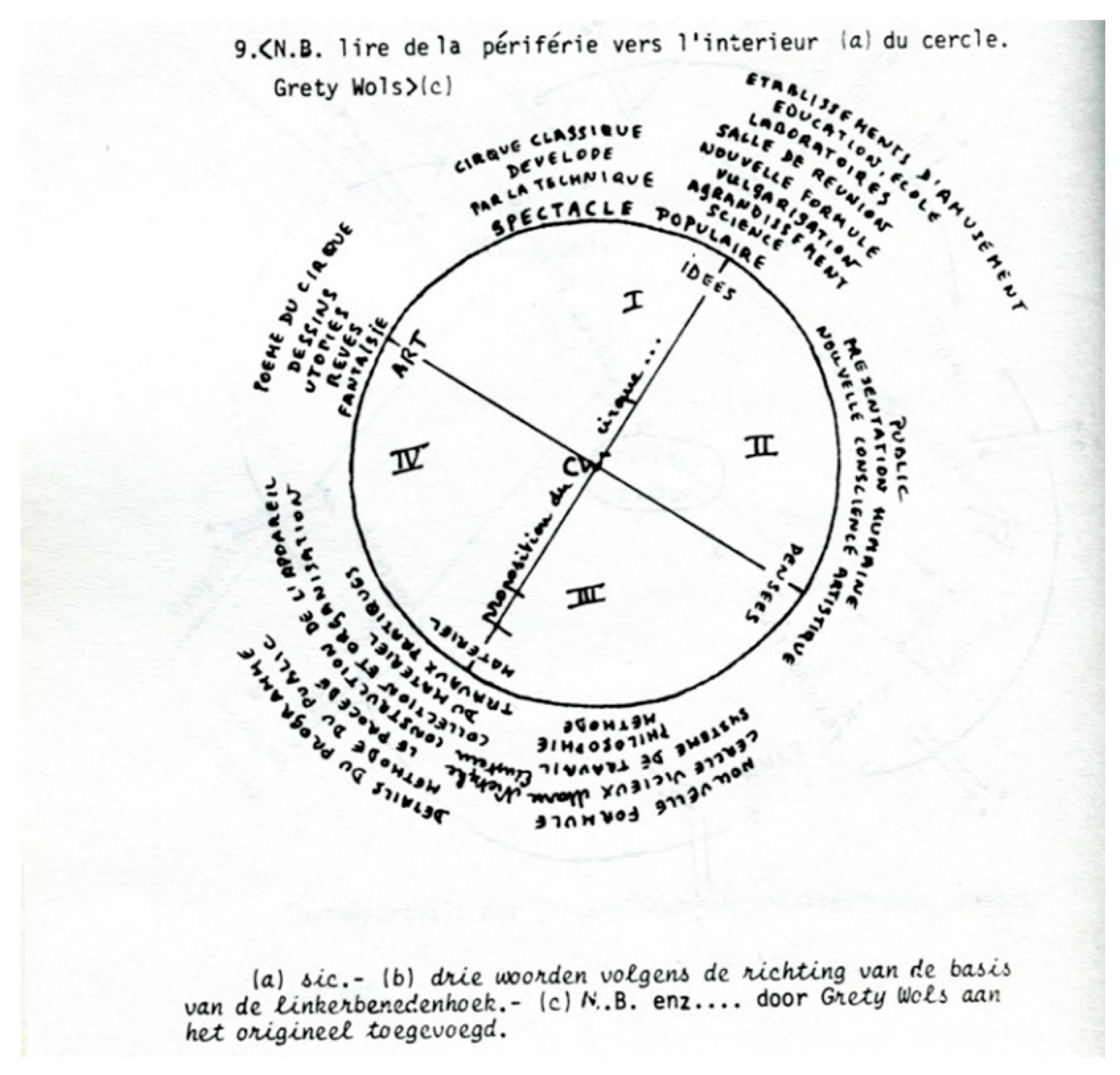

2. The Circus Wols Project

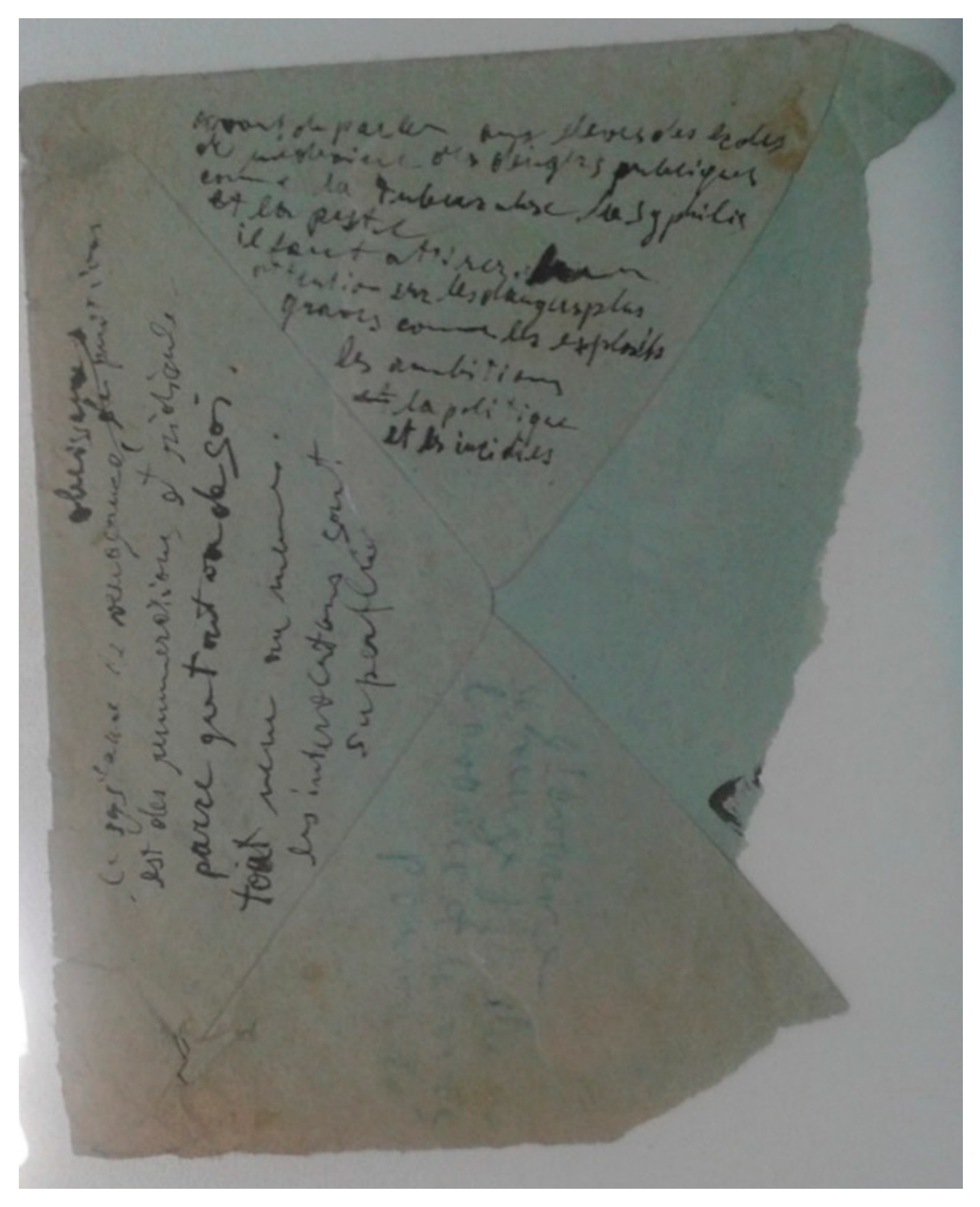

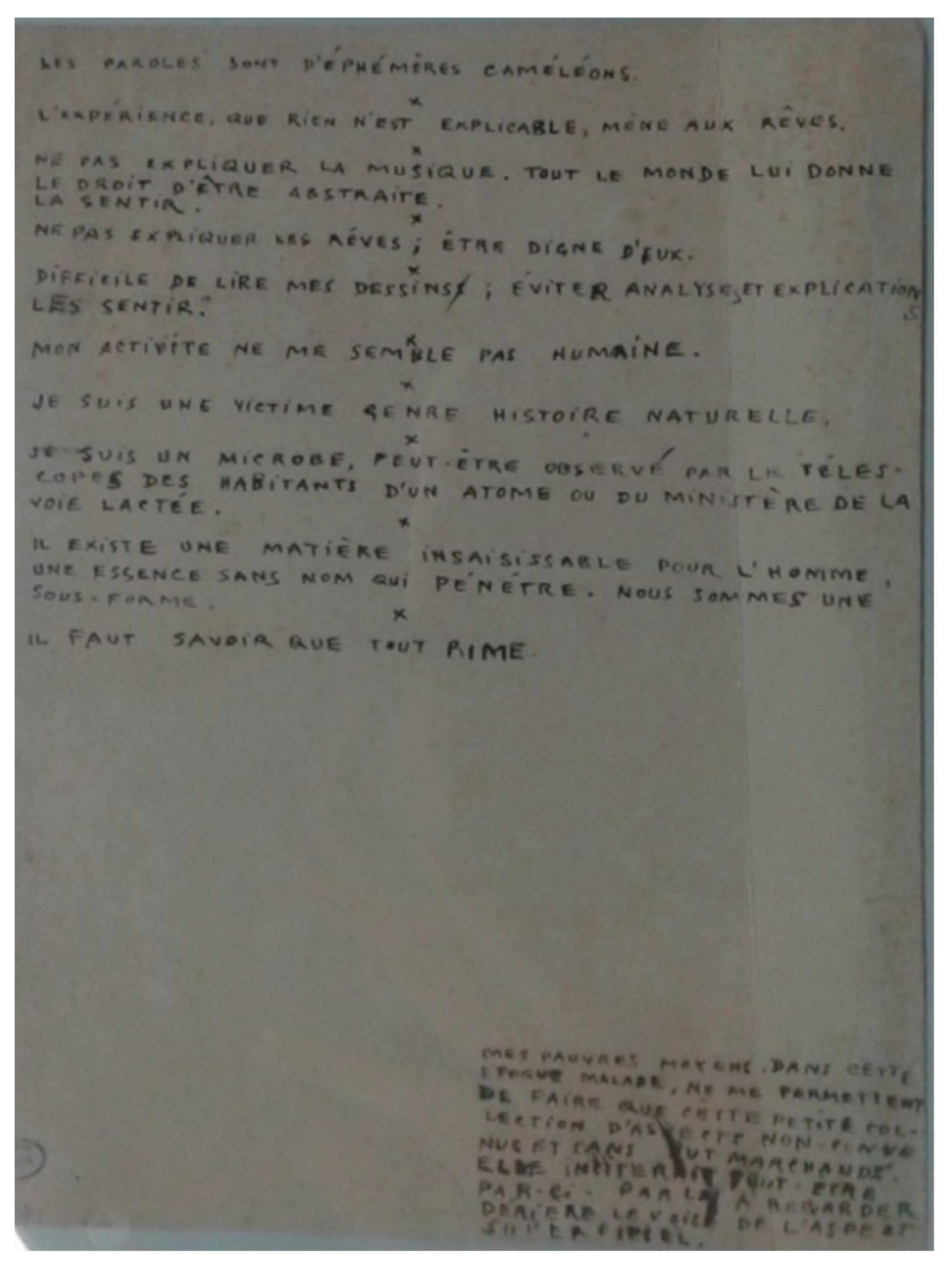

2.1. Written Sources

[…] My chief manuscript on which I worked since (sic) two years is intitled (sic): “Circus Wols” [.] This work is a manuel (sic) not only conceiving a new kind of employing technic (sic) but also meaning to establish a relationship of art in general, science, philosophy and human life. This “Circus Wols” is a suggestion to create in a democratic manner the education of taste and public opinion, popularising spheres that up to now were reserved to certain classes only.Here I miss the possibility of collaboration and research as well as the moral and artistic spons[ors]hip (sic). I hope to interest rapidly minds and institutions in U.S.A (sic) for my work or part of my work […]There would be possibility for “Circus Wols” by the relations of Dr. Wilezinsky to Mr W. Zilzer 8301 Kirkwood Drew Hollywood. Cal. and to Dr. Paul Wohl 547 5th av. N. Y […].”

Wols calls Circus Wols a “hypothesis” contradicting his own definition that it is the solution to his problems. Again, the ambition to encompass all possibilities is thwarted by the doubt that such a project could ever be realized.[…] During one year of concentration [or in concentration camps?5] the necessity dawned on me to generalize all my problems towards the unknown goal of my life; I therefore created a hypothesis I call “Circus Wols”. I believe this name is logical because the circus contains all the possibilities, be a central of all my occupations (sic), even if it will never be realized […].6

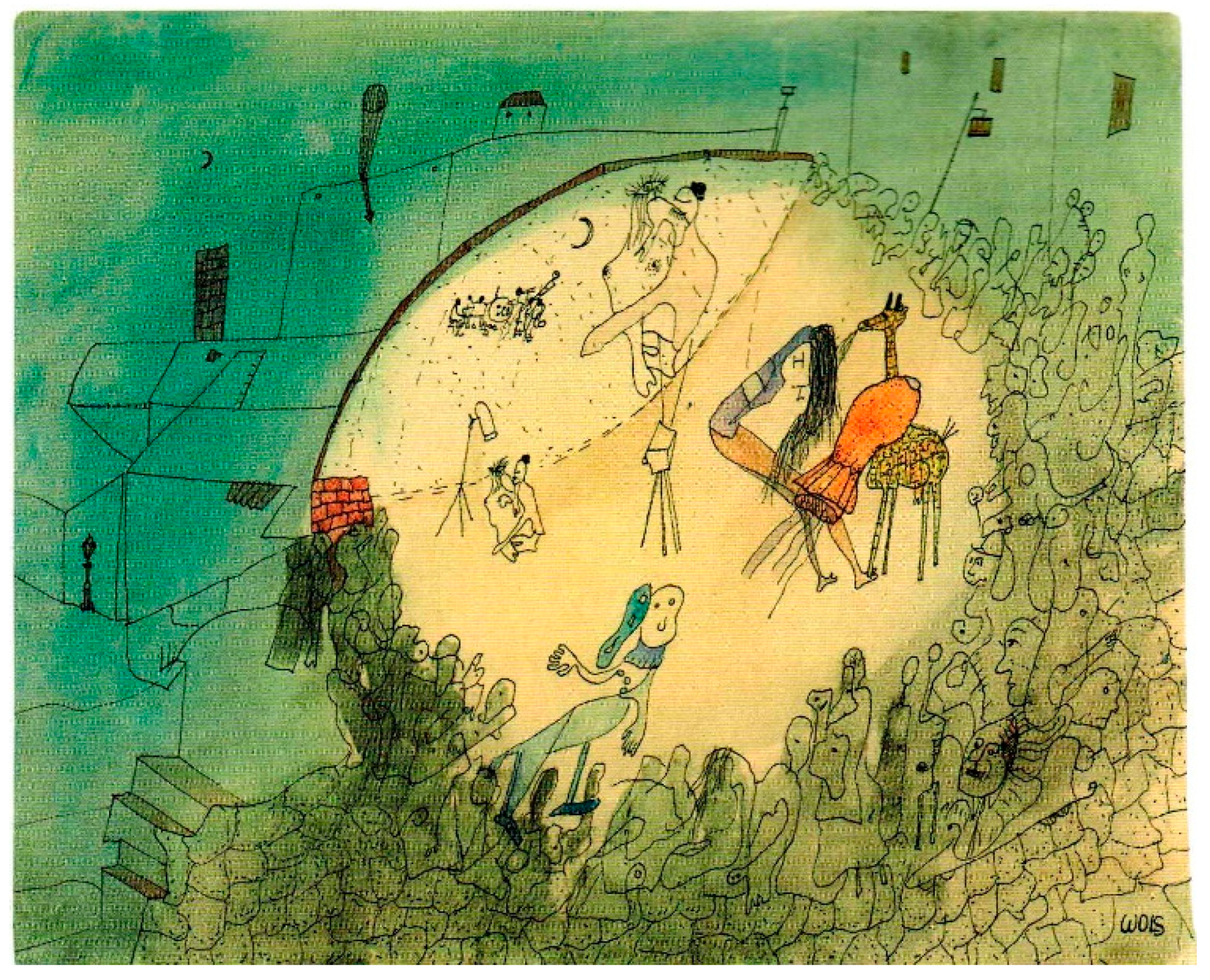

2.2. Drawings

3. Circus Wols: A Slippery Fairyland for the Humanist Utopia

3.1. Gruesome/Delightful Entertainment

- it is possible that god prefers flies

- to humans

- the anthropods are technically superior

- than humans

- the day when a butterfly became beautiful

- it fulfilled its task

- it is dubious that one day humans

- will reach the level of wasps.9

3.2. Between Humanist Utopia and Rejection of Humanism

- Man thinks only for and by himself,

- creating his own God

- loving, hating himself,

- unable to take the universe

- but always pretending

- by all ways of knowledge

- that he and sea souls are old friends.

- Beethoven didn’t understand the rites

- and the drums of Zulus

- We barely heard the birds,

- and vice-versa.

- So man will never learn to fly like birds,

- swim like fish,

- except in intimate reality.

- he cannot understand the absolute though he

- must

- love what has captured him beforehand.

- (theris (sic) no need to act, only to [think] believe.

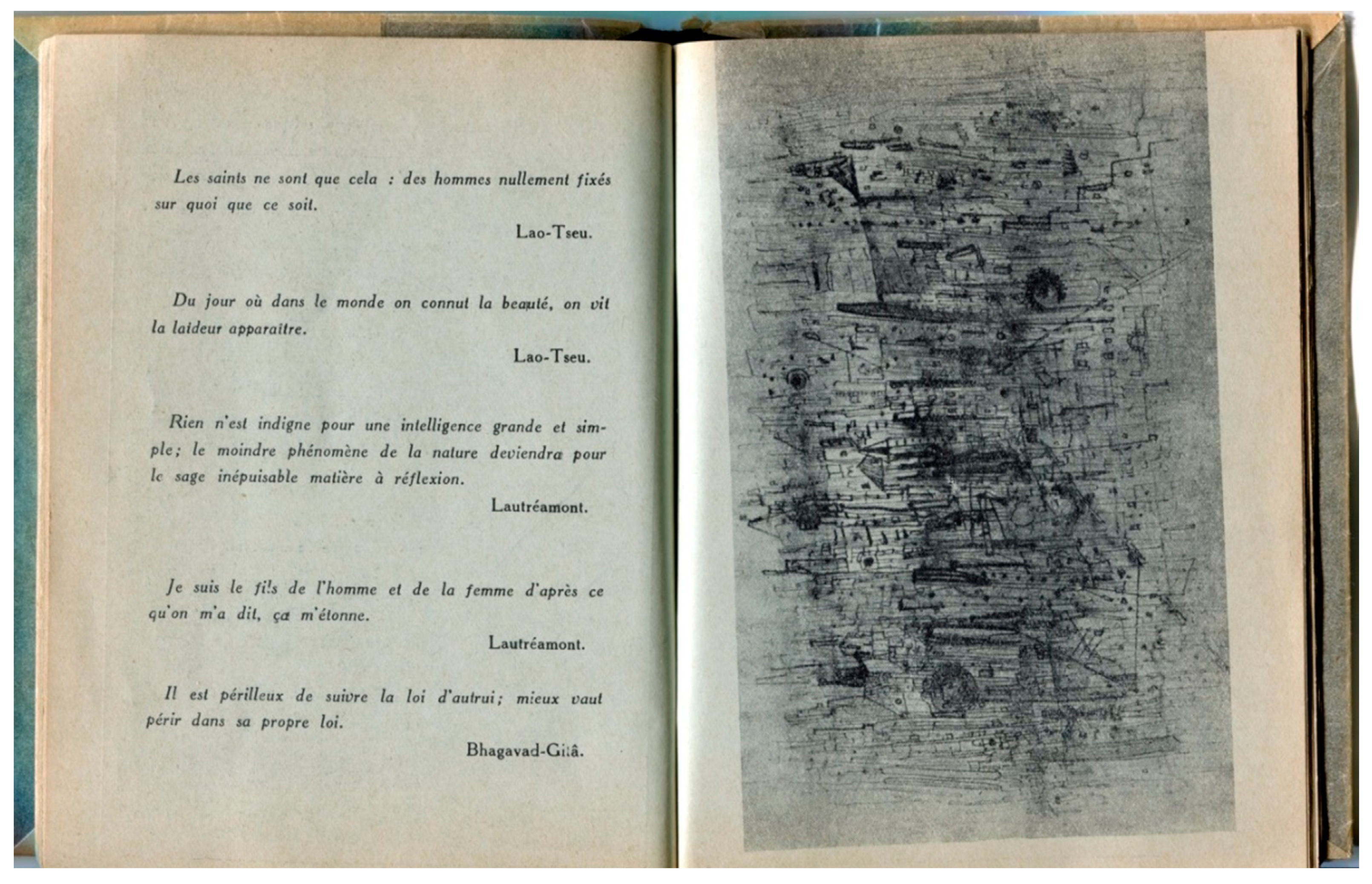

4. Wols and (Art) History: The Abhumanist Thesis

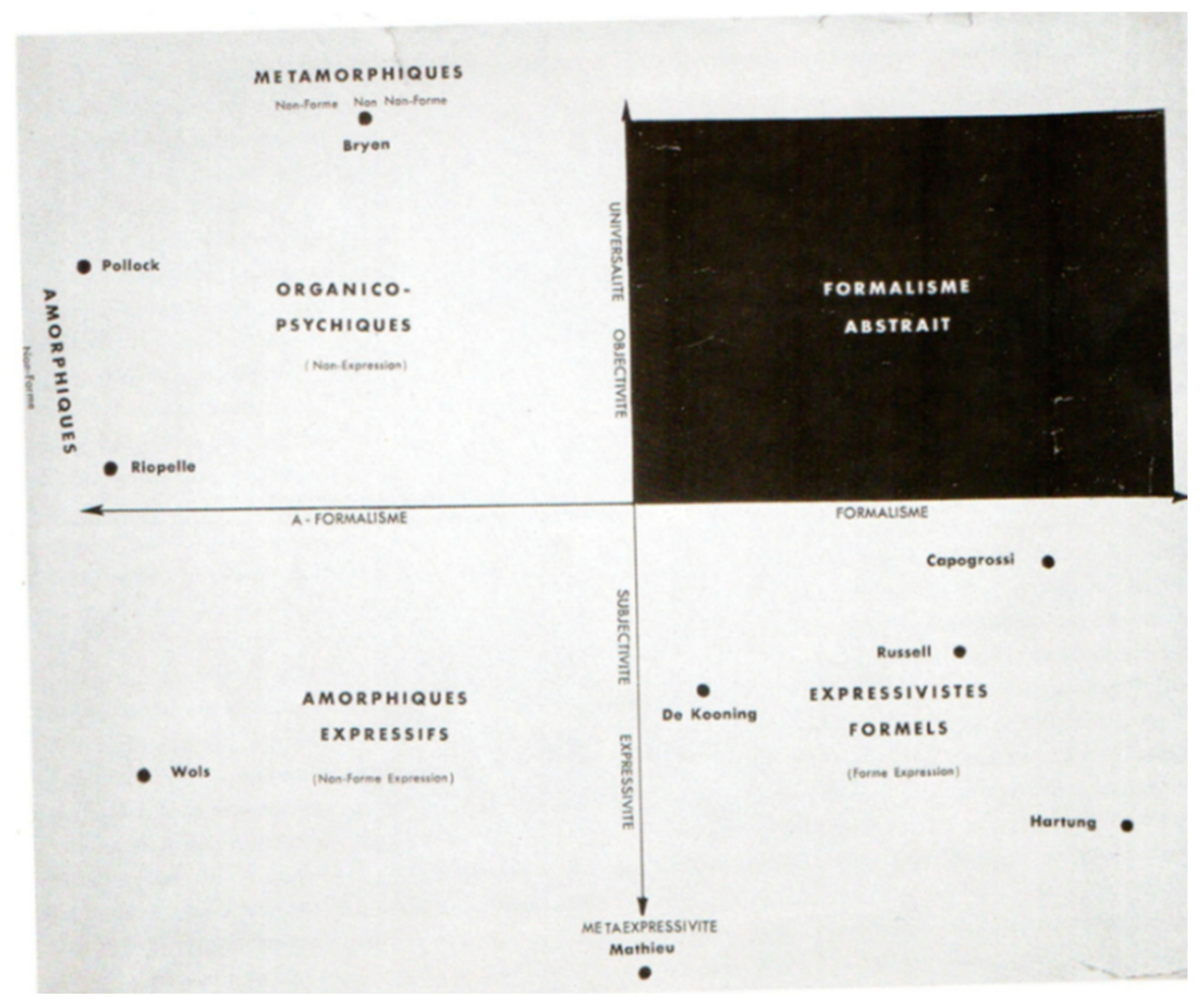

4.1. Difficulty to Categorize Wols in the Post-World War II Parisian Art World

4.2. Wols and Abhumanism

I had an old friend. I knew the schemes and rites by which he conjured his human status. He was, among the human beings I have known, the least mired in the species. He possessed a lucidity which made him discover complex techniques destined to improve the rhythm of his life, and superstitions which enabled him to function more as a vegetal machine than a citizen. He was in the whirlwind, humanity bored him.24

Schoolchildren knew by heart the names of the forty members of the academy, just like the names of the ministers of successive cabinets. Kipling, d’Annunzio, Tolstoy structured our international literary universe. There was a sort of coziness and security in the knowledge that a little schoolchild might acquire of the Grand Siècle, the Middle Ages, Antiquity; and all due to an organization of the universe that was the culmination of the preparatory stages of humanity. That sensation of the absolute modern world is extremely threatened today. I would even say that it no longer exists.26

What is abhumanism?It is man finally letting go of the idea that he is the center of the universe.What is the purpose of abhumanism?To diminish the sense of our eminence, of our dominion and excellence in order to restrain in the same time the sacrilegious gravity and the poisonous stinging of the insults and pains we are suffering.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allain, Patrice. 2009. Jacques Baron. L’enfant perdu du Surréalisme. La Nouvelle revue Nantaise: 5. Nantes and Paris: Les Amis de la Bibliothèque Municipale de Nantes/Éditons Dilecta. [Google Scholar]

- Audiberti, Jacques. 1946. Guéridons abhumains. L’âge D’or 3: 22–34. [Google Scholar]

- Audiberti, Jacques. 1952. Marie Dubois. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Audiberti, Jacques. 1955. L’Abhumanisme. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Audiberti, Jacques, and Camille Bryen. 1952. L’Ouvre-Boîte. Colloque Abhumaniste. Paris: Callimard. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, George Howard. 1969. Sartre and the Artist. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand-Dorléac, Laurence. 1997. L’Œuvre au camp. In Les Peintres au camp des Milles. Septembre 1939-été 1941. Edited by Michel Bépoix. Aix-en-Provence: Actes Sud, pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bois, Yve-Alain, and Rosalind Krauss. 1996. L’Informe. Mode D’emploi. Paris: Editions du Centre Pompidou. [Google Scholar]

- Caille, Béatrice, and Juliette Laffon. 2013. Bellmer, Ernst, Springer, Wols au Camp des Milles. Aix-en-Provence: Fondation du Camp des Milles, Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- De Bieberstein Ilgner, Patrycja. 2013. Wols. Retrospective. Edited by Toby Kamps. Houston: The Menil Collection, Munich: Hirmer, Bremen: Kunsthalle Bremen, pp. 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- De Solier, René. 1951–1952. Wols. Cahiers de la Pleiade 13 (Autumn–Spring): 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Delandes, André. 1964. Audiberti. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, Carl. 1930. À propos d’une exposition à la galerie Pigalle. Documents 2: 104–11. [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Matalon, Emmanuelle. 1991. Les Artistes-peintres allemands en exil à Paris 1933–1939. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris, France. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, Bernard. 2020. Métamorphoses d’Audiberti. Une Biographie 1899–1965. Saint-Jean des Mauvrets: Editions du Petit Pavé. [Google Scholar]

- Frobenius, Leo. 1930. Dessins rupestres du Sud de la Rhodésie. Documents 4: 185–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, Varian. 1945. Surrender on Demand. New York: Randon House. [Google Scholar]

- Gausmann, Angelika. 2013. Trop beau pour rester dans l’oubli. In Mémoire du camp des Milles 1939–1942. Marseilles: Métamorphoses/Le Bec en L’air. [Google Scholar]

- Glozer, Laszlo. 1980. Wols Photographe. Paris: Editions du centre Pompidou. [Google Scholar]

- Grandjonc, Jacques. 1999. Europe-Amérique. D’un exil à l’autre. In Varian Fry. Mission Américaine de Sauvetage des Intellectuels Antinazis. Aix-en Provence: Actes Sud, pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Griaule, Marcel. 1930. Un coup de fusil. Documents 1: 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Guérin, Jeanyves. 1999. Audiberti: Cent ans de Solitude. Paris: Honoré Champion. [Google Scholar]

- Guilbaut, Serge. 2008. Postwar. On an Exposition: Tempestuous Transtlantic Culture, 1946–1956. Edited by Laurence Bertrand-Dorléac. Seminar Arts & Société #22. Paris: Fondation nationale des Sciences Politique, Available online: http://www.sciencespo.fr/artsetsocietes/en/archives/2206 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Haftmann Werner. 1964. Malerei im 20. Jahrhundert. Munich: Prestel. First published 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Haftmann, Werner, Jean Leymarie, and Michel Ragon. 1971. Abstract Art Since 1945. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Inch, Peter. 1978. Circus Wols. The Life and Work of Wolfgang Schulze. Todmorden: Arc Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kafka, Franz. 2009. The Metamorphosis. Translated by Ian Johnston. Auckland: The Floating Press. First published in German 1915. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/metamorphosis/oclc/605918681 (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Kessin Birman, Elizabeth. 1997. Moral Triage or Cultural Salvage? The Agenda of Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Committee. In Exiles+Emigres. The Flight of European Artist from Hitler. Edited by Stephanie Barron. Los Angeles: LA County Museum of Art, pp. 100–9. [Google Scholar]

- Koldehoff, Stefan. 2011. Plötzlich dieser Überschuss. Die Welt. June 6. Available online: https://www.welt.de/print/wams/kultur/article13425973/Ploetzlich-dieser-Ueberschuss.html (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Kuon, Peter. 2008. Les Images d’ailleurs dans les récits de déportation. In Exils, Migrations, Création. Exil Anti-Nazi, Témoignages Concentrationnaires. Edited by Jürgen Doll. Toronto: Indigo, Marne-la-Vallée: Université Marne-la-Vallée, pp. 171–79. [Google Scholar]

- Leiris, Michel. 1929. Dictionnaire critique: Civilisation. Documents 4: 221–22. [Google Scholar]

- Leiris, Michel. 1930. L’Œil de l’ethnographe (À propos de la Mission Dakar-Djibouti). Documents 7: 404–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, Peter. 2017. Posthumanism. A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, Georges. 1963. Au-delà du Tachisme. Paris: René Julliard. [Google Scholar]

- Mehring, Christine. 1999. Wols Photographs. Cambridge: Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University Art Museums. [Google Scholar]

- Mémoire du camp des Milles. 2013. Mémoire du camp des Milles 1939–1942. Marseilles: Métamorphoses/Le Bec en L’air. [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, Éric. 1997. Fabriques de L’homme Nouveau: De Léger à Mondrian. Paris: Éditions Carré. [Google Scholar]

- Paire, Alain. 2013. Hommes de brique. In Ernst, Springer, Wols au Camp des Milles. Edited by Béatrice Caille and Juliette Laffon. Aix-en-Provence: Fondation du Camp des Milles, Paris: Flammarion, pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, Hans-Joachim. 2010. Wols. Les Aphorismes. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Rathke, Ewald. 2013. On the Biography of the Art of Wols. In Wols. Retrospective. Edited by Toby Kamps. Houston: The Menil Collection, Munich: Hirmer, Bremen: Kunsthalle Bremen, pp. 34–54. [Google Scholar]

- Restany, Pierre. 1962. Une peinture existentielle: Wols. xxe Siècle 24: 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1948a. Visages. Paris: Seghers. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1948b. Nourritures. Paris: Jean Damase. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1964. Doigts et non-doigts. Situations IV: 408–34. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Katy. 2011. Since ’45. America and the Making of Contemporary Art. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, Katy. 2013. Undoing Wols. In Wols. Retrospective. Edited by Toby Kamps. Houston: The Menil Collection, Munich: Hirmer, Bremen: Kunsthalle Bremen, pp. 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Slavkova, Iveta. 2004. Circus Wols: Le testament de Wols au camp des Milles. In Les Écrits D’artistes Depuis 1940. Edited by Françoise Levaillant. Caen: IMEC, pp. 145–57. [Google Scholar]

- Slavkova, Iveta. 2011. La bouteille de Wols, la plume de Sartre et une histoire à réécrire. Food and History 9: 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavkova, Iveta. 2018. Entre charme et effroi. Circus Wols, le récit de Wols des années terribles. In La France en guerre. Cinq «Années Terribles». Edited by Jean-Claude Caron and Nathalie Ponsard. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, pp. 327–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tapié, Michel. 1951. Véhémences Confrontées: Bryen, Capogrossi, De Kooning, Hartung, Mathieu, Pollock, Riopelle, Russell, Wols (March 8–31). Paris: Galerie Nina Dausset. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Sue. 2000. Hans Bellmer: The Anatomy of Anxiety. Cambridge and London: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toloudis, Constantin. 1980. Jacques Audiberti. Boston: Twayne Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Vallier, Dora. 1998. L’Art abstrait. Paris: Hachette. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, Claire. 1985a. Wols. Aforismen en Kanttekenningen. Ghent: Drukkerij Goff. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, Claire. 1985b. Wols. Biografische Documenten. Ghent: Drukkerij Goff. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, Claire. 1985c. Wols. Brieven van e aan Wols. Ghent: Drukkerij Goff. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme, Claire. 1986. Le bateau ivre. Biographie critique et documentée de l’artiste. Wols (1913–1951). In Wols sa vie…. Edited by Gerhard Götze. Paris: Goethe Institute, n.p. [Google Scholar]

- Verspohl, Franz-Joachim. 1991. Post-war Debates: Wols and the German reception of Sartre. In The Divided Heritage. Themes and Problems in German Modernism. Edited by Irit Rogoff. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 50–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wols. 1945. Wols. Paris: Jean Belmont/Galerie Drouin. [Google Scholar]

- Wols. 1989. Wols. Bilder, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen, Photographien, Druckgraphic. Zürich: Kunsthaus. [Google Scholar]

- Wols. 2013. Wols Retrospective. Edited by Toby Kamps. Houston: The Menil Collection, Munich: Hirmer, Bremen: Kunsthalle Bremen. [Google Scholar]

- Wols, fund Iliazd. 1940–1944. Archives, Dieulefit, Fund Iliazd (Ili 37–39). Paris: Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | “Moi je rêve de réaliser un livre et de ne pas disperser avant les documents”. The original French texts will be systematically given in footnotes. Unless otherwise stated, all translations of Wols, Audiberti and Bryen are mine. Some of Wols’s aphorisms can be found in English in scattered publications but there is no reference edition. |

| 2 | “l’être le moins enfoncé dans l’espèce”. |

| 3 | “Une population syphilitique est plus propre qu’une population gestapolisée”. |

| 4 | “avec les flèches je veux montrer que je laisse les dossiers tous les phénomènes sujets etc. continuellement en relations (sic) entre eux dans toutes les directions. Quand j’aperçois un problème un sujet etc… je vais le mener par tous les dossiers pour obtenir un resultat (sic) soit pour l’ensemble soit comme détail, soit pratique soit [unreadable]”. |

| 5 | I have translated the document and have not used the English version proposed by Peter Inch in 1978 (Inch 1978, n.p.). Too fluent, the latter overlooks the ambiguities and awkwardness of Wols’s original text. For instance, “Pendant un an de concentration” is unambiguously translated into “I have been interned for a year now”. The document does not mention any concrete events and insists rather on the intellectual genesis of Circus Wols, so “concentration” might just refer to a period of intense intellectual work. Wols often makes puns in French so the ambiguity might have been intentional. |

| 6 | “Pendant un an de concentration la nécessité m’est advenue de généraliser tous mes problèmes pour le but inconnu de ma vie; j’ai donc créé une hypothèse que j’appelle: Circus Wols. Je crois ce nom logique parce que le cirque contient toutes les possibilités, d’être une centrale de mes occupations (sic), même s’il en sera jamais réalisé”. |

| 7 | “Non, ce n’est pas chez moi que vous avez oublié ‘Kafka’. Je m’en serais aperçu après votre départ et vous l’aurez (sic) renvoyé”. |

| 8 | “Circus Wols peut être p. Exemple: […] ZOO (entre autres ZOO d’insectes, d’anthropodes”. |

| 9 | “il est possible que dieu prefere [sic] les mouches/aux hommes/les anthropodes sont techniquement superieur [sic]/a [sic] l’homme/le jour [lorsque] un papillon a été beau/il a accompli sa tache/il est douteux que l’homme arrivorat [sic]/au niveaux [sic] des gueppes [sic]”. Claire Van Damme’s transcription systematically designates anthropode as a mistake but as explained above, I have not followed her in this choice. |

| 10 | There are numerous publications on the treating of that subject. Eric Michaud offers an insightful reflection on the artists as the New Man in his collection of essays Fabriques de l’homme nouveau (Michaud 1997). |

| 11 | “Pour le reste vous savez aussi bien que moi qu’on vit dans une époque magnifique mais drôle et je pense que le changement est proche”. |

| 12 | “Sauf Bach la race blanche n’a pas encore produit grand chose”. |

| 13 | “Le control (sic)/analyse/synthèse de moi-même du travail, matériel/milieu/réalisation/succès/dessins/…” |

| 14 | “Je suis complètement d’accord sur la piètre valeur de notre époque–pourtant nous sommes ‘dedans’ et nous dépendons de la loi de ‘l’offre et de la demande’”. |

| 15 | “Avant de parler aux élèves des écoles [….] aux danger publiques comme la tuberculose, la syphilis et la peste, il faut attirer leur attention sur les dangers les plus grands comme les exploits, les ambitions et la politique et les […].” |

| 16 | “On raconte ses petits contes/terrestres/à travers de petits bouts de papiers (sic)”. Claire Van Damme mentions the multiple citations of this aphorism. |

| 17 | “Homme, as-tu déjà vu le zébra (sic) faire l’amour? Ça change les draps. L’art et la littérature gaffent. Le meilleur on tue.” |

| 18 | “Mon activité ne me semble pas humaine”. |

| 19 | “[…] ayons un peu d’estime pour René Drouin pour s’avoir moquer (sic)/avec ces aquarelles presentés (sic) dans des aquariums exagérés/de sa client elle (sic) des snobs et de mioppes (sic)”. The works were presented in illuminated vitrines which Wols compares to aquariums. |

| 20 | “en effet ces derniers mois on a vu 2 ou 3 fois passer dans cette impeccable architecture l’ombre d’un petit homme presque invisible et quasi chauf (sic). Mais toujours il s’enfuit tout de suite pour rejoindre les quartiers des bistrots”. |

| 21 | My conversations with gallerist Christoph Pudelko (1998–1999) and scholar Claire Van Damme (2011) confirmed the litigations, although their points of view were different. A few letters at the Documentation of the Musée national d’Art moderne (Centre Pompidou) also discreetly testify to the conflict. The delicate nature of this question makes it uneasy to treat in publications. The litigations are mentioned in an article accounting for the sales of Wols’s archives in 2011 (Koldehoff 2011). |

| 22 | Incredibly prolific, Audiberti had a hard time publishing his novels and poems at first. The manuscript of Infanticide préconisé remained in the drawers for almost twenty years (Fournier 2020, p. 120). |

| 23 | I am grateful to Bernard Fournier, the president of the Association des Amis d’Audiberti, who, having worked extensively on Audiberti’s correspondence archive at the IMEC (Caen) in view of the publication of his recent biography (Fournier 2020), confirmed this information. |

| 24 | “J’avais un vieil ami. Je connaissais les manigances et les rites par lesquels il conjurait son grade d’homme. Il était, parmi les êtres que j’ai connus, le moins enfoncé dans l’espèce. Il avait une lucidité qui lui faisait découvrir des techniques complexes destinées à améliorer le rythme de sa vie, et un ensemble de superstitions propres à le faire fonctionner plus en machine-plante que comme citoyen. Il était dans le tourbillon de l’air, l’homme l’ennuyait”. |

| 25 | For the sake of clarity, the titles translations are literal. |

| 26 | “les écoliers des sections littéraires connaissaient par cœur les noms des quarante académiciens, de même d’ailleurs que les noms des ministres des cabinets successifs. Kipling, d’Annunzio, Tolstoï structuraient l’univers littéraire international. Il y avait donc une sorte de chaleur et de sécurité dans la conscience qu’un jeune écolier pouvait avoir d’une organisation enfin réussie de l’univers, après les âges préparatoires, à savoir le grand siècle, le Moyen Âge et l’Antiquité. Cette sensation du monde moderne absolu est aujourd’hui extrêmement menacée. Je crois même qu’elle n’existe plus”. |

| 27 | Though in this passage Siegel comments on the American context, her interest in Wols along these lines is confirmed by a text published in the Bremen/Houston retrospective of Wols (Siegel 2013). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slavkova, I. “Cemetery=Civilization”: Circus Wols, World War II, and the Collapse of Humanism. Arts 2020, 9, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030093

Slavkova I. “Cemetery=Civilization”: Circus Wols, World War II, and the Collapse of Humanism. Arts. 2020; 9(3):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030093

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlavkova, Iveta. 2020. "“Cemetery=Civilization”: Circus Wols, World War II, and the Collapse of Humanism" Arts 9, no. 3: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030093

APA StyleSlavkova, I. (2020). “Cemetery=Civilization”: Circus Wols, World War II, and the Collapse of Humanism. Arts, 9(3), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9030093