1. Whose Streets?

This essay reframes street photography in terms of the images and videos taken by bystanders who find themselves witness to egregious acts of state-sanctioned police violence against black and brown bodies in the United States. Along the way, it challenges the belief that bystanders are “innocent” observers and investigates the meaning of “evidence” as well as the role of representation in order to argue for a model of seeing that can simultaneously reveal moments of ongoing racial debilitation and work to create new political subjects capable of transformative collective action. The goal is twofold: (1) to disrupt a history of photography—and more specifically a history of street photography—that emphasizes innovation, biography, and universal experience;

1 and (2) to reorient what it means to discuss the politics of the image (in particular, the digital “documentary” image) away from a discourse that either privileges “uncertainty” or understands images as empty simulations, and toward one that acknowledges representation’s complexity but also its ongoing power.

George Holiday’s amateur video of the beating of Rodney King (

Figure 1), first broadcast on Los Angeles’s local television station KTLA in 1991, exemplifies the kind of bystander imagery examined here. The tape captures four policemen beating King, an African American motorist, and, just as devastatingly, more than 15 others standing around watching. By now the video has been written about extensively—in large part for how the Los Angeles Police Department’s defense attorneys successfully parsed, re-framed, and re-contextualized its images, helping to secure an innocent verdict for the involved officers. The Rodney King beating video was remarkable, yet it signaled only the beginning of what has become a steady stream of bystander or witness videos that reveal similarly horrific moments of police violence, targeted bodily assault, and abuses of power.

2The term “bystander,” employed to describe an approach to taking pictures in public, was made popular by Colin Westerbeck and Joel Meyerowitz in 1994 after the publication of their book,

Bystander: A History of Street Photography.

3 Recently asked about the choice of title, Westerbeck explained, “Part of the appeal was that the term

bystander is usually prefaced by the word

innocent. So and so was an ‘innocent bystander.’ … The point was to leave implicit … the idea of a certain kind of innocence. This is fun, this is interesting, this is a kind of acceptable satire of the human race” (

Westerbeck 2019). By contrast, I eschew the idea of innocence in favor of social embeddedness; embeddedness allows us to understand how those who make witness videos, as well as those portrayed in them, exist together, in and as part of a larger system.

4 The bystander is embedded in the image, even if not pictured. There is no outside, no innocence.

To this point, as an increasing number of individuals/bystanders take pictures showing instances of police violence and the persistence of injustice, organizations like WeCopwatch have begun to train activists on how to gather video of police activity in local neighborhoods with precisely this kind of embeddedness in mind.

5 Just think of how WeCopwatch frames its mission not (solely) in terms of providing evidence for review boards and courtrooms, but also in terms of creating new kinds of communities of care. “We stand against white supremacy, racism, sexism, violence against women, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, and any other form of collectivized hatred or bigotry.” “As a small collective,” they continue,

we realize that the only way to make police obsolete is to not perpetuate their behaviors, and to live in such a manner where people no longer rely on police. At WeCopwatch we choose to deal with incidents or patterns exhibited by our members/allies/team in a manner that can help an individual understand how their mindset or actions hurt or impact others.

6

Taking my cue from WeCopwatch, and considering the meaning of social embeddedness, my concern is not just with individual instances and/or recordings of police brutality, but with a broader orientation of our relation to the kinds of public displays of death and beating that images taken by WeCopwatch and other bystanders reveal. How can making visible the structural conditions of state sanctioned violence allow us, implore us, to imagine alternatives to it?

Street photography conceived or re-framed here is thus understood as an extended space, open to new narratives, temporal orderings, and interpretative approaches. It rejects the glorification of any single moment as somehow instantaneously self-evident, or, on the other hand, as wonderous and fleeting. The model of street photography argued for here can initiate rebellion and provide evidence—evidence not of specific acts, or not primarily of this—but of a rigged system.

2. Witness to Brutality

On 9 August 2014, police in the city of Ferguson, Missouri, shot and killed Michael Brown, an eighteen-year-old African American teenager who, at the time of his murder, was unarmed, and according to witnesses, had his hands held up in a gesture of surrender. A grand jury failed to indict Darren Wilson, the policeman who shot Brown, and riots broke out in the city.

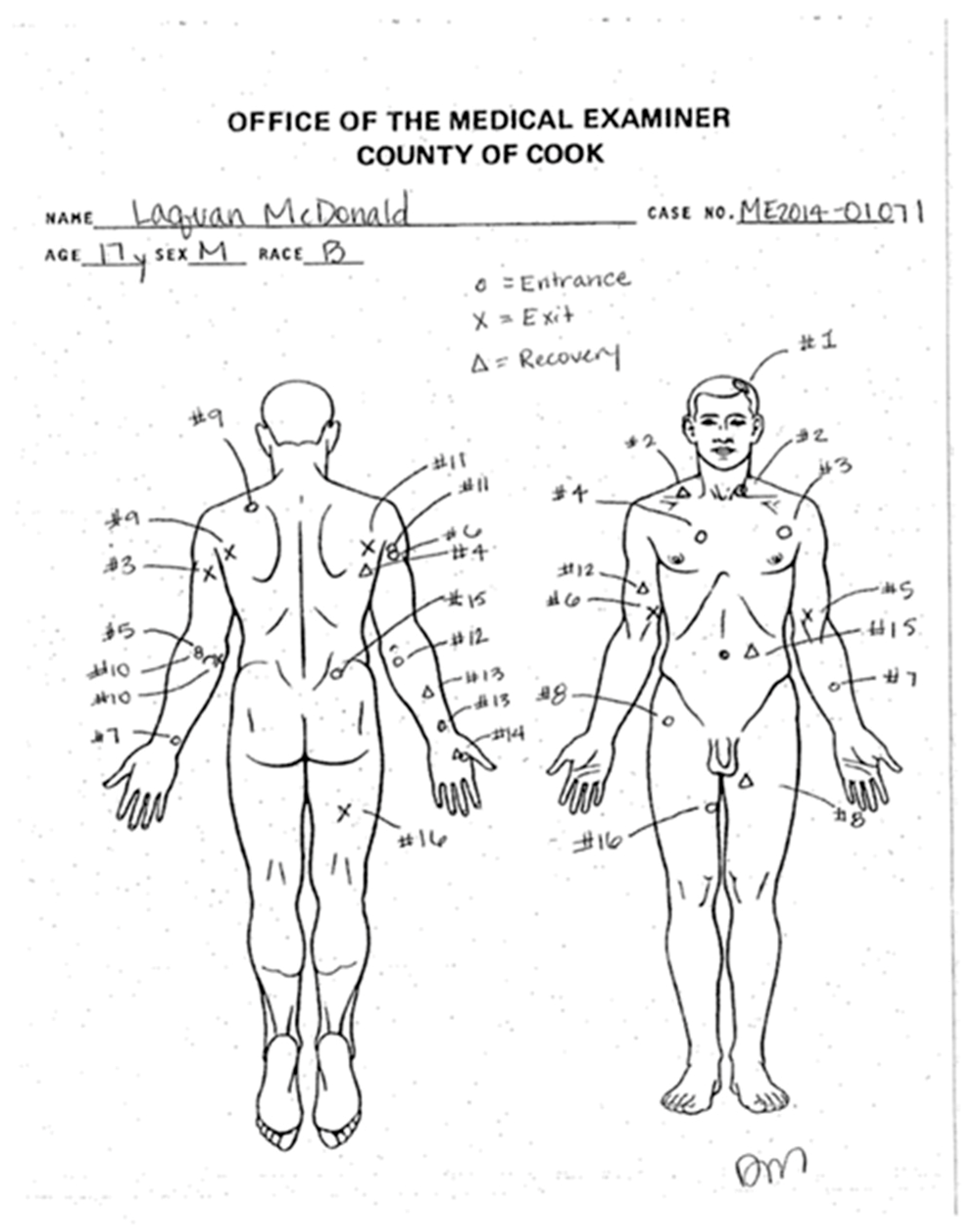

7 For weeks, the confrontation between protesters and law enforcement officers continued, and at least a dozen buildings were set on fire around the city. The pain and infrastructural damage experienced in Ferguson, however, did not seem to serve in any way as a cautionary tale. Since Brown’s murder in Ferguson, there have been a slew of deaths involving Black Americans and law enforcement, including high profile cases like Laquan McDonald in Chicago, Illinois who was shot sixteen times in a firestorm of bullets in October 2014 (

Figure 2); or Tamir Rice, a twelve-year-old child who was shot in a park in front of a recreation center in Cleveland, Ohio while playing with a toy gun in November 2014; or (and this occurred shortly before Brown’s death in July 2014) Eric Garner in Staten Island who was handcuffed, and then choked to death for selling loose cigarettes on the street. Another relevant case is that of Freddie Gray, who died mysteriously while in police custody in Baltimore, Maryland, in April 2015. Or Sandra Bland, who was found hanged in a jail cell in Waller County, Texas, three days after being arrested for a traffic stop in July 2015. The list could go on. Walter Scott in Charleston, South Carolina was shot dead in April 2015 while running away after a routine traffic stop; E.J. Bradford Jr., a 21-year-old man, was shot three times from behind at a mall on Thanksgiving Day 2018 in Hoover, Alabama; Eric Logan was shot dead by a white police officer in South Bend, Indiana, in June 2019. Nationwide, in the year 2017 alone, police shot and killed nearly 1000 persons in the United States.

8In all these instances, police either embraced an “allow-to-die” attitude or, more directly, simply shot to kill with such a complete and utter disregard for human life that their actions can only be described as murderous. In the United States, such actions have turned the public into a population of witnesses, witness to the violent death and debilitation of individuals whose inevitable demise is assumed by racial capitalism and social oppression (

Puar 2017, p. xviii); witness to police harassment and brutality as it operates on a granular level, permeating the everyday lives of Black Americans; and witness to the ways in which white hegemony works to organize and manage our vision.

I emphasize the word “witness” here to highlight the fact that most of the police violence and arrest related deaths mentioned thus far have been caught on video, recorded by either bystanders using cell phones or police dashcams.

9 Police violence is nothing new, but the presence of videos recording that abuse, combined with those videos’ quick distribution online, distinguishes the recent past from prior moments. Indeed, the sheer volume of witness videos of police brutality that have surfaced in the past five years alone paradoxically suggests that many more instances of abuse occur, just remain unseen. Still, the immediate result of all the existing recording and online posting is that many Americans (and others around the world) have seen passages of black death at the hands of police that otherwise would have remained unarticulated.

In Ramsay Orta’s recording of the murder of Eric Garner, for instance, we witness Mr. Garner’s vulnerability in the environment of racial capitalism’s necropolitics as he is confronted by the brutal and reckless exercise of police power. “I can’t breathe,” he tells the cops who illegally choke him, a phrase that has since become a rallying cry for Black Lives Matter and other social justice movements. The still image from Orta’s video of Mr. Garner lying on the ground, surrounded and contained by police, similarly serves as a visual reminder of Mr. Garner’s precarity, the realities of racialized policing, and the biopolitics of debilitation (

Figure 3).

However, Orta’s video, more than any single still image, is also revealing for how it shows the moments before the attack. That is, as if preparing for something bad to happen, Orta begins to film well before police use the illegal chokehold that eventually kills Mr. Garner. In these moments, for more than 30 seconds, we hear Mr. Garner explain to the police: “Every time you see me, you want to mess with me. I’m tired of it. This stops today. What are you bothering me for … I didn’t do nothing ... I’m just standing here … I did not sell nothing. Because every time you see me, you want to stop me, you harass me…I’m minding my own business, officer. I’m minding my own business; please just leave me alone.” His pleas are ignored; two officers approach him, and soon we hear, “Don’t touch me, don’t touch me, please.” Then, one officer, Daniel Pantaleo, puts Mr. Garner in a chokehold and takes him down to the ground. Eleven times Mr. Garner’s voice can be heard: “I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.” Until he stops breathing.

10 In watching Mr. Garner speak to the police who later assault him, we are shown the thick atmosphere of anti-blackness that results from the ways in which white supremacy seeks to organize our senses.

Multiple videos exist of Freddie Gray’s arrest in Baltimore, but the recording that first brought national attention to the brutal treatment Mr. Gray endured at the hands of police, treatment that led to his eventual death, was filmed by Kevin Moore.

11 Unlike Ramsay Orta’s recording of Mr. Garner, this video begins in the middle. When Moore arrives on the scene, Mr. Gray has already been tased and incapacitated. He lies on the pavement, his legs are twisted awkwardly behind him. He screams in apparent agony as three officers drag him into a police van because he cannot move or control his legs on his own. He screams in agony again. Mr. Gray asks for medical attention; it is not provided. The police van leaves, but stops just a short distance from the site of arrest. Here, Mr. Gray’s ankles are shackled. The van departs once more. The recording ends, but at some point during transport, Mr. Gray falls into a coma and is taken to a trauma center where he dies one week later. The Baltimore medical examiner’s office ruled Gray’s death a homicide, citing the failure of officers to follow safety procedures “through acts of omission” (

Fentin 2015). Freddie Gray, in other words, was allowed to die.

A year after Mr. Gray’s death, Moore reflects, “I never in my life woulda thought that I filmed the last few minutes of Freddie’s life, the last few minutes of him breathing, of his life.”

Moore (

2016) continues, “I hear it every night. Still. I hear the screams every night. ‘I can’t breathe, I can’t breathe, I need help, I need medical attention.’ This is the shit that play in my mind over and over again.” From the trauma of the singular instance—here the event of Freddie’s Gray’s arrest—to the ongoing-ness of Moore’s efforts to manage the ordinary work of living on in a state of being worn out, the video of Freddie Gray reveals not only the emergency moment of police violence, but also the way in which death is durational for those lives slated for inevitable injury.

Lauren Berlant (

2007, pp. 759, 762), in an essay on “slow death,” employs that phrase to describe “a condition of being worn out by the activity of producing life. … While death is usually deemed an event in contrast to life’s ‘extensivity,’ in this domain dying and the ordinary reproduction of life are coextensive.”

12 The mixed temporalities that define Berlant’s “slow death,” then, might also be understood as characterizing Moore’s video, and I would argue, other similar bystander videos that reveal how the prolonged history of police brutality in the United States creates a system of durational incapacity that makes an ongoing awareness of death a way of life for black and brown Americans.

Power is made visible on the body in these videos, on the body seen (Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Rodney King, etc.) and on the body imagined for the future or remembered in the past. In this way, I would further argue, the various ways that (state) power is pressed onto the body constitutes part of the indexical mark that matters most in these witness videos. Charles Peirce’s semiotic concept of the index is typically understood as a material trace of a past moment of physical contact that provides evidence—proof—of an existential truth. In the case of (analog) photography, this physical contact consists of “marks” physically made by light on the chemical emulsion of photographic paper. But when Peirce writes about indices, most of his examples are not as legible as a photograph. “A rap on the door is an index,” Peirce writes, “Anything which focuses attention is an index. Anything which startles us is an index, in so far as it marks the junction of two portions of experience. Thus a tremendous thunderbolt indicates

something considerable has happened, though we may not know precisely what the event was” (

Peirce 1992, pp. 108–9;

Paulsen 2017, p. 29) In Peirce’s words, indices are “symptoms,” or as Kris Paulsen describes, “clues that point to something not yet known or to something one can’t be sure of.” “The great achievement of the index,” she continues, “is its ability to signify without the benefit of convention, resemblance, or direct observation. This ability comes from the thought process it activates in the receiver” (

Paulsen 2017, p. 29). More than just the registration, or indexing, of physical abuse on the body, the witness videos produced by embedded bystanders, such as Ramsay Orta or Kevin Moore, can thus be understood as initiating in the receiver a thought process that points to how racialized bodily difference is at the core of how populations become stigmatized and vulnerable to both police brutality and reckless killing.

3. Images Do Not Speak for Themselves

In 2014, a few months after a Staten Island grand jury declined to indict Daniel Pantaleo for the brutal murder of Eric Garner, art historian

David Joselit (

2015a) wrote a short article for

Artforum claiming that this decision evidenced a failure of forensis. Concerned about what such a decision signaled about the efficacy and promise of representation, particularly with regard to future representations of abuse, Joselit asks at the beginning of his text, “If the excruciating video showing Garner seized and relentlessly piled on by the police could not convince a jury, how can forms of aesthetic critique based on research and visual evidence be any more effective with a general public?” Joselit continues:

[H]ow can we account for the fact that the video of a police officer pressing his arm against Garner’s throat—a document that could not have been less ambiguous—did not ‘speak for itself’ before the members of the grand jury? If such a visual artifact can so blatantly fail in the task of representation before the law, both politically, as the proxy for an absent victim, and rhetorically, as evidence, doesn’t this present a challenge to how we define the politics of art? ... I am suggesting, then, that with regard to the Garner case, as well as to our own affairs in the art world, we need to be more skeptical of the ideological promises of representation.

(Ibid.)

A number of critics have taken Joselit to task for this overly simplified interpretation.

13 On the most basic level, there is something ridiculous in trying to move immediately (in an unmediated way) from a photograph to an outcome, such as a grand jury outcome in cases like those addressing the murders, at the hands of police, of men like Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and Michael Brown, or boys like Tamir Rice. Moreover, 25 years after the failure of George Holiday’s Rodney King beating video to help generate a conviction for any of the involved Los Angeles County policemen, the inability of seemingly uncontestable photographic evidence to sway juries should certainly come as no surprise. In 1993, Judith Butler, writing about Holiday’s video in words that still ring true today, explained that for the jurors, the video was not about “simple seeing, an act of direct perception, but the racial production of the visible, the working of racial constraints on what it means to ‘see’”(

Butler 1993, p. 16). She continues,

The attorneys [for the defense] proceeded through cultivating an identification with white paranoia in which a white community is always and only protected by the police, against a threat which Rodney King’s body emblematizes, quite apart from any action it can be said to perform or appears ready to perform. This is an action that the black male body is always already performing within that white racist imaginary, has always already performed prior to the emergence of any video. The identification with police paranoia culled, produced, and consolidated in that jury is one way of reconstituting a white racist imaginary that postures as if it were the unmarked frame of the visible field, laying claim to the authority of “direct perception.”

(Ibid., p. 19)

Or to explain this another way: attorneys for the four white officers charged with beating Mr. King—Stacey Koon, Theodore Briseno, Timothy Wind, and Laurence Powell—used Holiday’s video as part of their defense, but only individual freeze frames that distorted King’s movements, which allowed them to label King with a series of stereotypes (“buffed-out,” “bear-like,” “aggressive,” “combative,” “like a wounded animal”).

14 In this distortion, the individual history and experience of King’s body in the abuse event was erased and supplanted with, as

Elizabeth Alexander (

1994, p. 80) points out, white male victimization.

In 2015, author and television commentator Mychal Denzel Smith made a similar observation about why video evidence was not enough to indict Timothy Loehmann, the officer who killed Tamir Rice in Cleveland. Smith explains (in language more blunt than that used by Butler or Alexander), “The video didn’t matter [to the prosecutor], because killing black people is not a crime. The police are not afraid of cameras, because the cameras only capture the police doing their jobs. ‘Serve and protect’ as popularly understood, is a myth. For the police, to serve means to use violence, including lethal force, at their discretion at any time, and to protect means to validate the threat of blackness born of the racist imagination. … Killing black people is not a crime. Instead it is the basis of American identity” (

Smith 2015). A poster at a demonstration protesting Tamir Rice’s murder in Cleveland articulates this same analysis in the most direct way possible: “TAMIR RICE. 12 YEARS OLD—MURDERED BY COPS. THE WHOLE DAMN SYSTEM IS GUILTY!” (

Figure 4). A cut-out picture of Tamir—a boy, not even a teenager—fills the top half of the poster, which is held in this photograph by an older woman whose own image aligns perfectly with his. Viewed together, the two faces speak to time passed: Tamir’s lost time and her endured time. The relationship drawn between the murdered child and surviving adult (perhaps a mother herself) reveals further the importance of seeing images of police brutality in an expanded field (street photography re-framed) that includes narrative multiplicity and temporal disjunct, the epidemic and the endemic together, the emergency moment viewed in conjunction with population and resource management systems that act over extended periods to sap people of their energy, strength, and sovereignty. Understood as such, no single police attack or its recording can be viewed only as a stand-alone event, but rather must be interpreted as part of a collection of events and images that together articulate both assemblages of power and voices of resistance.

Indeed, within this expanded field, the very act of recording cases of police brutality should be understood as itself a kind of public refusal, an uncooperative mode of engagement that demands a shift in discursive exchange between the police and the policed (

King 2017, p. 164). After Kevin Moore’s recording of Freddie Gray went viral, WeCopwatch helped Moore establish a WeCopwatch chapter in his West Baltimore neighborhood. Shortly thereafter, Moore was asked how the police have responded to his persistent efforts to record their actions and to the presence of cameras. “I can keep [the police] at bay,” he explained, “keep them on a leash with just a video camera, it’s almost like … live rounds, bullets from a gun when you put a camera in a cop’s face and he sees you … at first his mindset was, ‘oh I can do whatever I want, and I’m a police and I’ll get away with it, but once he sees a civilian recording and it is raw footage and not CCTV [closed circuit tv], which can be tampered with, or a body camera, which can be tampered with, when it’s raw…it means so much more” (

Moore 2015).

15Moore’s description, which analogizes his own camera-wielding to pointing a gun (“it’s almost like live rounds”) recalls Susan Sontag’s assertion that taking photographs is an aggressive act. Photography is “a tool of power,” Sontag writes in “In Plato’s Cave.” The camera can “presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit, and, at the farthest reach of metaphor, assassinate.” “There is something predatory in the act of taking a picture,” she claims. “To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed” (

Sontag 1997). In the mid-twentieth century, this aggressive approach to picture making, along with its attendant gritty realism, sense of intrusion and public spying was, as

Patricia Vettel-Becker (

2005, pp. 64–65) notes, “appropriated by those whom we now refer to as street photographers and who have been canonized as major figures in the history of postwar photography”. Vettel-Becker goes on to argue that by combining the realism of photojournalism and social documentary with the individual subjectivity of modernism, street photographers effectively constructed both professional and masculine identities. “As such,” she declares, “postwar street photography became the aesthetic of existentialist man—highly individualized, stripped of political ideology, experiential… privileging the photographer’s subjectivity over the historical conditions surrounding the subject matter” (ibid.). Moore’s explanation of his camera as possessing a power similar to that of a gun acknowledges the aggression identified by Sontag and analyzed by Vettel-Becker, yet his position—both as a black man and as a subject embedded in the recordings he makes—controverts that aggressive, masculinist identity and apolitical stance. Refusing to become a docile subject, acting with urgency to resist the violent control of his neighborhood by police via targeted bodily assault, Moore’s approach demands that he, as well as those he records, be acknowledged in public space. Jasbir Puar explains that part of the power of the common Black Lives Matter chant “Hands up, don’t shoot!” is that it functions as “a compact sketch of the frozen black body, rendered immobile by systemic racism and the punishment doled out for not transcending it” (

Puar 2017, p. xxiii). Moore’s portrayal of his camera as a powerful weapon might thus also be seen in terms of mobility; the camera unfreezes his body.

Moreover, the constant reiteration of video recordings, such as Moore’s of Freddie Gray, has in fact had a cumulative effect on how police violence is understood and addressed by state bodies, including the judiciary. Just a few months ago in Chicago, Jason Van Dyke was found guilty of second-degree murder and 16 counts of aggravated battery in the case of Laquan McDonald, a verdict arrived at only after activists demanded the release of dashcam video that showed Mr. McDonald walking away from police, imagery that directly contradicted Van Dyke’s recounting. Or consider the recent ruling of an administrative judge in New York City that found Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who murdered Eric Garner, guilty of violating a department ban on chokeholds—a ruling which led to Pantaleo’s dismissal from the New York City Police Department.

16 I am absolutely not arguing for a war of images, or that more and more video evidence will automatically solve the problem of police violence, or that countering police aggression with the aggression of a camera will somehow solve the problem of police brutality, but I am saying that scholars and critics can be too quick to proclaim the failure, or even the end, of representation.

17I am thinking here not only of Joselit, but also Hito Steyerl’s identification of our current moment as post-representational. A startling passage in her essay “Documentary Uncertainty,” for example, describes the moment she saw a 2003 CNN broadcast of the US invasion of Iraq in which the correspondent gleefully showed images from his cell phone that, due to the camera’s low resolution, were essentially abstract and thus did not actually show anything at all (

Steyerl 2011). The closer to reality we get, this line of argument asserts, the less intelligible many contemporary documentary pictures become. In other places, Steyerl writes about relatively new technologies like the lenses on cell phone cameras, which are tiny and it turns out not great at capturing data. To make images complete, Steyerl explains that phones fill in missing data by using algorithms that refer to other “photographs” on a given device. We can think of these sorts of cell phone images, then, not as actual depictions of the world around us (in a traditionally conceived sense that posits the index as a material trace of a past moment of physical touch), but rather as representations of what our cameras think or believe we may have seen or want to see.

18Steyerl is very convincing, and even as I find it difficult to disagree with her analysis, I am unwilling to say that we are in a post-representation moment, or that representation (or indexicality) no longer exists or cannot affect viewers in meaningful ways.

19 To this point, one might reflect not only on the recent (and growing) archive of police violence videos, but also, from a slightly earlier moment, on the cell phone images taken by US military personnel in Iraq in 2004 during the US’s second Iraq War.

20 While these images revealed how the American military physically tortured, sexually abused, and committed human rights violations against detainees in the Abu Ghraib prison, some critics characterized the American response as apathetic and morally blind.

21 I believe that assessment is wrong. On the one hand, yes, there is no question that any critical observer cannot help but to be appalled by the American public’s relatively passive reception of the Abu Ghraib images. However, on the other hand, this point should not be exaggerated. Reports of torture and mistreatment in American detention facilities had been leaking out for at least a year prior to the revelation of the pictures, so the images did not reveal totally new information. More importantly, whatever disciplinary action taken by the military and whatever political consequences experienced by the Bush administration—and in retrospect, many would argue the Abu Ghraib images significantly contributed to the decline in American support for the war—are the direct result of the images becoming public and of the public reacting precisely with moral outrage.

Therefore, phenomenologically, as digital pictures, the Abu Ghraib images, or cell phone recordings of police brutality, exist without negatives and with infinite potential for mass distribution. Yet, even as digital images, which have been theorized as a kind of fiction, as “photographic” pictures divorced from reality, these images still have presented themselves as a legally actionable trace of the real, and retain, to use Roland Barthes’s psychoanalytically inflected term, a

punctum, or visual shock that is capable of striking the viewer with great force. Barthes’

punctum is a useful term here because it provides a helpful way of understanding the photograph’s relationship to “the real.” It is also connected to what Barthes identifies as “the

This” of photography. “The

This” relies on an idea of touch (just as does Peirce’s indexical mark), but not physical touch. Rather, touch for Barthes, and here I quote from Paulsen, “is the effect the photo has, the way

it touches him. ‘The

This’ is not made by touching; it is instead a thing that touches, whose effect is largely separated from the depictive qualities of the photograph” (

Paulsen 2017, pp. 25–27). In other words, for Barthes, photographs point to something other than and beyond what is depicted. Barthes writes,

The second element [of the photograph] will break (or punctuate) the studium. This time it is not I who seek it out (as I invest the studium with my sovereign consciousness), it is this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow and pierces me. A Latin word exists to designate this wound, this prick, this mark made by a pointed instrument. … This second element which will disturb the studium I shall therefore call punctum, for punctum is also: sting, speck, cut, little hole. … A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me.”

Again, as Paulsen points out, in some ways this is a curious description of a photograph because it focuses on the relationship between the sign and its viewer, not the sign and its referent. That is, in Barthes’ account, the photograph becomes an active agent that calls out to the viewer in the imperative, “See here!” “Look at this!” Moreover, the

punctum, as it reaches out (as it stings, pierces, pricks, and bruises the viewer), it also initiates, what Paulsen identifies as, “a chain of associative and exploratory thoughts.” Like Peirce’s characterization of the index as a “symptom” that indicates something not yet known, “the

punctum,” in Paulsen’s words, “‘expands’ and points to something ‘beyond’ what is merely represented” (

Paulsen 2017, p. 27). Considering Barthes’ terms, as well as Paulsen’s analysis, in relation to how bystander, dashcam, and even media imagery has been used to build popular resistance movements (e.g., Black Lives Matter), or remove politicians from office (e.g., Rahm Emanuel in Chicago), or simply imagine more just futures, including the destruction of white supremacist culture (e.g., Kevin Moore and WeCopwatch), it seems both shortsighted and limited—too removed from the street—to discount out of hand representation’s ideological promise. For in these instances of activist uprising, it is precisely the photographic or recorded image’s ability to point, to demand one to “Look at this!” and then see beyond what is merely shown, which instantiates the radical call for redressing or at least confronting the debilitating logic of racist policing.

4. Evidence, Image, Voice: Street Photography Re-Framed

Street photography as re-framed here functions in a multifaceted representational and documentary mode; reconceived, the genre provides a heterogeneous array of information, sensible experience, and allegorical meanings capable of addressing complexity and providing ways to address the ruins of racial capitalism. Reconceived, it also allows a way forward, a way to think about future life outside the chronic debilitation of state-sanctioned infrastructural violence. It is not representation, or its ideological promise, that has failed us, I would argue, so much as our system of justice: laws that grant police excessive rights, juries that identify with police, and the ongoing assemblages of power that maintain the precarity of certain bodies and populations by making them available for maiming.

22 “The whole damn system is guilty!” reads the poster protesting Tamir Rice’s slaughter.

Sunil Dutta, a seventeen-year veteran of the Los Angeles County police force, however, has a different explanation for the continued brutal exercise of power by the police. For Dutta, representation has not failed, nor is the system guilty. The problem is disobedience. In a

Washington Post editorial from 2014, Dutta advises, “[I]f you don’t want to get shot, tased, pepper-sprayed, struck with a baton or thrown to the ground, just do what I tell you. Don’t argue with me, don’t call me names, don’t tell me I can’t stop you, don’t say I’m a racist pig, don’t threaten that you’ll sue me and take away my badge. Don’t scream at me that you pay my salary, and don’t even

think of aggressively walking towards me. Most field stops are complete in minutes. How difficult is it to cooperate for that long?” (

Dutta 2014). In other words, citizens should be properly deferential to authority and those who refuse to submit deserve the pain they will receive.

In “Criminal Procedure and the Good Citizen,” critical legal studies scholar Bennett Capers analyzes a number of Supreme Court criminal procedure case rulings that provide some context for Dutta’s opinion: “The normative message from the Court,” Capers argues, “is that the good citizen should feel comforted by the presence of officers.” “Good” citizens don’t run from police, “good” citizens gladly consent to searches, welcome police surveillance, waive their right to silence, and even at times their right to speak, all because they have nothing to hide (

Capers 2018, pp. 666–67). However, in his text, Capers also begins to dream of a space where citizens would have the ability, without repercussion or recrimination, to talk back to the police, where they could assert their rights and test the boundaries of the law, a space in which citizens could say “no.” Capers’ interests lay in imagining a legal space that recognizes the value of citizen dissent and where equality extends to the relationship between citizens and police (ibid., p. 706). The insistence here is on establishing dialogue with the state rather than accepting the state’s voice as a monologue. This quality also characterizes the work of witness recordings of police violence.

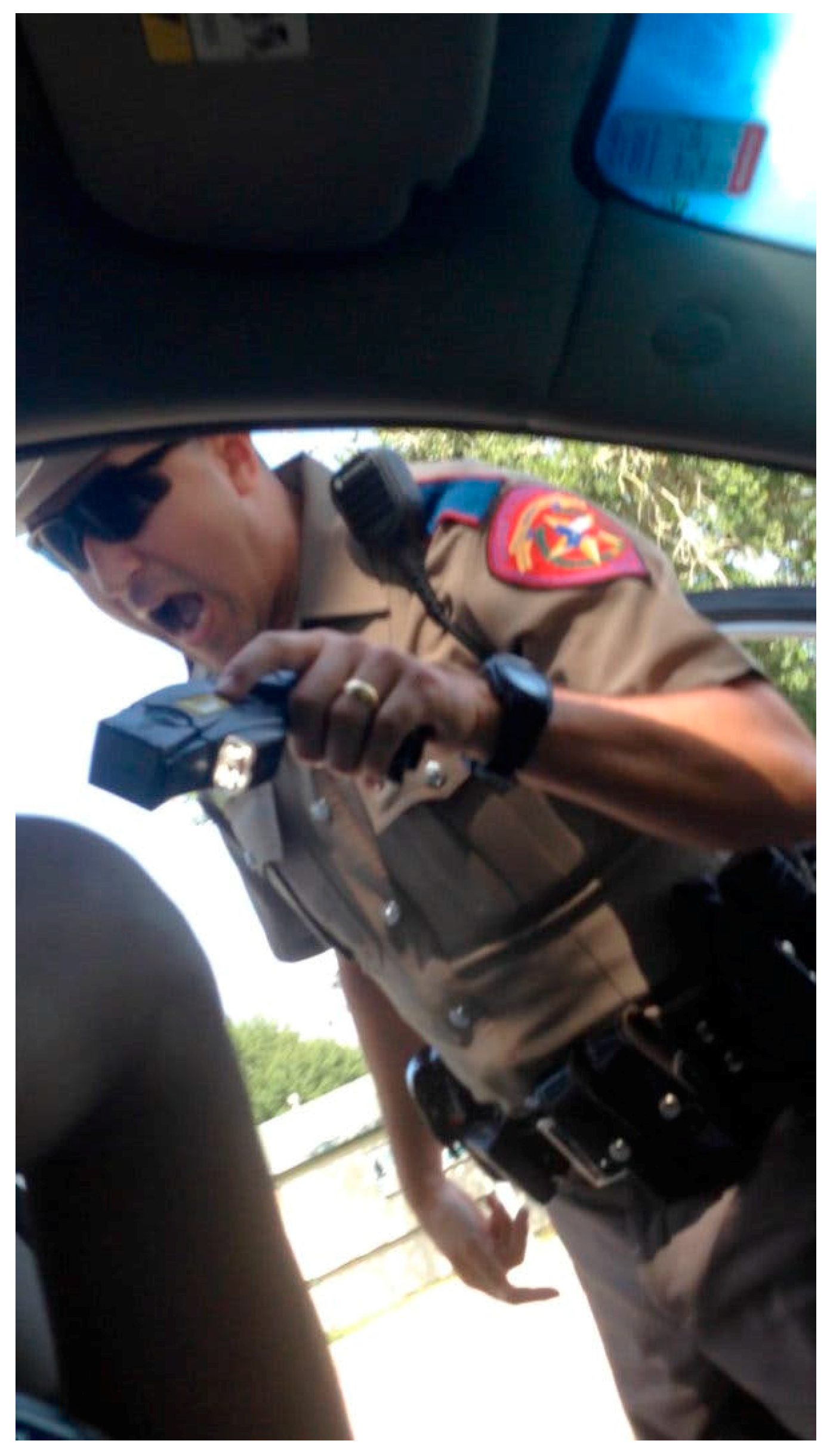

Kevin Moore’s description of how police react when he aims a camera at them begins to get at this point. The case of Sandra Bland provides further insight: On 10 July 2015, Texas State Trooper Brian Encinia pulled over a 28-year-old African American woman, Sandra Bland, for failing to use a turn signal. During the stop, Encinia asked Ms. Bland to put out her cigarette. She did not comply. Instead, asserting her presence, knowing her own voice, and insisting on dialogue, she asked the officer: Why? Why did she have to put out her cigarette when she was in her own car? A simple question, yet it prompted the trooper to aggressively remove her from the car and to see her, as described above, as a disobedient citizen. The exchange escalated, Ms. Bland was arrested, and a few days later found dead hanging in her cell. Her death was officially ruled a suicide. However, nearly four years after her death, a cellphone video, produced by Ms. Bland herself at the time of her arrest, was publicly broadcast (

Montgomery 2019). On that video, viewers get a sense of the traffic encounter as she experienced it: the recording reveals a close up view of Encinia, shouting, fuming at being defied, enraged at being challenged. He pulls out a stun gun and orders her to get out of the car (

Figure 5).

23 “I’m going to light you up!” he yells. He is irate and out of control; the state’s monologue has been interrupted. However, she continues to speak: when he threatens her with his taser, she retaliates with her camera, a gesture understood, as are her words, as inappropriately aggressive. Vettel-Becker describes street photography as a bodily practice, “one that seeks to signify the photographer’s masculine physicality and subjectivity without turning him into an object” (

Vettel-Becker 2005, p. 84).

24 Bland’s crime here was not her failure to use a turn signal, but her audacity to claim her own subjectivity. In so doing, she resisted the dominant ways that black women are supposed to know and look, to occupy what bell hooks identifies as “the oppositional gaze.”

25 With her voice, her camera and her physicality, Sandra Bland produces Encinia’s body, rather than the other way around.

Watching this video, it is as if Ms. Bland’s ghost has emerged from the dead, been re-animated, and is now speaking back to the future. In other words, Ms. Bland’s voice, through her video, brings the future to bear on the past, and the past to bear on the future or possible futures, undoing linear temporalities that always seem to aid authority, and revealing long-standing and ongoing avenues for disciplining bodies that resist debilitation or that refuse to become docile.

The video in this sense might be understood as disrupting the state’s attempt to manage visuality. Visuality used here in Nicholas Mirzoeff’s sense of the word, meaning the recording unsettles the way in which visual schema becomes, for the state or those in power, “both a medium for the transmission and dissemination of authority, and a means for the mediation of those subject to that authority” (

Mirzoeff 1992, p. xiv). However, also of equal importance is how the video, Ms. Bland’s—but also Ramsay Orta’s of Eric Garner and Kevin Moore’s of Freddie Gray, or so many other witness recordings of police violence and misconduct—functions as an earwitness. The state’s ear is unaccustomed to hearing “the simple vocal self-revelation of existence,” philosopher Adriana Cavarero claims. “The typical freedom with which human beings combine words,” she writes, “is never a sufficient index of the uniqueness of the one who speaks. The voice, however, is always different from all other voices. … This difference … has to do with the body” (

Cavarero 2012, p. 522). She elaborates, quoting fellow Italian writer, Italo Calvino, “‘A voice means this: there is a living person, throat, chest, feelings, who sends into the air this voice, different from all other voices. … A voice involves the throat, saliva.’ When the human voice vibrates, there is someone in flesh and bone who emits it” (ibid.). In the video made by Sandra Bland of her own arrest, we hear her voice, her insistence that she is here, and that she is human. Devocalization is part of the ongoingness of destructive debilitating state-sanctioned violence. It is part of the ruthless practice of determining who counts as a citizen, and a human, part of determining whose body matters and of framing humanity as an exclusive experience. “The category of human,” writes

Tiffany Lethabo King (

2017, p. 165), “is modified by identity in ways that position certain people (white, male, able-bodied) within greater or lesser proximity to humanness”. Sandra Bland’s video shows us her refusal to be devocalized even in the face of brutality.

Nevertheless, the capacity to inhabit futurity is a privilege (

Puar 2017, p. 152). This is part of what videos of police beatings and arrest related deaths show, and part of what Sandra Bland’s video painfully reveals. Of what we must face as we remember that Tamir Rice and Laquan McDonald were just boys when they were gunned down, their futures have already come and gone. The murderous ends suffered here are not some exceptional accident, but rather a predictable result and regular feature of violence imposed upon black and brown bodies by the carceral system. To use Christina Sharpe’s phrasing, this is part of Black life as it persists in anti-Black weather.

26 Yet, from this storm, is it possible to imagine a future that does not belong to a time of disaster? Can street photography reframed help build an expanded arsenal of images understood simultaneously as revealing moments of ongoing racial debilitation and as working to create new political subjects capable of transformative collective action? Can it become part of an articulated voice that speaks back to law enforcement and asserts rights in the face of a racist regime that demands submission? In the United States, we may never be able to tell a story in and about public space without replaying scenes of violence and targeted assault, but finding ways to let voices and images from the past, both tragic and redemptive, resonate in the present and speak to us in the future, may provide some way forward.