Street Photography Reframed

Afraid of contagion? Stand six feet from the next protester, and it will only make a more powerful image on TV. But we need to reclaim the street.

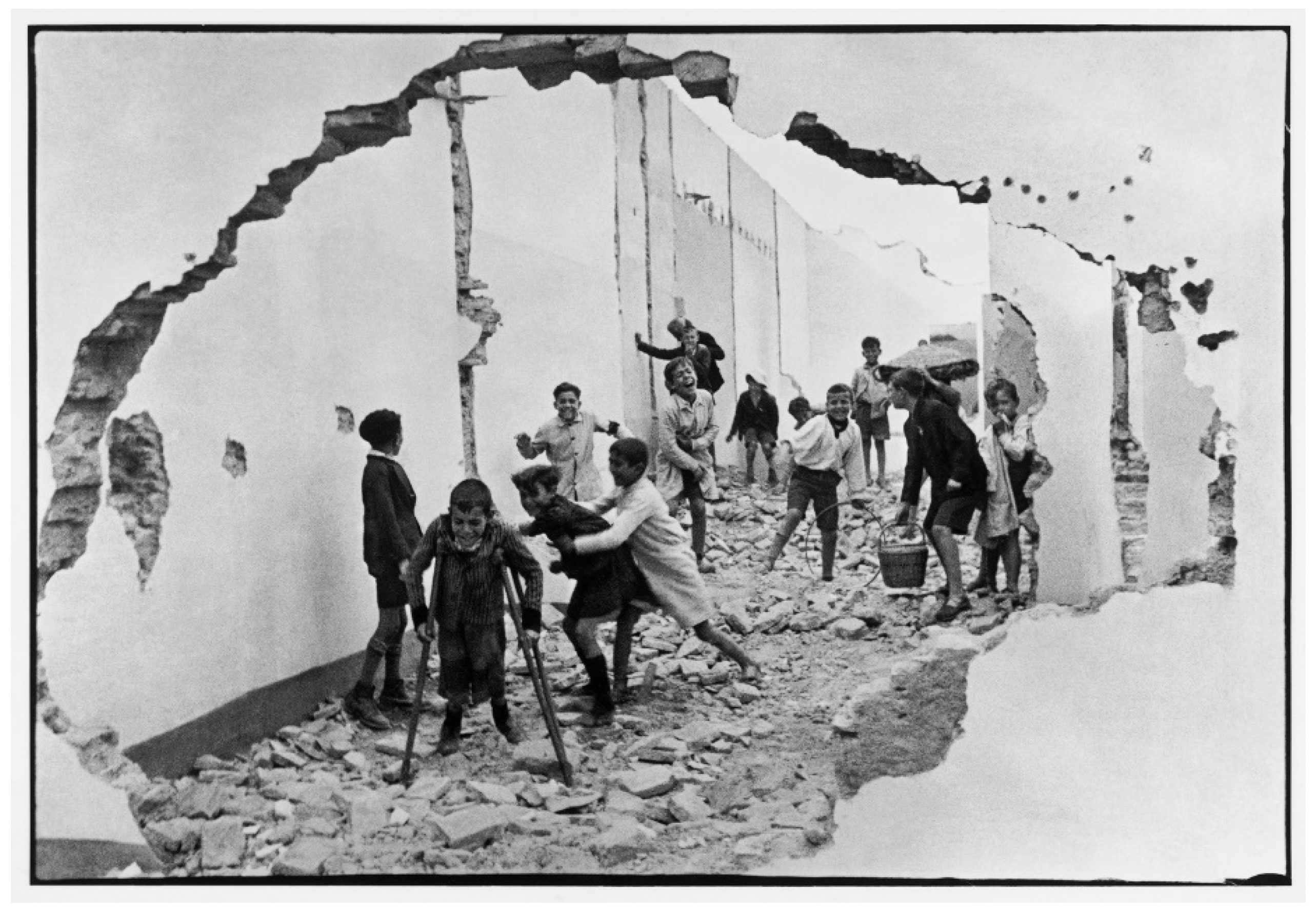

Written from Cartier-Bresson to Hugo or Manet and back again, the history of the genre becomes a story about the invention of the decisive moment. It is written in order to welcome Cartier-Bresson as much as make inevitable his arrival.[Cartier-Bresson] sees so many things we cannot that we wonder whether the street itself isn’t just the product of his imagination, as if he invented it the way that other Surrealist photographers invent their visions in their studios and their darkrooms. Yet in a sense it is the street that invented him. Life in the street, especially in Paris, has created a modern sensibility that photographers like Cartier-Bresson embody.

Cartier-Bresson is not “there.” He never was. He was always making a picture, framing a scene that was unrolling before his eyes. The street, as Benjamin dialectically defined it in the 1930s, when, notably, Cartier-Bresson was playing and pouncing and shooting, is conceived of as both a landscape and a living room.15 It is a space that can be and is already possessed.I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to “trap” life—to preserve life in the act of living. Above all, I craved to seize, in the confines of a single photograph, the whole essence of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.(Cartier-Bresson 1952, n.p.)14

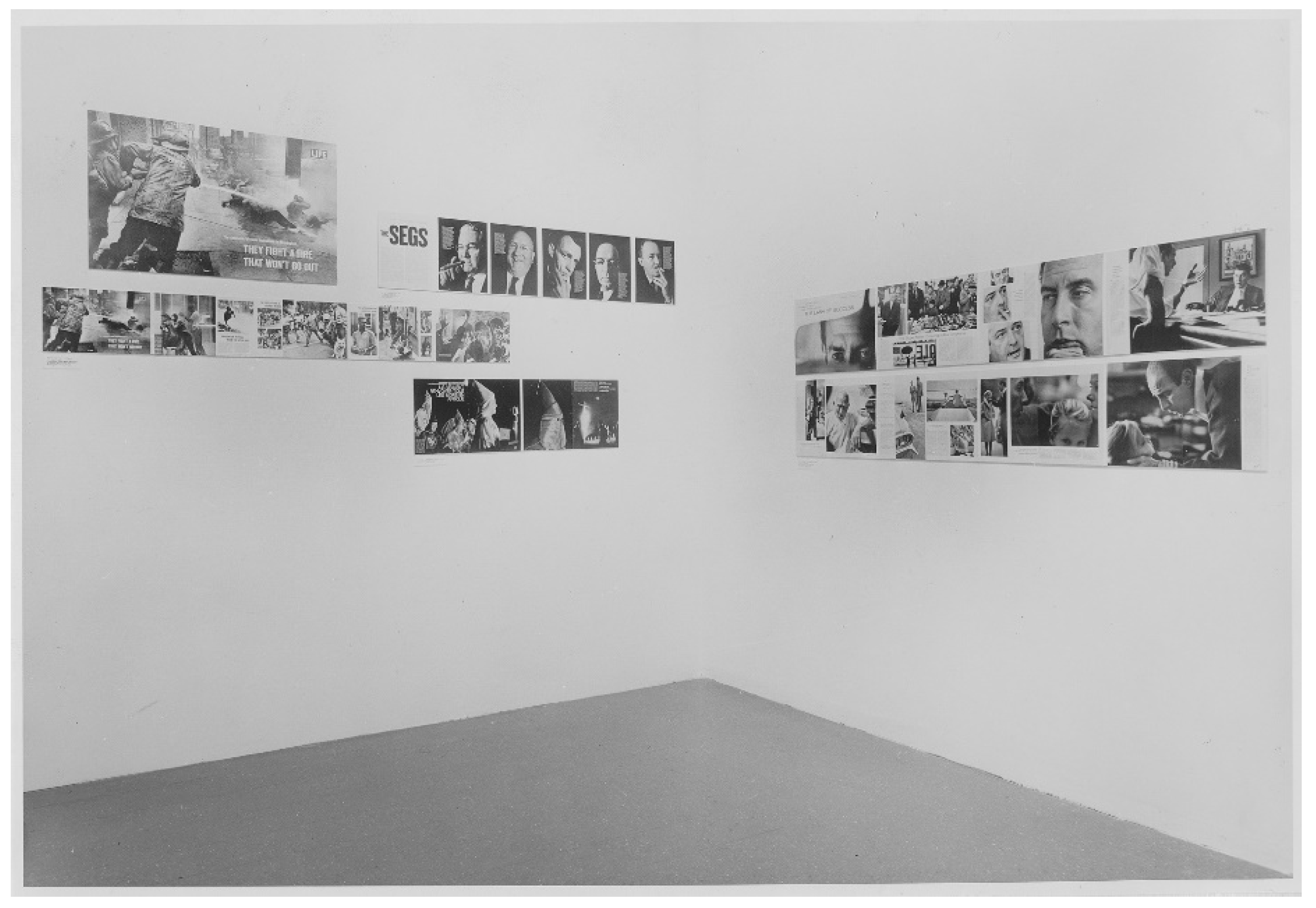

Photography could hold the war in Vietnam, but not as a news event. With Arbus’ penchant for the marginalized in hand, the shock of the war as much as the war itself, Szarkowski imagined, could be contained. Personalized, made subjective; it could also be made history.More recently, photography’s failure to explain large public issues has become increasingly clear. No photographs from the Vietnam War—neither Donald McCullin’s stomach-wrenching documents of atrocity and horror nor the late Larry Burrows’s superb and disturbingly conventional battle scenes—begin to serve either as explication or symbol for that enormity. For most Americans the meaning of the Vietnam War was not political, or military, or even ethical, but psychological. It brought to us a sudden, unambiguous knowledge of moral frailty and failure. The photographs that best memorialize the shock of that new knowledge were perhaps made halfway around the world, by Diane Arbus.(Szarkowski 1978, p. 13; emphasis added)

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2020a. The State of Exception Provoked by an Unmotivated Emergency. Position Politics. Available online: http://positionswebsite.org/giorgio-agamben-the-state-of-exception-provoked-by-an-unmotivated-emergency/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Agamben, Giorgio. 2020b. Clarifications. An und für sich. Available online: https://itself.blog/2020/03/17/giorgio-agamben-clarifications/ (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Bair, Nadya. 2021. Photo-Essays at Life. In LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography. Edited by Katherine A. Bussard and Kristen Gresh. Princeton: Princeton Museum University Art Museum, pp. 128–63. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1997. The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire. In Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Power in the Era of High Capitalism. Translated by Harry Zohn. London: Verso, pp. 9–106. First Published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Hannah. 2020. Go Outside. Artforum. Available online: https://www.artforum.com/print/202009/hannah-black-s-year-in-review-84376 (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Cartier-Bresson, Henri. 2017. A Reporter… Interview with Daniel Masclet. In Interviews and Conversations, 1951–1998. Edited by Clément Chéroux and Julie Jones. New York: Aperture. First Published 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Cartier-Bresson, Henri. 1952. The Decisive Moment. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Chéroux, Clément. 2014a. A Bible for Photographers. In Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment. Göttingen: Steidl, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chéroux, Clément. 2014b. Henri Cartier-Bresson: Here and Now. Translated by David H. Wilson, and Ruth Sharman. London: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, William. 2020. ‘It’s Eerie’: Capturing the Emptiness of Paris, a City Under Lockdown. National Geographic. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/photography/2020/03/its-eerie-capturing-emptiness-of-paris-city-under-lockdown (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Davis, Mike. 2020a. In the Year of the Plague. Jacobin Magazine. Available online: https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/mike-davis-coronavirus-outbreak-capitalism-left-international-solidarity (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Davis, Mike. 2020b. The Monster Enters. New Left Review 122: 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Mike. 2020c. The Monster Enters: Covid-19, Avian Flu, and the Plagues of Capitalism. New York: OR Books. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Steve. 2009. Commons and Crowds: Figuring Photography from Above and Below. Third Text 23: 447–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Mark. 2012. What is Hauntology? Film Quarterly 66: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, Jordan, and J. Oliver Conroy. 2020. Desolate New York: Eerie Photos of a Ghost Metropolis. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/04/desolate-new-york-eerie-photos-ghost-metropolis-coronavirus (accessed on 26 August 2020).

- Gitlin, Todd. 2003. The Whole World Is Watching: Mass Media in the Making and Unmaking of the New Left. Berkeley: University of California Press. First published in 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhammer, Zach. 2014. The Whole World Is Watching Ferguson. Atlantic. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/08/the-whole-word-is-watching-ferguson/378729/ (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Greenberg, Clement. 1986. Towards a Newer Laocoon. In Clement Greenberg: Collected Essays and Criticism, Perceptions and Judgments, 1939–1944. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, vol. 1, pp. 23–38. First published in 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, Susan. 2017. St. Louis Police Officers Chant ‘Whose Streets, Our Streets’ While Arresting Protestors. Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2017/09/18/st-louis-officers-chant-whose-streets-our-streets-while-arresting-protesters-against-police-killing/ (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Jameson, Fredric. 1991. Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Robin D.G. 2016. Black Study, Black Struggle. Boston Review. Available online: http://bostonreview.net/forum/robin-d-g-kelley-black-study-black-struggle (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Krauss, Rosalind. 1985. Grids. In The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge: The MIT Press. First published in 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Museum of Modern Art. 1965. The Photo Essay. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, (Press Release). [Google Scholar]

- Museum of Modern Art. 1967. New Documents. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, (Press Release). [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, Christopher. 1982. The Judgement Seat of Photography. October 22: 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Clive. 2007. Street Photography: From Atget to Cartier-Bresson. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 1984. Photography Against the Grain: Essays and Photo Works, 1973–1983. Halifax: The Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. First published in 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 2002. Fish Story. Düsseldorf: Richter Verlag. First Published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 1991. Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 2017. Harry Callahan: Gender, Genre, and Street Photography. In Photography After Photography. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stallabrass, Julian. 2002. Paris Pictured. London: Royal Academy of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 1964. André Kertész. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 1966. The Photographer’s Eye. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Szarkowski, John. 1978. Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since the 1960s. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, Alberto. 2016. The World Is Already Without Us. Social Text 34: 109–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Jackie. 2018. Carceral Capitalism. South Pasadena: Semiotext(e). [Google Scholar]

- Westerbeck, Colin, and Joel Meyerowitz. 1994. Bystander: A History of Photography. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Michael. 2020. Coronavirus in N.Y.C. Eerie Streetscapes Are Stripped of Commerce. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/21/nyregion/coronavirus-empty-nyc.html (accessed on 25 March 2020).

| 1 | |

| 2 | On the condition of being haunted by the future, see (Fisher 2012). See as well the short statement penned by the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben (Agamben 2020a). Published in March 2020, in advance of the escalation of the virus in Italy and around the world, the essay encapsulates its argument about the end of public life as follows: “We might say that once terrorism was exhausted as a justification for exceptional measures, the invention of an epidemic offer the ideal pretext for broadening such measures beyond any limitation.” Swift criticism of the philosopher’s statement as well as new evidence that the virus was spreading, prompted a clarification. Agamben did not temper his initial response to calls for a quarantine. The “gravity of the disease” aside, he notes, “fear is a poor advisor” (Agamben 2020b). |

| 3 | There has been extended discussion of the ideological charge of emptiness in recent studies of landscape photography, especially in light of new debates about ecological catastrophes and the periodization of the Anthropocene. For just one essay that attends to the politics of photographic depopulation with regard to the destruction wrought by late capitalism, see (Toscano 2016). |

| 4 | The waves of protests that erupted across cities around the world in response to the murder of George Floyd dominated the news cycle in June and July 2020. However, numerous other protest movements developed or returned to the streets in the wake of national quarantine orders. In April 2020, hunger protests erupted in Lebanon. These preceded the riots that began in August 2020, following the explosion in the port of Beirut that killed close to 200 people, injured more than 7500, and left 300,000 homeless. Anti-extradition protests in Hong Kong, which had begun in June 2019, continued through the spring of 2020. Photographs of these protests returned to the news cycle that May. |

| 5 | In Carceral Capitalism, Jackie Wang describes the streets of Ferguson, Missouri, the site of protests and violent clashes with the police following the murder of Michael Brown in August 2014, as a “carceral space,” noting that due to fine farming and other forms of racist policing, residents are “unable to control how resources are distributed in the city they inhabit—or even to go to work because of outstanding warrants and/or fear that they will be slammed with more tickets and fines.” “When municipalities develop a parasitic relationship to residents,” she continues, “they make it impossible for residents to actually feel at home in the place where they live, walk, work, love, and chill. In this sense, policing is not about crime control or public safety, but about the regulation of people’s lives—their movements and modes of being in the world.” See ((Wang 2018, pp. 189–91); emphasis in the original.) In drawing attention to Wang’s thesis, I am not conflating the Ferguson protests with those that took place in May and June 2020. Rather, I am pointing to the fact that international outcry against police violence and the expansion of an abolition movement under the banner of Black Lives Matters make evident the need to extend the history of carceral capitalism. |

| 6 | To quote Davis: “So Corona walks through the front door as a familiar monster” (Davis 2020b, p. 7). For an extended discussion of the ways in which “the future” was purposely ignored, including efforts to disincentivize for-profit drug companies from producing vaccines and the Trump administration’s decision to defund USAID’s Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT program just three months before the outbreak of the coronavirus in Wuhan, see Davis’ recently revised and updated 2005 study of the Avian flu pandemic (Davis 2020c). |

| 7 | On this protest slogan and coverage of the Democratic National Convention in August 1968, see (Gitlin [1980] 2003). |

| 8 | The slogan was revived at the anti-WTO protests in Seattle, Washington in 1999 and popularized in the 2007 film Battle in Seattle. For an example of its recent reemergence, see (Goldhammer 2014). |

| 9 | Though the protests in response to the murder of George Floyd must be seen in the context of the expansion of the Black Lives Matter movement, their escalation has been linked to the racial disparity in the impact of the coronavirus, with the highest rates of death in racial and ethnic minority groups. |

| 10 | For the postmodern argument, see (Jameson 1991). |

| 11 | Significantly, in Davis’ account, the crisis is not the pandemic. It is the lack of response to the pandemic, which is also, he argues, its cause. The crisis, Davis notes, dates back to Reagan (Davis 2020b, p. 10). Likewise, the monster named in the title of the essay, is not the virus. It is neoliberalism. |

| 12 | See, for example, the two most widely referenced English-language histories of the genre: (Westerbeck and Meyerowitz 1994; Scott 2007). |

| 13 | Julian Stallabrass discusses street photography in these terms, though instead of starting in the 1860s, with the writings of Charles Baudelaire and the movements of the flâneur, he begins in the 1930s, with Benjamin’s historicization of this figure and his forms. In doing so, he subtly dislocates the origin of the genre from the 1850s, locating it in the 1930s; or, to be more exact, as a response to processes of modernization shaping the upheavals of the interwar period, including the rise of the illustrated press. See (Stallabrass 2002). |

| 14 | On the origins of The Decisive Moment and its intended use, see (Chéroux 2014a). |

| 15 | Stallabrass addresses Benjamin’s reading of Baudelaire’s prose in these terms, attending to the way in which the street is also, for the flâneur, at least, an interior. See (Stallabrass 2002, n.p.; Benjamin [1969] 1997, p. 37). |

| 16 | For this story, see, foremost, Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s writing on modernism and its limits in her seminal collection of essays, Photography at the Docks (Solomon-Godeau 1991). See as well her discussion of the invention of street photography in these terms in (Solomon-Godeau 2017). |

| 17 | It is worth noting that this thesis emerged in the mid-1960s and framed Szarkowski’s curatorial work for the next decade. In the catalogue for the 1978 exhibition Mirrors and Windows, quoted above, Szarkowski insists that “the general movement of American photography during the past quarter century has been from public to private concerns.” Significantly, he takes the work of Robert Frank as evidence of this turn inward. See (Szarkowski 1978, p. 11). See as well his framing of the work of André Kertész, a photographer who, like Frank, is now part of the street photography canon (Szarkowski 1964). |

| 18 | Christopher Phillips explores Szarkowski’s debt to Clement Greenberg and American formalism in these terms in his important study of photography’s emergence as an art at the Museum of Modern Art. See (Phillips 1982, pp. 57–61). |

| 19 | The checklist for The Photo Essay lists the names of the photographer and the magazine editor. See “Checklist,” The Photo Essay [MoMA Exh. #760, 16 March to 16 May 1965], Department of Photography Records, Museum of Modern Art, New York. See as well (Bair 2021) on the history of the photo essay and its presentation on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art. |

| 20 | On the work of the violence of the anecdote, see (Sekula [1995] 2002, p. 32). |

| 21 | See, in particular, Sekula’s essay “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation).” Significantly, Sekula does not name Szarkowski in his critique, even though the extended reference to the framing of Arbus as a humanist photographer suggests that he was thinking about the New Documents exhibition and its impact on writing the history of photography and documentary. This refusal to name Szarkowski is key. It reminds us that the “problem” is not Szarkowski—that he is not the “bad guy.” The aligning of photography with subjectivism is, Sekula suggests, symptomatic of the “promotion of introspection” in advanced capitalist societies. See (Sekula [1978] 1984, pp. 58–60). |

| 22 | For a history of street photography that attends to the history of enclosure, see (Edwards 2009). |

| 23 | Though Cartier-Bresson downplayed his political affiliations after the Second World War, he began his career making photographs for Communist Party news outlets Ce Soir and Regard. Likewise, his film work in the 1930s attests to his affiliations with the Popular Front. It could be argued that The Decisive Moment was a means of trying to make a break with this past, in which, almost inevitably, it still lingers. For an account of Cartier-Bresson’s early work as well as the need to self-censor after the war and his time as a prisoner of war, see (Chéroux 2014b, pp. 131–47). Seeking to dislodge the decisive moment as the frame through which Cartier-Bresson’s work is read, Chéroux, significantly, does not downplay or debunk it. He historicizes it by acknowledging its centrality to the development of modernism. |

| 24 | On the role of memory in these terms, see (Kelley 2016). |

| 25 | The need was made explicit in 2017, when police in St. Louis, Missouri chanted the slogan as they arrested men and women protesting the acquittal of Jason Stockley in the fatal shooting of Anthony Lamar Smith. See (Hogan 2017). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schwartz, S. Street Photography Reframed. Arts 2021, 10, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020029

Schwartz S. Street Photography Reframed. Arts. 2021; 10(2):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020029

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchwartz, Stephanie. 2021. "Street Photography Reframed" Arts 10, no. 2: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020029

APA StyleSchwartz, S. (2021). Street Photography Reframed. Arts, 10(2), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020029