Between Yerushalayim DeLita and Jerusalem—The Memorial Inscription from the Bimah of the Great Synagogue of Vilna

Abstract

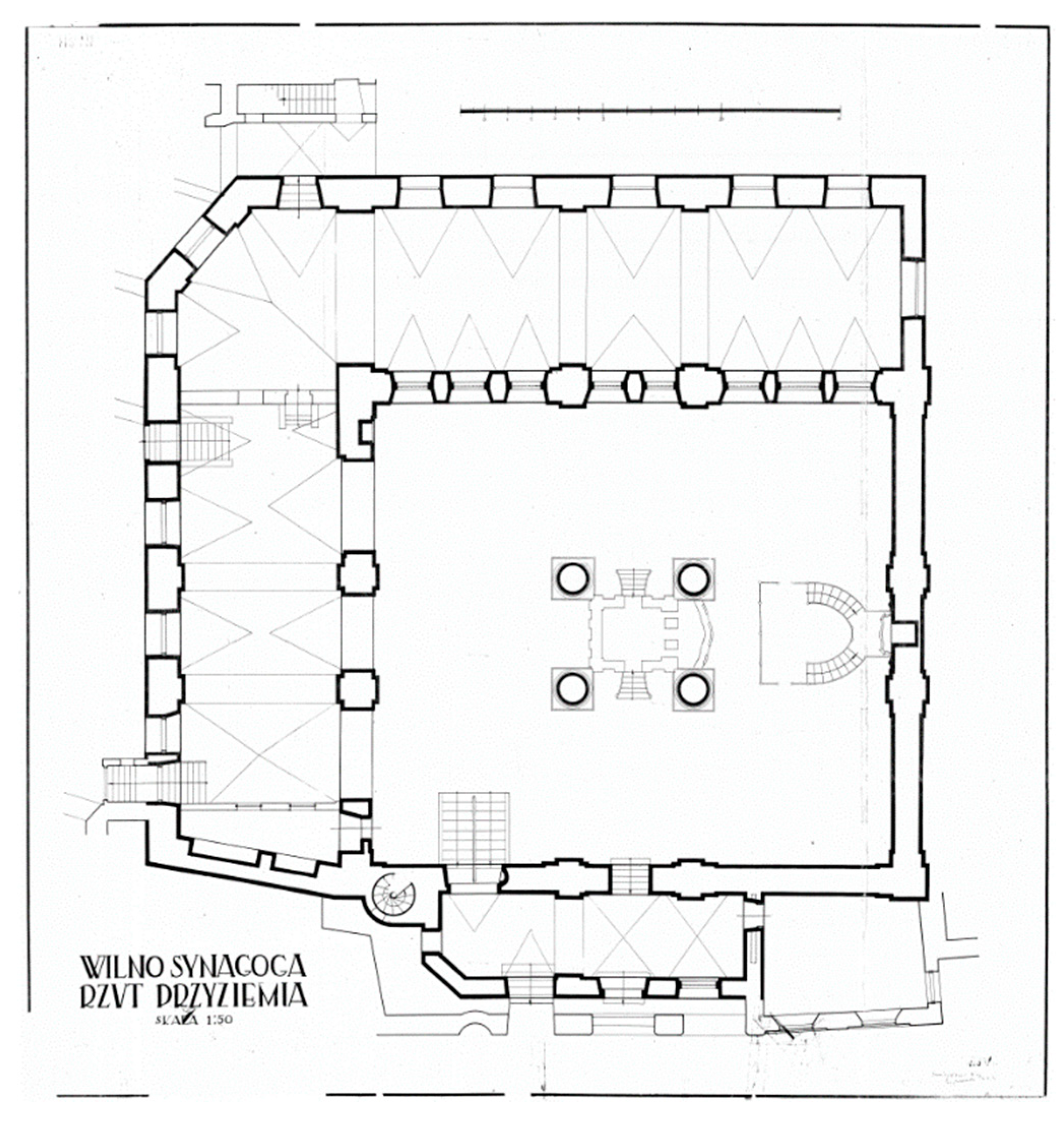

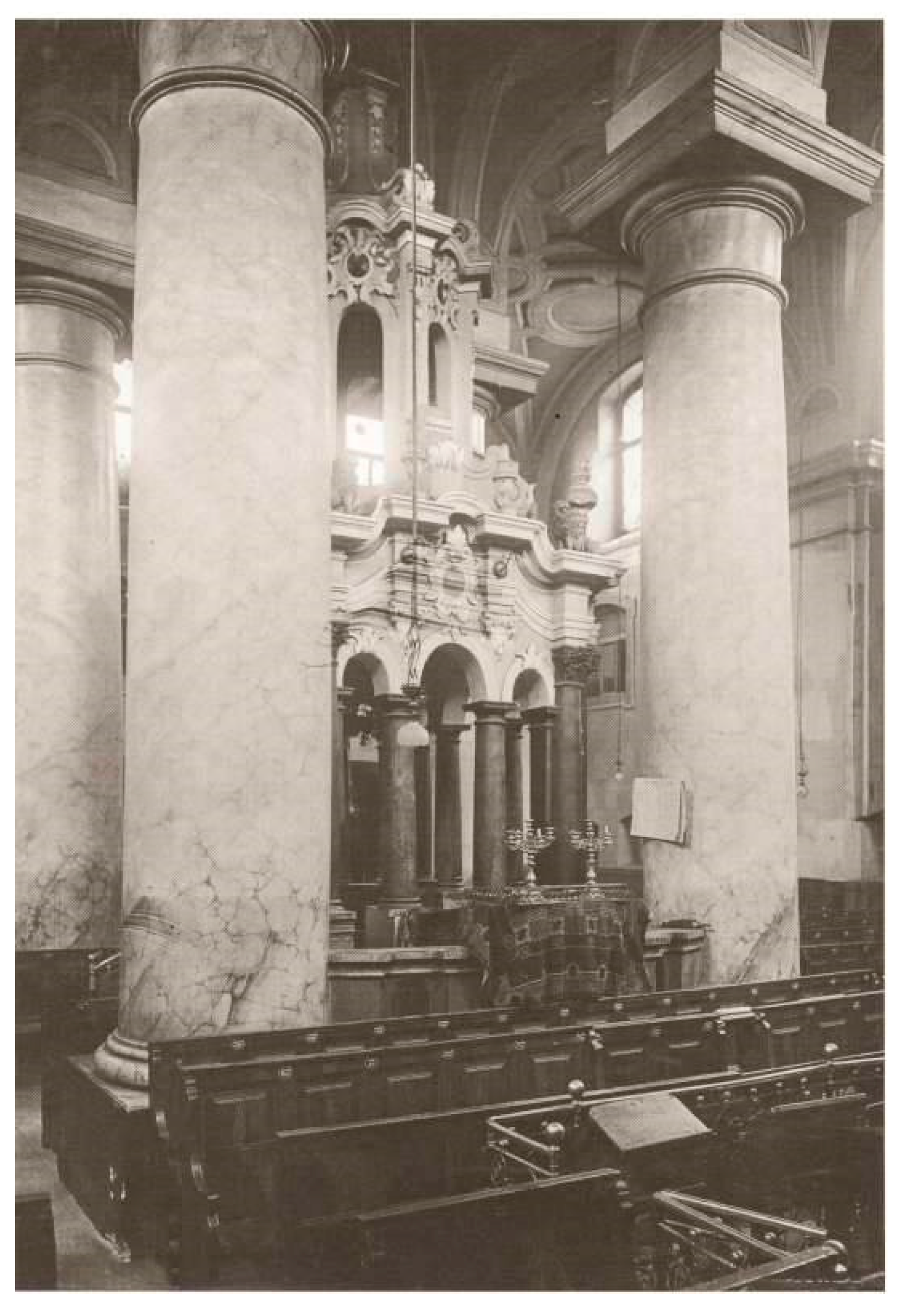

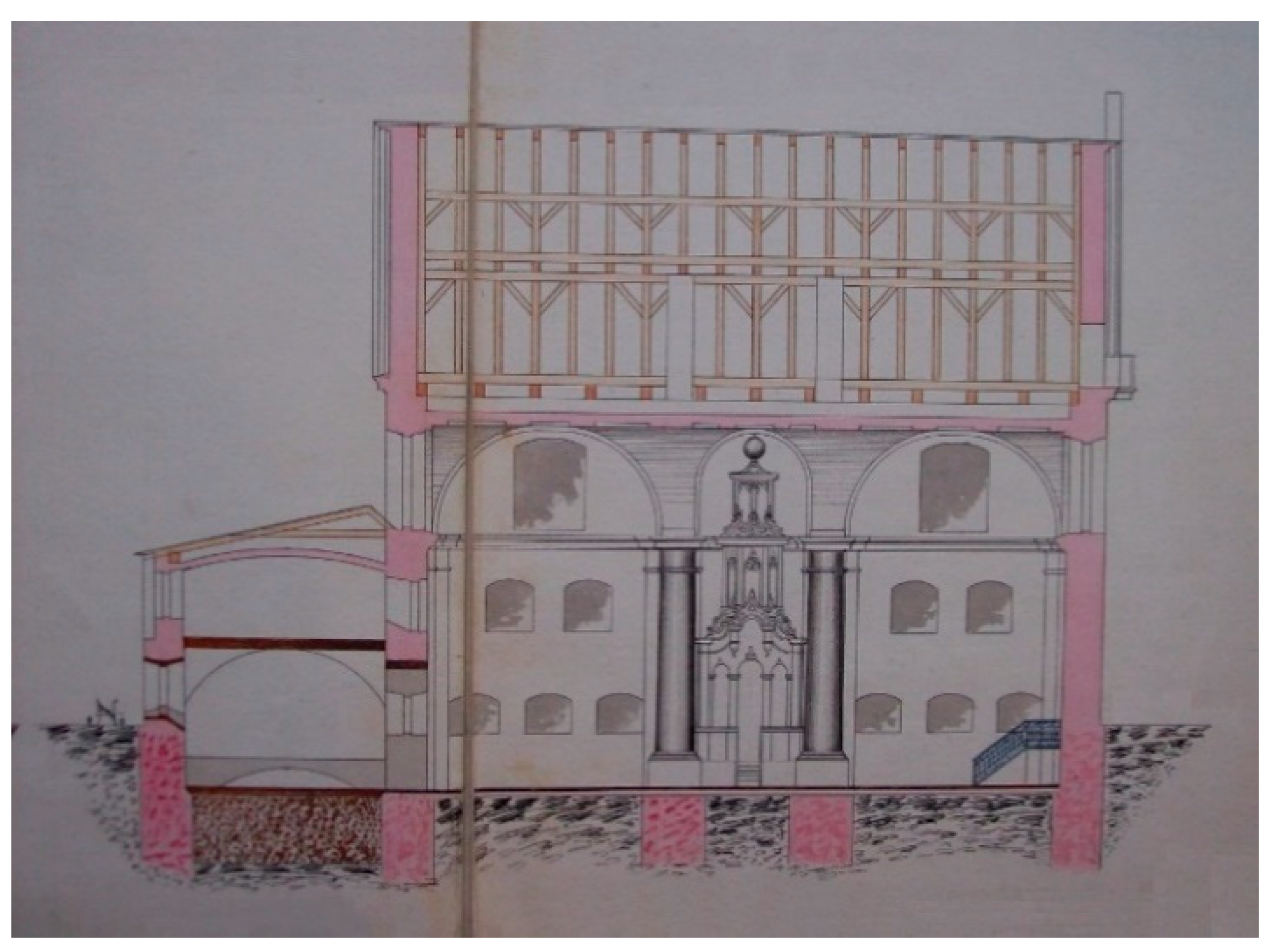

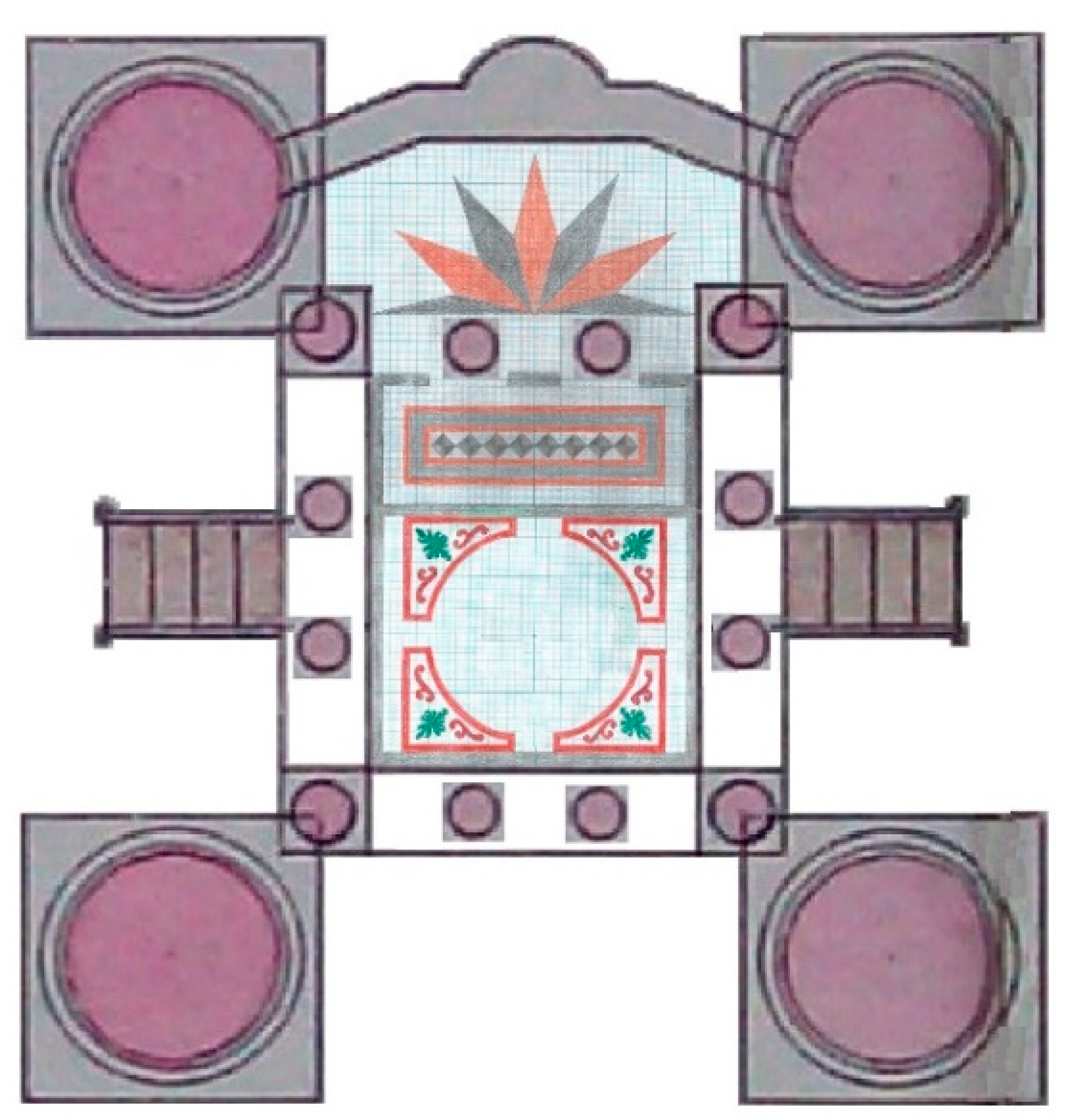

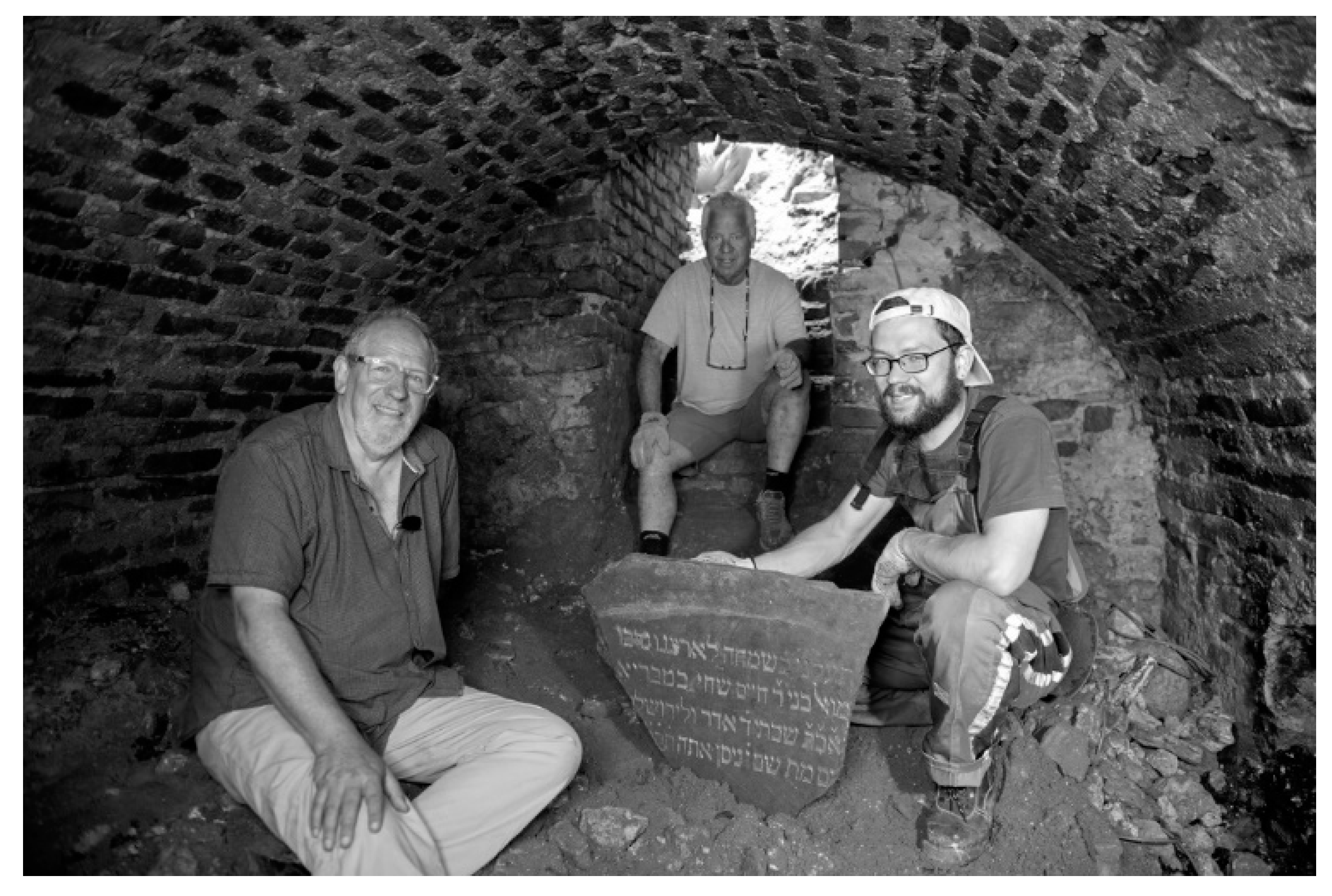

:1. The Bimah—Architectural Description and New Finds

2. The Inscription

| לפרט ת̇ע̇ל̇נ̇ו̇ בשמחה לארצנו נדבו | (1) |

| ר̌ (ר”ת רב) אליעזר ור̌ שמואל בני ר̌ חיים שחי בטבריא ת̌ו̌ב̌ב̌ (ר”ת - תבנה ותכונן במהרה בימינו) | (2) |

| ח̇י̇ש̌ (ר”ת -חיי שרה) ותמת שרה א̌ב̌ר̌ 7 (ר”ת—אמינו בת רב) שבתי ד̇ אדר ולירושלים מ̇ב̇ש̇ר̇ אתן | (3) |

| וא̌ר̌ (ר”ת—ואבינו רב) חיים ב̌ר̌ חיים מת שם ז̇ ניסן אתה ת̇ק̇ו̇ם̇ תרחם ציון | (4) |

- (1)

- Bring us up ([5]556, i.e., 1796/97 CE) with joy to our land. Donated by

- (2)

- R. Eliezer and R. Shmuel, sons of R. Ḥayim who lived in Tiberias may it be rebuilt and re-established in our days

- (3)

- for the life of Sarah (=18 years) and Sarah died, our mother, daughter of R. Shabbtai on the 4th of Adar and I gave to Jerusalem a messenger of good tidings ([5]542, i.e., 18 February 1782)

- (4)

- and our father R. Ḥayim son of R. Ḥayim died there on the 7th of Nissan, arise ([5]546, i.e., 20 March 1787) and have compassion on Zion

3. Synagogue Inscriptions

4. Ḥayim, Sarah, Eliezer, and Shmuel and the Aliyah of Jews from Vilna to the Land of Israel

- from the Mussaf Amidah:יְהִי רָצון מִלְּפָנֶיךָ ה’ אֱלהֵינוּ וֵאלהֵי אֲבותֵינוּ. שֶׁתַּעֲלֵנוּ בְשמְחָה לְאַרְצֵנוּ. וְתִטָּעֵנוּ בִּגְבוּלֵנוּ וְשָׁם נַעֲשה לְפָנֶיךָ אֶת קָרְבְּנות חובותֵינוּ’ (May it be Your will, Lord our God and God of our ancestors, to lead us up in joy to our land and to plant us within our borders. There we will prepare for You our obligatory offerings);

- from Isaiah 41:27:רִאשׁוֹן לְצִיּוֹן, הִנֵּה הִנָּם; וְלִירוּשָׁלִַם, מְבַשֵּׂר אֶתֵּן (A harbinger unto Zion will I give: ‘Behold, behold them’, and to Jerusalem a messenger of good tidings);

- from Psalms 102:14:אַתָּה תָקוּם תְּרַחֵם צִיּוֹן כִּי עֵת לְחֶנְנָהּ כִּי בָא מוֹעֵד (Thou wilt arise, and have compassion upon Zion; for it is time to be gracious unto her, for the appointed time is come).

5. Postscript

| מ”ק (מקום קבורה /מצבת קבורה) |

| הח’ (החכם) המעולה כה’ר (כבוד הרב) חיים |

| אשכנזי |

| The place of burial |

| The sage, the honourable Rabbi Ḥayim |

| Ashkenazi |

| מ”ק (מקום קבורה / מצבת קבורה) |

| האשה הכבודה מרת |

| שרה נ’ב (נוות ביתו) כהר (כבוד הרב) חיי |

| אשכנזי |

| The place of burial |

| The honourable wife, Mrs. |

| Sarah, the household oasis for the honourable Rabbi Ḥayim |

| Ashkenazi |

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barnai, Ya’acov. 1980. Hasidic Letters from the Land of -Israel: From the Second Part of the Eighteenth Century and the First Part of the Nineteenth Century. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben Zvi. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Barnai, Ya’akov. 1995. Historiography and Nationalism: Trends in the Research of Palestine and its Jewish Yishuv (634-1881). Jerusalem: Magnes Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bartal, Israel. 1994. Exile in the Homeland. Jerusalem: Hassifria Haẓiyonit. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bartal, Israel. 2011. ‘Torah as their Craft’ or ‘Zionist Pioneers’: Two Schools of Thought in the Research on the Immigration of the Vilna Gaon’s Disciples to The Land of -Israel. In The Vilna Gaon’s Disciples in The Land of -Israel: History, Thought, Reality. Edited by Israel Rozenson and Yosek Rivlin. Jerusalem: Efrata College, pp. 7–22. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, Eleonora. 1997. Motifs Pertaining to Jerusalem in the Building and Decorating of 19th and Early 20th Century Synagogues in the Polish Lands. In Jerozolima w kulturze Europejskiej. Edited by Piotr Paszkewicz and Tadeusz Zadrożny. Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, pp. 449–57. [Google Scholar]

- Böcher, Otto. 1961. Die Alte Synagoge zu Worms. In Die Alte Synagogue zu Worms. Edited by Ernst Róth. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag, pp. 11–154. [Google Scholar]

- Broydes, Yitsḥak. 1947. Legends of Jerusalem of Lithuania. Tel Aviv: N. Taverski. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Crovato, Antonio. 2002. I pavimenti alla veneziana. Treviso: Edizioni Grafi, Resana. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, Zussia. 1997. Motifs of Jerusalem in the Mural Painting of Eastern European Synagogues: The Researcher’s Impression. In Jerozolima w kulturze Europejskiej. Edited by Piotr Paszkewicz and Tadeusz Zadrożny. Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, pp. 459–65. [Google Scholar]

- Eliav, Mordechai. 1978. The Land of Israel and its Jewish Community in the Nineteenth Century, 1777–1917. Jerusalem: Keter. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Eliav, Mordechai. 1982. Relations between Ashkenazim and Sephardim in the Land of -Israel in the 19th Century. Pe’amim: Studies in Oriental Jewry 11: 118–34. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Eliach, Eli. 2019. Midrash Perushim—The Kloyz of the Gaon of Vilna, Safed. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39693028/%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%A9_%D7%A4%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%A9%D7%99%D7%9D_-_%D7%A7%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%99%D7%96_%D7%94%D7%92%D7%A8%D7%90_%D7%91%D7%A6%D7%A4%D7%AA (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Epstein, Abraham. 1896. Jüdische Alterthümer in Worms und Speier. Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums 11: 509–15. [Google Scholar]

- Etkes, Immanuel. 2015. The Vilna Gaon and His Disciples as Precursors of Zionism: The Vicissitudes of a Myth. In The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz. Edited by ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Sylvia Fuks Fried and Eugene R. Sheppard. Waltham: Brandeis University Press, pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Etkes, Immanuel. 2019. The Messianic Zionism of the Vilna Gaon: The Invention of a Tradition. Jerusalem: Carmel. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Finn, Shmuel Yosef. 1860. Kiriya Ne’emana: History of the Jewish Community in Vilna and Markers for the Souls of its Scholars, Gaonim, Writers and Benefactors. Vilna: Romm Publishers. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Foerster, Gideon. 1981. Synagogue Inscriptions and their Relation to Liturgical Versions. Cathedra 19: 11–46. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Jean-Baptiste. 1936. Corpus inscriptionum Iudaicarum: recueil des inscriptions juives qui vont du IIIe siecle avant Jésus-Christ au VIIe siecle de notre ére. Rome: Europe Pontificio Instituto di Archeologia Cristiana, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, Arie Leib. 1929. History of the Sages of Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Solomon Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg-Mulkiewicz, Olga. 1997. The Image of Jerusalem in the Jewish Diaspora of the 19th and 20th Centuries. In Jerozolima w kulturze Europejskiej. Edited by Piotr Paszkewicz and Tadeusz Zadrożny. Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, pp. 467–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hachlili, Rachel. 1998. Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Diaspora. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Klausner, Israel. 1935. The History of the Old Cemetery in Vilna. Vilna: Vilna Jewish Community. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Klausner, Israel. 1941. Vilna in the Time of the Gaon: Spiritual and Social Conflict in the Vilna Community in the Period of the Gra. Jerusalem: Reuven Mass. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Samuel. 1920. Jüdisch-palästinisches Corpus Inscriptionum (Ossuar-, Grab- und Synagogeninschriften). Vienna: R. Loewit. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Vladimir. 2012. Appendix: Synagogues, Batei Midrash and Kloyzn in Vilnius. In Synagogues in Lithuania II. Edited by Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Sergey Kravtsov, Vladimir Levin, Giedrė Mickūnaitė and Jurgita Šiaučiūnaitė-Verbickienė. Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, pp. 281–340. [Google Scholar]

- Lipshitz, Baruch. 1967. Donateurs et fondateurs dans les synagogues juives. Paris: Cahiers de la Revue Biblique 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lunsky, Chaykel. 1921. From the Vilner Ghetto: Types and Shadows. Vilna: The Association of Hebrew Writers and Journalists in Vilna. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 1993. From Brody to The Land of Israel and Back (The Tombstone of Malka bat Yitzhak Babad). Zion 58: 107–13. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 1998. Mysticism and Messianism: From Luzzatto to the Vilna Gaon. Jerusalem: Maor Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 2006. Hastening Redemption: Messianism and the Resettlement of the Land of Israel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 2007. The Return to Jerusalem: The Jewish Resettlement of Israel, 1800–1860. Jerusalem: Shalem Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, Arie. 2012. The Gaon of Vilna and his Messianic Vision. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Naveh, Joseph. 1978. On Stone and Mosaic: The Aramaic and Hebrew Inscriptions from Ancient Synagogues. Tel Aviv: Israel Exploration Society. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin, Yosef Yoel. 1959. The Link of the Jews of Lithuania to the Land of -Israel. In The Jews of Lithuania. Edited by Avraham Ya’ari. Tel Aviv: I. Am HaSefer, pp. 457–63. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Rodov, Ilia. 2003. The Development of Medieval and Renaissance Sculptural Decoration in Ashkenazi Synagogues from Worms to the Cracow Area. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Rodov, Ilia. 2013. “With Eyes toward Zion:” Visions of the Holy Land in Romanian Synagogues. QUEST. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History 6: 138–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rupeikienė, Marija. 2008. A Disappearing Heritage: The Synagogue Architecture of Lithuania. Vilnius: E. Karpavičius Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, Moïse. 1907. Rapport sur les inscriptions hébraïques de l’Espagne. Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques et littéraires 14. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. [Google Scholar]

- Steinschneider, Hillel Noah Maggid. 1900. Book of the City of Vilna (Sefer Ir Vilna). Vilna: Romm. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik, Eleazar Lipa. 1934. Ancient Synagogues in Palestine and Greece. London: British Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Yahalom, Joseph. 1981. Piyyut as Poetry. In The Synagogue in Late Antiquity. Edited by Lee. I. Levine. Pennsylvania: American Schools of Oriental Research, pp. 111–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yardeni, Ada. 2002. The Book of Hebrew Script History, Palaeography, Script Styles, Calligraphy and Design. London: The British Library and Oak Knoll Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The researchers involved in the Vilna Synagogue and Shulhoyf Research Project are Dr. Jon Seligman—Israel Antiquities Authority; Zenonas Baubonis & Justinas Račas—Kultūros paveldo išsaugojimo pajėgos; Prof. Richard Freund—University of Hartford; Prof. Harry Jol—University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire; Prof. Phillip Reeder—Duquesne University. See: www.seligman.org.il/vilna_synagogue_home.html. |

| 2 | LVIA—Lithuanian State Historical Archives (Lietuvos Valstybes Istorijos Archyvas). |

| 3 | According to Levin (2012, p. 289, n. 54), these drawn by Roman Sigalin and Jerzy Berliner of the Institute of Polish Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology (Zakład Architektury Polskiej Politechniki Warszawskiej) and their copies redrawn by Arkadii Konduralov (1883–1971) in 1949 are kept in Archives of the Cultural Heritage Centre, Vilnius, Nos. 418–21. |

| 4 | With no colour photographs or verbal descriptions detailing the colouring of the interior of the Great Synagogue, we rely on the surprisingly documentary painting of the interior of the edifice produced by Mark Chagall during his visit to Vilna in 1935 (Levin 2012, p. 288, fig. 18). The colouring of this painting we know to be accurate as it matches the surviving blue and red shield, now displayed in the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum, once set above the doors of the Torah ark and now confirmed from coloured pieces of plaster from the bimah discovered during the excavation itself that also match Chagall’s painting. |

| 5 | Steinschneider (1900, p. 92, n. 1) describes the stone as being of red marble, which it clearly is not. Lunsky (1921, p. 56) goes on to claim that the stone originates in Tiberias, also an impossibility as Tiberias-sourced stone is either black basalt or white limestone. The stone used for the inscription is probably a regionally sourced red sandstone on unknown origin. |

| 6 | The inscription is not visible in any of the photographs known to this author. It was probably covered by a cloth draped over the Torah reading table that can be seen in numerous images. |

| 7 | The letter “ר” had originally been inscribed with the letter “ת” but had been corrected by filling in the bottom stroke of the letter. The abbreviation אב”ר is unusual and is explained by Steinschneider (1900, p. 92, n. 1) as “אמנו בת רב” (our mother, daughter of Reb or Rabbi). |

| 8 | The Hebrew word עליה (aliyah), literately “ascent”, relates to emigration to the Land of Israel specifically. Aliyah, in its pre-Zionist religious context, was identified as a commandment by rabbinic scholars, including the Rambam and the Gaon of Vilna (see note 18). |

| 9 | Given that in Ashkenazi tradition, a child is named only after a deceased relative, the name “Ḥayim, the son of Ḥayim” is unusual and may indicate that Ḥayim’s father passed away before his birth. |

| 10 | On the historiographic debate concerning the motivation of the aliyah of the students of the Gaon of Vilna to Eretz Israel at the turn of the 19th century, see below as well as note 18. |

| 11 | The first Jewish cemetery in Vilna, known as the Piramont or Šnipiškės cemetery, set across the Neris River from the Gediminas Tower, was founded in the 15th cemetery and remained in use until its closure by the Tsarist authorities in 1831. Fortunately, this cemetery, which was the resting place of the Gaon of Vilna and all the historic leading community figures, was documented by Steinschneider (1900) and Klausner (1935), before being razed by the Soviet authorities in 1949–50 for the construction of a sports hall. |

| 12 | See comment no. 4. |

| 13 | The graffities (Figure 13) carved into the face of the inscription slab included the the following initials: (1) “ICP, (?)32”; (2) “RPM” set within a scratched form of a house or church; (3) “SEM” inside the scratched form of a heart; and (4) “IHIL”. |

| 14 | The discussion of dedicatory inscriptions during the Second Temple period through late Antiquity in the Land of Israel and the Diaspora has received wide ranging attention—see: (Klein 1920; Frey 1936; Sukenik 1934, pp. 69–78; Foerster 1981: Hachlili 1998, pp. 401–13; Naveh 1978, pp. 4–16; Lipshitz 1967). |

| 15 | Piyyut: Jewish liturgical poems that developed in Spain and the Rhineland in the 10–11th centuries. Note the similar use of Biblical quotations and paraphrases. See: (Yahalom 1981; Foerster 1981, pp. 11–40). |

| 16 | Coincidentally, this inscription is cut, similar to that in Vilna, from red sandstone. The full text is as follows: הא]בן הזא[ת שבצד הארון] \ [עד]ה למר יע[קב איש כשרון] \ בכל שבת [ושבת בזכרון] \ להזכיר[ו עם ישיני חברון] (This stone at the side of the Ark / [is] a witness for Jacob, a man of talent / every Sabbath in memory / to remember him [saying his name] along with the sleeping men of Hebron” (Epstein 1896, p. 513; Böcher 1961, p. 99; Rodov 2003, p. 26, n. 30). |

| 17 | Significant inscriptions with direct and often messianic reference to Jerusalem and other places in Eretz Israel have also been found also in Spain on Jewish tombstones and dedicatory inscriptions of the 12th to 14th century in Leon, Toledo, Cordoba (Schwab 1907, pp. 261, 288–89, 367). |

| 18 | For studies on the visual portrayal of Jerusalem and other holy places in the Land of Israel in the synagogues of Europe, see: (Bergman 1997; Efron 1997; Goldberg-Mulkiewicz 1997; Rodov 2013). |

| 19 | The often-vitriolic debate over the past four decades concerning the motivation of the aliyah of the students of the Gaon of Vilna to Eretz Israel at the turn of the 19th century has developed into the establishment of two opposing schools of thought. Some, especially those who have personal connections to the Perushim or with backgrounds in religious Zionism, have proposed that a messianic ideal, spear-headed by the Gaon himself, was the motivation for this aliyah, as a precursor to modern Zionism (Rivlin 1959; Eliav 1978; Morgenstern 1998, pp. 144–79; Morgenstern 2006, 2007, 2012, pp. 271–288 etc.). Other researchers, especially those of secular scholarship, have rejected these proposals, seeing the Perushim and their aliyah as no more than the continuation of traditional religious migrations of Jews to Eretz-Israel, aimed at creating a scholarly Torah community in the Holy Land, with no connection to the development of modern political Zionism in the second half of the 19th century (Bartal 1994, pp. 41–48, 52, 236–264; Bartal 2011; Barnai 1995; Etkes 2015, 2019). |

| 20 | The name family name Shebtels (שבתל’ס ,שבתלס) appears in the references in a number of different phonetically spelled alternatives—Shepshils (שפשילס), Shepshilas (שעפשילס), and Shepshiller (שעפשילר), all derived from the name of Ḥayim’s father-in-law, Shabtai (ben Elḥanan Ḥefez) (Steinschneider 1900, p. 92, n. 1; Morgenstern 2012, p. 278, n. 109). |

| 21 | The date of the aliyah of R. Ḥayim is estimated on the basis of the inscription, which states that Ḥayim resided in Tiberias for 18 years prior to his death in 1787. |

| 22 | Steinschneider also provides multiple references to Shmuel’s son, Rabbi Yizhak Eliyahu Landau (Steinschneider 1900, pp. 92–98 and others), who was a noted Torah scholar in Vilna, and to other descendants of this important Rabbinical family. |

| 23 | Thanks are due to Yehuda Mizrachi-Zoref, Tzameret-Rivka Avivi, Rabbi Mordechai Motola, and Micha Carmon for pointing this out. |

| 24 | The addition of the community affiliation “Ashkenazi” to a grave marker in the Sephardi cemetery on the Mount of Olives was prevalent until the establishment of a separate Ashkenazi cemetery in 1855 (Eliav 1982, p. 129, n. 26). Multiple tombstones with the addition of the designation “Ashkenazi” can be located in the vicinity of the markers of Ḥayim and Sarah, some clearly associated with the followers of the Gaon of Vilna, such as Mordachai Petaḥya Ashkenazi (–1758) (Frumkin 1929, III, p.71); Shmuel Zanvill Ashkenazi (–1767); Sa’adya Ashkenazi (–1813) (Frumkin 1929, III, p. 164); Menaḥem Mendel from Shklov (–1827) (Frumkin 1929, III, p. 163); etc. |

| 25 | See: mountofolives.co.il/he/deceased_card/חיים-אשכנזי-haim-ashkenazi-2/#gsc.tab=0. |

| 26 | Ibid. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seligman, J. Between Yerushalayim DeLita and Jerusalem—The Memorial Inscription from the Bimah of the Great Synagogue of Vilna. Arts 2020, 9, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020046

Seligman J. Between Yerushalayim DeLita and Jerusalem—The Memorial Inscription from the Bimah of the Great Synagogue of Vilna. Arts. 2020; 9(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeligman, Jon. 2020. "Between Yerushalayim DeLita and Jerusalem—The Memorial Inscription from the Bimah of the Great Synagogue of Vilna" Arts 9, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020046

APA StyleSeligman, J. (2020). Between Yerushalayim DeLita and Jerusalem—The Memorial Inscription from the Bimah of the Great Synagogue of Vilna. Arts, 9(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020046